All the Arguments You Need: To Prove It’s Fair for Trans, Intersex Athletes to Compete in Consistence With Their Gender Identity

Bodies and gender identities aren’t binary, so why are sporting competitions?

Nowhere is the struggle between maintaining the traditional status quo of the gender binary, and moving forward toward greater inclusivity, more pronounced than in competitive sports, due to the differences in male and female physiology. But, there is enough science and data out there to suggest these differences aren’t nearly as stark as we’ve been led to believe — which means any argument against allowing trans and intersex people and people with differences in sex development (DSD) to compete against ciswomen is queerphobic at best. Here are all the arguments you need to fight for greater gender inclusivity in sport.

“Biological males have physical advantages over women such as more stamina, larger bones, and more muscle, so it’s unfair for trans women to compete with ciswomen.”

The science on what women’s bodies can do is flimsy at best. But consider what the female body can do better than a male body: “Women’s bodies have a lower center of gravity and therefore better balance; they tend to be more flexible, and their bodies more efficiently convert calories into energy giving them greater endurance,” Liesl Goeker writes for The Swaddle , while arguing for equal pay in sports. This gives women the upper hand in ultra-endurance running and gymnastics — just as male bodies have the upper hand when it comes to sports such as the shotput and 100m sprint that require speed and brute strength. But zero trans women who are gymnasts are complaining about the advantage cis women have, or saying they want to compete in the men’s category for endurance running or gymnastics — because they just want to participate in the sports category congruent with their gender identity.

Besides, sports isn’t ‘fair.’ It never was. Genetics isn’t either. Many elite athletes are genetically blessed in a way the average person isn’t. Basketball players have the advantage of height, and Michel Phelps’s very peculiar anatomy gives him the upper handin swimming. Privilege isn’t fair either — athletes of color are at a disadvantage when it comes to exposure, opportunities, and resources to even begin pursuing sports competitively, compared to Caucasian athletes. So, what is this “level playing field” argument but a myth spun by those allowed to play and win in the field, to maintain the status quo?

Related on The Swaddle:

New Report Outlines Scale of Homophobia, Transphobia in Sport

“Biological males have the advantage of testosterone that enhances performance so it’s unfair for trans women to compete with ciswomen.”

The science on physiological advantages male athletes have over female athletes is in a nascent stage. It’s important to preface this argument by pointing out that very little research and conversation is around, say, the advantages of estrogen (the hormone responsible for many physical characteristics of a typical female) or prolactin (the breastfeeding hormone) on athletic ability. The obsession is entirely with testosterone (T) — the hormone responsible for many glorified physical characteristics of a typical male — and the absurd question of at what level of testosterone does a female athlete become too good to be a woman.

For every credible study and statement out there that proves greater testosterone is linked to greater athletic ability in men and women, there are equally credible studies that prove testosterone is just one of the many factors that affect sporting ability — sometimes even negatively. Take the International Association for Athletics Federation’s data on elite women athletes. Its initial analysis of two world championships showed that women with higher T levels performed better in only five out of 21 events.

After an independent group of researchers took an issue with the research methodology to reach even this finding, the sports body was forced to issue a correction. In the corrected results, in three of 11 running events, the group with the lowest levels of T did better. Across all events, the association between T and performance was the strongest (and the most surprising) in the 100m sprint: athletes with lower T ran 5.4% faster than those with the highest levels of T. The independent group of researchers who objected to the results earlier concluded it’s “impossible” to discern the real relationship, if any, between T and performance. Clearly, though, neither this study nor the broader sports science literature supports the IAAF’s claim that targeted trans, intersex athletes “have the same advantages over [other] women as men do over women.”

Then there’s the stuff outside of the binary that science is nowhere close to explaining clearly, like Chand’s and Semenya’s hyperandrogenism (a medical condition where a typical female body produces higher testosterone than usual). Or, as Faryal Mirza, a clinical endocrinologist at the University of Connecticut Medical Center, tells Scientific American , sometimes high T simply means that a person isn’t very efficient at using T: the body is producing more precisely to arrive at “typical” function of someone producing T in the “typical range.”

IAAF’s Caster Semenya Decision Arbitrarily Dictates What Is Female

A review of 31 national and international transgender sporting policies, including those of the International Olympic Committee, the Football Association, Rugby Football Union and the Lawn Tennis Association by researchers at the Scool of Sports Exercise and Health Sciences, Loughborough University concluded : “After considering the very limited and indirect physiological research that has explored athletic advantage in transgender people, we concluded that the majority of these policies were unfairly discriminating against transgender people, especially transgender females” by overinterpreting the “unsubstantiated belief” that testosterone improves athletic performance.

Thousands of trans athletes have been competing at national and international competitions who you just don’t hear about simply because they don’t all win or qualify for the Olympics even with all their apparent unfair advantages. This also proves the non-cisgender athletes who do go ahead and win medals owe their success more to their training, skill, perseverance, resilience, and a host of other reasons apart from their gender or sex, and especially from the myth of testosterone.

“Letting trans and intersex women compete in women’s sports will lead to many male athletes pretending to be women just so they can easily win.”

Yikes. Are we really suggesting there are numerous male athletes who will declare they identify as women, go through exhausting transition processes such as hormone replacement, gather the required medical and psychological proof of their fake gender dysmorphia (prolonged distress caused a mismatch between their biological sex and gender identity), go through their entire lives living under the pretense of being female, all while facing prejudice that trans people face on a daily basis — only for a few gold medals and some cash? Notwithstanding the paranoia (looking at you Martina Navratilova ), this argument is the literal definition of transphobia . This idea — that we should ban all innocent and real trans and intersex women based solely on the fantastic hypothetical of the fraudulent cis man — has roots in an irrational fear of the other (in this case, non-cisgender people) based on prejudice or ignorance.

Laws and rules can always be misused, irrespective of gender. But, we can’t deny people’s rights simply because a few could, in theory, game the system. Look at it this way: are some people falsely framed for murder? Yes. Does that mean we don’t have any rules to punish the crime? Of course not.

This debate doesn’t even have to be esoteric; there is actual data to prove male athletes aren’t queuing up to declare a new gender identity. In 2003, the International Olympic Committee adopted the Stockholm Consensus (SC) allowing the inclusion of trans athletes who had undergone sex reassignment, making it possible for trans athletes to compete in the Olympics from 2004. The IOC modified these guidelines in 2015 to put a cap on testosterone levels for trans womenathletes. And yet, despite the fact that more than 50,000 athletes have participated in the Olympics since 2004, no trans athlete has ever been a part of the Olympics until now, real or fake. So, clearly including trans athletes in sports won’t make the sky fall.

Explaining the Vocabulary of the Gender Spectrum

“If not men’s and women’s sports categories, then how do we organize sports fairly?”

Creating a third, mixed category for trans, non-binary, cis men and women to compete against each other can be an earnest, motivating place to start making sports more inclusive. Mixed-gender sports teams are a widely debated topic and have been for many years, just not in relation to opportunities for transgender people. But, introducing more mixed-gender sports teams would also facilitate accessibility for transgender people. The IOC did well, when in June 2017, it added mixed-sex events in athletics, swimming, table tennis, and triathlon to the upcoming Summer Olympics schedule in Tokyo 2020 , in addition to the traditional categories. This not only allows trans and intersex athletes to compete in the sports category congruent with their gender identity based on their athletic ability alone, Tokyo 2020’s milestone mixed-sex events are a concrete step towards ungendering sports. (It is important here to note this will all be moot unless the IOC allows trans and intersex athletes to compete — in these mixed events at least — without having to meet any criteria other than being a human adult who’s good enough to qualify.)

Another way to organize sports, as suggested by Alison Heather, a physiologist at the University of Otago in New Zealand, and her colleagues in an essay published in the Journal of Medical Ethics , would be to create a system that uses an algorithm to account for physiological factors such as testosterone, height, and endurance, and social factors like gender identity and socioeconomic status. Sure it’s a Herculean task, but international sports bodies have enough money to at least begin research into the idea if it means a more inclusive world.

Apart from this, sports can also be organized on the basis of other factors such as weight class, professional/amateur status, and size. The idea is that through a mixture of formats, we redesign sports to make them more inclusive.

It’s going to take fresh thinking and self-awareness that what we believe to be facts about sex and gender are not unquestionable. But every individual must have the possibility of practicing sport, without discrimination of any kind, and in the spirit which requires mutual understanding, with a spirit of friendship, solidarity and fair play. Those are not my words, that’s the Olympic charter.

Pallavi Prasad is The Swaddle's Features Editor. When she isn't fighting for gender justice and being righteous, you can find her dabbling in street and sports photography, reading philosophy, drowning in green tea, and procrastinating on doing the dishes.

Why Indian Women Protesters Sang a Chilean Anti‑Rape Anthem

Little Big Things: A 25‑Year‑Old’s Shift From Being Apolitical to Protesting NRC‑CAA

Rapists Increasingly Killed Their Victims in 2018: NCRB

Striking a balance between fairness in competition and the rights of transgender athletes

Professor of Ethics, Strategy, and Public Policy, University of New Orleans

Disclosure statement

Chris W. Surprenant does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

In a majority of U.S. states , bills aiming to restrict who can compete in women’s sports at public institutions have either been signed into law or are working their way through state legislatures.

Caught up in this political point-scoring are real people – both trans athletes who want to participate in competitive sports and those competing against them.

As a professor of ethics and public policy , I spend much of my time thinking about the role of the law in protecting the rights of individuals, especially when the rights of some people appear to conflict with the rights of others.

How to accommodate transgender athletes in competitive sports – or whether they should be accommodated at all – has become one of these conflicts.

On one side are transgender athletes who want to compete in the gender division with which they identify. On the other are political activists and athletes – especially biologically female athletes – who believe that allowing trans athletes to compete in women’s divisions is inherently unfair .

So why is this issue so fraught? What’s so special about women’s sports? Why do women’s divisions even exist? And is it possible to protect women’s sports while still finding a way to allow transgender athletes to compete in a meaningful way?

Winners elicit outcry

Let’s be clear: Few Americans would care about how to best accommodate transgender athletes if they were not winning events.

But that’s exactly what has happened. In 2017 and 2018, Terry Miller, a trans woman, won the Connecticut women’s high school track championships in the 55-meter, 100-meter, 200-meter and 300-meter events. Her closest and only real competitor those two years was Andraya Yearwood , who is also a trans woman.

In 2017 and 2018, Mack Beggs, a trans man, dominated the Texas 6A 110-pound girls wrestling division, capturing two state championships while compiling a record of 89 wins and 0 losses. Unlike in Connecticut, where athletes may compete as they identify , athletes in Texas must compete in the gender listed on their birth certificate .

While Miller, Yearwood, Beggs and others have triumphed in their respective sports, the number of transgender high school athletes is very low . Nor is there any evidence that athletes have transitioned for the purpose of gaining a competitive advantage.

Yet some legislators have latched onto these examples, using them as a basis for bills that ban all transgender teens from participating in gendered divisions that differ from their birth sex. But these bills don’t solve the competitive imbalances that can occur with athletes like Beggs. Worse, they might prevent transgender teens from competing altogether.

Sports matter – with meaningful participation

Since studies have shown that kids who participate meaningfully in athletics have better mental and physical health than their peers who don’t – and teens who identify as transgender are at a significantly greater mental health risk than their peers – it’s a worthy goal to try to accommodate their desire to compete.

The phrase “participate meaningfully” is important. Someone who, for example, is nominally on a team but does not take the sport seriously does not participate meaningfully in competitive sports. Similarly, someone who takes a sport seriously but easily dominates all competition also does not participate meaningfully in competition.

Youth sports organizations exist because we don’t believe kids should compete against adults, and kids are further separated by age because age, for children, is a reasonably good proxy for skill and ability. Organizations like the Special Olympics and Paralympics exist to provide opportunities for people with physical and mental disabilities to participate meaningfully and compete against people with similar skill sets.

Male and female athletes are separated for the same reason.

[ The Conversation’s science, health and technology editors pick their favorite stories. Weekly on Wednesdays .]

The rise of women’s sports

In 1972, the U.S. Congress extended Title IX of the Educational Amendments to the 1964 Civil Rights Act to prohibit discrimination in all federally funded education programs, including their associated athletics programs .

Title IX’s impact on athletics for women and girls – and, as a result, U.S. culture – has been nothing short of dramatic . In 1970, fewer than 5% of U.S. girls participated in high school sports. Now 43% of high school girls participate in competitive sports.

Separating athletes by biological sex is necessary because the gap between the best male and female athletes – at all levels – is dramatic.

Serena Williams is not only one of the best female tennis players in history, she’s one of the best female athletes in history. In 1998, both Serena and her sister Venus famously claimed that no male ranked outside of the ATP Top 200 could beat them. Karsten Braasch, the 203rd-ranked player ATP player at the time, challenged each to a set. Braasch beat Serena 6-1 and Venus 6-2.

“I didn’t know it would be that difficult,” Serena said after the match . “I played shots that would have been winners on the women’s circuit, and he got to them very easily.”

At the 2019 New Balance Nationals Outdoor, the national track championship for U.S. high school students, Joseph Fahnbulleh of Minnesota won the men’s 100-meter with a time of 10.35 seconds . That same year, Olympic Gold Medal winner Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce ran the fastest 100-meter time of any female in the world – 10.71 seconds . Her time would have tied for 19th at that U.S. boys high school event.

One more example that’s a bit different: In 2012, Keeling Pilaro , a 4-foot-8, 80-pound seventh grade boy, petitioned the New York State Public High School Athletic Association to play field hockey on his school’s all-female team. It approved his petition.

As a seventh grader, Pilaro made the school’s JV team. As an eighth grader, he made the varsity team. But players and coaches from other schools argued he had a significant advantage because he was a boy. During the summer before his ninth grade year, the league agreed. It ruled Pilaro could no longer participate because his “advanced field hockey skills” had “adversely affected the opportunities of females.”

I point to these examples because, put together, they show that no fitness regimen, no amount of practice, and no reallocation of financial resources could allow the best female athletes at any level to compete against the best male athletes at that same level.

This advantage isn’t simply a difference in degree – it’s not just that male athletes are bigger, faster and stronger – but it’s a difference in kind. Pound for pound, male bodies are more athletic .

Evaluating trans athletes on a case-by-case basis

So, how can we allow trans athletes to compete without giving them an unfair advantage over their competitors?

One proposed solution, as if taken from the pages of novelist Kurt Vonnegut’s “ Harrison Bergeron ,” is testosterone-based handicapping for events . Competitors would have their testosterone levels measured and then algorithms would determine their advantage. Then, competitors would be fitted with weighted clothes, compete on a different track or otherwise receive an appropriate handicap before competing.

But having a higher level of testosterone does not automatically make you a better athlete . Beyond this, while handicapping may be fine for a golf outing with friends, it isn’t appropriate for serious athletic contests. The point of athletic competitions is to determine who is actually the best, not who is the best relative to handicaps.

Another proposed solution entails replacing gender divisions entirely with ability-level divisions . Yet this could hinder women’s participation in sports. In a world with no female-only divisions, Serena Williams would still win some tennis tournaments, but they likely wouldn’t be tournaments you’ve heard of.

So what’s the most viable solution to this debate?

Since there is no typical transgender athlete, broad rules for transgender athletes don’t seem appropriate.

Instead, language similar to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s disability accommodation policy could be used for transgender athletes: “ The decision as to the appropriate accommodation must be based on the particular facts of each case .”

“Men’s” divisions could be eliminated and replaced with “open” divisions. Any athlete could be allowed to compete in that division.

Then, transgender athletes could be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Based on their athletic ability, a tournament organizer could determine which division is most fair for them to compete in, “women’s” or “open.”

For trans women athletes, at issue is their athletic ability, not their womanhood. If a tournament organizer determines that a trans woman athlete is too good to compete against other women because of her biological advantage, requiring her to compete in an “open” division does not undermine her humanity.

Instead, this acknowledges – and takes seriously – that she identifies as a woman, but that respect for the principles of fair competition requires that she not be allowed to compete in the women’s division.

While whatever decision is made is unlikely to make all competitors happy, this approach seems to be the most fair and feasible given the relatively small number of transgender athletes and the unique circumstances of each athlete.

- Transgender

- Serena Williams

- Youth Sports

- Women's sports

- High school sports

- Mental health and sport

- Trans youth 2021

Head of Evidence to Action

Supply Chain - Assistant/Associate Professor (Tenure-Track)

Education Research Fellow

OzGrav Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Casual Facilitator: GERRIC Student Programs - Arts, Design and Architecture

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- JME Commentaries

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 45, Issue 6

- Transwomen in elite sport: scientific and ethical considerations

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1595-5454 Taryn Knox 1 ,

- Lynley C Anderson 1 ,

- Alison Heather 2

- 1 Bioethics Centre , University of Otago , Dunedin , New Zealand

- 2 Department of Physiology , University of Otago , Dunedin , New Zealand

- Correspondence to Associate Professor Lynley C Anderson, Bioethics Centre, University of Otago, Dunedin 9001, New Zealand; lynley.anderson{at}otago.ac.nz

The inclusion of elite transwomen athletes in sport is controversial. The recent International Olympic Committee (IOC) (2015) guidelines allow transwomen to compete in the women’s division if (amongst other things) their testosterone is held below 10 nmol/L. This is significantly higher than that of cis-women. Science demonstrates that high testosterone and other male physiology provides a performance advantage in sport suggesting that transwomen retain some of that advantage. To determine whether the advantage is unfair necessitates an ethical analysis of the principles of inclusion and fairness. Particularly important is whether the advantage held by transwomen is a tolerable or intolerable unfairness. We conclude that the advantage to transwomen afforded by the IOC guidelines is an intolerable unfairness. This does not mean transwomen should be excluded from elite sport but that the existing male/female categories in sport should be abandoned in favour of a more nuanced approach satisfying both inclusion and fairness.

- human dignity

- scientific research

- sexuality/gender

https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2018-105208

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Contributors All three authors contributed to the planning, drafting and editing of the article. AH researched and analysed the scientific evidence, and LA and TK applied this empirical evidence to the ethical issues. All three authors were responsible for the arguments made in the final version of this paper. TK did the majority of the groundwork (eg, literature review) and final editing and referencing of the article. LA is the guarantor and the corresponding author for the article.

Funding The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Other content recommended for you.

- What do we do about women athletes with testes? Melanie Joy Newbould, Journal of Medical Ethics, 2015

- Collider bias (aka sample selection bias) in observational studies: why the effects of hyperandrogenism in elite women’s sport are likely underestimated Nicolai Topstad Borgen, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2019

- Position statement: IOC framework on fairness, inclusion and non-discrimination on the basis of gender identity and sex variations Magali Martowicz et al., British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2022

- Caster Semenya, athlete classification, and fair equality of opportunity in sport Sigmund Loland, Journal of Medical Ethics, 2020

- Gender-specific psychosocial stressors influencing mental health among women elite and semielite athletes: a narrative review Michaela Pascoe et al., British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2022

- Sex, health, and athletes Rebecca M Jordan-Young et al., BMJ: British Medical Journal, 2014

- Determination and regulation of body composition in elite athletes Peter Sonksen, British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2018

- Leveling (down) the playing field: performance diminishments and fairness in sport Sebastian Jon Holmen et al., Journal of Medical Ethics, 2022

- On Loland’s conception of fair equality of opportunity in sport Lynley C Anderson et al., Journal of Medical Ethics, 2020

- When does an advantage become unfair? Empirical and normative concerns in Semenya’s case Silvia Camporesi, Journal of Medical Ethics, 2019

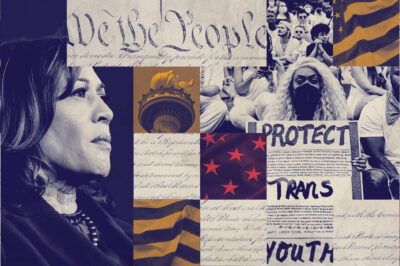

Four Myths About Trans Athletes, Debunked

For years state lawmakers have pushed legislation attempting to shut trans people out of public spaces. In 2020, lawmakers zeroed in on sports and introduced 20 bills seeking to ban trans people from participating in athletics. These statewide efforts have been supported through a coordinated campaign led by anti-LGBTQ groups that have long worked to attack our communities.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic shut down most state legislatures, Idaho became the first state to pass a sweeping ban on trans people’s participation in athletics from kindergarten through college. We, along with our partners, immediately sued . Advocates across the country are gearing up to continue the fight against these harmful bills in legislatures when they reconvene. In Connecticut, the ACLU is defending the rights of transgender athletes in a lawsuit brought by cisgender athletes seeking to strike down the state’s inclusive policy.

Though we are fighting every day in the courts and in legislatures, upholding trans rights will take more than judicial and legislative action. It will require rooting out the inaccurate and harmful beliefs underlying these policies. Below, we debunk four myths about trans athletes using the expertise of doctors, academics, and sports psychologists serving as experts in our litigation in Idaho .

FACT: Including trans athletes will benefit everyone.

Myth: the participation of trans athletes hurts cis women..

Many who oppose the inclusion of trans athletes erroneously claim that allowing trans athletes to compete will harm cisgender women. This divide and conquer tactic gets it exactly wrong. Excluding women who are trans hurts all women. It invites gender policing that could subject any woman to invasive tests or accusations of being “too masculine” or “too good” at their sport to be a “real” woman. In Idaho, the ACLU represents two young women, one trans and one cis, both of whom are hurt by the law that was passed targeting trans athletes.

Further, this myth reinforces stereotypes that women are weak and in need of protection. Politicians have used the “protection” trope time and time again, including in 2016 when they tried banning trans people from public restrooms by creating the debunked “bathroom predator” myth. The real motive is never about protection — it’s about excluding trans people from yet another public space. The arena of sports is no different.

On the other hand, including trans athletes will promote values of non-discrimination and inclusion among all student athletes. As longtime coach and sports policy expert Helen Carroll explains, efforts to exclude subsets of girls from sports, “can undermine team unity and also encourage divisiveness by policing who is ‘really’ a girl.” Dr. Mary Fry adds that youth derive the most benefits from athletics when they are exposed to caring environments where teammates are supported by each other and by coaches. Banning some girls from athletics because they are transgender undermines this cohesion and compromises the wide-ranging benefits that youth get from sports.

FACT: Trans athletes do not have an unfair advantage in sports.

Myth: trans athletes’ physiological characteristics provide an unfair advantage over cis athletes..

Women and girls who are trans face discrimination and violence that makes it difficult to even stay in school. According to the U.S. Trans Survey , 22 percent of trans women who were perceived as trans in school were harassed so badly they had to leave school because of it. Another 10 percent were kicked out of school. The idea that women and girls have an advantage because they are trans ignores the actual conditions of their lives.

Trans athletes vary in athletic ability just like cisgender athletes. “One high jumper could be taller and have longer legs than another, but the other could have perfect form, and then do better,” explains Andraya Yearwood , a student track athlete and ACLU client . “One sprinter could have parents who spend so much money on personal training for their child, which in turn, would cause that child to run faster," she adds. In Connecticut, where cisgender girl runners have tried to block Andraya from participating in the sport she loves, the very same cis girls who have claimed that trans athletes have an “unfair” advantage have consistently performed as well as or better than transgender competitors.

"A person’s genetic make-up and internal and external reproductive anatomy are not useful indicators of athletic performance,”according to Dr. Joshua D. Safer. “For a trans woman athlete who meets NCAA standards , “there is no inherent reason why her physiological characteristics related to athletic performance should be treated differently from the physiological characteristics of a non-transgender woman.”

FACT: Trans girls are girls.

Myth: sex is binary, apparent at birth, and identifiable through singular biological characteristics. .

Girls who are trans are told repeatedly that they are not “real” girls and boys who are trans are told they are not “real” boys. Non-binary people are told that their gender is not real and that they must be either boys or girls. None of these statements are true. Trans people are exactly who we say we are.

There is no one way for women’s bodies to be. Women, including women who are transgender, intersex, or disabled, have a range of different physical characteristics.

“A person’s sex is made up of multiple biological characteristics and they may not all align as typically male or female in a given person,” says Dr. Safer. Further, many people who are not trans can have hormones levels outside of the range considered typical of a cis person of their assigned sex.

When a person does not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth, they must be able to transition socially — and that includes participating in sports consistent with their gender identity. According to Dr. Deanna Adkins, excluding trans athletes can be deeply harmful and disruptive to treatment. “I know from experience with my patients that it can be extremely harmful for a transgender young person to be excluded from the team consistent with their gender identity.”

FACT: Trans people belong on the same teams as other students.

Myth: trans students need separate teams..

Trans people have the same right to play sports as anybody else. “For the past nine years,” explains Carroll , “transgender athletes have been able to compete on teams at NCAA member collegiates and universities consistent with their gender identity like all other student-athletes with no disruption to women’s collegiate sports.”

Excluding trans people from any space or activity is harmful, particularly for trans youth. A trans high school student, for example, may experience detrimental effects to their physical and emotional wellbeing when they are pushed out of affirming spaces and communities. As Lindsay Hecox says, “I just want to run.”

According to Dr. Adkins, “When a school or athletic organization denies transgender students the ability to participate equally in athletics because they are transgender, that condones, reinforces, and affirms the transgender students’ social status as outsiders or misfits who deserve the hostility they experience from peers.”

Believing and perpetuating myths and misconceptions about trans athletes is harmful. Denying trans people the right to participate is discrimination and it doesn’t just hurt trans people, it hurts all of us.

Learn More About the Issues on This Page

- LGBTQ Rights

- LGBTQ Youth

- Trans and Gender-Nonconforming Youth

- Transgender People and Discrimination

- Transgender Rights

Related Content

ACLU Announces Roadmap for Protecting and Expanding LGBTQ Freedom Under a Harris Administration

Why a Harris Presidency Promises Hope for LGBTQ Rights

Ohio Judge Rules Against Families and Doctors, Allowing Ban on Gender-Affirming Care to Take Immediate Effect

High School Students Explain Why We Can’t Let Classroom Censorship Win

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Transgender Women in the Female Category of Sport: Perspectives on Testosterone Suppression and Performance Advantage

Emma n. hilton.

1 Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK

Tommy R. Lundberg

2 Department of Laboratory Medicine/ANA Futura, Division of Clinical Physiology, Karolinska Institutet, Alfred Nobles Allé 8B, Huddinge, 141 52 Stockholm, Sweden

3 Unit of Clinical Physiology, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden

Associated Data

Available upon request.

Males enjoy physical performance advantages over females within competitive sport. The sex-based segregation into male and female sporting categories does not account for transgender persons who experience incongruence between their biological sex and their experienced gender identity. Accordingly, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) determined criteria by which a transgender woman may be eligible to compete in the female category, requiring total serum testosterone levels to be suppressed below 10 nmol/L for at least 12 months prior to and during competition. Whether this regulation removes the male performance advantage has not been scrutinized. Here, we review how differences in biological characteristics between biological males and females affect sporting performance and assess whether evidence exists to support the assumption that testosterone suppression in transgender women removes the male performance advantage and thus delivers fair and safe competition. We report that the performance gap between males and females becomes significant at puberty and often amounts to 10–50% depending on sport. The performance gap is more pronounced in sporting activities relying on muscle mass and explosive strength, particularly in the upper body. Longitudinal studies examining the effects of testosterone suppression on muscle mass and strength in transgender women consistently show very modest changes, where the loss of lean body mass, muscle area and strength typically amounts to approximately 5% after 12 months of treatment. Thus, the muscular advantage enjoyed by transgender women is only minimally reduced when testosterone is suppressed. Sports organizations should consider this evidence when reassessing current policies regarding participation of transgender women in the female category of sport.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40279-020-01389-3.

| Given that biological males experience a substantial performance advantage over females in most sports, there is currently a debate whether inclusion of transgender women in the female category of sports would compromise the objective of fair and safe competition. |

| Here, we report that current evidence shows the biological advantage, most notably in terms of muscle mass and strength, conferred by male puberty and thus enjoyed by most transgender women is only minimally reduced when testosterone is suppressed as per current sporting guidelines for transgender athletes. |

| This evidence is relevant for policies regarding participation of transgender women in the female category of sport. |

Introduction

Sporting performance is strongly influenced by a range of physiological factors, including muscle force and power-producing capacity, anthropometric characteristics, cardiorespiratory capacity and metabolic factors [ 1 , 2 ]. Many of these physiological factors differ significantly between biological males and females as a result of genetic differences and androgen-directed development of secondary sex characteristics [ 3 , 4 ]. This confers large sporting performance advantages on biological males over females [ 5 ].

When comparing athletes who compete directly against one another, such as elite or comparable levels of school-aged athletes, the physiological advantages conferred by biological sex appear, on assessment of performance data, insurmountable. Further, in sports where contact, collision or combat are important for gameplay, widely different physiological attributes may create safety and athlete welfare concerns, necessitating not only segregation of sport into male and female categories, but also, for example, into weight and age classes. Thus, to ensure that both men and women can enjoy sport in terms of fairness, safety and inclusivity, most sports are divided, in the first instance, into male and female categories.

Segregating sports by biological sex does not account for transgender persons who experience incongruence between their biological sex and their experienced gender identity, and whose legal sex may be different to that recorded at birth [ 6 , 7 ]. More specifically, transgender women (observed at birth as biologically male but identifying as women) may, before or after cross-hormone treatment, wish to compete in the female category. This has raised concerns about fairness and safety within female competition, and the issue of how to fairly and safely accommodate transgender persons in sport has been subject to much discussion [ 6 – 13 ].

The current International Olympic Committee (IOC) policy [ 14 ] on transgender athletes states that “it is necessary to ensure insofar as possible that trans athletes are not excluded from the opportunity to participate in sporting competition”. Yet the policy also states that “the overriding sporting objective is and remains the guarantee of fair competition”. As these goals may be seen as conflicting if male performance advantages are carried through to competition in the female category, the IOC concludes that “restrictions on participation are appropriate to the extent that they are necessary and proportionate to the achievement of that objective”.

Accordingly, the IOC determined criteria by which transgender women may be eligible to compete in the female category. These include a solemn declaration that her gender identity is female and the maintenance of total serum testosterone levels below 10 nmol/L for at least 12 months prior to competing and during competition [ 14 ]. Whilst the scientific basis for this testosterone threshold was not openly communicated by the IOC, it is surmised that the IOC believed this testosterone criterion sufficient to reduce the sporting advantages of biological males over females and deliver fair and safe competition within the female category.

Several studies have examined the effects of testosterone suppression on the changing biology, physiology and performance markers of transgender women. In this review, we aim to assess whether evidence exists to support the assumption that testosterone suppression in transgender women removes these advantages. To achieve this aim, we first review the differences in biological characteristics between biological males and females, and examine how those differences affect sporting performance. We then evaluate the studies that have measured elements of performance and physical capacity following testosterone suppression in untrained transgender women, and discuss the relevance of these findings to the supposition of fairness and safety (i.e. removal of the male performance advantage) as per current sporting guidelines.

The Biological Basis for Sporting Performance Advantages in Males

The physical divergence between males and females begins during early embryogenesis, when bipotential gonads are triggered to differentiate into testes or ovaries, the tissues that will produce sperm in males and ova in females, respectively [ 15 ]. Gonad differentiation into testes or ovaries determines, via the specific hormone milieu each generates, downstream in utero reproductive anatomy development [ 16 ], producing male or female body plans. We note that in rare instances, differences in sex development (DSDs) occur and the typical progression of male or female development is disrupted [ 17 ]. The categorisation of such athletes is beyond the scope of this review, and the impact of individual DSDs on sporting performance must be considered on their own merits.

In early childhood, prior to puberty, sporting participation prioritises team play and the development of fundamental motor and social skills, and is sometimes mixed sex. Athletic performance differences between males and females prior to puberty are often considered inconsequential or relatively small [ 18 ]. Nonetheless, pre-puberty performance differences are not unequivocally negligible, and could be mediated, to some extent, by genetic factors and/or activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis during the neonatal period, sometimes referred to as “minipuberty”. For example, some 6500 genes are differentially expressed between males and females [ 19 ] with an estimated 3000 sex-specific differences in skeletal muscle likely to influence composition and function beyond the effects of androgenisation [ 3 ], while increased testosterone during minipuberty in males aged 1–6 months may be correlated with higher growth velocity and an “imprinting effect” on BMI and bodyweight [ 20 , 21 ]. An extensive review of fitness data from over 85,000 Australian children aged 9–17 years old showed that, compared with 9-year-old females, 9-year-old males were faster over short sprints (9.8%) and 1 mile (16.6%), could jump 9.5% further from a standing start (a test of explosive power), could complete 33% more push-ups in 30 s and had 13.8% stronger grip [ 22 ]. Male advantage of a similar magnitude was detected in a study of Greek children, where, compared with 6-year-old females, 6-year-old males completed 16.6% more shuttle runs in a given time and could jump 9.7% further from a standing position [ 23 ]. In terms of aerobic capacity, 6- to 7-year-old males have been shown to have a higher absolute and relative (to body mass) V O 2max than 6- to 7-year-old females [ 24 ]. Nonetheless, while some biological sex differences, probably genetic in origin, are measurable and affect performance pre-puberty, we consider the effect of androgenizing puberty more influential on performance, and have focused our analysis on musculoskeletal differences hereafter.

Secondary sex characteristics that develop during puberty have evolved under sexual selection pressures to improve reproductive fitness and thus generate anatomical divergence beyond the reproductive system, leading to adult body types that are measurably different between sexes. This phenomenon is known as sex dimorphism. During puberty, testes-derived testosterone levels increase 20-fold in males, but remain low in females, resulting in circulating testosterone concentrations at least 15 times higher in males than in females of any age [ 4 , 25 ]. Testosterone in males induces changes in muscle mass, strength, anthropometric variables and hemoglobin levels [ 4 ], as part of the range of sexually dimorphic characteristics observed in humans.

Broadly, males are bigger and stronger than females. It follows that, within competitive sport, males enjoy significant performance advantages over females, predicated on the superior physical capacity developed during puberty in response to testosterone. Thus, the biological effects of elevated pubertal testosterone are primarily responsible for driving the divergence of athletic performances between males and females [ 4 ]. It is acknowledged that this divergence has been compounded historically by a lag in the cultural acceptance of, and financial provision for, females in sport that may have had implications for the rate of improvement in athletic performance in females. Yet, since the 1990s, the difference in performance records between males and females has been relatively stable, suggesting that biological differences created by androgenization explain most of the male advantage, and are insurmountable [ 5 , 26 , 27 ].

Table Table1 1 outlines physical attributes that are major parameters underpinning the male performance advantage [ 28 – 38 ]. Males have: larger and denser muscle mass, and stiffer connective tissue, with associated capacity to exert greater muscular force more rapidly and efficiently; reduced fat mass, and different distribution of body fat and lean muscle mass, which increases power to weight ratios and upper to lower limb strength in sports where this may be a crucial determinant of success; longer and larger skeletal structure, which creates advantages in sports where levers influence force application, where longer limb/digit length is favorable, and where height, mass and proportions are directly responsible for performance capacity; superior cardiovascular and respiratory function, with larger blood and heart volumes, higher hemoglobin concentration, greater cross-sectional area of the trachea and lower oxygen cost of respiration [ 3 , 4 , 39 , 40 ]. Of course, different sports select for different physiological characteristics—an advantage in one discipline may be neutral or even a disadvantage in another—but examination of a variety of record and performance metrics in any discipline reveals there are few sporting disciplines where males do not possess performance advantage over females as a result of the physiological characteristics affected by testosterone.

Selected physical difference between untrained/moderately trained males and females. Female levels are set as the reference value

| Variable | Magnitude of sex difference (%) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Body composition | ||

| Lean body mass | 45 | Lee et al. [ ] |

| Fat% | − 30 | |

| Muscle mass | ||

| Lower body | 33 | Janssen et al. [ ] |

| Upper body | 40 | |

| Muscle strength | ||

| Grip strength | 57 | Bohannon et al. [ ] |

| Knee extension peak torque | 54 | Neder et al. [ ] |

| Anthropometry and bone geometry | ||

| Femur length | 9.4 | Jantz et al. [ ] |

| Humerus length | 12.0 | Brinckmann et al. [ ] |

| Radius length | 14.6 | |

| Pelvic width relative to pelvis height | − 6.1 | |

| Tendon properties | ||

| Force | 83 | Lepley et al. [ ] |

| Stiffness | 41 | |

| O | ||

| Absolute values | 50 | Pate et al. [ ] |

| Relative values | 25 | |

| Respiratory function | ||

| Pulmonary ventilation (maximal) | 48 | Åstrand et al. [ ] |

| Cardiovascular function | ||

| Left ventricular mass | 31 | Åstrand et al. [ ] |

| Cardiac output (rest) | 22 | Best et al. [ ] |

| Cardiac output (maximal) | 30 | Tong et al. [ ] |

| Stroke volume (rest) | 43 | |

| Stroke volume (maximal) | 34 | |

| Hemoglobin concentration | 11 | |

Sports Performance Differences Between Males and Females

An overview of elite adult athletes.

A comparison of adult elite male and female achievements in sporting activities can quantify the extent of the male performance advantage. We searched publicly available sports federation databases and/or tournament/competition records to identify sporting metrics in various events and disciplines, and calculated the performance of males relative to females. Although not an exhaustive list, examples of performance gaps in a range of sports with various durations, physiological performance determinants, skill components and force requirements are shown in Fig. 1 .

The male performance advantage over females across various selected sporting disciplines. The female level is set to 100%. In sport events with multiple disciplines, the male value has been averaged across disciplines, and the error bars represent the range of the advantage. The metrics were compiled from publicly available sports federation databases and/or tournament/competition records. MTB mountain bike

The smallest performance gaps were seen in rowing, swimming and running (11–13%), with low variation across individual events within each of those categories. The performance gap increases to an average of 16% in track cycling, with higher variation across events (from 9% in the 4000 m team pursuit to 24% in the flying 500 m time trial). The average performance gap is 18% in jumping events (long jump, high jump and triple jump). Performance differences larger than 20% are generally present when considering sports and activities that involve extensive upper body contributions. The gap between fastest recorded tennis serve is 20%, while the gaps between fastest recorded baseball pitches and field hockey drag flicks exceed 50%.

Sports performance relies to some degree on the magnitude, speed and repeatability of force application, and, with respect to the speed of force production (power), vertical jump performance is on average 33% greater in elite men than women, with differences ranging from 27.8% for endurance sports to in excess of 40% for precision and combat sports [ 41 ]. Because implement mass differs, direct comparisons are not possible in throwing events in track and field athletics. However, the performance gap is known to be substantial, and throwing represents the widest sex difference in motor performance from an early age [ 42 ]. In Olympic javelin throwers, this is manifested in differences in the peak linear velocities of the shoulder, wrist, elbow and hand, all of which are 13–21% higher for male athletes compared with females [ 43 ].

The increasing performance gap between males and females as upper body strength becomes more critical for performance is likely explained to a large extent by the observation that males have disproportionately greater strength in their upper compared to lower body, while females show the inverse [ 44 , 45 ]. This different distribution of strength compounds the general advantage of increased muscle mass in upper body dominant disciplines. Males also have longer arms than females, which allows greater torque production from the arm lever when, for example, throwing a ball, punching or pushing.

Olympic Weightlifting

In Olympic weightlifting, where weight categories differ between males and females, the performance gap is between 31 and 37% across the range of competitive body weights between 1998 and 2020 (Fig. 1 ). It is important to note that at all weight categories below the top/open category, performances are produced within weight categories with an upper limit, where strength can be correlated with “fighting weight”, and we focused our analysis of performance gaps in these categories.

To explore strength–mass relationships further, we compared Olympic weightlifting data between equivalent weight categories which, to some extent, limit athlete height, to examine the hypothesis that male performance advantage may be largely (or even wholly) mediated by increased height and lever-derived advantages (Table (Table2). 2 ). Between 1998 and 2018, a 69 kg category was common to both males and females, with the male record holder (69 kg, 1.68 m) lifting a combined weight 30.1% heavier than the female record holder (69 kg, 1.64 m). Weight category changes in 2019 removed the common 69 kg category and created a common 55 kg category. The current male record holder (55 kg, 1.52 m) lifts 29.5% heavier than the female record holder (55 kg, 1.52 m). These comparisons demonstrate that males are approximately 30% stronger than females of equivalent stature and mass. However, importantly, male vs. female weightlifting performance gaps increase with increasing bodyweight. For example, in the top/open weight category of Olympic weightlifting, in the absence of weight (and associated height) limits, maximum male lifting strength exceeds female lifting strength by nearly 40%. This is further manifested in powerlifting, where the male record (total of squat, bench press and deadlift) is 65% higher than the female record in the open weight category of the World Open Classic Records. Further analysis of Olympic weightlifting data shows that the 55-kg male record holder is 6.5% stronger than the 69-kg female record holder (294 kg vs 276 kg), and that the 69-kg male record is 3.2% higher than the record held in the female open category by a 108-kg female (359 kg vs 348 kg). This Olympic weightlifting analysis reveals key differences between male and female strength capacity. It shows that, even after adjustment for mass, biological males are significantly stronger (30%) than females, and that females who are 60% heavier than males do not overcome these strength deficits.

Olympic weightlifting data between equivalent male–female and top/open weight categories

| Sex | Weight (kg) | Height (m) | Combined record (kg) | Strength to weight ratio | Relative performance (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 record in the 55 kg weight-limited category | ||||||

| Liao Qiuyun | F | 55 | 1.52 | 227 | 4.13 | |

| Om Yun-chol | M | 55 | 1.52 | 294 | 5.35 | 29.5 |

| 1998–2018 record in the 69-kg weight-limited category | ||||||

| Oxsana Slivenko | F | 69 | 1.64 | 276 | 4.00 | |

| Liao Hui | M | 69 | 1.68 | 359 | 5.20 | 30.1 |

| Comparative performances for top/open categories (all time heaviest combined lifts) | ||||||

| Tatiana Kashirina | F | 108 | 1.77 | 348 | 3.22 | |

| Lasha Talakhadze | M | 168 | 1.97 | 484 | 2.88 | 39.1 |

F female, M male

Perspectives on Elite Athlete Performance Differences

Figure 1 illustrates the performance gap between adult elite males and adult elite females across various sporting disciplines and activities. The translation of these advantages, assessed as the performance difference between the very best males and very best females, are significant when extended and applied to larger populations. In running events, for example, where the male–female gap is approximately 11%, it follows that many thousands of males are faster than the very best females. For example, approximately 10,000 males have personal best times that are faster than the current Olympic 100 m female champion (World Athletics, personal communication, July 2019). This has also been described elsewhere [ 46 , 47 ], and illustrates the true effect of an 11% typical difference on population comparisons between males and females. This is further apparent upon examination of selected junior male records, which surpass adult elite female performances by the age of 14–15 years (Table (Table3), 3 ), demonstrating superior male athletic performance over elite females within a few years of the onset of puberty.

Selected junior male records in comparison with adult elite female records

| Event | Schoolboy male record | Elite female (adult) record |

|---|---|---|

| 100 m | 10.20 (age 15) | 10.49 |

| 800 m | 1:51.23 (age 14) | 1:53.28 |

| 1500 m | 3:48.37 (age 14) | 3:50.07 |

| Long jump | 7.85 m (age 15) | 7.52 m |

| Discus throw | 77.68 m (age 15) | 76.80 m |

Time format: minutes:seconds.hundredths of a second

These data overwhelmingly confirm that testosterone-driven puberty, as the driving force of development of male secondary sex characteristics, underpins sporting advantages that are so large no female could reasonably hope to succeed without sex segregation in most sporting competitions. To ensure, in light of these analyses, that female athletes can be included in sporting competitions in a fair and safe manner, most sports have a female category the purpose of which is the protection of both fairness and, in some sports, safety/welfare of athletes who do not benefit from the physiological changes induced by male levels of testosterone from puberty onwards.

Performance Differences in Non-elite Individuals

The male performance advantages described above in athletic cohorts are similar in magnitude in untrained people. Even when expressed relative to fat-free weight, V O 2max is 12–15% higher in males than in females [ 48 ]. Records of lower-limb muscle strength reveal a consistent 50% difference in peak torque between males and females across the lifespan [ 31 ]. Hubal et al. [ 49 ] tested 342 women and 243 men for isometric (maximal voluntary contraction) and dynamic strength (one-repetition maximum; 1RM) of the elbow flexor muscles and performed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the biceps brachii to determine cross-sectional area. The males had 57% greater muscle size, 109% greater isometric strength, and 89% greater 1RM strength than age-matched females. This reinforces the finding in athletic cohorts that sex differences in muscle size and strength are more pronounced in the upper body.

Recently, sexual dimorphism in arm force and power was investigated in a punch motion in moderately-trained individuals [ 50 ]. The power produced during a punch was 162% greater in males than in females, and the least powerful man produced more power than the most powerful woman. This highlights that sex differences in parameters such as mass, strength and speed may combine to produce even larger sex differences in sport-specific actions, which often are a product of how various physical capacities combine. For example, power production is the product of force and velocity, and momentum is defined as mass multiplied by velocity. The momentum and kinetic energy that can be transferred to another object, such as during a tackle or punch in collision and combat sports are, therefore, dictated by: the mass; force to accelerate that mass, and; resultant velocity attained by that mass. As there is a male advantage for each of these factors, the net result is likely synergistic in a sport-specific action, such as a tackle or a throw, that widely surpasses the sum of individual magnitudes of advantage in isolated fitness variables. Indeed, already at 17 years of age, the average male throws a ball further than 99% of 17-year-old females [ 51 ], despite no single variable (arm length, muscle mass etc.) reaching this numerical advantage. Similarly, punch power is 162% greater in men than women even though no single parameter that produces punching actions achieves this magnitude of difference [ 50 ].

Is the Male Performance Advantage Lost when Testosterone is Suppressed in Transgender Women?

The current IOC criteria for inclusion of transgender women in female sports categories require testosterone suppression below 10 nmol/L for 12 months prior to and during competition. Given the IOC’s stated position that the “overriding sporting objective is and remains the guarantee of fair competition” [ 14 ] , it is reasonable to assume that the rationale for this requirement is that it reduces the male performance advantages described previously to an acceptable degree, thus permitting fair and safe competition. To determine whether this medical intervention is sufficient to remove (or reduce) the male performance advantage, which we described above, we performed a systematic search of the scientific literature addressing anthropometric and muscle characteristics of transgender women. Search terms and filtering of peer-reviewed data are given in Supplementary Table S1.

Anthropometrics

Given its importance for the general health of the transgender population, there are multiple studies of bone health, and reviews of these data. To summarise, transgender women often have low baseline (pre-intervention) bone mineral density (BMD), attributed to low levels of physical activity, especially weight-bearing exercise, and low vitamin D levels [ 52 , 53 ]. However, transgender women generally maintain bone mass over the course of at least 24 months of testosterone suppression. There may even be small but significant increases in BMD at the lumbar spine [ 54 , 55 ]. Some retrieved studies present data pertaining to maintained BMD in transgender women after many years of testosterone suppression. One such study concluded that “BMD is preserved over a median of 12.5 years” [ 56 ]. In support, no increase in fracture rates was observed over 12 months of testosterone suppression [ 54 ]. Current advice, including that from the International Society for Clinical Densitometry, is that transgender women, in the absence of other risk factors, do not require monitoring of BMD [ 52 , 57 ]. This is explicable under current standard treatment regimes, given the established positive effect of estrogen, rather than testosterone, on bone turnover in males [ 58 ].

Given the maintenance of BMD and the lack of a plausible biological mechanism by which testosterone suppression might affect skeletal measurements such as bone length and hip width, we conclude that height and skeletal parameters remain unaltered in transgender women, and that sporting advantage conferred by skeletal size and bone density would be retained despite testosterone reductions compliant with the IOC’s current guidelines. This is of particular relevance to sports where height, limb length and handspan are key (e.g. basketball, volleyball, handball) and where high movement efficiency is advantageous. Male bone geometry and density may also provide protection against some sport-related injuries—for example, males have a lower incidence of knee injuries, often attributed to low quadriceps ( Q ) angle conferred by a narrow pelvic girdle [ 59 , 60 ].

Muscle and Strength Metrics

As discussed earlier, muscle mass and strength are key parameters underpinning male performance advantages. Strength differences range between 30 and 100%, depending upon the cohort studied and the task used to assess strength. Thus, given the important contribution made by strength to performance, we sought studies that have assessed strength and muscle/lean body mass changes in transgender women after testosterone reduction. Studies retrieved in our literature search covered both longitudinal and cross-sectional analyses. Given the superior power of the former study type, we will focus on these.

The pioneer work by Gooren and colleagues, published in part in 1999 [ 61 ] and in full in 2004 [ 62 ], reported the effects of 1 and 3 years of testosterone suppression and estrogen supplementation in 19 transgender women (age 18–37 years). After the first year of therapy, testosterone levels were reduced to 1 nmol/L, well within typical female reference ranges, and remained low throughout the study course. As determined by MRI, thigh muscle area had decreased by − 9% from baseline measurement. After 3 years, thigh muscle area had decreased by a further − 3% from baseline measurement (total loss of − 12% over 3 years of treatment). However, when compared with the baseline measurement of thigh muscle area in transgender men (who are born female and experience female puberty), transgender women retained significantly higher thigh muscle size. The final thigh muscle area, after three years of testosterone suppression, was 13% larger in transwomen than in the transmen at baseline ( p < 0.05). The authors concluded that testosterone suppression in transgender women does not reverse muscle size to female levels.

Including Gooren and Bunck [ 62 ], 12 longitudinal studies [ 53 , 63 – 73 ] have examined the effects of testosterone suppression on lean body mass or muscle size in transgender women. The collective evidence from these studies suggests that 12 months, which is the most commonly examined intervention period, of testosterone suppression to female-typical reference levels results in a modest (approximately − 5%) loss of lean body mass or muscle size (Table (Table4). 4 ). No study has reported muscle loss exceeding the − 12% found by Gooren and Bunck after 3 years of therapy. Notably, studies have found very consistent changes in lean body mass (using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) after 12 months of treatment, where the change has always been between − 3 and − 5% on average, with slightly greater reductions in the arm compared with the leg region [ 68 ]. Thus, given the large baseline differences in muscle mass between males and females (Table (Table1; 1 ; approximately 40%), the reduction achieved by 12 months of testosterone suppression can reasonably be assessed as small relative to the initial superior mass. We, therefore, conclude that the muscle mass advantage males possess over females, and the performance implications thereof, are not removed by the currently studied durations (4 months, 1, 2 and 3 years) of testosterone suppression in transgender women. In sports where muscle mass is important for performance, inclusion is therefore only possible if a large imbalance in fairness, and potentially safety in some sports, is to be tolerated.

Longitudinal studies of muscle and strength changes in adult transgender women undergoing cross-sex hormone therapy

| Study | Participants (age) | Therapy | Confirmed serum testosterone levels | Muscle/strength data | Comparison with reference females |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polderman et al. [ ] | = 12 TW 18–36 yr (age range) | T suppression + E supplementation | < 2 nmol/L at 4 mo |

4 mo − 2.2% |

4 mo 16% |

| Gooren and Bunck [ ] | = 19 TW 26 ± 6 yr | T suppression + E supplementation | ≤ 1 nmol/L at 1 and 3 yr |

1 yr − 9% / 3 yr -12% |

1 yr 16%/3 yr 13% |

| Haraldsen et al. [ ] | = 12 TW 29 ± 8 yr | E supplementation | < 10 nmol/L at 3 mo and 1 yr |

3 mo/1 yr—small changes, unclear magnitude | |

| Mueller et al. [ ] | = 84 TW 36 ± 11 yr | T suppression + E supplementation | ≤ 1 nmol/L at 1 and 2 yr |

1 yr − 4%/2 yr − 7% | |

| Wierckx et al. [ ] | = 53 TW 31 ± 14 yr | T suppression + E supplementation | < 10 nmol/L at 1 yr |

1 yr − 5% |

1 yr 39% |

Van Caenegem et al. [ ] (and Van Caenegem et al. [ ]) | = 49 TW 33 ± 14 yr | T suppression + E supplementation | ≤ 1 nmol/L at 1 and 2 yr |

1 yr − 4%/2 yr − 0.5%

1 yr − 7%/2 yr − 9%

1 yr − 2%/2 yr − 4%

1 yr − 8%/2 yr − 4% |

1 yr 24%/2 yr 28%

1 yr 26%/2 yr 23%

1 yr 16%/2 yr 13%

1 yr 29%/2 yr 34% |

| Gava et al. [ ] | = 40 TW 31 ± 10 yr | T suppression + E supplementation | < 5 nmol/L at 6 mo and ≤ 1 nmol/L at 1 yr |

1 yr − 2% | |

| Auer et al. [ ] | = 45 TW 35 ± 1 (SE) yr | T suppression + E supplementation | < 5 nmol/L at 1 yr |

1 yr − 3% |

1 yr 27% |

| Klaver et al. [ ] | = 179 TW 29 (range 18–66) | T suppression + E supplementation | ≤ 1 nmol/L at 1 yr |

Total − 3% Arm region − 6% Trunk region − 2% Android region 0% Gynoid region − 3% Leg region − 4% |

Total 18% Arm region 28% Leg region 19% |

| Fighera et al. [ ] | = 46 TW 34 ± 10 | E supplementation with or without T suppression | < 5 nmol/L at 3 mo ≤ 1 nmol/L at 31 mo |

31 mo − 4% from the 3 mo visit | |

| Scharff et al. [ ] | = 249 TW 28 (inter quartile range 23–40) | T suppression + E supplementation | ≤ 1 nmol/L at 1 yr |

1 yr − 4% |

1 yr 21% |

| Wiik et al. [ ] | = 11 TW 27 ± 4 | T suppression + E supplementation | ≤ 1 nmol/L at 4 mo and at 1 yr |

1 yr − 5%

1 yr − 4%

1 yr 2%

1 yr 3% |

1 yr 33%

26%

41%

33% |

Studies reporting measures of lean mass, muscle volume, muscle area or strength are included. Muscle/strength data are calculated in reference to baseline cohort data and, where reported, reference female (or transgender men before treatment) cohort data. Tack et al. [ 72 ] was not included in the table since some of the participants had not completed full puberty at treatment initiation. van Caenegem et al. [ 76 ] reports reference female values measured in a separately-published, parallel cohort of transgender men

N number of participants, TW transgender women, Yr year, Mo month, T testosterone, E estrogen. ± Standard deviation (unless otherwise indicated in text), LBM lean body mass, ALM appendicular lean mass

To provide more detailed information on not only gross body composition but also thigh muscle volume and contractile density, Wiik et al. [ 71 ] recently carried out a comprehensive battery of MRI and computed tomography (CT) examinations before and after 12 months of successful testosterone suppression and estrogen supplementation in 11 transgender women. Thigh volume (both anterior and posterior thigh) and quadriceps cross-sectional area decreased − 4 and − 5%, respectively, after the 12-month period, supporting previous results of modest effects of testosterone suppression on muscle mass (see Table Table4). 4 ). The more novel measure of radiological attenuation of the quadriceps muscle, a valid proxy of contractile density [ 74 , 75 ], showed no significant change in transgender women after 12 months of treatment, whereas the parallel group of transgender men demonstrated a + 6% increase in contractile density with testosterone supplementation.

As indicated earlier (e.g. Table Table1), 1 ), the difference in muscle strength between males and females is often more pronounced than the difference in muscle mass. Unfortunately, few studies have examined the effects of testosterone suppression on muscle strength or other proxies of performance in transgender individuals. The first such study was published online approximately 1 year prior to the release of the current IOC policy. In this study, as well as reporting changes in muscle size, van Caenegem et al. [ 53 ] reported that hand-grip strength was reduced from baseline measurements by − 7% and − 9% after 12 and 24 months, respectively, of cross-hormone treatment in transgender women. Comparison with data in a separately-published, parallel cohort of transgender men [ 76 ] demonstrated a retained hand-grip strength advantage after 2 years of 23% over female baseline measurements (a calculated average of baseline data obtained from control females and transgender men).

In a recent multicenter study [ 70 ], examination of 249 transgender women revealed a decrease of − 4% in grip strength after 12 months of cross-hormone treatment, with no variation between different testosterone level, age or BMI tertiles (all transgender women studied were within female reference ranges for testosterone). Despite this modest reduction in strength, transgender women retained a 17% grip strength advantage over transgender men measured at baseline. The authors noted that handgrip strength in transgender women was in approximately the 25th percentile for males but was over the 90th percentile for females, both before and after hormone treatment. This emphasizes that the strength advantage for males over females is inherently large. In another study exploring handgrip strength, albeit in late puberty adolescents, Tack et al. noted no change in grip strength after hormonal treatment (average duration 11 months) of 21 transgender girls [ 72 ].

Although grip strength provides an excellent proxy measurement for general strength in a broad population, specific assessment within different muscle groups is more valuable in a sports-specific framework. Wiik et al., [ 71 ] having determined that thigh muscle mass reduces only modestly, and that no significant changes in contractile density occur with 12 months of testosterone suppression, provided, for the first time, data for isokinetic strength measurements of both knee extension and knee flexion. They reported that muscle strength after 12 months of testosterone suppression was comparable to baseline strength. As a result, transgender women remained about 50% stronger than both the group of transgender men at baseline and a reference group of females. The authors suggested that small neural learning effects during repeated testing may explain the apparent lack of small reductions in strength that had been measured in other studies [ 71 ].

These longitudinal data comprise a clear pattern of very modest to negligible changes in muscle mass and strength in transgender women suppressing testosterone for at least 12 months. Muscle mass and strength are key physical parameters that constitute a significant, if not majority, portion of the male performance advantage, most notably in those sports where upper body strength, overall strength, and muscle mass are crucial determinants of performance. Thus, our analysis strongly suggests that the reduction in testosterone levels required by many sports federation transgender policies is insufficient to remove or reduce the male advantage, in terms of muscle mass and strength, by any meaningful degree. The relatively consistent finding of a minor (approximately − 5%) muscle loss after the first year of treatment is also in line with studies on androgen-deprivation therapy in males with prostate cancer, where the annual loss of lean body mass has been reported to range between − 2 and − 4% [ 77 ].

Although less powerful than longitudinal studies, we identified one major cross-sectional study that measured muscle mass and strength in transgender women. In this study, 23 transgender women and 46 healthy age- and height-matched control males were compared [ 78 ]. The transgender women were recruited at least 3 years after sex reassignment surgery, and the mean duration of cross-hormone treatment was 8 years. The results showed that transgender women had 17% less lean mass and 25% lower peak quadriceps muscle strength than the control males [ 78 ]. This cross-sectional comparison suggests that prolonged testosterone suppression, well beyond the time period mandated by sports federations substantially reduces muscle mass and strength in transgender women. However, the typical gap in lean mass and strength between males and females at baseline (Table (Table1) 1 ) exceeds the reductions reported in this study [ 78 ]. The final average lean body mass of the transgender women was 51.2 kg, which puts them in the 90th percentile for women [ 79 ]. Similarly, the final grip strength was 41 kg, 25% higher than the female reference value [ 80 ]. Collectively, this implies a retained physical advantage even after 8 years of testosterone suppression. Furthermore, given that cohorts of transgender women often have slightly lower baseline measurements of muscle and strength than control males [ 53 ], and baseline measurements were unavailable for the transgender women of this cohort, the above calculations using control males reference values may be an overestimate of actual loss of muscle mass and strength, emphasizing both the need for caution when analyzing cross-sectional data in the absence of baseline assessment and the superior power of longitudinal studies quantifying within-subject changes.

Endurance Performance and Cardiovascular Parameters