Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

Should College Athletes Be Paid? An Expert Debate Analysis

Extracurriculars

The argumentative essay is one of the most frequently assigned types of essays in both high school and college writing-based courses. Instructors often ask students to write argumentative essays over topics that have “real-world relevance.” The question, “Should college athletes be paid?” is one of these real-world relevant topics that can make a great essay subject!

In this article, we’ll give you all the tools you need to write a solid essay arguing why college athletes should be paid and why college athletes should not be paid. We'll provide:

- An explanation of the NCAA and what role it plays in the lives of student athletes

- A summary of the pro side of the argument that's in favor of college athletes being paid

- A summary of the con side of the argument that believes college athletes shouldn't be paid

- Five tips that will help you write an argumentative essay that answers the question "Should college athletes be paid?"

The NCAA is the organization that oversees and regulates collegiate athletics.

What Is the NCAA?

In order to understand the context surrounding the question, “Should student athletes be paid?”, you have to understand what the NCAA is and how it relates to student-athletes.

NCAA stands for the National Collegiate Athletic Association (but people usually just call it the “N-C-double-A”). The NCAA is a nonprofit organization that serves as the national governing body for collegiate athletics.

The NCAA specifically regulates collegiate student athletes at the organization’s 1,098 “member schools.” Student-athletes at these member schools are required to follow the rules set by the NCAA for their academic performance and progress while in college and playing sports. Additionally, the NCAA sets the rules for each of their recognized sports to ensure everyone is playing by the same rules. ( They also change these rules occasionally, which can be pretty controversial! )

The NCAA website states that the organization is “dedicated to the well-being and lifelong success of college athletes” and prioritizes their well-being in academics, on the field, and in life beyond college sports. That means the NCAA sets some pretty strict guidelines about what their athletes can and can't do. And of course, right now, college athletes can't be paid for playing their sport.

As it stands, NCAA athletes are allowed to receive scholarships that cover their college tuition and related school expenses. But historically, they haven't been allowed to receive additional compensation. That meant athletes couldn't receive direct payment for their participation in sports in any form, including endorsement deals, product sponsorships, or gifts.

Athletes who violated the NCAA’s rules about compensation could be suspended from participating in college sports or kicked out of their athletic program altogether.

The Problem: Should College Athletes Be Paid?

You know now that one of the most well-known functions of the NCAA is regulating and limiting the compensation that student-athletes are able to receive. While many people might not question this policy, the question of why college athletes should be paid or shouldn't be paid has actually been a hot-button topic for several years.

The fact that people keep asking the question, “Should student athletes be paid?” indicates that there’s some heat out there surrounding this topic. The issue is frequently debated on sports talk shows , in the news media , and on social media . Most recently, the topic re-emerged in public discourse in the U.S. because of legislation that was passed by the state of California in 2019.

In September 2019, California governor Gavin Newsom signed a law that allowed college athletes in California to strike endorsement deals. An endorsement deal allows athletes to be paid for endorsing a product, like wearing a specific brand of shoes or appearing in an advertisement for a product.

In other words, endorsement deals allow athletes to receive compensation from companies and organizations because of their athletic talent. That means Governor Newsom’s bill explicitly contradicts the NCAA’s rules and regulations for financial compensation for student-athletes at member schools.

But why would Governor Newsom go against the NCAA? Here’s why: the California governor believes that it's unethical for the NCAA to make money based on the unpaid labor of its athletes . And the NCAA definitely makes money: each year, the NCAA upwards of a billion dollars in revenue as a result of its student-athlete talent, but the organization bans those same athletes from earning any money for their talent themselves. With the new California law, athletes would be able to book sponsorships and use agents to earn money, if they choose to do so.

The NCAA’s initial response to California’s new law was to push back hard. But after more states introduced similar legislation , the NCAA changed its tune. In October 2019, the NCAA pledged to pass new regulations when the board voted unanimously to allow student athletes to receive compensation for use of their name, image, and likeness.

Simply put: student athletes can now get paid through endorsement deals.

In the midst of new state legislation and the NCAA’s response, the ongoing debate about paying college athletes has returned to the spotlight. Everyone from politicians, to sports analysts, to college students are arguing about it. There are strong opinions on both sides of the issue, so we’ll look at how some of those opinions can serve as key points in an argumentative essay.

Let's take a look at the arguments in favor of paying student athletes!

The Pros: Why College Athletes Should B e Paid

Since the argument about whether college athletes should be paid has gotten a lot of public attention, there are some lines of reasoning that are frequently called upon to support the claim that college athletes should be paid.

In this section, we'll look at the three biggest arguments in favor of why college athletes should be paid. We'll also give you some ideas on how you can support these arguments in an argumentative essay.

Argument 1: The Talent Should Receive Some of the Profits

This argument on why college athletes should be paid is probably the one people cite the most. It’s also the easiest one to support with facts and evidence.

Essentially, this argument states that the NCAA makes millions of dollars because people pay to watch college athletes compete, and it isn’t fair that the athletes don't get a share of the profits

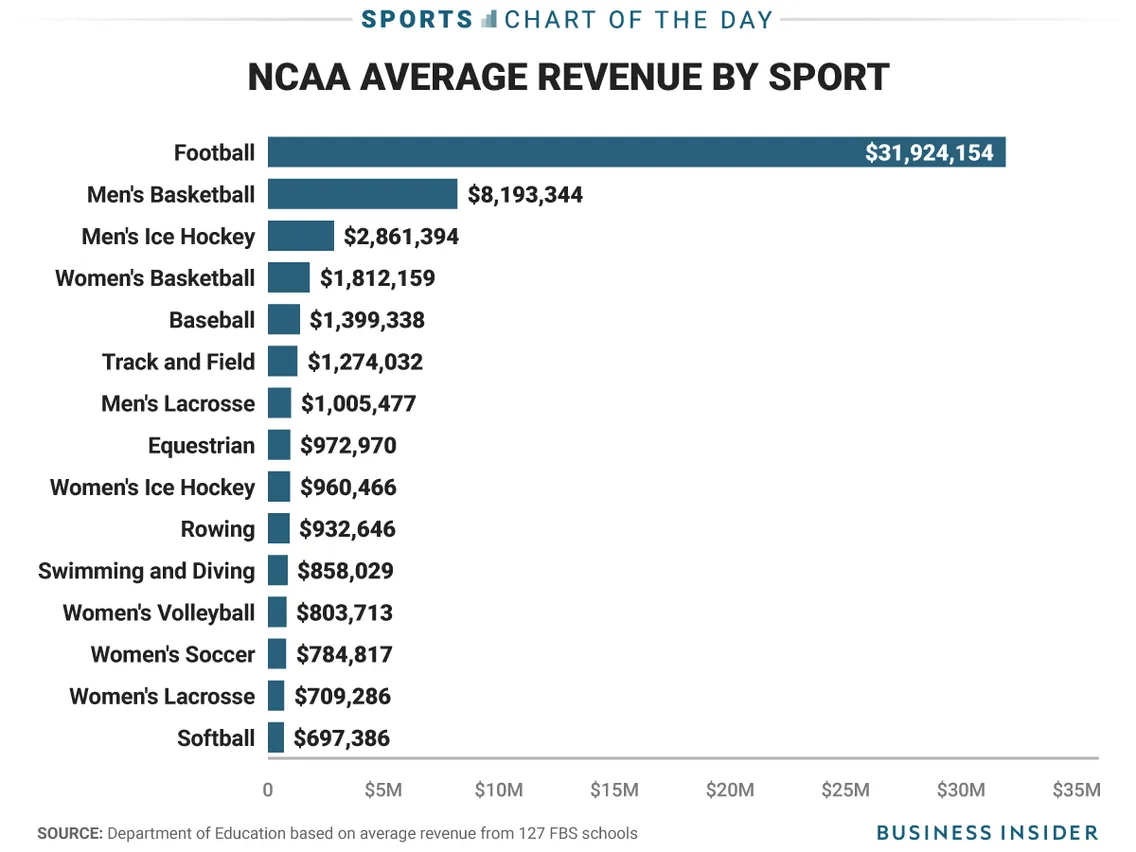

Without the student athletes, the NCAA wouldn’t earn over a billion dollars in annual revenue , and college and university athletic programs wouldn’t receive hundreds of thousands of dollars from the NCAA each year. In fact, without student athletes, the NCAA wouldn’t exist at all.

Because student athletes are the ones who generate all this revenue, people in favor of paying college athletes argue they deserve to receive some of it back. Otherwise, t he NCAA and other organizations (like media companies, colleges, and universities) are exploiting a bunch of talented young people for their own financial gain.

To support this argument in favor of paying college athletes, you should include specific data and revenue numbers that show how much money the NCAA makes (and what portion of that actually goes to student athletes). For example, they might point out the fact that the schools that make the most money in college sports only spend around 10% of their tens of millions in athletics revenue on scholarships for student-athletes. Analyzing the spending practices of the NCAA and its member institutions could serve as strong evidence to support this argument in a “why college athletes should be paid” essay.

I've you've ever been a college athlete, then you know how hard you have to train in order to compete. It can feel like a part-time job...which is why some people believe athletes should be paid for their work!

Argument 2: College Athletes Don’t Have Time to Work Other Jobs

People sometimes casually refer to being a student-athlete as a “full-time job.” For many student athletes, this is literally true. The demands on a student-athlete’s time are intense. Their days are often scheduled down to the minute, from early in the morning until late at night.

One thing there typically isn’t time for in a student-athlete’s schedule? Working an actual job.

Sports programs can imply that student-athletes should treat their sport like a full-time job as well. This can be problematic for many student-athletes, who may not have any financial resources to cover their education. (Not all NCAA athletes receive full, or even partial, scholarships!) While it may not be expressly forbidden for student-athletes to get a part-time job, the pressure to go all-in for your team while still maintaining your eligibility can be tremendous.

In addition to being a financial burden, the inability to work a real job as a student-athlete can have consequences for their professional future. Other college students get internships or other career-specific experience during college—opportunities that student-athletes rarely have time for. When they graduate, proponents of this stance argue, student-athletes are under-experienced and may face challenges with starting a career outside of the sports world.

Because of these factors, some argue that if people are going to refer to being a student-athlete as a “full-time job,” then student-athletes should be paid for doing that job.

To support an argument of this nature, you can offer real-life examples of a student-athlete’s daily or weekly schedule to show that student-athletes have to treat their sport as a full-time job. For instance, this Twitter thread includes a range of responses from real student-athletes to an NCAA video portraying a rose-colored interpretation of a day in the life of a student-athlete.

Presenting the Twitter thread as one form of evidence in an essay would provide effective support for the claim that college athletes should be paid as if their sport is a “full-time job.” You might also take this stance in order to claim that if student-athletes aren’t getting paid, we must adjust our demands on their time and behavior.

Argument 3: Only Some Student Athletes Should Be Paid

This take on the question, “Should student athletes be paid?” sits in the middle ground between the more extreme stances on the issue. There are those who argue that only the student athletes who are big money-makers for their university and the NCAA should be paid.

The reasoning behind this argument? That’s just how capitalism works. There are always going to be student-athletes who are more talented and who have more media-magnetizing personalities. They’re the ones who are going to be the face of athletic programs, who lead their teams to playoffs and conference victories, and who are approached for endorsement opportunities.

Additionally, some sports don't make money for their schools. Many of these sports fall under Title IX, which states that no one can be excluded from participation in a federally-funded program (including sports) because of their gender or sex. Unfortunately, many of these programs aren't popular with the public , which means they don't make the same revenue as high-dollar sports like football or basketball .

In this line of thinking, since there isn’t realistically enough revenue to pay every single college athlete in every single sport, the ones who generate the most revenue are the only ones who should get a piece of the pie.

To prove this point, you can look at revenue numbers as well. For instance, the womens' basketball team at the University of Louisville lost $3.8 million dollars in revenue during the 2017-2018 season. In fact, the team generated less money than they pay for their coaching staff. In instances like these, you might argue that it makes less sense to pay athletes than it might in other situations (like for University of Alabama football, which rakes in over $110 million dollars a year .)

There are many people who think it's a bad idea to pay college athletes, too. Let's take a look at the opposing arguments.

The Cons: Why College Athletes Shouldn't Be Paid

People also have some pretty strong opinions about why college athletes shouldn't be paid. These arguments can make for a pretty compelling essay, too!

In this section, we'll look at the three biggest arguments against paying college athletes. We'll also talk about how you can support each of these claims in an essay.

Argument 1: College Athletes Already Get Paid

On this side of the fence, the most common reason given for why college athletes should not be paid is that they already get paid: they receive free tuition and, in some cases, additional funding to cover their room, board, and miscellaneous educational expenses.

Proponents of this argument state that free tuition and covered educational expenses is compensation enough for student-athletes. While this money may not go straight into a college athlete's pocket, it's still a valuable resource . Considering most students graduate with nearly $30,000 in student loan debt , an athletic scholarship can have a huge impact when it comes to making college affordable .

Evidence for this argument might look at the financial support that student-athletes receive for their education, and compare those numbers to the financial support that non-athlete students receive for their schooling. You can also cite data that shows the real value of a college tuition at certain schools. For example, student athletes on scholarship at Duke may be "earning" over $200,000 over the course of their collegiate careers.

This argument works to highlight the ways in which student-athletes are compensated in financial and in non-financial ways during college , essentially arguing that the special treatment they often receive during college combined with their tuition-free ride is all the compensation they have earned.

Some people who are against paying athletes believe that compensating athletes will lead to amateur athletes being treated like professionals. Many believe this is unfair and will lead to more exploitation, not less.

Argument 2: Paying College Athletes Would Side-Step the Real Problem

Another argument against paying student athletes is that college sports are not professional sports , and treating student athletes like professionals exploits them and takes away the spirit of amateurism from college sports .

This stance may sound idealistic, but those who take this line of reasoning typically do so with the goal of protecting both student-athletes and the tradition of “amateurism” in college sports. This argument is built on the idea that the current system of college sports is problematic and needs to change, but that paying student-athletes is not the right solution.

Instead, this argument would claim that there is an even better way to fix the corrupt system of NCAA sports than just giving student-athletes a paycheck. To support such an argument, you might turn to the same evidence that’s cited in this NPR interview : the European model of supporting a true minor league system for most sports is effective, so the U.S. should implement a similar model.

In short: creating a minor league can ensure athletes who want a career in their sport get paid, while not putting the burden of paying all collegiate athletes on a university.

Creating and supporting a true professional minor league would allow the students who want to make money playing sports to do so. Universities could then confidently put earned revenue from sports back into the university, and student-athletes wouldn’t view their college sports as the best and only path to a career as a professional athlete. Those interested in playing professionally would be able to pursue this dream through the minor leagues instead, and student athletes could just be student athletes.

The goal of this argument is to sort of achieve a “best of both worlds” solution: with the development and support of a true minor league system, student-athletes would be able to focus on the foremost goal of getting an education, and those who want to get paid for their sport can do so through the minor league. Through this model, student-athletes’ pursuit of their education is protected, and college sports aren’t bogged down in ethical issues and logistical hang-ups.

Argument 3: It Would Be a Logistical Nightmare

This argument against paying student athletes takes a stance on the basis of logistics. Essentially, this argument states that while the current system is flawed, paying student athletes is just going to make the system worse. So until someone can prove that paying collegiate athletes will fix the system, it's better to maintain the status quo.

Formulating an argument around this perspective basically involves presenting the different proposals for how to go about paying college athletes, then poking holes in each proposed approach. Such an argument would probably culminate in stating that the challenges to implementing pay for college athletes are reason enough to abandon the idea altogether.

Here's what we mean. One popular proposed approach to paying college athletes is the notion of “pay-for-play.” In this scenario, all college athletes would receive the same weekly stipend to play their sport .

In this type of argument, you might explain the pay-for-play solution, then pose some questions toward the approach that expose its weaknesses, such as: Where would the money to pay athletes come from? How could you pay athletes who play certain sports, but not others? How would you avoid Title IX violations? Because there are no easy answers to these questions, you could argue that paying college athletes would just create more problems for the world of college sports to deal with.

Posing these difficult questions may persuade a reader that attempting to pay college athletes would cause too many issues and lead them to agree with the stance that college athletes should not be paid.

5 Tips for Writing About Paying College Athletes

If you’re assigned the prompt “Should college athletes be paid," don't panic. There are several steps you can take to write an amazing argumentative essay about the topic! We've broken our advice into five helpful tips that you can use to persuade your readers (and ace your assignment).

Tip 1: Plan Out a Logical Structure for Your Essay

In order to write a logical, well-organized argumentative essay, one of the first things you need to do is plan out a structure for your argument. Using a bare-bones argumentative outline for a “why college athletes should be paid” essay is a good place to start.

Check out our example of an argumentative essay outline for this topic below:

- The thesis statement must communicate the topic of the essay: Whether college athletes should be paid, and

- Convey a position on that topic: That college athletes should/ should not be paid, and

- State a couple of defendable, supportable reasons why college athletes should be paid (or vice versa).

- Support Point #1 with evidence

- Explain/interpret the evidence with your own, original commentary

- Support Point #2 with evidence

- Explain/interpret the evidence with your own, original commentary

- Support Point #3 with evidence

- New body paragraph addressing opposing viewpoints

- Concluding paragraph

This outline does a few things right. First, it makes sure you have a strong thesis statement. Second, it helps you break your argument down into main points (that support your thesis, of course). Lastly, it reminds you that you need to both include evidence and explain your evidence for each of your argumentative points.

While you can go off-book once you start drafting if you feel like you need to, having an outline to start with can help you visualize how many argumentative points you have, how much evidence you need, and where you should insert your own commentary throughout your essay.

Remember: the best argumentative essays are organized ones!

Tip 2: Create a Strong Thesis

T he most important part of the introduction to an argumentative essay claiming that college athletes should/should not be paid is the thesis statement. You can think of a thesis like a backbone: your thesis ties all of your essay parts together so your paper can stand on its own two feet!

So what does a good thesis look like? A solid thesis statement in this type of argumentative essay will convey your stance on the topic (“Should college athletes be paid?”) and present one or more supportable reasons why you’re making this argument.

With these goals in mind, here’s an example of a thesis statement that includes clear reasons that support the stance that college athletes should be paid:

Because the names, image, and talents of college athletes are used for massive financial gain, college athletes should be able to benefit from their athletic career in the same way that their universities do by getting endorsements.

Here's a thesis statement that takes the opposite stance--that college athletes shouldn’t be paid --and includes a reason supporting that stance:

In order to keep college athletics from becoming over-professionalized, compensation for college athletes should be restricted to covering college tuition and related educational expenses.

Both of these sample thesis statements make it clear that your essay is going to be dedicated to making an argument: either that college athletes should be paid, or that college athletes shouldn’t be paid. They both convey some reasons why you’re making this argument that can also be supported with evidence.

Your thesis statement gives your argumentative essay direction . Instead of ranting about why college athletes should/shouldn’t be paid in the remainder of your essay, you’ll find sources that help you explain the specific claim you made in your thesis statement. And a well-organized, adequately supported argument is the kind that readers will find persuasive!

Tip 3: Find Credible Sources That Support Your Thesis

In an argumentative essay, your commentary on the issue you’re arguing about is obviously going to be the most fun part to write. But great essays will cite outside sources and other facts to help substantiate their argumentative points. That's going to involve—you guessed it!—research.

For this particular topic, the issue of whether student athletes should be paid has been widely discussed in the news media (think The New York Times , NPR , or ESPN ).

For example, this data reported by the NCAA shows a breakdown of the gender and racial demographics of member-school administration, coaching staff, and student athletes. These are hard numbers that you could interpret and pair with the well-reasoned arguments of news media writers to support a particular point you’re making in your argument.

Though this may seem like a topic that wouldn’t generate much scholarly research, it’s worth a shot to check your library database for peer-reviewed studies of student athletes’ experiences in college to see if anything related to paying student athletes pops up. Scholarly research is the holy grail of evidence, so try to find relevant articles if you can.

Ultimately, if you can incorporate a mix of mainstream sources, quantitative or statistical evidence, and scholarly, peer-reviewed sources, you’ll be on-track to building an excellent argument in response to the question, “Should student athletes be paid?”

Having multiple argumentative points in your essay helps you support your thesis.

Tip 4: Develop and Support Multiple Points

We’ve reviewed how to write an intro and thesis statement addressing the issue of paying college athletes, so let’s talk next about the meat and potatoes of your argumentative essay: the body paragraphs.

The body paragraphs that are sandwiched between your intro paragraph and concluding paragraph are where you build and explain your argument. Generally speaking, each body paragraph should do the following:

- Start with a topic sentence that presents a point that supports your stance and that can be debated,

- Present summaries, paraphrases, or quotes from credible sources--evidence, in other words--that supports the point stated in the topic sentence, and

- Explain and interpret the evidence presented with your own, original commentary.

In an argumentative essay on why college athletes should be paid, for example, a body paragraph might look like this:

Thesis Statement : College athletes should not be paid because it would be a logistical nightmare for colleges and universities and ultimately cause negative consequences for college sports.

Body Paragraph #1: While the notion of paying college athletes is nice in theory, a major consequence of doing so would be the financial burden this decision would place on individual college sports programs. A recent study cited by the NCAA showed that only about 20 college athletic programs consistently operate in the black at the present time. If the NCAA allows student-athletes at all colleges and universities to be paid, the majority of athletic programs would not even have the funds to afford salaries for their players anyway. This would mean that the select few athletic programs that can afford to pay their athletes’ salaries would easily recruit the most talented players and, thus, have the tools to put together teams that destroy their competition. Though individual athletes would benefit from the NCAA allowing compensation for student-athletes, most athletic programs would suffer, and so would the spirit of healthy competition that college sports are known for.

If you read the example body paragraph above closely, you’ll notice that there’s a topic sentence that supports the claim made in the thesis statement. There’s also evidence given to support the claim made in the topic sentence--a recent study by the NCAA. Following the evidence, the writer interprets the evidence for the reader to show how it supports their opinion.

Following this topic sentence/evidence/explanation structure will help you construct a well-supported and developed argument that shows your readers that you’ve done your research and given your stance a lot of thought. And that's a key step in making sure you get an excellent grade on your essay!

Tip 5: Keep the Reader Thinking

The best argumentative essay conclusions reinterpret your thesis statement based on the evidence and explanations you provided throughout your essay. You would also make it clear why the argument about paying college athletes even matters in the first place.

There are several different approaches you can take to recap your argument and get your reader thinking in your conclusion paragraph. In addition to restating your topic and why it’s important, other effective ways to approach an argumentative essay conclusion could include one or more of the following:

While you don’t want to get too wordy in your conclusion or present new claims that you didn’t bring up in the body of your essay, you can write an effective conclusion and make all of the moves suggested in the bulleted list above.

Here’s an example conclusion for an argumentative essay on paying college athletes using approaches we just talked about:

Though it’s true that scholarships and financial aid are a form of compensation for college athletes, it’s also true that the current system of college sports places a lot of pressure on college athletes to behave like professional athletes in every way except getting paid. Future research should turn its attention to the various inequities within college sports and look at the long-term economic outcomes of these athletes. While college athletes aren't paid right now, that doesn’t necessarily mean that a paycheck is the best solution to the problem. To avoid the possibility of making the college athletics system even worse, people must consider the ramifications of paying college students and ensure that paying athletes doesn't create more harm than good.

This conclusion restates the argument of the essay (that college athletes shouldn't be paid and why), then uses the "Future Research" tactic to make the reader think more deeply about the topic.

If your conclusion sums up your thesis and keeps the reader thinking, you’ll make sure that your essay sticks in your readers' minds.

Should College Athletes Be Paid: Next Steps

Writing an argumentative essay can seem tough, but with a little expert guidance, you'll be well on your way to turning in a great paper . Our complete, expert guide to argumentative essays can give you the extra boost you need to ace your assignment!

Perhaps college athletics isn't your cup of tea. That's okay: there are tons of topics you can write about in an argumentative paper. We've compiled 113 amazing argumentative essay topics so that you're practically guaranteed to find an idea that resonates with you.

If you're not a super confident essay writer, it can be helpful to look at examples of what others have written. Our experts have broken down three real-life argumentative essays to show you what you should and shouldn't do in your own writing.

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Ashley Sufflé Robinson has a Ph.D. in 19th Century English Literature. As a content writer for PrepScholar, Ashley is passionate about giving college-bound students the in-depth information they need to get into the school of their dreams.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

- Political Psychology

- Political Science

- Public Opinion

Should College Athletes be Allowed to be Paid? A Public Opinion Analysis

- November 2020

- Sociology of Sport Journal

- The Ohio State University

- Ohio University

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Beth D. Solomon

- SOCIOL SPORT J

- Victoria T. Fields

- Kevin Wallsten

- Tatishe M. Nteta

- Lauren A. McCarthy

- Aaron Miller

- Elizabeth C. Cooksey

- Melinda R. Tarsi

- Ellen J. Staurowsky

- Aquasia A. Shaw

- Annie Olaloku-Teriba

- HARVARD LAW REV

- C.I. Harris

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Home ➔ Free Essay Examples ➔ Essay on Whether College Athletes Should be Paid (with a Sample)

Essay on Whether College Athletes Should be Paid (with a Sample)

Every job should be paid. Can we assume that being a high school athlete is a profession? Is it just a hobby or a way to become famous and earn a scholarship? Receiving financial aid from an educational institution is a good perspective as the tuition fees increase each year. That’s why all the proposals to pay college athletes have drawn diverging responses. During the last decade, both learners and their parents have been discussing the question of whether college athletes should be paid.

Among all, LeBron James, a famous athlete, supports the movement along with Chris Murphy, a well-known politician.

In the US, youth needs to make money while studying (as jobs for college students are abundant), and for many, doing sports is the only trade they have mastered, and many people think it’s essential that they can start getting paid for their endeavors. They spend an equal amount of time training compared to professional athletes. What’s the difference then? Many people even view college athletes as a separate group of employees with fixed schedules and think that is why they should be paid.

According to a study conducted by the Ohio State University in 2020, only a slight majority of US citizens (51%) supported the idea of paying college athletes. CNBC has also published an article in which 53% of students were in favor of compensating college athletes.

This topic is as relevant now as discussing role-modeling, school bullying , child obesity, gun control , and other issues regarding eating habits, drugs, racial minorities, and so on. That is why you, as a student, may eventually face a need to prepare an essay or a research paper covering the college athletes’ paying dilemma.

An essay is the most typical assignment in this case. First, decide on the type if it’s not given in the requirements.

- Definition — pick some relevant terms and define them using dictionaries or their own words.

- Descriptive — describe the process of becoming a successful high school or college football player.

- Compare and contrast — compare how school athletes are treated in various areas or contrast them with pro players.

- Cause and effect — discuss how organizations like The National Honor Society may reward or pay university athletes and why.

- Argumentative — argue why the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) should pay school athletes. Do you accept this standpoint, and what’s the fair market value?

- Persuasive — prove that college athletic teams will perform better if they are getting paid.

There are many types of essays you can write on college student-athletes. The topic is hot, so it is a perfect material to highlight in your papers if a teacher or professor does not assign a specific idea to report on or a research question to explore and answer.

Facts, Statistics, and Essay Ideas to Use

Successful football or tennis players earn millions of dollars. But did you know that sports college athletes invest about 40 hours a week in their training sessions as well as games and performances? They also help to improve the image and reputation of their educational establishments. Apart from performing within the walls of schools, young athletes spend plenty of time doing their utmost at the national championships as well.

In your essay, to explain the whole idea behind paying student-athletes as an extra to scholarships, operate with facts and statistics. In any debate, including those linked to the college sports industry, the parties should at least present credible and up-to-date evidence to prove their points of view. That doesn’t include dedicated research conducted by the writer, which is also preferable. Before we provide a free essay sample , we’ll give you examples of such evidence.

Supporting Arguments

According to Marc Edelman’s article on Forbes, an average Division I player of a junior football team in college devotes 43.3 hours per week to their team. An interesting nuance is that it is 3 hours more than the usual US working week. Hence, one might even say that college athletes are among the hardest working people in the United States!

Besides paying students, another question is how this group of learners can maintain good grades while having so little time left for studies. Another case related to this discussion is from Florida State football players. They all are still students, and the team reported that their guys have to miss the first day of spring classes because of the upcoming games and intensive training sessions.

Make sure to retrieve data from relevant sites like NCAA . For instance, a forecast probability of competing in college athletics. Anonymous blog articles and fan pages are not the best sources of credible facts and stats. But if NBC News claims that 89% of all athletes who enrolled in college in 2012 earned degrees, it is more believable. That also breaks the myth that college athletes lack intelligence and literacy.

Tyson Harnett has written an article for HuffPost , where he says that student-athletes don’t get a cent for breaking records or winning important games, even though they work hard and meet everyone’s expectations. Coaches, though, do receive some monetary bonuses for the success of their teams. Yes, they also impact the teams’ performance, but is that entirely fair?

Confuting Arguments

In 2013, NCAA conducted a public survey on whether college football and basketball players should be paid. It revealed that 69% of the public and 61% of sports fans are against paying extra money to these student-athletes, apart from covering their college-related expenses. There were other findings linked to this question — read the full article to see further analysis.

Another opinion against paying more money to college athletes is that they’d have to pay taxes. So if you replaced scholarships the players get with a simple wage, that would be less affordable for the universities. John Thelin discusses this issue in more detail in his article . He provides all the figures and explains why paying student-athletes isn’t the best idea.

One more counterargument revolves around college ethics—paying student-athletes runs counter it. Just getting on the college team is already an accomplishment. And only 7% of school athletes get to play in college, and only 2% of them play in a Division I school. You can read more about it in Dave Anderson’s article about ten reasons against paying student-athletes.

Anderson also argues that any payment in any form besides scholarship can turn what used to be a privilege into a business. Players might change schools if they see a more lucrative opportunity. That would inevitably lead to less “attractive” college programs being cut. As a result, thousands of students will never get a chance to get an education in that institution.

Is it fair that sports team members get scholarships, unlike other learners? The US educational system offers many ways to apply for and receive financial aid in the form of a scholarship. However, that typically depends on the desire and efforts of the students. Many people believe it’s unfair to pay college athletes because they already get more rewards and recognition than other teens. That is another point to cover in your essay about this topic.

Which Essay Topic to Choose?

For and against claims within this student-athletes matter are plenty. Examine all the opinions and take the direction you feel like agreeing with. And remember that your essay must represent your thoughts as well. If you merely compile several views of other people, you won’t get an A.

You may be asked to compose this type of paper for classes like English composition, culture studies, sports, gender studies, and even business-related courses. But how do you choose a topic? Think about something you want to debate about and have enough knowledge of. Here are some issues students can discuss in their essays about whether college athletes should be paid:

- A full-time job as a college sports team member.

- The requirements of professional leagues.

- Men’s basketball teams vs. women’s teams.

- College athletic teams as a billion-dollar industry.

- The role of the Collegiate Athletic Association.

- The issues student-athletes are usually dealing with.

- NCAA is a non-profit organization that can’t be involved in paying athletes.

- Student-players can’t be compared to professionals.

- California’s “ Fair Pay to Play Act ” and its effects.

- Should college athletes be paid based on skill segregation?

You can get a paid essay sample by using our exclusive discount below or use our free paper sample to get a better idea. Before reading it, spend a couple of minutes studying the examples of possible thesis statements below.

Examples of Thesis Statements

Another important thing to consider is the thesis statement . It’s a central argument of an essay that the author should support throughout the text to prove their point of view or offer an effective solution to the problem.

Start with the primary question: whether college athletes should be paid similarly to full- or part-time workers in the United States. Here’s how your thesis statement may look:

- “Paying college athletes is a good idea because they invest the same time and effort as most American workers.”

- “College universities generate plenty of money thanks to the performances of their sports teams and young athletes. That’s why these students should be paid like the players in professional sports.”

- “Having sports as a job is not the same as playing sports for fun. In my essay, I will explain why young people involved in high school or college sports teams should get fair financial compensation.”

- “College football is hard work that requires plenty of time and training. Therefore, high-school and college athletes have to sacrifice their study hours, and that’s why they should be treated differently.”

Now, view our free essay sample to find out more about college students involved in the sports industry and how to write about it.

College Athletes Should be Paid Essay Example

College sports programs have become multimillion-dollar entertainment businesses that make a lot of money for college institutions. The revenues generated from the programs continue to increase every year to the extent where colleges can fund every other sports program. Part of the reason colleges earn handsome profits from the programs is the participation of student-athletes. Most college sports programs derive their revenues from endorsement deals, ticket sales, jersey sales, and broadcasting deals. Paying college athletes for participating in sports programs is an issue that has been subject debates over the years.

College athletes often struggle to make ends meet despite being given full scholarships that cover accommodation, tuition, meals, and fees for the four years in college. However, additional costs associated with being a college athlete are not covered by the scholarships. As such, athletes have to foot those extra costs out of their own pockets, such as buying or renting suits for fundraisers or mandatory banquets (Sanderson & Siegfried, 2015). Many people would argue that it is a small price to pay compared to the full scholarship awarded to them. However, they should acknowledge that scholarships are the only means for most athletes to attend college because they come from underprivileged backgrounds. Therefore, their performance in sports and athletics becomes their only chance to attend college.

Paying college athletes will increase the competitiveness of various sports programs. Tiered payments given to professional players in sports like basketball motivate them to perform better. The hard work from professional athletes boosts their total wages from sponsorship deals and media events (Steckler, 2015). As such, paying college athletes will help them focus on their education and their game without worrying about where to get money to cater for their daily needs. It also helps to prevent athletes from underperforming on the field.

Vast revenues earned from college sports programs are not reinvested in the teams, especially assisting them in pursuing their professional and educational goals. Instead, the profits generated are shared between coaches, administrators, and athletic directors (Tucker et al., 2016). As such, the athletes should be paid because proceeds are allocated to misplaced programs that do not address their welfare or improve their schools.

Coaches, their assistants, and administrators of college sports programs get paid handsomely for their roles. Most NCAA coaches are paid more than $100,000 annually alongside their assistants and advisors who help them with the training workload. The earnings of coaches almost triple what professors and teachers get paid despite being expected to facilitate the academic success of the athletes. Colleges with massive sports programs pay their head coaches millions of dollars because the institutions expect to derive even more profits (Steckler, 2015). If colleges can spend millions of dollars on a coach, then they should compensate their athletes because money is available.

Paying college athletes will help them gain money management skills. If the students end up becoming professional athletes, the skills will help them manage the money they will earn. Also, small stipends to the athletes will teach them how to save, considering that it is an essential skill most young people lack.

Paying college athletes will increase competitiveness in athletics at the school level and help them gain essential money management skills. Colleges derive astronomical profits from sports programs, and it is only fair that they compensate the athletes because they are the most important stakeholders. Besides, coaches and administrators earn huge salaries and performance bonuses despite the small role they play in the success of college athletic programs, which is also unjust.

- Sanderson, A. R., & Siegfried, J. J. (2015). The case for paying college athletes. Journal of Economic Perspectives , 29 (1), 115-38.

- Steckler, A. (2015). Time to Pay College Athletes: Why the O’Bannon Decision Makes Pay-for-Play Ripe for Mediation. Cardozo J. Conflict Resol. , 17 , 1071.

- Tucker, K., Morgan, B. J., Kirk, O., Moore, K., Irving, D., Sizemore, D., & Emanuel, R. (2016). Perceptions of college student-athletes. Journal of Undergraduate Ethnic Minority Psychology , 2 , 27-33.

Was this article helpful?

Should College Athletes Be Paid? Essay Example, with Outline

Published by gudwriter on November 23, 2017 November 23, 2017

Here is an essay example on whether college athletes should be paid or not. We explore the pros and cons and conclude that college students have a right to be paid.

Elevate Your Writing with Our Free Writing Tools!

Did you know that we provide a free essay and speech generator, plagiarism checker, summarizer, paraphraser, and other writing tools for free?

If you find yourself struggling to complete your essay, don’t panic. We can help you complete your paper before the deadline through our homework help history . We help all students across the world excel in their academics.

Should College Athletes Be Paid Essay Outline

Introduction.

Thesis: College students should be paid given the nature and organization of college athletics.

Reasons Why College Athletes Should Be Paid

Paragraph 1:

Since college athletics programs are geared towards turning a profit at the end in terms of the revenue generated during the programs, it would only be fair to pay the athletes involved.

- Some of the revenues should be passed to the people who actually cause the fans to come to the pitch, the players.

- The NCCA should consider passing regulations that control the compensation made to coaches so that they do not get paid salaries that are unnecessarily high.

Paragraph 2:

Paying college athletes would also limit or even end corruption from such external influences as agents and boosters.

- Bribing players kills the spirit of whatever game they are involved because they would be playing to the tune of the bribe they receive.

- If they cannot get well compensated by their respective parent institutions, a player would be easily lured into corruption.

Paragraph 3:

Student athletes are subjected to huge workloads that only make it fair that they get paid.

- They are required to regularly attend physical therapy, weight trainings, team meetings, film sessions, and practice for the various sports they take part in.

- They are still required to attend all classes without fail and always post good grades

Reasons Why College Athletes Should Not Be Paid

Paragraph 4:

Paying college athletes would remove their competitive nature and the passion they have for the games they participate in.

- It would culminate into a situation where the only motive the athletes have for playing is money and not the sportsman drive of winning games and trophies.

- The hunger and passion usually shown in college sports would be traded for “lackadaisical plays and half-ass efforts that we sometime see from pros.”

Paragraph 5:

Paying college athletes would also lead to the erosion of the connection between athlete students and college values.

- College sports would be effectively reduced to a market where students who are yet to join college and are talented in sports are won over by the highest bidding institution.

- A student would join a college not for its values in academics and social values but because it offers the best compensation perks in sports.

Intercollegiate athletic competitions continue to grow and gain more prominence in the US. The NCAA and the institutions of higher learning involved continue to make high profits from college athletic programs. College athletes deserve being paid because without them, college sports would not be existent.

Crucial question to explore; describe how you have taken advantage of a significant educational opportunity .

Essay on “Should College Athletes Be Paid?”

College athletics is a prominent phenomenon in the United States of America and is controlled and regulated by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). The Association is non-profit and is in charge of organizing the athletic programs of many higher learning institutions including universities and colleges. From the programs, the Association reaps significant revenues which it distributes to the institutions involved in spite of it being a non-profit organization. Noteworthy, the participants in the athletic programs from which the revenues are accrued are college students. This scenario has led to the emergence of the question of whether or not college students deserve being paid for their participation. This paper argues that college athletes should be paid given the nature and organization of college athletics.

Since college athletics programs are geared towards turning a profit at the end in terms of the revenue generated during the programs, it would only be fair to pay the athletes involved. “A report by CNN’s Chris Isidore in March 2015 named the Louisville Cardinals as the NCAA’s most profitable college basketball team for the 2013-14 season…” (Benjamin, 2017). Additionally, the programs have attracted huge coaching salaries which continue rising, with a basketball coach getting as high as $7.1 million in salaries. So, would it not be prudent to pass some of these revenues to the people who actually cause the fans to come to the pitch, the players? The NCCA should consider passing regulations that control the compensation made to coaches so that they do not get paid salaries that are unnecessarily high. This would allow for some part of the revenue to be channeled to compensating the players and give more meaning to collegiate athletics.

Paying college athletes would also limit or even end corruption from such external influences as agents and boosters. “Over the years we have seen and heard scandals involving players taking money and even point-shaving” (Lemmons, 2017). Bribing players kills the spirit of whatever game they are involved in because they would be playing to the tune of the bribe they would have received. But again, if they cannot get well compensated by their respective parent institutions, a player would be easily lured into corruption. It should be noted that since it is some sort of business, an institution would do all within its reach to enable its college sports team(s) win matches and even trophies, including bribing players of opponent teams. The most effective way of curbing this practice is to entitle every player to a substantial compensation amount for their services to college athletics teams.

Perhaps you maybe interested in understanding some of the mistakes to avoid when crafting an MBA essay .

Further, student athletes are subjected to huge workloads that only make it fair that they get paid. They are required to regularly attend physical therapy, weight trainings, team meetings, film sessions, and practice for the various sports they take part in. On top of all that, they are still required to attend all classes without fail and always post good grades (Thacker, 2017). Is this not too much to ask for from somebody who gets nothing in terms of monetary compensation? Take a situation whereby an athlete gets out of practice at about 7 pm and has got a sit-in paper to take the following day. He or she is expected to study just as hard as every other student in spite of being understandably tired from the practice. It beats logic how a student in such a tight situation is expected to get all their work successfully done. It becomes even less sensible when it is considered that these students still have a social life to make time for (Thacker, 2017). Being paid for this hectic schedule may give them the motivation they need to keep going each day despite the toll the schedule takes on them.

Paying college athletes would remove their competitive nature and the passion they have for the games they participate in. It would culminate into a situation where the only motive the athletes have for playing is money and not the sportsman drive of winning games and trophies. As noted by Lemmons (2017), the hunger and passion usually shown in college sports would be traded for “lackadaisical plays and half-ass efforts that we sometime see from pros.” College sports would morph into full blown business ventures whereby the athletes are like employees and the colleges the employers. Participation in a sport would become more important for students than the actual contribution their participation makes to the sport. Moreover, students would want to take part not in sports in which they are richly talented but in sports that can guarantee better payment.

Paying college athletes would also lead to the erosion of the connection between athlete students and college values. “If a high-school football prodigy reported that he chose Michigan not for its academic quality, tradition, or beautiful campus but because it outbid all other suitors, a connection to the university’s values would be lost” (Yankah, 2015). College sports would be effectively reduced to a market where students who are yet to join college and are talented in sports are won over by the highest bidding institution. The implication is that a student would join a college not for its values in academics and social values but because it offers the best compensation perks in sports. It is clear here that the connection would purely be pegged on sports and payment. This will also turn colleges from grounds of molding future professionals to sports ventures.

Intercollegiate athletic competitions continue to grow and gain more prominence in the US. The NCAA and the institutions of higher learning involved continue to make high profits from college athletic programs. There are even coaches whose salaries for offering their services to college sports teams run into millions of dollars. Yet, those who work so hard so that this revenue can be realized are sidelined when it comes to payment. College athletes deserve being paid because without them, college sports would not be existent. It is thus less logical to continue engaging them while they do not enjoy the proceeds from their work.

Benjamin, J. (2017). “ Is it time to start paying college athletes? Tubby Smith and Gary Williams weigh in” . Forbes . Retrieved 21 November 2017, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/joshbenjamin/2017/04/04/is-it-time-to-start-paying-college-athletes/#72b48b3af71f

Lemmons, M. (2017). “ College athletes getting paid? Here are some pros and cons” . HuffPost . Retrieved 21 November 2017, from https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/college-athletes-getting-paid-here-are-some-pros-cons_us_58cfcee0e4b07112b6472f9a

Thacker, D. (2017). Amateurism vs. capitalism: a practical approach to paying college athletes. Seattle Journal for Social Justice , 16(1), 183-216.

Yankah, E. (2015). “ Why N.C.A.A. athletes shouldn’t be paid” . The New Yorker . Retrieved 21 November 2017, from https://www.newyorker.com/news/sporting-scene/why-ncaa-athletes-shouldnt-be-paid

Special offer! Get 20% discount on your first order. Promo code: SAVE20

Related Posts

Free essays and research papers, artificial intelligence argumentative essay – with outline.

Artificial Intelligence Argumentative Essay Outline In recent years, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become one of the rapidly developing fields and as its capabilities continue to expand, its potential impact on society has become a topic Read more…

Synthesis Essay Example – With Outline

The goal of a synthesis paper is to show that you can handle in-depth research, dissect complex ideas, and present the arguments. Most college or university students have a hard time writing a synthesis essay, Read more…

Examples of Spatial Order – With Outline

A spatial order is an organizational style that helps in the presentation of ideas or things as is in their locations. Most students struggle to understand the meaning of spatial order in writing and have Read more…

- Bachelor’s Degrees

- Master’s Degrees

- Doctorate Degrees

- Certificate Programs

- Nursing Degrees

- Cybersecurity

- Human Services

- Science & Mathematics

- Communication

- Liberal Arts

- Social Sciences

- Computer Science

- Admissions Overview

- Tuition and Financial Aid

- Incoming Freshman and Graduate Students

- Transfer Students

- Military Students

- International Students

- Early Access Program

- About Maryville

- Our Faculty

- Our Approach

- Our History

- Accreditation

- Tales of the Brave

- Student Support Overview

- Online Learning Tools

- Infographics

Home / Blog

Should College Athletes Be Paid? Reasons Why or Why Not

January 3, 2022

Tables of Contents

Why are college athletes not getting paid by their schools?

How do student athlete scholarships work, what are the pros and cons of compensation for college athletes, keeping education at the center of college sports.

Since its inception in 1906, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has governed intercollegiate sports and enforced a rule prohibiting college athletes to be paid. Football, basketball, and a handful of other college sports began to generate tremendous revenue for many schools in the mid-20th century, yet the NCAA continued to prohibit payments to athletes. The NCAA justified the restriction by claiming it was necessary to protect amateurism and distinguish “student athletes” from professionals.

The question of whether college athletes should be paid was answered in part by the Supreme Court’s June 21, 2021, ruling in National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Alston, et. al. The decision affirmed a lower court’s ruling that blocked the NCAA from enforcing its rules restricting the compensation that college athletes may receive.

- As a result of the NCAA v. Alston ruling, college athletes now have the right to profit from their name, image, and likeness (NIL) while retaining the right to participate in their sport at the college level. (The prohibition against schools paying athletes directly remains in effect.)

- Several states have passed laws that allow such compensation. Colleges and universities in those states must abide by these new laws when devising and implementing their own policies toward NIL compensation for college athletes.

Participating in sports benefits students in many ways: It helps them focus, provides motivation, builds resilience, and develops other skills that serve students in their careers and in their lives. The vast majority of college athletes will never become professional athletes and are happy to receive a full or partial scholarship that covers tuition and education expenses as their only compensation for playing sports.

Athletes playing Division I football, basketball, baseball, and other sports generate revenue for their schools and for third parties such as video game manufacturers and media companies. Many of these athletes believe it’s unfair for schools and businesses to profit from their hard work and talent without sharing the profits with them. They also point out that playing sports entails physical risk in addition to a considerable investment in time and effort.

This guide considers the reasons for and against paying college athletes, and the implications of recent court rulings and legislation on college athletes, their schools, their sports, and the role of the NCAA in the modern sports environment.

Back To Top

Discover a first-of-its-kind sport business management program

The online BS in Rawlings Sport Business Management from Maryville University will equip you with valuable skills in marketing, finance and public relations. No SAT or ACT scores required.

- Engage in a range of relevant course topics, from sports marketing to operations management.

- Gain real-world experience through professional internships.

The reasons why college athletes aren’t paid go back to the first organized sports competitions between colleges and universities in the late 19th century. Amateurism in college sports reflects the “ aristocratic amateurism ” of sports played in Europe at the time, even though most of the athletes at U.S. colleges had working-class backgrounds.

By the early 20th century, college football had gained a reputation for rowdiness and violence, much of which was attributed to the teams’ use of professional athletes. This led to the creation of the NCAA, which prohibited professionalism in college sports and enforced rules restricting compensation for college athletes. The rules are intended to preserve the amateurism of student participants. The NCAA justified the rules on two grounds:

- Fans would lose interest in the games if the players were professional athletes.

- Limiting compensation to capped scholarships ensures that college athletes remain part of the college community.

NCAA rules also prohibited college athletes from receiving payment to “ advertise, recommend, or promote ” any commercial product or service. Athletes were barred from participating in sports if they signed a contract to be represented by an agent as well. As a result of the NIL court decision, the NCAA will no longer enforce its rule relating to compensation for NIL activities and will allow athletes to sign contracts with agents.

Major college sports now generate billions in revenue for their schools each year

For decades, colleges and universities have operated under the assumption that scholarships are sufficient compensation for college athletes. Nearly all college sports cost more for the schools to operate than they generate in revenue for the institution, and scholarships are all that participants expect.

But while most sports don’t generate revenue, a handful, notably football and men’s and women’s basketball, stand out as significant exceptions to the rule:

- Many schools that field teams in the NCAA’s Division I football tier regularly earn tens of millions of dollars each year from the sport.

- The NCAA tournaments for men’s and women’s Division I basketball championships generated more than $1 billion in 2019 .

Many major colleges and universities generate a considerable amount of money from their athletic teams:

- The Power Five college sports conferences — the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), Big Ten, Big 12, Pac 12, and Southeastern Conference (SEC) — generated more than $2.9 billion in revenue from sports in fiscal 2020, according to federal tax records reported by USA Today .

- This figure represents an increase of $11 million from 2019, a total that was reduced because of restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- In the six years prior to 2020, the conferences recorded collective annual revenue increases averaging about $252 million.

What are name, image, likeness agreements for student athletes?

In recent years some college athletes at schools that field teams in the NCAA’s highest divisions have protested the restrictions placed on their ability to be compensated for third parties’ use of their name, image, and likeness. During the 2021 NCAA Division I basketball tournament known familiarly as March Madness, several players wore shirts bearing the hashtag “ #NotNCAAProperty ” to call attention to their objections.

Following the decision in NCAA v. Alston, the NCAA enacted a temporary policy allowing college athletes to enter into NIL agreements and other endorsements. The interim policy will be in place until federal legislation is enacted or new NCAA rules are created governing NIL contracts for college athletes.

- Student athletes are now able to sign endorsement deals, profit from their use of social media, and receive compensation for personal appearances and signing autographs.

- If they attend a school located in a state that has enacted NIL legislation, they are subject to any restrictions present in those state laws. As of mid-August 2021, 40 states had enacted laws governing NIL contracts for college athletes.

- If their school is in a state without such a law, the college or university will determine its own NIL policies, although the NCAA prohibits pay-for-play and improper recruiting inducements.

- Student athletes are allowed to sign with sports agents and enter into agreements with school boosters so long as the deals abide by state laws and school policies.

Within weeks of the NCAA policy change, premier college athletes began signing NIL agreements with the potential to earn them hundreds of thousands of dollars .

- Bryce Young, a sophomore quarterback for the University of Alabama, has nearly $1 million in endorsement deals.

- Quarterback Quinn Ewers decided to skip his last year of high school and enroll early at Ohio State University so he could make money from endorsements.

- A booster for the University of Miami pledged to pay each member of the school’s football team $500 for endorsing his business.

How will the change affect college athletes and their schools?

The repercussions of court decisions and state laws that allow college athletes to sign NIL agreements continue to be felt at campuses across the country, even though schools and athletes have received little guidance on how to manage the process.

- The top high school athletes in football, basketball, and other revenue-generating college sports will consider their potential for endorsement earnings while being recruited by various schools.

- The first NIL agreements highlight the disparity between what elite college athletes can expect to earn and what other athletes may realize. On one NIL platform, the average amount earned by Division I athletes was $471, yet one athlete made $210,000 in July alone.

- Most NIL deals at present are for small amounts, typically about $100 in free apparel, in exchange for endorsing a product on social media.

The presidents and other leaders of colleges and universities that field Division I sports have not yet responded to the changes in college athlete compensation other than to reiterate that they do not operate for-profit sports franchises. However, the NCAA requires that Division I sports programs be self-supporting, in contrast to sports programs at Division II and III institutions, which receive funding directly from their schools.

Many members of the Power 5 sports conferences have reported shortfalls in their operations, leading analysts to anticipate major structural reforms in the governing of college sports in the near future. The recent changes have also caused some people to believe the NCAA is no longer relevant or necessary.

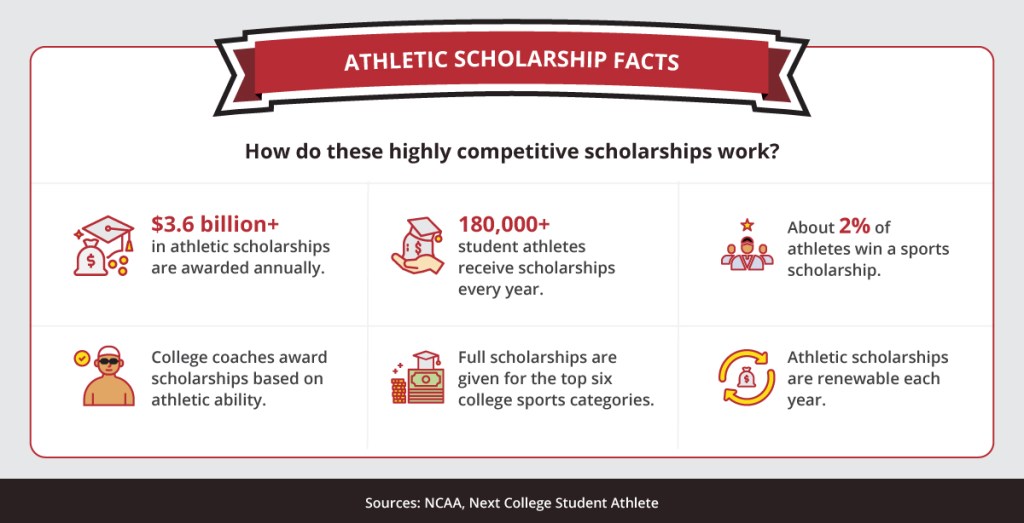

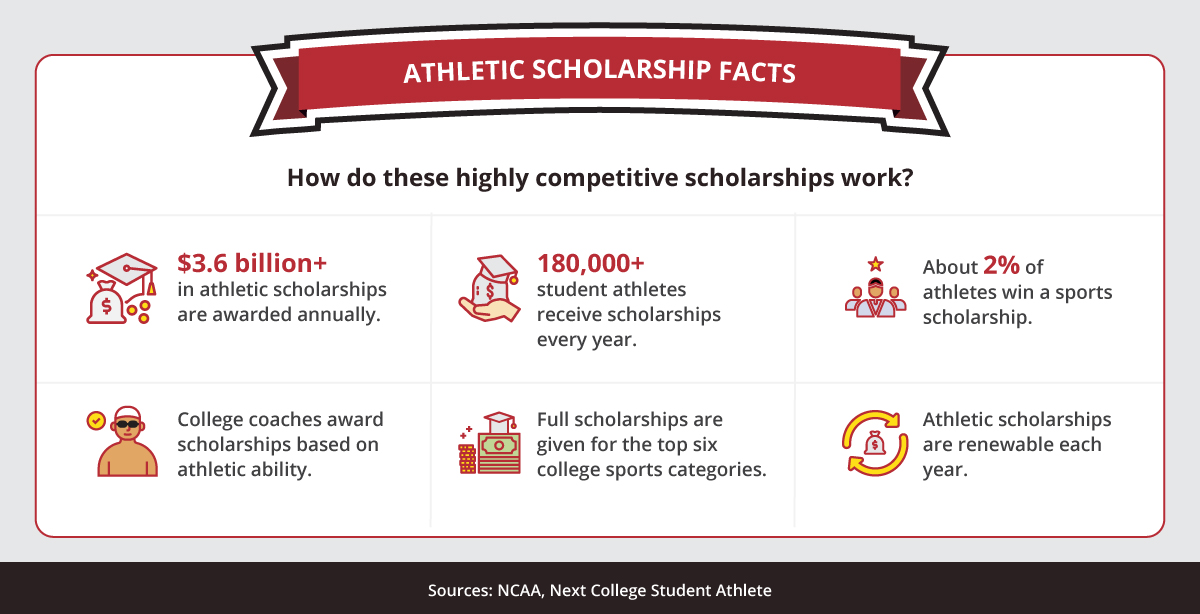

How do highly competitive athletic scholarships work? According to the NCAA and Next College Student Athlete: $3.6 billion+ in athletic scholarships are awarded annually, and 180,000+ student athletes receive scholarships every year. Additionally, about 2% of athletes win a sports scholarship; college coaches award scholarships based on athletic ability; full scholarships are given for the top six college sports categories; and athletic scholarships are renewable each year.

The primary financial compensation student athletes receive is a scholarship that pays all or part of their tuition and other college-related expenses. Other forms of financial assistance available to student athletes include grants, loans, and merit aid .

- Grants are also called “gift aid,” because students are not expected to pay them back (with some exceptions, such as failing to complete the course of study for which the grant was awarded). Grants are awarded based on a student’s financial need. The four types of grants awarded by the U.S. Department of Education are Federal Pell Grants , Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants , Iraq and Afghanistan Service Grants , and Teacher Education Assistance for College or Higher Education (TEACH) Grants .

- Loans are available to cover education expenses from government agencies and private banks. Students must pay the loans back over a specified period after graduating from or leaving school, including interest charges. EducationData.org estimates that as of 2020, the average amount of school-related debt owed by college graduates was $37,693.

- Merit aid is awarded based on the student’s academic, athletic, artistic, and other achievements. Athletic scholarships are a form of merit aid that typically cover one academic year at a time and are renewable each year, although some are awarded for up to four years.

Full athletic scholarships vs. partial scholarships

When most people think of a student athlete scholarship, they have in mind a full-ride scholarship that covers nearly all college-related expenses. However, most student athletes receive partial scholarships that may pay tuition but not college fees and living expenses, for example.

A student athlete scholarship is a nonguaranteed financial agreement between the school and the student. The NCAA refers to full-ride scholarships awarded to student athletes entering certain Division I sports programs as head count scholarships because they are awarded per athlete. Conversely, equivalency sports divide scholarships among multiple athletes, some of whom may receive a full scholarship and some a partial scholarship. Equivalency awards are divided among a team’s athletes at the discretion of the coaches, as long as they do not exceed the allowed scholarships for their sport.

These Division I sports distribute scholarships per head count:

- Men’s football

- Men’s basketball

- Women’s basketball

- Women’s volleyball

- Women’s gymnastics

- Women’s tennis

These are among the Division I equivalency sports for men:

- Track and field

- Cross-country

These are the Division I equivalency sports for women:

- Field hockey

All Division II and National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) sports programs distribute scholarships on an equivalency basis. Division III sports programs do not award sports scholarships, although other forms of financial aid are available to student athletes at these schools.

How college athletic scholarships are awarded

In most cases, the coaching staff of a team determines which students will receive scholarships after spending time scouting and recruiting. The NCAA imposes strict rules for recruiting student athletes and provides a guide to help students determine their eligibility to play college sports.

Once a student has received a scholarship offer from a college or university, the person may sign a national letter of intent (NLI), which is a voluntary, legally binding contract between an athlete and the school committing the student to enroll and play the designated sport for that school only. The school agrees to provide financial aid for one academic year as long as the student is admitted and eligible to receive the aid.

After the student signs an NLI, other schools are prohibited from recruiting them. Students who have signed an NLI may ask the school to release them from the commitment; if a student attends a school other than the one with which they have an NLI agreement, they lose one full year of eligibility and must complete a full academic year at the new school before they can compete in their sport.

Very few student athletes are awarded a full scholarship, and even a “full” scholarship may not pay for all of a student’s college and living expenses. The average Division I sports scholarship in the 2019-20 fiscal year was about $18,000, according to figures compiled by ScholarshipStats.com, although some private universities had average scholarship awards that were more than twice that amount. However, EducationData.org estimates that the average cost of one year of college in the U.S. is $35,720. They estimate the following costs by type of school.

- The average annual cost for an in-state student attending a public four-year college or university is $25,615.

- Average in-state tuition for one year is $9,580, and out-of-state tuition costs an average of $27,437.

- The average cost at a private university is $53,949 per academic year, about $37,200 of which is tuition and fees.

Student athlete scholarship resources

- College Finance, “Full-Ride vs. Partial-Ride Athletic Scholarships” — The college expenses covered by full athletic scholarships, how to qualify for partial athletic scholarships, and alternatives to scholarships for paying college expenses

- Student First Educational Consulting, “Athletic Scholarship Issues for 2021-2022 and Beyond” — A discussion of the decline in the number of college athletic scholarships as schools drop athletic programs, and changes to the rules for college athletes transferring to new schools

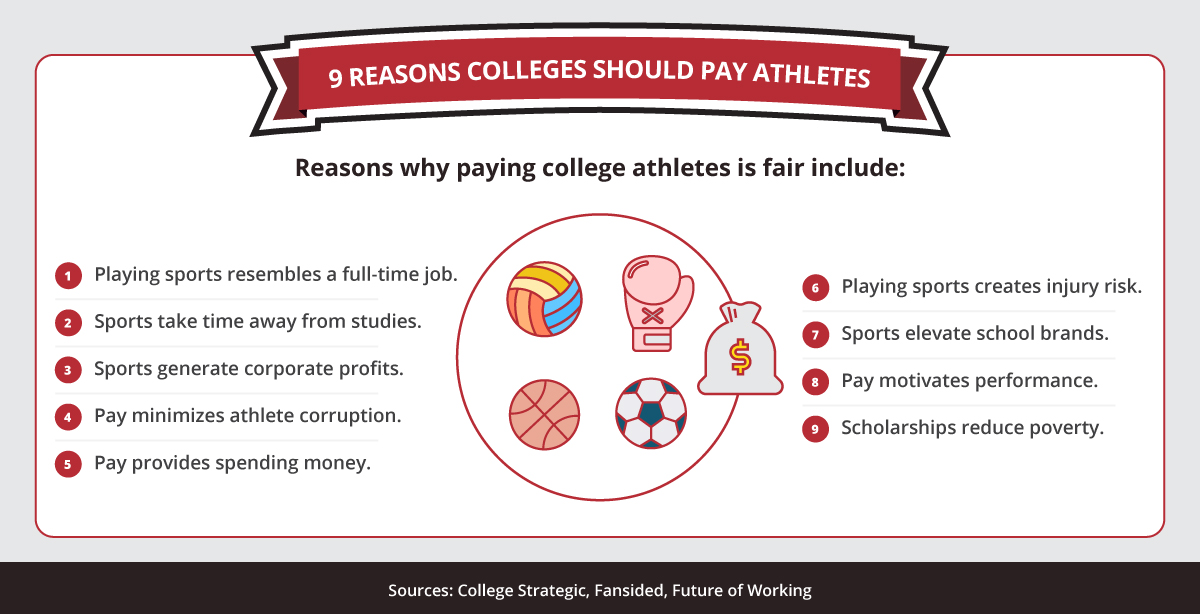

According to College Strategic, Fansided, and Future of Working, reasons why paying college athletes is fair include: 1. Playing sports resembles a full-time job. 2. Sports take time away from studies. 3. Sports generate corporate profits. 4. Pay minimizes athlete corruption. 5. Pay provides spending money. 6. Playing sports creates injury risk. 7. Sports elevate school brands. 8. Pay motivates performance. 9. Scholarships reduce poverty.

There are many reasons why student athletes should be paid, but there are also valid reasons why student athletes should not be paid in certain circumstances. The lifting of NCAA restrictions on NIL agreements for college athletes has altered the landscape of major college sports but will likely have little or no impact on the majority of student athletes, who will continue to compete as true amateurs.

Reasons why student athletes should be paid

The argument raised most often in favor of allowing college athletes to receive compensation is that colleges and universities profit from the sports they play but do not share the proceeds with the athletes who are the ultimate source of that profit.

- In 2017 (the most recent year for which figures are available), the NCAA recorded $1.07 billion in revenue. The organization’s president earned $2.7 million in 2018, and nine other NCAA executives had salaries greater than $500,000 that year.

- Elite college coaches earn millions of dollars a year in salary, topped by University of Alabama football coach Nick Saban’s $9.3 million annual salary.

- Many of the athletes at leading football and basketball programs are from low-income families, and the majority will not become professional athletes.

- College athletes take great physical risks to play their sports and put their future earning potential at risk. In school they may be directed toward nonchallenging courses, which denies them the education their fellow students receive.

Reasons why student athletes should not be paid

Opponents to paying college athletes rebut these arguments by pointing to the primary role of colleges and universities: to provide students with a rewarding educational experience that prepares them for their professional careers. These are among the reasons they give for not paying student athletes.

- Scholarships are the fairest form of compensation for student athletes considering the financial strain that college athletic departments are under. Most schools in Division I, II, and III spend more money on athletics than they receive in revenue from the sports.

- College athletes who receive scholarships are presented with an opportunity to earn a valuable education that will increase their earning power throughout their career outside of sports. A Gallup survey of NCAA athletes found that 70% graduate in four years or fewer , compared to 65% of all undergraduate students.