- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Civic Education

In its broadest definition, “civic education” means all the processes that affect people’s beliefs, commitments, capabilities, and actions as members or prospective members of communities. Civic education need not be intentional or deliberate; institutions and communities transmit values and norms without meaning to. It may not be beneficial: sometimes people are civically educated in ways that disempower them or impart harmful values and goals. It is certainly not limited to schooling and the education of children and youth. Families, governments, religions, and mass media are just some of the institutions involved in civic education, understood as a lifelong process. [ 1 ] A rightly famous example is Tocqueville’s often quoted observation that local political engagement is a form of civic education: “Town meetings are to liberty what primary schools are to science; they bring it within the people’s reach, they teach men how to use and how to enjoy it.”

Nevertheless, most scholarship that uses the phrase “civic education” investigates deliberate programs of instruction within schools or colleges, in contrast to paideia (see below) and other forms of citizen preparation that involve a whole culture and last a lifetime. There are several good reasons for the emphasis on schools. First, empirical evidence shows that civic habits and values are relatively easily to influence and change while people are still young, so schooling can be effective when other efforts to educate citizens would fail (Sherrod, Flanagan, and Youniss, 2002). Another reason is that schools in many countries have an explicit mission to educate students for citizenship. As Amy Gutmann points out, school-based education is our most deliberate form of human instruction (1987, 15). Defining the purposes and methods of civic education in schools is a worthy topic of public debate. Nevertheless, it is important not to lose sight of the fact that civic education takes place at all stages of life and in many venues other than schools.

Whether defined narrowly or broadly, civic education raises empirical questions: What causes people to develop durable habits, values, knowledge, and skills relevant to their membership in communities? Are people affected differently if they vary by age, social or cultural background, and starting assumptions? For example, does a high school civics course have lasting effects on various kinds of students, and what would make it more effective?

From the 1960s until the 1980s, empirical questions concerning civic education were relatively neglected, mainly because of a prevailing assumption that intentional programs would not have significant and durable effects, given the more powerful influences of social class and ideology (Cook, 1985). Since then, many research studies and program evaluations have found substantial effects, and most social scientists who study the topic now believe that educational practices, such as discussion of controversial issues, hands-on action, and reflection, can influence students (Sherrod, Torney-Purta & Flanagan, 2010).

The philosophical questions have been less explored, but they are essential. For example:

Who has the full rights and obligations of a citizen? This question is especially contested with regard to children, immigrant aliens, and individuals who have been convicted of felonies.

In what communities ought we see ourselves as citizens? The nation-state is not the only candidate; some people see themselves as citizens of local geographical communities, organizations, movements, loosely-defined groups, or even the world as a whole.

What responsibilities does a citizen of each kind of community have? Do all members of each community have the same responsibilities, or ought there be significant differences, for example, between elders and children, or between leaders and other members?

What is the relationship between a good regime and good citizenship? Aristotle held that there were several acceptable types of regimes, and each needed different kinds of citizens. That makes the question of good citizenship relative to the regime-type. But other theorists have argued for particular combinations of regime and citizen competence. For example, classical liberals endorsed regimes that would make relatively modest demands on citizens, both because they were skeptical that people could rise to higher demands and because they wanted to safeguard individual liberty against the state. Civic republicans have seen a certain kind of citizenship--highly active and deliberative--as constitutive of a good life, and therefore recommend a republican regime because it permits good citizenship.

Who may decide what constitutes good citizenship? If we consider, for example, students enrolled in public schools in the United States, should the decision about what values, habits, and capabilities they should learn belong to their parents, their teachers, the children themselves, the local community, the local or state government, or the nation-state? We may reach different conclusions when thinking about 5-year-olds and adult college students. As Sheldon Wolin warned: “…[T]he inherent danger…is that the identity given to the collectivity by those who exercise power will reflect the needs of power rather than the political possibilities of a complex collectivity” (1989, 13). For some regimes—fascist or communist, for example—this is not perceived as a danger at all but, instead, the very purpose of their forms of civic education. In democracies, the question is more complex because public institutions may have to teach people to be good democratic citizens, but they can decide to do so in ways that reinforce the power of the state and reduce freedom.

What means of civic education are ethically appropriate? It might, for example, be effective to punish students who fail to memorize patriotic statements, or to pay students for community service, but the ethics of those approaches would be controversial. An educator might engage students in open discussions of current events because of a commitment to treating them as autonomous agents, regardless of the consequences. As with other topics, the proper relationship between means and ends is contested.

These questions are rarely treated together as part of comprehensive theories of civic education; instead, they arise in passing in works about politics or education. Some of these questions have never been much explored by professional philosophers, but they arise frequently in public debates about citizenship.

1.1 Ancient Greece

1.2 classical liberalism, 1.3 rousseau: toward progressive education, 1.4 mill: education through political participation, 1.5 early civic education in the united states, 2.1 the state, parents, and children in liberal democracies, 2.2 social capital, 2.3 deliberative democracy, 2.4 public work, 3.1 good persons and good citizens, 3.2 spectrum of virtues, 4.1 service learning, 4.2 action civics, 4.3 civic education through discussion, 4.4 john dewey: school as community, 4.5 liberation pedagogy, 5. cosmopolitan education, works cited, works to consult, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the good citizen: historical conceptions.

“As far back as evidence can be found—and virtually without exception—young adults seem to have been less attached to civic life than their parents and grandparents.” [ 2 ] That is not evidence of decline--although it is often read as such--but rather indicates that becoming a citizen is a developmental process. It must be taught and learned. Most if not all societies recognize a need to educate youth to be “civic-minded”; that is, to think and care about the welfare of the community (the commonweal or civitas ) and not simply about their own individual well-being. Sometimes, civic education is also intended to make all citizens, or at least prospective leaders, effective as citizens or to reduce disparities in political power by giving everyone the knowledge, confidence, and skills they need to participate. This section briefly introduces several conceptions of civic education that have been influential in the history of the West. [ 3 ]

The ancient Greek city state or polis was thought to be an educational community, expressed by the Greek term paideia . The purpose of political—that is civic or city—life was the self-development of the citizens. This meant more than just education, which is how paideia is usually translated. Education for the Greeks involved a deeply formative and life-long process whose goal was for each person (read: man) to be an asset to his friends, to his family, and, most important, to the polis.

Becoming such an asset necessitated internalizing and living up to the highest ethical ideals of the community. So paideia included education in the arts, philosophy and rhetoric, history, science, and mathematics; training in sports and warfare; enculturation or learning of the city’s religious, social, political, and professional customs and training to participate in them; and the development of one’s moral character through the virtues. Above all, the person should have a keen sense of duty to the city. Every aspect of Greek culture in the Classical Age—from the arts to politics and athletics—was devoted to the development of personal powers in public service.

Paideia was inseparable from another Greek concept: arete or excellence, especially excellence of reputation but also goodness and excellence in all aspects of life. Together paideia and arête form one process of self-development, which is nothing other than civic-development. Thus one could only develop himself in politics, through participation in the activities of the polis; and as individuals developed the characteristics of virtue, so would the polis itself become more virtuous and excellent.

All persons, whatever their occupations or tasks, were teachers, and the purpose of education—which was political life itself—was to develop a greater (a nobler, stronger, more virtuous) public community. So politics was more than regulating or ordering the affairs of the community; it was also a “school” for ordering the lives—internal and external—of the citizens. Therefore, the practice of Athenian democratic politics was not only a means of engendering good policies for the city, but it was also a “curriculum” for the intellectual, moral, and civic education of her citizens. “…[A]sk in general what great benefit the state derives from the training by which it educates its citizens, and the reply will be perfectly straightforward. The good education they have received will make them good men…” (Plato, Laws , 641b7–10). Indeed, later in the Laws the Athenian remarks that education should be designed to produce the desire to become “perfect citizens” who know, preceding Aristotle, “how to rule and be ruled” (643e4–6).

Ancient and medieval thinkers generally assumed that good government and good citizenship were intimately related, because a regime would degenerate unless its people actively and virtuously supported it. Aristotle regarded his Politics and his Ethics as part of the same subject. In his view, a city-state could not be just and strong unless its people were virtuous, and men could not exercise the political virtues (which were intrinsically admirable, dignified, and satisfying) unless they lived in a just polity. Civic virtue was especially important in a democratic or mixed regime, but even in a monarchy or oligarchy, people were expected to sustain the political community.

Today, the view that the best life is one of active participation in a community that relies on and encourages active engagement is often called “civic republicanism,” and it has been developed by authors like Wolin (1989), Barber (1992) and Hannah Arendt.

Classical liberal thinkers, however, saw serious drawbacks to making good government dependent on widespread civic virtue. First, any demanding and universal system of moral education would be incompatible with individual freedom. If, for example the state forced people to enroll their children in public schools in order to create good citizens, it would hamper parents and young people’s individual freedom.

The second problem was more practical. States did not have a very good record of producing moral virtue in rulers or subjects. Mandatory church membership, state-subsidized education, and even public spectacles of torture and execution did not reliably prevent corruption, sedition and other private behavior injurious to the community.

Thomas Hobbes is sometimes described as a forerunner of liberalism (despite his advocacy of absolute monarchy) because he held a dim view of human nature and thought that the way to prevent political disaster was to design the government right, not to try to improve civic virtue. He also held that a good government was one that permitted people to live their own lives safely. Another strong critic of the idea that a good society depended on civic virtue was Bernard Mandeville, who wrote a famous 1705 poem entitled, “The Fable of The Bees: or, Private Vices, Public Benefits.” Mandeville argued that a good society could arise from sheer individual self-interest if it was organized appropriately.

Other classical liberal thinkers typically favored some degree of civic education and civic virtue, even as they proposed limitations on the state and a strong private sphere to reduce the dependence of the regime on civic virtue. In other words, they steered a middle course between pure classical liberalism and civic republicanism. For example, in his “Instructions for the conduct of a young Gentleman, as to religion and government,” John Locke wrote that a gentleman’s “proper calling is the service of his country, and so is most properly concerned in moral and political knowledge; and thus the studies which more immediately belong to his calling are those which treat of virtues and vices, of civil society and the arts of government, and will take in also law and history.” That was an argument for civic education. But it appeared in a minor, unpublished fragment (Locke 1703: 350). Civic education was not a significant theme in Locke’s important treatise Some Thoughts Concerning Education (1693), which was more about teaching individuals to be free and responsible in their private lives. Likewise, the emphasis of his political writing was on limiting the power of the state and protecting private rights.

James Madison hoped for some degree of civic virtue in the people and especially in their representatives. He endorsed “the great republican principle, that the people will have the virtue and intelligence to select men of virtue and wisdom. Is there no virtue among us? If there be not, we are in a wretched situation. No theoretical checks--no form of government can render us secure” (Madison, 1788, 11:163) On the other hand, Madison proposed a whole series of reforms that would make government proof against the various vices that seemed to be “sown in the nature of man” (Madison, Hamilton, and Jay, Federalist 10). These tools included constitutional limitations on the overall power and scope of government; independent judges with power of review; elections with relatively broad franchise; and above all, checks and balances.

Madison explained that republics should be designed for people of moderate virtue, such as might be found in real societies. “If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controuls on government would be necessary.” Unfortunately, neither citizens nor rulers could be counted on to act like angels; but good government was possible anyway, as long as the constitution provided appropriate controls.

The main “external controul” in a republic was the vote, which made powerful men accountable to those they ruled. However, voting was not enough, especially since the voters themselves might lack virtue and wisdom. “A dependence on the people is no doubt the primary controul on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.” In general, Madison’s “auxiliary precautions” involved dividing power among separate institutions and giving them the ability to check one another.

This policy of supplying by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives, might be traced through the whole system of human affairs, private as well as public. We see it particularly displayed in all the subordinate distributions of power; where the constant aim is to divide and arrange the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other; that the private interest of every individual may be a centinel over the public rights. These inventions of prudence cannot be less requisite in the distribution of the supreme powers of the state. (Madison, Hamilton, and Jay, Federalist 51)

Although ancient Athens instituted democracy, her most famous philosophers—Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle—were not great champions of it. At best they were ambiguous about democracy; at worst, they were hostile toward it. The earliest unadulterated champion of democracy, a “dreamer of democracy,” was undoubtedly Rousseau. Yet Rousseau had his doubts that men could be good men and simultaneously good citizens. A good man for Rousseau is a natural man, with the attributes of freedom, independence, equality, happiness, sympathy, and love-of-self ( amour de soi ) found prior to society in the state of nature. Thus society could do little but corrupt such a man.

Still, Rousseau recognized that life in society is unavoidable, and so civic education or learning to function well in society is also unavoidable. The ideal for Rousseau is for men to act morally and yet retain as much of their naturalness as possible. Only in this way can a man retain his freedom; and only if a man follows those rules that he prescribes for himself—that is, only if a man is self-ruling—can he remain free: “…[E]ach individual…obeys no one but himself and remains as free as before [society]” (1988, 60).

Yet prescribing those rules is not a subjective or selfish act. It is a moral obligation because the question each citizen asks himself or should ask himself was not “What’s best for me?” Rather, each asks, “What’s best for all?” When all citizens ask this question and answer on the basis of what ought to be done, then, says Rousseau, they are expressing and following the general will. Enacting the general will is the only legitimately moral foundation for a law and the only expression of moral freedom. Getting men to ask this question and to answer it actively is the purpose of civic education.

Showing how to educate men to retain naturalness and yet to function in society and participate untouched by corruption in this direct democracy was the purpose of his educational treatise, Emile . If it could be done, Rousseau would show us the way. To do it would seem to require educating a man to be in society but not of society; that is, to be “attached to human society as little as possible” (Ibid, 105).

How could a man for Rousseau be a good man—meaning, for him a naturally good man (1979, 93), showing his amour de soi and also his natural compassion for others—and also have the proper frame of mind of a good citizen to be able to transcend self-interest and prescribe the general will? How could this be done in society when society’s influence is nothing but corrupting?

Rousseau himself seems ambivalent on exactly whether men can overcome social corruption. Society is based on private property; private property brings inequality, as some own more than others; such inequality brings forth social comparisons with others ( amour propre ), which in turn can produce envy, pride, and greed. Only when and if men can exercise their moral and political freedom and will the general will can they be saved from the corrupting influences of society. Willing for the general will, which is the good for all, is the act of a moral or good person. Its exercise in the assembly is the act of a good citizen.

Still, Rousseau comments that if “[f]orced to combat nature or the social institutions, one must choose between making a man or a citizen, for one cannot make both at the same time” (Ibid, 39). There seems little, if any, ambiguity here. One cannot make both a man and a citizen at the same time. Yet on the very next page of Emile Rousseau raises the question of whether a man who remains true to himself, to his nature, and is always decisive in his choices “is a man or a citizen, or how he goes about being both at the same time” (Ibid, 40).

Perhaps the contradiction might be resolved if we emphasize that a man cannot be made a man and a citizen at the same time, but he can be a man and a citizen at the same time. Rousseau hints at this distinction when he says of his educational scheme that it avoids the “two contrary ends…the contrary routes…these different impulses…[and] these necessarily opposed objects” (Ibid, 40, 41) when you raise a man “uniquely for himself.” What, then, will he be for others? He will be a man and a citizen, for the “double object we set for ourselves,” those contradictory objects, “could be joined in a single one by removing the contradictions of man…” (Idem). Doubtless, this will be a rare man, but raising a man to live a natural life can be done.

One might find the fully mature, and natural, Emile an abhorrent person. Although “good” in the sense of doing his duty and acting civilly, he seems nevertheless without imagination or deep curiosity about people or life itself—no interest in art or many books or intimate social relationships. Is his independence fear of dependence and thus built on an inability ever to be interdependent? Is he truly independent, or does he exhibit simply the appearance of independence, while the tutor “remains master of his person” (Ibid, 332)?

Whatever one thinks of Rousseau’s attempt to educate Emile—whether, for example, the tutor’s utter control of Emile’s life and environment is not in itself a betrayal of education—Rousseau is a precursor of those progressive educators who seek to permit children to learn at their own rate and from their own experiences, as we shall see below.

Mill argued that participation in representative government, or democracy, is undertaken both for its educative effects on participants and for the beneficial political outcomes. Even if elected or appointed officials can perform better than citizens, Mill thought it advisable for citizens to participate “as a means to their own mental education—a mode of strengthening their active faculties, exercising their judgment, and giving them a familiar knowledge of the subjects with which they are thus left to deal. This is a principal, though not the sole, recommendation of jury trial; of free and popular local and municipal institutions; of the conduct of industrial and philanthropic enterprises by voluntary associations” (1972, 179). Thus, political participation is a form of civic education good for men and for citizens.

On Liberty , the essay in which the above quotation appears, is not, writes Mill, the occasion for developing this idea as it relates to “parts of national education.” But in Mill’s view the development of the person can and should be undertaken in concert with an education for citizens. The “mental education” he describes is “in truth, the peculiar training of a citizen, the practical part of the political education of a free people, taking them out of the narrow circle of personal and family selfishness, and accustoming them to the comprehension of joint interests, the management of joint concerns—habituating them to act from public or semi-public motives, and guide their conduct by aims which unite instead of isolating them from one another” (Idem).

The occasion for discussing civic education as a method of both personal and political development is Mill’s Considerations on Representative Government . Mill wants to see persons “progress.” To achieve progress requires “the preservation of all kinds and amounts of good which already exist, and Progress as consisting in the increase of them.” Of what does Mill’s good consist? First are “the qualities in the citizens individually which conduce most to keep up the amount of good conduct…Everybody will agree that those qualities are industry, integrity, justice, and prudence” (1972, 201). Add to these “the particular attributes in human beings which seem to have a more especial reference to Progress…They are chiefly the qualities of mental activity, enterprise, and courage” (Ibid, 202).

So, progress is encouraged when society develops the qualities of citizens and persons. Mill tells us that good government depends on the qualities of the human beings that compose it. Men of virtuous character acting in and through justly administered institutions will stabilize and perpetuate the good society. Good persons will be good citizens, provided they have the requisite political institutions in which they can participate. Such participation—as on juries and parish offices—takes participants out of themselves and away from their selfish interests. If that does not occur, if persons regard only their “interests which are selfish,” then, concludes Mill, good government is impossible. “…[I]f the agents, or those who choose the agents, or those to whom the agents are responsible, or the lookers-on whose opinion ought to influence and check all these, are mere masses of ignorance, stupidity, and baleful prejudice, every operation of government will go wrong” (Ibid, 207).

For Mill good government is a two-way street: Good government depends on “the virtue and intelligence of the human beings composing the community”; while at the same time government can further “promote the virtue and intelligence of the people themselves” (Idem). A measure of the quality of any political institution is how far it tends “to foster in the members of the community the various desirable qualities…moral, intellectual, and active” (Ibid, 208). Good persons act politically as good citizens and are thereby maintained or extended in their goodness. “A government is to be judged by its actions upon men…by what it makes of the citizens, and what it does with them; its tendency to improve or deteriorate the people themselves.” Government helps people advance, acts for the improvement of the people, “is at once a great influence acting on the human mind….” Government is, then, “an agency of national education…” (Ibid, 210, 211).

Following Tocqueville, Mill saw political participation as the basis for this national education. “It is not sufficiently considered how little there is in most men’s ordinary life to give any largeness either to their conceptions or to their sentiments.” Their work is routine and dull; they proceed through life without much interest or energy. On the other hand, “if circumstances allow the amount of public duty assigned him to be considerable, it makes him an educated man” (Ibid, 233). In this way participation in democratic institutions “must make [persons] very different beings, in range of ideas and development of faculties, from those who have done nothing in their lives but drive a quill, or sell goods over a counter” (Idem).

There was no national public schooling in Mill’s Great Britain, and there were clearly lots of Britons without the requisite characteristics either of good citizens or of good men. Mill was certainly aware of this. He was much influenced by Tocqueville’s writings on the tyranny of the majority. Mill feared, as did Tocqueville, that the undereducated or uneducated would dominate and tyrannize politics so as to undermine authority and individuality. Being ignorant and inexperienced, the uneducated and undereducated would be susceptible to all manner of demagoguery and manipulation. So too much power in the hands of the inept and ignorant could damage good citizenship and dam the course of self-development. To remedy this Mill proposed two solutions: limit participation and provide the competent and educated with plural votes.

In Mill’s “ideally best polity” the highest levels of policymaking would be reserved for nationally elected representatives and for experts in the civil service. These representatives and experts would not only carry out their political duties, but they would also educate the public through debate and deliberation in representative assemblies, in public forums, and through the press. To assure that the best were elected and for the sake of rational government, Mill provided plural votes to those with college educations and to those of certain occupations and training. All citizens (but the criminal and illiterate) could vote, but not all citizens would vote equally. Some citizens, because they were educated or highly trained persons, were “better” than others: “…[T]hough every one ought to have a voice—that every one should have an equal voice is a totally different proposition…No one but a fool…feels offended by the acknowledgment that there are others whose opinion, and even whose wish, is entitled to a greater amount of consideration than his” (Ibid, 307–8).

But education was the great leveling factor. Though not his view when he wrote Considerations on Representative Government , Mill wrote in his autobiography that universal education could make plural voting unnecessary (1924, pp. 153, 183–84). Mill did acknowledge in Representative Government that a national system of education or “a trustworthy system of general examination” would simplify the means of ascertaining “mental superiority” of some persons over others. In their absence, a person’s years of schooling and nature of occupation would suffice to determine who would receive plural votes (1972, 308–09). Given Mill’s prescriptions for political participation and given the lessons learned from the deliberations and debates of representatives and experts, however, it is doubtful that civic education would have constituted much of his national education.

As noted above the founders of the United States tried to reduce the burdens on citizens, because they observed that republics had generally collapsed for lack of civic virtue. [ 4 ] However, they also created a structure that would demand more of citizens, and grant citizens more rights, than the empire from which they had declared independence. So virtually all of the founders advocated greater attention to civic education. When Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist 23 that the federal government ought to be granted “an unconfined authority in respect to all those objects which are entrusted to its management” (1987, p. 187), he underscored the need of the newly organized central government for, in Sheldon Wolin’s words, “a new type of citizen…one who would accept the attenuated relationship with power implied if voting and elections were to serve as the main link between citizens and those in power.” [ 5 ] Schools would be entrusted to develop this new type of citizen.

It is commonplace, therefore, to find among those who examine the interstices of democracy and education views much like Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s: “That the schools make worthy citizens is the most important responsibility placed on them.” In the United States public schools had the mission of educating the young for citizenship.

Initially education in America was not publicly funded. It wasn’t even a system, however inchoate. Instead it was every community for itself. Nor was it universal education. Education was restricted to free white males and, moreover, free white males who could afford the school fees. One of the “founders” of the public-school system in the United States, even though his era predated the establishment of public schools, was Noah Webster, who saw education as the tool for developing a national identity. As a result, he created his own speller and dictionary as a way of advancing a common American language.

Opposed to this idea of developing a national identity was Thomas Jefferson, who saw education as the means for safeguarding individual rights, especially against the intrusions of the state. Central to Jefferson’s democratic education were the “liberal arts.” These arts liberate men and women (though Jefferson was thinking only of men) from the grip of both tyrants and demagogues and enable those liberated to rule themselves. Through his ward system of education, Jefferson proposed establishing free schools to teach reading, writing, and arithmetic, and from these schools those of intellectual ability, regardless of background or economic status, would receive a college education paid for by the state.

When widespread free or publicly funded education did come to America in the 19 th century, it came in the form of Horace Mann’s “common school.” Such schools would educate all children together, “in common,” regardless of their background, religion, or social standing. Underneath such fine sentiments lurked an additional goal: to ensure that all children could flourish in America’s democratic system. The civic education curriculum was explicit, if not simplistic. To create good citizens and good persons required little beyond teaching the basic mechanics of government and imbuing students with loyalty to America and her democratic ideals. That involved large amounts of rote memorization of information about political and military history and about the workings of governmental bodies at the local, state, and federal levels. It also involved conformity to specific rules describing conduct inside and outside of school.

Through this kind of civic education, all children would be melded, if not melted, into an American citizen. A heavy emphasis on Protestantism at the expense of Catholicism was one example of such work. What some supporters might have called “assimilation” of foreigners into an American way of life, critics saw as “homogenization,” “normalization,” and “conformity,” if not “uniformity.” With over nine million immigrants coming to America between 1880 and the First World War, it is not surprising that there was resistance by many immigrant communities to what seemed insensitivity to foreign language and culture. Hence what developed was a system of religious—namely Catholic—education separate from the “public school” system.

While Webster and, after him, Mann wanted public education to generate the national identity that they thought democracy required, later educational reformers moved away from the idea of the common school and toward a differentiation of students. The Massachusetts Commission on Industrial and Technical Education, for example, pushed in 1906 for industrial and vocational education in the public schools. Educating all youth equally for participation in democracy by giving them a liberal, or academic, education, they argued, was a waste of time and resources. “School reformers insisted that the academic curriculum was not appropriate for all children, because most children—especially the children of immigrants and of African Americans—lacked the intellectual capacity to study subjects like algebra and chemistry” (Ravitch, 2001, 21).

Acting against this view of education was John Dewey. Because Dewey saw democracy as a way of life, he argued that all children deserved and required a democratic education. [ 6 ] As citizens came to share in the interests of others, which they would do in their schools, divisions of race, class, and ethnicity would be worn down and transcended. Dewey thought that the actual interests and experiences of students should be the basis of their education. I recur to a consideration of Dewey and civic education below.

2. The Good Democrat

Civic education can occur in all kinds of regimes, but it is especially important in democracies. In The Politics, Aristotle asks whether there is any case “in which the excellence of the good citizen and the excellence of the good man coincide” (1277a13–15). The answer for him is a politea or a mixed constitution in which persons must know both how to rule and how to obey. In such regimes, the excellence and virtues of the good man and the good citizen coincide. Democratic societies have an interest in preparing citizens to rule and to be ruled.

Modern democracies, however, are different from the ancient polis in several important and pertinent respects. They are mass societies in which most people can have little individual impact on government and policy. They are complex, technologically-driven, highly specialized societies in which professionals (including lawyers, civil servants, and politicians) have much more expertise than laypeople. And they are liberal constitutional regimes in which individual freedom is protected--to various degrees--and government is deliberately insulated from public pressure. For example, courts and central banks are protected from popular votes. Once the United States had become an industrialized mass society, the influential columnist Walter Lippmann argued that ordinary citizens had been eclipsed and could, at most, render occasional judgments about a government of experts (see The Phantom Public, 1925). John Dewey and the Chicago civic leader Jane Addams (in different ways) asserted that the lay public must and could regain its voice, but they struggled to explain how.

Several contemporary philosophers argue that citizens have a relatively demanding role and that they can and should be educated for it. Gutmann (1987), for example, argues that democratic society-at-large has a significant stake in the education of its children, for they will grow up to be democratic citizens. At the very least, then, society has the responsibility for educating all children for citizenship. Because democratic societies have this responsibility, we cannot leave the education of future citizens to the will or whim of parents. This central insight leads Gutmann to rule out certain exclusive suzerainties of power over educational theory and policy. Those suzerainties are of three sorts. First is “the family state” in which all children are educated into the sole good life identified and fortified by the state. Such education cultivates “a level of like-mindedness and camaraderie among citizens” that most persons find only in families (Ibid, 23). Only the state can be entrusted with the authority to mandate and carry out an education of such magnitude that all will learn to desire this one particular good life over all others.

Next is “the state of families” that rests on the impulse of families to perpetuate their values through their children. This state “places educational authority exclusively in the hands of parents, thereby permitting parents to predispose their children, through education, to choose a way of life consistent with their familial heritage” (Ibid, 28).

Finally, Gutmann argues against “the state of individuals,” which is based on a notion of liberal neutrality in which both parents and the state look to educational experts to make certain that no way of life is neglected nor discriminated against. The desire here is to avoid controversy, and to avoid teaching virtues, in a climate of social pluralism. Yet, as Gutmann points out, any educational policy is itself a choice that will shape our children’s character. Choosing to educate for freedom rather than for virtue is still insinuating an influential choice.

In light of these three theories that fail to provide an adequate foundation for educational authority, Gutmann proposes “a democratic state of education.” This state recognizes that educational authority must be shared among parents, citizens, and educational professionals, because each has a legitimate interest in each child and the child’s future. Whatever our aim of education, whatever kind of education these authorities argue for, it will not be, it cannot be, neutral. Needed is an educational aim that is inclusive. Gutmann settles on our inclusive commitment as democratic citizens to conscious social reproduction, the self-conscious shaping of the structures of society. To actuate this commitment we as a society “must educate all educable children to be capable of participating in collectively shaping their society” (Ibid, 14).

To shape the structures of society, to engage in conscious social reproduction, students will need to develop the capacities for examining and evaluating competing conceptions of the good life and the good society, and society must avoid the inculcation “in children [of the] uncritical acceptance of any particular way or ways of [personal and political] life” (Ibid, 44). This is the crux of Gutmann’s democratic education. For this reason, she argues forcefully that children must learn to exercise critical deliberation among good lives and, presumably, good societies. To assure that they can do so, limits must be set for when and where parents and the state can interfere. Guidelines must be introduced that limit the political authority of the state and the parental authority of families. One limit is nonrepression, which assures that neither the state nor any group within it can “restrict rational deliberation of competing conceptions of the good life and the good society” (Idem). In this way, adults cannot use their freedom to deliberate to prohibit the future deliberative freedom of children. Furthermore, claims Gutmann, nonrepression requires schools to support “the intellectual and emotional preconditions for democratic deliberation among future generations of citizens” (Ibid, 76.)

The second limit is nondiscrimination, which prevents the state or groups within the state from excluding anyone or any group from an education in deliberation. Thus, as Gutmann says, “all educable children must be educated” (Ibid, 45).

Gutmann’s point is not that the state has a greater interest than parents in the education of our children. Instead, her point is that all citizens of the state have a common interest in educating future citizens. Therefore, while parents should have a say in the education of their children, the state should have a say as well. Yet neither should have the final, or a monopolistic, say. Indeed, these two interested parties should also cede some of their educational authority to educational experts. There is, therefore, a collective interest in schooling, which is why Gutmann finds parental “choice” and voucher programs unacceptable.

But is conscious social reproduction the only aim of education? What about shaping one’s private concerns? Isn’t educating the young to be good persons also important? Or are the skills that encourage citizen participation also the skills necessary for making personal life choices and personal decision-making? For Gutmann, educating for one is also educating for the other: “…[M]any if not all of the capacities necessary for choice among good lives are also necessary for choice among good societies” (p. 40). She goes even further: “a good life and a good society for self-reflective people require (respectively) individual and collective freedom of choice” (Idem). Here Gutmann is stipulating that to have conscious social reproduction citizens must have the opportunity—the freedom and the capacities—to exercise personal or self-reflective choice.

Because the state is interested in the education of future citizens, all children must develop those capacities necessary for choice among good societies; this is simply what Gutmann means by being able to participate in conscious social reproduction. Yet such capacities also enable persons to scrutinize the ways of life that they have inherited. Thus, Gutmann concludes, it is illegitimate for any parent to impose a particular way of life on anyone else, even on his/her own child, for this would deprive the child of the capacities necessary for citizenship as well as for choosing a good life.

Gutmann’s position is that government can and must force one to participate in an education for citizenship. Children must be exposed to ways of life different from their parents’ and must embrace certain values such as mutual respect. On this last point Gutmann is insistent. She argues that choice is not meaningful, for anyone, unless persons choosing have “the intellectual skills necessary to evaluate ways of life different from that of their parents.” Without the teaching of such skills as a central component of education children will not be taught “mutual respect among persons” (Ibid, 30–31). “Teaching mutual respect is instrumental to assuring all children the freedom to choose in the future…[S]ocial diversity enriches our lives by expanding our understanding of differing ways of life. To reap the benefits of social diversity, children must be exposed to ways of life different from their parents and—in the course of their exposure—must embrace certain values, such as mutual respect among persons…” (Ibid, 32–33).

Yet what Gutmann suggests seems to go beyond seeing diversity as enrichment. She suggests that children not simply tolerate ways of life divergent from their own, but that they actually respect them. She is careful to say “mutual respect among persons,” which can only mean that neo-Nazis, while advocating an execrable way of life, must be respected as persons, though their way of life should be condemned. Perhaps this is a subtlety that Gutmann intended, but William Galston, for one, has come away thinking that Gutmann advocates forcing children to confront their own ways of life as they simultaneously show respect for neo-Nazis.

In our representative system, argues Galston, citizens need to develop “the capacity to evaluate the talents, character, and performance of public officials” (1989, p. 93). This, he says, is what our democratic system demands from citizens. Thus he disagrees with Gutmann, so much so that he says, “It is at best a partial truth to characterize the United States as a democracy in Gutmann’s sense” (Ibid, p. 94). We do not require deliberation among our citizens, says Galston, because “representative institutions replace direct self-government for many purposes” (Idem). Civic education, therefore, should not be about teaching the skills and virtues of deliberation, but, instead, about teaching “the virtues and competences needed to select representatives wisely, to relate to them appropriately, and to evaluate their performance in office soberly” (Idem).

Because civic education is limited in scope to what Galston outlines above, students will not be expected, and will not be taught, to evaluate their own ways of life. Persons must be able to lead the kinds of lives they find valuable, without fear that they will be coerced into believing or acting or thinking contrary to their values, including being led to question those ways of life that they have inherited. As Galston points out, “[c]ivic tolerance of deep differences is perfectly compatible with unswerving belief in the correctness of one’s own way of life” (Ibid, p. 99).

Some parents, for example, are not interested in having their children choose ways of life. Those parents believe that the way of life that they currently follow is not simply best for them but is best simpliciter . To introduce choice is simply to confuse the children and the issue. If you know the true way to live, is it best to let your children wade among diverse ways of life until they can possibly get it right? Or should you socialize the children into the right way of life as soon and as quickly as possible?

Yet what about the obligations that parents, as citizens, and children as future citizens, owe the state? How can children be prepared to participate in collectively shaping society if they have not received an education in how to deliberate about choices? To this some parents might respond that they are not interested in having their children focus on participation, or perhaps on anything secular. What these parents appreciate about liberal democracy is that there is a clear, and firm, separation between public and private, and they seek to focus exclusively on the private. Citizenship offers protections of the law, and it does not require participation. Liberal democracy certainly will not force one to participate.

Yet both Galston and Gutmann want to educate children for “democratic character.” Both see the need in this respect for critical thinking. For Galston children must develop “the capacity to evaluate the talents, character, and performance of public officials”; Gutmann seeks to educate the capacities necessary for choice among good lives and for choice among good societies. However much critical thinking plays in democratic character, active participation requires something more than mere skills, even thinking skills.

The concept of “social capital” was introduced by the sociologist James S. Coleman to refer to the value that is inherent in social networks (see, e.g., Coleman, 1988). The political scientist Robert Putnam subsequently argued that democracies function well in proportion to the strength of their social capital (1994) and that social capital is declining in the United States (2000). In his book Bowling Alone , Putnam explains, “Whereas physical capital refers to physical objects and human capital refers to properties of individuals [such as their own skills], social capital refers to connections among individuals—social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them. In that sense social capital is closely related to what some have called ‘civic virtue.’ The difference is that ‘social capital’ calls attention to the fact that civic virtue is most powerful when embedded in a dense network of reciprocal social relations” (Putnam 2000, p. 19).

A related idea is “collective efficacy,” as developed by the sociologist Robert Sampson and colleagues. It is the use--or ability to use--social networks to address common problems, such as crime. Sampson finds that the level of collective efficacy strongly predicts the quality of life in communities (Sampson, 2012).

If governments and communities function much better when people have social networks and use them for public purposes, then civic education becomes important and it is substantially about teaching people to create, appreciate, preserve, and use social networks. A pedagogical approach like Service Learning (see below) might be most promising for that purpose.

Elinor Ostrom won the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for her work on how people overcome collective action problems, such as the Prisoner’s Dilemma and the Tragedy of the Commons. These problems are endemic and serious, sometimes leading to environmental catastrophe and war. Ostrom, however, discovered many principles that allow people to overcome such problems. She wrote,

At any time that individuals may gain from the costly action of others, without themselves contributing time and effort, they face collective action dilemmas for which there are coping methods. When de Tocqueville discussed the ‘art and science of association,’ he was referring to the crafts learned by those who had solved ways of engaging in collective action to achieve a joint benefit. Some aspects of the science of association are both counterintuitive and counterintentional, and thus must be taught to each generation as part of the culture of a democratic citizenry. (Ostrom 1998)

Ostrom believed that these principles could be taught explicitly and formally, but the traditional and most effective means for teaching them were experiential. She argued that the tendency to centralize and professionalize management throughout the 20th century had deprived ordinary people of opportunities to learn from experience, and thus our capacity to address collective action problems had weakened.

Along with her husband Vincent Ostrom, Elinor Ostrom developed the idea of polycentric governance, according to which we are citizens of multiple, overlapping, and nested communities, from the smallest neighborhoods to the globe. Collective action problems are best addressed polycentrically, not reserved for national governments or parceled out neatly among levels of government. As president of the American Political Science Association and in other prominent roles, Ostrom advocated civic education that would teach people to address collective action problems in multiple settings and scales.

Deliberative democracy is the idea that a legitimate political decision is one that results from discussions among citizens under reasonably favorable conditions. Proponents debate precisely what qualifies as deliberation, but there is a general agreement that the discussion should be inclusive, free, equitable, and in some sense civil. In practical terms, deliberative democracy implies various efforts to increase the amount and the impact of public discussions. The philosophical underpinnings derive from the work of influential theorists including Jürgen Habermas, John Rawls, Michael Sandel, and others of varying views. See Gutmann and Thompson (1996) for an example of a sophisticated treatment that draws on many earlier works.

For civic education, the implication of deliberative democracy is that people should learn to participate in discussions, which may be both face-to-face and “mediated” by the news media and social media. Concretely, that means that people should develop the aptitude, desire, knowledge, and skills that lead them to read and discuss the news and current events with diverse fellow citizens and influence the government with the views that they develop and refine by deliberation. Practices such as discussing and debating current events in school seem especially promising.

Harry C. Boyte (1996, 2004) argues for the centrality of work to citizenship. We are not only citizens when we vote, read and discuss the news, and volunteer after school or work--which are all unpaid, voluntary activities. We are also citizens on the job; and even when we perform unpaid service, we should see our contributions as work-like in the sense that they are serious business. Citizens do not merely monitor and influence the government (per the theory of deliberative democracy) nor serve other people in community settings (emphasized in the idea of social capital); they also literally build, make, and maintain public goods. They do so whether they work in the public, private, or nonprofit sectors, for pay or not. Of course, they can work either well or badly, and a good citizen is one who makes valuable contributions to the public good, or builds “the commonwealth.”

The theory of public work suggests that civic education should be highly experiential and closely related to vocational education. Young people should gain skills and agency by actually making things together. A good outcome is an individual who will be able to contribute to the commonwealth through her or his work. Albert Dzur (2008), who holds a kindred but not identical view, emphasizes the importance of revising professional education so that professionals learn to collaborate better with laypeople.

3. The Good Person

The qualities of the good citizen are not simply the skills necessary to participate in the political system. They are also the virtues that will lead one to participate, to want to participate, to have a disposition to participate. This is what Rousseau was referring to when he described how citizens in his ideal polity would “fly to the assemblies” (1988, 140). Citizens, that is, ought to display a certain kind of disposition or character. As it turns out, and not surprisingly, given our perspective, in a democracy the virtues or traits that constitute good citizenship are also closely associated with being a good or moral person. We can summarize that close association as what we mean by the phrase “good character.”

It is the absence of these virtues or traits—that is, the absence of character—that leads some to conclude that democracy, especially in the United States, is in crisis. The withering of our democratic system, argues Richard Battistoni, for one, can be traced to “a crisis in civic education” and the failure of our educators to prepare citizens for democratic participation (1985, pp. 4–5). Missing, he argues, is a central character trait, a disposition to participate. Crucial to the continuation of our democracy “is the proper inculcation in the young of the character, skills, values, social practices, and ideals that foster democratic politics” (Ibid, p. 15); in other words, educating for democratic character.

Two groups predominate in advocating the use of character education as a way of improving democracy. One group comprises political theorists such as Galston, Battistoni, Benjamin Barber, and Adrian Oldfield who often reflect modern-day versions of civic republicanism. This group wishes to instill or nurture [ 7 ] a willingness among our future citizens to sacrifice their self-interests for the sake of the common good. Participation on this view is important both to stabilize society and to enhance each individual’s human flourishing through the promotion of our collective welfare.

The second group does not see democratic participation as the center, but instead sees democratic participation as one aspect of overall character education. Central to the mission of our public schools, on this view, is the establishing of character traits important both to individual conduct (being a good person) and to a thriving democracy (being a good citizen). The unannounced leader of the second group is educational practitioner Thomas Lickona, and it includes such others as William Bennett and Patricia White.

Neither group describes in actual terms what might be called “democratic character.” Though their work intimates such character, they talk more about character traits important to human growth and well-being, which also happen to be related to democratic participation. What traits do these pundits discuss, and what do they mean by “character”?

It is difficult, comments British philosopher R. S. Peters, “to decide what in general we mean when we speak of a person’s character as distinct from his nature, his temperament, and his personality” (1966, p. 40). Many advocates of character education are vague on just this distinction, and it might be helpful to propose that character consists of traits that are learned, while personality and temperament consist of traits that are innate. [ 8 ]

What advocates are clear on, however, is that character is the essence of what we are. The term comes from the world of engraving, from the Greek term kharakter , an instrument used for making distinctive marks. Thus character is what marks a person or persons as distinctive.

Character is not just one attribute or trait. It signifies the sum total of particular traits, the “sum of mental and moral qualities” ( O.E.D. , p. 163). The addition of “moral qualities” to the definition may be insignificant, for character carries with it a connotation of “good” traits. Thus character traits are associated, if not synonymous, with virtues. So a good person and, in the context of liberal democracy, a good citizen will have these virtues.

To Thomas Lickona a virtue is “a reliable inner disposition to respond to situations in a morally good way” (p. 51); “good character,” he continues, “consists of knowing the good, desiring the good, and doing the good” (Idem). Who determines what the good is? In general, inculcated traits or virtues or dispositions are used “in following rules of conduct.” These are the rules that reinforce social conventions and social order (Peters, p. 40). So in this view social convention determines what “good” means.

This might be problematic. What occurs when the set of virtues of the good person clashes with the set of virtues of the good citizen? What is thought to be good in one context, even when approved by society, is not necessarily what is thought to be good in another. Should the only child of a deceased farmer stay at home to care for his ailing mother, or should he, like a good citizen, join the resistance to fight an occupying army?

What do we do when the requirements of civic education call into question the values or beliefs of what one takes to be the values of being a good person? In Mozert v. Hawkins County Board of Education just such a case occurred. Should the Mozerts and other fundamentalist Christian parents have the right to opt their children out of those classes that required their children to read selections that went against or undermined their faith? On the one hand, if they are permitted to opt out, then without those children present the class is denied the diversity of opinion on the reading selections that would be educative and a hallmark of democracy. On the other hand, if the children cannot opt out, then they are denied the right to follow their faith as they think necessary. [ 9 ]

We can see, therefore, why educating for character has never been straightforward. William Bennett pushes for the virtues of patriotism, loyalty, and national pride; Amy Gutmann wants to see toleration of difference and mutual respect. Can a pacifist in a time of war be a patriot? Is the rebel a hero or simply a troublemaker? [ 10 ] Can idealized character types speak to all of our students and to the variegated contexts in which they will find themselves?

Should our teachers teach a prescribed morality, often closely linked to certain religious ideas and ideals? Should they teach a content only of secular values related to democratic character? Or should they teach a form of values clarification in which children’s moral positions are identified but not criticized?

These two approaches—a prescribed moral content or values clarification—appear to form the two ends of a character education spectrum. At one end is the method of indoctrination of prescribed values and virtues, regardless of sacred or secular orientation. But here some citizens will express concern about just whose values are to be taught or, to some, imposed. [ 11 ] At the same time, some will see the inculcation of specified values and virtues as little more than teaching a “morality of compliance” (Nord, 2001, 144).

At the other end of the spectrum is values clarification, [ 12 ] but this seems to be a kind of moral relativism where everything goes because nothing can be ruled out. In values clarification there is no right or wrong value to hold. Indeed, teachers are supposed to be value neutral so as to avoid imposing values on their students and to avoid damaging students’ self-esteem. William Damon calls this approach “anything-goes constructivism” (1996), for such a position may leave the door open for students to approve racism, violence, and “might makes right.”

Is there a middle of the spectrum that would not impose values or simply clarify values? There is no middle path that can cut a swath through imposition on one side and clarification on the other. Perhaps the closest we can get is to offer something like Gutmann’s or Galston’s teaching of critical thinking. Here students can think about and think through what different moral situations require of persons. With fascists looking for hiding Jews, I lie; about my wife’s new dress, I tell the truth (well, usually). Even critical thinking, however, requires students to be critical about something. That is, we must presuppose the existence, if not prior inculcation, of some values about which to be critical.

What we have, then, is not a spectrum but a sequence, a developmental sequence. Character education, from this perspective, begins with the inculcation in students of specific values. But at a later date character education switches to teaching and using the skills of critical thinking on the very values that have been inculcated.

This approach is in keeping with what William Damon, an expert on innovative education and on intellectual and moral development, has observed: “The capacity for constructive criticism is an essential requirement for civic engagement in a democratic society; but in the course of intellectual development, this capacity must build upon a prior sympathetic understanding of that which is being criticized” (2001, 135).

The process, therefore, would consist of two phases, two developmental phases. Phase One is the indoctrination phase. Yet which values do we inculcate? Perhaps the easiest way to begin is to focus first on those behaviors that all students must possess. In fact, without first insisting that students “behave,” it seems problematic whether students could ever learn to think critically. Every school, in order to conduct the business of education, reinforces certain values and behaviors. Teachers demand that students sit in their seats; raise their hands before speaking; hand assignments in on time; display sportsmanship on the athletic field; be punctual when coming to class; do not cheat on their tests or homework; refrain from attacking one another on the playground, in the hallways, or in the classroom; be respectful of and polite to their elders (e.g., teachers, staff, administrators, parents, visitors, police); and the like. The teachers’ commands, demands, manner of interacting with the students, and own conformity to the regulations of the classroom and school establish an ethos of behavior—a way of conducting oneself within that institution. From the ethos come the requisite virtues—honesty, cooperation, civility, respect, and so on. [ 13 ]

Another set of values to inculcate at this early stage is that associated with democracy. Here the lessons are more didactic than behavioral. One point of civic education in a democracy is to raise free and equal citizens who appreciate that they have both rights and responsibilities. Students need to learn that they have freedoms, such as those found in Bill of Rights (press, assembly, worship, and the like) in the U. S. Constitution. But they also need to learn that they have responsibilities to their fellow citizens and to their country. This requires teaching students to obey the law; not to interfere with the rights of others; and to honor their country, its principles, and its values. Schools must teach those traits or virtues that conduce to democratic character: cooperation, honesty, toleration, and respect.

So we inculcate in our students the values and virtues that our society honors as those that constitute good citizenship and good character. But if we inculcate a love of justice, say, is it the justice found in our laws or an ideal justice that underlies all laws? Obviously, this question will not arise in the minds of most, if any, first graders. As students mature and develop cognitively, however, such questions will arise. So a high-school student studying American History might well ask whether the Jim Crow laws found in the South were just laws simply because they were the law. Or were they only just laws until they were discovered through argument to be unjust? Or were they always unjust because they did not live up to some ideal conception of justice?

Then we could introduce Phase Two of character education: education in judgment. Judgment is based on weighing and considering reasons and evidence for and against propositions. Judgment is a virtue that relies upon practical wisdom; it is established as a habit through practice. Judgment, or thoughtfulness, was the master virtue for Aristotle from whose exercise comes an appreciation for those other virtues: honesty, cooperation, toleration, and respect.

Because young children have difficulty taking up multiple perspectives, as developmental psychologists tell us, thinking and deliberating that require the consideration of multiple perspectives would seem unsuitable for elementary-school children. Additionally, young children are far more reliant on the teacher’s involvement in presenting problem situations in which the children’s knowledge and skills can be applied and developed. R. S. Peters offers an important consideration in this regard:

The cardinal function of the teacher, in the early stages, is to get the pupil on the inside of the form of thought or awareness with which he is concerned. At a later stage, when the pupil has built into his mind both the concepts and the mode of exploration involved, the difference between teacher and taught is obviously only one of degree. For both are participating in the shared experience of exploring a common world (1966, 53).

The distinction between those moving into “the inside” of reflective thinking and those already there may seem so vast as to be a difference of kind, not degree. But the difference is always one of degree. Elementary-school students have yet to develop the skills and knowledge, or have yet to gain the experience, to participate in phase- two procedures that require perspectivism.

In this two-phased civic education teachers inculcate specific virtues such as patriotism. But at a later stage this orientation toward solidifying a conventional perspective gives way to one of critical thinking. The virtue of patriotism shifts from an indoctrinated feeling of exaltation for the nation, whatever its actions and motives, to a need to examine the nation’s principles and practices to see whether those practices are in harmony with those principles. The first requires loyalty; the second, judgment. We teach the first through pledges, salutes, and oaths; we teach the second through critical inquiry.

Have we introduced a significant problem when we teach students to judge values, standards, and beliefs critically? Could this approach lead to students’ contempt for authority and tradition? Students need to see and hear that disagreement does not necessarily entail disrespect. Thoughtful, decent people can disagree. To teach students that those who disagree with us in a complicated situation like abortion or affirmative action are wrong or irresponsible or weak is to treat them unfairly. It also conveys the message that we think that we are infallible and have nothing to learn from what others have to say. Such positions undercut democracy.

Would all parents approve of such a two-phased civic education? Would they abide their children’s possible questioning of their families’ values and religious views? Yet the response to such parental concerns must be the same as that to any authority figure: Why do you think that you are always right? Aren’t there times when parents can see that it is better to lie, maybe even to their children, than to tell the truth? This, however, presupposes that parents, or authority figures, are themselves willing to exercise critical judgment on their own positions, values, and behaviors. This point underscores the need to involve other social institutions and persons in character education.

4. Modern Forms of Civic Education

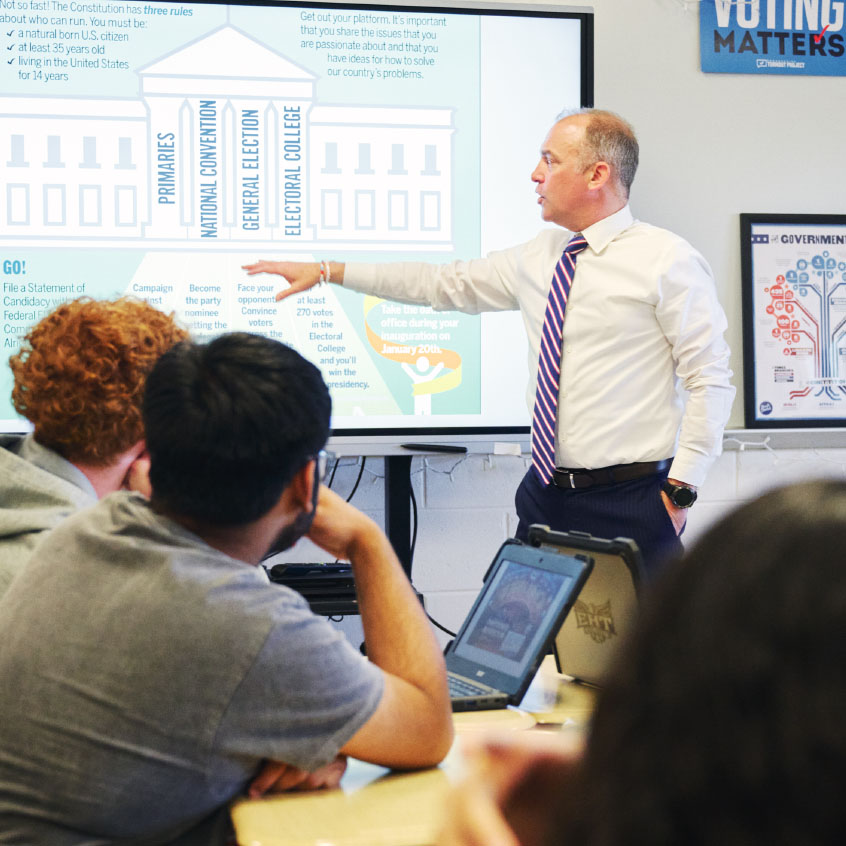

In the United States, most students are required to take courses on government or civics, and the main content is essentially political science for high school students. In other words, they use textbooks and other written materials to learn about the formal structure and behavior of political institutions, from local government to the United Nations (Godsay et al., 2012). The philosophical justifications for this kind of curriculum are rarely developed fully, but probably an underlying idea is that citizens ought to play certain concrete roles--voting, monitoring the news, serving on juries, petitioning the government--and to do so effectively requires a baseline understanding of the political system. Another implicit goal may be to increase young people’s appreciation of the existing constitutional system so that they will be motivated to preserve it.

Michael Rebell (2018) argues that both the United States Constitution and most states’ constitutional provisions regarding public education provide support for a right to adequate civic education . Specific policies should result from a deliberative process to define the educational opportunities that all students must receive and to select appropriate outcomes for civic education – all overseen by a court concerned with assessing whether civic education is constitutionally "adequate."

State standards are regulatory documents that affect the curriculum in public schools. All 50 states and the District of Columbia have adopted standards for civics as part of social studies (Godsay et al, 2012). The College, Career, and Civic Life ("C3") Framework for Social Studies State Standards (National Council for the Social Studies, 2013) provides a general framework for states to use as they design or revise these standards. It organizes civics – along with history, geography and economics – into one "Inquiry Arc" that extends from "Developing Questions and Planning Inquiries," to "Applying Disciplinary Concepts and Tools," to "Evaluating Sources and Evidence," to "Communicating Conclusions and Taking Informed Action." The Arc is presented as applicable from kindergarten through high school, but with increasingly demanding content. The logic of moving from question-generation to (ultimately) action suggests an implicit theory of civic engagement.

In the subsequent sections, we examine some proposals for alternative forms of civic education that are also philosophically interesting.

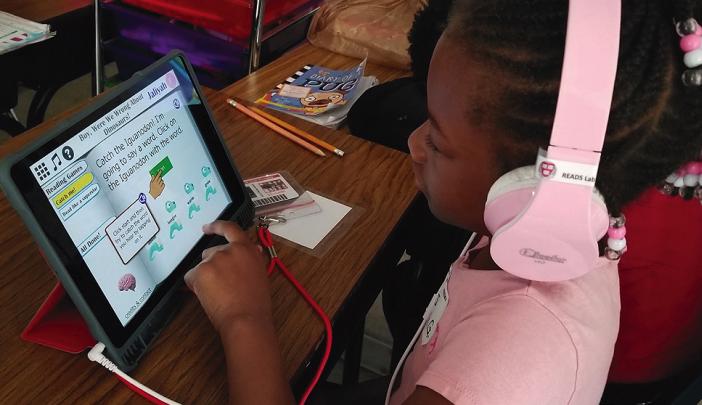

Putting students into the community-at-large is today called “service-learning.” It is a common form of civic education that integrates classroom instruction with work within the community. Ideally, the students take their experience and observations from service into their academic work, and use their academic research and discussions to inform their service.

Jerome Bruner, the renowned educator and psychologist, proposed that some classroom learning ought to be devoted to students creating political-action plans addressing significant social and political issues such as poverty or race. He also urged educators to get their students out into the local communities to explore the occupations, ways of life, and habits of residence. Bruner is here following Dewey, who criticized traditional education for its failure to get teachers and students out into the community to become intimately familiar with the physical, historical, occupational, and economic conditions that could then be used as educational resources (Dewey 1938, 40). Dewey warned of the “standing danger that the material of formal instruction will be merely the subject matter of the schools, isolated from the subject matter of life experience.” This could be countered by immersing students in “the spirit of service,” especially by learning about the various occupations within their communities (1916, 10–11, 49). [ 14 ]

Empirical evidence suggests that experiential education may be most effective for civic learning. “The reason, again, is that students respond to experiences that touch their emotions and senses of self in a firsthand way” (Damon, 2001, 141). Also, as Conover and Searing point out, “while most students identify themselves as citizens, their grasp of what it means to act as citizens is rudimentary and dominated by a focus on rights, thus creating a privately oriented, passive understanding” (2000, 108). To bring them out of this private and passive understanding, nothing is better, as Tocqueville noted, than political participation. The kind of participation here is political action, not simply voting or giving money. William Damon concludes that the most effective moral education programs “are those that engage students directly in action, with subsequent opportunities for reflection” (2001, 144).

Another influence on service-learning is the theory of social capital, described above. If a democracy depends on people serving one another and developing habits and networks of reciprocal concern--and if that kind of interaction is declining in a country like the United States--then it is natural to encourage or require students to serve as part of their learning.

Some critics (e.g., Boyte and Kari, 1996) worry that the “service” in “service-learning” reflects a narrow conception of citizenship that overlooks power and agency and that encourages an undemocratic distinction between the server and the served.

We can think of civic action as participation that involves far more than serving, voting, working or writing a letter to the editor. It can take many other forms: attending and participating in political meetings; organizing and running meetings, rallies, protests, fund drives; gathering signatures for bills, ballots, initiatives, recalls; serving on local elected and appointed boards; starting or participating in political clubs; deliberating with fellow citizens about social and political issues central to their lives; and pursuing careers that have public value.

The National Action Civics Collaborative (NACC) unites organizations that engage students in civic action as a form of civic learning. Service is usually only one form of “action.” Some NACC members work in schools, but similar practices are perhaps more common and easier to achieve in independent, community-based organizations. Youth Organizing is a widespread practice that engages adolescents in civic or political activities. Levinson (2012) offers a philosophically sophisticated defense of a pedagogy that she calls “guided experiential civic education” and argues for its place in public schools.

Especially if one’s theory of democracy is deliberative (see section 2.3, above ), the core of civic education may be learning to talk and listen with other people about public problems. That is a cognitively and ethically demanding activity that can be learned from experience. The most promising pedagogy is to discuss current events with a moderator--usually the teacher--and some requirement to prepare in advance.

Debates are competitive discussions. Simulations (such as mock trials or the Model UN) involve discussing issues from the perspective of fictional or historical characters. And deliberations usually involve students speaking in their own real voice and trying to find common ground.

Considerable evidence shows that moderated discussions of current, controversial issues increase students’ knowledge of civic processes, their skills at engaging with other people, and their interest in politics. See, e.g., Kawashima-Ginsberg and Levine (2014).