- Utility Menu

GA4 tracking code

- All URAF Opportunities

- CARAT (Opportunities Database)

- URAF Application Instructions

- URAF Calendar of Events and Deadlines

Writing Application Essays and Personal Statements

Some applications ask that you write an essay that draws on more personal reflections. These essays, sometimes called Personal Statements, are an opportunity to show the selection committee who you are as a person: your story, your values, your interests, and why you—and not your peer with a similar resume—are a perfect fit for this opportunity. These narrative essays allow you to really illustrate the person behind the resume, showcasing not only what you think but how you think.

Before you start writing, it’s helpful to really consider the goals of your personal statement:

- To learn more about you as a person: What would you like the selection committee to know about you that can't be covered by other application materials (e.g. resume, transcript, letters of recommendation)? What have been the important moments/influences throughout your journey that have led to where (and who!) you are?

- To learn how you think about the unsolved problems in your field of study/interest: What experiences demonstrate how you've been taught to think and how you tackle challenges?

- To assess whether you fit with the personal qualities sought by the selection committee: How can you show that you are thoughtful and mature with a good sense of self; that you embody the character, qualities, and experience to be personally ready to thrive in this experience (graduate school and otherwise)? Whatever opportunity you are seeking—going to graduate school, spending the year abroad, conducting public service—is going to be challenging intellectually, emotionally, and financially. This is your opportunity to show that you have the energy and perseverance to succeed.

In general, your job through your personal statement is to show, don’t tell the committee about your journey. If you choose to retell specific anecdotes from your life, focus on one or two relavant, formative experiences—academic, professional, extracurricular—that are emblematic of your development. The essay is where you should showcase the depth of your maturity, not the breadth—that's the resume's job!

Determining the theme of an essay

The personal statement is usually framed with an overarching theme. But how do you come up with a theme that is unique to you? Here are some questions to get you started:

- Question your individuality: What distinguishes you from your peers? What challenges have you overcome? What was one instance in your life where your values were called into question?

- Question your field of study: What first interested you about your field of study? How has your interest in the field changed and developed? How has this discipline shaped you? What are you most passionate about relative to your field?

- Question your non-academic experiences: Why did you choose the internships, clubs, or activites you did? And what does that suggest about what you value?

Once you have done some reflection, you may notice a theme emerging (justice? innovation? creativity?)—great! Be careful to think beyond your first idea, too, though. Sometimes, the third or fourth theme to come to your mind is the one that will be most compelling to center your essay around.

Writing style

Certainly, your personal statement can have moments of humor or irony that reflect your personality, but the goal is not to show off your creative writing skills or present you as a sparkling conversationalist (that can be part of your interview!). Here, the aim is to present yourself as an interesting person, with a unique background and perspective, and a great future colleague. You should still use good academic writing—although this is not a research paper nor a cover letter—but the tone can be a bit less formal.

Communicating your values

Our work is often linked to our own values, identities, and personal experiences, both positive and negative. However, there can be a vulnerability to sharing these things with strangers. Know that you don't have to write about your most intimate thoughts or experiences, if you don't want to. If you do feel that it’s important that a selection committee knows this about you, reflect on why you would like for them to know that, and then be sure that it has an organic place in your statement. Your passion will come through in how you speak about these topics and their importance in forming you as an individual and budding scholar.

- Getting Started

- Application Components

- Interviews and Offers

- Building On Your Experiences

- Applying FAQs

- Statement of Purpose, Personal Statement, and Writing Sample

Details about submitting a statement of purpose, personal statement, and a writing sample as part of your degree program application

- Dissertation

- Fellowships

- Maximizing Your Degree

- Before You Arrive

- First Weeks at Harvard

- Harvard Speak

- Pre-Arrival Resources for New International Students

- Alumni Council

- Student Engagement

- English Proficiency

- Letters of Recommendation

- Transcripts

- After Application Submission

- Applying to the Visiting Students Program

- Admissions Policies

- Cost of Attendance

- Express Interest

- Campus Safety

- Commencement

- Diversity & Inclusion Fellows

- Student Affinity Groups

- Recruitment and Outreach

- Budget Calculator

- Find Your Financial Aid Officer

- Funding and Aid

- Regulations Regarding Employment

- Financial Wellness

- Consumer Information

- Life Sciences

- Policies (Student Handbook)

- Student Center

- Title IX and Gender Equity

Statement of Purpose

The statement of purpose is very important to programs when deciding whether to admit a candidate. Your statement should be focused, informative, and convey your research interests and qualifications. You should describe your reasons and motivations for pursuing a graduate degree in your chosen degree program, noting the experiences that shaped your research ambitions, indicating briefly your career objectives, and concisely stating your past work in your intended field of study and in related fields. Your degree program of interest may have specific guidance or requirements for the statement of purpose, so be sure to review the degree program page for more information. Unless otherwise noted, your statement should not exceed 1,000 words.

Personal Statement

Please describe the personal experiences that led you to pursue graduate education and how these experiences will contribute to the academic environment and/or community in your program or Harvard Griffin GSAS. These may include social and cultural experiences, leadership positions, community engagement, equity and inclusion efforts, other opportunities, or challenges. Your statement should be no longer than 500 words.

Please note that there is no expectation to share detailed sensitive information and you should refrain from including anything that you would not feel at ease sharing. Please also note that the Personal Statement should complement rather than duplicate the content provided in the Statement of Purpose.

Visit Degree Programs and navigate to your degree program of interest to determine if a Personal Statement is required. The degree program pages will be updated by early September indicating if the Personal Statement is required for your program.

Writing Sample

Please visit Degree Programs and navigate to your degree program of interest to determine if a writing sample is required. When preparing your writing sample, be sure to follow program requirements, which may include format, topic, or length.

Share this page

Explore events.

Important Addresses

Harvard College

University Hall Cambridge, MA 02138

Harvard College Admissions Office and Griffin Financial Aid Office

86 Brattle Street Cambridge, MA 02138

Social Links

If you are located in the European Union, Iceland, Liechtenstein or Norway (the “European Economic Area”), please click here for additional information about ways that certain Harvard University Schools, Centers, units and controlled entities, including this one, may collect, use, and share information about you.

Application Tips

- Navigating Campus

- Preparing for College

- How to Complete the FAFSA

What to Expect After You Apply

- View All Guides

- Parents & Families

- School Counselors

- Información en Español

- Undergraduate Viewbook

- View All Resources

Search and Useful Links

Search the site, search suggestions.

We're here to help

To apply for admission as a first-year or transfer student at Harvard, you will start with the Application. Fill out the Common Application or the Coalition Application, Powered by Scoir (choose one, we have no preference), followed by the supplement to help us get a better sense of who you are. Not sure where to start? We've gathered some helpful tips on how to fill out the main application and the Harvard supplement.

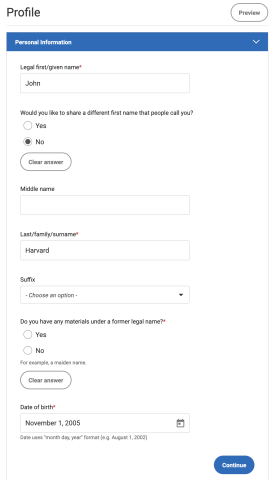

The Profile section is a place where you'll share detailed information about yourself, including contact information, demographics, and fee waiver request. It's always a good idea to review the information here and update any details, if necessary. Please note that none of the demographic questions in this section are required.

Profile Section

Personal information: legal name.

Please fill out your name exactly as it will show up on all materials we receive for your application. Your teachers, college counselors and others should also use your legal name just as it will appear on your financial aid forms, official test score reports, etc. Use of a nickname can cause your application to be incomplete if we cannot match your materials to your application.

Citizenship

Citizenship does not in any way affect your chances of admission or eligibility for financial aid at Harvard. There is no admissions advantage or disadvantage in being a US citizen. This is not the case at all institutions.

For students who need a visa to study in the United States, this question is of critical importance: we begin to prepare the forms that qualify you for a visa immediately after acceptance. Any delay in this process can jeopardize your chances of arriving in Cambridge in time to begin the fall semester.

U.S. Social Security Number

Your U.S. Social Security number is kept strictly confidential and is used solely to match up your admissions and financial aid data if you are applying for aid.

U.S. Armed Forces Status

The applications of veterans are most welcome and your service is a positive factor in our admissions process. We’re proud to help veterans continue their education by participating in the Yellow Ribbon Program and Service to School’s VetLink program. Learn more about applying as a veteran here .

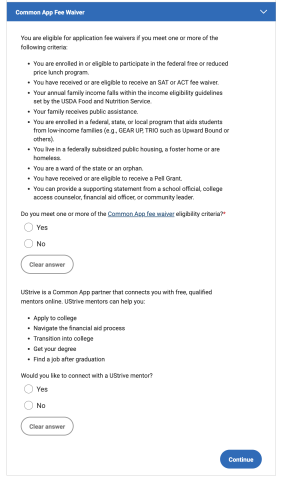

Application Fee Waiver

The application fee covers a very small portion of the administrative costs of processing applications. However, if the fee presents a hardship for you or your family, it will be waived. Each applicant applying with a fee waiver should select an option for a need-based fee waiver. Do not let the application fee stand in the way of applying!

How to Request an Application Fee Waiver

Do not let the admissions application fee prevent you from applying! In the spirit of our honor code , if the admissions application fee presents a hardship for you or your family, the fee will be waived. Please follow the steps below to request a fee waiver:

Common Application

- Confirm that you meet at least one of the indicators of economic need and then select “Yes” to the prompt “You are eligible for application fee waivers if you meet one or more of the following criteria."

- Complete the fee waiver signature.

Coalition Application

- Confirm that you meet at least one of the indicators of economic need listed in the Fee Waiver section of your Profile.

- If you do not meet one of the indicators of economic need, you may enter the Harvard-specific fee waiver code on the payment page: JH3S5Q2LX9

Transfer Applicants

- Please send an email to [email protected] to request a transfer application fee waiver.

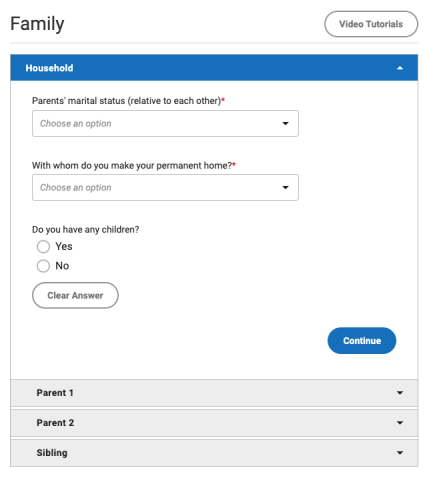

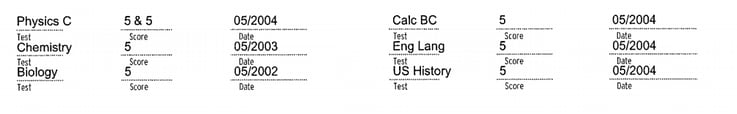

In the family section, you'll share information about your household, your parents, and any siblings. Most colleges collect this information for demographic purposes. Even if you're an adult or an emancipated minor, you'll need to fill out this section.

Unknown Parent

Answer the questions as honestly and fully as you can, but don’t worry if you and your parent/guardian do not know all of the details about your family.

Family Information

Part of an admissions officer’s job in reading your application is to understand your background and how these circumstances have affected your upbringing, the opportunities available to you, academic preparation, and other factors relevant to the college admissions process.

Family life is an important factor in helping us to learn more about the circumstances and conditions in which you were raised, and how you have made the most of the opportunities provided by your family. We want to understand where you’re coming from, not only in school, but at home as well.

Parent Education

Parents almost always have a significant effect on students’ lives. Information about parents may indicate challenges you have faced – and overcome. In your essay you might elaborate on your family experiences in a wide variety of ways that can illuminate your character and personal qualities, including the positive aspects of your family life.

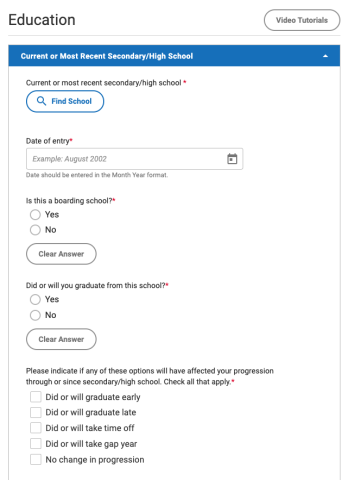

In the Education section is where you will share information about your current school or coursework, academic honors, and future education plans. Here are some tips on commonly asked questions.

Interruption in Education

It is not uncommon for students to change schools or take time off during high school. While this information will most likely appear on your transcript, hearing directly from you about any interruption in schooling will help us to fill in any gaps.

We always defer to the secondary school report for information about grades. If yours is not provided by the counselor or school, we will take into consideration what is self-reported, making sure to confirm with your school officials.

Current or Most Recent Year Courses

Please list the courses you are currently taking and/or are planning on taking before you graduate. If your schedule changes after you have submitted your application, please keep us updated by submitting additional materials in the Applicant Portal.

Honors & Level(s) of Recognition

This is a place to highlight any achievements or awards you have received. If you receive any significant honors or awards after submitting the application, you may notify us by submitting additional materials in the Applicant Portal and we will include this information with your application materials.

Future Plans & Career Interest

You do not need to have a ten year plan, but getting a sense of what kinds of professions you have considered gives us insight into your current plans. Don’t fret about it: put a few ideas down and move on with your application.

Since there are some students who do have a developed career interest already established while they are in high school, this question provides an opportunity to indicate such a plan.

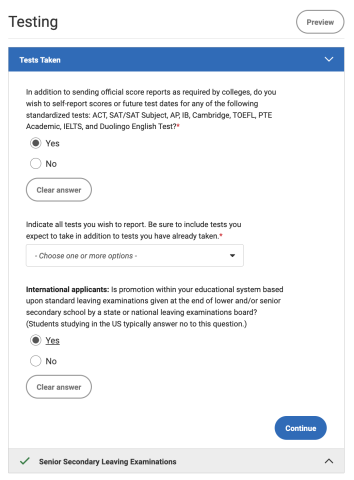

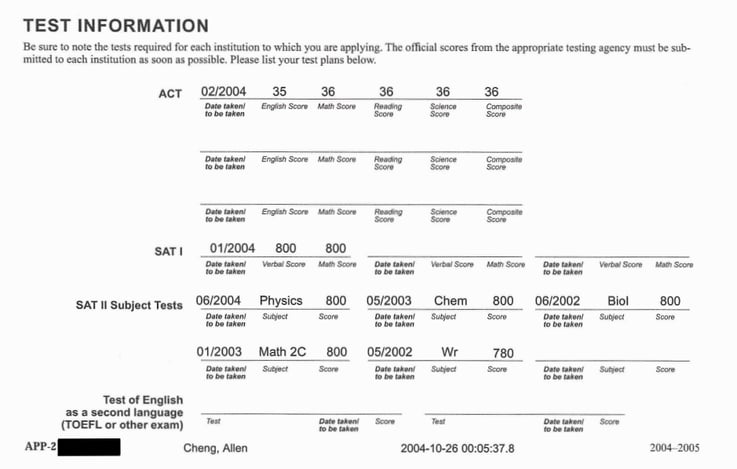

The Testing section is where you'll enter your self-reported scores for any standardized tests that you've taken and wish to report to colleges. However, remember that if you self-report your SAT or ACT test scores and you are admitted and choose to enroll at Harvard, you'll be required to submit your official score reports from the College Board or ACT. View more information on our standardized testing requirements on our Application Requirements page.

Tests Taken

Test scores.

We have always looked at the best scores applicants choose to submit. If you haven’t yet taken the tests, please indicate which tests you are taking and when.

The TOEFL is not required for Harvard, but if you are taking it for another college, you may elect to submit it as part of your Harvard application. Your score can be one more piece of evidence regarding your English language proficiency, so you may choose to submit it if you feel it provides additional helpful information.

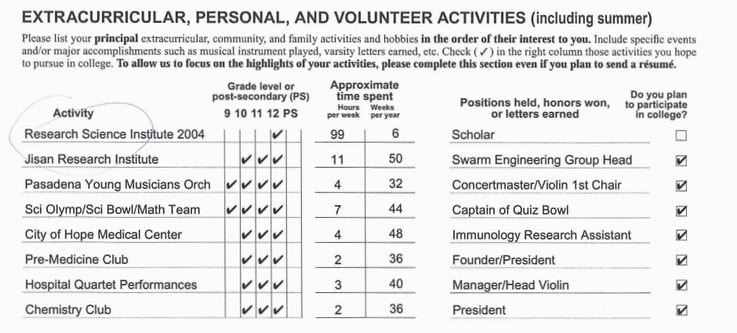

AP/IB Tests

These exam scores are additional pieces of academic information which can help us as we think about your preparation and potential for college level work. Sometimes AP or IB scores can demonstrate a wide range of academic accomplishments.

If you have the opportunity to take AP and IB exams, the results may also be helpful for academic placement, should you be accepted and choose to enroll at Harvard.

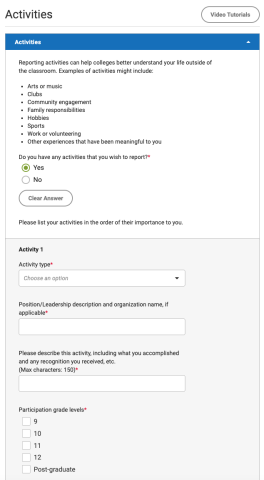

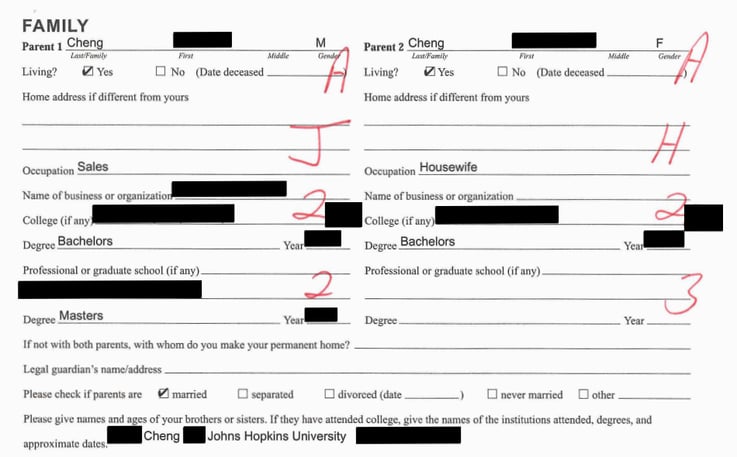

The activities section gives you the opportunity to tell schools more about who you are and activities you're involved with outside the classroom. You'll have the opportunity to list up to ten activities, but that doesn't mean you need to enter all ten.

How we use extracurricular activities and work experience in the admissions process

We are much more interested in the quality of students’ activities than their quantity so do not feel you need to fill in the entire grid! Contributions students make to the well-being of their secondary schools, communities and families are of great interest to us. So indicate for us the time you spend and the nature of the contribution to extracurricular activities, the local community, work experiences and help provided to your family. Activities you undertake need not be exotic but rather might show a commitment to excellence regardless of the activity. Such a commitment can apply to any activity in your life and may reflect underlying character and personal qualities.

For example, a student can gain a great deal from helping his or her family with babysitting or other household responsibilities or working in a restaurant to help with family or personal expenses. Such experiences are important “extracurricular” activities and can be detailed in the extracurricular section and discussed in essays.

Some students list only activities they feel will appear significant to the admissions office, while others endeavor to list every single thing they have ever done. Neither approach is right for everyone. Rather, you should think about the activities (in-school, at home, or elsewhere) that you care most about and devote most of your time doing, and list those.

We realize that extracurricular and athletic opportunities are either unavailable or limited at many high schools. We also know that limited economic resources in many families can affect a student’s chances for participation on the school teams, travel teams, or even prevent participation at all due to the costs of the equipment or the logistical requirements of some sports and activities. You should not feel that your chances for admission to college are hindered by the lack of extracurricular opportunities. Rather, our admissions committee will look at the various kinds of opportunities you have had in your lifetime and try to assess how well you have taken advantage of those opportunities.

For additional thoughts on extracurricular activities, please refer to this 2009 article in the New York Times: Guidance Office: Answers From Harvard’s Dean, Part 3 .

Positions held, honors won, letters earned, or employer

In this section, please describe the activity and your level of participation. Please note that your description should be concise, or it may be cut off by the Common Application.

Participation Grade Level

The grades during which you have participated are important because they help us to understand the depth of your involvement in that activity and your changing interests over time. Not all extracurricular activities must be a four-year commitment for our applicants.

Approximate Time Spent

We are interested to know how you manage your time and to understand how you balance your life outside of the classroom. Some students dedicate their time to one or two activities, while others spread their time among many.

When did you participate

We know that students are often active both during the school year and the summer – working, babysitting siblings, enrolling in courses, traveling, playing sports, holding internships, etc. Distinguishing school-year activities from summer activities helps us understand how you have spent your time and taken advantage of opportunities available to you.

Plans to participate in college?

Harvard is a residential institution, and our students are actively engaged in college life. This section helps us to understand how you might contribute at Harvard. Some students who were involved in several activities during high school choose to narrow their focus in college and/or to try new activities not previously available.

What if there's not enough space?

Filling out the grid is an act of prioritization: your responses tell us what activities or work experiences are most meaningful to you. And there’s quite a bit of space there, too; almost everyone should be able to convey the breadth and depth of out-of-class commitments on the application. Conversely, please do not feel a need to fill every line!

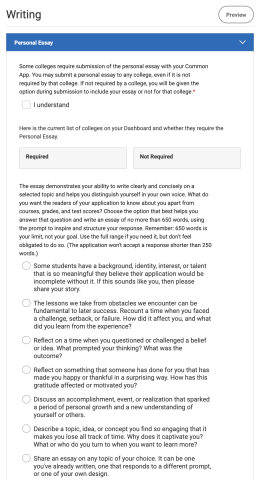

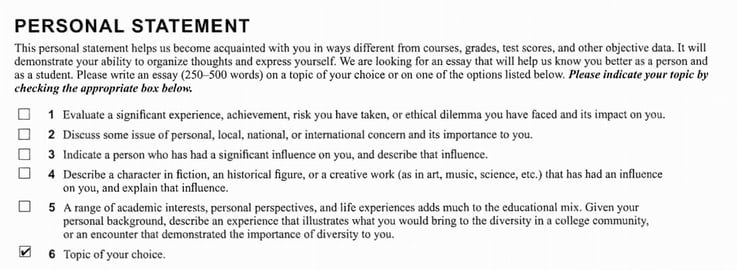

The first section is the personal essay. Harvard requires the submission of the personal essay with your application. We also offer an opportunity to add any additional information.

Personal Essay

The Common Application essay topics are broad. Please note that Coalition essay questions may differ. While this might seem daunting at first, look at it as an opportunity to write about something you care about, rather than what you think the Admissions Committee wants to hear. The point of the personal statement is for you to have the chance to share whatever you would like with us. Remember, your topic does not have to be exotic to be compelling.

Essay topics include:

- Some students have a background, identity, interest, or talent that is so meaningful they believe their application would be incomplete without it. If this sounds like you, then please share your story.

- The lessons we take from obstacles we encounter can be fundamental to later success. Recount a time when you faced a challenge, setback, or failure. How did it affect you, and what did you learn from the experience?

- Reflect on a time when you questioned or challenged a belief or idea. What prompted your thinking? What was the outcome?

- Reflect on something that someone has done for you that has made you happy or thankful in a surprising way. How has this gratitude affected or motivated you?

- Discuss an accomplishment, event, or realization that sparked a period of personal growth and a new understanding of yourself or others.

- Describe a topic, idea, or concept you find so engaging that it makes you lose all track of time. Why does it captivate you? What or who do you turn to when you want to learn more?

- Share an essay on any topic of your choice. It can be one you've already written, one that responds to a different prompt, or one of your own design.

Additional Information

Do not feel obligated to fill this space, but some students have used this opportunity to tell us about challenging circumstances in their lives such as illness or other difficulties that may have affected their grades. Any information that can tell us more about the person behind the test scores and grades can be helpful.

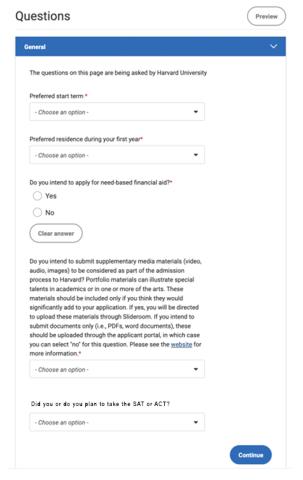

Harvard Questions

Each college or university that is a member of the Common Application and/or the Coalition Application - Powered by Scoir has an opportunity to ask applicants a series of school-specific questions separate from the common part of the application. The Harvard supplement contains a series of questions that help us learn more about your academic, extracurricular, and personal interests. You application is not considered complete until you submit the supplement.

General: Applying for Financial Aid

Harvard has a need-blind admissions process and applying for aid is never detrimental to your admissions decision. We ask this question because we want to be able to calculate your financial need in advance of our April notification date so that we can send your admission letter and financial aid offer at the same time. One thing to note – not all institutions have such policies.

General: Submitting Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials (art slides, music recordings, research papers, etc.) help when they reveal unusual talent. You absolutely do not have to include anything supplementary to gain acceptance to Harvard, and the vast majority of admitted students do not submit supplementary materials with their applications. You can submit art and media files through Slideroom and any documents or articles directly in the Applicant Portal with an uploader tool.

Academics: Fields of Study

When you select from the full list of Harvard's academic concentrations, you give us a sense of the direction you may choose when it comes time for you to choose a concentration at Harvard in your sophomore year.

While we realize that this question is quite similar to the one asked on the Common Application, our own format allows us to fit this information into data fields that Harvard has been collecting for many years. While we know students might well change their minds once they are in college, it is helpful for us to get a sense of their current interests and those academic areas in which they have already spent time and effort.

We do not admit students into specific academic programs, and we have no quotas or targets for academic fields.

Academics: Future Plans

As a liberal arts institution with fifty academic concentrations and more than 450 extracurricular organizations, we expect and encourage our students to explore new opportunities. We understand that as you answer these questions, you may not be entirely sure of your plans, but this information helps us to understand how you might use Harvard.

One of the principal ways students meet and educate each other during college is through extracurricular activities. Your answer to this question gives us a better sense of the interests you might bring to college and how definite your academic, vocational, extracurricular or athletic interests might be. This information helps us understand better how you might use Harvard. Of course, one of the best things about a liberal arts education is that plans may change. There is no “right” answer to these questions.

If you have applied to Harvard before, we want to include your previous application with your current one. We also want to have a record of any other involvement at Harvard you may have had, including the Summer School and the Extension School and associated transcripts. This information adds to the context of your present application. It can be helpful for us to note changes in your application—perhaps areas where you have strengthened the academic and/or extracurricular aspects of your candidacy.

Writing Supplement

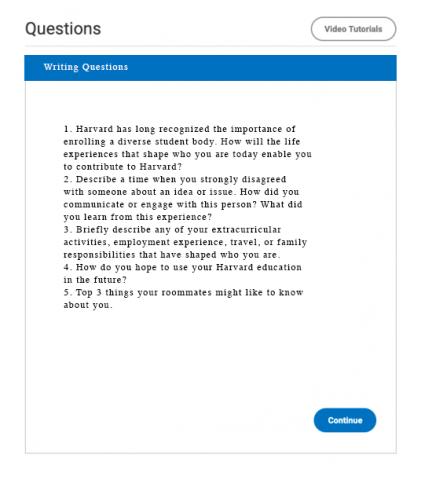

The supplement includes five required short-answer questions, each with a 150 word limit. We want to ensure that every student has the same opportunity to reflect on and share how their life experiences and academic and extracurricular activities shaped them, how they will engage with others at Harvard, and their aspirations for the future. Our continued focus is on considering the whole student in the admissions process and how they have interacted with the world.

Required Short Answer Questions

Each question has a 150 word limit.

- Harvard has long recognized the importance of enrolling a diverse student body. How will the life experiences that shape who you are today enable you to contribute to Harvard?

- Describe a time when you strongly disagreed with someone about an idea or issue. How did you communicate or engage with this person? What did you learn from this experience?

- Briefly describe any of your extracurricular activities, employment experience, travel, or family responsibilities that have shaped who you are.

- How do you hope to use your Harvard education in the future?

- Top 3 things your roommates might like to know about you.

Related Guides

Here you'll find information on tracking your application and interviews.

Financial Aid Fact Sheet

Get the facts about Harvard College's revolutionary financial aid program.

Guide to Preparing for College

Find information about selecting high school courses that best prepare you for liberal arts colleges with high academic demographic such as Harvard.

Sign up to our Newsletter

Harvard law personal statement: how to write + example.

Reviewed by:

David Merson

Former Head of Pre-Law Office, Northeastern University, & Admissions Officer, Brown University

Reviewed: 03/03/23

If you’re applying to Harvard Law School, it’s essential to write an impactful personal statement. Read on to learn how to write a Harvard law personal statement that sets you apart from the crowd.

The Harvard Law personal statement is an important part of the application process. It provides an opportunity for you to showcase your unique qualities and experiences to the admissions committee. You can communicate your motivations, passions, and goals for pursuing a legal education at Harvard Law School through the personal statement.

To have a good chance of getting into Harvard Law , you need to stand out from the thousands of other applicants. By presenting a compelling personal statement, you can make a positive impression on the admissions committee and increase your chances of admission.

Keep reading to learn how to write a personal statement that distinguishes you from other applicants and demonstrates your fit with Harvard Law School's values and culture.

This guide will cover the requirements and tips you need to know to write a well-crafted Harvard Law personal statement. We’ll also go over a successful Harvard Law personal statement example and why it works!

Harvard Law School Personal Statement Requirements

To write a successful personal statement that demonstrates your value as an applicant, you need to ensure you stick to the requirements. The admissions committee is looking for applicants who show they care about the application process and pay attention to detail.

Not adhering to the requirements could suggest a lack of attention to detail and negatively impact your chances of being admitted. Following the requirements ensures that your personal statement is well-organized and focused so that you can effectively communicate your message to the admissions committee.

Here are the requirements for the Harvard law personal statement:

Length: Your personal statement must be no more than two pages in length, double-spaced, with a font size no smaller than 11-point, and one-inch margins.

Content: It should provide insight into who you are as a person and as a potential law student. Use this space to tell a story that illustrates your strengths, passions, and goals. You can also discuss any challenges you’ve overcome or experiences that have shaped your unique perspective.

Format: Your personal statement should be saved as a PDF and uploaded to the application portal . Your name and LSAC account number should be included on each page of the personal statement.

Additional Information: In addition to the personal statement, you may also choose to submit a supplementary statement about any factors that may have affected your academic performance or a diversity statement that describes your unique perspective and experiences.

Paying attention to these requirements is key, as failing to do so can result in an incomplete or disqualified application. Adhering to the guidelines and word count ensures that your personal statement is concise and tailored to the expectations of the admissions committee.

It's also important to note that while the personal statement is a crucial component of your application, it's not the only factor that Harvard Law School considers. Your academic record, test scores, letters of recommendation, and other factors will also be evaluated.

Crafting a Winning Personal Statement for Harvard Law School

Harvard Law is one of the most prestigious law schools in the world. So, it’s important to make sure every element of your application is top-notch. A well-written personal statement can make you a memorable candidate and increase your chances of getting in.

To put your best foot forward, book a free consultation with Juris Education advisors . By learning what’s worked for other applicants, you can write a personal statement you can be proud of. Let’s get started.

Start by Brainstorming

Before you begin writing your personal statement, take some time to brainstorm your ideas. Consider your experiences, accomplishments, and goals, and think about how they relate to your desire to attend Harvard Law School.

Brainstorming helps generate ideas, clarify thoughts, and identify key themes or concepts. It’s a process of free-flowing, non-judgmental thinking that allows for creative exploration and problem-solving. It can help you organize and prioritize ideas and content.

By brainstorming, you can uncover unique and compelling aspects of your experiences or qualifications that might have gone unnoticed. It also provides a foundation for the writing process and can help to streamline and focus your message. Overall, brainstorming can bring a lot of value to a Harvard Law personal statement.

Develop a Thesis Statement

Once you have a sense of the main ideas you want to convey in your personal statement, develop a thesis statement that encapsulates your main message. This should be a single sentence that highlights the central theme of your personal statement.

A strong thesis statement is essential for your personal statement because it serves as the central message or argument that you’re trying to convey in your writing. It should be concise and clear, and highlight the main theme you want to communicate to the admissions committee.

A thesis statement helps to focus your personal statement and gives it a clear sense of direction. It also helps to ensure that your writing is coherent and organized, which is important for making a strong impression on the admissions committee.

In addition, your thesis statement can help you to stand out from other applicants. It allows you to demonstrate your unique perspective and approach to the law and helps to highlight what makes you a strong candidate for Harvard Law School.

Overall, having a well-thought-out thesis statement provides a sense of direction throughout your personal statement, helps to make your writing more focused and organized, and allows you to communicate your unique perspective and strengths as a law school candidate.

Tell a Story

Rather than simply listing your accomplishments, use your personal statement to tell a story that illustrates your strengths, passions, and goals. Use specific examples and anecdotes to bring your story to life.

Storytelling can have a powerful impact on a personal statement for Harvard Law School. By telling your story, you can help the admissions committee get a better sense of who you are as a person and as a potential law student.

When done effectively, storytelling can help your personal statement stand out from the thousands of other applications that the admissions committee receives each year. It can make it more memorable, engaging, and can help create an emotional connection with the reader.

Storytelling can also help demonstrate skills and qualities that law schools are looking for, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and effective communication. Using examples from your experiences to illustrate these skills, you can show the admissions committee why you would be a valuable addition to their community.

Storytelling can be a powerful tool in a personal statement for Harvard Law School. By using concrete examples and narratives to illustrate your strengths and goals, you can create a compelling case for why you would be a strong candidate for admission.

Show, Don't Tell

Instead of simply stating that you're a hard worker or a great leader, demonstrate these qualities through specific examples and anecdotes. Use descriptive language and imagery to paint a picture of who you are and what you've accomplished.

Showing qualities through the lens of your experiences makes your writing more engaging and memorable. Using specific examples to illustrate your qualities and achievements will ultimately make your Harvard Law personal statement more impactful.

Keep It Brief and On Point.

Remember that your personal statement should be no more than two pages long, so stick to your point. Remember that the admissions committee receives thousands of applications each year, and they typically have a limited amount of time to review each one.

Ensure that your personal statement is clear and easy to read by using simple language and staying focused on your main thesis. You want to write just enough to make a strong case for why you are a strong candidate for admission to Harvard Law School.

By focusing on your most important experiences and qualities and avoiding unnecessary tangents, you can demonstrate your value as a potential law school student and make a compelling argument for why you should be admitted.

Edit and Revise

Once you've written a draft of your personal statement, take some time to edit and revise it. Pay attention to grammar, punctuation, and spelling, and make sure your writing is clear and concise. Ask someone else to read your personal statement and provide feedback.

A well-written and error-free personal statement can make a positive impression on the admissions committee, while a poorly edited statement can detract from your qualifications.

Editing allows you to refine your message, eliminate errors and inconsistencies, and ensure your personal statement is crystal clear. Careful editing helps to demonstrate attention to detail and professionalism, qualities that are highly valued in the legal profession.

Pay Attention to Formatting

Finally, be sure to follow the formatting requirements for the Harvard Law School personal statement. Save your personal statement as a PDF and include your name and LSAC account number on each page.

A well-formatted statement is not only aesthetically pleasing but also shows that you took it seriously. It can make the statement more readable and easier to navigate for the admissions committee. A well-organized statement can also help to structure your thoughts and ensure that you’re effectively conveying your message.

By following these steps and putting in the time and effort to write a strong personal statement, you can increase your chances of being admitted to one of the most prestigious law schools in the world.

What to Avoid in a Harvard Law Personal Statement

When writing a personal statement for Harvard Law School, it's important to know what to avoid. Read on to learn everything you need to know.

Avoid using clichéd phrases or overused quotes in your personal statement. The admissions committee reads a ton of personal statements every year, so it's important to try to make a unique impression.

Clichés can often be vague and lack specificity, which can make it difficult for the committee to understand your message and qualifications. By avoiding cliches, you can demonstrate your individual perspective and voice. Remember, there’s only one you .

Rambling or Tangential Writing

Your personal statement should be focused and concise, with a clear thesis statement and supporting examples.

Rambling or going off-topic can detract from the overall impact of your personal statement. It can suggest a lack of organizational skills and attention to detail, qualities highly valued in the legal profession.

To avoid rambling when writing, it is important to stay focused on the topic at hand and stick to a clear structure. Start by outlining the main points that you want to make and the supporting evidence or examples that you’ll use to illustrate those points. Use concise language and avoid unnecessary tangents or repetition.

It’s also helpful to read through your writing regularly and ask yourself if each sentence and paragraph is contributing to the overall message you are trying to convey. Finally, consider having someone else review your work to provide feedback and help identify any areas where you may be straying off topic.

While it's essential to showcase your strengths and accomplishments, avoid coming across as cocky or entitled in your personal statement. Instead, focus on demonstrating your passion for law and your commitment to making a positive impact in the legal field.

Admissions committees are looking for candidates who are not only academically qualified but who also possess the emotional intelligence and interpersonal skills necessary for success in the legal profession.

By being humble, you show your capacity for growth, willingness to learn from others, and commitment to serving the greater good.

Avoid focusing on experiences that paint you in a negative light. Instead, pay attention to the positive lessons you've learned and how you've grown and developed as a person and as a potential law student.

Being negative may raise concerns about your ability to work collaboratively with others. Highlighting negative events or attitudes can take away from the overall message of your personal statement, which is an opportunity for you to promote your talents, experiences, and qualifications.

The legal profession requires the ability to work effectively with others and to maintain a positive and professional demeanor even in challenging situations. By maintaining a positive tone, you can demonstrate your resilience, adaptability, and ability to work effectively in a team-oriented environment.

It should go without saying, but be sure to avoid any form of plagiarism in your personal statement. This includes copying and pasting from other sources, using quotes without attribution, or hiring someone to write your personal statement for you.

Presenting someone else's work or ideas as your own is a form of academic dishonesty. Your personal statement is meant to express your unique background, experiences, and qualifications, and plagiarism undermines its authenticity.

Additionally, plagiarism is a violation of Harvard Law School's code of conduct and can result in serious consequences, including rejection of your application or even revocation of an already awarded admission.

By submitting an original and authentic personal statement, you can demonstrate your honesty, integrity, and professionalism, qualities that are highly valued in the legal profession.

By avoiding these pitfalls and focusing on crafting a unique personal statement, you can increase your chances of being admitted to Harvard Law School. Remember, the personal statement is an important opportunity to show who you truly are and why you're a strong candidate, so take the time to do it right.

Harvard Law Personal Statement Example

It can help to read a Harvard law personal statement example to get a good understanding of what the admissions committee is looking for. Reading through successful examples can provide insight into what constitutes a strong Harvard law personal statement.

The following personal statement , written by Dasha Wise, is an example of a successful Harvard Law School application essay.

"The large room was beginning to feel like a cramped interrogation chamber as we stood anxiously awaiting the next set of difficult questions. We did not have to wait long. Why were there discrepancies in our numbers? Wasn’t the retreat expense unnecessarily large? Not to mention that the submitted documents were not only late but incomplete!

I could not help but steal a glance at the out-going treasurer standing next to me—as a newly elected executive board treasurer for Community Impact (CI), Columbia’s largest service organization, I had been invited to accompany her to CI’s annual presentation to request funding from the student councils.

There was no doubt that she had stayed up most of the night completing this presentation, attempting to patch up holes in the financial records.

I could not blame her for the mistakes—everyone at CI was overworked and stretched well beyond their capacity, too busy keeping up with the activities of each day to step back and tackle the organization’s underlying problems.

As she became visibly more flustered, I knew that I needed to assume responsibility for the remainder of the presentation. Standing there in defense of the organization that I had come to love, I managed to remain calm, elding critical questions to the best of my ability while swallowing the all-too-well-founded criticism along with my pride.

As the presentation came to a close, I began to understand the systematic change that was necessary and that I would be responsible for making this change a reality.

I began immediately that summer.

Learning as much as possible about the current system and its laws enabled me to discover that CI’s largest impediments were operational inefficiency and improper communication, the combination of which was contributing to internal frustration, ineffective resource management, and a tainted reputation.

To establish both scale accuracy and efficiency, I reconstructed treasury procedures and devised an automated budget-tracking and request-processing mechanism that would be administered through CI’s online platform.

Working closely with our webmaster, I designed a treasury section for CI’s website that would enable coordinators to request funding, monitor their budgets, and access key forms as well as the instructional manuals that I had written over the summer.

To reposition CI’s public image, I insisted on transparency, persuading the staff of its importance and holding a board meeting to update important documents such as our constitution and spending guidelines. Reacting CI’s core principles and procedures, they would now be publicly displayed on our website.

In pushing for large-scale change, I knew in advance that over-seeing the process would be no easy task and that I would need to hold numerous trainings, respond immediately to student inquiries, and continue to work throughout the year to make further corrections based on feedback and my own observations.

All this I was prepared for, and with input from my peers and CI’s staff along the way, I arrived at a product that would provide the CI treasury with structural support for years to come.

CI’s records were accurate, and we were able to cut costs, monitor our spending, and receive approval from our volunteers, for whom the elusive red tape had now given way to simplicity and predictability.

A system that responded to the needs of students, board members, and staff alike eliminated needless frustration, established procedural efficiency, and improved both internal and external communication.

When I found myself in front of the student councils exactly one year later, I was not met with the same mistrust and quizzical expressions.

Our presentation, whose supporting documents had this time been submitted well in advance and verified multiple times, resulted in open gratitude for the effort that we had put in to establish scale accuracy and procedural transparency and to maintain open communication with the councils, informing them of the changes that we were making in light of their concerns.

Unlike the previous year’s penalty and subsequent funding shortage, this time we received precisely what we requested. Yet perhaps most importantly, we received respect, not only from our own coordinators, volunteers, and other constituents but from the university as a whole.

Although I had encountered numerous difficulties throughout my life, what I had decided to tackle at CI last year was my most significant challenge yet—not merely for the amount of effort that it required, but for the fact that my decisions now affected whether directly or indirectly, hundreds of others, from CI’s staff and student executives to our nine hundred volunteers and the nine thousand individuals that they served.

In some quantifiable sense, this was my biggest accomplishment, the most rewarding, and among the most memorable, but it was not the first and it will not be the last. I would not have it any other way.

To survive difficulties is one thing, but to excel in spite of them is another. Overcoming the most seemingly insurmountable yet worthy challenges is, for me, the primary means of obtaining respect from the one person that truly matters and is, at the same time, the most difficult to please— myself.

Why this essay works: This Harvard law personal statement example checks every box. It’s personal, concise, impactful, and clearly communicates the qualities that would make Dasha an excellent lawyer. If it helps to get the creative juices flowing, reading sample personal statements can be a great source of inspiration for your writing.

FAQs: Harvard Law School Personal Statement

The Harvard Law personal statement is an important part of your law school application and needs to be carefully thought out. It makes sense to have questions, so keep reading to learn more about the Harvard law personal statement.

1. How Long Should My Personal Statement Be for Harvard Law?

The length of your personal statement for Harvard Law School should be no more than two pages, double-spaced. Harvard recommends that applicants aim for a length of 750 to 1,500 words, which should provide enough space to effectively communicate your message while still remaining concise and focused.

2. How Important Is the Harvard Law School Personal Statement?

The Harvard law personal statement is a crucial component of the law school application and is given significant weight in the admissions decision-making process.

The personal statement allows applicants to showcase their unique experiences, qualifications, and motivations for pursuing a legal education and to demonstrate their fit with Harvard Law School's values and culture.

A well-written personal statement can make a positive impression on the admissions committee and increase an applicant's chances of being admitted to this highly selective law school.

3. What Should I Include in My Personal Statement for Harvard Law?

In your personal statement for Harvard Law, you should include information about your background, experiences, and achievements, as well as your motivations for pursuing a legal education. You should also highlight your skills and abilities relevant to the legal profession, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and communication skills.

Additionally, you may want to discuss any challenges or obstacles you’ve overcome and how these experiences have shaped your goals and aspirations. Finally, it is important to showcase your fit with Harvard Law School's values and culture and to explain why you are a strong candidate for admission.

Final Thoughts

Hopefully, you now have a good understanding of how to write a solid Harvard law personal statement. Remember to stay true to your voice and experiences, be authentic and sincere, and take the time to edit and revise your statement to ensure it’s polished and professional.

By following the tips and guidelines outlined in this blog and reviewing the Harvard Law personal statement example provided, you can craft a compelling personal statement that stands out to the admissions committee and increases your chances of being admitted to Harvard Law School.

Once you’ve written a strong personal statement, you can focus on the next steps, such as collecting letters of recommendation , prepping for a possible Harvard Law interview , or brushing up on legal terms . Good luck on your application journey!

Schedule A Free Consultation

You may also like.

Highest-Paid Lawyers: Most Profitable Law Careers

Law Schools in Colorado: Your Guide

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

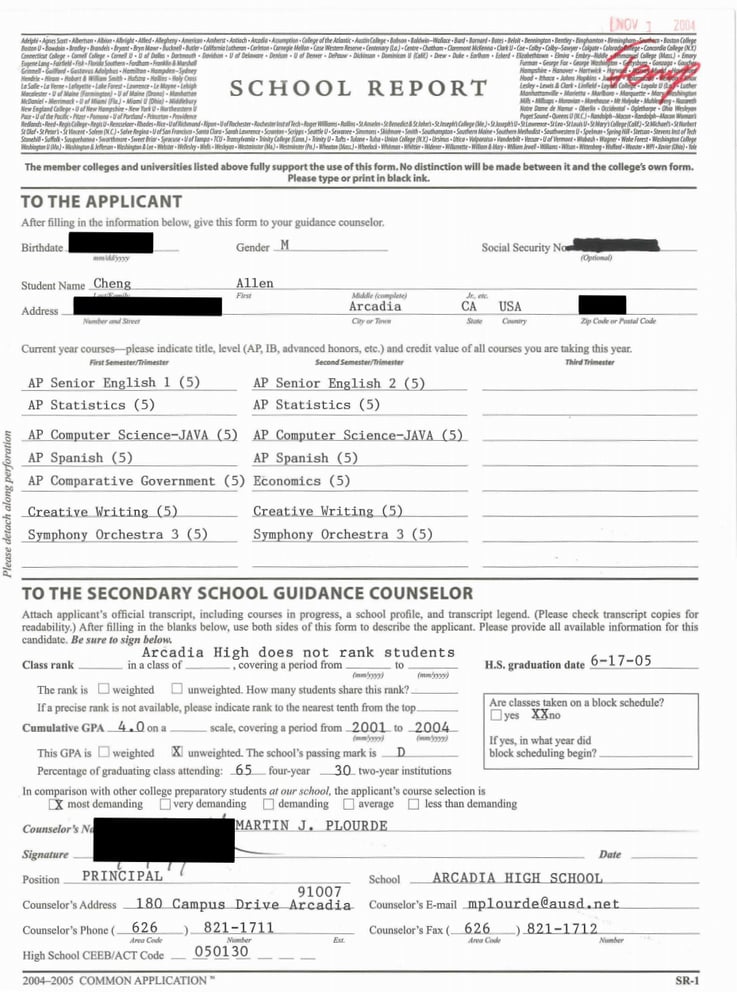

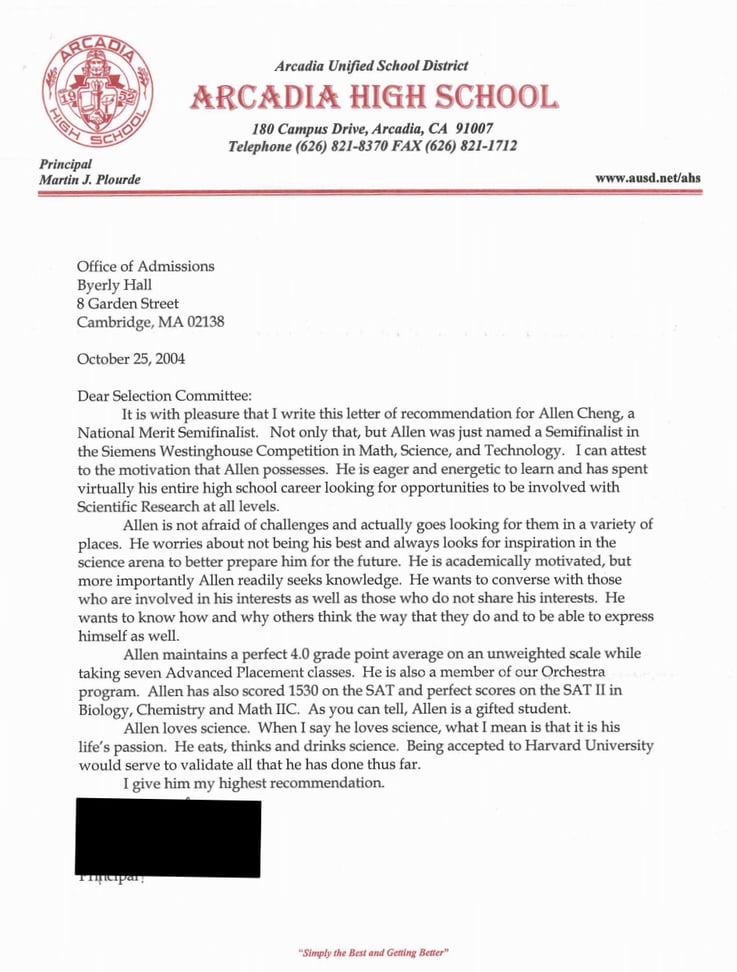

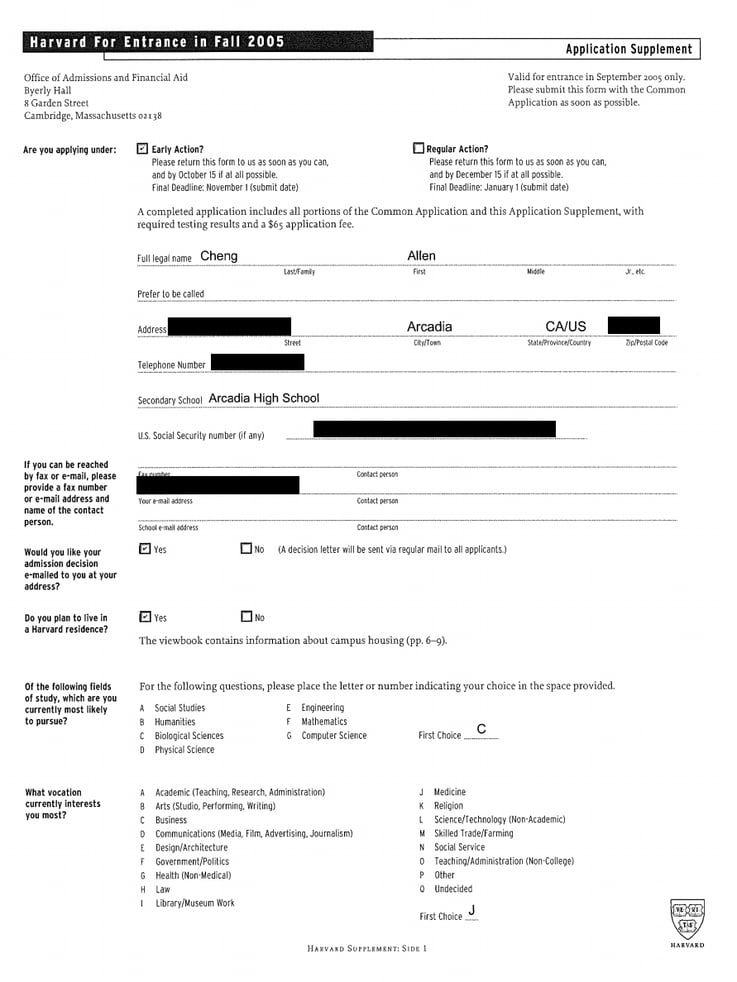

My Successful Harvard Application (Complete Common App + Supplement)

Other High School , College Admissions , Letters of Recommendation , Extracurriculars , College Essays

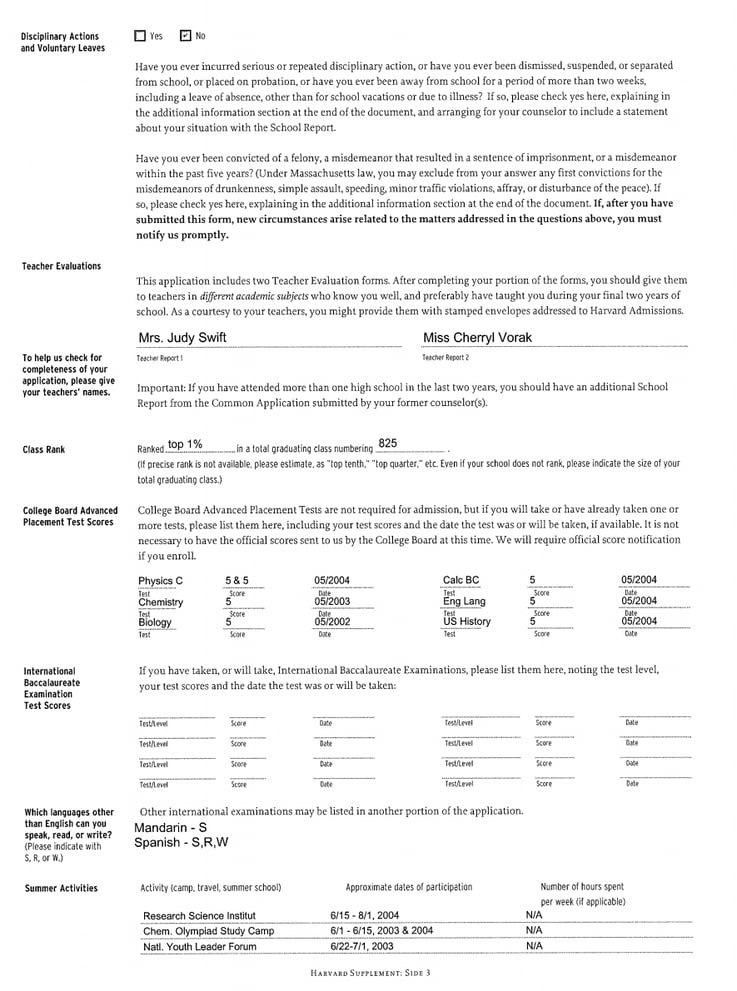

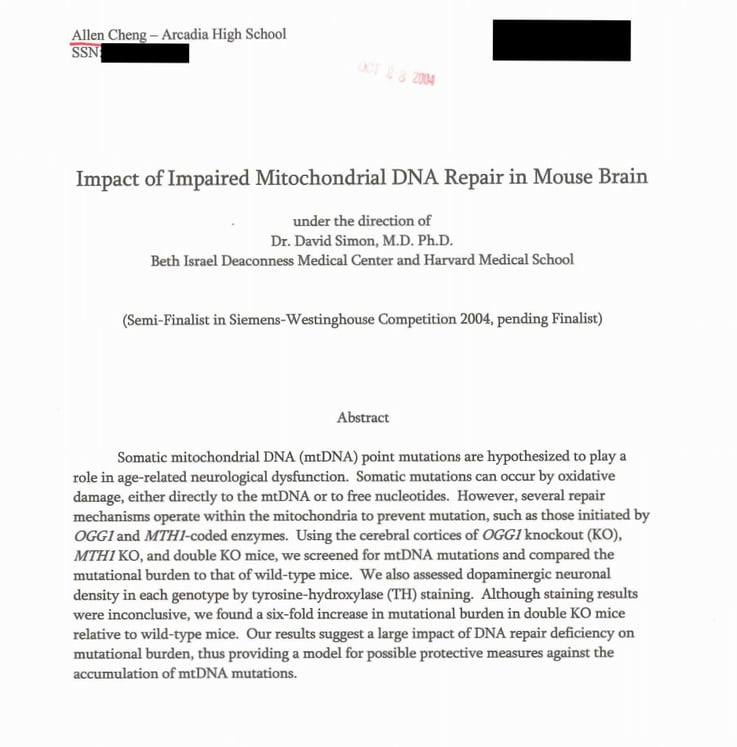

In 2005, I applied to college and got into every school I applied to, including Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, and MIT. I decided to attend Harvard.

In this guide, I'll show you the entire college application that got me into Harvard—page by page, word for word .

In my complete analysis, I'll take you through my Common Application, Harvard supplemental application, personal statements and essays, extracurricular activities, teachers' letters of recommendation, counselor recommendation, complete high school transcript, and more. I'll also give you in-depth commentary on every part of my application.

To my knowledge, a college application analysis like this has never been done before . This is the application guide I wished I had when I was in high school.

If you're applying to top schools like the Ivy Leagues, you'll see firsthand what a successful application to Harvard and Princeton looks like. You'll learn the strategies I used to build a compelling application. You'll see what items were critical in getting me admitted, and what didn't end up helping much at all.

Reading this guide from beginning to end will be well worth your time—you might completely change your college application strategy as a result.

First Things First

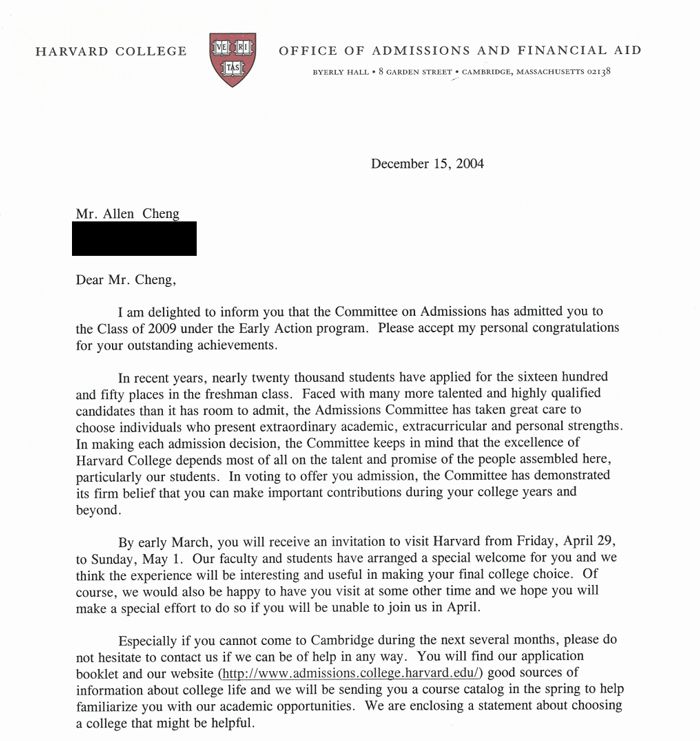

Here's the letter offering me admission into Harvard College under Early Action.

I was so thrilled when I got this letter. It validated many years of hard work, and I was excited to take my next step into college (...and work even harder).

I received similar successful letters from every college I applied to: Princeton, Stanford, and MIT. (After getting into Harvard early, I decided not to apply to Yale, Columbia, UChicago, UPenn, and other Ivy League-level schools, since I already knew I would rather go to Harvard.)

The application that got me admitted everywhere is the subject of this guide. You're going to see everything that the admissions officers saw.

If you're hoping to see an acceptance letter like this in your academic future, I highly recommend you read this entire article. I'll start first with an introduction to this guide and important disclaimers. Then I'll share the #1 question you need to be thinking about as you construct your application. Finally, we'll spend a lot of time going through every page of my college application, both the Common App and the Harvard Supplemental App.

Important Note: the foundational principles of my application are explored in detail in my How to Get Into Harvard guide . In this popular guide, I explain:

- what top schools like the Ivy League are looking for

- how to be truly distinctive among thousands of applicants

- why being well-rounded is the kiss of death

If you have the time and are committed to maximizing your college application success, I recommend you read through my Harvard guide first, then come back to this one.

You might also be interested in my other two major guides:

- How to Get a Perfect SAT Score / Perfect ACT Score

- How to Get a 4.0 GPA

What's in This Harvard Application Guide?

From my student records, I was able to retrieve the COMPLETE original application I submitted to Harvard. Page by page, word for word, you'll see everything exactly as I presented it : extracurricular activities, awards and honors, personal statements and essays, and more.

In addition to all this detail, there are two special parts of this college application breakdown that I haven't seen anywhere else :

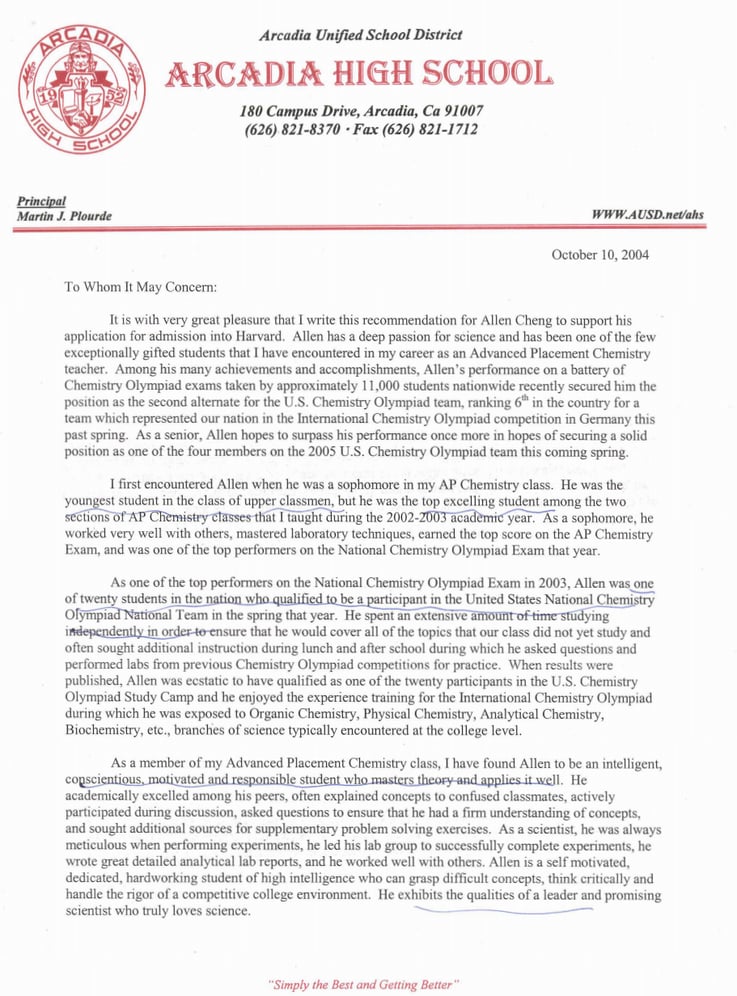

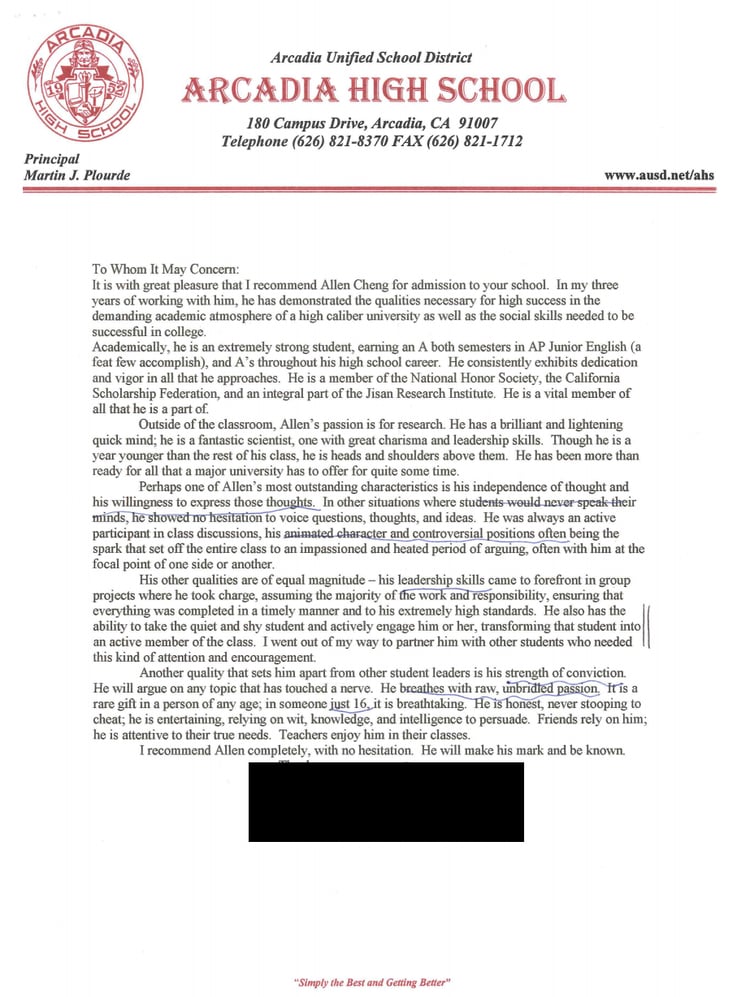

- You'll see my FULL recommendation letters and evaluation forms. This includes recommendations from two teachers, one principal, and supplementary writers. Normally you don't get to see these letters because you waive access to them when applying. You'll see how effective strong teacher advocates will be to your college application, and why it's so important to build strong relationships with your letter writers .

- You'll see the exact pen marks made by my Harvard admissions reader on my application . Members of admissions committees consider thousands of applications every year, which means they highlight the pieces of each application they find noteworthy. You'll see what the admissions officer considered important—and what she didn't.

For every piece of my application, I'll provide commentary on what made it so effective and my strategies behind creating it. You'll learn what it takes to build a compelling overall application.

Importantly, even though my application was strong, it wasn't perfect. I'll point out mistakes I made that I could have corrected to build an even stronger application.

Here's a complete table of contents for what we'll be covering. Each link goes directly to that section, although I'd recommend you read this from beginning to end on your first go.

Common Application

Personal Data

Educational data, test information.

- Activities: Extracurricular, Personal, Volunteer

- Short Answer

- Additional Information

Academic Honors

Personal statement, teacher and counselor recommendations.

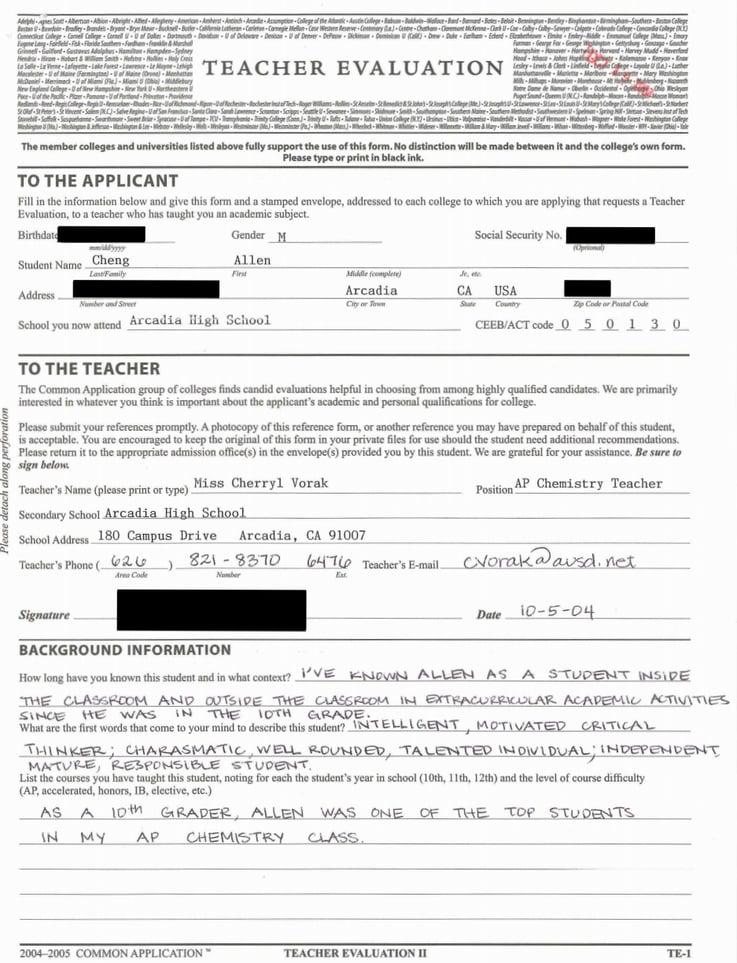

- Teacher Letter #1: AP Chemistry

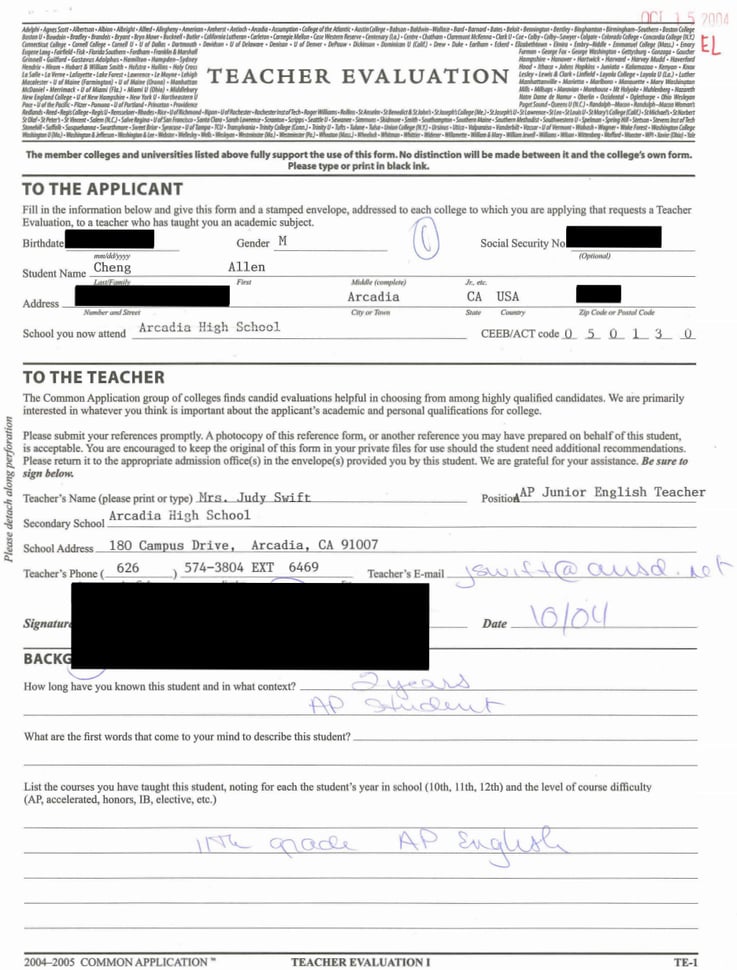

- Teacher Letter #2: AP English Lang

School Report

- Principal Recommendation

Harvard Application Supplement

- Supplement Form

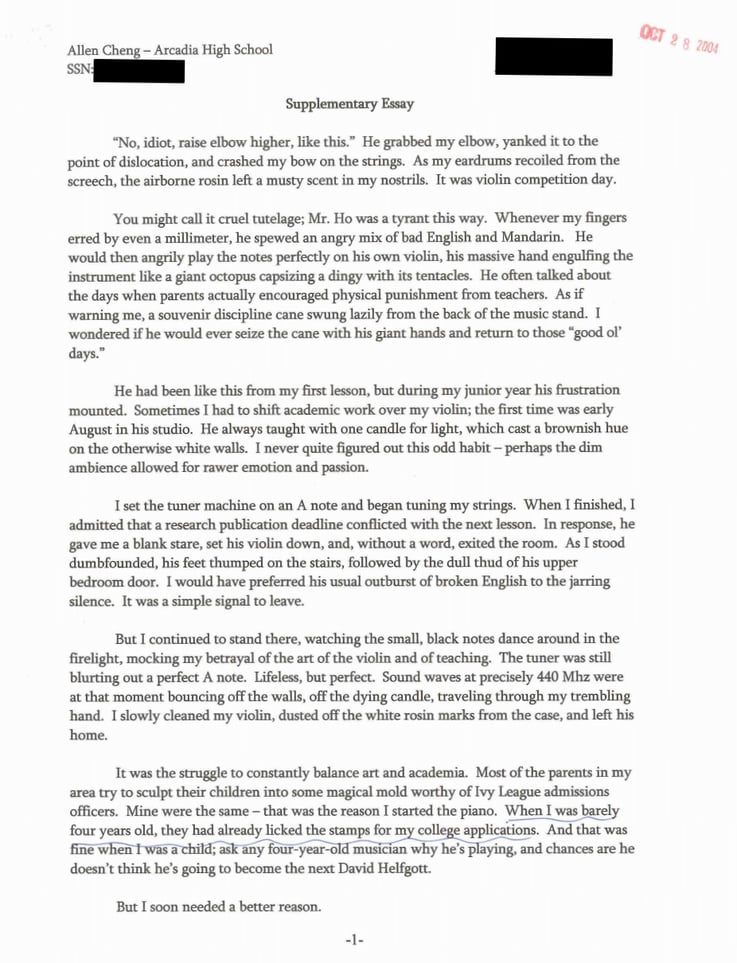

- Writing Supplement Essay

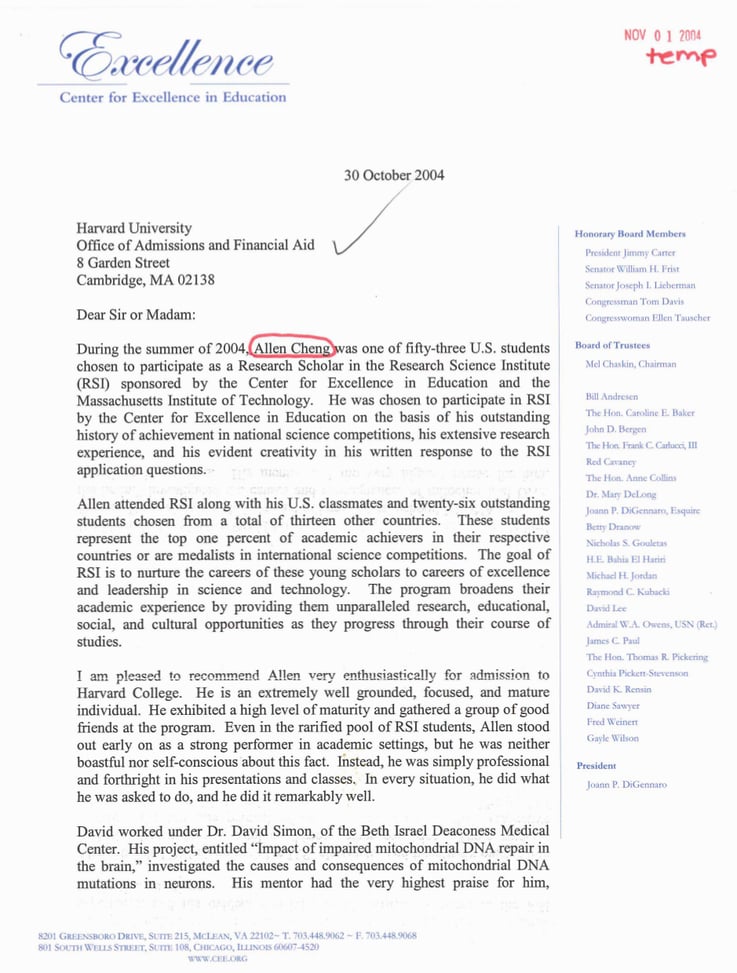

Supplementary Recommendation #1

Supplementary recommendation #2, supplemental application materials.

Final Advice for You

I mean it—you'll see literally everything in my application.

In revealing my teenage self, some parts of my application will be pretty embarrassing (you'll see why below). But my mission through my company PrepScholar is to give the world the most helpful resources possible, so I'm publishing it.

One last thing before we dive in—I'm going to anticipate some common concerns beforehand and talk through important disclaimers so that you'll get the most out of this guide.

Important Disclaimers

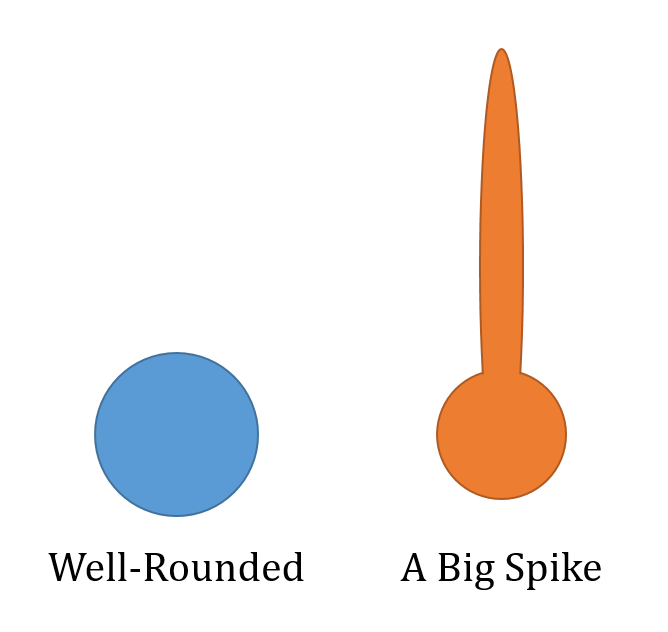

My biggest caveat for you when reading this guide: thousands of students get into Harvard and Ivy League schools every year. This guide tells a story about one person and presents one archetype of a strong applicant. As you'll see, I had a huge academic focus, especially in science ( this was my Spike ). I'm also irreverent and have a strong, direct personality.

What you see in this guide is NOT what YOU need to do to get into Harvard , especially if you don't match my interests and personality at all.

As I explain in my Harvard guide , I believe I fit into one archetype of a strong applicant—the "academic superstar" (humor me for a second, I know calling myself this sounds obnoxious). There are other distinct ways to impress, like:

- being world-class in a non-academic talent

- achieving something difficult and noteworthy—building a meaningful organization, writing a novel

- coming from tremendous adversity and performing remarkably well relative to expectations

Therefore, DON'T worry about copying my approach one-for-one . Don't worry if you're taking a different number of AP courses or have lower test scores or do different extracurriculars or write totally different personal statements. This is what schools like Stanford and Yale want to see—a diversity in the student population!

The point of this guide is to use my application as a vehicle to discuss what top colleges are looking for in strong applicants. Even though the specific details of what you'll do are different from what I did, the principles are the same. What makes a candidate truly stand out is the same, at a high level. What makes for a super strong recommendation letter is the same. The strategies on how to build a cohesive, compelling application are the same.

There's a final reason you shouldn't worry about replicating my work—the application game has probably changed quite a bit since 2005. Technology is much more pervasive, the social issues teens care about are different, the extracurricular activities that are truly noteworthy have probably gotten even more advanced. What I did might not be as impressive as it used to be. So focus on my general points, not the specifics, and think about how you can take what you learn here to achieve something even greater than I ever did.

With that major caveat aside, here are a string of smaller disclaimers.

I'm going to present my application factually and be 100% straightforward about what I achieved and what I believed was strong in my application. This is what I believe will be most helpful for you. I hope you don't misinterpret this as bragging about my accomplishments. I'm here to show you what it took for me to get into Harvard and other Ivy League schools, not to ask for your admiration. So if you read this guide and are tempted to dismiss my advice because you think I'm boasting, take a step back and focus on the big picture—how you'll improve yourself.

This guide is geared toward admissions into the top colleges in the country , often with admissions rates below 10%. A sample list of schools that fit into this: Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Stanford, Columbia, MIT, UChicago, Duke, UPenn, CalTech, Johns Hopkins, Dartmouth, Northwestern, Brown. The top 3-5 in that list are especially looking for the absolute best students in the country , since they have the pick of the litter.

Admissions for these selective schools works differently from schools with >20% rates. For less selective schools, having an overall strong, well-rounded application is sufficient for getting in. In particular, having an above average GPA and test scores goes the majority of the way toward getting you admission to those schools. The higher the admission rate, the more emphasis will be placed on your scores. The other pieces I'll present below—personal statements, extracurriculars, recommendations—will matter less.

Still, it doesn't hurt to aim for a stronger application. To state the obvious, an application strong enough to get you Columbia will get you into UCLA handily.

In my application, I've redacted pieces of my application for privacy reasons, and one supplementary recommendation letter at the request of the letter writer. Everything else is unaltered.

Throughout my application, we can see marks made by the admissions officer highlighting and circling things of note (you'll see the first example on the very first page). I don't have any other applications to compare these to, so I'm going to interpret these marks as best I can. For the most part, I assume that whatever he underlines or circles is especially important and noteworthy —points that he'll bring up later in committee discussions. It could also be that the reader got bored and just started highlighting things, but I doubt this.

Finally, I co-founded and run a company called PrepScholar . We create online SAT/ACT prep programs that adapt to you and your strengths and weaknesses . I believe we've created the best prep program available, and if you feel you need to raise your SAT/ACT score, then I encourage you to check us out . I want to emphasize that you do NOT need to buy a prep program to get a great score , and the advice in this guide has little to do with my company. But if you're aren't sure how to improve your score and agree with our unique approach to SAT/ACT prep, our program may be perfect for you.

With all this past us, let's get started.

The #1 Most Important College Application Question: What Is Your PERSONAL NARRATIVE?

If you stepped into an elevator with Yale's Dean of Admissions and you had ten seconds to describe yourself and why you're interesting, what would you say?

This is what I call your PERSONAL NARRATIVE. These are the three main points that represent who you are and what you're about . This is the story that you tell through your application, over and over again. This is how an admissions officer should understand you after just glancing through your application. This is how your admissions officer will present you to the admissions committee to advocate for why they should accept you.

The more unique and noteworthy your Personal Narrative is, the better. This is how you'll stand apart from the tens of thousands of other applicants to your top choice school. This is why I recommend so strongly that you develop a Spike to show deep interest and achievement. A compelling Spike is the core of your Personal Narrative.

Well-rounded applications do NOT form compelling Personal Narratives, because "I'm a well-rounded person who's decent at everything" is the exact same thing every other well-rounded person tries to say.

Everything in your application should support your Personal Narrative , from your course selection and extracurricular activities to your personal statements and recommendation letters. You are a movie director, and your application is your way to tell a compelling, cohesive story through supporting evidence.

Yes, this is overly simplistic and reductionist. It does not represent all your complexities and your 17 years of existence. But admissions offices don't have the time to understand this for all their applicants. Your PERSONAL NARRATIVE is what they will latch onto.

Here's what I would consider my Personal Narrative (humor me since I'm peacocking here):

1) A science obsessive with years of serious research work and ranked 6 th in a national science competition, with future goals of being a neuroscientist or physician

2) Balanced by strong academic performance in all subjects (4.0 GPA and perfect test scores, in both humanities and science) and proficiency in violin

3) An irreverent personality who doesn't take life too seriously, embraces controversy, and says what's on his mind

These three elements were the core to my application. Together they tell a relatively unique Personal Narrative that distinguishes me from many other strong applicants. You get a surprisingly clear picture of what I'm about. There's no question that my work in science was my "Spike" and was the strongest piece of my application, but my Personal Narrative included other supporting elements, especially a description of my personality.

My College Application, at a High Level

Drilling down into more details, here's an overview of my application.

- This put me comfortably in the 99 th percentile in the country, but it was NOT sufficient to get me into Harvard by itself ! Because there are roughly 4 million high school students per year, the top 1 percentile still has 40,000 students. You need other ways to set yourself apart.

- Your Spike will most often come from your extracurriculars and academic honors, just because it's hard to really set yourself apart with your coursework and test scores.

- My letters of recommendation were very strong. Both my recommending teachers marked me as "one of the best they'd ever taught." Importantly, they corroborated my Personal Narrative, especially regarding my personality. You'll see how below.

- My personal statements were, in retrospect, just satisfactory. They represented my humorous and irreverent side well, but they come across as too self-satisfied. Because of my Spike, I don't think my essays were as important to my application.

Finally, let's get started by digging into the very first pages of my Common Application.

There are a few notable points about how simple questions can actually help build a first impression around what your Personal Narrative is.

First, notice the circle around my email address. This is the first of many marks the admissions officer made on my application. The reason I think he circled this was that the email address I used is a joke pun on my name . I knew it was risky to use this vs something like [email protected], but I thought it showed my personality better (remember point #3 about having an irreverent personality in my Personal Narrative).

Don't be afraid to show who you really are, rather than your perception of what they want. What you think UChicago or Stanford wants is probably VERY wrong, because of how little information you have, both as an 18-year-old and as someone who hasn't read thousands of applications.

(It's also entirely possible that it's a formality to circle email addresses, so I don't want to read too much into it, but I think I'm right.)

Second, I knew in high school that I wanted to go into the medical sciences, either as a physician or as a scientist. I was also really into studying the brain. So I listed both in my Common App to build onto my Personal Narrative.

In the long run, both predictions turned out to be wrong. After college, I did go to Harvard Medical School for the MD/PhD program for 4 years, but I left to pursue entrepreneurship and co-founded PrepScholar . Moreover, in the time I did actually do research, I switched interests from neuroscience to bioengineering/biotech.

Colleges don't expect you to stick to career goals you stated at the age of 18. Figuring out what you want to do is the point of college! But this doesn't give you an excuse to avoid showing a preference. This early question is still a chance to build that Personal Narrative.

Thus, I recommend AGAINST "Undecided" as an area of study —it suggests a lack of flavor and is hard to build a compelling story around. From your high school work thus far, you should at least be leaning to something, even if that's likely to change in the future.

Finally, in the demographic section there is a big red A, possibly for Asian American. I'm not going to read too much into this. If you're a notable minority, this is where you'd indicate it.

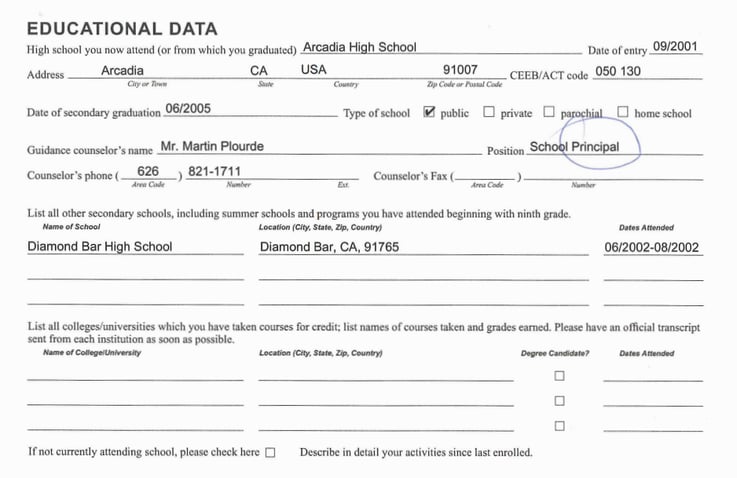

Now known as: Education

This section was straightforward for me. I didn't take college courses, and I took a summer chemistry class at a nearby high school because I didn't get into the lottery at my school that year (I refer to this briefly in my 4.0 GPA guide ).

The most notable point of this section: the admissions officer circled Principal here . This is notable because our school Principal only wrote letters for fewer than 10 students each year. Counselors wrote letters for the other hundreds of students in my class, which made my application stand out just a little.

I'll talk more about this below, when I share the Principal's recommendation.

(In the current Common Application, the Education section also includes Grades, Courses, and Honors. We'll be covering each of those below).

Now known as: Testing

Back then AP scores weren't part of this section, but I'll take them from another part of my application here.

However, their standards are still very high. You really do want to be in that top 1 percentile to pass the filter. A 1400 on the SAT IS going to put you at a disadvantage because there are so many students scoring higher than you. You'll really have to dig yourself out of the hole with an amazing application.

I talk about this a lot more in my Get into Harvard guide (sorry to keep linking this, but I really do think it's an important guide for you to read).

Let's end this section with some personal notes.

Even though math and science were easy for me, I had to put in serious effort to get an 800 on the Reading section of the SAT . As much as I wish I could say it was trivial for me, it wasn't. I learned a bunch of strategies and dissected the test to get to a point where I understood the test super well and reliably earned perfect scores.

I cover the most important points in my How to Get a Perfect SAT Score guide , as well as my 800 Guides for Reading , Writing , and Math .

Between the SAT and ACT, the SAT was my primary focus, but I decided to take the ACT for fun. The tests were so similar that I scored a 36 Composite without much studying. Having two test scores is completely unnecessary —you get pretty much zero additional credit. Again, with one test score, you have already passed their filter.

Finally, class finals or state-required exams are a breeze if you get a 5 on the corresponding AP tests .

Now known as: Family (still)

This section asks for your parent information and family situation. There's not much you can do here besides report the facts.

I'm redacting a lot of stuff again for privacy reasons.

The reader made a number of marks here for occupation and education. There's likely a standard code for different types of occupations and schools.

If I were to guess, I'd say that the numbers add to form some metric of "family prestige." My dad got a Master's at a middle-tier American school, but my mom didn't go to graduate school, and these sections were marked 2 and 3, respectively. So it seems higher numbers are given for less prestigious educations by your parents. I'd expect that if both my parents went to schools like Caltech and Dartmouth, there would be even lower numbers here.

This makes me think that the less prepared your family is, the more points you get, and this might give your application an extra boost. If you were the first one in your family to go to college, for example, you'd be excused for having lower test scores and fewer AP classes. Schools really do care about your background and how you performed relative to expectations.

In the end, schools like Harvard say pretty adamantly they don't use formulas to determine admissions decisions, so I wouldn't read too much into this. But this can be shorthand to help orient an applicant's family background.

Extracurricular, Personal, and Volunteer Activities

Now known as: Activities

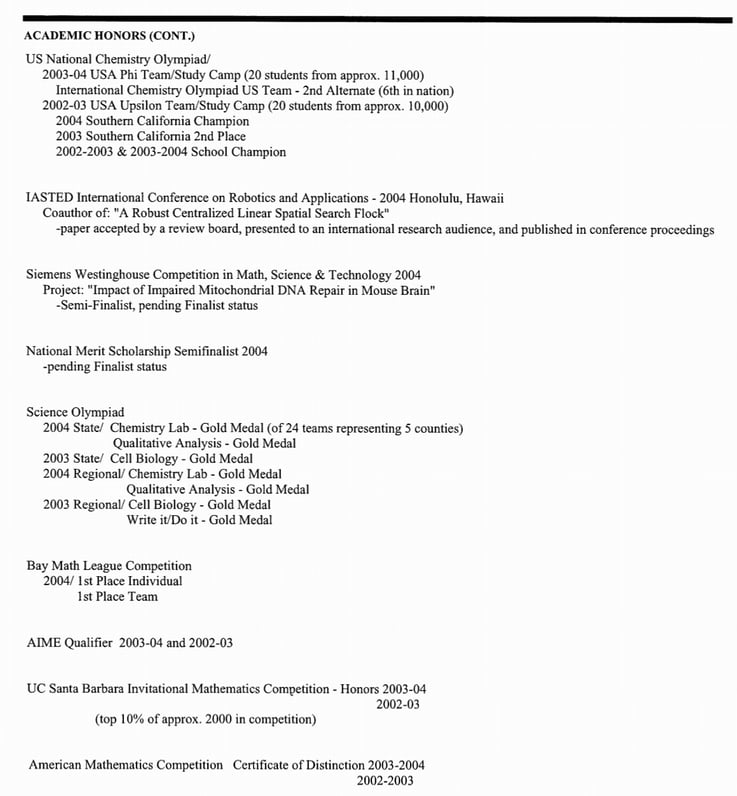

For most applicants, your Extracurriculars and your Academic Honors will be where you develop your Spike and where your Personal Narrative shines through. This was how my application worked.

Just below I'll describe the activities in more detail, but first I want to reflect on this list.

As instructed, my extracurriculars were listed in the order of their interest to me. The current Common App doesn't seem to ask for this, but I would still recommend it to focus your reader's attention.

The most important point I have to make about my extracurriculars: as you go down the list, there is a HUGE drop in the importance of each additional activity to the overall application. If I were to guess, I assign the following weights to how much each activity contributed to the strength of my activities section:

|

|

|

| Research Science Institute 2004 | 75% |

| Jisan Research Institute | 10% |

| Pasadena Young Musicians Orchestra | 6% |

| Science Olympiad/Science Bowl/Math Team | 4% |

| City of Hope Medical Center | 1% |

| Pre-Medicine Club | 1% |

| Hospital Quartet Performances | 1% |

| Chemistry Club | 1% |

In other words, participating in the Research Science Institute (RSI) was far more important than all of my other extracurriculars, combined. You can see that this was the only activity my admissions reader circled.

You can see how Spike-y this is. The RSI just completely dominates all my other activities.

The reason for this is the prestige of RSI. As I noted earlier, RSI was (and likely still is) the most prestigious research program for high school students in the country, with an admission rate of less than 5% . Because the program was so prestigious and selective, getting in served as a big confirmation signal of my academic quality.

In other words, the Harvard admissions reader would likely think, "OK, if this very selective program has already validated Allen as a top student, I'm inclined to believe that Allen is a top student and should pay special attention to him."

Now, it took a lot of prior work to even get into RSI because it's so selective. I had already ranked nationally in the Chemistry Olympiad (more below), and I had done a lot of prior research work in computer science (at Jisan Research Institute—more about this later). But getting into RSI really propelled my application to another level.

Because RSI was so important and was such a big Spike, all my other extracurriculars paled in importance. The admissions officer at Princeton or MIT probably didn't care at all that I volunteered at a hospital or founded a high school club .

This is a good sign of developing a strong Spike. You want to do something so important that everything else you do pales in comparison to it. A strong Spike becomes impossible to ignore.

In contrast, if you're well-rounded, all your activities hold equal weight—which likely means none of them are really that impressive (unless you're a combination of Olympic athlete, internationally-ranked science researcher, and New York Times bestselling author, but then I'd call you unicorn because you don't exist).

Apply this concept to your own interests—what can be so impressive and such a big Spike that it completely overshadows all your other achievements?

This might be worth spending a disproportionate amount of time on. As I recommend in my Harvard guide and 4.0 GPA guide , smartly allocating your time is critical to your high school strategy.

In retrospect, one "mistake" I made was spending a lot of time on the violin. Each week I spent eight hours on practice and a lesson and four hours of orchestra rehearsals. This amounted to over 1,500 hours from freshman to junior year.