- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How the Black Power Movement Influenced the Civil Rights Movement

By: Sarah Pruitt

Updated: July 27, 2023 | Original: February 20, 2020

By 1966, the civil rights movement had been gaining momentum for more than a decade, as thousands of African Americans embraced a strategy of nonviolent protest against racial segregation and demanded equal rights under the law.

But for an increasing number of African Americans, particularly young Black men and women, that strategy did not go far enough. Protesting segregation, they believed, failed to adequately address the poverty and powerlessness that generations of systemic discrimination and racism had imposed on so many Black Americans.

Inspired by the principles of racial pride, autonomy and self-determination expressed by Malcolm X (whose assassination in 1965 had brought even more attention to his ideas), as well as liberation movements in Africa, Asia and Latin America, the Black Power movement that flourished in the late 1960s and ‘70s argued that Black Americans should focus on creating economic, social and political power of their own, rather than seek integration into white-dominated society.

Crucially, Black Power advocates, particularly more militant groups like the Black Panther Party, did not discount the use of violence, but embraced Malcolm X’s challenge to pursue freedom, equality and justice “by any means necessary.”

The March Against Fear - June 1966

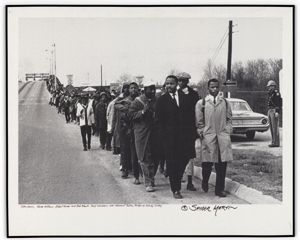

The emergence of Black Power as a parallel force alongside the mainstream civil rights movement occurred during the March Against Fear, a voting rights march in Mississippi in June 1966. The march originally began as a solo effort by James Meredith, who had become the first African American to attend the University of Mississippi, a.k.a. Ole Miss, in 1962. He had set out in early June to walk from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, a distance of more than 200 miles, to promote Black voter registration and protest ongoing discrimination in his home state.

But after a white gunman shot and wounded Meredith on a rural road in Mississippi, three major civil rights leaders— Martin Luther King, Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Floyd McKissick of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) decided to continue the March Against Fear in his name.

In the days to come, Carmichael, McKissick and fellow marchers were harassed by onlookers and arrested by local law enforcement while walking through Mississippi. Speaking at a rally of supporters in Greenwood, Mississippi, on June 16, Carmichael (who had been released from jail that day) began leading the crowd in a chant of “We want Black Power!” The refrain stood in sharp contrast to many civil rights protests, where demonstrators commonly chanted “We want freedom!”

The Campus Walkout That Led to America’s First Black Studies Department

The 1968 strike was the longest by college students in American history. It helped usher in profound changes in higher education.

The 1969 Raid That Killed Black Panther Leader Fred Hampton

Details around the 1969 police shooting of Hampton and other Black Panther members took decades to come to light.

Civil Rights Movement

Jim Crow Laws During Reconstruction, Black people took on leadership roles like never before. They held public office and sought legislative changes for equality and the right to vote. In 1868, the 14th Amendment to the Constitution gave Black people equal protection under the law. In 1870, the 15th Amendment granted Black American men the […]

Stokely Carmichael’s Role in Black Power

Though the author Richard Wright had written a book titled Black Power in 1954, and the phrase had been used among other Black activists before, Stokely Carmichael was the first to use it as a political slogan in such a public way. As biographer Peniel E. Joseph writes in Stokely: A Life , the events in Mississippi “catapulted Stokely into the political space last occupied by Malcolm X,” as he went on TV news shows, was profiled in Ebony and written up in the New York Times under the headline “Black Power Prophet.”

Carmichael’s growing prominence put him at odds with King, who acknowledged the frustration among many African Americans with the slow pace of change but didn’t see violence and separatism as a viable path forward. With the country mired in the Vietnam War , (a war both Carmichael and King spoke out against) and the civil rights movement King had championed losing momentum, the message of the Black Power movement caught on with an increasing number of Black Americans.

Black Power Movement Growth—and Backlash

King and Carmichael renewed their alliance in early 1968, as King was planning his Poor People’s Campaign, which aimed to bring thousands of protesters to Washington, D.C., to call for an end to poverty. But in April 1968, King was assassinated in Memphis while in town to support a strike by the city’s sanitation workers as part of that campaign.

In the aftermath of King’s murder, a mass outpouring of grief and anger led to riots in more than 100 U.S. cities . Later that year, one of the most visible Black Power demonstrations took place at the Summer Olympics in Mexico City, where Black athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised black-gloved fists in the air on the medal podium.

By 1970, Carmichael (who later changed his name to Kwame Ture) had moved to Africa, and SNCC had been supplanted at the forefront of the Black Power movement by more militant groups, such as the Black Panther Party , the US Organization, the Republic of New Africa and others, who saw themselves as the heirs to Malcolm X’s revolutionary philosophy. Black Panther chapters began operating in a number of cities nationwide, where they advocated a 10-point program of socialist revolution (backed by armed self-defense). The group’s more practical efforts focused on building up the Black community through social programs (including free breakfasts for school children ).

Many in mainstream white society viewed the Black Panthers and other Black Power groups negatively, dismissing them as violent, anti-white and anti-law enforcement. Like King and other civil rights activists before them, the Black Panthers became targets of the FBI’s counterintelligence program, or COINTELPRO, which weakened the group considerably by the mid-1970s through such tactics as spying, wiretapping, flimsy criminal charges and even assassination .

Legacy of Black Power

Even after the Black Power movement’s decline in the late 1970s, its impact would continue to be felt for generations to come. With its emphasis on Black racial identity, pride and self-determination, Black Power influenced everything from popular culture to education to politics, while the movement’s challenge to structural inequalities inspired other groups (such as Chicanos, Native Americans, Asian Americans and LGBTQ people) to pursue their own goals of overcoming discrimination to achieve equal rights.

The legacies of both the Black Power and civil rights movements live on in the Black Lives Matter movement . Though Black Lives Matter focuses more specifically on criminal justice reform, it channels the spirit of earlier movements in its efforts to combat systemic racism and the social, economic and political injustices that continue to affect Black Americans.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Gr. 12 HISTORY REVISION: THE BLACK POWER MOVEMENT

REVISION: THE BLACK POWER MOVEMENT

Do you have an educational app, video, ebook, course or eResource?

Contribute to the Western Cape Education Department's ePortal to make a difference.

Home Contact us Terms of Use Privacy Policy Western Cape Government © 2024. All rights reserved.

Black Power

Although African American writers and politicians used the term “Black Power” for years, the expression first entered the lexicon of the civil rights movement during the Meredith March Against Fear in the summer of 1966. Martin Luther King, Jr., believed that Black Power was “essentially an emotional concept” that meant “different things to different people,” but he worried that the slogan carried “connotations of violence and separatism” and opposed its use (King, 32; King, 14 October 1966). The controversy over Black Power reflected and perpetuated a split in the civil rights movement between organizations that maintained that nonviolent methods were the only way to achieve civil rights goals and those organizations that had become frustrated and were ready to adopt violence and black separatism.

On 16 June 1966, while completing the march begun by James Meredith , Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) rallied a crowd in Greenwood, Mississippi, with the cry, “We want Black Power!” Although SNCC members had used the term during informal conversations, this was the first time Black Power was used as a public slogan. Asked later what he meant by the term, Carmichael said, “When you talk about black power you talk about bringing this country to its knees any time it messes with the black man … any white man in this country knows about power. He knows what white power is and he ought to know what black power is” (“Negro Leaders on ‘Meet the Press’”). In the ensuing weeks, both SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) repudiated nonviolence and embraced militant separatism with Black Power as their objective.

Although King believed that “the slogan was an unwise choice,” he attempted to transform its meaning, writing that although “the Negro is powerless,” he should seek “to amass political and economic power to reach his legitimate goals” (King, October 1966; King, 14 October 1966). King believed that “America must be made a nation in which its multi-racial people are partners in power” (King, 14 October 1966). Carmichael, on the other hand, believed that black people had to first “close ranks” in solidarity with each other before they could join a multiracial society (Carmichael, 44).

Although King was hesitant to criticize Black Power openly, he told his staff on 14 November 1966 that Black Power “was born from the wombs of despair and disappointment. Black Power is a cry of pain. It is in fact a reaction to the failure of White Power to deliver the promises and to do it in a hurry … The cry of Black Power is really a cry of hurt” (King, 14 November 1966).

As the Southern Christian Leadership Conference , the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People , and other civil rights organizations rejected SNCC and CORE’s adoption of Black Power, the movement became fractured. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Black Power became the rallying call of black nationalists and revolutionary armed movements like the Black Panther Party, and King’s interpretation of the slogan faded into obscurity.

“Black Power for Whom?” Christian Century (20 July 1966): 903–904.

Branch, At Canaan’s Edge , 2006.

Carmichael and Hamilton, Black Power , 1967.

Carson, In Struggle , 1981.

King, Address at SCLC staff retreat, 14 November 1966, MLKJP-GAMK .

King, “It Is Not Enough to Condemn Black Power,” October 1966, MLKJP-GAMK .

King, Statement on Black Power, 14 October 1966, TMAC-GA .

King, Where Do We Go from Here , 1967.

“Negro Leaders on ‘Meet the Press,’” 89th Cong., 2d sess., Congressional Record 112 (29 August 1966): S 21095–21102.

- UConn Library

- Africana Studies Subject Guide

Black Power Movement

Africana studies subject guide — black power movement.

- Getting Started

- Disciplinary Foundations

- Africana Religion

- Afrofuturism

- Black Art, Film + Music

- Black Diasporas

- Black Indigeneity

- Black Literature

- Black Lives Matter

- Black New England

- Environmental Racism

- Fashion + Beauty

- Gender + Sexuality

- Health + Medicine

- Prison Studies

- Race + Disability

- Sports + Athletics

- Travel + Transportation

- WOC & Wellness

- Databases & Journals

- Finding Books

- Primary Sources (Archival Collections)

- Critical Race Theory (CRT)

- Slavery & Abolition Resources Online

- Afro-Latino Studies

- Data & Statistics

- Citation Styles Resources (MLA, APA, Chicago)

This page features a small selection of UConn library and external resources to support learning and research pertaining to the Black Power Movement. This list is meant to be exploratory and is not a comprehensive representation or list of the library's holdings.

For additional assistance, please contact Samuel Boss, at [email protected] .

Black Power

-- National Museum of African American History & Culture, on the The Foundations of Black Power (2019).

Collection Highlights

Black Power Mixtape, 19657-1975 (2011) is a 9-part documentary series by Swedish journalists drawn to the US by stories of urban unrest and revolution. Featuring prominent figures like Stokely Carmichael, Bobby Seale, Angela Davis, and Eldridge Cleaver, the filmmakers captured movement leaders in intimate moments and remarkably unguarded interviews. Available in DVD format at the UConn library . Watch a clip:

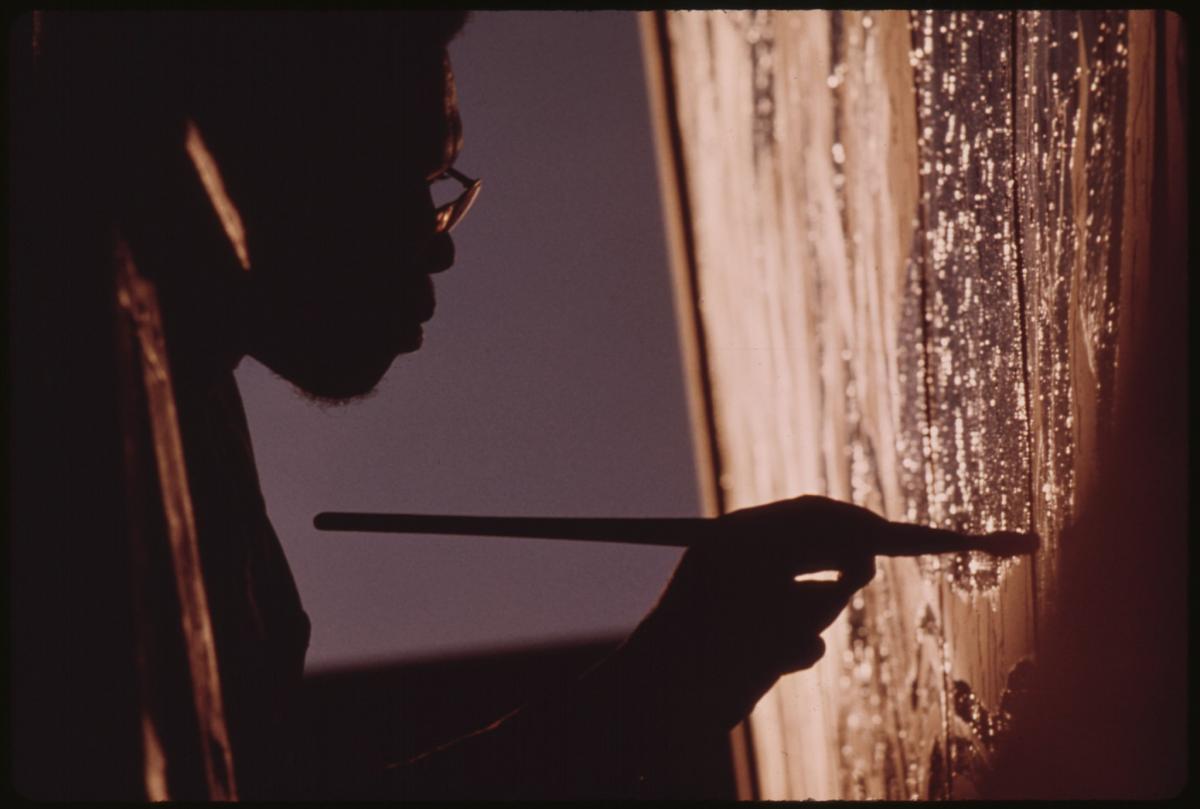

Black Arts Movement

Black Panther Party

Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee

Online Resources

- Black Panthers Collection | Television news collection from the San Francisco Bay Area Television Archive at San Francisco State University

- Black Panther Party Newspaper | Free full-text access to a digital collection of the Party's official newspaper, with issues ranging from 1967-76

- FBI Vault | Surveillance record from the Federal Bureau of Investigation on Black religious, social, and political organizations and their leaders

- Huey P. Newton Foundation | Organization providing information on the history of the Black Panther Party with video, sound files, and other primary sources

- SNCC Digital Gateway | A documentary website by the SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University that uses documents, photographs, and audiovisual material to chronicle SNCC’s historic struggle for voting rights.

- Vanderbilt Television News Archives | Contains digitized video of network television news reporting on the Black Panthers back to 1967. Non-digitized news segments can be requested from the archive. Search for "Black Panthers"

- << Previous: Black New England

- Next: Environmental Racism >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2024 11:41 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/afamstudies

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Options

- Why Publish with JAH?

- About Journal of American History

- About the Organization of American Historians

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

The Black Power Movement: A State of the Field

Peniel E. Joseph is a professor of history at Tufts University.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Peniel E. Joseph, The Black Power Movement: A State of the Field, Journal of American History , Volume 96, Issue 3, December 2009, Pages 751–776, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/96.3.751

- Permissions Icon Permissions

“By all rights, there no longer should be much question about the meaning—at least the intended meaning—of Black Power,” the journalist Charles Sutton observed in January 1967. “Between the speeches and writings of Stokely Carmichael, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee ( sncc ),” Sutton continued, “the explanations of Floyd McKissick, director of the Congress of Racial Equality ( core ), and the writings of more than a score of scholars and commentators, the slogan and its various assumptions have been fairly thoroughly examined.” 1

Clearly Sutton was wrong. Despite efforts to define it both then and today, “black power” exists in the American imagination through a series of iconic, yet fleeting images—ranging from gun-toting Black Panthers to black-gloved sprinters at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics—that powerfully evoke the era's confounding mixture of triumph and tragedy. Indeed, the iconography of Stokely Carmichael in Greenwood, Mississippi, Black Panthers marching outside an Oakland, California, courthouse, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation's wanted poster for Angela Davis serves as a kind of visual shorthand to understanding the history of the era, but such images tell us very little about the movement that birthed them.

Organization of American Historians members

Personal account.

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| December 2016 | 12 |

| January 2017 | 32 |

| February 2017 | 47 |

| March 2017 | 115 |

| April 2017 | 130 |

| May 2017 | 131 |

| June 2017 | 19 |

| July 2017 | 11 |

| August 2017 | 17 |

| September 2017 | 20 |

| October 2017 | 71 |

| November 2017 | 67 |

| December 2017 | 82 |

| January 2018 | 153 |

| February 2018 | 65 |

| March 2018 | 48 |

| April 2018 | 119 |

| May 2018 | 69 |

| June 2018 | 75 |

| July 2018 | 126 |

| August 2018 | 33 |

| September 2018 | 43 |

| October 2018 | 84 |

| November 2018 | 100 |

| December 2018 | 44 |

| January 2019 | 49 |

| February 2019 | 58 |

| March 2019 | 73 |

| April 2019 | 148 |

| May 2019 | 94 |

| June 2019 | 41 |

| July 2019 | 33 |

| August 2019 | 35 |

| September 2019 | 35 |

| October 2019 | 114 |

| November 2019 | 74 |

| December 2019 | 78 |

| January 2020 | 57 |

| February 2020 | 198 |

| March 2020 | 158 |

| April 2020 | 356 |

| May 2020 | 36 |

| June 2020 | 40 |

| July 2020 | 23 |

| August 2020 | 16 |

| September 2020 | 46 |

| October 2020 | 56 |

| November 2020 | 84 |

| December 2020 | 82 |

| January 2021 | 73 |

| February 2021 | 113 |

| March 2021 | 96 |

| April 2021 | 122 |

| May 2021 | 101 |

| June 2021 | 32 |

| July 2021 | 15 |

| August 2021 | 38 |

| September 2021 | 81 |

| October 2021 | 78 |

| November 2021 | 87 |

| December 2021 | 100 |

| January 2022 | 86 |

| February 2022 | 61 |

| March 2022 | 94 |

| April 2022 | 97 |

| May 2022 | 73 |

| June 2022 | 36 |

| July 2022 | 21 |

| August 2022 | 31 |

| September 2022 | 57 |

| October 2022 | 111 |

| November 2022 | 114 |

| December 2022 | 55 |

| January 2023 | 103 |

| February 2023 | 79 |

| March 2023 | 104 |

| April 2023 | 120 |

| May 2023 | 100 |

| June 2023 | 38 |

| July 2023 | 10 |

| August 2023 | 11 |

| September 2023 | 54 |

| October 2023 | 95 |

| November 2023 | 95 |

| December 2023 | 71 |

| January 2024 | 54 |

| February 2024 | 94 |

| March 2024 | 69 |

| April 2024 | 125 |

| May 2024 | 82 |

| June 2024 | 28 |

| July 2024 | 26 |

| August 2024 | 21 |

| September 2024 | 9 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Process - a blog for american history

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1945-2314

- Print ISSN 0021-8723

- Copyright © 2024 Organization of American Historians

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Civil Rights Movement: "Black Power" Era

- Civil Rights Movement: "Black Power" Era /

- Discussion & Essay Questions

Cite This Source

Available to teachers only as part of the teaching civil rights movement: "black power" erateacher pass, teaching civil rights movement: "black power" era teacher pass includes:.

- Assignments & Activities

- Reading Quizzes

- Current Events & Pop Culture articles

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Related Readings in Literature & History

Sample of Discussion & Essay Questions

Big picture.

- Was it just a coincidence that a more militant form of black activism emerged right after?

- Or did the march somehow contribute to the formation of "black power?"

- How significant was the September bombing in Birmingham?

- Was this possible?

Tired of ads?

Logging out…, logging out....

You've been inactive for a while, logging you out in a few seconds...

W hy's T his F unny?

The Black Power Movement: Understanding Its Origins, Leaders, and Legacy

Politicians love to quote Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous line about the long arc of the moral universe slowly bending toward justice. But social justice movements have long been accelerated by radicals and activists who have tried to force that arc to bend faster. That was the case for the Black power movement, an outgrowth of the civil rights movement that emerged in the 1960s with calls to reject slow-moving integration efforts and embrace self-determination. The movement called for Black Americans to create their own cultural institutions, take pride in their heritage, and become economically independent. Its legacy is still felt today in the work of the movement for Black lives. Here’s what to know about how the Black power movement started and what it stood for.

What were the origins of the movement?

It started with a march. Four years after James Meredith became the first Black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi, he embarked on a solo walk from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi. Meredith’s “March Against Fear” was a protest against the fear instilled in Black Americans who attempted to register to vote, and the overall culture of fear that was part of day-to-day life. On June 5, 1966, he began his 220-mile trek, equipped with nothing but a helmet and walking stick . On his second day, June 6, Meredith crossed the Mississippi border (by this point he’d been joined by a small number of supporters, reporters, and photographers). That’s where a white man, Aubrey James Norvell, shot Meredith in the head, neck, and back. Meredith survived but was unable to continue marching.

In response, civil rights leaders including King and Stokely Carmichael, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), came together in Mississippi to continue Meredith’s march and push for voting rights. Carmichael, who King had considered to be one of the most promising leaders of the civil rights movement, had gone from embracing nonviolent protests in the early '60s to pushing for a more radical approach for change. "[Dr. King] only made one fallacious assumption: In order for nonviolence to work, your opponent has to have a conscience. The United States has no conscience," said Carmichael.

Carmichael was arrested when the march reached Greenwood, Mississippi, and after his release he led a crowd in a chant , at a rally , “We want Black power!” Although the slogan “Black power for Black people” was used by Alabama’s Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) the year before, Carmichael’s use of the phrase, on June 16, 1966, is what drew national attention to the concept.

Who are some of the movement’s prominent leaders?

Malcolm X was assassinated before the rise of the Black power movement, but his life and teachings laid the groundwork for it and served as one of the movement’s greatest inspirations . The movement drew on Malcolm X’s declarations of Black pride and his understanding that the freedom movement for Black Americans was intertwined with the fight for global human rights and an anti-colonial future.

Carmichael, a Trinidad-born New Yorker (later known as Kwame Ture), and who popularized the phrase "Black power,” was a key leader of the movement. Carmichael was inspired to get involved with the civil rights movement after seeing Black protesters hold sit-ins at segregated lunch counters across the South. During his time at Howard University, he joined SNCC and became a Freedom Rider , joining other college students in challenging segregation laws as they traveled through the South.

Eventually, after being arrested more than 32 times and witnessing peaceful protesters get met with violence, Carmichael moved away from the passive resistance method of fighting for freedom. “I think Dr. King is a great man, full of compassion. He is full of mercy and he is very patient. He is a man who could accept the uncivilized behavior of white Americans, and their unceasing taunts; and still have in his heart forgiveness,” Carmichael once said , as quoted in The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 documentary. “Unfortunately, I am from a younger generation. I am not as patient as Dr. King, nor am I as merciful as Dr. King. And their unwillingness to deal with someone like Dr. King just means they have to deal with this younger generation.”

Activist, author, and scholar Angela Davis , one of the most iconic faces of the movement, later told the Nation , "The movement was a response to what were perceived as the limitations of the civil rights movement.… Although Black individuals have entered economic, social, and political hierarchies, the overwhelming number of Black people are subject to economic, educational, and carceral racism to a far greater extent than during the pre-civil rights era.”

What did the movement stand for?

Dr. King believed “Black power” meant "different things to different people,” and he was right. After Carmichael uttered the slogan, Black power groups began forming across the country, putting forth different ideas of what the phrase meant. Carmichael once said , “When you talk about Black power, you talk about bringing this country to its knees any time it messes with the Black man…. Any white man in this country knows about power. He knows what white power is, and he ought to know what Black power is.”

Some Black civil rights leaders opposed the slogan. Dr. King, for example, believed it to be “essentially an emotional concept” and worried that it carried “connotations of violence and separatism.” Many white people did, in fact, interpret “Black power” as meaning a violently anti-white movement. In 2020, during Congressman John Lewis’s funeral, former president Bill Clinton said , “There were two or three years there where the movement went a little too far toward Stokely, but in the end, John Lewis prevailed.” By “Stokely,” he meant the Black power movement.

According to the National Museum of African American History & Culture (NMAAHC), the Black power movement aimed to “emphasize Black self-reliance and self-determination more than integration,” and supporters of the movement believed “African Americans should secure their human rights by creating political and cultural organizations that served their interests.” The Black power movement sought to give Black people control of their own lives by empowering them culturally, politically, and economically. At the same time, it instilled a sense of pride in Black people who began to further embrace Black art, history , and beauty .

Although Dr. King didn’t publicly support the movement, according to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, in November 1966, he told his staff that Black power “was born from the wombs of despair and disappointment. Black power is a cry of pain. It is, in fact, a reaction to the failure of white power to deliver the promises and to do it in a hurry…. The cry of Black power is really a cry of hurt.”

How did “Black power” relate to the civil rights movement and Black Panther Party?

At its core, the Black power movement was a movement for Black liberation . What made the Black power movement different from the civil rights movement of the early 1960s, and frightening to white people, was that it embraced forms of self-defense . In fact, the full name of the Black Panther Party was “the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense.”

Huey Newton [R], founder of the Black Panther Party, sits with Bobby Seale at party headquarters in San Francisco.

The Black Panthers were founded in 1966 by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, two students in Oakland, California. Like Carmichael, Newton and Seale couldn’t stand the brutality Black people faced at the hands of police officers and a legal system that empowered those officers while oppressing Black citizens. The Black power movement came to be as a result of the work and impact of the civil rights movement, but the Black Panther party, which also strayed from the idea of integration, was an extension of the Black power movement. According to the NMAAHC , it was the “most influential militant” Black power organization of the era.

The SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) embraced militant separatism in alignment with the Black power movement, while the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) opposed it. Subsequently, the movement was divided, and in the late 1960s and '70s, the slogan became synonymous with Black militant organizations. Peniel Joseph , founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the University of Austin Texas’s LBJ School of Public Affairs, told NPR that although the movement is “remembered by the images of gun-toting black urban militants, most notably the Black Panther Party...it's really a movement that overtly criticized white supremacy.”

“You ask me whether I approve of violence? That just doesn’t make any sense at all," Angela Davis said in The Black Power Mixtape . “Whether I approve of guns? I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama. Some very, very good friends of mine were killed by bombs – bombs that were planted by racists. I remember, from the time I was very small, the sound of bombs exploding across the street and the house shaking. That’s why,” Davis explained further, "when someone asks me about violence, I find it incredible because it means the person asking that question has absolutely no idea what Black people have gone through and experienced in this country from the time the first Black person was kidnapped from the shores of Africa.”

What impact did the movement have on U.S. history?

The Black power movement empowered generations of Black organizers and leaders, giving them new figures to look up to and a new way to think of systemic racism in the U.S. The raised fist that became a symbol of Black power in the 1960s is one of the main symbols of today’s Black Lives Matter movement .

“When we think about its impact on democratic institutions, it's really on multiple levels,” Joseph told NPR . “On one level, politically, the first generation of African American elected officials, they owe their standing to both the civil rights and voting rights act of '64 and '65. But to actually get elected in places like Gary, Indiana, in 1967, it required Black power activism to help them build up new Black, urban political machines. So its impact is really, really profound.”

Want more from Teen Vogue ? Check this out: The Black Radical Tradition in the South Is Nothing to Sneer At

Stay up-to-date with the politics team. Sign up for the Teen Vogue Take!

The Rise of Black Power in America – A Historical Overview

The Black Power movement was a political and social movement that emerged in the United States during the 1960s. It aimed to empower black Americans and challenge systemic racism through self-determination, cultural pride, and activism.

The movement was a response to the ongoing struggle for civil rights and equality, which had been hampered by institutionalized discrimination and violence against black people.

In this article, we will explore the historical context of the Black Power movement, its ideology, and its legacy in American society. By understanding the rise of Black Power, we can gain insight into one of the most important chapters in the history of racial justice in the US.

The Struggle for Civil Rights and Equality

The Black Power movement emerged in the context of the broader struggle for civil rights and equality that had been ongoing in the United States since the 1950s. Despite some gains made by black Americans during this time, such as the desegregation of schools and public spaces, systemic racism remained deeply entrenched in American society. This manifested in the form of discriminatory laws and policies, police brutality, economic inequality, and other forms of oppression.

The Civil Rights Movement, led by figures such as Martin Luther King Jr., focused on achieving legal equality for black Americans through nonviolent direct action and peaceful protest.

However, many activists felt that this approach did not go far enough in addressing the root causes of racial injustice. They believed that true liberation could only come through a radical transformation of American society.

This sentiment was echoed by leaders like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael, who advocated for a more militant approach to achieving black empowerment. They rejected integration as a goal and instead called for self-determination and black pride. The ideas put forth by these leaders laid the groundwork for what would become known as Black Power.

The Emergence of Black Power

The term “Black Power” emerged in the mid-1960s as a rallying cry for black activists who were frustrated with the slow pace of progress towards racial equality. It was first coined by Stokely Carmichael, a leader within the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), during a rally in Mississippi in 1966.

Carmichael used the term to express his frustration with the limitations of nonviolent resistance and civil disobedience as tactics for achieving change. He argued that black people needed to take control of their own destiny and use whatever means necessary to achieve liberation and self-determination.

The concept of Black Power gained popularity among black communities across America, particularly after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968. Many activists saw King’s death as evidence that peaceful protest was not enough to bring about real change, and began to embrace more militant tactics like armed self-defense and community organizing.

One of the earliest manifestations of Black Power was the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) in Alabama, which was founded in 1965. The LCFO was formed in response to the exclusion of black people from the Democratic Party in Lowndes County, where they made up the majority of the population but were prevented from voting and holding political office.

The LCFO adopted a black panther as its symbol and became known as the “Black Panther Party” before the better-known Black Panther Party was founded in California. The LCFO’s platform called for black self-determination and included demands like full employment, decent housing, and an end to police brutality.

The Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party, founded in 1966, became one of the most visible expressions of Black Power ideology. The party advocated for black self-defence and community empowerment through programs like free breakfast for children, community health clinics, and political education classes.

In addition to these grassroots movements, Black Power also had an impact on mainstream politics. In 1972, Shirley Chisholm became the first African American woman elected to Congress by running as a candidate for president with a platform that emphasized issues important to black communities.

Key Figures of the Black Power Movement

These are just some of many important figures within the Black Power movement whose ideas continue to shape conversations around race, justice, and equality today.

Stokely Carmichael

Stokely Carmichael was a key figure in the Black Power movement, and his advocacy for black self-determination helped to shape the movement’s goals and strategies.

Prior to his involvement with the Black Power movement, Carmichael was an active member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), focusing on nonviolent direct action as a means of achieving civil rights and racial equality.

However, Carmichael began to feel disillusioned with the limitations of nonviolence as a strategy for change. He believed that it was important for black people to assert their own power and autonomy rather than relying on white allies or institutions to grant them rights.

This led him to become one of the leading proponents of Black Power, a philosophy that emphasized black pride, self-determination, and community control.

Carmichael popularized the phrase “Black Power” during a speech he gave at a rally in Mississippi in 1966. The term quickly became associated with the broader goals of the Black Power movement, including economic empowerment, political representation, and cultural expression.

Carmichael also advocated for more militant tactics when necessary. He argued that armed resistance might be necessary in order to protect black communities from police brutality and other forms of violence. His ideas were controversial but influential within the movement.

Huey P. Newton

Huey P. Newton co-founded the Black Panther Party in 1966 with Bobby Seale. The Black Panther Party had a militant approach to achieving black liberation, which included advocating for armed self-defence and community organizing as means of empowerment.

Newton believed that black people had a right to defend themselves against police brutality and other forms of violence, and he advocated for the creation of community-based self-defense groups. He also believed that black people needed to organize themselves politically and economically in order to achieve true freedom and autonomy.

Under Newton’s leadership, the Black Panther Party established a number of programs aimed at improving conditions within black communities, including free breakfast programs for children, health clinics, and legal aid services. These programs addressed some of the systemic issues that kept black people oppressed, such as poverty, lack of access to healthcare, and unequal treatment under the law.

However, Newton’s ideas were controversial and often met with resistance from both government officials and other civil rights leaders who disagreed with his approach. He was arrested several times on various charges throughout his life, including charges related to murder and assault.

Angela Davis

Angela Davis is a prominent activist and scholar who played an important role in the Black Power movement. She participated in various civil rights and anti-racist movements, including the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Black Panther Party, and the Communist Party USA.

Davis was an outspoken advocate for black liberation, as well as her commitment to other progressive causes like prison abolition and feminism . She argued that systemic racism was deeply rooted in American society and that radical solutions were required to dismantle it.

As a member of the Communist Party USA, Davis also believed that capitalism was inherently exploitative and contributed to racial inequality. She believed that black people would only achieve true freedom fthrough a socialist revolution that would fundamentally transform society.

Davis was arrested multiple times on various charges related to her activism. In 1970, she was accused of being involved in a shooting at a courthouse in California that left several people dead. Although she denied any involvement in the crime, she became one of the most high-profile political prisoners of the era.

Malcolm X was a highly influential figure in the Black Power movement. He began his activism as a member of the Nation of Islam, a religious organization that advocated for black separatism and self-defense against white oppression.

As a spokesperson for the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X became known for his fiery speeches and uncompromising stance on issues related to racial justice. He believed that black people should take control of their own destinies and work towards economic independence through community-based initiatives like cooperatives and mutual aid societies.

However, after breaking with the Nation of Islam in 1964, Malcolm X’s views on race relations evolved significantly. He became more critical of the organization’s strict religious dogma and embraced a more inclusive vision of black nationalism that emphasized solidarity with other marginalized groups.

Malcolm X also began to advocate for armed self-defence against police brutality and other forms of violence directed at black people. He argued that nonviolent resistance was not effective in the face of systemic oppression and that black people had a right to defend themselves against racist attacks.

Bobby Seale

Seale co-founded the Black Panther Party with Huey P. Newton. He served as the party’s chairman from its inception in 1966 until 1974, and played a crucial role in shaping its ideology and tactics.

Seale believed that revolutionary change was necessary to address the systemic oppression faced by black people in America. He advocated for grassroots organizing and community empowerment, encouraging Black Panthers to become active in their communities through initiatives like free breakfast programs, healthcare clinics, and self-defence classes.

Under Seale’s leadership, the Black Panther Party became known for its militant tactics and confrontational approach to law enforcement. The organization established armed patrols to monitor police activity in black neighbourhoods and advocated for an end to police brutality and other forms of state violence against black people.

Eldridge Cleaver

Eldridge Cleaver was a prominent figure in the Black Power movement and an influential writer and activist. He became involved with the Black Panther Party during its early years, serving as its Minister of Information and later running for political office on behalf of the party.

Cleaver is perhaps best known for his book “ Soul on Ice ,” a collection of essays that explore his experiences as an incarcerated black man. The book is a classic of African American literature and played a significant role in shaping public perceptions of the Black Power movement.

In “Soul on Ice,” Cleaver explores themes like racism, police brutality, and black identity. He also discusses his own experiences with violence, drug addiction, and incarceration, offering a powerful critique of the American criminal justice system and its impact on black communities.

Assata Shakur

Assata Shakur was a member of the Black Liberation Army, a militant organization that fought for black liberation and self-determination during the 1970s.

Shakur was an activist against police brutality and racism, which she saw as systemic problems affecting black communities across America. She participated in numerous protests and demonstrations throughout her life, advocating for an end to police violence and other forms of state oppression.

In 1973, Shakur was arrested on charges related to a shootout with New Jersey State Troopers. She was convicted and sentenced to life in prison, but managed to escape from jail in 1979 and flee to Cuba, where she has been living in exile ever since.

Fred Hampton

Fred Hampton was a young, charismatic leader within the Chicago chapter of the Black Panther Party during the late 1960s. He had powerful oratory skills and spoke about the importance of fighting for racial justice and equality.

As a member of the Black Panther Party, Hampton worked to empower black communities through programs like free breakfast for children and community health clinics. He also organized protests against police brutality and advocated for an end to systemic racism in America.

Tragically, Hampton’s life was cut short when he was assassinated by police at just 21 years old. On December 4th, 1969, police raided Hampton’s apartment while he was sleeping next to his pregnant girlfriend. They shot and killed him in his bed, along with another Black Panther member who was also present.

Hampton’s death sparked outrage among black communities across America and brought renewed attention to issues like police brutality and state violence. His legacy lives on today as a symbol of resistance against systemic racism and oppression, inspiring generations of activists to continue fighting for a more just and equitable society.

The Ideology of Black Power

Black Power was a political ideology that rejected nonviolent resistance as the sole means for achieving racial justice and instead embraced more militant tactics.

At its core, Black Power sought to empower black communities to take control of their own destiny and reject white supremacy.

Self-determination was a key principle of Black Power. This meant that black people should have the right to determine their own political, economic, and social destiny without interference from white people or institutions. This included demands for greater representation in government and the creation of independent black-run institutions like schools, banks, and businesses.

Economic independence was also central to Black Power ideology. Activists believed that black people needed to build their own economic power through entrepreneurship, cooperative enterprises, and collective ownership of resources like land. This would help break the cycle of poverty and dependency on white-dominated institutions.

Cultural pride was another important aspect of Black Power. Activists sought to celebrate the unique culture and history of black Americans as a way to counteract centuries of racist propaganda that had denigrated blackness. This included promoting African-inspired fashion, music, art, literature, and language.

Different groups interpreted and applied these principles in different ways. Some embraced more militant tactics like armed self-defence or direct action protests against police brutality. Others focused on community organizing and building alternative institutions like health clinics or food cooperatives.

The Black Panther Party perhaps the most well-known example of a group that embodied many aspects of Black Power ideology. They advocated for armed self-defence against police brutality while also running programs like free breakfast for children and community health clinics.

Black Power – Goals and Achievements

One major achievement of the Black Power movement was its role in raising awareness about issues facing black Americans and sparking a broader conversation about race relations in America. Activists like Stokely Carmichael and Angela Davis became national figures who brought attention to issues like police brutality, voting rights, and economic inequality.

The Black Power movement also helped build a sense of community among black Americans by promoting cultural pride and celebrating African heritage. This led to the creation of independent schools, businesses, and other institutions that helped foster a sense of empowerment within black communities.

In terms of political achievements, the Black Power movement played a key role in pushing for greater representation for black Americans in government. This included efforts to register voters and run candidates for office at all levels of government.

However, the Black Power movement was met with significant opposition from those who feared its more militant tactics or saw it as a threat to white supremacy. Government agencies like the FBI launched covert operations to disrupt and discredit Black Power groups like the Black Panthers.

Anthropologists Gerlach and Hine (1973) studied the Black Power movement and concluded that it was “a significant turning point in the consciousness of black people in America.” They argued that the movement “brought about a new awareness of black identity and a new sense of pride and empowerment.”

The Legacy of Black Power

The ideas and tactics of Black Power had a significant impact on later movements for social justice, including feminism and LGBTQ rights. One major influence was the concept of intersectionality, which recognizes that different forms of oppression (such as racism, sexism, homophobia) are interconnected and cannot be addressed separately.

Many black feminist activists in the 1970s and 1980s drew on the principles of Black Power to argue for the importance of addressing issues like domestic violence, reproductive rights, and economic inequality within black communities. Similarly, LGBTQ activists have pointed to the legacy of Black Power in advocating for greater visibility and acceptance of queer people of color.

However, there were also criticisms of Black Power from within and outside the movement. Some argued that its emphasis on self-determination could lead to separatism or tribalism rather than true unity across racial lines. Others criticized its more militant tactics, arguing that they could harm innocent people or undermine broader efforts for social change.

The Black Power movement was a critical turning point in the history of race relations in America. While it was often overshadowed by the more mainstream Civil Rights movement, its emphasis on self-determination, cultural pride, and empowerment has had a lasting impact on American society.

By challenging traditional notions of white supremacy and promoting community building and intersectionality, the Black Power movement paved the way for a new era of activism and social change. Today, its legacy continues to inspire activists who seek to challenge systemic racism and create a more equitable society for all

Related terms:

Civil rights movement – a political and social movement that sought to end segregation and discrimination against black people in the United States.

Black nationalism – a political and social movement that seeks to promote the interests of black people.

Militancy – the use of force or the threat of force to achieve a goal.

Global struggle for human rights – a worldwide movement that seeks to protect and promote the rights of all people.

Racism – the belief that one race is superior to another.

Black pride – a feeling of pride and solidarity among black people.

Black self-reliance – the belief that black people should be self-sufficient and not reliant on others.

Anti-discrimination legislation – laws that forbid discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

Gay liberation movement – a political and social movement that sought to end discrimination against and empower gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people.

Black Lives Matter movement – a political and social movement that seeks to end violence and discrimination against black people.

Apartheid – a system of racial segregation and discrimination that was enforced in South Africa from 1948 to 1994.

Disclosure: Please note that some of the links in this post are affiliate links. When you use one of my affiliate links , the company compensates me. At no additional cost to you, I’ll earn a commission, which helps me run this blog and keep my in-depth content free of charge for all my readers.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- International

- Education Jobs

- Schools directory

- Resources Education Jobs Schools directory News Search

Grade 12 History Essay: Black Power Movement USA

Subject: History

Age range: 16+

Resource type: Assessment and revision

Last updated

13 February 2024

- Share through email

- Share through twitter

- Share through linkedin

- Share through facebook

- Share through pinterest

The Black Power Movement Essay explores the historical and social significance of the Black Power Movement that emerged in the 1960s. This essay examines the key ideologies, leaders, and activities that shaped the movement and analyzes its impact on the African American community and the broader civil rights movement.

The essay begins by providing a brief overview of the historical context in which the Black Power Movement emerged, including the Civil Rights Movement and the socio-political climate of the time. It then delves into the core principles of the movement, such as self-determination, racial pride, and the rejection of nonviolence as the sole strategy for achieving racial equality.

The essay explores the influential figures within the Black Power Movement, including Stokely Carmichael, Angela Davis, and Huey P. Newton. It discusses their roles as leaders and their contributions to the movement’s ideology and activism. Additionally, the essay highlights significant events and organizations associated with the movement, such as the Black Panther Party and the National Black Power Conferences.

Furthermore, the essay examines the impact of the Black Power Movement on the African American community and the broader civil rights movement. It analyzes how the movement challenged traditional civil rights strategies and redefined notions of Black identity and empowerment. The essay also discusses the movement’s influence on subsequent activist movements and its lasting legacy in contemporary social and political discourse.

Overall, the Black Power Movement Essay provides a comprehensive analysis of this significant chapter in American history, shedding light on its ideologies, leaders, impact, and lasting relevance in the fight for racial justice and equality.

Tes paid licence How can I reuse this?

Your rating is required to reflect your happiness.

It's good to leave some feedback.

Something went wrong, please try again later.

This resource hasn't been reviewed yet

To ensure quality for our reviews, only customers who have purchased this resource can review it

Report this resource to let us know if it violates our terms and conditions. Our customer service team will review your report and will be in touch.

Not quite what you were looking for? Search by keyword to find the right resource:

Black Power Movement in America Essay (Critical Writing)

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

In America, the beginning of the 1960s was characterized by a number of political and civil movements that were aimed at providing the Black people with rights, freedoms, and opportunities. Regarding the thoughts developed by Malcolm X and Mr. King and the outcomes of their murders, many people did not want to accept the fact that a Black man should not have the rights to power.

The fact that a Black man was deprived of power made people believe that they deserved that right and that they had all possibilities to achieve power and use it as they wished. Black Americans were constantly oppressed, and protests and revolutions turned out to be the only chance to change the situation. Though many Whites admitted that the Blacks promoted hate as the only weapon to demonstrate their intentions ( Eyes on the Prize ), the participants refused that idea underlining that the only strong desire they have is “to live with hope and human dignity that existence without them is impossible” (Newton 5).

The Black Power movement helped to provide people with a sense of racial pride. People had not to be afraid of the color of their skin. All they had to do was to comprehend that the white color is not better than the black color, and there was no person, who could give a clear explanation of why racial diversity should be developed in favor of the Whites. There were a number of attempts to prove the worth of the black nation, and the creation of the Black Panther Party was one of the brightest achievements in the middle of the 1960s.

Huey Newton and Bobby Seale were the founders of the party when they came to the conclusion that there was no other way to deal with white shotguns that spread fear among ordinary black citizens and the instability that deprived people of hope. The idea to create a new political party that could be legally approved was based on casual discussions and conversations (Newton 111). People were in need of something more than the white rooster that represented the Democratic Party, and the elephant that represented the Republican Party.

Now, it was a black cat that spoke for all Black communities ( Eyes on the Prize ). The ideas offered by the Black Panther Party were impressive. It was not enough for them to ask for freedoms, education, employment, etc. It was necessary to prove that the Black community was not worse for the communities organized by the white people, and certain systematic changes were necessary for America.

A ten-point program was developed by the representatives of the Black Panther Party within the frames of which the main ideas and intentions of the Black community were identified. One of the most interesting ideas was the necessity to deal with police brutality and murders of Black people (Newton 120). The organization of self-defense groups was the decision that proved the importance of patrolling.

According to the Second Amendment to the US Constitution, people had the right to bear arms, and Newton used that opportunity to help the Black people protect themselves against the police as “it was ridiculous to report the police to the police, but… by raising encounters to a higher level, by patrolling the police with arms, we would see a change in their behavior” (120). These were the first steps that helped to realize that the Black people could do a lot of things to improve their lives in case they did everything on their own.

Works Cited

Eyes on the Prize . Ex. Prod. Henry Hampton. Boston: Blackside, 1987-1990. Web.

Newton, Huey, P. Revolutionary Suicide , New York: Writers and Readers Publishing, 1995. Print.

- HIV/AIDS Activism in "How to Survive a Plague"

- The Popularity of Subcultures in Our Time

- Black Panthers and Black Lives Matter Movements

- Michelle Obama’s Tuskegee University Commencement Speech

- Response to Panther Film

- AIDS in New York in "How to Survive a Plague" Film

- Harrison Bergeron and Malcolm X as Revolutionaries

- Public Service and Volunteers in American Society

- Black Lives Matter Social Movement and Ideology

- Social Movements and Democracies in Kitschelt's View

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, September 26). Black Power Movement in America. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-power-movement-in-america/

"Black Power Movement in America." IvyPanda , 26 Sept. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/black-power-movement-in-america/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Black Power Movement in America'. 26 September.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Black Power Movement in America." September 26, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-power-movement-in-america/.

1. IvyPanda . "Black Power Movement in America." September 26, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-power-movement-in-america/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Black Power Movement in America." September 26, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-power-movement-in-america/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Social Movements — Black Power Movement

Essays on Black Power Movement

The origins of the black power movement.

The Black Power Movement emerged in the mid-1960s as a response to the ongoing struggle for civil rights and racial equality. An essay on this topic could delve into the historical context that gave rise to the movement, including the impact of the Civil Rights Movement, urbanization, and the influence of prominent leaders such as Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael.

Another essay topic could focus on the ideology and goals of the Black Power Movement, exploring its emphasis on self-determination, community empowerment, and the rejection of assimilationist strategies. This essay could also examine the diversity of perspectives within the movement, including the role of women and LGBTQ individuals.

The Impact of the Black Power Movement on Society and Culture

The Black Power Movement had a profound impact on American society and culture, influencing everything from music and art to politics and education. An essay on this topic could explore how the movement reshaped public perceptions of race, inspired a new generation of activists, and contributed to the emergence of Black Studies programs in universities.

Finally, an essay could examine the lasting legacy of the Black Power Movement and its continued relevance in contemporary discussions of race, power, and activism. This essay could explore how the movement paved the way for future social justice movements, and how its key principles continue to inform debates about racial inequality and systemic oppression.

In addition to these specific essay topics, students may also consider exploring related issues such as the role of the Black Panther Party, the impact of the Black Power Movement on international liberation struggles, and the intersection of race, gender, and class within the movement. By choosing a topic that aligns with their interests and expertise, students can produce a compelling and well-researched essay that contributes to our understanding of this crucial period in American history.

The Black Power Movement offers a wealth of essay topics for students to explore, from its origins and ideology to its impact on society and culture. Students can ensure that their essays reach a wide audience and contribute to ongoing discussions about race, power, and activism. Whether focusing on the historical context of the movement or its contemporary relevance, students have the opportunity to produce insightful and impactful essays that shed light on this pivotal moment in American history.

The Best Black Power Movement Essay Topics for 2024

- The Influence of the Black Power Movement on Contemporary Social Justice Initiatives

- Comparative Analysis of the Civil Rights Movement and the Black Power Movement

- Black Power Movement: Gender, Class, and Power

- The Role of Women in the Black Power Movement

- Black Power and its Impact on African American Art and Culture

- The International Influence of the Black Power Movement on Anti-Colonial Struggles

- Black Power's Impact on African American Community & Empowerment

- Media Representation of the Black Power Movement: Between Demonization and Idealization

- The Evolution of Black Power Ideology: From Civil Rights to Black Lives Matter

- Examining the Legacy of the Black Panther Party within the Black Power Movement

The Black Panther Party as The Leaders of Black Power Movement

Black arts era as the origin of the black power movement, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Presence of Black Theology in Black Power Movement

Relevant topics.

- Civil Disobedience

- Emmett Till

- Me Too Movement

- Montgomery Bus Boycott

- Urbanization

- Arab Spring

- Occupy Wall Street

- Gender Equality

- Human Trafficking

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

African American Heritage

Black Power

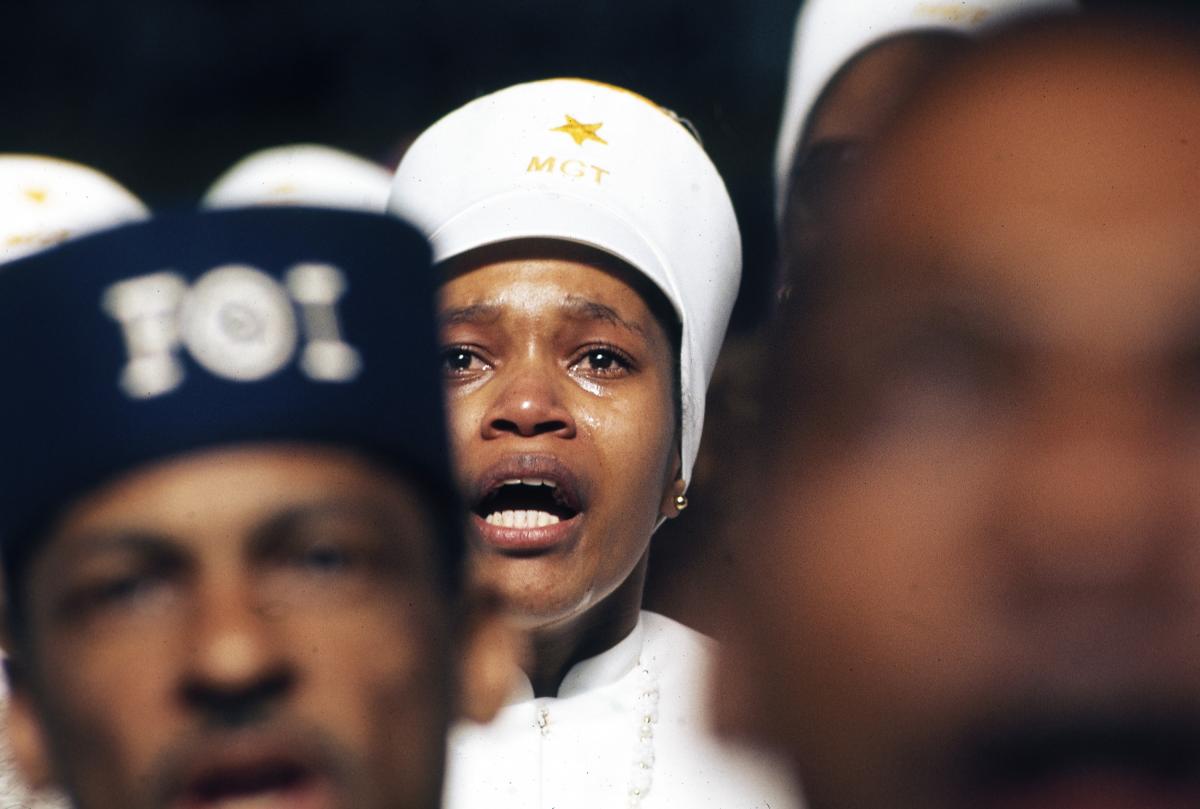

Black Power began as revolutionary movement in the 1960s and 1970s. It emphasized racial pride, economic empowerment, and the creation of political and cultural institutions. During this era, there was a rise in the demand for Black history courses, a greater embrace of African culture, and a spread of raw artistic expression displaying the realities of African Americans.

The term "Black Power" has various origins. Its roots can be traced to author Richard Wright’s non-fiction work Black Power , published in 1954. In 1965, the Lowndes County [Alabama] Freedom Organization (LCFO) used the slogan “Black Power for Black People” for its political candidates. The next year saw Black Power enter the mainstream. During the Meredith March against Fear in Mississippi, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Chairman Stokely Carmichael rallied marchers by chanting “we want Black Power.”

This portal highlights records of Federal agencies and collections that related to the Black Power Movement of the 1960s and 1970s. The selected records contain information on various organizations, including the Nation of Islam (NOI), Deacons for Defense and Justice , and the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPP). It also includes records on several individuals, including Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, Elaine Brown, Angela Davis, Fred Hampton, Amiri Baraka, and Shirley Chisholm. This portal is not meant to be exhaustive, but to provide guidance to researchers interested in the Black Power Movement and its relation to the Federal government.

The records in this guide were created by Federal agencies, therefore, the topics included had some sort of interaction with the United States Government. This subject guide includes textual and electronic records, photographs, moving images, audio recordings, and artifacts. Records can be found at the National Archives at College Park, as well as various presidential libraries and regional archives throughout the country.

A Note on Restrictions and the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

Due to the type of possible content found in series related to Black Power, there may be restrictions associated with access and the use of these records. Several series in RG 60 - Department of Justice (DOJ) and RG 65 - Records of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) may need to be screened for FOIA (b)(1) National Security, FOIA (b)(6) Personal Information, and/or FOIA (b)(7) Law Enforcement prior to public release . Researchers interested in records that contain FOIA restrictions, should consult our Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) page.

Black Arts Movement

Black Panther Party

Congressional Black Caucus

Nation of Islam

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

Women in Black Power

Rediscovering Black History: Blogs on Black Power

National Museum of African American History and Culture: The Foundations of Black Power

Library of Congress, American Folklife Center: Black Power Collections and Repositories

Digital Public Library of America: The Black Power Movement

Columbia University: Malcolm X Project Records, 1968-2008

Revolutionary Movements Then and Now: Black Power and Black Lives Matter, Oct 19, 2016

The people and the police, sep 8, 2016.

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Journal Proposal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Author Biographies

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

On the ethics of mediating embodied vulnerability to violence.

1. Introduction

2. vulnerability to violence as embodiment.

[N]o adequate political theory can ignore the importance of bodies in situating empirical actors within a material environment of nature, other bodies, and the socioeconomic structures that dictate where and how they find sustenance, satisfy their desires, or obtain the resources necessary for participating in political life. (p. 19)

3. Differential Embodied Vulnerabilites in the Media

4. media spectacle, 5. news values versus the ethics of care, 6. ethics of care as invitational rhetoric, 7. religious philosophy and the ethics of care.

both the care ethics tradition and the Tibetan Buddhist tradition recognize how the welfare of all sentient beings is bound together in a vast matrix of cause and condition, and the relationality of these beings are centered as core aspects of relational decision-making in both. (p. 893)

8. Conclusions

Institutional review board statement, data availability statement, conflicts of interest.

- Almond, Kyle, and Brett Roegiers. 2022. The Photos That Have Defined the War in Ukraine. CNN . May 13. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2022/05/world/ukraine-war-photographers-cnnphotos/ (accessed on 29 May 2024).