- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

history of film summary

Learn about the invention of the motion picture and its purpose and evolution.

history of film , also called history of the motion picture , History of cinema from the 19th century to the present. Following the invention of photography in the 1820s, attempts began to capture motion on film. Building on the work of Eadweard Muybridge and others, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson and his employer, Thomas Edison , developed one of the first motion-picture cameras, the Kinetograph, in 1891. Four years later the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière invented a camera and projector, and motion-picture technology soon spread from the U.S., France, and Britain to other countries. While early movies were often no more than “animated photographs,” filmmakers at the turn of the 20th century began to introduce narratives into their work. Especially notable was French director Georges Méliès, who combined illusion, comic burlesque, and pantomime in fantasy productions, including A Trip to the Moon (1902). In the U.S. the film industry grew particularly quickly, and Hollywood eventually become its centre, home to numerous studios. American director D.W. Griffith was credited with developing filmmaking as an art form with such techniques as the close-up, the scenic long shot, and crosscutting. Until the late 1920s, films were silent, but at that point a conversion to sound began, especially after the success of the musical The Jazz Singer (1927). This—as well as the later widespread adoption of Technicolor—launched a new era in cinema, and large-scale, often extravagant productions became popular. Following World War II, new genres developed, with a particular focus on realism, and movies faced competition from the emerging television industry. In the ensuing years, film continued to evolve, and, as the end of the 20th century approached, blockbusters and special-effects-driven fare became common, especially in the U.S. In addition, new technology led to advancements in animated movies, which became hugely popular. The introduction of streaming services in the early 21st century also affected the industry, notably by lessening the reliance on theatres.

The History of Film Timeline — All Eras of Film History Explained

M otion pictures have enticed and inspired artists, audiences, and critics for more than a century. Today, we’re going to explore the history of film by looking at the major movements that have defined cinema worldwide. We’re also going to explore the technical craft of filmmaking from the persistence of vision to colorization to synchronous sound. By the end, you’ll know all the broad strokes in the history of film.

Note: this article doesn’t cover every piece of film history. Some minor movements and technical breakthroughs have been left out – check out the StudioBinder blog for more content.

- Pre-Film: Photographic Techniques and Motion Picture Theory

- The Nascent Film Era (1870s-1910): The First Motion Pictures

- The First Film Movements: Dadaism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage Theory

- Manifest Destiny and the End of the Silent Era

- Hollywood Epics and the Pre-Code Era

- The Early Golden Age and the Introduction of Color

- Wartime Film and Cinematic Propaganda

- Post-War Film Movements: French New Wave, Italian Neorealism, Scandinavian Revival, and Bengali Cinema

- The Golden Age of Hollywood: The Studio System and Censorship

- New Hollywood: The Emergence of Global Blockbuster Cinema

- Dogme 95 and the Independent Movement

- New Methods of Cinematic Distribution and the Current State of Film

When Were Movies Invented?

Pre-film techniques and theory.

Movies refer to moving pictures and moving pictures can be traced all the way back to prehistoric times. Have you ever made a shadow puppet show? If you have, then you’ve made a moving picture.

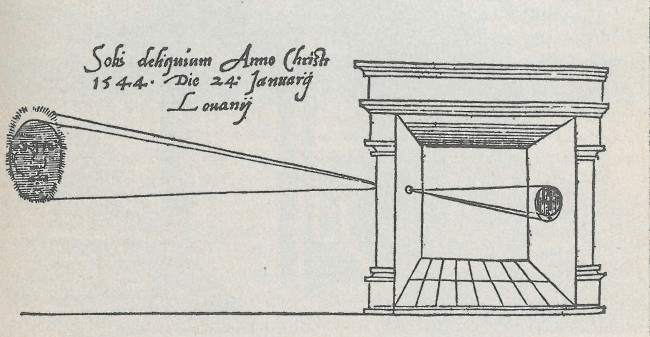

To create a moving picture with your hands is one thing, to utilize a device is another. The camera obscura (believed to have been circulated in the fifth century BCE) is perhaps the oldest photographic device in existence. The camera obscura is a device that’s used to reproduce images by reflecting light through a small peephole.

Here’s a picture of one from Gemma Frisius’ 1545 book De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica :

When Did Movies Start? • Camera Obscura in ‘De Radio Astronomica et Geometrica’

Through the camera obscura, we can trace the principles of filmmaking back thousands of years. But despite the technical achievement of the camera obscura, it took many of those years to develop the technology needed to capture moving images then later display them.

When Was Film Invented?

The first motion pictures.

When were movies invented ? The first motion pictures were incredibly simple – usually just a few frames of people or animals. Eadweard Muybridge’s The Horse in Motion is perhaps the most famous of these early motion pictures. In 1878, Muybridge set up a racing track with 24 cameras to photograph whether horses gallop with all four hooves off the ground at any time

The result was sensational. Muybridge’s pictures set the stage for all coming films; check out a short video on Muybridge and his work below.

When Did the First Movie Come Out? • Eadweard Muybridge’s ‘The Horse in Motion’ by San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Muybridge’s job wasn’t done after taking the photographs though; he still had to produce a projection machine to display them. So, Muybridge built a device called the zoopraxiscope, which was regarded as a breakthrough device for motion picture projecting.

Muybridge’s films (and tech) inspired Thomas Edison to study motion picture theory and develop his own camera equipment.

Films as we know them today emerged globally around the turn of the century, circa 1900. Much of that development can be attributed to the works of the Lumière Brothers, who together pioneered the technical craft of moviemaking with their cinematograph projection machine. The Lumière Brothers’ 1895 shorts are regarded as the first commercial films of all-time; though not technically true (remember Muybridge’s work).

French actor and illusionist Georges Méliès attempted to buy a cinematograph from the Lumière Brothers in 1895, but was denied. So, Méliès ventured elsewhere; eventually finding a partner in Englishman Robert W. Paul.

Over the following years, Méliès learned just about everything there was to know about movies and projection machines. Here’s a video on Méliès’ master of film and the illusory arts from Crash Course Film History.

When Were Movies Invented? • Georges Méliès – Master of Illusion by Crash Course

Méliès’ shorts The One Man Band (1900) and A Trip to the Moon (1902) are considered two of the most trailblazing films in all of film history. Over the course of his career, Méliès produced over 500 films. His contemporary mastery of visual effects , multiple exposure , and cinematography made him one of the greatest filmmakers of all-time .

Movie History

The first film movements.

War and cinema go together like two peas in a pod. As we continue on through our analysis of the history of film, you’ll start to notice that just about every major movement sprouted in the wake of war. First, the movements that sprouted in response to World War I:

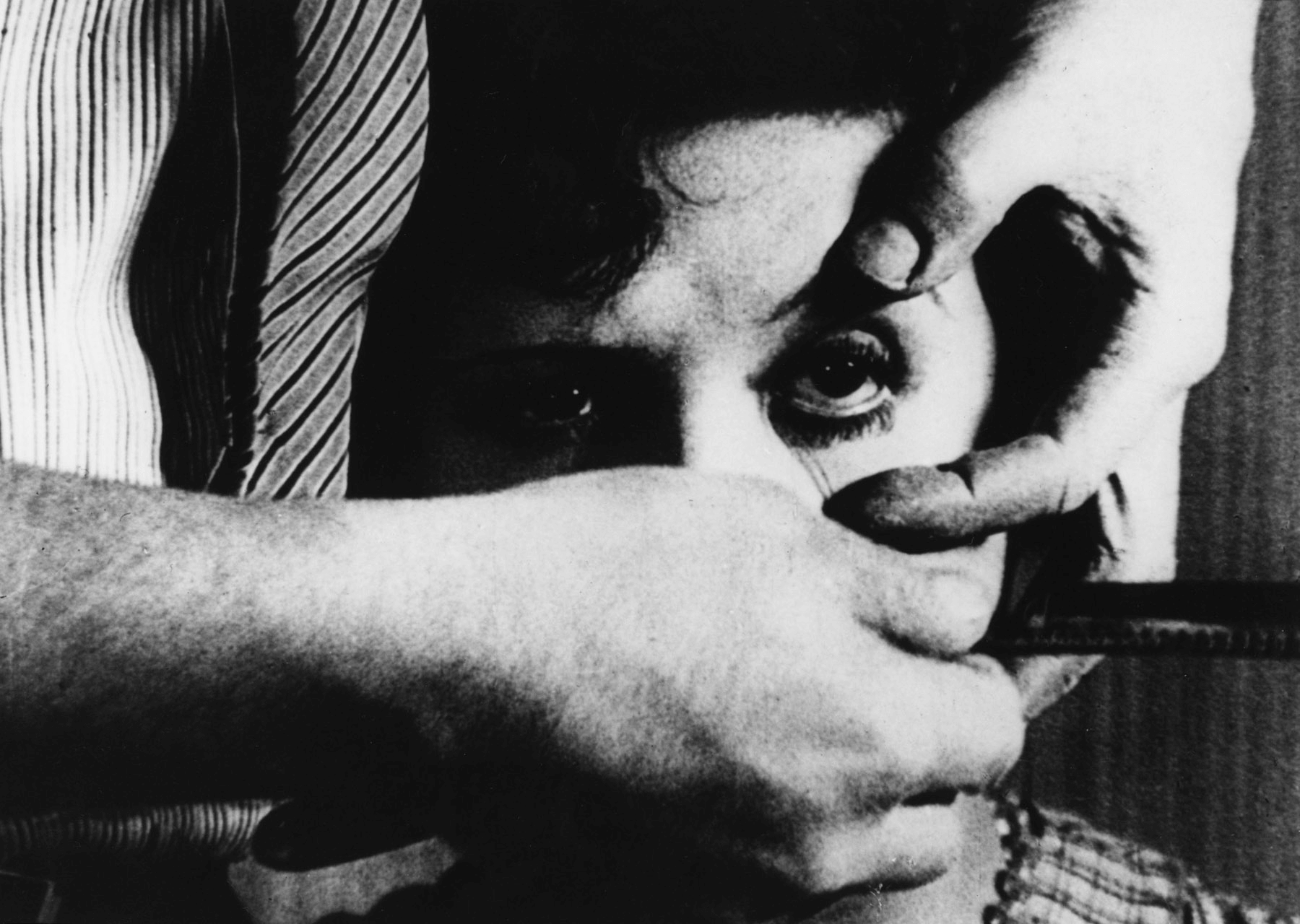

DADAISM AND SURREALISM

History of Motion Pictures • Still From ‘Un Chien Andalou’ by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí

Major Dadaist filmmakers: Luis Buñuel, Salvador Dalí, Germaine Dulac.

Major Dadaist films: Return to Reason (1923), The Seashell and the Clergyman (1928), U n Chien Andalou (1929).

Dadaism – an art movement that began in Zurich, Switzerland during World War I (1915) – rejected authority; effectively laying the groundwork for surrealist cinema .

Dadaism may have begun in Zurich circa 1915, but it didn’t take off until years later in Paris, France. By 1920, the people of France had expressed a growing disillusionment with the country’s government and economy. Sound familiar?

That’s because they’re the same points of conflict that incited the French Revolution. But this time around, the French people revolted in a different way: with art. And not just any art: bonkers, crazy, absurd, anti-this, anti-that art.

It’s important to note that Paris wasn’t the only place where dadaist art was being created. But it was the place where most of the dadaist, surrealist film was being created. We’ll get to dadaist film in a short bit, but first, let’s review a quick video on Dada art from Curious Muse.

Where Did Film Originate? • Dadaism in 8 Minutes by Curious Muse

Salvador Dalí, Germaine Dulac, and Luis Buñuel were some of the forefront faces of the surrealist film movement of the 1920s. French filmmakers, such as Jean Epstein and Jean Renoir experimented with surrealist films during this era as well.

Dalí and Buñuel’s 1929 film Un Chien Andalou is undoubtedly one of the most influential surrealist/dadaist films. Let’s check out a clip:

History of Movies • ‘Un Chien Andalou’ Clip

The influence of Un Chien Andalou on surrealist cinema can’t be quantified; key similarities can be seen between the film and the works of Walt Disney, David Lynch , Terry Gilliam , and other surrealist directors.

Learn more about surrealism in film →

GERMAN EXPRESSIONISM

The Creation of Film and German Expressionism • Still From ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’ by Robert Wiene

- German Expressionism – an art movement defined by monumentalist structures and ideas – began before World War I but didn’t take off in popularity until after the war, much like the Dadaist movement.

- Major German Expressionist filmmakers: Fritz Lang, F.W. Murnau, Robert Wiene

- Major German Expressionist films: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), Nosferatu (1922), and Metropolis (1927).

German Expressionism changed everything for the “look” and “feel” of cinema. When you think of German Expressionism, think contrast, gothic, dark, brooding imagery and colored filters. Here’s a quick video on the German Expressionist movement from Crash Course:

History of Film Timeline • German Expressionism Explained

The great works of the German Expressionist movement are some of the earliest movies I consider accessible to modern audiences. Perhaps no German Expressionist film proves this point better than Fritz Lang’s M ; which was the ultimate culmination of the movement’s stylistic tenets. Check out the trailer for M below.

Most Important Film in History of German Expressionism • ‘M’ (1931) Trailer, Restored by BFI

M not only epitomized the “monster” tone of the German Expressionist era, it set the stage for all future psychological thrillers. The film also pioneered sound engineering in film through the clever use of diegetic and non-diegetic sound . Fun fact: it was also one of the first movies to incorporate a leitmotif as part of its soundtrack.

Over time, the stylistic flourishes of the German Expressionist movement gave way to new voices – but its influence lived on in monster-horror and chiaroscuro lighting techniques.

Learn more about German Expressionism →

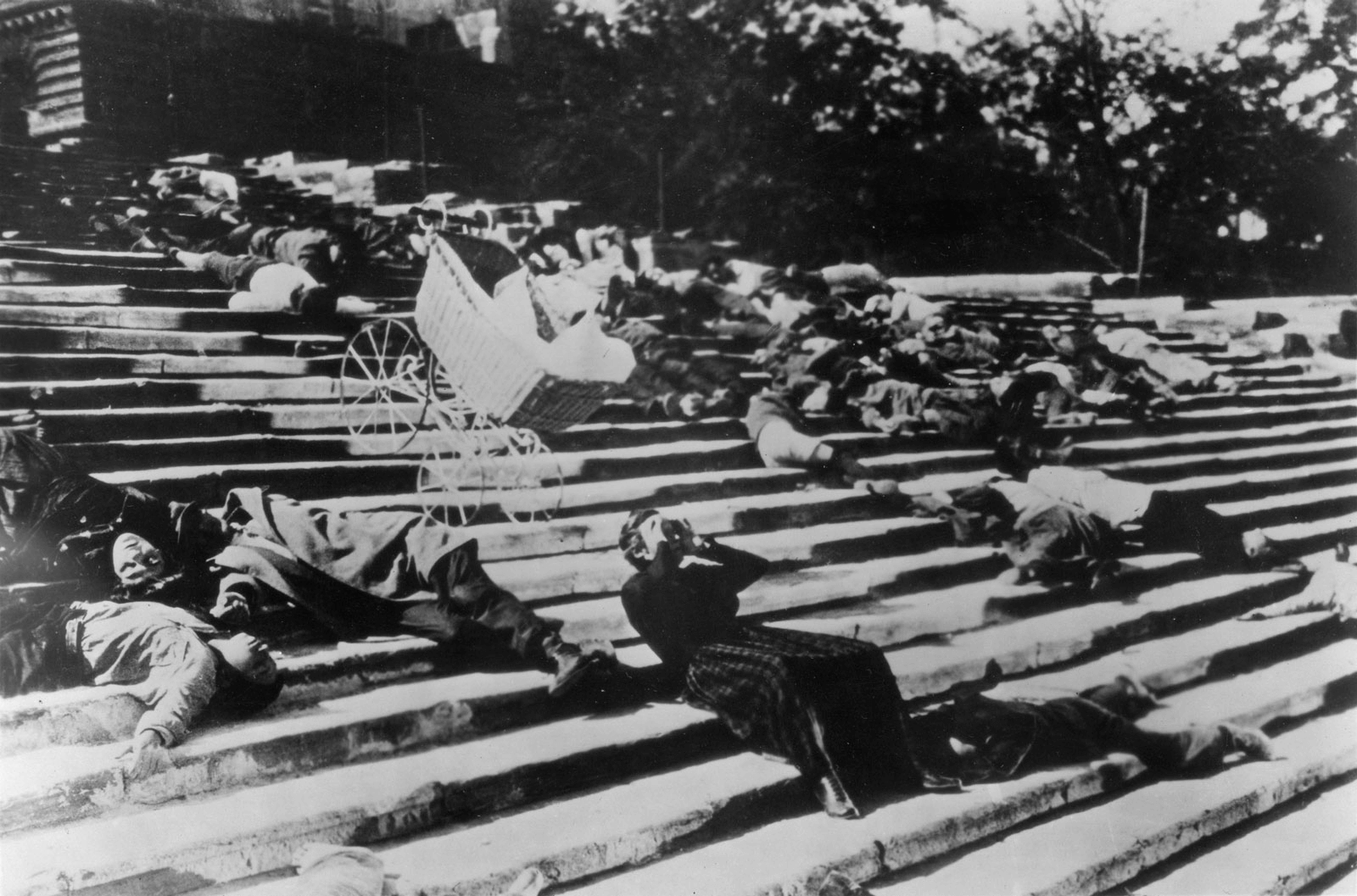

SOVIET MONTAGE THEORY

Film History 101 • The Odessa Steps in ‘Battleship Potemkin’

- Soviet Montage Theory – a Soviet Russian film movement that helped establish the principles of film editing – took place from the 1910s to the 1930s.

- Major Soviet Montage Theory filmmakers: Lev Kuleshov, Sergei Eisenstein , Dziga Vertov.

- Major Soviet Montage Theory films: Kino-Eye (1924), Battleship Potemkin (1925), Man With a Movie Camera (1929).

Soviet Montage Theory was a deconstructionist film movement, so as to say it wasn’t as interested in making movies as it was taking movies apart… or seeing how they worked. That being said, Soviet Montage Theory did produce some classics.

Here’s a video on Soviet Montage Theory from Filmmaker IQ:

Eras of Movies • The History of Cutting in Soviet Montage Theory by Filmmaker IQ

The Bolshevik government set-up a film school called VGIK (the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography) after the Russian Revolution. The practitioners of Soviet Montage Theory were the OG members of the “film school generation;” Kuleshov and Eisenstein were their teachers.

Battleship Potemkin was the most noteworthy film to come out of the Soviet Montage Theory movement. Check out an awesome analysis from One Hundred Years of Cinema below.

History of Film Summary • How Sergei Eisenstein Used Montage to Film the Unfilmable by One Hundred Years of Cinema

Soviet Montage Theory begged filmmakers to arrange, deconstruct, and rearrange film clips to better communicate emotional associations to audiences. The legacy of Soviet Montage Theory lives on in the form of the Kuleshov effect and contemporary montages .

Learn more about Soviet Montage Theory →

When Did Movies Become Popular?

The end of the silent era.

There was no Hollywood in the early years of American cinema – there was only Thomas Edison’s Motion Picture Patents Company in New Jersey.

Ever wonder why Europe seemed to dominate the early years of film? Well it was because Thomas Edison sued American filmmakers into oblivion. Edison owned a litany of U.S. patents on camera tech – and he wielded his stamps of ownership with righteous fury. The Edison Manufacturing Company did produce some noteworthy early films – such as 1903’s The Great Train Robbery – but their gaps were few and far between.

To escape Edison’s legal monopoly, filmmakers ventured west, all the way to Southern California.

Fortunate for the nomads: the arid temperature and mountainous terrain of Southern California proved perfect for making movies. By the early 1910s, Hollywood emerged as the working capital of the United States’s movie industry.

Director/actors like Charlie Chaplin , Harold Lloyd and Buster Keaton became stars – but remember, movies were silent, and people knew there would be an acoustic revolution in cinema. Before we move on from the Silent Era, check out this great video from Crash Course.

When Did Movies Become Popular? • The Silent Era by Crash Course

The Silent Era holds an important place in film history – but it was mostly ushered out in 1927 with The Jazz Singer . Al Jolson singing in The Jazz Singer is considered the first time sound ever synchronized with a feature film . Over the next few years, Hollywood cinema exploded in popularity. This short period from 1927-1934 is known as pre-Code Hollywood.

When Did Hollywood Start?

Pre-code hollywood.

In our previous section, we touched on the rise of Hollywood, but not the Hollywood epic. The Hollywood epic, which we regard as longer in duration and wider in scope than the average movie, set the stage for blockbuster cinema. So, let’s quickly touch on the history of Hollywood epics before jumping into pre-code Hollywood.

It’s impossible to talk about Hollywood epics without bringing up D.W. Griffith. Griffith was an American film director who created a lot of what we consider “the structure” of feature films. His 1915 epic The Birth of a Nation brought the technique of cinematic storytelling into the future, while consequently keeping its subject matter in the objectionable past.

For more on Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (and its complicated legacy), check out this poignant interview clip with Spike Lee .

History of Filmmaking • Spike Lee on ‘The Birth of a Nation’

As Lee suggests, it’s important to acknowledge the technical achievement of films like The Birth of a Nation and Gone With the Wind without condoning their horrid subject matter.

As another great director once said: “tomorrow’s democracy discriminates against discrimination. Its charter won’t include the freedom to end freedom.” – Orson Welles.

Griffith made more than a few Hollywood epics in his time, but none were more famous than The Birth of a Nation .

Okay, now that we reviewed the foundations of the Hollywood epic, let’s move on to pre-code Hollywood.

PRE-CODE HOLLYWOOD

A History of Film • James Cagney in ‘The Public Enemy’

- Pre-Code Hollywood – a period in Hollywood history after the advent of sound but before the institution of the Hays Code – circa ~1927-1934.

- Major Pre-Code stars: Ruth Chatterton, Warren William, James Cagney.

- Major Pre-Code films: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931), The Public Enemy (1931), Baby Face (1933).

Pre-Code Hollywood was wild. Not just wild in an uninhibited sense, but in a thematic sense too. Films produced during the pre-Code era often focused on illicit subject matter, like bootlegging, prostitution, and murder – that wasn't the status quo for Hollywood – and it wouldn’t be again until 1968.

We’ll get to why that year is important for film history in a bit, but first let’s review pre-Code Hollywood with a couple of selected scenes from Kevin Wentink on YouTube.

Movie Film History • Pre-Code Classic Clips

Pre-Code movies were jubilant in their creativity; largely because they were uncensored . But alas, their period was short-lived. In 1934, MPPDA Chairman William Hays instituted the Motion Picture Production Code banning explicit depictions of sex, violence, and other “sinful” deeds in movies.

Learn more about Pre-Code Hollywood →

Development of Movies

The early golden age and color in film.

The 1930s and early 1940s produced some of the greatest movies of all-time – but they also changed everything about the movie-making process. By the end of the Pre-Code era, the free independent spirit of filmmaking had all but evaporated; Hollywood studios had vertically integrated their business operations, which meant they conceptualized, produced, and distributed everything “in-house.”

That doesn’t mean movies made during these years were bad though. Quite the contrary – perhaps the two greatest American films ever made, Citizen Kane and Casablanca , were made between 1934 and 1944.

But despite their enormous influence, neither Citizen Kane nor Casablanca could hold a candle to the influence of another film from this decade: The Wizard of Oz .

The Wizard of Oz wasn’t the first film to use Technicolor , but it was credited with bringing color to the masses. For more on the industry-altering introduction of color, check out this video on The Wizard of Oz from Vox.

When Was Color Movies Invented? • How Technicolor Changed Movies

Technicolor was groundbreaking for cinema, but the dye-transfer process of its colorization was hard… and cost prohibitive for studios. So, camera manufacturers experimented with new processes to streamline color photography. Overtime, they were rewarded with new technologies and techniques.

Learn more about Technicolor →

Cinema Eras

Wartime and propaganda films.

In 1937, Benito Mussolini founded Cinecittà , a massive studio that operated under the slogan “Il cinema è l'arma più forte,” which translates to “the cinema is the strongest weapon.” During this time, countries all around the world used cinema as a weapon to influence the minds and hearts of their citizens.

This was especially true in the United States – prolific directors like Frank Capra, John Ford, John Huston, George Stevens, and William Wyler enlisted in the U.S. Armed Forces to make movies to support the U.S. war cause.

Documentarian Laurent Bouzereau made a three-part series about the war films of Capra, Ford, Huston, Stevens, and Wyler. Check out the trailer for Five Came Back below.

A History of Film • Five Came Back Trailer

Wartime film is important to explore because it teaches us about how people interpret propaganda. For posterity’s sake, let’s define propaganda as biased information that’s used to promote political points.

Propaganda films are often regarded with a negative connotation because they sh0w a one-sided perspective. Films of this era – such as those commissioned for the US Department of War’s Why We Fight series – were one-sided because they were made to counter the enemy’s rhetoric. It’s important to note that “one-sided” doesn’t mean “wrong” – in the case of the Why We Fight series, I think most people would agree that the one-sidedness was appropriate.

Over time, wartime film became more nuanced – a point proven by the 1966 masterwork The Battle of Algiers .

History of Movies

Post-war film movements.

Global cinema underwent a renaissance after World War II; technically, creatively, and conceptually. We’re going to cover a few of the most prominent post-war film movements, starting with Italian Neorealism.

ITALIAN NEOREALISM

Movie Film History • Still from Vittorio De Sica’s ‘Umberto D.’

- Italian Neorealism (1944-1960) – an Italian film movement that brought filmmaking to the streets; defined by depictions of the Italian state after World War II.

- Major Italian Neorealist film-makers: Vittorio De Sica, Roberto Rossellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Luchino Visconti, Federico Fellini .

- Major Italian Neorealist films: Rome, Open City (1945), Bicycle Thieves (1948), La Strada (1954), Il Posto (1961).

Martin Scorcese called Italian Neorealism “the rehabilitation of an entire culture and people through cinema.” World War II devastated the Italian state: socially, economically, and culturally.

It took people’s lives and jobs, but perhaps more importantly, it took their humanity. After the War, the people needed an outlet of expression, and a place to reconstruct a new national identity. Here’s a quick video on Italian Neorealism.

Movie History • How Italian Neorealism Brought the Grit of the Streets to the Big Screen by No Film School

Italian Neorealism produced some of the greatest films ever made. There’s some debate as to when the movement started and ended – some say 1943-1954, others say 1945-1955 – but I say it started with Rome, Open City and ended with Il Posto . Why? Because those movies perfectly encompass the defining arc of Italian Neorealism, from street-life after World War II to the rise of bureaucracy. Rome, Open City shows Italy in the thick of chaos, and Il Posto shows Italy on the precipice of a new era.

The legacy of Italian Neorealism lives on in the independent filmmaking of directors like Richard Linklater, Steven Soderbergh, and Sean Baker.

Learn more about Italian Neorealism →

FRENCH NEW WAVE

Development of Movies • Still From Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless

- French New Wave (1950s onwards) – or La Nouvelle Rogue, a French art movement popularized by critics, defined by experimental ideas – inspired by old-Hollywood and progressive editing techniques from Orson Welles and Alfred Hitchcock.

- Major French New Wave filmmakers: Jean-Luc Godard , François Truffaut , Agnes Varda.

- Major French New Wave films: The 400 Blows (1959), Breathless (1960), Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962).

The French New Wave proliferated the auteur theory , which suggests the director is the author of a movie; which makes sense considering a lot of the best French New Wave films featured minimalist narratives. Take Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless for example: the story is secondary to audio and visuals. The French New Wave was about independent filmmaking – taking a camera into the streets and making a movie by any means necessary.

Here’s a quick video on The French New Wave by The Cinema Cartography.

History of Filmmaking • Breaking the Rules With the French New Wave by The Cinema Cartography

It’s important to note that the pioneers of the French New Wave weren’t amateurs – most (but not all) were critics at Cahiers du cinéma , a respected French film magazine. Writers like Godard, Rivette, and Chabrol knew what they were doing long before they released their great works.

Other directors, like Agnes Varda and Alain Resnais, were members of the Left Bank, a somewhat more traditionalist art group. Left Bank directors tended to put more emphasis on their narratives as opposed to their Cahiers du cinéma counterparts.

The French New popularized (but did not invent) innovative filmmaking techniques like jump cuts and tracking shots . The influence of the French New Wave can be seen in music videos, existentialist cinema, and French film noir .

Learn more about the French New Wave →

Learn more about the Best French New Wave Films →

SCANDINAVIAN REVIVAL

A History of Film • Still from Ingmar Bergman’s ‘The Seventh Seal’

- Scandinavian Revival (1940s-1950s) – a filmmaking movement in Scandinavia, particularly Denmark and Sweden, defined by monochrome visuals, philosophical quandaries, and reinterpretations of religious ideals.

- Major Scandinavian Revival filmmakers: Carl Theodor Dreyer and Ingmar Bergman.

- Major Scandinavian Revival films: Day of Wrath (1943), The Seventh Seal (1957), Wild Strawberries (1957).

Swedish, Danish, and Finnish films have played an important role in cinema for more than 100 years. The Scandinavian Revival – or renaissance of Scandinavian-centric films from the 1940s-1950s – put the films of Sweden, Denmark, and Finland in front of the world stage.

Here’s a quick video on the works of the most famous Scandinavian director of all-time: Ingmar Bergman .

History of Cinema • Ingmar Bergman’s Cinema by The Criterion Collection

The influence of Scandinavian Revival can be seen in the works of Danish directors like Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier , as well as countless other filmmakers around the world.

BENGALI CINEMA

History of Motion Pictures • Still from Satyajit Ray’s ‘Pather Panchali’

- Bengali Cinema – or the cinema of West Bengal; also known as Tollywood, helped develop arthouse films parallel to the mainstream Indian cinema.

- Major Bengali filmmakers: Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen.

- Major Bengali films: Pather Panchali (1955) and Bhuvan Shome (1969).

The Indian film industry is the biggest film industry in the world. Each year, India produces more than a thousand feature-films. When most people think of Indian cinema, they think of Bollywood “song and dance” masalas – but did you know the country underwent a New Wave (similar to France, Italy, and Scandinavia) after World War II? The influence of the Indian New Wave, or classic Bengali cinema, is hard to quantify; perhaps it’s better expressed by the efforts of the Academy Film Archive, Criterion Collection, and L'Immagine Ritrovata film restoration artists. Here's an introduction to one of India's greatest directors, Satyajit Ray.

Evolution of Cinema • How Satyajit Ray Directs a Movie

In 2020, Martin Scorsese said, “In the relatively short history of cinema, Satyajit Ray is one of the names that we all need to know, whose films we all need to see.” Ray is undoubtedly one of the preeminent masters of international cinema – and his name belongs in the conversation with Hitchcock, Renoir, Kurosawa, Welles, and all the other trailblazing filmmakers of the mid-20th century.

Learn more about Indian Cinema →

OTHER POST-WAR & NEW WAVE MOVEMENTS

How Has Film Changed Over Time? • Still from Akira Kurosawa’s ‘Stray Dog’

Italy, France, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and India weren’t the only countries that underwent “New Waves” after World War II; Japan, Iran, Great Britain, and Russia had minor film revolutions as well.

In Japan, directors like Akira Kurosawa and Yasujirō Ozu introduced new filmmaking techniques to the masses; their 1940s-1950s films were great, but some filmmakers, like Hiroshi Teshigahara and Nagisa Ōshima felt they were better suited to make films about “modern” Japan.

Here’s a quick video on the Japanese New Wave from Film Studies for YouTube.

Cinema Eras • Japanese New Wave Video Essay by Film Studies for YouTube

Some cinema historians combine the Japanese New Wave with the post-war era. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll do the same: the major films of this era (1940s-1960s) include Rashomon (1950), Tokyo Story (1953), and Seven Samurai (1954).

The Iranian New Wave began about fifteen years after the end of World War II, circa 1960-onwards. Iranian cinema is an important part of Iranian culture. Here’s a quick video on Iranian cinema from BBC News.

Important Dates in Film History • Spotlight on Iran’s Film Industry via BBC News

Cinema historians widely consider Dariush Mehrjui’s The Cow (1969) to be a foundational film for the movement. Abbas Kiarostami is perhaps the most famous Iranian filmmaker of all-time. His film Close-Up (1990) is regarded as one of the greatest films ever produced in Iran.

The British New Wave was a minor film movement that was defined by kitchen-sink realism – or depictions of ordinary life. Many filmmakers of the British New Wave were critics before they were directors; and they wanted to depict the average life of Britain through a filmic eye.

Here’s a lecture on the British New Wave from Professor Ian Christie at Gresham College.

History of Filmmaking • Street-Life and New Wave British Cinema by Gresham College

The British New Wave became synonymous with Cinéma vérité (cinema of truth) over the course of its brief existence. Some of the major pictures of the movement include: Look Back in Anger (1959) and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960).

Russian cinema is complex… probably just as complex as American cinema. We could spend 100 pages talking about Russian cinema – but that’s not the focus of this article. We already talked about Soviet Montage Theory, so let’s skip ahead to post World War II Soviet cinema.

When I think of post-war Soviet cinema, I think of one name: Andrei Tarkovsky . Tarkovsky directed internationally-renowned films like Andrei Rublev (1969), Solaris (1972), and Stalker (1979) in his brief career as the Soviet Union’s pre-eminent maestro.

Here’s a deep dive into the works of Tarkovsky by “Like Stories of Old.”

Film Industry Timeline • Praying Through Cinema – Understanding Andrei Tarkovsky by Like Stories of Old

Tarkovsky wasn’t the only great filmmaker in the post-war Soviet Union – but he was probably the best. I’d be remiss if I didn’t use this section to focus on him.

History of Film Timeline

The golden age of hollywood.

The Hollywood Golden Age began with the fall of pre-Code Hollywood (1934) and lasted until the birth of New Hollywood (1968).

- Major stars of the Hollywood Golden Age: Humphrey Bogart, Cary Grant, Katharine Hepburn, Audrey Hepburn, Elizabeth Taylor, Clark Gable, Ingrid Bergman, Henry Fonda, Kirk Douglas, Gregory Peck, Lauren Bacall, Grace Kelly, James Dean, Marlon Brando.

- Major filmmakers of the Hollywood Golden Age: Cecil B. DeMille , Orson Welles , Billy Wilder , Frank Capra , John Huston , Alfred Hitchcock , John Ford , Elia Kazan , David Lean , Joseph Manckiewicz.

Notice how many names we included? It’s ridiculous – it would be wrong to omit any of them; and still, there are probably dozens of iconic figures missing. The Hollywood Golden Age was all about stars. Stars sold pictures and the studios knew it. “Hepburn” could sell a movie every time; it didn’t matter which Hepburn – or what the movie was about.

Here’s a breakdown of the Hollywood Golden Age from Crash Course.

History of Movies • The Golden Age of Hollywood by Crash Course

There are a few sub-eras within the Hollywood Golden Age era; let’s break them down in detail.

Important Dates in Film History • Photo of MPPDA Chairman William Hays

In 1934, Chairman William Hays of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America instituted a production code that banned graphic cinematic depictions of sex, violence, and other illicit deeds.

The “Production Code” or “ Hays Code ” was responsible for the censorship of Hollywood films for 34 years.

For more on the history of Hollywood censorship and movie ratings, check out the video from Filmmaker IQ below.

How Has Film Changed Over Time? • History of Hollywood Censorship by Filmmaker IQ

The Hays Code kept cinema tame, which led to Hollywood romanticism. But it also made cinema unrealistic, which made the American public yearn for improbable outcomes. Not to mention that it set race relations back an indeterminable amount of years. The Hays Code specifically forbade miscegenation, or “the breeding of people of different races.”

Ultimately, the censorship of Hollywood films was about keeping power in the hands of people with power. It had some positive unintended outcomes – but it wasn’t worth the cost of suppression.

Learn more about the Hays Code →

Learn more about the history of movie censorship →

Film Industry Timeline • Still from Nicholas Ray’s ‘In a Lonely Place’

Film noir is a style of film that’s defined by moralistic themes, high contrast lighting, and mysterious plots. Oftentimes, film noirs feature hardboiled protagonists . It’s important to note that film noir is a style, not a film movement. As such, we won’t list “film noir directors,” but we will list some iconic examples of film noir.

Major Hollywood film noirs: The Maltese Falcon (1941), Double Indemnity (1944), Sunset Boulevard (1950).

Hollywood film noirs were inspired by classic detective fiction stories, like those of Arthur Conan Doyle and Edgar Allan Poe. Over time, film noir was adopted as a style around the world – most famously in Great Britain with Carol Reed’s The Third Man .

Here’s a video on defining film noir from Jack’s Movie Reviews.

Eras of Movies • Defining Film Noir by Jack’s Movie Reviews

We could spend another 50 pages on film noir (like many other topics in this compendium) – but instead, let’s continue on.

Learn more about film noir →

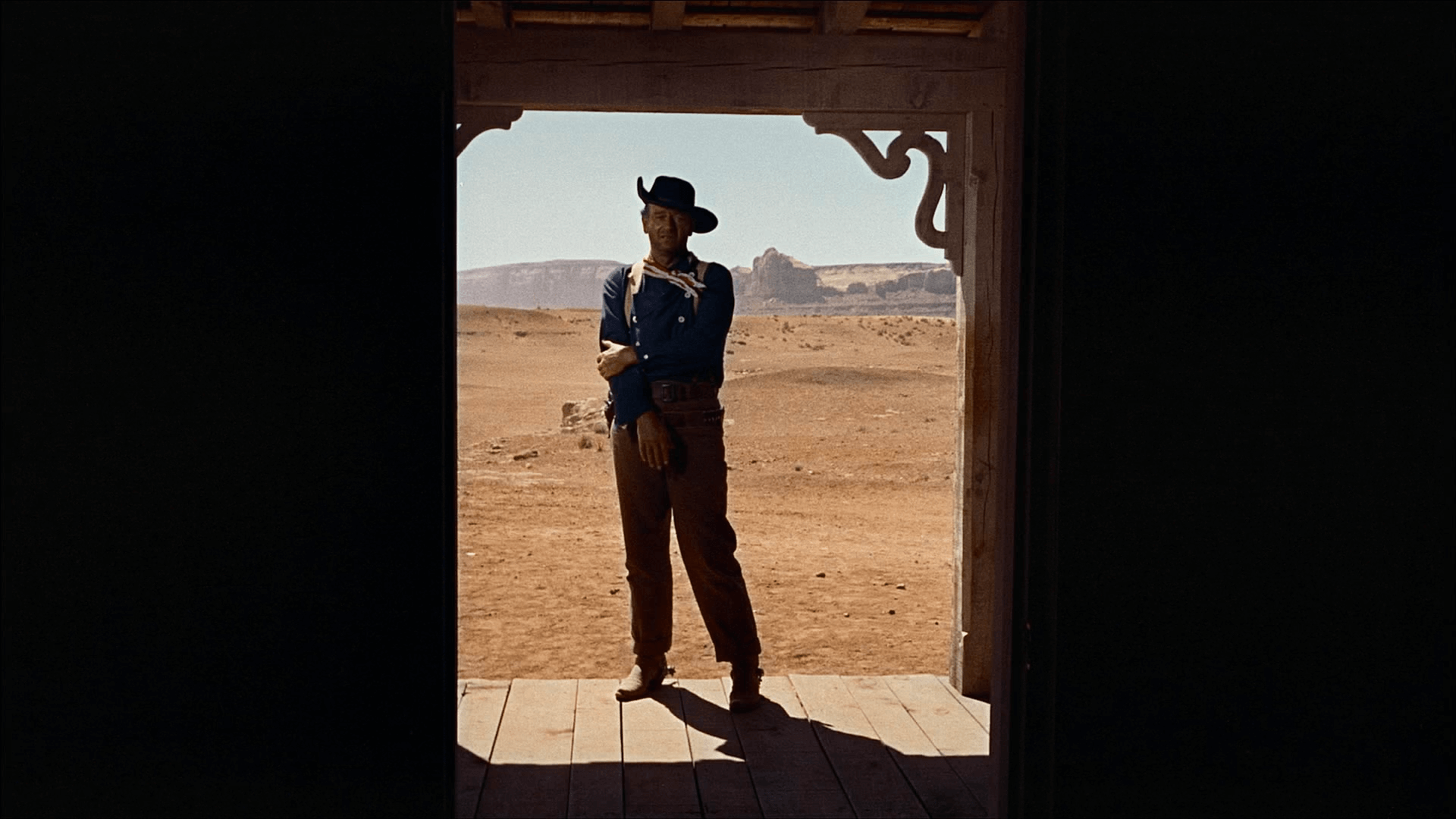

How Movies Have Changed Over Time • Still from John Ford’s ‘The Searchers’

Hollywood westerns were incredibly popular during the Golden Age. Why? Because the American people loved stories of lawlessness and expansion, dating all the way back to Erastus Beadle’s dime novels – making the western the perfect subgenre for vicarious cinema.

Major Hollywood westerns: Stagecoach (1939), High Noon (1952), The Searchers (1956).

Westerns, much like film noirs, allowed repressed audiences to feel alive at the movie theater. Remember: Hollywood films were censored during the Golden Age, which meant you couldn’t find graphic violence or pornography at the theaters. So, audiences took what they could get – which was usually film noirs and Westerns.

Here’s a video on the history of Westerns in Hollywood cinema.

Evolution of Film • Western Movies History by Ministry of Cinema

Hollywood westerns inspired a global fascination with cowboys, mercenaries, and gunslingers, directly leading to samurai cinema, spaghetti westerns, zapata westerns, and neo-westerns.

Learn more about Spaghetti Westerns →

Learn more about Neo-Westerns →

McCARTHYISM & THE BLACKLIST

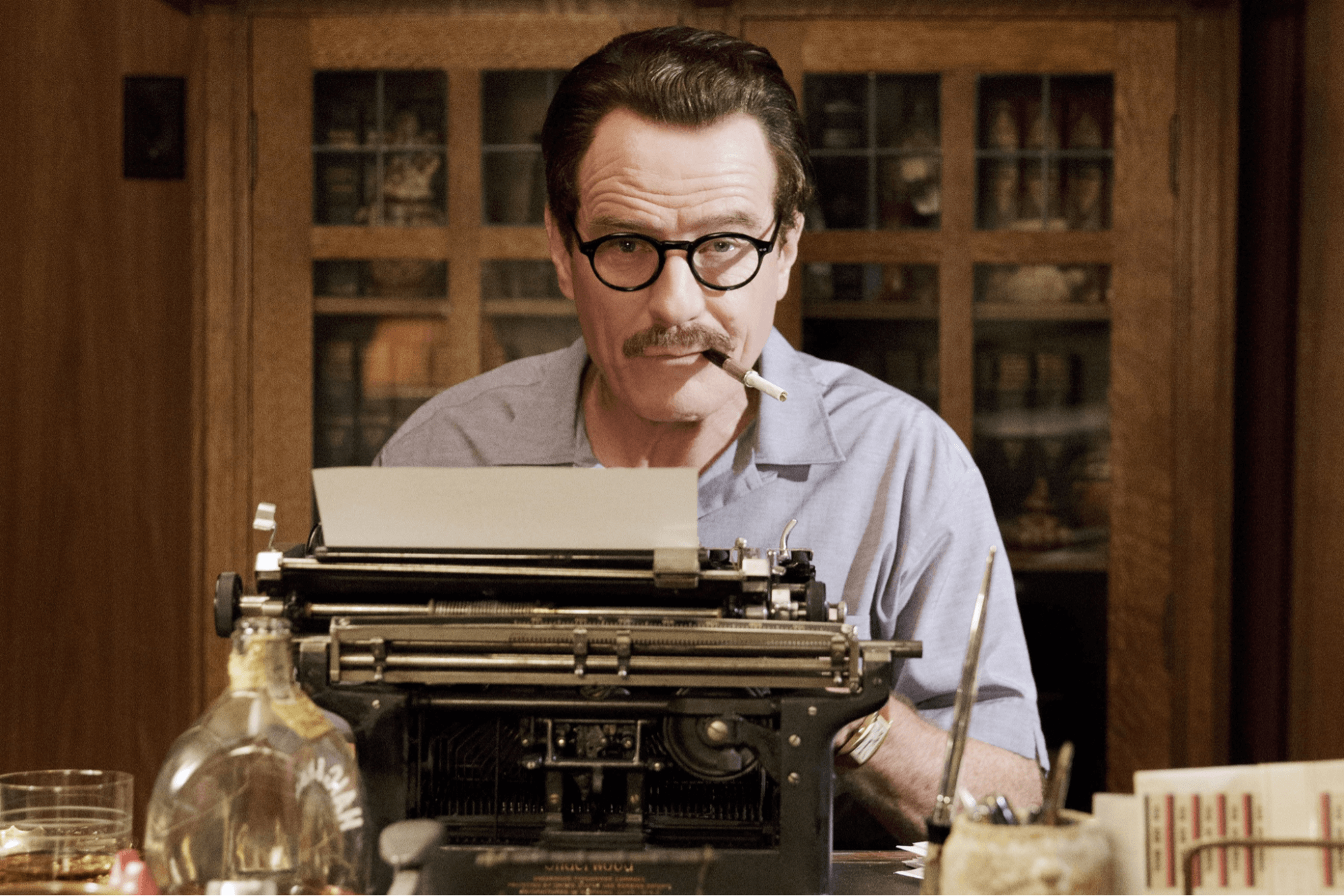

How Movies Have Changed Over Time • Bryan Cranston as Blacklisted Screenwriter Dalton Trumbo

In 1947, the state of Wisconsin elected notorious fear-monger Joseph McCarthy as senator of their state. McCarthy hated free-speech – that’s not a one-sided perspective, that’s the truth. McCarthy spent his entire career demagoguing, and his legacy shows that.

In 1950, ten Hollywood screenwriters were summoned to appear before the United States Congress House of Un-American Activities, largely because of McCarthy's divisive rhetoric against communist sympathizers. The screenwriters were cited for contempt of congress and fired from their jobs, and thus, the blacklist was born.

For more on McCarthyism and the Hollywood blacklist , check out the video from Ted-Ed below.

The History of Film • McCarthyism and the Blacklist by Ted-Ed

The Hollywood blacklist derailed the careers of hundreds of writers, directors, and producers from 1950-1960. The blacklist ended when Kirk Douglas credited Dalton Trumbo – one of the most famous blacklisted screenwriters – as the screenwriter of Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus , effectively taking back control of Hollywood.

Learn more about the Hollywood Blacklist →

THE PARAMOUNT CASE

The History of Film • Paramount Studios Classic Style Logo

In 1948, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the five major motion picture studios: Paramount, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO violated the U.S. Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890.

As a result of the decision, movie studios could no longer solely create and distribute movies to their own theaters.

It may not sound important, but the Paramount Case changed everything for American cinema. Here’s a quick video on the Case and its lasting impact on Hollywood.

The History of Filmmaking • Film History 101: The Paramount Decree by Omar Rivera

The Paramount Case opened the door for international films and independent theaters. It also gave businesses more freedom to show movies outside of the MPPDA ratings system.

Evolution of Cinema

New hollywood.

Movie History • Still from Arthur Penn’s’ Bonnie and Clyde’

- New Hollywood, otherwise known as the Hollywood New Wave, introduced “the film school generation” to Hollywood. New Hollywood films are defined as larger in scope, darker in subject matter, and overtly more graphic than their Golden Age predecessors.

- Major New Hollywood filmmakers: George Lucas , Steven Spielberg , Martin Scorsese , Brian De Palma , Peter Bogdanovich, Woody Allen , Francis Ford Coppola , James Cameron .

- Major New Hollywood films: Bonnie and Clyde (1967), The Graduate (1967), Easy Rider (1969), Midnight Cowboy (1969), The Godfather (1972), American Graffiti (1973).

New Hollywood ushered American filmmaking into a new era by returning to the popular genres of the pre-Code era, such as gangster films and sex-centric films. It also marked the emergence of “film-school” directors like George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese. It’s clear from watching New Hollywood films that the writers and directors who produced them were acutely aware of cinema history.

During this era, writers like Woody Allen employed themes of existentialist cinema found in the French New Wave and Italian Neorealism (among other movements). Directors like Martin Scorsese utilized advanced framing techniques pioneered by masters of the pre-war era.

For more on New Hollywood, check out this feature documentary based Peter Biskind's seminal book "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls."

Movie History • How New Hollywood Was Born

New Hollywood (and its immediate aftermath) produced some of the greatest films of all-time: such as The Godfather (1972), The Godfather Part II (1974), Chinatown (1974), Taxi Driver (1976), Network (1976), and Annie Hall (1977).

Somewhat tragically, New Hollywood ended with the emergence of blockbuster films – such as Jaws (1975) and Star Wars (1977) – in the mid to late 1970s.

Learn more about New Hollywood →

Eras of Movies

Dogme 95 and independent movements.

Big-budget movies dominated the movie-scene after New Hollywood ended. Suddenly, cinema became more of a spectacle than an art-form. That’s not to say movies produced during this era (1975-1995) were bad – some big-budget films, like Back to the Future (1985) and Jurassic Park (1993) were financially successful and critically acclaimed; and writer/directors like John Hughes found enormous success making studio films about seemingly mundane life.

But despite the financial prospect of making contrived studio films, some filmmakers decided to go back to their roots and make films independently, much in the vein of the artists of the French New Wave. This spirit inspired the Danish Dogme 95 movement and the American Independent movement.

Evolution of Film • Photo Still from ‘Festen’ by Thomas Vinterberg

D0gme 95 – a Danish film movement that brought filmmaking back to its primal roots: no non-diegetic sound, no superficial action, and no director credit.

Major Dogme 95 filmmakers: Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier

Major Dogme 95 films: Dogme #1 – Festen (1998), Dogme #2 – The Idiots (1998), Dogme #12 – Italian for Beginners (2000).

It’s ironic that Dogme 95 , which states the director must not be credited, is perhaps best known for the fame of two of its founders: Thomas Vinterberg and Lars von Trier. Dogme 95 sought to rid cinema of extravagant special effects and challenging productions by making the filmmaking process as simple as possible. To do this, its founders created the Vows of Chastity: a ten-part manifesto for Dogme 95 filmmaking.

Check out a video on the Vows of Chastity and Dogme 95 below.

History of Cinema • Vows of Chastity – Films of Dogme 95 by FilmStruck

Ultimately, the Vows of Chastity proved too limiting for filmmakers – but their influence lives on in New Danish cinema and independent films all over the world.

Learn more about Dogme 95 →

History of Cinema • Still from Kevin Smith’s ‘Clerks’

Indie film – or late 80s, early 90s cinema produced outside of the major motion picture system – was about experimenting with new cinematic forms, pushing the Generation Next agenda, and making art by any means necessary.

Major indie filmmakers: Richard Linklater , Wes Anderson , Steven Soderbergh , Jim Jarmusch .

Major indie films: Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989), Slacker (1990), and Bottle Rocket (1994).

The American indie movement launched the careers of a myriad of great directors. It also marked the beginning of a major decline for film. The advent of digital cameras and DVDs meant film was becoming a luxury. Conversely, it meant procuring the necessary equipment needed to make movies was easier than ever.

Indie-films introduced the idea that anybody could make movies. For better or worse, the point proved to be true. The '90s and early 2000s were littered with independently produced, scarcely funded movies. It was unrestrained, but it was also liberating.

Check out this video on no-budget filmmaking from The Royal Ocean Film Society to learn more about the indie movement.

Evolution of Cinema • Lessons for the No-Budget Feature by The Royal Ocean Film Society

The indie movement (as it was known then) ended when the major studios (like Disney and Turner) bought the independent studios (like Miramax and New Line). Today, we often refer to minimalist, low-budget movies as independent, but the truth is just about every production studio is owned by a conglomerate.

How Has the Film Industry Changed?

New distribution methods.

The current state of cinema is in flux due to a wide array of issues, including (but not limited to) the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, the wide-adoption of new streaming services from first-party producers, i.e. Netflix, Disney, Paramount, etc., and the growth of new media forms.

Over the last few years, big-budget epics like Marvel’s The Avengers and Star Wars have performed well at the U.S. and Chinese box-office, but their success has often come at the expense of medium-budget movies; the result being a deeper lining of the pockets of exorbitantly wealthy corporations.

Still, there’s a lot of money to be made – a point perhaps best proven by the rise of the Chinese film industry. In 2020, China overtook North America as the world’s biggest box-office market, per THR. Check out a video on Hengdian, China’s largest film studio from South China Morning Report.

Movie History • Inside China’s Largest Film Studio by South China Morning Report

Movies seem to get bigger and bigger every year but the development of computer-generated-imagery and compositing techniques has given filmmakers the technology to create vast worlds in limited spaces.

So: what’s next for film? Who’s to say for certain? The future of the industry looks cloudy – but there’s definite promise on the horizon. More people have cinema-capable cameras in their pocket today than ever before. Perhaps the next great movement will take off soon.

Related Posts

- What is CinemaScope →

- When Was the Camera Invented →

- What Was the First Movie Ever Made →

100 Years of Cinematography

The history of film includes a lot more than what we went over here. In 2019, the American Society of Cinematographers celebrated 100 years of great cinematography with a list of legendary works. In our next article, we break down some of the ASC’s choices with video examples. Follow along as we look at the work of Conrad Hall, Vittorio Storaro, and more.

Up Next: Best Cinematography of All-Time →

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards..

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.

Learn More ➜

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- How to Make a Production Call Sheet From Start to Finish

- What is Call Time in Production & Why It Matters

- How to Make a Call Sheet in StudioBinder — Step by Step

- What is a Frame Narrative — Stories Inside Stories

- What is Catharsis — Definition & Examples for Storytellers

- 1 Pinterest

Log in Create an Account

A Brief History of Cinema

Long (12 plus activities)

England, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales

This resource is part of the following themes

- Beyond Hollywood

- Into Archive Film: Past Present Future

The first moving images were shown to audiences in the 1800s. Since then, new technologies and storytelling techniques have been developed, different film styles have gone in and out of fashion, and audience tastes have changed.

From Silent to CGI: A Brief History of Cinema has been developed with young people aged 7-14 in mind. It aims to showcase the pivotal moments in the history of cinema, from its early inception to the multi-sensory experience of today. This resource will complement curricular learning (such as history, English or design and technology) or provide a backdrop to Into Film Club activity involving watching and making films.

The resource is comprised of activities, photocopiable student sheets and film clips.

This resource includes

From silent to cgi: a brief history of cinema powerpoint presentation.

Presentation containing film clips for the History of Cinema resource.

Size: 94.04 MB

Login or Create an Account

From Silent to CGI: A Brief History of Cinema teachers' notes

Activities and student sheets to support the History of Cinema resource.

Size: 1.56 MB

This Resource Supports

- Design and Technology

Got Some Feedback?

We love to hear how educators have used our resources.

Updating our resources

We have developed a large catalogue of educational resources since launching in 2013, and some references and terminology will inevitably have dated as society and language evolves. We are aware of this and will be updating resources when our production schedule allows.

Related Films

Charlie Chaplin: The Mutual Films, Volume 1 (1916)

Some of the earliest films from one of cinema's most famous silent slapstick stars, Charlie Chaplin.

Age group All ages

Duration 141 mins

Dracula (1931)

Stream on Into Film+

119 reviews

The immortal vampire, Count Dracula, puts a plan into motion to leave Transylvania and bring his evil to the unsuspecting shores of England.

Age group 11+ years

Duration 73 mins

Gone With The Wind (1939)

One of the most famous love stories ever, set against an American Civil War backdrop, about a romance threatened by violence, famine and fire.

Duration 211 mins

Jaws (1975)

1,936 reviews

A local police chief finds himself in a titanic struggle against the great white shark that has been terrorising the inhabitants of a quiet island.

Duration 124 mins

Le Voyage Dans La Lune (A Trip To The Moon) (1902)

Fascinating early slice of science fiction and a founding stone of modern cinema.

Age group 7+ years

Duration 13 mins

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937)

Stream on Into Film+ Premium

538 reviews

Disney's funny, beautifully drawn animated version of the classic fairytale about a lovely princess on the run from her wicked stepmother.

Age group 5–11 years

Duration 83 mins

Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens (2015)

433 reviews

Old and new forces combine in this continuation of the space saga, set thirty years after the events of Return of the Jedi.

Duration 135 mins

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

3,758 reviews

One of early cinema's most beloved films sees a young girl called Dorothy, and her dog Toto, whisked away from Kansas to a fantastical land called Oz.

Duration 98 mins

How do Into Film Clubs work?

Find out more about what's involved in running your very own Into Film Club.

Find out more

Learn how to make the most of film in education with our training programme.

Film of the Month

Any film. Any genre. Any time of year. Enter our Film of the Month competition today.

Closing date Ongoing

Viewing 2 of 2 related items.

What our educators say

"I think that our work on ‘The Girl and the Fox’ has really benefitted our children. I would thoroughly recommend the Into Film approach to any school wanting to improve attainment in literacy." - Tim Dadds, Deputy Headteacher, Cwmrhydyceirw Primary School, Wales

Javascript is disabled

- We are changing

- Accessible screenings

- Sound and Vision

- Objects and stories

- Researchers

- Access to our collection

- Research help

- Research directory

- Donate an object

- Science Museum Group Journal

- Press office

- Support the museum

- Volunteering

- Corporate sponsorship

National Science and Media Museum Bradford BD1 1NQ

The museum, IMAX and Pictureville are temporarily closed. Find out about our major transformation .

A very short history of cinema

Published: 18 June 2020

Learn about the history and development of cinema, from the Kinetoscope in 1891 to today’s 3D revival.

Cinematography is the illusion of movement by the recording and subsequent rapid projection of many still photographic pictures on a screen. Originally a product of 19th-century scientific endeavour, cinema has become a medium of mass entertainment and communication, and today it is a multi-billion-pound industry.

Who invented cinema?

No one person invented cinema. However, in 1891 the Edison Company successfully demonstrated a prototype of the Kinetoscope , which enabled one person at a time to view moving pictures.

The first public Kinetoscope demonstration took place in 1893. By 1894 the Kinetoscope was a commercial success, with public parlours established around the world.

The first to present projected moving pictures to a paying audience were the Lumière brothers in December 1895 in Paris, France. They used a device of their own making, the Cinématographe, which was a camera, a projector and a film printer all in one.

What were early films like?

At first, films were very short, sometimes only a few minutes or less. They were shown at fairgrounds, music halls, or anywhere a screen could be set up and a room darkened. Subjects included local scenes and activities, views of foreign lands, short comedies and newsworthy events.

The films were accompanied by lectures, music and a lot of audience participation. Although they did not have synchronised dialogue, they were not ‘silent’ as they are sometimes described.

The rise of the film industry

By 1914, several national film industries were established. At this time, Europe, Russia and Scandinavia were the dominant industries; America was much less important. Films became longer and storytelling, or narrative, became the dominant form.

As more people paid to see movies, the industry which grew around them was prepared to invest more money in their production, distribution and exhibition, so large studios were established and dedicated cinemas built. The First World War greatly affected the film industry in Europe, and the American industry grew in relative importance.

The first 30 years of cinema were characterised by the growth and consolidation of an industrial base, the establishment of the narrative form, and refinement of technology.

Adding colour

Colour was first added to black-and-white movies through hand colouring, tinting, toning and stencilling.

By 1906, the principles of colour separation were used to produce so-called ‘natural colour’ moving images with the British Kinemacolor process, first presented to the public in 1909.

Kinemacolor was primarily used for documentary (or ‘actuality’) films, such as the epic With Our King and Queen Through India (also known as The Delhi Durbar ) of 1912, which ran for over 2 hours in total.

The early Technicolor processes from 1915 onwards were cumbersome and expensive, and colour was not used more widely until the introduction of its three‑colour process in 1932. It was used for films such as Gone With the Wind and The Wizard of Oz (both 1939) in Hollywood and A Matter of Life and Death (1946) in the UK.

Frames of stencil colour film

Advertisement for With Our King and Queen Through India , 1912

Adding sound

The first attempts to add synchronised sound to projected pictures used phonographic cylinders or discs.

The first feature-length movie incorporating synchronised dialogue, The Jazz Singer (USA, 1927), used the Warner Brothers’ Vitaphone system, which employed a separate record disc with each reel of film for the sound.

This system proved unreliable and was soon replaced by an optical, variable density soundtrack recorded photographically along the edge of the film, developed originally for newsreels such as Movietone.

Cinema’s Golden Age

By the early 1930s, nearly all feature-length movies were presented with synchronised sound and, by the mid-1930s, some were in full colour too. The advent of sound secured the dominant role of the American industry and gave rise to the so-called ‘Golden Age of Hollywood’.

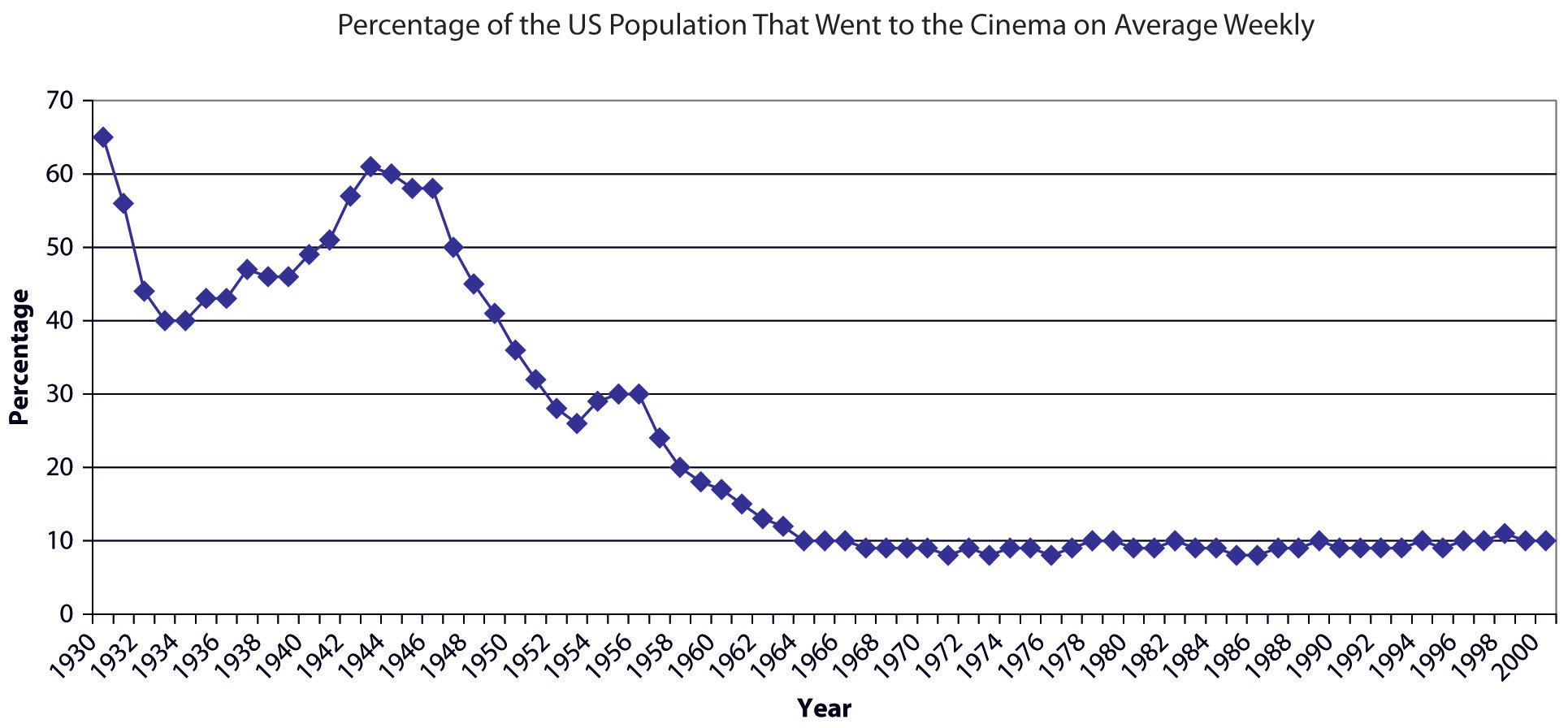

During the 1930s and 1940s, cinema was the principal form of popular entertainment, with people often attending cinemas twice a week. Ornate ’super’ cinemas or ‘picture palaces’, offering extra facilities such as cafés and ballrooms, came to towns and cities; many of them could hold over 3,000 people in a single auditorium.

In Britain, the highest attendances occurred in 1946, with over 31 million visits to the cinema each week.

What is the aspect ratio?

Thomas Edison had used perforated 35mm film in the Kinetoscope, and in 1909 this was adopted as the worldwide industry standard. The picture had a width-to-height relationship—known as the aspect ratio—of 4:3 or 1.33:1. The first number refers to the width of the screen, and the second to the height. So for example, for every 4 centimetres in width, there will be 3 in height.

With the advent of optical sound, the aspect ratio was adjusted to 1.37:1. This is known as the ‘Academy ratio’, as it was officially approved by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (the Oscars people) in 1932.

Although there were many experiments with other formats, there were no major changes in screen ratios until the 1950s.

How did cinema compete with television?

The introduction of television in America prompted a number of technical experiments designed to maintain public interest in cinema.

In 1952, the Cinerama process, using three projectors and a wide, deeply curved screen together with multi-track surround sound, was premiered. It had a very large aspect ratio of 2.59:1, giving audiences a greater sense of immersion, and proved extremely popular.

However, Cinerama was technically complex and therefore expensive to produce and show. Widescreen cinema was not widely adopted by the industry until the invention of CinemaScope in 1953 and Todd‑AO in 1955. Both processes used single projectors in their presentation.

CinemaScope ‘squeezed’ images on 35mm film; when projected, they were expanded laterally by the projector lens to fit the screen. Todd-AO used film with a width of 70mm. By the end of the 1950s, these innovations had effectively changed the shape of the cinema screen, with aspect ratios of either 2.35:1 or 1.66:1 becoming standard. Stereo sound, which had been experimented with in the 1940s, also became part of the new widescreen experience.

Specialist large-screen systems using 70mm film were also developed. The most successful of these has been IMAX, which as of 2020 has over 1,500 screens around the world. For many years IMAX cinemas have shown films specially made in its unique 2D or 3D formats but more recently they have shown popular mainstream feature films which have been digitally re-mastered in the IMAX format, often with additional scenes or 3D effects.

How have cinema attendance figures changed?

While cinemas had some success in fighting the competition of television, they never regained the position and influence they held in the 1930s and 40s, and over the next 30 years audiences dwindled. By 1984 cinema attendances in Britain had declined to one million a week.

By the late 2000s, however, that number had trebled. The first British multiplex was built in Milton Keynes in 1985, sparking a boom in out-of-town multiplex cinemas.

Today, most people see films on television, whether terrestrial, satellite or subscription video on demand (SVOD) services. Streaming film content on computers, tablets and mobile phones is becoming more common as it proves to be more convenient for modern audiences and lifestyles.

Although America still appears to be the most influential film industry, the reality is more complex. Many films are produced internationally—either made in various countries or financed by multinational companies that have interests across a range of media.

What’s next?

In the past 20 years, film production has been profoundly altered by the impact of rapidly improving digital technology. Most mainstream productions are now shot on digital formats with subsequent processes, such as editing and special effects, undertaken on computers.

Cinemas have invested in digital projection facilities capable of producing screen images that rival the sharpness, detail and brightness of traditional film projection. Only a small number of more specialist cinemas have retained film projection equipment.

In the past few years there has been a revival of interest in 3D features, sparked by the availability of digital technology. Whether this will be more than a short-term phenomenon (as previous attempts at 3D in the 1950s and 1980s had been) remains to be seen, though the trend towards 3D production has seen greater investment and industry commitment than before.

Further reading

- Cinematography in the Science Museum Group collection

- The Lumière Brothers: Pioneers of cinema and colour photography , National Science and Media Museum blog

- Cinerama in the UK: The history of 3-strip cinema in Pictureville Cinema , National Science and Media Museum blog

- BFI Filmography—a complete history of UK feature film

- BFI National Archive

- Imperial War Museums film archive

Pictureville Cinema

Pictureville is the home of cinema at the National Science and Media Museum, showing everything from blockbusters to indie gems.

Robert Paul and the race to invent cinema

Discover the story of Robert Paul, the forgotten pioneer whose innovations earned him the title of ‘father of the British film industry’.

Cinema technology

Discover objects from our collection which illuminate the technological development of moving pictures.

- Part of the Science Museum Group

- Terms and conditions

- Privacy and cookies

- Modern Slavery Statement

- Web accessibility

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

A Brief History of Cinema

Published by Monica Collins Modified over 6 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "A Brief History of Cinema"— Presentation transcript:

Motion Pictures. A Technology Based on Illusion The Edison Lab motion picture camera Lumiere Brothers in France –Cinematographe projection device.

Animation Introduction to Flash Media

The History of Film. Thomas Edison Kinetoscope debuted in 1893 at the Chicago world’s fair 1894, Fred Ott’s Sneeze is the 1 st copyrighted film Robert.

Copyright © 2012, by Jay Seller, Ph.D.. In 1894 Thomas Edison and William Dickson invented the Kinetoscope and Vitascope 1895 Birth of Cinematography.

Chapter 8 Movies: Mass Producing Entertainment. Early Movie Technology 1870s and 1880s: Marey and Muybridge View View.

By Stephanie Bishop Chelsea Gehan Christiana Stratis.

Early Storytelling…. Everyone has a story to tell Oral tradition Greek mythology / Odyssey Written documents Egyptian hieroglyphics / papyrus Photography.

Early Storytelling…. Everyone Has a Story to Tell.

Film Straubhaar & LaRose.

1877: Eadweard Muybridge develops sequential photographs of horses in motion. Muybridge subsequently invents the zoöpraxiscope in 1879, a device for projecting.

Grade Trivia Best/Worst Films AFI Top 100 and Best Picture Winners of Last 10 years History of Film.

By: Kaylor Ward. How it all Began A look at nearly two centuries of video production history. It all started in 1832 when Joseph Plateau invented the.

FILM POSTERS AND FILM MAGAZINE COVERS. FILM MAGAZINE COVERS Film magazine covers are a very useful marketing technique for promoting films, a magazine.

Question 3: What kind of media institution might distribute your media product and why? The Driver Tabitha Green The driver opening title sequence.

Research- Film Posters. Film posters are a form of promotion just like a film trailer. Because a film poster is a physical piece and is not a film piece,

Where the movies came from….. Magic Lanterns Entertainment before Film…. Vaudeville: live stage performance with different acts put together, such as.

History of Acting for Camera! By Lacy Goode, Josh McDaniel, and Becky Gula.

Birth of Cinema: 1890s Edison and the Kinetoscope Biograph and filmmaking in…New Jersey? Edwin Porter Lumiere Brothers popularize public screenings French.

International Baccalaureate Film Studies “Cinema is the most beautiful fraud in the world.” – Jean-Luc Godard.

History of Film Beginnings to First Photographs of Motion *1877 and 1878 by Eadweard Muybridge, a British photographer working in California who.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.2 The History of Movies

Learning objectives.

- Identify key points in the development of the motion picture industry.

- Identify key developments of the motion picture industry and technology.

- Identify influential films in movie history.

The movie industry as we know it today originated in the early 19th century through a series of technological developments: the creation of photography, the discovery of the illusion of motion by combining individual still images, and the study of human and animal locomotion. The history presented here begins at the culmination of these technological developments, where the idea of the motion picture as an entertainment industry first emerged. Since then, the industry has seen extraordinary transformations, some driven by the artistic visions of individual participants, some by commercial necessity, and still others by accident. The history of the cinema is complex, and for every important innovator and movement listed here, others have been left out. Nonetheless, after reading this section you will understand the broad arc of the development of a medium that has captured the imaginations of audiences worldwide for over a century.

The Beginnings: Motion Picture Technology of the Late 19th Century

While the experience of watching movies on smartphones may seem like a drastic departure from the communal nature of film viewing as we think of it today, in some ways the small-format, single-viewer display is a return to film’s early roots. In 1891, the inventor Thomas Edison, together with William Dickson, a young laboratory assistant, came out with what they called the kinetoscope , a device that would become the predecessor to the motion picture projector. The kinetoscope was a cabinet with a window through which individual viewers could experience the illusion of a moving image (Gale Virtual Reference Library) (British Movie Classics). A perforated celluloid film strip with a sequence of images on it was rapidly spooled between a light bulb and a lens, creating the illusion of motion (Britannica). The images viewers could see in the kinetoscope captured events and performances that had been staged at Edison’s film studio in East Orange, New Jersey, especially for the Edison kinetograph (the camera that produced kinetoscope film sequences): circus performances, dancing women, cockfights, boxing matches, and even a tooth extraction by a dentist (Robinson, 1994).

The Edison kinetoscope.

todd.vision – Kinetoscope – CC BY 2.0.

As the kinetoscope gained popularity, the Edison Company began installing machines in hotel lobbies, amusement parks, and penny arcades, and soon kinetoscope parlors—where customers could pay around 25 cents for admission to a bank of machines—had opened around the country. However, when friends and collaborators suggested that Edison find a way to project his kinetoscope images for audience viewing, he apparently refused, claiming that such an invention would be a less profitable venture (Britannica).

Because Edison hadn’t secured an international patent for his invention, variations of the kinetoscope were soon being copied and distributed throughout Europe. This new form of entertainment was an instant success, and a number of mechanics and inventors, seeing an opportunity, began toying with methods of projecting the moving images onto a larger screen. However, it was the invention of two brothers, Auguste and Louis Lumière—photographic goods manufacturers in Lyon, France—that saw the most commercial success. In 1895, the brothers patented the cinématographe (from which we get the term cinema ), a lightweight film projector that also functioned as a camera and printer. Unlike the Edison kinetograph, the cinématographe was lightweight enough for easy outdoor filming, and over the years the brothers used the camera to take well over 1,000 short films, most of which depicted scenes from everyday life. In December 1895, in the basement lounge of the Grand Café, Rue des Capucines in Paris, the Lumières held the world’s first ever commercial film screening, a sequence of about 10 short scenes, including the brother’s first film, Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory , a segment lasting less than a minute and depicting workers leaving the family’s photographic instrument factory at the end of the day, as shown in the still frame here in Figure 8.3 (Encyclopedia of the Age of Industry and Empire).

Believing that audiences would get bored watching scenes that they could just as easily observe on a casual walk around the city, Louis Lumière claimed that the cinema was “an invention without a future (Menand, 2005),” but a demand for motion pictures grew at such a rapid rate that soon representatives of the Lumière company were traveling throughout Europe and the world, showing half-hour screenings of the company’s films. While cinema initially competed with other popular forms of entertainment—circuses, vaudeville acts, theater troupes, magic shows, and many others—eventually it would supplant these various entertainments as the main commercial attraction (Menand, 2005). Within a year of the Lumières’ first commercial screening, competing film companies were offering moving-picture acts in music halls and vaudeville theaters across Great Britain. In the United States, the Edison Company, having purchased the rights to an improved projector that they called the Vitascope , held their first film screening in April 1896 at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall in Herald Square, New York City.

Film’s profound impact on its earliest viewers is difficult to imagine today, inundated as many are by video images. However, the sheer volume of reports about the early audience’s disbelief, delight, and even fear at what they were seeing suggests that viewing a film was an overwhelming experience for many. Spectators gasped at the realistic details in films such as Robert Paul’s Rough Sea at Dover , and at times people panicked and tried to flee the theater during films in which trains or moving carriages sped toward the audience (Robinson). Even the public’s perception of film as a medium was considerably different from the contemporary understanding; the moving image was an improvement upon the photograph—a medium with which viewers were already familiar—and this is perhaps why the earliest films documented events in brief segments but didn’t tell stories. During this “novelty period” of cinema, audiences were more interested by the phenomenon of the film projector itself, so vaudeville halls advertised the kind of projector they were using (for example “The Vitascope—Edison’s Latest Marvel”) (Balcanasu, et. al.), rather than the names of the films (Britannica Online).

Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory: One of the first films viewed by an audience.

Craig Duffy – Workers Leaving The Lumiere Factory – CC BY-NC 2.0.

By the close of the 19th century, as public excitement over the moving picture’s novelty gradually wore off, filmmakers were also beginning to experiment with film’s possibilities as a medium in itself (not simply, as it had been regarded up until then, as a tool for documentation, analogous to the camera or the phonograph). Technical innovations allowed filmmakers like Parisian cinema owner Georges Méliès to experiment with special effects that produced seemingly magical transformations on screen: flowers turned into women, people disappeared with puffs of smoke, a man appeared where a woman had just been standing, and other similar tricks (Robinson).

Not only did Méliès, a former magician, invent the “ trick film ,” which producers in England and the United States began to imitate, but he was also the one to transform cinema into the narrative medium it is today. Whereas before, filmmakers had only ever created single-shot films that lasted a minute or less, Méliès began joining these short films together to create stories. His 30-scene Trip to the Moon (1902), a film based on a Jules Verne novel, may have been the most widely seen production in cinema’s first decade (Robinson). However, Méliès never developed his technique beyond treating the narrative film as a staged theatrical performance; his camera, representing the vantage point of an audience facing a stage, never moved during the filming of a scene. In 1912, Méliès released his last commercially successful production, The Conquest of the Pole , and from then on, he lost audiences to filmmakers who were experimenting with more sophisticated techniques (Encyclopedia of Communication and Information).

Georges Méliès’s Trip to the Moon was one of the first films to incorporate fantasy elements and to use “trick” filming techniques, both of which heavily influenced future filmmakers.

The Nickelodeon Craze (1904–1908)

One of these innovative filmmakers was Edwin S. Porter, a projectionist and engineer for the Edison Company. Porter’s 12-minute film, The Great Train Robbery (1903), broke with the stagelike compositions of Méliès-style films through its use of editing, camera pans, rear projections, and diagonally composed shots that produced a continuity of action. Not only did The Great Train Robbery establish the realistic narrative as a standard in cinema, it was also the first major box-office hit. Its success paved the way for the growth of the film industry, as investors, recognizing the motion picture’s great moneymaking potential, began opening the first permanent film theaters around the country.

Known as nickelodeons because of their 5 cent admission charge, these early motion picture theaters, often housed in converted storefronts, were especially popular among the working class of the time, who couldn’t afford live theater. Between 1904 and 1908, around 9,000 nickelodeons appeared in the United States. It was the nickelodeon’s popularity that established film as a mass entertainment medium (Dictionary of American History).

The “Biz”: The Motion Picture Industry Emerges

As the demand for motion pictures grew, production companies were created to meet it. At the peak of nickelodeon popularity in 1910 (Britannica Online), there were 20 or so major motion picture companies in the United States. However, heated disputes often broke out among these companies over patent rights and industry control, leading even the most powerful among them to fear fragmentation that would loosen their hold on the market (Fielding, 1967). Because of these concerns, the 10 leading companies—including Edison, Biograph, Vitagraph, and others—formed the Motion Picture Patents Company (MPPC) in 1908. The MPPC was a trade group that pooled the most significant motion picture patents and established an exclusive contract between these companies and the Eastman Kodak Company as a supplier of film stock. Also known as the Trust , the MPPC’s goal was to standardize the industry and shut out competition through monopolistic control. Under the Trust’s licensing system, only certain licensed companies could participate in the exchange, distribution, and production of film at different levels of the industry—a shut-out tactic that eventually backfired, leading the excluded, independent distributors to organize in opposition to the Trust (Britannica Online).

The Rise of the Feature

In these early years, theaters were still running single-reel films, which came at a standard length of 1,000 feet, allowing for about 16 minutes of playing time. However, companies began to import multiple-reel films from European producers around 1907, and the format gained popular acceptance in the United States in 1912 with Louis Mercanton’s highly successful Queen Elizabeth , a three-and-a-half reel “feature,” starring the French actress Sarah Bernhardt. As exhibitors began to show more features—as the multiple-reel film came to be called—they discovered a number of advantages over the single-reel short. For one thing, audiences saw these longer films as special events and were willing to pay more for admission, and because of the popularity of the feature narratives , features generally experienced longer runs in theaters than their single-reel predecessors (Motion Pictures). Additionally, the feature film gained popularity among the middle classes, who saw its length as analogous to the more “respectable” entertainment of live theater (Motion Pictures). Following the example of the French film d’art , U.S. feature producers often took their material from sources that would appeal to a wealthier and better educated audience, such as histories, literature, and stage productions (Robinson).