- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish?

- About Research Evaluation

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

Research governance and the dynamics of science: A framework for the study of governance effects on research fields

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Maria Nedeva, Mayra M Tirado, Duncan A Thomas, Research governance and the dynamics of science: A framework for the study of governance effects on research fields, Research Evaluation , Volume 32, Issue 1, January 2023, Pages 116–127, https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvac028

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This article offers a framework for the study of research governance effects on scientific fields framed by notions of research quality and the epistemic, organizational, and career choices they entail. The framework interprets the contested idea of ‘quality’ as an interplay involving notion origins, quality attributes, and contextual sites. We mobilize the origin and site components, to frame organizational-level events where quality notions inform selections, or selection events . Through the dynamic interplay between notions selected at specific sites , we contend, local actors enact research quality cumulatively , by making choices that privilege certain notions over others. In this article, we contribute in four ways. First, we propose an approach to study research governance effects on scientific fields. Second, we introduce first- and second-level effects of research governance paving the way to identify mechanisms through which these different levels of effects occur. Third, we assert that interactions between research spaces and fields leading to effects occur in the context of research organizations, and at nine key selection events. Fourth, and lastly, we discuss an empirical test on an illustration case to demonstrate how this approach can be applied.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| August 2022 | 55 |

| September 2022 | 71 |

| October 2022 | 35 |

| November 2022 | 10 |

| December 2022 | 6 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| February 2023 | 17 |

| March 2023 | 10 |

| April 2023 | 23 |

| May 2023 | 8 |

| June 2023 | 29 |

| July 2023 | 15 |

| August 2023 | 18 |

| September 2023 | 34 |

| October 2023 | 25 |

| November 2023 | 17 |

| December 2023 | 19 |

| January 2024 | 16 |

| February 2024 | 21 |

| March 2024 | 15 |

| April 2024 | 10 |

| May 2024 | 8 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| July 2024 | 5 |

| August 2024 | 28 |

| September 2024 | 4 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1471-5449

- Print ISSN 0958-2029

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Open access

- Published: 18 February 2020

Governance of health research funding institutions: an integrated conceptual framework and actionable functions of governance

- Pernelle Smits 1 &

- François Champagne 2

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 18 , Article number: 22 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

4290 Accesses

14 Citations

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Health research has scientific, social and political impacts. To achieve such impacts, several institutions need to participate; however, health research funding institutions are seldom nominated in the literature as essential players. The attention they have received has so far focused mainly on their role in knowledge translation, informing policy-making and the need to organise health research systems. In this article, we will focus solely on the governance of national health research funding institutions. Our objectives are to identify the main functions of governance for such institutions and actionable governance functions. This research should be useful in several ways, including in highlighting, tracking and measuring the governance trends in a given funding institution, and to forestall low-level governance.

First, we reviewed existing frameworks in the grey literature, selecting seven relevant documents. Second, we developed an integrated framework for health research funding institution governance and management.

Third, we extracted actionable information for governance by selecting a mix of North American, European and Asian institutions that had documentation available in English (e.g. annual report, legal status, strategy).

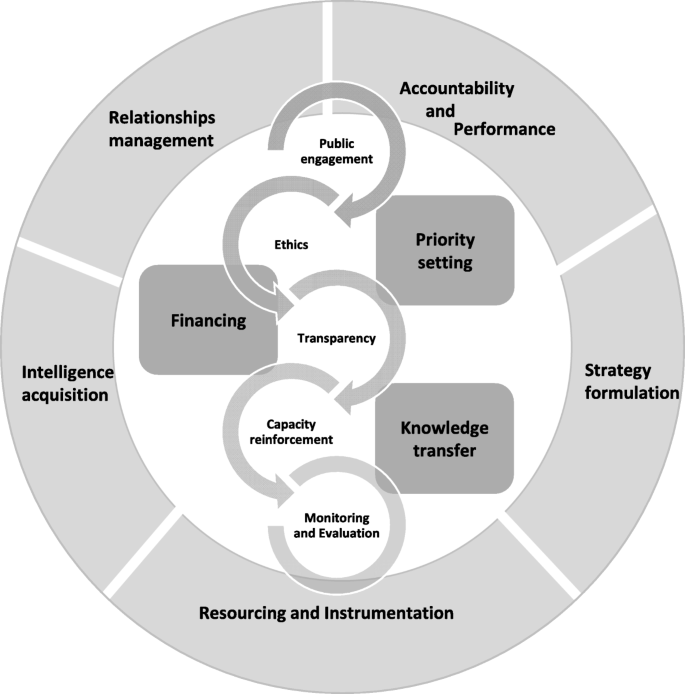

The framework contains 13 functions – 5 dedicated to governance (intelligence acquisition, resourcing and instrumentation, relationships management, accountability and performance, and strategy formulation), 3 dedicated to management (priority-setting, financing and knowledge transfer), and 5 dedicated to transversal logics that apply to both governance and management (ethics, transparency, capacity reinforcement, monitoring and evaluation, and public engagement).

Conclusions

Herein, we provide a conceptual contribution for scholars in the field of governance and health research as well as a practical contribution, with actionable functions for high-level managers in charge of the governance of health research funding institutions.

Peer Review reports

Research governance needs careful consideration, not only for the sake of good governance but also for the added benefits gained from an efficient health research sector in terms of the health of the population. To reinforce research governance, some actors advocate and push for the strong and explicit handling of fragmented science policy – policy-makers push for a pragmatic research agenda where there are benefits to the economy or to population groups, researchers advocate for the steering of research on health systems governance, and research organisations, such as universities and research funding institutions, decide on topics of focus and ways to attribute funds.

Health research, and research in general [ 1 ], has scientific, social and political impacts [ 2 ]. Health research performance can be measured in terms of productivity (i.e. number of papers per researcher), quality (i.e. number of highly cited papers), impact on healthcare quality, health status or the economic value of patented products (i.e. new devices) [ 3 ], and public engagement [ 4 , 5 , 6 ]. While there is no international consensus on the best indicators for health research [ 7 ], and there are limitations inherent to its metrics (time, attribution, etc. [ 8 ]), there is now consensus that the benefits of health research require counting, and that “ how health research systems should best be organized is moving up the agenda of bodies such as the World Health Organization ” [ 9 ].

Health research systems vary noticeably across countries, for instance, within the Western Pacific region [ 10 ], eastern Mediterranean countries [ 11 ], Latin American countries [ 12 ] or African countries [ 13 , 14 ]. A comprehensive framework would provide tools to compare systems, facilitate the identification of the range of options and guide the measurement of their characteristics in order to point out ideas for complementary arrangements.

About governance of health research by funding institutions

Health research funding institutions with a national scope encompass politics and government, advisory bodies, organisations funding research, intermediary organisations and institutions performing research, either agencies, ministries or institutes (henceforth named institutions); we refer to funding institutions of science or of health science systems that are publicly run and that cover basic and applied health research. Tetroe refers to major public research funders responsible for funding health research at the national level [ 15 ].

Few frameworks on health research systems are available. Two characteristics can be distinguished, namely governance and/or management functions. Though the ‘governance’ and ‘management’ of research might be understood and used as synonyms [ 16 ], we distinguish governance functions from those of management based on notions of internal and external environments. Following Mitchell and Shortell’s [ 17 ] typology of governance and management functions, we consider governance as being primarily concerned with positioning health research relative to the external environment in which it operates, while management is primarily concerned with daily tasks and implementation.

Broadly speaking, governance of health research “ is a framework through which institutions are accountable for the scientific quality, ethical acceptability and safety of the research they sponsor or permit ” [ 16 ].

Some frameworks might consider the health research delivery level or they may be more generic. In general, they mainly emphasise what governance or management features need to be enacted inside the organisations that deliver research, such as universities and research centres, highlighting the roles of researchers and public administrators [ 16 , 18 ] or even the potential role of policy-makers [ 15 , 19 , 20 ]. Research funding institutions are seldom nominated in the literature as essential players in health research governance (HRG). Indeed, research on funding institutions has not received broad attention [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ] but is slowly growing with WHO’s Health Research Policy and Systems initiative [ 9 ] and reflections on knowledge translation [ 25 ]. We will focus solely on HRG and the management of national funding institutions.

The intent of this paper is to provide an overall framework of HRG and management for funding institutions. The content is designed to support health research reformers, funding institution managers and government officials in charge of health research development. It applies to all research under the responsibilities of funding institutions, be it health services, public health, biomedical or clinical research.

We will first provide a framework of research governance and management applied to the health domain for funding institutions. We will then present international cases of funding institutions and how they enact functions and build upon case descriptions to draw some practical applications of the HRG functions for funding institutions. We finally discuss the applications for funding institutions.

Review of existing frameworks

Existing frameworks (Table 1 ) were identified via a grey literature search for all hits on Google using the following keywords: frame* OR model, combined with “Health research governance” OR “governance of health research” OR (“research for health” + “governance”) anywhere in the page. We also ran Google scholar [ 26 , 27 ], searching anywhere in the article, for the first 600 hits using the following keywords in the title: “Health research governance” OR “governance of health research” OR (“research for health” + “governance”).

We excluded references that were specific to one theme, for example, genomic or epidemic, as well as those dedicated to one institutional level (e.g. university), private institutions, advocacy-oriented institutions (e.g. think tanks), or a single aspect of governance (e.g. law, ethics) or a population (e.g. librarians). We included references that were specific to public organisations (e.g. agency, ministry, institute) and the national level.

Theoretical development of conceptual integrated framework

The methodology to develop the framework of HRG is based on the integration of the existing frameworks related to (health) research governance and to the governance of health [ 28 ].

One author of the present paper read the identified frameworks and classified the dimensions lists as per their governance, management or principles content. Whenever the authors provided a classification, we copied and pasted what they considered governance, management or principles into our documentation. When authors did not provide any specific classification, we used the definitions of governance and management used to develop the integrated framework. Governance refers to broad functions or ‘know-why’, the vision and relationships to the external environment, management refers to ‘know-what’ and operational daily tasks carried out within the environment of the institution, and transversal functions refer to ‘know-how’. Those transversal functions are, in essence, the principles that apply to governance and management functions.

Practical application of newly developed framework to a sample of institutions

The methodology used to analyse cases was a two-step process involving the selection of countries (Table 2 ) and institutions (Table 3 ). We sought research funding institutions from a diversity of countries. The selection of countries rests upon the acknowledged leadership in English-speaking health research production and a mix of North American, European and Asian countries.

The criteria for being a major provider of research funds were being funding institutions from the public sector, national in scope, funding health-related research and being a major provider of research funds. A team composed of professors, researchers, consultants and managers from funding institutions and research centres (total of 6 individuals; 2 from the field of governance, 1 finance, 1 academic training, 2 international management, equally coming from academic and practical background; 4 of these directly worked with funding institutions) selected the cases.

The information included in this study was extracted from documentary sources, including reports of the selected funding institutions available as of November 2018 (annual report, strategic plan), related strategic information whenever available from the website of the selected funding institutions as consulted in November 2018 (e.g. organisational chart, procedures, mission), and the legal status of the selected funding institutions (i.e. the constitutive act in force) (See Appendix – data sources for further details). Some institutions documented their strategy and actions at much more detailed levels than others; we considered what was mentioned independently of the level of detail.

One member of the study team read through all documentation, and then extracted and classified information relevant to the stated dimensions of the framework (Tables 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 and 10 ). A round of verification and collection of complementary data took place by sending a request to each institution for comments from the direction of communication, cc’d to the contact of the head manager of each funding institution. Out of seven institutions contacted, we received three answers. The institutions were asked for the following information: (1) to complete information about their institution, and (2) to comment on the validity of the five governance-related dimensions (e.g. Do they make sense to you? Are they clear? Anything missing?).

Brief review of the existing frameworks

A national framework on HRG outlines the understanding of a government about its vision of health research, internal and external roles, and the philosophy behind running high-standard health research. It is a formal statement on how to improve research and safeguard the public [ 29 ]. It gives clear directions on what to work on and how to practice efficiently in order for the population to benefit from health research results and new knowledge. Such frameworks eventually include people, institutions and activities, and enable the health research system to generate and use knowledge for the benefits of health. A framework provides a systematic tool to portray the health research system in a systematic manner [ 30 ].

At least eight recent frameworks on health research are available – the Department of Health in the United Kingdom published a framework that gives details on standards and responsibilities for health research [ 31 ]; the Council on Health Research for Development (COHRED) developed a framework with technical components of particular aspects of health research systems [ 32 ]; Pang et al. synthesised a consultation on the foundation for health research systems [ 33 ]; Rani et al. presented the governance and management functions extracted from a consultation in low- and middle-income countries [ 10 ]; the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) offers principles and stewardship details for the collection and use of data overall [ 34 ]; the European Observatory mainly provides a set of principles that can be divided into managerial and governing mechanisms [ 35 ]; and, finally, the Australian Research Council sets a step-wise framework to manage research projects [ 36 ].

Some frameworks focus more on research governance for research institutions (universities, etc.), others encompass research governance for funding institutions. Indeed, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the National Health and Medical Research Agency (NHMRC) frameworks focus extensively on the aspects that need to be considered by an institution receiving NICE or NHMRC funds. In these frameworks, dimensions are closer to a set of steps to be filled from the inception to the closing of a research project. All other frameworks refer to governance (sometimes called “ stewardship ” by Pang et al. [ 33 ]), management and a set of more or less detailed principles. Explicit concerns for ethics and public participation are prevalent among these principles (see Table 4 , columns C1 to C8).

Some frameworks provide an overarching set of dimensions, whereas others delve into the specifics of either management or governance. Indeed, the COHRED and European Observatory frameworks are both designed as overarching frames, covering multiple dimensions. In the case of COHRED, 15 dimensions provide many details on principles for managerial- or governance-related aspects. The European Observatory framework similarly gives a broad view of what dimensions to consider, although it condenses the number of dimensions down to five.

The European Observatory framework appears as the most overarching framework. Each of the principles proposed is accompanied by a set of specific mechanisms that help those in charge of governance or managerial functions to act accordingly. For instance, the principle ‘accountability’ includes mechanisms for managerial functions, such as competitive bidding, and some mechanisms for governance purposes such as conflict of interest policies and codes of conduct.

The COHRED framework is based on ‘key aspects’ of health research and has ‘action guidelines’ attached to each of them, covering governance and management functions. Key aspects include a conducive environment for ethics and leadership, a solid base of policies, priorities and management, and the ability to perform and produce in the areas of resources, optimisation and international integration. It is formatted in the spirit of a step-by-step guide to improving research governance at the national and institutional levels. It lists good practices and advice such as formalising partnership arrangements and ensuring transparency through the ranking process.

Pang et al.’s [ 33 ] framework builds four functions. One essential pillar is ‘stewardship’, whereby vision, priorities and monitoring provide direction for health research. ‘Financing’ makes it possible to get funds in and to allocate funds with accountability; the ‘creation and sustainability of human and physical resources’ and ‘the production and use of research’ complete the framework. Note that production and use of research belongs to both the governance functions and the management functions categories if organisations are performing research and knowledge transfer. Accountability is related to financing.

Rani et al. [ 10 ] propose essential governance and management functions based on consultation with low- and middle-income countries, advocating for the improvement of ethics committees and of registries to record funding and research data.

The CIHR framework is organised into five main functions of governance. As the framework relates both to health research and health-related data, the dimensions reported have a digital flavour, focusing on data quality, open access, data visibility and so forth. The transfer of these five broad guiding principles and five components (vision, culture, resources, skills, access) can easily apply to organisations and systems running research projects, right up to health research governing bodies such as funding institutions. This framework is particularly concerned with reaching out to all involved stakeholders and with compulsory actions, specifying who is responsible and what activities have to be checked and approved.

The NICE framework is particularly concerned with each and every person working at or for NICE itself, clarifying the roles, responsibilities and institutions to contact in different scenarios.

NHMRC’s Australian framework provides a roadmap for those organisations and systems running research projects who need to comply with high-standard research governance.

All the above frameworks seem relevant for a funding institution. In the following section, we propose an integrated framework. Dimensions that were cited by others are integrated into the encompassing governance and management HRG framework that we propose below. We distinguish which functions are more closely related to management functions and which are more closely related to principles or governance.

Conceptual integrated framework on governance and management of health research by funding institutions

We propose to build the Framework on Governance of Health Research (FGHR) upon these existing frameworks (Table 4 , column C9). FGHR also grows out of our understanding of governance in health research and health systems, our observation of governance practices in health research and health systems, and the inputs from the above frameworks. We acknowledge that, at times, delimitations might be blurry between governance and management functions. Therefore, we decided to organise the FGHR around three groups of functions (governance, management, transversal functions), as presented in Fig. 1 . Here, governance is shown on the outside of the figure, representing broad functions (or know-why), management functions (or know-what) are shown inside the circle and are run within the standards set by governance and some transversal encompassing functions are present in both governance and management levels (or know-how).

Framework on governance of health research

The composition of FGHR reflects governance functions, management functions and transversal functions. Governance functions reveal the steering activities that actors and institutions must undertake to ensure a fit between the health research system and the external environment. Management functions correspond to activities to be carried out internally on a daily basis to ensure the pursuit of health research for funding institutions, universities, research centres and principal investigators. Transversal functions qualify management functions and the effects required from the actualisation of governance functions. The term refers to good practices and excellence in the exercise of management and governance in health research, namely transparency, capacity-building, monitoring and evaluation, and ethics.

FGHR is composed of five governance functions, three management functions, and four essential types of know-how. The framework’s five governance functions are ‘intelligence acquisition’, ‘resourcing and instrumentation’, ‘relationship management’, ‘accountability and performance’, and ‘strategy formulation’. Intelligence acquisition is the production and acquisition of the knowledge necessary for providing a vision for the health research that the organisation supports and for the consultation and recruitment of adequate expertise. Resourcing and instrumentation refers to the acquisition and generation of the means to achieve strategic goals through board meetings, reports and reviews, inward flow of monetary resources, and the means to support the development of governance structures and activities such as explicit responsibility and task descriptions. Relationship management is concerned with ensuring good and efficient connections, both with the external environment and internally with insiders such as the direction committee. Accountability and performance relate to the ability of the organisation to exercise good governance through instituting the means to track its own development and activities as a governance structure. This function relates to a reflexive capacity of governance. Formulating mission and vision is the process of setting up the strategic content, mission, vision and priorities with adequate policies and ethical codes to exercise governance functions.

The framework’s three management functions are ‘priority-setting’, ‘financing’ and ‘knowledge transfer’. Priority-setting refers to the process of setting up midterm actions that match the vision of the organisation. Financing refers to the outward flow of monetary resources as funds are allocated. Knowledge transfer covers the organisation’s support for knowledge-transfer activities. It can be organisation-led, such as the funding institution facilitating meetings between the scientific community and politicians, or related to research funding, whereby researchers can apply for specific knowledge-transfer grants.

The five transversal functions of the framework are based on essential types of know-how underlying HRG and management; they are ‘ethics’, ‘transparency’, ‘capacity reinforcement’, ‘monitoring and evaluation’, and ‘public engagement’. Ethics refers to the quality of a process, either governance functions or management functions in the selection of board members or in the attribution of grants through peer-review processes. Transparency refers to the disclosure of procedure and results, for example, having clear and publicly available criteria for election to boards and committees, posting the names of successful research grant applicants online, or providing free access to publications. Capacity reinforcement relates to a continuous organisational effort to support the development of human resources, in terms of either board members or staff employed by the organisation in a management function as well as the support for capacity development when funding students. Monitoring and evaluation cover processes of data collection and analysis to follow-up on, estimate the performance of, and benchmark organisational processes and results. Public engagement refers to efforts to reach out and/or integrate the population or groups of the population in an authentic and continuous decision-making process.

This FGHR intends to establish principles for carrying out health research at the national level. The scope of the FGHR covers the responsibility of the public system for the governance of health research – from the top-level decision-making organisations that fund research to the recipient organisations that implement research projects in health domains. The framework is directly relevant to those who target, fund, manage, host, conduct, participate and accredit health research. It can theoretically apply to all health research related to studies sponsored by the ministry level, to research carried out within a geographical area, and to research funded totally or partially with national-level public funds.

The framework seeks to establish the essential functions and values of health research conduct. Existing requirements binding research communities or existing laws and requirements designed to protect research participants, to ensure confidentiality, and so forth, are not integrated at this point. The responsibilities of institutions and actors can be defined in future steps.

These governance functions do corroborate some of the governance tasks for research policy and practice in health mentioned by Mitchell and Shortell’s [ 17 ], namely obtaining financial resources and providing measures for accountability.

Practical application of the newly developed framework in terms of governance

We further refer to actionable functions as useful actions [ 37 ] that bring clear directions [ 38 ] to enact governance. We decided to focus solely on governance functions because much is already written on management and ethics in research.

Description of the research environment by case

Each year, funding institutions individually invest between US $90 million and US $31 billion in health research to fund researchers, trainees and projects. Some countries, such as Canada and the United States, organise their budget around thematic research organisations and some countries flag available funding on thematic studies rather than organisations (Table 5 ).

A direct comparison between funding institutions is difficult to establish, with some reporting the prevalence of researchers and trainees currently supported on a yearly basis, others the incidence of researchers and trainees newly funded during the year. A wide diversity prevails in terms of funding models. CIHR in Canada favours investigator-initiated grants, whereby researchers nominate a topic of research in which they are proficient and for which they would like to receive funding. In Singapore, the opposite dynamic seems to prevail, with the majority of funds dedicated to targeted grants on specific topics of interest to the government. Our main intent in presenting several cases is to provide a practical look at various governance frameworks and to extract empirical applications.

Analysis of governance functions in health research funding institutions by case

Intelligence acquisition

‘Intelligence acquisition’ refers to the means put in place by funding institutions to acquire their strategic knowledge and expertise. The design of funding institutions’ strategic actions might be influenced by the policy domain, for example, by government authorities or ministries. In such a situation, these inputs come from a logic of top-down representative democracy. A mixture of bottom-up inputs also seems to be widespread in funding institutions, with the participation of direct and indirect beneficiaries of funded health research; indeed, patients, the public and researchers do contribute their share of knowledge to formulate, comment on or format policies.

While funding institutions do receive some inputs, they might also look for information directly relevant to their mission as it emerges. To do so and remain open to environmental opportunities, a proactive structure might be put in place to investigate early policy developments of interest to the institution, as is done in the Netherlands (Table 6 ).

The mobilisation of external knowledge may be complemented by knowledge acquisition on the internal processes of a funding institution. In so doing, the institution presents a strong signal that it is a learning organisation willing to adjust as needed. Internal reviews provide evidence on which to build a continuous improvement dynamic, both within the funding institution and for its external partners. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) explicitly places a high priority on learning processes – its strategic plan proposes that it will excel as a federal institution, it reviews its peer-review processes, uses bibliometrics to indicate the value of a programme, conducts PhD workforce analysis so as to better predict the optimal number of fellows the NIH can support, and reduces the administrative burden by distinguishing between unavoidable burdens and those that are merely due to custom or habit.

As a conclusion to the dimension of intelligence acquisition, one operational and empirical application would be to consider the following aspects:

Top-down versus bottom-up influence of outsiders

Proactive versus reactive knowledge hunting

Presence versus scarcity of organisational learning procedures

Strategy formulation

‘Strategy formulation’ refers to the exchange processes that guide the actions of founding institutions. It can take the form of developing founding documents and principles. The evidence to feed such long-term and structural decisions comes from insiders from the health research system, researchers, academics, health ministry representatives, and so forth. It might also derive from the ultimate beneficiaries of health research (citizens) and those outside the system (congress members, etc.). Another difference between the funding institutions that are developing their long-term vision, mission and policies is their openness and integration of non-health-related actors and whether it is solely focused on the health sector or not. Some institutions call for medical providers and health institutes to collaborate on the design and elaboration of a strategy. However, because the health sector opened up decades ago to the wide range of determinants of health, it is now well established that the health of the population is largely dependent on interventions made in sectors that do not fall under the jurisdictions of health ministries. Therefore, the involvement of non-health-labelled institutes and representatives is or has to be considered by funding institutions; for example, Australia’s funding institution opens its strategy to online commentary from any sector (Table 7 ).

As a conclusion to the dimension of strategy formulation, one operational and empirical application would be to consider the following aspects:

Research insider versus research outsider

Single health sector versus multiple sector inputs

Resourcing and instrumentation

‘Resourcing and instrumentation’ refers to the tools that are put in place to finance, fund and support the development and implementation of an institution’s strategy. Financing is the act of collecting and receiving money to run the institution; the sources of money can be public and/or private. The NIH, for example, is much closer to the private sector than other institutions portray themselves to be. Instrumentation, such as guidelines and policies, is developed for the internal functioning of an institution; for example, the description of selection criteria for committees. Online tools might also be available to support research external to the institutions, for example, the guidelines for university ethics committees as provided in Australia. Support given to researchers might be facilitated through open resources where researchers compete on broad-spectrum grants or be targeted to the needs of some government agenda or ministry priority, as happened in Australia when the then Minister of Health and Ageing requested additional committees (see Table 8 ). The organisational processes involved in providing money to universities, grantees, scholars and research centres – both public and private – so as to implement institution programmes through projects funded can be closely informed to reframe funding schemes. To encourage high standards of research, and highly competitive researchers, institutions look at ways to move forward in a globalised research environment and to support researchers accordingly. Sweden, for example, is reflecting upon researchers’ mobility. To align with institutions’ missions to bring value to the population and improve health, institutions such as those in the United Kingdom, propose a model of reporting in which care is explicitly taken to use plain English in order to favour clear communication of funding applications (Table 8 ). In this way, institutions encourage both international engagement and the translation of research results into health practices.

As a conclusion to the dimension of resourcing and instrumentation, one operational and empirical application would be to consider the following aspects:

Providing support material for the entire research community versus restricting it to grantees

Providing open grants versus targeted grants

Pushing or not for linkages to healthcare benefits

Questioning or not competitiveness in a globalised research environment

Management of relationships

‘Management of relationships’ refers to the preoccupation with interacting in meaningful and constructive ways with the institutions’ partners – be they insiders of the institution, such as the heads of the constituting institutes of an institution at CIHR Canada, or outsiders such as politicians or institutions unrelated to the health sector.

Some institutions run activities and set seats on boards for their internal partners (CIHR scientific agency, see Table 9 ). They might also connect with outside funding institutions to set up multi-institution funding for innovations or grants covering boundary work and transversal research. Such efforts to build up complementary programmes and to invite collaborators might be customary or recurrent. Over time, such recurrent relationships and exchanges with outsiders become institutionalised in the institution processes. They might also be at the pilot-testing phase or in an early development stage, when institutions establish bridges with partners on a more intermittent basis. In 2005, CIHR in Canada organised a pilot project with parliamentarians named ‘Health Researcher’s Day on the Hill’, and planned to send newsletters to members of Parliament three times a year since 2012 [ 41 ]; in Sweden, researchers and politicians are convened to a shared event on a yearly basis.

As a conclusion to the dimension of management of relationships, one operational and empirical application would be to consider the following aspects:

Internal versus external partners

Intermittent versus recurrent partnerships

Accountability and performance

‘Accountability and performance’ is the process by which a funding institution follows its own development and activities and is reflexive about its governance capacity. Because funding institutions might or do oversee the quality and integrity of the research they are funding, some have developed procedures to ensure high standards for research quality. Follow-up on research quality can take the form of inquiry into fraud in attributions of funding and the manipulation of results. Sweden, stricken by the Macchiarini case on gross scientific misconduct [ 42 ], installed a Research Misconduct Board to address such issues. Publishing information online regarding, for example, who sits on committees, who receives funds, and what type and amount of funding is received is another transparency mechanism employed by funding institutions such as CIHR in Canada and the NHS in the United Kingdom (Table 10 ).

Additionally, what happens behind the closed doors of granting committees might take different forms. It might address the internal processes of committees, their selection criteria or their mandates, or it might address the committee’s final decision regarding the list of grantees. An institution might therefore focus more or less on disclosing its internal procedures or on its committees’ final decisions.

As a conclusion to the dimension of accountability and performance, one operational and empirical application would be to consider the following aspects:

Disclosure from process to results

Follow-up on diverging behaviour or not

Whether to put committee-related information online or not

In conclusion, we extracted a few specific operational dimensions salient to the governance of health research by funding institutions (Table 11 ).

We would like to discuss the validity of the framework for governance of health research funding institutions.

One could argue that the framework is not valid because it is based on a limited set of existing frames. Here, it is assumed that a sample is sufficient for the identification of elements of governance. A framework can be developed from a deductive approach, mobilising a catalogue of theories and knowledge from scholars. It can also be developed from an inductive approach, this time mobilising hands-on knowledge from the institutions themselves. We mainly borrowed from both approaches to develop the integrated framework, being rooted in practice, and also keeping an open door to the approaches of scholars who might have previously developed deductive frameworks. The literature refers to publications by Rani et al. [ 10 ] and Pang et al. [ 33 ], both of which use practitioners’ consultations to draw their framework.

The strength of the integrated framework will also rely upon developing it on high variability cases, including internal variability among institutions and external variability among the institutions’ national environments. The selected institutions of this study cover all health research topics rather than simply topics that fall under unique categories of medical research (e.g. stem cell), social sciences and humanities (e.g. management of primary care), or engineering (e.g. radiation therapy); they are quite homogeneous in that regard. However, at this stage, we applied the integrated framework to seven cases, and observed a wide variability of capacities within each research funding institution. In the United States, the NIH was created in 1930 and cumulates almost 90 years of experience, whereas the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health Research was the last to be established in 2006, from the evolution of a previous agency. Canada’s CIHR operated on around US$ 800 million in 2017–2018 (equivalent to over CAN$1 billion), whereas Singapore’s National Medical Research Agency mobilises about half that budget, at US$ 492 million in 2016, leading to a population equivalent of approximately one-seventh that of the Canadian one. Having highly variable internal capacity and yet still portraying a similar set of governance dimensions reinforces the strength of the framework, especially its governance functions. Following a similar line of reasoning, all seven cases operate in diverse national environments and still present consistency through the presence of the five governance functions. Altogether, we argue that the variability of cases reinforces the validity of the governance functions.

Another issue that might arise is that selected institutions might not make it possible to portray the extent of the dimensions of governance at stake. The dimensions first come from the review of frameworks in use, which were then put to the test on seven cases. Notice that we do not intend here to claim that one funding institution is doing a better job than another, or to compare across cases; the highlight is on dimensions, not cases. Any initial dimension that was irrelevant can be expected to be absent from cases, though this was not observed herein. All five governance functions were indeed mentioned by all seven cases. Additionally, one could argue that, initially, we might have missed a dimension important to governance, which is conceptually correct. Furthermore, the analysis of cases would not have made it possible to identify extra dimensions in an easy way as we did not look for a specific additional dimension, nor might such an extra dimension be easily identifiable through documentary analysis. Thus, the test of the governance functions on seven cases could invalidate a dimension if it were to be absent in one or more cases (especially for institutions outside Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom that were also feeding the review of the frames), and it could temporarily validate the importance of an initial dimension that was present in all cases, yet it cannot validate the extent of the governance functions.

Note that this study by no means provides an exhaustive list of HRG settings and mechanisms in selected countries, nor does it compare which funding institutions perform best. Additionally, the intent of this analysis of actionable functions is to identify pragmatic actions under the dimensions (only in terms of governance) of the framework rather than to assess the same institutions on these dimensions.

Although research is ultimately undertaken by researchers in public or private organisations, universities, institutes and centres, we do not intend to provide a framework for institutions hosting research projects, for example, organisations such as the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation, which recently published a governance framework and policies, mainly for its board.

Two main contributions come out of this work. First, we bring a conceptual contribution for scholars in the field of governance and health research. We developed an encompassing framework for the governance of health research by national funding institutions. The framework contains 13 functions, wherein 5 are dedicated to governance, 3 dedicated to management, and 5 dedicated to transversal principles that apply to both governance and management. The framework grew out of the combination of existing governance frameworks for health research funding institutions. Second, we bring a practical contribution for high-level managers in charge of governance of health research funding institutions. The framework was broken down into operational dimensions of governance to render the governance function of the framework more actionable. The operational dimensions are extracted from a multiple-case study of seven selected health research funding institutions from North America, Europe and Asia, and the specific actions they put in place to exercise their governance, especially regarding intelligence acquisition, strategy formulation, resourcing and instrumentation, management of relationships, and accountability and performance.

The framework is useful in several ways, namely to point out low-level governance and to track, measure and forestall it. In a sense, pointing out low-level governance can help funding institutions by illuminating whenever one or more functions are given little to no attention. An institution that does not manage partnerships in a diverse and efficient way, seeking out inputs from one or two key players in the private sector, for instance, will be poor at answering the health challenges of its population. It will not perform as well as an institution with open processes that feed the debate as to which challenges must be addressed in the health sector and other sectors that determine the health of the population. Though one institution might, at its inception, choose to focus on one privileged relationship with a specific national partner, governance maturity towards more encompassing actions for improving health through research will, in the long run, rely on a more diverse set of partnerships.

The framework can help in tracking the maturity curve of governance for an institution. Take, for instance, an institution willing to shift gears towards stronger influence in health research – surely tightening ties with partners or focusing funding and exploring wider funding contributors would be an option. The framework could be starting material for performance measurement on the institution’s governance. It could help to develop indicators on each function so that a board can follow-up changes in governance style – putting more or less emphasis on intelligence acquisition or on accountability, or else putting more or less emphasis on some more operational aspects of governance, for instance, acquiring intelligence from institutions’ top influencers, such as politicians, or else making sure citizens get a stronger voice in the governance discussion of institutions. Finally, the framework can be of use to forestall unwanted shifts in governance. Being aware of the current type of governance of the institution, leaning more or less towards one function or another, being more or less prone to the top-down or bottom-up influence of outsiders, for instance, merely implies the institution could take measures against travelling down a road it did not intend to take.

What is left to be done regarding governance of health research funding institutions? We suggest four avenues. Governance does not stand alone as a single action that high-level managers run. Governance is underpinned by principles, or in other words, by what it means for those institutions to operate ‘good’ governance. We suggest those principles are ethics, transparency, capacity reinforcement, monitoring and evaluation, and public engagement. These compose the underlying know-how that applies to either governing or daily management. Further investigation is needed into what it means, in operational terms, to engage the public in accountability or in resourcing, and the like. Additionally, governance runs hand in hand with daily management. Further thought must be given to the complementarity of governance and managerial functions – what does it mean in operational terms? Additionally, and perhaps more intriguingly or more promisingly for better health research, what are the operational governance actions that are in contradiction with some of these operational management actions in place in funding institutions? Finally, in some countries, provincial research funding institutions are key players in funding research and might or not align with national governance standards. Investigating governance functions and actionable functions for provincial funding agencies is an avenue. The same governance and management functions would likely apply to any organisation across health research. The ways in which each function translates into operations in practice is more likely specific by level.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are listed in the Appendix.

Abbreviations

Canadian Institutes of Health Research

Council on Health Research for Development

Framework on Governance of Health Research

Health research governance

National Health and Medical Research Agency

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

National Institutes of Health

Nederhof AJ. Bibliometric monitoring of research performance in the Social Sciences and the Humanities: A Review. Scientometrics. 2006;66(1):81–100.

Article Google Scholar

Reale E, Avramov D, Canhial K, Donovan C, Flecha R, Holm P, et al. A review of literature on evaluating the scientific, social and political impact of social sciences and humanities research. Res Eval. 2018;27:298–308.

Panel on Return on Investment in Health Research. Making an Impact: A Preferred Framework and Indicators to Measure Returns on Investment in Health Research. Ottawa: Canadian Academy of Health Sciences; 2009. p. 136.

Google Scholar

Neubauer C. Gouvernance de la recherche – Régulation, organisation et financement 2012. https://sciencescitoyennes.org/gouvernance-de-la-recherche-regulation-organisation-et-financement/ . Accessed 1 June 2019.

Staley K, Buckland SA, Hayes H, Tarpey M. ‘The missing links’: understanding how context and mechanism influence the impact of public involvement in research. Health Expect. 2014;17:755–64.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hanney SR, González-Block MA. Building health research systems: WHO is generating global perspectives, and who’s celebrating national successes? Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14(1):90.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

European Commission Expert Group on Assessment of University-Based Research. Assessing Europe’s University-Based Research Expert Group on Assessment of University-Based Research. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2010. p. 154.

El Turabi A, Hallsworth M, Ling T, Grant J. A novel performance monitoring framework for health research systems: experiences of the National Institute for Health Research in England. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:13.

Hanney SR, González Block MA. Building health research systems to achieve better health. Health Res Policy Syst. 2006;4:10.

Rani M, Bekedam H, Buckley BS. Improving health research governance and management in the Western Pacific: A WHO Expert Consultation. J Evid Based Med. 2011;4(4):204–13.

Kennedy A, Khoja TA, Abou-Zeid AH, Ghannem H, IJsselmuiden C. National health research system mapping in 10 Eastern Mediterranean countries. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14(3):502–17.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Salicrup LA, Cuervo LG, Jiménez RC, Salgado de Snyder N, Becerra-Posada F. Advancing health research through research governance. BMJ. 2018;362:k2484.

Onyemelukwe-Onuobia C. Health Research Governance in Africa: Law, Ethics, and Regulation. New York, NY: Routledge; 2018.

Mbondji PE, Kebede D, Zielinski C, Kouvividila W, Sanou I, Lusamba-Dikassa P-S. Overview of national health research systems in sub-Saharan Africa: results of a questionnaire-based survey. J R Soc Med. 2014;107(1_suppl):46–54.

Bogenschneider K, Corbett T. Evidence-Based Policymaking. New York: Routledge; 2010.

Walsh MK, McNeil JJ, Breen KJ. Improving the governance of health research. Med J Aust. 2005;182(9):468–71.

Mitchell SM, Shortell SM. The governance and management of effective community health partnerships: a typology for research, policy, and practice. Milbank Q. 2000;78(2):241–89 151.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Joint Research Compliance Office Imperial College London. Research Governance UKNA. http://www.imperial.ac.uk/joint-research-compliance-office/research-governance/ . Accessed 1 June 2019.

Olsson A, Cooke N. The Evolving Path for Strengthening Research and Innovation Policy for Development. Paris: OECD. 2013. p. 70.

European Commission's science and knowledge service. Framework for Skills for Evidence-Informed Policy-Making. Commission Européenne, editor. 2017.

Graham I, Tetroe J. Getting evidence into policy and practice: perspective of a health research funder. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18:46–50.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tetroe JM, Graham ID, Foy R, Robinson N, Eccles MP, Wensing M, et al. Health research funding agencies’ support and promotion of knowledge translation: an international study. Milbank Q. 2008;86(1):125–55.

Ettelt S, Mays N. Health services research in Europe and its use for informing policy. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2011;16:48–60.

Smits PA, Denis J-L. How research funding agencies support science integration into policy and practice: an international overview. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):28.

Cordero C, Delino R, Jeyaseelan L, Lansang MA, Lozano JM, Kumar S, et al. Funding agencies in low- and middle-income countries: support for knowledge translation. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(7):524–34.

Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, Kirk S. The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searchinG. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138237.

Dixon L, Duncan C, Fagan JC, Mandernach M, Warlick SE. Finding articles and journals via Google Scholar, journal portals, and link resolvers: usability study results. Ref User Serv Q. 2010;50(2):170–81.

Denis J, Pomey M, Champagne F, Tré G, Preval J. In: Qmemtum Quarterly, editor. Accreditation Canada’s New Governance Framework for Healthcare Organizations and Systems. Canada; 2008. p. 33–7.

Department of Health. Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care, UK. London: DOH; 2005.

World Health Organization. World Report on Knowledge for Better Health Strengthening Health Systems. Geneva: WHO; 2004. p. 162.

Health Research Authority, UK Health Departments. UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research. London: Health Research Authority (HRA) and the UK Health Departments; 2017. p. 40.

Council on Health Research for Development. Annual Report. London: Council on Health Research for Development (COHRED); 2011. p. 20.

Pang T, Sadana R, Hanney S, Bhutta ZA, Hyder AA, Simon J. Knowledge for better health: a conceptual framework and foundation for health research systems. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(11):815–20.

PubMed Google Scholar

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. CIHR Health Research and Health-Related Data Framework and Action Plan Canada 2017. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/50182.html . Accessed 1 June 2019.

European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Series. Strengthening Health System Governance Better Policies, Stronger Performance. London: Open University Press; 2016.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Research Governance Handbook: Guidance for the National Approach to Single Ethical Review. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2011.

Hysong SJ, Best RG, Pugh JA. Audit and feedback and clinical practice guideline adherence: making feedback actionable. Implement Sci. 2006;1:9.

Kallen MC, Roos-Blom M-J, Dongelmans DA, Schouten JA, Gude WT, de Jonge E, et al. Development of actionable quality indicators and an action implementation toolbox for appropriate antibiotic use at intensive care units: a modified-RAND Delphi study. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207991.

Tiessen J. Health and Medical Research in Sweden. Observatory of Health Research systems. Cambridge: RAND Europe; 2008. p. 61.

Government of Sweden. Research Funding in Sweden 2015. https://www.government.se/government-policy/education-and-research/research-funding-insweden/ . Accessed 1 June 2019.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. CIHR’s Framework for Citizen Engagement Canada 2012. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41270.html . Accessed 1 June 2019.

Hawkes N. Macchiarini case: seven researchers are guilty of scientific misconduct, rules Karolinska’s president. BMJ. 2018;361:k2816.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Beverley Mitchell for her work reviewing the draft and respondents from the institutions.

This paper was developed after a work commissioned in 2012 as part of a contract between the co-authors and the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Montréal. The institution did not intervene in any way, nor did it read, comment on or approve the manuscript at any stage.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Université Laval, Pavillon Palasis Prince, 2325 Rue de la Terrasse, Québec, QC, G1V 0A6, Canada

Pernelle Smits

Département d’Administration de la santé, University of Montréal, 7101 Avenue Parc, Montréal, Québec, H3N 1X7, Canada

François Champagne

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

PS developed the article and analysed data. FC commented the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Pernelle Smits .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Data sources

Sources for the United States of America:

National Institutes of Health (NIH)-Wide Strategic Plan Fiscal Years 2016–2020.

Website of NIH on strategic plan and mission (consulted June 4th, 2019, at https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/what-we-do/mission-goals ).

Sources for Canada:

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Act, S.C. 2000, C.6.

CIHR. 2015. Health Research Roadmap II: Capturing Innovation to Produce Better Health and Health Care for Canadians. Strategic Plan 2014/15–2018/19.

CIHR Annual Report 2017–18.

Website of CIHR on strategic plan and mission (Consulted June 4th, 2019, at http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/22754.html ).

Sources for Australia:

National Health and Medical Research Agency (NHMRC) Strategic Direction 2015–16 to 2018–19.

National Health and Medical Research Council Act 1992. No. 225, 1992 as amended.

NHMRC Annual Report 2016–2017.

Website NHMRC on strategic plan and mission (Consulted June 4th, 2019 at https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/publications/nhmrc-corporate-plan-2018-2019#toc__32 ).

Sources for Singapore:

National Medical Research Agency (NMRC) Translating Research into Better Health Annual Report FY2016.

Website of NMRC on strategic plan and mission.

Website of NMRC Who we are (Consulted June 4th, 2019 at https://www.nmrc.gov.sg/who-we-are ).

Sources for Sweden:

Tiessen, J. (2008). Health and Medical Research in Sweden. Observatory of Health Research systems. In (pp. 61). Europe: RAND Europe.

Website of the Swedish Research Agency (Vetenskapsrådet, SRC) on strategic plan and mission (Consulted June 4th, 2019 at https://www.vr.se/english/analysis-and-assignments/research-infrastructure/ess-in-sweden/the-swedish-research-councils-ess-mandate.html ).

Stafström, S. Date not available. The Swedish Research Council Overview and current issues. Vetenskapsradet.

Sources for the United Kingdom:

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). Annual Report 2016–2017. Improving the Health and Wealth of the Nation through Research.

Website of NIHR on mission and vision (consulted June 4th, 2019 at https://www.nihr.ac.uk/about-us/our-themes/ ).

NIHR. 2013. A brief overview of the National Institute for Health Research.

Sources for The Netherlands:

Website of the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMW) on mission and vision (Consulted June 4th, 2019 at https://www.zonmw.nl/en/about-zonmw/policy-priorities/ ).

Website of International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment about ZonMW (Consulted June 4th, 2019 at http://www.inahta.org/members/zonmw/ ).

ZonMw. Date not available. The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development. Brochure.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Smits, P., Champagne, F. Governance of health research funding institutions: an integrated conceptual framework and actionable functions of governance. Health Res Policy Sys 18 , 22 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-0525-z

Download citation

Received : 04 June 2019

Accepted : 05 January 2020

Published : 18 February 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-020-0525-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Health Research Policy and Systems

ISSN: 1478-4505

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Website navigation

In this section

- Imperial Home

- Support for staff

- Research Office

- Research governance and integrity

What is research governance?

This section provides guidance on the responsibilities of the College in relation to research governance and principles of good practice for health and social care research

Research governance can be defined as a broad range of regulations, principles and standards of good practice that exist to achieve and continuously improve research quality across all aspects of healthcare in the UK and worldwide. It can also be defined as regulations, principles and standards for projects outside of healthcare research, including good study conduct.

Who does it apply to?

Research Governance applies to everyone connected to research including Chief Investigators, Researchers, their employer(s) or support staff. For those in healthcare research it can also apply to those in a healthcare role, such as care professionals.

By healthcare research, we mean any health-related research which involves humans, their tissue and/or data.

Examples of such research would include:

- Analysis of data from a patient's medical notes

- Observations

- Conducting surveys

- Using non-invasive imaging

- Using blood or other tissue samples

- Inclusion in trials of drugs, devices, surgical procedures or other treatments

For non-healthcare research, this could include:

- Interviews with study participants

- Use of personal data

- Observations of participants

If you are involved in research of this kind, it is important that you are aware of your obligations to the healthcare or non-healthcare research process and the development of research governance. You must also be aware of the College's research misconduct procedures.

Why is it needed?

Research Governance is needed to:

- Safeguard participants in research

- Protect researchers/investigators (by providing a clear framework to work within)

- Enhance ethical and scientific quality

- Minimise risk

- Monitor practice and performance

- Promote good practice and ensure lessons are learned

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Manual for Research Ethics Committees

- > The research governance framework for health and social care

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Editorial board

- Acknowledgements

- List of contributors

- Introduction

- 25 Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects

- 26 The Belmont Report: ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research

- 27 ICH Good Clinical Practice Guideline

- 28 Governance arrangements for NHS research ethics committees

- 29 The research governance framework for health and social care

- 30 EU Clinical Directive 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 April 2001 on the approximation of the laws, regulations, and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the implementation of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use

- 31 European Convention on human rights and biomedicine (ETS 164) and additional protocol on the prohibition of cloning human beings

- 32 Good research practice

- 33 Research: the role and responsibilities of doctors

- 34 Guidelines for company-sponsored safety assessment of marketed medicines (SAMM)

- 35 Guidelines for medical experiments in non-patient human volunteers

- 36 Facilities for non-patient volunteer studies

- 37 Multi-centre research in the NHS – the process of ethical review when there is no local researcher

- 38 Medical devices regulations and research ethics committees

- 39 NHS indemnity – arrangements for clinical negligence claims in the NHS

- 40 Clinical trial compensation guidelines

- 41 Research ethics: guidance for nurses involved in research or any investigative project involving human subjects

- 42 Ethical principles for conducting research with human participants

- 43 Statement of ethical practice

- 44 Human tissue and biological samples for use in research

- 45 Transitional guidelines to facilitate changes in procedures for handling ‘surplus’ and archival material from human biological samples

- 46 Code of practice on the use of fetuses and fetal material in research and treatment (extracts from the Polkinghorne Report)

- 47 Guidance on the supply of fetal tissue for research, diagnosis and therapy

- 48 Guidance on making proposals to conduct gene therapy research on human subjects (seventh annual report – section 1)

- 49 Report on the potential use of gene therapy in utero

- 50 Human fertilisation and embryology authority – code of practice (extracts)

- 51 Guidelines for researchers – patient information sheet and consent form

- 52 ABPI Guidance note – patient information and consents for clinical trials

- 53 The protection and use of patient information (HSG(96)18/LASSL(96)5)

- 54 The Caldicott Report on the review of patient-identifiable information – executive summary December 1997

- 55 Personal information in medical research

- 56 Use and disclosure of medical data – guidance on the Application of the Data Protection Act, 1998, May 2002

- 57 Guidelines for the ethical conduct of medical research involving children

- 58 Clinical investigation of medicinal products in the paediatric population

- 59 Guidelines for researchers and for ethics committees on psychiatric research involving human participants – executive summary

- 60 The ethical conduct of research on the mentally incapacitated

- 61 Volunteering for research into dementia Alzheimer's Society

- 62 Knowledge to care: research and development in hospice and specialist palliative care – executive summary

- 63 NUS guidelines for student participation in medical experiments and guidance for students considering participation in medical drug trials

- 64 Ethical considerations in HIV preventive vaccine research

- 65 2002 international ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects

- 66 1991 international guidelines for ethical review of epidemiological studies

- 67 Operational guidelines for ethics committees that review biomedical research

- 68 Registration of an institutional review board (IRB) or independent ethics committee (IEC)

- 69 International guidelines on bioethics (informal listing of selected international codes, declarations, guidelines etc. on medical ethics/bioethics/health care ethics/human rights aspects of health)

29 - The research governance framework for health and social care

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 08 January 2010

Research governance framework

Research is essential to the successful promotion of health and well-being. Many of the key advances in the last century have depended on research, and health and social care professionals and the public they serve are increasingly looking to research for further improvements.

This country is fortunate to be able to draw upon a wide range of research within the health and social care systems. Most of this is conducted to high scientific and ethical standards. However, recent events have made us all painfully aware that research can cause real distress when things go wrong. The proper governance of research is essential to ensure that the public can have confidence in, and benefit from, health and social care research.

This Research Governance Framework reflects a wide range of discussions with the NHS and all the Department of Health's partners in health and social care research. We have considered carefully the responses to our earlier consultation and the issues raised in meetings with stakeholders.

I am grateful to all who have helped us with this important task. We now need to continue to work together to ensure that this Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care is implemented successfully. In this way, we can provide the public with the reassurance it has the right to expect, and ensure that we can continue to reap the benefits of research.

Access options

Save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- The research governance framework for health and social care

- Edited by Sue Eckstein , King's College London

- Book: Manual for Research Ethics Committees

- Online publication: 08 January 2010

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511550089.031

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

What is research governance?