Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Causes and measures of poverty, inequality, and social exclusion: a review.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

2. literature review: poverty, inequality, and social exclusion.

‘It is the poor person, the “ aporos ”, who is an irritation, even to his own family. The poor relative is considered a source of shame it is best not to bring to light, while it is a pleasure to boast of a triumphant relation well situated in the academy, politics, art, or business. It is a phobia toward the poor that leads us to reject individuals, races, and ethnic groups that in general lack resources and that therefore cannot—or appear unable to—offer anything’. ( Cortina 2022 )

2.1. Poverty

2.1.1. monetary poverty, 2.1.2. multidimensional poverty, 2.2. inequality, 2.2.1. types of inequality.

‘The nation-state is still the right level at which to modernize any number of social and fiscal policies and to develop new forms of governance and shared ownership intermediate between public and private ownership, which is one of the major challenges for the century ahead. But only regional political integration can lead to effective regulation of the globalized patrimonial capitalism of the twenty-first century’. ( Piketty 2014 )

2.2.2. Measuring Inequality

2.3. is the middle class disappearing, 2.4. social exclusion: what is going on with aporophobia, 2.5. the sdgs overview, 3. discussion and future directions, 4. policy implications and conclusions.

- In order to diminish social exclusion and aporophobia, further utilization of poverty and inequality indices for the most needed target groups is necessary.

- Discrepancies between indicators provided by institutions (i.e., the World Bank and the UN) ought to be adjusted in order to have a unique poverty indicator.

- More focus on how to cover Maslow’s hierarchy of needs should be given from governments and international institutions, as it provides a framework for basic needs necessary for a decent life and is in tandem with the proposed indices of World Bank and the UN.

- The diversification of the SDGs not only in their targets, but also in their sub-targets, ought to be conducted.

- There is not a common rule on the acceptance and implementation of a specific poverty or inequality index: the application of two or more indices and their comparison might lead to better interpretation of the extent and depth of poverty or inequalities.

- It is also suggested that inequality measures should be further compared with polarization, as the former measures focus on the tails of a population distribution and the latter polarization index delves into the disappearance of the middle class.

Author Contributions

Informed consent statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

| 1 | ). |

| 2 | ( ) discussed the interlinkages of poverty with protracted conflict such as war. |

| 3 | ). |

| 4 | |

| 5 | ( ); ( ); ( ). |

| 6 | ). |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | ( ). |

| 10 | ( ). |

| 11 | ; ; ; ). |

| 12 | ). |

| 13 | ), Cowell also examined Pen’s parade in a well-rounded way with great explanations of its expansion into inequality literature ( , ). |

| 14 |

- Acemoglu, Daron, and James A. Robinson. 2013. Why Nations Fail? The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty . New York: Profile Bo. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alichi, Ali, Rodrigo Mariscal, and Daniela Muhaj. 2017. Hollowing Out: The Channels of Income Polarization in the United States . Working Papers. no. 17. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund (IMF). [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Alkire, Sabina, and James Foster. 2011. Counting and Multidimensional Poverty Measurement. Journal of Public Economics 95: 476–87. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Alkire, Sabina, Fanni Kovesdi, Elina Scheja, and Frank Vollmer. 2022. Moderate Multidimensional Poverty Index: Paving the Way Out of Poverty. Available online: https://ophi.org.uk/rp59a/ (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Alkire, Sabina, Usha Kanagaratman, and Nicolai Suppa. 2021. The Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) 2021 . Oxford: Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, University of Oxford. Available online: https://www.ophi.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/OPHI_MPI_MN_51_2021_4_2022.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Antoniades, Andreas, Indra Widiarto, and Alexander S. Antonarakis. 2020. Financial Crises and the Attainment of the SDGs: An Adjusted Multidimensional Poverty Approach. Sustainability Science 15: 1683–98. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Artuc, Erhan, Guillermo Falcone, Guido Port, and Bob Rijkers. 2022. War-Induced Food Price Inflation Imperils the Poor. In Global Economic Consequences of the War in Ukraine: Sanctions, Supply Chains and Sustainability . Edited by Luis Garicano, Dominic Rohner and Beatrice Weder di Mauro. London: CEPR, pp. 155–63. [ Google Scholar ]

- Atkinson, Anthony B. 1969. On the Measurement of Inequality. Journal of Economic Theory 2: 244–63. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Atkinson, Anthony B. 2019a. Chapter 2: What Do We Mean by Poverty? In Measuring Poverty around the World . Edited by John Micklewright and Andrea Brandolini. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, pp. 28–57. [ Google Scholar ]

- Atkinson, Anthony B. 2019b. Chapter 5: Global Poverty and the Sustainable Development Goals. In Measuring Poverty around the World . Edited by John Micklewright and Andrea Brandolini. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, pp. 146–65. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barbier, Edward B. 1987. The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development. Environmental Conservation 14: 101–10. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Berg, Andrew G., and Jonathan Ostry. 2011. Inequality and Unsustainable Growth: Two Sides of the Same Coin? International Monetary Fund (IMF) Economic Review 65: 792–815. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Birdsall, Nancy. 2007. Income Distribution: Effects on Growth and Development. Working Paper Number 118. Available online: www.cgdev.org (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Boulding, Kenneth E. 1975. The Pursuit of Equality. In National Bureau of Economic Research . Edited by James D. Smith. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, pp. 9–28. Available online: http://www.nber.org/books/smit75-1 (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Bourguignon, Francois, and Gary Fields. 1997. Discontinuous Losses from Poverty, Generalized Pa Measures, and Optimal Transfers to the Poor. Journal of Public Economics 63: 155–75. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Bourguignon, Francois, and Satya R. Chakravarty. 2003. The Measurement of Multidimensional Poverty. Journal of Economic Inequality 1: 25–49. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Bourguignon, Francois, and Satya R. Chakravarty. 2019. The Measurement of Multidimensional Poverty. In Poverty, Social Exclusion and Stochastic Dominance . Edited by Satya R. Chakravarty. Springer: Singapore, pp. 83–108. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Campagnolo, Lorenza, and Marinella Davide. 2019. Can the Paris Deal Boost SDGs Achievement? An Assessment of Climate Mitigation Co-Benefits or Side-Effects on Poverty and Inequality. World Development 122: 96–109. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Carter, Michael R., and Christopher B. Barrett. 2006. The Economics of Poverty Traps and Persistent Poverty: An Asset-Based Approach. The Journal of Development Studies ISSN 42: 178–99. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ceriani, Lidia, and Paolo Verme. 2012. The Origins of the Gini Index: Extracts from Variabilità e Mutabilità (1912) by Corrado Gini. Journal of Economic Inequality 10: 421–43. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Chancel, Lucas, Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, eds. 2022. World Inequality Report . New York: World Inequality Lab, United Nations Development Program. Available online: https://wir2022.wid.world (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Chancel, Lucas. 2022. Global Carbon Inequality over 1990–2019. Nature Sustainability 5: 931–38. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Clifford, Brendan, Andrew Wilson, and Patrick Harris. 2019. Homelessness, Health and the Policy Process: A Literature Review. Health Policy 123: 1125–32. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Cobham, Alex, and Andy Sumner. 2013. Is It All About the Tails? The Palma Measure of Income Inequality. Center for Global Development , 343. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Cobham, Alex, Lukas Schlogl, and Andy Sumner. 2016. Inequality and the Tails: The Palma Proposition and Ratio Revisited . New York: United Nations Department of Economic & Social Affairs (UNDESA), vol. 7, pp. 1–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Comim, Flavio, Mihály Tamás Borsi, and Octasiano Valerio Mendoza. 2020. The Multi-Dimensions of Aporophobia. MPRA, No. 35423: Paper No. 40041, Posted 17. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/103124/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Cortina, Adela. 2022. Aporophobia: Why We Reject the Poor Instead of Helping Them/Adela Cortina . Translated by Adrian Nathan West. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cowell, Frank A. 2000. Chapter 2: Measurement of Inequality of Incomes. In Handbook of Income Distribution . Edited by Anthony B. Atkinson and Francois Bourguignon. Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V., pp. 87–166. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/handbook/handbook-of-income-distribution/vol/1/suppl/C (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Cowell, Frank A. 2009. Measuring Inequality. LSE Perspectives in Economic Analysis . Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cowell, Frank A., and Kiyoshi Kuga. 1981. Inequality Measurement. An Axiomatic Approach. European Economic Review 15: 287–305. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- CSRI. 2022. Global Wealth Report 2022: Leading Perspectives to Navigate the Future ; Credit Suisse Research Institute. Available online: https://www.studocu.com/en-au/document/university-of-queensland/introductory-macroeconomics/global-wealth-report-2022-en/41480059 (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Davis, E. Philip, and Miguel Sanchez-Martinez. 2014. A Review of the Economic Theories of Poverty. National Institute of Economic and Social Research 435: 1–65. [ Google Scholar ]

- De Maio, Fernando G. 2007. Income Inequality Measures. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 61: 849–52. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Derndorfer, Judith, and Stefan Kranzinger. 2021. The Decline of the Middle Class: New Evidence for Europe. Journal of Economic Issues 55: 914–38. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dhahri, Sabrine, and Anis Omri. 2020. Foreign Capital towards SDGs 1 & 2—Ending Poverty and Hunger: The Role of Agricultural Production. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 53: 208–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Dickerson, Andy, and Gurleen Popli. 2014. Persistent Poverty and Children’s Cognitive Development: Evidence from the UK Millenium Cohort Study. Sheffield Economic Research Paper Series No. 2011023. Available online: https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/economics/research/serps (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Donaldson, David, and John A. Weymark. 1986. Properties of Fixed-Population Poverty Indices. International Economic Review 27: 667–88. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Eurostat. 2022. Mean and Median Income by Age and Sex. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/ILC_DI03__custom_4622063/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 30 December 2022).

- Firebaugh, Glenn. 2009. The New Geography of Global Income Inequality . Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Foster, James, and Anthony Shorrocks. 1991. Subgroup Consistent Poverty Indices. Econometrica 59: 687–709. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Foster, James, Joel Greer, and Erik Thorbecke. 1984. A Class of Decomposable Poverty Measures. Econometrica 52: 761–66. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Foster, James, Joel Greer, and Erik Thorbecke. 2010. The Foster-Greer-Thorbecke (FGT) Poverty Measures: 25 Years Later. Journal of Economic Inequality 8: 491–524. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Gini, Corrado. 1921. Measurement of Inequality of Incomes. The Economic Journal 31: 121. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Goodhand, Jonathan. 2003. Enduring Disorder and Persistent Poverty: A Review of the Linkages Between War and Chronic Poverty. World Development 31: 629–46. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ha, Jongrim, M. Ayhan Kose, and Franziska Ohnsorge. 2021. One-Stop Source: A Global Database of Inflation . Policy Research Working Paper 9737. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hagenaars, Aldi J. M., and Bernard M. S. van Praag. 1985. A Synthesis of Poverty Line Definitions. Review of Income and Wealth 31: 139–54. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Haider, L. Jamila, Wiebren J. Boonstra, Garry D. Peterson, and Maja Schlüter. 2018. Traps and Sustainable Development in Rural Areas: A Review. World Development 101: 311–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Harmon, Justin. 2021. The Right to Exist: Homelessness and the Paradox of Leisure. Leisure Studies 40: 31–41. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Harris, Abram L. 1939. Pure Capitalism and the Disappearance of the Middle Class. Race, Radicalism, and Reform 47: 328–56. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Harrison, Ann. 2006. Globalization and Poverty . NBER Working Paper Series 12347; Cambridge: NBER, vol. 13, Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w12347 (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Hastings, Catherine. 2021. Homelessness and Critical Realism: A Search for Richer Explanations. Housing Studies 36: 737–57. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Haughton, Jonathan, and Shahidur R. Khandker. 2009. Handbook on Poverty and Inequality . Washington, DC: The World Bank. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hellgren, Zenia, and Lorenzo Gabrielli. 2021. Racialization and Aporophobia: Intersecting Discriminations in the Experiences of Non-Western Migrants and Spanish Roma. Social Sciences 10: 163. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Heuveline, Patrick. 2022. Global and National Declines in Life Expectancy: An End-of-2021 Assessment. Population and Development Review 48: 31–50. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Hoover, Edgar M., Jr. 1936. All Use Subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE AMERICAN. The Review of Economics and Statistics 18: 162–71. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- IMF. 2014. Fiscal Policy and Income Inequality . Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2014/012314.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- INE. 2007. Poverty and Its Measurement: The Presentation of a Range of Methods to Obtain Measures of Poverty . Madrid: Instituto Nacional De Estadística. Available online: https://www.ine.es/buscar/searchResults.do?searchString=Poverty+and+its+measurement++The+presentation+of+a+range+of+methods++to+obtain+measures+of+poverty+&Menu_botonBuscador=&searchType=DEF_SEARCH&startat=0&L=1 (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Jenkins, Stephen P. 2022. Getting the Measure of Inequality . Available online: https://ifs.org.uk/inequality/getting-the-measure-of-inequality/ (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Kuznets, Simon. 1955. Economic Growth and Income Inequality. The American Economic Review 45: 1–28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lazonick, William. 2015. Labor in the Twenty-First Century: The Top 0.1% and the Disappearing Middle-Class . Working Paper No 4. New York: Institute for New Economic Thinking. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Lenoir, Rene. 1974. LES EXCLUS: Un Francais Sur Dix. Seuil , 1st ed. Available online: https://excerpts.numilog.com/books/9782021445206.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Levy, Frank, and J. Murnane Richard. 1992. U.S. Earning Levels and Earnings Inequality: A Review of Recent Trends and Proposed Explanations. Journal of Economic Literature 30: 1333–81. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lorenz, Max O. 1905. Methods of Measuring the Concentration of Wealth. American Statistical Associatio 9: 209–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lygnegård, Frida, Dana Donohue, Juan Bornman, Mats Granlund, and Karina Huus. 2013. A Systematic Review of Generic and Special Needs of Children with Disabilities Living in Poverty Settings in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Journal of Policy Practice 12: 296–315. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Lyubimov, Ivan. 2017. Income Inequality Revisited 60 Years Later: Piketty vs. Kuznets. Russian Journal of Economics 3: 42–53. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Maslow, Abraham Harold. 1943. A Theory of Human Motivation A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review 50: 370–96. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- OECD. 2016. OECD Factbook 2015–2016: Economic, Environmental and Social Statistics . Paris: OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/factbook-2015-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/factbook-2015-en (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- OECD. 2022. “Income Inequality”: Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/inequality/income-inequality.htm#indicator-chart (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- OWID. 2023. Top Income Shares. Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/income-inequality#within-country-inequality-around-the-world (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. 2018. Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2018: The Most Detailed Picture to Date of the World’s Poorest People . Oxford: University of Oxford. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Palma, José Gabriel. 2006. Globalizing Inequality: ‘Centrifugal’ and ‘Centripetal’ Forces at Work . DESA Working Paper 35. New York: UN DESA. [ Google Scholar ]

- Palma, José Gabriel. 2011. Homogeneous Middles vs. Heterogeneous Tails, and the End of the ‘Inverted-U’: The Share of the Rich Is What It’s All About . Cambridge: Cambridge Working Papers in Economics (CWPE), vol. 42, p. 1111. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Peet, Richard. 1975. Inequality and Poverty: A Marxist-Geographic Theory. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 65: 4. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Pen, Jan. 1973. A Parade of Dwarves (and a Few Giants). In Wealth, Income and Inequality . Edited by Anthony B. Atkinson. Middlesex: Penguin, pp. 73–82. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pietra, Gaetano. 2014. On the Relationships between Variability Indices (Note I) [Original: Pietra Gaetano (1915). Delle Relazioni Tra Gli Indici Di Variabilità (Nota I), Atti Del Reale Istituto Veneto Di Scienze, Lettere e Arti. 1915, Vol. LXXIV, Part I, Pages 775–792]. Metron 72: 5–16. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century . Cambridge and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ravallion, Martin, and Shaohua Chen. 1997. What Can New Survey Data Tell Us about Recent Changes in Distribution and Poverty? World Bank Economic Review 11: 357–82. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ravallion, Martin, and Shaohua Chen. 2001. Measuring Pro-Poor Growth. 2666. Available online: http://econ.worldbank.org (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Ravallion, Martin. 1996. Issues in Measuring and Modelling Poverty. The Economic Journal 106: 1328–43. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ravallion, Martin. 2018. Inequality and Globalization: A Review Essay. Journal of Economic Literature 56: 620–42. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Ravallion, Martin. 2020. On Measuring Global Poverty. Annual Review of Economics 12: 167–88. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Rawls, John. 1971. A Theory of Justice. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press . Revised ed. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rodríguez, Juan Gabriel. 2005. Measuring Polarization, Inequality, Welfare and Poverty. E2004/75. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/cea/doctra/e2004_75.html (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Schäfer, Armin, and Hanna Schwander. 2019. ‘Don’t Play If You Can’t Win’: Does Economic Inequality Undermine Political Equality? European Political Science Review 11: 395–413. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ Green Version ]

- Schutz, Robert R. 1951. On the Measurement of Income Inequality. The American Economic Review 41: 107–22. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sen, Amartya. 1976. An Ordinal Approach to Measurement. Econometrica 44: 219–31. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sen, Amartya. 1983. Poor, Relatively Speaking. Oxford Economic Papers 35: 153–69. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Shorrocks, Anthony F. 1995. Revisiting the Sen Poverty Index. Econometrica 63: 1225–30. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Smith, Adam. 1776. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations . London: Everyman Edition, Home University Library. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thon, Dominique. 1979. On Measuring Poverty. Review of Income and Wealth 25: 429–39. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Townsend, Peter. 1979. Poverty in the United Kingdom: A Survey of Household Resources and Standards of Living . Berkeley: University of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- UN. 2015. Inequality Measurement: Development Issues No. 2 . New York: United Nations. [ Google Scholar ]

- UN. 2016. The Sustainable Development Goals . New York: United Nations. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2016/the sustainable development goals report 2016.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- UNDP, and OPHI. 2020. Global MPI 2020–Charting Pathways Out of Multidimensional Poverty: Achieving the SDGs . New York: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Oxford: Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI). Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2020_mpi_report_en.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- UNDP, and OPHI. 2022. Poverty Multiidimensional Poverty Index 2022: Unpacking Deprivation Bundles to Reduce Multidimensional Poverty . New York: United Nations Development Programme. Oxford: Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/2022-global-multidimensional-poverty-index-mpi#/indicies/MPI (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- UNDP. 2019. Human Development Report 2019: Beyond Income, beyond Averages, beyond Today. United Nations Development Program . Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme. [ Google Scholar ]

- UNDP. 2022. Human Development Report 2021/2022: Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping Our Future in a Transforming World . Nairobi: United Nations Environment Programme. Available online: https://globalcompactrefugees.org/media/undp-report-humandevelopmentreport20212022overviewpdf (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- UNECE. 2017. Guide on Poverty Measurement . Geneva: United Nation Economic Commission for Europe, pp. 1–218. Available online: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/stats/publications/2018/ECECESSTAT20174.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- UNSDG. 2022. Operationalizing Leaving No One Behind . New York: United Nations Sustainable Development Group. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Walker, R. 2014. The Shame of Poverty . Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- WBG. 2018. Poverty and Shared Prosperty 2018: Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle . Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/poverty-and-shared-prosperity-2018 (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- WBG. 2020. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune . Washington, DC: World Bank Group. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- WBG. 2022a. Poverty and Inequality Platform (PIP) . Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online: https://pip.worldbank.org/home (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- WBG. 2022b. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2022: Correcting Course . Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/37739 (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- WCED. 1987. The Brundtland Report: ‘Our Common Future’ . New York: World Commission on Environment and Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Wolfson, Michael. 1994. When Inequalities Diverge. The American Economic Review 84: 353–58. [ Google Scholar ]

- Xu, Kuan. 1998. Statistical Inference for the Sen-Shorrocks-Thon Index of Poverty Intensity. Journal of Income Distribution 8: 143–52. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zheng, Buhong. 1993. An Axiomatic Characterization of the Watts Poverty Index. Economics Letters 42: 81–86. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zhou, Yang, and Yansui Liu. 2022. The Geography of Poverty: Review and Research Prospects. Journal of Rural Studies 93: 408–16. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

Click here to enlarge figure

| Index | Formulae |

|---|---|

| Poverty Headcount Ratio (P ) | |

| Poverty Gap | |

| Poverty Gap Index (P ) | |

| Poverty Severity Index (P ) | |

| Watts Index (W) |

| Countries | P | P | P | W |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 42.37% | 36.25% | 36.86% | 117.47% |

| Brazil | –68.15% | –72.11% | –74.41% | –75.78% |

| Canada | –0.73% | –17.11% | –30.78% | –21.66% |

| China | –98.98% | –99.18% | –99.06% | –99.26% |

| France | –75.78% | –72.24% | –72.21% | –82.60% |

| United Kingdom | 90.78% | 108.48% | 98.90% | 77.54% |

| India | –69.54% | –75.39% | –78.20% | –76.01% |

| Indonesia | –79.01% | –87.00% | –91.15% | –87.80% |

| Italy | 15.20% | 10.94% | 14.24% | 64.08% |

| Mexico | –31.39% | –38.78% | –40.33% | –42.41% |

| Russian Federation | –87.80% | –92.67% | –94.99% | –93.32% |

| Türkiye | –53.40% | –44.12% | –22.41% | –41.78% |

| United States | –0.06% | –10.15% | –12.20% | 177.40% |

| Multidimensional Poverty Measure (MPM) | Moderate Multidimensional Poverty Index (MMPI) | SDG | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dim. | Parameters | RW | Dim. | Indicator | A Household Is Deprived If: | RW | |

| Monetary Poverty | Daily consumption or income is less than USD 2.15 per person. | ||||||

| Education | At least one school-age child up to the (equivalent) age of trade 8 is not enrolled in school. | Education | Years of schooling | aged 10 years or older in the household has completed nine years of schooling. | |||

| No adult in the household (equivalent age of grade 9 or above has completed primary education. | School attendance | Any school-aged child is not attending school up to the age at which he/she would complete . | |||||

| Access to basic Infrastructure | The household lacks access to limited-standard drinking water. | Living standards | Drinking water | A household does not have access to . | |||

| The household lacks access to limited-standard sanitation. | Sanitation | A household does not have that is not shared with any other household. | |||||

| The household has no access to electricity. | Electricity | A household does not have electricity or does . | |||||

| Cooking fuel | A household cooks with dung, agricultural crops, shrubs, wood, charcoal, or coal. | ||||||

| Housing | A household has inadequate housing: . | ||||||

| Assets | A household does not own more than (radio, TV, telephone, computer, animal cart, bicycle, motorbike, refrigerator, ) and does not own a car or truck. | ||||||

| Health | Nutrition | Any person under 70 years of age, for whom there is nutritional information, is malnourished . | |||||

| Child Mortality | A child under 18 years of age has died in the family in the five-year period preceding the survey . | ||||||

| The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Share and Cite

Halkos, G.E.; Aslanidis, P.-S.C. Causes and Measures of Poverty, Inequality, and Social Exclusion: A Review. Economies 2023 , 11 , 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11040110

Halkos GE, Aslanidis P-SC. Causes and Measures of Poverty, Inequality, and Social Exclusion: A Review. Economies . 2023; 11(4):110. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11040110

Halkos, George E., and Panagiotis-Stavros C. Aslanidis. 2023. "Causes and Measures of Poverty, Inequality, and Social Exclusion: A Review" Economies 11, no. 4: 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11040110

Article Metrics

Article access statistics, further information, mdpi initiatives, follow mdpi.

Subscribe to receive issue release notifications and newsletters from MDPI journals

- DOI: 10.6007/ijarbss/v11-i15/10637

- Corpus ID: 241764759

Poverty: A Literature Review of the Concept, Measurements, Causes and the Way Forward

- Rusitha Wijekoon , M. Sabri , L. Paim

- Published in International Journal of… 22 July 2021

- Economics, Sociology

Tables from this paper

7 Citations

Are the traditional socio-economic causes of poverty still pertinent nowadays evidence from romania within the european union context, the mediating role technology adoption in the relationship between financial factors and economic well-being in agricultural context, understanding the path toward family economic well-being of coconut growers, mediating role of financial behavior between financial factors and economic well-being: through the lens of the extended family resource management model, the influence of financial knowledge, financial socialization, financial behaviour, and financial strain on young adults’ financial well-being, financial literacy, financial behavior, self-efficacy, and financial health among malaysian households: the mediating role of money attitudes, determinan kemiskinan di kabupaten parigi moutong, 45 references, measuring poverty in a multidimensional perspective: a review of literature, the extent of adequacies of poverty alleviation strategies: hong kong and china perspectives, the measurement of inequality and poverty: a policy maker's guide to the literature, basic needs: some issues, poor, relatively speaking, why don't we see poverty convergence, concept, measurement and causes of poverty: nigeria in perspective, the measurement of poverty, three ‘i’s of poverty curves, with an analysis of uk poverty trends, prospects for poverty reduction in asia and the pacific: progress, opportunities and challenges, especially in countries with special needs, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Multidimensional poverty: an analysis of definitions, measurement tools, applications and their evolution over time through a systematic review of the literature up to 2019

- Open access

- Published: 12 December 2023

- Volume 58 , pages 3171–3213, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ida D’Attoma ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2305-8454 1 &

- Mariagiulia Matteucci ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3404-6325 1

3051 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The paper provides an overview of definitions, measurements and applications of the concept of multidimensional poverty through a systematic review. The literature is classified according to three research questions: (1) what are the main definitions of multidimensional poverty?; (2) what methods are used to measure multidimensional poverty?; (3) what are the dimensions empirically measured?. Findings indicate that (1) the research on multidimensional poverty has grown in recent years; (2) multidimensional definitions do not necessarily imply to leave behind the dominance of the economic sphere; (3) the most popular methods proposed in the literature deal with the Alkire–Foster methodology, followed by latent variable models. Recommendations for future research emerge: new methodologies or the improvement of current ones are rather relevant; intangible aspects of poverty start to deserve attention calling for new definitions; there is evidence of under researched geographical areas, thereby calling for new empirical works that expand the geographical scope.

Similar content being viewed by others

Multidimensional Poverty Measures: Lessons from the Application of the MPI in Italy

The colombian multidimensional poverty index: measuring poverty in a public policy context.

Multidimensional Poverty: Conceptual and Measurement Issues

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The human capital is an essential resource for the growth of a country. Individuals or groups who are in poverty have to be helped to improve their conditions in order to experience a dignified life. With this in mind, poverty, its understanding, measuring, and reduction are at the center of socio-economic and political programs of governments in developing and non-developing countries. In particular, the way how it is measured determines the directions of governments’ lines of interventions. The other side of poverty is wealth. As reported in Peichl and Pestel ( 2013 , p. 4551) “the rich are an important source of both economic growth and inequality and have considerable economic and political power.” Therefore, in terms of design of public policies it becomes important not only who the poor are but also who the rich are.

We started our review from the belief, not new in the literature (see for example Petrillo 2018 ), that people well-being is far from being a unidimensional concept based only on the monetary aspects (i.e. income). Instead, other aspects of human life have to be included in order to enrich the idea of well-being.

As a matter of fact, the conceptualization of poverty ranges from income and/or consumption-based definitions to others that consider its multidimensional nature and its many manifestations: lack of productive resources to sustain livelihoods, limited or no access to basic services such as water, health and education, malnutrition, increased morbidity and mortality, living in an unsafe or insecure environment, poor or no housing, lack of participation in social, cultural and political life, social exclusion (Botchway 2013 ).

Originally, the literature on poverty has dwelt a great deal on the economic dimension as poverty manifestations and measurement were based on the GDP (at a national level) and on the poverty line.

Only recently, poverty has been increasingly conceptualized and measured from a multidimensional perspective in order to provide policy makers and the general public with the necessary tools for effectively monitoring social changes (Iglesias et al. 2017 ). For instance, policy makers who have often underestimated the need to define poverty multidimensionally (Kana Zeumo et al. 2011 ), started to consider it as a multidimensional concept. A number of factors made the multidimensional poverty concept appealing to them: (1) different measurements based on single indicators may produce different results (Lister 2004 ; Barnes et al. 2002 ) and the consideration of multidimensionality may prevent such a risk when policy makers evaluate policy impacts and targets to reduce poverty, (2) as income-based poverty and multidimensional poverty do not overlap, policies need to be addressed to different aspects of citizens’ lives, other than economic wellness.

However, such a relatively new conceptualization is still far from consolidation (Aaberge and Brandolini 2014 ). Furthermore, how many aspects of multidimensionality are jointly measured remains still an open debate.

Yet this growing literature is highly fragmented and to the authors’ knowledge no systematic review has been recently carried out on the concept of multidimensional poverty. It is acknowledged that a systematic literature review is considered the gold standard for evidence assessment and it is “the most efficient and high-quality method for identifying and evaluating extensive literature” (Mulrow 1994 ). It makes explicit the values and assumptions underpinning a review and enhances the legitimacy and authority of the resulting evidence (Tranfield et al. 2003 ). Systematic reviews use a rigorous method of study selection and data extraction and typically involve a detailed and comprehensive plan and search strategy derived a priori that reduce selection bias, which is very common in narrative reviews.

Using the systematic literature review (SLR) methodology, the aim of this paper is to identify the main definitions of poverty, to review how the concepts of “multidimensional poverty” and “multidimensional poverty measurement” have been developed, and which are the dimensions considered in empirical analysis, ultimately.

This specific objective leads to the achievement of a more general goal, which is to serve as a bibliometric reference for researchers who will need to deal with the topic of multidimensional poverty in the three areas investigated: definitions, methods, and empirical analysis.

Specifically, the method followed is the SLR procedure as transferred from medicine to business and economics research by Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ), employing specific criteria for inclusion and exclusion of articles in and from the review.

Through the SLR we aim at identifying the main definitions of poverty with special emphasis on different aspects encompassed in the definition, the methods proposed in the literature to study the multidimensional concept of poverty, and the dimensions included in the empirical applications.

A total of 229 articles were finally included. The key information related to these articles was stored in a data repository Footnote 1 specifically designed for recording their characteristics. After that, the main information has been summarized and discussed. The most relevant findings of the SLR can be outlined as follows. First, the analysis of the definitions of multidimensional poverty showed that only few studies proposed a new definition (10 studies out of 229). Also, most definitions included the income-based poverty as focus. Second, among the new methodological proposals, the relative majority of studies proposed modifications of the Alkire–Foster method (Alkire and Foster 2007 , 2009 , 2011a ) in terms of weighting schemes or methods of identification and aggregation of the dimensions. Only few studies (about 10%) proposed a comparison among different methodological approaches. Last, with reference to empirical applications, it emerged that not all the hypothesized dimensions are jointly considered and there was not observed a uniform geographical coverage of the continents. In this respect, a lack of studies related to USA emerged. Moreover, a certain preference for secondary data was observed with a predominant use of surveys that clearly show the extant need of producing internationally comparable “poverty” data with harmonized questionnaires by country and by year.

The main contribution of the paper is to bring together in one single research the most relevant studies about multidimensional poverty in order to find possible avenues for future research.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the methodology employed to conduct the systematic review; Sect. 3 describes the main characteristics of the studies included in the final data repository and provides the results from an in-depth review of the studies; Sect. 4 summarizes the main findings, discusses and concludes.

2 Methodology of the literature review

According to the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins and Green 2011 ; Higgins et al. 2020 ) “A systematic review attempts to collate all empirical evidence that fits pre‐specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific research question. It uses explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view to minimizing bias, thus providing more reliable findings from which conclusions can be drawn and decisions made”. The SLR here conducted follows three main stages—planning, executing, and reporting, as described in Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ). At the same time, we rely on the methodological guide summarized by Mohamed Shaffril et al. ( 2021 ), who have provided an all-encompassing and up-to-date guide to conducting systematic review for non-health researchers.

2.1 Planning

2.1.1 conceptual development and research questions.

Scholars and practitioners agree that one indicator alone cannot capture the multiple aspects of the poverty that is undisputedly considered a multidimensional concept (see Kana Zeumo et al. 2011 for a review).

According to the World Bank’s ( 2001 ) report, poverty is a state of deprivation which encompasses not only material but also non-material aspects. Furthermore, the concept of poverty is evolutive (Kana Zeumo et al. 2011 ) and its manifestations are related to the structures of the society and to the period in which poverty is discussed. Therefore, defining poverty is not a simple task as various studies do not agree on a common and conclusive definition.

With this in mind, we posit the following research question:

What are the main definitions of poverty and related concepts proposed in a multidimensional setting?

Poverty measurement is a crucial task. Indeed, only through its measurement authorities and policy makers are able to quantify its extent, intensity, and potential effect so as to gauge subsequent actions. We start from considering that the operationalization of a multidimensional poverty concept has to deal with different theoretical and methodological choices (see Dewilde 2004 ). Therefore, technically speaking, the problem becomes how to construct a multidimensional index. With this in mind, we posit the following research question:

What are the methods proposed to measure the multidimensional poverty concept?

Poverty can be declined with respect to several dimensions: income, human rights, food, education, health to cite the most common. However, in empirical contexts it may be difficult to effectively measure all the dimensions as assumed in conceptual frameworks. We expect that the literature review will reflect the fact that the notion of poverty has gradually been enlarged from an income-based to a multidimensional concept, and in the same fashion of Dewilde ( 2004 ), that the operationalization of the concept has not followed the same development. To put it differently, we might expect a mismatch between the dimensions conceptually developed and the number of dimensions empirically measured. In light of this view, we posit the following research question:

What are the dimensions measured in empirical works?

2.2 Executing

2.2.1 identification of studies and data collection, 2.2.1.1 selection of keywords.

We selected keywords that in our conceptual view were relevant for finding articles addressing the afore mentioned research questions and that were specific enough to avoid the inclusion of non-relevant publications and formulated in order to avoid the exclusion of potentially relevant and insightful works.

The chosen keywords, namely, ‘multidimensional inequality’, ‘multidimensional poverty’, ‘multidimensional well-being’, and ‘multidimensional wellbeing’, all refer to the broad concept of poverty. The concept of poverty from a stand-alone viewpoint (e.g., income-only poverty) was not considered. It is worth to note that in the selection of keywords, we did not differentiate among terms that describe methodology (e.g., ‘measures’, ‘indicators’) or terms addressing the type of investigation (e.g., ‘case study’, ‘empirical’, ‘theoretical’, ‘analysis’).

2.2.1.2 Selection of databases

Like in other studies (e.g., Dangelico and Vocalelli 2017 ; Vivas and Barge-Gil 2015 ) we chose the following databases for this research: (a) Elsevier Scopus and (b) Clarivate Analytics Web of Science (WoS). Descriptions of the search options are provided in Table 1 .

All databases were searched using the four abovementioned keywords. Table 2 reports the number of results obtained for each keyword within each database. Specifically, in the last two rows, the total numbers of retrieved studies within each database and across keywords (total, net of duplicates) are reported.

2.2.2 Selection of studies

Once the results of the searches reported in Table 2 were collected and the duplicated studies, within and across databases, were discharged, we obtained a list of 669 results that were archived in a Microsoft Excel file. In a SLR it is critical to operationally define which types of studies to include and exclude (Uman 2011 ). To this end, we decided to include studies that were clearly able to satisfy at least one of the three research questions (RQ1–RQ2–RQ3) reported in Sect. 2.1 . In particular, we included studies which provide a new definition of poverty in a multidimensional setting, propose a new method to study multidimensional poverty, or deal with a real-data application to support evidence on this topic. The exclusion criteria were defined as follows:

studies that did not strictly focus on the concept of multidimensional poverty as they did not propose a definition, a new method, or an application to real data on this topic;

studies that dealt with “multidimensional inequality” only from a mathematical point of view;

studies that dealt with economic or income aspects of poverty only, and therefore were not strictly considering a multidimensional concept;

studies that focused on well-being from a medical point of view only;

studies that did not focus on individuals or households, but, for example, on firms;

studies that dealt with specific categories of subjects only (e.g., patients, children, females, people with disabilities, aging population, workers, …) as the main focus of the systematic review is on households or individuals in general and not on specific categories of the population;

studies where multidimensional inequality was studied in relation to other aspects (e.g., mental health, gender) or as their determinant;

theoretical studies investigating the statistical and mathematical properties of inequality measures already proposed in the literature, as their focus was not on proposing a new definition, method or an application to real data;

studies that dealt with applications in a very limited geographical area (e.g. small rural areas of a specific region of a country, very small sample size);

studies whose abstract did not clear up the focus of the study;

studies where the dimensions considered were not clearly defined;

In this phase, it was important to balance sensitivity (retrieving a high proportion of relevant studies) with specificity (retrieving a low proportion of irrelevant studies). A total of 314 potentially relevant articles has been retrieved once the title and abstract were reviewed according to the above-mentioned inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.2.2.1 Study quality assessment

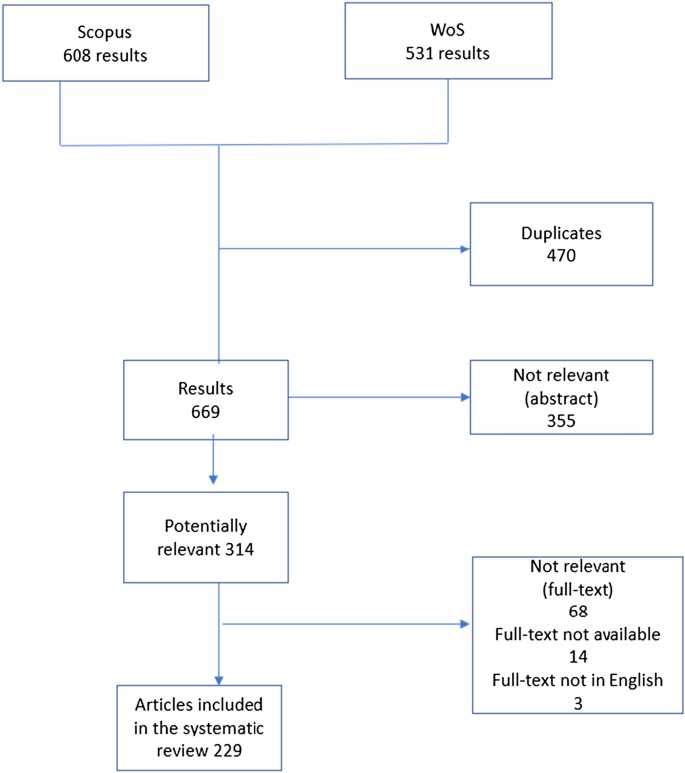

Once a comprehensive list of abstracts has been retrieved and reviewed, the 314 articles were fully analyzed and their quality was assessed. More precisely, as 14 full-text files were not available and 3 studies were written in Spanish or German, Footnote 2 a number of 297 studies were fully read. The final sample was reduced to a total of 229 articles (see a list of the studies in “ Appendix ”). The steps of the study selection process are reported in Fig. 1 .

Steps of the study selection process

As shown in Fig. 1 , we identified 608 records from Scopus and 531 from WoS, net of duplicates within each database. After removing duplicates, 669 abstracts were screened, which resulted in removing 355 records with not relevant abstract, leaving to 314 potentially relevant records to be screened by the lead authors. Of these 314 records, 68 not relevant, 14 with a not available full-text, and 3 not written in English articles were excluded, thus leaving a final sample of 229 studies to be included in the systematic review for data extraction.

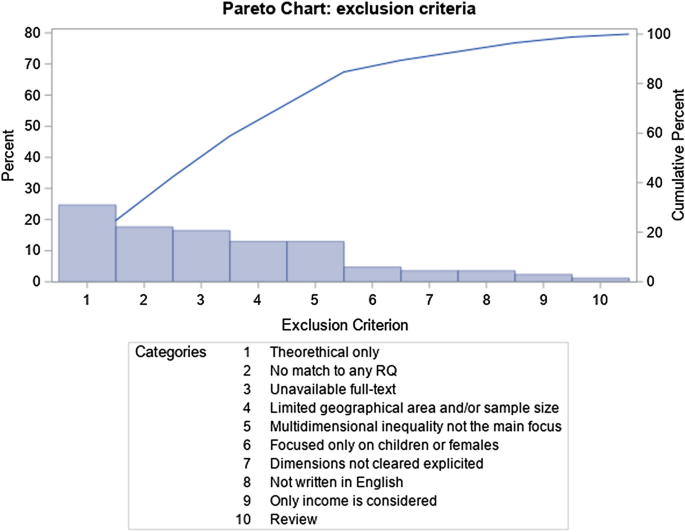

The reason to exclude some articles was that they did not match any of the specified inclusion criteria, but matched at least one of the exclusion criteria, although this was not clear from the abstracts. Among the exclusion criteria previously defined, the top motives for the exclusions were:

the study was theoretical only (21 records; 25%);

the study did not answer to any of the three research questions and therefore does not strictly focus on multidimensional poverty (15 records; 18%);

the full-text was not available (14 records; 16%).

the study investigated multidimensional inequality in relation to other aspects (e.g., mental health, gender) or as their determinant (11 records; 13%);

the geographical area or the sample size were very limited (11 records; 13%);

the study focused on females or children only (4 records; 5%);

the dimensions of poverty considered in the study were not made explicit (3 records; 4%);

the language was not English (3 records; 4%);

the only dimension considered was income (2 records; 2%);

the study was a review (1 record; 1%).

The Pareto chart (Fig. 2 ) reports the top motives of exclusions along with their cumulative frequencies.

Pareto Chart representing the main exclusion criteria

Apart from the fact that the study ‘only theoretical’ was the main exclusion criterion, the Pareto chart makes clear that ‘theoretical only’, ‘no match to any RQ’, ‘unavailable full-text’, ‘limited geographical area and/or sample size’ and ‘multidimensional inequality not the main focus’ together represent the 80% of the exclusion criteria.

2.2.2.2 Data extraction and data repository

Three types of information from each article were retrieved and stored in the data repository: (1) general information from the articles (authors, year, journal name, title, bibliographic database, keyword matching), (2) information about the matching with the three research questions (definition, method, application), and (3) information about the application, if any. For empirical applications, we reported the following details: methods of analysis, sample description (size, statistical units), geographical area (country or other), years covered, data collection type (cross sectional or longitudinal), data source (primary or secondary, source name), data representativeness (national, country comparisons), dimensions considered (economic/income, education, health, living standards, others), number and name of dimensions, number of indicators, main findings.

3 Reporting

3.1 characteristics of studies included in the review.

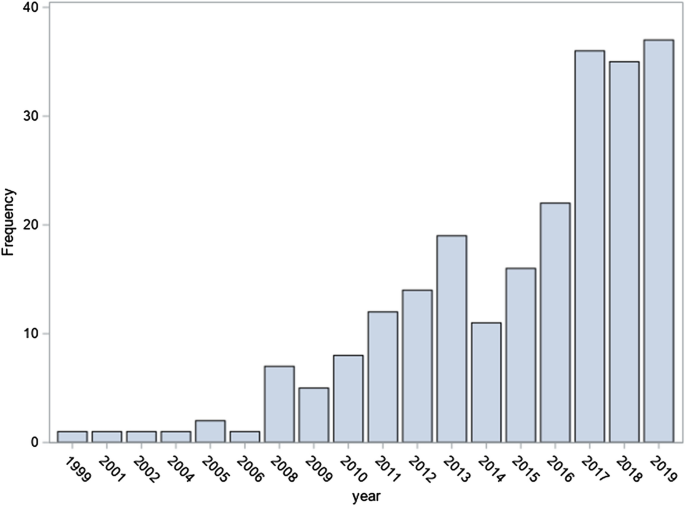

Figure 3 shows the distribution of studies over time and lead us to conclude that research associated with multidimensional poverty has grown in recent years. The year distribution of the sample is from 1999 to 2019. Over 60% of the sample is from studies published between 2015 and 2019.

Publications per year

The first study included in the review dates back to 1999. Until 2006 there has been a quite constant and limited number of studies, while after 2006 there has been an increase in the number of studies with a picking up speed starting from 2013 and a peak in 2019. Hence, most of the articles are recent, thus evidencing an increasing interest for poverty as a multi-dimensional concept in the literature.

Table 3 reports the name of the main journals where the reviewed studies were published. The journal that published most of the studies included in the review is “Social Indicator Research” (23% of studies), followed by “World Development” (4.8%) and by “The Journal of Economic Inequality” (4.4%). Interestingly, about 36% of the studies (82 out of 229) have been published in journals that host only one paper of this review. The journals publish work related to the economic, statistical, and social fields, mainly.

3.2 What is known about the multi-dimensional concept of poverty

Articles included in the review were classified into three different clusters (C1, C2, C3) according to the research questions they have addressed: (1) RQ1: what are the main definitions of poverty and related concepts in a multidimensional setting? (C1, 10 articles); (2) RQ2: what are the methods to measure the multidimensional poverty concept? (C2, 116 articles); and (3) RQ3: what are the relevant dimensions measured in empirical works? (C3, 214 articles). Table 4 reports the classification of the studies according to the three research questions. As can be noticed, the three clusters of studies examined were not mutually exclusive, as some of them (around 45%) addressed more than one research question. More in detail, as reported in Table 4 , 111 studies answer to RQ3 only, 94 studies involve both methods and applications to real data (i.e., they satisfy both RQ2 and RQ3), 14 studies satisfy RQ2 only, 7 studies satisfy all the RQs, 2 studies provide both a definition of multidimensional poverty and an empirical application (RQ1 and RQ3), and only 1 paper has been classified as proposing both a definition and a method (RQ1 and RQ2).

In “ Appendix ”, the full list of articles included in the review is reported.

In the following sections, the evidence coming from the studies belonging to the three clusters are described (Table 5 ).

3.2.1 What are the main definitions of poverty and related concepts in a multidimensional setting?

About 4% of the articles from the review were classified into C1 (10 articles). Out of the ten articles from C1, three defined the poverty as a multidimensional concept with a clear mention of the dimensions to be considered in addition to economic and monetary dimensions. Two articles considered more than one dimension, but still limited the definition to the economic and material spheres only (e.g., Annoni et al. 2015 ). The remaining definitions went beyond the material and economic spheres and included intangible or fuzzy dimensions like, for instance, ‘achievements’, ‘quality of life’, ‘living right’.

What emerged from the above definitions was that the consideration of more than one dimension did not necessarily imply to overcome the dominance of economic and material aspects in the conceptualization of poverty. Nevertheless, new dimensions belonging to the non-material sphere complemented the material ones.

3.2.2 What are the methods to measure the multidimensional poverty concept?

Among the selected studies, 116 have been classified in cluster C2 as they answer the RQ2 research question by discussing methods to measure the multidimensional poverty concept. These studies proposed a new method or an alternative version (or improvement) of an existing method to investigate the multidimensionality structure of poverty, inequality, or well-being from an original point of view.

Examining the methods, 105 articles have been classified as reporting a single method, 10 articles using two methods, and 1 article as reporting a comparison of three methods. Table 6 shows the list of studies and their classification, where the studies reporting more than one method are identified by a star (see the note to Table 6 ). The second column of Table 6 shows the 11 studies that explicitly mention the Sen’s capability approach (Sen 1985 ) as theoretical framework of reference in their research. According to this approach, multidimensional well-being should be understood in terms of peoples’ capabilities to achieve valuable functionings (beings and doings), emphasizing their freedom to choose and achieve well-being. As a matter of fact, this approach has been developed as an alternative approach to the traditional “welfarist” approach focusing on the utility only. The capability approach represents a general principle and therefore needs to be operationalized through a specific method.

As can be seen in Table 6 , the most frequently used methodology in the literature is the Alkire–Foster (AF) method (Alkire and Foster 2007 , 2009 , 2011a ) and its extensions, which have been employed in 34 studies overall (about 29% of all the studies). Among these, 30 studies use the AF method only while 4 studies report the use of different methods, besides the AF one. The AF method builds on the Foster-Greer-Thorbecke (FGT) poverty measures (Foster et al. 1984 ) with the aim of constructing a multidimensional index of poverty (MPI). By adopting a flexible approach, different dimensions of poverty are identified as different types of deprivations. The method is based on the counting approach as it counts the weighted number of dimensions in which people suffer deprivation by defining proper cut-offs.

The main innovations introduced by the studies using the AF method deal with the following issues: weighting schemes, methods of identification and aggregation of the dimensions. In fact, as reported in Mitra et al. ( 2013 ), “the Alkire Foster method is sensitive to the selection of dimensions and the methods used to derive rankings and weights”. In Datt ( 2019 ), alternative weighting schemes, methods of identification and aggregation are proposed, finding evidence that the contribution of different dimensions involved in the estimation of multidimensional poverty may vary depending not only on the weighting schemes, but also on the interaction between them and the choices made in terms of identification and aggregation of dimensions. A new strategy for deriving weighting schemes comes from Cavapozzi et al. ( 2015 ), who proposed a hybrid approach based on the hedonic regression, where value judgements about the dimensions are combined to statistical evidence. With respect to the identification of the dimensions, a modification of the MPI was proposed by Nowak and Scheicher ( 2017 ) to include individuals who are extremely poor in only few dimensions and the differences with the respect to the original formulation have been showed in an empirical setting. Alkire et al. ( 2017 ), followed by Nicholas et al. ( 2019 ), combined the classical counting approach of the AF method (Alkire and Foster 2011a ) for the analysis of multidimensional poverty at single time points, and the duration approach of Foster ( 2009 ) for over time analysis. In particular, Nicholas et al. ( 2019 ) showed that a large proportion of poverty may be attributed to over time deprivations. Finally, most studies propose modifications to the original formulation of the MPI based on the AF method by testing them in empirical settings (see, e.g., García-Pérez et al. 2017 ; Goli et al. 2019 ).

The second most commonly employed method is based on latent variables. Indeed, 15 articles (about 13%) have proposed latent variable models, such as factor analysis, or methods based on the concept of latent variables, such as principal component analysis or multiple correspondence analysis. In particular, one third of these studies use factor analysis, either in its confirmatory or exploratory version (see, e.g., Betti et al. 2015 ; Iglesias et al. 2017 ), one third use multiple correspondence analysis (see, e.g., Berenger et al. 2013 ), 4 of them use principal component analysis (see, e.g., Li et al. 2019 ) while, in the remaining study, latent class analysis based on discrete latent variables is proposed (Moonansingh et al. 2019 ). The aim of these studies has been to build a synthetic multidimensional measure of poverty or well-being, where each dimension is conceived as a latent, non-observable, construct. Particularly worthy of note is the fact that about half of the studies using latent variable models or methods are published in the journal “Social Indicators Research” (7 articles out of 15).

The third most frequently proposed method to study multidimensional poverty is the fuzzy theory (12 articles, 10%). Specifically, the fuzzy set theory is used to propose new weighting schemes for the poverty dimensions (see, e.g., Belhadj 2012 , 2013 ) and to overcome the classical notion of binary poverty (poor or not poor) by using fuzzy measures (Behlhadj and Limam 2012 ; Betti et al. 2015 ).

A total of 8 articles (6.9%) use the Gini index and its generalization to the multidimensional case for studying multidimensional poverty (see, e.g. Banerjee 2010 ). In this field of literature, the Gini coefficient is used to measure the extent of inequality.

Moreover, the stochastic dominance and partial order theory have been proposed in 6 studies (about 5%) for synthetizing multidimensional data as opposed to the classical approaches based on composite indicators, such as the AF method or factor analysis. In particular, the posetic (partially ordered set) approach has been proposed in this field to deal with the issues of weighting and aggregating for ordinal data (Iglesias et al. 2017 ) by following the proposal of Fattore ( 2016 ) and Fattore et al. ( 2012 ). Interestingly, the studies by Fattore ( 2016 ) and Fattore et al. ( 2012 ) have not been included in the list of studies of our systematic review, despite they developed the initial proposal based on the posetic approach. Specifically, Fattore ( 2016 ) has not been included due to the choice of the research keys, which omitted the word “deprivation” while Fattore et al. ( 2012 ) is not a journal article.

In addition, a number of 4 studies (3.4%) use generalized mean aggregation as method for building multidimensional measures of well-being or poverty (see, e.g., Pinar 2019 ).

The 49 remaining studies (about 42%) use different methods from the ones reviewed above (“other”). The “other” category contains less common methods that are used in less than 4 studies. Among these methods, we find clustering (Kana Zeumo et al. 2014 ), structural equations and causal theory (Rodero-Cosano et al. 2014 ), spatial Bayesian models (Greco et al. 2019 ), and axiomatic approaches (Decanq et al. 2009 ; Croci Angelini and Michelangeli 2012 ).

To sum up, about half of the studies included in this SLR (116 out of 229) have been classified as proposing a method to synthetize multidimensional poverty or well-being. This means that introducing a new methodological approach or improving current approaches used in the literature is rather relevant in this research field. Despite the AF method is predominant, a number of different and minor approaches have been proposed which borrow from different research fields. Another interesting aspect that clearly emerges from the findings of this review is that most studies (about 90%) include an empirical application to show the effectiveness of the proposed method in practice. The presence of empirical results enriches the study of multidimensional poverty and well-being with data-based socio-economic interpretations. Finally, another finding is that most studies use a single methodological approach to analyze poverty data. Comparisons among different methods are rather uncommon and involve about 10% of the studies only.

3.2.3 What are the dimensions measured in empirical works?

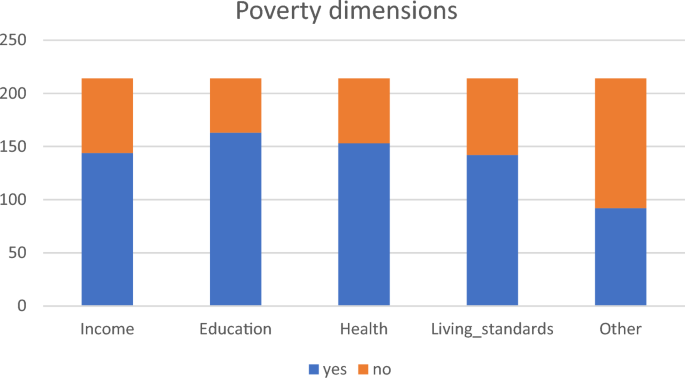

A total of 214 articles (93.45% of the sample) were classified as C3. Footnote 3 The dimensions of poverty considered in the studies reviewed are reported in Fig. 4 . The first most frequently dimension considered was ‘education’, followed by the second most frequently dimensions ‘health’ and ‘income’.

Poverty dimensions considered in the studies reviewed

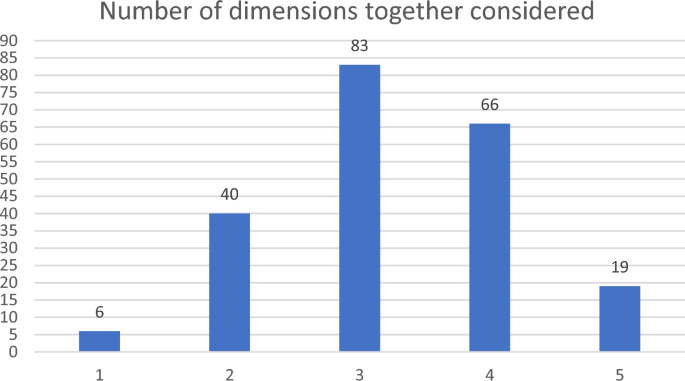

The dimensions reported in Fig. 4 are not mutually exclusive. This becomes clearer from Fig. 5 that reports the number of dimensions together considered in the studies reviewed. Only 6 studies out of 214 focused on a single dimension of poverty. The fact that they were included as considering poverty multidimensionally depends on the number of sub-items considered to measure the single dimension or in the case of the dimension ‘other’. In fact, under that category there may fall more than one dimension, such as ‘life satisfaction’, ‘civic engagement’, ‘women empowerment’, to cite a few. Moreover, 83 articles (around 39%) considered three dimensions and only around 9% considered all dimensions. Focusing on articles that considered three dimensions, we observed that the most frequent combination of poverty dimensions was “Education, Health, Living Standards” (37 studies out of 83, about 44.5%) followed by the combination “Income, Education, Health” (15 studies out of 83, about 18%), while the less frequent combination was “Education, Health, Other” (2 studies out of 83, about 2.4%).

Number of dimensions together considered in the articles reviewed

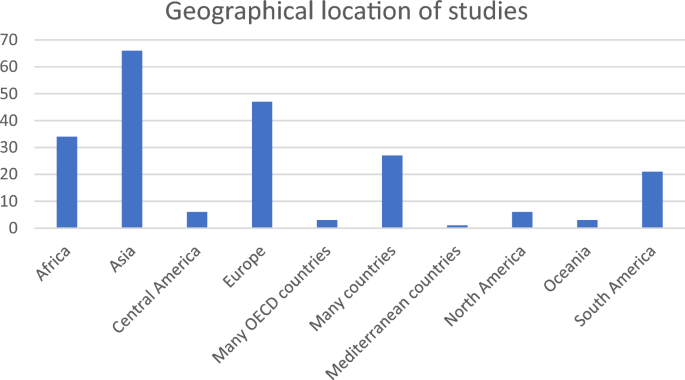

The next descriptive analysis concerns the place where empirical studies refer to. The countries with the greatest number of studies were China (13), Pakistan (12) and India (11). Distributed by continent (Fig. 6 ), the studies were mainly made in Asia (30.84%, 66), in Europe (21.96%, 47) and in Africa (15.89%, 34). For some studies (9.35%, 20), the continent could not be clearly identified since the ‘many countries analysed’ may belong to different continents. Only six studies (2.8%) were found to refer to North America, in particular to the United States of America (USA). As the most powerful economy in the world, with one of the highest rates of poverty in the developed world, and an extreme extent of income and wealth inequality when compared to other industrialized countries, we could have expected the country to be one of the main fields of research. However, the USA does not predominate in empirical studies of multidimensional poverty. In this respect, the information presented in Fig. 6 gives researchers an important opportunity for empirical investigation on multidimensional poverty in the USA, as few relevant studies were identified in recent years in this review. On the other hand, Asian and European researchers in poverty wishing to study empirically the multidimensional poverty shall benefit of the various studies published on Asian or European countries for comparative purposes in order to provide more robust conclusions.

Geographic location of studies distributed by continent

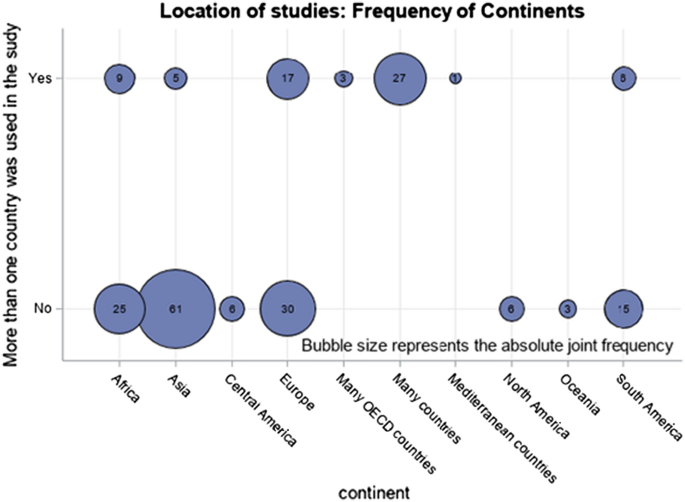

As a matter of fact, as shown in Fig. 7 , apart from the categories ‘many OECD countries’, ‘Mediterranean countries’, ‘many countries’, within the same continent only few studies (e.g., related to Europe and South America) involve more than one country. This evidence calls for comparative studies among countries on multidimensional poverty.

Country comparison by continent

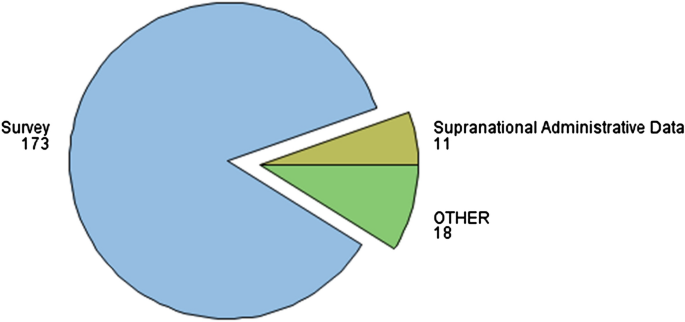

Aiming to help future research on this subjects, the main data sources used by authors were also checked. A marked preference for secondary data (202 out of 214) was observed (Fig. 8 ).

Secondary data type

Among secondary data type, it is evidenced that the use of surveys is still predominant. Notwithstanding the era of big data, survey research is still needed. Future works might explore the way how the two data sources may be used together in order to provide richer dataset and enhance poverty measurement.

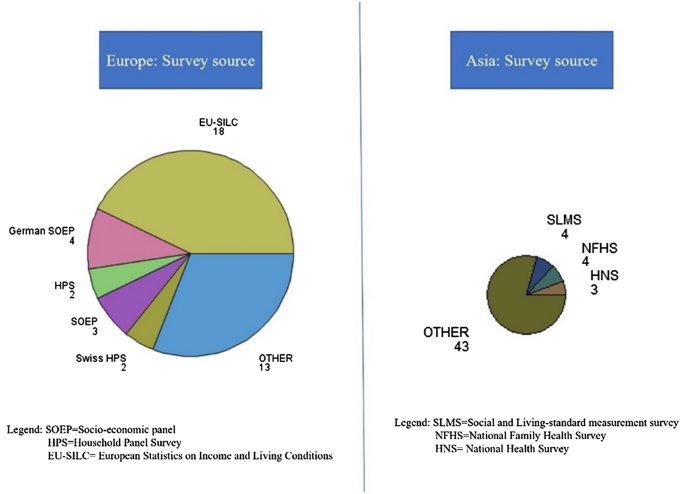

Figure 9 focuses on the most researched continents, namely Asia and Europe, and for each one considers the main survey source. It clearly emerges that in Asia there is a fragmented use of surveys, while in Europe the use of EU-SILC data is predominant as it is a cross-sectional, longitudinal, harmonized survey with a full coverage of all European Union member states.

Survey source in the two most researched continents

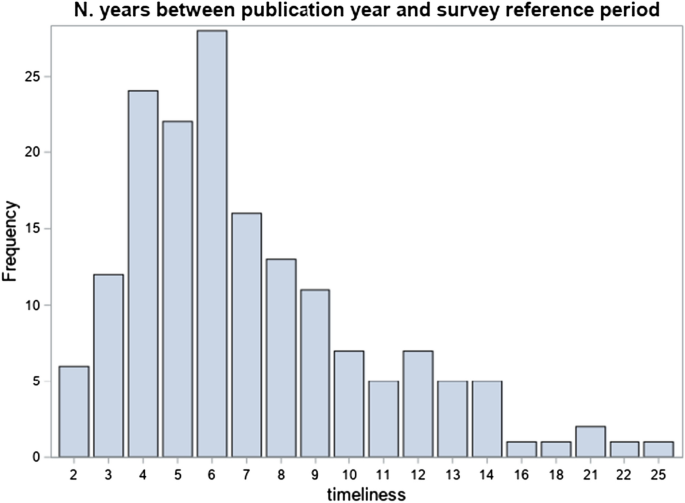

Moreover, from Fig. 10 another issue emerges: the inadequate timeliness, namely the period between the year when the study has been published and the reference period of the survey wave. However, it is acknowledged that such a weakness is common to all empirical studies that make use of secondary data produced by Bureaus of Statistics. This finding emerged from the SLR paves the way for future research that might experiment the combined use of traditional data sources (e.g., surveys, census and administrative data) and modern big data. Both data sources can significantly reduce the cost of reporting and improve the timeliness, as the data collection is less time and resource intensive than for conventional data.

Timeliness of reviewed surveys

4 Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of this paper was to provide a systematic framing of the literature on multi-dimensional poverty and related concepts until 2019. In particular, the review was conducted by querying the Scopus and the Web of Science databases, according to the keywords ‘multidimensional poverty’, ‘multidimensional inequality’, ‘multidimensional well-being’, and ‘multidimensional wellbeing’. A number of 669 studies was found, which was reduced to 314 after the abstract review. Next, the analysis of the full-text studies brought to the final number of 229 articles included in the review. Three main research questions were formulated to select and to analyze the studies, related to the definition of multidimensional poverty, the introduction of methods to synthetize and measure the multidimensional poverty, and the use of different dimensions in empirical applications.

The current work found that the amount of scientific literature devoted to enlarge the study of poverty or well-being from an income-based only perspective to a multidimensional one, has increased in the last few years, and especially from 2017 to 2019. In particular, besides the economic dimension, other three important poverty-related dimensions clearly emerged from the review: education, health, and living standards. However, one interesting finding is that the definitions of multidimensional poverty proposed in the literature often move around the income/consumption dimension, which has been considered as the main, most important conceptualization of poverty.

Another important issue which emerged from this study is that several different methods have been employed in the reviewed studies such as the fuzzy theory, the Gini index, and models and methods based on latent variables, but the most frequently used approach relies on the well-established Alkire–Foster method. In fact, the framework developed under the AF method for the measurement of multidimensional deprivations has turned to be very flexible so that it is currently used for large scale studies such as the computation of the multidimensional poverty index (MPI) by the United Nations, based on the three dimensions of health, education, and standard of living. Despite the primacy of the AF method, some limitations have been raised in the literature. Likely the main practical limitation is that the method requires that the data are available from the same survey and linked at the individual or household level (Alkire and Foster 2011b ). Consequently, different data sources cannot be used, thus limiting the applicability of the method and, for example, the number of countries that could be compared within this framework. The investigation of multidimensional poverty measures based on the AF method requires efforts in collecting data uniformly and systematically. From the methodological point of view, as discussed in Sect. 3.2.2 , the limitations identified in the literature are concerned with the sensitivity of the AF method to the methods of identification and aggregation of the dimensions and the weighting schemes. The authors of the AF method themselves identified some common misunderstandings of their approach in Alkire and Foster ( 2011b ). In particular, they clarify that the method is sensitive to the joint distribution of deprivations, unlike other unidimensional or marginal methods, and that this is a distinctive feature of their proposal. The method represents a general framework for poverty measurement in a multidimensional perspective and should be operationalized by making proper choices which depend on the objectives of the single empirical studies.

The SLR here conducted allows us to conclude that the multidimensionality is not an unambiguous concept. Various dimensions may contribute to its definition and, notwithstanding we can observe frequently common dimensions (e.g., economic, health, education, living standards), their combined use is not obvious nor the items used to measure each specific dimension. On the empirical side, we found that some countries are under researched (e.g., USA). On the other hand, some geographical area, namely Asia or Europe, shall benefit of a vast empirical literature. Notwithstanding the high number of studies in these areas, a lack of comparative studies clearly emerged and paves the wave for future research. Moreover, a predominant use of surveys for data collection was observed that take along with it the often-inadequate timeliness issue. Future works might experiment the combined use of traditional surveys and new data sources based, for example, on big data.

It should be noted that the current literature review has some limitations. The most important one lies in the choices made during the systematic review design. Firstly, the review was solely restricted to the two “Scopus” and “Web of Science” databases since they represent the two biggest bibliographic databases covering literature from almost any discipline. Then, the research was limited to journal articles only. As a consequence, working papers, conference proceedings, books or book chapters, even if consistent with the research keys, were omitted from the results (for instance, the following references Alkire and Foster 2007 , rev 2008 , 2009 ; Fattore et al. 2012 ; Foster 2009 ; Sen 1985 , were not caught by the queries). Thirdly, efforts were focused on articles published in English while articles published in other languages (despite the abstract in English) were excluded, as their inclusion may have increased challenges with respect to time and expertise in non-English languages, thus conducting to a knowledge loss. However, we are aware of the fact that limiting the SLR to English-only studies may increase the risk of bias. Future works may consider the inclusion of non-English studies in order to prevent such a risk.

An additional limitation is the time range of the systematic review, as the last publication year recorded is 2019. This choice is motivated by the fact that the following year 2020 has been characterized by the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. We believe that the difficult epidemiological situation, still affecting people’s life, may have deeply changed the impact of the different dimensions of poverty and gave much importance to dimensions such as psychological well-being, social exclusion, and technological and digital gaps. Future works might explore emerging issues related to poverty.

A natural progression of this work is to conduct a post-COVID systematic review of the literature including studies from 2020 onwards, considering a time horizon after the initial year of the COVID-19 pandemic of at least five years, and to compare the findings with the current ones.

Moreover, a limitation concerns the search method, which was through “keywords” (see Sect. 2.2.1 ). It is likely that some relevant articles that used different words in the title, abstract, keywords or topic were omitted from the systematic review. An example is the paper by Fattore ( 2016 ), cited in Sect. 3.2.2 , which title contains the word “deprivation” instead of “poverty”, “well-being”, or “inequality” and was therefore excluded from the results. Future research might consider additional keywords such as: “social exclusion”, “deprivation”, “vulnerability”, “inequality of opportunity”, or “quality of life”. Moreover, future works might make use of text mining techniques to analyse in deep the occurrence of words in the definition and conceptualization of poverty in order to extrapolate the main dimensions considered behind the well-known group of four: health, economics, education, and living standards.