- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

- Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

Literature Review vs Research Paper: What’s the Difference?

0 Comments

by Antony W

September 11, 2022

This is a complete student’s guide to understanding literature review vs research paper.

We’ll teach you what they’re, explain why they’re important, state the difference between the two, and link you to our comprehensive guide on how to write them.

Literature Review Writing Help

Writing a literature review for a thesis, a research paper, or as a standalone assignment takes time. Much of your time will go into research, not to mention you have other assignments to complete.

If you find writing in college or university overwhelming, get in touch with our literature review writers for hire at 25% discounts and enjoy the flexibility and convenience that comes with professional writing help. We’ll help you do everything, from research and outlining to custom writing and proofreading.

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review document is a secondary source of information that provides an overview of existing knowledge, which you can use to identify gaps or flaws in existing research. In literature review writing, students have to find and read existing publications such as journal articles, analyze the information, and then state their findings.

Credit: Pubrica

You’ll write a literature review to demonstrate your understanding on the topic, show gaps in existing research, and develop an effective methodology and a theoretical framework for your research project.

Your instructor may ask you to write a literature review as a standalone assignment. Even if that’s the case, the rules for writing a review paper don’t change.

In other words, you’ll still focus on evaluating the current research and find gaps around the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

There are three types of review papers and they’re a follows:

1. Meta-analysis

In meta-analysis review paper, you combine and compare answers from already published studies on a given subject.

2. Narrative Review

A narrative review paper looks into existing information or research already conducted on a given topic.

3. Systematic Review

You need to do three things if asked to write a systematic review paper.

First, read and understand the question asked. Second, look into research already conducted on the topic. Third, search for the answer to the question from the established research you just read.

What’s a Research Paper?

A research paper is an assignment in which you present your own argument, evaluation, or interpretation of an issue based on independent research.

In a research paper project, you’ll draw some conclusions from what experts have already done, find gaps in their studies, and then draw your own conclusions.

While a research paper is like an academic essay, it tends to be longer and more detailed.

Since they require extended research and attention to details, research papers can take a lot of time to write.

If well researched, your research paper can demonstrate your knowledge about a topic, your ability to engage with multiple sources, and your willingness to contribute original thoughts to an ongoing debate.

Types of Research Papers

There are two types of research papers and they’re as follows:

1. Analytical Research Papers

Similar to analytical essay , and usually in the form of a question, an analytical research paper looks at an issue from a neutral point and gives a clear analysis of the issue.

Your goal is to make the reader understand both sides of the issue in question and leave it to them to decide what side of the analysis to accept.

Unlike an argumentative research paper, an analytical research paper doesn’t include counterarguments. And you can only draw your conclusion based on the information stretched out all through the analysis.

2. Argumentative Research Papers

In an argumentative research paper, you state the subject under study, look into both sides of an issue, pick a stance, and then use solid evidence and objective reasons to defend your position.

In argumentative writing, your goal isn’t to persuade your audience to take an action.

Rather, it’s to convince them that your position on the research question is more accurate than the opposing point of views.

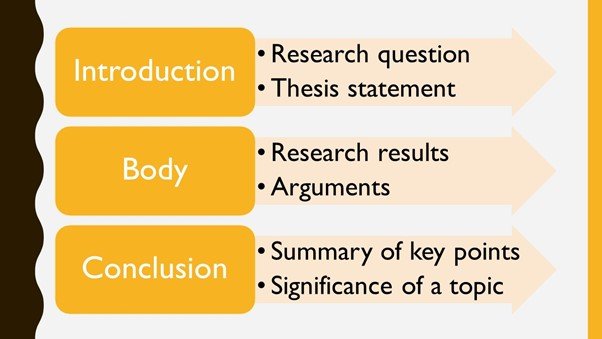

Regardless of the type of research paper that you write, you’ll have to follow the standard outline for the assignment to be acceptable for review and marking.

Also, all research paper, regardless of the research question under investigation must include a literature review.

Literature Review vs Research Paper

The table below shows the differences between a literature review (review paper) and a research paper.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. is there a literature review in a research paper.

A research paper assignment must include a literature review immediately after the introduction chapter.

The chapter is significant because your research work would otherwise be incomplete without knowledge of existing literature.

2. How Many Literature Review Should Be in Research Paper?

Your research paper should have only one literature review. Make sure you write the review based on the instructions from your teacher.

Before you start, check the required length, number of sources to summarize, and the format to use. Doing so will help you score top grades for the assignment.

3. What is the Difference Between Research and Literature?

Whereas literature focuses on gathering, reading, and summarizing information on already established studies, original research involves coming up with new concepts, theories, and ideas that might fill existing gaps in the available literature.

4. How Long is a Literature Review?

How long a literature review should be will depend on several factors, including the level of education, the length of the assignment, the target audience, and the purpose of the review.

For example, a 150-page dissertation can have a literature review of 40 pages on average.

Make sure you talk to your instructor to determine the required length of the assignment.

5. How Does a Literature Review Look Like?

Your literature review shouldn’t be a focus on original research or new information. Rather, it should give a clear overview of the already existing work on the selected topic.

The information to review can come from various sources, including scholarly journal articles , government reports, credible websites, and academic-based books.

About the author

Antony W is a professional writer and coach at Help for Assessment. He spends countless hours every day researching and writing great content filled with expert advice on how to write engaging essays, research papers, and assignments.

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Reviewing Research: Literature Reviews, Scoping Reviews, Systematic Reviews

- Differentiating the Three Review Types

Reviewing Research: Literature Reviews, Scoping Reviews, Systematic Reviews: Differentiating the Three Review Types

- Framework, Protocol, and Writing Steps

- Working with Keywords/Subject Headings

- Citing Research

The Differences in the Review Types

Grant, M.J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. H ealth Information & Libraries Journal , 26: 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x The objective of this study is to provide descriptive insight into the most common types of reviews, with illustrative examples from health and health information domains.

- What Type of Review is Right for you (Cornell University)

Literature Reviews

Literature Review: it is a product and a process.

As a product , it is a carefully written examination, interpretation, evaluation, and synthesis of the published literature related to your topic. It focuses on what is known about your topic and what methodologies, models, theories, and concepts have been applied to it by others.

The process is what is involved in conducting a review of the literature.

- It is ongoing

- It is iterative (repetitive)

- It involves searching for and finding relevant literature.

- It includes keeping track of your references and preparing and formatting them for the bibliography of your thesis

- Literature Reviews (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) This handout will explain what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

Scoping Reviews

Scoping reviews are a " preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature . Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research)." Grant and Booth (2009).

Scoping reviews are not mapping reviews: Scoping reviews are more topic based and mapping reviews are more question based.

- examines emerging evidence when specific questions are unclear - clarify definitions and conceptual boundaries

- identifies and maps the available evidence

- to summarize and disseminate research findings in the research literature

- identify gaps with the intention of resolution by future publications

- a scoping review can be done prior to a systematic review

- Scoping review timeframe and limitations (Touro College of Pharmacy

Systematic Reviews

Many evidence-based disciplines use ‘systematic reviews," this type of review is a specific methodology that aims to comprehensively identify all relevant studies on a specific topic, and to select appropriate studies based on explicit criteria . ( https://cebma.org/faq/what-is-a-systematic-review/ )

- clearly defined search criteria

- an explicit reproducible methodology

- a systematic search of the literature with the defined criteria met

- assesses validity of the findings

- a comprehensive report on the findings, apparent transparency in the results

- Better evidence for a better world Browsable collection of systematic reviews

- Systematic Reviews in the Health Sciences by Molly Maloney Last Updated Oct 28, 2024 1352 views this year

- Next: Framework, Protocol, and Writing Steps >>

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

- Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

- 3 minute read

- 72.3K views

Table of Contents

As a researcher, you may be required to conduct a literature review. But what kind of review do you need to complete? Is it a systematic literature review or a standard literature review? In this article, we’ll outline the purpose of a systematic literature review, the difference between literature review and systematic review, and other important aspects of systematic literature reviews.

What is a Systematic Literature Review?

The purpose of systematic literature reviews is simple. Essentially, it is to provide a high-level of a particular research question. This question, in and of itself, is highly focused to match the review of the literature related to the topic at hand. For example, a focused question related to medical or clinical outcomes.

The components of a systematic literature review are quite different from the standard literature review research theses that most of us are used to (more on this below). And because of the specificity of the research question, typically a systematic literature review involves more than one primary author. There’s more work related to a systematic literature review, so it makes sense to divide the work among two or three (or even more) researchers.

Your systematic literature review will follow very clear and defined protocols that are decided on prior to any review. This involves extensive planning, and a deliberately designed search strategy that is in tune with the specific research question. Every aspect of a systematic literature review, including the research protocols, which databases are used, and dates of each search, must be transparent so that other researchers can be assured that the systematic literature review is comprehensive and focused.

Most systematic literature reviews originated in the world of medicine science. Now, they also include any evidence-based research questions. In addition to the focus and transparency of these types of reviews, additional aspects of a quality systematic literature review includes:

- Clear and concise review and summary

- Comprehensive coverage of the topic

- Accessibility and equality of the research reviewed

Systematic Review vs Literature Review

The difference between literature review and systematic review comes back to the initial research question. Whereas the systematic review is very specific and focused, the standard literature review is much more general. The components of a literature review, for example, are similar to any other research paper. That is, it includes an introduction, description of the methods used, a discussion and conclusion, as well as a reference list or bibliography.

A systematic review, however, includes entirely different components that reflect the specificity of its research question, and the requirement for transparency and inclusion. For instance, the systematic review will include:

- Eligibility criteria for included research

- A description of the systematic research search strategy

- An assessment of the validity of reviewed research

- Interpretations of the results of research included in the review

As you can see, contrary to the general overview or summary of a topic, the systematic literature review includes much more detail and work to compile than a standard literature review. Indeed, it can take years to conduct and write a systematic literature review. But the information that practitioners and other researchers can glean from a systematic literature review is, by its very nature, exceptionally valuable.

This is not to diminish the value of the standard literature review. The importance of literature reviews in research writing is discussed in this article . It’s just that the two types of research reviews answer different questions, and, therefore, have different purposes and roles in the world of research and evidence-based writing.

Systematic Literature Review vs Meta Analysis

It would be understandable to think that a systematic literature review is similar to a meta analysis. But, whereas a systematic review can include several research studies to answer a specific question, typically a meta analysis includes a comparison of different studies to suss out any inconsistencies or discrepancies. For more about this topic, check out Systematic Review VS Meta-Analysis article.

Language Editing Plus

With Elsevier’s Language Editing Plus services , you can relax with our complete language review of your systematic literature review or literature review, or any other type of manuscript or scientific presentation. Our editors are PhD or PhD candidates, who are native-English speakers. Language Editing Plus includes checking the logic and flow of your manuscript, reference checks, formatting in accordance to your chosen journal and even a custom cover letter. Our most comprehensive editing package, Language Editing Plus also includes any English-editing needs for up to 180 days.

How to Make a PowerPoint Presentation of Your Research Paper

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Craft a Strong Research Hypothesis

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

How to Write a Literature Review

- What is a literature review

How is a literature review different from a research paper?

- What should I do before starting my literature review?

- What type of literature review should I write and how should I organize it?

- What should I be aware of while writing the literature review?

- For more information on Literature Reviews

- More Research Help

The purpose of an academic research paper is to develop a new argument. The literature review is one part of a research paper. In a research paper, you use the literature review as a foundation and as support for the new insight that you contribute. The focus of a literature review, however, is to summarize and analyze the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions.

- << Previous: What is a literature review

- Next: What should I do before starting my literature review? >>

- Last Updated: Feb 26, 2021 11:35 AM

- URL: https://midway.libguides.com/LiteratureReview

RESEARCH HELP

- Research Guides

- Databases A-Z

- Journal Search

- Citation Help

LIBRARY SERVICES

- Accessibility

- Interlibrary Loan

- Study Rooms

INSTRUCTION SUPPORT

- Course Reserves

- Library Instruction

- Little Memorial Library

- 512 East Stephens Street

- 859.846.5316

- [email protected]

- Study resources

- Calendar - Graduate

- Calendar - Undergraduate

- Class schedules

- Class cancellations

- Course registration

- Important academic dates

- More academic resources

- Campus services

- IT services

- Job opportunities

- Safety & prevention

- Mental health support

- Student Service Centre (Birks)

- All campus services

- Calendar of events

- Latest news

- Media Relations

- Faculties, Schools & Colleges

- Arts and Science

- Gina Cody School of Engineering and Computer Science

- John Molson School of Business

- School of Graduate Studies

- All Schools, Colleges & Departments.

- Directories

- My Library Account (Sofia) View checkouts, fees, place requests and more

- Interlibrary Loans Request books from external libraries

- Zotero Manage your citations and create bibliographies

- E-journals via BrowZine Browse & read journals through a friendly interface

- Article/Chapter Scan & Deliver Request a PDF of an article/chapter we have in our physical collection

- Course Reserves Online course readings

- Spectrum Deposit a thesis or article

- WebPrint Upload documents to print with DPrint

- Sofia Discovery tool

- Databases by subject

- Course Reserves

- E-journals via Browzine

- E-journals via Sofia

- Article/chapter scan

- Intercampus delivery of bound periodicals/microforms

- Interlibrary loans

- Spectrum Research Repository

- Special Collections & Archives

- Additional resources & services

- Subject & course guides

- Borrowing & renewing

- Open Educational Resources Guide

- Instructional Services

- General guides for users

- Ask a librarian

- Research Skills Tutorial

- Quick Things for Digital Knowledge

- Critical Toolkit for Navigating Information

- Bibliometrics & research impact guide

- Concordia University Press

- Copyright guide

- Copyright guide for thesis preparation

- Digital scholarship

- Digital preservation

- Open at Concordia

- ORCiD at Concordia

- Research data management guide

- Scholarship of Teaching & Learning

- Systematic Reviews

- Borrow (laptops, tablets, equipment)

- Connect (netname, Wi-Fi, guest accounts)

- Desktop computers, software & availability maps

- Group study, presentation practice & classrooms

- Printers, copiers & scanners

- Technology Sandbox

- Visualization Studio

- Webster Library

- Vanier Library

- Grey Nuns Reading Room

- Study spaces

- Floor plans

- Book a group study room/scanner

- Room booking for academic events

- Exhibitions

- Librarians & staff

- Work with us

- Memberships & collaborations

- Indigenous Student Librarian program

- Wikipedian in residence

- Researcher in residence

- Feedback & improvement

- Annual reports & fast facts

- Strategic Plan 2016/21

- Library Services Fund

- Giving to the Library

- Policies & Code of Conduct

- My Library Account (Sofia)

- Interlibrary Loans

- E-journals via BrowZine

- Article/Chapter Scan & Deliver

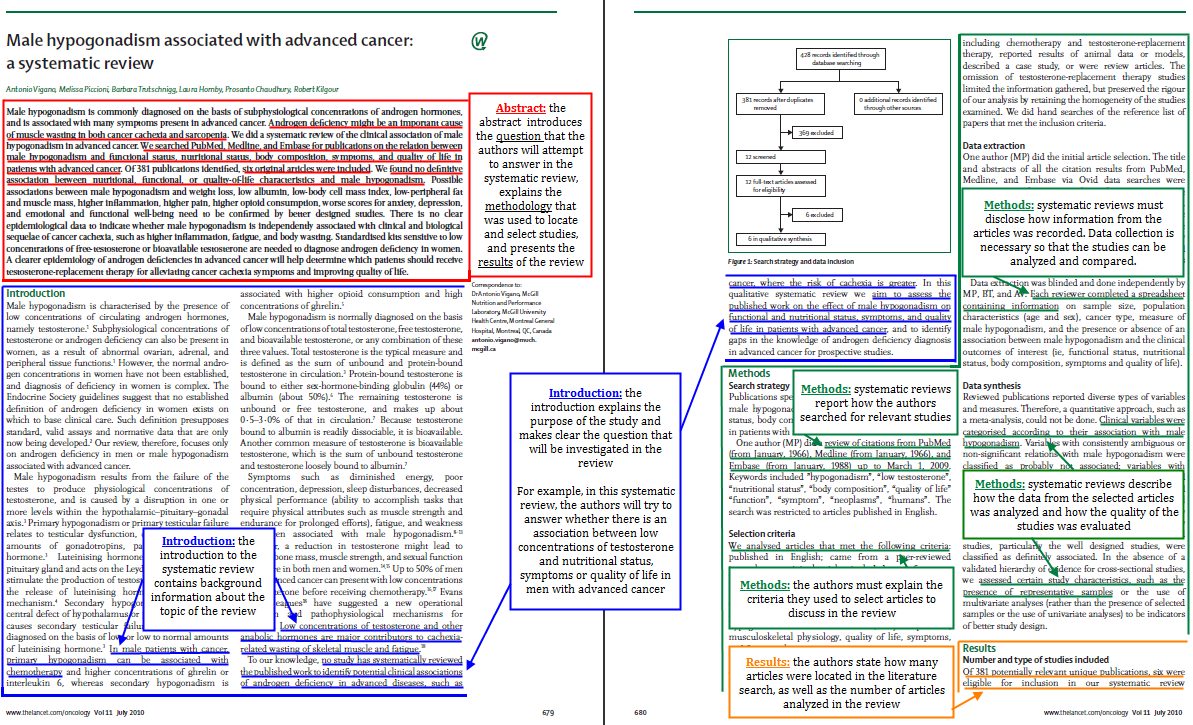

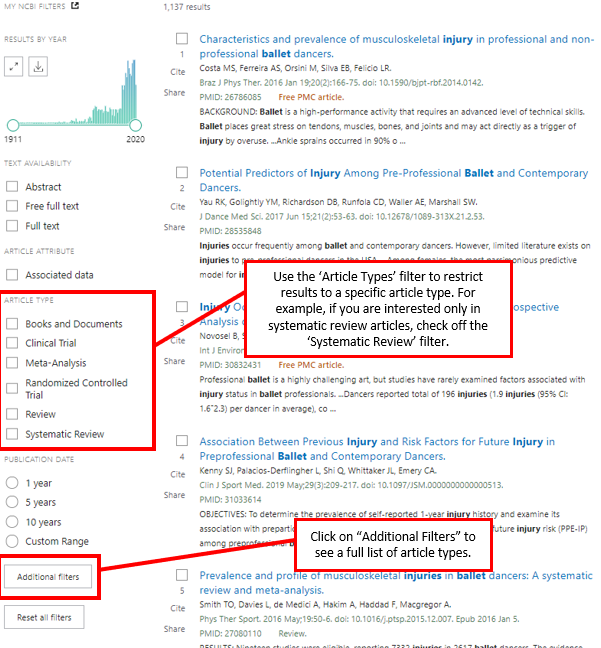

Review vs. Research Articles

How can you tell if you are looking at a research paper, review paper or a systematic review examples and article characteristics are provided below to help you figure it out., research papers.

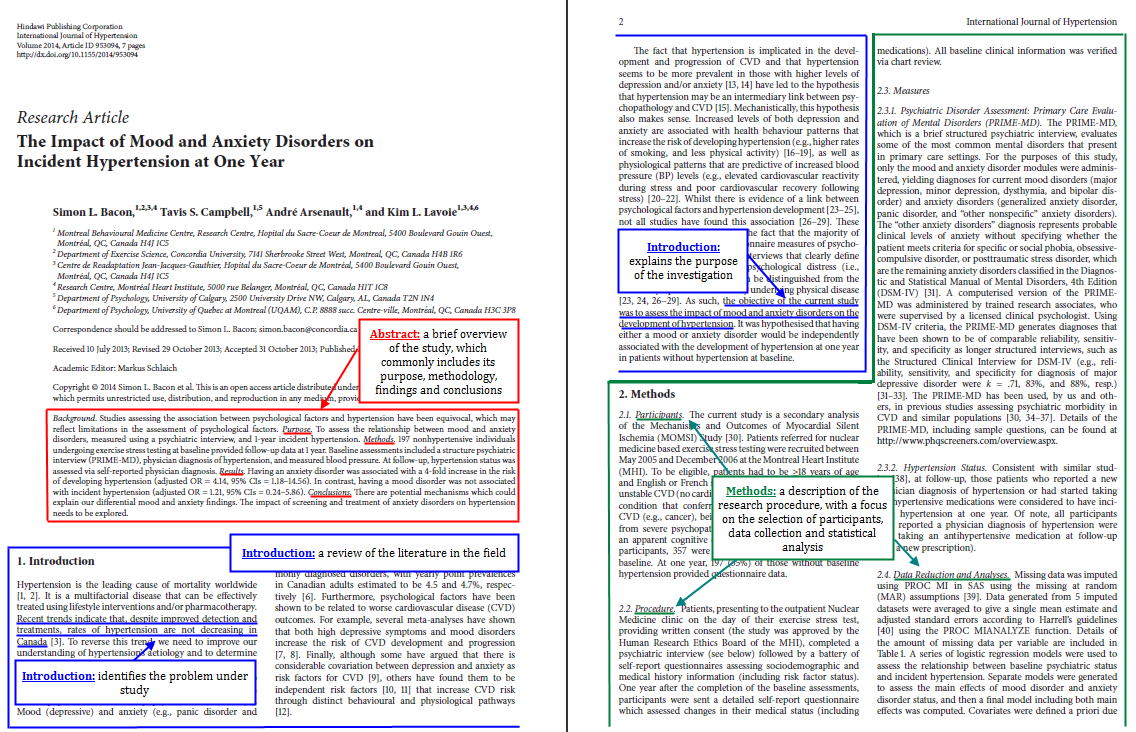

A research article describes a study that was performed by the article’s author(s). It explains the methodology of the study, such as how data was collected and analyzed, and clarifies what the results mean. Each step of the study is reported in detail so that other researchers can repeat the experiment.

To determine if a paper is a research article, examine its wording. Research articles describe actions taken by the researcher(s) during the experimental process. Look for statements like “we tested,” “I measured,” or “we investigated.” Research articles also describe the outcomes of studies. Check for phrases like “the study found” or “the results indicate.” Next, look closely at the formatting of the article. Research papers are divided into sections that occur in a particular order: abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and references.

Let's take a closer look at this research paper by Bacon et al. published in the International Journal of Hypertension :

Review Papers

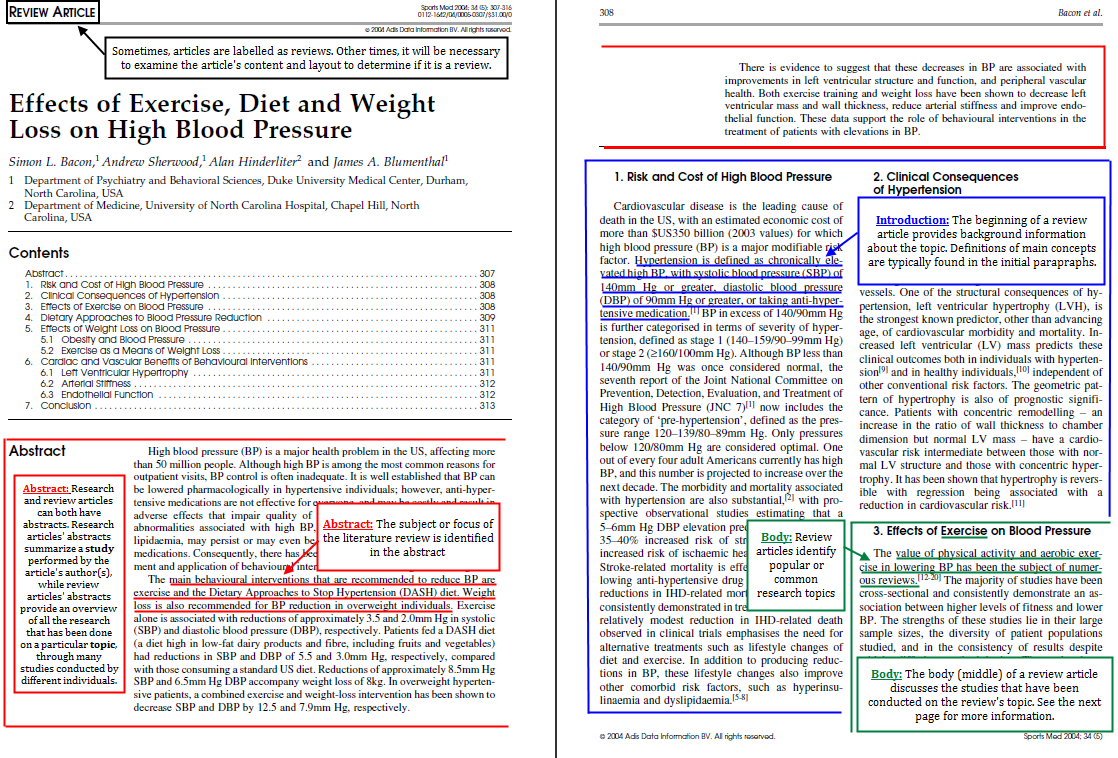

Review articles do not describe original research conducted by the author(s). Instead, they give an overview of a specific subject by examining previously published studies on the topic. The author searches for and selects studies on the subject and then tries to make sense of their findings. In particular, review articles look at whether the outcomes of the chosen studies are similar, and if they are not, attempt to explain the conflicting results. By interpreting the findings of previous studies, review articles are able to present the current knowledge and understanding of a specific topic.

Since review articles summarize the research on a particular topic, students should read them for background information before consulting detailed, technical research articles. Furthermore, review articles are a useful starting point for a research project because their reference lists can be used to find additional articles on the subject.

Let's take a closer look at this review paper by Bacon et al. published in Sports Medicine :

Systematic Review Papers

A systematic review is a type of review article that tries to limit the occurrence of bias. Traditional, non-systematic reviews can be biased because they do not include all of the available papers on the review’s topic; only certain studies are discussed by the author. No formal process is used to decide which articles to include in the review. Consequently, unpublished articles, older papers, works in foreign languages, manuscripts published in small journals, and studies that conflict with the author’s beliefs can be overlooked or excluded. Since traditional reviews do not have to explain the techniques used to select the studies, it can be difficult to determine if the author’s bias affected the review’s findings.

Systematic reviews were developed to address the problem of bias. Unlike traditional reviews, which cover a broad topic, systematic reviews focus on a single question, such as if a particular intervention successfully treats a medical condition. Systematic reviews then track down all of the available studies that address the question, choose some to include in the review, and critique them using predetermined criteria. The studies are found, selected, and evaluated using a formal, scientific methodology in order to minimize the effect of the author’s bias. The methodology is clearly explained in the systematic review so that readers can form opinions about the quality of the review.

Let's take a closer look this systematic review paper by Vigano et al. published in Lancet Oncology :

Finding Review and Research Papers in PubMed

Many databases have special features that allow the searcher to restrict results to articles that match specific criteria. In other words, only articles of a certain type will be displayed in the search results. These “limiters” can be useful when searching for research or review articles. PubMed has a limiter for article type, which is located on the left sidebar of the search results page. This limiter can filter the search results to show only review articles.

© Concordia University

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Systematic Review vs. Literature Review

4-minute read

- 28th October 2023

If you’ve been reading research papers, chances are you’ve come across two commonly used approaches to synthesizing existing knowledge: systematic reviews and literature reviews. Although they share similarities, it’s important to understand their differences to help you choose the most appropriate method for your research needs.

In this blog post, we’ll outline the key distinctions between systematic reviews and literature reviews, so that you can make an informed decision about which approach to include in your research plan . Let’s begin!

Objective and Purpose

The primary objective of a literature review is to provide an overview and summary of the existing literature on a specific topic to set the stage for your own critical evaluation . A literature review aims to identify key concepts, theories, and research findings, as well as gaps in knowledge, to establish a foundation for further studies.

On the other hand, systematic reviews have a more focused purpose. They aim to address a particular research question using a predefined methodology and criteria for study selection. Systematic reviews seek to provide a comprehensive and objective summary of the available evidence in order to draw significant conclusions.

Methodology and Process

Literature reviews often adopt a flexible and iterative approach. They utilize the analysis, evaluation, and summarization of relevant research or scholarly literature, such as journal articles, books, and conference proceedings. Researchers use various search strategies and sources to gather the material; selection criteria may be loosely defined. When undertaking the literature review, qualitative techniques are often used to identify patterns and themes.

In contrast, systematic reviews follow a more structured and replicable process. After your key research question has been fully developed, it can often be helpful to follow an analytic framework to guide your research. Extensive literature searches across multiple databases are conducted using predefined search terms and strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. Researchers critically assess the quality of research and risk of bias in each study, systematically extract and analyze the data, and may employ statistical methods, such as meta-analysis , to synthesize the findings.

Outcomes and Findings

The outcomes of literature reviews primarily include a summary of the existing literature, key findings, useful methodologies, and identified research gaps . These reviews provide a broad understanding of the current state of knowledge in a particular area and can help researchers identify directions for future studies. Literature reviews aim to describe and analyze the existing research rather than providing definitive conclusions or making recommendations.

Systematic reviews, however, produce more conclusive results. They statistically analyze the data from selected studies, often incorporating meta-analysis, in order to answer the key research question. Systematic review findings often include a summary of findings table to communicate the main outcomes as well as information about the materials that were covered in the review.

Applicability and Utility

Due to their broad nature, literature reviews are useful for researchers looking to gain an overview of a specific field or topic. They provide a foundation for understanding existing knowledge, identifying gaps, and generating research questions. Literature reviews tend to be used in the early stages of research projects or when developing theoretical frameworks for a thesis or dissertation.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

With their rigorous methodology, systematic reviews are valuable for informing evidence-based practice and decision-making. They can be used as stand-alone scientific publications to illustrate the current state of scientific evidence, set a research agenda, or inform policy-making.

If you’re trying to decide whether a systematic review or literature review is the best approach for your project, consider the main distinctions:

1. Literature reviews offer a broad overview of the existing literature and identify research gaps, while systematic reviews focus on answering a specific research question.

2. Literature reviews commonly adopt a flexible and iterative approach, while systematic reviews use a structured and rigorous approach.

3. Literature reviews identify key findings, useful methodologies, and identified research gaps. Systematic reviews, on the other hand, produce conclusive results to answer the key research question.

4. Literature reviews are often carried out early on in a thesis or dissertation to identify existing research gaps, whereas systematic reviews can stand on their own as a conclusive analysis.

Once you understand these differences, you’re ready to choose the best approach for your own research paper.

And if you’re interested in getting help with proofreading your research paper, consider our research paper editing services . You can even try a sample of our services for free . Good luck reviewing and researching!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

5-minute read

Free Email Newsletter Template

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Penn State University Libraries

- Home-Articles and Databases

- Asking the clinical question

- PICO & Finding Evidence

- Evaluating the Evidence

- Systematic Review vs. Literature Review

- Fall 2024 Workshops

- Nursing Library Instruction Course

- Ethical & Legal Issues for Nurses

- Useful Nursing Resources

- Writing Resources

- LionSearch and Finding Articles

- The Catalog and Finding Books

Know the Difference! Systematic Review vs. Literature Review

It is common to confuse systematic and literature reviews as both are used to provide a summary of the existent literature or research on a specific topic. Even with this common ground, both types vary significantly. Please review the following chart (and its corresponding poster linked below) for the detailed explanation of each as well as the differences between each type of review.

- What's in a name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters by Lynn Kysh, MLIS, University of Southern California - Norris Medical Library

- << Previous: Evaluating the Evidence

- Next: Fall 2024 Workshops >>

- Last Updated: Dec 16, 2024 7:53 AM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/nursing

Systematic review vs literature review

23 October 2024

Magda Wojcik

The difference between systematic review vs literature review lies in the structured, thorough methodology of a systematic review, which comprehensively evaluates evidence on a specific research question. In contrast, a literature review offers a broader summary of existing research without following a rigid process. In short, systematic reviews aim for completeness and objectivity, while literature reviews are more subjective and less exhaustive. A literature review is typically part of a larger work, like a dissertation or journal article introduction, whereas a systematic review is usually a standalone publication designed to answer a focused research question thoroughly.

Read this blog post to understand the main differences between a systematic review vs literature review, including when and how to use each approach in academic and professional settings. It also explains the structure, methodology and purpose of both review types and discusses their applications in research. Additionally, readers will learn about the processes involved in preparing these reviews for publication, from selecting relevant studies to organising and presenting findings effectively.

What is a literature review?

- Literature review structure

What is a systematic review?

- Systematic review structure

Similarities

Differences, resources for writing a literature review, resources for writing a systematic review.

- Using editing services to improve a literature or systematic review

A literature review is a comprehensive summary and analysis of existing research, theories and published materials on a particular topic. It aims to provide an overview of the current knowledge, identify gaps and highlight critical findings or trends in the literature. In academic writing, literature reviews contextualise research within the broader field and support the development of new studies or arguments.

A literature review is best suited when the goal is to provide a general overview of a research topic, summarise key studies or discuss trends, theories and gaps in a field. It is appropriate for introductory sections of theses, dissertations or journal articles where a broad context is needed without requiring comprehensive coverage of every study.

Examples of literature review applications include:

- Introduction to a dissertation or thesis

- Background section of a journal article

- Literature review chapter in a research report

- Contextual section in a grant or funding proposal

- Preliminary review for a theoretical paper or conceptual framework

- White paper or policy report introduction

- Conference presentation on trends in a specific field

- Background chapter in a textbook or monograph

- Review section for a course syllabus or academic curriculum design

- Preface to a research monograph or an edited volume

Structure of a literature review

The structure of a literature review typically includes an introduction, theoretical framework/background, a thematic, chronological or methodological discussion of relevant studies, analysis and synthesis and conclusion. Here is a more in-depth explanation of these components of a literature review:

- Introduction briefly introduces the topic, outlines the objectives of the review and explains the importance of the literature being reviewed. It may also state the scope of the review and the criteria for selecting the literature.

- Theoretical framework or background provides a foundation for the topic by explaining fundamental concepts, theories and definitions that frame the review.

- Themes or categories : The main body of the literature review is often organised thematically, chronologically or methodologically. Each section may summarise and synthesise key studies by comparing and contrasting different findings, perspectives or approaches.

- Critical analysis and synthesis discuss the strengths, weaknesses and gaps in the literature. This section evaluates the quality of the studies and how they contribute to understanding the topic.

- Conclusion summarises the key insights of the review and highlights the main trends, gaps and areas for future research. It may also propose how the reviewed literature informs the current study or recommend new research directions.

- References list all the sources cited in the review, formatted according to a specified referencing style (e.g. APA, MLA).

A systematic review is a rigorous and structured method of reviewing existing research on a specific question or topic. It involves a well-defined process of identifying, selecting and critically evaluating all relevant studies. This analysis is followed by a synthesis of the findings in a transparent and replicable way. Systematic reviews aim to minimise bias and summarise objectively the best available evidence. For this reason, they are often used to guide decision-making in healthcare, policy and other fields.

A systematic review is necessary when there is a need to answer precisely a specific research question. Examples of application of systematic review include:

- Standalone systematic review article in a scientific journal

- Evidence synthesis in healthcare guidelines or clinical practice documents

- Meta-analysis for a PhD thesis in fields like medicine or psychology

- Basis for a Cochrane review in medical or health policy research

- Background for a government or non-profit report on intervention effectiveness

- Systematic review section in a research funding proposal

- Regulatory or policy decision reports

- Systematic review component in academic peer-reviewed books

- Pre-registration protocols for clinical trials or experimental studies

- Formal review section in policy-making documents for evidence-based legislation

Structure of a systematic review

The structure of a systematic review typically has a highly organised and detailed format to ensure transparency and replicability. The key sections are introduction, methods, results, discussion and conclusion. Here is a breakdown of each section:

- Introduction provides background information on the topic and outlines the research question or objective. It explains the importance of the review and may mention gaps in current research that the systematic review aims to address.

- Search strategy describes how the literature search was conducted, including databases used (e.g. PubMed , Scopus ), search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria for selecting studies.

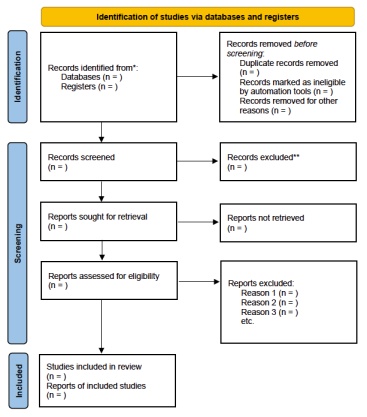

- Study selection details the process for screening and selecting studies (e.g. PRISMA flowchart), including how many studies were identified, screened and ultimately included.

- Data extraction outlines the procedure for extracting relevant data from the studies (e.g. study design, sample size, outcome measures).

- Quality assessment describes how the quality of the included studies was assessed (e.g. using tools like Cochrane Risk of Bias ).

- Results section summarises the key findings of the included studies. It often includes tables to present detailed data (e.g. study characteristics, outcomes). It may also discuss the diversity of content across the studies and the results of any meta-analysis if conducted.

- Discussion interprets the results, highlighting key patterns, strengths and limitations of the included studies. The discussion should also contextualise the findings within the broader literature and address any conflicting evidence.

- Conclusion summarises the key takeaways from the review, including implications for practice, policy or future research. It may also recommend areas where further research is needed.

- References list all the sources cited throughout the systematic review.

- Supplementary materials (if relevant) include appendices or supplementary materials such as search strategies, data extraction forms or detailed quality assessment tables.

Systematic review vs literature reviews

When comparing a systematic review vs literature review, a systematic review is more structured, objective and time-consuming, and it focuses on a specific research question with a rigorous methodology, while a literature review is more flexible and narrative-driven and offers a broader overview of a topic.

- Purpose : Both reviews aim to summarise and evaluate existing research on a particular topic or research question.

- Activities involved : Both require searching for relevant literature, reviewing studies, analysing findings and synthesising information.

- Usage : Both are used to contextualise new research, identify gaps in the literature and provide an overview of current knowledge.

- Systematic review : To provide a comprehensive, unbiased and replicable synthesis of all available evidence on a specific research question, often used to inform decision-making in healthcare and policy.

- Literature review : To provide a general summary of what is known about a topic, identifying trends, gaps and critical studies, often used as a background or theoretical foundation for research.

Tasks involved

- Systematic review : Follows a structured methodology, including developing a research question, defining inclusion/exclusion criteria, conducting exhaustive database searches, assessing study quality and synthesising results quantitatively or qualitatively.

- Literature review : Involves selecting relevant studies based on the author’s judgement, often without predefined criteria. It may focus on summarising key works and discussing theoretical perspectives without standardising the process.

- Systematic review : Primarily used in evidence-based fields like medicine, psychology and social sciences to guide clinical or policy decisions.

- Literature review : Common across disciplines, used in the introduction of research papers, theses and dissertations to provide context and show the state of research in the area.

- Systematic review : Highly structured, including sections like introduction, methods (search strategy, study selection, quality assessment), results and discussion.

- Literature review : More flexible structure, often divided by themes, trends or chronological order, without rigid methodological requirements.

Methodology

- Systematic review : Follows a predefined, transparent methodology with clear inclusion/exclusion criteria, quality assessment of studies and a replicable process.

- Literature review : Methodology is often subjective, with the scope and selection of literature based on the author’s discretion, making it less replicable.

- Systematic review : Narrow scope, focused on a specific research question and aims to include all relevant studies that meet the inclusion criteria.

- Literature review : Broad scope, covering various aspects of a topic, often highlighting significant theories, methods and studies without aiming for completeness.

Time and structure

- Literature review : Less time-consuming, flexible in structure, with no rigid methodological rules.

- Systematic review : More time-intensive, with a highly structured and transparent approach that can be replicated.

- Google Scholar , JSTOR and Scopus : For finding relevant academic articles and studies

- EndNote , Zotero or Mendeley : For reference management and source organisation

- Cite This for Me : For generating citations in various formats

- Purdue OWL : For guidelines for academic writing and citation styles

- The Literature Review: Six Steps to Success by Lawrence A. Machi and Brenda T. McEvoy

- Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper by Arlene Fink

- Writing the Literature Review: A Practical Guide by Sara Efrat Efron and Ruth Ravid

- Succeeding with Your Literature Review: A Handbook for Students by Paul Oliver

- Cochrane Library : For systematic reviews in healthcare and medicine

- PRISMA Guidelines : For conducting and reporting systematic reviews

- Covidence : For streamlining the systematic review process, including study screening and data extraction

- RevMan : For preparing and maintaining Cochrane systematic reviews

- Rayyan : For systematic review screening and collaboration

- GRADEpro : For assessing the quality of evidence in systematic reviews

- PROSPERO : For registering your systematic review protocol

- PubMed : For finding peer-reviewed biomedical and life sciences literature

- Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide by Mark Petticrew and Helen Roberts

- Introduction to Systematic Reviews by David Gough, Sandy Oliver and James Thomas

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions by Julian Higgins and Sally Green

- Doing a Systematic Review: A Student’s Guide by Angela Boland, M. Gemma Cherry and Rumona Dickson

How can editing services help improve a systematic review or a literature review?

Professional editing services enhance the quality of systematic and literature reviews by directly improving key aspects of the manuscript, such as clarity and coherence, accuracy and precision, structure and organisation and many others.

Clarity and coherence

Copyediting and line editing ensure the writing remains clear and easy to follow. Editors refine sentence structure, remove ambiguity and enhance readability so complex ideas flow logically from one point to the next. This clarity makes it easier for readers and reviewers to engage with the content.

Accuracy and precision

Proofreaders catch and correct minor errors like spelling, grammar and punctuation. This is especially important in systematic reviews, where precise language is crucial to present accurately data, methods and findings. Meanwhile, copyeditors ensure consistency in terminology and style to sharpen the overall accuracy.

Structure and organisation

Developmental editing helps authors organise their content logically. In literature reviews, editors ensure themes are well-defined and develop smoothly. For systematic reviews, they guide the arrangement of sections like methods, results and discussions to create a coherent and well-structured manuscript.

Adherence to guidelines

Editors ensure the review follows all necessary guidelines. Copyediting focuses on proper formatting, referencing and structure and aligns them with specific journal or institutional requirements. For systematic reviews, copyeditors check for adherence to frameworks like PRISMA to ensure compliance with reporting standards and citation styles like APA or MLA.

Consistency and tone

Line editors make sure the manuscript maintains a consistent tone and voice throughout. In literature reviews, they balance the author’s voice with academic standards. For systematic reviews, editors ensure the tone stays formal and objective and fits the review’s evidence-based nature.

Argument and evidence presentation

Developmental editors strengthen the manuscript by refining arguments and improving how authors present and synthesise evidence. In systematic reviews, editors ensure the data and evidence follow a clear logical progression and conclusions match the presented findings.

Conciseness

Line editing and copyediting remove unnecessary words, sentences and repetitive information. In systematic reviews, keeping the text concise ensures that readers focus on the critical findings and methodologies without getting distracted by redundancies.

Objectivity

Editors play a key role in keeping the review objective. Line editing helps authors maintain neutrality, particularly in systematic reviews where biased language can affect the interpretation of results. Editors keep the tone of the review balanced by removing subjective phrasing and aligning the tone with the systematic methodology.

Final polish

Proofreading provides the final touch. Proofreaders remove any remaining errors, ensure consistent formatting and double-check references. This work ensures the manuscript is ready for submission or publication.

Key takeaways

In conclusion, systematic review vs literature review highlights clear distinctions in methodology, scope and purpose. Systematic reviews follow a structured, rigorous approach to analyse evidence on a specific research question and they typically act as standalone publications for healthcare, policy or other data-driven fields. Literature reviews, by contrast, offer a more flexible, broader summary of research and often are a part of larger works like dissertations or journal articles. Both review types provide valuable insights, but systematic reviews aim for objectivity and completeness, while literature reviews focus on summarising existing knowledge with more subjectivity.

Contact me if you are an academic author looking for editing or indexing services. I am an experienced editor offering a free sample edit and an early bird discount .

I'm a freelance editor and indexer with a PhD in literary history. I work with non-fiction, academic and business texts.

Memberships

Incorporated in England and Wales. Company number: 10809565. Registered office: 124 City Road, London, England, EC1V 2NX

© MWEditing 2023

Literature Review Research

Literature review vs. systematic review.

- Literature Review Process

- Finding Literature Reviews

- Helpful Tips and Resources

- Citing Sources This link opens in a new window

Resources for Systematic Reviews

- NIH Systematic Review Protocols and Protocol Registries Systematic review services and information from the National Institutes of Health.

- Purdue University Systematic Reviews LibGuide Purdue University has created this helpful online research guide on systematic reviews. Most content is available publicly but please note that some links are accessible only to Purdue students.

It is common to confuse literature and systematic reviews because both are used to provide a summary of the existing literature or research on a specific topic. Despite this commonality, these two reviews vary significantly. The table below highlights the differences.

Kysh, Lynn (2013). Difference between a systematic review and a literature review. figshare. Poster. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.766364.v1

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Literature Review Process >>

- Last Updated: May 6, 2024 4:11 PM

- URL: https://tcsedsystem.libguides.com/literature_review

About Systematic Reviews

Understanding the Differences Between a Systematic Review vs Literature Review

Automate every stage of your literature review to produce evidence-based research faster and more accurately.

Let’s look at these differences in further detail.

Goal of the Review

The objective of a literature review is to provide context or background information about a topic of interest. Hence the methodology is less comprehensive and not exhaustive. The aim is to provide an overview of a subject as an introduction to a paper or report. This overview is obtained firstly through evaluation of existing research, theories, and evidence, and secondly through individual critical evaluation and discussion of this content.

A systematic review attempts to answer specific clinical questions (for example, the effectiveness of a drug in treating an illness). Answering such questions comes with a responsibility to be comprehensive and accurate. Failure to do so could have life-threatening consequences. The need to be precise then calls for a systematic approach. The aim of a systematic review is to establish authoritative findings from an account of existing evidence using objective, thorough, reliable, and reproducible research approaches, and frameworks.

Level of Planning Required

The methodology involved in a literature review is less complicated and requires a lower degree of planning. For a systematic review, the planning is extensive and requires defining robust pre-specified protocols. It first starts with formulating the research question and scope of the research. The PICO’s approach (population, intervention, comparison, and outcomes) is used in designing the research question. Planning also involves establishing strict eligibility criteria for inclusion and exclusion of the primary resources to be included in the study. Every stage of the systematic review methodology is pre-specified to the last detail, even before starting the review process. It is recommended to register the protocol of your systematic review to avoid duplication. Journal publishers now look for registration in order to ensure the reviews meet predefined criteria for conducting a systematic review [1].

Search Strategy for Sourcing Primary Resources

Learn more about distillersr.

(Article continues below)

Quality Assessment of the Collected Resources

A rigorous appraisal of collected resources for the quality and relevance of the data they provide is a crucial part of the systematic review methodology. A systematic review usually employs a dual independent review process, which involves two reviewers evaluating the collected resources based on pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The idea is to limit bias in selecting the primary studies. Such a strict review system is generally not a part of a literature review.

Presentation of Results

Most literature reviews present their findings in narrative or discussion form. These are textual summaries of the results used to critique or analyze a body of literature about a topic serving as an introduction. Due to this reason, literature reviews are sometimes also called narrative reviews. To know more about the differences between narrative reviews and systematic reviews , click here.

A systematic review requires a higher level of rigor, transparency, and often peer-review. The results of a systematic review can be interpreted as numeric effect estimates using statistical methods or as a textual summary of all the evidence collected. Meta-analysis is employed to provide the necessary statistical support to evidence outcomes. They are usually conducted to examine the evidence present on a condition and treatment. The aims of a meta-analysis are to determine whether an effect exists, whether the effect is positive or negative, and establish a conclusive estimate of the effect [2].

Using statistical methods in generating the review results increases confidence in the review. Results of a systematic review are then used by clinicians to prescribe treatment or for pharmacovigilance purposes. The results of the review can also be presented as a qualitative assessment when the end goal is issuing recommendations or guidelines.

Risk of Bias

Literature reviews are mostly used by authors to provide background information with the intended purpose of introducing their own research later. Since the search for included primary resources is also less exhaustive, it is more prone to bias.

One of the main objectives for conducting a systematic review is to reduce bias in the evidence outcome. Extensive planning, strict eligibility criteria for inclusion and exclusion, and a statistical approach for computing the result reduce the risk of bias.

Intervention studies consider risk of bias as the “likelihood of inaccuracy in the estimate of causal effect in that study.” In systematic reviews, assessing the risk of bias is critical in providing accurate assessments of overall intervention effect [3].

With numerous review methods available for analyzing, synthesizing, and presenting existing scientific evidence, it is important for researchers to understand the differences between the review methods. Choosing the right method for a review is crucial in achieving the objectives of the research.

[1] “Systematic Review Protocols and Protocol Registries | NIH Library,” www.nihlibrary.nih.gov . https://www.nihlibrary.nih.gov/services/systematic-review-service/systematic-review-protocols-and-protocol-registries

[2] A. B. Haidich, “Meta-analysis in medical research,” Hippokratia , vol. 14, no. Suppl 1, pp. 29–37, Dec. 2010, [Online]. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3049418/#:~:text=Meta%2Danalyses%20are%20conducted%20to

3 Reasons to Connect

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Sep 11, 2022 · Writing a literature review for a thesis, a research paper, or as a standalone assignment takes time. Much of your time will go into research, not to mention you have other assignments to complete. If you find writing in college or university overwhelming, get in touch with our literature review writers for hire at 25% discounts and enjoy the ...

Oct 28, 2024 · Literature Review: it is a product and a process. As a product , it is a carefully written examination, interpretation, evaluation, and synthesis of the published literature related to your topic. It focuses on what is known about your topic and what methodologies, models, theories, and concepts have been applied to it by others.

Systematic Review vs Literature Review. The difference between literature review and systematic review comes back to the initial research question. Whereas the systematic review is very specific and focused, the standard literature review is much more general. The components of a literature review, for example, are similar to any other research ...

Feb 26, 2021 · The literature review is one part of a research paper. In a research paper, you use the literature review as a foundation and as support for the new insight that you contribute. The focus of a literature review, however, is to summarize and analyze the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions.

A systematic review is a type of review article that tries to limit the occurrence of bias. Traditional, non-systematic reviews can be biased because they do not include all of the available papers on the review’s topic; only certain studies are discussed by the author. No formal process is used to decide which articles to include in the review.

Oct 28, 2023 · If you’re trying to decide whether a systematic review or literature review is the best approach for your project, consider the main distinctions: 1. Literature reviews offer a broad overview of the existing literature and identify research gaps, while systematic reviews focus on answering a specific research question. 2.

Dec 16, 2024 · Systematic vs. Literature Review; Systematic Review Literature Review; Definition: High-level overview of primary research on a focused question that identifies, selects, synthesizes, and appraises all high quality research evidence relevant to that question

Oct 23, 2024 · Systematic review vs literature reviews. When comparing a systematic review vs literature review, a systematic review is more structured, objective and time-consuming, and it focuses on a specific research question with a rigorous methodology, while a literature review is more flexible and narrative-driven and offers a broader overview of a topic.

May 6, 2024 · Literature Review: Systematic Review: Definition. Qualitatively summarizes evidence on a topic using informal or subjective methods to collect and interpret studies: High-level overview of primary research on a focused question that identifies, selects, synthesizes, and appraises all high quality research evidence to that question: Goals

Each type of review has a specific place in the scientific literature, with its own benefits and challenges. The kind of review to be conducted depends on the intended purpose of the research. Literature reviews usually answer broad and descriptive research questions.