What Is Culture?

- First Online: 20 October 2020

Cite this chapter

- Caprice Lantz-Deaton 3 &

- Irina Golubeva 4

1831 Accesses

This chapter explores the concept of culture. While you may think that you know what the word culture means, it is actually a highly complex and debated term. Getting to grips with culture, the different types of culture (e.g., objective and subjective) and how cultural variation has been studied at the macro level, will help you to better understand ‘culture’ as it relates to intercultural competence. This chapter will also help you to consider your own cultural identity which is key to developing intercultural competence.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Anderson, N. H. (1968). Likableness ratings of 555 personality-trait words. Journal of Social Psychology, 9 (3), 272–279.

Google Scholar

Apanews. (1992). Bush’s v-sign has different meaning for Australians with PM-Bush https://www.apnews.com/42939a95e2b694ec6262ff5949d910c9 . Accessed October 27, 2019.

Aronson, E., Wilson, T., Akert, R., & Sommers, S. (2018). Social psychology (9th ed.). London: Pearson.

Avruch, K. (1998). Culture and conflict resolution . Washington DC: United States: Institute of Peace Press.

Baltezarevic, R., Kwiatek, P., Blatezarevic, B., & Baltezarevic, V. (2019). The impact of virtual communities on cultural identity. Symposium, 6 (1), 7–22.

Article Google Scholar

Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality . Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

Chhokar, J. S., Brodbeck, F. C., & House, R. J. (2007). Introduction. In J. S. Chhokar, F. C. Brodbeck, & R. J. House (Eds.), Culture and leadership across the world: The GLOBE book of in-depth studies of 25 societies (pp. 1–15). Mahwah, New Jersey-London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chapter Google Scholar

CNBC. (2014). How photographs saved the Israel-Egypt peace talks. https://www.cnbc.com/2014/10/02/how-photographs-saved-the-israel-egypt-peace-talks.html . Accessed November 7, 2019.

Cortina, K.S., Arel, S., & Smith-Deaden, J.P. (2017). School belonging in different cultures: The effects of individualism and power distance. Frontiers in Education (1 Nov).

Dovidio, J.F., & Gaertner, S.L. (2010). Intergroup bias. In S.T.G. Fiske, D. T., & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley & Sons.

European Commission. (2018). Report on equality between men and women in the EU. (pp. 72). Luxembourg.

Gees, V. (1982). The self-concept. Annual Review of Sociology, 8, 1–33.

Gov.uk (n.d.). Paternity pay and leave. https://www.gov.uk/paternity-pay-leave . Accessed October 28, 2019.

Hall, E. T. (1959). The silent language . New York: Doubleday.

Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension . Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Hall, E. T. (1977). Beyond culture . New York: Anchor Books.

Hall, E. T. (1983). The dance of life: The other dimension of time . Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Hart, D., & Damon, W. (1986). Developmental trends in self-understanding. Social Cognition, 4 (4), 388–407.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind . London: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2 (1),

Hofstede, G., & Bond, M. (1988). The Confucius connection: From cultural roots to economic growth. Organizational Dynamics, 16 (4), 4–21.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind . London: McGraw-Hill.

Hofstede, G., & McCrae, R. R. (2004). Personality and culture revisited: Linking traits and dimensions of culture. Cross-Cultural Research, 38 (1), 52–88.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. J., Gupta, V., & Associates, G. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

Kane, C. M. (1998). Differences in family of origin perceptions among African American, Asian American, and Hispanic American college students. Journal of Black Studies, 29 (1), 93–105.

Karau, S.J., & Williams, K.D. (1993). Social loafing: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (65), 4.

Kelly, G. (2016). Paternity leave: How Britain compares to the rest of the world. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/men/fatherhood/paternity-leave-how-britain-compares-with-the-rest-of-the-world/ . Accessed October 21, 2019.

Kluckhohn, C., & Strodtbeck, K. (1961). Variations of value orientations . Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Knapp, M. L., Hall, J. A., & Horgan, T. G. (2014). Nonverbal communication in human interaction . Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Kroeber, A.L., & Kluckhohn, C. (1952). Culture: A critical review of concepts and definitions. Papers Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, 47 (1).

Matsumoto, D. (1996). Culture and Psychology . Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

McGaha, J. (2015). Popular culture & globalization: Teacher candidates’ attitudes & perceptions of cultural & ethnic stereotypes. Multicultural Education, 23 (1), 32–37.

Rieck, A. M. (2014). Ecploring the nature of power distance on general practitioner and community pharmacist relations in a chronic disease management context. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28 (5), 440–446.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Rogers, E.M., & Hart, W.B. (2002). Edward T. Hall and the history of intercultural communication: The United States and Japan. Keio Communication Review, 24 (3), 3026.

Rutter, M. (2006). Genes and behavior: Nature-nurture interplay explained . Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Schulzke, E. (2015). Poor American kids grow up without ‘airbags,’ Harvard professor says. Descret News National . http://national.deseretnews.com/article/3929/poor-american-kids-grow-up-without-airbags-harvard-professor-says.html .

Schwartz, S. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values. Journal of Social Issues, 50 (4), 19–45.

Schwartz, S. J., Montogomery, M. J., & Briones, E. (2006). The role of identity in acculturation among immigrant people: Theoretical propositions, empirical questions, and applied recommendations. Human Development, 49, 1–30.

Schwitzgebel, E. (2016). Belief. https://stanford.library.sydney.edu.au/entries/belief/ . Accessed October 28, 2019.

Sherif, M. (1936). The psychology of social norms . Oxford, England: Harper.

Spencer-Oatey, H., & Franklin, P. (2009). Intercultural interaction: A multidisciplinary approach to intercultural communication . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Book Google Scholar

Starbucks. (2019). Starbucks coffee international. https://www.starbucks.com/business/international-stores . Accessed October 27, 2019.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago Illinois: Nelson-Hall.

Thompson, T. L., & Kiang, L. (2010). The model minority stereotype: Adolescent experiences and links with adjustment. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 1 (2), 119–128.

Ting-Toomey, S. (1999). Communicating across cultures . New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Triandis, H. (1995). Individualism and collectivism . Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Triandis, H. C., & Gelfland, M. J. (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74 (1), 118–128.

Trompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (1997). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding cultural diversity in business . London: Nicholas Brealey.

Tung, R. (1995). International organizational behaviour : Luthans Virtual OB McGraw-Hill.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory . Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Williams, R. (1983). Culture & society: 1780–1950 (2nd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press.

Wood, J. (2009). Gender lives: Communication, gender, and culture (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Asheville, NC, USA

Caprice Lantz-Deaton

Department of Modern Languages, Linguistics, and Intercultural Communication, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Baltimore, MD, USA

Irina Golubeva

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Caprice Lantz-Deaton .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Lantz-Deaton, C., Golubeva, I. (2020). What Is Culture?. In: Intercultural Competence for College and University Students. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57446-8_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57446-8_2

Published : 20 October 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-57445-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-57446-8

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 08 August 2024

Country and culture, mental health in context

Nature Mental Health volume 2 , pages 877–878 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

327 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Much of psychiatry, psychology and mental health broadly has been dependent on the notion that people are predominantly similar or simply by neglecting diversity. Yet there are powerful influences related to one’s national or country identity, race and ethnicity, community and cultural heritage that speak to a far more complex and dynamic reality. Reflecting on these factors in the context of research is not only a challenge but a profound opportunity to spur future work and to improve care and treatment for individuals.

In the wake of US President Joe Biden dropping out of the 2024 presidential race, the internet has come alive with news stories, social media posts and humor generated by this monumental decision. But one meme has stood out, featuring the presumptive Democratic candidate, Vice-President Kamala Harris. She recounts one of her mother’s favorite turns of phrase to describe young people’s tendency to neglect the influence of previous generations, “You think you just fell out of a coconut tree? You exist in the context of all in which you live and what came before you.”

Although Harris was referring to family and economic opportunities, it is an apropos sentiment to apply to health, as well as mental health. Social and cultural forces have long been hypothesized to shape concepts of self, expressions of self and self-regulation. Although ‘country’ identification can be conflated with a predominant culture artificially circumscribed by borders, it confers at least some level of connectedness to a certain set of customs, beliefs and norms. Not surprisingly, the idea that one’s country or cultural contact can shape an individual has been part of scholarly discourse for centuries among theologians, philosophers and anthropologists. At a fundamental level, understanding the human condition and mental health requires the discussion of culture.

The nuanced ways in which a country or culture may interact with an individual’s biology alongside institutional and structural factors warrant prominence in theoretical models of mental health and risk of developing mental health disorders. Contemporary frameworks that incorporate social determinants of mental health include cultural components and can highlight the potential additive effects of culture in shaping an individual’s experience. The extent to which someone is likely to engage in help-seeking behavior for a mental health condition can be predicated on cultural or community norms. For example, as a group, Asian Americans are less likely to utilize mental health services. The experience of stigma around mental health issues is often magnified in eastern cultures, where an individual’s behaviors and health can reflect on their familial lineage. By contrast, there are culturally salient factors, such as one’s proficiency in English language or feminine gender, that can serve to lessen stigma and promote contact with mental health providers.

Although there can be major barriers to accessing mental health care prompted by cultural influences, access itself is subject to community and country-level constraints, including funding for compensating providers, training for specialized care for certain groups, and coverage for medication and treatment. Culturally competent or responsive care, which is designed to involve stakeholders and representation from community members, integrates components of mental health care that may be outside of more medicalized treatment and can include religion, spirituality or the arts, and relies on active dismantling of impediments to receiving treatment, such as increasing access to telemedicine or group therapy. Improving the quality and accessibility of mental health care also incorporates a broad view of culture and cultural needs in the sense that individual mental health is woven together with intersectional identity and community — for example, being a woman, identifying as LGBT+, or immigration status. The complexity of identity and culture make one-size-fits-all mental health approaches obsolete and inadequate.

The August 2024 issue of Nature Mental Health includes several pieces that highlight some of the ways in which country setting or culture can influence mental health. In their Perspective , Toffol et al. discuss recent country-level developments in the programs for one of the most vulnerable groups, children of parents with a mental illness (COPMI). The authors discuss some of the key lessons learned from intervention programs aimed at COPMI, including European projects in Germany, Denmark and Austria. The authors outline specific barriers and problems, and propose facilitators and recommendations to identify affected children as early as possible, and provide culturally responsive and interconnected mental health care for people who have often been underserved.

Australia’s Emerging Minds program is another national strategy that trains professionals to identify, assess and support COPMI with a cultural lens. In addition to specific programming for children, the project oversees training and resources for practitioners, families and researchers that specifically focus on children’s mental health. People of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heritage in Australia have long experienced racial discrimination associated with negative physical and mental health consequences. Emerging Minds incorporates training pathways that encompass unique cultural experiences, drawing on spiritual and cultural concepts and tenets, the interaction with social, legal and political frameworks in Australia, and considers the intergenerational trauma that affects families and communities.

In an Article , Agarwal et al. report an association between stock market fluctuations and mental and physical health effects, providing another vantage point to appreciate the potential influence of culture and country context. Tracking daily market returns alongside visits to emergency rooms at three of the largest hospitals in Beijing over a four-year period (2009–2012), stock market declines were linked to significant increases in emergency room visits for stress-related issues, including cardiovascular disease, mental health concerns and alcohol abuse. Notably, older adults and men were the groups most affected by these fluctuations.

Although these data are considered ‘historical’ (which can probably apply to most data collected before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic), they provide unique insights into the Chinese cultural context and the potential mental health effects of economic volatility in a developing country. Much of the previous work in this area was conducted in high-income countries, where a greater proportion of individuals sampled were seasoned investors. By contrast, investors in the time frame assessed in Beijing were more likely to be novices who were interacting with a less sophisticated and less stable market, underscoring the immediacy of stress-related responses. These findings suggest that economic shock and volatility can be considered substantial public health concerns, even more so for resource-limited individuals in developing countries

Health systems data from different regions or countries can also reflect ‘natural experiments’, such as emergency room visits prompted by disasters or crises. With so much scrutiny in recent years on overdose deaths, rising stimulant prescriptions and mental health diagnoses, hospital admissions data can often provide insights into current versus previous timepoints in an epidemiological landscape. In their Article , Xing et al. look at hospital admissions in the USA over more than a decade, using weighted National Inpatient Survey data from 2008 to 2020. The authors report a 10.5-fold increase in mental health disorder-related hospital admissions with concurrent methamphetamine use. Hospital admissions related to mental health disorders increased only modestly during this period (1.4-fold), but these data point to the enormous burden on US hospital systems presented by the increased methamphetamine use — a phenomenon that differentially affects North America.

These are just a few examples of research where culture or country setting may enhance the interpretation of the results or provide additional background, and it is vital that more work is done specifically in cultural mental health research, and also to better understand the specific structures and institutions within country and regional mental health care systems. Nature Mental Health takes a keen interest in work that describes and documents mental health care systems internationally. By presenting and discussing for whom and how mental health care is organized and delivered, and by disseminating shortcomings and achievements, we move closer to better treatment, improved access, training and outcomes. The contexts and what came before us do not have to limit mental health care, but instead can inform and determine where we go next.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Country and culture, mental health in context. Nat. Mental Health 2 , 877–878 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00305-2

Download citation

Published : 08 August 2024

Issue Date : August 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s44220-024-00305-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Futurity is your source of research news from leading universities.

- About Futurity

- Universities

- Environment

Society and Culture

Stay connected. subscribe to our newsletter..

Add your information below to receive daily updates.

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Feature Article

Research Culture: Setting the right tone

- Elizabeth Adams

- University of Glasgow, United Kingdom ;

- Open access

- Copyright information

- Comment Open annotations (there are currently 0 annotations on this page).

- 15,447 views

- 844 downloads

- 9 citations

Share this article

Cite this article.

- Tanita Casci

- Copy to clipboard

- Download BibTeX

- Download .RIS

Article and author information

Improving the research culture of an institution may lead to a fairer, more rewarding and successful environment, but how do you start making changes?

The University of Glasgow was founded more than 550 years ago and currently welcomes over 5000 researchers working in a wide range of subjects across the sciences and the humanities. Feedback suggests that our research culture is already good, but we think that it could be even better. As the Head of Research Policy (TC) and the Researcher Development Manager (EA), we have spent the past few years working to update research culture at Glasgow. Based on our experiences, our advice to anyone trying to change the culture of their institution is to be practical, consistent, and to aim for progress, not perfection. Start even if you cannot see the end. The project is big, slow, fragmented: and yes, it is a fantasy to imagine that a university has, or should have, a single culture.

The recent research culture survey by the Wellcome Trust has highlighted what many of us would not dispute: that the pursuit of a narrow definition of research excellence, and of excellence at any cost, has limited the research endeavour and had an adverse impact on the wellbeing of researchers as well as the quality and reliability of the research they undertake. It is not too late to fix this issue, but solutions will emerge only once research organisations, funders, publishers and government coordinate their efforts to identify practical actions that can be implemented consistently across the research community.

Meanwhile, the complexity of the problem should in no way stop us from implementing changes within our own institutions. At Glasgow, we focus on fostering a positive research culture . To do so, we develop policies, guidance, communications, training and related initiatives that support the success of researchers at all stages of their career.

With the support of our senior management, we have introduced several initiatives that we hope will make our institution an inspiring place in which to develop a career — whether it is academic or administrative, operational or technical, or indeed something different altogether. Some of these initiatives are summarised in this post ; in this article we will also share the lessons we learned along the way that might be useful to others.

Start from what you know

Research culture is a hazy concept, which includes the way we evaluate, support and reward quality in research, how we recognise varied contributions to a research activity, and the way we support different career paths.

Of all the things you could do to improve research culture, start from the priorities that you think matter most to your organisation; those that reflect its values, fit with what your community really cares about, or align to the activities that are already in progress. If you can, line up your agenda to an external driver. In our situation, two prominent drivers are the UK Research Excellence Framework (an exercise that assesses the quality of research, including the research environment, at all UK universities), and the Athena Swan awards (which evaluate gender equality at institutional and local levels). Our research culture initiatives also work alongside everyday drivers from research funders and other bodies, such as concordats on research integrity , career development and open research data .

Even better, align your initiative to more than one agenda. For example, we are supporting transparency, fairness, accountability (and therefore quality, career development, and collaboration) by requesting that research articles deposited in our institutional repository follow the CRediT taxonomy , whereby the roles and responsibilities of each authors are laid down explicitly.

Once you know what you mean by culture, write it down and let people know. This will aid communication, keep everyone focussed, and avoid the misunderstanding that culture is a solution to all our problems (“The car parking is a nightmare. I thought we had a culture agenda!”).

At Glasgow we define a positive research culture as one in which colleagues (i) are valued for their contributions to a research activity, (ii) support each other to succeed, and (iii) are supported to produce research that meets the highest standards of academic rigour. We have then aligned our activities to meet these aims, for example by redesigning our promotion criteria to include collegiality, and creating a new career track for research scientists (see Box 1 ).

Changing promotion criteria and career trajectories to foster a different research culture

At the University of Glasgow, academic promotion criteria are based on a 'preponderance approach': candidates need only meet the necessary criteria in four of the seven dimensions used to assess staff for promotion (academic outputs; grant capture; supervision; esteem; learning and teaching practice; impact; leadership, management and engagement). For the 2019–2020 promotions round, the University has also introduced a requirement to evidence collegiality as well as excellence in each of the four qualifying dimensions. The criteria recognise not only the achievement of the individual but also how that individual has supported the careers of others.

From 2019–2020 onwards, promotion criteria for the academic track also explicitly state that one of the four qualifying criteria should be either academic outputs or impact. By ‘impact’ we mean the evidenced benefits to society that have resulted from the research – these could be economic, societal, cultural, or related to health and policy. The new criteria therefore formally acknowledge that societal impact holds as much value to the institution as outputs, and that generating and evidencing impact takes time. It also ensures that staff does not feel under pressure to ‘do everything’. We will be monitoring the effect of these changes in mid 2020.

In addition, Glasgow has recently introduced a career pathway for research scientists: this track recognises and rewards the contributions made by researchers who have specialist knowledge and skills, such as bioinformaticians. The contributions and intellectual leadership provided by these roles are often not reflected in the traditional promotion criteria, which depend on lead or senior authorships. Research scientists can instead progress in their careers by demonstrating specialist work stream, as well as team contributions.

Practice, not policy

Success will not come from issuing policies, but by making practical changes that signal “the way we do things around here”. Even if university policies are read, they will be forgotten unless the principles are embedded in standard practice. And if we are not serious about our practices, then we are not credible about our intentions.

Over 1500 organisations have signed DORA and have committed not to use unreliable proxies such as journal impact factors in research evaluation. Yet, even purging references to journal impact factors from all paperwork is no guarantee that these or other metrics will not be used. If we are serious about fair evaluation mechanisms, then we need to provide evaluation panels with meaningful information. At Glasgow, we ask applicants to describe in 100 words the importance of their output, and their contribution to it. Many organisations have switched to the use of narrative formats, for instance the Royal Society , or the Dutch research council ( NWO ). To show that we value all dimensions of research, we also ask for a commitment to open research and give parity of credit to academic outputs (such as papers) and the societal impact they create (see Box 1 ).

To ensure that changes are felt on the ground, we are embedding these priorities in annual appraisals, promotion and recruitment, so that the same expectations are encountered in every relevant setting. We have also included the importance of responsible metrics in recruitment training, and will be working with our colleagues in human resources to ensure that local conversations with hiring managers are consistent with our metrics policy (see Box 2 ).

Responsible metrics

The policy on the responsible use of metrics means ensuring that the mechanisms we use to evaluate research quality are appropriate and fairly applied. For example, we need to make sure that quantitative indicators are suitably benchmarked and normalised by subject, and that they are used along qualitative ones. This is to avoid the over-reliance on single-point metrics (such as research funding) and over-use of unreliable proxies for quality (such as journal impact factors).

The policy describes our approach to evaluating the quality of our outputs, our supervision and our grant capture. The proof, however, is in the way the policy is implemented in practice. For example, applicants to our strategic recruitment schemes are requested to select their four best outputs, describe the significance of each output to the field (without relying on impact factors), and narrate their contribution to the work. Applicants are also asked to describe their commitment to open research. This approach allows the recruitment panel to obtain a more rounded impression of the candidate and, we hope, reduces the use of unhelpful proxies such as length of publication list or journal impact factors.

Start, even if you cannot see the finish line

Once you have decided on the general direction, start by doing something without worrying about scoping the project from start to finish.

At Glasgow we started by doing a 360-degree review of our provision for research integrity: this was not just about the training but also about raising the visibility of this agenda in the community. We did not call it ‘culture’ then, but we realised that progress would come from communicating the dimensions of good practice (e.g. open research) rather than by sanctioning breaches of conduct. That exercise gave us experience of getting support from senior management, managing a cross-institutional working group, and getting buy-in from the academic body through the establishment of a network of 29 integrity advisers . These individuals champion this agenda to researchers, contribute to training and policy and also participate in research misconduct panels.

From integrity, we moved to open research, and from there, to careers. It started with compliance, and progressed towards culture. Do not wait for the rules to come to you. Make your own. Have confidence that once projects are initiated, they will suggest future courses of action.

Shout about it

If you want to be noticed, it helps to over-communicate. If your project serves more than one agenda, then your colleagues in, say, human resources, the library, the research office, and the equality, diversity, and inclusion team will already be helping you to amplify the message. We have set up a Culture and Careers group that brings together a range of relevant professional groups and colleagues. Focusing on our culture activities and the training that we can provide to staff and students helps us to share knowledge and to highlight where different agendas can reinforce each other.

Make the framework easy to understand: at Glasgow we talk about supporting what we value (e.g. CRediT), recognising what we value (e.g. our promotion criteria), and celebrating those values, for instance with our recently launched research culture awards . These highlight outstanding activities that promote collegial behaviours and contribute to a positive research culture. In 2019, over 30 applications were received from across the institution, reflecting a variety of career stages, coming from academic, technical and professional services roles, and ranging from groups of researchers to individual staff. The awards have changed the conversation as to what culture actually is.

But equally do not fret if colleagues do not know how your various activities fit together under a ‘culture’ agenda. It is far more important that researchers embrace the activities themselves (see “Practice, not policy” above).

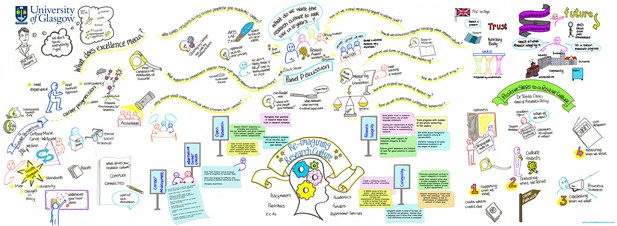

Communication takes legwork, so use any channel you have. Present at committees, consult with different disciplines and career stages. Speak to the willing. Welcome the challenge. Bring together different voices in a discussion forum. For example, we recently organised a research culture event involving action-oriented conversations with academics, administrators, funders, societies, and publishers; this helped to build our evidence base, share perspectives and move forward institutional thinking in relation to key areas of culture (see the illustration for a summary of the discussion).

Map of the ideas discussed at the Re-imagining research culture workshop organised at the University of Glasgow in September 2019.

Jacquie Forbes at drawntolearn.co.uk (CC BY 4.0)

A research culture survey allowed us to assess how we were doing. It gathered examples of good practice (for example, that the community appreciated reading groups and the opportunity for internal peer review) and it highlighted the aspects of research our staff were comfortable with (open access, for instance). It also pointed us towards what people wanted to know more about, such as how to increase the visibility of their research. Together, the event and survey have informed our next actions (you can access the question set here ) and our action plan for the next five years.

No such thing as a single culture

If you work in a research organisation, you are probably relaxed about the fact that different parts of the institution have their own priorities, as befits the disciplinary community.

Institution-wide projects should be designed to address the broad ambitions of the university: for example, all areas of the university can participate in the research culture awards or meet the requirement for collegiality in our promotion criteria.

Each discipline can then be invited to implement the culture programme that suits them. Getting this right requires a bit of flexibility, some confidence that things will not unravel, but also clear leadership. Some institutional glue can be provided by sharing case studies between areas, which is helped by collecting feedback on how policies and guidance are being implemented at the university level. For example, our new guidance on embedding equality, diversity and inclusion in conferences and events contains a weblink to a feedback survey. We hope that this will help us to pinpoint where colleagues are struggling to implement best practice, perhaps due to other organisational challenges such as funding, lack of clear guidance or procurement.

What’s next?

We have published an action plan for our 2020 – 2025 university strategy , which covers career development, research evaluation, collegiality, open research and research integrity. The starting point will be to focus on supporting career development, on helping researchers to enhance their visibility, and on developing an informed and committed leadership across the university.

We have also published an institutional statement to highlight the road travelled and our future plans. All the while, we are drawing inspiration from others: the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society, and the progressive policies introduced by publishers such as PLoS, eLife, Wiley, and F1000. We are excited by the launch of initiatives that will inform better decision-making in the culture space, and online groups for sharing ideas. We want to be a part of organisations, such as the UK Reproducibility Network , that identify priorities and work together in implementing them.

We are also casting our eyes towards broader aspects of culture: how do we define and encourage research creativity, how do we make more time, and how might we extend the scope of our actions beyond research staff to all those that contribute to research?

Culture does not happen at the expense of excellence; an updated culture is what will allow even more of us to excel.

Author details

Tanita Casci (@tanitacasci) is the Head of Research Policy at the University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

For correspondence

Competing interests.

Elizabeth Adams (@researchdreams) is the Researcher Development Manager at the University of Glasgow, Glasgow, United Kingdom

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the extended network of academics, technicians, students and professional services staff who over a long time have variously driven, supported, and constructively challenged what we are doing.

Publication history

- Received: January 29, 2020

- Accepted: January 29, 2020

- Version of Record published : February 10, 2020

© 2020, Casci and Adams

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use and redistribution provided that the original author and source are credited.

Views, downloads and citations are aggregated across all versions of this paper published by eLife.

Download links

Downloads (link to download the article as pdf).

- Article PDF

Open citations (links to open the citations from this article in various online reference manager services)

Cite this article (links to download the citations from this article in formats compatible with various reference manager tools), categories and tags.

- research culture

- academic careers

- academic promotion

- responsible metrics

- University of Glasgow

- Part of Collection

Research Culture: A Selection of Articles

Further reading.

Research culture needs to be improved for the benefit of science and scientists.

Be the first to read new articles from eLife

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Administration for Children & Families

- Upcoming Events

Safety Practices

- Open an Email-sharing interface

- Open to Share on Facebook

- Open to Share on Twitter

- Open to Share on Pinterest

- Open to Share on LinkedIn

Prefill your email content below, and then select your email client to send the message.

Recipient e-mail address:

Send your message using:

Building a Culture of Safety Campaign

The Office of Head Start’s (OHS) top priority is to create safe spaces that families and communities can trust. Every Head Start staff member, leader, and family plays an important role in safeguarding children and preventing safety concerns. We are launching this campaign to provide resources and in-depth support to the Head Start community.

Learn more about the campaign and why it’s so important in this short video from Director Khari M. Garvin.

Building a Culture of Safety

Director Khari Garvin: Hello, I'm Khari Garvin, the Director of the Office of Head Start. Ensuring Head Start programs are safe places for children that families and communities can trust is one of our top priorities. We know that children need physical and emotional safety in order to develop, learn, heal, and thrive. We have heard and witnessed how challenges in recent years, workforce shortages, staff turnover, mental health needs, and more can affect the safety of children and staff.

We are also witnessing a resounding commitment from Head Start programs to remain steadfast in creating environments and relationships where children can thrive. I'm excited to announce the Building a Culture of Safety series to support this Head Start commitment. From August through November, we'll be providing resources and webinars to share a range of strategies in every program area, and then engaging in discussion with you during special office hours we will make available to support child health and safety across the Head Start ecosystem.

Make sure you are subscribed to our emails to ensure you get the notifications promoting this series. Do you know what we mean by building a culture of safety? Head Start programs are spaces where every child is valued and we know that every single person, Head Start leaders, staff members, and families, plays an important role in safeguarding children.

A culture of safety isn't a one and done training or a checklist. It requires a comprehensive, ongoing, and preventative commitment. There are four core messages about the culture of safety approach. You will learn more about these throughout the series, but I will share them now to anchor us. First, is that Head Start leaders support children’s safety and well - being by creating safe program environments, for example, by mapping and reducing potential risks and hazards or creating wellness spaces for staff.

Now, the second core message about the culture of safety approach is that positive guidance from caregivers supports children's social and emotional development and promotes their engagement in the learning environment. Third, Head Start leaders cultivate an organizational culture that sets an expectation for child safeguarding and that builds trust, accountability, empathy, and equity for staff and families.

Leaders establish how we do things in the program with policies and procedures and by putting supports and systems in place to help everyone uphold those expectations. And by the way, did you know that Head Start and Early Head Start grant recipients that encounter program improvement needs related to health and safety, which cannot be covered by your regular budget, can submit a supplemental one-time funding application anytime throughout the year as needs emerge?

Those things in your program that address health and safety like repairs or upgrades to facilities or playgrounds or maybe adding temporary staff positions to achieve lower ratios in classrooms that need extra support. There is a lot of flexibility for these supplemental funds, although they are limited and available on a one - time basis.

I invite you to reach out to your regional office to learn more about the application process. Finally, everyone who works or volunteers in Head Start programs adheres to the Head Start Standards of Conduct, which are the basic professional expectations for working in a Head Start program. This Building a Culture of Safety series will offer strategies and create space for discussions to put these messages into action and develop a culture of safety in every Head Start program.

You can find out more about this series on the ECLKC website. Thank you for your commitment to making sure Head Start programs are safe. We couldn't do it without you. So long. For Building a Culture of Safety campaign information, visit https://qrco.de/bfEsZn to sign up for Office of Head Start email updates. Visit https://qrco.de/bfEsfn .

Produced by the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Approaches to Preventing and Addressing Child Health and Safety Incidents

Join us Aug. 28, 2024 at 2 p.m. ET , for a special webinar , 4 Steps to Healthy and Safe Learning Environments . It focuses on four strategies that align with OHS core messages on child health and safety.

The next day, Aug. 29 at 2 p.m. ET , bring your child health and safety incident questions to a follow-up live office hour . Experts from the National Center on Health, Behavioral Health, and Safety will be on hand to help you promote positive learning experiences for Head Start children and prevent incidents that can jeopardize their well-being. This event is offered with simultaneous interpretation in Spanish.

Register for Webinar Register for Office Hour

The following resources provide additional background for this event:

- Discipline and the Influence of Our Upbringing

- Keep Children Safe Using Active Supervision

Preventing and Addressing Child Incidents Through an Education Lens

Join us Sept. 20, 2024, from 3–4:30 p.m. ET , for a special webinar , 10 Tips for Creating Supportive Environments That Can Prevent Behaviors that Challenge Us . This Teacher Time episode focuses on useful tips for setting up the physical environment, transitions, schedules, routines, and more.

Following the webinar, stay on to participate in a live office hour session. Experts from the National Center on Early, Childhood, Development, Teaching, and Learning will be on hand to answer your questions about addressing child incidents through an education lens.

Register for Webinar and Office Hour

Promoting Child Safety Through Staff and Family Partnerships

Save the date, Thursday, Oct. 10, 3–4:30 p.m. ET , for a webinar and office hour discussion with the National Center on Parent, Family, and Community Engagement! Visit this page and be on the lookout for an email invitation as the date approaches.

Parents and families observe, guide, and participate in the everyday learning of their children at home, school, and in their communities in ways that promote children's safety, health, and development. Join this session to explore partnerships with parents as the lifelong educators and advocates for their children. We're sharing strategies for promoting child safety while exploring restorative practices that build and strengthen community, resolve conflict, facilitate individual and community healing, and prevent harm.

Research to Practice: Preventing Child Incidents Through Effective Systems

Save the date, Thursday, Nov. 14, 3–4:30 p.m. ET , for a webinar and office hour discussion with the National Center on Program Management and Fiscal Operations! Visit this page and be on the lookout for an email invitation as the date approaches.

This event explores how enhanced systems thinking and multi-dimensional perspectives can address a critical issue in Head Start programs: preventing and appropriately responding to child incidents. We're sharing tools, recommendations, and strategies to support Head Start leaders and staff in their ongoing efforts to keep children safe. Join to learn how to apply this information for optimal impact on children and their families.

- Using Motivation-based Interview Techniques

- Gallup's 5 Drivers of Organizational Culture

- Employing Values-based Recruitment in Hiring Practices

Resource Type: Article

National Centers: Office of Head Start

Last Updated: August 8, 2024

- Privacy Policy

- Freedom of Information Act

- Accessibility

- Disclaimers

- Vulnerability Disclosure Policy

- Viewers & Players

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

An Artist Faces Climate Disaster With Hard Data and Ancient Wisdom

Research meets poetry in Imani Jacqueline Brown’s exploration of oil extraction and its consequences for her native New Orleans — and for the planet.

By Siddhartha Mitter

Every Mardi Gras in New Orleans, the members of the North Side Skull and Bone Gang emerge onto the streets of the Tremé neighborhood in a dawn ritual that dates back more than 200 years. Clad in black-and-white skeleton suits and ornamented papier-mâché masks, they wake the city to the sound of drums and bells summoning the ancestors.

Their ritual carries deep significance, even lessons for the whole planet, said the artist and activist Imani Jacqueline Brown, who filmed the procession this year. “They’re breaching the divide between the world of the spirits and the world of the living,” she said. “They are singing to us that we’ve got to live today because tomorrow we might die.”

Brown, 36, grew up in New Orleans; she now lives in London, a member of the research and visual investigations group Forensic Architecture . An exhibition at Storefront for Art and Architecture in Manhattan through Aug. 31 combines her research chops with the poetry and spirituality that she sees in the grass-roots culture in her hometown.

The show, titled “Gulf,” is written with a strike-through and pronounced “Strike Gulf.” Its central focus is the impact of the oil and gas industry on South Louisiana. But the more sources Brown mines — including core samples of deep-sea drilling by geologists in the Gulf of Mexico and archives of oil boycott campaigns in the 1970s and 1980s, along with her own footage from New Orleans — the broader the scope of her project becomes. It reaches back into geological time while linking to the climate emergency today.

The resulting works bring some welcome lyricism to the field of “research art.” The exhibition includes a video installation in which the Skull and Bone Gang procession, bathed in bluish light, is overlaid on footage she made at the city’s aquarium, where sharks and rays float around a model of an offshore rig in a display about the Gulf of Mexico that is sponsored by oil corporations.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

How one pop band is trying to turn concertgoers into climate activists

Chloe Veltman

AJR tests climate activism at concerts

AJR fans at Denver's Ball Arena perform the wave on June 20, 2024. Chloe Veltman/NPR hide caption

At Ball Arena in Denver, thousands of fans of the multi-platinum-selling indie pop group AJR do the wave. The vast, coordinated ripple as the concertgoers throw their arms up instantly unites the room.

It's this type of mass, coordinated energy that AJR bassist and climate activist Adam Met wants to harness.

"Can we actually capture that power in the concert space and make use of it to get people to do something more?" said Met, who also runs the climate change research and advocacy non-profit Planet Reimagined .

Ryan Met, left, Jack Met, center, and Adam Met, right, of AJR at the 2019 Lollapalooza Festival in Chicago. Amy Harris/Invision/AP hide caption

AJR has been filling arenas across the country this summer on its Maybe Man tour with quirky-existential hits like "Bang!" "Burn the House Down" and "World's Smallest Violin."

Along the way, the band has also been collaborating with local nonprofits in each city to inspire concertgoers to take local, policy-based action to help reduce the impacts of human-caused climate change — right there in the arena.

Getting fans to do something more

According to data shared by Planet Reimagined and verified by its local nonprofit partners, concertgoers at AJR's two Salt Lake City shows sent 625 letters and 77 handwritten postcards to Utah legislators calling on them to decrease the amount of water being diverted from the Great Salt Lake.

This trio hopes 'Won't Give Up' will become an anthem for the climate movement

"In Phoenix, they sent more than 1,000 letters to the city council calling on them to recognize extreme heat as a climate emergency," Met said. "In Chicago, 200 fans sent letters to Illinois legislators urging them to pass the Illinois clean jobs platform, which supports investments in building transportation and the grid."

Those seem like tiny numbers. But they make an impact.

"So if 30, 40 or 50 people are in a live setting and they're being encouraged to support a particular nonprofit’s agenda, and they all send emails at the same time, that is definitely going to get the attention of lawmakers because that’s unusual," said Bradford Fitch, president and CEO of the non-partisan Congressional Management Foundation, which has done research on outreach to lawmakers. "That doesn’t happen very frequently."

Artists for climate activism

A growing number of artists are working to educate ticket-buyers at concerts about human-driven climate change as part of a broader environmental movement in the music industry.

"We're seeing more and more artists and venues and festival teams increasing their ambitions around sustainability overall," said Lucy August-Perna, global head of sustainability for music events promoter and venue operator Live Nation.

Artists like Billie Eilish have discussed the issue on stage.

“Most of this show is being powered by solar right now," Eilish said at last year’s Lollapalooza Festival in Chicago. "We really, really need to do a better job of protecting this [expletive] planet."

Many other performers, like Dave Matthews Band, The 1975 and My Morning Jacket, are also inviting activist groups to share information at concert venues.

"We have tables where fans can learn about local climate organizations and basically just connect about climate and sustainability," said Maggie Baird, who oversees Eilish's climate and sustainability efforts. (She's also the rock star's mom.) "I think it's really important that artists use their platforms. They have a unique gift, and they also have a unique responsibility."

"Most of our partner tours have fan actions and things that they can do on site," said Lara Seaver, director of touring and projects at Reverb, which works with touring artists such as Eilish and AJR on implementing their environmental efforts.

Seaver said what sets AJR's engagement work apart to a degree is its consistency and depth. "In every single market, we have something very local and meaningful and impactful happening," she said.

Assessing the impact

According to Planet Reimagined, around 12,000 audience members participated in climate-related civic actions during AJR's tour, such as signing petitions, sending letters, leaving voicemails, registering to vote, making donations and volunteering. An additional 10,500 scanned QR codes and signed up for emails to learn more about an issue.

AJR’s Met said he felt confident they would be responsive: Ticket buyers for concerts and festivals featuring artists like Taylor Swift, Beyonce, Dave Matthews Band and many more were polled in the recent Planet Reimagined Amplify: How To Build A Fan Based Climate Movement study , undertaken in collaboration with Live Nation. The majority of respondents said they’d be open to not just learning about climate change, but also would be open to take climate-related actions at these events.

Met said the findings also highlight what artists should do to be effective at each stop on a tour, such as being relevant to the local community. "If it’s affecting them and their community personally, they’re so much more likely to take action," Met said.

Met said the research also shows artists need to model those actions themselves. "Fans have this deep connection to artists," Met said. "So there is so much more impact on fans if the artist says, 'Will you join me in doing this?' As opposed to, 'Will you do this?'"

Putting research into practice

Chelsea Alexander and Bobbie Mooney of 350 Colorado were on site at an AJR concert in Denver to engage fans in supporting their phase-out fracking campaign Chloe Veltman/NPR hide caption

In Denver, fans were able to use their phones to scan a QR code displayed on screen to support a local campaign aimed at getting an initiative on the 2026 Colorado state ballot to phase out new permits for fracking by 2030. A contentious issue in Colorado, the process is used to extract oil and gas. It generates wastewater and emits toxic pollutants and methane, which is a major source of planet-warming pollution. But it’s big business.

Meanwhile, out on the concourse, representatives from 350 Colorado , the local climate change nonprofit that’s running the campaign, chatted up fans.

350 Colorado's Chelsea Alexander told AJR fan Robin Roston that the QR code, "takes you to a form that takes about 20 seconds to complete."

AJR concertgoers Robin Roston and Ben Roston Chloe Veltman/NPR hide caption

"I think it's a good way to get boots on the ground, chatting with real people who are here to enjoy music, and connecting that with helping the environment," Roston said.

Small steps, big potential

According to 350 Colorado, 179 people took action over the course of AJR's two performances in support of the phase-out fracking campaign. At least 125,000 physical signatures will be needed to get the initiative on the ballot in 2026.

But 350 Colorado representative Bobbie Mooney said every bit helps.

"We often think in terms of a ladder of engagement, where we can invite someone to take a small action and give them a sense of empowerment that they're a part of the solution," Mooney said. "And then we can invite them to take another, maybe greater action. They can join a committee, they can become a part of advocating for a particular bill in our legislature."

A fan died of heat at a Taylor Swift concert. It's a rising risk with climate change

Because of the collective energy they create, big, live gatherings such as concerts and sporting events provide a particularly powerful setting to get people on that ladder.

"The fact that everyone around us is doing something makes us dramatically more likely to do it ourselves," said Cindy McPherson Frantz , a professor of psychology and environmental studies at Oberlin College.

But Frantz said it’s not easy for fans to sustain enthusiasm for such things after coming down off that big event high.

"You could get all excited about calling your senator or voting at the rock concert," she said. "And then you go home, a week goes by or a month goes by, and you forgot all about it and you're busy and whatever. And then it just completely evaporates."

Frantz said simply getting fans to talk about climate change at a concert is a win, though. "The power of bringing people together and giving them the sense of, 'I am not alone, I'm not the only person scared about this, I'm not the only person working on this problem,' is a huge antidote to the hopelessness and the helplessness that comes from being isolated."

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Embracing Gen AI at Work

- H. James Wilson

- Paul R. Daugherty

The skills you need to succeed in the era of large language models

Today artificial intelligence can be harnessed by nearly anyone, using commands in everyday language instead of code. Soon it will transform more than 40% of all work activity, according to the authors’ research. In this new era of collaboration between humans and machines, the ability to leverage AI effectively will be critical to your professional success.

This article describes the three kinds of “fusion skills” you need to get the best results from gen AI. Intelligent interrogation involves instructing large language models to perform in ways that generate better outcomes—by, say, breaking processes down into steps or visualizing multiple potential paths to a solution. Judgment integration is about incorporating expert and ethical human discernment to make AI’s output more trustworthy, reliable, and accurate. It entails augmenting a model’s training sources with authoritative knowledge bases when necessary, keeping biases out of prompts, ensuring the privacy of any data used by the models, and scrutinizing suspect output. With reciprocal apprenticing, you tailor gen AI to your company’s specific business context by including rich organizational data and know-how into the commands you give it. As you become better at doing that, you yourself learn how to train the AI to tackle more-sophisticated challenges.

The AI revolution is already here. Learning these three skills will prepare you to thrive in it.

Generative artificial intelligence is expected to radically transform all kinds of jobs over the next few years. No longer the exclusive purview of technologists, AI can now be put to work by nearly anyone, using commands in everyday language instead of code. According to our research, most business functions and more than 40% of all U.S. work activity can be augmented, automated, or reinvented with gen AI. The changes are expected to have the largest impact on the legal, banking, insurance, and capital-market sectors—followed by retail, travel, health, and energy.

- H. James Wilson is the global managing director of technology research and thought leadership at Accenture Research. He is the coauthor, with Paul R. Daugherty, of Human + Machine: Reimagining Work in the Age of AI, New and Expanded Edition (HBR Press, 2024). hjameswilson

- Paul R. Daugherty is Accenture’s chief technology and innovation officer. He is the coauthor, with H. James Wilson, of Human + Machine: Reimagining Work in the Age of AI, New and Expanded Edition (HBR Press, 2024). pauldaugh

Partner Center

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Methods of increasing cultural competence in nurses working in clinical practice: A scoping review of literature 2011–2021

Training for the development of cultural competence is often not part of the professional training of nurses within the European Economic Area. Demographic changes in society and the cultural diversity of patients require nurses and other medical staff to provide the highest quality healthcare to patients from different cultural backgrounds. Therefore, nurses must acquire the necessary cultural knowledge, skills, and attitudes as part of their training and professional development to provide culturally competent care to achieve this objective.

This review aims to summarize existing methods of developing cultural competence in nurses working in clinical practice.

A scoping review of the literature.

The following databases were used: PubMed, ScienceDirect, ERIH Plus, and Web of Science using keywords; study dates were from 2011 to 2021.

The analysis included six studies that met the selection criteria. The studies were categorized as face-to-face, simulations, and online education learning methods.

Educational training for cultural competence is necessary for today’s nursing. The training content should include real examples from practice, additional time for self-study using modules, and an assessment of personal attitudes toward cultural differences.

Introduction

Current demographic changes mean that nurses need to provide quality nursing care for patients from different cultural backgrounds. Horvat et al. (2014) report that health workers will increasingly be obliged to provide healthcare to patients from different cultural groups. Eurostat (2019) states that 4.2 million people from other countries migrated to the European Union in 2019. Germany (88,630), France (29,910), Spain (29,620), and Romania (23,370) reported the largest number of immigrants. Cruz et al. (2017a) draw attention to the fact that every population group has unique norms, values, and practices that determine the group’s perception of health, which is why it is important to implement the principles of culturally specific healthcare.

Cultural competence in nursing

Cultural competence ( Ahn, 2017 ) in nursing care is essential for providing quality care for patients from different cultural backgrounds. It is a specific concept related to transcultural nursing and contains a wealth of skills and knowledge regarding cultural values, health beliefs, religion, and human philosophy. It is a concept linked to culturally specific nursing care ( Leininger and McFarland, 2002 ). Cultural competence in nursing has been defined as a set of knowledge, skills, and attitudes applied in the clinical practice of nursing in an intercultural context ( Cerezo et al., 2014 ; Paric et al., 2021 ).

Development of cultural competence of nurses

According to Horvat et al. (2014) , the development of cultural competencies is a crucial component for addressing health disparities and strategies to improve culturally competent care, and many experts agree ( Harkess and Kaddoura, 2016 ; Mariño et al., 2018 ; Curtis et al., 2019 ; Červený et al., 2020 ; Swihart et al., 2021 ). Faber (2021) adds that the education of health professionals is also a method of addressing racial and ethnic discrimination resulting from structural inequality. According to Carey (2011) , nursing schools should provide adequate opportunities to develop cultural competence. Cruz et al. (2017b) recommend that nursing schools include international standards for culturally competent nursing care.

Moreover, teaching standards should be adapted to local cultural diversity within each country. This ensures that nurses have a proper cultural context that can promote the development of cultural sensitivity, cultural adaptability, and cultural motivation. This type of education is demanding for teachers, who need to have the most up-to-date information from professional literature, constantly evaluate self-esteem, and modify educational methods to develop cultural competence ( Prosen and Bošković, 2020 ). However, according to Faber (2021) , there is a wealth of evidence in literature where researchers present the effectiveness of cultural competence training in individual health professions to be more linguistically and culturally aware. Farber also states that there are no coherent sector-wide standards for defining cultural competence, educational practice, evaluation measures, or target results.

Why is a literature review essential?

Accelerating globalization and demographic changes in society, the incidence of patients from different cultural backgrounds, language barriers, discrimination, racism, prejudice, and stereotypes are all factors that affect the quality of nursing care ( Červený et al., in press ; Shepherd et al., 2019 ; Williams et al., 2019 ; Joo and Liu, 2020 ). Prosen (2018) states that providing culturally competent nursing care for patients from different cultural backgrounds should not be seen as a privilege but as a human right. In order to eliminate barriers to quality care, it is necessary to find the best possible methods for developing cultural competence in nurses in clinical practice.

Research question

- What methods are effective at increasing the level of cultural competence?

- What factors can improve existing methods of increasing the level of cultural competence?

Aim of literature overview

The main objective of the review was to summarize the existing methods of developing cultural competence in nurses working in clinical practice.

- Determine which educational methods effectively increase cultural competence in clinical practice.

- Identify the impact of education on cultural competence.

- Identify potential opportunities to improve the development of cultural competence.

Materials and methods

This study is based on a qualitative scoping review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and a Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping review ([PRISMA-ScR], Tricco et al., 2018 ; Page et al., 2021 ; Figure 1 ) and the Participants, Interventions, Comparison, and Outcomes (PICO) listed in Table 1 .

PRISMA flow diagram of the scoping review.

Inclusion and Exclusion criteria for the scoping review.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Nurses or healthcare professionals working in clinical practice | Nursing students |

| Published in English | Retired nurses not providing direct patient care |

| Published from 2011 to 2021 | Not original research: opinion, editorial, conference abstract, systematic reviews |

| Qualitative and quantitative studies | Articles not available in English |

Methods of searching the literature

The analyzed publications were collected from the PubMed, ScienceDirect, ERIH Plus, and Web of Science databases using keywords and Booleans operatives: (“transcultural education”) OR (“training”) AND (“culturally competence”) AND (“nurses”) AND (“clinical practice”). All sources were academic publications that went through the peer-review process. The focus of this review was on the following elements:

- Population: Clinical practice nurses

- Intervention: Education to increase cultural competences

- Related: Clinical practice nurses

- Outcome: Increasing cultural competencies in clinical practice nurses through education (training)

The criteria for the selection of resources are presented in Table 1 . We searched for resources dated from 01.12.2011 to 31.12.2021.

Data charting, extraction, and quality evaluation

We used a 3-step screening process that was evaluated in MS Excel. In the first step, we searched the article’s title and abstract. In the second step, we identified and sorted articles that met the outline ranking criteria and assessed their quality. To evaluate the articles’ quality, two co-authors independently used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programe (2018) . This general tool evaluates any qualitative methodology. It has 10 questions asking the researcher to assess whether appropriate research methods were used and whether the findings were presented meaningfully ( Červený et al., 2020 ; Long et al., 2020 ). The results of the quality assessment are presented in Table 2 . In the third step, the data were extracted.

Results of critical appraisal checklist results.

Questions of quality, author(s), year, country

| , NLD | , AUS | , ROK | , FIN | , ISR | , SWE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | N /CT | N | Y | Y /CT | Y | |

| Y | CT /Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y /N | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | N /Y | Y | |

| Y | N | Y | Y /N | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Y | Y | Y | N /CT | Y | Y | |

| Final quality level/grade | ||||||

Y, Yes; N, No; CT, Cannot tell; ROK, Republic of South Korea; ISR, Israel; SWE, Sweden; AUS, Australia; NDL, Netherlands (the); FIN, Finland.

A total of 548 articles were identified based on database searches, and two other articles were added to the analysis because they met the criteria for selecting articles. After removing duplicates, we approached the analysis of titles and abstracts of individual articles. Based on the analyses of abstracts, we discarded 500 articles. Forty-two articles were selected for full-text analysis, but we discarded another 36 articles after analysis. The articles included in the scoping review were re-analyzed a week after the first reading to avoid erroneous conclusions. The data were sorted, encoded, and categorized into three themes: (1) Methods of increasing cultural competence, (2) The impact of education on the cultural competence of participants, and (3) Possibilities for developing educational programs in the field of cultural competence.

Characteristics of articles

The articles included in the analysis were published from 2011 to 2021. The articles came from 6 countries: South Korea ( Ahn, 2017 ), Israel ( Slobodin et al., 2021 ), Sweden ( McDonald et al., 2021 ), Australia ( Perry et al., 2015 ), the Netherlands ( Celik et al., 2012 ), and Finland ( Kaihlanen et al., 2019 ). Three articles used a mixed-method method ( Celik et al., 2012 ; Perry et al., 2015 ; McDonald et al., 2021 ). One article was based on a cross-sectional study ( Ahn, 2017 ), and one article used an online education intervention study ( Slobodin et al., 2021 ). Only one article utilized a qualitative study ( Kaihlanen et al., 2019 ).

In terms of study participants, in the study by Celik et al. (2012) , there were 31 paramedics, two psychiatric hospital nurses, six hospital nurses, and four nursing home nurses. Kaihlanen et al. (2019) included 20 nurses in their training program. Nurses were explicitly included in all analyzed articles, except for the study by Slobodin et al. (2021) , in which participants were described as healthcare professionals, but no further details were provided. Table 3 provides an overview of the studies included in this scoping review.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Author(s), Year | Participants | Methods | Content of training to increase cultural competence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Registered nurses ( = 14); practical nurses ( = 6) | Qualitative study | 16-h Face to Face training. The training was based on sociocultural differences, perception of pain in individual cultures, personality differences, knowledge from various cultural experts, and knowledge gained from self-reflection. | |

| Healthcare professionals ( = 303) | Pre-post web-based intervention study | An online educational program from the historical perspective of the pandemic; program objectives evaluated cultural challenges in the health sector, the importance of cultural competence in emergencies, cultural competence, knowledge, and skills in the context of COVID-19. | |

| Healthcare professionals ( = 31) | Mix-method Quantitative and Qualitative methods | The training program was based on the Deming cycle and was divided into four modules. The training focused on conceptualizing differences in healthcare between the healthcare professionals and applying instructions to address diversity in practice. | |

| Healthcare professionals ( = 60) | Mix-method Quantitative and Qualitative methods | eSimulation module was based on developing participants’ knowledge and skills to understand the role of language in healthcare and highlighting the benefits of using an interpreter in clinical work. The use of open-ended, culturally sensitive issues to address language and cultural problems at patient discharge. | |

| Nurses ( = 275) | Cross-sectional design and structured equation modeling | Hypothetical model for the development of cultural competence. | |

| Mental Healthcare professionals ( = 248) | Mix-method evaluation | Comprehensive Cross-Cultural Training included interactive lectures on cultures, psychopathology, migration discussions, and refugee-related studies. |

Theme 1: Methods of increasing cultural competence

Methods for developing cultural competencies in nurses are presented in Table 3 .

An online educational program was used in the study by Perry et al. (2015) and Slobodin et al. (2021) . Slobodin et al. (2021) divided their training sessions into eight modules lasting about 30 min. Their training was linked to the pandemic situation; therefore, the online training course included a historical review of the pandemic and its impact on the social fabric of society. The study by Perry et al. (2015) included modules lasting about 60 min that focused on understanding the importance of language in the healthcare environment, using interpreters in clinical practice, and addressing linguistic and cultural issues during patient discharge from the hospital. Celik et al. (2012) used a modified six-phase Deming cycle during four training sessions. As the authors stated, the first phase was an attention-free phase (Unawareness), where health professionals were unaware of diversity factors in healthcare and thought these factors or questions were irrelevant to clinical practice. The second phase was the phase of ‘limited” awareness, where healthcare workers realize that diversity factors exist but do not implement them in clinical practice. The first two phases, which the authors added, were followed by the usual phases of the Deming cycle (Plan, Do, Study or Check, and Act). The (Plan) in their study means: deliberately paying attention to diversity in clinical practice, the (Do) means to implement knowledge into clinical practice, the (Study or Check) means evaluating the results after implementation of culturally diverse care, and the (Act) means the implementation of modified nursing care based on that process.