1.1 The Science of Biology

Learning objectives.

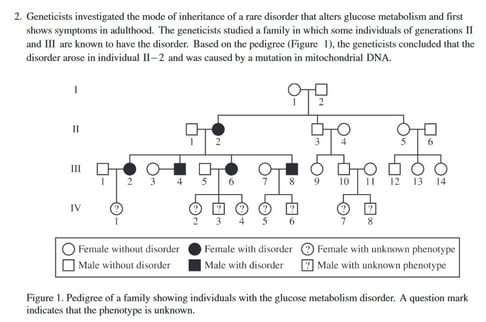

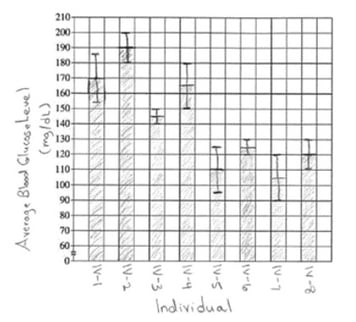

In this section, you will explore the following questions:

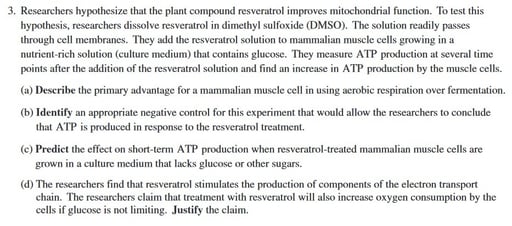

- What are the characteristics shared by the natural sciences?

- What are the steps of the scientific method?

Connection for AP ® courses

Biology is the science that studies living organisms and their interactions with one another and with their environment. The process of science attempts to describe and understand the nature of the universe by rational means. Science has many fields; those fields related to the physical world, including biology, are considered natural sciences. All of the natural sciences follow the laws of chemistry and physics. For example, when studying biology, you must remember living organisms obey the laws of thermodynamics while using free energy and matter from the environment to carry out life processes that are explored in later chapters, such as metabolism and reproduction.

Two types of logical reasoning are used in science: inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning. Inductive reasoning uses particular results to produce general scientific principles. Deductive reasoning uses logical thinking to predict results by applying scientific principles or practices. The scientific method is a step-by-step process that consists of: making observations, defining a problem, posing hypotheses, testing these hypotheses by designing and conducting investigations, and drawing conclusions from data and results. Scientists then communicate their results to the scientific community. Scientific theories are subject to revision as new information is collected.

The content presented in this section supports the Learning Objectives outlined in Big Idea 2 of the AP ® Biology Curriculum Framework. The Learning Objectives merge Essential Knowledge content with one or more of the seven Science Practices. These objectives provide a transparent foundation for the AP ® Biology course, along with inquiry-based laboratory experiences, instructional activities, and AP ® Exam questions.

| Biological systems utilize free energy and molecular building blocks to grow, to reproduce, and to maintain dynamic homeostasis. | |

| Growth, reproduction and maintenance of living systems require free energy and matter. | |

| All living systems require constant input of free energy. | |

| The student can make claims and predictions about natural phenomena based on scientific theories and models | |

| The student is able to predict how changes in free energy availability affect organisms, populations and ecosystems. |

Teacher Support

Illustrate uses of the scientific method in class. Divide students in groups of four or five and ask them to design experiments to test the existence of connections they have wondered about. Help them decide if they have a working hypothesis that can be tested and falsified. Give examples of hypotheses that are not falsifiable because they are based on subjective assessments. They are neither observable nor measurable. For example, birds like classical music is based on a subjective assessment. Ask if this hypothesis can be modified to become a testable hypothesis. Stress the need for controls and provide examples such as the use of placebos in pharmacology.

Biology is not a collection of facts to be memorized. Biological systems follow the law of physics and chemistry. Give as an example gas laws in chemistry and respiration physiology. Many students come with a 19th century view of natural sciences; each discipline is in its own sphere. Give as an example, bioinformatics which uses organism biology, chemistry, and physics to label DNA with light emitting reporter molecules (Next Generation sequencing). These molecules can then be scanned by light-sensing machinery, allowing huge amounts of information to be gathered on their DNA. Bring to their attention the fact that the analysis of these data is an application of mathematics and computer science.

For more information about next generation sequencing, check out this informative review .

What is biology? In simple terms, biology is the study of life. This is a very broad definition because the scope of biology is vast. Biologists may study anything from the microscopic or submicroscopic view of a cell to ecosystems and the whole living planet ( Figure 1.2 ). Listening to the daily news, you will quickly realize how many aspects of biology are discussed every day. For example, recent news topics include Escherichia coli ( Figure 1.3 ) outbreaks in spinach and Salmonella contamination in peanut butter. On a global scale, many researchers are committed to finding ways to protect the planet, solve environmental issues, and reduce the effects of climate change. All of these diverse endeavors are related to different facets of the discipline of biology.

The Process of Science

Biology is a science, but what exactly is science? What does the study of biology share with other scientific disciplines? Science (from the Latin scientia , meaning “knowledge”) can be defined as knowledge that covers general truths or the operation of general laws, especially when acquired and tested by the scientific method. It becomes clear from this definition that the application of the scientific method plays a major role in science. The scientific method is a method of research with defined steps that include experiments and careful observation.

The steps of the scientific method will be examined in detail later, but one of the most important aspects of this method is the testing of hypotheses by means of repeatable experiments. A hypothesis is a suggested explanation for an event, which can be tested. Although using the scientific method is inherent to science, it is inadequate in determining what science is. This is because it is relatively easy to apply the scientific method to disciplines such as physics and chemistry, but when it comes to disciplines like archaeology, psychology, and geology, the scientific method becomes less applicable as it becomes more difficult to repeat experiments.

These areas of study are still sciences, however. Consider archaeology—even though one cannot perform repeatable experiments, hypotheses may still be supported. For instance, an archaeologist can hypothesize that an ancient culture existed based on finding a piece of pottery. Further hypotheses could be made about various characteristics of this culture, and these hypotheses may be found to be correct or false through continued support or contradictions from other findings. A hypothesis may become a verified theory. A theory is a tested and confirmed explanation for observations or phenomena. Science may be better defined as fields of study that attempt to comprehend the nature of the universe.

Natural Sciences

What would you expect to see in a museum of natural sciences? Frogs? Plants? Dinosaur skeletons? Exhibits about how the brain functions? A planetarium? Gems and minerals? Or, maybe all of the above? Science includes such diverse fields as astronomy, biology, computer sciences, geology, logic, physics, chemistry, and mathematics ( Figure 1.4 ). However, those fields of science related to the physical world and its phenomena and processes are considered natural sciences . Thus, a museum of natural sciences might contain any of the items listed above.

There is no complete agreement when it comes to defining what the natural sciences include, however. For some experts, the natural sciences are astronomy, biology, chemistry, earth science, and physics. Other scholars choose to divide natural sciences into life sciences , which study living things and include biology, and physical sciences , which study nonliving matter and include astronomy, geology, physics, and chemistry. Some disciplines such as biophysics and biochemistry build on both life and physical sciences and are interdisciplinary. Natural sciences are sometimes referred to as “hard science” because they rely on the use of quantitative data; social sciences that study society and human behavior are more likely to use qualitative assessments to drive investigations and findings.

Not surprisingly, the natural science of biology has many branches or subdisciplines. Cell biologists study cell structure and function, while biologists who study anatomy investigate the structure of an entire organism. Those biologists studying physiology, however, focus on the internal functioning of an organism. Some areas of biology focus on only particular types of living things. For example, botanists explore plants, while zoologists specialize in animals.

Scientific Reasoning

One thing is common to all forms of science: an ultimate goal “to know.” Curiosity and inquiry are the driving forces for the development of science. Scientists seek to understand the world and the way it operates. To do this, they use two methods of logical thinking: inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning.

Inductive reasoning is a form of logical thinking that uses related observations to arrive at a general conclusion. This type of reasoning is common in descriptive science. A life scientist such as a biologist makes observations and records them. These data can be qualitative or quantitative, and the raw data can be supplemented with drawings, pictures, photos, or videos. From many observations, the scientist can infer conclusions (inductions) based on evidence. Inductive reasoning involves formulating generalizations inferred from careful observation and the analysis of a large amount of data. Brain studies provide an example. In this type of research, many live brains are observed while people are doing a specific activity, such as viewing images of food. The part of the brain that “lights up” during this activity is then predicted to be the part controlling the response to the selected stimulus, in this case, images of food. The “lighting up” of the various areas of the brain is caused by excess absorption of radioactive sugar derivatives by active areas of the brain. The resultant increase in radioactivity is observed by a scanner. Then, researchers can stimulate that part of the brain to see if similar responses result.

Deductive reasoning or deduction is the type of logic used in hypothesis-based science. In deductive reason, the pattern of thinking moves in the opposite direction as compared to inductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning is a form of logical thinking that uses a general principle or law to predict specific results. From those general principles, a scientist can deduce and predict the specific results that would be valid as long as the general principles are valid. Studies in climate change can illustrate this type of reasoning. For example, scientists may predict that if the climate becomes warmer in a particular region, then the distribution of plants and animals should change. These predictions have been made and tested, and many such changes have been found, such as the modification of arable areas for agriculture, with change based on temperature averages.

Both types of logical thinking are related to the two main pathways of scientific study: descriptive science and hypothesis-based science. Descriptive (or discovery) science , which is usually inductive, aims to observe, explore, and discover, while hypothesis-based science , which is usually deductive, begins with a specific question or problem and a potential answer or solution that can be tested. The boundary between these two forms of study is often blurred, and most scientific endeavors combine both approaches. The fuzzy boundary becomes apparent when thinking about how easily observation can lead to specific questions. For example, a gentleman in the 1940s observed that the burr seeds that stuck to his clothes and his dog’s fur had a tiny hook structure. On closer inspection, he discovered that the burrs’ gripping device was more reliable than a zipper. He eventually developed a company and produced the hook-and-loop fastener often used on lace-less sneakers and athletic braces. Descriptive science and hypothesis-based science are in continuous dialogue.

The Scientific Method

Biologists study the living world by posing questions about it and seeking science-based responses. This approach is common to other sciences as well and is often referred to as the scientific method. The scientific method was used even in ancient times, but it was first documented by England’s Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626) ( Figure 1.5 ), who set up inductive methods for scientific inquiry. The scientific method is not exclusively used by biologists but can be applied to almost all fields of study as a logical, rational problem-solving method.

The scientific process typically starts with an observation (often a problem to be solved) that leads to a question. Let’s think about a simple problem that starts with an observation and apply the scientific method to solve the problem. One Monday morning, a student arrives at class and quickly discovers that the classroom is too warm. That is an observation that also describes a problem: the classroom is too warm. The student then asks a question: “Why is the classroom so warm?”

Proposing a Hypothesis

Recall that a hypothesis is a suggested explanation that can be tested. To solve a problem, several hypotheses may be proposed. For example, one hypothesis might be, “The classroom is warm because no one turned on the air conditioning.” But there could be other responses to the question, and therefore other hypotheses may be proposed. A second hypothesis might be, “The classroom is warm because there is a power failure, and so the air conditioning doesn’t work.”

Once a hypothesis has been selected, the student can make a prediction. A prediction is similar to a hypothesis but it typically has the format “If . . . then . . . .” For example, the prediction for the first hypothesis might be, “ If the student turns on the air conditioning, then the classroom will no longer be too warm.”

Testing a Hypothesis

A valid hypothesis must be testable. It should also be falsifiable , meaning that it can be disproven by experimental results. Importantly, science does not claim to “prove” anything because scientific understandings are always subject to modification with further information. This step—openness to disproving ideas—is what distinguishes sciences from non-sciences. The presence of the supernatural, for instance, is neither testable nor falsifiable. To test a hypothesis, a researcher will conduct one or more experiments designed to eliminate one or more of the hypotheses. Each experiment will have one or more variables and one or more controls. A variable is any part of the experiment that can vary or change during the experiment. The control group contains every feature of the experimental group except it is not given the manipulation that is hypothesized about. Therefore, if the results of the experimental group differ from the control group, the difference must be due to the hypothesized manipulation, rather than some outside factor. Look for the variables and controls in the examples that follow. To test the first hypothesis, the student would find out if the air conditioning is on. If the air conditioning is turned on but does not work, there should be another reason, and this hypothesis should be rejected. To test the second hypothesis, the student could check if the lights in the classroom are functional. If so, there is no power failure and this hypothesis should be rejected. Each hypothesis should be tested by carrying out appropriate experiments. Be aware that rejecting one hypothesis does not determine whether or not the other hypotheses can be accepted; it simply eliminates one hypothesis that is not valid ( see this figure ). Using the scientific method, the hypotheses that are inconsistent with experimental data are rejected.

While this “warm classroom” example is based on observational results, other hypotheses and experiments might have clearer controls. For instance, a student might attend class on Monday and realize she had difficulty concentrating on the lecture. One observation to explain this occurrence might be, “When I eat breakfast before class, I am better able to pay attention.” The student could then design an experiment with a control to test this hypothesis.

In hypothesis-based science, specific results are predicted from a general premise. This type of reasoning is called deductive reasoning: deduction proceeds from the general to the particular. But the reverse of the process is also possible: sometimes, scientists reach a general conclusion from a number of specific observations. This type of reasoning is called inductive reasoning, and it proceeds from the particular to the general. Inductive and deductive reasoning are often used in tandem to advance scientific knowledge ( see this figure ). In recent years a new approach of testing hypotheses has developed as a result of an exponential growth of data deposited in various databases. Using computer algorithms and statistical analyses of data in databases, a new field of so-called "data research" (also referred to as "in silico" research) provides new methods of data analyses and their interpretation. This will increase the demand for specialists in both biology and computer science, a promising career opportunity.

Science Practice Connection for AP® Courses

Think about it.

Almost all plants use water, carbon dioxide, and energy from the sun to make sugars. Think about what would happen to plants that don’t have sunlight as an energy source or sufficient water. What would happen to organisms that depend on those plants for their own survival?

Make a prediction about what would happen to the organisms living in a rain forest if 50% of its trees were destroyed. How would you test your prediction?

Use this example as a model to make predictions. Emphasize there is no rigid scientific method scheme. Active science is a combination of observations and measurement. Offer the example of ecology where the conventional scientific method is not always applicable because researchers cannot always set experiments in a laboratory and control all the variables.

Possible answers:

Destruction of the rain forest affects the trees, the animals which feed on the vegetation, take shelter on the trees, and large predators which feed on smaller animals. Furthermore, because the trees positively affect rain through massive evaporation and condensation of water vapor, drought follows deforestation.

Tell students a similar experiment on a grand scale may have happened in the past and introduce the next activity “What killed the dinosaurs?”

Some predictions can be made and later observations can support or disprove the prediction.

Ask, “what killed the dinosaurs?” Explain many scientists point to a massive asteroid crashing in the Yucatan peninsula in Mexico. One of the effects was the creation of smoke clouds and debris that blocked the Sun, stamped out many plants and, consequently, brought mass extinction. As is common in the scientific community, many other researchers offer divergent explanations.

Go to this site for a good example of the complexity of scientific method and scientific debate.

Visual Connection

In the example below, the scientific method is used to solve an everyday problem. Order the scientific method steps (numbered items) with the process of solving the everyday problem (lettered items). Based on the results of the experiment, is the hypothesis correct? If it is incorrect, propose some alternative hypotheses.

| Scientific Method | Everyday process | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Observation | A | There is something wrong with the electrical outlet. |

| 2 | Question | B | If something is wrong with the outlet, my coffeemaker also won’t work when plugged into it. |

| 3 | Hypothesis (answer) | C | My toaster doesn’t toast my bread. |

| 4 | Prediction | D | I plug my coffee maker into the outlet. |

| 5 | Experiment | E | My coffeemaker works. |

| 6 | Result | F | What is preventing my toaster from working? |

- The original hypothesis is correct. There is something wrong with the electrical outlet and therefore the toaster doesn’t work.

- The original hypothesis is incorrect. Alternative hypothesis includes that toaster wasn’t turned on.

- The original hypothesis is correct. The coffee maker and the toaster do not work when plugged into the outlet.

- The original hypothesis is incorrect. Alternative hypotheses includes that both coffee maker and toaster were broken.

- All flying birds and insects have wings. Birds and insects flap their wings as they move through the air. Therefore, wings enable flight.

- Insects generally survive mild winters better than harsh ones. Therefore, insect pests will become more problematic if global temperatures increase.

- Chromosomes, the carriers of DNA, are distributed evenly between the daughter cells during cell division. Therefore, each daughter cell will have the same chromosome set as the mother cell.

- Animals as diverse as humans, insects, and wolves all exhibit social behavior. Therefore, social behavior must have an evolutionary advantage.

- 1- Inductive, 2- Deductive, 3- Deductive, 4- Inductive

- 1- Deductive, 2- Inductive, 3- Deductive, 4- Inductive

- 1- Inductive, 2- Deductive, 3- Inductive, 4- Deductive

- 1- Inductive, 2-Inductive, 3- Inductive, 4- Deductive

The scientific method may seem too rigid and structured. It is important to keep in mind that, although scientists often follow this sequence, there is flexibility. Sometimes an experiment leads to conclusions that favor a change in approach; often, an experiment brings entirely new scientific questions to the puzzle. Many times, science does not operate in a linear fashion; instead, scientists continually draw inferences and make generalizations, finding patterns as their research proceeds. Scientific reasoning is more complex than the scientific method alone suggests. Notice, too, that the scientific method can be applied to solving problems that aren’t necessarily scientific in nature.

Two Types of Science: Basic Science and Applied Science

The scientific community has been debating for the last few decades about the value of different types of science. Is it valuable to pursue science for the sake of simply gaining knowledge, or does scientific knowledge only have worth if we can apply it to solving a specific problem or to bettering our lives? This question focuses on the differences between two types of science: basic science and applied science.

Basic science or “pure” science seeks to expand knowledge regardless of the short-term application of that knowledge. It is not focused on developing a product or a service of immediate public or commercial value. The immediate goal of basic science is knowledge for knowledge’s sake, though this does not mean that, in the end, it may not result in a practical application.

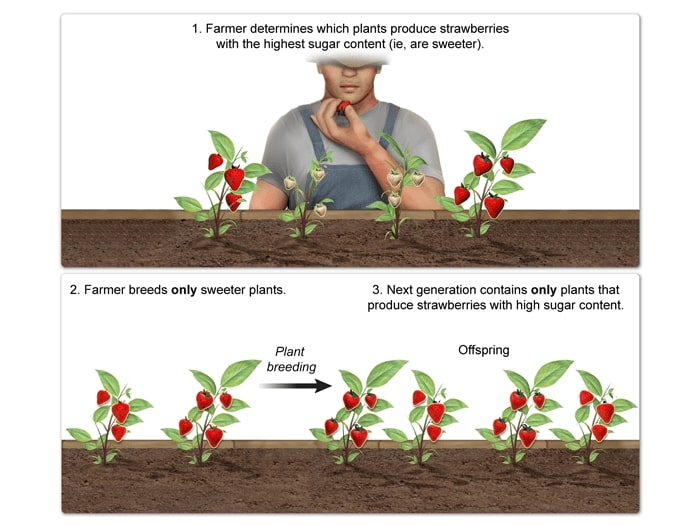

In contrast, applied science or “technology,” aims to use science to solve real-world problems, making it possible, for example, to improve a crop yield, find a cure for a particular disease, or save animals threatened by a natural disaster ( Figure 1.8 ). In applied science, the problem is usually defined for the researcher.

Some individuals may perceive applied science as “useful” and basic science as “useless.” A question these people might pose to a scientist advocating knowledge acquisition would be, “What for?” A careful look at the history of science, however, reveals that basic knowledge has resulted in many remarkable applications of great value. Many scientists think that a basic understanding of science is necessary before an application is developed; therefore, applied science relies on the results generated through basic science. Other scientists think that it is time to move on from basic science and instead to find solutions to actual problems. Both approaches are valid. It is true that there are problems that demand immediate attention; however, few solutions would be found without the help of the wide knowledge foundation generated through basic science.

One example of how basic and applied science can work together to solve practical problems occurred after the discovery of DNA structure led to an understanding of the molecular mechanisms governing DNA replication. Strands of DNA, unique in every human, are found in our cells, where they provide the instructions necessary for life. During DNA replication, DNA makes new copies of itself, shortly before a cell divides. Understanding the mechanisms of DNA replication enabled scientists to develop laboratory techniques that are now used to identify genetic diseases. Without basic science, it is unlikely that applied science could exist.

Another example of the link between basic and applied research is the Human Genome Project, a study in which each human chromosome was analyzed and mapped to determine the precise sequence of DNA subunits and the exact location of each gene. (The gene is the basic unit of heredity represented by a specific DNA segment that codes for a functional molecule.) Other less complex organisms have also been studied as part of this project in order to gain a better understanding of human chromosomes. The Human Genome Project ( Figure 1.9 ) relied on basic research carried out with simple organisms and, later, with the human genome. An important end goal eventually became using the data for applied research, seeking cures and early diagnoses for genetically related diseases.

While research efforts in both basic science and applied science are usually carefully planned, it is important to note that some discoveries are made by serendipity , that is, by means of a fortunate accident or a lucky surprise. Penicillin was discovered when biologist Alexander Fleming accidentally left a petri dish of Staphylococcus bacteria open. An unwanted mold grew on the dish, killing the bacteria. The mold turned out to be Penicillium , and a new antibiotic was discovered. Even in the highly organized world of science, luck—when combined with an observant, curious mind—can lead to unexpected breakthroughs.

Reporting Scientific Work

Whether scientific research is basic science or applied science, scientists must share their findings in order for other researchers to expand and build upon their discoveries. Collaboration with other scientists—when planning, conducting, and analyzing results—is important for scientific research. For this reason, important aspects of a scientist’s work are communicating with peers and disseminating results to peers. Scientists can share results by presenting them at a scientific meeting or conference, but this approach can reach only the select few who are present. Instead, most scientists present their results in peer-reviewed manuscripts that are published in scientific journals. Peer-reviewed manuscripts are scientific papers that are reviewed by a scientist’s colleagues, or peers. These colleagues are qualified individuals, often experts in the same research area, who judge whether or not the scientist’s work is suitable for publication. The process of peer review helps to ensure that the research described in a scientific paper or grant proposal is original, significant, logical, and thorough. Grant proposals, which are requests for research funding, are also subject to peer review. Scientists publish their work so other scientists can reproduce their experiments under similar or different conditions to expand on the findings.

A scientific paper is very different from creative writing. Although creativity is required to design experiments, there are fixed guidelines when it comes to presenting scientific results. First, scientific writing must be brief, concise, and accurate. A scientific paper needs to be succinct but detailed enough to allow peers to reproduce the experiments.

The scientific paper consists of several specific sections—introduction, materials and methods, results, and discussion. This structure is sometimes called the “IMRaD” format. There are usually acknowledgment and reference sections as well as an abstract (a concise summary) at the beginning of the paper. There might be additional sections depending on the type of paper and the journal where it will be published; for example, some review papers require an outline.

The introduction starts with brief, but broad, background information about what is known in the field. A good introduction also gives the rationale of the work; it justifies the work carried out and also briefly mentions the end of the paper, where the hypothesis or research question driving the research will be presented. The introduction refers to the published scientific work of others and therefore requires citations following the style of the journal. Using the work or ideas of others without proper citation is considered plagiarism .

The materials and methods section includes a complete and accurate description of the substances used, and the method and techniques used by the researchers to gather data. The description should be thorough enough to allow another researcher to repeat the experiment and obtain similar results, but it does not have to be verbose. This section will also include information on how measurements were made and what types of calculations and statistical analyses were used to examine raw data. Although the materials and methods section gives an accurate description of the experiments, it does not discuss them.

Some journals require a results section followed by a discussion section, but it is more common to combine both. If the journal does not allow the combination of both sections, the results section simply narrates the findings without any further interpretation. The results are presented by means of tables or graphs, but no duplicate information should be presented. In the discussion section, the researcher will interpret the results, describe how variables may be related, and attempt to explain the observations. It is indispensable to conduct an extensive literature search to put the results in the context of previously published scientific research. Therefore, proper citations are included in this section as well.

Finally, the conclusion section summarizes the importance of the experimental findings. While the scientific paper almost certainly answered one or more scientific questions that were stated, any good research should lead to more questions. Therefore, a well-done scientific paper leaves doors open for the researcher and others to continue and expand on the findings.

Review articles do not follow the IMRAD format because they do not present original scientific findings, or primary literature; instead, they summarize and comment on findings that were published as primary literature and typically include extensive reference sections.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/biology-ap-courses/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Julianne Zedalis, John Eggebrecht

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Biology for AP® Courses

- Publication date: Mar 8, 2018

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/biology-ap-courses/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/biology-ap-courses/pages/1-1-the-science-of-biology

© Apr 26, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

AP® Biology

The best ap® biology review guide for 2024.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: January 23, 2024

Are you planning on taking the AP® Biology exam? If so, let’s get you prepared in this AP® Biology review by learning more about the exam and how to study so that you can feel confident and earn your best score and, potentially, college credit.

The AP® Biology exam is graded on a scale of 1-5, and you can earn college credits at many colleges for receiving a score as low as a 3, which is estimated to be approximately equivalent to earning a C, C+, or B- in a college-level biology course. However, there is quite a bit of variation between colleges in what test scores they will award credit for, if any, so be sure to check with the specific colleges you are interested in to see what score(s) they accept.

In this AP® Biology review post, we’ll go over key questions you may have about the exam, how to study for AP® Biology, and how to review and use AP® Biology exam practice resources, including AP® Biology practice tests, as you begin preparing for your exam.

Are you ready? Let’s get started.

What We Review

What’s the Format of the 2024 AP® Biology Exam?

The AP® Biology exam is composed of two sections: multiple choice and free response. There are 60 multiple-choice questions and 6 free-response questions (2 long-answer questions and 4 short-answer questions).

| I: Multiple Choice | 60 | 90 minutes | 50% |

| II: Free Response | 6 | 90 minutes | 50% |

All AP® Biology exams will be taken with paper and pencil, not on computers.

How Long is the AP® Biology Exam?

The AP® Biology exam is a 3-hour exam. Students will have 90 minutes to complete 60 multiple-choice questions and another 90 minutes to complete 6 free-response questions.

How Many Questions Does AP® Biology Have?

The AP® Biology exam has 60 multiple-choice questions and 6 free-response questions. Of the 6 free-response questions, 4 are short-answer questions, while the other 2 are long-answer questions.

What Topics are Covered on AP® Biology?

There are two types of questions on the AP® Biology exam: multiple choice and free response.

Section I: Multiple-Choice

The AP® Biology exam multiple choice section assesses both content knowledge and science practices , with questions designed to do both. These multiple-choice questions may be either individual or in sets of four to five questions per set.

The content knowledge within the eight different course units is broken down into four big ideas , with learning objectives related to each:

- Evolution (EVO)

- Energetics (ENE)

- Information Storage and Transmission (IST)

- Systems Interactions (SYI)

Questions within each content area, with the relevant learning objectives addressed, are weighted in the multiple choice section as shown; resources for study, AP® Biology review, and AP® Biology exam practice for each section are also provided. You can use this to make an AP® Biology study guide.

| Unit 1: Chemistry of Life | 8-11% |

|

| Unit 2: Cell Structure and Function | 10-13% |

|

| | 12-16% |

|

| | 10-15% |

|

| | 8-11% |

|

| Unit 6: Gene Expression and Regulation | 12-16% |

|

| : all domains of life, which provide evidence of common ancestry. h. | 13-20% |

|

| | 10-15% |

|

Source: College Board

Return to the Table of Contents

While no units are specifically devoted to prokaryotes and viruses, a basic understanding of prokaryotic and virus structure, evolution, ecology, and diversity will be helpful since prokaryotic and eukaryotic mechanisms are compared in various units. Thus, we recommend that you review this information as well.

The six different science practices are divided into skills and are also assessed in the multiple choice section and weighted as shown:

| Explain biological concepts, processes, and models presented in written format.

| 25-33% |

| Analyze visual representations of biological concepts and processes.

| 16-24% |

| Determine scientific questions and methods.

| 8-14% |

| Represent and describe data. ). | 8-14% |

| Perform statistical tests and mathematical calculations to analyze and interpret data.

| 8-14% |

| Develop and justify scientific arguments using evidence.

| 20-26% |

You can also get AP® Biology exam practice in both the science practice and content knowledge by completing the Albert practice questions associated with each of the 13 lab activities.

Section II: Free Response

The AP® Biology free response questions are also designed to assess both content knowledge and science practices and are organized around the science practices and the four big ideas for the course.

The free-response questions are designed as follows, with each of the short-answer questions also assessing one of the four big ideas:

| #1: Long-Answer: gives an authentic scenario with data table or graph | |

| #2: Long-Answer: gives an authentic scenario with data table | |

| #3: Short-Answer: describes a lab investigation scenario | |

| #4: Short-Answer: gives an authentic scenario describing biological phenomenon with a disruption | |

| #5: Short-Answer: give an authentic scenario with visual model or representation | |

| #6: Short-Answer: gives data in a graph, table, or other visual representation |

You will be provided an AP® Biology Equations and Formulas Sheet that you may use on either section of the exam. You are also permitted to use a four-function, scientific, or graphing calculator throughout the exam.

Return to the Table of Contents

What Do AP® Biology Questions Look Like?

Because taking an exam is a skill, completing AP® Biology exam practice questions and then reviewing the answers carefully is a great way to prepare for the AP® Biology exam so that you are not caught off guard by any content or question formats. The AP® Biology Course and Exam Description (CED) for AP® Biology from the College Board provides 15 multiple-choice practice questions and correct answers that address content knowledge from all eight units as well as skills from all six science practices.

The CED for AP® Biology also provides two practice free-response questions (one long-answer question and one short-answer question) with detailed grading rubrics. The College Board has also released the free-response questions with scoring guidelines from the last 20+ years’ worth of exams. The College Board has also released a complete practice exam with answers based upon the 2013 exam . Albert also provides a wide variety of both AP® Biology exam practice multiple-choice and free-response questions and answers, as well as unit assessments and complete AP® Biology practice tests .

Multiple-Choice Examples

Here are some examples of the types of multiple-choice questions you may see, as well as the correct answer, unit(s), and science practice(s) that each question (or question set) assesses.

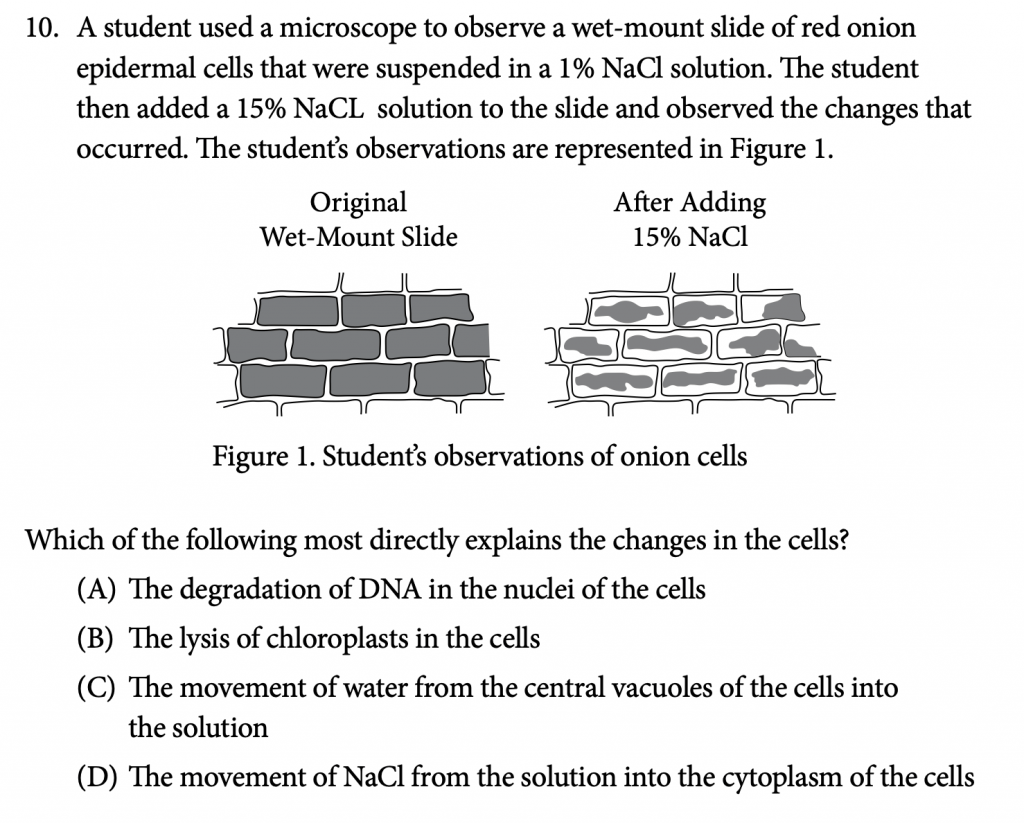

Example #1:

AP® Biology Course and Exam Description (CED)

Correct Answer: C

This question challenges students on one core principle and one science practice.

For Unit 2 (Cell Structure and Function), you should flag the topic of tonicity and osmoregulation as important.

For Science Practice 2 (Visual Representations), you should flag the following as important:

- Explain relationships between different characteristics of biological concepts, processes, or models represented visually in applied contexts.

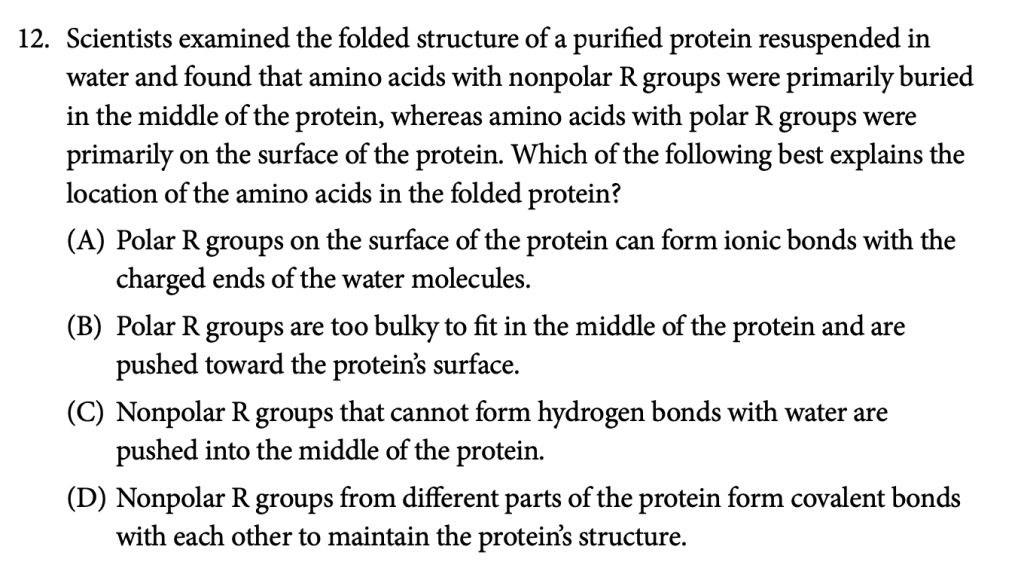

Example #2:

For Unit 1 (Chemistry of Life), you should flag the topic of properties of biological macromolecules as important.

For Science Practice 1 (Concept Explanation), you should flag the following as important:

- Explain biological concepts and/or processes.

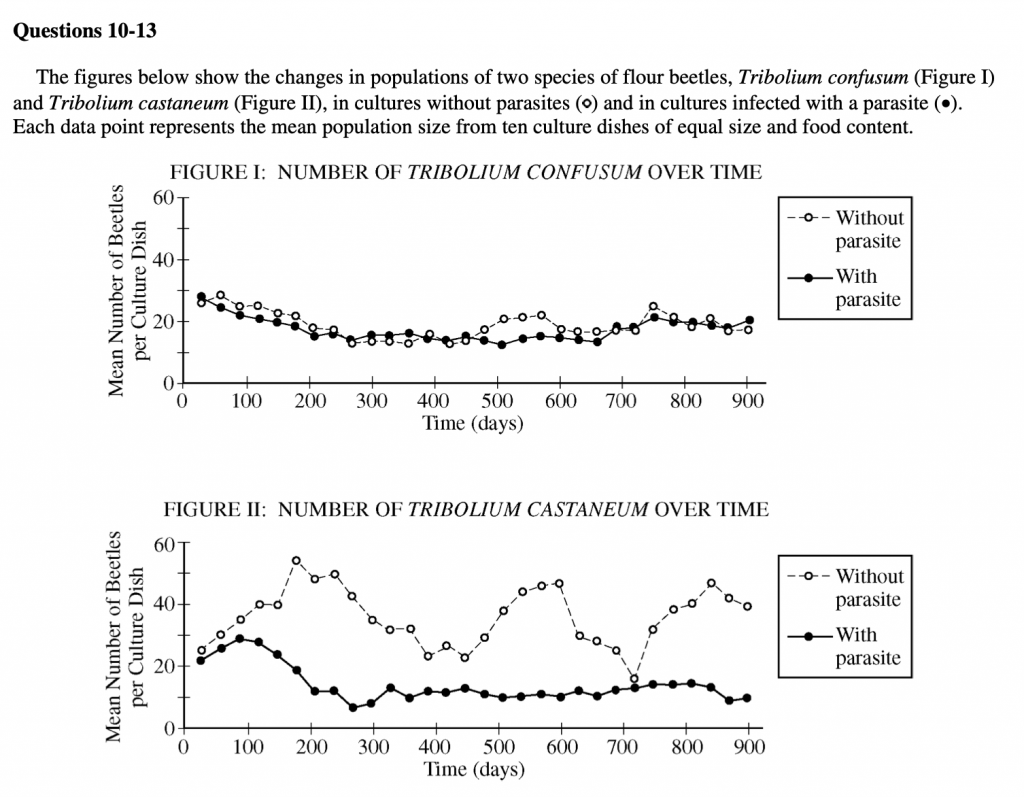

AP® Biology Practice Test from the 2013 Administration – MC Examples #10-13

Examples #3-6

Correct Answer #10: C

Correct Answer #11: B

Correct Answer #12: D

Correct Answer #13: B

These questions challenge students on one core principle and two science practices.

For Unit 8 (Ecology), you should flag the topic of population ecology as important.

For Science Practice 6 (Argumentation), you should flag the following as important:

- Support a claim with evidence from biological principles, concepts, processes, and/or data.

- Provide reasoning to justify a claim by connecting evidence to biological theories.

- Predict the causes or effects of a change in, or disruption to, one or more components in a biological system based on data.

Free-Response Examples

Note that the specific focus of each free-response question is more targeted than in years past.

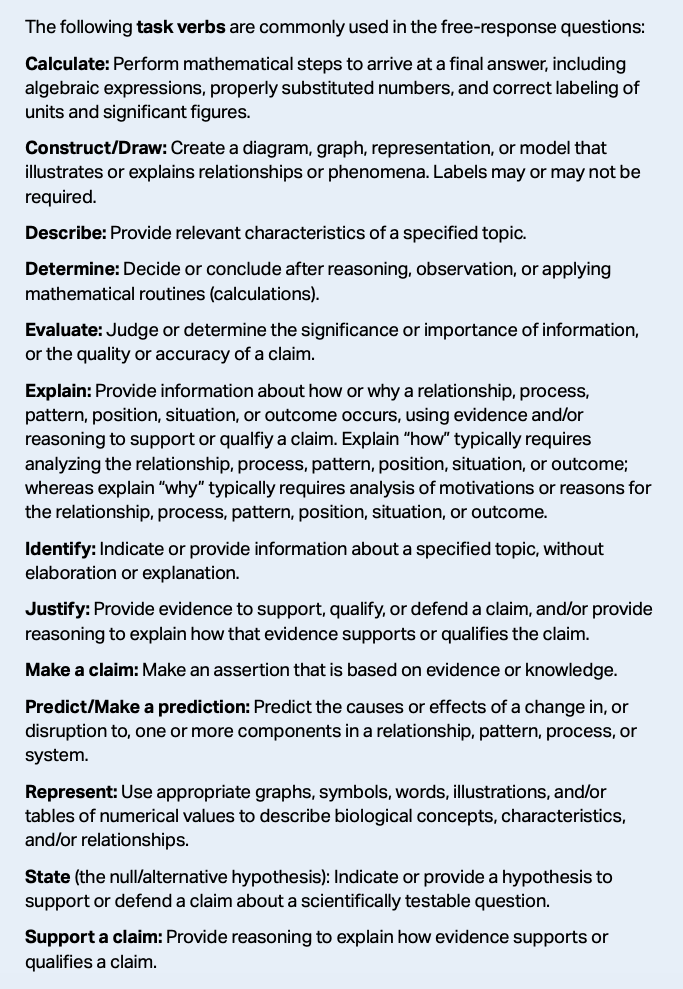

When writing answers to free-response questions, be sure to write your answers in the designated space only and in complete paragraphs. Bulleted lists, outlines, and diagrams without explanation are not acceptable and will not be graded. Also be sure that you well understand the various task verbs used, as explained in the AP® Biology Course and Exam Description (CED) .

Here are two examples of the types of free response questions you may see, as well as the correct answer, scoring rubric, and commentary for each question. The unit(s), and science practice(s) that each question assesses is also provided. One long-answer question and one short-answer question are shown.

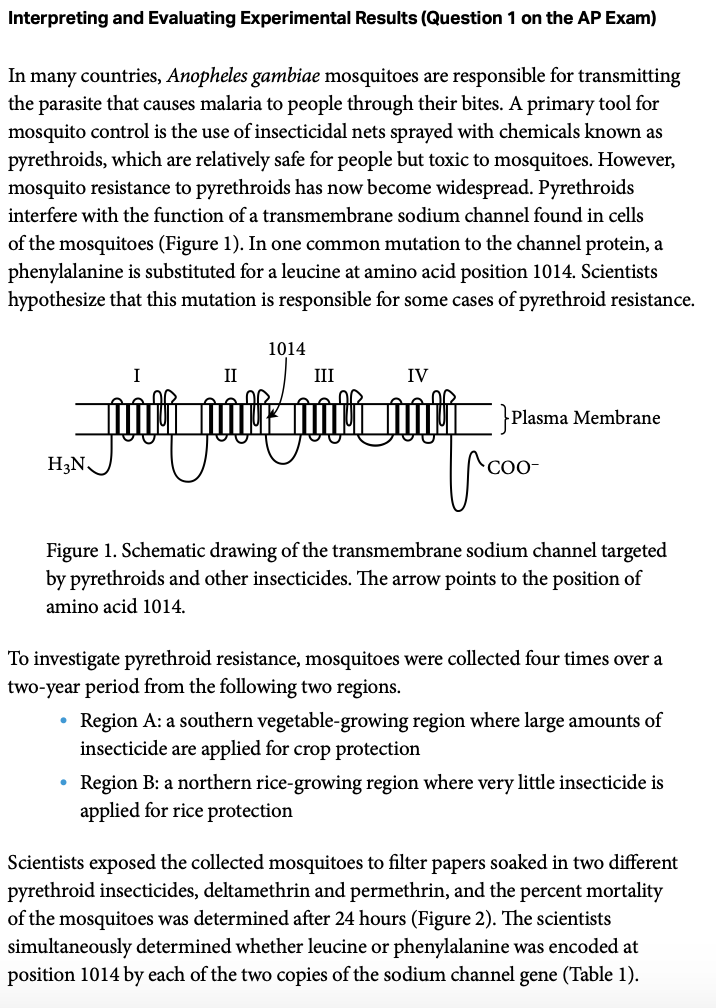

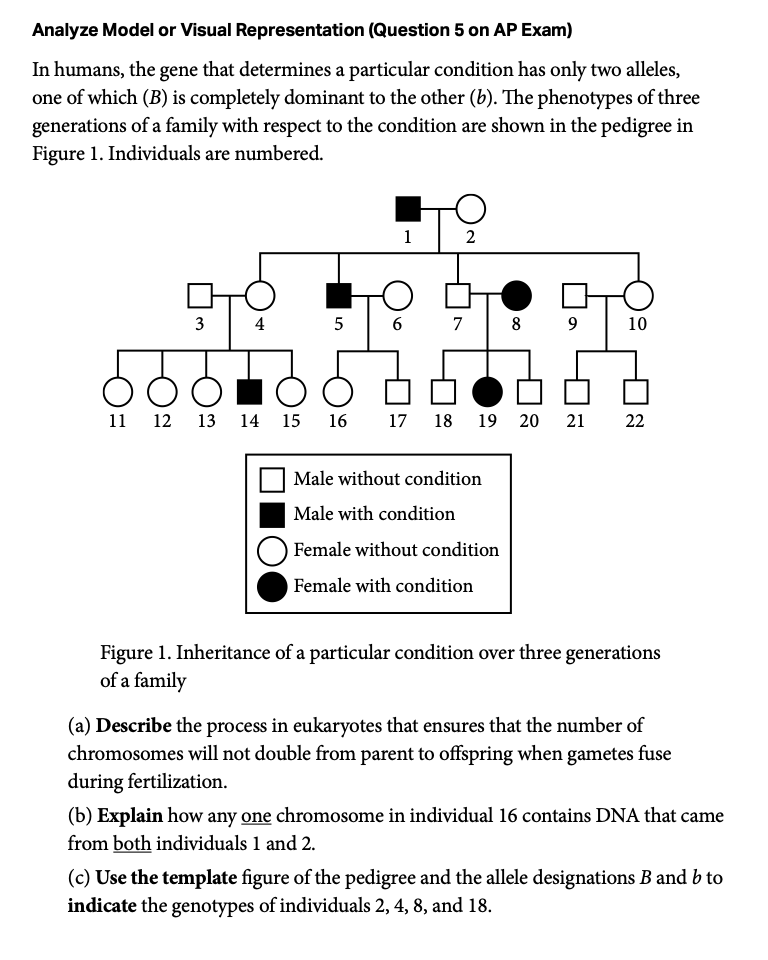

Example #1: AP® Biology Long-Answer Free-Response:

Carefully review the scoring rubric provided for this question.

This question challenges students on three core principles: Natural Selection (Unit 7), Gene Expression and Regulation (Unit 6), and the Chemistry of Life (Unit 1).

Here’s the content that you should flag as important from this question:

- Unit 7: Natural Selection, Population Genetics, and Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium

- Unit 6: Mutations

- Unit 1: Structure and Function of Macromolecules

This question also covers 4 of the science practices: Concept Explanation (Science Practice 1), Questions and Methods (Science Practice 3), Representing and Describing Data (Science Practice 4), Statistical Tests and Data Analysis (Science Practice 5).

Here are the science practices that you should flag as important from this question:

Science Practice 1: Concept Explanation:

- Describe biological concepts and/or processes.

- Explain biological concepts, processes, and/or models in applied contexts.

Science Practice 3: Questions and Methods:

- Identify experimental procedures that are aligned to the question

Science Practice 4: Representing and Describing Data:

- Describe data from a table or graph.

- Science Practice 5: Statistical Tests and Data Analysis: Perform mathematical calculations.

- Science Practice 6: Argumentation: Support a claim with evidence from biological principles, concepts, processes, and/or data.

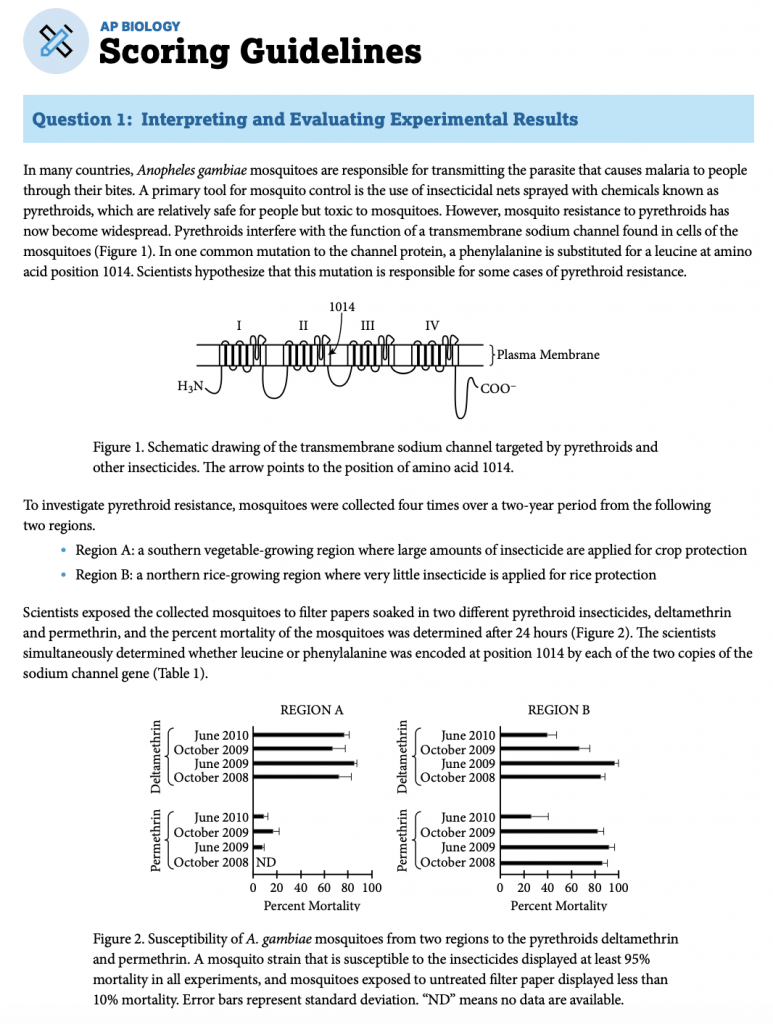

Example #2: AP® Biology Short-Answer Free-Response:

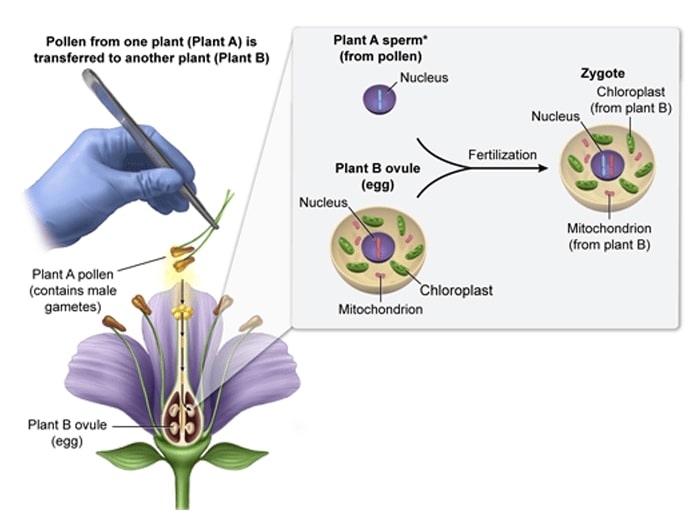

This question challenges students on one core principle, Heredity (Unit 5).

- Unit 5: Meiosis and Genetic Diversity, Mendelian Genetics

- Science Practice 1: Concept Explanation: Describe biological concepts and/or processes.

- Science Practice 2: Visual Representations: Explain relationships between different characteristics of biological concepts, processes, or models represented visually

What Can You Bring to the AP® Biology Exam?

Make sure you arrive at least 15 minutes early at your testing location.

The College Board is rather specific about what you can and cannot bring to the AP® Biology exam. You are at risk of having your score not count if you do not carefully follow instructions. We recommend that you carefully review these guidelines and pack your bag the night before so that you do not have any additional stress on the morning of the exam.

What You Should Bring to Your AP® Biology Exam :

You should bring:

- At least 2 sharpened No. 2 pencils for completing the multiple-choice section.

- At least 2 pens with black or blue ink only. These are used to complete certain areas of your exam booklet covers and to write your free-response questions. The College Board is very specific that pens should be in black or blue ink only, so please double-check!

- A four-function, scientific, or graphing calculator to use on both the multiple-choice and free-response sections of the exam. You may actually bring two calculators. Calculators cannot connect to the internet, make noise, or have a stylus or keyboard. For more information about acceptable versus unacceptable calculators, look here .

- If you do not attend the school where you are taking an exam, you must bring a government-issued or school-issued photo ID.

- If you receive any testing accommodations , be sure that you bring your College Board SSD Accommodations Letter.

What You Should NOT Bring to Your AP® Biology Exam:

You should not bring:

- smartwatches and other wearable technology (including watches that beep or have alarms)

- separate timers

- devices that access the internet or communicate in any way

- Mechanical pencils, colored pencils, or pens that do not have black/blue ink

- Your own scratch paper

- Reference guides (note that you will be provided with an AP® Biology Equations and Formulas Sheet )

- Food or drink, including bottled water, are not permitted in the test room, but are permitted in the break room

How to Study for AP® Biology: 5 Steps to Get a 5

1. Take an AP® Biology practice test. (3 hours)

Identify your areas of strength as well as focus areas for review by taking an Albert AP® Biology practice test . Be sure to have a four-function, scientific, or graphing calculator to use.

2. Make a schedule. (1 hour)

Determine your exam date and format. Then, start preparing early, giving yourself at least two months if possible. After taking an Albert AP® Biology practice test to identify areas for study, make a schedule, giving yourself at least a week for each content unit on your AP® Biology study guide.

- While you should prioritize material where you struggle, spending at least a week on each unit, also review those units you know better for at least 2-3 days each to stay sharp so that you can answer these questions quickly.

- If you are running short on study time, prioritize Units 3, 6, and 7 since these are the most heavily weighted on the exam, and spend less time reviewing Units 1 and 5 since these will be covered the least.

3. Review challenging concepts using your resources and build your AP® Biology study guide. (2-5 hours)

Use your high school textbook and notes and other accessible materials (like OpenStax Biology , Khan Academy , or CK-12 ) for AP® Biology review of the various content areas. As you review each chapter, build your AP® Biology study guide, the outline of which has already been provided above, to include important key words and concepts for each unit.

4. Use AP® Biology exam practice resources. (20-25 hours)

The best way to become effective at test-taking is by answering lots and lots of AP® Biology exam practice questions because practice makes perfect!

Use the AP® Biology exam practice questions provided by the College Board , the Albert AP® Biology exam practice questions for each unit, as well as unit assessments to support your study.

5. Get more AP® Biology exam practice. (3 hours)

After completing steps 1-4, take another Albert AP® Biology practice test to identify content areas that require more review.

AP® Biology Review: 15 Must-Know Study Tips

5 AP® Biology Study Tips to Do at Home:

1. be consistent..

Devote time to studying and preparing daily. Even if it is just a few minutes on some days when you are busy, be sure to study each and every day.

2. Use an app like Quizlet for studying key terms.

There are already a bunch flashcards and study guides preloaded into Quizlet (vocab lists from your textbook may already be available), or you can easily make your own. Then, you can be reviewing key terms and studying whenever you have a few free moments (like standing in line at the store, riding the bus, etc.). If this doesn’t work for you, you can still make flashcards the old-fashioned way using index cards.

3. Remove distractions.

It is easy to become distracted during studying by texting, SnapChats, e-mailing, listening to music, etc. Unfortunately, multitasking is ineffective; it takes about 25 minutes to return to a task after a distraction. Therefore, you can be much more time efficient and productive if you study distraction-free.

4. Study with a buddy.

It can be helpful to meet and study with a friend periodically. It can be helpful to talk out concepts from your AP® Biology study guide with each other because they might describe it differently and in a way that you more easily understand. Additionally, having regular appointments to do so can help to hold you accountable to get through your study plan at a regular pace and not slack off. However, while you can also schedule in time for fun and hanging out after your study appointments, make sure that your planned study time is focused on actual studying.

5. Learn how to use your calculator.

Remember that you cannot use your phone as a calculator on the AP® Biology exam. Therefore, make sure that you have a calculator that meets the requirements and that you know how to use it. Practice using it as you complete AP® Biology exam practice questions and AP® Biology practice tests. The first time you use it should NOT be during the AP® Biology exam.

5 AP® Biology Multiple Choice Study Tips:

1. pace yourself. .

You will have 90 minutes to complete 60 multiple choice questions on the AP® Biology exam. Thus, you should spend no more than 2 minutes on any one question during your first pass through the questions (this assumes that you will move more quickly through other questions). If you get stuck, mark the question, eliminating any answer choices you can, and move on. Then, come back later after you have completed all other questions. Make sure you fill in an answer for each question.

2. Imagine the correct answer.

After carefully reading a question, come up with a mental image of an answer before examining the answer choices. Choose an answer that matches your mental image and then justify your choice. Then, justify why you eliminated each of the other choices. If you cannot choose an answer, eliminate as many as possible, then make your best choice. When using the Albert AP® Biology Practice questions , carefully read the explanations of both the correct and incorrect choices, even if you got the answer correct.

3. Carefully examine any visual materials provided.

Make sure you examine any labels, titles, axes, and legends on tables, graphs, figures, or any other types of images so that you have a clear understanding of how to interpret the visual materials provided in order to answer the questions associated with these materials.

4. Be ready to handle questions that are grouped as sets.

While many of the multiple choice questions are individual, you should expect a few sets of 2-4 questions. Make sure you know which questions are included as a question set. Questions within a set are all typically associated with one or more figures or tables. While these questions are related, don’t give up if you don’t know the answer to the first question. Each question can typically be answered independently of the others within the set.

5. Check your work.

If possible, plan to use at least 10-15 minutes of the exam time to check your work. First, return to any questions that you found difficult to compete on the first pass, being sure to select an answer. Then, review your answers to all of the questions, ensuring that you have answered each and every question.

5 AP® Biology Free Response Study Tips:

1. keep track of time..

You will have 90 minutes to complete the 6 free response questions on the AP® Biology exam. Because each of the two long-answer questions are more extensive and together are worth over half of the free response section (10 points each), you should plan to spend about 20 minutes on each. Then, spend no more than 10 minute on each of the four short-answer questions (worth 4 points each). Use any remaining time to review your answers, making sure they are complete.

2. Make sure you understand the scoring rubrics.

The College Board has provided a clear scoring rubric for each of the six free response questions (provided above, from the AP® Biology Course and Exam Description (CED) ). Be sure that you are writing your answers with these rubrics in mind, fully addressing each part. Additionally, within the AP® Biology Course and Exam Description (CED) ), the College Board has also provided detailed scoring guidelines (also provided above) for both a long-answer question and short-answer question. Review these carefully, making sure you understand what is required to earn each and every point. While the College Board has also provided the scoring guidelines for the many free response questions from past exams that they have made available for practice, as well as Chief Reader Reports from past exams that summarize both how students performed on a particular question and what the readers were looking for, remember that the focus of the free response questions on the 2021 AP® Biology exam is different than in years past, so these examples will be slightly different than what you will see when you take the exam.

3. Focus on the verbs.

For each question, focus on its verbs and other clarifying words. Underline or circle each bolded word as well as other key words. Make sure you understand what each task verb is asking you to do. Review the list of AP® task verbs provided above.

4. Write in complete sentences and paragraphs.

The directions for the free response section clearly state that “outlines, bulleted lists, or diagrams alone are not acceptable and will not be scored”. Thus, make sure to write your answers in complete sentences and organize your thoughts into paragraphs, using the space provided for each question.

5. Ensure that you follow these 5 must-dos to answer each question completely:

- It is common for students to restate the question as they answer a free response question, but this is not necessary and is a waste of precious time. Instead, focus on directly answering what the question is asking. Past Chief Reader Reports from the College Board recommend careful reading and addressing of the prompt.

- The free-response questions are commonly broken into parts. Make sure that you answer each part. Additionally, make sure that you are actually answering what each question is asking.

- If a calculation is required, be sure to clearly mark your final answer, and show your work as to how you reached that answer.

- If asked to make a table or graph (at least one of the long-answer questions will require this), be sure to follow standard conventions: include a title, label columns or axes (including units), plot points. Draw a line or curve only through the data provided and do not extrapolate unless asked to do so.

- Be succinct but complete in your answers, completing each thought (“closing the loop”). You will not earn points simply for quantity, but rather, for quality. The AP® graders will not know what you were thinking or what you meant; they only know what you wrote. DO NOT PROVIDE ONLY A SINGLE SENTENCE ANSWER to any question.

- When making an argument, use the structure of “claim-evidence-reasoning”, making sure that you include each of these three components in your answer.

AP® Biology: 5 Test Day Tips to Remember

1. get a good night’s sleep the night before..

Complete your intense studying by the afternoon the day before the exam, then have a good dinner and get a good night’s sleep (6-8 hours, if possible). Set your alarm, giving yourself plenty of time for breakfast and for driving to the exam site.

2. Pack your bag the night before:

Review the items that you are and are not allowed to bring to the AP® Biology exam and pack accordingly. Use Albert’s convenient checklist for packing. Include a snack and some water for the break room, but remember that these are not allowed in the testing room.

3. Replace the batteries in your calculator.

Because you don’t want your calculator running out of juice during the exam, be sure to change the batteries in your calculator with a fresh set within a day or so before the exam.

4. Eat a healthy breakfast.

Be sure to eat a healthy breakfast on the morning of the exam. Make sure that it includes both protein and carbs and is not all sugary foods. Also, try to avoid over-caffeinating–you don’t want to be jittery.

5. Make sure you are free of electronic gadgets.

In this day and age, we have become so accustomed to having or wearing technology. Be sure that you are technology-free when walking into the exam room: no phones, earbuds, smart watches, bluetooth, etc.

AP® Biology Review Notes and Practice Test Resources

Here are our recommendations for resources to review for and prepare for the AP® Biology exam: Your High School Biology Textbook, Notes, Homework Assignments, Exams, Laboratory Activities, and Other Resources Provided by Your Teacher.

If you are taking an AP® Biology course, your teacher has carefully designed the course to prepare you for the AP® Biology exam. Use the many resources that your teacher has provided for AP® Biology review, carefully reviewing your notes, exams, homework assignments, etc.

AP® Biology Practice Materials Provided by the College Board:

The College Board has provided quite a lot in the way of practice materials for the AP® Biology exam. Throughout this document, we have mentioned the AP® Biology Course and Exam Description (CED) multiple times. You should review this document carefully. Note that there are 15 multiple choice practice questions and correct answers that address content knowledge from all eight units as well as skills from all six science practices. This document also provides two practice free response questions (one long-answer question and one short-answer question) with detailed grading rubrics.

The College Board has also released the free-response questions with scoring guidelines from the 20 years’ worth of exams through 2019. The College Board has also released a complete AP® Biology practice test with answers based upon the 2013 exam .

OpenStax AP® Biology Textbook and Resources :

This is a great freely available textbook with associated resources designed specifically for preparing for the AP® Biology exam. There are additional resources available for students, including a student solutions manual (requires you to set up a free account) that includes solutions to many of the questions within the text. There is also a reading and notetaking guide that provides strategies for how to read the textbook and take notes as well as study.

- Use this site if: you are looking for a high-quality textbook specifically designed for preparing for the AP® Biology exam, including content knowledge and science practice questions at the end of each chapter.

- Do not use this site if: you are looking for a variety of high-quality videos to display and show the material.

Khan Academy AP/College Biology Resources :

The Khan Academy provides high quality, freely available, specific resources in support of preparing for the AP® Biology exam. Each section includes short readings and videos about the various topics, as well as practice questions, quizzes, and unit tests. While you can access these materials without signing up or logging in, by setting up an account, you can save your progress through the materials.

- Use this site if: you are a visual learner. There are lots of great videos available.

- Do not use this site if: you primarily learn by reading only or if you find it bothersome switching back and forth between methods of content presentation.

CK-12 Biology for High School Resources :

This is another great freely available set of resources including the CK-12 Biology Advanced Concepts FlexBook . Each section has practice questions associated with it.

- Use this site if: you learn well from completing worksheets (from the CK-12 Biology Workbook FlexBook ) and lots of sample quizzes and tests (from the CK-12 Biology Quizzes and Tests FlexBook ).

- Do not use this site if: you are looking for a resource that is organized in the same way as the AP® Biology exam.

Albert AP® Biology Practice Questions, Unit Assessments, and Practice Exams :

Albert has developed a series of high-quality resources to support you in your preparation for the AP® Biology exam. There are AP® Biology exam practice questions (both multiple choice and free response ) for each of the 8 content units, organized by the unit and topics found on the AP® Biology exam. For each question, clear descriptions of the correct answer as well as explanations for eliminating the incorrect answers are provided. There are also unit assessments for each of the 8 content units, as well as 4 complete AP® Biology Practice Exams . Albert also provides questions to allow for the data analysis from 13 different laboratory activities , allowing students to further practice the Science Practices also found on the AP® Biology exam.

Return to the Table of Content

Summary: The Best AP® Biology Review Guide

We have covered a lot in this AP® Bio review guide, so let’s regroup and summarize:

Exam Structure: The exam will take 3 hours to complete and is composed of two 90-minute sections:

Main Topics Covered: The exam will cover 8 content units and 6 science practices, as shown below, with each question typically covering one or more of each:

8 Content Units:

- Unit 1: Chemistry of Life

- Unit 2: Cell Structure and Function

- Unit 3: Cellular Energetics

- Unit 4: Cell Communication and Cell Cycle

- Unit 5: Heredity

- Unit 6: Gene Expression and Regulation

- Unit 7: Natural Selection

- Unit 8: Ecology

6 Science Practices:

- Science Practice 1: Concept Explanation

- Science Practice 2: Visual Representations

- Science Practice 3: Questions and Methods

- Science Practice 4: Representing and Describing Data

- Science Practice 5: Statistical Tests and Data Analysis

- Science Practice 6: Argumentation

How to Study for the AP® Biology Exam:

- Take an AP® Biology practice test

- Make a schedule

- Review challenging concepts using your resources and build your AP® Biology study guide

- Use AP® Biology exam practice resources

- Get more AP® Biology exam practice

We hope you have found this AP® Biology review guide useful. If you worked hard throughout the year in your class, have built out a good AP® Biology study guide using the advice and resources provided here, and have practiced extensively (using lots of AP® Biology practice questions and AP® Biology practice tests), you should feel positive and confident that you have what it takes to earn a strong score. Good luck!

Interested in a school license?

7 thoughts on “the best ap® biology review guide for 2024”.

Do you have one for AP® Environmental???

We will be working to release one by 4/17!

Hey Eric — in case you missed it — here is the APES review guide: https://www.albert.io/blog/ap-environmental-science-review/

I’ve heard that if you pay for the subscription, do all of the practice questions, and don’t get a four or five on the AP® exam you get a refund. Is this true?

Hi Carissa — that is a very old guarantee from our Learnerator days. We no longer offer that at this time. Thanks for asking!

will there be a score calculator for this year’s test?

Yes — our score calculator for AP® Bio is here: https://www.albert.io/blog/ap-biology-score-calculator/

Comments are closed.

Popular Posts

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

Excel at Science

- May 9, 2020

How to Answer Experiment Questions on AP Biology FRQ

Updated: Sep 22, 2023

On the AP Biology exam, the first section is multiple-choice and the second section is a set of 8 FRQs (free response questions), in which you may be given an experiment setup or asked to design an experiment yourself. Many students find the FRQs challenging because experimental design is not a specific chapter in the AP Biology textbook.

In order to answer these questions well, you need to put on your scientist’s hat and think about it as if you were running the experiment. The best way to demonstrate this is to walk through some examples of experiments. First, we will discuss the guidelines and terminology used for designing and running experiments in biology.

An experiment should always be based on a hypothesis, something that you believe might be true and that you want to test. If there is no hypothesis, there is no purpose for the experiment. Often, the hypothesis is an association between a factor and a result of interest. Some examples are:

Sunlight and plant growth

Mutation in bacteria and resistance to an antibiotic

A particular drug and decreased blood pressure

Soil acidity and flower color

Let’s take the second example, a particular mutation in bacteria and resistance to a specific antibiotic. There are so many different aspects of bacteria and the environment they live in. How can we determine that one particular trait (in this case, a mutated gene) is responsible for antibiotic resistance?

This is why scientists use controlled environments for their experiments. They can control for all factors ( keep them the same) across all experimental groups except the suspected factor, the gene mutation. Each experimental group has a different treatment or condition. In a control group, there is no special treatment. The control group serves as a baseline to compare the other groups to. The diagram below illustrates this:

Notice that all other factors (bacterial strain, concentration of nutrients, concentration of antibiotic added, etc.) are kept the same.

Another term often used in experimentation is null hypothesis . This is different from the scientific hypothesis! Many students get confused by that. The null hypothesis is more of a statistics term and it states that there will be no significant difference observed among the different experimental groups. Scientists usually hope to reject the null hypothesis , which means they do observe a real difference, supporting their scientific hypothesis . This will all become more clear when we walk through some examples.

Example Problems:

2017 FRQ - #2 Bees and Caffeine Experiment

This question involves an experiment about bees and the nectar they encounter while pollinating flowers. The scientists want to understand the role of caffeine on the bees’ memory.

The question gives a table showing the results of the experiment, shown below. It includes a control group and test group (caffeine). It also shows the probability of the bees returning to a recently visited nectar source. This probability is used to represent the bees’ short-term and long-term memory.

As you read through the question and think about the experiment, you should consider the set of questions below. Just consider them, no need to write them down. They will help you plan out your responses to the actual problem:

What are these scientists testing in this experiment? In other words, what is their scientific hypothesis ?

What is the independent and dependent variable?

What is the difference between the control and test group? What’s the purpose of the control group? Note that sometimes there is more than one test group. Here, we only have one, which is the caffeine treatment group.

What is the null hypothesis ?

How could the experimental data be represented graphically?

What do the +/- values mean in each of the data cells?

If you are able to answer all those questions, you will have no trouble with this problem. So let’s answer them:

The scientific hypothesis is that exposure to caffeine is associated with the bees’ memory.

The independent variable is the treatment, which is exposure to caffeine. The dependent variable is what is impacted. Here, that is the bees’ memory.

The control group is exposed to no caffeine, while the treatment group is exposed to caffeine in the nectar. The control group serves as a baseline to compare the treatment group to. If we hypothesize that caffeine has a negative impact on memory, then the probability of revisiting the nectar source should be higher for the treatment compared to the control.

The null hypothesis states that there is no significant difference in memory between the control and treatment groups. Any difference observed would be due to chance. To support the scientific hypothesis, scientists need the data to reject the null hypothesis.

The data here should be represented by a bar graph. There will be two bars, one for control and one for treatment. There should also be error bars because the standard errors are included in the data. The graph would look something like this:

2019 FRQ - #2 Ecological Relationship Between Two Protists

This question is about an experiment that investigates the ecological relationship between two protists. Are they competing for the same food? Does one predate on the other? Or do they live together in harmony and use different resources? That is what the scientists want to know.

The data collected in the experiment is given in the question, shown below.

Let’s answer the same list of questions again to really understand the experiment.

The scientific question being tested is: what kind of ecological relationship do protist species A and B have?

The independent variable is the treatment, which is the two species living together. The dependent variable is the population size of each species over time.

The control group is the species grown separately. The test group is the species grown together.

The null hypothesis states that there is no significant difference in population size between the control and treatment groups at each time point. Any difference observed would be due to chance.

The data here should be represented by a line graph, since we have time as a factor. Time should be on the x-axis -- this is almost always the case. There will be two lines, one for control and one for treatment. The graph would look something like this:

Want to improve your AP Bio free response scores, fast?

Check out the AP Bio Practice Portal , which is our popular vault of 300+ AP-style MCQ and FRQ problem sets with answers and explanations for every question. Don't waste any more time Googling practice problems or answers - try it out now!

Try the Practice Portal >

Recent posts.

How to Study for AP Biology Finals: Tactical Strategies for Success

How to Interpret Diagrams and Graphs on AP Biology Exams

How to Get a 5 on the AP Biology Exam: A Comprehensive Study Guide

How to Write an AP® Biology Lab Report

Writing a good lab report starts with taking smart steps when you conduct the lab. You should take notes about your methods, keep careful track of your data, and think critically during the lab about what could have been improved or done differently. If you are allowed to, taking pictures of your experimental setup is a good idea to make sure you are accurate in your descriptions when you write your lab report for your AP® Biology class. If photos are not allowed, consider making sketches in your lab notebook of any complicated setups. Don’t wait too long after you perform the lab to write the lab report, so that the information is still fresh in your mind.

Individual teachers vary in their specific requirements for AP Biology lab report formats, so make sure you pay attention to the instructions your teacher gives you. If you have any questions or if there is something you don’t understand, ask your teacher! They are there to help you. After you write your lab report, it is important to read over it and check for spelling or grammatical errors, which are not acceptable in scientific writing. Note that, with the exception of the title and materials list, you should always use complete sentences in your lab report.

Below are some general guidelines on how to write an AP Biology lab report. With this goal in mind, a great lab report is both concise and descriptive and contains the following sections:

The title of your lab report should be as specific as possible (i.e., “Lab 1” is not a specific title). Oftentimes, you can follow the model of “ The Effect of X on Y .” For example, in an experiment where you tested different types of fertilizer and how well they made potato plants grow, a good title would be “The Effect of Fertilizer Type on Growth in Potato Plants.”

You don’t need to go into too much detail in the title; that’s what the other sections are for. As an example, “ The Effect of Organic and Synthetic Fertilizers on Growth in Eighteen Potato Plants ” is too much information. You should be as concise as possible while still giving your reader a good idea of what type of experiment you performed and what they should expect from the overall report.

Although not all teachers will require an abstract, this section is good practice for reading and writing real scientific articles. This section should give a brief summary (typically less than 100 words) of the entire experiment and analysis. You should cover what is being studied, your hypothesis, and a summary of the results. You should also include a concluding statement of the big takeaways from the experiment.

Introduction/Background

This section of your lab report should provide your reader with any background information they will need to understand your experiment. You should introduce the purpose of the experiment in this section of the lab report so that it is clear why the lab experiment was performed.

In this portion of your lab report, you will state your hypothesis, or testable statement. Your hypothesis is generally written in an “If…, then…” format (eg, “If organic fertilizer is better for plant growth than synthetic fertilizer, then potato plants will grow taller when exposed to organic fertilizer than when exposed to synthetic fertilizer”). You should include any reasoning that went into the formation of your hypothesis.

For example, if you hypothesize that organic fertilizer will result in better potato plant growth than synthetic fertilizer, why do you think that? Generally, you need to provide a brief definition of key terms you use in this section when they are introduced.

Materials and Methods

In this portion of your lab report, you will go into detail about the materials you used in your experiment and what steps you performed. Typically, this section involves a bulleted list of all materials used and their quantities. However, different teachers may have different preferences for how the materials you used are communicated in your lab report. Remember to include all materials you used; for example, don’t forget items such as soil and water in a plant growth experiment.

In addition to the materials list, you will detail each step you took to complete your experiment. The goal of writing this section in any scientific field is to make your results reproducible by other scientists, which would make your experiment accurate and valid in the eyes of the scientific community.

Employing meticulousness in writing this section is preparing you for what to expect in the real world of science. With this in mind, make sure you mention all the variables that were controlled, along with the independent and dependent variables. In addition, you should use the past tense when writing this section, as your materials and methods are a description of an experiment that you have already performed. For example, you would write, “the height of each potato plant was measured daily”, not “measure the height of each potato plant daily.”

The results you obtained during your experiment are displayed in this section of your lab report. Usually, this will be in the form of table(s) and/or graph(s), depending on your experiment. Think about your experiment and results, and how you can best depict them visually.

When creating tables and graphs, make sure each one is clear and easy to follow and that they each have a descriptive title. Consider whether you should include averages for experiments in which multiple trials were performed. When you display numerical figures, units should always be included. If your lab report contains a graph, make sure to label both the X and Y axes appropriately and to include a key or legend if necessary. In some labs, you will perform statistical analyses; make sure to include this here if it was part of your experiment.

The statistical analyses, graphing tasks, and tabular data production required for your AP Biology lab report are directly tied to the science practices you will be tested on during the AP Biology exam, as shown in our AP Biology Study Guide and Materials article. So make sure you put your best effort into learning and mastering the skill set of representing scientific data in a visual manner and using statistics-based reasoning.