Loneliness Essay Example

Loneliness is a feeling that many people experience at one point or another. The impact of it on your life can vary greatly depending on the situation. This sample will explore the different types of loneliness, how to deal with them, and some tips for overcoming loneliness in general.

Essay Example On Loneliness

- Thesis Statement – Loneliness Essay

- Introduction – Loneliness Essay

- Main Body – Loneliness Essay

- Conclusion – Loneliness Essay

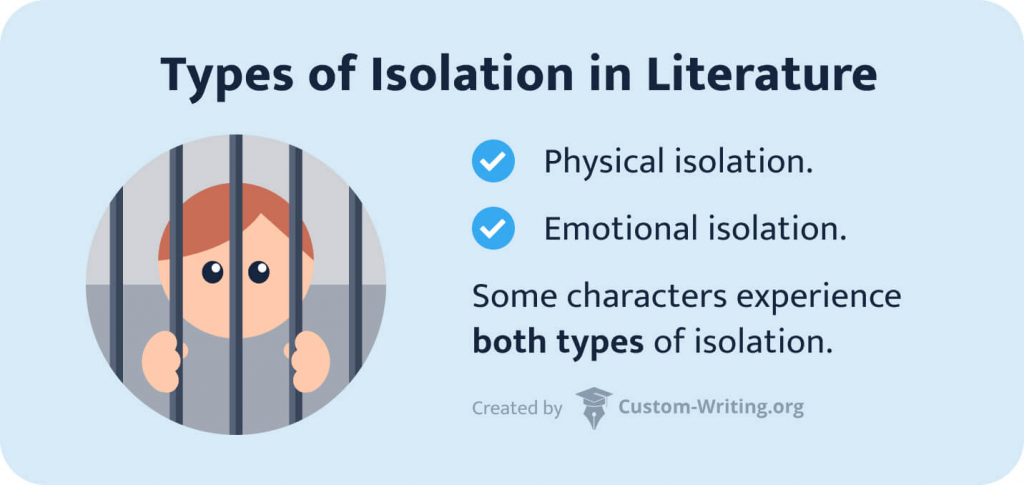

Thesis Statement – Loneliness Essay Loneliness is a consequence of being robbed of one’s freedom. It can be due to imprisonment, loss of liberty, or being discriminated against. Introduction – Loneliness Essay Loneliness is a social phenomenon that has been the subject of much research since time immemorial. Yet there still does not exist any solid explanation as to why some people are more prone to loneliness than others. This paper will seek to analyze this potentially debilitating condition from different perspectives. It will cover the relationship between loneliness and incarceration or loss of liberty; then it will proceed into discussing how emotions play a role in making us feel lonely; finally, it will look at how these feelings can affect our mental stability and overall well-being. Get Non-Plagiarized Custom Essay on Loneliness in USA Order Now Main Body – Loneliness Essay Loneliness is a universal feeling which has the ability to create its own culture within different societies. In detention facilities, there is a unique kind of loneliness that prevails between prisoners who are often divided into various categories and population groups. This has been described by Mandela as a consequence of being robbed of one’s freedom. The fact that it can be due to imprisonment, loss of liberty, or being discriminated against makes it even clearer why this isolation from other people occurs so frequently among detainees. In addition, when one spends time incarcerated in solitary confinement, they may become more experienced at coping with feelings of loneliness and despondency; however, these feelings do not tend to dissipate completely because living in an artificial environment cannot be compared with living out in the open. There is also a difference between feeling lonely and actually being alone; many individuals who do not feel social pressure, meaning that they are more than happy spending time on their own without any external stimulation, may still find themselves surrounded by people every day. Yet even this does not guarantee that one will escape feelings of isolation or rejection. Loneliness becomes an issue when it is chronic and experienced frequently, if only fleetingly. It can affect our psychological balance as well as our physical health because it usually initiates stress responses within the body which cause high blood pressure and prompt addiction to drugs or alcohol consumption. All these reasons may lead to decreased productivity and ultimately affect one’s ability to develop or maintain social connections. Buy Customized Essay on Loneliness At Cheapest Price Order Now Conclusion – Loneliness Essay Loneliness is a condition that we can’t always avoid, but it is something we should be aware of and try to limit. Thus, while the effects of loneliness on the individual may not be able to stimulate any significant changes in society, at least there will always remain one person more who understands what you are going through. Ultimately, it all comes down to empathy and sharing our own stories so that more people learn how to cope with this potentially dangerous emotional response. Hire USA Experts for Loneliness Essay Order Now

Need expert writers to help you with your essay writing? Get in touch!

This essay sample has given you some insights into the psychology of loneliness as well as suggestions for how to combat it in your own life.

Many of us find it hard to start writing an essay on general topics like loneliness. The free essay sample on loneliness is given here by the experts of Students Assignment Help to those who are assigned an essay on loneliness by professors. With the help of this sample, many ideas can easily be gathered by the college graduates to write their coursework essays.

Best essay helpers are giving to College students throughout the world through this sample. All types of essays like Argumentative Essays and persuasive essays can be written by following this example can be finished on time by the masters. If you still find it difficult to write a supreme quality essay on any topic then ask for the essay writing services from Students Assignment Help anytime.

Explore More Relevant Posts

- Nike Advertisement Analysis Essay Sample

- Mechanical Engineer Essay Example

- Reflective Essay on Teamwork

- Career Goals Essay Example

- Importance of Family Essay Example

- Causes of Teenage Depression Essay Sample

- Red Box Competitors Essay Sample

- Deontology Essay Example

- Biomedical Model of Health Essay Sample-Strengths and Weaknesses

- Effects Of Discrimination Essay Sample

- Meaning of Freedom Essay Example

- Women’s Rights Essay Sample

- Employment & Labor Law USA Essay Example

- Sonny’s Blues Essay Sample

- COVID 19 (Corona Virus) Essay Sample

- Why Do You Want To Be A Nurse Essay Example

- Family Planning Essay Sample

- Internet Boon or Bane Essay Example

- Does Access to Condoms Prevent Teen Pregnancy Essay Sample

- Child Abuse Essay Example

- Disadvantage of Corporate Social Responsibilities (CSR) Essay Sample

- Essay Sample On Zika Virus

- Wonder Woman Essay Sample

- Teenage Suicide Essay Sample

- Primary Socialization Essay Sample In USA

- Role Of Physics In Daily Life Essay Sample

- Are Law Enforcement Cameras An Invasion of Privacy Essay Sample

- Why Guns Should Not Be Banned

- Neolithic Revolution Essay Sample

- Home Schooling Essay Sample

- Cosmetology Essay Sample

- Sale Promotion Techniques Sample Essay

- How Democratic Was Andrew Jackson Essay Sample

- Baby Boomers Essay Sample

- Veterans Day Essay Sample

- Why Did Japan Attack Pearl Harbor Essay Sample

- Component Of Criminal Justice System In USA Essay Sample

- Self Introduction Essay Example

- Divorce Argumentative Essay Sample

- Bullying Essay Sample

Get Free Assignment Quote

Enter Discount Code If You Have, Else Leave Blank

Paris, 1951. Photo by Elliot Erwitt/Magnum

Loved, yet lonely

You might have the unconditional love of family and friends and yet feel deep loneliness. can philosophy explain why.

by Kaitlyn Creasy + BIO

Although one of the loneliest moments of my life happened more than 15 years ago, I still remember its uniquely painful sting. I had just arrived back home from a study abroad semester in Italy. During my stay in Florence, my Italian had advanced to the point where I was dreaming in the language. I had also developed intellectual interests in Italian futurism, Dada, and Russian absurdism – interests not entirely deriving from a crush on the professor who taught a course on those topics – as well as the love sonnets of Dante and Petrarch (conceivably also related to that crush). I left my semester abroad feeling as many students likely do: transformed not only intellectually but emotionally. My picture of the world was complicated, my very experience of that world richer, more nuanced.

After that semester, I returned home to a small working-class town in New Jersey. Home proper was my boyfriend’s parents’ home, which was in the process of foreclosure but not yet taken by the bank. Both parents had left to live elsewhere, and they graciously allowed me to stay there with my boyfriend, his sister and her boyfriend during college breaks. While on break from school, I spent most of my time with these de facto roommates and a handful of my dearest childhood friends.

When I returned from Italy, there was so much I wanted to share with them. I wanted to talk to my boyfriend about how aesthetically interesting but intellectually dull I found Italian futurism; I wanted to communicate to my closest friends how deeply those Italian love sonnets moved me, how Bob Dylan so wonderfully captured their power. (‘And every one of them words rang true/and glowed like burning coal/Pouring off of every page/like it was written in my soul …’) In addition to a strongly felt need to share specific parts of my intellectual and emotional lives that had become so central to my self-understanding, I also experienced a dramatically increased need to engage intellectually, as well as an acute need for my emotional life in all its depth and richness – for my whole being, this new being – to be appreciated. When I returned home, I felt not only unable to engage with others in ways that met my newly developed needs, but also unrecognised for who I had become since I left. And I felt deeply, painfully lonely.

This experience is not uncommon for study-abroad students. Even when one has a caring and supportive network of relationships, one will often experience ‘reverse culture shock’ – what the psychologist Kevin Gaw describes as a ‘process of readjusting, reacculturating, and reassimilating into one’s own home culture after living in a different culture for a significant period of time’ – and feelings of loneliness are characteristic for individuals in the throes of this process.

But there are many other familiar life experiences that provoke feelings of loneliness, even if the individuals undergoing those experiences have loving friends and family: the student who comes home to his family and friends after a transformative first year at college; the adolescent who returns home to her loving but repressed parents after a sexual awakening at summer camp; the first-generation woman of colour in graduate school who feels cared for but also perpetually ‘ in-between ’ worlds, misunderstood and not fully seen either by her department members or her family and friends back home; the travel nurse who returns home to her partner and friends after an especially meaningful (or perhaps especially psychologically taxing) work assignment; the man who goes through a difficult breakup with a long-term, live-in partner; the woman who is the first in her group of friends to become a parent; the list goes on.

Nor does it take a transformative life event to provoke feelings of loneliness. As time passes, it often happens that friends and family who used to understand us quite well eventually fail to understand us as they once did, failing to really see us as they used to before. This, too, will tend to lead to feelings of loneliness – though the loneliness may creep in more gradually, more surreptitiously. Loneliness, it seems, is an existential hazard, something to which human beings are always vulnerable – and not just when they are alone.

In his recent book Life Is Hard (2022), the philosopher Kieran Setiya characterises loneliness as the ‘pain of social disconnection’. There, he argues for the importance of attending to the nature of loneliness – both why it hurts and what ‘that pain tell[s] us about how to live’ – especially given the contemporary prevalence of loneliness. He rightly notes that loneliness is not just a matter of being isolated from others entirely, since one can be lonely even in a room full of people. Additionally, he notes that, since the negative psychological and physiological effects of loneliness ‘seem to depend on the subjective experience of being lonely’, effectively combatting loneliness requires us to identify the origin of this subjective experience.

S etiya’s proposal is that we are ‘social animals with social needs’ that crucially include needs to be loved and to have our basic worth recognised. When we fail to have these basic needs met, as we do when we are apart from our friends, we suffer loneliness. Without the presence of friends to assure us that we matter, we experience the painful ‘sensation of hollowness, of a hole in oneself that used to be filled and now is not’. This is loneliness in its most elemental form. (Setiya uses the term ‘friends’ broadly, to include close family and romantic partners, and I follow his usage here.)

Imagine a woman who lands a job requiring a long-distance move to an area where she knows no one. Even if there are plenty of new neighbours and colleagues to greet her upon her arrival, Setiya’s claim is that she will tend to experience feelings of loneliness, since she does not yet have close, loving relationships with these people. In other words, she will tend to experience feelings of loneliness because she does not yet have friends whose love of her reflects back to her the basic value as a person that she has, friends who let her see that she matters. Only when she makes genuine friendships will she feel her unconditional value is acknowledged; only then will her basic social needs to be loved and recognised be met. Once she feels she truly matters to someone, in Setiya’s view, her loneliness will abate.

Setiya is not alone in connecting feelings of loneliness to a lack of basic recognition. In The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), for example, Hannah Arendt also defines loneliness as a feeling that results when one’s human dignity or unconditional worth as a person fails to be recognised and affirmed, a feeling that results when this, one of the ‘basic requirements of the human condition’, fails to be met.

These accounts get a good deal about loneliness right. But they miss something as well. On these views, loving friendships allow us to avoid loneliness because the loving friend provides a form of recognition we require as social beings. Without loving friendships, or when we are apart from our friends, we are unable to secure this recognition. So we become lonely. But notice that the feature affirmed by the friend here – my unconditional value – is radically depersonalised. The property the friend recognises and affirms in me is the same property she recognises and affirms in her other friendships. Otherwise put, the recognition that allegedly mitigates loneliness in Setiya’s view is the friend’s recognition of an impersonal, abstract feature of oneself, a quality one shares with every other human being: her unconditional worth as a human being. (The recognition given by the loving friend is that I ‘[matter] … just like everyone else.’)

Just as one can feel lonely in a room full of strangers, one can feel lonely in a room full of friends

Since my dignity or worth is disconnected from any particular feature of myself as an individual, however, my friend can recognise and affirm that worth without acknowledging or engaging my particular needs, specific values and so on. If Setiya is calling it right, then that friend can assuage my loneliness without engaging my individuality.

Or can they? Accounts that tie loneliness to a failure of basic recognition (and the alleviation of loneliness to love and acknowledgement of one’s dignity) may be right about the origin of certain forms of loneliness. But it seems to me that this is far from the whole picture, and that accounts like these fail to explain a wide variety of familiar circumstances in which loneliness arises.

When I came home from my study-abroad semester, I returned to a network of robust, loving friendships. I was surrounded daily by a steadfast group of people who persistently acknowledged and affirmed my unconditional value as a person, putting up with my obnoxious pretension (so it must have seemed) and accepting me even though I was alien in crucial ways to the friend they knew before. Yet I still suffered loneliness. In fact, while I had more close friendships than ever before – and was as close with friends and family members as I had ever been – I was lonelier than ever. And this is also true of the familiar scenarios from above: the first-year college student, the new parent, the travel nurse, and so on. All these scenarios are ripe for painful feelings of loneliness even though the individuals undergoing such experiences have a loving network of friends, family and colleagues who support them and recognise their unconditional value.

So, there must be more to loneliness than Setiya’s account (and others like it) let on. Of course, if an individual’s worth goes unrecognised, she will feel awfully lonely. But just as one can feel lonely in a room full of strangers, one can feel lonely in a room full of friends. What plagues accounts that tie loneliness to an absence of basic recognition is that they fail to do justice to loneliness as a feeling that pops up not only when one lacks sufficiently loving, affirmative relationships, but also when one perceives that the relationships she has (including and perhaps especially loving relationships) lack sufficient quality (for example, lacking depth or a desired feeling of connection). And an individual will perceive such relationships as lacking sufficient quality when her friends and family are not meeting the specific needs she has, or recognising and affirming her as the particular individual that she is.

We see this especially in the midst or aftermath of transitional and transformational life events, when greater-than-usual shifts occur. As the result of going through such experiences, we often develop new values, core needs and centrally motivating desires, losing other values, needs and desires in the process. In other words, after undergoing a particularly transformative experience, we become different people in key respects than we were before. If after such a personal transformation, our friends are unable to meet our newly developed core needs or recognise and affirm our new values and central desires – perhaps in large part because they cannot , because they do not (yet) recognise or understand who we have become – we will suffer loneliness.

This is what happened to me after Italy. By the time I got back, I had developed new core needs – as one example, the need for a certain level and kind of intellectual engagement – which were unmet when I returned home. What’s more, I did not think it particularly fair to expect my friends to meet these needs. After all, they did not possess the conceptual frameworks for discussing Russian absurdism or 13th-century Italian love sonnets; these just weren’t things they had spent time thinking about. And I didn’t blame them; expecting them to develop or care about developing such a conceptual framework seemed to me ridiculous. Even so, without a shared framework, I felt unable to meet my need for intellectual engagement and communicate to my friends the fullness of my inner life, which was overtaken by quite specific aesthetic values, values that shaped how I saw the world. As a result, I felt lonely.

I n addition to developing new needs, I understood myself as having changed in other fundamental respects. While I knew my friends loved me and affirmed my unconditional value, I did not feel upon my return home that they were able to see and affirm my individuality. I was radically changed; in fact, I felt in certain respects totally unrecognisable even to those who knew me best. After Italy, I inhabited a different, more nuanced perspective on the world; beauty, creativity and intellectual growth had become core values of mine; I had become a serious lover of poetry; I understood myself as a burgeoning philosopher. At the time, my closest friends were not able to see and affirm these parts of me, parts of me with which even relative strangers in my college courses were acquainted (though, of course, those acquaintances neither knew me nor were equipped to meet other of my needs which my friends had long met). When I returned home, I no longer felt truly seen by my friends .

One need not spend a semester abroad to experience this. For example, a nurse who initially chose her profession as a means to professional and financial stability might, after an especially meaningful experience with a patient, find herself newly and centrally motivated by a desire to make a difference in her patients’ lives. Along with the landscape of her desires, her core values may have changed: perhaps she develops a new core value of alleviating suffering whenever possible. And she may find certain features of her job – those that do not involve the alleviation of suffering, or involve the limited alleviation of suffering – not as fulfilling as they once were. In other words, she may have developed a new need for a certain form of meaningful difference-making – a need that, if not met, leaves her feeling flat and deeply dissatisfied.

Changes like these – changes to what truly moves you, to what makes you feel deeply fulfilled – are profound ones. To be changed in these respects is to be utterly changed. Even if you have loving friendships, if your friends are unable to recognise and affirm these new features of you, you may fail to feel seen, fail to feel valued as who you really are. At that point, loneliness will ensue. Interestingly – and especially troublesome for Setiya’s account – feelings of loneliness will tend to be especially salient and painful when the people unable to meet these needs are those who already love us and affirm our unconditional value.

Those with a strong need for their uniqueness to be recognised may be more disposed to loneliness

So, even with loving friends, if we perceive ourselves as unable to be seen and affirmed as the particular people we are, or if certain of our core needs go unmet, we will feel lonely. Setiya is surely right that loneliness will result in the absence of love and recognition. But it can also result from the inability – and sometimes, failure – of those with whom we have loving relationships to share or affirm our values, to endorse desires that we understand as central to our lives, and to satisfy our needs.

Another way to put it is that our social needs go far beyond the impersonal recognition of our unconditional worth as human beings. These needs can be as widespread as a need for reciprocal emotional attachment or as restricted as a need for a certain level of intellectual engagement or creative exchange. But even when the need in question is a restricted or uncommon one, if it is a deep need that requires another person to meet yet goes unmet, we will feel lonely. The fact that we suffer loneliness even when these quite specific needs are unmet shows that understanding and treating this feeling requires attending not just to whether my worth is affirmed, but to whether I am recognised and affirmed in my particularity and whether my particular, even idiosyncratic social needs are met by those around me.

What’s more, since different people have different needs, the conditions that produce loneliness will vary. Those with a strong need for their uniqueness to be recognised may be more disposed to loneliness. Others with weaker needs for recognition or reciprocal emotional attachment may experience a good deal of social isolation without feeling lonely at all. Some people might alleviate loneliness by cultivating a wide circle of not-especially-close friends, each of whom meets a different need or appreciates a different side of them. Yet others might persist in their loneliness without deep and intimate friendships in which they feel more fully seen and appreciated in their complexity, in the fullness of their being.

Yet, as ever-changing beings with friends and loved ones who are also ever-changing, we are always susceptible to loneliness and the pain of situations in which our needs are unmet. Most of us can recall a friend who once met certain of our core social needs, but who eventually – gradually, perhaps even imperceptibly – ultimately failed to do so. If such needs are not met by others in one’s life, this situation will lead one to feel profoundly, heartbreakingly lonely.

In cases like these, new relationships can offer true succour and light. For example, a lonely new parent might have childless friends who are clueless to the needs and values she develops through the hugely complicated transition to parenthood; as a result, she might cultivate relationships with other new parents or caretakers, people who share her newly developed values and better understand the joys, pains and ambivalences of having a child. To the extent that these new relationships enable her needs to be met and allow her to feel genuinely seen, they will help to alleviate her loneliness. Through seeking relationships with others who might share one’s interests or be better situated to meet one’s specific needs, then, one can attempt to face one’s loneliness head on.

But you don’t need to shed old relationships to cultivate the new. When old friends to whom we remain committed fail to meet our new needs, it’s helpful to ask how to salvage the situation, saving the relationship. In some instances, we might choose to adopt a passive strategy, acknowledging the ebb and flow of relationships and the natural lag time between the development of needs and others’ abilities to meet them. You could ‘wait it out’. But given that it is much more difficult to have your needs met if you don’t articulate them, an active strategy seems more promising. To position your friend to better meet your needs, you might attempt to communicate those needs and articulate ways in which you don’t feel seen.

Of course, such a strategy will be successful only if the unmet needs provoking one’s loneliness are needs one can identify and articulate. But we will so often – perhaps always – have needs, desires and values of which we are unaware or that we cannot articulate, even to ourselves. We are, to some extent, always opaque to ourselves. Given this opacity, some degree of loneliness may be an inevitable part of the human condition. What’s more, if we can’t even grasp or articulate the needs provoking our loneliness, then adopting a more passive strategy may be the only option one has. In cases like this, the only way to recognise your unmet needs or desires is to notice that your loneliness has started to lift once those needs and desires begin to be met by another.

Film and visual culture

The risk of beauty

W Eugene Smith’s photos of the Minamata disaster are both exquisite and horrifying. How might we now look at them?

Joanna Pocock

Sleep and dreams

Spinning the night self

After years of insomnia, I threw off the effort to sleep and embraced the peculiar openness I found in the darkest hours

Annabel Abbs

History of ideas

Philosophy of the people

How two amateur schools pulled a generation of thinkers from the workers and teachers of the 19th-century American Midwest

Joseph M Keegin

Nature and landscape

Laughing shores

Sailors, exiles, merchants and philosophers: how the ancient Greeks played with language to express a seaborne imagination

Giordano Lipari

Virtues and vices

Make it awkward!

Rather than being a cringey personal failing, awkwardness is a collective rupture – and a chance to rewrite the social script

Alexandra Plakias

Metaphysics

Desperate remedies

In order to make headway on knotty metaphysical problems, philosophers should look to the methods used by scientists

13 Writing Prompts for When You’re Feeling Lonely

How to Navigate Loneliness Through Writing

Have you ever felt lonely?

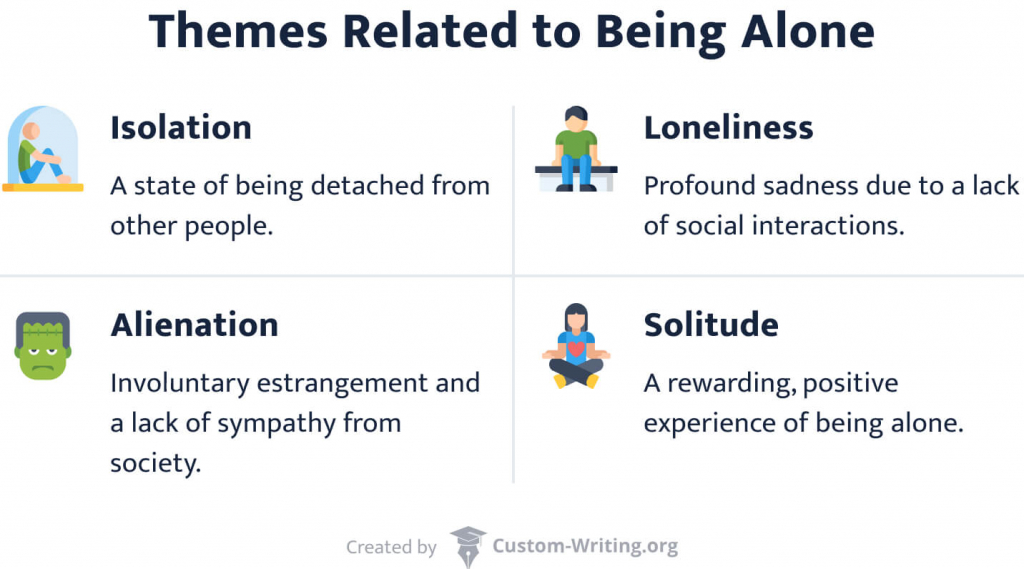

Loneliness is a subjective experience of social isolation and disconnection. It is different from being alone, which is simply the state of not being around other people. Loneliness can be caused by a variety of factors, including social isolation, lack of close relationships, and poor self-esteem.

Loneliness is often considered problematic for one's mental wellness because it can lead to a number of negative consequences, including:

Depression: Loneliness is a major risk factor for depression. In fact, studies have shown that loneliness can be as harmful to your mental health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

Anxiety: Loneliness can also increase anxiety levels. This is because loneliness can make you feel insecure and threatened, which can lead to feelings of worry and fear.

Sleep problems: Loneliness can also disrupt your sleep patterns. This is because loneliness can increase levels of the stress hormone cortisol, which can make it difficult to fall asleep and stay asleep.

Physical health problems: Loneliness has also been linked to a number of physical health problems, including heart disease, stroke, and dementia.

However, loneliness can sometimes be considered beneficial. For example, some research suggests that loneliness can lead to increased creativity and introspection. Additionally, loneliness can sometimes motivate people to reach out to others and build stronger relationships.

Overall, the effects of loneliness on mental wellness are complex and depend on a variety of factors. While loneliness can be harmful in many cases, it can also be beneficial in some situations. If you are feeling lonely, it is important to reach out for help and support. Here are some things you can do to cope with loneliness and improve your mental wellness:

Reach out to friends and family: Let them know how you're feeling and see if they can offer support.

Get involved in activities or groups: This is a great way to meet new people and make connections.

Seek professional help: If your loneliness is severe, a therapist can help you to understand your feelings and develop coping mechanisms.

Remember, you are not alone, even in this! There are many people who feel lonely, and there are resources available to help you. Continue reading for more.

Writing Prompts:

Another powerful tool in managing feelings of loneliness is journaling. Here are 13 writing prompts for the next time you're feeling lonely:

Describe what loneliness feels like to you. What physical sensations do you experience? What emotions do you feel? What thoughts go through your mind?

Write about a time when you felt particularly lonely. What was the situation? How did you cope with your feelings? What did you learn from the experience?

Write a letter to someone you feel lonely without. What would you say to them? What would you miss about them?

Write about your hopes and dreams for the future. How do you imagine your life without loneliness? What steps can you take to make your dreams a reality?

Write about your strengths and accomplishments. What are you good at? What have you achieved in your life?

Write about your values and beliefs. What is important to you in life? What do you stand for?

Write about your goals and aspirations. What do you want to achieve in life? What steps are you taking to reach your goals?

Write about your fears and insecurities. What are you afraid of? What makes you feel insecure?

Write about your relationships with others. Who are the important people in your life? How do you connect with them?

Write about your hobbies and interests. What do you enjoy doing in your free time? How do your hobbies make you feel?

Write about your thoughts on loneliness. What do you think causes loneliness? What are the effects of loneliness? What can be done to overcome loneliness?

Write a poem or short story about loneliness. Use your imagination to create a story that captures the essence of loneliness.

Write a letter to yourself in the future. What advice would you give yourself about dealing with loneliness?

I hope these prompts help you to explore your feelings of loneliness and to find ways to cope with them. Even in your darkest moments, always remember this; you are not alone.

Keep Going!

Check out these related posts

Is your environment affecting your mood? Discover how decluttering can boost mental well-being and unlock your potential.

Nightmares aren't just scary dreams; they hold clues to your inner world. Learn how to unlock their hidden messages and improve your life.

Why do we crave romantic partnerships? Uncover the psychological and biological roots of human connection.

KIRU is an American music and social artist, author and entrepreneur based in Brooklyn, New York.

Day One Hundred One: Embracing Uncertainty and Taking Risks

Day one hundred: creating genuine connections through vulnerability and authenticity.

Loneliness Essay

To be lonely is an easy thing, being alone is another matter entirely. To understand this, first one must understand the difference between loneliness and being alone. To be alone means that your are not in the company of anyone else. You are one. But loneliness can happen anytime, anywhere. You can be lonely in a crowd, lonely with friends, lonely with family. You can even be lonely while with loved ones. For feeling lonely, is in essence a feeling of being alone. As thought you were one and you feel as though you will always be that way. Loneliness can be one of the most destructive feelings humans are capable of feeling. For loneliness can lead to depression, suicide, and even to raging out and hurting friends and/or …show more content…

Generally almost all loneliness can be traced back to low or below "average" self-esteem. Chronically lonely people will usually have low opinions of themselves. They may think of themselves as unintelligent, unattractive, broken, unwanted, not worthy of good things, no good, unable to do anything right, and/or socially isolated. Unlike many other emotionally hurting people, the chronically lonely usually know what is wrong, but like many others they don't believe they can do anything to fix it, or, circling back to the low self-esteem, they may also believe they are not worth of happiness. It takes the strong support of a good friend(s) or other loved one(s) to help the lonely conquer their feelings. Simply trying to counteract the low self-esteem verbally will not do it, though, for in their down state, they will see the person as just trying to be nice or spare their feelings. The lonely must be shown in more subtle, yet clear ways that they are not the useless person they perceive themselves to be. For example, with a person who feels particularly unloved and unwanted, someone close to them should try to take a little extra time to spend with that person and try to set aside a little extra time to talk to the person. Nothing special needs to be said or done, simply spending time, willing and without having been asked, allows the lonely one to see that they are loved. That they are worthy of being associated with and that there are

Nouwen (1975) describes loneliness as a universal experience that affects even the most intimate relationships. He identifies loneliness as one of the universal sources of human suffering. Some of the mental suffering in the

The Legacy of E.E. Cummings

- 7 Works Cited

Anyone can relate to the feeling of being lonely at one point in their life. In result, when someone feels lonely it’s probably because they are not around friends or family, and just want to be able to have conversation. It also could mean someone wants to stray themselves away from the crowd because they want to be alone, that being said, everyone needs those silent moments to have for themselves. However, whichever situation it may be people still feel that “loneliness” every once in a while, and that’s what this poem is relaying.

`` Speak, By The Maya Angelou

Lonely is not being alone, but the feeling that no one cares. Melinda believes she is alone and needs a friend, but she thinks that she does not need a true close friend, that she can make it through it alone. Melinda could learn from angelou that you need someone. On page 22, it says, “I need a new friend. I need a new friend, period. Not a true friend, nothing close or share clothes or sleepover giggle giggle yak yak. Just a pseudo-friend, disposable friend. Friends as accessories. Just so I don’t feel or look stupid.” while she agrees she needs a friend, she thinks she does not have to be close enough to talk, to confide in.which results in her misery. In Angelou’s poem, Alone, in stanza 5, she quotes, “ now if

Of Mice and Men Essay on Loneliness

“Actually, feeling lonely has little to do with how many friends you have. It 's the way you feel inside. Some people who feel lonely may rarely interact with people and others who are surrounded by people but don 't feel connected” (Karyn Hall 2013). Truthfully, loneliness is something almost all people fear. It 's a deeper feeling then just being isolated. It 's feeling distant or disconnected from others. Loneliness is so much more than just feeling secluded, it 's feeling rejected by society, or even like an outcast. In Of Mice and Men, John Steinbeck suggests that there is a deeper meaning to being lonely than just the superficial sense of

Of Mice And Men Symbolism Analysis

Many choose to disregard this loneliness ahead in exchange for their lighter, brighter dreams. There are, after all, still so many places left to go and so many people left to see. However, all endings in life, whether that ending concerns relationships, dreams, or death, are of solitude. Coming to terms with this is necessary in order to find peace and to live with purpose. It opens the eyes to a hidden truth— loneliness will continue to be a companion through the entirety of

Loneliness In John Steinbeck's Of Mice And Men

Differentiating from attention seeking to isolation, loneliness has numerous factors. However, people have various ways in showing that they’re lonely even if words aren’t spoken. It can be shown verbally, physically and emotionally. During the course of the novel, countless circumstances were revealed. Whether it were in the characters that were talked today, to the characters like Lennie, and George, almost all of the characters in the book had a sense of loneliness in them. Some people may discover that picking fights with people is how they’ll deal with solitude. On the other hand people may look for the extra attention to consume their feelings of aloneness. Like said at the beginning, being lonely can both be good and bad. Someone may be able to become more successful in life alone, or another may need the help of others to become successful. Everybody’s different in their own way, and everyone has their own way of dealing loneliness. It comes and goes and sometimes people are hit harder than others. Feeling lonely is a natural obstacle everyone must overcome, it’ll be a long way down the road, but it’ll all be worth it in the

Battling Addiction Research Paper

To better establish your self-worth, focus on the positives. Consider keeping a journal and writing down all the things you’ve done right and all the greatness you have to offer. This can help improve your confidence and dispel feelings of social rejection.

The War Of Every Man

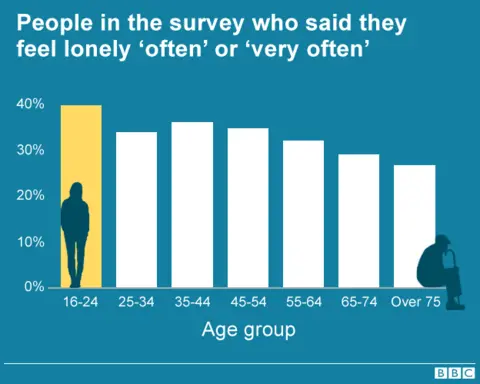

Loneliness has become an epidemic among young adults and spared out in elders’ everyday life where social isolation has become a cause of early death because we cannot cope alone.

Loneliness In To Kill A Mockingbird

All kinds of people will feel loneliness and sometimes the innocent feel the loneliest. The importance of life is experiencing loneliness. People do not remember every emotion they have felt but we will always remember the feeling of being lonely. No matter how strong someone is or how happy someone seems to be. Loneliness have infected their lives and changed them. The timeless novel To kill a mockingbird teaches one of the many universal lessons, that everyone experiences loneliness. Harper Lee clearly shows that loneliness exists in the community of Maycomb through the characters Mayella Ewell, Boo Radley, and Mrs. Dubose.

Examples Of Loneliness In The Great Gatsby

Contrary to popular belief, loneliness is not something that is detected through the outside appearance. Most people who are feeling lonely are involved in outward interactions; it is when that person is internally analyzing their life that they find that they are lonely. While reading “The Great Gatsby” my senior year, there was a phrase Nick used that always stuck with me. It's a phrase that captures the concept of loneliness perfectly. It simply says, “The loneliest moment in someone’s life

College Admissions Essay: How Loneliness Changed My Life

“Pray that your loneliness may spur you into finding something to live for, great enough to die for” (Dag Hammarskjold). Loneliness is a scary thing. As a child, I was very shy and timid and I suffered from it. My life was sheltered by my parents and I desperately wanted a sibling. Along with my parents, the private school I had gone to all my life never gave me the experience of stranger interaction. The thought of starting a conversation with someone I have never met made me drench in sweat. I dreaded the day of going to a public high school. Never in my dreams would I have imagined how it would affect my life and mold me into the person I am today.

Essay Emerging Adulthood

As I stated earlier, experiencing loneliness at this time is not uncommon. These feelings can come from not having many close friends or someone to share companionship with. However, having many close friends does not suffice for the lack of a companion. The feelings you have for a partner are different than those you may have for a friend. Attending new schools and applying to new jobs forces people to go through, what can be a tough time in a lot of peoples lives. Building relationships constantly that often are not maintained can contribute to a person’s feelings of loneliness.

Diary Of A Young Girl Anne Frank Essay

“The best remedy for those who are afraid, lonely, or unhappy is to go outside... Because only then does one feel that all is as it should be”(Anne Frank). In the story, “Diary of a Young Girl”, by Anne Frank, Anne is a young Jewish girl who has to flee into hiding during the Holocaust and writes in her diary about what goes on. At the beginning Anne is sociable, but as the war progresses she becomes lonely. Therefore I believe that loneliness can change a person.

Cast Away Analysis

Oftentimes, people confuse loneliness with the state of being alone. When looking at the overall big picture, it is easy to forget that loneliness is temporary. People are not alone because even back in primitive times, they bore a natural instinct to strive for companionship in order to survive. Human imagination creates companions in cases of extreme loneliness which contradicts the state of being alone. Due to societal and family standards, others in society make it practically impossible to be alone. Mankind often goes through life without realizing the overwhelming amount of human contact and support. People are never alone, they are just simply

The True State Of Loneliness

There have been numerous interpretations of the true state of loneliness, but how is it really defined? Would you think that a person isolated in the corner of the room socially withdrawn from the crowed is lonely or someone surrounded by their group of friends playing and laughing around? The fact of the matter is it could be both individuals, there is no telling what they feel on the inside unless you can figure out the signs and symptoms and analyze their background information in history. Some may not too choose to believe it but someone close to you can be suffering from this condition.

Essay On Loneliness

Introduction: Loneliness is a complex and usually unpleasant emotional response to isolation. It refers to a state of being alone. It is a moment when one feels sad because of being cut off from one’s near and dear ones either physically or psychologically. The extreme case of physical loneliness would be solitary confinement in a prison or being marooned on an island like Robinson Crusoe, Alexander Selkirk, etc. It has also been described as social pain a psychological mechanism meant to motivate an individual to seek social connections.

Loneliness is to be clearly distinguished from solitude as unlike the latter, it is always an unwelcomed feeling to which one is subject out of some external or inner compulsions. It is beyond one’s control whereas many persons would occasionally prefer enjoying solitude, far from the madding crowds.

Loneliness is often defined in terms of one’s connectedness to others, or more specifically as “the unpleasant experience that occurs when a person’s network of social relations is deficient in some important way”.

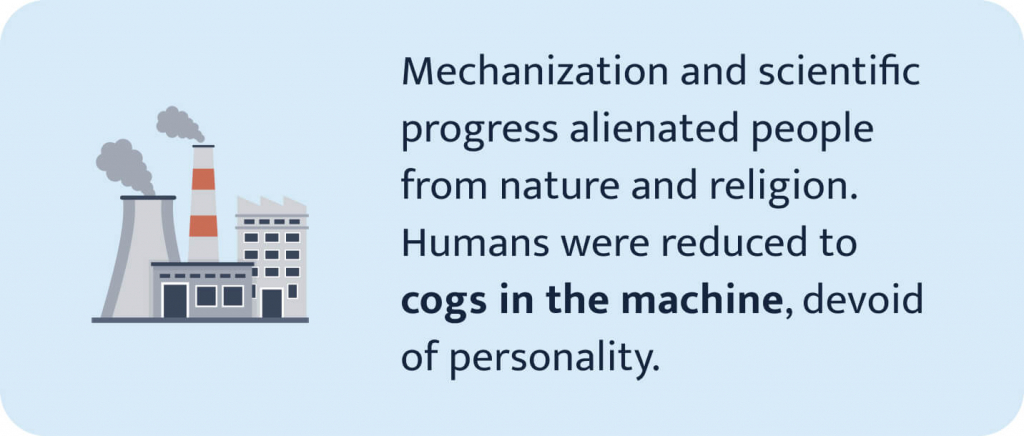

Grounds of Loneliness: Man faces an increasing incidence of loneliness because of the fast-changing social and economic conditions of modern times. It is a comparatively recent phenomenon: Close quite primitive groups bring out a precarious existence by hunting wild animals or eating wild fruits would not experience loneliness as they would always engage collectively in life-supporting activities.

Later settled agricultural communities were land-based and had a little occasion for feeling loneliness for the individuals who had strong ties with their families and village communities. They were alone neither in their joys nor in their sorrows as both the conditions brought them together for intensifying the joys and reducing the sorrow by sharing.

Loneliness can also be seen as a social phenomenon, capable of spreading like a disease. When one person in a group begins to feel lonely, this feeling can spread to others, increasing everybody’s risk for feelings of loneliness. People can feel lonely even when they are surrounded by other people.

Individual’s levels of loneliness typically remain more or less constant during adulthood until 75 to 80 years of age, when they increase somewhat. Prolonged loneliness is associated with depression, poor social support, neuroticism, and introversion. Studies have shown that loneliness puts people at risk for physical disease and that it may contribute to a shortened life span.

The Risks of Loneliness: Loneliness typically includes anxious feelings about a lack of connection or communication with other beings, both in the present and extending into the future. It can be a risk factor for heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, arthritis, among other critical diseases. Lonely people are also twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

At the root, isolation compromises immunity increases the production of stress hormones and is harmful to sleep. All of this feeds chronic inflammation, which lowers immunity to the degree that lonely people even suffer more from the common cold. Loneliness can be a chronic stress condition that ages the body and causes damage to overall well-being.

Psychological Aspect: Loneliness may often grow out of some psychological compulsions. A person may suffer from an inferiority complex that he is unwanted or unloved. He/she will naturally avoid routine contact with others for fear of being repulsed or rebuffed. He/she will feel secure only when he is alone. He/she who cannot enjoy a company cannot enjoy real happiness which consists mostly of interaction with others or in getting appreciation or approval from others.

Conclusion: Loneliness is both pleasing and boring. It is correlated with social anxiety, social inhibition (shyness), sadness, hostility, distrust, and low self-esteem, characteristics that hamper one’s ability to interact in skillful and rewarding ways. Circumstantial loneliness causes no pains but forcide loneliness is bordom. But the person who has seen death from close quarters finds the true and real meaning of life. Similarly a person, who has undergone the experience of loneliness for a substantional time, keenly feels the joy of social interaction such a person realizes the true dimension of security and relaxation, one experiences in the company of one’s family members or dear friends. Experiences of loneliness strengthen social ties and convert even loners into social beings.

A Visit to an Export Fair

Food Problem in Third World Countries

Public Health System

Pat Animal – The Cat

Retail banking

Human Foot Found on Footpath Sparks “Very Strange” Appeal from Police

Biography of Joe Paterno

Although it may be Enjoyable, Floating in Space is Difficult on Earthly Bodies, According to a Study

Aggravated Assault

Biography of Gerard Piqué

Latest post.

Magnesium Orotate

Magnesium Malate

Study Indicates Recommended Exercise for Type 1 Diabetic Patients

ADHD Stimulants may Raise the Risk of Heart Disease in Young People, a study finds

Bismuth Ferrite – an inorganic chemical compound

Terbium Monoselenide – an inorganic compound

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Life Obstacles

Life Experience Of Loneliness

*minimum deadline

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below

- Self Assessment

- Grandparent

Related Essays

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The History of Loneliness

The female chimpanzee at the Philadelphia Zoological Garden died of complications from a cold early in the morning of December 27, 1878. “Miss Chimpanzee,” according to news reports, died “while receiving the attentions of her companion.” Both she and that companion, a four-year-old male, had been born near the Gabon River, in West Africa; they had arrived in Philadelphia in April, together. “These Apes can be captured only when young,” the zoo superintendent, Arthur E. Brown, explained, and they are generally taken only one or two at a time. In the wild, “they live together in small bands of half a dozen and build platforms among the branches, out of boughs and leaves, on which they sleep.” But in Philadelphia, in the monkey house, where it was just the two of them, they had become “accustomed to sleep at night in each other’s arms on a blanket on the floor,” clutching each other, desperately, achingly, through the long, cold night.

The Philadelphia Zoological Garden was the first zoo in the United States. It opened in 1874, two years after Charles Darwin published “The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals,” in which he related what he had learned about the social attachments of primates from Abraham Bartlett, the superintendent of the Zoological Society of London:

Many kinds of monkeys, as I am assured by the keepers in the Zoological Gardens, delight in fondling and being fondled by each other, and by persons to whom they are attached. Mr. Bartlett has described to me the behavior of two chimpanzees, rather older animals than those generally imported into this country, when they were first brought together. They sat opposite, touching each other with their much protruded lips; and the one put his hand on the shoulder of the other. They then mutually folded each other in their arms. Afterwards they stood up, each with one arm on the shoulder of the other, lifted up their heads, opened their mouths, and yelled with delight.

Mr. and Miss Chimpanzee, in Philadelphia, were two of only four chimpanzees in America, and when she died human observers mourned her loss, but, above all, they remarked on the behavior of her companion. For a long time, they reported, he tried in vain to rouse her. Then he “went into a frenzy of grief.” This paroxysm accorded entirely with what Darwin had described in humans: “Persons suffering from excessive grief often seek relief by violent and almost frantic movements.” The bereaved chimpanzee began to pull out the hair from his head. He wailed, making a sound the zookeeper had never heard before: Hah-ah-ah-ah-ah . “His cries were heard over the entire garden. He dashed himself against the bars of the cage and butted his head upon the hard-wood bottom, and when this burst of grief was ended he poked his head under the straw in one corner and moaned as if his heart would break.”

Nothing quite like this had ever been recorded. Superintendent Brown prepared a scholarly article, “Grief in the Chimpanzee.” Even long after the death of the female, Brown reported, the male “invariably slept on a cross-beam at the top of the cage, returning to inherited habit, and showing, probably, that the apprehension of unseen dangers has been heightened by his sense of loneliness.”

Loneliness is grief, distended. People are primates, and even more sociable than chimpanzees. We hunger for intimacy. We wither without it. And yet, long before the present pandemic, with its forced isolation and social distancing, humans had begun building their own monkey houses. Before modern times, very few human beings lived alone. Slowly, beginning not much more than a century ago, that changed. In the United States, more than one in four people now lives alone; in some parts of the country, especially big cities, that percentage is much higher. You can live alone without being lonely, and you can be lonely without living alone, but the two are closely tied together, which makes lockdowns, sheltering in place, that much harder to bear. Loneliness, it seems unnecessary to say, is terrible for your health. In 2017 and 2018, the former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy declared an “epidemic of loneliness,” and the U.K. appointed a Minister of Loneliness. To diagnose this condition, doctors at U.C.L.A. devised a Loneliness Scale. Do you often, sometimes, rarely, or never feel these ways?

I am unhappy doing so many things alone. I have nobody to talk to. I cannot tolerate being so alone. I feel as if nobody really understands me. I am no longer close to anyone. There is no one I can turn to. I feel isolated from others.

In the age of quarantine, does one disease produce another?

“Loneliness” is a vogue term, and like all vogue terms it’s a cover for all sorts of things most people would rather not name and have no idea how to fix. Plenty of people like to be alone. I myself love to be alone. But solitude and seclusion, which are the things I love, are different from loneliness, which is a thing I hate. Loneliness is a state of profound distress. Neuroscientists identify loneliness as a state of hypervigilance whose origins lie among our primate ancestors and in our own hunter-gatherer past. Much of the research in this field was led by John Cacioppo, at the Center for Cognitive and Social Neuroscience, at the University of Chicago. Cacioppo, who died in 2018, was known as Dr. Loneliness. In the new book “ Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World ” (Harper Wave), Murthy explains how Cacioppo’s evolutionary theory of loneliness has been tested by anthropologists at the University of Oxford, who have traced its origins back fifty-two million years, to the very first primates. Primates need to belong to an intimate social group, a family or a band, in order to survive; this is especially true for humans (humans you don’t know might very well kill you, which is a problem not shared by most other primates). Separated from the group—either finding yourself alone or finding yourself among a group of people who do not know and understand you—triggers a fight-or-flight response. Cacioppo argued that your body understands being alone, or being with strangers, as an emergency. “Over millennia, this hypervigilance in response to isolation became embedded in our nervous system to produce the anxiety we associate with loneliness,” Murthy writes. We breathe fast, our heart races, our blood pressure rises, we don’t sleep. We act fearful, defensive, and self-involved, all of which drive away people who might actually want to help, and tend to stop lonely people from doing what would benefit them most: reaching out to others.

The loneliness epidemic, in this sense, is rather like the obesity epidemic. Evolutionarily speaking, panicking while being alone, like finding high-calorie foods irresistible, is highly adaptive, but, more recently, in a world where laws (mostly) prevent us from killing one another, we need to work with strangers every day, and the problem is more likely to be too much high-calorie food rather than too little. These drives backfire.

Loneliness, Murthy argues, lies behind a host of problems—anxiety, violence, trauma, crime, suicide, depression, political apathy, and even political polarization. Murthy writes with compassion, but his everything-can-be-reduced-to-loneliness argument is hard to swallow, not least because much of what he has to say about loneliness was said about homelessness in the nineteen-eighties, when “homelessness” was the vogue term—a word somehow easier to say than “poverty”—and saying it didn’t help. (Since then, the number of homeless Americans has increased.) Curiously, Murthy often conflates the two, explaining loneliness as feeling homeless. To belong is to feel at home. “To be at home is to be known,” he writes. Home can be anywhere. Human societies are so intricate that people have meaningful, intimate ties of all kinds, with all sorts of groups of other people, even across distances. You can feel at home with friends, or at work, or in a college dining hall, or at church, or in Yankee Stadium, or at your neighborhood bar. Loneliness is the feeling that no place is home. “In community after community,” Murthy writes, “I met lonely people who felt homeless even though they had a roof over their heads.” Maybe what people experiencing loneliness and people experiencing homelessness both need are homes with other humans who love them and need them, and to know they are needed by them in societies that care about them. That’s not a policy agenda. That’s an indictment of modern life.

In “ A Biography of Loneliness: The History of an Emotion ” (Oxford), the British historian Fay Bound Alberti defines loneliness as “a conscious, cognitive feeling of estrangement or social separation from meaningful others,” and she objects to the idea that it’s universal, transhistorical, and the source of all that ails us. She argues that the condition really didn’t exist before the nineteenth century, at least not in a chronic form. It’s not that people—widows and widowers, in particular, and the very poor, the sick, and the outcast—weren’t lonely; it’s that, since it wasn’t possible to survive without living among other people, and without being bonded to other people, by ties of affection and loyalty and obligation, loneliness was a passing experience. Monarchs probably were lonely, chronically. (Hey, it’s lonely at the top!) But, for most ordinary people, daily living involved such intricate webs of dependence and exchange—and shared shelter—that to be chronically or desperately lonely was to be dying. The word “loneliness” very seldom appears in English before about 1800. Robinson Crusoe was alone, but never lonely. One exception is “Hamlet”: Ophelia suffers from “loneliness”; then she drowns herself.

Modern loneliness, in Alberti’s view, is the child of capitalism and secularism. “Many of the divisions and hierarchies that have developed since the eighteenth century—between self and world, individual and community, public and private—have been naturalized through the politics and philosophy of individualism,” she writes. “Is it any coincidence that a language of loneliness emerged at the same time?” It is not a coincidence. The rise of privacy, itself a product of market capitalism—privacy being something that you buy—is a driver of loneliness. So is individualism, which you also have to pay for.

Alberti’s book is a cultural history (she offers an anodyne reading of “Wuthering Heights,” for instance, and another of the letters of Sylvia Plath ). But the social history is more interesting, and there the scholarship demonstrates that whatever epidemic of loneliness can be said to exist is very closely associated with living alone. Whether living alone makes people lonely or whether people live alone because they’re lonely might seem to be harder to say, but the preponderance of the evidence supports the former: it is the force of history, not the exertion of choice, that leads people to live alone. This is a problem for people trying to fight an epidemic of loneliness, because the force of history is relentless.

Before the twentieth century, according to the best longitudinal demographic studies, about five per cent of all households (or about one per cent of the world population) consisted of just one person. That figure began rising around 1910, driven by urbanization, the decline of live-in servants, a declining birth rate, and the replacement of the traditional, multigenerational family with the nuclear family. By the time David Riesman published “ The Lonely Crowd ,” in 1950, nine per cent of all households consisted of a single person. In 1959, psychiatry discovered loneliness, in a subtle essay by the German analyst Frieda Fromm-Reichmann. “Loneliness seems to be such a painful, frightening experience that people will do practically everything to avoid it,” she wrote. She, too, shrank in horror from its contemplation. “The longing for interpersonal intimacy stays with every human being from infancy through life,” she wrote, “and there is no human being who is not threatened by its loss.” People who are not lonely are so terrified of loneliness that they shun the lonely, afraid that the condition might be contagious. And people who are lonely are themselves so horrified by what they are experiencing that they become secretive and self-obsessed—“it produces the sad conviction that nobody else has experienced or ever will sense what they are experiencing or have experienced,” Fromm-Reichmann wrote. One tragedy of loneliness is that lonely people can’t see that lots of people feel the same way they do.

“During the past half century, our species has embarked on a remarkable social experiment,” the sociologist Eric Klinenberg wrote in “ Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone ,” from 2012. “For the first time in human history, great numbers of people—at all ages, in all places, of every political persuasion—have begun settling down as singletons.” Klinenberg considers this to be, in large part, a triumph; more plausibly, it is a disaster. Beginning in the nineteen-sixties, the percentage of single-person households grew at a much steeper rate, driven by a high divorce rate, a still-falling birth rate, and longer lifespans over all. (After the rise of the nuclear family, the old began to reside alone, with women typically outliving their husbands.) A medical literature on loneliness began to emerge in the nineteen-eighties, at the same time that policymakers became concerned with, and named, “homelessness,” which is a far more dire condition than being a single-person household: to be homeless is to be a household that does not hold a house. Cacioppo began his research in the nineteen-nineties, even as humans were building a network of computers, to connect us all. Klinenberg, who graduated from college in 1993, is particularly interested in people who chose to live alone right about then.

I suppose I was one of them. I tried living alone when I was twenty-five, because it seemed important to me, the way owning a piece of furniture that I did not find on the street seemed important to me, as a sign that I had come of age, could pay rent without subletting a sublet. I could afford to buy privacy, I might say now, but then I’m sure I would have said that I had become “my own person.” I lasted only two months. I didn’t like watching television alone, and also I didn’t have a television, and this, if not the golden age of television, was the golden age of “The Simpsons,” so I started watching television with the person who lived in the apartment next door. I moved in with him, and then I married him.

This experience might not fit so well into the story Klinenberg tells; he argues that networked technologies of communication, beginning with the telephone’s widespread adoption, in the nineteen-fifties, helped make living alone possible. Radio, television, Internet, social media: we can feel at home online. Or not. Robert Putnam’s influential book about the decline of American community ties, “Bowling Alone,” came out in 2000, four years before the launch of Facebook, which monetized loneliness. Some people say that the success of social media was a product of an epidemic of loneliness; some people say it was a contributor to it; some people say it’s the only remedy for it. Connect! Disconnect! The Economist declared loneliness to be “the leprosy of the 21st century.” The epidemic only grew.

This is not a peculiarly American phenomenon. Living alone, while common in the United States, is more common in many other parts of the world, including Scandinavia, Japan, Germany, France, the U.K., Australia, and Canada, and it’s on the rise in China, India, and Brazil. Living alone works best in nations with strong social supports. It works worst in places like the United States. It is best to have not only an Internet but a social safety net.

Then the great, global confinement began: enforced isolation, social distancing, shutdowns, lockdowns, a human but inhuman zoological garden. Zoom is better than nothing. But for how long? And what about the moment your connection crashes: the panic, the last tie severed? It is a terrible, frightful experiment, a test of the human capacity to bear loneliness. Do you pull out your hair? Do you dash yourself against the walls of your cage? Do you, locked inside, thrash and cry and moan? Sometimes, rarely, or never? More today than yesterday? ♦

A Guide to the Coronavirus

- How to practice social distancing , from responding to a sick housemate to the pros and cons of ordering food.

- How people cope and create new customs amid a pandemic.

- What it means to contain and mitigate the coronavirus outbreak.

- How much of the world is likely to be quarantined ?

- Donald Trump in the time of coronavirus .

- The coronavirus is likely to spread for more than a year before a vaccine could be widely available.

- We are all irrational panic shoppers .

- The strange terror of watching the coronavirus take Rome .

- How pandemics change history .

Social Isolation

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

Though our need to connect is innate, many of us frequently feel alone. Loneliness is the state of distress or discomfort that results when one perceives a gap between one’s desires for social connection and actual experiences of it. Even some people who are surrounded by others throughout the day—or are in a long-lasting marriage —still experience a deep and pervasive loneliness. Research suggests that loneliness poses serious threats to well-being as well as long-term physical health.

- Identifying and Fighting Loneliness

- Loneliness, Health, and Well-Being

Whether a person lives in isolation or not, feeling a lack of social connectedness can be painful. Loneliness can be described in different ways; a commonly used measure of loneliness, the UCLA Loneliness Scale, asks individuals about a range of feelings or deficits of connection, including how often they:

feel they lack companionship

feel left out

feel “in tune” with people around them

feel outgoing and friendly

feel there are people they can turn to

Given the potential health consequences for those who feel like they have few or no supportive social connections, widespread loneliness poses a major societal challenge. But it underscores a demand for increased outreach and connection on a personal level, too.

Loneliness is as tied to the quality of one's relationships as it is to the number of connections one has. And it doesn’t only stem from heartache or isolation. A lack of authenticity in relationships can result in feelings of loneliness. For some, not having a coveted animal companion, or the absence of a quiet presence in the home (even if one has plenty of social contacts in the wider world), can trigger loneliness.

There's evidence that lonely individuals have a sort of negativity bias in evaluating social interactions. Lonely people pick up on signs of potential rejection more quickly than do others, perhaps better to avoid it and protect themselves. People who feel lonely need to be aware of this bias so as to override it in seeking out companionship.

Solitude, or time spent alone, is not inherently negative and can even be restorative or advantageous in other ways. Research suggests the reasons young people choose to be alone matter—they may do so to relax, create, or reflect, rather than to avoid other people.

Loneliness researcher John Cacioppo argues that just as you can start an exercise regimen to gain strength and improve your health, you can combat loneliness through small moves that build emotional strength and resilience . He has devised techniques for people at particularly high risk for chronic loneliness, such as soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. They may be useful to anyone.

A number of unfavorable outcomes have been linked to loneliness. In addition to its association with depressive symptoms and other forms of mental illness, loneliness is a risk factor for heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, and arthritis, among other diseases. Lonely people are also twice as likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease, research suggests. The state of chronic loneliness may trigger adverse physiological responses such as the increased production of stress hormones , hinder sleep, and result in weakened immunity.

While a person can’t die simply from feeling too lonely, findings that lonely people have higher rates of mortality and certain diseases supports the idea that, over time, chronic loneliness can play a role in increasing the risk of dying.

Feelings of loneliness and isolation affect people of all ages, although adolescents and the elderly may be especially likely to be impacted.

About 40 percent of Americans reported regularly feeling lonely in 2010, and other reports affirm that it is common for people to feel lonely at least some of the time. The high rates of reported loneliness have led some to declare an “epidemic,” though it is not clear that loneliness is increasing in younger generations.

Animal-assisted therapy might seem new, but its roots go back centuries. Explore the enduring bond between humans and animals in therapeutic settings.

Loneliness is increasingly tackled as a serious public health crisis. But solutions that focus on reducing social isolation are missing the key point. It's all about feeling needed.

We're all lonelier than ever, in our workplaces as well as in our personal lives. But we may find some hope in a surprising factor that reduces both loneliness and burnout.

Designing for solitude is not about strengthening isolation but, rather, about allowing all people to coexist—introverts, extroverts, and ambiverts alike.

If you are a recent empty nester struggling to find your new identity or a new mom wanting to create balance in your life, these suggestions can help.

Feeling lonely? Harness the power of self-talk and pattern interruption. A three-word mantra can help you pivot fast.

If you're feeling lonely, using three words can help reduce your stress and build your solitude muscle.

A recent paper discusses attachment in romantic relationships, how stable it is, and how it can be changed.

Parents are not meant to parent alone. From our earliest days as Homininae, we were different from other primates in this way. Community members stepped up to help new mothers.

Loneliness is on the rise, and for many people, turning to social media for connection has become a daily habit. Author Richard Deming explores loneliness and social media use.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Cope With Loneliness

If you or a loved one are struggling with a mental health condition, contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357 for information on support and treatment facilities in your area.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Virtually everyone experiences loneliness from time to time. The feeling can be especially noticeable around the holidays, Valentine's Day , birthdays , and times of extreme stress.

The sheer number of adults in the United States who feel lonely is quite large—in a January 2020 survey of 10,000 adults by Cigna, 61% of those surveyed said they felt lonely. However, people don’t always talk about feelings of loneliness and don’t always know what to do with these feelings.

Other than being emotionally painful, loneliness can impact people in many ways:

- Depression : A 2021 study published in Lancet Psychiatry found associations between loneliness and depressive symptoms in a group of adults 50 years old and older. Research also suggests that loneliness and depression may feed off of and perpetuate each other.

- Physical health : Several studies have linked emotional stress with depressed immunity. Other research links loneliness and depression with poorer health and well-being. Therefore, people who are experiencing loneliness are susceptible to a variety of health issues.

- Physical pain : Research shows that the areas of the brain that deal with social exclusion are the same areas that process physical pain, adding a scientific explanation to the oft-romanticized experience of a "broken heart."

Are You Feeling Lonely?

This fast and free loneliness test can help you analyze your current emotions and determine whether or not you may be feeling lonely at the moment:

If you’re experiencing loneliness, there are some things you can do about it. Below are nine strategies for dealing with loneliness.

Join a Class or Club

Whether it’s an art class, exercise class, or book club, joining a class or a club automatically exposes you to a group of people who share at least one of your interests. Check your local library or community college as well as city parks and recreation departments to see what's available.

Joining a class or club can also provide a sense of belonging that comes with being part of a group. This can stimulate creativity, give you something to look forward to during the day, and help stave off loneliness.

Volunteering for a cause you believe in can provide the same benefits as taking a class or joining a club: meeting others, being part of a group, and creating new experiences. It also brings the benefits of altruism and can help you find more meaning in your life.

In addition to decreasing loneliness, this can bring greater happiness and life satisfaction. Additionally, working with those who have less than you can help you feel a deeper sense of gratitude for what you have in your own life.

Find Support Online

Because loneliness is a somewhat widespread issue, there are many people online who are looking for people to connect with. Find people with similar interests by joining Facebook or Meetup groups focused on your passions. Check to see if any apps you use, like fitness or workout apps, have a social element or discussion board to join.

You do have to be careful of who you meet over the internet (and, obviously, don’t give out any personal information like your bank account number), but you can find real support, connection, and lasting friendships from people you meet online.

A word of caution: Social media can actually increase feelings of loneliness and cause FOMO, or "fear of missing out" so be sure to check in with yourself if you're starting to feel this way.

Strengthen Existing Relationships

You probably already have people in your life that you could get to know better or connections with family that could be deepened. If so, why not call friends more often, go out with them more, and find other ways to enjoy your existing relationships and strengthen bonds?

If you're struggling to find the motivation to reach out to your loved ones, it might be helpful to start slowly. Come up with just one supportive friend or family member who you could imagine reaching out to. It's also reassuring to know that strong social support is beneficial for your mental health.

Adopt a Pet

Pets, especially dogs and cats, offer so many benefits, and preventing loneliness is one of them. Rescuing a pet combines the benefits of altruism and companionship, and fights loneliness in several ways.