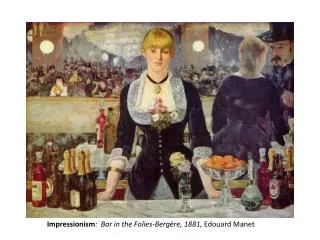

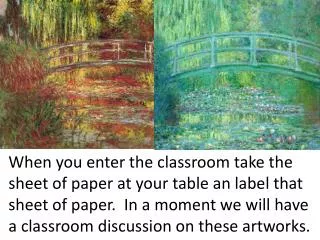

Impressionism

Summary of Impressionism

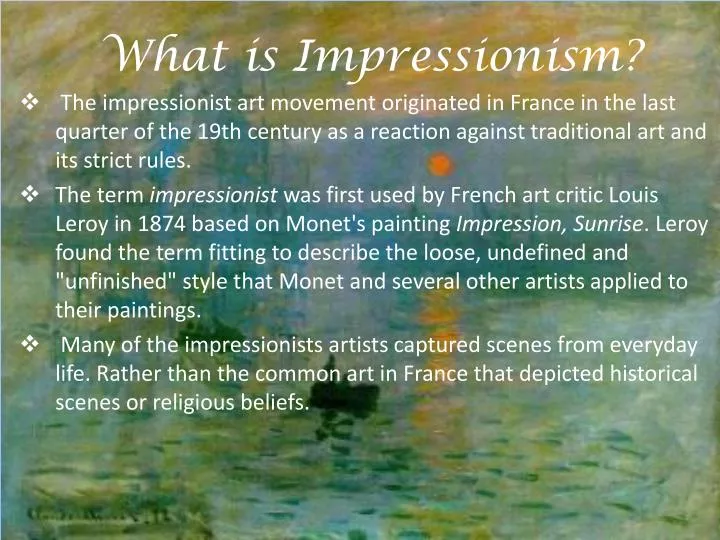

Impressionism is perhaps the most important movement in the whole of modern painting. At some point in the 1860s, a group of young artists decided to paint, very simply, what they saw, thought, and felt. They weren’t interested in painting history, mythology, or the lives of great men, and they didn’t seek perfection in visual appearances. Instead, as their name suggests, the Impressionists tried to get down on canvas an “impression” of how a landscape, thing, or person appeared to them at a certain moment in time. This often meant using much lighter and looser brushwork than painters had up until that point, and painting out of doors, en plein air . The Impressionists also rejected official exhibitions and painting competitions set up by the French government, instead organizing their own group exhibitions, which the public were initially very hostile to. All of these moves predicted the emergence of modern art , and the whole associated philosophy of the avant-garde.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- The Impressionists used looser brushwork and lighter colors than previous artists. They abandoned traditional three-dimensional perspective and rejected the clarity of form that had previously served to distinguish the more important elements of a picture from the lesser ones. For this reason, many critics faulted Impressionist paintings for their unfinished appearance and seemingly amateurish quality.

- Picking up on the ideas of Gustave Courbet , the Impressionists aimed to be painters of the real : they aimed to extend the possible subjects for paintings. Getting away from depictions of idealized forms and perfect symmetry, they concentrated on the world as they saw it, which was imperfect in a myriad of ways.

- Scientific thought in the Impressionist era was beginning to recognize that what the eye perceived and what the brain understood were two different things. The Impressionists sought to capture the former - the optical effects of light - to convey the fleeting nature of the present moment, including ambient features such as changes in weather, on their canvases. Their art did not necessarily rely on realistic depictions.

- Impressionism records the effects of the massive mid-19 th -century renovation of Paris, led by civic planner Georges-Eugène Haussmann, which included the city's newly constructed railway stations; wide, tree-lined boulevards that replaced the formerly narrow, crowded streets; and large, deluxe apartment buildings. The works that focused on scenes of public leisure - especially scenes of cafés and cabarets - often conveyed the new sense of alienation experienced by the inhabitants of the first modern metropolis.

Key Artists

Overview of Impressionism

Édouard Manet said: "You would hardly believe how difficult it is to place a figure alone on a canvas, and to concentrate all the interest on this single and universal figure and still keep it living and real." Here he hints at the innovative thinking that went into Impressionism's new way of representing the world.

Artworks and Artists of Impressionism

Le déjeuner sur l'herbe

Artist: Édouard Manet

Edouard Manet's Le déjeuner sur l'herbe (Luncheon on the Grass) was probably the most controversial artwork of the nineteenth century. It caused outrage with its frank depiction of nudity in a contemporary setting and was scorned by the high-minded salon juries and middle-class audiences of the era. But it also earned Manet fame and patronage. Rejected from the Paris Salon in 1863, it became the most controversial of the works displayed in the so-called "Salon des Refusés" held the same year in order to placate artists rejected from the main exhibition. The painting depicts two fully clothed men picnicking with a nude woman, while another scantily clad woman bathes in the background. By removing the female nude from the legitimizing contexts of mythology and orientalism, and in making his female subject confront the viewer assertively with her gaze, Manet hit a nerve in the bourgeois culture of 1860s Paris, and set the wheels of the avant-garde in motion. Édouard Manet was born in 1832 into an upper-class family with strong cultural and political ties. In terms of age, he found himself sandwiched between the generation of the great Realists , such as Gustave Courbet , and the Impressionists, most of whom were born in the 1840s. The great irony of Manet's reputation as a controversialist is that, throughout his life, he both sought and achieved mainstream success, generally having more work displayed at the official Paris Salons than his younger Impressionist peers. Similarly, although he was friendly with the Impressionists and exhibited with them - and is now often presented as one of them - his style was in some ways very different to theirs. He was far less reliant on plein-air technique than most of the Impressionists, and, whereas artists such as Monet used loose, visible brushstrokes and blended color palettes to depict subtle tonal effects, Manet preferred sharper outlines and exaggerated color contrasts, often placing dark and light areas close together (as in the contrast between naked flesh and shadow in Le déjeuner sur l'herbe ). Nonetheless, Le déjeuner sur l'herbe stands at the forefront of the whole Impressionist project in its fearless departure from inherited forms and techniques. From the subtly flattened picture plane to the defiance of time-honored motifs of high-brow nudity, everything about Manet’s painting courted shock and even ridicule. The Impressionists were inspired by Manet's example to follow their own creative paths, and while their subject-matter was generally less outrageous than Manet's nude picnic, his pioneering work cleared the space necessary for them to work in the way they wanted to.

Oil on canvas - Musée d'Orsay, Paris

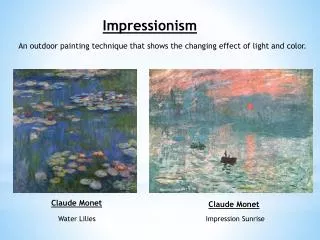

Impression, Sunrise

Artist: Claude Monet

Monet's Impressionism, Sunrise is sometimes cited as the work that gave birth to the Impressionist movement, though by the time it was painted, Monet was in fact one of a number of artists already working in the new style. Certainly, however, it was the critic Louis Leroy's derogatory comments on the work and its title, in a satirical review of the First Impressionist Exhibition of 1874, that gave rise to the term "Impressionism". Leroy's review used the term as a comic insult, but the new school of painters quickly adopted it in a spirit of pride and defiance. Claude Monet was born into a middle-class merchant family in Paris. His parents were hardworking and financially secure but by no means rich or aristocratic, and throughout his early career Monet would struggle to survive as a painter. When he was very young his family moved from Paris to Le Havre, and though Monet returned to Paris in the early 1860s to train as an artist, it was during a visit to his family in Le Havre in 1872 that he created this and a number of other similar works. What is striking about Impression, Sunrise is the continuity of the color palette between sea, land and sky. All are bathed in the gentle blues, oranges, and greens of sunrise. The subject of the painting is not the city it depicts nor the anonymous boatmen setting out across the water, but the enveloping warmth and color of sunlight itself, or rather the "impression" it makes on the senses at a certain moment in time. This painting of light and the time-specific effects of light was the hallmark of the new style. Impression, Sunrise was one of a number of sketches of the same scene that Monet created in 1872. This serial approach to subject-matter was typical for the painter. In other cases, Monet would create large cycles of work depicting the same scene at different times of day, or during different seasons, emphasizing the way in which light and atmosphere shifted in time-specific ways. The most famous examples of this effect are in the 25 paintings that make up the series Les Meules à Giverny (1890-91), known in English as "The Haystacks".

Oil on canvas - Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Fog, Voisins

Artist: Alfred Sisley

Alfred Sisley's beautiful pastoral scene showcases a gentle color-palette, evocation of tranquility and peace, and emphasis on the overall quality and atmosphere of a landscape over and above specific details and human forms. The female protagonist of this painting, serenely picking flowers, is almost entirely obscured by the dense fog that eclipses the meadow. As in much of Sisley's work, the human body seems melded into the natural scene, becoming both an aspect and expression of a wider natural world. Born in France to English parents, Alfred Sisley met Pissarro and Monet early in the formation of the group, becoming their co-students at the Swiss painter Charles Gleyre's studio in 1862. Sisley and Monet would go on to become the most dedicated and dazzling proponents of the plein air technique, but their fortunes would take them in different directions. Whereas the middle-class Monet had achieved financial success and fame by the end of his life, the silk-trader's son Sisley, born into riches, ended his days in relative poverty after his father's business failed during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. Sisley's paintings would not yield true financial success until after his death. Nonetheless, he remained prolific throughout his life, and was deeply committed to the ideals of the Impressionist school. Indeed, the example of Fog, Voisins suggests that Sisley was perhaps the most quintessential Impressionist painter of the whole group. Focusing almost exclusively on representations of light and atmosphere while diminishing the importance of the human form - an approach that many of his peers would grow weary of later in-their careers - Sisley demonstrates his all-consuming preoccupation with representing the moment of perception.

Artist: Berthe Morisot

A key artist of the Impressionist circle, Berthe Morisot is known for both her compelling portraits and her poignant landscapes. In a Park combines these elements in this serene family portrait set in a bucolic garden. Like Mary Cassatt , Morisot is recognized for her portrayals of the private and domestic spaces of female society, rather than the brash café scenes of many of her male peers. As in this quiet image of family life, she often centered on the bond between mother and child. Her loose handling of pastels, a medium embraced by the Impressionists, and visible application of color and form, were central characteristics of her work. Berthe Morisot was born in 1841 into a well-connected and rich family with ties to the Manets. Although she was a painter of prodigious skill, she was for a long time defined as a muse as much as an artist within portraits of the Impressionist circle, partly because Édouard Manet produced a large number of portraits of her, emphasizing her dark features, brooding and enigmatic persona, and subtle sexual allure (Morisot would eventually marry Manet's brother Eugéne). Morisot was the only woman included in the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874. Indeed, the presence of a woman amongst a radical clique of painters increased the controversy surrounding both them and her. Morisot had previously been a relatively successful salon painter, but for a woman to associate herself with the scandals of the new school was seen as a particular impertinence. Berthe Morisot was described by the critic Gustave Geffroy in 1894 as one of the three great female painters of Impressionism, along with Marie Bracquemond and the American Cassatt. But Morisot was the only one of these three integrated into the group from the start, involved in the founding of the Société Anonyme des Artistes, Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs and the mounting of the first, critically eviscerated group exhibitions. As such, she can be considered one of the most important painters of the Impressionist circle and one of the most important and groundbreaking female modern artists of all time.

Pastel on paper - Musee du Petit Palais, Paris

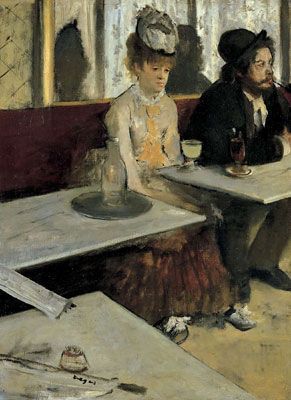

Artist: Edgar Degas

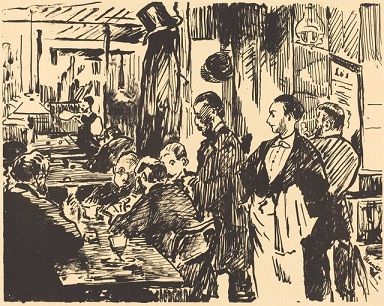

This dour scene, depicting two unfortunate individuals slumped on a bench outside a Parisian café, conveys a deep sense of isolation and degradation, revealing another side to the Impressionists' emphasis on truth to life. Degas's heavily-handled paint communicates the quality of emotional burden which his subjects convey, which in turn seems to stand for the whole oppressive atmosphere of Paris's demi-monde . The work was scandalous, like so many other Impressionist paintings, when it was first exhibited, at the second Impressionist exhibition of 1876. The Irish writer George Moore remarked of its female subject: "a life of idleness and low vice is upon her face, we read there her whole life." Born in 1834, Degas was slightly older than the majority of the Impressionist circle, and his style continued to show clear points of divergence from the group's approach throughout his career (indeed, Degas rejected the Impressionist label throughout his life). Whereas Impressionists such as Monet and Sisley turned away, to varying degrees, from depicting the physiognomy and detail of the human body, Degas remained deeply preoccupied with the human form, particularly capturing it in motion. His paintings often depict groups of bodies, either static (as above), or in motion (as in his famous paintings of ballet dancers at rehearsal), with brilliant naturalism. Degas's works also suggest an attention to detail at odds with the spontaneous style of Impressionism. Indeed, Degas was famous for his rigorous and methodical approach. He banned all visitors from his studio, working laboriously on canvases all day. "I assure you", he once said, "no art is less spontaneous than mine." What tied Degas's work to the Impressionist movement was, on the one hand, a focus on capturing spontaneity in his work, even if it was not a characteristic of composition, and on the other hand, an interest in everyday life represented for its own sake. Prior to the work of the later Realists and the Impressionists, genre painting was considered a lesser, escapist avenue of creativity. What Degas achieved with L'Absinthe and similar works was to elevate the humble and commonplace aspects of human life to the status of serious art.

Paris Street, Rainy Day

Artist: Gustave Caillebotte

While the work of Gustave Caillebotte adheres to a distinctly Realist aesthetic, it also reflects a concern with modern life that was central to Impressionism. Paris Street, Rainy Day shows this tendency within Caillebotte's oeuvre. The panoramic view of a rain-drizzled boulevard shows us the newly renovated Parisian metropolis, while the anonymous figures in the background seem to encapsulate the alienation of the individual within the modern city. The painting centers on the apathetic gaze of the male figure in the foreground, who epitomizes the cool detachment of the flâneur , poised in his characteristic black coat and top hat. Like Caillebotte's other paintings, this work explores the impact of modernity on human psychology, fleeting impressions of the street, and the effect of the changing urban sphere upon society. Caillebotte was one of the youngest artists associated with Impressionism, born into a rich upper-class family in 1848. His personal wealth meant that he was able to support fellow painters as a patron while also exhibiting alongside them. It is perhaps partly for this reason that he became connected to the group, as, despite his brilliance, there are several points of distinction in his approach. His great attention to the details of the human form, for example, and his relatively close, naturalistic brushwork, is closer in spirit to the tradition of Realism than to Impressionism. Caillebotte's work is often compared in this respect to that of Degas. Moreover, both artists were heavily influenced by photography, often framing their scenes in such a way that they seemed like snapshots rather than careful arrangements, with buildings and bodies cut in half by the edges of canvases (as above, or in Degas Place de la Concorde [1875]). In spite of these points, Caillebotte's works were important in pushing forward the Impressionist emphasis on depicting everyday life. Indeed, despite his background, he was adept at capturing the working and psychological lives of everyday Parisians: not only in scenes of middle-class urban ennui such as Paris Street , but also in scenes of physical labor such as his monumental 1875 painting The Floor Scrapers .

Oil on canvas - The Art Institute of Chicago

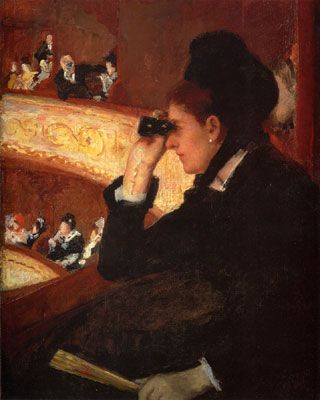

At the Opera

Artist: Mary Cassatt

Much of Mary Cassatt's work focuses on the environs and inhabitants of Paris under Haussmannization, while emphasizing, in particular, the private and public lives of women. Here, she depicts the recently-built Palais Garnier of the Paris Opera which served as a social hub for the city’s upper classes. As the painting demonstrates, the opera was not only a site of culture and entertainment but a place for seeing and being seen. The pose of the female subject, training her binoculars on the stage, is mirrored by that of the main across the concert hall, who directs his binoculars at her. Through this witty composition, Cassatt offers a playful meditation on the act of looking, a central concern of the Impressionists, and also perhaps on the lot of the female artist, who is observed and visually assessed even as she seeks to be the observer. The American expatriate Mary Cassatt was born in Pennsylvania in 1844, the daughter of a successful stockbroker. Her family was culturally conventional but she sought the life of an artist and flâneuse , training at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts before moving to Paris in 1866 (returning briefly to America during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71). Cassatt initially submitted paintings to the official Salons but she gradually became disillusioned with the conventional style and themes proffered by the judges and by the implicit snobbery and sexism of Paris's artistic establishment. By the late 1870s she had become friendly with the Impressionists and her work had begun to mirror theirs in form and subject-matter. Like many of her women counterparts, she focused a good deal on female subjects and social worlds. As an avowed feminist, Cassatt played a key role in using Impressionist techniques to represent women’s lives, thoughts, and feelings. Her presence as an American expatriate in Paris is also symbolic of the strong relationship between French Impressionism and North America from the 1880s onwards. It was after their exposure to the American market, after all, that the Impressionists finally found real financial success.

Oil on canvas - Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Boston, Massachusetts

Girl with a Hoop

Artist: Pierre-Auguste Renoir

In the mid-1880s, Renoir was commissioned to create a portrait of a nine-year-old girl, Marie Goujon. A few year prior, following a trip to Italy, he had been inspired by the work of Renaissance painters to develop a new style which he dubbed "aigre" ("sour"), indicating a new emphasis on hardness and clarity of form. Using the "aigre" technique to create his new painting, he applied thick, elongated brushstrokes to evoke natural movement in the backdrop of the work and soft, textural brushstrokes complemented by hard lines to portray the young girl in the foreground. Though the painting represents a jump forward in Renoir's technique, his fluid handling of paint and portrayal of the young girl at play evokes the carefree mood of his entire oeuvre. While the other Impressionists focused on existential themes such as alienation in modern society, Renoir's disposition remained lighthearted, with much of his work depicting leisure activities and beautiful women. Born in 1841, Renoir was from a far more modest background than many of his peers, his father a tailor who moved the family to Paris to improve their prospects. In 1862 Renoir enrolled at Charles Gleyre's studio, where he met Monet and Sisley, and so became one of the original members of the nascent Impressionist grouping. Like Monet, Renoir loved to employ natural light in his paintings. However, by the 1880s he had become dissatisfied with capturing fleeting visual effects. Having felt he had "wrung Impressionism dry," and losing all inspiration or will to paint, Renoir began to search for more clarity of form. The result of this process was his discovery of the "aigre" technique. In moving from the depiction of momentary perception to a more expressionistic use of brushwork, Renoir's development as a painter later in his career predicts the emergence of Post-Impressionism, whereby brushwork become ever more deliberative and idiosyncratic. For this reason and others, including his proximity to the other key artists of the movement, Renoir was one of the most important figures of the Impressionist generation.

Oil on canvas - The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

The Boulevard Montmartre, Afternoon

Artist: Camille Pissarro

Pissarro's Boulevard Montmartre, Afternoon applies the techniques of his earlier plein-air landscapes to the modern city. The work uses broad strokes of paint, carefully applied to the canvas, to represent the fleeting nature of modern life, and the visual impression made by the metropolis. It is one of a series of paintings, painted in Pissarro's room at the Hotel de Russie overlooking the street, that depict the same scene during different points of the day and different seasons of the year. The series emphasizes the changing effects of natural light upon the urban setting, resulting in a reflection on the passage of time and the transformation of the city. Pissarro was one of the oldest of the Impressionist group, referred to by Cézanne as "the first Impressionist." Of mixed Jewish-French-Portuguese heritage, he was born into a merchant family in 1830 on the tiny Caribbean island of St. Thomas. Pissarro's early paintings depict the sun-drenched beaches and palm trees of his island home, but he attended boarding school in Paris as a child, and moved there permanently in 1855. He became respected amongst the other Impressionist painters both for his artistic skill and for his wisdom, his works characterized by a bright palette, depiction of quiet landscapes, and representation of natural light. Pissarro served as a mentor to many of his younger friends, including Paul Cézanne, and was among the most radical of the Impressionist painters. Indeed, Pissarro saw their decision to form the Société Anonyme des Artistes, Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs in 1874 as a politically significant one, matching his anarchist ideals of self-government. The only artist to have shown his work at all eight of the Impressionist's group exhibitions (1874-86), Pissarro also taught a number of Post-Impressionist artists, including Georges Seurat - pioneer of Pointillist techniques - Vincent Van Gogh, and Paul Gauguin. Pissarro's significance as both an artist and teacher to the development of modern art in the late-nineteenth century cannot be overstated.

Oil on canvas - The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg

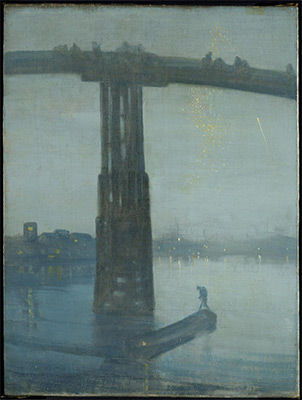

Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge

Artist: James Abbott McNeill Whistler

Whistler's Nocturne: Blue and Gold is one of the most dazzling works of the wider Impressionist movement. Produced at a time of urban reconstruction in London, it depicts the old Battersea Bridge in the south of the city from a riverbank perspective, with the lights of the newer Albert Bridge winking in the background while rockets cascade from the sky. It is one of a whole series of Nocturne paintings which convey the stillness, beauty, and subtle foreboding of London's nighttime atmosphere. Whistler deploys an Impressionist emphasis on individual, time-bound perspective in a context wholly different to the busy street-scenes of the Parisian school. The art critic Frances Spalding describes the innovative technique Whistler used to create his Nocturnes . "[I]n the early 1870s he developed a system and a formula which he could vary with subtle effect. He would mix his colours beforehand, using a lot of medium, until he had, as he called it, a 'sauce'. Then, on a canvas often prepared with a red ground to force up the blues and suggest darkness behind, he would pour on the fluid paint, often painting on the floor to prevent the paint running off, and, with long strokes of the brush pulled from one side to another, would create the sky, buildings and river, subtly altering the tones where necessary and blending them with the utmost skill." Whistler then added individual features such as the barge and figure in this painting, which often appear ghostly or translucent against the background wash. Whistler was strongly informed by Japonism, particularly Japanese woodblock printing which is reflected in his Nocturne series. This explains the subtly Oriental mood conveyed by the exaggerated shape of the barge in the water. At the same time, the curious profile perspective, which cuts off a large section of the bridge from view, suggests the position of an individual human viewer on the riverbank, while the depiction of two fireworks in the sky, one ascending and the other exploding, locates the image precisely in a single moment in time. It is perhaps for this reason that the title for this work and others, Nocturne , refers to a musical composition evocative of night, connecting the works to the time-bound medium of music. Whistler's Nocturnes caused outrage when first exhibited, provoking the Victorian critic John Ruskin to such harsh attacks that Whistler took him to court. In the decades following its composition, however, this and other paintings became recognized as masterpieces of a distinctly modern style. As Spalding notes, Whistler's works convey an ineffable, almost magical quality: "out of the decorative unity ... grow atmosphere and mystery, the sense that the visible world thinly veils the inexplicable".

Oil on canvas - Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom

Beginnings of Impressionism

Realism, naturalism, and the challenge to official art.

Although it was a revolutionary movement, Impressionism had roots in other styles of painting, such as Realism and Naturalism, that were already challenging conventional notions of artistic beauty and the artist’s relationship with the state.

The Realism movement , championed by Gustave Courbet , was the first to confront the official Parisian art establishment, in the middle of the 19 th century. Courbet was an anarchist who thought that the art of his time closed its eyes on realities of life. The French were ruled by an oppressive regime and much of the public was in the throes of poverty. Instead of depicting such scenes, the artists of the time concentrated on idealized nudes, classical and mythological narratives, and glorifying depictions of nature. As an act of protest, Courbet financed an exhibition of his work directly opposite the Universal Exposition in Paris of 1855, a bold act that inspired future artists who sought to challenge the status quo.

At the same time, the emergence of Naturalism - a movement closely associated with Realism - showed how art could take the natural world for its subject-matter without cloaking it in the contexts of historical or mythological heroism. Since the 1820s, artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Jean-François Millet had been travelling to the Barbizon Forest south of Paris to create sketches en plein air of the trees, countryside, and rural laboring classes. The emergence of the Barbizon School signified the start of a global trend in painting towards depicting the natural world in all of its unadorned glory, and celebrating the lives of rural workers. While Naturalism diverges from Impressionism in its frequent emphasis on hyperreal detail - embodied by much of the work of Jules Bastien-Lepage - the Impressionists' celebration of the natural world for its own sake, and use of plein air technique, owes much to the earlier Naturalist ethos.

Exhibitions in Paris and The Salon des Refusés

In 1863, at the official yearly art salon, the all-important event of the French art world, a large number of artists were not allowed to participate, leading to public outcry. The same year, the Salon des Refusés ("Salon of the Refused") was formed in response, to allow the exhibition of works by artists who had previously been refused entrance to the official salon. The exhibited artists included Paul Cézanne , Camille Pissarro , James Whistler , and Édouard Manet . Although it was sanctioned by Emperor Napoleon III to placate the artists involved, the 1863 exhibition was highly controversial with the public, due largely to the unconventional themes and styles of works such as Manet's Le déjeuner sur l'herbe (1863), which featured clothed men and naked women enjoying an afternoon picnic (these women were not classical nudes, but modern women - possibly prostitutes - in a state of undress whose connotations were far more explicitly sexual).

Édouard Manet and the Painting Revolution

Édouard Manet was among the first and most important innovators to emerge in the public exhibition scene in Paris. Although he grew up in admiration of the Old Masters , he began to incorporate an innovative, looser painting style and brighter palette in the early 1860s. He also started to focus on images of everyday life, such as scenes in cafés, boudoirs, and on streets. His anti-academic style and quintessentially modern subject-matter soon attracted the attention of artists on the fringes and influenced a new type of painting that would diverge from the standards of the time. Works such as Olympia (1863), which, like Le déjeuner sur l'herbe , depicts a modern female nude assertively confronting the viewer, gave the emerging Impressionist group the impetus to depict subjects not previously considered art worthy.

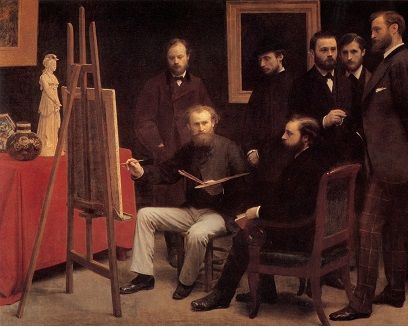

French Cafés and Diversity

Amongst the most popular venues for the painters of the emerging Impressionist movement to meet and talk were Parisian cafés. In particular, Café Guerbois in Montmartre was frequented by Manet from 1866 onwards. Pierre-Auguste Renoir , Alfred Sisley , Edgar Degas , Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, and Camille Pissarro all visited the cafe, while Caillebotte and Bazille had studios nearby, and would often join the gatherings. Other personalities were attracted to this group, including writers, critics, and photographers.

Part of the interest of the group lay in a dynamic variety of personalities, economic circumstances, and political views. Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro had merchant family or working-class backgrounds, while Berthe Morisot , Gustave Caillebotte , and Degas were from upper-class roots. Mary Cassatt was American (and a woman) and Alfred Sisley was Anglo-French. This diversity of personalities may be the reason so much creativity arose from the group's collective activities.

The Impressionist Exhibitions

Though not yet united by any particular style, the group shared a general sense of antipathy toward overbearing academic standards of fine art, and decided to join a commercial cooperative, known as the Anonymous Society of Artists, Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, Etcetera. In general, the painters had very limited financial success, and few of their works were accepted for the salon exhibitions in Paris, so the company was important in establishing their financial solvency and creative independence. In 1874, they held the first of a series of exhibitions in the studio of photographer Felix Nadar . It was not until the third exhibition in 1877 that they began to call themselves The Impressionists. While their first exhibition received limited public attention, and most of the eight exhibitions they held actually cost money rather than earning money for the group, their later shows attracted vast audiences, with attendances running well into the thousands. Despite this attention, most members of the group sold very few works, and some of them remained incredibly poor throughout this period.

The Term "Impressionism"

The movement gained its name after the French critic Louis Leroy, whose hostile review of the first major Impressionist exhibition of 1874, seized on the title of Claude Monet's painting Impression, Sunrise (1873). Leroy accused the group of painting nothing but impressions. The Impressionists embraced the moniker, though in later decades they also referred to themselves as the "Independents," referring to the subversive principles of the Société des Artistes Indépendants, formed in 1884 by Impressionist painters who wanted to detach themselves from academic artistic conventions. Although the styles practiced by the Impressionists varied considerably (and in fact not all of the artists would accept Leroy's title) they were bound together by a common interest in the representation of visual perception, based in fleeting optical impressions, and the focus on ephemeral moments of modern life.

The Development of Photography

Impressionism was indebted to the science of photography. The origins of this medium are complex, spanning across nations, but one key event was the French inventor Louis Daguerre's unveiling of the Daguerreotype, in Paris in 1839. Daguerre had developed a technology by which images of the world could be transferred onto a copper sheet treated with silver which reacted to light. This allowed for a direct imprint of reality to be recorded on a two-dimensional surface, a process which revolutionized the ability to visually record the world and their own lives. By 1849, 100,000 Parisians per year were having their photos taken.

The influence of photography on Impressionism was perhaps twofold. On the one hand, it revolutionized perceptions of what was worthy of visual recreation. Academic painting in France had traditionally focused on mythical and historical subject-matter, and portraiture of national leaders and heroes. But photography made it possible for all kinds of people, scenes, buildings, landscapes, to be preserved in pictorial form. This, in turn, altered some painters' sense of who and what was deserving of their attention; the café scenes, side streets, and bustling squares of Impressionist paintings reflect not only a newly vibrant urban realm, but a newfound sense that this world was worth recording.

On the other hand, photography taught painters the art of spontaneous composition, and the related sense that a picture could capture a moment in time as well as a location in space. A work such as Degas's Place de la Concorde is not so much a painting of a public square in Paris as a painting of that square, and of the people and animals that happened to be crossing over it, at a particular point in time. The carefully haphazard arrangement of bodies in motion in this and many other Impressionist paintings could only have been learned via engagement with a technology that had the capacity to freeze and visually convey a millisecond of time. There was a less pronounced sense of what the world might look like in this temporally specific condition prior to the science of photographic reproduction.

Impressionism: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Painting outdoors: claude monet.

Claude Monet is perhaps the most celebrated of the Impressionists. He was renowned for his mastery of natural light and painted at many different times of day in an attempt to capture changing conditions. He tended to create spontaneous impressions of his subjects, using very soft brushstrokes and unmixed colors to generate a subtle sense of vibration, as if nature itself were alive on the canvas. He did not wait for paint to dry before applying successive layers; this "wet on wet" technique produced softer edges and blurred boundaries that suggested three-dimensional planes rather than depicting them realistically.

Monet's technique of painting outdoors, known as plein air painting, was practiced widely among the Impressionists. Inherited from the landscape painters of the Barbizon School , this approach led to innovations in the representation of sunlight and the passage of time, two central motifs of Impressionist painting. While Monet is seen as most central to the tradition of plein air painting, Berthe Morisot , Camille Pissarro , John Singer Sargent , Alfred Sisley and many others also painted outside, lucidly portraying the transience of the natural world.

Impressionist Bodies: Degas, Renoir, and Cassatt

Other Impressionists, like Edgar Degas, were less interested in painting outdoors, and rejected the idea that painting should be a spontaneous act. Considered a highly skilled draftsman and portraitist, Degas preferred indoor scenes of modern life: people sitting in cafés, musicians in an orchestra pit, ballet dancers performing mundane tasks at rehearsal. He also tended to delineate his forms with greater clarity than Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, using harder lines and thicker brushstrokes.

Other artists, such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Berthe Morisot, and Mary Cassatt, also focused on the human form, and on the psychology of the individual sitter or protagonist. Renoir, known for his vibrant, saturated colors, depicted the daily activities of characters from his neighborhood of Montmartre, in particular the social pastimes of Parisian society. While Renoir, like Morisot and Cassatt, also painted outdoors, he emphasized the physiognomy and emotional qualities of his subjects rather than the atmospheric conditions of the scene, using light and loose brushwork to highlight the human form.

The Women of Impressionism

Whereas the male Impressionists painted figures mainly within the public setting of the city, Berthe Morisot concentrated on the private lives of women in late-19 th -century society. The first woman to exhibit with the Impressionists, she created rich compositions that highlight the domestic, highly personal sphere of feminine society, often emphasizing the maternal bond between mother and child, as in The Cradle (1872). Together with Mary Cassatt , Eva Gonzalès , and Marie Bracquemond , she is considered one of the four central female figures of the Impressionist movement.

Cassatt was an American painter who moved to Paris in 1866 and began exhibiting with the Impressionists in 1879. She depicted the private sphere of the home but also represented woman in the public spaces of the newly modernized city, as in her masterwork At the Opera (1879). Her paintings feature a number of innovations, including the flattening of three-dimensional space and the application of bright, even garish colors in her paintings, both of which heralded later developments in modern art .

Impressionist Cityscapes

Since the movement was deeply embedded within Parisian society, Impressionism was greatly influenced by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann's renovation of the city in the 1860s. The urban project, also referred to as "Haussmannization," sought to modernize the city and largely centered in the construction of wide boulevards which became hubs of public social activity. This reconstruction of the city also led to the rise of the idea of the flâneur : the idler or lounger who roams the public spaces of the city, observing life while remaining detached from the crowd. In many Impressionist paintings, the detachment of the flâneur is closely associated with modernity and the estrangement of the individual within the metropolis.

These themes of urbanity are depicted in the work of Gustave Caillebotte , a later proponent of the Impressionist movement, who focused on panoramic views of the city and the psychology of its citizens. Although more realistic in style than other Impressionists, Caillebotte's images, such as Paris, Rainy Day (1877), express the artist's reaction to the changing nature of society, showing a flâneur in his characteristic black coat and top hat strolling through the open space of the boulevard while gazing at passersby. Other Impressionists depicted the fleeting qualities of movement and light within the metropolis, as in Monet's Boulevard des Capucines (1873) and Pissarro's The Boulevard Montmarte, Afternoon (1897). Similarly, these works emphasize the geometrical arrangement of public space through the careful delineation of buildings, trees, and streets. By applying crude brushstrokes and impressionistic streaks of color, the Impressionists evoked the rapid tempo of modern life as a central facet of late-19 th -century urban society.

Later Developments - After Impressionism

Although the Impressionists proved to be a diverse group, they came together regularly to discuss their work and exhibit. The group collaborated on eight exhibitions between 1874 and 1886, but throughout this period they were slowly unravelling as a collective. Many felt they had mastered the early, experimental styles that had won them attention, and wanted to move on to explore other avenues of creativity. Others, anxious about the continued commercial failure of their work, changed course stylistically in the hopes of attracting better sales or patronage.

The Triumph of Impressionism

The ultimate acceptance of the Impressionist movement is largely the achievement of Paul Durand-Ruel, a French art dealer who lived in London. Monet met Durand-Ruel in 1871 and the gallerist purchased Impressionist works and exhibited them in London for many years. Sales were meager, but starting in the late 1880s, he started showing Impressionist works in the United States, with growing success. In the next few years, having exhibited in New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago, Durand-Ruel was able to entice an audience of American buyers who bought more Impressionist works than were ever sold in France. Prices for Impressionist works skyrocketed, to the point that Monet became a millionaire. Moreover, Impressionism came close to becoming an academic orthodoxy, so much so that a whole group of American painters descended on Monet's residence in Giverny to learn from the leader of the group.

Cezanne and the Movement to Post-Impressionism

Meanwhile, the lessons of the style were taken up by a new generation. If Manet bridged the gap between Realism and Impressionism, then Paul Cézanne was the artist who bridged the gap between Impressionism and Post-Impressionism . Cézanne learned much from Impressionist technique, but he evolved a more deliberative style of paint handling, and, toward the end of his life, paid closer attention to the structure of the forms that his broad, repetitive brushstrokes depicted. As he once put it, he wished to "redo Poussin after nature and make Impressionism something solid and durable like the Old Masters ." Cézanne wished to break down objects into their basic geometric constituents and depict their essential building blocks. These experiments would ultimately prove highly influential for the development of Cubism by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque .

The Schools and Painters of Post-Impressionism

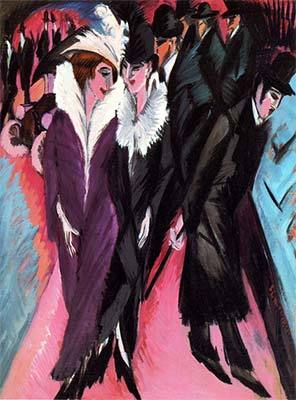

Such was the influence of Impressionism that its younger followers splintered off in a range of directions, forming a whole series of often short-lived groupings and schools. Underlying the development of Post-Impressionism, however, there was perhaps an essential split. On the one hand there were painters and schools who focused on the use of color and brushstroke to represent the mental and emotional life of the painter rather than the pure optical impressions conveyed by pioneers such as Monet. On the other hand, there were those who tried to formalize and refine the optical techniques underlying early Impressionist style.

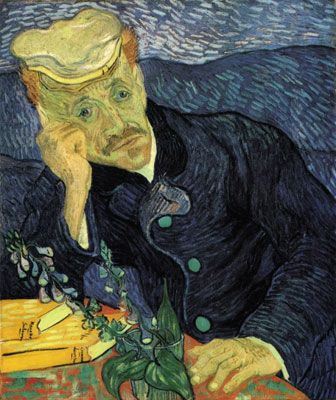

In the first camp are groups such as the Cloisonnists , Synthetists , and Nabis , as well as individual painters whose style was never fully tied down to a particular grouping, perhaps most significantly Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh . Cloisonnism emerged in the late 1880s, and its early advances are often credited to the painters Émile Bernard and Louis Anquetin. Their work from this period uses large areas of vibrant color separated by thick dark outlines, making the different color-blocks reminiscent of the individual panels or "cloisonnes" of medieval stained-glass windows. Both painters spent time with Van Gogh, and also with the so-called Pont-Aven school of painters in rural Brittany, whose members included Paul Sérusier and, for a time, Paul Gauguin. Serusier, Gauguin, Bernard, and Anquetin are also associated with the style of Synthetism, whose techniques and origins are near-identical to Cloisonnism, except that Synthetism is less associated with the thick outlines of Cloisonnist works.

Amongst the most iconic works associated with the Cloisonnist-Synthetist style are Gauguin's Vision After The Sermon (1888) and Sérusier's The Talisman (1888), the latter of which became a lodestar for emergence of the Nabi group, whose works combined the bright, emotive block-colors of Cloisonnism with a new depth of religious and psychological symbolism. At this point, the story of Post-Impressionism starts to intersect with those of other late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century styles such as Symbolism and Expressionism .

At the more sober, scientifically inflected end of responses to Impressionism were those of the artists associated with Pointillism , including Georges Seurat and Paul Signac . As the critic Peter H. Feist notes, these artists were heavily invested in advances in optics during the late nineteenth century, in particular the discovery - also important to the Impressionists - that "colours reached the eye in the form of light of differing wavelengths, and were mixed in the eye to establish the colour that corresponded to the object seen". Therefore, "[i]f a painter juxtaposed tiny dots of unmixed primary colours in the right way, the eye would perceive them as the desired colour tone when looking from a certain distance; and that tone would appear lighter than if it had been mixed in the conventional way, on the palette or the canvas." The most famous work of Pointillism is Seurat's A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (1884-86). Van Gogh's work, with its prominent and hypnotically repetitive brushwork, can in a sense be seen to synthesize the pronounced stylistic qualities of Pointillism and the intense emotive appeal of the Cloisonnist-Synthetist approach.

Impressionism Across the World

Even as Impressionism in France was being overtaken by the advances of the Post-Impressionists, its legacy was travelling across continents. Amongst the most famous of the international Impressionist groupings was the American Impressionist movement , associated not just with Cassatt but with painters such as William Merritt Chase , who applied Impressionist techniques to the landscapes and bourgeois, cosmopolitan milieu of late-nineteenth-century US society; Childe Hassam , famous for his vivid coastal and city scenes; and Maurice Prendergast , who forged a distinctive North-American Post-Impressionist style. Other notable schools of Impressionism in the Anglophone world include the Australian Impressionist school, associated with the work of Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, amongst others, and with the dusty color palettes of its Antipodean climate and terrain.

Particularly significant was the British Impressionist movement of the late-nineteenth century. James Abbott McNeill Whistler , an American expatriate in London, pioneered a loose, liquid style of painting which, in his famous Nocturne series, brilliantly conveyed the gloom and glamor of nightfall on the River Thames. Philip Wilson Steer, meanwhile, became associated with the Impressionist seascape, in particular with works focusing on the landscapes of Cornwall and the South-west of England, while the Scot William McTaggart produced stormier marine scenes, redolent of the wilder coastal landscapes of his home country. Other important Impressionist schools emerged all over Europe, notably in Germany, where Max Liebermann was one of the leading figures of the movement, and also in Holland, Belgium, and Denmark.

The Twentieth Century

Even after the demise of the Post-Impressionist schools, many artists continued to look to Impressionism. For example, although the movement is not generally considered to have had a powerful impact on Abstract Expressionism , one can trace important similarities in its artists' works. Philip Guston was once described as a latter-day "American Impressionist," and the surface qualities, suggestions of light, and "all-over" treatment of form in Jackson Pollock's work, all point to the work of Claude Monet .

The 1960s movement of Op Art is often considered a radical development on the underlying logic of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, with its emphasis on the so-called "Responsive Eye" (a term coined for the title of a famous 1964 Op Art show in New York). Just as the Impressionists had stressed the difference between how color is perceived by the eye and how it is processed by the brain, Op Artists such as Bridget Riley , an avowed follower of George Seurat, based her oeuvre of visually dazzling abstract paintings on the premise that static forms can be made to seem as if in motion based on certain arrangements of line, color, and shape.

Impressionism in Music and Literature

It is also important to remember that, while Impressionism was a movement of the visual arts, it responded to, and helped to influence, a range of other media and genres. These included music - as in the dreamy, romantic work of Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel - and, most importantly, literary prose. The French writer Émile Zola was not only an impassioned defender of the Impressionist painters but brought a representative impulse very similar to Impressionism to his writing, trying to recreate the complexity of human perception and sensation through his prose. Indeed, his novels were produced across a period of time that coincides almost exactly with the lifespan of the Impressionist movement.

Whereas the Impressionist sought to convey the visual appearance of a particular scene at a particular time, the writing style which Zola developed, known as Naturalism, sought to convey the way in which the world appeared mentally and emotionally to a particular individual. In his 1886 book The Masterpiece , Zola even narrated the struggle of the Impressionist movement in allegorical form. The novel tells the story of a young artist based in Paris struggling for recognition and acceptance of a bold new style, but who falls foul of poverty and disinterest. The story is told in a style that transposes the visual logic of Impressionism into the world of subjective perception, thought, and feeling.

Useful Resources on Impressionism

- Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society Our Pick By Robert L. Herbert

- The Great Book of French Impressionism By Diane Kelder

- Impressionism A&I By James Henry Rubin

- Impressionism By Ingo F. Walther

- Art and Culture: Critical Essays By Clement Greenberg / Includes Essays on Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir

- Impressionism By Peter H. Feist

- Whistler By Frances Spalding

- Impressionism: 50 Paintings You Should Know By Ines Janet Engelmann

- The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity Our Pick By Anthea Callen

- Impressionist Art and Paintings

- The National Gallery: Guide to Impressionism

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Impressionism: Art and Modernity Our Pick

- 'Impressionism' at the de Young By Kenneth Baker / The San Francisco Chronicle / May 21, 2010

- Suburban Pastoral By Andrew Motion / The Guardian / February 23, 2007

- A Decade That Remade the World in Painting Our Pick By Michael Kimmelman / The New York Times / September 25, 1994

- 3 Artists Who Left A Fainter Impression Our Pick By Alan Riding / The New York Times / October 28, 1993

- BBC Documentary: The Impressionists Our Pick

- The National Gallery: Corot to Monet

Similar Art

Portrait of Doctor Gachet (1890)

Street, Berlin (1913)

Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) (1950)

Related artists.

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by Justin Wolf

Edited and revised, with Summary and Accomplishments added by Greg Thomas

Plus Page written by Greg Thomas

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

Impressionism: art and modernity.

Garden at Sainte-Adresse

Claude Monet

Porte de la Reine at Aigues-Mortes

Jean-Frédéric Bazille

La Grenouillère

The Bridge at Villeneuve-la-Garenne

Alfred Sisley

Edouard Manet

Madame Georges Charpentier (Marguerite-Louise Lemonnier, 1848–1904) and Her Children, Georgette-Berthe (1872–1945) and Paul-Emile-Charles (1875–1895)

Auguste Renoir

The Monet Family in Their Garden at Argenteuil

The Dance Class

Edgar Degas

Mademoiselle Bécat at the Café des Ambassadeurs, Paris

Côte des Grouettes, near Pontoise

Camille Pissarro

Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Etruscan Gallery

Allée of Chestnut Trees

Young Woman Seated on a Sofa

Berthe Morisot

Two Young Girls at the Piano

Dancers in the Rehearsal Room with a Double Bass

Young Girl Bathing

Young Woman Knitting

The Garden of the Tuileries on a Spring Morning

Margaret Samu Institute of Fine Arts, New York University

October 2004

In 1874, a group of artists called the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Printmakers, etc. organized an exhibition in Paris that launched the movement called Impressionism. Its founding members included Claude Monet , Edgar Degas , and Camille Pissarro, among others. The group was unified only by its independence from the official annual Salon , for which a jury of artists from the Académie des Beaux-Arts selected artworks and awarded medals. The independent artists, despite their diverse approaches to painting, appeared to contemporaries as a group. While conservative critics panned their work for its unfinished, sketchlike appearance, more progressive writers praised it for its depiction of modern life. Edmond Duranty, for example, in his 1876 essay La Nouvelle Peinture (The New Painting), wrote of their depiction of contemporary subject matter in a suitably innovative style as a revolution in painting. The exhibiting collective avoided choosing a title that would imply a unified movement or school, although some of them subsequently adopted the name by which they would eventually be known, the Impressionists. Their work is recognized today for its modernity, embodied in its rejection of established styles, its incorporation of new technology and ideas, and its depiction of modern life.

Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise (Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris) exhibited in 1874, gave the Impressionist movement its name when the critic Louis Leroy accused it of being a sketch or “impression,” not a finished painting. It demonstrates the techniques many of the independent artists adopted: short, broken brushstrokes that barely convey forms, pure unblended colors, and an emphasis on the effects of light. Rather than neutral white, grays, and blacks, Impressionists often rendered shadows and highlights in color. The artists’ loose brushwork gives an effect of spontaneity and effortlessness that masks their often carefully constructed compositions, such as in Alfred Sisley’s 1878 Allée of Chestnut Trees ( 1975.1.211 ). This seemingly casual style became widely accepted, even in the official Salon, as the new language with which to depict modern life.

In addition to their radical technique, the bright colors of Impressionist canvases were shocking for eyes accustomed to the more sober colors of academic painting. Many of the independent artists chose not to apply the thick golden varnish that painters customarily used to tone down their works. The paints themselves were more vivid as well. The nineteenth century saw the development of synthetic pigments for artists’ paints, providing vibrant shades of blue, green, and yellow that painters had never used before. Édouard Manet’s 1874 Boating ( 29.100.115 ), for example, features an expanse of the new cerulean blue and synthetic ultramarine. Depicted in a radically cropped, Japanese-inspired composition , the fashionable boater and his companion embody modernity in their form, their subject matter, and the very materials used to paint them.

Such images of suburban and rural leisure outside of Paris were a popular subject for the Impressionists, notably Monet and Auguste Renoir . Several of them lived in the country for part or all of the year. New railway lines radiating out from the city made travel so convenient that Parisians virtually flooded into the countryside every weekend. While some of the Impressionists, such as Pissarro, focused on the daily life of local villagers in Pontoise, most preferred to depict the vacationers’ rural pastimes. The boating and bathing establishments that flourished in these regions became favorite motifs. In his 1869 La Grenouillère ( 29.100.112 ), for example, Monet’s characteristically loose painting style complements the leisure activities he portrays. Landscapes , which figure prominently in Impressionist art, were also brought up to date with innovative compositions, light effects, and use of color. Monet in particular emphasized the modernization of the landscape by including railways and factories, signs of encroaching industrialization that would have seemed inappropriate to the Barbizon artists of the previous generation.

Perhaps the prime site of modernity in the late nineteenth century was the city of Paris itself, renovated between 1853 and 1870 under Emperor Napoleon III. His prefect, Baron Haussmann, laid the plans, tearing down old buildings to create more open space for a cleaner, safer city. Also contributing to its new look was the Siege of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71), which required reconstructing the parts of the city that had been destroyed. Impressionists such as Pissarro and Gustave Caillebotte enthusiastically painted the renovated city, employing their new style to depict its wide boulevards, public gardens, and grand buildings. While some focused on the cityscapes, others turned their sights to the city’s inhabitants. The Paris population explosion after the Franco-Prussian War gave them a tremendous amount of material for their scenes of urban life. Characteristic of these scenes was the mixing of social classes that took place in public settings. Degas and Caillebotte focused on working people, including singers and dancers , as well as workmen. Others, including Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt , depicted the privileged classes. The Impressionists also painted new forms of leisure, including theatrical entertainment (such as Cassatt’s 1878 In the Loge [Museum of Fine Arts, Boston]), cafés, popular concerts, and dances. Taking an approach similar to Naturalist writers such as Émile Zola, the painters of urban scenes depicted fleeting yet typical moments in the lives of characters they observed. Caillebotte’s 1877 Paris Street, Rainy Day (Art Institute, Chicago) exemplifies how these artists abandoned sentimental depictions and explicit narratives, adopting instead a detached, objective view that merely suggests what is going on.

The independent collective had a fluid membership over the course of the eight exhibitions it organized between 1874 and 1886, with the number of participating artists ranging from nine to thirty. Pissarro, the eldest, was the only artist who exhibited in all eight shows, while Morisot participated in seven. Ideas for an independent exhibition had been discussed as early as 1867, but the Franco-Prussian War intervened. The painter Frédéric Bazille, who had been leading the efforts, was killed in the war. Subsequent exhibitions were headed by different artists. Philosophical and political differences among the artists led to heated disputes and fractures, causing fluctuations in the contributors. The exhibitions even included the works of more conservative artists who simply refused to submit their work to the Salon jury. Also participating in the independent exhibitions were Paul Cézanne and Paul Gauguin , whose later styles grew out of their early work with the Impressionists.

The last of the independent exhibitions in 1886 also saw the beginning of a new phase in avant-garde painting. By this time, few of the participants were working in a recognizably Impressionist manner. Most of the core members were developing new, individual styles that caused ruptures in the group’s tenuous unity. Pissarro promoted the participation of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, in addition to adopting their new technique based on points of pure color, known as Neo-Impressionism . The young Gauguin was making forays into Primitivism. The nascent Symbolist Odilon Redon also contributed, though his style was unlike that of any other participant. Because of the group’s stylistic and philosophical fragmentation, and because of the need for assured income, some of the core members such as Monet and Renoir exhibited in venues where their works were more likely to sell.

Its many facets and varied participants make the Impressionist movement difficult to define. Indeed, its life seems as fleeting as the light effects it sought to capture. Even so, Impressionism was a movement of enduring consequence, as its embrace of modernity made it the springboard for later avant-garde art in Europe.

Samu, Margaret. “Impressionism: Art and Modernity.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/imml/hd_imml.htm (October 2004)

Further Reading

Bomford, David, et al. Art in the Making: Impressionism . Exhibition catalogue.. New Haven and London: National Gallery, 1990.

Herbert, Robert L. Impressionism: Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

House, John. Monet: Nature into Art . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

Moffett, Charles S., et al. The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886 . San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986.

Nochlin, Linda, ed. Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, 1874–1904: Sources and Documents . Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1966.

Rewald, John. The History of Impressionism . Rev. and enl. ed. . New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1961.

Tinterow, Gary, and Henri Loyrette. Origins of Impressionism . Exhibition catalogue.. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994. See on MetPublications

Related Essays

- Claude Monet (1840–1926)

- Edgar Degas (1834–1917): Painting and Drawing

- Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

- Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844–1926)

- African Influences in Modern Art

- American Impressionism

- American Scenes of Everyday Life, 1840–1910

- Americans in Paris, 1860–1900

- Auguste Renoir (1841–1919)

- Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

- Edgar Degas (1834–1917): Bronze Sculpture

- Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Neo-Impressionism

- Henri Matisse (1869–1954)

- Nineteenth-Century French Realism

- Orientalism in Nineteenth-Century Art

- Paul Gauguin (1848–1903)

- France, 1800–1900 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1800–1900 A.D.

- The United States and Canada, 1800–1900 A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- Academic Painting

- Arboreal Landscape

- Architecture

- Barbizon School

- French Literature / Poetry

- Great Britain and Ireland

- Impressionism

- Literature / Poetry

- Neo-Impressionism

- Oil on Canvas

- Post-Impressionism

- Primitivism

- Women Artists

Artist or Maker

- Bazille, Jean-Frédéric

- Cassatt, Mary

- Cézanne, Paul

- Degas, Edgar

- Gauguin, Paul

- Manet, Édouard

- Monet, Claude

- Morisot, Berthe

- Pissarro, Camille

- Redon, Odilon

- Renoir, Auguste

- Sisley, Alfred

- Sorolla y Bastida, Joaquin

Online Features

- The Artist Project: “George Condo on Claude Monet’s The Path through the Irises “

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

The artists who became the Impressionists

Beginnings of impressionism, impressionist exhibitions and influence.

- What is Paul Cézanne famous for?

- How was Paul Cézanne educated?

Impressionism

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Humanities LibreTexts - Impressionism

- Whatcom Community College Pressbooks - Art 205 "Western Art from 18th to Mid 20th Century" - Impressionism and Post-Impressionism

- Open Library Publishing Platform - Origins of Contemporary Art, Design, and Interiors - Impressionism

- Guggenheim - Impressionism

- The Met - Impressionism: Art and Modernity

- The Art Story - Impressionism

- National Gallery of Art, London - Impressionism

- LOUIS Pressbooks - Exploring the Arts - Music of the 20th Century

- World History Encyclopedia - Impressionism

- Impressionism - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- impressionism - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Impressionism , a broad term used to describe the work produced in the late 19th century, especially between about 1867 and 1886, by a group of artists who shared a set of related approaches and techniques. The founding Impressionist artists included Claude Monet , Pierre-Auguste Renoir , Camille Pissarro , Alfred Sisley , Edgar Degas , and Berthe Morisot . Other significant Impressionists, including Gustave Caillebotte , Mary Cassatt , Paul Gauguin , and Georges Seurat , joined the group later. Although these artists had stylistic differences, they had a shared interest in accurately and objectively recording contemporary life and the transient effects of light and color. These concerns may seem fairly banal in the 21st century, but in the 19th century—when historical, biblical, and allegorical subjects were favored, and painting was expected to have a high finish—they were revolutionary. The Impressionists helped liberate art from a focus on subject toward personal expression and the study of creating.

The artists who would later be called the Impressionists met in Paris in the early 1860s. Pissarro, Monet, and the artists Paul Cézanne and Armand Guillaumin became acquainted while they were studying at the Académie Suisse, an informal art school in Paris founded by Martin François Suisse. In 1862 Monet joined the atelier of the academician Charles Gleyre and became fast friends with fellow students Sisley, Renoir, and the artist Frédéric Bazille . The two groups met frequently, discussing their shared dissatisfaction with academic teaching’s emphasis on depicting historical or mythological subject matter with literary or anecdotal overtones. They also rejected the conventional imaginative or idealizing treatments of academic painting.

Most of these artists were only in their 20s, except for Pissarro, who was in his 30s, and were just forming their styles. Monet was especially interested in the innovative painters Eugène Boudin and Johan Barthold Jongkind , who depicted fleeting effects of sea and sky by means of highly colored and texturally varied methods of paint application. With his Gleyre studio friends, Monet adopted Boudin’s practice of painting entirely out-of-doors while looking at the actual scene, instead of finishing a painting from sketches in the studio, as was the conventional practice. When Gleyre closed his studio in 1864, Monet, Renoir, Sisley, and Bazille moved temporarily to the forest of Fontainebleau , where they devoted themselves to painting directly from nature. The Fontainebleau forest had earlier attracted other artists, among them Théodore Rousseau and Jean-François Millet , who insisted that art represent the reality of everyday life.

The Gleyre studio and the Académie Suisse students were all inspired by the established artist Édouard Manet , who himself had followed the lead of Realist painter Gustave Courbet in objectively painting modern subjects. In Manet’s art, the traditional subject matter was downgraded in favor of subjects from the events and circumstances of his own time, and attention was shifted to the artist’s manipulation of color, tone, and texture as ends in themselves. The subject became a vehicle for the artful composition of areas of flat color and deliberate brushstrokes, while perspectival depth was minimized so that the viewer would look at the surface patterns and relationships of the picture rather than at the illusory three-dimensional space it created. Pissarro and the younger artists met Manet as well as Degas about 1866 at the Café Guerbois.

In the late 1860s Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and others began painting landscapes and river scenes in which they tried to dispassionately record the colors and forms of objects as they appeared in natural light at a given time. These artists abandoned the traditional landscape palette of muted greens, browns, and grays and instead painted in a lighter, sunnier, more brilliant key. They began by painting the play of light upon water and the reflected colors of its ripples, trying to reproduce the manifold and animated effects of sunlight and shadow and of direct and reflected light that they observed. In their efforts to reproduce immediate visual impressions as registered on the retina, they abandoned the use of grays and blacks in shadows as inaccurate and used complementary colors instead. More important, they learned to build up objects out of discrete flecks and dabs of pure harmonizing or contrasting color, thus evoking the broken-hued brilliance and the variations of hue produced by sunlight and its reflections. Forms in their pictures lost their clear outlines and became dematerialized, shimmering and vibrating in a re-creation of actual outdoor conditions. And finally, traditional formal compositions were abandoned in favor of a more casual and less contrived disposition of objects within the picture frame . The Impressionists extended their new techniques to depict landscapes, trees, houses, and even urban street scenes and railroad stations.

Throughout the 1860s most of these avant-garde artists had work accepted into the Salon , the annual state-sponsored public exhibition, but, by the end of the decade, they were being consistently rejected. They came increasingly to recognize the unfairness of the Salon’s jury system as well as the disadvantages relatively small paintings such as their own had at Salon exhibitions. They considered staging an independent exhibition but were interrupted by the Franco-German War (1870–71). Bazille, who had been leading the efforts, was killed in battle. At the end of 1873 talks were renewed and the Société Anonyme Coopérative d’Artistes-Peintres, Sculpteurs, etc., was founded. Its members included Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Pissarro, Degas, and Morisot, another avant-garde artist who was introduced to the group through Manet. The collective aimed to organize exhibitions, sell art, and publish a journal.

The Société Anonyme specifically avoided choosing a name that suggested that they were part of a coherent school. So when the collective organized its first exhibition in 1874, the members invited a patchwork of artists in their network to show. Although Manet chose not to join, some 30 participants accepted the invitation, and the result was an exhibition of various styles and media. Some critics appreciated the group’s effort to break from the establishment but most did not like the art and wrote blistering reviews. Monet’s painting Impression, Sunrise (1872) earned the collective the initially derisive name “Impressionists” from the journalist Louis Leroy writing in the satirical magazine Le Charivari in 1874. The exhibition was a financial failure, and the Société Anonyme was soon dissolved .

In subsequent years, however, several of the artists who founded the Société Anonyme staged seven more exhibitions , between 1876 and 1886. Participation fluctuated, with some artists, including Cézanne and Guillaumin, wavering early on. Disagreements between factions about using the name “Impressionism” and its implication of stylistic unity occurred during the planning of each show, resulting in a few particularly bitter abstentions during the last three exhibitions. During the exhibition years, participants continued to develop their own personal and individual styles, but they all were united in their work by the principles of freedom of technique, a personal rather than a conventional approach to subject matter, and the truthful reproduction of nature.

The Impressionist group had already begun to dissolve by the early 1880s as each painter increasingly pursued his or her own aesthetic interests and principles. In its short existence, however, it had accomplished a revolution in the history of art, providing a technical starting point for Cézanne, Gauguin, Georges Seurat , and Vincent van Gogh and the Post-Impressionist movement. Impressionism also opened a path for subsequent artists of Western painting to diverge from traditional techniques and approaches to subject matter.

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

Impressionism & Post-Impressionism

Published by Viljo Niemi Modified over 6 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Impressionism & Post-Impressionism"— Presentation transcript:

SEVENTH GRADE VISUAL ARTS

Impressionism by Phillip Martin.

Impressionism vs. Post-Impressionism

19 th century: Modernism and Impressionism Vocabulary Bourgeois Salon Salon des Refusés Flanneur Courtesan La Tache Impasto En pleine aire Haussmanization.

Impressionism Commitment to represent modern life Make a break from traditional art, avant garde Make it expressive, markings of how it was made Painted.

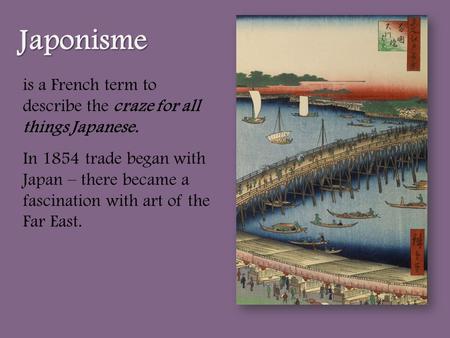

Is a French term to describe the craze for all things Japanese. In 1854 trade began with Japan – there became a fascination with art of the Far East. Japonisme.

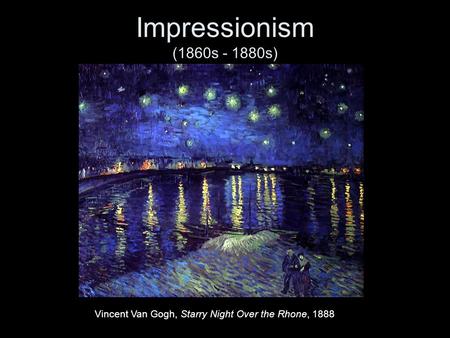

Impressionism (1860s s) Vincent Van Gogh, Starry Night Over the Rhone, 1888.

Impressionist & Post-Impressionist Art FCC 220. Define Impressionism: Date Movement Started E.L.B.O.W. MANET DEGAS MONET CASSATT RENOIR SEURAT VAN GOGH.

Impressionism. Characteristics of Impressionism Luminosity (emitting or reflecting light) The interaction of light and form Example: Light reflecting.

French Impressionism Art History Unit Floral Design.

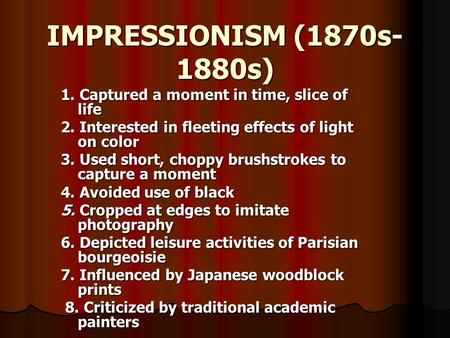

IMPRESSIONISM (1870s- 1880s) 1. Captured a moment in time, slice of life 2. Interested in fleeting effects of light on color 3. Used short, choppy brushstrokes.

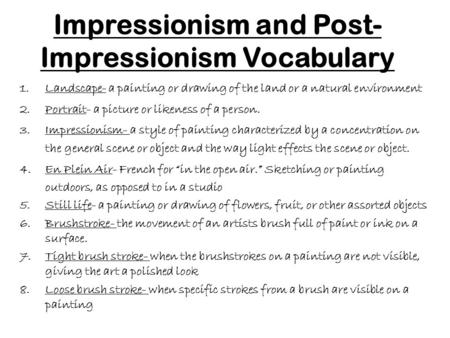

Impressionism and Post- Impressionism Vocabulary 1.Landscape- a painting or drawing of the land or a natural environment 2.Portrait- a picture or likeness.

Impresionism and Post- Impressionism Vocabulary 1.Landscape- a painting or drawing of the land or a natural environment 2.En Plein Air- French for “in.

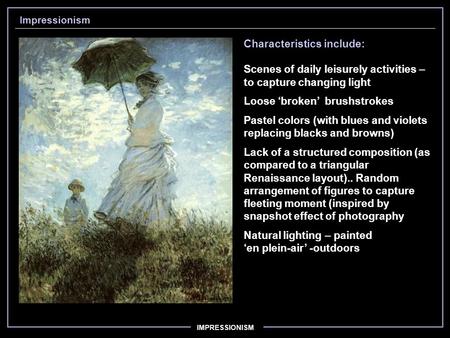

IMPRESSIONISM Impressionism Characteristics include: Scenes of daily leisurely activities – to capture changing light Loose ‘broken’ brushstrokes Pastel.

Impressionism Is an art movement and style of painting that started in France during the 1860s. Impressionism is a light, spontaneous manner of painting.

Chapter Thirteen Examples Impressionism and Post-Impressionism Art timeline images for study and discussion.

History of Painting from Realism to Modernism. Invention of Photography is in 1830 How does this change attitudes to realism? How does photography as.

Impressionism Evolved in France between1860s-1890s Evolved in France between 1860s-1890s.

Impressionist art. 1. Impressionism was an art movement.

L’Impressionisme 19e siècle.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

- Preferences

Impressionism - PowerPoint PPT Presentation

Impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th century art movement that began as a loose association ... impressionism became the birth of modern art. ... – powerpoint ppt presentation.

- Impressionism was a 19th century art movement that began as a loose association of Paris based artists, who began exhibiting their art publicly in the 1860s. The name of the movement is derived from the title of a Claude Monet painting, called Impression, Sunrise

- Visible brushstrokes

- Light Colors

- Emphasis on Light and the changing qualities of it

- Ordinary Subject Matter

- Unusual Visual Angles

- Open Compositions

- Claude Monet Lilly ponds Gardens

- Auguste Renoir People Outdoors

- Edgar Degas Dancers and Theater

- Camille Pissarro Cities and Streets

- Alfred Sisley Rivers and Landscapes

- Advanced Art Impressionism

- Lesson Objectives Students will have a general understanding of the theory and characteristics of the Impressionist style of art and the major artists of the style. Students will be able to analyze light more objectively and learn to paint using the techniques of the impressionist style.

- 1 Students will be shown power point on Impressionism. Create a list of artists, characteristics and techniques of the Impressionist style

- 2 Students will find examples of Impressionist style of painting from the internet at (ARTCHIVE). They will print 1 example of the artist of their choice and attempt to accurately reproduce the colors and brush strokes of the painting. Size will be 6x8.

- 3 Students will produce an original painting executed in the Impressionist style. Size will be 11x14.

- 4 Students will be given a test on characteristics, techniques, and artist work identification.