- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

George Washington

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 25, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

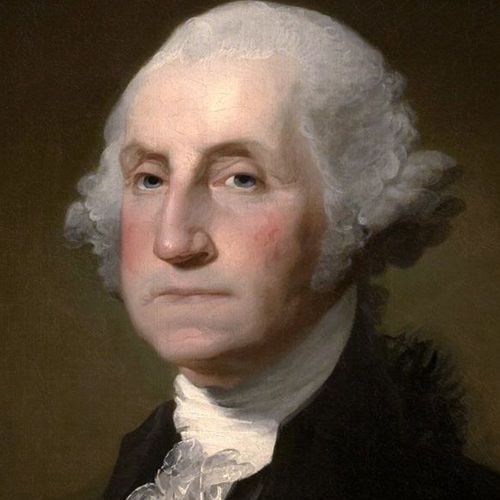

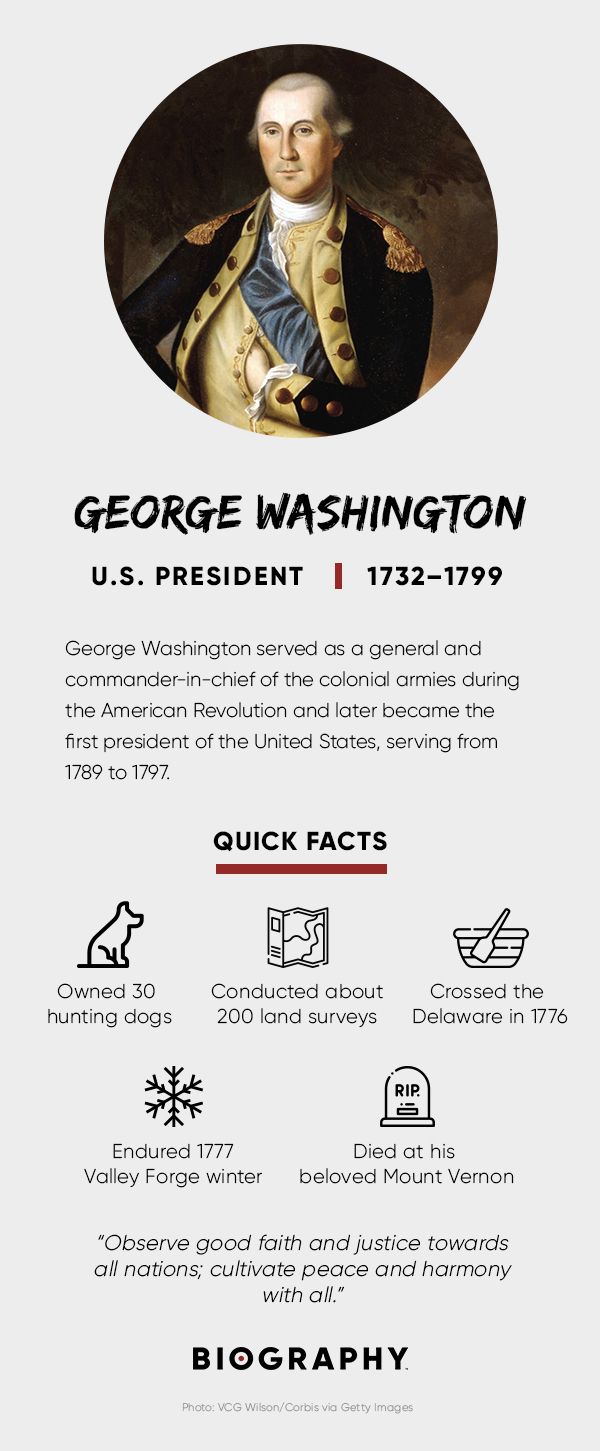

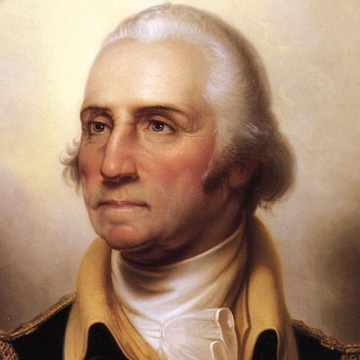

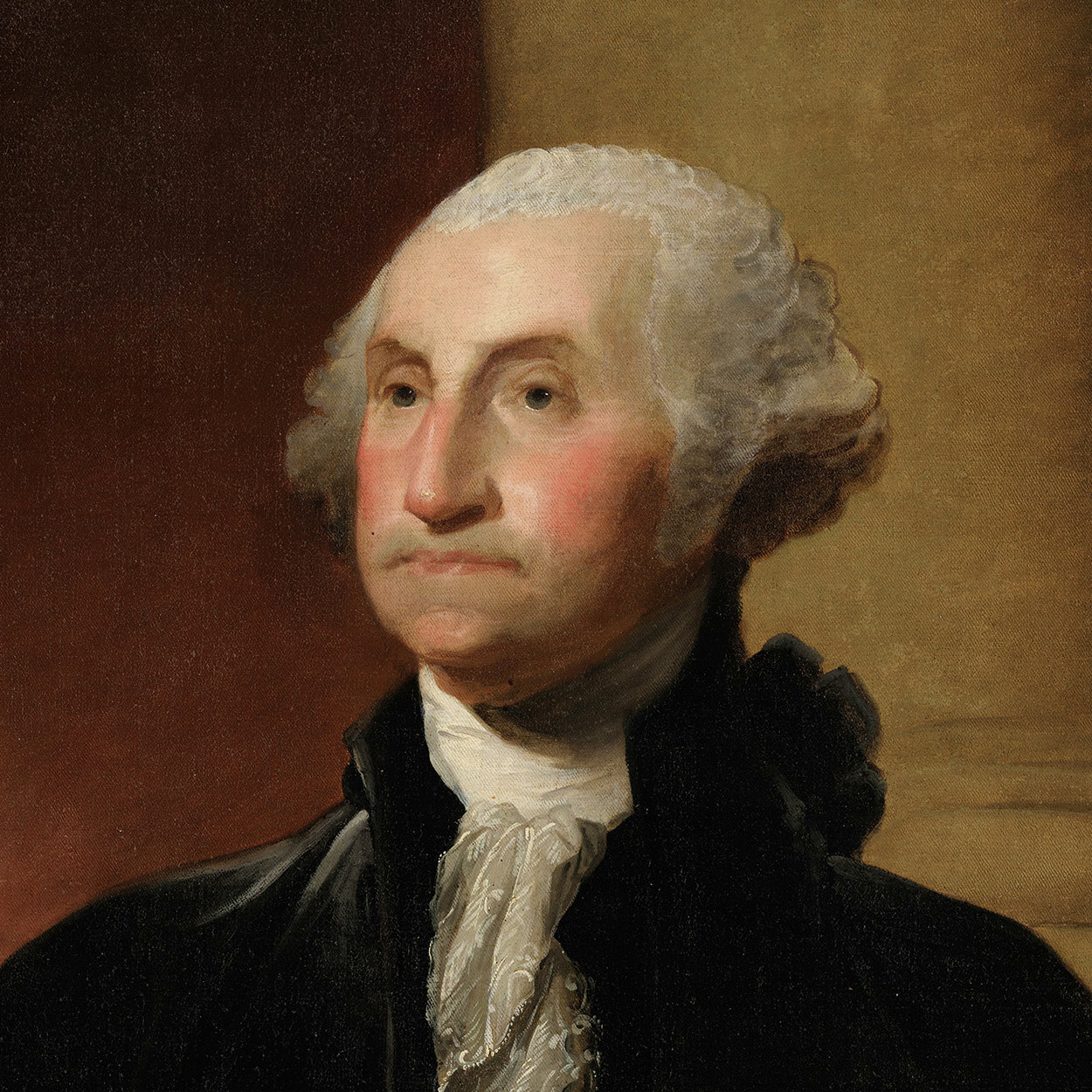

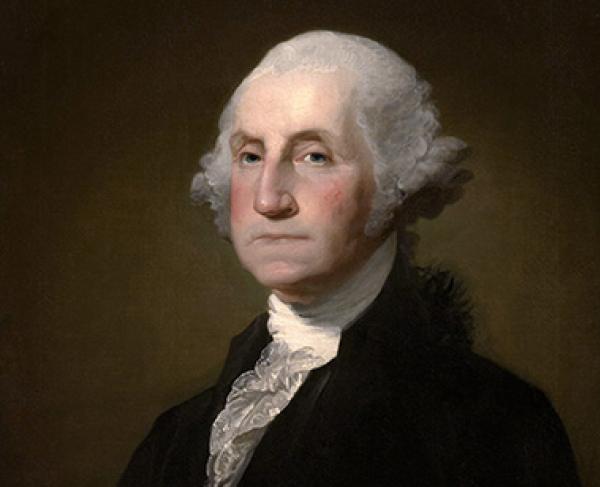

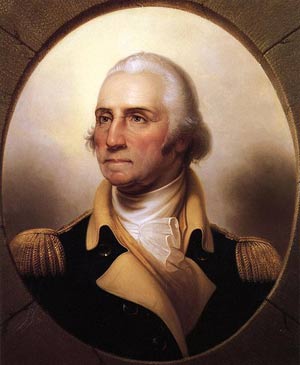

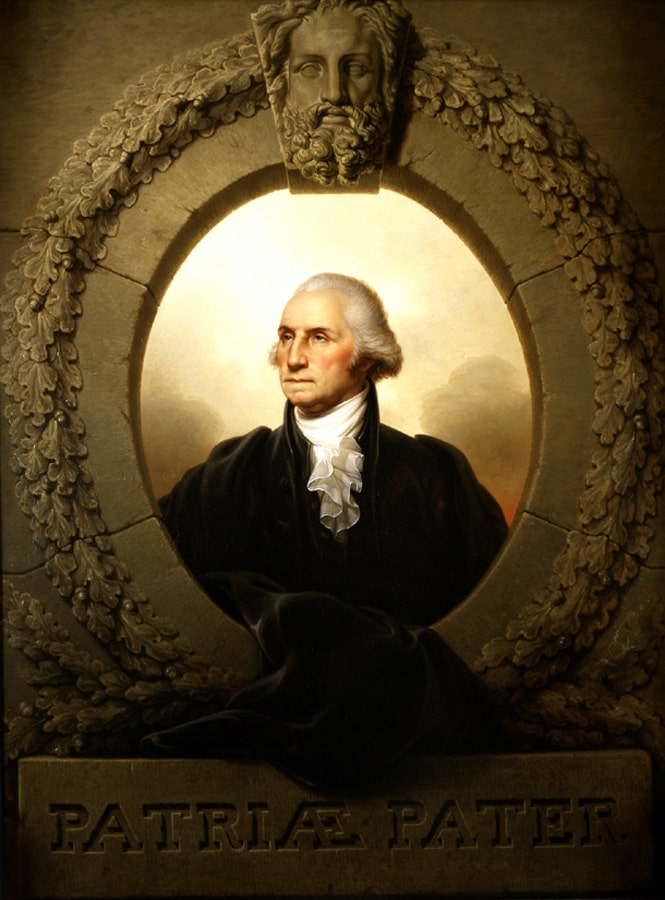

George Washington (1732-99) was commander in chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775-83) and served two terms as the first U.S. president, from 1789 to 1797. The son of a prosperous planter, Washington was raised in colonial Virginia. As a young man, he worked as a surveyor then fought in the French and Indian War (1754-63).

During the American Revolution, he led the colonial forces to victory over the British and became a national hero. In 1787, he was elected president of the convention that wrote the U.S. Constitution. Two years later, Washington became America’s first president. Realizing that the way he handled the job would impact how future presidents approached the position, he handed down a legacy of strength, integrity and national purpose. Less than three years after leaving office, he died at his Virginia plantation, Mount Vernon, at age 67.

George Washington's Early Years

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732 , at his family’s plantation on Pope’s Creek in Westmoreland County, in the British colony of Virginia , to Augustine Washington (1694-1743) and his second wife, Mary Ball Washington (1708-89). George, the eldest of Augustine and Mary Washington’s six children, spent much of his childhood at Ferry Farm, a plantation near Fredericksburg, Virginia. After Washington’s father died when he was 11, it’s likely he helped his mother manage the plantation.

Did you know? At the time of his death in 1799, George Washington owned some 300 enslaved people. However, before his passing, he had become opposed to slavery, and in his will, he ordered that his enslaved workers be freed after his wife's death.

Few details about Washington’s early education are known, although children of prosperous families like his typically were taught at home by private tutors or attended private schools. It’s believed he finished his formal schooling at around age 15.

As a teenager, Washington, who had shown an aptitude for mathematics, became a successful surveyor. His surveying expeditions into the Virginia wilderness earned him enough money to begin acquiring land of his own.

In 1751, Washington made his only trip outside of America, when he traveled to Barbados with his older half-brother Lawrence Washington (1718-52), who was suffering from tuberculosis and hoped the warm climate would help him recuperate. Shortly after their arrival, George contracted smallpox. He survived, although the illness left him with permanent facial scars. In 1752, Lawrence, who had been educated in England and served as Washington’s mentor, died. Washington eventually inherited Lawrence’s estate, Mount Vernon , on the Potomac River near Alexandria, Virginia.

An Officer and Gentleman Farmer

In December 1752, Washington, who had no previous military experience, was made a commander of the Virginia militia. He saw action in the French and Indian War and was eventually put in charge of all of Virginia’s militia forces. By 1759, Washington had resigned his commission, returned to Mount Vernon and was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he served until 1774. In January 1759, he married Martha Dandridge Custis (1731-1802), a wealthy widow with two children. Washington became a devoted stepfather to her children; he and Martha Washington never had any offspring of their own.

In the ensuing years, Washington expanded Mount Vernon from 2,000 acres into an 8,000-acre property with five farms. He grew a variety of crops, including wheat and corn, bred mules and maintained fruit orchards and a successful fishery. He was deeply interested in farming and continually experimented with new crops and methods of land conservation.

George Washington During the American Revolution

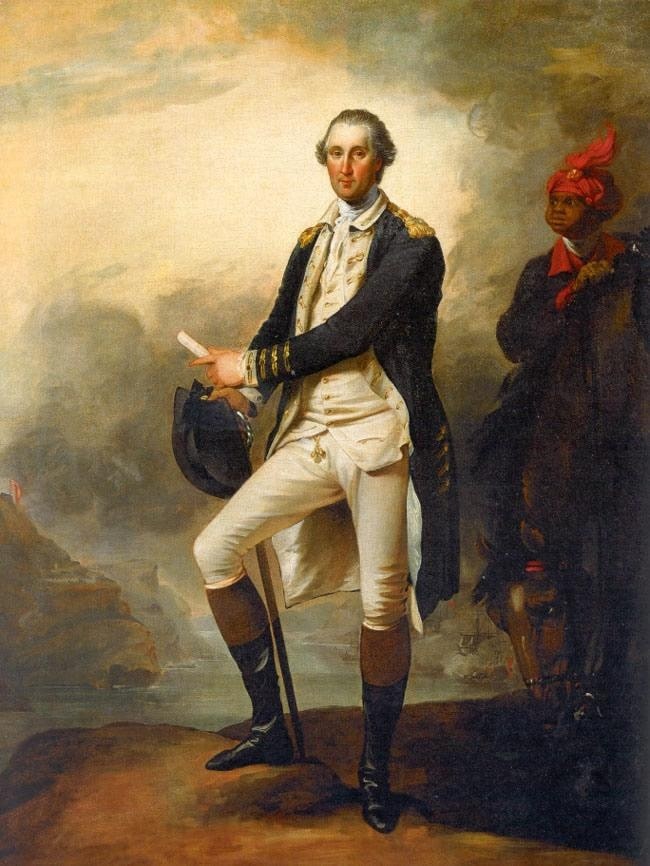

Washington proved to be a better general than military strategist. His strength lay not in his genius on the battlefield but in his ability to keep the struggling colonial army together. His troops were poorly trained and lacked food, ammunition and other supplies (soldiers sometimes even went without shoes in winter). However, Washington was able to give them direction and motivation. His leadership during the winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge was a testament to his power to inspire his men to keep going.

By the late 1760s, Washington had experienced firsthand the effects of rising taxes imposed on American colonists by the British and came to believe that it was in the best interests of the colonists to declare independence from England. Washington served as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774 in Philadelphia. By the time the Second Continental Congress convened a year later, the American Revolution had begun in earnest, and Washington was named commander in chief of the Continental Army.

Over the course of the grueling eight-year war, the colonial forces won few battles but consistently held their own against the British. In October 1781, with the aid of the French (who allied themselves with the colonists over their rivals the British), the Continental forces were able to capture British troops under General Charles Cornwallis (1738-1805) in the Battle of Yorktown . This action effectively ended the Revolutionary War and Washington was declared a national hero.

America’s First President

In 1783, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris between Great Britain and the U.S., Washington, believing he had done his duty, gave up his command of the army and returned to Mount Vernon, intent on resuming his life as a gentleman farmer and family man. However, in 1787, he was asked to attend the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia and head the committee to draft the new constitution . His impressive leadership there convinced the delegates that he was by far the most qualified man to become the nation’s first president.

At first, Washington balked. He wanted to, at last, return to a quiet life at home and leave governing the new nation to others. But public opinion was so strong that eventually he gave in. The first presidential election was held on January 7, 1789, and Washington won handily. John Adams (1735-1826), who received the second-largest number of votes, became the nation’s first vice president. The 57-year-old Washington was inaugurated on April 30, 1789, in New York City. Because Washington, D.C. , America’s future capital city wasn’t yet built, he lived in New York and Philadelphia. While in office, he signed a bill establishing a future, permanent U.S. capital along the Potomac River—the city later named Washington, D.C., in his honor.

George Washington Raised Martha’s Children and Grandchildren as His Own

The 'Father of the Nation' stressed education among his family's younger generations and even offered advice on navigating love.

How 22‑Year‑Old George Washington Inadvertently Sparked a World War

The first U.S. president’s celebrated military career actually started out quite poorly, in the French and Indian War.

11 Little‑Known Facts About George Washington

He's America's first president. The icon we all think we know. But in reality, he was a complicated human being.

George Washington’s Accomplishments

The United States was a small nation when Washington took office, consisting of 11 states and approximately 4 million people, and there was no precedent for how the new president should conduct domestic or foreign business. Mindful that his actions would likely determine how future presidents were expected to govern, Washington worked hard to set an example of fairness, prudence and integrity. In foreign matters, he supported cordial relations with other countries but also favored a position of neutrality in foreign conflicts. Domestically, he nominated the first chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court , John Jay (1745-1829), signed a bill establishing the first national bank, the Bank of the United States , and set up his own presidential cabinet .

His two most prominent cabinet appointees were Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (1755-1804), two men who disagreed strongly on the role of the federal government. Hamilton favored a strong central government and was part of the Federalist Party , while Jefferson favored stronger states’ rights as part of the Democratic-Republican Party, the forerunner to the Democratic Party . Washington believed that divergent views were critical for the health of the new government, but he was distressed at what he saw as an emerging partisanship.

How George Washington Used Spies to Win the American Revolution

Secret agents, invisible ink, ciphers and codes—the gritty and dangerous underworld of the colonial insurgency

5 Myths About George Washington, Debunked

No, he didn’t really chop down that cherry tree, and his teeth weren’t wooden.

George Washington’s Final Years—And Sudden, Agonizing Death

The Founding Father left the presidency a healthy man, but then died from a sudden illness less than three years later.

George Washington’s presidency was marked by a series of firsts. He signed the first United States copyright law, protecting the copyrights of authors. He also signed the first Thanksgiving proclamation, making November 26 a national day of Thanksgiving for the end of the war for American independence and the successful ratification of the Constitution.

During Washington’s presidency, Congress passed the first federal revenue law, a tax on distilled spirits. In July 1794, farmers in Western Pennsylvania rebelled over the so-called “whiskey tax.” Washington called in over 12,000 militiamen to Pennsylvania to dissolve the Whiskey Rebellion in one of the first major tests of the authority of the national government.

Under Washington’s leadership, the states ratified the Bill of Rights , and five new states entered the union: North Carolina (1789), Rhode Island (1790), Vermont (1791), Kentucky (1792) and Tennessee (1796).

In his second term, Washington issued the proclamation of neutrality to avoid entering the 1793 war between Great Britain and France. But when French minister to the United States Edmond Charles Genet—known to history as “Citizen Genet”—toured the United States, he boldly flaunted the proclamation, attempting to set up American ports as French military bases and gain support for his cause in the Western United States. His meddling caused a stir between Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, widening the rift between parties and making consensus-building more difficult.

In 1795, Washington signed the “Treaty of Amity Commerce and Navigation, between His Britannic Majesty; and The United States of America,” or Jay’s Treaty , so-named for John Jay , who had negotiated it with the government of King George III . It helped the U.S. avoid war with Great Britain, but also rankled certain members of Congress back home and was fiercely opposed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison . Internationally, it caused a stir among the French, who believed it violated previous treaties between the United States and France.

Washington’s administration signed two other influential international treaties. Pinckney’s Treaty of 1795, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo, established friendly relations between the United States and Spain, firming up borders between the U.S. and Spanish territories in North America and opening up the Mississippi to American traders. The Treaty of Tripoli, signed the following year, gave American ships access to Mediterranean shipping lanes in exchange for a yearly tribute to the Pasha of Tripoli.

George Washington’s Retirement to Mount Vernon and Death

In 1796, after two terms as president and declining to serve a third term, Washington finally retired. In Washington’s farewell address , he urged the new nation to maintain the highest standards domestically and to keep involvement with foreign powers to a minimum. The address is still read each February in the U.S. Senate to commemorate Washington’s birthday.

Washington returned to Mount Vernon and devoted his attentions to making the plantation as productive as it had been before he became president. More than four decades of public service had aged him, but he was still a commanding figure. In December 1799, he caught a cold after inspecting his properties in the rain. The cold developed into a throat infection and Washington died on the night of December 14, 1799, at the age of 67. He was entombed at Mount Vernon, which in 1960 was designated a national historic landmark.

Washington left one of the most enduring legacies of any American in history. Known as the “Father of His Country,” his face appears on the U.S. dollar bill and quarter, and dozens of U.S. schools, towns and counties, as well as the state of Washington and the nation’s capital city, are named for him.

HISTORY Vault: Washington

Watch HISTORY's mini-series, 'Washington,' which brings to life the man whose name is known to all, but whose epic story is understood by few.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

George Washington

George Washington, a Founding Father of the United States, led the Continental Army to victory in the Revolutionary War and was America’s first president.

(1732-1799)

Who Was George Washington?

George Washington was a Virginia plantation owner who served as a general and commander-in-chief of the colonial armies during the American Revolutionary War, and later became the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797.

Early Life and Family

Washington was born on February 22, 1732, in Westmoreland County, Virginia. He was the eldest of Augustine and Mary’s six children, all of whom survived into adulthood.

The family lived on Pope's Creek in Westmoreland County, Virginia. They were moderately prosperous members of Virginia's "middling class."

Washington could trace his family's presence in North America to his great-grandfather, John Washington, who migrated from England to Virginia. The family held some distinction in England and was granted land by Henry VIII .

But much of the family’s wealth in England was lost under the Puritan government of Oliver Cromwell . In 1657 Washington’s grandfather, Lawrence Washington, migrated to Virginia. Little information is available about the family in North America until Washington’s father, Augustine, was born in 1694.

Augustine Washington was an ambitious man who acquired land and enslaved people, built mills, and grew tobacco. For a time, he had an interest in opening iron mines. He married his first wife, Jane Butler, and they had three children. Jane died in 1729 and Augustine married Mary Ball in 1731.

Mount Vernon

In 1735, Augustine moved the family up the Potomac River to another Washington family home, Little Hunting Creek Plantation — later renamed Mount Vernon .

They moved again in 1738 to Ferry Farm on the Rappahannock River, opposite Fredericksburg, Virginia, where Washington spent much of his youth.

Childhood and Education

Little is known about Washington's childhood, which fostered many of the fables later biographers manufactured to fill in the gap. Among these are the stories that Washington threw a silver dollar across the Potomac and after chopping down his father's prize cherry tree, he openly confessed to the crime.

It is known that from age seven to 15, Washington was home-schooled and studied with the local church sexton and later a schoolmaster in practical math, geography, Latin and the English classics.

But much of the knowledge he would use the rest of his life was through his acquaintance with woodsmen and the plantation foreman. By his early teens, he had mastered growing tobacco, stock raising and surveying.

Washington’s father died when he was 11 and he became the ward of his half-brother, Lawrence, who gave him a good upbringing. Lawrence had inherited the family's Little Hunting Creek Plantation and married Anne Fairfax, the daughter of Colonel William Fairfax, patriarch of the well-to-do Fairfax family. Under her tutelage, Washington was schooled in the finer aspects of colonial culture.

In 1748, when he was 16, Washington traveled with a surveying party plotting land in Virginia’s western territory. The following year, aided by Lord Fairfax, Washington received an appointment as the official surveyor of Culpeper County.

For two years he was very busy surveying the land in Culpeper, Frederick and Augusta counties. The experience made him resourceful and toughened his body and mind. It also piqued his interest in western land holdings, an interest that endured throughout his life with speculative land purchases and a belief that the future of the nation lay in colonizing the West.

In July 1752, Washington's brother, Lawrence, died of tuberculosis, making him the heir apparent of the Washington lands. Lawrence’s only child, Sarah, died two months later and Washington became the head of one of Virginia's most prominent estates, Mount Vernon. He was 20 years old.

Throughout his life, he would hold farming as one of the most honorable professions and he was most proud of Mount Vernon. Washington would gradually increase his landholdings there to about 8,000 acres

Pre-Revolutionary Military Career

In the early 1750s, France and Britain were at peace. However, the French military had begun occupying much of the Ohio Valley, protecting the King's land interests, particularly fur trappers and French settlers. But the borderlands of this area were unclear and prone to dispute between the two countries.

Washington showed early signs of natural leadership and shortly after Lawrence's death, Virginia's Lieutenant Governor, Robert Dinwiddie, appointed Washington adjutant with a rank of major in the Virginia militia.

French and Indian War

On October 31, 1753, Dinwiddie sent Washington to Fort LeBoeuf, at what is now Waterford, Pennsylvania, to warn the French to remove themselves from land claimed by Britain. The French politely refused and Washington made a hasty ride back to Williamsburg, Virginia's colonial capital.

Dinwiddie sent Washington back with troops and they set up a post at Great Meadows. Washington's small force attacked a French post at Fort Duquesne, killing the commander, Coulon de Jumonville, and nine others and taking the rest prisoners. The French and Indian War had begun.

The French counterattacked and drove Washington and his men back to his post at Great Meadows (later named "Fort Necessity.") After a full day siege, Washington surrendered and was soon released and returned to Williamsburg, promising not to build another fort on the Ohio River.

Though a little embarrassed at being captured, he was grateful to receive the thanks from the House of Burgesses and see his name mentioned in the London gazettes.

Washington was given the honorary rank of colonel and joined British General Edward Braddock's army in Virginia in 1755. The British had devised a plan for a three-prong assault on French forces attacking Fort Duquesne, Fort Niagara and Crown Point.

During the encounter, the French and their Indian allies ambushed Braddock, who was mortally wounded. Washington escaped injury with four bullet holes in his cloak and two horses shot out from under him. Though he fought bravely, he could do little to turn back the rout and led the defeated army back to safety.

Commander of Virginia Troops

In August 1755, Washington was made commander of all Virginia troops at age 23. He was sent to the frontier to patrol and protect nearly 400 miles of border with some 700 ill-disciplined colonial troops and a Virginia colonial legislature unwilling to support him.

It was a frustrating assignment. His health failed in the closing months of 1757 and he was sent home with dysentery.

In 1758, Washington returned to duty on another expedition to capture Fort Duquesne. A friendly-fire incident took place, killing 14 and wounding 26 of Washington's men. However, the British were able to score a major victory, capturing Fort Duquesne and control of the Ohio Valley.

Washington retired from his Virginia regiment in December 1758. His experience during the war was generally frustrating, with key decisions made slowly, poor support from the colonial legislature and poorly trained recruits.

Washington applied for a commission with the British army but was turned down. In 1758, he resigned his commission and returned to Mount Vernon disillusioned. The same year, he entered politics and was elected to Virginia's House of Burgesses.

Martha Washington

A month after leaving the army, Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis, a widow, who was only a few months older than he. Martha brought to the marriage a considerable fortune: an 18,000-acre estate, from which Washington personally acquired 6,000 acres.

With this and land he was granted for his military service, Washington became one of the more wealthy landowners in Virginia. The marriage also brought Martha's two young children, John (Jacky) and Martha (Patsy), ages six and four, respectively.

Washington lavished great affection on both of them, and was heartbroken when Patsy died just before the Revolution. Jacky died during the Revolution, and Washington adopted two of his children.

Enslaved People

During his retirement from the Virginia militia until the start of the Revolution, Washington devoted himself to the care and development of his land holdings, attending the rotation of crops, managing livestock and keeping up with the latest scientific advances.

By the 1790s, Washington kept over 300 enslaved people at Mount Vernon. He was said to dislike the institution of slavery , but accepted the fact that it was legal.

Washington, in his will, made his displeasure with slavery known, as he ordered that all his enslaved people be granted their freedom upon the death of his wife Martha. (This act of generosity, however, applied to fewer than half of Mount Vernon's enslaved people: Those enslaved people owned by the Custis family were given to Martha’s grandchildren after her death.)

Washington loved the landed gentry's life of horseback riding, fox hunts, fishing and cotillions. He worked six days a week, often taking off his coat and performing manual labor with his workers. He was an innovative and responsible landowner, breeding cattle and horses and tending to his fruit orchards.

Much has been made of the fact that Washington used false teeth or dentures for most of his adult life. Indeed, Washington's correspondence to friends and family makes frequent references to aching teeth, inflamed gums and various dental woes.

Washington had one tooth pulled when he was just 24 years old, and by the time of his inauguration in 1789 he had just one natural tooth left. But his false teeth weren't made of wood, as some legends suggest.

Instead, Washington's false teeth were fashioned from human teeth — including teeth from enslaved people and his own pulled teeth — ivory, animal teeth and assorted metals.

Washington's dental problems, according to some historians, probably impacted the shape of his face and may have contributed to his quiet, somber demeanor: During the Constitutional Convention, Washington addressed the gathered dignitaries only once.

American Revolution

Though the British Proclamation Act of 1763 — prohibiting settlement beyond the Alleghenies — irritated Washington and he opposed the Stamp Act of 1765, he did not take a leading role in the growing colonial resistance against the British until the widespread protest of the Townshend Acts in 1767.

His letters of this period indicate he was totally opposed to the colonies declaring independence. However, by 1767, he wasn't opposed to resisting what he believed were fundamental violations by the Crown of the rights of Englishmen.

In 1769, Washington introduced a resolution to the House of Burgesses calling for Virginia to boycott British goods until the Acts were repealed.

After the passage of the Coercive Acts in 1774, Washington chaired a meeting in which the Fairfax Resolves were adopted, calling for the convening of the Continental Congress and the use of armed resistance as a last resort. He was selected as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in March 1775.

Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army

After the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, the political dispute between Great Britain and her North American colonies escalated into an armed conflict. In May, Washington traveled to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia dressed in a military uniform, indicating that he was prepared for war.

On June 15th, he was appointed Major General and Commander-in-Chief of the colonial forces against Great Britain. As was his custom, he did not seek out the office of commander, but he faced no serious competition.

Washington was the best choice for a number of reasons: he had the prestige, military experience and charisma for the job and he had been advising Congress for months.

Another factor was political: The Revolution had started in New England and at the time, they were the only colonies that had directly felt the brunt of British tyranny. Virginia was the largest British colony and New England needed Southern colonial support.

Political considerations and force of personality aside, Washington was not necessarily qualified to wage war on the world's most powerful nation. Washington's training and experience were primarily in frontier warfare involving small numbers of soldiers. He wasn't trained in the open-field style of battle practiced by the commanding British generals.

He also had no practical experience maneuvering large formations of infantry, commanding cavalry or artillery, or maintaining the flow of supplies for thousands of men in the field. But he was courageous and determined and smart enough to keep one step ahead of the enemy.

Washington and his small army did taste victory early in March 1776 by placing artillery above Boston, on Dorchester Heights, forcing the British to withdraw. Washington then moved his troops into New York City. But in June, a new British commander, Sir William Howe , arrived in the Colonies with the largest expeditionary force Britain had ever deployed to date.

Crossing the Delaware

In August 1776, the British army launched an attack and quickly took New York City in the largest battle of the war. Washington's army was routed and suffered the surrender of 2,800 men.

He ordered the remains of his army to retreat into Pennsylvania across the Delaware River. Confident the war would be over in a few months, General Howe wintered his troops at Trenton and Princeton, leaving Washington free to attack at the time and place of his choosing.

On Christmas night, 1776, Washington and his men returned across the Delaware River and attacked unsuspecting Hessian mercenaries at Trenton, forcing their surrender. A few days later, evading a force that had been sent to destroy his army, Washington attacked the British again, this time at Princeton, dealing them a humiliating loss.

Victories and Losses

General Howe's strategy was to capture colonial cities and stop the rebellion at key economic and political centers. He never abandoned the belief that once the Americans were deprived of their major cities, the rebellion would wither.

In the summer of 1777, he mounted an offensive against Philadelphia. Washington moved in his army to defend the city but was defeated at the Battle of Brandywine . Philadelphia fell two weeks later.

In the late summer of 1777, the British army sent a major force, under the command of John Burgoyne, south from Quebec to Saratoga, New York, to split the rebellion between New England and the southern colonies. But the strategy backfired, as Burgoyne became trapped by the American armies led by Horatio Gates and Benedict Arnold at the Battle of Saratoga .

Without support from Howe, who couldn't reach him in time, Burgoyne was forced to surrender his entire 6,200 man army. The victory was a major turning point in the war as it encouraged France to openly ally itself with the American cause for independence.

Through all of this, Washington discovered an important lesson: The political nature of war was just as important as the military one. Washington began to understand that military victories were as important as keeping the resistance alive.

Americans began to believe that they could meet their objective of independence without defeating the British army. Meanwhile, British General Howe clung to the strategy of capturing colonial cities in hopes of smothering the rebellion.

Howe didn't realize that capturing cities like Philadelphia and New York would not unseat colonial power. The Congress would just pack up and meet elsewhere.

Valley Forge

The darkest time for Washington and the Continental Army was during the winter of 1777 at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. The 11,000-man force went into winter quarters and over the next six months suffered thousands of deaths, mostly from disease. But the army emerged from the winter still intact and in relatively good order.

Realizing their strategy of capturing colonial cities had failed, the British command replaced General Howe with Sir Henry Clinton. The British army evacuated Philadelphia to return to New York City. Washington and his men delivered several quick blows to the moving army, attacking the British flank near Monmouth Courthouse. Though a tactical standoff, the encounter proved Washington's army capable of open field battle.

For the remainder of the war, Washington was content to keep the British confined to New York, although he never totally abandoned the idea of retaking the city. The alliance with France had brought a large French army and a navy fleet.

Washington and his French counterparts decided to let Clinton be and attack British General Charles Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia. Facing the combined French and Colonial armies and the French fleet of 29 warships at his back, Cornwallis held out as long as he could, but on October 19, 1781, he surrendered his forces.

Revolutionary War Victory

Washington had no way of knowing the Yorktown victory would bring the war to a close.

The British still had 26,000 troops occupying New York City, Charleston and Savannah, plus a large fleet of warships in the Colonies. By 1782, the French army and navy had departed, the Continental treasury was depleted, and most of his soldiers hadn’t been paid for several years.

A near-mutiny was avoided when Washington convinced Congress to grant a five-year bonus for soldiers in March 1783. By November of that year, the British had evacuated New York City and other cities and the war was essentially over.

The Americans had won their independence. Washington formally bade his troops farewell and on December 23, 1783, he resigned his commission as commander-in-chief of the army and returned to Mount Vernon.

For four years, Washington attempted to fulfill his dream of resuming life as a gentleman farmer and to give his much-neglected Mount Vernon plantation the care and attention it deserved.

The war had been costly to the Washington family with lands neglected, no exports of goods, and the depreciation of paper money. But Washington was able to repair his fortunes with a generous land grant from Congress for his military service and become profitable once again.

Constitutional Convention

In 1787, Washington was again called to the duty of his country. Since independence, the young republic had been struggling under the Articles of Confederation , a structure of government that centered power with the states.

But the states were not unified. They fought among themselves over boundaries and navigation rights and refused to contribute to paying off the nation's war debt. In some instances, state legislatures imposed tyrannical tax policies on their own citizens.

Washington was intensely dismayed at the state of affairs, but only slowly came to the realization that something should be done about it. Perhaps he wasn't sure the time was right so soon after the Revolution to be making major adjustments to the democratic experiment. Or perhaps because he hoped he would not be called upon to serve, he remained noncommittal.

But when Shays' Rebellion erupted in Massachusetts, Washington knew something needed to be done to improve the nation’s government. In 1786, Congress approved a convention to be held in Philadelphia to amend the Articles of Confederation.

At the Constitutional Convention , Washington was unanimously chosen as president. Washington, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton had come to the conclusion that it wasn't amendments that were needed, but a new constitution that would give the national government more authority.

In the end, the Convention produced a plan for government that not only would address the country's current problems, but would endure through time. After the convention adjourned, Washington's reputation and support for the new government were indispensable to the ratification of the new U.S. Constitution .

The opposition was strident, if not organized, with many of America's leading political figures — including Patrick Henry and Sam Adams — condemning the proposed government as a grab for power. Even in Washington's native Virginia, the Constitution was ratified by only one vote.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S GEORGE WASHINGTON FACT CARD

George Washington: Presidency

Still hoping to retire to his beloved Mount Vernon, Washington was once again called upon to serve this country.

During the presidential election of 1789, he received a vote from every elector to the Electoral College, the only president in American history to be elected by unanimous approval. He took the oath of office at Federal Hall in New York City, the capital of the United States at the time.

As the first president, Washington was astutely aware that his presidency would set a precedent for all that would follow. He carefully attended to the responsibilities and duties of his office, remaining vigilant to not emulate any European royal court. To that end, he preferred the title "Mr. President," instead of more imposing names that were suggested.

At first he declined the $25,000 salary Congress offered the office of the presidency, for he was already wealthy and wanted to protect his image as a selfless public servant. However, Congress persuaded him to accept the compensation to avoid giving the impression that only wealthy men could serve as president.

Washington proved to be an able administrator. He surrounded himself with some of the most capable people in the country, appointing Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury and Thomas Jefferson as Secretary of State. He delegated authority wisely and consulted regularly with his cabinet listening to their advice before making a decision.

Washington established broad-ranging presidential authority, but always with the highest integrity, exercising power with restraint and honesty. In doing so, he set a standard rarely met by his successors, but one that established an ideal by which all are judged.

READ MORE: How George Washington’s Personal and Physical Characteristics Helped Him Win the Presidency

Accomplishments

During his first term, Washington adopted a series of measures proposed by Treasury Secretary Hamilton to reduce the nation's debt and place its finances on sound footing.

His administration also established several peace treaties with Native American tribes and approved a bill establishing the nation's capital in a permanent district along the Potomac River.

Whiskey Rebellion

Then, in 1791, Washington signed a bill authorizing Congress to place a tax on distilled spirits, which stirred protests in rural areas of Pennsylvania.

Quickly, the protests turned into a full-scale defiance of federal law known as the Whiskey Rebellion . Washington invoked the Militia Act of 1792, summoning local militias from several states to put down the rebellion.

Washington personally took command, marching the troops into the areas of rebellion and demonstrating that the federal government would use force, when necessary, to enforce the law. This was also the only time a sitting U.S. president has led troops into battle.

In foreign affairs, Washington took a cautious approach, realizing that the weak young nation could not succumb to Europe's political intrigues. In 1793, France and Great Britain were once again at war.

At the urging of Hamilton, Washington disregarded the U.S. alliance with France and pursued a course of neutrality. In 1794, he sent John Jay to Britain to negotiate a treaty (known as the "Jay Treaty") to secure a peace with Britain and clear up some issues held over from the Revolutionary War.

The action infuriated Jefferson, who supported the French and felt that the U.S. needed to honor its treaty obligations. Washington was able to mobilize public support for the treaty, which proved decisive in securing ratification in the Senate.

Though controversial, the treaty proved beneficial to the United States by removing British forts along the western frontier, establishing a clear boundary between Canada and the United States, and most importantly, delaying a war with Britain and providing over a decade of prosperous trade and development the fledgling country so desperately needed.

Political Parties

All through his two terms as president, Washington was dismayed at the growing partisanship within the government and the nation. The power bestowed on the federal government by the Constitution made for important decisions, and people joined together to influence those decisions. The formation of political parties at first were influenced more by personality than by issues.

As Treasury secretary, Hamilton pushed for a strong national government and an economy built in industry. Secretary of State Jefferson desired to keep government small and center power more at the local level, where citizens' freedom could be better protected. He envisioned an economy based on farming.

Those who followed Hamilton's vision took the name Federalists and people who opposed those ideas and tended to lean toward Jefferson’s view began calling themselves Democratic-Republicans. Washington despised political partisanship, believing that ideological differences should never become institutionalized. He strongly felt that political leaders should be free to debate important issues without being bound by party loyalty.

However, Washington could do little to slow the development of political parties. The ideals promoted by Hamilton and Jefferson produced a two-party system that proved remarkably durable. These opposing viewpoints represented a continuation of the debate over the proper role of government, a debate that began with the conception of the Constitution and continues today.

Washington's administration was not without its critics who questioned what they saw as extravagant conventions in the office of the president. During his two terms, Washington rented the best houses available and was driven in a coach drawn by four horses, with outriders and lackeys in rich uniforms.

After being overwhelmed by callers, he announced that except for the scheduled weekly reception open to all, he would only see people by appointment. Washington entertained lavishly, but in private dinners and receptions at invitation only. He was, by some, accused of conducting himself like a king.

However, ever mindful his presidency would set the precedent for those to follow, he was careful to avoid the trappings of a monarchy. At public ceremonies, he did not appear in a military uniform or the monarchical robes. Instead, he dressed in a black velvet suit with gold buckles and powdered hair, as was the common custom. His reserved manner was more due to inherent reticence than any excessive sense of dignity.

Desiring to return to Mount Vernon and his farming, and feeling the decline of his physical powers with age, Washington refused to yield to the pressures to serve a third term, even though he would probably not have faced any opposition.

By doing this, he was again mindful of the precedent of being the "first president," and chose to establish a peaceful transition of government.

Farewell Address

In the last months of his presidency, Washington felt he needed to give his country one last measure of himself. With the help of Hamilton, he composed his Farewell Address to the American people, which urged his fellow citizens to cherish the Union and avoid partisanship and permanent foreign alliances.

In March 1797, he turned over the government to John Adams and returned to Mount Vernon, determined to live his last years as a simple gentleman farmer. His last official act was to pardon the participants in the Whiskey Rebellion.

Upon returning to Mount Vernon in the spring of 1797, Washington felt a reflective sense of relief and accomplishment. He had left the government in capable hands, at peace, its debts well-managed, and set on a course of prosperity.

He devoted much of his time to tending the farm's operations and management. Although he was perceived to be wealthy, his land holdings were only marginally profitable.

On a cold December day in 1799, Washington spent much of it inspecting the farm on horseback in a driving snowstorm. When he returned home, he hastily ate his supper in his wet clothes and then went to bed.

The next morning, on December 13, he awoke with a severe sore throat and became increasingly hoarse. He retired early, but awoke around 3 a.m. and told Martha that he felt very sick. The illness progressed until he died late in the evening of December 14, 1799.

The news of Washington's death at age 67 spread throughout the country, plunging the nation into a deep mourning. Many towns and cities held mock funerals and presented hundreds of eulogies to honor their fallen hero. When the news of this death reached Europe, the British fleet paid tribute to his memory, and Napoleon ordered ten days of mourning.

Washington could have been a king. Instead, he chose to be a citizen. He set many precedents for the national government and the presidency: The two-term limit in office, only broken once by Franklin D. Roosevelt , was later ensconced in the Constitution's 22nd Amendment.

He crystallized the power of the presidency as a part of the government’s three branches of government , able to exercise authority when necessary, but also accept the checks and balances of power inherent in the system.

He was not only considered a military and revolutionary hero, but a man of great personal integrity, with a deep sense of duty, honor and patriotism. For over 200 years, Washington has been acclaimed as indispensable to the success of the Revolution and the birth of the nation.

But his most important legacy may be that he insisted he was dispensable, asserting that the cause of liberty was larger than any single individual.

Watch "George Washington: Founding Father" on HISTORY Vault

QUICK FACTS

- Name: George Washington

- Birth Year: 1732

- Birth date: February 22, 1732

- Birth State: Virginia

- Birth City: Westmoreland County

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: George Washington, a Founding Father of the United States, led the Continental Army to victory in the Revolutionary War and was America’s first president.

- U.S. Politics

- Astrological Sign: Pisces

- Death Year: 1799

- Death date: December 14, 1799

- Death State: Virginia

- Death City: Mount Vernon

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: George Washington Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/george-washington

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: September 11, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- Observe good faith and justice towards all nations; cultivate peace and harmony with all.

- When we assumed the soldier, we did not lay aside the citizen.

- Be courteous to all, but intimate with few.

- [T]he preservation of the sacred fire of liberty, and the destiny of the republican model of government, are justly considered as deeply, perhaps as finally staked, on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.

- We should never despair, our situation before has been unpromising and has changed for the better, so I trust, it will again. If new difficulties arise, we must only put forth new exertions and proportion our efforts to the exigency of the times.

- There can be no greater error than to expect or calculate upon real favors from nation to nation.

- [M]y movements to the chair of government will be accompanied by feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution.

- True friendship is a plant of slow growth, and must undergo and withstand the shocks of adversity before it is entitled to the appellation.

- Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.

- I heard the bullets whistle, and, believe me, there is something charming in the sound.

- Discipline is the soul of an army. It makes small numbers formidable; procures success to the weak, and esteem to all.

- The basis of our political Systems is the right of the people to make and to alter their Constitutions of Government. But the Constitution which at any time exists, 'till changed by an explicit and authentic act of the whole People, is sacredly obligatory upon all.

- I hold the maxim no less applicable to public than to private affairs, that honesty is the best policy.

- The bosom of America is open to receive not only the opulent and respectable stranger, but the oppressed and persecuted of all nations and religions.

U.S. Presidents

Ronald Reagan

How Ronald Reagan Went from Movies to Politics

Teddy Roosevelt’s Stolen Watch Recovered by FBI

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Thomas Jefferson

A Car Accident Killed Joe Biden’s Wife and Baby

These Are the Major 2024 Presidential Candidates

Oppenheimer and Truman Met Once. It Went Badly.

Who Killed JFK? You Won’t Believe Us Anyway

John F. Kennedy

Jimmy Carter

Inside Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter’s 77-Year Love

George Washington

Server costs fundraiser 2024.

George Washington (1732-1799) was an American military officer and statesman who led the Continental Army to victory during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and served as the first president of the United States (1789-1797). Often regarded as the 'Father of His Country', Washington remains one of the most revered and iconic figures in US history.

George Washington was born at 10 am on 22 February 1732 at Pope's Creek plantation in Westmoreland County, Virginia. He was the first of six children born to Augustine Washington, a wealthy Virginian landowner, and his second wife Mary Ball Washington; George also had four older half-siblings from his father's first marriage. Little is known about George's childhood. His early years were mostly spent on the family property of Ferry Farm on the Rappahannock River, and he likely attended school in Fredericksburg, Virginia, where he excelled in the subjects of geometry, trigonometry, and mapmaking. When his father suddenly died in 1743, 11-year-old George inherited Ferry Farm as well as ten enslaved people. Too young to fend for himself, he went to live with his eldest half-brother, Lawrence Washington (b.1718), at Mount Vernon. George idolized Lawrence, who he came to regard as both a father figure and a best friend.

George's aptitude for mathematics led him to consider a career as a land surveyor, a respectable path to wealth and social advancement. In 1748, at the age of 16, he embarked on his first expedition into the Shenandoah Valley to survey the property of his influential neighbor, Thomas Fairfax. The next year, he earned his surveyor's license and, through Fairfax's patronage, was appointed surveyor for Culpeper County. Over the next three years, Washington completed 200 surveying expeditions and measured a total of 60,000 acres along Virginia's western frontier. But just as George's career was taking off, Lawrence came down with tuberculosis. In November 1751, he went to the Caribbean island of Barbados in the hopes that the tropical air would improve his condition. George accompanied him, and contracted a painful case of smallpox during his brief stay on the island. George soon recovered but Lawrence was not so lucky, as he died shortly after returning to Virginia in 1752. After his brother's death , George started leasing Mount Vernon from Lawrence's widow and became the legal owner of the property after her own death in 1761.

In 1753, George Washington reached the age of maturity, and was eager to find a way to make a name for himself. He would soon have an opportunity. The French had begun to construct forts on the forks of the Ohio River, fertile territory that had been claimed by Virginia. In November, Washington was sent as an envoy to demand that the French vacate the Ohio Country at once. On his journey into the west, he was joined by Christopher Gist, an experienced frontiersman and guide, and Tanacharison, a Mingo chieftain called the 'Half-King' by Virginians. It was Tanacharison who gave Washington the Seneca name of ' Conotocaurius ' or 'Devourer of Villages', in reference to Washington's great-grandfather, who had helped expel Native Americans from their lands in Virginia. The small party reached the French Fort LeBoeuf during a snowstorm; although they were received cordially by the fort's commander, Washington's demands were firmly rebuffed. Washington then embarked on his trek back to Virginia which included several perilous episodes. While crossing the icy Alleghany River in a raft, Washington fell overboard, and likely would have drowned had Gist not pulled him from the water.

French and Indian War

In April 1754, Washington was commissioned as a lieutenant colonel in the newly formed Virginia Regiment and was sent back to the Ohio Country, this time with a company of 159 men, to again demand that the French leave. He set up camp in a grassy field called Great Meadows, where he was informed by one of Tanacharison's scouts that a party of French soldiers was encamped nearby. Early in the morning of 28 May 1754, Washington and Tanacharison ambushed the French camp; in the short skirmish that followed, several French troops were killed, including their commander, Joseph Coulon de Jumonville. Washington immediately withdrew back to Great Meadows, where his men hastily constructed Fort Necessity. But when the French attacked on 3 July, the fort was unable to hold out; after eight hours of fighting, Washington agreed to surrender on the condition that his surviving men could return to Virginia. The incident greatly heightened tensions between Britain and France, helping to spark a global conflict, the Seven Years' War (1756-1763).

The next year, Brigadier General Edward Braddock landed in Virginia with two regiments of British regulars, tasked with capturing Fort Duquesne and forcing the French from the Ohio Country once and for all. When Braddock's Expedition set out in May 1755, Washington accompanied it as one of Braddock's aides-de-camp , but was forced to remain behind for much of the campaign on account of his dysentery. He was, however, with the army when it was ambushed by the French and their Indigenous allies on 9 July at the Battle of the Monongahela. Despite having two horses killed from under him, Washington managed to rally the panicked British army and help lead the retreat. Over 800 British and provincial soldiers had become casualties in the ambush including Braddock, who was mortally wounded. Over the next two years, Washington, now a full colonel in command of the Virginia Regiment, oversaw the defense of the colony's western frontier. In 1758, he joined the Forbes Expedition which succeeded in capturing Fort Duquesne without firing a shot. This campaign helped turn the tide of the French and Indian War, which ultimately resulted in a British victory in 1763.

Marriage & Plantation Life

Frustrated that his exploits had not won him a commission in the regular British army, Washington resigned from the Virginia Regiment and returned to Mount Vernon. He won election to the House of Burgesses in 1758 and, the following January, married the wealthy widow Martha Dandridge Custis. The marriage gave Washington control over the 18,000-acre Custis estate as well as 84 enslaved people, making him one of the most influential landowners in Virginia. He and Martha never had any children together; indeed, some scholars have speculated that Washington's 1751 bout with smallpox rendered him sterile. Instead, Washington treated Martha's children from her first marriage, John Parke Custis and Martha 'Patsy' Parke Custis, as if they were his own. Sadly, he would outlive them both; Patsy died of an epileptic seizure in 1773 at the age of 17, while John died of 'camp fever' in 1781 while serving at Yorktown. After their deaths, Washington found joy in raising John's children.

Washington spent the 1760s tending to his beloved home of Mount Vernon, where wheat and tobacco were grown and harvested by hundreds of slaves; over the course of Washington's lifetime, 577 enslaved people lived and worked at Mount Vernon. Although Washington was not considered a cruel slaveowner by the standards of the day, his slaves often had to subsist on insufficient rations, live in cramped, one-room dwellings, and exist perpetually under the supervision of Washington's overseers; Washington also had no qualms about whipping or selling enslaved people who tried to run away. Washington's views on the institution of slavery evolved over time and, by the advent of the Revolution, he found the practice to be abhorrent. Nevertheless, he did little to work toward the abolition of slavery and, indeed, continued to rent and purchase slaves until his death.

As Washington concerned himself with his life at Mount Vernon, tensions between Britain and the Thirteen Colonies were escalating. Disagreement over the colonists' rights and liberties – expressed over the constitutional authority of Parliament to issue tax policies like the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts , policies which the colonists had never consented to – led to riots and incidents of violence like the Boston Massacre (1770). Washington increasingly sided against Parliament; his status as one of Virginia's leading citizens automatically made him a leader in the colony's Whig, or Patriot, movement. In 1774, he attended the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia and helped train Virginia militias for potential conflict with British soldiers. When, on 19 April 1775, blood was spilled at the Battles of Lexington and Concord , Washington was prepared to fight for his homeland.

Commander-in-Chief

On 14 June 1775, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Continental Army and nominated Washington as its commander-in-chief; their decision was informed both by Washington's military experience and because they felt the southern colonies were more likely to rally behind one of their own. On 2 July, Washington rode into the army headquarters of Cambridge, Massachusetts, where the Continental Army was carrying out the Siege of Boston . Washington was dismayed to find that his new army was little more than a jumble of undisciplined colonial militias, and immediately went to work drilling the troops and enforcing strict discipline. In early 1776, he finally found an opportunity to win the siege, when Colonel Henry Knox arrived with heavy artillery captured from Fort Ticonderoga, which Washington positioned on the Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston. Rather than face an artillery bombardment, the British evacuated the city by sea on 17 March, and Boston fell back into American hands.

Washington then marched his army to New York City, which he correctly predicted would be the next target of the British. In July, as he was preparing the city's defenses, he received word that the Congress had declared the independence of the United States; on 9 July, Washington assembled his army and read the Declaration of Independence aloud to his cheering soldiers. Meanwhile, a British army of 32,000 men was gathering on nearby Staten Island. The British finally struck at the Battle of Long Island (27 August 1776), pushing Washington's men off their fortifications atop the Heights of Guan and inflicting over 2,000 American casualties. The British could have defeated the Continental Army there and then, had Washington not been able to successfully evacuate his troops from Long Island during the stormy night of 29-30 August. He was, however, forced to abandon New York City, which was occupied by the British on 15 September.

Over the next several weeks, Washington was chased through lower New York and New Jersey, fighting desperate actions at Harlem Heights (16 September), White Plains (28 October), and Fort Washington (16 November) as his army was whittled away by attrition. By mid-December, his army had been reduced to barely 3,000 men, and many assumed it would not survive the winter. But Washington had come to believe that the success of the entire Revolution depended on the survival of his army and was therefore determined to preserve it at all costs. This led him to adopt a Fabian strategy, whereby he would avoid pitched battles whenever possible, preferring to wear down the enemy with minor raids and scorched earth tactics. This did not mean Washington was a timid commander, however, as he constantly looked for opportunities to strike at the enemy when their guard was down. In one such instance, Washington crossed the icy Delaware River on the night of 25 December 1776, surprising and defeating a Hessian garrison at the Battle of Trenton the next morning. This and his follow up victory at the Battle of Princeton (3 January 1777) galvanized renewed support for the Revolution.

The next year, Washington marched into Pennsylvania to defend the US capital of Philadelphia. He lost two hard-fought actions at the Battle of Brandywine (11 September) and Battle of Germantown (4 October) and was unable to prevent the British from occupying Philadelphia in late September. But the loss of the capital did not have the adverse effect on American morale that the British had hoped for. In December, Washington moved his army to Valley Forge , where he spent the winter implementing vital supply reforms, inoculating his soldiers against smallpox, and fending off a political threat to his leadership known as the Conway Cabal . During this time, officers like Baron Friedrich von Steuben retrained the Continental Army into a more disciplined and effective fighting force. When the Continental Army marched out of Valley Forge in June 1778, it was eager to put its new skills to the test – at the Battle of Monmouth (28 June), the Continentals fought the British to a standstill in scorching summer heat. That same year, France entered the war as a US ally.

Washington then moved his army outside New York City, maintaining that approximate position for the next two years as the focus of the war shifted to the South. Washington dispatched his trusted general Nathanael Greene to lead the southern army, as he remained in the North to keep an eye on the sizable British presence on Manhattan. In autumn 1781, Washington finally led a combined Franco-American army south, to lay siege to a British army under Lord Charles Cornwallis , which was trapped in Yorktown, Virginia. Caught between Washington's army on land and the French navy at sea, Cornwallis had no choice but to surrender to Washington on 19 October 1781, ending the active phase of the war. Two years later, the Treaty of Paris of 1783 was finalized, and in November, the last British soldiers evacuated New York City.

Constitutional Crisis

In December 1783, Washington resigned as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army and returned to Mount Vernon, intending to retire to a life of gentleman farming. For the next several years, he oversaw his beloved plantation as national concern began to grow over the feebleness of the Articles of Confederation ; under the Articles, which kept the federal government weak to protect the sovereignty of the states, Congress was powerless to raise taxes or put down armed insurrections such as Shays' Rebellion (1786-87). Washington eventually concluded that the Articles would have to be totally replaced, and hesitantly agreed to serve as the president of the Constitutional Convention when it met in Philadelphia in May 1787.

The Convention produced a new framework of government, the United States Constitution, that was ratified by the necessary nine states by 1788. The new Constitution called for the election of a president to serve as the nation's chief executive; there was never any question that Washington was the man for the job, and indeed, no other candidate was seriously considered. In the US presidential election of 1789 , the electors unanimously voted him in as the first president, with John Adams elected vice president. Washington was inaugurated on 30 April 1789 at Federal Hall in New York City, burdened with defining the office of the presidency and guiding the fragile young republic through the tumultuous years to come.

During his two terms in office, Washington utilized the same caution that had served him so well on the battlefield. He refrained from adopting any title or official procedure that smacked of monarchy – preferring to go by the humble title of 'Mr. President' – and held himself aloof from the partisanship that was bubbling in his cabinet. In the first years of the Washington Administration, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton proposed a controversial financial program that called for the federal government to assume state debts and for the establishment of a national bank. This plan was hotly opposed by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and his southern supporters. Hamilton and Jefferson frequently clashed in cabinet meetings until the Compromise of 1790, in which Jefferson agreed to support Hamilton's plan in return for the new Federal City – to be named in Washington's honor – to be built on the Potomac River. The partisan struggles were only beginning, however, and would escalate throughout the remainder of Washington's presidency and beyond.

In 1794, the Whiskey Rebellion broke out in western Pennsylvania, when farmers rose in revolt against a new liquor excise tax imposed by Hamilton. Washington, though initially reluctant to resort to military force, raised a 13,000-man federalized militia that suppressed the rebellion without having to fight a single battle. The incident strengthened the authority of the federal government. The Washington Administration also prosecuted the Northwest Indian War (1790-1795), which was fought between the US and a coalition of Native American nations for control of the Northwest Territory. General 'Mad' Anthony Wayne led US troops to victory at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, forcing the Native Americans to cede their claims in the territory to the US in the resultant Treaty of Greenville; the British, who had offered clandestine support to the natives, were also compelled to abandon their forts in the region.

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

Much of Washington's second term was defined by the concurrent French Revolution (1789-1799), which was engulfing Europe in a total war. Although Jefferson and the emerging Democratic-Republican Party urged him to support Revolutionary France, Washington pursued a policy of neutrality and refused to get involved in the French Revolutionary Wars . Controversy over this decision was compounded by the Jay Treaty of 1794, which strengthened the United States' economic ties to Britain. Both of these issues provided fodder for the growing rivalry between the Democratic-Republicans and Hamilton's Federalist Party.

Retirement & Death

At the end of his second term, Washington decided not to stand for reelection; his refusal to seek a third term set a precedent followed by every subsequent US president except for Franklin D. Roosevelt. Washington gave his Farewell Address on 19 September 1796, in which he famously warned of the dangers of political parties. He left office when his term expired on 4 March 1797 and returned to Mount Vernon. On the evening of 12 December 1799, after a day spent in the rain, supervising farming activities on horseback, Washington returned to the house with a sore throat. He fell severely ill the next morning and was heavily bled four times by his doctors. He died at 10 pm on 14 December 1799, at the age of 67. His death was mourned both in the United States and across the Western world, where he was hailed as a champion of freedom and liberty.

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Anderson, Fred. The War That Made America. Penguin Books, 2006.

- Boatner, Mark M. Cassell's Biographical Dictionary of the American War of Independence. London: Cassell, 1973., 1973.

- Chernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton. Penguin Books, 2005.

- Fleming, Thomas . The Strategy of Victory. Hachette Audio, 2017.

- Freeman, Douglas Southall. Washington. Simon & Schuster, 1995.

- George Washington and Slavery , accessed 8 Aug 2024.

- George Washington Biography - Encyclopedia Britannica , accessed 8 Aug 2024.

- McCullough, David. 1776. Simon & Schuster, 2006.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Wood, Gordon S. Empire of Liberty. Oxford University Press, 2009.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Questions & Answers

Who was george washington, where did george washington live, how did george washington win the american revolution, when was george washington elected president, related content.

Whiskey Rebellion

George Washington in the French and Indian War

Battle of Fort Washington

Youth of George Washington

Egyptian Gods - The Complete List

US Presidential Election of 1789

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

Cite This Work

Mark, H. W. (2024, August 12). George Washington . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/George_Washington/

Chicago Style

Mark, Harrison W.. " George Washington ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified August 12, 2024. https://www.worldhistory.org/George_Washington/.

Mark, Harrison W.. " George Washington ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 12 Aug 2024. Web. 06 Sep 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Harrison W. Mark , published on 12 August 2024. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

Biography of George Washington, First President of the United States

- U.S. Presidents

- Important Historical Figures

- Native American History

- American Revolution

- America Moves Westward

- The Gilded Age

- Crimes & Disasters

- The Most Important Inventions of the Industrial Revolution

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- The 20th Century

- Women's History

- M.A., History, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

George Washington (February 22, 1732–December 14, 1799) was America's first president. He served as commander-in-chief of the Colonial Army during the American Revolution , leading the Patriot forces to victory over the British. In 1787 he presided at the Constitutional Convention , which determined the structure of the new government of the United States, and in 1789 he was elected its president.

Fast Facts: George Washington

- Known For : Revolutionary War hero and America's first president

- Also Known As : The Father of His Country

- Born : February 22, 1732 in Westmoreland County, Virginia

- Parents : Augustine Washington, Mary Ball

- Died : December 14, 1799 in Mount Vernon, Virginia

- Spouse : Martha Dandridge Custis

- Notable Quote : "To be prepared for war is one of the most effective means of preserving peace."

George Washington was born on February 22, 1732, in Westmoreland County, Virginia to Augustine Washington and Mary Ball. The couple had six children—George was the oldest—to go with three from Augustine's first marriage. During George's youth his father, a prosperous planter who owned more than 10,000 acres of land, moved the family among three properties he owned in Virginia. He died when George was 11. His half-brother Lawrence stepped in as a father figure for George and the other children.

Mary Washington was a protective and demanding mother, keeping George from joining the British Navy as Lawrence had wanted. Lawrence owned the Little Hunting Creek plantation—later renamed Mount Vernon—and George lived with him from the age of 16. He was schooled entirely in Colonial Virginia, mostly at home, and didn't go to college. He was good at math, which suited his chosen profession of surveying, and he also studied geography, Latin, and English classics. He learned what he really needed from backwoodsmen and the plantation foreman.

In 1748 when he was 16, Washington traveled with a surveying party plotting land in Virginia’s western territory. The following year, aided by Lord Fairfax—a relative of Lawrence's wife—Washington was appointed official surveyor of Culpeper County, Virginia. Lawrence died of tuberculosis in 1752, leaving Washington with Mount Vernon, one of Virginia's most prominent estates, among other family properties.

Early Career

The same year his half-brother died, Washington joined the Virginia militia. He showed signs of being a natural leader, and Virginia Lt. Gov. Robert Dinwiddie appointed Washington adjutant and made him a major.

On Oct. 31, 1753, Dinwiddie sent Washington to Fort LeBoeuf, later the site of Waterford, Pennsylvania, to warn the French to leave land claimed by Britain. When the French refused, Washington had to retreat hastily. Dinwiddie sent him back with troops and Washington's small force attacked a French post, killing 10 and taking the rest prisoner. The battle marked the start of the French and Indian War, part of the worldwide conflict known as the Seven Years War between Britain and France.

Washington was given the honorary rank of colonel and fought a number of other battles, winning some and losing others, until he was made commander of all Virginia troops. He was only 23. Later, he was sent home briefly with dysentery and finally, after being turned down for a commission with the British Army, he retired from his Virginia command and returned to Mount Vernon. He was frustrated by poor support from the Colonial legislature, poorly trained recruits, and slow decision-making by his superiors.

On January 6, 1759, a month after he had left the army, Washington married Martha Dandridge Custis, a widow with two children. They had no children together. With the land he had inherited, property his wife brought with her to the marriage, and land granted him for his military service, he was one of the wealthiest landowners in Virginia. After his retirement he managed his property, often pitching in alongside the workers. He also entered politics and was elected to Virginia's House of Burgesses in 1758.

Revolutionary Fever

Washington opposed British actions against the Colonies such as the British Proclamation Act of 1763 and the Stamp Act of 1765, but he continued to resist moves to declare independence from Britain. In 1769, Washington introduced a resolution to the House of Burgesses calling for Virginia to boycott British goods until the Acts were repealed. He began to take a leading role in Colonial resistance against the British following of the Townshend Acts in 1767.

in 1774, Washington chaired a meeting that called for convening a Continental Congress, to which he became a delegate, and for using armed resistance as a last resort. After the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, the political dispute became an armed conflict.

Commander-in-Chief

On June 15, Washington was named commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. On paper, Washington and his army were no match for the mighty British forces. But although Washington had little experience in high-level military command, he had prestige, charisma, courage, intelligence, and some battlefield experience. He also represented Virginia, the largest British colony. He led his forces to retake Boston and win huge victories at Trenton and Princeton, but he suffered major defeats, including the loss of New York City.

After the harrowing winter at Valley Forge in 1777, the French recognized American Independence, contributing a large French Army and a navy fleet. More American victories followed, leading to the British surrender at Yorktown in 1781. Washington formally said farewell to his troops and on December 23, 1783, he resigned his commission as commander-in-chief, returning to Mount Vernon.

New Constitution

After four years of living the life of a plantation owner, Washington and other leaders concluded that the Articles of Confederation that had governed the young country left too much power to the states and failed to unify the nation. In 1786, Congress approved the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to amend the Articles of Confederation. Washington was unanimously chosen as convention president.

He and other leaders, such as James Madison and Alexander Hamilton , concluded that instead of amendments, a new constitution was needed. Though many leading American figures, such as Patrick Henry and Sam Adams , opposed the proposed constitution, calling it a power grab, the document was approved.

Washington was elected unanimously by the Electoral College in 1789 as the nation's first president. Runner-up John Adams became vice president. In 1792 another unanimous vote by the Electoral College gave Washington a second term. In 1794, he stopped the first major challenge to federal authority, the Whiskey Rebellion, in which Pennsylvania farmers refused to pay federal tax on distilled spirits, by sending in troops to ensure compliance.

Washington did not run for a third term and retired to Mount Vernon. He was again asked to be the American commander if the U.S. went to war with France over the XYZ affair , but fighting never broke out. He died on December 14, 1799, possibly from a streptococcal infection of his throat made worse when he was bled four times.

Washington's impact on American history was massive. He led the Continental Army to victory over the British. He served as the nation's first president. He believed in a strong federal government, which was accomplished through the Constitutional Convention that he led. He promoted and worked on the principle of merit. He cautioned against foreign entanglements, a warning that was heeded by future presidents. He declined a third term, setting a precedent for a two-term limit that was codified in the 22nd Amendment.

In foreign affairs, Washington supported neutrality, declaring in the Proclamation of Neutrality in 1793 that the U.S. would be impartial toward belligerent powers in a war. He reiterated his opposition to foreign entanglements in his farewell address in 1796.

George Washington is considered one of the most important and influential U.S. presidents whose legacy has survived for centuries.

- " George Washington Biography ." Biography.com.

- " George Washington: President of the United States ." Encyclopedia Brittanica.

- George Washington's First Cabinet

- US Presidents With No Political Experience

- One-Term US Presidents

- President James Madison: Facts and Biography

- 10 Facts About George Washington

- The First Ten Presidents of the United States

- 10 Things to Know About John F. Kennedy

- 10 of the Most Influential Presidents of the United States

- 9 Presidents Who Were War Heroes

- Biography of Sally Jewell, Former U.S. Secretary of the Interior

- Chart of the Presidents and Vice Presidents