Living on Other Planets: What Would It Be Like?

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to live on the moon? What about Mars, or Venus or Mercury? We sure have and that's why we decided to find out what it might be like to live on other worlds in our solar system, from Mercury to Pluto and beyond in a new, weekly 12-part series.

For this series, written by Space.com contributor Joseph Castro, we wanted to know what the physical sensation of living on other worlds would be like: What would the gravity be like on Mercury; How long would your day be on Venus? What's the weather on Titan ?

For the sake of our solar system tour, let's take it as a given that humanity has the futuristic tech needed to set up a base on the planets. So join Space.com each week as we skip across the solar system and see what it would feel like to live beyond Earth. Check out our schedule for the tour through the solar system and beyond below:

Wednesday, Jan. 28 – Mercury

What Would It Be Like to Live on Mercury? The closest planet to the sun is an inhospitable place, and probably not the first choice for human colonization. But if somehow we had the technology, what would it be like for people to live on Mercury?

10 Strange Facts About Mercury (A Photo Tour) Mercury is a weird place. See just how weird the closest planet to the sun is in our photo tour.

Living on Mercury Would be Hard (Infogaphic) So you've read what it might be like to be a colonist on Mercury. Now see the details in visual form. Space.com's Karl Tate lays out what livingon Mercury might be like for an astronaut.

More about Mercury:

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

- Planet Mercury: Facts About the Planet Closest to the Sun

- How Was Mercury Formed?

- What is Mercury Made Of?

- Mercury's Atmosphere

- How Hot is Mercury?

- How Far is Mercury From the Sun?

- How Big is Mercury?

Tuesday, Feb. 3 – Venus

What Would It Be Like to Live on Venus? From its hellish temperatures to crushing pressures and volcanoes, the planet Venus might be a hard place for an astronaut to set up camp. Here's what it might be like for an astronaut to live on the second planet from the sun.

Living on Planet Venus: Why It Would Be Hard (Infographic) If you thought Venus was the perfect vacation spot, better think again. See how some if its most hellish aspects would challenge astronauts in this infographic by Space.com's Karl Tate.

The 10 Weirdest Facts About Venus Venus is the brightest planet in our night sky, and one of the strangest. Take a look at some of the oddest facts about this weird world.

More About Venus:

- Planet Venus Facts: A Hot, Hellish & Volcanic Planet

- How Was Venus Formed?

- What is Venus Made Of?

- How Hot is Venus?

- Venus' Atmosphere: Composition, Climate and Weather

- How Far Away is Venus?

- How Big is Venus?

Tuesday, Feb. 10 – Earth's Moon

What Would It Be Like to Live on the Moon? From its lack of an atmosphere to dusty surface, the moon wouldn't be the most hospitable place for lunar colonizers to find themselves. Find out how they might be able to make the lunar surface a more cozy place to put down roots.

Living on the Moon: What It Would Be Like: Infographic How could you live on the moon? Space.com's Karl Tate explains some of the odds lunar explorers are up against in this infographic.

The Moon: 10 Surprising Lunar Facts Here are 10 amazing and surprising facts about the moon.

More about the moon :

- Moon Master: An Easy Quiz for Lunatics

- The Apollo Moon Landings: How They Worked (Infographic )

- How the Moon Evolved: A Photo Timeline

- Apollo Quiz: Test Your Moon Landing Memory

- What is the Moon Made Of?

- How Far is the Moon?

- What is the Temperature on the Moon?

Tuesday, Feb. 17 – Mars

What Would It Be Like to Live on Mars? Humans have long-dreamed about potentially colonizing the Red Planet, but what would it really take for humans to comfortably live on Mars?

How Living on Mars Could Challenge Colonists (Infographic ) What kind of challenges would humans face when trying to set up shop on Mars? The thin Martian atmosphere, harsh climate and other factors would make the Red Planet is a tough place for Martian explorers to live, but it could be possible.

More about Mars :

- Moons of Mars: Amazing Photos of Phobos and Deimos

- 10 Years on Mars: Smithsonian Celebrates Spirit, Opportunity Rovers (Photos

- Photos: Ancient Mars Lake Could Have Supported Life

- Mars Myths & Misconceptions: Quiz

- A 'Curiosity' Quiz: How Well Do You Know NASA's Newest Mars Rover?

- How Long Does It Take to Get to Mars?

Tuesday, Feb. 24 – Asteroid Belt

What Would It Be Like to Live On Dwarf Planet Ceres in the Asteroid Belt? The dwarf Planet Ceres may be round, but it doesn't have much of an atmosphere to speak of. What would it be like for human explorers if they visited this object in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter?

Living On Dwarf Planet Ceres in the Asteroid Belt (Infographic ) Learn more about what it might be like for human beings to live on the dwarf planet Ceres in the asteroid belt.

More about Ceres and the asteroid belt :

- Mysterious Bright Spots Shine on Dwarf Planet Ceres (Photos )

- Dwarf Planet Ceres Coming Into NASA Probe’s View

- NASA Finds Mysterious Bright Spot on Dwarf Planet Ceres: What Is It?

- The Asteroid Belt Explained: Space Rocks by the Millions (Infographic )

- The Greatest Mysteries of the Asteroid Belt

- Asteroid Basics: A Space Rock Quiz

Tuesday, March 3 – At Jupiter

What Would It Be Like to Live on Jupiter's Moon Europa? What would human explorers visiting Jupiter's icy moon Europa find when they get there? It's possible some form of life might already be there waiting for them.

Living On Europa Explained: Humans Might Not Be First: Infographic Europa is one of the most viable places in the solar system to hunt for life as we know it, but could humans find a way to settle it?

More about Jupiter and its moons :

- Planet Jupiter: Facts About Its Size, Moons and Red Spot

- Jupiter's Moons: Facts About the Largest Jovian Moons

- Europa: Facts About Jupiter's Icy Moon and Its Ocean

- Jupiter Quiz: Test Your Jovian Smarts

- How Far Away is Jupiter?

- Jupiter's Atmosphere & the Great Red Spot

- What is Jupiter Made Of?

- How Was Jupiter Formed?

- What is the Temperature of Jupiter?

- How Big is Jupiter?

- Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter

- Photos: The Galilean Moons of Jupiter

- Target: Jupiter — 9 Missions to the Solar System's Largest Planet

Tuesday, March 10 – At Saturn, the Ringed Planet

What Would It Be Like to Live on Saturn's Moons Enceladus and Titan? Saturn might not be a place where huamns could live, but its moons Titan and Enceladus might hold more hope for human colonists.

How Humans Could Live on Saturn's Moon Titan (Infographic) Saturn's moon Titan might be the most hospitable place in the solar system for humans to set up shop. What would it be like for a human explorer to hang out on Titan?

More about Saturn and its moons:

- Submarine Explores Saturn's Moon Titan In NASA Animation

- Planet Saturn: Facts About Saturn’s Rings, Moons & Size

- Saturn's Rings: Composition, Characteristics & Creation

- Saturn's Moons: Facts About the Ringed Planet's Satellites

- Enceladus: Saturn's Tiny, Shiny Moon

- How Big is Saturn?

- How Far Away is Saturn?

- Saturn's Atmosphere: All the Way Down

- What is Saturn Made Of?

- How Was Saturn Formed?

- Cassini-Huygens: Exploring Saturn's System

- Titan: Facts About Saturn's Largest Moon

Tuesday, March 17 – At Uranus

What Would It Be Like to Live on a Moon of Uranus? How would it feel to bounce around in the low gravity of Titania or Miranda? Find out what it might be like to colonize the moons of Uranus.

Living on Titania: Uranus' Moon Explained (Infographic ) Get a close-up look at what it could be like to live on Titania, Uranus' largest moon.

More about Uranus and its moons :

- Moons of Uranus: Facts About the Tilted Planet's Satellites

- How Big is Uranus?

- How Far is Uranus?

- Uranus' Atmosphere: Layers of Icy Clouds

- What is the Temperature of Uranus?

- What is Uranus Made Of?

- How Was Uranus Formed?

- Who Discovered Uranus (and How Do You Pronounce It)?

- Planet Uranus: Facts About Its Name, Moons and Orbit

- Inside Gas Giant Uranus (Infographic )

- Photos of Uranus, the Tilted Giant Planet

Tuesday, March 24 – At Neptune

What Would It Be Like to Live on Neptune's Moon Triton? While Neptune doesn't have much of a solid surface under its layers and layers of gas, its huge moon Triton might be a fun (and maybe difficult) place for humans to settle in the solar system.

Living on Triton: Neptune's Moon Explained (Infographic ) Triton could be an interesting place to live in the solar sytem. Learn more about what the first human settlers of the world could possibly find.

More about Neptune and its moons :

- Triton: Neptune's Odd Moon

- Neptune's Moons: 14 Discovered So Far

- How Big is Neptune?

- How Far Away is Neptune?

- Neptune's Atmosphere: Composition, Climate & Weather

- What is Neptune's Temperature?

- What is Neptune Made Of?

- How Was Neptune Formed?

- Planet Neptune: Facts About Its Orbit, Moons & Rings

- Photos of Neptune, The Mysterious Blue Planet

- Moons of Neptune: Giant Blue Planet's 14 Satellites Unmasked (Infographic )

- Inside Gas Giant Neptune

- Neptune Quiz: How Well Do You Know the Other Blue Planet?

Tuesday, March 31 – At Pluto

What Would It Be Like to Live on Pluto? How cold would human settlers on Pluto really be? The mysterious dwarf planet will be explored in closer detail when NASA 's New Horizons probe flys by the icy body in July.

Living on Pluto: Dwarf Planet Facts Explained (Infographic) Learn more about what it might be like to live on Pluto, if humans ever make it that far into the solar system.

More about Pluto and its moons :

- How NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto Works Infographic

- Pluto's 5 Moons Explained: How They Measure Up: Infographic

- Pluto: A Dwarf Planet Oddity: Infographic

- Inside Dwarf Planet Pluto

- Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons Mission in Pictures

- Photos of Pluto and Its Moons

- Lowell Observatory: Where Pluto Was Discovered

- Clyde Tombaugh: Astronomer Who Discovered Pluto How Big is Pluto?

- How Far Away is Pluto?

- Does Pluto Have an Atmosphere?

- How Cold is Pluto?

- What is Pluto Made Of?

- How Was Pluto Formed?

Tuesday, April 7 – Following a Comet

What It Would Be Like to Live On a Comet Living on comets requires great care — the gravity is so weak that you could easily jump off the frozen bodies and into space.

Living on a Comet: 'Dirty Snowball' Facts Explained: Infographic Halley's Comet, a dusty ball of ice and frozen gases, spends most of its time in the chilly outland of the solar system. See what it would be like to live on a comet in this infographic.

More about comets:

- Comets: Facts About The ‘Dirty Snowballs’ of Space

- Comet Quiz: Test Your Cosmic Knowledge

- Halley's Comet: Facts About the Most Famous Comet

- Comet 67P: Target of Rosetta Mission

- Best Close Encounters of the Comet Kind

- Photos: Spectacular Comet Views from Earth and Space

Saturday, May 9 – On a Strange New World

What Would It Be Like to Live on Alien Planet Kepler-186f? There are many unknowns regarding the potentially habitable exoplanet Kepler-186f, but it may have similar light (from its star) and gravity as Earth.

Living on an Alien Planet: Exoplanet Kepler-186f: Infographic At last humans are able to make educated guesses about what living on alien worlds might be like. Here's what we know about the alien planet Kepler-186f.

Earth-Size Planet Kepler-186f, a Possibly Habitable Alien World: Gallery The alien planet Kepler-186f is a planet only slightly larger than Earth orbiting inside the habitable zone of its red dwarf star. See images and photos of the Kepler-186f planet discovery in this Space.com gallery.

Exoplanet Kepler-186f: Earth-Size World Could Support Oceans and Life: Infographic A rocky planet that could have liquid water at its surface orbits a star 490 light-years away.

More resources on exoplanets:

- Exoplanets: Worlds Beyond Our Solar System

- Alien Planet Quiz: Are You an Exoplanet Expert?

- How Habitable Zones for Alien Planets and Stars Work: Infographic

- 10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life

- 6 Most Likely Places for Alien Life in the Solar System

Follow us @Spacedotcom , Facebook and Google+ .

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Tariq is the Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001, first as an intern and staff writer, and later as an editor. He covers human spaceflight, exploration and space science, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Managing Editor in 2009 and Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. In October 2022, Tariq received the Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting from the National Space Club Florida Committee. He is also an Eagle Scout (yes, he has the Space Exploration merit badge) and went to Space Camp four times as a kid and a fifth time as an adult. He has journalism degrees from the University of Southern California and New York University. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast with space historian Rod Pyle on the TWiT network . To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik .

Space pictures! See our space image of the day

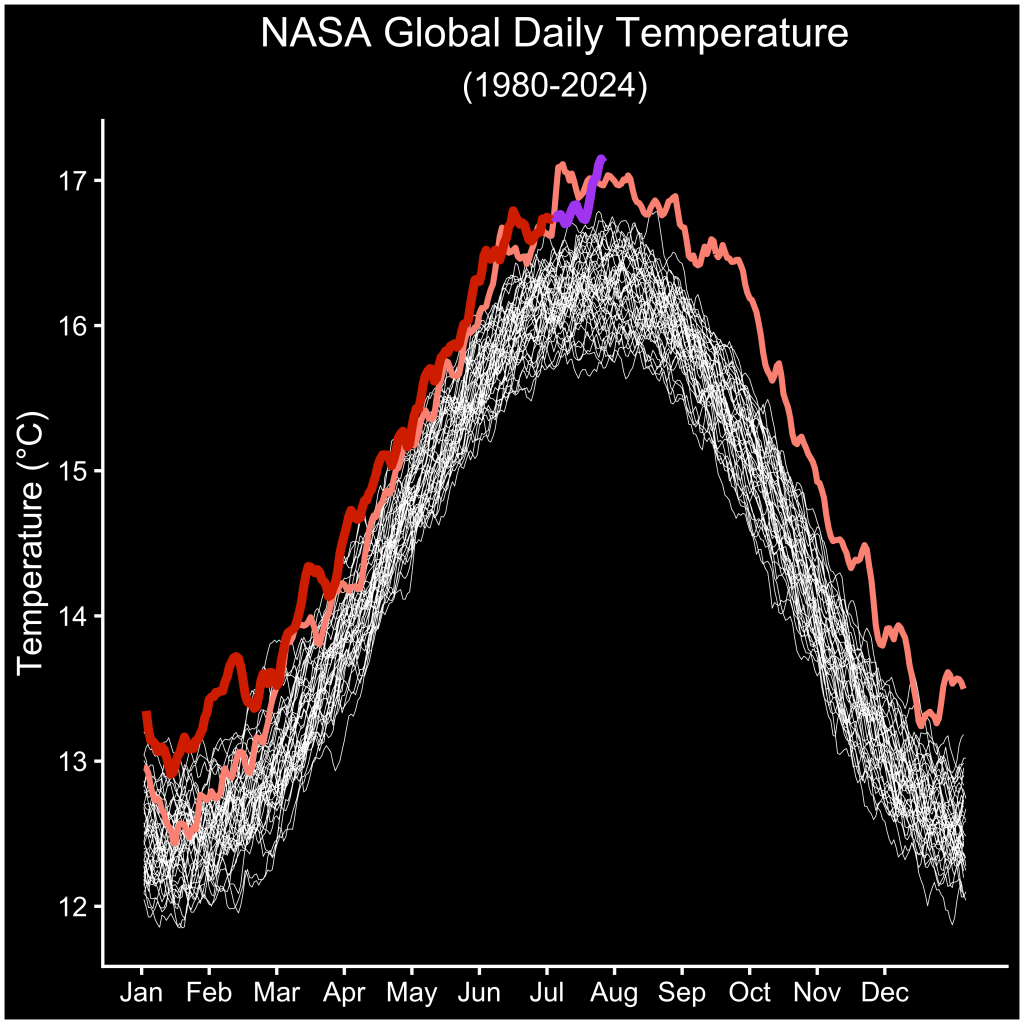

'The last 12 months have broken records like never before': Earth exceeds 1.5 C warming every month for entire year

Canadarm2 was not designed to catch spacecraft at the ISS. Now it's about to grab its 50th

Most Popular

- 2 The moon's thin atmosphere is made by constant meteorite bombardment

- 3 Test your space debris catching skills in new game released by Astroscale

- 4 Space pictures! See our space image of the day

- 5 Don't miss the 'unconventional' Blue Moon of August 2024

Life on Other Planets Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Article Review

Article discussions, works cited.

The article chosen for this part of the assignment is titled “The Extremely Halophilic Microorganisms, a Possible Model for Life on Other Planets,” written by Sergiu Fendrihan, and published in 2017 in Current Trends in Natural Sciences journal. The researchers have analyzed the microscopic life that exists in areas of extreme heat, where water supply exists in the form of salt lakes (Fendrihan 148). Such areas include the Dead Sea, located in the Middle East, as well as various smaller salt lakes found in Africa and Australia.

What these locations have in common is the extremity of conditions in which microorganisms have to exist. According to Fendrihan (148), there is a multitude of halophilic and halotolerant microorganisms inhabiting these areas, up to 159 different subspecies belonging to the Halobacteriaceae family. In addition, these organisms prove to be very resistant to other extremes, such as UV radiation, heat, and lack of nutrients necessary for other bacteria.

Due to the extreme resistance of these bacteria to various hazards, this study provides important data for discovering life on other planets and moons. Mars exhibits signs of water having been present on its surface. In addition, evidence of salty underground oceans has been found on the moons of Saturn and Jupiter (Enceladus and Europa).

Thus, studying halophilic microorganisms supports the possibility of the existence of life on planets previously deemed uninhabitable. Low requirements for water and nutrients as well as high resistance to the elements increases their chances of survival. Investigating these planets would enrich the existing knowledge of space and biology.

The article titled “Life on Mars: Exploration and Evidence” by Nola Taylor Redd provides cursory information about the state of research regarding life on Mars. The planet used to have large water deposits that were lost due to irradiation and exposure to harsh temperatures. The article suggests that life on Mars may still exist underneath the surface of the planet (Redd). Question: What exactly happened that altered Mars’s climate and caused it to lose so much of its water?

The second article titled “Aliens May Well Exist in a Parallel Universe, New Studies Find” by Brandon Specktor speculates about the existence of life in other dimensions. This article seems more like speculation rather than a contribution to the scientific community, as evidence of the existence of other dimensions is purely theoretical (Specktor). Question: If parallel universes exist, can they influence the events in our universe?

The third article titled “The Four Best Places for Life in Our Solar System” by Nicole Mortillaro provides a summary of four potential places for finding life. These planets and moons include Mars, Europa, Enceladus, and Titan (Mortillaro). This article outlines the requirements currently used to determine the feasibility of life on other planets. Question: Why did NASA restrict itself to studying Mars instead of sending a drone on one of the moons?

The fourth article written by Mike Wall speaks of the protective gravitational barrier of our solar system, which filters out charged particles coming from outside of the solar system. The existence of this protective field makes life on Earth possible (Wall). Studying it would help determine which systems can potentially harbor life and which could not. Question: Is the gravitational barrier unique to the Solar system alone?

The fifth article written by Lisa Kaspin-Powell explores the potential of non-H2O-based lifeforms existing on Titan. The article informs the readers that the elements found in Titan’s atmosphere can form cellular membranes similar to phospholipid molecular chains (Kaspin-Powell). Question: What other elements could potentially form cellular membranes?

The last article written by Seth Shostack provides a list of eight planets within the scope of our solar system that has the potential of harboring life. Aside from the 4 candidates mentioned in the article by Mortillaro, the article adds Earth, Venus, Ganymede, and Callisto, which show gravitational signs of possessing underground water (Shostak). Question: How is gravity related to the presence or absence of water?

Fendrihan, Sergiu. “The Extremely Halophilic Microorganisms, A Possible Model for Life on Other Planets.” Current Trends in Natural Sciences, vol. 6, no. 12, 2017, pp. 147-151.

Kaspin-Powell, Lisa. “Does Titan’s Hydrocarbon Soup Hold a Recipe for Life?” Astrobiology Magazine . 2018. Web.

Mortillaro, Nicole. “ The Four Best Places for Life in Our Solar System .” Global News . 2014. Web.

Redd, Nola Taylor. “ Life on Mars: Exploration and Evidence. ” Space. 2017. Web.

Shostak, Seth. “ 8 Worlds Where Life Might Exist. ” Space. 2006. Web.

Specktor, Brandon. “ Aliens May Well Exist in a Parallel Universe, New Studies Find. ” Space. 2018. Web.

Wall, Mike. “ NASA Will Launch a Probe to Study the Solar System’s Protective Bubble in 2024. ” Space. 2018. Web.

- Mystery Solar System: Planets Analysis

- Astronomy: the Nature of Life

- Astronomy of the Planets: Kepler's Law, Lunar Eclipse, Moon

- The Status of Pluto Needs to Remain as a Planet

- Prospects of finding life in Mars

- Astronomy and Mystery Solar System

- Solar System Colonization in Science Fiction vs. Reality

- Asteroid Fast Facts at the NASA Website

- Planet Mercury and Its Exploration

- General Features of Jupiter

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, May 29). Life on Other Planets. https://ivypanda.com/essays/life-on-other-planets/

"Life on Other Planets." IvyPanda , 29 May 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/life-on-other-planets/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Life on Other Planets'. 29 May.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Life on Other Planets." May 29, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/life-on-other-planets/.

1. IvyPanda . "Life on Other Planets." May 29, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/life-on-other-planets/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Life on Other Planets." May 29, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/life-on-other-planets/.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Sayaka Murata on Making Friends with Imaginary Aliens

"i’m an earthling, but once i’ve finished writing this essay i’ll go home to their planet.".

Translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori.

Ever since I was a child, I’ve felt closer to extraterrestrials than I have to humans.

I don’t remember when I first grasped the concept of “aliens.” I think I must already have known about them in the moment I first realized I was an Earthling. The picture books I read as a child, the manga I read in my friends’ homes, and the books I secretly borrowed from my brother’s bookshelf were full of aliens. In children’s animation too, there were lots of aliens who fell in love and traveled to Earth.

In one children’s book, a family of aliens moved to Earth and took on human appearance to avoid being discovered, wearing clothes, speaking human language, and getting to know everyone in their neighborhood. There were other books in which lots of aliens pretended to be human in order to escape detection, too. I felt a peculiar empathy for them. I, too, felt like I was pretending to be an Earthling at kindergarten and school.

I had always been an extremely withdrawn child. My mother and father worried whether I would be able to go to school like normal kids. My kindergarten teacher warned the elementary school that I was abnormally sensitive, a crybaby, and overly quiet, and I was given the seat closest to the teacher. The last thing I wanted was to become a foreign body in the class, so I imitated the other children around me, and tried hard to be as normal as possible and not stand out. School was brutal. Foreign bodies were quickly spotted, persecuted by the group, and made objects of ridicule. I wanted to be the most ordinary Earthling there was. In a way, I resembled those aliens who scrupulously kept up the act of being Earthlings so as not to be outed as aliens. The only difference was that I couldn’t escape the fact of actually being an Earthling. I didn’t have a home planet to go back to.

It was around this time that I met an imaginary alien. I was eight years old.

During the day, while I was living together with Earthlings, I kept getting hurt all over. However much I pretended to be an ordinary Earthling and made light conversation, during the time I spent with other Earthlings little cuts were being made all over my heart. Every few days, I had to hide in the toilet and cry until I threw up. By the time I went home and got into bed, I was covered in scars inside. And it was at this point that Imaginary Alien A came in through my window.

A and I fell in love right away. In a twinkling, my bed became a spaceship, and we flew through space every night. Before long my bed reached a planet that wasn’t Earth. There were a lot of imaginary aliens there, and I made lots of friends. I started going to that planet so that my soul could recuperate.

That mysterious planet was the only place in the entire world where I could exist with the same personality I was born with and not be disliked for it, where I could feel affection even without successfully acting the part of a human being. I would spend practically all my time there when I didn’t have to converse with Earthlings.

My first love, my first kiss, first date, first game of hide-and-seek, sleeping together like a family smiling at each other—all of this I experienced in my dealings with the imaginary aliens.

I’m still doing this now, at the age of 41. But I’ve never told anyone about my imaginary aliens before. If I’d been accused of escapism and laughed at, or ended up being “cured” and losing my imaginary aliens, I’d have died. Humans die when the only place where their soul can recuperate is destroyed. So I never told anyone, in order to survive.

I’m still living with them now. Even now my bed often flies through space. They sometimes tell me what they think of my novels. (Lots of aliens tell me, “This book is scary!”)

When I was a college student, I attended a poetry class. The teacher once said: “I used to think I was an alien. I felt that the trees swaying outside my window or the rustling of the leaves was a sign to me from outer space. I thought life was hard for me because I was an alien. I was waiting for a UFO to come and get me. There are surprisingly many people like that. Is there anyone here like me?”

At the teacher’s question, the classroom was hushed for a moment, but soon a few hands went up here and there.

I was surprised. But at the same time, it was like I finally understood. The alien in our mind is always going around rescuing Earthlings with nowhere to turn. I suddenly realized that the lives of many more children and adults than I’d thought were being sustained by invisible aliens.

True aliens (ones that exist in the real world) might possibly attack Earth tomorrow and smash it to pieces. But I believe that imaginary aliens have all along been interacting with us in a much deeper place in our hearts than our fellow humans.

As I read a book, I am sometimes unable to return from its imaginary world. When this happens, imaginary aliens always come to get me. They take me back to their planet. That’s where I live. Only when it’s necessary do we hold hands and set out for Earth together.

Earth is the only planet where I can touch reality. This is something that has come to affect me deeply. I’m an Earthling, but once I’ve finished writing this essay I’ll go home to their planet. That is the only place I’m able to sleep. Tonight, too, we will go to sleep holding hands. Ever since I was a child, they have always been in the deepest part of my psyche. A lot of people will be making love, playing, and sleeping with their imaginary aliens tonight, too. I believe this is a precious miracle that enables us to survive.

__________________________________

Earthlings by Sayaka Murata is available now via Grove Press.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Sayaka Murata

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Elizabeth Catte on Angry Twitter Conversations That Turn into Book Ideas

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Scientific researchers on a bat-collecting expedition in Sierra Leone. Photo by Simon Townley/Panos

There’s no planet B

The scientific evidence is clear: the only celestial body that can support us is the one we evolved with. here’s why.

by Arwen E Nicholson & Raphaëlle D Haywood + BIO

At the start of the 22nd century, humanity left Earth for the stars. The enormous ecological and climatic devastation that had characterised the last 100 years had led to a world barren and inhospitable; we had used up Earth entirely. Rapid melting of ice caused the seas to rise, swallowing cities whole. Deforestation ravaged forests around the globe, causing widespread destruction and loss of life. All the while, we continued to burn the fossil fuels we knew to be poisoning us, and thus created a world no longer fit for our survival. And so we set our sights beyond Earth’s horizons to a new world, a place to begin again on a planet as yet untouched. But where are we going? What are our chances of finding the elusive planet B, an Earth-like world ready and waiting to welcome and shelter humanity from the chaos we created on the planet that brought us into being? We built powerful astronomical telescopes to search the skies for planets resembling our own, and very quickly found hundreds of Earth twins orbiting distant stars. Our home was not so unique after all. The universe is full of Earths!

This futuristic dream-like scenario is being sold to us as a real scientific possibility, with billionaires planning to move humanity to Mars in the near future. For decades, children have grown up with the daring movie adventures of intergalactic explorers and the untold habitable worlds they find. Many of the highest-grossing films are set on fictional planets, with paid advisors keeping the science ‘realistic’. At the same time, narratives of humans trying to survive on a post-apocalyptic Earth have also become mainstream.

Given all our technological advances, it’s tempting to believe we are approaching an age of interplanetary colonisation. But can we really leave Earth and all our worries behind? No. All these stories are missing what makes a planet habitable to us . What Earth-like means in astronomy textbooks and what it means to someone considering their survival prospects on a distant world are two vastly different things. We don’t just need a planet roughly the same size and temperature as Earth; we need a planet that spent billions of years evolving with us. We depend completely on the billions of other living organisms that make up Earth’s biosphere. Without them, we cannot survive. Astronomical observations and Earth’s geological record are clear: the only planet that can support us is the one we evolved with. There is no plan B. There is no planet B. Our future is here, and it doesn’t have to mean we’re doomed.

D eep down, we know this from instinct: we are happiest when immersed in our natural environment. There are countless examples of the healing power of spending time in nature . Numerous articles speak of the benefits of ‘forest bathing’; spending time in the woods has been scientifically shown to reduce stress, anxiety and depression, and to improve sleep quality, thus nurturing both our physical and mental health. Our bodies instinctively know what we need: the thriving and unique biosphere that we have co-evolved with, that exists only here, on our home planet.

There is no planet B. These days, everyone is throwing around this catchy slogan. Most of us have seen it inscribed on an activist’s homemade placard, or heard it from a world leader. In 2014, the United Nations’ then secretary general Ban Ki-moon said: ‘There is no plan B because we do not have [a] planet B.’ The French president Emmanuel Macron echoed him in 2018 in his historical address to US Congress. There’s even a book named after it. The slogan gives strong impetus to address our planetary crisis. However, no one actually explains why there isn’t another planet we could live on, even though the evidence from Earth sciences and astronomy is clear. Gathering this observation-based information is essential to counter an increasingly popular but flawed narrative that the only way to ensure our survival is to colonise other planets.

The best-case scenario for terraforming Mars leaves us with an atmosphere we are incapable of breathing

The most common target of such speculative dreaming is our neighbour Mars. It is about half the size of Earth and receives about 40 per cent of the heat that we get from the Sun. From an astronomer’s perspective, Mars is Earth’s identical twin. And Mars has been in the news a lot lately, promoted as a possible outpost for humanity in the near future . While human-led missions to Mars seem likely in the coming decades, what are our prospects of long-term habitation on Mars? Present-day Mars is a cold, dry world with a very thin atmosphere and global dust storms that can last for weeks on end. Its average surface pressure is less than 1 per cent of Earth’s. Surviving without a pressure suit in such an environment is impossible. The dusty air mostly consists of carbon dioxide (CO 2 ) and the surface temperature ranges from a balmy 30ºC (86ºF) in the summer, down to -140ºC (-220ºF) in the winter; these extreme temperature changes are due to the thin atmosphere on Mars.

Despite these clear challenges, proposals for terraforming Mars into a world suitable for long-term human habitation abound. Mars is further from the Sun than Earth, so it would require significantly more greenhouse gases to achieve a temperature similar to Earth’s. Thickening the atmosphere by releasing CO 2 in the Martian surface is the most popular ‘solution’ to the thin atmosphere on Mars. However, every suggested method of releasing the carbon stored in Mars requires technology and resources far beyond what we are currently capable of. What’s more, a recent NASA study determined that there isn’t even enough CO 2 on Mars to warm it sufficiently.

Even if we could find enough CO 2 , we would still be left with an atmosphere we couldn’t breathe. Earth’s atmosphere contains only 0.04 per cent CO 2 , and we cannot tolerate an atmosphere high in CO 2 . For an atmosphere with Earth’s atmospheric pressure, CO 2 levels as high as 1 per cent can cause drowsiness in humans, and once we reach levels of 10 per cent CO 2 , we will suffocate even if there is abundant oxygen. The proposed absolute best-case scenario for terraforming Mars leaves us with an atmosphere we are incapable of breathing; and achieving it is well beyond our current technological and economic capabilities.

Instead of changing the atmosphere of Mars, a more realistic scenario might be to build habitat domes on its surface with internal conditions suitable for our survival. However, there would be a large pressure difference between the inside of the habitat and the outside atmosphere. Any breach in the habitat would rapidly lead to depressurisation as the breathable air escapes into the thin Martian atmosphere. Any humans living on Mars would have to be on constant high alert for any damage to their building structures, and suffocation would be a daily threat.

F rom an astronomical perspective, Mars is Earth’s twin; and yet, it would take vast resources, time and effort to transform it into a world that wouldn’t be capable of providing even the bare minimum of what we have on Earth. Suggesting that another planet could become an escape from our problems on Earth suddenly seems absurd. But are we being pessimistic? Do we just need to look further afield?

Next time you are out on a clear night, look up at the stars and choose one – you are more likely than not to pick one that hosts planets. Astronomical observations today confirm our age-old suspicion that all stars have their own planetary systems. As astronomers, we call these exoplanets. What are exoplanets like? Could we make any of them our home?

The majority of exoplanets discovered to date were found by NASA’s Kepler mission, which monitored the brightness of 100,000 stars over four years, looking for dips in a star’s light as a planet obscures it each time it completes an orbit around it.

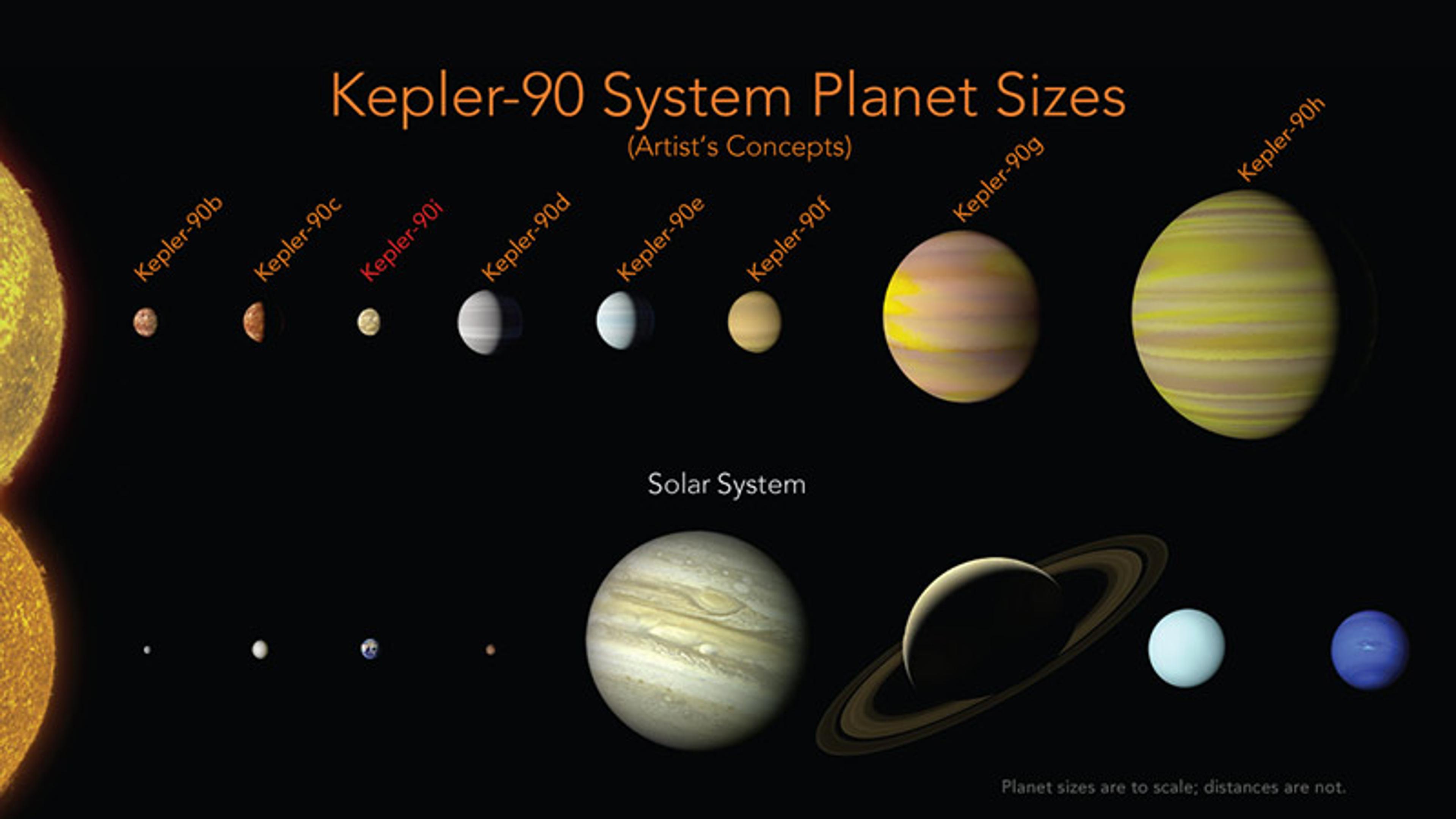

The solar system associated with star Kepler-90 has a similar configuration to our solar system with small planets found orbiting close to their star, and the larger planets found farther away. Courtesy NASA/Ames /Wendy Stenzel

Kepler observed more than 900 Earth-sized planets with a radius up to 1.25 times that of our world. These planets could be rocky (for the majority of them, we haven’t yet determined their mass, so we can only make this inference based on empirical relations between planetary mass and radius). Of these 900 or so Earth-sized planets, 23 are in the habitable zone. The habitable zone is the range of orbits around a star where a planet can be considered temperate : the planet’s surface can support liquid water (provided there is sufficient atmospheric pressure), a key ingredient of life as we know it. The concept of the habitable zone is very useful because it depends on just two astrophysical parameters that are relatively easy to measure: the distance of the planet to its parent star, and the star’s temperature. It’s worth keeping in mind that the astronomical habitable zone is a very simple concept and, in reality, there are many more factors at play in the emergence of life; for example, this concept does not consider plate tectonics , which are thought to be crucial to sustain life on Earth.

Planets with similar observable properties to Earth are very common: at least one in 10 stars hosts them

How many Earth-sized, temperate planets are there in our galaxy? Since we have discovered only a handful of these planets so far, it is still quite difficult to estimate their number. Current estimates of the frequency of Earth-sized planets rely on extrapolating measured occurrence rates of planets that are slightly bigger and closer to their parent star, as those are easier to detect. The studies are primarily based on observations from the Kepler mission, which surveyed more than 100,000 stars in a systematic fashion. These stars are all located in a tiny portion of the entire sky; so, occurrence rate studies assume that this part of the sky is representative of the full galaxy. These are all reasonable assumptions for the back-of-the-envelope estimate that we are about to make.

Several different teams carried out their own analyses and, on average, they found that roughly one in three stars (30 per cent) hosts an Earth-sized, temperate planet. The most pessimistic studies found a rate of 9 per cent, which is about one in 10 stars, and the studies with the most optimistic results found that virtually all stars host at least one Earth-sized, temperate planet, and potentially even several of them.

At first sight, this looks like a huge range in values; but it’s worth taking a step back and realising that we had absolutely no constraints whatsoever on this number just 20 years ago. Whether there are other planets similar to Earth is a question that we’ve been asking for millennia, and this is the very first time that we are able to answer it based on actual observations. Before the Kepler mission, we had no idea whether we would find Earth-sized, temperate planets around one in 10, or one in a million stars. Now we know that planets with similar observable properties to Earth are very common: at least one in 10 stars hosts these kinds of planets.

An artist’s concept shows exoplanet Kepler-1649c orbiting around its host red dwarf star. Courttesy NASA/Ames

Let’s now use these numbers to predict the number of Earth-sized, temperate planets in our entire galaxy. For this, let’s take the average estimate of 30 per cent, or roughly one in three stars. Our galaxy hosts approximately 300 billion stars, which adds up to 90 billion roughly Earth-sized, roughly temperate planets. This is a huge number, and it can be very tempting to think that at least one of these is bound to look exactly like Earth.

One issue to consider is that other worlds are at unimaginable distances from us. Our neighbour Mars is on average 225 million kilometres (about 140 million miles) away. Imagine a team of astronauts travelling in a vehicle similar to NASA’s robotic New Horizons probe, one of humankind’s fastest spacecrafts – which flew by Pluto in 2015. With New Horizons’ top speed of around 58,000 kph, it would take at least 162 days to reach Mars. Beyond our solar system, the closest star to us is Proxima Centauri, at a distance of 40 trillion kilometres. Going in the same space vehicle, it would take our astronaut crew 79,000 years to reach planets that might exist around our nearest stellar neighbour.

S till, let’s for a moment optimistically imagine that we find a perfect Earth twin: a planet that really is exactly like Earth. Let’s imagine that some futuristic form of technology exists, ready to whisk us away to this new paradise. Keen to explore our new home, we eagerly board our rocket, but on landing we soon feel uneasy. Where is the land? Why is the ocean green and not blue? Why is the sky orange and thick with haze? Why are our instruments detecting no oxygen in the atmosphere? Was this not supposed to be a perfect twin of Earth?

As it turns out, we have landed on a perfect twin of the Archean Earth, the aeon during which life first emerged on our home world. This new planet is certainly habitable: lifeforms are floating around the green, iron-rich oceans, breathing out methane that is giving the sky that unsettling hazy, orange colour. This planet sure is habitable – just not to us . It has a thriving biosphere with plenty of life, but not life like ours. In fact, we would have been unable to survive on Earth for around 90 per cent of its history; the oxygen-rich atmosphere that we depend on is a recent feature of our planet.

The earliest part of our planet’s history, known as the Hadean aeon, begins with the formation of the Earth. Named after the Greek underworld due to our planet’s fiery beginnings, the early Hadean would have been a terrible place with molten lava oceans and an atmosphere of vaporised rock. Next came the Archean aeon, beginning 4 billion years ago, when the first life on Earth flourished. But, as we just saw, the Archean would be no home for a human. The world where our earliest ancestors thrived would kill us in an instant. After the Archean came the Proterozoic, 2.5 billion years ago. In this aeon, there was land, and a more familiar blue ocean and sky. What’s more, oxygen finally began to accumulate in the atmosphere. But let’s not get too excited: the level of oxygen was less than 10 per cent of what we have today. The air would still have been impossible for us to breathe. This time also experienced global glaciation events known as snowball Earths, where ice covered the globe from poles to equator for millions of years at a time. Earth has spent more of its time fully frozen than the length of time that we humans have existed.

We would have been incapable of living on our planet for most of its existence

Earth’s current aeon, the Phanerozoic, began only around 541 million years ago with the Cambrian explosion – a period of time when life rapidly diversified. A plethora of life including the first land plants, dinosaurs and the first flowering plants all appeared during this aeon. It is only within this aeon that our atmosphere became one that we can actually breathe. This aeon has also been characterised by multiple mass extinction events that wiped out as much as 90 per cent of all species over short periods of time. The factors that brought on such devastation are thought to be a combination of large asteroid impacts, and volcanic, chemical and climate changes occurring on Earth at the time. From the point of view of our planet, the changes leading to these mass extinctions are relatively minor. However, for lifeforms at the time, such changes shattered their world and very often led to their complete extinction.

Looking at Earth’s long history, we find that we would have been incapable of living on our planet for most of its existence. Anatomically modern humans emerged less than 400,000 years ago; we have been around for less than 0.01 per cent of the Earth’s story. The only reason we find Earth habitable now is because of the vast and diverse biosphere that has for hundreds of millions of years evolved with and shaped our planet into the home we know today. Our continued survival depends on the continuation of Earth’s present state without any nasty bumps along the way. We are complex lifeforms with complex needs. We are entirely dependent on other organisms for all our food and the very air we breathe. The collapse of Earth’s ecosystems is the collapse of our life-support systems. Replicating everything Earth offers us on another planet, on timescales of a few human lifespans, is simply impossible.

Some argue that we need to colonise other planets to ensure the future of the human race. In 5 billion years, our Sun, a middle-aged star, will become a red giant, expanding in size and possibly engulfing Earth. In 1 billion years, the gradual warming of our Sun is predicted to cause Earth’s oceans to boil away. While this certainly sounds worrying, 1 billion years is a long, long time. A billion years ago, Earth’s landmasses formed the supercontinent Rodinia, and life on Earth consisted in single-celled and small multicellular organisms. No plants or animals yet existed. The oldest Homo sapiens remains date from 315,000 years ago, and until 12,000 years ago all humans lived as hunter-gatherers.

The industrial revolution happened less than 500 years ago. Since then, human activity in burning fossil fuels has been rapidly changing the climate, threatening human lives and damaging ecosystems across the globe. Without rapid action, human-caused climate change is predicted to have devastating global consequences within the next 50 years. This is the looming crisis that humanity must focus on. If we can’t learn to work within the planetary system that we evolved with, how do we ever hope to replicate these deep processes on another planet? Considering how different human civilisations are today from even 5,000 years ago, worrying about a problem that humans may have to tackle in a billion years is simply absurd. It would be far simpler to go back in time and ask the ancient Egyptians to invent the internet there and then. It’s also worth considering that many of the attitudes towards space colonisation are worryingly close to the same exploitative attitudes that have led us to the climate crisis we now face.

Earth is the home we know and love not because it is Earth-sized and temperate. No, we call this planet our home thanks to its billion-year-old relationship with life. Just as people are shaped not only by their genetics, but by their culture and relationships with others, planets are shaped by the living organisms that emerge and thrive on them. Over time, Earth has been dramatically transformed by life into a world where we, humans, can prosper. The relationship works both ways: while life shapes its planet, the planet shapes its life. Present-day Earth is our life-support system, and we cannot live without it.

While Earth is currently our only example of a living planet, it is now within our technological reach to potentially find signs of life on other worlds. In the coming decades, we will likely answer the age-old question: are we alone in the Universe? Finding evidence for alien life promises to shake the foundations of our understanding of our own place in the cosmos. But finding alien life does not mean finding another planet that we can move to. Just as life on Earth has evolved with our planet over billions of years, forming a deep, unique relationship that makes the world we see today, any alien life on a distant planet will have a similarly deep and unique bond with its own planet. We can’t expect to be able to crash the party and find a warm welcome.

Living on a warming Earth presents many challenges. But these pale in comparison with the challenges of converting Mars, or any other planet, into a viable alternative. Scientists study Mars and other planets to better understand how Earth and life formed and evolved, and how they shape each other. We look to worlds beyond our horizons to better understand ourselves. In searching the Universe, we are not looking for an escape to our problems: Earth is our unique and only home in the cosmos. There is no planet B.

Human reproduction

When babies are born, they cry in the accent of their mother tongue: how does language begin in the womb?

Darshana Narayanan

Politics and government

Governing for the planet

Nation-states are no longer fit for purpose to create a habitable future for humans and nature. Which political system is?

Jonathan S Blake & Nils Gilman

We are not machines

Welcome to the new post-genomic biology: a transformative era in need of fresh metaphors to understand how life works

Philip Ball

Progress and modernity

In praise of magical thinking

Once we all had knowledge of how to heal ourselves using plants and animals. The future would be sweeter for renewing it

Anna Badkhen

History of technology

Learning to love monsters

Windmills were once just machines on the land but now seem delightfully bucolic. Could wind turbines win us over too?

Stephen Case

History of science

His radiant formula

Stephen Hawking’s greatest legacy – a simple little equation now 50 years old – revealed a shocking aspect of black holes

Roger Highfield

Suggested Searches

- Climate Change

- Expedition 64

- Mars perseverance

- SpaceX Crew-2

- International Space Station

- View All Topics A-Z

Humans in Space

Earth & climate, the solar system, the universe, aeronautics, learning resources, news & events.

NASA Scientists on Why We Might Not Spot Solar Panel Technosignatures

NASA Embraces Streaming Service to Reach, Inspire Artemis Generation

Hubble Spies a Diminutive Galaxy

- Search All NASA Missions

- A to Z List of Missions

- Upcoming Launches and Landings

- Spaceships and Rockets

- Communicating with Missions

- James Webb Space Telescope

- Hubble Space Telescope

- Why Go to Space

- Commercial Space

- Destinations

- Living in Space

- Explore Earth Science

- Earth, Our Planet

- Earth Science in Action

- Earth Multimedia

- Earth Science Researchers

- Pluto & Dwarf Planets

- Asteroids, Comets & Meteors

- The Kuiper Belt

- The Oort Cloud

- Skywatching

- The Search for Life in the Universe

- Black Holes

- The Big Bang

- Dark Energy & Dark Matter

- Earth Science

- Planetary Science

- Astrophysics & Space Science

- The Sun & Heliophysics

- Biological & Physical Sciences

- Lunar Science

- Citizen Science

- Astromaterials

- Aeronautics Research

- Human Space Travel Research

- Science in the Air

- NASA Aircraft

- Flight Innovation

- Supersonic Flight

- Air Traffic Solutions

- Green Aviation Tech

- Drones & You

- Technology Transfer & Spinoffs

- Space Travel Technology

- Technology Living in Space

- Manufacturing and Materials

- Science Instruments

- For Kids and Students

- For Educators

- For Colleges and Universities

- For Professionals

- Science for Everyone

- Requests for Exhibits, Artifacts, or Speakers

- STEM Engagement at NASA

- NASA's Impacts

- Centers and Facilities

- Directorates

- Organizations

- People of NASA

- Internships

- Our History

- Doing Business with NASA

- Get Involved

NASA en Español

- Aeronáutica

- Ciencias Terrestres

- Sistema Solar

- All NASA News

- Video Series on NASA+

- Newsletters

- Social Media

- Media Resources

- Upcoming Launches & Landings

- Virtual Events

- Sounds and Ringtones

- Interactives

- STEM Multimedia

MESSENGER – From Setbacks to Success

What’s New With the Artemis II Crew

Food in Space

NASA Offers Virtual Activities for 21st Northrop Grumman Resupply Mission

NASA Data Shows July 22 Was Earth’s Hottest Day on Record

NASA Returns to Arctic Studying Summer Sea Ice Melt

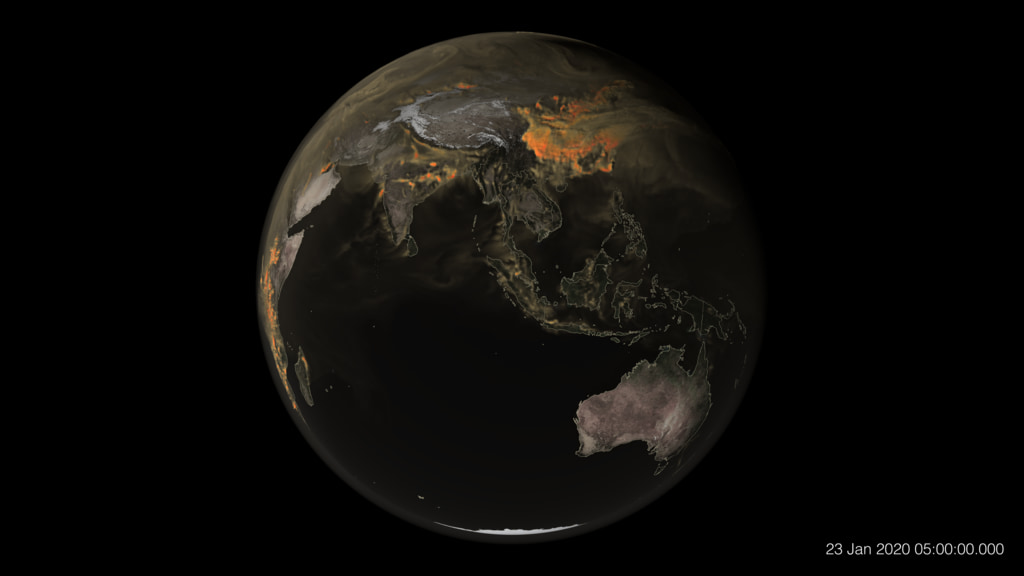

Watch Carbon Dioxide Move Through Earth’s Atmosphere

Amendment 37: DRAFT F.11 Stand-Alone Landing Site-Agnostic Payloads and Research Investigations on the Surface of the Moon released for community comment.

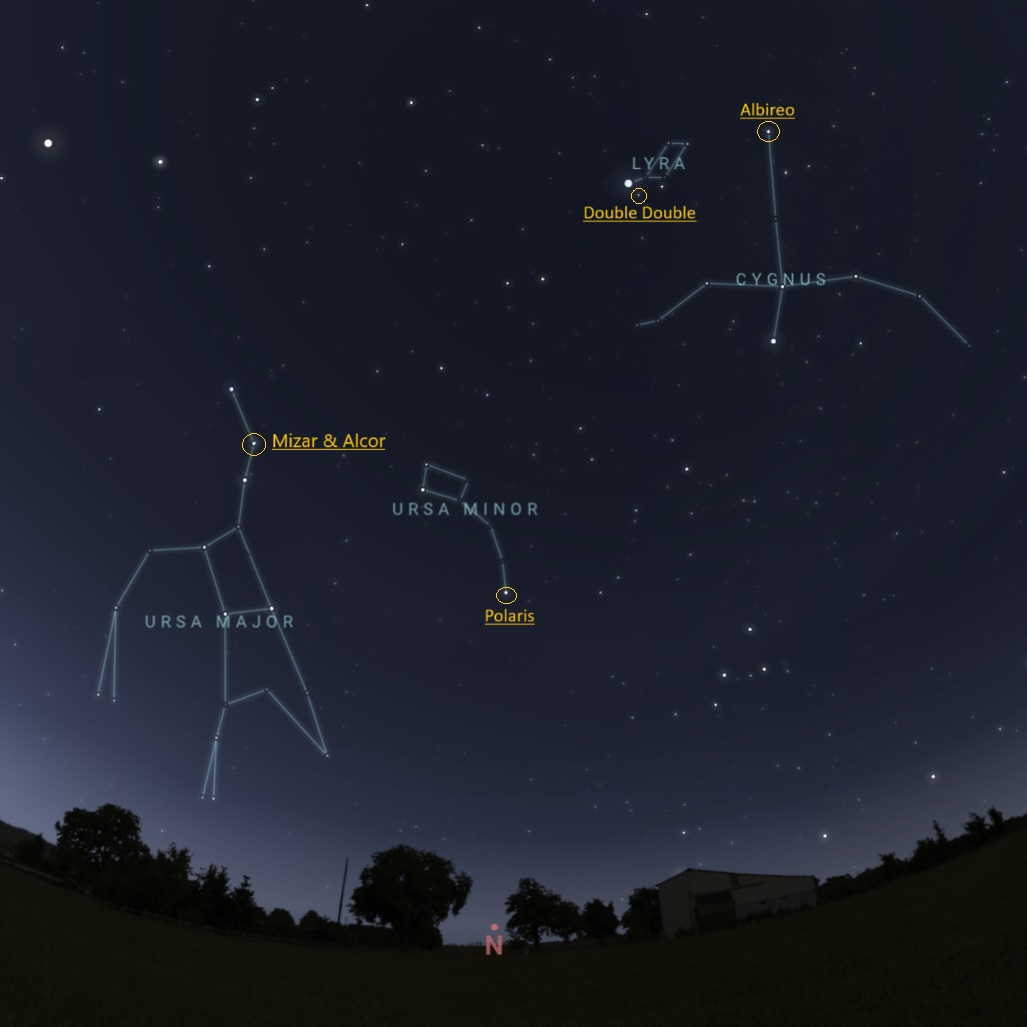

August’s Night Sky Notes: Seeing Double

Repair Kit for NASA’s NICER Mission Heading to Space Station

LIVE: NASA is with you from Oshkosh

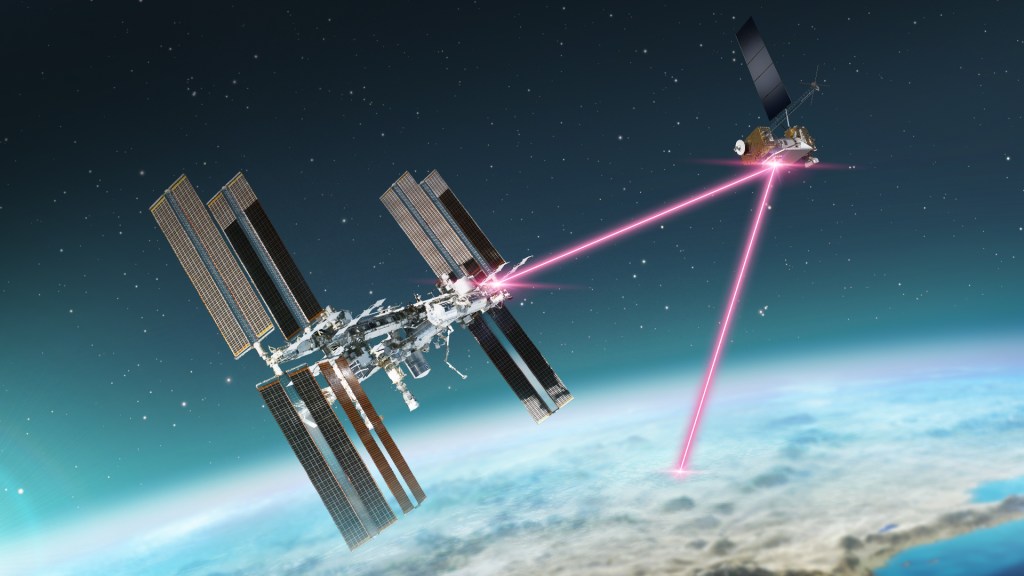

NASA Streams First 4K Video from Aircraft to Space Station, Back

NASA Ames to Host Supercomputing Resources for UC Berkeley Researchers

Former Space Communications, Navigation Interns Pioneer NASA’s Future

NASA Releases First Integrated Ranking of Civil Space Challenges

Three NASA Interns Expand Classroom Access to NASA Data

NASA Johnson Dedicates Dorothy Vaughan Center to Women of Apollo

NASA’s First-Ever Quantum Memory Made at Glenn Research Center

A Picture-Perfect Portrait: Eliza Hoffman’s Take on Dorothy Vaughan

There Are No Imaginary Boundaries for Dr. Ariadna Farrés-Basiana

Astronauta de la NASA Frank Rubio

Diez maneras en que los estudiantes pueden prepararse para ser astronautas

Finding life beyond earth is within reach, nasa webb telescope team.

Many scientists believe we are not alone in the universe. It’s probable, they say, that life could have arisen on at least some of the billions of planets thought to exist in our galaxy alone — just as it did here on planet Earth. This basic question about our place in the Universe is one that may be answered by scientific investigations. What are the next steps to finding life elsewhere?

Experts from NASA and its partner institutions addressed this question on July 14, at a public talk held at NASA Headquarters in Washington. They outlined NASA’s roadmap to the search for life in the universe, an ongoing journey that involves a number of current and future telescopes. Watch the video of the event:

“Sometime in the near future, people will be able to point to a star and say, ‘that star has a planet like Earth’,” says Sara Seager, professor of planetary science and physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “Astronomers think it is very likely that every single star in our Milky Way galaxy has at least one planet.”

NASA’s quest to study planetary systems around other stars started with ground-based observatories, then moved to space-based assets like the Hubble Space Telescope , the Spitzer Space Telescope , and the Kepler Space Telescope . Today’s telescopes can look at many stars and tell if they have one or more orbiting planets. Even more, they can determine if the planets are the right distance away from the star to have liquid water, the key ingredient to life as we know it.

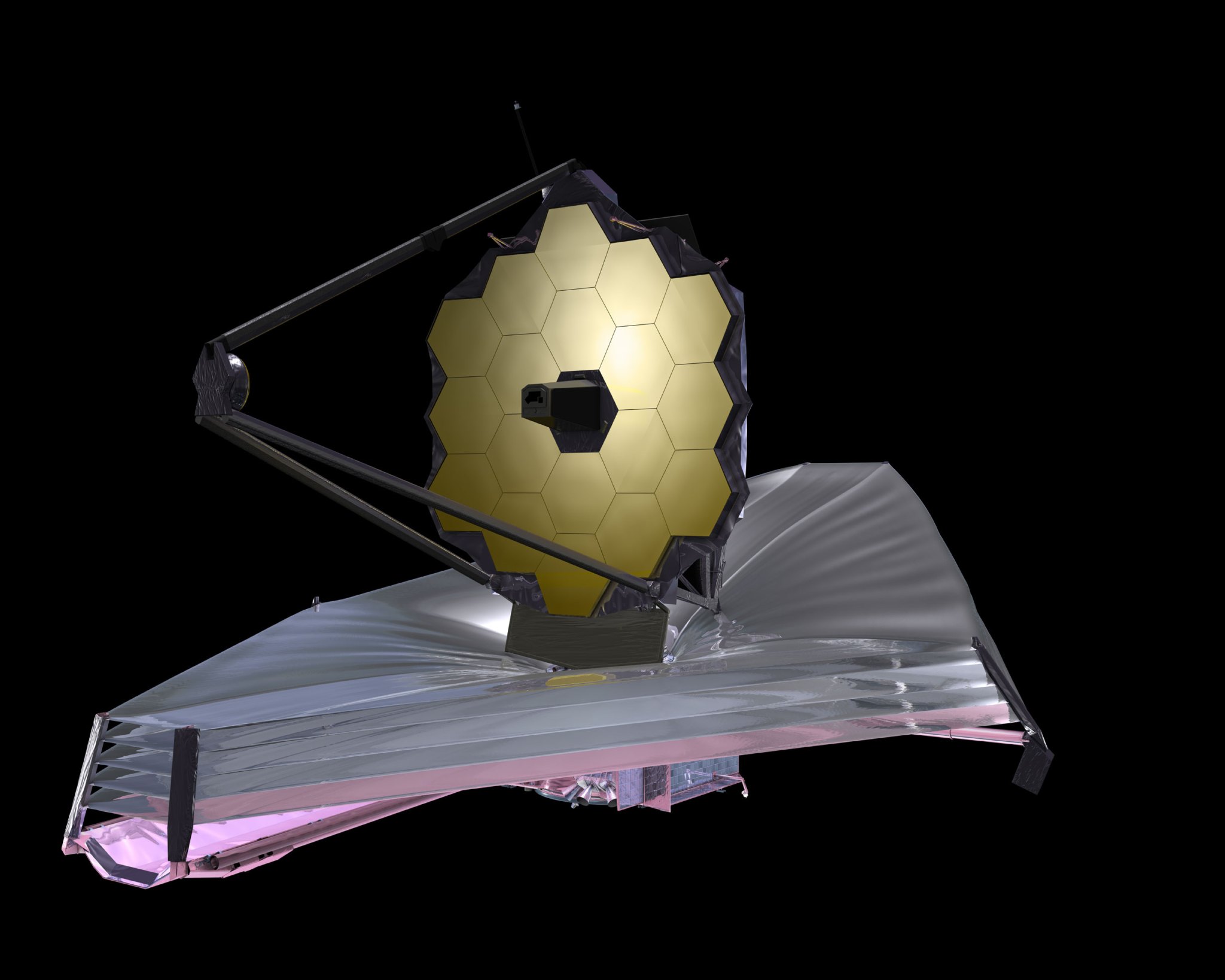

The NASA roadmap will continue with the launch of the Transiting Exoplanet Surveying Satellite (TESS) in 2017, the James Webb Space Telescope (Webb Telescope) in 2018, and perhaps the proposed Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope – Astrophysics Focused Telescope Assets (WFIRST-AFTA) early in the next decade. These upcoming telescopes will find and characterize a host of new exoplanets — those planets that orbit other stars — expanding our knowledge of their atmospheres and diversity. The Webb telescope and WFIRST-AFTA will lay the groundwork, and future missions will extend the search for oceans in the form of atmospheric water vapor and for life as in carbon dioxide and other atmospheric chemicals, on nearby planets that are similar to Earth in size and mass, a key step in the search for life.

“This technology we are using to explore exoplanets is real,” said John Grunsfeld, astronaut and associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “The James Webb Space Telescope and the next advances are happening now. These are not dreams — this is what we do at NASA.”

Since its launch in 2009, Kepler has dramatically changed what we know about exoplanets, finding most of the more than 5,000 potential exoplanets, of which more than 1700 have been confirmed. The Kepler observations have led to estimates of billions of planets in our galaxy, and shown that most planets within one astronomical unit are less than three times the diameter of Earth. Kepler also found the first Earth-size planet to orbit in the “habitable zone” of a star, the region where liquid water can pool on the surface.

“What we didn’t know five years ago is that perhaps 10 to 20 percent of stars around us have Earth-size planets in the habitable zone,” says Matt Mountain, director and Webb telescope scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore. “It’s within our grasp to pull off a discovery that will change the world forever. It is going to take a continuing partnership between NASA, science, technology, the U.S. and international space endeavors, as exemplified by the James Webb Space Telescope, to build the next bridge to humanity’s future.”

This decade has seen the discovery of more and more super Earths, which are rocky planets that are larger and heftier than Earth. Finding smaller planets, the Earth twins, is a tougher challenge because they produce fainter signals. Technology to detect and image these Earth-like planets is being developed now for use with the future space telescopes. The ability to detect alien life may still be years or more away, but the quest is underway.

Said Mountain, “Just imagine the moment, when we find potential signatures of life. Imagine the moment when the world wakes up and the human race realizes that its long loneliness in time and space may be over — the possibility we’re no longer alone in the universe.”

What Possible Life Forms Could Exist on Other Planets: A Historical Overview

- Defining Life

- Published: 26 February 2010

- Volume 40 , pages 195–202, ( 2010 )

Cite this article

- Florence Raulin Cerceau 1

1123 Accesses

2 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Speculations on living beings existing on other planets are found in many written works since the Frenchman Bernard de Fontenelle spoke to the Marquise about the inhabitants of the solar system in his Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes ( 1686 ). It was an entertainment used to teach astronomy more than real considerations about the habitability of our solar system, but it opened the way to some reflections about the possible life forms on other planets. The nineteenth century took up this idea again in a context of planetary studies showing the similarities as well as the differences of the celestial bodies orbiting our Sun. Astronomers attempted to look deeper into the problem of habitability such as Richard Proctor or Camille Flammarion, also well-known for their fine talent in popular writings. While the Martian canals controversy was reaching its height, they imagined how the living forms dwelling in other planets could be. Nowadays, no complex exo-life is expected to have evolved in our solar system. However, the famous exobiologist Carl Sagan and later other scientists, formulated audacious ideas about other forms of life in the light of recent discoveries in planetology. Through these few examples, this paper underlines the originality of each author’s suggestions and the evolution and contrast of ideas about the possible life forms in the universe.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Relationship Between the Origins of Life on Earth and the Possibility of Life on Other Planets: A Nineteenth-Century Perspective

Astrobiology and Planetary Sciences in Mexico

Astrobiology, the Emergence of Life, and Planetary Exploration

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As far back as Antiquity, philosophers and men of science (Anaximander, Lucretius) studied the subject of life on other worlds. Later, physicists and astronomers such as Huygens or Newton have dwelt upon the same fascinating theme. The history of the plurality of worlds can’t forget the dissenting Dominican Giordano Bruno who was burnt at the stake in 1600 for, among other things, having supported the idea of infinity of worlds.

The plurality of worlds became popular when heliocentrism supplanted geocentrism, since the Earth could be no more considered as the center of the universe. Other worlds could be regarded as inhabited and speculations could be put forward on the model of creatures living on our planet.

With the development of astronomical techniques of observation, astronomers took an active interest in a new concept named “habitability”, dealing with the conditions of planetary environment combined with the possibilities for life to exist (Raulin Cerceau 2006 ). Comparisons were made between the other planets of the solar system and the Earth. It was the time of the first maps of Mars and the idea of a Martian life was expanding, from the canals controversy to the hypothesis of a Martian vegetation. Life was supposed to be possible nearly everywhere in the solar system. Limitations came from spectroscopy when astronomers realized that the atmospheric conditions—more or less suitable for life—on each planet were a determining factor. Of course, our age of space exploration led to a new definition of “habitability” and to reconsider the way to conceive the life forms likely to exist on various planetary environments.

Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle’s Plurality of Worlds

The French philosopher and writer Fontenelle (1657–1757) was famous for popularizing science and philosophy in a lively and elegant way. His Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes (Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds) (Fontenelle 1686 ) offered an explanation of the Copernicus’ heliocentric model of the universe in popular language. It was an immediate success. The book presented a series of conversations between a gallant philosopher (Fontenelle himself) and a Marchioness. The question about life on other worlds was raised and one of the main problems to be discussed was the following one: are the inhabitants of these planets like us or are they quite different?

Here is Fontenelle’s view. The inhabitants of the solar system are very different from one planet to another. On the Moon, where there is no water, no cloud, no protection against the Sun, the Selenites live beneath the surface in deep wells that perhaps could be seen through our telescopes. But the Marchioness looks very doubtful about the humming and hawing coming from his pleasant teacher concerning the description of life on the Moon: “it’s a lot of ignorance based on very little science”, she asserts. She has the feeling that Fontenelle is going to populate all the planets and she is at once overwhelmed by the “unlimited number of inhabitants likely to be on all these planets”. How can we imagine these planet dwellers, so various indeed if nature is opposed to repetitions? Fontenelle enjoys himself imagining that differences increase as the planets become more and more distant from the Sun.

For instance, on Venus, where heat and sunlight are more intense than on our planet, the climate conditions are very favorable to love affairs. The Venusians (named Céladons and Silvandres ) are clever and lively but all are infertile, except a very little number of procreators and the Queen who is extremely prolific. Millions of children are descended from her and this fact is quite similar to the bee kingdom on the Earth. The Marchioness looks very amazed!

Fontenelle spends very little time on the case of Mars, a planet which seems to be very similar to the Earth. According to him, Mars has nothing special and it’s not worth mentioning it.

Jupiter, Saturn and their moons seem to be more interesting and are worthy of being habitable. The inhabitants of Saturn, very far from the Sun, are very wise and phlegmatic. They never laugh and they need a whole day to answer the least question one asks them. What about far away in the universe? All the stars are so many suns lighting up a world. Fontenelle’s plurality of worlds seems finally to be so probable that the Marchioness appears disheartened by such a diversity of living beings…

Fontenelle offers to the reader a very broad plurality of living worlds. Its merit is to have been the first to popularize in a pleasant style the idea of diversity of life in the universe.

Camille Flammarion’s Diversity of Beings

“Terrestrial life is not the type of other lives. An unlimited diversity reigns over the universe”. (Flammarion 1891 )

The French astronomer Camille Flammarion (1842–1925) founded the Juvisy Observatory (France) in 1883 and the Société Astronomique de France (SAF) in 1887. He was a very prolific writer. Above all, he was well-known for his Pluralité des Mondes habités (Plurality of Inhabited Worlds) published in 1862, when he was only twenty years old. This book, translated in many languages, explained the conditions of habitability of earthlike celestial bodies discussed from the astronomical, physiological and philosophical viewpoint (Flammarion 1862 ). A comparative study of the planets of our solar system led him to state that “the Earth was, considering its physical characteristics, a planet of medium kind, without anything remarkable.” Following this idea, life would have been present everywhere in the solar system. In the chapter entitled Humanity in the Universe , Flammarion studied the case of other humanities likely to exist on other worlds, while raising the question of anthropomorphism.

Most of Flammarion’s successful books dealt with the question of planet habitability seen from the scientific angle. Sometimes however, Flammarion devoted himself to fiction. A few of his narratives were turned towards the description of imaginary worlds though punctuated with scientific observations and philosophical reflections. Such was the case in Uranie (Urania) published in 1891, in which the narrator met the statue of the heavenly Muse Urania and felt under her spell. It gave rise to a debate on the diversity of life in the universe, as follows.

One night, Urania took her admirer off towards a sidereal journey to visit a selection of other worlds filling the universe. She wanted to show him some of astronomical truths, invisible to anyone else on Earth. While approaching other suns, the narrator was captivated by the amazing diversity of the living beings populating the planetary systems. None of them had an earthly human form. The Muse behaved like a teacher of the plurality of worlds:

“To be in a condition to understand the infinite diversity displayed in the different phases of creation, it is necessary to cast aside all terrestrial feelings and ideas.” As examples of this diversity, the Muse asserted that “life is earthly on the Earth, Martian on Mars, Saturnian on Saturn, Neptunian on Neptune,—that is to say, appropriate to each habitat.” (Flammarion 1891 )

On one world, the human beings enjoyed the organic faculty of those insects endowing the capacity to sleep in a chrysalis state and to metamorphose themselves into winged butterflies. On another world, the inhabitants had a sixth sense which might be called magneto-telegraphic, by virtue of which the thought became outwardly manifest and could be read upon a feature which occupied the same place as a forehead. With such a magnificence of the spectacle, the Muse wanted to demonstrate that astronomy inevitably led to the study of universal and eternal life and that anthropomorphism had to be excluded from this context.

In this book, Flammarion made use of imagination to make the reader aware of the problem of life’s diversity on other worlds. However, his aim was obviously scientific even if the narrative form was poetic. Contrary to most of his contemporaries, he dismissed any form of anthropomorphism when he described the other inhabitants of the universe. Other worlds meant other conditions of habitability and necessarily other forms of beings: “Beings are born on each world in close correlation with its physiological state” (Flammarion 1865 ). The plurality of worlds supported by Flammarion was then also a plurality of life forms.

Richard Proctor’s Planetary Worlds

The British astronomer Richard A. Proctor (1837–1888) is best remembered for having produced one of the earliest maps of Mars in 1867 and for having written many popular books. Among them, Other Worlds Than Ours, The Plurality of Worlds Studied Under The Light of Recent Scientific Researches , published for the first time in 1870, immediately attracted attention not only of the scientific world but also of a very wide audience. Proctor used a poetical description to show what astronomy taught us about the Sun and its planets. He also discussed the probability that other worlds could be inhabited.

However, according to Proctor, difficulties arise when the discussion comes to the possible forms of life (Proctor 1870 ). Habitability would be the key argument able to answer this question, even if it is quite hard to know the conditions under which these beings could live. In Proctor’s opinion, habitability could nevertheless be defined in considering analogy with the Earth, i.e. parameters resembling those existing upon our planet. Proctor also integrated the Darwinian theory of biological evolution into his reasoning in order to see if life would be possible in very exotic environments. He underlined that we have learned from Darwin’s theory that slight differences between two regions of the Earth could lead to life forms differently adapted. Moreover, there are places on the Earth where species belonging to other regions would quickly perish. He deduced from what our planet taught us about evolution that other worlds could be the abode of living creatures but they would support life in other ways.

Proctor studied the habitability of every planet of the solar system. He suggested that the existence of organized forms of life depended on the conditions supposed to have an effect on the planetary surface, such as climate, seasons, atmosphere, geology, gravity. For instance, the physical conditions of Venus—size, location in the solar system, density, rotation, seasons, heat and light received from the Sun- seemed to show very close resemblances to the Earth. Arguments coming from analogy allowed him to conclude that this planet could be inhabited. Proctor assumed that Venus could be the abode of creatures as far advanced in the scale of evolution as any existing upon the Earth.

However, it clearly appeared that the best candidate to be the abode of life was Mars, “the miniature of our Earth” (Proctor 1870 ). Of course, at that time, among all the celestial bodies observed in our solar system, Mars had been examined more minutely and under more favorable circumstances than any object except the Moon. The surface of Mars was supposed to be covered by oceans and continents (the darker regions were assumed to be seas and the lighter parts continents). The Martian geography—or areography —was intensively studied and seemed to demonstrate the presence of a vast equatorial zone of continents, seas and straits: no doubt remained as to the interpretation of the features looking like land or water. Mars seemed to offer very strong analogies with the Earth and everything appeared possible regarding the forms of life likely to be on its surface. With seasons equivalent to terrestrial ones, water vapor in the atmosphere and forms of vegetation growing abundantly, Proctor’s Martian world was perfectly fitted for complex life.

Proctor admitted also life on Jupiter. The giant planet might be inhabited by “the most favored races existing throughout the whole range of the solar system” (Proctor 1870 ), thanks to the very symmetry and perfection of the system which circles round it. It had been proposed at that time that the huge dimensions of Jupiter and its distance from the sun led to the conclusion that Jovians must be of the giant kind. Their eyes would have been in accordance with the weakness of the sunlight: less light, larger pupil and larger eyes, and then larger body. But Proctor did not support this hypothesis. Because of gravity and in order to make a Jove-man as active as our terrestrial counterpart, he underlined that we would have to give to these beings a size comparable to pygmies’one. However Proctor wanted to stay under the control of exact knowledge. He though we could only claim that “the beings of other worlds are very different from any we are acquainted with, without endeavoring to give shape and form to fancies that have no foundation in fact (Proctor 1870 ).”

Carl Sagan and Edwin Salpeter’s Sinkers, Floaters and Hunters

“Nature is not obliged to follow our speculations. But if there are billions of inhabited worlds in the Milky Way Galaxy, perhaps there will be a few populated by the sinkers, floaters and hunters which our imaginations, tempered by the laws of physics and chemistry, have generated.” (Sagan 1980 )

Since Flammarion or Proctor’s time, the idea of plurality of worlds has significantly evolved. Exobiology was born in the 1960s as a result of the space exploration and its confrontation to the problem of biological contamination and planetary protection. In the meantime, the developments in genetics and molecular biology led to clarify the major components of the living systems. In this new context, planetary studies and advances in biology benefited to the speculations about life forms on other worlds. The historical debate continued with modern “pluralists” such as the American astronomer Carl Sagan (1934–1996) who contributed to the establishment of Exobiology as a credible science among institutional research programs.

Three years after the first fly-by of Jupiter by a space probe (Pioneer 10), Carl Sagan and Edwin Salpeter envisaged in 1976 the possibility of exotic biota in the upper regions of Jupiter’s atmosphere (Sagan and Salpeter 1976 ). They proposed that other metabolic strategies such as chemoautotrophy or photoautotrophy would have to be employed by organisms present in the Jovian atmosphere. They discussed many aspects of a possible Jovian biology and deduced from the supposed composition of Jupiter’s atmosphere (thought to present some similarities to the primitive terrestrial one) that organic molecules might be falling from the upper strata to the lower ones. They suggested that life could exist at a level of the Jovian atmosphere where descending organic molecules could be captured and used for energy (Schulze-Makuch and Irwin 2004 ). But how organisms could subsist in an environment so turbulent and, in the depths of the atmosphere, subjected to excessive heat?

Sagan and Salpeter made comparisons between ecology in the Jovian atmosphere and ecology in terrestrial oceans (food chain existing at three different levels in our oceans, i.e. photosynthetic plankton, fishes, predators). The three hypothetical Jovian equivalents of these organisms were named “sinkers”, “floaters” and “hunters” by Sagan and Salpeter. They imagined that the sinkers could be carried by convection to cooler layers of the atmosphere and that the floaters could behave like our terrestrial hydrogen balloons: the deeper a floater is carried, the stronger is the buoyant force returning it to the higher, cooler, safer regions of the atmosphere (Sagan 1980 ). The bigger a floater is, the more efficient it will be. Finally they imagined very large floaters, a few kilometers size, likely to be eaten by hunters attracted by their organic composition.

Sagan admitted that one cannot know precisely what life would be like in such a place, but he and his colleague just wanted to see if, within the laws of physics and chemistry, a world of this sort could possibly be inhabited (Sagan 1980 ). If Sagan’s Jupiter world seems today a little bit eccentric, Sagan’s main fruitful initiative was to consolidate the search for life elsewhere, especially the starting up of the first Exobiology experiments on Mars.

Dirk Schulze-Makuch and Louis N. Irwin’s Xenobiology

Nowadays, Exobiology is looking for life-as-we-know-it or similar to it, based on carbon chemistry and liquid water as solvent, in outer space in every suited place accessible to our technology. Of course, this assumption is based on the fact that we would not be able to draw a reliable conclusion from experimental results no comparable to the ones biochemical or biological known on Earth. In spite of this, very few (theoretical) attempts to imagine alternative forms of life with other parameters than the terrestrial ones have been suggested by scientific authors since Exobiology was created.