Essays About Conflict in Life: Top 5 Examples and Prompts

Conflict is a broad and gripping topic, but most struggle to write about it. See our top essays about conflict in life examples and prompts to start your piece.

Conflict occurs when two people with different opinions, feelings, and behaviours disagree. It’s a common occurrence that we can observe wherever and whenever we are. Although conflicts usually imply negative aspects, they also have benefits such as stronger relationships and better communication.

To aid you in your paper, here are five examples to familiarize you with the subject:

| IMAGE | PRODUCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Grammarly | ||

| ProWritingAid |

1. Useful Notes On 4 Major Types Of Conflicts (Motivational Conflict) By Raghavendra Pras

2. encountering conflict by julius gregory, 3. complete guide to understanding conflict and conflict resolution by prasanna, 4. analysis of personal conflict experience by anonymous on gradesfixer, 5. personal conflict resolving skills essay by anonymous on ivypanda, 1. conflict: what is and how to avoid it, 2. conflicts in our everyday lives, 3. review on movies or books about conflicts, 4. actions and conflicts , 5. conflicts at home, 6. conflicts that changed my life, 7. my personal experience in covert conflict, 8. cascading conflicts, 9. how does conflict in life benefit you, 10. the importance of conflict management.

“Conflict… results when two or more motives drive behaviour towards incompatible goals.”

Pras regards conflict as a source of frustration with four types. Experimental psychologists identified them as approach-approach, avoidance-avoidance, approach-avoidance, and multiple approach-avoidance. He discusses each through his essay and uses theoretical analysis with real-life examples to make it easier for the readers to understand.

“The nature of conflict shows that conflict can either push people away or bring them into having a closer, more comfortable relationship.”

The main points of Gregory’s essay are the typical causes and effects of conflicts. He talks about how people should not avoid conflicts in their life and instead solve them to learn and grow. However, he’s also aware that no matter if a dispute is big or small, it can lead to severe consequences when it’s wrongly dealt with. He also cites real-life events to prove his points. At the end of the essay, he acknowledges that one can’t wholly avoid conflict because it’s part of human nature.

“…it is important to remember that regardless of the situation, it is always possible to resolve a conflict in some constructive or meaningful way.”

To help the reader understand conflict and resolutions, Prasanna includes the types, causes, difficulties, and people’s reactions to it. She shows how broad conflict is by detailing each section. From simple misunderstandings to bad faith, the conflict has varying results that ultimately depend on the individuals involved in the situation. Prasanna ends the essay by saying that conflict is a part of life that everyone will have to go through, no matter the relationship they have with others.

“I also now understand that trying to keep someone’s feelings from getting hurt might not always be the best option during a conflict.”

To analyze how conflict impacts lives, the author shares his personal experience. He refers to an ex-friend, Luke, as someone who most of their circle doesn’t like because of his personality. The author shares their arguments, such as when Luke wasn’t invited to a party and how they tried to protect his feelings by not telling Luke people didn’t want him to be there. Instead, they caved, and Luke was allowed to the gathering. However, Luke realized he wasn’t accepted at the party, and many were uncomfortable around him.

The essay further narrates that it was a mistake not to be honest from the beginning. Ultimately, the writer states that he would immediately tell someone the truth rather than make matters worse.

“To me if life did not have challenges and difficult circumstances we were never going to know the strength that we have in us.”

The essay delves into the writer’s conflicts concerning their personal feelings and professional boundaries. The author narrates how they initially had a good relationship with a senior until they filed for a leave. Naturally, they didn’t expect the coworker to lie and bring the situation to their committee. However, the author handled it instead of showing anger by respecting their relationship with the senior, controlling their emotion, and communicating properly.

10 Helpful Prompts On Essays About Conflict in Life

Below are easy writing prompts to use for your essay:

Define what constitutes a conflict and present cases to make it easier for the readers to imagine. To further engage your audience, give them imaginary situations where they can choose how to react and include the results of these reactions.

If writing this prompt sounds like a lot of work, make it simple. Write a 5-paragraph essay instead.

There are several types of conflict that a person experiences throughout their life. First, discuss simple conflicts you observe around you. For example, the cashier misunderstands an order, your mom forgets to buy groceries, or you have clashing class schedules.

Pick a movie or book and summarize its plot. Share your thoughts regarding how the piece tackles the conflicts and if you agree with the characters’ decisions. Try the 1985 movie The Heavenly Kid , directed by Cary Medoway, or Where the Conflict Really Lies: Science, Religion, and Naturalism by philosopher Alvin Plantinga.

In this essay, describe how actions can lead to conflict and how specific actions can make a conflict worse. Make your essay interesting by presenting various characters and letting them react differently to a particular conflict.

For example, Character A responds by being angry and making the situation worse. Meanwhile, Character B immediately solves the discord by respectfully asking others for their reasons. Through your essay, you’ll help your readers realize how actions significantly affect conflicts. You’ll also be able to clearly explain what conflicts are.

Your home is where you first learn how to handle conflicts, making it easier for your readers to relate to you. In your essay, tell a story of when you quarreled with a relative and how you worked it out. For instance, you may have a petty fight with your sibling because you don’t want to share a toy. Then, share what your parents asked you to do and what you learned from your dispute.

If there are simple conflicts with no serious consequences, there are also severe ones that can impact individuals in the long run. Talk about it through your essay if you’re comfortable sharing a personal experience. For example, if your parents’ conflict ended in divorce, recount what it made you feel and how it affected your life.

Covert conflict occurs when two individuals have differences but do not openly discuss them. Have you experienced living or being with someone who avoids expressing their genuine feelings and emotions towards you or something? Write about it, what happened, and how the both of you resolved it.

Some results of cascading conflict are wars and revolutions. The underlying issues stem from a problem with a simple solution but will affect many aspects of the culture or community. For this prompt, pick a relevant historical happening. For instance, you can talk about King Henry VIII’s demand to divorce his first wife and how it changed the course of England’s royal bloodline and nobles.

People avoid conflict as much as possible because of its harmful effects, such as stress and fights. In this prompt, focus on its positive side. Discuss the pros of engaging in disputes, such as having better communication and developing your listening and people skills.

Explain what conflict management is and expound on its critical uses. Start by relaying a situation and then applying conflict resolution techniques. For example, you can talk about a team with difficulties making a united decision. To solve this conflict, the members should share their ideas and ensure everyone is allowed to speak and be heard.

Here are more essay writing tips to help you with your essay.

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

124 Conflict Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Writing an essay on conflict can be both challenging and thought-provoking. Conflict is an unavoidable aspect of human existence, and it can manifest in various forms, such as interpersonal conflicts, societal conflicts, or even conflicts within oneself. To help you explore this complex topic, here are 124 conflict essay topic ideas and examples that can serve as a source of inspiration for your writing.

Interpersonal Conflicts:

- The impact of communication breakdown on interpersonal conflicts.

- Resolving conflicts in romantic relationships: Strategies for success.

- The role of empathy in resolving conflicts between friends.

- The influence of cultural differences on interpersonal conflicts.

- The effects of social media on conflict resolution in friendships.

- The connection between conflict and power dynamics in relationships.

- Conflict resolution strategies for dealing with difficult family members.

- The role of compromise in resolving conflicts between siblings.

- The impact of unresolved childhood conflicts on adult relationships.

- Conflict management techniques for resolving workplace disputes.

Societal Conflicts: 11. The causes and consequences of political conflicts in developing countries. 12. The role of social media in fueling societal conflicts. 13. The impact of religious conflicts on society. 14. The influence of socioeconomic disparities on societal conflicts. 15. The role of education in preventing societal conflicts. 16. The effects of ethnic conflicts on economic development. 17. The connection between gender inequality and societal conflicts. 18. The impact of globalization on societal conflicts. 19. The role of media in perpetuating societal conflicts. 20. Conflict resolution strategies for addressing racial tensions in society.

Internal Conflicts: 21. Exploring the internal conflict between personal desires and societal expectations. 22. The impact of self-doubt on internal conflicts. 23. Overcoming internal conflicts between ambition and contentment. 24. The role of fear in internal conflicts. 25. The connection between guilt and internal conflicts. 26. The effects of trauma on internal conflicts. 27. The influence of cultural norms on internal conflicts. 28. The role of self-reflection in resolving internal conflicts. 29. The impact of unresolved internal conflicts on mental health. 30. Strategies for achieving inner peace amidst internal conflicts.

Conflict in Literature and Film: 31. Analyzing the theme of conflict in Shakespeare's plays. 32. The portrayal of societal conflicts in dystopian literature. 33. Exploring the internal conflicts of the protagonist in a novel. 34. The role of external conflicts in driving the plot of a film. 35. The influence of conflict on character development in literature. 36. The depiction of interpersonal conflicts in romantic comedies. 37. The effects of war-related conflicts in historical novels. 38. Analyzing the symbolism of conflict in a poem. 39. The portrayal of family conflicts in contemporary literature. 40. The impact of moral conflicts on the actions of a film's protagonist.

Global Conflicts: 41. The causes and consequences of wars in the Middle East. 42. The role of diplomacy in resolving global conflicts. 43. The impact of climate change on international conflicts. 44. Analyzing the conflict between developed and developing nations. 45. The influence of resource scarcity on global conflicts. 46. The connection between terrorism and global conflicts. 47. The effects of colonialism on current global conflicts. 48. The role of international organizations in preventing conflicts. 49. The impact of nuclear weapons on global conflicts. 50. Conflict resolution strategies for achieving world peace.

Conflict in History: 51. The causes and outcomes of the American Civil War. 52. Analyzing the conflicts of World War I from multiple perspectives. 53. The influence of ideological conflicts on the Cold War. 54. The effects of colonial conflicts on the decolonization process. 55. The connection between religious conflicts and the Crusades. 56. The impact of territorial disputes on conflicts in Southeast Asia. 57. Exploring the conflicts surrounding the French Revolution. 58. The role of nationalism in fueling conflicts in the Balkans. 59. The effects of conflicts on the rise and fall of empires. 60. Analyzing the conflicts during the Civil Rights Movement.

Conflict in Science and Technology: 61. The ethical dilemmas and conflicts in genetic engineering. 62. The impact of conflicts between scientific progress and religious beliefs. 63. The role of conflicts in the development of artificial intelligence. 64. Analyzing conflicts between privacy and surveillance in the digital age. 65. The effects of conflicts between environmental conservation and industrial development. 66. The connection between conflicts in scientific research and funding. 67. The influence of conflicts over intellectual property in technology. 68. Exploring conflicts in bioethics and medical advancements. 69. The impact of conflicts between scientific evidence and public opinion. 70. Analyzing conflicts in the regulation of emerging technologies.

Conflict in Sports: 71. The effects of conflicts between athletes and team management. 72. The role of conflicts in sports rivalries. 73. Analyzing conflicts between players and referees in sports. 74. The impact of conflicts between fans and players on sports events. 75. The connection between conflicts in sports and nationalism. 76. The influence of conflicts in sports doping scandals. 77. Exploring conflicts between athletes' personal beliefs and sports regulations. 78. The effects of conflicts between sports teams and sponsors. 79. The role of conflict resolution in sports coaching. 80. Analyzing conflicts in gender equality and representation in sports.

Conflict and Social Justice: 81. The causes and consequences of conflicts in the fight against racial discrimination. 82. The influence of conflicts in gender equality movements. 83. The impact of conflicts in LGBTQ+ rights advocacy. 84. Analyzing conflicts in the pursuit of disability rights. 85. The connection between conflicts in immigration policies and social justice. 86. The effects of conflicts in environmental activism. 87. Exploring conflicts in the criminal justice system and prison reform. 88. The role of conflicts in indigenous rights movements. 89. The impact of conflicts in economic inequality and wealth distribution. 90. Analyzing conflicts in the fight against human trafficking.

Conflict and Education: 91. The causes and outcomes of conflicts in school settings. 92. The influence of conflicts between teachers and students on academic performance. 93. The effects of conflicts in standardized testing and educational policies. 94. The connection between conflicts in school bullying and mental health. 95. The role of conflicts in the inclusion of students with disabilities. 96. The impact of conflicts in educational funding and resource allocation. 97. Analyzing conflicts in the implementation of multicultural education. 98. The effects of conflicts in teacher unions and labor rights. 99. The role of conflict resolution in promoting a positive school climate. 100. Exploring conflicts in educational equity and access.

Conflict and Health: 101. The causes and consequences of conflicts in healthcare systems. 102. The influence of conflicts in medical ethics and patient care. 103. The impact of conflicts in vaccination policies and public health. 104. Analyzing conflicts in access to healthcare and healthcare disparities. 105. The effects of conflicts in mental health stigma and treatment. 106. The connection between conflicts in medical research and informed consent. 107. The role of conflicts in the pharmaceutical industry and drug pricing. 108. Exploring conflicts in end-of-life care and euthanasia. 109. The effects of conflicts in reproductive rights and healthcare. 110. Analyzing conflicts in alternative medicine and traditional healthcare systems.

Conflict and Technology: 111. The causes and consequences of conflicts in online privacy. 112. The influence of conflicts in cybersecurity and data breaches. 113. The impact of conflicts in artificial intelligence and job displacement. 114. Analyzing conflicts in social media regulation and freedom of speech. 115. The effects of conflicts in digital divide and access to technology. 116. The connection between conflicts in online harassment and mental health. 117. The role of conflicts in technology addiction and screen time. 118. Exploring conflicts in the regulation of autonomous vehicles. 119. The impact of conflicts in copyright infringement and intellectual property. 120. Analyzing conflicts in technology-based surveillance and civil liberties.

Conflict and the Environment: 121. The causes and consequences of conflicts in climate change policies. 122. The influence of conflicts in natural resource extraction and conservation. 123. The impact of conflicts in environmental activism and protests. 124. Analyzing conflicts in land rights and indigenous environmentalism.

These essay topic ideas and examples cover a wide range of conflict-related themes and can serve as a starting point for your writing. Remember to choose a topic that interests you and aligns with your essay's purpose. Good luck with your essay, and may your exploration of conflict deepen your understanding of the world around you.

Want to research companies faster?

Instantly access industry insights

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Leverage powerful AI research capabilities

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2024 Pitchgrade

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Business

Essay Samples on Conflict

How to resolve conflict without violence: building peaceful communities.

Conflict is an inevitable aspect of human interactions, and while disagreements are a natural part of life, it is essential to address and resolve them without resorting to violence. By employing effective methods and strategies, individuals and communities can navigate conflicts constructively, fostering harmonious relationships...

- Conflict Resolution

The UPS Teamsters Strike: Navigating Negotiations and Economic Impact

The Looming UPS Teamsters Strike After months of negotiations, the UPS Teamsters union and UPS management reached a tentative agreement on July 26, 2023, potentially averting a nationwide strike. The Teamsters strike had been authorized for early August if a deal was not reached, which...

- Employee Engagement

The Enduring Issue of Conflict: From Imperialism to WWI and WWII

Introduction Conflict is a very significant enduring issue in history. Conflict is a serious disagreement or argument. There can be conflict between individuals, groups of people, and even nations, is significant because it affects a lot of people and has long-lasting effects. Some issues of...

- Enduring Issue

- Imperialism

Conflict Theory and Ageism in Aging Discrimination

The advantage characteristic of the conflict theory is that it creates a continuous constant, drive for the middle and upper topmost class of young people to accumulate compile, wealth to maintain preserve their social class. This is good because it ensures guarantee the economy grows....

- Discrimination

The Link Between Identity and Purpose in Life in "Never Let Me Go"

It is known to man that when one knows what when you can find your purpose find a sense of identity to yourself. In “Never Let Me Go” The story focuses on Kathy H., who portrays herself as a guardian, talking about looking after organ...

- Book Review

- Never Let Me Go

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

Ton Of Conflict In Sonny's Blues

There is a ton of conflict at work in 'Sonny's Blues.' The general clash in this story is between black presence and white society, and this has unequivocally affected how the storyteller sees the world. He depicts this battle of experiencing childhood in Harlem, where...

- Sonny's Blues

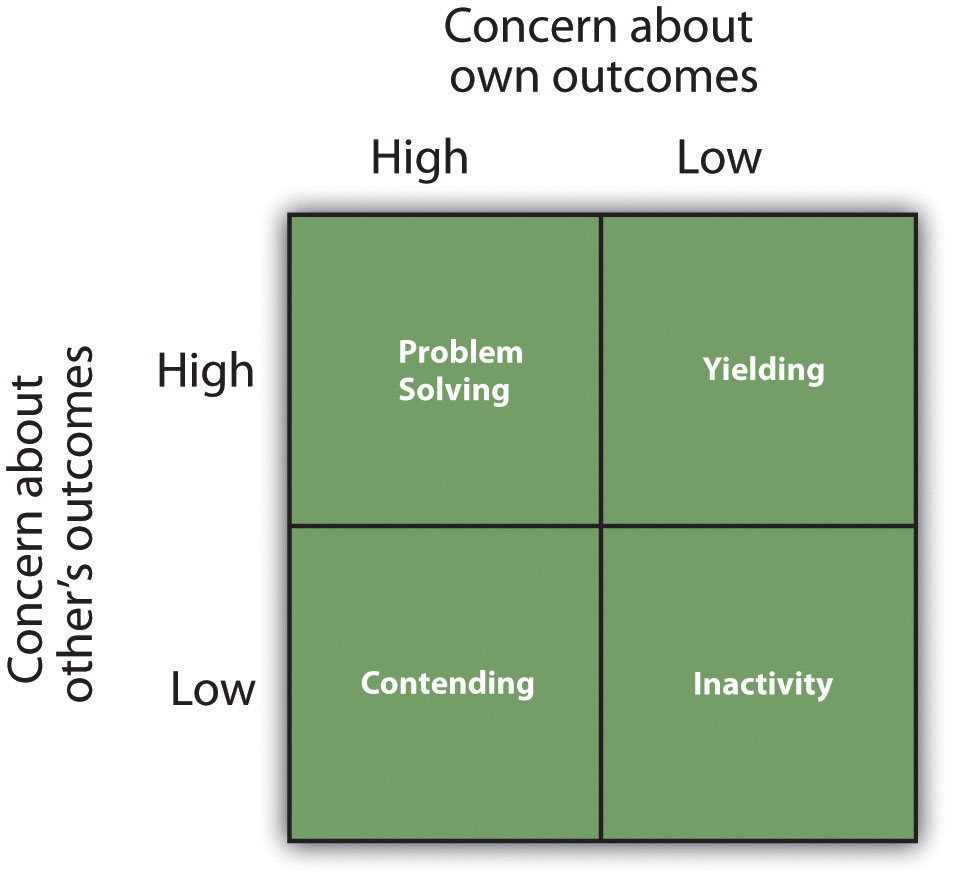

My Personal Opinion on the Types of Conflict Resolution

Normally there are four types of conflict resolution strategies: Avoiding, Competing, Accommodating, and Collaborating. Avoiding is about a withdraw of a conflict. Competing is about a team being divided into two parties and instead of being collaborative they just fight and compete about who idea...

- Collaboration

- Conflict Resolution Theory

Kokata: Traditional Conflict Resolution Mechanism of the Kambata People of SNNPRS

Governments may find it usually difficult to find solution for a conflict of any type-be within a particular group, between groups or relating to between their own and outside groups, for example border conflict. This may be as they aspire to address conflict only using...

Analysis of the Salam Model of Conflict Resolution

Man is essentially a social being who necessarily must interact and compete with other members of his social setting to achieve anything. The Holy Qur’an alludes to this innate quality of man when it states that “And everyone has a goal which dominates him; vie,...

- Competition

Theme of Conflict In 'A View From The Bridge'

Conflict is a theme which has quite a large role in this play because all the characters have a little bit of conflict between each other. In 1930s Brooklyn, there was conflict between two cultures due to Italians moving over to America. This caused conflict...

- A View From The Bridge

- Arthur Miller

Don Nardo's The Persian Gulf War and Its Detalisation of Conflicts

The Persian Gulf War By Don Nardo goes into detail about the conflict between Iran and Iraq, Kuwait, United States and more. In the introduction it starts off by stating “The world was stunned on August 2, 1990, by alarming news.[...]¨(7). The alarming news was...

- Persian Gulf

Conflict among Nations as a Global Issue Throughout History

Throughout history, enduring issues have developed across time and societies. One such issue is conflict, this is a disagreement between two opposing parties. This issue is significant as it can destroy empires, encourage innovations, and kill or displace civilians. You can see the significance of...

- Controversial Issue

An Argument for Constructing a Resolution Strategy for Ethnic Conflict

Global conflict refers to the disputes between different nations or states. It also refers to the conflicts between organizations and people in various nation-states. Furthermore, it applies to inter-group conflicts within a country in cases where one group is fighting for increased political, economic, or...

- Ethnic Identity

- Religious Pluralism

Different Conflict Situations In A Diverse Workplace

Joanne Barrett, a recruitment specialist states that when in a workplace with employees of different cultures, backgrounds, beliefs and values, conflict is bound to happen. Showing respect towards fellow colleagues in the organisation is important as to help solve it. Barret suggested that employers and...

How Conflict Can Be Normal In All Relationships

While conflict can be normal in all relationships, it should be a last resort by all means. Relationships should be a mutual effort and be based on communication. Reason being, it can lead to an unhealthy relationship, create a negative perception of the relationship, and...

- Relationship

Issue Of Conflict Mineral Mining In Congo

It is no major secret that the area of land that makes up the Democratic Republic of the Congo (referred to in this paper by its shortened name, the Congo) has been in a state of conflict for the past 40 years or more, with...

- Natural Resources

Reflection On Conflicts And Its Management In My Company

There is no universal explanation of what a conflict is, but can be considered, any situation in which the people’s perspectives, interests, goals, principles, or feelings are divergent. To ensure cooperation and productivity in any given company, every aspect of conflict must be appropriately dealt...

The War In Yemen: Roots Of The Conflict

The current war in Yemen has been ongoing for three years, since 2015. The Houthi rebels and Yemen’s government are in a bloody war. Roots for conflict started with the failure of a political change when the then president handed over his power to his...

- What Is History

Cultural Conflicts In Multinational Corporations: Michelin Company Case

Michelin was established in the 1800s in France. There are over 120,000 employee around the world and most 20,000 people are working in North America. In 2004, the department of North America faced some challenges includes decreasing in performance and lack of competitiveness. After evaluation,...

Best topics on Conflict

1. How to Resolve Conflict Without Violence: Building Peaceful Communities

2. The UPS Teamsters Strike: Navigating Negotiations and Economic Impact

3. The Enduring Issue of Conflict: From Imperialism to WWI and WWII

4. Conflict Theory and Ageism in Aging Discrimination

5. The Link Between Identity and Purpose in Life in “Never Let Me Go”

6. Ton Of Conflict In Sonny’s Blues

7. My Personal Opinion on the Types of Conflict Resolution

8. Kokata: Traditional Conflict Resolution Mechanism of the Kambata People of SNNPRS

9. Analysis of the Salam Model of Conflict Resolution

10. Theme of Conflict In ‘A View From The Bridge’

11. Don Nardo’s The Persian Gulf War and Its Detalisation of Conflicts

12. Conflict among Nations as a Global Issue Throughout History

13. An Argument for Constructing a Resolution Strategy for Ethnic Conflict

14. Different Conflict Situations In A Diverse Workplace

15. How Conflict Can Be Normal In All Relationships

- Grocery Store

- Business Success

- Advertising

- Time Management

- Business Ethics

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Submit?

- About International Studies Review

- About the International Studies Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, concepts, theory, and selection of studies, trust after conflict, cooperation after conflict, social identities after conflict, concluding discussion.

- < Previous

What Do We Know about How Armed Conflict Affects Social Cohesion? A Review of the Empirical Literature

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Charlotte Fiedler, What Do We Know about How Armed Conflict Affects Social Cohesion? A Review of the Empirical Literature, International Studies Review , Volume 25, Issue 3, September 2023, viad030, https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viad030

- Permissions Icon Permissions

How does armed conflict affect the social fabric of societies? This question is central if we want to understand better why some countries experience repeated cycles of violence. In recent years, considerable scientific work has been put into studying the social legacies of armed conflict. This article brings these academic studies together in a novel way, taking a holistic perspective and analyzing each of the three constituent elements of social cohesion—trust, cooperation, and identity—in detail and along both a vertical (state–society relations) and a horizontal (interpersonal and intergroup relations) dimension. Bringing together insights from fifty empirical studies, I call into question the initial optimism expressed by some scholars that conflict increases social cohesion. Only political participation seems to often be positively affected by experiencing conflict. In contrast, social and political trust as well as identification and cooperation across groups declines. However, research in several of these sub-elements of social cohesion is still nascent so that the strengths and shortcomings of the different studies are discussed and future avenues for research are identified.

¿En qué manera afectan los conflictos armados al tejido social de las sociedades? Esta pregunta resulta de vital importancia si queremos entender en mayor medida las razones por las cuales algunos países experimentan ciclos repetidos de violencia. Durante los últimos años, se ha destinado una cantidad considerable de trabajo científico al estudio de los legados sociales en los conflictos armados. Este artículo reúne estos estudios académicos de una manera novedosa, a través de una perspectiva holística y analizando, en detalle y a través tanto de una dimensión vertical (relaciones Estado-sociedad) como de una dimensión horizontal (relaciones interpersonales e intergrupales), cada uno de los tres elementos constitutivos de la cohesión social: confianza, cooperación e identidad. En este artículo, hemos reunido ideas procedentes de 50 estudios empíricos, lo cual nos permite cuestionar el optimismo inicial que había sido expresado por algunos académicos consistente en que el conflicto aumenta la cohesión social. Lo único que parece verse afectado, con frecuencia, de una manera positiva por el hecho de involucrarse en conflictos es la participación política. Por el contrario, tanto la confianza social y política, como la identificación y la cooperación entre grupos, disminuyen. Sin embargo, la investigación existente acerca de algunos de estos subelementos de la cohesión social es todavía incipiente, por lo que, en este artículo debatimos las fortalezas y deficiencias de los diferentes estudios e identificamos futuras vías de investigación.

Quels sont les effets d’un conflit armé sur le tissu social des sociétés ? Cette question s’avère primordiale pour mieux comprendre pourquoi il existe des cycles de violence récurrents dans certains pays. Ces dernières années, un grand nombre de travaux scientifiques ont porté sur l’étude de l’héritage social d’un conflit armé. Cet article rassemble ces études académiques de manière inédite, en adoptant une perspective holistique. Il analyse en détail chacun des trois éléments constitutifs de la cohésion sociale (la confiance, la coopération et l’identité) dans leurs dimensions verticale (relations État-société) et horizontale (relations interpersonnelles et intergroupes). En m’appuyant sur des informations issues de 50 études empiriques, je remets en question l’optimisme initial exprimé par certains chercheurs selon lequel un conflit favorise la cohésion sociale. Il semblerait que seule la participation politique se trouve souvent renforcée par les conflits. Par opposition, la confiance sociale et politique ainsi que l’identification et la coopération entre les groupes chutent. Cependant, la recherche dans plusieurs de ces sous-éléments de cohésion sociale est encore jeune. L’article s’intéresse donc aux forces et faiblesses des différentes études avant de proposer de nouvelles pistes de recherche.

How does conflict affect social cohesion, that is, the social fabric of societies? This question is central if we want to better understand why some countries experience repeated cycles of violence, while others are able to leave their violent past behind. In 2010, Blattman and Miguel (2010 , 42) noted that “the social and institutional legacies of conflict are arguably the most important but least understood of all war impacts.” Since then, considerable work has been put into studying the social legacies of armed conflict. This literature review brings these studies together in a novel way by focusing on the effects of armed conflict on social cohesion.

In a meta-analysis of sixteen studies on how conflict affects prosocial (other-oriented) behavior, 1 Bauer et al. (2016 , 25) find that “people exposed to war violence tend to behave more cooperatively after war.” Is it really the case that conflicts might incur high immediate human costs and result in both short- and long-term economic damage, but at the same time improve a country’s social fabric? To answer this question, I conduct an extensive review of the empirical academic literature on how conflict affects social cohesion by taking a holistic perspective and analyzing each of the three constituent elements of social cohesion—trust, cooperation, and identity—in detail and along both a vertical and a horizontal dimension. Overall, the study compiles insights from fifty empirical studies, most of which analyze the effects of conflict based on comprehensive survey data or behavioral experiments.

Contrary to the initial optimism expressed by some scholars, my main finding is that the literature mainly indicates that conflict harms social cohesion. First, research on political trust and social identities, albeit partially still nascent, clearly points toward conflict having net negative effects with political trust decreasing and group identities increasing. Second, there is quite a large body of literature showing that social trust is negatively affected by the experience of violence. However, in some cases, a positive effect can also be traced suggesting heterogeneous effects that yet need to be better understood. The literature on cooperation quite clearly suggests that cooperation increases after conflict. However, several (and particularly newer) studies demonstrate that an increase in cooperation can often be explained by prosocial behavior toward the in-group but not the out-group, calling into question whether this should be interpreted positively for social cohesion overall. Political participation does, however, seem to be one aspect of social cohesion where a positive effect of victimization can be traced in several contexts. Additionally, reviewing the literature on how conflict affects social cohesion reveals several crucial gaps in current approaches.

This article is organized into six sections beyond this introduction. The second section discusses the concepts of conflict, victimization and social cohesion used, presents the main theoretical arguments on how conflict could affect social cohesion as well as the selection criteria for the studies included in the review. The three following sections analyze the current empirical literature with regard to how conflict affects each of the three core elements of social cohesion: trust, cooperation and identity. The final section gathers the insights from across the three elements together to reveal patterns and remaining gaps as well as providing a concluding discussion.

Key Concepts

In this review, I study how armed conflict affects social cohesion. Regarding armed conflict , I here follow an established definition of armed conflict whereby “A state-based armed conflict is a contested incompatibility that concerns government and/or territory where the use of armed force between two parties, of which at least one is the government of a state, results in at least 25 battle-related deaths in one calendar year.” ( UCDP 2020 ). Non-state conflict, in turn, is characterized by the fact that the government is not one of the warring parties, whereas in interstate conflicts, both warring parties are governments of a state. Regarding victimization , I include both studies that understand conflict exposure narrowly and therefore focus on bodily harm (to oneself or close relatives), combat exposure, or forced relocation as well as those applying a broader conceptualization of victimization, by including, for example, property damage or witnessing violence.

Social cohesion is now a concept that attracts widespread scholarly as well as policy attention because of the key importance ascribed to it with regard to a large variety of outcomes, including development and peace. As with most complex concepts, there is no single, agreed-upon definition of social cohesion available ( Schiefer and van der Noll 2016 ). Because it follows a minimalist approach, which allows using social cohesion as an analytical concept, but at the same time, develops the well-known Chan, To, and Chan (2006 ) conceptualization further in several important regards, 2 I follow the definition by Leininger et al. (2021 , 3) wherein “Social cohesion refers to the vertical and horizontal relations among members of society and the state that hold society together. Social cohesion is characterized by a set of attitudes and behavioral manifestations that includes trust, an inclusive identity and cooperation for the common good.” Focusing on two dimensions (the vertical and the horizontal) as well as three core elements of social cohesion—trust, identity, and cooperation—is in line with the main arguments put forth in a relatively recent review article by Schiefer and van der Noll (2016 ) on the core elements common to almost all social cohesion concepts.

The studies covered in this review relate to the concept of social cohesion in different ways. While some explicitly reference social cohesion, others connect their work to social capital and still others aim to contribute to the debate on how conflict affects prosociality (social preferences, i.e., caring about others). While the three are clearly interlinked, there are partially extensive definitional debates on each of these concepts, which cannot be covered in detail here. In its most minimal conceptualization, social capital has been associated with social trust, while in a maximalist approach, it can cover several elements of social cohesion (social and political trust, civic and political participation) as well as additional features (e.g., altruism, informal social interactions, social contacts, and shared norms) ( Engbers, Thompson, and Slaper 2017 ). Common to most conceptualizations is a focus on trust, social contacts and membership in social organizations, which is why one can argue that a large part of social capital focuses on a subset of social cohesion, namely aspects of trust, and cooperation on the horizontal dimension ( Klein 2013 ). Social preferences have mostly been studied through the at times rather vague umbrella terms of prosociality or “other-regarding preferences.” Rooted in psychology and behavioral economics, the two largely overlap, as other-regarding preferences aim to study individuals’ “concerns for the well-being of others, for fairness and for reciprocity” ( Fehr and Schmidt 2006 , 617) and prosociality “why people help others at a cost to oneself” ( Bhogal and Farrelly 2019 , 910). Both include behavior that provides the basis for or is constitutive of social cohesion (altruism, fairness, cooperation, and trust). At the same time, social preferences partially go beyond what would be considered at the core of social cohesion while not dealing with other important social cohesion sub-elements—especially identity and more generally the vertical dimension connecting individuals and groups on the one hand and the state on the other hand.

Theoretical Expectations

Different theoretical arguments have been put forth to explain both why victimization through conflict might increase social cohesion and, contrarily, why and how conflict instead might have a negative impact on social cohesion. While some assume that violence changes people’s attitudes and behavior toward one another more generally others focus on how conflict affects attitudes toward and within specific groups. The theories do not differentiate between the elements of social cohesion but allow for more general assumptions about how conflict affects social cohesion.

Several authors have put forward arguments over why conflict might increase social cohesion. Blattman (2009 ) first drew upon psychology’s post-traumatic growth (PTG) theory and applied it to the post-conflict context to ascribe war a positive transformative potential. Tedeschi and Calhoun (2004 , 1) define PTG as “the experience of positive change that occurs as a result of the struggle with highly challenging life crises” and indeed psychologists have found examples of PTG across a wide array of outcomes, including several severe medical diseases, sexual assault, combat, and being a refugee. This theory has been applied by several to the post-civil war context with war and violence experienced during it representing the traumatic event ( Bellows and Miguel 2009 ; Blattman 2009 ; Voors et al. 2012 ; Freitag, Kijewski, and Oppold 2019 ). This is said to be able to lead to a positive re-evaluation of life, political behavior, and personal relationships more generally and hence positively affect social preferences and relationships. In a similar vein, others suggest victims of violence more actively seek to participate in public life to work against stigma and in order to “escape the state of helplessness and feel empowered by this action” ( Freitag, Kijewski, and Oppold 2019 , 408, Koos 2018 ). A second set of explanations for a possible positive change focus on how individuals and societies adapt to conflict. Bauer et al. (2016 ) speak of an “economic mechanism” whereby individuals decide to cooperate more in order to increase personal safety and deal with economic hardship resulting from the war (for a similar argument, see also Krakowski [2020] ). Gilligan, Pasquale, and Samii (2014 , 605) put forward a “purging mechanism” where less social persons disproportionately flee communities plagued by war and a coping mechanism “by which individuals who have few options to flee band together to cope with threats and trauma.” De Luca and Verpoorten (2015a ), in turn, suggest that war disrupts economic activity, which creates the time resources necessary to engage politically, with lasting effects also in the post-conflict period.

A negative mechanism has also been suggested, whereby violence is instead expected to lead to a persistent damage of social cohesion. A first explanation for this is again a psychological mechanism, which I label “post-traumatic withdrawal theory.” This theoretical approach is based on the internationally recognized post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), “a debilitating anxiety disorder resulting from trauma exposure” ( Frans et al. 2005 , 291). PTSD has been linked to a number of traumatic events, including war, rape, natural disasters, accidents, and crime experiences. If PTSD or other forms of “war-related distress” persist after the war, then one can expect victims to feel less close to others, as well as to withdraw from social activities, resulting in a reduction in social cohesion ( Kijewski and Freitag 2018 ). Even if not directly suffering from PTSD, war may more generally teach people to distrust others, especially so if allegiances in the war run through communities ( Cassar, Grosjean, and Whitt 2013 ; De Luca and Verpoorten 2015b ). Others have suggested that conflict should reduce cooperation and trust as violence and displacement disrupt social structures, reducing the chances to participate in community groups as well as more permanently altering the composition of communities in ways that are detrimental to cooperation ( Gilligan, Pasquale, and Samii 2014 ; De Luca and Verpoorten 2015b ). Additionally, several authors have put forward a denunciation mechanism whereby victims of violence not only distance themselves from those that perpetrated the violence but also their own community because they are seen as complicit in the violence ( Cassar, Grosjean, and Whitt 2013 ; Hager, Krakowski, and Schaub 2019 ; Krakowski 2020 ).

A third mechanism focuses on how individuals interact with one another depending on group membership, arguing that conflict will have mixed effects by increasing in-group bonding while decreasing out-group bridging. It is based on social identity theory, most prominently coined by social psychologists Tajfel and Turner (1979 , 1986 ) who contend that individuals have a strong inclination to feel part of groups, which they do on the basis of social (group) identities. Based on these identities, we then categorize people into groups and distinguish between “us” and “them.” This, in turn, implies that people favor their in-group and behave more prosocially toward its members, which can increase the distance to the out-group ( Tajfel and Turner 1979 , 1986 ). Applying this to the conflict context means that there is an extreme event that intensifies group distinctions, increasing in-group bonding and at the same time decreasing out-group bridging. This argumentation is very similar to an evolutionary mechanism put forth by some economists according to which intergroup conflict should increase internal bonding and cohesion because only groups in which individuals cooperate and behave altruistically toward one another will survive competition ( Bowles 2006 ; Choi and Bowles 2007 ). Since war is an extreme form of competition, it is assumed it will hence increase parochial prosociality—prosocial behavior toward the in-group—while at the same time increasing aversion to the out-group, particularly the opponent in the war (see, for example, Grosjean 2014 ; Bauer et al. 2016 ; Ingelaere and Verpoorten 2020 ). In conflict studies, this mechanism has especially been stressed for societies where ethnicity plays a major role and can act as a marker for the in-group and the out-group ( Horowitz 1985 ). Based on this theoretical argument, one would expect more cooperation and trust within groups and less across groups as a result of conflict. For identity, the theory would predict a strengthening of group identities rather than allowing subordinate identities to overlap or a joint identity to develop.

Overall, the different arguments lead to highly varying expectations with some arguments suggesting conflict should increase social cohesion but others the opposite. Looking at group dynamics, one could expect that war increases cohesiveness within, but not across, groups with a net negative effect on social cohesion for society as a whole. The next section presents and discusses the literature with regard to its empirical findings and theoretical implications.

Selection of Studies

I define several scope conditions for which types of studies are included in the analysis to allow a focused discussion. 3 First, to ensure a comprehensive overview of the research field, this article includes both published, peer-reviewed academic studies and high-quality working papers. 4 Second, only empirical studies are included to cover the current state of knowledge of the effects of conflict on social cohesion. Third, I include both studies that explicitly analyze and reference social cohesion as a whole as well as studies that only focus on one or several of the three core components of social cohesion—trust, cooperation, and identity. Fourth, I am mainly interested in studies on intrastate conflict, but because they also provide interesting insights and because the line between intra- and inter-state conflict is sometimes blurry, I also include a small number of studies that analyze the effects of conflict between states on social cohesion. Non-political violence more generally, however, is not included. Fifth, studies that investigate the short-, medium-, and long-term effects of conflict are considered even though the medium- and long-term effects are likely to be particularly important for post-conflict development and peace because defining a clear conflict end can be challenging at times. The studies were identified first based on searches of academic literature databases (including Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar). I conducted full-text searches and looked for key terms in titles and abstracts. 5 This was complemented by the snowballing technique starting with the influential Bauer et al. (2016 ) meta-analysis that combines sixteen studies on prosociality and conflict.

Overall, I identify fifty relevant articles. 6 Table 1 gives an overview of the key characteristics of the studies included and demonstrates that a majority of them are single-country studies published in political science or economics journals. There is a strong focus on intrastate conflict, while methodologically most papers work with surveys. Table 1 also shows that the number of articles studying social cohesion after conflict has greatly increased in recent years. 7

Overview of studies included

| Scientific discipline | Political science (23) | Economics (16) | Other (8) | Working papers (3) |

| Scope | Single-country (41) | Cross-country (9) | ||

| Methodology | Survey (36) | Behavioural experiment (9) | Both (3) | Other (2) |

| Type of conflict* | Interstate (7) | Intrastate (40) | Non-state (6) | |

| Year published | 2005–2010 (3) | 2010–2015 (12) | 2015–2020 (23) | Since 2021(9) |

| Scientific discipline | Political science (23) | Economics (16) | Other (8) | Working papers (3) |

| Scope | Single-country (41) | Cross-country (9) | ||

| Methodology | Survey (36) | Behavioural experiment (9) | Both (3) | Other (2) |

| Type of conflict* | Interstate (7) | Intrastate (40) | Non-state (6) | |

| Year published | 2005–2010 (3) | 2010–2015 (12) | 2015–2020 (23) | Since 2021(9) |

Notes: **Three papers include different types of conflicts and are, therefore, counted several times.

Source: Author.

The next section presents and discusses these studies with regard to their empirical evidence on how conflict affects social cohesion, more specifically trust, cooperation, and identity.

How does conflict affect the first core component of social cohesion, namely trust? This question is relevant both regarding trust between groups (social trust) as well as between the state and its citizens (political trust). Because these two types of trust have mostly been addressed by different studies, I summarize and discuss insights on each type of trust individually.

Social Trust

Overall, social trust has been studied quite extensively in the literature. The majority of studies suggest that conflict negatively impacts social trust. This holds both for studies analyzing generalized trust, that is, trust in strangers, and out-group trust, lending support to post-traumatic withdrawal and in-group/out-group mechanisms. However, a number of studies find either the opposite or that there is no statistically significant effect, suggesting heterogeneous effects that warrant further analyses.

A relatively large number of studies finds that conflict negatively impacts social trust. Cassar, Grosjean, and Whitt (2013 ) analyze the effects of the legacy of the Tajik Civil War on particularized trust using the central experimental approach for measuring trust, the so-called “trust game.” 8 Based on 426 respondents, the authors find that victims of the civil war are significantly less trusting, but only toward their local neighbors, not distant villagers. Cassar et al. (2013 ) explain this somewhat surprising result with the fact that in the Tajik Civil War, political allegiances oftentimes cut across villages. Rohner, Thoenig, and Zilibotti (2013 ) study the effects of violence on generalized trust in Uganda. Comparing Afrobarometer data before and after a peak of violence between 2002 and 2005, their results show that generalized trust decreases significantly in areas that witnessed more intense fighting and that especially out-group trust suffers as a result of conflict. Also focusing on Uganda, De Luca and Verpoorten (2015b ) are able to compare Afrobarometer survey results before, during, and after the civil war (2000, 2005, and 2012). Their findings suggest that levels of generalized trust strongly decreased during conflict and particularly so in areas heavily affected by violence. After the civil war, however, trust increased and fully recovered to pre-violence levels. Finding an effect more than 10 years after the conflict ended, Kijewski and Freitag (2018 ) use a version of “the wallet question 9 ” when analyzing survey data from 930 respondents in Kosovo and find that conflict exposure significantly decreases social trust. Conzo and Salustri (2019 ) study the effects of World War II on generalized trust in thirteen European countries. The authors find a significant decrease in trust among adults who were exposed to violence in their childhood. Applying an even longer-term perspective, Besley and Reynal-Querol (2014 ) combine historical conflict data with the Afrobarometer survey of 2008, and show that respondents from countries that experienced historical conflict between 1400 and 1700 show significantly lower out-group trust—up to 600 years later. Focusing on a particularly severe conflict, Ingelaere and Verpoorten (2020 ) find clear and persistent negative effects of the Rwandan genocide on social trust. Based on 400 collected life stories, they find that both for the Hutu and the Tutsi, inter-group trust significantly decreased as a result of the violence. The decrease is more pronounced for the Tutsi and is especially strong among those who were directly exposed to violence. In-group trust, in turn, stayed relatively stable among the Tutsi but declined among the Hutu, which can be explained by the violence targeted at the moderate Hutu. Also suggesting that several types of social trust suffer as a result of armed conflict, Lewis and Topal (2023 ) find that proximate conflict exposure is negatively correlated with generalized, out-group and in-group trust, based on combining data from Afrobarometer and the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) for fourteen African countries.

Interesting insights on possible conditional effects of conflict on social trust stem from two studies on non-state conflict. Werner and Graf Lambsdorff (2019 ) conduct several experiments on prosocial behavior with 724 students in the Maluku region of Indonesia, which experienced repeated non-state conflict between 1999 and 2011. Their experiments show that only once identity is revealed, less is allocated to members of both the in-group and the out-group and that this effect is stronger for those who report victimization. Becchetti, Conzo, and Romeo (2013 ) exposed 404 Kenyan slum inhabitants to experimental games and find that only if people are confronted with the other ethnic group or opportunistic behavior in a game played in-between two others, is there a significant reduction in their trust level in the second trust game.

Six studies instead find a significant, positive relationship between conflict exposure and trust levels. Bellows and Miguel (2009 ) study the aftermath of the civil war in Sierra Leone based on two waves of household surveys in 2005 and 2007. They find no effect with regard to trust in people from one’s own community and a positive effect on trust toward people from outside the community. Bauer, Fiala, and Levely (2017 ) study 668 former child soldiers in Uganda using a variant of the trust game and a survey. They find that those who were abducted at an early age (<14 years) display considerably more trusting behavior toward people from a “nearby but different village.” Focusing on social cohesion within communities, Gilligan, Pasquale, and Samii (2014 ) study the effects of the Nepalese Civil War. Based on experimental games, including the trust game with 252 household heads, they find that “members of communities that suffered greater exposure to fatal violence during Nepal’s 10-year civil war are significantly more prosocial in their relations with each other than were those that experienced lower levels of violence” ( Gilligan et al. 2014 , 605). Two more recent studies also find positive effects. Studying 450 Burundian refugees, Haer, Scharpf, and Hecker (2021 ) find an overall positive effect of armed conflict on generalized trust, but also that respondents with mental health problems had lower social trust. Hall and Werner (2022 ) similarly find a positive relationship between victimization and generalized trust, based on data collected among 832 refugees from Syria and Iraq in Turkey in 2016. Finally, seven studies fail to find significant effects between conflict and social trust. The studies include surveys studying inter-state as well as intra-state conflict in Africa, Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia ( Bellows and Miguel 2006 ; Grosjean 2014 ; Voors and Bulte 2014 ; Child and Nikolova 2018 ; Ferguson and Leroch 2022 ; Koos and Traunmüller 2022 ) as well as the meta-analysis by Bauer et al. (2016 ).

Recent studies that do not directly measure social trust but related outcomes come to somewhat contradictory results. Both Wayne and Zhukov’s (2022 ) study on the legacy of the holocaust as well as work by Hartman and Morse (2020 ) and Hartman, Morse, and Weber (2021 ) in Liberia and Syria find that victimization increases empathy toward vulnerable out-groups, namely refugees. Similarly, Rapp, Kijewski, and Freitag (2019 ) find that in Sri Lanka victimization increased political tolerance, even toward the outgroup and trace the effect to PTG. However, Canetti-Nisim et al. (2009 ), Beber, Roessler, and Scacco (2014 ), and Kibris and Cesur (2022 ) all find that experiencing violence increased negative attitudes toward the outgroup or minorities more generally in their studies on Sudan, Israel, and Turkey.

While a majority of the studies suggest a negative relationship between experiencing conflict and social trust there are also some indications for heterogeneous effects that warrant further scrutiny. In order to do so, the literature needs to more systematically distinguish between the different types of social trust analyzed and the corresponding type of underlying conflict. The majority of studies focus only on generalized trust, two studies exclusively analyze particularized trust, and only four compare effects across the two types. The fact that the differences regarding the underlying conflict are not taken into account properly in many of the studies can at least partially explain some seemingly contradictory findings and theoretical arguments. For example, Cassar et al. (2013 ) find that particularized trust decreases, which they explain by the fact that loyalties in the Tajik Civil War cut across villages, whereas Gilligan et al. (2014 ) find the opposite effect regarding community cohesion in Nepal where violence was primarily externally-led. In contrast, the studies that explicitly differentiate between the relevant in-group and out-group tend to find clear negative effects. While the relevance of such an explicit distinction is clearer in conflicts with a strong ethnic or religious dimension, a definitional differentiation between what constitutes the in- and out-group in the conflict at hand would greatly help contrast findings and, hence, sharpen insights on the effects of conflict on social trust more generally. It is also interesting to note that especially some newer literature suggests a positive effect of conflict exposure on generalized trust. However, these findings come exclusively from studies among refugee populations, raising the question what role the type of victimization may play to explain the effects found. Table 2 summarizes the studies on social trust after armed conflict.

Overview of studies on social trust after conflict

| n. . | Authors . | Country, conflict, conflict end . | Sample . | Victimization . | Method & identification strategy . | Aspect of social trust . | Data collection . | Effect . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ) | Uganda: civil war (2008) | Adults and ex-child soldiers ( = 668), original data, Gulu & Kitgum | Self-reported | Survey and experiments | Unclear (trust in people from a “different but nearby village”) | 2011 | Positive effect |

| 2 | ) | Kenya: non-state conflict (2008) | Slum-dwellers ( = 404), original data, Kibera | Self-reported | Experiments | Generalized | 2010 | Negative effect, conditional on ethnic cues |

| 3 | ) | Sierra Leone: civil war (2002) | Households ( = 10,471, nat. rep.), Institutional Reform and Capacity Building Project | Self-reported ( Objective | Survey (qualitative account, FE, analysis of subsamples) | Particularized and generalized | 2005, 2007 | Positive effect (generalized) |

| 4 | ) | Sierra Leone: civil war (2002) | Chiefdoms ( = 152), Institutional Reform and Capacity Building Project | Self-reported | Survey | Generalized | 2004, 2005 | No effect |

| 5 | ) | Eighteen African countries: ninety one pre-colonial conflicts (1400–1700) | Adults ( = 25,397, nat.rep.), Afrobarometer | Objective | Survey | Out-group | 2008 | Negative effect |

| 6 | ) | Tajikistan: civil war (1997) | Adults ( = 426), original data, seventeen villages in four regions | Self-reported | Experiments | Particularized and generalized | 2010 | Negative effect (particularized) |

| 7 | ) | Fifteen Central and Eastern European countries: World War II (1945) | Adults ( = 17,492), Life in Transition Survey II | Self-reported Objective | Survey | Generalized | 2010 | No effect |

| 8 | ) | Thirteen European countries: World War II (1945) | Adults born 1939–1945 ( = 6,759), Survey on Health, Ageing and Retirement | Objective | Survey | Generalized | 2006/ 2007, 2013 | Negative effect |

| 9 | ) | Uganda: civil war (2008) | Adults ( = 2,400, nat. rep.), Afrobarometer | Objective | Survey | Generalized | 2000, 2005, 2012 | Negative effect |

| 10 | ) | Kenya: electoral violence (2007/2008) | Adult men (N = 654), original data, Nairobi & Kisumu | Self-reported | Experiments | Unclear | 2015 | No effect |

| 11 | ) | Nepal: civil war (2006) | Household heads ( = 252), original data forty-eight villages in seventeen districts, | Objective | Survey and experiments (qualitative account, matching) | Particularized | 2009 | Positive effect |

| 12 | ) | Thirty-five countries in Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia: World War II, several civil wars, one non-state conflict | Adults ( = 38,864, nat. rep.), Life in Transition Survey | Self-reported | Survey, (FE, analysis of victimization) | Generalized | 2010 | No effect |

| 13 | ) | Burundi: civil war (2005) & 2012 crises | Adult refugees ( = 460) original data, three Tanzanian refugee camps | Self-reported | Survey | Generalized | 2018 | Positive effect (except for respondents with mental health problems) |

| 14 | ) | Syria & Iraq (ongoing) | Refugees residing in Turkey ( = 832), original data, Konya | Self-reported | Survey, (qualitative account, analysis of subsamples) | Generalized | 2016 | Positive effect |

| 15 | ) | Rwanda: civil war, genocide (1994) | Adults >30 years ( = 471), original data, seven communities in four provinces | Objective | Self-reported life stories | Out-group and in-group | 2007, 2011, 2015 | Negative effect (out-group and in-group) |

| 16 | ) | Kosovo: civil war (1999) | Adults ( = 930), Life in Transition Survey II, twenty-six municipalities | Self-reported ( Objective | Survey | Unclear (Loosing wallet in neighborhood) | 2010 | Negative effect |

| 17 | ) (Working Paper) | Turkey: PKK conflict (ongoing) | Male adults who served in the military ( = 5,024), original data, West Turkey | Self-reported Objective | Survey, natural experiment | Generalized | 2019 | Negative effect (direct violence experience) + positive effect (indirect conflict exposure) |

| 18 | ) | Fourteen African countries | Adults ( = 13,243, nat. rep.) Afrobarometer | Objective | Survey | Generalized, outgroup, in-group | 2005 | Negative effect |

| 19 | ) | Uganda: civil war (2008) | Adults ( = 2,431, nat. rep.) Afrobarometer | Objective | Survey | Particularized and generalized | 2008 | Negative effect (generalized) |

| 20 | ) | Burundi: civil war (2008) | Households ( = 872), original data, one hundred communities in thirteen provinces | Self-reported | Survey (IV approach) | Particularized | 2007 | No effect |

| 21 | ) | Indonesia: non-state conflict in Maluku (2011) | Undergraduate students ( = 724), original data, Maluku province | Self-reported | Experiments | Out-group and in-group | 2013 | Negative effect (out-group and in-group), conditional on ethnic cues |

| n. . | Authors . | Country, conflict, conflict end . | Sample . | Victimization . | Method & identification strategy . | Aspect of social trust . | Data collection . | Effect . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ) | Uganda: civil war (2008) | Adults and ex-child soldiers ( = 668), original data, Gulu & Kitgum | Self-reported | Survey and experiments | Unclear (trust in people from a “different but nearby village”) | 2011 | Positive effect |

| 2 | ) | Kenya: non-state conflict (2008) | Slum-dwellers ( = 404), original data, Kibera | Self-reported | Experiments | Generalized | 2010 | Negative effect, conditional on ethnic cues |

| 3 | ) | Sierra Leone: civil war (2002) | Households ( = 10,471, nat. rep.), Institutional Reform and Capacity Building Project | Self-reported ( Objective | Survey (qualitative account, FE, analysis of subsamples) | Particularized and generalized | 2005, 2007 | Positive effect (generalized) |

| 4 | ) | Sierra Leone: civil war (2002) | Chiefdoms ( = 152), Institutional Reform and Capacity Building Project | Self-reported | Survey | Generalized | 2004, 2005 | No effect |

| 5 | ) | Eighteen African countries: ninety one pre-colonial conflicts (1400–1700) | Adults ( = 25,397, nat.rep.), Afrobarometer | Objective | Survey | Out-group | 2008 | Negative effect |

| 6 | ) | Tajikistan: civil war (1997) | Adults ( = 426), original data, seventeen villages in four regions | Self-reported | Experiments | Particularized and generalized | 2010 | Negative effect (particularized) |

| 7 | ) | Fifteen Central and Eastern European countries: World War II (1945) | Adults ( = 17,492), Life in Transition Survey II | Self-reported Objective | Survey | Generalized | 2010 | No effect |

| 8 | ) | Thirteen European countries: World War II (1945) | Adults born 1939–1945 ( = 6,759), Survey on Health, Ageing and Retirement | Objective | Survey | Generalized | 2006/ 2007, 2013 | Negative effect |

| 9 | ) | Uganda: civil war (2008) | Adults ( = 2,400, nat. rep.), Afrobarometer | Objective | Survey | Generalized | 2000, 2005, 2012 | Negative effect |

| 10 | ) | Kenya: electoral violence (2007/2008) | Adult men (N = 654), original data, Nairobi & Kisumu | Self-reported | Experiments | Unclear | 2015 | No effect |

| 11 | ) | Nepal: civil war (2006) | Household heads ( = 252), original data forty-eight villages in seventeen districts, | Objective | Survey and experiments (qualitative account, matching) | Particularized | 2009 | Positive effect |

| 12 | ) | Thirty-five countries in Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia: World War II, several civil wars, one non-state conflict | Adults ( = 38,864, nat. rep.), Life in Transition Survey | Self-reported | Survey, (FE, analysis of victimization) | Generalized | 2010 | No effect |

| 13 | ) | Burundi: civil war (2005) & 2012 crises | Adult refugees ( = 460) original data, three Tanzanian refugee camps | Self-reported | Survey | Generalized | 2018 | Positive effect (except for respondents with mental health problems) |

| 14 | ) | Syria & Iraq (ongoing) | Refugees residing in Turkey ( = 832), original data, Konya | Self-reported | Survey, (qualitative account, analysis of subsamples) | Generalized | 2016 | Positive effect |

| 15 | ) | Rwanda: civil war, genocide (1994) | Adults >30 years ( = 471), original data, seven communities in four provinces | Objective | Self-reported life stories | Out-group and in-group | 2007, 2011, 2015 | Negative effect (out-group and in-group) |

| 16 | ) | Kosovo: civil war (1999) | Adults ( = 930), Life in Transition Survey II, twenty-six municipalities | Self-reported ( Objective | Survey | Unclear (Loosing wallet in neighborhood) | 2010 | Negative effect |

| 17 | ) (Working Paper) | Turkey: PKK conflict (ongoing) | Male adults who served in the military ( = 5,024), original data, West Turkey | Self-reported Objective | Survey, natural experiment | Generalized | 2019 | Negative effect (direct violence experience) + positive effect (indirect conflict exposure) |

| 18 | ) | Fourteen African countries | Adults ( = 13,243, nat. rep.) Afrobarometer | Objective | Survey | Generalized, outgroup, in-group | 2005 | Negative effect |

| 19 | ) | Uganda: civil war (2008) | Adults ( = 2,431, nat. rep.) Afrobarometer | Objective | Survey | Particularized and generalized | 2008 | Negative effect (generalized) |

| 20 | ) | Burundi: civil war (2008) | Households ( = 872), original data, one hundred communities in thirteen provinces | Self-reported | Survey (IV approach) | Particularized | 2007 | No effect |

| 21 | ) | Indonesia: non-state conflict in Maluku (2011) | Undergraduate students ( = 724), original data, Maluku province | Self-reported | Experiments | Out-group and in-group | 2013 | Negative effect (out-group and in-group), conditional on ethnic cues |

a A core challenge when analyzing how conflict exposure affects social and political attitudes is causal identification, particularly the question whether individuals with certain characteristics are more likely to be targeted by violence in the first place. If not through (survey) experiments, in statistical analyses of survey data authors can try to alleviate (if not eliminate) this concern through an identification strategy. These often include providing a qualitative account of why violence was random, analyzing factors connected to victimization, employing fixed effects, analyzing subsamples that are particularly unlikely to have been strategically targeted, including pre-exposure controls, employing an instrumental variable approach or making use of matching techniques.

Political Trust

Political trust regards the trust citizens place in current incumbents—which I label personalized political trust—as well as institutional trust, which describes trust in the “formal, legal organizations of government and state, as distinct from the current incumbents nested within those organizations” ( Mattes and Moreno 2018 , 357). 10 With only eleven studies on the topic, the research field on political trust after the conflict is still relatively nascent and, hence, not yet well developed. The majority of studies looking at the relationship between conflict and political trust suggest that conflict reduces political trust. However, a few studies find positive or no effects.

Six studies find that conflict negatively affects political trust. De Juan and Pierskalla (2016 ) analyze the effect of exposure to violence based on survey data collected from 8,822 households in Nepal. They show that respondents in areas that experienced more violence were significantly less trusting regarding the national government. This negative relationship is confirmed by Hutchison and Johnson (2011 ). The authors analyze Afrobarometer survey data for sixteen African countries between 2000 and 2005 and find that respondents from countries that recently experienced internal violence are significantly less trusting in state institutions. Grosjean (2014 ), in turn, covers thirty-five countries in Europe, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. Measuring trust as the sum of trust in the presidency, the government and the parliament, and looking at within-country variation only, she finds that “political trust is strongly and negatively associated with victimization in conflict” ( Grosjean 2014 , 443). Focusing on inter-state war, Hong and Kang (2017 ) find persistent effects of violence against civilians during the Korean War (1950–1953). Sixty years later they find clear effects, with those who experienced the war displaying significantly lower trust in political institutions, particularly those institutions that were directly involved in violence. Gates and Justesen (2020 ), in turn, reveal interesting immediate short-term effects in a quasi-experimental setting in Mali. Comparing survey rounds of the Afrobarometer executed days before and after a rebel attack in 2008, they find a clear short-term effect of the attack showing that mainly the president is held responsible, albeit not state institutions more broadly. Finally, controlling for victimization in their study on peace agreements in Guatemala, Nepal and Northern Ireland, Dyrstad, Bakke, and Binningsbø (2021 ) find that victims of government-perpetrated violence are significantly less trusting of government institutions.

In a similar vein, studies looking at related outcomes find negative effects of armed conflict on relations between society and the state. Based on data from Guatemala, Nepal, and Northern Ireland, Dyrstad and Hillesund (2020 ) find that victims are more likely to support political violence. Similarly, data from 7,500 individuals across the Sahel region collected by Finkel et al. (2021 ) suggests that respondents from areas that experienced more communal violence are significantly more likely to support violent religious extremism.

There are also studies questioning a clear-cut negative relationship between conflict and political trust. Bakke et al. (2014 ) analyze political trust as one dimension of regime legitimacy in Abkhasia, a break-away region of Georgia. They find that respondents who had experienced violence had significantly higher trust levels in the president but find no effect with regard to trust in the parliament. Focusing on the police as a central state institution, Blair and Morse’s (2021 ) findings reveal the importance of differentiating who perpetrated the violence with victims of rebel-perpetrated violence being statistically significantly more trusting of the police. Focusing on sexual violence, Koos and Traunmüller (2022 ) find heterogeneous effects across three cases, suggesting that different conflict dynamics might be important to better understand the relationship between victimization and political trust. Finally, two studies suggest that the type of victimization may matter. Child and Nikolova (2018 ), focus on the long-term effects of World War II. Using a subjective measure of victimization, they find a significant, negative relationship between victimization and political trust. However, the sign is reversed and the coefficient is no longer significant when substituting the subjective survey measure with an objective measure of whether violence took place where the respondent lives, raising the question whether self-reported victimization is biasing results. Kibris and Gerling (2021 ) similarly find heterogeneous effects among 5,024 military conscripts in Turkey with increased trust levels among respondents exposed to a more intense conflict environment, but those with direct experience of violence displaying significantly lower political trust.

Overall the still relatively nascent literature on political trust after conflict so far rather suggests that victimization reduces political trust, which can be explained by two main theoretical arguments. First, several authors put forward a performance-based approach ( Hutchison and Johnson 2011 ; De Juan and Pierskalla 2016 ; Gates and Justesen 2020 ). Violence demonstrates that the state is not able to protect its citizens whereby it is a “blatant sign of the government’s inability to maintain its monopoly over the use of force” ( De Juan and Pierskalla 2016 , 68). This should reduce trust toward state institutions and particularly in areas where the population witnesses more violence. Second, trauma and distrust can result directly from the government being a main perpetrator of violence with both short- and long-term effects on trust particularly in those institutions that are viewed as most responsible for violence ( De Juan and Pierskalla 2016 ; Hong and Kang 2017 ; Dyrstad, Bakke, and Binningsbø 2021 ).

Overall, relatively few studies have systematically analyzed the effect of conflict on political trust compared with the breadth of literature on the other elements of social cohesion. While a majority of studies so far point to a negative relationship, some central questions regarding the relationship remain unanswered. This is due to a number of important differences between the studies that make it difficult to generalize findings.

First, the studies vary widely with regard to the underlying conflict being analyzed. Especially the newer studies among these suggest that both who perpetrated violence and whether individuals were directly or indirectly exposed to violence are important to understand how political trust is affected by armed conflict, but these dynamics are rarely theoretically spelled out and empirically fully investigated.

Second, the findings are difficult to compare because the studies vary greatly with regard to when trust is measured. Studies to date, analyze institutional trust at points in time that differ widely from one another, spanning from only several days after an attack to over 50 years after a conflict. More systematic longitudinal analyses on how political trust is affected by civil war are needed.

The third important difference is that the studies vary in how they measure political trust. Institutional trust is usually captured by creating an additive index measuring trust across several institutions. How sensitive the results are to the specific institutions included and whether these studies all measure the same institutional trust is unclear, because the included institutions vary widely. Furthermore, the difference between institutional and personalized political trust has not been explored systematically, leaving ample room for further research. Table 3 provides an overview over the studies on political trust after armed conflict.