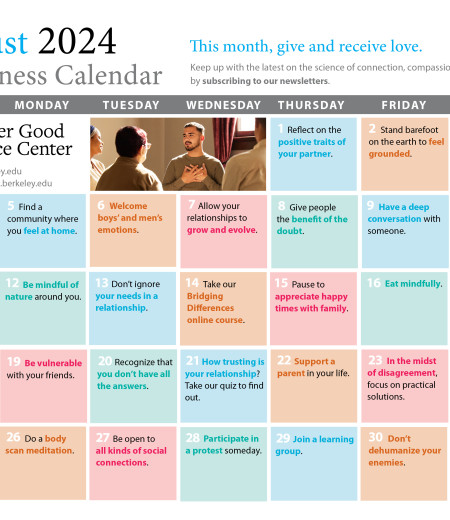

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

How Money Changes the Way You Think and Feel

The term “affluenza”—a portmanteau of affluence and influenza, defined as a “painful, contagious, socially transmitted condition of overload, debt, anxiety, and waste, resulting from the dogged pursuit of more”—is often dismissed as a silly buzzword created to express our cultural disdain for consumerism. Though often used in jest, the term may contain more truth than many of us would like to think.

Whether affluenza is real or imagined, money really does change everything, as the song goes—and those of high social class do tend to see themselves much differently than others. Wealth (and the pursuit of it) has been linked with immoral behavior—and not just in movies like The Wolf of Wall Street .

Psychologists who study the impact of wealth and inequality on human behavior have found that money can powerfully influence our thoughts and actions in ways that we’re often not aware of, no matter our economic circumstances. Although wealth is certainly subjective, most of the current research measures wealth on scales of income, job status, or socioeconomic circumstances, like educational attainment and intergenerational wealth.

Here are seven things you should know about the psychology of money and wealth.

More money, less empathy?

Several studies have shown that wealth may be at odds with empathy and compassion . Research published in the journal Psychological Science found that people of lower economic status were better at reading others’ facial expressions —an important marker of empathy—than wealthier people.

“A lot of what we see is a baseline orientation for the lower class to be more empathetic and the upper class to be less [so],” study co-author Michael Kraus told Time . “Lower-class environments are much different from upper-class environments. Lower-class individuals have to respond chronically to a number of vulnerabilities and social threats. You really need to depend on others so they will tell you if a social threat or opportunity is coming, and that makes you more perceptive of emotions.”

While a lack of resources fosters greater emotional intelligence, having more resources can cause bad behavior in its own right. UC Berkeley research found that even fake money could make people behave with less regard for others. Researchers observed that when two students played Monopoly, one having been given a great deal more Monopoly money than the other, the wealthier player expressed initial discomfort, but then went on to act aggressively, taking up more space and moving his pieces more loudly, and even taunting the player with less money.

Wealth can cloud moral judgment

It is no surprise in this post-2008 world to learn that wealth may cause a sense of moral entitlement. A UC Berkeley study found that in San Francisco—where the law requires that cars stop at crosswalks for pedestrians to pass—drivers of luxury cars were four times less likely than those in less expensive vehicles to stop and allow pedestrians the right of way. They were also more likely to cut off other drivers.

Another study suggested that merely thinking about money could lead to unethical behavior. Researchers from Harvard and the University of Utah found that study participants were more likely to lie or behave immorally after being exposed to money-related words.

“Even if we are well-intentioned, even if we think we know right from wrong, there may be factors influencing our decisions and behaviors that we’re not aware of,” University of Utah associate management professor Kristin Smith-Crowe, one of the study’s co-authors, told MarketWatch .

Wealth has been linked with addiction

While money itself doesn’t cause addiction or substance abuse, wealth has been linked with a higher susceptibility to addiction problems. A number of studies have found that affluent children are more vulnerable to substance-abuse issues , potentially because of high pressure to achieve and isolation from parents. Studies also found that kids who come from wealthy parents aren’t necessarily exempt from adjustment problems—in fact, research found that on several measures of maladjustment, high school students of high socioeconomic status received higher scores than inner-city students. Researchers found that these children may be more likely to internalize problems, which has been linked with substance abuse.

But it’s not just adolescents: Even in adulthood, the rich outdrink the poor by more than 27 percent.

Money itself can become addictive

The pursuit of wealth itself can also become a compulsive behavior. As psychologist Dr. Tian Dayton explained, a compulsive need to acquire money is often considered part of a class of behaviors known as process addictions, or “behavioral addictions,” which are distinct from substance abuse.

These days, the idea of process addictions is widely accepted. Process addictions are addictions that involve a compulsive and/or an out-of-control relationship with certain behaviors such as gambling, sex, eating, and, yes, even money.…There is a change in brain chemistry with a process addiction that’s similar to the mood-altering effects of alcohol or drugs. With process addictions, engaging in a certain activity—say viewing pornography, compulsive eating, or an obsessive relationship with money—can kickstart the release of brain/body chemicals, like dopamine, that actually produce a “high” that’s similar to the chemical high of a drug. The person who is addicted to some form of behavior has learned, albeit unconsciously, to manipulate his own brain chemistry.

While a process addiction is not a chemical addiction, it does involve compulsive behavior —in this case, an addiction to the good feeling that comes from receiving money or possessions—which can ultimately lead to negative consequences and harm the individual’s well-being. Addiction to spending money—sometimes known as shopaholism—is another, more common type of money-associated process addiction.

Wealthy children may be more troubled

Children growing up in wealthy families may seem to have it all, but having it all may come at a high cost. Wealthier children tend to be more distressed than lower-income kids, and are at high risk for anxiety, depression, substance abuse, eating disorders, cheating, and stealing. Research has also found high instances of binge-drinking and marijuana use among the children of high-income, two-parent, white families.

“In upwardly mobile communities, children are often pressed to excel at multiple academic and extracurricular pursuits to maximize their long-term academic prospects—a phenomenon that may well engender high stress,” writes psychologist Suniya Luthar in “The Culture Of Affluence.” “At an emotional level, similarly, isolation may often derive from the erosion of family time together because of the demands of affluent parents’ career obligations and the children’s many after-school activities.”

We tend to perceive the wealthy as “evil”

On the other side of the spectrum, lower-income individuals are likely to judge and stereotype those who are wealthier than themselves, often judging the wealthy as being “cold.” (Of course, it is also true that the poor struggle with their own set of societal stereotypes.)

Rich people tend to be a source of envy and distrust, so much so that we may even take pleasure in their struggles, according to Scientific American . According to a University of Pennsylvania study entitled “ Is Profit Evil? Associations of Profit with Social Harm ,” most people tend to link perceived profits with perceived social harm. When participants were asked to assess various companies and industries (some real, some hypothetical), both liberals and conservatives ranked institutions perceived to have higher profits with greater evil and wrongdoing across the board, independent of the company or industry’s actions in reality.

Money can’t buy happiness (or love)

We tend to seek money and power in our pursuit of success (and who doesn’t want to be successful, after all?), but it may be getting in the way of the things that really matter: happiness and love.

There is no direct correlation between income and happiness. After a certain level of income that can take care of basic needs and relieve strain ( some say $50,000 a year , some say $75,000 ), wealth makes hardly any difference to overall well-being and happiness and, if anything, only harms well-being: Extremely affluent people actually suffer from higher rates of depression . Some data has suggested money itself doesn’t lead to dissatisfaction—instead, it’s the ceaseless striving for wealth and material possessions that may lead to unhappiness. Materialistic values have even been linked with lower relationship satisfaction .

But here’s something to be happy about: More Americans are beginning to look beyond money and status when it comes to defining success in life. According to a 2013 LifeTwist study , only around one-quarter of Americans still believe that wealth determines success.

This article originally appeared in the Huffington Post .

About the Author

Carolyn gregoire, you may also enjoy.

Does Wealth Reduce Compassion?

Are the Rich More Lonely?

Low-Income People Quicker to Show Compassion

What Inequality Does to Kids

When the Going Gets Tough, the Affluent Get Lonely

Why Does Happiness Inequality Matter?

Economic Sociology & Political Economy

The global community of academics, practitioners, and activists – led by dr. oleg komlik, the role of money in social life: morality and power in the world of the poor.

by Ariel Wilkis *

“Perhaps behind the coin is God.” — Jorge Luis Borges, The Zahir (1949)

*** Join Economic Sociology and Political Economy community via Facebook / Twitter / LinkedIn / Instagram / Tumblr

Share this:

One comment.

[…] as well as on Sandel’s What Money Can’t Buy, Barman’s Caring Capitalism, Wilkis’ The Moral Power of Money, Morduch and Schneider’s The Financial Diaries, and Sherman’s Uneasy […]

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Discover more from economic sociology & political economy.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

The New York Times

Economix | how money affects morality.

How Money Affects Morality

From Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus for 30 pieces of silver, to Bernard L. Madoff to the standard member of Congress fighting tirelessly to further the interests of campaign donors, human history is full of examples of money’s ability to weaken even the firmest ethical backbone.

Money sows mistrust. It ends friendships. Experiments have found that it encourages us to lie and cheat. As Karl Marx, the scourge of capitalism, noted, ‘‘Money then appears as the enemy of man and social bonds that pretend to self-subsistence.’’

Yet though we clearly understand money’s power to debase character, we have less certain a grasp on what it is about money that corrupts us so. Is it simply greed? Does the appetite for the more comfortable life that money can buy push us over the line?

A new study by researchers in organizational behavior from Harvard University and the University of Utah suggests an entirely different dynamic: the simple idea of money changes the way we think – weakening every other social bond.

The researchers performed a suite of experiments on several hundred undergraduates. First they exposed some to phrases like “she spends money liberally” or pictures that would make them think of money, and others to images and phrases that had nothing to do with the stuff.

Then they made them answer questions to flesh out whether their morals would flag in the presence of temptation, and how they articulated the behavior to themselves.

Sure enough, students who had been primed to think of money consistently exhibited weaker ethics. More interestingly, perhaps, they also framed their choices as products of cost-benefit analysis. In other words, they stepped out of morality

For instance, they were more likely to answer that they would filch a ream of paper from the university’s copying room. They were more likely to lie for a financial gain and explain it to themselves as “primarily a business decision.”

“Social relations, which we assume are the fundamental basis of morality, can become de-emphasized so that moral considerations are obscured,” the researchers wrote. “A cost-benefit analysis ensues which focuses on the self to the exclusion of others.”

Money, in other words, puts us in the frame of mind of Michael Corleone as he decides to enter the family business . “It’s not personal,” he tells his brother. “”It’s strictly business.”

What's Next

On Words: ‘Money and Morality’

December 3, 2021 • By Simone Polillo, [email protected] Simone Polillo, [email protected]

- Simone Polillo, [email protected]

Illustration by Alexandra Angelich, University Communications

Editor’s note: Welcome to this installment of “ On Words ,” an occasional series in which University of Virginia faculty members write about evocative words and phrases. Simone Polillo, a professor of sociology, teaches a course on money and morality and dives into that topic in this essay for UVA Today.

In late 1912, banker J.P. Morgan, at the height of his power, spoke at a U.S. Senate committee hearing investigating the “Money Trust,” the tightly knit network of bankers and industrialists who controlled much of the nation’s capital. This was a time in U.S. history with many parallels to today: Inequality was rising, corporations had stifled market competition and public discontent with the banks was growing.

Having been asked how banks grant loans, Morgan provocatively asserted, “A man [sic] I do not trust could not get credit from me on all the bonds of Christendom.”

Morgan was responding head-on to the accusation that personal relationships in the credit system only served the connected at the expense of outsiders and did little to improve public welfare. Instead of denying that social relationships were at the heart of banking, he gave a rationale as to why they should be: collateral (“all the bonds in Christendom”) was but a narrow indicator of the individual’s ability to pay back his or her debt. Through personal relationships, however, creditors could gain a better sense of the borrower’s creditworthiness. The potential for cheating would decrease – “character is everything,” Morgan was fond of saying.

In today’s world, Morgan’s perspective may seem outdated. For most of us, access to credit is regulated by algorithms that produce quantitative indicators of creditworthiness. Personal connections do not seem to be as central to everyday citizens’ access to banking services as they used to be – though the proverbial handshake may still seal a deal when the parties to the transaction belong to a rarified and small social elite, raising important questions about how inequality operates in the world of credit. The larger point that still rings true, however, is that creditworthiness, no matter how quantified and automated, is a type of moral judgment: getting credit – whether a personal loan, funding for college, or a mortgage – requires us to undergo a process of evaluation with an eye to understanding whether we are the “sort of person” who can pay the creditor back. It’s not just about how much money we make: it’s also about our credit history, and specifically what kinds of “mistakes” we have made in our past that would raise a flag to potential creditors.

Related Story

On Words: ‘Commerce’

We have come to accept that morality – a rather strict, even punitive kind of morality at that – is a way of governing credit – limiting or expanding access to it, regulating how it is used, and so on. And yet, when it comes to money – and it is money that passes hands in a credit transaction, after all – the idea that money and morality are just as intimately connected strikes us as dubious. We stand on the shoulders of giants when we take this position: Thinkers as different as Adam Smith, Karl Marx and Georg Simmel all made some version of the argument that whenever money is involved, that’s when morality stops. As Marx famously put it, with money, “all that is solid melts into air,” as money knows no boundaries; in fact, it transforms all relationships and experiences we consider to have intrinsic value into a quantitative metric, dissolving their distinctiveness and making them comparable . As sociologist Viviana Zelizer suggests, such views on money produce two perspectives on the relationship between the economy and our social world: first, a view whereby money “corrupts” anything it touches, lending credence to claims that money should be kept at bay from aspects of our lives we understand to have intrinsic or incommensurable value. Second, a view whereby money is “nothing but” money – once monetary evaluation takes root in a previously untouched sphere, its cold, rational logic will relentlessly take over.

Credit is not the same thing as money, and perhaps it is legitimate to accept that credit has moral dimensions that money does not have. There are, to be sure, important differences between the two: credit is granted upon a promise of future repayment, whereas money, once exchanged, completes the transaction (e.g. as a payment). By the same token, credit entails a bet (however informed) about the future, with all the uncertainty it might bring; and so, it binds creditor and debtor into something of a personal relationship, at least for the duration of the loan. Money, by contrast, once exchanged, terminates the transaction. And, especially in the case of cash, a monetary transaction can preserve the anonymity of the parties to the exchange.

Yet, these differences are more superficial than they appear to be. Money is often exchanged in the context of pre-existing, meaningful social relationships, as when you send a friend a gift card for their favorite store. Money, in a case like this, does not “corrupt” the relationship: it would be awkward, of course, if you were gifting your friend an actual stash of cash, but charging the amount to a gift card helps you avoid this sort of faux pas. Or consider the arcane, intricate and often-contested practices that constitute tipping culture in the United States – how much, when and who to tip are questions that can be rarely settled through simple quantitative calculations of the kinds Marx was so worried about. As my Department of Media Studies colleague Lana Swartz argues in her 2020 book about new forms of payment (“New Money: How Payment Became Social Media,” Yale University Press), exchanging money always entails exchanging information, and, in the process, creating a community she calls “transactional,” with its own idiosyncrasies, inside jokes, and yes, even its distinctive sense of the right way of using money.

There is another, important connection between credit and money that infuses money not only with morality, but with politics. Political economists and sociologists have long argued that cash is a special form of credit: It is general credit backed by the authority and power of the national government (the state). The deeper point is not only that governments issue money: It is rather that political communities can decide, collectively, how much and what kind of money they should issue to finance projects the community really cares about. Money, that is, is a democratic tool. When J.P. Morgan emphasized the link between reputation and credit, he forgot to add that credit has social sources, and so it can be directed toward uses that are not reducible to what individuals would plan for their own benefit or self-interest. The morality of money, then, is another way of understanding the morality of politics. And while conventional views about politics can be as cynical about its morality as they are about the morality of money, understanding money in terms of political choices can also alert us to the ways money can empower us.

Media Contact

University News Senior Associate Office of University Communications

[email protected] (434) 243-9935

Article Information

August 17, 2024

You May Also Like

On Words: Leadership

On Words: ‘Bad’ Words and Why We Should Study Them

On Words: What Does ‘Meme’ Mean?

Ethics and Psychology

Where ethics is more than a code

Welcome to the Nexus of Ethics, Psychology, Morality, Philosophy and Health Care

Wednesday, june 19, 2013, how money affects morality.

- Utility Menu

Michael J. Sandel

Anne t. and robert m. bass professor of government.

- What Money Can't Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets

Should we pay children to read books or to get good grades? Should we put a price on human life to decide how much pollution to allow? Is it ethical to pay people to test risky new drugs or to donate their organs? What about hiring mercenaries to fight our wars, outsourcing inmates to for-profit prisons, auctioning admission to elite universities, or selling citizenship to immigrants willing to pay? In his New York Times bestseller What Money Can't Buy , Michael J. Sandel takes up one of the biggest ethical questions of our time: Isn't there something wrong with a world in which everything is for sale? If so, how can we prevent market values from reaching into spheres of life where they don't belong? What are the moral limits of markets? In recent decades, market values have crowded out nonmarket norms in almost every aspect of life. Without quite realizing it, Sandel argues, we have drifted from having a market economy to being a market society. In Justice , an international bestseller, Sandel showed himself to be a master at illuminating, with clarity and verve, the hard moral questions we confront in our everyday lives. Now, in What Money Can't Buy , he provokes a debate that's been missing in our market-driven age: What is the proper role of markets in a democratic society, and how can we protect the moral and civic goods that markets do not honor and money cannot buy?

“In a culture mesmerized by the market, Sandel’s is the indispensable voice of reason…. What Money Can’t Buy …must surely be one of the most important exercises in public philosophy in many years.”

--John Gray, New Statesman

Sandel, “the most famous teacher of philosophy in the world, [has] shown that it is possible to take philosophy into the public square without insulting the public’s intelligence…. [He] is trying to force open a space for a discourse on civic virtue that he believes has been abandoned by both left and right.”

--Michael Ignatieff, The New Republic

“ Brilliant, easily readable, beautifully delivered and often funny,…an indispensable book on the relationship between morality and economics.”

--David Aaronovitch, The Times (London)

“Sandel is probably the world’s most relevant living philosopher.”

--Michael Fitzgerald, Newsweek

“Michael Sandel’s What Money Can’t Buy is a great book and I recommend every economist to read it…. The book is brimming with interesting examples that make you think. I read this book cover to cover in less than 48 hours. And I have written more marginal notes than for any book I have read in a long time.”

--Timothy Besley, Professor of Economics, London School of Economics, Journal of Economics Literature

What Money Can’t Buy is that rare thing: a work of philosophy addressed to non-philosophers that is neither superficial nor condescending. Its prose is clear and elegant. Its message is simple and direct. Yet the questions it raises are deep ones…. What Money Can’t Buy is, among other things, a narrative of changing social mores in the style of Montesquieu or Tocqueville.”

--Chris Edward Skidelsky, Philosophy

Sandel “is such a gentle critic that he merely asks us to open our eyes…. Yet What Money Can’t Buy makes it clear that market morality is an exceptionally thin wedge…. Sandel is pointing out…[a] quite profound change in society.”

--Jonathan V. Last, The Wall Street Journal

“ What Money Can’t Buy is the work of a truly public philosopher…. [It] recalls John Kenneth Galbraith’s influential 1958 book, The Affluent Society …. Galbraith lamented the impoverishment of the public square. Sandel worries about its abandonment—or, more precisely, its desertion by the more fortunate and capable among us…. [A]n engaging, compelling read, consistently unsettling,…it reminds us how easy it is to slip into a purely material calculus about the meaning of life and the means we adopt in pursuit of happiness.”

--David M. Kennedy, Professor of History Emeritus, Stanford University, Democracy: A Journal of Ideas

Sandel “is currently the most effective communicator of ideas in English.”

--Editorial, The Guardian

“[An] important book…. Michael Sandel is just the right person to get to the bottom of the tangle of moral damage that is being done by markets to our values.”

--Jeremy Waldron, The New York Review of Books

“Michael Sandel is probably the most popular political philosopher of his generation…. The attention Sandel enjoys is more akin to a stadium-filling self-help guru than a philosopher. But rather than instructing his audiences to maximize earning power or balance their chakras, he challenges them to address fundamental questions about how society is organized…. His new book [ What Money Can’t Buy ] offers an eloquent argument for morality in public life.”

--Andrew Anthony, The Observer (London)

“ What Money Can’t Buy is replete with examples of what money can, in fact, buy…. Sandel has a genius for showing why such changes are deeply important.”

--Martin Sandbu, Financial Times

Michael Sandel is “one of the leading political thinkers of our time…. Sandel’s new book is What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets , and I recommend it highly. It’s a powerful indictment of the market society we have become, where virtually everything has a price.”

--Michael Tomasky, The Daily Beast

“To understand the importance of [Sandel’s] purpose, you first have to grasp the full extent of the triumph achieved by market thinking in economics, and the extent to which that thinking has spread to other domains. This school sees economics as a discipline that has nothing to do with morality, and is instead the study of incentives, considered in an ethical vacuum. Sandel's book is, in its calm way, an all-out assault on that idea…. Let's hope that What Money Can't Buy , by being so patient and so accumulative in its argument and its examples, marks a permanent shift in these debates.”

--John Lancaster, The Guardian

“Sandel is among the leading public intellectuals of the age. He writes clearly and concisely in prose that neither oversimplifies nor obfuscates…. Sandel asks the crucial question of our time: ‘Do we want a society where everything is up for sale? Or are there certain moral and civic goods that markets do not honor and money cannot buy?’”

--Douglas Bell, The Globe and Mail (Toronto)

“[D]eeply provocative and intellectually suggestive…. What Sandel does…is to prod us into asking whether we have any reason for drawing a line between what is and what isn’t exchangeable, what can’t be reduced to commodity terms…. [A] wake-up call to recognize our desperate need to rediscover some intelligible way of talking about humanity.”

--Rowan Williams, Prospect

“There is no more fundamental question we face than how to best preserve the common good and build strong communities that benefit everyone. Sandel's book is an excellent starting place for that dialogue.”

--Kevin J. Hamilton, The Seattle Times

“Poring through Harvard philosopher Michael Sandel's new book. . . I found myself over and over again turning pages and saying, 'I had no idea.' I had no idea that in the year 2000, 'a Russian rocket emblazoned with a giant Pizza Hut logo carried advertising into outer space.’. . . I knew that stadiums are now named for corporations, but had no idea that now 'even sliding into home is a corporate-sponsored event.'. . . I had no idea that in 2001 an elementary school in New Jersey became America's first public school 'to sell naming rights to a corporate sponsor.' Why worry about this trend? Because, Sandel argues, market values are crowding out civic practices.”

—Thomas Friedman, New York Times

“An exquisitely reasoned, skillfully written treatise on big issues of everyday life.”

-- Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“In his new book, Michael Sandel —the closest the world of political philosophy comes to a celebrity — argues that we now live in a society where ‘almost everything can be bought and sold.’ As markets have infiltrated more parts of life, Sandel believes we have shifted from a market economy to ‘a market society,’ turning the world — and most of us in it — into commodities. And when Sandel proselytizes, the world listens…. Sandel’s ideas could hardly be more timely.

-- Rosamund Urwin, Evening Standard (London)

“ What Money Can’t Buy is an excellent book…. Drawing upon a vast amount of fascinating empirical examples…Sandel explains why markets and market reasoning should not govern the distribution and allocation of all our social goods. He invites us to a renewed discussion of market principles in the public sphere…. The book is a clear, sharp and timely attack on the cult of the market which has been spreading since the 1970s.

--Christian Olaf Christiansen and Patrick J. L. Cockburn, European Journal of Social Theory

“The renowned political philosopher Michael Sandel asks what has become a pressing question for our age: Is there anything money can’t buy? .... Sandel’s central worry is that commodification is corrupting. There are certain goods, such as education, nature, health and sex, and certain approaches to life…that instantiate values and norms that are fundamentally incompatible with those that we associate with markets. When markets interfere with these goods and approaches to life they ‘crowd out’ the appropriate values and norms and thereby corrupt and diminish their value…. Sandel has made a useful and I think lasting contribution.”

--Prince Saprai, International Journal of Law in Context

Recent Publications

- Michael Sandel: ‘The energy of Brexiteers and Trump is born of the failure of elites'

- Market Reasoning as Moral Reasoning: Why Economists Should Re-engage with Political Philosophy

- The Moral Economy of Speculation: Gambling, Finance, and the Common Good

- What Isn’t for Sale?

- Obama and Civic Idealism

- News Releases

Morals versus money: How we make social decisions

University of Zurich

Our actions are guided by moral values. However, monetary incentives can get in the way of our good intentions. Neuroeconomists at the University of Zurich have now investigated in which area of the brain conflicts between moral and material motives are resolved. Their findings reveal that our actions are more social when these deliberations are inhibited.

When donating money to a charity or doing volunteer work, we put someone else's needs before our own and forgo our own material interests in favor of moral values. Studies have described this behavior as reflecting either a personal predisposition for altruism, an instrument for personal reputation management, or a mental trade-off of the pros and cons associated with different actions.

Impact of electromagnetic stimulation on donating behavior

A research team led by UZH professor Christian Ruff from the Zurich Center for Neuroeconomics has now investigated the neurobiological origins of unselfish behavior. The researchers focused on the right Temporal Parietal Junction (rTPJ) - an area of the brain that is believed to play a crucial role in social decision-making processes. To understand the exact function of the rTPJ, they engineered an experimental set-up in which participants had to decide whether and how much they wanted to donate to various organizations. Through electromagnetic stimulation of the rTPJ, the researchers were then able to determine which of the three types of considerations - predisposed altruism, reputation management, or trading off moral and material values - are processed in this area of the brain.

Moral by default, money by deliberation

The researchers found that people have a moral preference for supporting good causes and not wanting to support harmful or bad causes. However, depending on the strength of the monetary incentive, people will at one point switch to selfish behavior. When the authors reduced the excitability of the rTPJ using electromagnetic stimulation, the participants' moral behavior remained more stable.

"If we don't let the brain deliberate on conflicting moral and monetary values, people are more likely to stick to their moral convictions and aren't swayed, even by high financial incentives," explains Christian Ruff. According to the neuroeconomist, this is a remarkable finding, since: "In principle, it's also conceivable that people are intuitively guided by financial interests and only take the altruistic path as a result of their deliberations."

Brain region mediates conflicts

Although people's decisions were more social when they thought that their actions were being watched, this behavior was not affected by electromagnetic stimulation of the rTPJ. This means that considerations regarding one's reputation are processed in a different area of the brain. In addition, the electromagnetic stimulation led to no difference in the general motivation to help. Therefore, the authors concluded that the rTPJ is not home to altruistic motives per se, but rather to the ability to trade off moral and material values.

Experimental set-up

In the experimental set-up, the participants received money and were then presented with the opportunity to donate a varying sum to a charitable cause, at a cost to themselves, or donate a sum to an organization that supports the use of firearms, in which case they were rewarded. Some of these decisions were taken while other participants were watching, whereas others were taken in secret.

The researchers then analyzed the decisions the participants took, determining the monetary thresholds at which the participants switched from altruistic to selfish behavior. They compared these findings in settings with and without magnetic stimulation of the rTPJ area.

10.7554/eLife.40671

Disclaimer: AAAS and EurekAlert! are not responsible for the accuracy of news releases posted to EurekAlert! by contributing institutions or for the use of any information through the EurekAlert system.

Original Source

The Morality of Money

An Exploration in Analytic Philosophy

- © 2008

- Adrian Walsh 0 ,

- Tony Lynch 1

University of New England, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

2727 Accesses

20 Citations

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

About this book

Similar content being viewed by others.

Rescuing tracking theories of morality

Iris Murdoch and the Varieties of Virtue Ethics

Looking Back and the Way Ahead

- oral discourse

Table of contents (9 chapters)

Front matter, introduction.

Adrian Walsh, Tony Lynch

Money, Commerce and Moral Theory

The profit-motive and morality, usury and the ethics of interest-taking, the morality of pricing: just prices and moral traders, money, commodification and the corrosion of value: an examination of the sacred and intrinsic value, money-measurement as the moral problem, the charge of ‘economic moralism’: might the invisible hand eliminate the need for a morality of money, back matter, authors and affiliations, about the authors, bibliographic information.

Book Title : The Morality of Money

Book Subtitle : An Exploration in Analytic Philosophy

Authors : Adrian Walsh, Tony Lynch

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230227804

Publisher : Palgrave Macmillan London

eBook Packages : Palgrave Religion & Philosophy Collection , Philosophy and Religion (R0)

Copyright Information : Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited 2008

Hardcover ISBN : 978-0-230-53543-5 Published: 31 July 2008

Softcover ISBN : 978-0-230-53544-2 Published: 31 July 2008

eBook ISBN : 978-0-230-22780-4 Published: 31 July 2008

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : VIII, 255

Topics : Ethics , Moral Philosophy , Economic Theory/Quantitative Economics/Mathematical Methods , Analytic Philosophy

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Corporations

Does our system of credit and money make upward social mobility possible for anyone willing to work hard? Or is it just a big Ponzi scheme? Are corporations the essential structures necessary to harness the capital, energy, intelligence, and leadership on a scale large enough to make and market the inventions that define modern life? Or are they just devices for evading responsibility and rewarding greed? Ken and John put these questions and more to Neil Malhotra from the Stanford Graduate School of Business, in a program recorded in front of a live audience at the Classic Residence by Hyatt in Palo Alto, California.

Listening Notes

What do money and morality have to do with each other? What are the ethics of business? What obligations do corporations have to society as a whole? Was the recent financial meltdown a result of immoral behavior? In this edition of Philosophy Talk, John and Ken delve into these questions with the help of a live audience and guest Neil Malhotra, Assistant Professor of Political Economy at the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

The show begins with a discussion of corporations as moral agents. Should corporations be treated as people, as full moral agents held responsible for their actions? John argues that corporations are not people but rather devices to insulate people from the effects of their own decisions. Ken, in the spirit of Locke, argues that people are defined as intelligent beings, capable of reason and reflection, with the ability of self recognition at different times and places. Thus, he argues, it is metaphysically bizarre to call corporations people. John agrees, but shifts the conversation from metaphysics to morals, questioning whether corporations should be responsible to just their shareholders or to the entire community.

Professor Neil Malhotra joins the discussion concerning moral and economic incentives for corporations, grounded in the case of the subprime mortgage crisis. Under law, corporations are beholden only to their shareholders, instead of the larger pool of stakeholders, such as consumers, taxpayers, and third parties. The shareholder model, Malhotra says, encourages short-term thinking, as the price of a stock share is reported every quarter. Other countries, notably those with stronger traditions of family owned businesses, have adopted the stakeholder model.

The show concludes with a comparison of the European and American economic systems, noting the tradeoff between social welfare and social goods. While the European economy would seem to stand on higher moral ground by providing social services, the U.S. economy is much more dynamic, with more growth and innovation. John poses the questions, what if a firm decided to operate on a purely moral basis? Would profits noticeably differ? How can a corporation balance moral and economic incentives, so its actions have the most benefit and the least harm?

- Roving Philosophical Report (Seek to 6:51): Rina Palta speaks with Paul Perez, Managing Director of Northern Trust, about the role of trust in the subprime mortgage crisis. Perez argues that morality and a healthy economy are mutually dependent.

- 60-Second Philosopher (Seek to 49:57): Ian Shoales discusses the corporation and its role in society, tracing its origin from boroughs, guilds, and monasteries, to the East India Trade Company, to the contemporary American corporation motivated solely by profit.

Get Philosophy Talk

Sunday at 11am (Pacific) on KALW 91.7 FM , San Francisco, and rebroadcast on many other stations nationwide

Full episode downloads via Apple Music and abbreviated episodes (Philosophy Talk Starters) via Apple Podcasts , Spotify , and Stitcher

Unlimited Listening

Buy the episode.

Neil Malhotra, Assistant Professor of Political Economy, Stanford Graduate School of Business |

Related Shows

The root of all evil, giving and keeping, related resources.

- Donaldson, Thomas (2008). Ethical Issues in Business: A Philosophical Approach.

- Friedman, Daniel (2008). Markets and Morals: An Evolutionary Account of the Modern World.

- (1776). The Wealth of Nations.

- (1749). The Theory of Moral Sentiments.

Web Resources

- Business Ethics in Knowledge@Wharton (The Wharton School's online business journal.)

- The Corporation.com (website of the film The Corporation (2010).)

- Friedman, Milton (1970). “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits.” The New York Times Magazine. ( download .pdf )

- Marcoux, Alexei (2008). “Business Ethics.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Bonus Content

Log in or register to post comments.

- Create new account

- Request new password

Upcoming Shows

#MeToo: Retribution, Accountability,...

Hildegard von Bingen

Summer Reading List 2024

Listen to the preview.

Essay on Money

Introduction to The Power and Perils of Money

“Where Money Talks, Values Listen.”

Money is a fundamental aspect of modern society, serving as the lifeblood of economies and a cornerstone of daily life. Money holds immense significance in our lives, from facilitating transactions to influencing social dynamics. In this essay, we delve into the multifaceted nature of money, exploring its origins, functions, and profound impact on individuals and society.

As we navigate the complexities of money, we’ll unravel its historical roots, examine its various forms and functions, and delve into its role as a catalyst for economic growth and social change. Furthermore, we’ll explore the intricacies of personal finance, discussing the importance of financial literacy and responsible money management in achieving financial stability and well-being.

Watch our Demo Courses and Videos

Valuation, Hadoop, Excel, Mobile Apps, Web Development & many more.

Beyond its economic implications, we’ll also explore the broader societal effects of money, including its role in shaping social hierarchies, perpetuating economic inequality, and influencing political landscapes. Ultimately, this essay aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of the significance of money in our lives, shedding light on its profound impact on both individual prosperity and societal dynamics.

Origin and Evolution of Money

Money has been an essential part of human civilizations for thousands of years in all its manifestations. From basic barter systems to complex financial tools of the present day, money has always been important. Understanding the origin and evolution of money provides crucial insights into its significance and impact on society.

1. Barter Economy and the Emergence of Money:

- Barter System: In primitive societies, individuals engaged in barter, exchanging goods and services based on mutual needs, with each person trading one commodity for another. Limitations of the barter system, including the “double coincidence of wants,” led to inefficiencies and logistical challenges.

- Evolution to Commodity Money: Commodity money emerged as a solution to the shortcomings of barter, with certain items, such as cattle, grains, or precious metals, gaining widespread acceptance as mediums of exchange. Commodity money possessed intrinsic value and was universally recognized, facilitating trade and commerce across regions.

2. Development of Metal Coins:

- Introduction of Metal Coins: Metal coins, particularly gold and silver, emerged as standardized forms of currency in ancient civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Egypt, and Greece. Metal coins facilitated trade by providing a convenient and durable medium of exchange, standardized in terms of weight and purity.

- Coinage and State Authority: The minting of coins became centralized under the authority of states and rulers, leading to the establishment of monetary systems and the issuing of official currency. Coinage symbolized the sovereignty and power of states, with rulers often inscribing their images and symbols on coins as a means of propaganda and control.

3. Transition to Fiat Money:

- Rise of Paper Money: With the expansion of trade and commerce, the need for a more flexible and portable form of money led to the introduction of paper currency. Paper money initially represented claims to a specific quantity of precious metals, serving as promissory notes issued by banks and governments.

- Decoupling from Precious Metals: Over time, central banks and governments gradually abandoned the linkage between paper money and precious metals, transitioning currencies to fiat money and deriving their value from the trust and confidence of users rather than intrinsic value. Adopting fiat money allowed for greater flexibility in monetary policy and facilitated the expansion of credit and financial markets.

4. Evolution of Digital and Cryptocurrencies:

- Digital Currency: Digital currencies, electronic records with monetary value saved in digital form, result from the Internet’s and electronic banking’s development. Digital currencies, such as electronic bank transfers and payment systems, revolutionized how money is transferred and accessed, offering convenience and efficiency.

- Cryptocurrencies: Blockchain -based cryptocurrencies, like Ethereum and Bitcoin , are examples of decentralized digital money. Cryptocurrencies provide increased privacy, security, and decentralization but also present regulatory and stability concerns because they function independently of governments and central banks.

The Basic Need for Money

- Meeting Basic Needs: Money is essential for meeting basic human needs, such as food, shelter, clothes, and healthcare. Access to money enables individuals to purchase necessary goods and services for survival and well-being, ensuring a decent standard of living.

- Facilitating Economic Transactions: Money serves as a medium of exchange, enabling the exchange of goods and services in the marketplace. It enables individuals to engage in economic transactions, buy goods, pay for services, and participate in economic activities that contribute to economic growth and development.

- Access to Education and Skills Development: Money is necessary for education and skills development opportunities. Investing in education and training enhances individuals’ knowledge, skills, and employability, leading to better job prospects and higher earning potential.

- Healthcare and Medical Services: Money is vital for healthcare services and medical treatment. Individuals require financial resources to pay for medical expenses, health insurance, and access to quality healthcare facilities, ensuring their physical well-being and addressing health-related concerns.

- Housing and Shelter: Money is essential for securing housing and shelter providing individuals and families with a safe and stable living environment. Access to affordable housing options requires financial resources for rent, mortgage payments, or property ownership, ensuring adequate housing for individuals and communities.

- Transportation and Mobility: Money facilitates transportation and mobility, enabling individuals to travel for work, education, healthcare, and recreational purposes. Access to transportation choices, such as public transit, vehicles, or ride-sharing services, requires financial resources to cover transportation costs and maintain mobility.

- Emergency Preparedness and Resilience: Money is crucial for building emergency funds and financial resilience. Having savings and financial resources enables individuals to prepare for unexpected expenses, emergencies, and financial setbacks, providing a safety net during challenging times.

- Social and Recreational Activities: Money plays a role in accessing social and recreational activities that contribute to overall well-being and quality of life. Participating in leisure activities, entertainment, and social events often requires financial resources to cover expenses related to leisure pursuits and social engagements.

The Role of Money in Society

Money is a cornerstone of societal structures, influencing economic activities, social relationships, and individual well-being. Its multifaceted role extends beyond a mere medium of exchange, encompassing various functions integral to modern societies’ functioning.

1. Economic Significance of Money:

- Facilitating Trade and Commerce: Money acts as a universally accepted medium of exchange, facilitating the soft flow of goods and facilities in the market. Eliminating the need for direct barter enhances efficiency and encourages specialization in production.

- Measurement of Value: Money provides a common unit of account, allowing for the standardized measurement of the value of different goods and services. This function enables individuals to compare prices, make informed decisions, and confidently engage in economic transactions.

- Economic Growth and Development: A stable and reliable monetary system fosters economic growth and development . Governments and central banks use monetary policy tools to regulate money supply, interest rates, and inflation to maintain economic stability.

2. Social Significance of Money:

- Influence on Social Status and Power: The possession of wealth and financial resources often correlates with social status and power within a community. Economic disparities can create social hierarchies, impacting individuals’ access to opportunities and resources.

- Impact on Lifestyle and Standard of Living: The availability of financial resources influences an individual’s lifestyle and standard of living. Money provides access to education, healthcare, housing, and other essential services, shaping the quality of life for individuals and communities.

3. Money and Personal Finance:

- Importance of Financial Literacy: Financial education empowers people to make informed decisions about earning, spending, saving, and investing. Understanding the principles of personal finance is essential for achieving financial security and long-term well-being.

- Managing Personal Finances: Budgeting, saving, and investing are key to effective personal finance management. Individuals must make strategic financial decisions to meet their short-term and long-term goals.

- Psychological Aspects of Money: People often tie money to their emotions and psychological well-being. Developing a healthy money mindset involves understanding one’s relationship with money and addressing any emotional factors that may impact financial decisions.

4. Impact of Money on Society:

- Economic Inequality: The distribution of wealth and income in society can contribute to economic inequality. Addressing issues of inequality requires a nuanced understanding of the role of money and the implementation of policies that promote equitable wealth distribution.

- Consumerism and Materialism: Money influences consumer behavior , contributing to a culture of consumerism and materialism. Society’s emphasis on material possessions can impact individuals’ values and priorities.

- Influence on Politics and Governance: Money plays a significant role in political processes, affecting campaigns, lobbying, and policy decisions. The intersection of money and politics raises questions about transparency, accountability, and the democratic process.

- Environmental Implications: Economic activities driven by the pursuit of profit can have environmental consequences. Balancing economic growth with environmental sustainability requires careful consideration of the environmental impact of monetary and economic policies.

Functions of Money

- Medium of Exchange

- Money is a widely acknowledged medium of exchange for goods and services, facilitating transactions between buyers and sellers.

- It eliminates the inefficiencies of barter by providing a common unit of value that simplifies the exchange process.

- Unit of Account:

- Money provides a standardized unit of measurement for the value of goods and services, permitting easy comparison of prices and making economic calculations more efficient.

- It enables individuals and businesses to express the relative worth of different goods and services in terms of a common currency.

- Store of Value:

- Money serves as a store of value, permitting individuals to hold and accumulate wealth over time.

- Unlike perishable goods or assets with fluctuating value, money retains its purchasing power over extended periods, providing a reliable means of preserving wealth.

- Standard of Deferred Payment:

- Money facilitates transactions involving future obligations by serving as a medium for deferred payments.

- Contracts, loans, and other financial agreements often stipulate payments in a specific currency, with money as the standard for settling debts and fulfilling obligations.

- Money’s high liquidity enables it to be readily convertible into goods, services, or other assets without experiencing a significant loss of value.

- Its liquidity enables individuals to quickly access funds for urgent expenses or investment opportunities, contributing to economic flexibility and efficiency.

- Measure of Value:

- Money is a measure of value, providing a common denominator for expressing the worth of different goods and services.

- Its role as a measure of value facilitates economic decision-making, allowing individuals to assess the relative utility and worth of various goods and services.

- Facilitates Specialization and Efficiency:

- Money enables specialization and division of labor by allowing individuals and businesses to focus on producing goods and assistance in which they have a comparative advantage.

- Specialization leads to increased productivity and efficiency, driving economic growth and prosperity.

- Portability and Durability:

- Money is highly portable and durable, making it a convenient medium of interaction for transactions of varying sizes and distances.

- The physical forms of money (such as coins and banknotes) and their digital representation ensure ease of transportation and storage, contributing to its widespread use in modern economies.

The Ethics and Morality of Money

While essential for economic transactions and societal functioning, money raises ethical and moral considerations beyond its economic utility. From wealth distribution issues to the impact of financial decisions on individuals and society, exploring the ethical dimensions of money sheds light on complex moral dilemmas and societal values.

- Wealth Distribution and Economic Inequality: One of the most significant ethical concerns about money is the unequal distribution of wealth and income within societies. Critics argue that extreme wealth disparities contribute to social injustice and perpetuate systemic inequalities, raising questions about fairness and equity.

- Social Responsibility of Wealth: Accumulating wealth brings with it a moral obligation to contribute to society’s well-being. Concepts like philanthropy, corporate social responsibility, and impact investing highlight the ethical imperative for individuals and organizations to use their financial resources for the greater good.

- Ethical Consumption and Consumerism: Consumerism fueled by the pursuit of material wealth raises ethical questions about consumption patterns’ environmental and social impact. Ethical consumption movements advocate for mindful spending and sustainable lifestyles that consider the broader consequences of consumer choices.

- Ethics in Financial Services: The financial industry operates within a complex ethical landscape, with issues like transparency, conflicts of interest, and fair treatment of clients coming under scrutiny. Ethical codes of conduct and regulations aim to promote integrity and trust in financial services, ensuring that financial professionals prioritize the interests of their clients.

- Debt and Financial Vulnerability: Ethical considerations arise in lending practices, particularly regarding the responsible provision of credit and the treatment of borrowers, especially those in vulnerable financial situations. Predatory lending practices and exploitative debt arrangements raise ethical concerns about the consequences of financial transactions on individuals’ well-being.

- Corruption and Financial Crime: Money laundering, bribery, and other forms of financial crime undermine the integrity of financial systems and pose ethical challenges to businesses, governments, and individuals. Ethical frameworks and legal regulations aim to combat financial corruption and promote accountability and transparency in financial transactions.

- Psychological Impact of Money: Money’s influence on individuals’ attitudes, behaviors, and relationships raises ethical questions about the psychological effects of wealth and materialism. The pursuit of wealth can lead to ethical dilemmas related to greed, envy, and the prioritization of financial gain over other values.

- Cryptocurrency and Ethical Considerations: Emerging digital currencies, such as cryptocurrencies, introduce new ethical considerations related to privacy, security, and the potential for illegal activities like money laundering and fraud. Ethical discussions surrounding cryptocurrencies also touch on financial inclusivity, decentralization, and the democratization of finance.

Financial Education

Financial education is essential to enable people to make informed decisions concerning their money, investments, and overall economic well-being. It covers many topics, from basic budgeting and savings to more complex concepts like investing, debt relief, and retirement planning. The need for financial literacy is huge in today’s complex financial world, where individuals are more accountable for their financial future.

- Foundational Knowledge: Basic financial concepts like income, expenses, budgeting, and savings are the first things students learn about when they start their financial education. Comprehending these underlying concepts establishes the foundation for prudent financial judgment and accountable handling of finances.

- Budgeting and Saving: Effective budgeting and saving are essential for financial education. Individuals learn how to create and stick to a budget, allocate funds for essential expenses, savings, and discretionary spending, and build an emergency fund to weather unforeseen financial challenges.

- Debt Management: Financial education teaches individuals about managing debt responsibly, including understanding different types of debt, interest rates, and repayment strategies. It emphasizes the importance of avoiding excessive debt and using credit wisely to maintain financial health.

- Investing and Wealth Accumulation: Investing is a key aspect of financial education, enabling individuals to grow their wealth over the long term. Topics covered may include understanding investment options (stocks, bonds, mutual funds, etc.), risk tolerance, asset allocation, and strategies for assembling a diversified investment portfolio.

- Retirement Planning: Financial education helps individuals plan for their future financial security, including retirement. It covers retirement savings vehicles (e.g., employer-sponsored retirement plans, IRAs), estimating retirement expenses, and developing a strategy to achieve retirement goals.

- Risk Management and Insurance: Understanding risk management and insurance is integral to financial education. Individuals learn about different types of insurance (e.g., health, life, property) and how insurance can mitigate financial risks and protect against unexpected events.

- Financial Decision-making: Financial education supplies individuals with the knowledge and skills to make instructed financial decisions based on their goals, values, and circumstances. It encourages critical thinking and evaluating financial products and services, empowering individuals to navigate the financial marketplace effectively.

- Economic Empowerment: Financial education is a tool for economic empowerment, particularly for marginalized communities and underserved populations. Promoting financial literacy and capability helps individuals build financial resilience, reduce vulnerability to financial exploitation, and achieve greater economic independence.

- Lifelong Learning: Financial education is a lifelong journey with changing financial circumstances and economic conditions. It emphasizes the importance of ongoing learning, staying informed about financial trends and developments, and adapting financial strategies as needed throughout life.

- Social and Policy Implications: Financial education has broader social and policy implications, influencing financial inclusion, economic mobility, and societal well-being. Policies that promote financial education in schools, workplaces, and communities can contribute to building a financially literate society and reducing financial disparities.

Money in the Digital Age

- Digital Payments and Transactions: The addition of digital payment methods, including mobile wallets, online banking, and peer-to-peer payment platforms, has reshaped the conduct of transactions. Digital payments offer convenience, speed, and accessibility, allowing individuals to transfer funds, make purchases, and manage finances seamlessly across various digital channels.

- Cryptocurrencies and Blockchain Technology: Cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin and Ethereum, represent a decentralized digital currency powered by blockchain technology. Blockchain technology enables secure, transparent, and tamper-proof transactions without intermediaries like banks or financial institutions.

- Financial Inclusion and Access: The digitalization of money can promote financial inclusion by delivering access to financial services for underserved populations. Digital payment platforms and mobile banking services empower individuals in small areas or underserved communities to participate in the formal financial system.

- Challenges and Risks: Despite the benefits, the digitalization of money presents challenges and risks, including cybersecurity threats, data privacy concerns, and regulatory challenges. Fraud, hacking, and data breaches highlight the importance of robust cybersecurity measures and regulatory frameworks to protect consumers and maintain trust in digital financial systems.

- Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs): Central banks are exploring the vision of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) as a digital alternative to traditional fiat currencies. CBDCs combine the advantages of digital currencies with the stability and regulatory oversight provided by central banks, potentially reshaping the future of money and monetary policy.

- Smart Contracts and Decentralized Finance (DeFi): Smart contracts, facilitated by blockchain technology, automate and enforce the words of contracts without intermediaries. Decentralized finance (DeFi) leverages blockchain and innovative contract technology to create decentralized financial services outside traditional banking systems, including lending, borrowing, and trading.

- Cross-Border Transactions and Remittances: Digital currency and blockchain technologies promise to stream international transfers and reduce expenses and inadequacies linked to conventional remittance systems. Cryptocurrencies and stablecoins offer an alternative means of transferring value globally, bypassing traditional banking channels and intermediaries.

- Regulatory Landscape and Policy Considerations: Governments and officials face regulatory hurdles due to the rapid evolution of digital currency. Regulatory frameworks must actively update to consider the changing landscape of digital finance to preserve consumer protection, financial stability, and compliance with know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML) regulations.

Money is a cornerstone of modern society, serving as a medium of exchange, store of value, and facilitator of economic activities. Its significance extends beyond financial transactions, impacting individuals’ access to basic needs, economic opportunities, and overall well-being. Understanding the multifaceted role of money is crucial for promoting financial literacy, responsible money management, and equitable access to financial resources in today’s complex socioeconomic landscape.

*Please provide your correct email id. Login details for this Free course will be emailed to you

By signing up, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy .

Valuation, Hadoop, Excel, Web Development & many more.

Forgot Password?

This website or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and required to achieve the purposes illustrated in the cookie policy. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to browse otherwise, you agree to our Privacy Policy

Explore 1000+ varieties of Mock tests View more

Submit Next Question

🚀 Limited Time Offer! - 🎁 ENROLL NOW

Money and Markets vs. Social Morals Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

How these assertions are true, works cited.

Michael Sandel was correct in asserting that some aspects of life should never be tainted by money. Money has a perverting effect that devalues human life as well as human relationships. Additionally, it leads to inequality and may even destroy relationships.

Several cultures illustrate the meaning of money by the way they treat it. Some of the results that emanate from excessive proliferation of money are both undesirable and untenable in today’s society.

Sandel (4) explained that the recent, global financial crisis illustrated the imperfections of the market economy. It proved that markets were not effective at allocating risks and was thus ill-suited for certain aspects of life. The proliferation of money into aspects of society that depend on other norms is the root cause of the financial crisis (Sandel 5).

These patterns have also created other crises in society like inequality and corruption. Polanyi (43) explains that liberal economic theorists made a mistake to assume that human behaviour is governed by the need to maximise profits. This is not true for several aspects of life. In fact, prior to the creation of free markets, societies were governed by the need for reciprocity or redistribution.

A typical case is a family in the Trobriand Islands. Persons in this culture focus on subsistence and redistribution through feasts. In other societies, people can be motivated by the need to enhance their national security. Therefore, profit maximisation would be secondary to this goal. The problem with excessive domination of money in society is the subversion of social relations.

When markets penetrate almost all dimensions of life, they may lead to inequality (Sandel 5). This is because money would be the key to success in all spheres. Such a means of exchange would make the difference between acquisition of basic needs and the lack of them. Affluence would dramatically affect the quality of one’s life and thus widen the gap between the rich and the poor.

Commoditisation of public land by enclosures limits access to this vital resource and thus causes dependence on others (employers) (Polanyi 102). Privatisation and sale of certain commodities, like public land, threatens society because it leads to unrest. This process of putting a price to communal land, through enclosures, increases its value, which makes it inaccessible to the large majority.

Many individuals may become frustrated at their inability to acquire property and thus revolt against property owners. Penetration of money into communal property may also lead to adverse environmental consequences such as pollution, deforestation, disruption of craftsmanship and housing.

Living in a pollution-free environment or having skilled and creating craftsmen are all goals that have nothing to do with profit-maximisation; they are instead pegged on human relations and well being.

Sandel (6) points out that money has a corrosive effect when it reaches other spheres of life because it fosters unwanted attitudes towards the items being exchanged. For instance, when private security firms replace army personnel in wars, countries may save their people’s lives, but this may devalue citizenship.

As such, money will have promoted a perverted attitude towards such a crucial ideology. Additionally, if potential mothers choose to pay surrogate mothers for their services regardless of their fertility status, then this devalues motherhood. When money enters such realms of life, it corrupts their true value.

Unlike what previous economists had stated, money is not value-free; every transaction means something to entities participating in it. In fact, the effect of the values that money creates is so influential that it may sometimes neutralise or eliminate the non –market values affecting that activity.

If money were involved in all human activities then it would ruin human relationships. Hart (13) explains that money was not always regarded as impersonal. In traditional societies, people often carried out transactions with individuals they knew. Therefore, they could exercise discretion over the nature or the kind of person that they interacted with.

However, modern society changed this when it was perceived that exchanges would take place in markets, where seemingly unattached individuals met anonymously and exchanged goods. Therefore, one would argue that the impersonal nature of this approach would lead to desirable effects. However, this is not true for several transactions because the state makes this discretion for an individual.

A person who qualifies for a loan from a bank proves that he or she is trustworthy and that he deserves the loan. Alternatively, if one receives payment from one’s employers, then the person testifies to his hard work and commitment to the organisation. Whenever an individual is exposed to a situation where he or she receives money for services rendered, then the transaction testifies to that person’s character.

Not many people understand this truth as they assume that money is impersonal. They also think that such factors only hold true for traditional societies which were highly interpersonal. Money sometimes masks the usefulness of human relationships and characteristics because of the anonymity it provides.

As a result, its proliferation in different aspects of interaction should be re-examined for effectiveness. Only the most prudent individuals will refrain from hiding behind the anonymity of money and truly look into the character of the person they are transacting with.

Zelizer (133) adds that money is not objective depending on the people using it and the activities they partake. For instance, if one won money in a lottery, they would spend that money in a different way than if a friend loaned them the money. Even recipients of money have a profound effect on how the money will be used.

For instance, a waitress can be tipped by a client but one cannot do the same to a policeman man as this would be perceived as a bribe. Additionally, one may have certain intentions for their money. For instance, they may opt to save it for a rainy day or pay rent with it. All these decisions prove that money is not an objective thing.

Therefore, individuals have the right to make decisions regarding how permissive they want to make money. They can make choices on the suitability of a certain activity to a market. Individuals ought to know that engaging in transactions does not delineate them from cultural and social constraints.

Since money has such a powerful effect, then its applicability in life ought to be done very selectively. Zelizer (18) elegantly says that “Money does serve as a key rational tool of the modern economic market; it also exists outside the sphere of the market and is profoundly influenced by social and cultural structures”. Since this is true, then its effect ought to be limited only to certain aspects of life.

Certain items should not be commoditised because money cannot reflect their true value. For instance, one cannot sell one’s baby as this would demean the value of that human life. No matter how unprepared one was for motherhood, it would be immoral to sell a child because that would undermine the value of that child.

All humans deserve to be treated with dignity and respect; consequently, selling them to others for a certain sum of money would be denying them that right.

Public goods are also activities that must be delineated from monetary transactions as they also reflect certain values. Introducing money into the system would destroy these values. For instance, one cannot pay another person to vote for them because this is one’s civic duty.

Public responsibilities cannot be quantified and sold to the highest bidder (Sandel 7). Mauss (67) explains that collective rights exist in almost all countries around the world. When an elderly person falls ill, he or she has the right to access certain forms of protection such as Medicare for the elderly.

These protections stem from the life and labour that a worker provided to his employer and his country in general. This labour is a gift which ought to be returned. Mauss (13) affirms that gift giving has a spirit known as hau. When an individual receives a gift, he or she experiences feelings of reciprocity that will prompt him to return the hau.

Likewise, when a worker has dedicated his entire life towards a certain career, then chances are that wages earned are not enough to compensate for this gift. Governments need to guarantee such workers another social benefit like health insurance in order to reciprocate their hau.

Therefore, public services ought to be perceived as purchases because they are a form of gift for the input that the worker gave throughout his life. On the flipside, if a government pays people unemployment benefits even before they start working, then chances are that the individuals will not experience feelings of reciprocity.

In this regard, they will become dependent on the state as no sense of duty will exist. When public services are treated as transactions, then an unhealthy relationship exists between the government and the beneficiaries. Money would destroy that sense of duty unless it is done in the context of gift-giving.

Money should not pervade all activities in society; the responsible thing to do is to make calculated choices about which activities are suitable for market economies and which ones are not. Society has a tendency to choose the easy way out because it does not involve the painstaking process of moral judgements. Markets have pervaded different aspects of society because they are non judgmental and unbiased.

However, if this state of affairs is left to continue, then chances are that societies will become more corrupt and more unequal. Commodities or transactions often imply rationality and other undesirable traits such as individualism, impersonal relations and material gain.

Conversely, gifts represent moral obligations, personal relations, collective responsibility and non monetary rewards. Gifts are the glue that holds a society together while markets and commodities drive them apart (Parry 55). Capitalism has contributed to excessive focus on commodities and little emphasis on human relationships. A balance ought to be restored in order to make society fair again.

Hart, Keith. “Money is always Personal and Impersonal.” Anthropology Today 23.5(2007): 12-16. Print.

Mauss, Marcel. The gift . London: Routledge, 1990. Print.

Parry, James. The gift, the Indian gift and the ‘Indian gift ‘. NS: Man, 1986. Print.

Polanyi, Karl. The great transformation. New York: Rinehart, 1944. Print.

Sandel, Michael. What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets. Harvard: HUP, 2010. Print.

Zelizer, Viviana. The Social Meaning of Money: pin money, paychecks, poor relief and other currencies. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997. Print.

- Canada Corporations Business Environment

- Can Levi’s be Cool Again?

- Sandel’s Analysis of Utilitarianism and Libertarianism

- "What's the Right Thing to Do?" by Michael Sandel

- Ethics in the Case against Perfection

- Real World Marketing with a Focus on Promotion

- Conflicts in FUBU Company

- Marketing Management and Strategy of L’Oreal

- Apple Inc. Smartphone Marketing Strategy in Australia