- For the Press

- Our Programs

- Endorsements

- Partner With GDCI

- Guides & Publications

- search Search

- globe Explore by Region

- Global Street Design Guide

Download for Free

Thank you for your interest! The guide is available for free indefinitely. To help us track the impact and geographical reach of the download numbers, we kindly ask you not to redistribute this guide other than by sharing this link. Your email will be added to our newsletter; you may unsubscribe at any time.

" * " indicates required fields

About Streets

- Prioritizing People in Street Design

- Streets Around the World

- Global Influences

- A New Approach to Street Design

- How to Use the Guide

- What is a Street

- Shifting the Measure of Success

- The Economy of Streets

- Streets for Environmental Sustainability

- Safe Streets Save Lives

- Streets Shape People

- Multimodal Streets Serve More People

- What is Possible

- The Process of Shaping Streets

- Aligning with City and Regional Agendas

- Involving the Right Stakeholders

- Setting a Project Vision

- Communication and Engagement

- Costs and Budgets

- Phasing and Interim Strategies

- Coordination and Project Management

- Implementation and Materials

- Maintenance

- Institutionalizing Change

- How to Measure Streets

- Summary Chart

- Measuring the Streets

Street Design Guidance

- Key Design Principles

- Defining Place

- Local and Regional Contexts

- Immediate Context

- Changing Contexts

- Comparing Street Users

- A Variety of Street Users

- Pedestrian Networks

- Pedestrian Toolbox

- Sidewalk Types

- Design Guidance

- Crossing Types

- Pedestrian Refuges

- Sidewalk Extensions

- Universal Accessibility

- Cycle Networks

- Cyclist Toolbox

- Facility Types

- Cycle Facilities at Transit Stop

- Protected Cycle Facilities at Intersections

- Cycle Signals

- Filtered Permeability

- Conflict Zone Markings

- Cycle Share

- Transit Networks

- Transit Toolbox

- Stop Placement

- Sharing Transit Lanes with Cycles

- Contraflow Lanes on One-Way Streets

- Motorist Networks

- Motorist Toolbox

- Corner Radii

- Visibility and Sight Distance

- Traffic Calming Strategies

- Freight Networks

- Freight Toolbox

- Freight Management and Safety

- People Doing Business Toolbox

- Siting Guidance

- Underground Utilities Design Guidance

- Underground Utilities Placement Guidance

- Green Infrastructure Design Guidance

- Benefits of Green Infrastructure

- Lighting Design Guidance

- General Strategies

- Demand Management

- Network Management

- Volume and Access Management

- Parking and Curbside Management

- Speed Management

- Signs and Signals

- Design Speed

- Design Vehicle and Control Vehicle

- Design Year and Modal Capacity

- Design Hour

Street Transformations

- Street Design Strategies

- Street Typologies

- Example 1: 18 m

- Example 2: 10 m

- Pedestrian Only Streets: Case Study | Stroget, Copenhagen

- Example 1: 8 m

- Case Study: Laneways of Melbourne, Australia

- Case Study: Pavement to Parks; San Francisco, USA

- Case Study: Plaza Program; New York City, USA

- Example 1: 12 m

- Example 2: 14 m

- Case Study: Fort Street; Auckland, New Zealand

- Example 1: 9 m

- Case Study: Van Gogh Walk; London, UK

- Example 1: 13 m

- Example 2: 16 m

- Example: 3: 24 m

- Case Study: Bourke St.; Sydney, Australia

- Example 2: 22 m

- Example 3: 30 m

- Case Study: St. Marks Rd.; Bangalore, India

- Example 2: 25 m

- Example 3: 31 m

- Case Study: Second Ave.; New York City, USA

- Example 1: 20 m

- Example 2: 30 m

- Example 3: 40 m

- Case Study: Götgatan; Stockholm, Sweden

- Example 1: 16 m

- Example 2: 32 m

- Example 3: 35 m

- Case Study: Swanston St.; Melbourne, Australia

- Example 1: 32 m

- Example 2: 38 m

- Case Study: Boulevard de Magenta; Paris, France

- Example 1: 52 m

- Example 2: 62 m

- Example 3: 76 m

- Case Study: Av. 9 de Julio; Buenos Aires, Argentina

- Example: 34 m

- Case Study: A8erna; Zaanstad, The Netherlands

- Example: 47 m

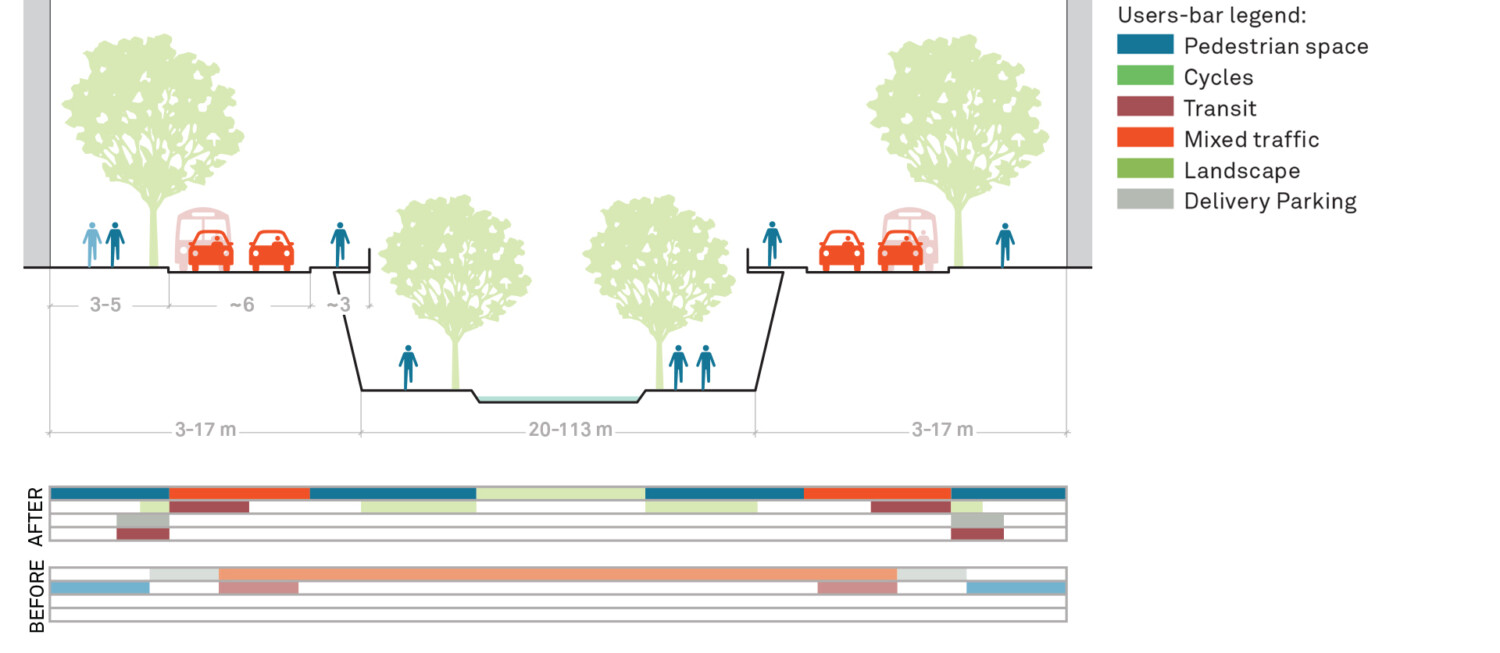

Case Study: Cheonggyecheon; Seoul, Korea

- Example: 40 m

- Case Study: 21st Street; Paso Robles, USA

- Types of Temporary Closures

- Example: 21 m

- Case Study: Raahgiri Day; Gurgaon, India

- Example: 20 m

- Case Study: Jellicoe St.; Auckland, New Zealand

- Example: 30 m

- Case Study: Queens Quay; Toronto, Canada

- Case Study: Historic Peninsula; Istanbul, Turkey

- Existing Conditions

- Case Study 1: Calle 107; Medellin, Colombia

- Case Study 2: Khayelitsha; Cape Town, South Africa

- Case Study 3: Streets of Korogocho; Nairobi, Kenya

- Intersection Design Strategies

- Intersection Analysis

- Intersection Redesign

- Mini Roundabout

- Small Raised Intersection

- Neighborhood Gateway Intersection

- Intersection of Two-Way and One-Way Streets

- Major Intersection: Reclaiming the Corners

- Major Intersection: Squaring the Circle

- Major Intersection: Cycle Protection

- Complex Intersection: Adding Public Plazas

- Complex Intersection: Improving Traffic Circles

- Complex Intersection: Increasing Permeability

- Acknowledgements

- Conversion Chart

- Metric Charts

- Summary Chart of Typologies Illustrated

- User Section Geometries

- Assumptions for Intersection Dimensions

- search Keyword Search

- Special Conditions

- Elevated Structure Removal

The Seoul Metropolitan Government decided to dismantle the 10-lane roadway and the 4-lane elevated highway that carried over 170,000 vehicles daily along the Cheonggyecheon stream. The transformed street encourages transit use over private car use, and more environmentally sustainable, pedestrian oriented public space. The project contributed to a 15.1% increase in bus ridership and a 3.3% increase in subway ridership between 2003 and 2008. The revitalized street now attracts 64,000 visitors daily.

- Improve air quality, water quality, and quality of life.

- Reconnect the two parts of the city that were previously divided by road infrastructure.

Lessons Learned

Innovative governance and interagency coordination were critical to the process.

Public engagement, with residents, local merchants, and entrepreneurs, was important to streamlining the process.

Reducing travel-lane capacity resulted in a decrease in vehicle traffic.

Involvement

Public Agencies Central Government, Seoul Municipality, Seoul Metropolitan Government, Cultural Heritage Administration

Private Groups and Partnerships Cheonggyecheon Research Group

Citizen Associations and Unions Citizen’s Committee for Cheonggyecheon Restoration Project

Designers and Engineers Seoul Development Institute urban design team, Dongmyung Eng, Daelim E&C

Close to 4,000 meetings were held with residents. A “Wall of Hope” program was developed to encourage involvement and resulted in 20,000 participants.

Key Elements

Removal of elevated highway concrete structure.

Daylighting of a previously covered urban stream.

Creation of an extensive new open space along the daylighted stream.

Creation of pedestrian amenities and recreational spaces (two plazas, eight thematic places).

Construction of 21 new bridges, reconnecting the urban fabric.

Project Timeline

Adapted by Global Street Design Guide published by Island Press.

Urban Regeneration: A Case of Cheonggyecheon River

Project Location: Seoul, South Korea Timeline: 2002 -2005 (3 years and 6 months) Architects: Mikyoung Kim Design Client: City of Seoul

Seoul , the capital of South Korea, is confronted with many significant issues. The effects of overpopulation and urbanization have resulted in a multitude of challenges, including scarcities in housing, transportation, and parking facilities, as well as the worsening of pollution levels and the unsustainable exploitation of resources. It is always gridlocked. Over a decade, urban and industrial development suffocated the remaining traces of nature in the city’s heart, notably in the congested and flat CBD.

Hoping to spur economic growth by providing new recreation options to residents and solve the city’s chronic runoff problems, The Seoul Metropolitan Government decided to do something bold. An initiative to transform the urban environment of the massive arterial highway by removing it and replacing it with a long, meandering park and stormwater mitigation system.

Degradation of the River

The Cheonggyecheon River is situated amid a historically significant neighbourhood. The first deterioration of the site can be traced back to the 15th century when many factors contributed to its decline. These factors include the expansion and depth of the river channel, the building of a stone and wood embankment, the use of the watercourse as a means of waste disposal, and the heightened sedimentation caused by the deforestation of the surrounding regions. Despite undergoing continuous dredging and modifications throughout the twentieth century, the river channel in the 1950s remained mostly a seasonal stream used by individuals for laundry purposes and as a recreational space for children.

As Seoul underwent a gradual transformation from a mostly rural area to a sprawling East Asian city, the Cheonggyecheon, referred to as the “clear valley stream,” deteriorated into a polluted waterway. The primary function of the stream in question was to serve as Seoul’s central sewage and drainage system, primarily designed to mitigate the risk of flooding.

By the year 1970, the area next to the river was characterized by the presence of slums. Additionally, the quality of the water in the river deteriorated with time due to a series of human interventions, including the process of channelization followed by the application of a concrete layer.

With the rapid progression of urbanization and industry, along with the widespread adoption of automobiles, the riverbed transformed, being repurposed into a 6-kilometre roadway. Above this roadway, a 5.8-kilometre elevated highway was constructed, boasting six lanes to accommodate the increasing vehicular traffic. Before the process of restoration began, the daily volume of vehicles that passed through this particular section amounted to almost 168,000. Among them, a significant proportion of 62.5% constituted vehicles engaged in traffic.

The ramifications of the very crowded transportation system along Cheonggye Street have become more severe. The levels of air pollution, namely criterion pollutants, were found to be much higher than the permitted thresholds. Additionally, the pollution caused by nitrogen oxide is above the established environmental air quality guideline for the city of Seoul. In addition, the concentrations of benzene, a volatile organic compound (VOC) known for its carcinogenic properties, were found to be elevated.

According to a health awareness study conducted among those living or employed near Cheonggyecheon, it was observed that the prevalence of respiratory disorders was more than twice as high compared to individuals residing in other geographical regions (SDI, 2003A). In conjunction with atmospheric pollution, the noise pollution observed in this particular region exceeded the prescribed benchmarks for commercial zones, hence posing a significant impediment to the creation of a desirable residential and occupational milieu.

In the year 2000, an engineering study was conducted which revealed the presence of structural deficiencies in the aforementioned roadways, hence highlighting the imperative need for a significant rehabilitation endeavour. The degradation and contamination of the Cheonggyecheon River stream may be attributed to the processes of urbanization, transportation , and industrial activities.

The objectives established for the urban revitalization initiative included the restoration of Cheonggyecheon’s natural ecosystem and the development of a public space that prioritizes human needs and experiences.

The proposed project included a range of objectives, including the restoration and landscaping of the stream, the establishment of measures to ensure water resource sustainability, the implementation of sewage treatment systems, the management of traffic flow, the construction of bridges across the river, the preservation and restoration of historical assets, and the effective resolution of social problems.

In addition to the aforementioned, the plan was formulated with the objectives of the restoration of cultural assets, as well as the conservation of all dug heritage pieces throughout the building process. Enhance the overall quality of air, water, and living conditions. The objective was also to establish a connection between the two geographically divided areas due to the river.

In the year 2003, the river underwent a process of re-exposure and was subsequently designated as the central element of a broader initiative aimed at revitalizing the urban environment. The rerouting of traffic, construction of bridges across the river, establishment of public parks and recreational areas, and renovation of nearby places of historical and cultural significance were undertaken. The enhancement of environmental circumstances resulted in the establishment of a focal point that has value in historical context and possesses aesthetic allure.

The waste that was generated as a result of the destruction was subjected to recycling processes and then used again. The process of urban redevelopment included the transformation of the site into a human-centric and ecologically conscious area, with a shoreline and pathways that run alongside the stream. Embankments were constructed to mitigate the most severe floods that the city may experience during the next two centuries. A total of 13.5 meters were designated to accommodate walkways, two-lane unidirectional roadways, and loading/unloading zones situated on both sides of the stream. A whole sum of 22 bridges was constructed over the Cheonggyecheon, including 5 bridges designated for pedestrian use and 17 bridges designed for motor vehicle traffic.

The stream that has been restored can be accessed from a total of 17 different sites. Terraces and lower-level pavements were constructed along both the top and lower segments of the stream, while the middle part was specifically planned to serve as an environmentally sustainable area. The incorporation of river parks and public art in many sites was undertaken to establish a platform for hosting performances and cultural events, while simultaneously augmenting the total capacity for public engagement and pleasure within the newly developed area.

The process of enhancing the aesthetic appeal of historic streets and structures was undertaken, with particular attention given to the restoration of the Gwangtonggyo Bridge. Originally constructed in 1410 to span the Cheonggyecheon Stream, this bridge was meticulously restored to its former condition, incurring a substantial expenditure of more than $5.9 million.

- Amber, P. (2011) ChonGae Canal Restoration Project / mikyoung Kim design, ArchDaily. Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/174242/chongae-canal-restoration-project-mikyoung-kim-design .

- Case study: Cheonggyecheon; Seoul, Korea (2017) Global Designing Cities Initiative. Available at: https://globaldesigningcities.org/publication/global-street-design-guide/streets/special-conditions/elevated-structure-removal/case-study-cheonggyecheon-seoul-korea/ .

- Cheonggyecheon (2015) Photography Life. Available at: https://photographylife.com/photo-spots/cheonggyecheon .

- Cheonggyecheon Stream restoration project (2011) Landscapeperformance.org. Available at: https://www.landscapeperformance.org/case-study-briefs/cheonggyecheon-stream-restoration-project .

- McAskie, L. (2021) From emissions to Edens: Our top 5 car-free urban transformations, Citychangers.org – Home Base for Urban Shapers. CityChangers.org. Available at: https://citychangers.org/top-5-car-free-urban-transformations/?cn-reloaded=1 .

- River restoration and conservation (no date) Coolgeography.co.uk. Available at: https://www.coolgeography.co.uk/advanced/River_Restoration_Conservation.php .

- Seoul (no date) Worldbank.org. Available at: https://urban-regeneration.worldbank.org/Seoul .

- South Korea: Restoration of the cheonggyecheon river in downtown Seoul (no date) Ser-rrc.org. Available at: https://www.ser-rrc.org/project/south-korea-restoration-of-the-cheonggyecheon-river-in-downtown-seoul/ .

- studioTECHNE (2018) Field notes: Tom goes to Seoul, studio TECHNE | architects. Available at: https://www.technearchitects.com/blogs/2018/12/12/toms-field-notes-from-seoul (Accessed: August 6, 2023).

A Postgraduate student of Architecture, developing an ability of Design led through Research. A perceptive observer who strives to get inspired and, in doing so, become one. Always intrigued by the harmonious relationships between people and space and the juxtaposition of the tangible and intangible in architecture.

Renovation of Castle Grad by ARREA architecture

Colour and Architecture in Wes Anderson’s Cinematic World

Related posts.

Food Streets to Fine Dine: How Architecture Drives Food Culture

How Modernism Influenced Indian City Planning

How was the architecture of the Parthenon used as a religious symbol?

Exploring Unrealized Designs of Famous Architects: Ideas That Could Have Shaped Our Cities

Mughal Architecture: Where East Met West through Cultural Expression

Reimagining Cities: Integrating Regenerative Design for Sustainable Urban Futures

- Architectural Community

- Architectural Facts

- RTF Architectural Reviews

- Architectural styles

- City and Architecture

- Fun & Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Design Studio Portfolios

- Designing for typologies

- RTF Design Inspiration

- Architecture News

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Construction & Materials

- Covid and Architecture

- Interior Design

- Know Your Architects

- Landscape Architecture

- Materials & Construction

- Product Design

- RTF Fresh Perspectives

- Sustainable Architecture

- Top Architects

- Travel and Architecture

- Rethinking The Future Awards 2022

- RTF Awards 2021 | Results

- GADA 2021 | Results

- RTF Awards 2020 | Results

- ACD Awards 2020 | Results

- GADA 2019 | Results

- ACD Awards 2018 | Results

- GADA 2018 | Results

- RTF Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2016 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2015 | Results

- RTF Awards 2014 | Results

- RTF Architectural Visualization Competition 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2020 – Results

- Designer’s Days of Quarantine Contest – Results

- Urban Sketching Competition May 2020 – Results

- RTF Essay Writing Competition April 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2019 – Finalists

- The Ultimate Thesis Guide

- Introduction to Landscape Architecture

- Perfect Guide to Architecting Your Career

- How to Design Architecture Portfolio

- How to Design Streets

- Introduction to Urban Design

- Introduction to Product Design

- Complete Guide to Dissertation Writing

- Introduction to Skyscraper Design

- Educational

- Hospitality

- Institutional

- Office Buildings

- Public Building

- Residential

- Sports & Recreation

- Temporary Structure

- Commercial Interior Design

- Corporate Interior Design

- Healthcare Interior Design

- Hospitality Interior Design

- Residential Interior Design

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- Urban Design

- Host your Course with RTF

- Architectural Writing Training Programme | WFH

- Editorial Internship | In-office

- Graphic Design Internship

- Research Internship | WFH

- Research Internship | New Delhi

- RTF | About RTF

- Submit Your Story

- Hispanoamérica

- Work at ArchDaily

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

Building a City from Scratch: The Story of Songdo, Korea

- Written by Kaley Overstreet

- Published on June 11, 2021

What does it take to build a smart city from nothing ? Or maybe the better question is, what does it take to build a smart city from nothing and make it successful? For over a decade, architects and urban planners worked hand in hand to create Songdo , a brand new business district that sought to represent South Korean advancements in technology and infrastructure. Songdo was once a model for how we would live in cities of the future- but now, the reality of what this smart city quickly became has us rethinking how the combination of technology and community might have gone wrong.

Seeking suburban sprawl away from an overcrowded Seoul , Songdo was constructed out of nothing, built on nearly 1,500 acres of land that was reclaimed from the Yellow Sea. Technically, Songdo is considered an extension of Incheon, a large international transportation hub that allows the city to be easily accessible by foreign and domestic travelers. Songdo was conceptualized in the early years of the 21st century as a completely sustainable, high-tech city, that would plan for a future without cars, without pollution, and without overcrowded spaces. It was essentially a utopia that offered everything that Seoul didn’t, and was positioned as a new global economic center, with the right talent and business that would allow it to compete with other Asian markets.

To accomplish these rather lofty goals, some of the world’s most advanced urban technologies were utilized. The streets that connect the district are lined with sensors that measure energy use and traffic flow as a means of quantifying sustainability to support its highest concentration of LEED-certified projects in the world. Songdo also features a massive seaside park outfitted with self-sustaining irrigation systems to provide ample public space. At the level of individual residents, trash tubes take garbage away to a central plant where it is automatically sorted into recyclables and waste to be burned. Even homes are operated by cellphone apps that control everything from heating and air conditioning, to artificial light levels.

There’s no doubt that Songdo is revolutionary and is by far the most technologically integrated city in the world. But what it forgets in its vision for the city of the future, is that cities are designed for people, not for fancy AI features and sensors. Many critics and inhabitants alike say that living there is “cold” and “deserted”, with some going so far as to compare it to the ghost town of Chernobyl. With a population of just over 80,000, and with the first major phase of development soon coming to an end, it’s hard to tell just how successful and desirable Songdo will be.

What the designers and planners of Songdo should have done was design around the perspective and needs of a human being first with technology acting as the supplement, instead of designing for technology, with humans being just in the peripheral. It’s easy to automate many processes, and collect infinite amounts of data- but is it necessary to ensure that a city is performing? Are all aspects of urban performance quantifiable, or can it be described through less tangential measurements like the overall happiness of its residents? Songdo is proof that high-tech cities don’t always equate to high-impact communities.

Image gallery

- Sustainability

想阅读文章的中文版本吗?

从零开始的新城市:韩国松岛

You've started following your first account, did you know.

You'll now receive updates based on what you follow! Personalize your stream and start following your favorite authors, offices and users.

- Open access

- Published: 01 December 2023

A study on a political system for the advance in green hydrogen technology: a South Korea case study

- Minyoung Yun 1 ,

- Wooseok Jang 1 ,

- Jongyeon Lim 1 &

- Bitnari Yun 1 , 2

Energy, Sustainability and Society volume 13 , Article number: 43 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1504 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

Hydrogen energy, a type of renewable energy if produced without fossil fuel, has a critical issue in that most of it is still produced from carbon footprint heavy industries such as the fossil fuel industry. It is imperative to produce hydrogen from renewable sources on a global level so that the carbon footprint can be curbed. South Korea, along with other global economies such as the US, the EU, Japan and China, has shown its resolution to build a hydrogen economy with green hydrogen produced only from renewable sources. Since 2017, South Korea has been actively shaping its political actions and policies to develop the necessary technology for this transition. This study focuses on South Korea's actions and policies, using a political system model to better understand the shift towards a green hydrogen economy.

The analysis shows that budgeting for R&D projects has had a significant impact on scientific breakthroughs, advancements, and product development in the field of green hydrogen in South Korea. These actions have also affected market performance, resulting in increased interest and investment in green hydrogen. Although there have been significant advancements in the field of green hydrogen in South Korea, the current state of technology remains in its early stages of development. Most of the breakthroughs have been in water-to-hydrogen and biomass-to-hydrogen technologies. However, these technologies show promise as the foundation of a thriving hydrogen economy in South Korea. The analysis also indicates a strong market demand for green hydrogen technology. To support these efforts, the political system has focused its financial support on water-to-hydrogen technology and projects at the TRL 1–3 stage.

Conclusions

The study concludes that ongoing financial and political support is necessary for areas showing outstanding performance to vitalize the hydrogen economy and facilitate the transition to a green hydrogen society in the future. Additionally, a robust legal framework is crucial to ensure steady growth of the green hydrogen economy, similar to those in other major hydrogen economies such as the US and Germany. This study serves as a case study of South Korea, showcasing the impact of political actions on the advancement of scientific technology.

Hydrogen energy, which emits zero carbon footprint when consumed, has been mostly produced from fossil fuels such as methane or natural gas [ 1 ]. This reality about hydrogen energy raises the question: “Is hydrogen energy actually a clean energy?” [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]. There has been a global consensus that this way of producing hydrogen is hardly sustainable [ 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Big economies such as the US, the EU, Japan and China have shown a resolution to replace hydrogen produced from natural gas (grey hydrogen) with hydrogen from water or biomass produced with renewable energy (green hydrogen) [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. Grey hydrogen is solely produced from fossil fuels such as natural gas. Blue hydrogen is similar to grey hydrogen in that it is a fossil-fuel-based hydrogen but with carbon dioxide stored in the production process [ 9 ]. Green hydrogen is produced from renewable sources such as water powered with solar or wind energy. Green hydrogen is considered the most eco-friendly because it emits no carbon footprint and can safely store renewable energy [ 15 ].

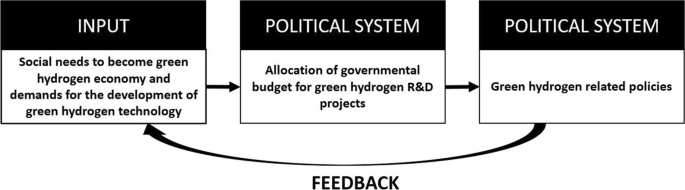

Since the Moon administration came to power in 2017, South Korea has joined the global trend of pursuing a green hydrogen economy [ 2 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. In addition to meeting the requirements for a green hydrogen economy, such as social acceptance and community agreement, South Korea has made significant efforts to develop the technology aspect of green hydrogen due to its high dependence on energy imports (92.8%), as reported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs [ 20 ]. Given its high dependence on energy imports, South Korea has made significant efforts to develop green hydrogen technology as a crucial component of its energy security strategy. To this end, the country has introduced over a dozen policies related to green hydrogen since 2017, laying the foundation for an institutionalized system necessary for a green hydrogen economy [ 21 , 22 , 23 ]. The implementation of such policies requires a set of environmental conditions such as demands, support, and a political system, as defined by David Easton [ 24 ]. Figure 1 in Easton's model provides a suitable theoretical framework to explain how social demands for green hydrogen are institutionalized into policies [ 24 , 25 ]. In this case, the demands and support have come from within and outside of South Korea, such as the Paris Agreement of 2018 and the national will to domestically develop green hydrogen technology to achieve energy independence [ 26 ]. The South Korean government also aims to monetize the developed technology to facilitate energy exports [ 6 , 19 ]. These demands as inputs drive the political system which leads to the outputs.

Schematic of political system

Laws and policies are critical components of building a green hydrogen economy in South Korea, and they are among the outputs of the political system. Since there are currently only a few legal frameworks related to hydrogen, such as a single hydrogen safety law [ 2 ], the dozen or so green hydrogen policies introduced since 2017 are the primary outputs. The purpose of this study is to examine the political system and analyze its output of policies for green hydrogen technology. Specifically, this study aims to define and analyze the relationship between the political system and green hydrogen policies. Since politics involves multiple factors [ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ], a study of the political system can take various forms. For instance, researchers have used literature research to understand Bangladesh's policy for greening its brick industry [ 31 ], a game-theoretic model to examine the change in market behavior resulting from Pakistan's climate policy [ 32 ], and a survey to learn about the influence of Korean policy on perceptions of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles [ 17 ]. Others have used indicator-based analysis to identify the causes and effects of water policies in India [ 33 ], an evolutionary game model to analyze the impact of national policy on new energy vehicles (NEV) [ 34 ], and Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) to evaluate the impact of a policy by examining the outputs of government-funded research projects [ 35 ].

Evaluating government-funded research projects in terms of their budgets and outputs provides an effective and measurable way to see how political action, such as funding research and development (R&D) projects, affects the advancement of technology. To our knowledge, the analysis of policies and government-funded projects in terms of green hydrogen in South Korea has not been carried out yet. In this study, the political system, an authoritative allocation of resources according to David Easton’s study, is defined as the distribution of national budgets for green hydrogen R&D research projects as presented in Fig. 1 [ 24 ]. Accordingly, the elements of the political system are defined as the political actions of budgeting and their impacts, which are the outputs of financed R&D projects, such as journals or patents. The major contributions of this work are to help the South Korean government understand the political system for the advancement in green hydrogen technologies for future planning and to show where South Korea, a large global economy, is positioned with respect to green hydrogen energy.

The rest of the article is structured as follows. Methods provides the methodology of the data collection and the analysis of the political system and policies. Results and Discussion show the analysis of the political actions of budgeting, the project outputs, and the policies. The conclusions presents the conclusion and policy recommendations.

Data collection

The method for the data collection is summarized in Table 1 . First, hydrogen, especially green hydrogen, related policies were found on the websites of government ministries and government websites for policy information. For the government budget analysis, the data on government-funded hydrogen projects during 2017–2021 were collected from the website of the National Science & Technology Information Service (NTIS). NTIS is a South Korean governmental database service which provides government-funded R&D project data. A total of 5824 hydrogen projects were identified, of which 2098 were green hydrogen projects. Last of all, the data of the project outputs were also collected from the NTIS website. Specifically, 13,684 journals, 5613 patents, 72 technology, and 39 business data from hydrogen projects were collected. In the case of patents and journals, duplicate outputs were counted and deleted. Journal data, peer-reviewed articles, including scientific research articles, review articles, conference articles and letters. Patent data include domestic and international patents. The technology case means the case of sold technology developed in a government-funded R&D project. The case of business means a research project developing into a business.

- Political system

The political system consists of two parts: political action and its impacts. In the political system, political action is an allocation of the national budget to green hydrogen R&D projects. Political action is analyzed in terms of the size of the budget and the type of projects to be funded. The impacts of political actions are measured and analyzed based on scientific and market performance, which are both important and representative. The indices for scientific impacts include journals and patents. The indices for market impacts are the number of sold technologies and the number of business cases. The scientific and market impacts are studied by year, technology, and TRL of projects.

The green hydrogen policies are the outputs of the political system. The policies are analyzed yearly and by their main objectives. Further analysis is carried out in terms of how the policies are aligned with the elements of the political system such as political actions and the impacts.

Budget analysis as political action

The political system is analyzed by examining the political action of budgeting. The analysis is carried out in three categories: the budget, the technology readiness level (TRL) of projects, and the types of developed technologies. Firstly, government funding for hydrogen projects and green hydrogen projects increased nearly 3.5fold from 2017 to 2021, as shown in Table 2 . About a quarter of the total hydrogen budget was allocated to green hydrogen projects, while the remaining 75% of the budget was spent on hydrogen storage, utilization (e.g., fuel cells), and safety-related projects. This indicates a significant increase in financial support for green hydrogen R&D projects. Compared to the annual average increase of 5.8% in R&D project budgets from 2016 to 2020, the 233% increase for green hydrogen research is considerably higher [ 36 ].

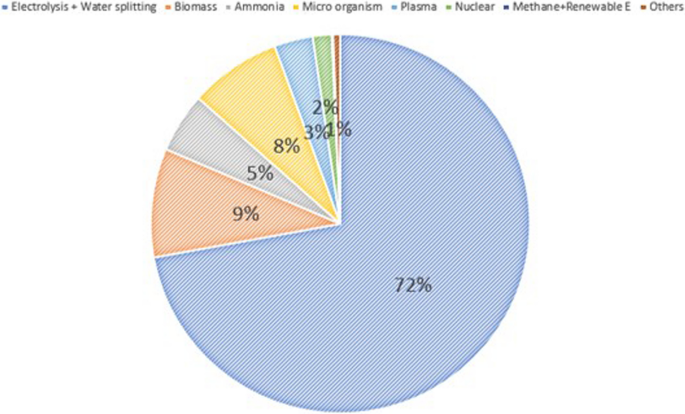

The next part to assess is the budget scale for specific green hydrogen technologies. As shown in Fig. 2 , a majority (72%) of the green hydrogen budget has been allocated for water-to-hydrogen technology projects. The water-to-hydrogen projects concern processes to extract hydrogen from water using any type of energy source, including nuclear and plasma energy. The rest of the green hydrogen projects concern the production of hydrogen from biomass or ammonia and various technologies such as microorganisms, plasma, and nuclear power-aided hydrogen production which is also called yellow hydrogen. It can be said that the emphasis is given to water-to-hydrogen technology with a majority of the budget allocated there. Biomass technology is the second most invested technology.

Budget composition of green hydrogen projects by its goal technology to develop

Lastly, the budget scale for green hydrogen R&D projects on different TRLs is analyzed as shown in Table 3 . The analysis reveals that projects on TRL 1–3 were funded the highest between 2017 and 2021, accounting for 41% of the total green hydrogen budget. There is not a big difference between the budget size for TRL 1–3 projects and TRL 7–9 projects. The regression analysis found that the projects on TRL 1–3 are funded with the lowest yearly increase rate of 40 (10 8 won/year), which indicates that more budget was allocated to projects on higher TRLs as the year progressed. It can be said that the allocation of funding for the fundamental level of green hydrogen technology has not been prioritized in the previous years of political actions.

Impacts as political action

The policy impacts are analyzed in terms of the outputs of the funded green hydrogen projects which are journal, patent, sold technology, and business case. First, yearly outputs are studied and presented in Table 4 . In the span of 2017–2021, green hydrogen projects yielded numerous scientific accomplishments, including 3258 scientific journals (non-SCI and SCI articles), 990 patents, 72 sold technologies, and 39 business cases. In comparison to the average performance of total R&D projects of 2015–2020 in Table 5 , the outputs except for journals have underperformed. Here, the 6-year average between 2015 and 2020 was utilized for comparison because this is the most recent available data. The most plausible reason for this is that the research field of green hydrogen technology in South Korea is too rudimentary to start producing these outputs. These types of outputs can come in the future according to the time-lag effect. The time-lag effect means years or sometimes decades could be required for research projects to start producing outputs. Another proof that the field is still on a rudimentary level is the fact that only scholarly performance (journal) met the average level of total R&D projects with the rest of market-related outputs underperforming because the first output from research projects tends to be research journals.

Secondly, the outputs per specific technologies were analyzed and shown in Table 6 . Most of the scientific and marketable achievements were made in water-to-hydrogen technology. These projects accounted for the majority (80%) of journals, patents, and technology cases related to green hydrogen. The result makes sense, considering the majority of the green hydrogen budget was allocated to the technology. It is also noticeable that the highest amount of business cases came from biomass technology which is a significant achievement because biomass technology acts as a bridge technology between a grey and green hydrogen economy.

Lastly, an analysis of the performance of projects on different TRLs is presented in Tables 7 and 8 . The majority of journals, patents, and business cases were produced by projects on TRL 1–3, while projects on TRL 7–9 with more advanced technology scored highest in terms of monetization. The performance in terms of journals is consistent with the trend seen in the annual report by NTIS, which showed that 75% of published journals in all fields were from projects on TRL 1–3 in 2016–2020. In terms of patents, while the NTIS analysis of total patents in all fields in 2015–2021 shows that 34.42%, 20.34%, and 45.2% of patents were, respectively, from TRL 1–3, 4–6, and 7–9 projects, as much as 60% of green hydrogen patents came from projects on TRL 1–3. This is likely due to the fact that the highest amount of green hydrogen budget was allocated to projects on TRL 1–3, as evidenced by the fact that 1,097 projects were in the TRL 1–3 range. In terms of technology cases, most technology in all fields (72.2%) from 2015 to 2020 came from projects on the highest TRL of 7–9, as advanced technologies are more marketable. For green hydrogen projects, 79% of technology cases were from TRL 7–9 projects, which is consistent with the trend seen in past years of total R&D projects. In terms of business cases, most businesses from total R&D projects from 2015–2020 came from the most advanced level of projects (TRL 7–9), with only 5.4% of business cases from projects on TRL 1–3. However, for green hydrogen projects, most business cases (76%) came from projects on TRL 1–3, which is significantly higher than the average and extraordinary. It is noteworthy that patents and business cases showed different results compared to the total 6-year-average value, which could indicate either the existence of accumulated green hydrogen technology at the level of TRL 1–3 in specific areas or high demand for a fundamental level of green hydrogen technologies in the market, given that patents and business are more performance-driven than academic journals.

Policy analysis

Hydrogen policies appeared early in the 2000s but they were mainly concerning fuel cell vehicles and their market. Starting in 2017 with the Moon administration in power, however, green hydrogen-related policies started appearing and 11 major policies were published in the span of 2017–2021. The summary is given in Table 9 .

The goals of the policies are summarized as follows. The goals consist largely of three parts: financial research support for green hydrogen R&D projects, low TRL projects, and projects with certain technology. In terms of financial support, the policies promise to increase the budget support for green hydrogen R&D projects over the years. The policies regarding expansive R&D support for green hydrogen technology in 2020 and 2021 agree well with the political actions of 2017–2021 that the funding for green hydrogen R&D has increased more than threefold. The policies mention the financial support for R&D projects to develop the technology, green hydrogen production sites/facilities, and for building infrastructures for green hydrogen. This agreement is especially important considering the analysis of project outputs that the domestic level of green hydrogen technology is on a rudimentary level which requires increasing and steady financial support. Also, the agreement means that the political action of budgeting for green hydrogen R&D projects has been supported by political foundations such as the policies which can guarantee steady support for the sturdy growth of green hydrogen technology. As for the TRL of projects, the goal, as specified in the policies with the budget plan published in 2020 and 2021, is to prioritize the budget support for R&D projects on fundamental levels of technology (TRL 1–3). This is to ensure South Korea is equipped with fundamental green hydrogen technology by 2026. This focus on TRL 1–3 is because policymakers have acknowledged that South Korea lacked fundamental green hydrogen technology. This can be supported by the analysis of the impacts of political actions and project outputs, which shows that the scientific and market performances do not reach the average level of total R&D projects except for journals. Even if the political actions of the past years have not prioritized the funding for TRL 1–3 projects, the funding can increase with the introduction of the policy. With this momentum, political actions in the future can boost both the scientific and market performance of TRL 1–3 projects. Lastly, the policies regarding electrolysis in 2018, 2019 and 2021 show the governmental will to focus on water-to-hydrogen technology—especially electrolysis in connection with other renewable energies such as solar and wind power. This governmental goal is set to be achieved with short to mid-term plans. As for biomass technology, the South Korean government plans to utilize the technology as a bridge between grey and green hydrogen technologies. The announcement of the policies was accompanied by the political actions of budget allocation to meet the objectives. For example, the majority of green hydrogen budgets have been allocated to water-to-hydrogen technology which resulted in several scientific and market outputs. Especially, the biomass-to-hydrogen projects have produced several business cases which help the national goal of using it as a bridge technology. This agreement between political actions and policies can result in synergy to produce increasing impacts of political actions.

Starting in 2017, the Moon administration in South Korea started introducing a series of political actions and green hydrogen policies aimed at building a green hydrogen economy. These actions have undoubtedly helped to institutionalize and legitimize fundamental blocks for a hydrogen economy in South Korea. This study focuses on analyzing the political system, which encompasses political actions and their impacts as well as the policies, using David Easton's theoretical framework. The analysis reveals how green hydrogen R&D projects have been funded in recent years and their impacts on scientific advancement in green hydrogen technology.

The analysis of the political action of budgeting shows that the budget for green hydrogen has increased significantly by 250%, compared to the 5.8% yearly budget average for total R&D projects. Furthermore, the analysis shows that most of the green hydrogen budget (72%) has been spent on water-to-hydrogen technology development, with TRL 1–3 projects receiving the highest funding with a marginal difference from other TRL projects.

The analysis of the impact of political actions—project outputs—shows that yearly scientific and market outputs from green hydrogen projects, except for journal publications, underperformed compared to the annual average value of total R&D projects, which could suggest that the field is quite rudimentary and in need of more time to generate performance according to the time-lag effect. Additionally, most of the journals, patents, and sold technologies are from the projects to develop water-to-hydrogen technology with close to half of the business cases from biomass projects. For the TRL of projects, a significantly high percentage of patents and business are from the projects on TRL 1–3, possibly indicating that the accumulated knowledge and the high demand for the fundamentals of green hydrogen technology in the market.

The analysis of policies in relation to the political system reveals that green hydrogen policies have a summarized objective to focus the budget on the projects on TRL 1–3 and water-to-hydrogen technology with an increasing budget over the years. This objective aligns with the past years of political actions, aiming to increase the green hydrogen budget with a focus on water-to-hydrogen technologies. Given that green hydrogen technology is still on a rudimentary level, these policies are crucial for the technology's development by helping to ensure steady and predictable budget planning. The policy to focus the budget on TRL 1–3 projects, which is not in line with the past years of political actions, is expected to encourage funding for projects that lead to an advance in scientific and market performance on a fundamental level.

This study's limitation is that it only analyzed projects on an individual level. Future research could expand on this by analyzing and comparing projects with varying budget sizes and outputs.

In South Korea, the year 2022 saw the inauguration of a new administration, which signifies a potential shift in policy objectives. This study shows that the demands, political actions, accumulated impacts of political actions and policies have risen and resulted in the advance in green hydrogen technology in South Korea. In order to vitalize the hydrogen economy and shift to a green hydrogen society in the future, it is necessary to continue to financially and politically support areas that are showing outstanding performance. A sturdy legal framework also helps support the steady growth of the green hydrogen economy, akin to those of the US and Germany. Research by Muhammad and Rasyikah has also shown that establishing proper legal frameworks, such as laws, can ensure government financial support for a technology [ 18 ]. The results of this study are expected to provide comprehensive insights into establishing policies in South Korea as well as foreign countries with an interest in green hydrogen-related policies. In order for foreign researchers to replicate the study, the data on governmental budget spending should be available and accessible for this type of analysis. The budget data should be also labeled with essential information such as descriptions or keywords of funded projects, the funded year, and other essential metrics.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during the current study are included in this published article. The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the National Science and Technology Information Service website at https://www.ntis.go.kr/ThMain.do .

Ochu E, Braverman S, Smith G, Friedmann S J (2021) Hydrogen Fact Sheet: Production of Low-Carbon Hydrogen. Center on Global Energy Policy, Columbia University. https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/pictures/HydrogenProduction_CGEP_FactSheet_052621.pdf . Accessed 25 Oct 2023.

Stangarone T (2021) South Korean efforts to transition to a hydrogen economy. Clean Techn Environ Policy 23:509–516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-020-01936-6

Article Google Scholar

Longden T, Beck FJ, Jotzo F, Andrews R, Prasad M (2022) Clean’ hydrogen? – Comparing the emissions and costs of fossil fuel versus renewable electricity based hydrogen. Appl Energy 306(B):118145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.118145

Oliveira AM, Beswick RR, Yan Y (2021) A green hydrogen economy for a renewable energy society. Curr Opin Chem Eng 33:100701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coche.2021.100701

Howarth RW, Jacobson MZ (2021) How green is blue hydrogen? Energy Sci Eng 9(10):1676–1687. https://doi.org/10.1002/ese3.956

Chu KH, Lim J, Mang JS, Hwang MH (2022) Evaluation of strategic directions for supply and demand of green hydrogen in South Korea. Int J Hydrogen Energ 47(3):1409–1424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.10.107

Kakoulaki G, Kougias I, Taylor N, Dolci F, Moya J, Jäger-Waldau A (2020) Green hydrogen in Europe – a regional assessment: substituting existing production with electrolysis powered by renewables. Energ Convers Manage 228:113649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113649

Karayel GK, Javani N, Dincer I (2021) Green hydrogen production potential for Turkey with solar energy. Int J Hydrogen Energy 47(45):19354–19364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.10.240

Yu M, Wang K, Vredenburg H (2021) Insights into low-carbon hydrogen production methods: Green, blue and aqua hydrogen. Int J Hydrogen Energy 46(41):21261–21273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.04.016

Meng X, Gu A, Wu X, Zhou L, Zhou J, Liu B, Mao Z (2021) Status quo of China hydrogen strategy in the field of transportation and international comparisons. Int J Hydrogen Energ 46(57):28887–28899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.11.049

Li Y, Shi X, Phoumin H (2021) A strategic roadmap for large-scale green hydrogen demonstration and commercialisation in China: a review and survey analysis. Int J Hydrogen Energ 47(58):24592–24609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.10.077

Wolf A, Zander N (2021) Green hydrogen in Europe. Do strategies meet expectations? Intereconomics - Review of European Economic Policy 56(6):316–323

Velazquez Abad A, Dodds PE (2020) Green hydrogen characterisation initiatives: definitions, standards, guarantees of origin, and challenges. Energ Policy 138:111300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111300

IEA (2019) The future of hydrogen: seizing today’s opportunities. OECD, Paris Cedex 16. https://doi.org/10.1787/1e0514c4-en

Book Google Scholar

Xiang H, Ch P, Nawaz MA, Chupradit S, Fatima A, Sadiq M (2021) Integration and economic viability of fueling the future with green hydrogen: an integration of its determinants from renewable economics. Int J Hydrogen Energ 46(77):38145–38162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.09.067

Chung Y, Hong S, Kim J (2014) Which of the technologies for producing hydrogen is the most prospective in Korea?: Evaluating the competitive priority of those in near-, mid-, and long-term. Energ Policy 65:115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.10.020

Kang MJ, Park H (2011) Impact of experience on government policy toward acceptance of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles in Korea. Energ Policy 39(6):3465–3475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.03.045

Azni MA, Khalid RM (2021) Hydrogen fuel cell legal framework in the United States, Germany, and South Korea—a model for a regulation in Malaysia. Sustainability 13(4):1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042214

Lee D, Kim K (2021) Research and development investment and collaboration framework for the hydrogen economy in South Korea. Sustainability 13(19):10686. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910686

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2023) Ministry of Foreign Affairs. https://www.mofa.go.kr . Accessed 14 Feb 2023.

Ministry of Trade Industry and Energy (2017) Renewable Energy 3020 Implementation Plan.

Ministry of Trade Industry and Energy (2020) 5th basic plan for renewable energy.

Ministry of Economy and Finance (2020) The budget for the top 40 projects in 2021.

Easton D (1957) An approach to the analysis of political systems. World Politics 9(3):383–400. https://doi.org/10.2307/2008920

Shirin SS, Bogolubova NM, Nikolaeva JV (2014) Application of David Easton’s model of political system to the world wide web Sergey Sergeevich Shirin. World Appl Sci J 30(8):1083–1087. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.wasj.2014.30.08.14115

Lee J (2015) 15. Green growth in South Korea. Handbook green growth 343–360.

O’Toole LJ (2000) Research on policy implementation: assessment and prospects. J Public Adm Res Theory 10(2):263–288. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024270

Cerna L (2013) The nature of policy change and implementation: a review of different theoretical approaches. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-343741510-4.50012-2

Van Meter DS, Van Horn CE (1975) The policy implementation process: a conceptual framework. Adm Soc 6(4):445–488. https://doi.org/10.1177/009539977500600404

Bullock HL, Lavis JN (2019) Understanding the supports needed for policy implementation: a comparative analysis of the placement of intermediaries across three mental health systems. Health Res Policy Syst 17(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0479-1

Haque N (2017) Technology mandate for greening brick industry in Bangladesh: a policy evaluation. Clean Technol Envir 2:319–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-016-1259-z

Ali S, Ahmed W, Solangi YA, Chaudhry IS, Zarei N (2022) Strategic analysis of single-use plastic ban policy for environmental sustainability: the case of Pakistan. Clean Technol Envir 24(3):843–849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-020-02011-w

Jana A, Sarkar A, Thomas N, Krishna Priya GS, Bandyopadhyay S, Crosbie T, Abi Ghanem D, Waller G, Pillai GG, Newbury-Birch D (2021) Rethinking water policy in India with the scope of metering towards sustainable water future. Clean Technol Envir 23(8):2471–2495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-021-02167-z

Liu X, Xie F, Wang H, Xue C (2021) The impact of policy mixes on new energy vehicle diffusion in China. Clean Technol Envir 23(5):1457–1474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10098-021-02040-z

Chungwon W, Chun D (2018) A study on examining the impact of science and technology policy mix on R&D efficiency. Korea Technol Innov Soc 21(4):1268–1295

Google Scholar

NTIS (2020) Overview of the National R&D Project Performance Analysis.

Ministry of Trade Industry and Energy (2018) Report of the Ministry of Industry and Energy in 2019

Ministerial meeting on science and technology (2019) Roadmap for development of hydrogen energy. in: Afore, 43. http://www.motie.go.kr . Accessed 14 Feb 2023

Joint operation of related ministries (2019) Roadmap to revitalize the hydrogen economy. 17:8. http://www.motie.go.kr/common/download.do?fid=bbs&bbs_cd_n=81&bbs_seq_n=161262&file_seq_n=2 . Accessed 14 Feb 2023

Joint ministries (2020) The Korean Version of the New Deal Comprehensive Plan

Ministry of Science and ICT (2021) Climate/Environmental R&D project plan for 2021. http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/1/1/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=388115 . Accessed 14 Feb 2023.

Joint ministries (2021) 2050 Carbon Neutral Scenario

Joint ministries (2021) Energy carbon neutral innovation strategy

Ministry of Trade Industry and Energy (2021) Carbon neutral industrial energy R&D strategy

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr. Mike R. Giodano in proofreading the manuscript.

This research was supported by the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information (KISTI) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No.K-23-L03-C04: Development and Utilization of Innovation Strategy Analysis Models for the Science and Technology Industry).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for R&D Investment and Strategy Research, Korea Institute of Science and Technology, Innovation (KISTI), Seoul, South Korea

Minyoung Yun, Wooseok Jang, Jongyeon Lim & Bitnari Yun

Strategic Planning Team, Institut Pasteur Korea, Gyeonggi-do, South Korea

Bitnari Yun

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Material preparation and data collection were performed by MY and data analysis was performed by BY. The first draft of the manuscript was written by MY and BY. MY, WJ, JL and BY commented on the first draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bitnari Yun .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Yun, M., Jang, W., Lim, J. et al. A study on a political system for the advance in green hydrogen technology: a South Korea case study. Energ Sustain Soc 13 , 43 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13705-023-00419-y

Download citation

Received : 27 September 2022

Accepted : 26 October 2023

Published : 01 December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13705-023-00419-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Hydrogen energy

- Renewable energy

- Green hydrogen

Energy, Sustainability and Society

ISSN: 2192-0567

- General enquiries: [email protected]

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Seoul's urban planning during the mid-20th century focused on economic growth and largely ignored the ecological implications of sealing away a natural waterway. By the late 20th century,...

After a steady, decades-long rise, South Korea gained new soft power potential in 2020 that, if used correctly, will enhance its influence on the international stage. This multiauthor compilation demonstrates that South Korean soft power has promise, even though it cannot replace hard power.

The Seoul Metropolitan Government decided to dismantle the 10-lane roadway and the 4-lane elevated highway that carried over 170,000 vehicles daily along the Cheonggyecheon stream. The transformed street encourages transit use over private car use, and more environmentally sustainable, pedestrian oriented public space.

Hoping to spur economic growth by providing new recreation options to residents and solve the city’s chronic runoff problems, The Seoul Metropolitan Government decided to do something bold.

For over a decade, architects and urban planners worked hand in hand to create Songdo, a brand new business district that sought to represent South Korean advancements in technology and...

This study focuses on South Korea's actions and policies, using a political system model to better understand the shift towards a green hydrogen economy. The analysis shows that budgeting for R&D projects has had a significant impact on scientific breakthroughs, advancements, and product development in the field of green hydrogen in South Korea.

South Korea was one of the first countries other than China to record a Covid-19 case in January 2020. Till the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid-19 as a global pandemic on the 11th of March the total number of confirmed cases in Korea had exceeded 7755 patients.

This case study provides background information for discussion on how TOPIS provides a useful source of evidence for decision-makers as they operate and improve Seoul’s urban transportation system.

This case study was made possible by the support of Korea’s Ministry of Finance and Economy and the World Bank Group Korea office. This report was authored by a team from the Seoul National University, School of Public Health,

This article aims to show, using the example of South Korea, the importance of the state’s cultural policy as a factor that is conducive to economic success and an increase in the standard of living of a society.