Dirk Riehle's Comments on Science and Academia

Nach dem Antrag ist vor dem Antrag (after the grant proposal is before the grant proposal)

The role of a literature review in grant proposals

Christmas is coming up, so what’s a professor got to do? Hide from the family and work on grant proposals, naturally. Right now I’m upset about the misunderstanding of the role that literature reviews play in grant proposals (by way of reviewer comments).

Reviewing literature is just a general activity, but one that can serve many purposes. Depending on the purpose, different review techniques are more or less suited to help achieve that purpose. I’ll focus on the two main purposes, related work and theory building.

Related work

Here, you want to show how your work is different from other people’s work. This is common in both research papers (“related work” section) and grant proposals (“state of the art” section). You use a compare-and-contrast style to show how your work is different and novel, justifying publication or funding.

You should be structured in your approach, but general human intelligence and domain knowledge are sufficient for the task. You are making a qualitative argument why your work should be accepted.

Theory building

Here, you are trying to generate novel insight from the literature. The goal is to build the (often initial version) of a theory that you intend to evaluate. The idea is that from all those research papers you are reading, significant new insight can be had, if you only correlated the information right.

You can’t wing this. You need a structured approach. In computer science, for example, we often use Kitchenham’s (2004) approach to systematic literature reviews. My group usually uses thematic coding (Braun & Clarke, 2012) in the analysis of the identified literature to create a first version of the theory under development.

Grant proposals

When it comes to grant proposals, you write the related work / state of the art section as part of the grant proposal, before submission.

A theory-building systematic literature review is what you propose to do, but don’t actually carry out before grant proposal submission. It is a core piece of the proposed research. It bugs me if reviewers ask that we please finish work package 1, the initial theory building using a systematic literature review, before we even submit the grant proposal.

All I want for Christmas is that reviewers start doing justice by systematic literature reviews…

Kitchenham, B. (2004). Procedures for performing systematic reviews. Keele, UK, Keele University , 33 (2004), 1-26.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association.

Subscription

Type your email…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Share the joy

Share on LinkedIn

Share by email

Share on X (Twitter)

Share on WhatsApp

Research projects

This site uses cookies. By continuing to use this website, you agree to their use. To find out more, including how to control cookies, see here: Cookie Policy .

Grant Proposals (or Give me the money!)

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you write and revise grant proposals for research funding in all academic disciplines (sciences, social sciences, humanities, and the arts). It’s targeted primarily to graduate students and faculty, although it will also be helpful to undergraduate students who are seeking funding for research (e.g. for a senior thesis).

The grant writing process

A grant proposal or application is a document or set of documents that is submitted to an organization with the explicit intent of securing funding for a research project. Grant writing varies widely across the disciplines, and research intended for epistemological purposes (philosophy or the arts) rests on very different assumptions than research intended for practical applications (medicine or social policy research). Nonetheless, this handout attempts to provide a general introduction to grant writing across the disciplines.

Before you begin writing your proposal, you need to know what kind of research you will be doing and why. You may have a topic or experiment in mind, but taking the time to define what your ultimate purpose is can be essential to convincing others to fund that project. Although some scholars in the humanities and arts may not have thought about their projects in terms of research design, hypotheses, research questions, or results, reviewers and funding agencies expect you to frame your project in these terms. You may also find that thinking about your project in these terms reveals new aspects of it to you.

Writing successful grant applications is a long process that begins with an idea. Although many people think of grant writing as a linear process (from idea to proposal to award), it is a circular process. Many people start by defining their research question or questions. What knowledge or information will be gained as a direct result of your project? Why is undertaking your research important in a broader sense? You will need to explicitly communicate this purpose to the committee reviewing your application. This is easier when you know what you plan to achieve before you begin the writing process.

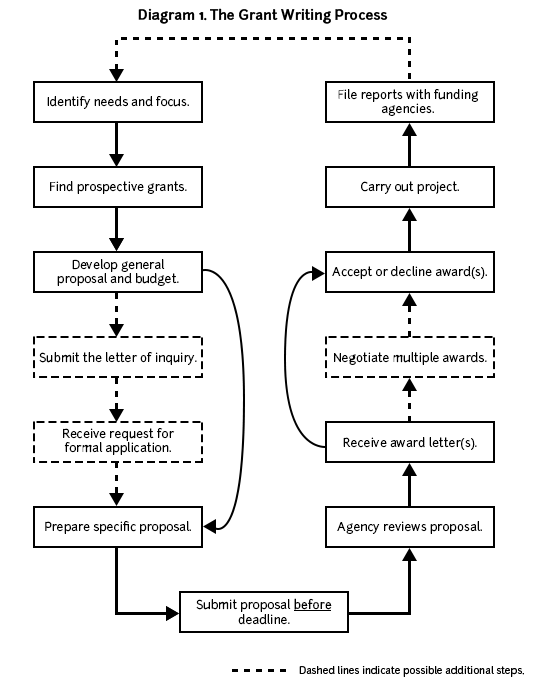

Diagram 1 below provides an overview of the grant writing process and may help you plan your proposal development.

Applicants must write grant proposals, submit them, receive notice of acceptance or rejection, and then revise their proposals. Unsuccessful grant applicants must revise and resubmit their proposals during the next funding cycle. Successful grant applications and the resulting research lead to ideas for further research and new grant proposals.

Cultivating an ongoing, positive relationship with funding agencies may lead to additional grants down the road. Thus, make sure you file progress reports and final reports in a timely and professional manner. Although some successful grant applicants may fear that funding agencies will reject future proposals because they’ve already received “enough” funding, the truth is that money follows money. Individuals or projects awarded grants in the past are more competitive and thus more likely to receive funding in the future.

Some general tips

- Begin early.

- Apply early and often.

- Don’t forget to include a cover letter with your application.

- Answer all questions. (Pre-empt all unstated questions.)

- If rejected, revise your proposal and apply again.

- Give them what they want. Follow the application guidelines exactly.

- Be explicit and specific.

- Be realistic in designing the project.

- Make explicit the connections between your research questions and objectives, your objectives and methods, your methods and results, and your results and dissemination plan.

- Follow the application guidelines exactly. (We have repeated this tip because it is very, very important.)

Before you start writing

Identify your needs and focus.

First, identify your needs. Answering the following questions may help you:

- Are you undertaking preliminary or pilot research in order to develop a full-blown research agenda?

- Are you seeking funding for dissertation research? Pre-dissertation research? Postdoctoral research? Archival research? Experimental research? Fieldwork?

- Are you seeking a stipend so that you can write a dissertation or book? Polish a manuscript?

- Do you want a fellowship in residence at an institution that will offer some programmatic support or other resources to enhance your project?

- Do you want funding for a large research project that will last for several years and involve multiple staff members?

Next, think about the focus of your research/project. Answering the following questions may help you narrow it down:

- What is the topic? Why is this topic important?

- What are the research questions that you’re trying to answer? What relevance do your research questions have?

- What are your hypotheses?

- What are your research methods?

- Why is your research/project important? What is its significance?

- Do you plan on using quantitative methods? Qualitative methods? Both?

- Will you be undertaking experimental research? Clinical research?

Once you have identified your needs and focus, you can begin looking for prospective grants and funding agencies.

Finding prospective grants and funding agencies

Whether your proposal receives funding will rely in large part on whether your purpose and goals closely match the priorities of granting agencies. Locating possible grantors is a time consuming task, but in the long run it will yield the greatest benefits. Even if you have the most appealing research proposal in the world, if you don’t send it to the right institutions, then you’re unlikely to receive funding.

There are many sources of information about granting agencies and grant programs. Most universities and many schools within universities have Offices of Research, whose primary purpose is to support faculty and students in grant-seeking endeavors. These offices usually have libraries or resource centers to help people find prospective grants.

At UNC, the Research at Carolina office coordinates research support.

The Funding Information Portal offers a collection of databases and proposal development guidance.

The UNC School of Medicine and School of Public Health each have their own Office of Research.

Writing your proposal

The majority of grant programs recruit academic reviewers with knowledge of the disciplines and/or program areas of the grant. Thus, when writing your grant proposals, assume that you are addressing a colleague who is knowledgeable in the general area, but who does not necessarily know the details about your research questions.

Remember that most readers are lazy and will not respond well to a poorly organized, poorly written, or confusing proposal. Be sure to give readers what they want. Follow all the guidelines for the particular grant you are applying for. This may require you to reframe your project in a different light or language. Reframing your project to fit a specific grant’s requirements is a legitimate and necessary part of the process unless it will fundamentally change your project’s goals or outcomes.

Final decisions about which proposals are funded often come down to whether the proposal convinces the reviewer that the research project is well planned and feasible and whether the investigators are well qualified to execute it. Throughout the proposal, be as explicit as possible. Predict the questions that the reviewer may have and answer them. Przeworski and Salomon (1995) note that reviewers read with three questions in mind:

- What are we going to learn as a result of the proposed project that we do not know now? (goals, aims, and outcomes)

- Why is it worth knowing? (significance)

- How will we know that the conclusions are valid? (criteria for success) (2)

Be sure to answer these questions in your proposal. Keep in mind that reviewers may not read every word of your proposal. Your reviewer may only read the abstract, the sections on research design and methodology, the vitae, and the budget. Make these sections as clear and straightforward as possible.

The way you write your grant will tell the reviewers a lot about you (Reif-Lehrer 82). From reading your proposal, the reviewers will form an idea of who you are as a scholar, a researcher, and a person. They will decide whether you are creative, logical, analytical, up-to-date in the relevant literature of the field, and, most importantly, capable of executing the proposed project. Allow your discipline and its conventions to determine the general style of your writing, but allow your own voice and personality to come through. Be sure to clarify your project’s theoretical orientation.

Develop a general proposal and budget

Because most proposal writers seek funding from several different agencies or granting programs, it is a good idea to begin by developing a general grant proposal and budget. This general proposal is sometimes called a “white paper.” Your general proposal should explain your project to a general academic audience. Before you submit proposals to different grant programs, you will tailor a specific proposal to their guidelines and priorities.

Organizing your proposal

Although each funding agency will have its own (usually very specific) requirements, there are several elements of a proposal that are fairly standard, and they often come in the following order:

- Introduction (statement of the problem, purpose of research or goals, and significance of research)

Literature review

- Project narrative (methods, procedures, objectives, outcomes or deliverables, evaluation, and dissemination)

- Budget and budget justification

Format the proposal so that it is easy to read. Use headings to break the proposal up into sections. If it is long, include a table of contents with page numbers.

The title page usually includes a brief yet explicit title for the research project, the names of the principal investigator(s), the institutional affiliation of the applicants (the department and university), name and address of the granting agency, project dates, amount of funding requested, and signatures of university personnel authorizing the proposal (when necessary). Most funding agencies have specific requirements for the title page; make sure to follow them.

The abstract provides readers with their first impression of your project. To remind themselves of your proposal, readers may glance at your abstract when making their final recommendations, so it may also serve as their last impression of your project. The abstract should explain the key elements of your research project in the future tense. Most abstracts state: (1) the general purpose, (2) specific goals, (3) research design, (4) methods, and (5) significance (contribution and rationale). Be as explicit as possible in your abstract. Use statements such as, “The objective of this study is to …”

Introduction

The introduction should cover the key elements of your proposal, including a statement of the problem, the purpose of research, research goals or objectives, and significance of the research. The statement of problem should provide a background and rationale for the project and establish the need and relevance of the research. How is your project different from previous research on the same topic? Will you be using new methodologies or covering new theoretical territory? The research goals or objectives should identify the anticipated outcomes of the research and should match up to the needs identified in the statement of problem. List only the principle goal(s) or objective(s) of your research and save sub-objectives for the project narrative.

Many proposals require a literature review. Reviewers want to know whether you’ve done the necessary preliminary research to undertake your project. Literature reviews should be selective and critical, not exhaustive. Reviewers want to see your evaluation of pertinent works. For more information, see our handout on literature reviews .

Project narrative

The project narrative provides the meat of your proposal and may require several subsections. The project narrative should supply all the details of the project, including a detailed statement of problem, research objectives or goals, hypotheses, methods, procedures, outcomes or deliverables, and evaluation and dissemination of the research.

For the project narrative, pre-empt and/or answer all of the reviewers’ questions. Don’t leave them wondering about anything. For example, if you propose to conduct unstructured interviews with open-ended questions, be sure you’ve explained why this methodology is best suited to the specific research questions in your proposal. Or, if you’re using item response theory rather than classical test theory to verify the validity of your survey instrument, explain the advantages of this innovative methodology. Or, if you need to travel to Valdez, Alaska to access historical archives at the Valdez Museum, make it clear what documents you hope to find and why they are relevant to your historical novel on the ’98ers in the Alaskan Gold Rush.

Clearly and explicitly state the connections between your research objectives, research questions, hypotheses, methodologies, and outcomes. As the requirements for a strong project narrative vary widely by discipline, consult a discipline-specific guide to grant writing for some additional advice.

Explain staffing requirements in detail and make sure that staffing makes sense. Be very explicit about the skill sets of the personnel already in place (you will probably include their Curriculum Vitae as part of the proposal). Explain the necessary skill sets and functions of personnel you will recruit. To minimize expenses, phase out personnel who are not relevant to later phases of a project.

The budget spells out project costs and usually consists of a spreadsheet or table with the budget detailed as line items and a budget narrative (also known as a budget justification) that explains the various expenses. Even when proposal guidelines do not specifically mention a narrative, be sure to include a one or two page explanation of the budget. To see a sample budget, turn to Example #1 at the end of this handout.

Consider including an exhaustive budget for your project, even if it exceeds the normal grant size of a particular funding organization. Simply make it clear that you are seeking additional funding from other sources. This technique will make it easier for you to combine awards down the road should you have the good fortune of receiving multiple grants.

Make sure that all budget items meet the funding agency’s requirements. For example, all U.S. government agencies have strict requirements for airline travel. Be sure the cost of the airline travel in your budget meets their requirements. If a line item falls outside an agency’s requirements (e.g. some organizations will not cover equipment purchases or other capital expenses), explain in the budget justification that other grant sources will pay for the item.

Many universities require that indirect costs (overhead) be added to grants that they administer. Check with the appropriate offices to find out what the standard (or required) rates are for overhead. Pass a draft budget by the university officer in charge of grant administration for assistance with indirect costs and costs not directly associated with research (e.g. facilities use charges).

Furthermore, make sure you factor in the estimated taxes applicable for your case. Depending on the categories of expenses and your particular circumstances (whether you are a foreign national, for example), estimated tax rates may differ. You can consult respective departmental staff or university services, as well as professional tax assistants. For information on taxes on scholarships and fellowships, see https://cashier.unc.edu/student-tax-information/scholarships-fellowships/ .

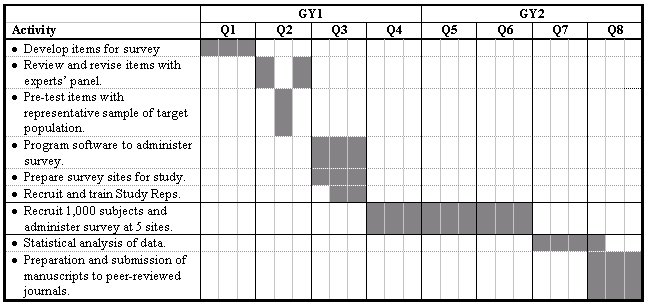

Explain the timeframe for the research project in some detail. When will you begin and complete each step? It may be helpful to reviewers if you present a visual version of your timeline. For less complicated research, a table summarizing the timeline for the project will help reviewers understand and evaluate the planning and feasibility. See Example #2 at the end of this handout.

For multi-year research proposals with numerous procedures and a large staff, a time line diagram can help clarify the feasibility and planning of the study. See Example #3 at the end of this handout.

Revising your proposal

Strong grant proposals take a long time to develop. Start the process early and leave time to get feedback from several readers on different drafts. Seek out a variety of readers, both specialists in your research area and non-specialist colleagues. You may also want to request assistance from knowledgeable readers on specific areas of your proposal. For example, you may want to schedule a meeting with a statistician to help revise your methodology section. Don’t hesitate to seek out specialized assistance from the relevant research offices on your campus. At UNC, the Odum Institute provides a variety of services to graduate students and faculty in the social sciences.

In your revision and editing, ask your readers to give careful consideration to whether you’ve made explicit the connections between your research objectives and methodology. Here are some example questions:

- Have you presented a compelling case?

- Have you made your hypotheses explicit?

- Does your project seem feasible? Is it overly ambitious? Does it have other weaknesses?

- Have you stated the means that grantors can use to evaluate the success of your project after you’ve executed it?

If a granting agency lists particular criteria used for rating and evaluating proposals, be sure to share these with your own reviewers.

Example #1. Sample Budget

| Jet Travel | ||||

| RDU-Kigali (roundtrip) | 1 | $6,100 | $6,100 | |

| Maintenance Allowance | ||||

| Rwanda | 12 months | $1,899 | $22,788 | $22,788 |

| Project Allowance | ||||

| Research Assistant/Translator | 12 months | $400 | $4800 | |

| Transportation within country | ||||

| –Phase 1 | 4 months | $300 | $1,200 | |

| –Phase 2 | 8 months | $1,500 | $12,000 | |

| 12 months | $60 | $720 | ||

| Audio cassette tapes | 200 | $2 | $400 | |

| Photographic and slide film | 20 | $5 | $100 | |

| Laptop Computer | 1 | $2,895 | ||

| NUD*IST 4.0 Software | $373 | |||

| Etc. | ||||

| Total Project Allowance | $35,238 | |||

| Administrative Fee | $100 | |||

| Total | $65,690 | |||

| Sought from other sources | ($15,000) | |||

| Total Grant Request | $50,690 |

Jet travel $6,100 This estimate is based on the commercial high season rate for jet economy travel on Sabena Belgian Airlines. No U.S. carriers fly to Kigali, Rwanda. Sabena has student fare tickets available which will be significantly less expensive (approximately $2,000).

Maintenance allowance $22,788 Based on the Fulbright-Hays Maintenance Allowances published in the grant application guide.

Research assistant/translator $4,800 The research assistant/translator will be a native (and primary) speaker of Kinya-rwanda with at least a four-year university degree. They will accompany the primary investigator during life history interviews to provide assistance in comprehension. In addition, they will provide commentary, explanations, and observations to facilitate the primary investigator’s participant observation. During the first phase of the project in Kigali, the research assistant will work forty hours a week and occasional overtime as needed. During phases two and three in rural Rwanda, the assistant will stay with the investigator overnight in the field when necessary. The salary of $400 per month is based on the average pay rate for individuals with similar qualifications working for international NGO’s in Rwanda.

Transportation within country, phase one $1,200 The primary investigator and research assistant will need regular transportation within Kigali by bus and taxi. The average taxi fare in Kigali is $6-8 and bus fare is $.15. This figure is based on an average of $10 per day in transportation costs during the first project phase.

Transportation within country, phases two and three $12,000 Project personnel will also require regular transportation between rural field sites. If it is not possible to remain overnight, daily trips will be necessary. The average rental rate for a 4×4 vehicle in Rwanda is $130 per day. This estimate is based on an average of $50 per day in transportation costs for the second and third project phases. These costs could be reduced if an arrangement could be made with either a government ministry or international aid agency for transportation assistance.

Email $720 The rate for email service from RwandaTel (the only service provider in Rwanda) is $60 per month. Email access is vital for receiving news reports on Rwanda and the region as well as for staying in contact with dissertation committee members and advisors in the United States.

Audiocassette tapes $400 Audiocassette tapes will be necessary for recording life history interviews, musical performances, community events, story telling, and other pertinent data.

Photographic & slide film $100 Photographic and slide film will be necessary to document visual data such as landscape, environment, marriages, funerals, community events, etc.

Laptop computer $2,895 A laptop computer will be necessary for recording observations, thoughts, and analysis during research project. Price listed is a special offer to UNC students through the Carolina Computing Initiative.

NUD*IST 4.0 software $373.00 NUD*IST, “Nonnumerical, Unstructured Data, Indexing, Searching, and Theorizing,” is necessary for cataloging, indexing, and managing field notes both during and following the field research phase. The program will assist in cataloging themes that emerge during the life history interviews.

Administrative fee $100 Fee set by Fulbright-Hays for the sponsoring institution.

Example #2: Project Timeline in Table Format

| Exploratory Research | Completed |

| Proposal Development | Completed |

| Ph.D. qualifying exams | Completed |

| Research Proposal Defense | Completed |

| Fieldwork in Rwanda | Oct. 1999-Dec. 2000 |

| Data Analysis and Transcription | Jan. 2001-March 2001 |

| Writing of Draft Chapters | March 2001 – Sept. 2001 |

| Revision | Oct. 2001-Feb. 2002 |

| Dissertation Defense | April 2002 |

| Final Approval and Completion | May 2002 |

Example #3: Project Timeline in Chart Format

Some closing advice

Some of us may feel ashamed or embarrassed about asking for money or promoting ourselves. Often, these feelings have more to do with our own insecurities than with problems in the tone or style of our writing. If you’re having trouble because of these types of hang-ups, the most important thing to keep in mind is that it never hurts to ask. If you never ask for the money, they’ll never give you the money. Besides, the worst thing they can do is say no.

UNC resources for proposal writing

Research at Carolina http://research.unc.edu

The Odum Institute for Research in the Social Sciences https://odum.unc.edu/

UNC Medical School Office of Research https://www.med.unc.edu/oor

UNC School of Public Health Office of Research http://www.sph.unc.edu/research/

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Holloway, Brian R. 2003. Proposal Writing Across the Disciplines. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Levine, S. Joseph. “Guide for Writing a Funding Proposal.” http://www.learnerassociates.net/proposal/ .

Locke, Lawrence F., Waneen Wyrick Spirduso, and Stephen J. Silverman. 2014. Proposals That Work . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Przeworski, Adam, and Frank Salomon. 2012. “Some Candid Suggestions on the Art of Writing Proposals.” Social Science Research Council. https://s3.amazonaws.com/ssrc-cdn2/art-of-writing-proposals-dsd-e-56b50ef814f12.pdf .

Reif-Lehrer, Liane. 1989. Writing a Successful Grant Application . Boston: Jones and Bartlett Publishers.

Wiggins, Beverly. 2002. “Funding and Proposal Writing for Social Science Faculty and Graduate Student Research.” Chapel Hill: Howard W. Odum Institute for Research in Social Science. 2 Feb. 2004. http://www2.irss.unc.edu/irss/shortcourses/wigginshandouts/granthandout.pdf.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Submissions & Reviews

- Publishing & Journals

- Scholarships

- Best Practices

- News & Updates

- Resources Home

- Submittable 101

- Bias & Inclusivity Resources

- Customer Stories

- Get our newsletter

- Request a Demo

How to Review a Grant Proposal in 4 Essential Steps

Updated: 02/01/2023

4 key strategies for fair and effective grant review

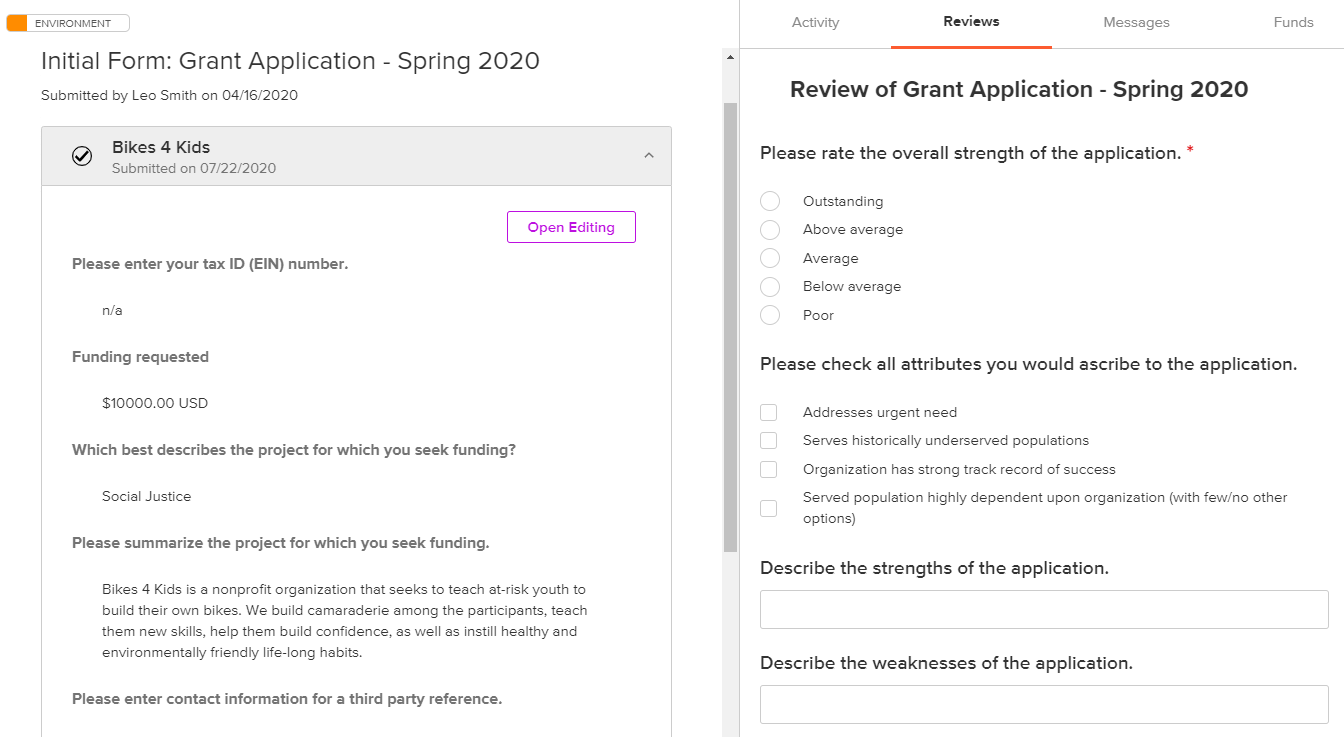

The review process for grant proposals is where funders and organizations get to execute on their stated values. But selecting which grants to fund to pursue mission-driven outcomes is a big task—and it starts with understanding how to review a grant proposal effectively and efficiently.

With so many important and worthy causes or works out there, the process can be difficult emotionally, but it doesn’t have to be challenging operationally. From individual reviewers and program officers to directors and board members, reviewing grants can and should be streamlined so that impact can be maximized and hassle can be minimized.

Lucky for us, our team has seen thousands of grantmakers and individual grant reviewers tackle grant review through our grant management software . Here’s a look at how they manage it and how you can too.

Note: While we believe these efforts are best led from the organizational level in order to create consistency, if you’re an individual reviewer without clear direction, you can use these tips to create your own personal reviewing framework.

4 steps for reviewing grant proposals

1. set principles for how you review grant proposals..

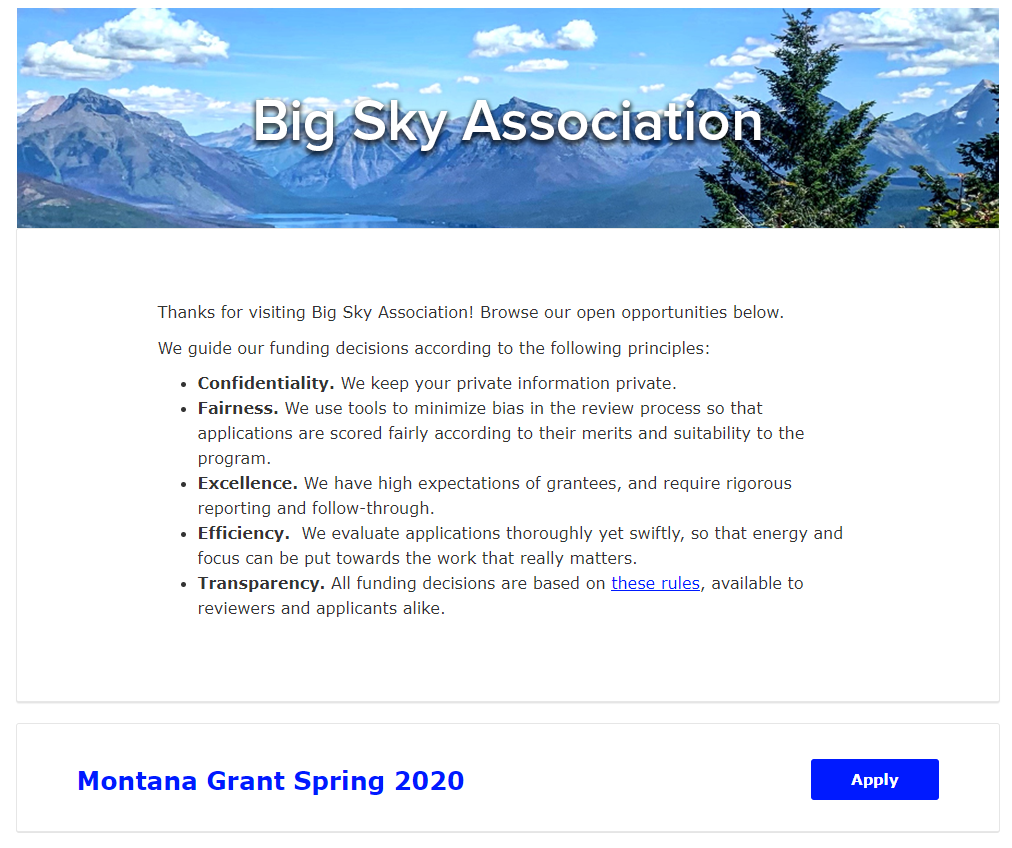

At the highest level, you’ll want your grant review process to be guided by a few key principles, grounded in what produces the best application and review experiences for all parties.

Ideally, these are set at the organizational level before individual grant reviewers begin evaluating applications.

But in cases where there isn’t organizational guidance, individual reviewers can also consider the principles they want to bring to their task.

Here are a few guideposts we consistently see used as resources:

- Confidentiality. Keep grant-seekers’ private information on a need-to-know basis within one centralized grant management platform that you can easily control. To minimize the risk of implicit bias or favoritism, pinpoint which elements are absolutely essential for reviewers to make their decision—and which aren’t.

- Fairness. Set up a grant review process that is as free of bias as possible, allowing reviewers to score applicants fairly and based on their relevant merits and suitability to the program.

- Excellence. Grant-seekers and grantmakers both want projects that demonstrate a high level of quality. Having rigorous reporting metrics for the grant itself at the outset also helps set expectations for grantees and communicates that follow-through is expected in terms of the grant objectives.

- Efficiency. When grant proposals are evaluated fully and grants awarded and administered as swiftly as possible, more energy and focus can be put towards the work that really matters.

- Transparency. All funding decisions should be based on clearly defined rules that are communicated to grant-seekers and team members before any grant applications are reviewed.

Communicate these principles along with your application guidelines up front as a resource to applicants. Clarity around expectations and review criteria can help you receive more relevant applications and reduce questions, saving your review team time.

Here’s an example of how the principles above could be added to an organization’s main portal in Submittable:

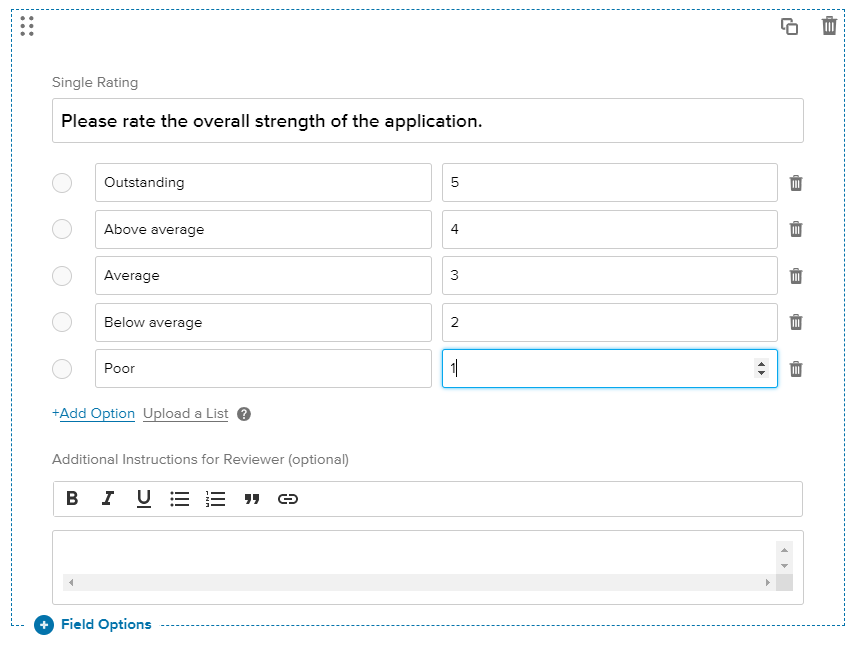

2. Build a detailed review rubric to evaluate grants.

The first step to effectively critiquing a grant proposal is the creation of a thorough rubric. Rubrics are detailed outlines for how each application will be read and scored. A comprehensive rubric helps reviewers stay consistent, minimizes personal bias, and provides a useful resource to answer questions.

If you create a rubric before building your application, it can also help ensure all requested information in your application is relevant and necessary. This saves time for applicants as well as your team.

According to research from the Brown University’s Harriet W. Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning , there are a series of vital steps to creating a successful rubric. Here are a few of the steps they identified, refocused for grant review:

Define the rubric’s purpose

Consider the components of your application and how each should be assessed. What would an outstanding application include? How detailed do you want to be with scoring? Should each application component receive a distinct score?

Choose between a holistic and analytical rubric

In terms of basic distinctions, the holistic rubric is easier to put together but offers less detail than an analytic rubric regarding specific strengths and weaknesses within an application.

For example, a holistic rubric might ask reviewers to assign a score of 1-5 for the application as a whole (where a Level 5 application includes excellent references, a strong evidence-based rationale for the project, and how project goals and objectives will be achieved and assessed is clearly defined).

An analytic rubric would assess references, rationale, and goals and objectives using distinct scales and criteria.

Define the review criteri a

These criteria identify each component for assessment.

First, design a rating scale. For grant applications, numeric scores are most likely to be useful. Most scales include three to five rating levels.

Then, write descriptions for each rating. Focus on observations that can be accurately measured and include the degree to which criteria are successfully met.

Clarity and consistency of language here will help accurately guide reviewers as they reach each grant proposal.

Finalize the rubric

Once you have your rubric and review criteria defined, add them to your grants management software so that the same rubric is automatically applied to every application for every reviewer.

With Submittable’s grant management software , this step can take just minutes. A drag-and-drop form builder—the same type you use in the platform to build your application—makes it easy to create a custom form that gathers the qualitative and quantitative feedback you want.

Once your rubric is added, all your grant reviewers can see application materials in one place, side-by-side with the rubric criteria within the Submittable platform, and enter scores and feedback as they go. No more toggling between tabs, drowning in email, or time-consuming downloads.

Check out this short video for a quick step-by-step walk-through of how to set up a review process in Submittable:

A couple of additional rubric strategies to employ:

- Assess your rubric carefully for language that could be misinterpreted. It’s important to avoid assumptions about reviewers, especially regarding how they will process the criteria, rating scale, and descriptions you provide.

- Steer clear of industry jargon or acronyms. Use plain language and where possible give examples to solidify what you want to say and avoid questions.

- Determine the relative weight of review criteria. For example, will letters of recommendation be more or less important than a clear evaluation framework? Design your rating scale accordingly.

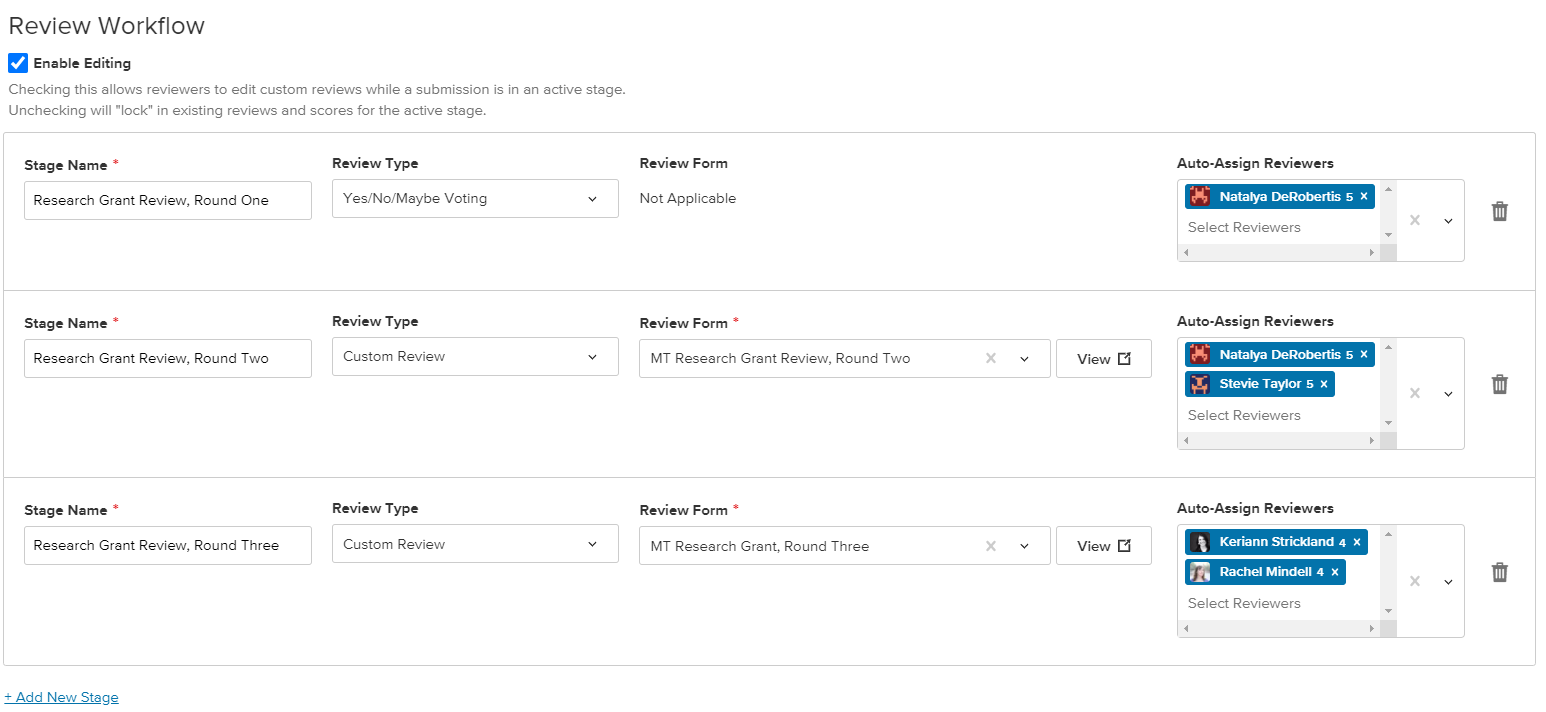

3. Make good assignments.

By making clear your foundational principles and defining a clear rubric to judge applications, you’ve laid the groundwork for your reviewers to begin their work. Now is the point where you need to make sure your team executes that plan in a consistent and coordinated manner.

Spread out the work

A review team, as opposed to a single reviewer or two, will ensure a more fair assessment for every applicant.

If you’re offering a single grant, have two or three readers on each application. If you’re running several, you could group reviewers into teams, group applications by category, or rotate reviewers and applications throughout the process.

Reviewing across days, as opposed to completing all reviews in a single, long session, is more likely to yield a greater uniformity (and fairness) in your results. Encourage reviewers to divide and conquer over time by assigning in batches or rounds, or by establishing multiple deadlines and check-in points along the way.

Help reviewers write better grant critiques

Sharing your review process and criteria with applicants demonstrates that you care about diligent and fair review. It also demonstrates that you understand the value this information holds for applicants and you’re prepared to support them.

But how do you write a good grant critique? Lean on the rubric. The more detailed, thorough, and consistent your rubric is, the more useful it becomes when providing feedback.

This also keeps feedback consistent across reviewers and applications, and makes it easier for you to compare results when making your final choice.

Just be sure grant reviews are easy to share and written in a simple, jargon-free format.

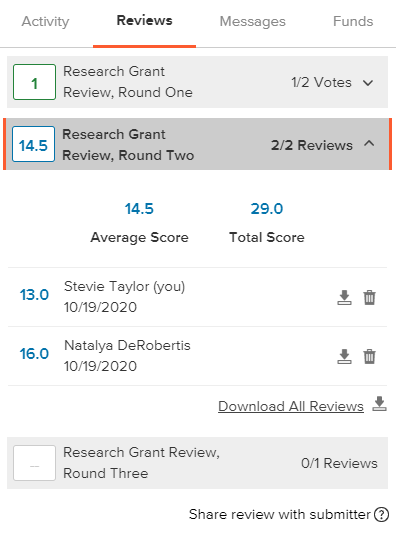

4. Use a numerical strategy to find a winner.

There are two main approaches to capturing which applications are top contenders.

One strategy for scoring applications fairly is through a point system defined by your rubric. This type of averaging system is typically used for standards-based processes, which makes it extremely useful for scoring grant applications.

Calculate an average by adding all scores together and dividing by how many times the application was read. This ensures that each reviewer’s assessment has an equal weight.

A ranking system can be another great collaborative way to select grant winners. Using this strategy, reviewers are assigned a set number of applications to read and rank in quality order. Let’s say a reviewer is reviewing five applications—the best one would score a 1, the next best a 2, and so on, with the least favorite receiving a 5.

Then, each set of applications is passed on between other reviewers, who will also rank in order of quality. If reviewers are tasked with a high volume of applications, this method can help alleviate the pressure.

To find the strongest applications, add up the scores among all applications—the ones with the highest scores are ranked highest collectively.

Want to improve your grant review process?

With Submittable’s grant management software, you can review grant proposals more efficiently, with less bias.

Watch our short demo to learn more.

Go forth, and review

Launching a grant program based on a review process that’s fair, rigorous, and efficient relies on intentional planning, research, and thoughtful execution.

Just as your programs are unique, a review process that’s both fair and rigorous will look a bit different in every institution. The most important areas to focus on are a strong rubric, transparency, inclusivity, a balanced, numbers-based process, and the evasion of bias.

At their core, grants serve a primary mission—to fund worthy ideas and projects. A modern grants management software like Submittable can make it that much easier to establish or fine-tune your outstanding application and review process, so that both your applicants and your review team appreciate the results.

Keriann Strickland is the Chief Marketing Officer of Submittable. She's a recovering journalist, mountain lover, and gifted spiller (and speller).

Better grants management starts here

Try the trusted and intuitive option for streamlined grants management.

Watch a demo

About Submittable

Submittable powers you with tools to launch, manage, measure and grow your social impact programs, locally and globally. From grants and scholarships to awards and CSR programs, we partner with you so you can start making a difference, fast. The start-to-finish platform makes your workflow smarter and more efficient, leading to better decisions and bigger impact. Easily report on success, and learn for the future—Submittable is flexible and powerful enough to grow alongside your programs.

Submittable is used by more than 11 thousand organizations, from major foundations and corporations to governments, higher education, and more, and has accepted nearly 20 million applications to date.

HOW IT WORKS

- IT/Operations

- Professional Services & Consulting

- IT and Software Solutions

- Facilities & Maintenance

- Infrastructure & Construction

Want help from the experts?

We offer bespoke training and custom template design to get you up and running faster.

- Books & Guides

- Knowledge Base

State of Proposals 2024

Distilling the data to reveal our top tips for doing more business by upping your proposal game.

- Book a demo

- Sign Up Free

Step-By-Step Guide to Writing a Grant Proposal

Writing a grant proposal is incredibly time-consuming.

No joke. It's one of the most complicated documents you could write in your entire life.

There are different requirements, expectations, and formats—not to mention all the prep work you need to do, like market research and clarifying your project timeline.

Depending on the type of company or organization you represent and which grants you’re applying for, your grant could run anywhere from a dozen to a hundred pages. It’s a lot of work, and we’re here to help.

In this guide to grant proposals, we offer writing steps and examples, as well as resources and templates to help you start applying for funding right away.

Types of grant proposals

Grant proposals typically fall into one of these main categories:

Research grant proposals - Research grant proposals are usually sent by university professors or private research organizations in order to fund research into medical, technological, engineering, and other advancements.

Nonprofit grant proposals - Nonprofits send grant proposals to philanthropic organizations and government agencies to acquire funds for community development, health, education, and similar projects.

Technology grant proposals - Grant proposals can also be sent by technology companies (software, hardware, solar, recycling, environmental, manufacturing, health, and other types of tech companies). These proposals are often sent to large government organizations looking for solutions to current and future problems, as well as VC firms looking to invest in smart startups.

Small business grant proposals - Local governments often give grant awards to small businesses to help them kickstart, market, or expand.

Arts grants - Grants allow artists that would otherwise lack the financial resources to devote extended periods of time to their art. They might need to complete an installation that can be enjoyed by the community as part of the grant.

Grant RFP proposals - There can also be a request for proposals (RFP) for just about anything. From multinational organizations like the UN to family philanthropic grants, you can find RFPs for a variety of projects.

How to prep before you write

Before you can sit down to write your grant proposal, you’ll need to have a deep understanding of:

Existing scientific literature (for research grants) or relevant reports and statistics

Market and competitor landscape

Current available solutions and technologies (and why they’re not good enough)

Expected positive impact of your project

The methods and strategies you’ll employ to complete your project

Project phases and timelines

Project budget (broken down into expense categories)

With these things all buttoned down, you’ll have a much easier time writing the sections that cover those details, as well as the sections that highlight their meaning and importance (such as your statement of need and objectives).

Create a document where you can play around. Take notes, write down ideas, link out to your research, jot down different potential budgets, etc.

Then, when you’re ready to write, create a fresh document for your actual grant proposal and start pulling from your notes as needed.

How to write a grant proposal (ideal format)

Now, let’s get writing.

The ideal outline for a grant proposal is:

Cover Letter

Executive summary, table of contents, statement of need, project description, methods and strategies, execution plan and timeline, evaluation and expected impact, organization bio and qualifications.

If you’re not writing a super formal grant proposal, you might be able to cut or combine some of these sections. When in doubt, check with the funding agency to learn their expectations for your proposal. They might have an RFP or other guidelines that specify the exact outline they want you to follow.

Note: In business proposals, the cover letter and executive summary are the same, and those phrases are used interchangeably. But for grant proposals, the cover letter is a short and simple letter, while the executive summary offers a description of key aspects of the proposal.

In your cover letter, you'll write a formal introduction that explains why you are sending the proposal and briefly introduces the project.

What to include :

The title of the RFP you are responding to (if any)

The name of your proposed project (if any)

Your business or nonprofit organization name

A description of your business or organization, 1-2 sentences

Why you are submitting the proposal, in 1-2 sentences

What you plan to do with the funds, in 2-4 sentences

Dear [Name], The Rockville Community Garden is responding to the city of Rockville’s request for proposals for nonprofit community improvement projects. The Rockville Community Garden is a space for relaxation, healthy eating, exercise, and coming together. We are submitting a proposal to request funding for Summer at the Garden. Every summer, parents are tasked with finding childcare for their children, and we have received countless requests to host a summer camp. We're requesting funding to cover tuition for 100 low-income children ages 5 to 12. The funds will make our summer camp accessible to those who need it most. Thank you for your consideration, [Signature] [Title]

The executive summary of a grant proposal goes into far more detail than the cover letter. Here, you’ll give

Statement of Need overview, in 2 - 5 sentences

Company Bio and Qualifications, in 2 - 5 sentences

Objectives, in 2 - 5 sentences

Evaluation and Expected Impact, in 2 - 5 sentences

Roman architecture stands the test of time until it doesn’t. Roman building techniques can last thousands of years but will crumble to dust instantaneously when earthquakes strike. Meanwhile, our own building techniques of reinforced concrete and steel last only a couple of centuries. Ancient Architecture Research firm is dedicated to modernizing roman building techniques to create new structures that are earthquake safe and sustainable. Our principle investigators hold PhDs from renowned architecture universities and have published in numerous journals. Our objectives for the research grant are to create a prototype structure using Roman building techniques and test it on a shake table to simulate an earthquake. The prototype will pave the way for our application for an amendment to the California building code to permit unreinforced masonry construction. With the success of the prototype, we will prove the safety and viability of this technique. This project will have an enormous potential impact on several crises plaguing the state of California now and in the future: disaster relief, affordable housing, homelessness, and climate migration. Unreinforced masonry construction can be taught and learned by amateur builders, allowing volunteers to quickly deploy temporary or permanent structures.

Next up, you need your Table of Contents! Make sure it matches the names of each of your following sections exactly. After you’ve written, edited, and finalized your grant proposal, you should then enter accurate page numbers to your TOC.

Next up is the statement of need. This is where you sell why you’re submitting your grant request and why it matters.

A description of who will benefit from your proposal

Market and competitive analysis

Statistics that paint a picture of the problem you’re solving

Scientific research into how the problem is expected to worsen in the future

Reasons why your small business deserves funding (founder story, BIPOC founder, female founder, etc.)

While women hold 30% of entry-level jobs in tech, they only make up 10% of C-suite positions. The Female Leadership Initiative seeks to develop women tech leaders for the benefit of all genders. Female leaders have been proven to positively impact work-life balance, fairer pay, creativity, innovation, teamwork, and mentorship.

In this section, you’ll describe the basics of your research project, art project, or small business plan. This section can be kept fairly short (1 - 3 paragraphs), because you’ll be clarifying the details in the next 5 paragraphs.

The name of your project (if any)

Who will benefit from your project

How your project will get done

Where your project will take place

Who will do the project

The Fair Labor Project will seek to engage farm workers in the fields to identify poor working conditions and give back to those who ensure food security in our communities. Trained Spanish-speaking volunteers will visit local farms and speak with workers about their pay and work conditions, helping to uncover any instances of abuse or unfair pay. Volunteers will also pass out new work gloves and canned food. Volunteers will also place orders for work boots and ensure that boots are later delivered to workers that need them.

You should also write out clear goals and objectives for your grant proposal. No matter the type of agency, funding sources always want to see that there is a purpose behind your work.

Measurable objectives tied directly to your proposed project

Why these objectives matter

We seek to boost volunteer turnout for our voter registration efforts by 400%, allowing us to reach an additional 25,000 potential voters and five additional neighborhoods.

Now it’s time to clarify how you’ll implement your project. For science and technology grants, this section is especially important. You might do a full literature review of current methods and which you plan to use, change, and adapt. Artists might instead describe their materials or process, while small business grant writers can likely skip this section.

The names of the methods and strategies you will use

Accurate attribution for these methods and strategies

A literature review featuring the effectiveness of these methods and strategies

Why you are choosing these methods and strategies over others

What other methods and strategies were explored and why they were ultimately not chosen

“We plan to develop our mobile app using React Native. This framework is widely regarded as the future of mobile development because of the shared codebase that allows developers to focus on features rather than create everything from scratch. With a high workload capacity, react native also provides user scalability, which is essential for our plan to offer the app for free to residents and visitors of Sunny County.”

You’ll also need to cover how you plan to implement your proposal. Check the RFP or type or grant application guidelines for any special requirements.

Project phases

The reasoning behind these phases

Project deliverables

Collaborators

In our experience and based on the literature,11,31-33 program sustainability can be improved through training and technical assistance. Therefore, systematic methods are needed to empirically develop and test sustainability training to improve institutionalization of evidence-based programs. This will be accomplished in three phases. In Phase 1, (yr. 1, months 1-6) we will refine and finalize our Program Sustainability Action Planning Model and Training Curricula. As part of this refinement, we will incorporate experiential learning methods3-6 and define learning objectives. The Program Sustainability Action Planning Training will include action planning workshops, development of action plans with measurable objectives to foster institutional changes, and technical assistance. We will also deliver our workshops in Phase 1 (yrs. 1 and 2, months 6-15) to 12 state TC programs. Phase 2 (yrs. 1, 2, and 3) uses a quasi-experimental effectiveness trial to assess the Program Sustainability Action Planning Training in 24 states (12 intervention, 12 comparison). Evaluation of our training program is based on the theory of change that allows for study on how a change (intervention) has influenced the design, implementation, and institutionalization of a program.7,8,11,28 We will collect data on programmatic and organizational factors that have been established as predictors of sustainability9,11 using state level programmatic record abstraction and the Program Sustainability Assessment Tool (PSAT)43 to assess level of institutionalization across intervention and comparison states at three time points. Data will be used to establish the efficacy of the Program Sustainability Action Planning Model and Training Curricula. In Phase 3 (yr. 4, months 36-48), we will adapt our training based on results and disseminate Program Sustainability Action Planning Model and Training materials. - From Establishing The Program Sustainability Action Planning Training Model

A budget table with various expense categories

An explanation of what each category entails

Expenses broken down by month or year (if this fits your proposal)

Here’s an example budget table with expense categories:

You can then include a brief description of each category and the expenses you expect within them.

A great grant proposal should clarify how you will measure positive outcomes and impact.

Details on the expected impact of your project

Who will benefit from your project and how

Your plan for evaluating project success

How you will measure project success

We will measure the success of the project by monitoring the school district’s math scores. We are expecting an 8% increase in state testing scores from the fall to the spring across grades 1 through 3.

And lastly, finish up your grant proposal with a bio of your organization, your company, or yourself.

Company name

The names of people on your team

Professional bios for everyone on your team

Your educational background

Any relevant awards, qualifications, or certifications

Jane Doe received her masters in fine arts specializing in ceramics from Alfred University. She has received the Kala Fellowship and the Eliza Moore Fellowship for Artistic Excellence.

Successful grant proposal examples

Want to write winning grant applications?

We’ve rounded up examples of successful, awarded grants to help you learn from the best.

Check out these real examples across science, art, humanities, agriculture, and more:

Funded arts and research grants from the University of Northern Colorado

Samples of awarded proposals from the Women’s Impact Network

National Cancer Institute examples of funded grants

Institute of Museum and Library Services sample applications

Specialty Crop Block Grant Program awarded grants examples

Grant application and funding resources

To help you get started writing and sending grant proposals, we’ve found some great application resources.

Research grants:

United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) grants

William T. Grant Foundation grants on reducing inequality

Russel Sage Foundation research grants

Nonprofit grants:

Walmart’s Local Community Grants

Bank of America’s Grant Funding for Nonprofits

Canada GrantWatch’s database of nonprofit grants

Technology grants:

Google Impact Challenges

UN Sustainable Development Goals Fund

US Department of Energy Funding

Small business grants:

US Chamber of Commerce Small Business grants

Canada Small Business Benefits Finder

US Small Business Administration (SBA) grants

Arts grants :

National Endowment for the Arts grants

Art Prof Artist Grants

Canada Council for the Arts grants

Get started with our proposal writing templates

The best way to start any proposal is with a template. A template informs your writing, while drastically speeding up the time it takes to design an attractive proposal.

All of our 75+ proposal templates can easily be adapted for any purpose, including grants or requests for funding. Try our project proposal template and make it your own by adding your executive summary, statement of need, project description, execution plan, budget, and company bio.

Start a free trial to check out all of our proposal software features , including reusable content snippets, e-signatures, viewing and signing analytics, and more.

Dayana Mayfield is a B2B SaaS copywriter who believes in the power of content marketing and a good smoothie. She lives in Northern California. Connect with her on LinkedIn here: linkedin.com/in/dayanamayfield/

Subscribe via Email

Related posts.

![literature review grant proposal How to Write a Proposal in 10 Easy Steps [Templates Included]](https://www.proposify.com/hs-fs/hubfs/Imported_Blog_Media/blog_2022-11-08_writeproposal-Apr-09-2024-03-56-17-4124-PM.jpg?width=450&height=250&name=blog_2022-11-08_writeproposal-Apr-09-2024-03-56-17-4124-PM.jpg)

| All accounts allow unlimited templates. | |||

| Create and share templates, sections, and images that can be pulled into documents. | |||

| Images can be uploaded directly, videos can be embedded from external sources like YouTube, Vidyard, and Wistia | |||

| You can map your domain so prospects visit something like proposals.yourdomain.com and don't see "proposify" in the URL | |||

| Basic | Team | Business | |

| All plans allow you to get documents legally e-signed | |||

| Allow prospects to alter the quantity or optional add-ons | |||

| Capture information from prospects by adding form inputs to your documents. | |||

| Basic | Team | Business | |

| Get notified by email and see when prospects are viewing your document. | |||

| Generate a PDF from any document that matches the digital version. | |||

| Get a full exportable table of all your documents with filtering. | |||

| Basic | Team | Business | |

| Connect your Stripe account and get paid in full or partially when your proposal gets signed. | |||

| Create your own fields you can use internally that get replaced in custom variables within a document. | |||

| All integrations except for Salesforce. | |||

| You can automatically remind prospects who haven't yet opened your document in daily intervals. | |||

| Lock down what users can and can't do by role. Pages and individual page elements can be locked. | |||

| Create conditions that if met will trigger an approval from a manager (by deal size and discount size). | |||

| Use our managed package and optionally SSO so reps work right within Salesforce | |||

| Our SSO works with identity providers like Salesforce, Okta, and Azure | |||

| Great for multi-unit businesses like franchises. Enables businesses to have completely separate instances that admins can manage. | |||

| Basic | Team | Business | |

| Our team is here to provide their fabulous support Monday - Thursday 8 AM - 8 PM EST and on Fridays 8 AM - 4 PM EST. | |||

| Sometimes the written word isn't enough and our team will hop on a call to show you how to accomplish something in Proposify. | |||

| Your own dedicated CSM who will onboard you and meet with you periodically to ensure you're getting maximum value from Proposify. | |||

| We'll design your custom template that is built with Proposify best-practices and train your team on your desired workflow. | |||

| Our team of experts can perform advanced troubleshooting and even set up zaps and automations to get the job done. |

Subscribe via email

Preparing a grant proposal - Part 2: Reviewing the literature

- Academics (Nursing)

Research output : Contribution to journal › Review article › peer-review

The grant proposal literature review is a focused and succinct systhesis of research pertinent to the research questions contained in a proposal. The optimal review should briefly present existing knowledge about the specific topic contained in the application and persuade the reviewer that the research proposed is the next logical step toward expanding our understanding of the clinical problem at hand.

| Original language | English (US) |

|---|---|

| Pages (from-to) | 83-86 |

| Number of pages | 4 |

| Journal | |

| Volume | 32 |

| Issue number | 2 |

| DOIs | |

| State | Published - 2005 |

Publisher link

- 10.1097/00152192-200503000-00004

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

- Link to the citations in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Grant Proposal Keyphrases 100%

- Systhesis Keyphrases 50%

- Persuade Keyphrases 50%

- Specific Topic Keyphrases 50%

- Existing Knowledge Keyphrases 50%

- Clinical Problems Keyphrases 50%

T1 - Preparing a grant proposal - Part 2

T2 - Reviewing the literature

AU - Gray, Mikel

AU - Bliss, Donna Zimmaro

N2 - The grant proposal literature review is a focused and succinct systhesis of research pertinent to the research questions contained in a proposal. The optimal review should briefly present existing knowledge about the specific topic contained in the application and persuade the reviewer that the research proposed is the next logical step toward expanding our understanding of the clinical problem at hand.

AB - The grant proposal literature review is a focused and succinct systhesis of research pertinent to the research questions contained in a proposal. The optimal review should briefly present existing knowledge about the specific topic contained in the application and persuade the reviewer that the research proposed is the next logical step toward expanding our understanding of the clinical problem at hand.

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=15944379561&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=15944379561&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1097/00152192-200503000-00004

DO - 10.1097/00152192-200503000-00004

M3 - Review article

C2 - 15867697

AN - SCOPUS:15944379561

SN - 1071-5754

JO - Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing

JF - Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

How to Write a Successful Research Grant Proposal: An Overview

Writing a research grant proposal can be a challenging task, especially for those who are new to the process. However, a well-written proposal can increase the chances of receiving the necessary funding for your research.

This guide discusses the key criteria to consider when writing a grant proposal and what to include in each section.

Table of Contents

Key criteria to consider

When writing a grant proposal, there are five main criteria that you need to consider. These are:

- Significance

- Innovation

- Investigators

- Environment

The funding body will look for these criteria throughout your statement, so it’s important to tailor what you say and how you say it accordingly.

1. Significance

Significance refers to the value of the research you are proposing. It should address an important research problem and be significant in your field or for society. Think about what you are hoping to find and how it could be valuable in the industry or area you are working in. What does success look like? What could follow-on work lead to?

2. Approach

Approach refers to the methods and techniques you plan to use. The funding body will be looking at how well-developed and integrated your framework, design, methods, and analysis are. They will also want to know if you have considered any problem areas and alternative approaches. Experimental design, data collection and processing, and ethical considerations all fall under this group.

3. Innovation

Innovation means that you are proposing something new and original. Your aims should be original and innovative, or your proposed methods and approaches should be new and novel . Ideally both would be true. Your project should also challenge existing paradigms or develop new methodologies or technologies.

4. Investigators

Investigators here refer to you and your team, or proposed team. The funding body will want to know if you are well-trained and have the right qualifications and experience to conduct the research . This is important as it shows you have the ability to undertake the research successfully. One part of this evaluation will be, have you been awarded grants in the past. This is one reason to start early in your career with grant applications to smaller funds to build up a track record.

5. Environment

Environment refers to the scientific environment in which the work will be done. The funding body will want to know if the scientific environment will contribute to the overall probability of success. This could include your institution, the building or lab you will be working in, and any collaborative arrangements you have in place. Any similar research work conducted in your institution in the past will show that your environment is likely to be appropriate.

Writing the grant proposal

It’s almost impossible to generalize across funders, since each has its own highly specific format for applications, but most applications have the following sections in common.

1. Abstract

The abstract is a summary of your research proposal. It should be around 150 to 200 words and summarize your aims, the gap in literature, the methods you plan to use, and how long you might take.

2. Literature Review

The literature review is a review of the literature related to your field. It should summarize the research within your field, speaking about the top research papers and review papers. You should mention any existing knowledge about your topic and any preliminary data you have. If you have any hypotheses, you can add them at the end of the literature review.

The aims section needs to be very clear about what your aims are for the project. You should have a couple of aims if you are looking for funding for two or three years. State your aims clearly using strong action words.

4. Significance

In this section, you should sell the significance of your research. Explain why your research is important and why you deserve the funding.

Defining Your Research Questions

It’s essential to identify the research questions you want to answer when writing a grant proposal. It’s also crucial to determine the potential impact of your research and narrow your focus.

1.Innovation and Originality

Innovation is critical in demonstrating that your research is original and has a unique approach compared to existing research. In this section, it’s essential to highlight the importance of the problem you’re addressing, any critical barriers to progress in the field, and how your project will improve scientific knowledge and technical capabilities. You should also demonstrate whether your methods, technologies, and approach are unique.

2. Research approach and methodology

Your research approach and methodology are crucial components of your grant proposal. In the approach section, you should outline your research methodology, starting with an overview that summarizes your aims and hypotheses. You should also introduce your research team and justify their involvement in the project, highlighting their academic background and experience. Additionally, you should describe their roles within the team. It’s also important to include a timeline that breaks down your research plan into different stages, each with specific goals.

In the methodology section, detail your research methods, anticipated results, and limitations. Be sure to consider the potential limitations that could occur and provide solutions to overcome them. Remember, never give a limitation without providing a solution.

Common reasons for grant failure

Knowing the common reasons why grant proposals fail can help you avoid making these mistakes. The five key reasons for grant failure are:

- Poor science – The quality of the research is not high enough.

- Poor organization – The proposal is not organized in a clear way.

- Poor integration – The proposal lacks clear integration between different sections.

- Contradiction – The proposal contradicts itself.

- Lack of qualifications or experienc e – The researcher lacks the necessary qualifications or experience to conduct the research.

By avoiding these pitfalls, you will increase your chances of receiving the funding you need to carry out your research successfully.

Tips for writing a strong grant proposal

Writing a successful grant proposal requires careful planning and execution. Here are some tips to help you create a strong grant proposal:

- Begin writing your proposal early. Grant proposals take time and effort to write. Start as early as possible to give yourself enough time to refine your ideas and address any issues that arise.

- Read the guidelines carefully . Make sure to read the guidelines thoroughly before you start writing. This will help you understand the requirements and expectations of the funding agency.

- Use clear, concise language . Avoid using technical jargon and complex language. Write in a way that is easy to understand and conveys your ideas clearly. It’s important to note that grant reviewers are not likely to be domain experts in your field.

- Show, don’t tell . Use specific examples and evidence to support your claims. This will help to make your grant proposal more convincing.

- Get feedback . Ask colleagues, mentors, or other experts to review your proposal and provide feedback. This will help you identify any weaknesses or areas for improvement.

Conclusion

Writing a successful grant proposal is an important skill for any researcher. By following the key criteria and tips outlined in this guide, you can increase your chances of securing funding for your research. Remember to be clear, concise, and innovative in your writing, and to address any potential weaknesses in your proposal. With a well-written grant proposal, you can make your research goals a reality.

If you are looking for help with your grant application, come talk to us at GrantDesk. We have grant experts who are ready to help you get the research funding you need.

Related Posts

What are the Best Research Funding Sources

Inductive vs. Deductive Research Approach

Grant Writing Support @ Clemson Libraries: Tips for Your Literature Review

- Finding & Writing Grants

- Tips for Your Literature Review

- Your Data Management Plan

- Cite Sources

General Tips

1. Find your words.

- Write down terms related to your central research question. Try to think of ANY way that your research might be described by other research.

2. Select the databases you'll use to search for your words.

- Use library research guides on your topic to select discipline-specific databases.

- Make an appointment with your subject librarian if you have any doubts about what to include in your search.

3. Keep track of your searches!

- Write down or save searches in different databases so that you don't duplicate efforts.

- Use RefWorks to keep track of your research citations.

- Use the bibliographies of relevant research studies to find other related research.

- Keep any notes for future reference.

4. Tips for reviewing the literature:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing?

- What was the funding source for the research and would that have any influence over the findings?

- How was the research conducted? Could it have been done better?

- Has this research been cited in other studies? How is the author viewed in the field?

Keyword Tips

1. Use Simple Terms

Use short, simple words or phrases. Don't type in your entire topic as one sentence.

EXAMPLE: If you're writing about "the importance of peer relationships in the developmental stage of middle childhood," search only the key words/phrases: peer relationships and development and childhood.

2. Use Search Symbols ( Boolean )

or = expand your search by including different forms of a word. EXAMPLES: Stocks or bonds. Cats or felines.

" " = search for a specific phrase. EXAMPLE: "World War Two"

* = add 1-5 characters to the end of a word. EXAMPLES: Panda* finds panda and pandas. Inter* finds internal and internet.

3. Start Broad

If you get too many results, you can always narrow your search terms later.

Publically Available Research Descriptions

If you are a researcher who does not have access to Clemson databases, be sure to check with your local or institutional library. There are also a number of freely accessible databases of research:

- Google Scholar (with Clemson links) This link opens in a new window Use this link to this open resource, in order to link directly to Clemson-owned/subscribed content.

- PubMed PubMed comprises more than 24 million citations for biomedical literature from MEDLINE, life science journals, and online books. Citations may include links to full-text content from PubMed Central and publisher web sites.

- << Previous: Finding & Writing Grants

- Next: Your Data Management Plan >>

- Last Updated: Aug 7, 2024 6:35 PM

- URL: https://clemson.libguides.com/grantwriting

Best Practices for Developing Grant Proposals

Share this story.

“We know that scientific integrity occurs throughout the research life cycle and part of that really begins at the foundation of a project and a proposal,” said Monica Lemmon, MD, Associate Dean for Scientific Integrity, at the start of the Duke Office of Scientific Integrity Research Town Hall on October 16th. Grant preparation is an integral part of the research process, and the discussions highlighted best practices, paths to community engagement, and the wealth of resources available to the Duke research community.

Michelle J. White MD, MPH , Assistant Professor of Pediatrics and Population Health Sciences, presented on building multidisciplinary, community-academic teams. Dr. White said that she draws inspiration from superheroes, where everyone brings complementary strengths that make the team stronger as whole. This involves examining the expertise team members can bring along with individual personalities. It is also important to include an examination of who is needed to get the work done well and equitably . Dr. White encouraged researchers to consider involving members of the community and community-based organizations. Researchers should give thought to whose voices are missing from a project, especially marginalized groups and those with different cultural backgrounds. Engaging the community in research should focus on acknowledging past harms that may have been caused, ensure that the work is mutually beneficial for the researchers and the community, set clear goals and expectations, and also provide appropriate payments for time, space, and expertise. For further resources, she recommended the Community Engaged Research Initiative , the LEADER program , Scholars@Duke , and the NIH Reporter .

Elizabeth Gifford, PhD , Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Population Health Sciences, presented on the foundations of multidisciplinary collaboration. Her talk aimed to give a perspective on how collaborations actually form. For early stage researchers, these collaborations often start as opportunities to demonstrate interest or highlight past work to more senior researchers in a given field. These opportunities are often the result of match-making efforts facilitated by more senior researchers who server not only as a mentor but also foster opportunities through this form of sponsorship. She also spoke on the “grant-getting” process, and how even though many proposals may not end up getting funded, the process of putting in the work to develop an idea and coordinate with other investigators can still lead to tangible, positive results .