Essay on Religion In The Philippines

Students are often asked to write an essay on Religion In The Philippines in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Religion In The Philippines

Introduction.

The Philippines, a country in Southeast Asia, is known for its rich culture, which includes diverse religious beliefs. Religion plays a significant role in the lives of Filipinos, influencing their daily activities, traditions, and values.

Major Religions

The most followed religion in the Philippines is Christianity, with Roman Catholicism being the largest denomination. Other Christian groups include Protestants and Philippine Independent Church members. Additionally, Islam is the second largest religion, mainly practiced by the Moro people.

Influence on Society

Religion greatly impacts Filipino society. It shapes their moral values, traditions, and festivals. For instance, the famous Sinulog Festival is a religious event honoring the Santo Niño, or the child Jesus.

Religious Freedom

The Philippines respects religious freedom. The country’s constitution allows everyone to practice their religion freely. This respect for diversity contributes to the peaceful coexistence of different religious groups in the Philippines.

250 Words Essay on Religion In The Philippines

The Philippines is a country with a rich mix of cultures and beliefs. This is mostly due to its history of being a part of different empires and colonies. Today, the country is known for its strong religious faith, with the majority of people practicing Christianity.

Christianity in the Philippines

Christianity is the most followed religion in the Philippines. It was introduced by the Spanish in the 16th century. Now, more than 80% of the population are Roman Catholics. This makes the Philippines the third-largest Catholic country in the world. People go to church every Sunday and also on special holidays. Christmas and Easter are the most important celebrations.

Other Religions

Islam is the second most popular religion in the Philippines. It is mainly practiced in the southern region. There are also other religions like Buddhism, Hinduism, and tribal religions. These are followed by a small number of people.

Religion and Daily Life

Religion plays a big part in the daily life of Filipinos. It guides their actions, decisions, and how they see the world. It is also seen in many festivals and celebrations. These events are filled with music, dance, and lots of food. They are a way for people to show their faith and thank their gods.

In conclusion, religion is a very important part of life in the Philippines. It shapes the way people live, think, and act. Even though there are many different religions, they all teach people to be good and kind to others.

500 Words Essay on Religion In The Philippines

Christianity is the main religion in the Philippines. It was introduced by Spanish colonizers in the 16th century. Today, about 80% of Filipinos are Roman Catholics. They have many traditions and rituals like attending mass, praying the rosary, and celebrating festivals. One famous event is the Sinulog Festival, a colorful celebration in honor of the Santo Niño, or the child Jesus.

Islam in the Philippines

Islam is the second largest religion in the Philippines. It arrived in the country before Christianity, through Arab traders in the 13th century. Most Filipino Muslims live in the southern part of the country, in Mindanao. They are known as Moros, a term given by the Spanish. They have their own unique traditions and customs, such as observing Ramadan, a month of fasting, and celebrating Eid al-Fitr, a feast marking the end of Ramadan.

Other Religions and Beliefs

Religion’s role in society.

Religion is a big part of Filipino life. It influences their values, traditions, and way of life. It is common to see religious symbols in homes, schools, and public places. Religious events and holidays are widely celebrated, like Christmas and Holy Week for Christians, and Eid al-Fitr for Muslims.

In conclusion, religion in the Philippines is diverse and deeply ingrained in the culture. It shapes the country’s history, influences its society, and adds color to its celebrations. Despite the differences in beliefs, Filipinos are known for their respect and tolerance towards other religions, showing the world a beautiful example of religious harmony.

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Unsupported Browser Detected. It seems the web browser you're using doesn't support some of the features of this site. For the best experience, we recommend using a modern browser that supports the features of this website. We recommend Google Chrome , Mozilla Firefox , or Microsoft Edge

- National Chinese Language Conference

- Teaching Resources Hub

- Language Learning Supporters

- Asia 21 Next Generation Fellows

- Asian Women Empowered

- Emerging Female Trade Leaders

- Global Talent Initiatives

- About Global Competence

- Global Competency Resources

- Teaching for Global Understanding

- Thought Leadership

- Global Learning Updates

- Results and Opportunities

- News and Events

- Our Locations

Religion in the Philippines

Gold Buddha statues, Fo Guang Shan Chu Un Temple, Cebu City, Philippines (Jopeel Quimpo/Unsplash)

by Jack Miller

The Philippines proudly boasts to be the only Christian nation in Asia. More than 86 percent of the population is Roman Catholic, 6 percent belong to various nationalized Christian cults, and another 2 percent belong to well over 100 Protestant denominations. In addition to the Christian majority, there is a vigorous 4 percent Muslim minority, concentrated on the southern islands of Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan. Scattered in isolated mountainous regions, the remaining 2 percent follow non-Western, indigenous beliefs and practices. The Chinese minority, although statistically insignificant, has been culturally influential in coloring Filipino Catholicism with many of the beliefs and practices of Buddhism , Daoism , and Confucianism .

Asia Society in Manila

For more Asia Society work on the Philippines, please visit Asia Society Philippines . Asia Society Philippines aims to strengthen relationships and bridge differences across the Philippines, Asia and the United States.

The pre-Hispanic belief system of Filipinos consisted of a pantheon of gods, spirits, creatures, and men that guarded the streams, fields, trees, mountains, forests, and houses. Bathala, who created earth and man, was superior to these other gods and spirits. Regular sacrifices and prayers were offered to placate these deities and spirits--some of which were benevolent, some malevolent. Wood and metal images represented ancestral spirits, and no distinction was made between the spirits and their physical symbol. Reward or punishment after death was dependent upon behavior in this life.

Anyone who had reputed power over the supernatural and natural was automatically elevated to a position of prominence. Every village had its share of shamans and priests who competitively plied their talents and carried on ritual curing. Many gained renown for their ability to develop anting-anting, a charm guaranteed to make a person invincible in the face of human enemies. Other sorcerers concocted love potions or produced amulets that made their owners invisible.

Upon this indigenous religious base two foreign religions were introduced -- Islam and Christianity -- and a process of cultural adaptation and synthesis began that is still evolving. Spain introduced Christianity to the Philippines in 1565 with the arrival of Miguel Lopez de Legaspi. Earlier, beginning in 1350, Islam had been spreading northward from Indonesia into the Philippine archipelago. By the time the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, Islam was firmly established on Mindanao and Sulu and had outposts on Cebu and Luzon. At the time of the Spanish arrival, the Muslim areas had the highest and most politically integrated culture on the islands and, given more time, would probably have unified the entire archipelago. Carrying on their historical tradition of expelling the Jews and Moros [Moors] from Spain (a commitment to eliminating any non-Christians), Legaspi quickly dispersed the Muslims from Luzon and the Visayan islands and began the process of Christianization. Dominance over the Muslims on Mindanao and Sulu, however, was never achieved during three centuries of Spanish rule. During American rule in the first half of this century the Muslims were never totally pacified during the so-called "Moro Wars." Since independence, particularly in the last decade, there has been resistance by large segments of the Muslim population to national integration. Many feel, with just cause, that integration amounts to cultural and psychological genocide. For over 10 years the Moro National Liberation Front has been waging a war of secession against the Marcos government.

While Islam was contained in the southern islands , Spain conquered and converted the remainder of the islands to Hispanic Christianity. The Spanish seldom had to resort to military force to win over converts, instead the impressive display of pomp and circumstance, clerical garb, images, prayers, and liturgy attracted the rural populace. To protect the population from Muslim slave raiders, the people were resettled from isolated dispersed hamlets and brought "debajo de las companas" (under the bells), into Spanish organized pueblos. This set a pattern that is evident in modern Philippine Christian towns. These pueblos had both civil and ecclesiastical authority; the dominant power during the Spanish period was in the hands of the parish priest. The church, situated on a central plaza, became the locus of town life. Masses, confessions, baptisms, funerals, marriages punctuated the tedium of everyday routines. The church calendar set the pace and rhythm of daily life according to fiesta and liturgical seasons. Market places and cockfight pits sprang up near church walls. Gossip and goods were exchanged and villagers found "both restraint and release under the bells." The results of 400 years of Catholicism were mixed -- ranging from a deep theological understanding by the educated elite to a more superficial understanding by the rural and urban masses. The latter is commonly referred to as Filipino folk Christianity, combining a surface veneer of Christian monotheism and dogma with indigenous animism. It may manifest itself in farmers seeking religious blessings on the irrice seed before planting or in the placement of a bamboo cross at the comer of a rice field to prevent damage by insects. It may also take the form of a folk healer using Roman Catholic symbols and liturgy mixed with pre-Hispanic rituals.

When the United States took over the Philippines in the first half of the century, the justifications for colonizing were to Christianize and democratize. The feeling was that these goals could be achieved only through mass education (up until then education was reserved for a small elite). Most of the teachers who went to the Philippines were Protestants, many were even Protestant ministers. There was a strong prejudice among some of these teachers against Catholics. Since this Protestant group instituted and controlled the system of public education in the Philippines during the American colonial period, it exerted a strong influence. Subsequently the balance has shifted to reflect much stronger influence by the Catholic majority.

During the period of armed rebellion against Spain, a nationalized church was organized under Gregorio Aglipay, who was made "Spiritualhead of the Nation Under Arms." Spanish bishops were deposed and arrested, and church property was turned over to the Aglipayans. In the early part of the 20th century the numbers of Aglipayans peaked at 25 to 33 percent of the population. Today they have declined to about 5 percent and are associated with the Protestant Episcopal Church of the United States. Another dynamic nationalized Christian sect is the lglesia ni Kristo, begun around 1914 and founded by Felix Manolo Ysagun. Along with the Aglipayans and Iglesia ni Kristo, there have been a proliferation of Rizalist sects, claiming the martyred hero of Philippine nationalism, Jose B. Rizal as the second son of God and are incarnation of Christ. Leaders of these sects themselves often claim to be reincarnations of Rizal, Mary, or leaders of the revolution; claim that the apocalypse is at hand for non-believers; and claim that one can find salvation and heaven by joining the group. These groups range from the Colorums of the 1920s and 1930s to the sophisticated P.B.M.A. (Philippine Benevolent Missionary Association, headed by Ruben Ecleo). Most of those who follow these cults are the poor, dispossessed, and dislocated and feel alienated from the Catholic church.

The current challenge to the supremacy of the Catholic church comes from a variety of small sects -- from the fundamentalist Christian groups, such as Jehovah's Witnesses and Seventh Day Adventists, to the lglesia ni Kristo and Rizalists. The Roman Catholics suffer from a lack of personnel (the priest to people ratio is exceedingly low), putting them at a disadvantage in gaining and maintaining popular support. The Catholic church is seeking to meet this challenge by establishing an increasingly native clergy and by engaging in programs geared to social action and human rights among the rural and urban poor. In many cases this activity has led to friction between the church and the Marcos government, resulting in arrests of priests, nuns, and lay people on charges of subversion. In the "war for souls" this may be a necessary sacrifice. At present the largest growing religious sector falls within the province of these smaller, grass roots sects; but only time will tell where the percentages will finally rest.

Discover More About the Religions Across Asia

The Origins of Buddhism

Confucianism

For further reference.

Agoncillo, Teodoro. A Short History of the Philippines . New York: Mentor Books, 1969.

Carroll, John J., and others. Philippine Institutions . Manila: Solidaridad, 1970.

Chaffee, Frederic H., and others. Area Handbook for the Philippines . Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1969.

Corpuz, Onofre D. The Philippines . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; Spectrum Books, paper, 1965.

Gowing, Peter G., and Robert D. McArnis, eds. The Muslim Filipinos . Manila: Solidaridad, 1974.

Mercado, Leonardo N., ed. Filipino Religious Psychology . Tacloban City, Philippines: Divine Word University, 1977.

Ramos, Maximo D. Creatures of Philippine Lower Mythology . Quezon City, Philippines: University of the Philippines Press, 1971.

Sturtevant, David R. Popular Uprisings in the-Philippines , 1840-1940. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1976.

Connect With Us!

Looking for more, the origins of the muslim separatist movement in the philippines, muslim separatists in the southern philippines, reflections on the eid, related exhibition.

Asia Society Museum Presents Comparative Hell: Arts of Asian Underworlds

Discover asia.

Discover dynamic educational content for youth and families focused on Asian cultures and global learning.

Thank You for Reading!

If you’d like to support creating more resources like this please consider donating or becoming a member .

Learn more about Asia Society Education .

Religion, Customs, and Tradition of the Philippines: A Tapestry of Spiritual and Cultural Diversity

Religion, Customs, and Tradition of the Philippines – Cultural Heritage of Philippines

The Philippines, known for its stunning natural beauty, is also home to a rich tapestry of religious diversity. The spiritual landscape is woven with threads of indigenous beliefs, colonial influences, and contemporary faiths. This article unravels the intricate layers of religion, customs, and traditions in the Philippines, exploring the significance of sacred spaces, customs, and the fusion of spiritual practices that shape the nation’s cultural heritage.

Indigenous Beliefs: Ancestral Spirits and Nature Worship

Anito worship: connecting with ancestors.

Before the arrival of foreign influences, indigenous communities in the Philippines practiced animism. Anito worship involved connecting with ancestral spirits through rituals and ceremonies. Sacred spaces, such as ancient trees or natural formations, served as altars for communing with the spirit world. Despite the impact of later religions, elements of animistic beliefs persist in Filipino culture.

Bathala: The Supreme Deity

Bathala, considered the supreme deity in pre-colonial Tagalog mythology, represented the creator of all things. Worship of Bathala involved rituals expressing gratitude for nature’s bounty. Although the prominence of Bathala waned with the introduction of new religions, the concept of a supreme being remains ingrained in the Filipino psyche.

Colonial Influences: The Arrival of Christianity

Spanish colonization and the spread of christianity.

The 16th century marked a transformative period in Philippine history with the arrival of Spanish colonizers, bringing Christianity to the archipelago. The Spanish introduced Roman Catholicism, leaving an indelible mark on the religious landscape. The fusion of indigenous beliefs with Catholicism gave rise to a unique syncretic form of worship.

Baroque Churches: Architectural Testaments of Faith

The Spanish colonial era left a profound architectural legacy with the construction of Baroque churches across the Philippines. These architectural marvels, such as the San Agustin Church in Manila, stand as testaments to the enduring faith of the Filipino people. Intricate carvings, ornate altars, and religious artworks within these churches reflect the fusion of Spanish and indigenous influences.

Roman Catholicism: Pillar of Filipino Spirituality

Feast of the black nazarene: a symbol of devotion.

The Feast of the Black Nazarene in Quiapo, Manila, is an iconic religious event that draws millions of devotees. The Black Nazarene, a dark-skinned statue of Jesus Christ, is venerated for its supposed miraculous powers. The annual procession, marked by devotees participating barefoot and pulling the carriage of the Black Nazarene, is an expression of deep devotion and penance.

Santo Niño: Child Jesus as Patron

The veneration of the Santo Niño, or the Child Jesus, is widespread in the Philippines. The Sinulog Festival in Cebu, dedicated to the Santo Niño, is a grand celebration featuring a colorful parade and street dancing. The devotion to the Santo Niño reflects the Filipinos’ enduring childlike faith and resilience amid challenges.

Islamic Heritage in the Philippines

Islam in the southern philippines.

In contrast to the predominantly Christian regions, the southern part of the Philippines has a significant Muslim population. Islam was introduced by Arab traders before Spanish colonization. The Marawi Grand Mosque in Mindanao stands as a symbol of Islamic heritage, showcasing the architectural influence of the Middle East.

Ramadan and Eid al-Fitr: Celebrating Islamic Traditions

Muslims in the Philippines observe Ramadan, a month of fasting, prayer, and reflection. The culmination of Ramadan is celebrated with Eid al-Fitr, marked by communal prayers, feasting, and acts of charity. These traditions highlight the cultural diversity within the Philippines, where different religious communities coexist.

Chinese Traditions and Buddhism

Chinese influence in filipino culture.

The Philippines has a significant Chinese community that has contributed to the cultural mosaic. Chinese traditions, including ancestral veneration, the Dragon Boat Festival, and the Lunar New Year, are celebrated alongside local customs. The blending of Chinese and Filipino cultures is evident in practices like feng shui influencing architectural design and city planning.

Buddhism in the Philippines: A Minority Presence

While Buddhism is a minority religion in the Philippines, there are communities that practice Theravada Buddhism. The presence of Buddhist temples, such as the Seng Guan Temple in Manila, reflects the multicultural landscape of the country. Buddhists engage in meditation, rituals, and the observance of Buddhist festivals.

Iglesia ni Cristo: A Homegrown Faith

Iglesia ni cristo: an indigenous christian church.

Founded in 1914, the Iglesia ni Cristo (Church of Christ) is a homegrown Christian denomination with a significant following in the Philippines. Known for its unique doctrines and architectural landmarks like the INC Central Temple, this indigenous Christian church has played a prominent role in the country’s religious landscape.

Rethinking The Future (RTF) is a Global Platform for Architecture and Design. RTF through more than 100 countries around the world provides an interactive platform of highest standard acknowledging the projects among creative and influential industry professionals.

Intangible Cultural Heritage of the Philippines: A Tapestry of Tradition

Food and Cuisine of the Philippines: A Gastronomic Journey Through Cultural Heritage

Related posts.

Wingsweep: A Masterpiece by Kendrick Bangs Kellogg

Fernandez Architecture: Crafting Elegance and Minimalism in Architectural Excellence

Christ Hospital Joint and Spine Center, USA: Revolutionizing Healthcare Architecture

Buerger Center for Advanced Pediatric Care, USA: Elevating Pediatric Healthcare Architecture

The New Hospital Tower at Rush University Medical Center, USA: Redefining Healthcare Architecture Excellence

Teletón Infant Oncology Clinic, Mexico: A Paradigm of Healing Architecture

- Architectural Community

- Architectural Facts

- RTF Architectural Reviews

- Architectural styles

- City and Architecture

- Fun & Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Design Studio Portfolios

- Designing for typologies

- RTF Design Inspiration

- Architecture News

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Construction & Materials

- Covid and Architecture

- Interior Design

- Know Your Architects

- Landscape Architecture

- Materials & Construction

- Product Design

- RTF Fresh Perspectives

- Sustainable Architecture

- Top Architects

- Travel and Architecture

- Rethinking The Future Awards 2022

- RTF Awards 2021 | Results

- GADA 2021 | Results

- RTF Awards 2020 | Results

- ACD Awards 2020 | Results

- GADA 2019 | Results

- ACD Awards 2018 | Results

- GADA 2018 | Results

- RTF Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2016 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2015 | Results

- RTF Awards 2014 | Results

- RTF Architectural Visualization Competition 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2020 – Results

- Designer’s Days of Quarantine Contest – Results

- Urban Sketching Competition May 2020 – Results

- RTF Essay Writing Competition April 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2019 – Finalists

- The Ultimate Thesis Guide

- Introduction to Landscape Architecture

- Perfect Guide to Architecting Your Career

- How to Design Architecture Portfolio

- How to Design Streets

- Introduction to Urban Design

- Introduction to Product Design

- Complete Guide to Dissertation Writing

- Introduction to Skyscraper Design

- Educational

- Hospitality

- Institutional

- Office Buildings

- Public Building

- Residential

- Sports & Recreation

- Temporary Structure

- Commercial Interior Design

- Corporate Interior Design

- Healthcare Interior Design

- Hospitality Interior Design

- Residential Interior Design

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- Urban Design

- Host your Course with RTF

- Architectural Writing Training Programme | WFH

- Editorial Internship | In-office

- Graphic Design Internship

- Research Internship | WFH

- Research Internship | New Delhi

- RTF | About RTF

- Submit Your Story

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Understanding the why and how of Filipino religiosity

Mahar Mangahas’ column on the persistence of Filipino religiosity made for a very informative and provocative reading (“The religiosity of Filipinos,” 4/23/2022). Although surveys capture perceptions and attitudes about events and behaviors, they have one built-in limitation: they do not answer the how and why questions, which are also important in gaining a deep and holistic understanding of the enduring importance of religious faith for most of us. It raises three questions.

The first question is why has religion remained durable and vital for Filipinos across time amid secularizing and pluralizing influences? Everyone’s educated guess may be good as mine. One perhaps is religion’s differentiated function to provide meaning and purpose to life or answers to questions of ultimate value that science or political ideologies seemed not able to match or replace. In addition, there is also empirical evidence that shows a strong and direct link between religiosity and economic status. Thus, it may not be a stretch to say that the lamentable fact that majority of Filipinos are economically vulnerable contributes to their abiding private form of religiosity.

Second, based on the belief that religion is not only about right believing but is also about right living, the other important question to ask is how does religiosity impact one’s day-to-day life? The Bible does not lack statements reminding believers that religious faith without good work is dead, or blessed are those who hear the word of God and obey it. Pope Francis puts it more bluntly: It is not enough to say we are Christians; we must live the faith not only with words but with our actions.

Finally, and since religion and politics are also bedfellows in this country, would it not be too much to ask that, for this fast-approaching May 9 national elections, we allow ourselves to be guided by religion’s shared commitment to the common good when we choose and vote for the most qualified president of our beloved country?

NOEL G. ASIONES [email protected]

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Subscribe to our newsletter!

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

This is an information message

We use cookies to enhance your experience. By continuing, you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more here.

Filipino Culture

Philippines

The Philippines is unique among its neighbours in the South East Asian region in that the majority of Filipinos identify as Christian (92.5%). More specifically, 82.9% of the population identify as Catholic, 2.8% identify as Evangelical Christian, 2.3% identify as Iglesia ni Kristo and 4.5% identify with some other Christian denomination. Of the remaining population, 5.0% identify as Muslim, 1.8% identify with some other religion, 0.6% were unspecified and 0.1% identify with no religion. The Catholic Church and state were officially separated in the 1990s, yet Catholicism still plays an prominent role in political and societal affairs.

Christianity in the Philippines

There continues to be a process of cultural adaptation and synthesis of Christianity into the local culture since the introduction of the religion into the Philippines. The denomination of Christianity that became most embedded in Filipino culture is Catholicism, which was introduced in the Philippines during the early colonial period by the Spanish. Catholic ideas continue to inform beliefs throughout Filipino society such as the sanctity of life and respect for hierarchy . As a branch of Christianity, Catholicism believes in the doctrine of God as the ‘Holy Trinity’ comprising the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Like most Catholics, many Filipinos accept the authority of the priesthood and the Roman Catholic Church, which is led by the Pope.

For many Filipinos, the time of ‘fiesta’ is an important event within the community. During the Catholic event of fiesta, the local community comes together to celebrate the special day of the patron saint of a town or ‘ barangay ’ (village). It is a time for feasting, bonding and paying homage to the patron saint. Houses are open to guests and plenty of food is served. The fiesta nearly always includes a Mass, but its primary purpose is a social gathering of the community. On a day-to-day level, Catholic iconography is evident throughout the Philippines. Indeed, it is common to find churches and statues of various saints all throughout the country. Moreover, many towns and cities are named after saints (for example, San Miguel [‘Saint Michael’] located in Luzon and Santa Catalina [‘Saint Catherine’] located in Visayas).

In terms of other Christian denominations, there is a strong presence of Protestant traditions in the Philippines, in part due to the United States colonisation of the country. Many teachers from the United States were Protestants who were responsible for instituting and controlling the public education system of the country. As such, they had a strong influence over the Philippines, particularly with the dispersing of Protestant attitudes and beliefs. The Philippines also contains a number of Indigenous Christian Churches, such as the Iglesia Filipina Independiente (Independent Philippine Church) and Inglesia ni Kristo (Church of Christ). These churches are usually popular among the marginalised in society who feel disconnected from the Catholic Church.

Islam in the Philippines

Islam was introduced to the southern Philippines from neighbouring countries in Southeast Asia, such as Malaysia and Indonesia. The religion rapidly declined as the main monotheistic religion in the Philippines when the Spanish entered the country. In present day Philippines, most of the Muslim population in the Philippines reside in the southern islands of Mindanao, Sulu and Palawan.

Contemporary Muslim Filipino communities are often collectively known as Moros. Most Moros practice Sunni Islam, while a small minority practice Shi’a and Ahmadiyya. Like Catholicism, Islam in the Philippines has absorbed local elements, such as making offerings to spirits ( diwatas ). All Moros tend to share the fundamental beliefs of Islam, but the specific practices and rituals vary from one Moro group to another.

Grow and manage diverse workforces, markets and communities with our new platform

- Religious Beliefs In The Philippines

The major religion in the Philippines is Roman Catholic Christianity, followed by Islam and other types of Christianity. In the Philippines, all religions are protected by the law, and no one religious belief is given priority over any other. Below is an overview of the largest religions in the country, with data from the CIA World Factbook.

Roman Catholic Christianity - 80.6%

Roman Catholicism is the largest religion in the Philippines. This religion was first introduced through the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan in the early 1500s. Magellan, whose original destination was Spice Island, arrived on Cebu Island in the Philippines due to a missed route. He then proceeded to make Roman Catholicism a state religion by first converting the Chief of Cebu, and several hundreds of his followers. Today, a large majority of the population of the Philippines - around 80% - identifies as Roman Catholic.

Protestant Christianity - 8.2%

Protestant Christianity is the second-largest religious group in the Philippines. Evangelical Protestantism was introduced into the Philippines by American missionaries after the Spanish-American War between the late 18th and early 19th Centuries. Some Protestant groups which are affiliated with the Philippine Council of Evangelical Churches (PCEC), however, were established locally, without any foreign influence.

Islam - 5.6%

Islam is the third-largest religion in the Philippines after Catholicism and Christianity. The religion existed in the region for around a century before the spread of Christianity. Islam first spread to Simunul Island in the Philippines through foreign trade with countries such as India . Specifically, it was the Islamic cleric-Karim ul' Makhdum who first introduced the religion to the area. Subsequently, he established the first mosque on the same Island, which is today, the oldest mosque in the country.

Other - 1.9%

Other minor religions in the country include Hinduism, Judaism, the Baha'i Faith, Indigenous Beliefs, Other Christians, and Atheists.

Indigenous traditions predate the colonial religions of Islam and Christianity in the Philippines. The most predominant views are that of animism, which is the belief that even non-living entities such trees and plants have spirits. Indigenous religions are characterized by the worship of various deities, as opposed to the monotheistic religions. With regards to influence, other religions, even the predominant Roman Catholic, have adopted animism in combination with their own beliefs. This blending is known as religious syncretism.

Other Christian groups in the country include Jehovah's Witnesses, Latter-Day Saints, Assemblies of God, Seventh-day Adventists, and numerous others.

| Rank | Religion | Population (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Roman Catholic | 80.6 |

| 2 | Protestant | 8.2 |

| 3 | Muslim | 5.6 |

| 4 | Other | 1.9 |

| 5 | Tribal Religions | .2 |

| 6 | None | .1 |

More in Society

The Most Powerful Armies In The World

The Most Isolated Tribe on Earth

Countries Who Have Never Won A Summer Olympic Medal

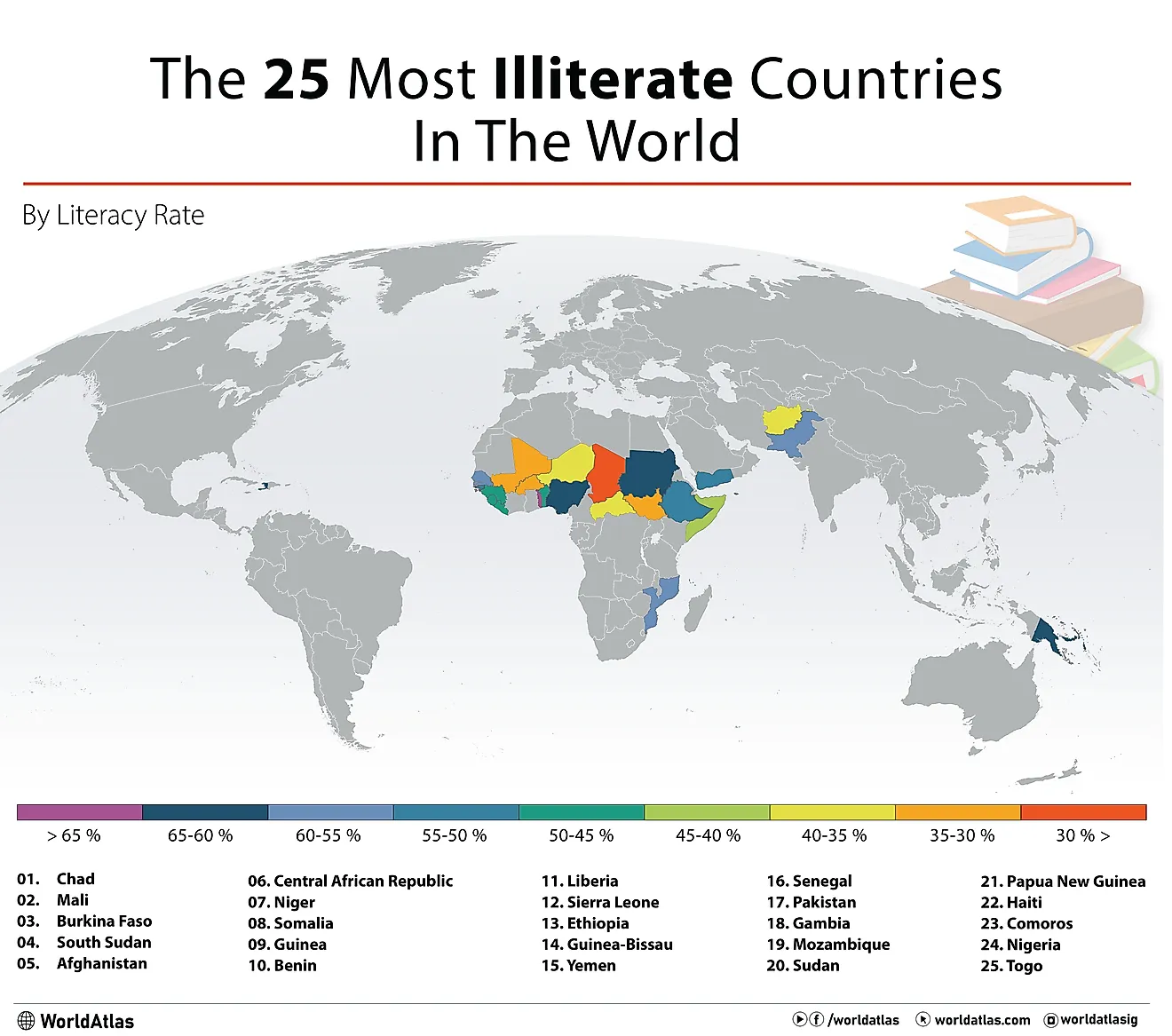

25 Most Illiterate Countries

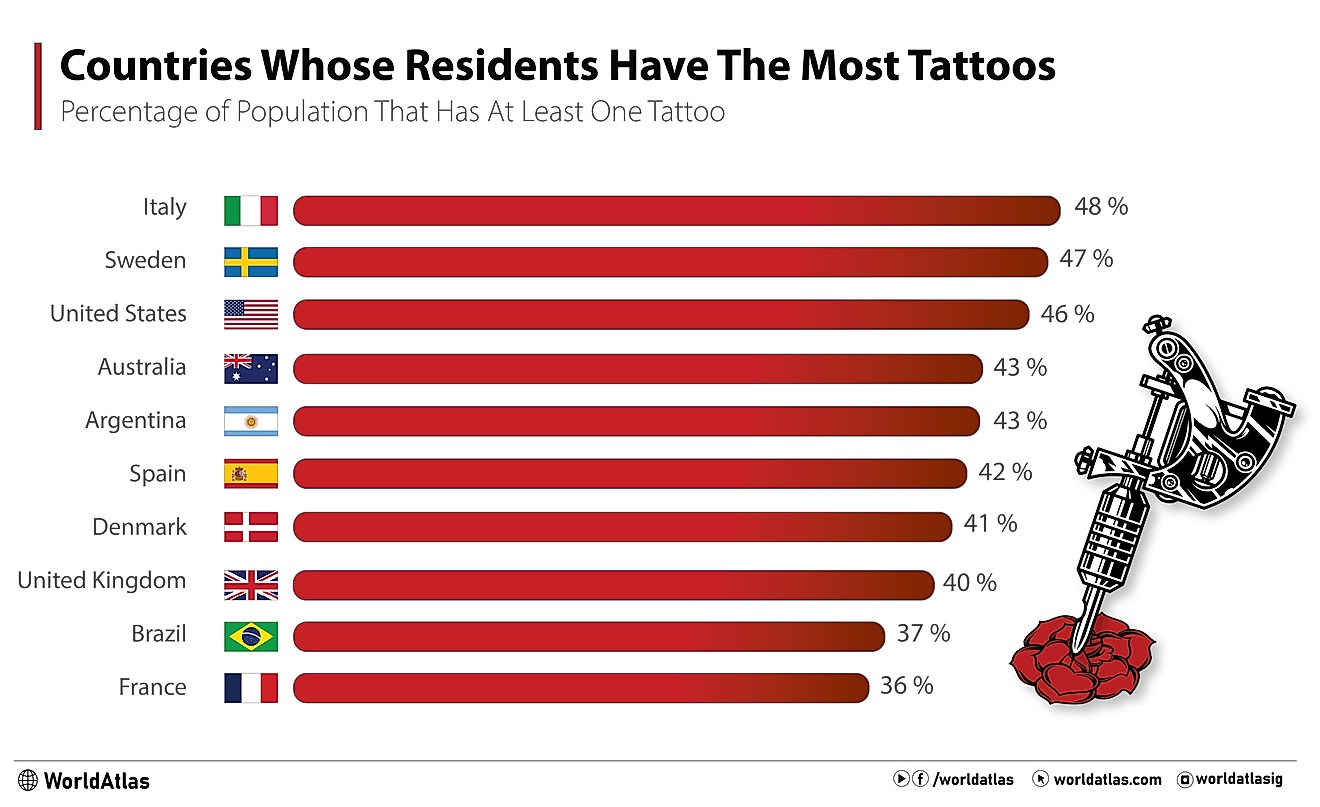

Which Country's Residents Have the Most Tattoos?

Alan Watts' Guide To The Meaning Of Life

Did Nietzsche Believe In Free Will?

Is Metaphysics The Study Of Philosophy Or Science?

Read The Diplomat , Know The Asia-Pacific

- Central Asia

- Southeast Asia

- Environment

- Asia Defense

- China Power

- Crossroads Asia

- Flashpoints

- Pacific Money

- Tokyo Report

- Trans-Pacific View

- Photo Essays

- Write for Us

- Subscriptions

Remembering 500 Years of Christianity in the Philippines

Recent features.

Why Is South Korea’s President Yoon So Unpopular?

The Logic of China’s Careful Defense Industry Purge

The Ko Wen-je Case Points to Deeper Problems in Taiwan Politics

Anarchy in Anyar: A Messy Revolution in Myanmar’s Central Dry Zone

The Complex Legacy of Ahmad Shah Massoud

Diplomacy Beyond the Elections: How China Is Preparing for a Post-Biden America

Sri Lanka’s Presidential Manifestos: What’s Promised for Women?

The Global Battle for Chip Talent: South Korea’s Strategic Dilemma

Bangladesh’s New Border Stance Signals a Shift in Its Approach to India

The Solomon Islands-China Relationship: 5 Years On

Finding Home in Bishkek: Kyrgyzstan’s South Asian Expats

Kashmir at the Boiling Point as Elections Loom

Asean beat | society | southeast asia.

Imported to the Philippine islands by Spanish imperialists, Catholicism has had complex and contradictory impacts on the nation’s subsequent evolution.

The Saint Augustine Church, completed in 1710, in the municipality of Paoay, Ilocos Norte, the Philippines.

As I was reading the final papers submitted by the students in the course I teach on world religion, I noticed a common theme when it comes to their appreciation for religion in general, and for Christianity in particular. While most acknowledged the significant role of Christianity as an institution in the Philippines, there was a sense of ambivalence when it came to appreciating the religion’s overall impact in the country, due to the controversies in which it has often been involved, both historically and in contemporary society.

The complexity of these feelings reflects a larger reality in the country as it celebrates the 500th anniversary of the arrival of Christianity in the Philippines this year. The year-long celebration will formally begin on April 4, 2021 – Easter Sunday – and end on April 22, 2022. The Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines (CBCP) is spearheading the celebration, and has been working on it for the last nine years. Among the events to be commemorated are the first Easter Mass in the country on the island of Limasawa, and the first baptism in Cebu. More than 500 “ Jubilee churches ” have also been identified for the celebration. Pilgrims who visit one of these churches any time until April 22, 2022 may receive plenary indulgences according to the February 25 decree issued by Pope Francis to the CBCP. Many Filipino Catholics also tuned in to the Pope’s March 14 mass, which was dedicated to the 500-year anniversary of Christianity in the Philippines.

Celebrating – or even remembering – the arrival of Christianity in the Philippines, however, is complex and wrought with controversy. For one thing, the evangelization of the Philippines is understandably tied up with the reality of Spanish colonialism. The phrase “the Sword and the Cross” is commonly used in discussing the Spanish conquest of the Philippine islands in the 16th century. With Christianity sometimes described by some historians and educators as an instrument of colonialism, it shares some blame for the violence, abuses, and oppression that Filipinos experienced at the hands of Spain.

This narrative still figures significantly today, both in popular memory and formal history education. Textbooks, curriculum guides, and class discussions usually highlight the role of the friars in the pacification of the Philippines, as well as their abuses, especially in the late 19th century. This negative perception of the Church and the friars was entrenched in the popular imagination by Jose Rizal’s path-breaking novels “Noli Me Tangere” and “El Filibusterismo,” which have become required readings in schools and universities. Even President Rodrigo Duterte was dismissive of the commemoration, saying that he does not see the relevance of celebrating an event that led to the colonization and subjugation of Filipinos.

Remembering Christianity’s arrival in the Philippine islands can also be a sensitive topic for segments of the population who have suffered especially because of it. Despite the well-meaning efforts of the friars during the early Spanish colonial period, certain indigenous practices, beliefs and traditions were altered, replaced, or forgotten due to evangelization. One of the most cited issues related to this was that of precolonial shamans called babaylan , who were vilified and disempowered in the process of evangelization. Some feminists and gender rights activists also blame Christianity for the introduction of patriarchal social structures and the prevailing conservatism of the country when it comes to women and gender issues. The Christianization of the country has also led to the marginalization of non-Christian narratives in Philippine history, such as that of Muslim Mindanao .

Certain advocacy groups have also historically clashed with the Catholic Church and other Christian groups over various pieces of progressive legislation. In 1956, for example, the Catholic Church hierarchy and several Christian lay organizations fiercely opposed Republic Act 1425 – more commonly known as the Rizal Law – which required educational institutions to study the life and works of Rizal, particularly the two anti-colonial novels mentioned above. The Catholic Church hierarchy and several Christian groups also lobbied for decades against the Reproductive Health Bill , even after it was eventually passed into law in 2012. Moreover, these same groups continue to represent the most entrenched opposition to the legalization of divorce in the Philippines. Christianity’s involvement in politics has also been highlighted given the tendency of certain politicians to cite Christian values and texts when dealing with social issues, and even when arguing for controversial legislation such as the re-imposition of the death penalty .

As an educator, I believe that one of the greater challenges in the commemoration of Christianity’s 500-year history in the country is the lack of opportunity for most Filipinos to discuss and learn about Church history, something that would make the commemoration more meaningful for many people.

For one thing, an accurate knowledge and appreciation of Philippine Church history can help correct (or add nuance to) some of the common misconceptions about the Church, especially regarding its role in colonization and the abuses usually associated with it. While the negative stereotypes about Christianity have a solid basis, an accurate and a more nuanced study of Philippine Church History could lead to a fuller appreciation of the role of Christianity in the formation of the nation. For example, while supporting the Spanish conquest, the Church has also been at the forefront of fights for justice, from the Synod of Manila in 1582 to the bishops and religious officials who have spoken out against extrajudicial killings of the present day. The Catholic Church and other Christian groups have also been integral in promoting acts of charity throughout history, from setting up hospitals, leprosariums, and asylums during the Spanish colonial period, to providing aid and shelter for typhoon victims and those affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Learning more about the history of Philippine Christianity may also provide Filipino Christians and clerics with the necessary knowledge and perspective to allow them to critically evaluate how they have responded (and are responding) to the call of the times. Christianity’s successes over the last half-millennium may offer inspiration and direction for its leaders and believers, but a recognition of its failures might also provide a much-needed humility, and caution against a triumphalist approach to the commemoration.

Lastly, one can hope that the study of Philippine Church history may also invite people to realize that the quincentennial celebration is also an affirmation of how Christianity has transcended its colonial roots, and has been integrated in the culture and identity of Filipino Christians who have repeatedly chosen the faith despite multiple opportunities to abandon it. It is a testament not just to the relevance of the religion, but to the agency of Filipinos in charting their own destiny.

Philippines LGBTQ Activists Protest Arrest of Drag Artist

By robin vochelet.

Fugitive Philippine Pastor Surrenders to Police After Long Manhunt

By sebastian strangio.

Philippine Lawmakers Pass Bill Legalizing Divorce

Philippine Church Denies FBI Allegations Amid Abuse Investigation

By associated press.

Arakan Army Commander-in-Chief Twan Mrat Naing on the Future of Rakhine State

By rajeev bhattacharyya.

US Air Force Deploys More Stealth Jets to Southeast Asia

By christopher woody.

Islamic Fundamentalism Raises Its Head in Post-Hasina Bangladesh

By snigdhendu bhattacharya.

Kim Jong Un Abandoned Unification. What Do North Koreans Think?

By kwangbaek lee and rose adams.

By Mitch Shin

By K. Tristan Tang

By James Baron

By Naw Theresa

The Politics of Religion in the Philippines

Thirty years ago, on Feb. 22, 1986, then Jaime Cardinal Sin made an urgent call on church-owned Radio Veritas for Filipinos to take to the streets and support the revolt against President Ferdinand E. Marcos. For most Filipinos, Jaime Cardinal Sin’s message was what started the People Power Revolution, with hundreds of thousands of supporters forming a human barricade between Camp Crame and Camp Aguinaldo (thereby protecting the “rebels” – former President Fidel Ramos and Senator Juan Ponce Enrile). It was a show of force and a moment of truth for a nation that wanted freedom from the 20-year Marcos dictatorship. Had people not responded to the Cardinal’s call, Philippine history might have been very different. As candidates vie for endorsements ahead of May 9 general elections, here’s a look back at the role organized churches have had in Philippine politics, and a look ahead at how this might play out in these elections.

The notion of a “ politics of religion ” refers to the increasing role that religion plays in the politics of the contemporary world and the consequences that a politics of religion has on inclusive nation-building, democracy, and human rights. The involvement of religious groups in Philippine politics is not new. During the Spanish colonial era, the “indio priests” advocated for the “secularization” of the Catholic church to allow “native priests” to head parishes. At that time, it was an act of treason that demanded the death penalty, for only “Filipinos” (i.e., Spaniards born in the Philippines) were deemed to have the capacity to govern and thus native priests could not serve as parish priests. The 1872 mutiny which resulted in the death of the three priests, Gomez, Burgos, and Zamora, became the “seed” of the Philippine Revolution, inspiring the Filipino heroes Rizal and Bonifacio to “imagine a Filipino nation” and lead a revolution against Spain to achieve it.

Fast forward to the Marcos years, and discussions on Vatican II, liberation theology, the student uprisings in the 1960s and 1970s, community organizing, and the impact of Martial Law figured in the various discussions among the different religious congregations, including the Redemptorist Community and the Jesuit Mission. Vatican II saw the Catholic Church’s reawakening of the zeal to embark in new pastoral initiatives such as serving the poor and the marginalized, and to solicit the contributions of the laity in pastoral care. The human rights violations under President Marcos and the increase in the number of “desaparecidos” (victims of human rights abuses who have disappeared) resulted in the collective anger and frustrations that exploded into the People Power movement. According to the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility, from July 1973 to October 1984 there were at least 22 military raids on church establishments, four of them on institutions of the Protestant Church. Seminaries, Catholic schools, and other facilities were ransacked or closed. Priests, nuns, and laypersons were detained.

While the People Power movement led to the downfall of President Marcos, the Catholic Church has remained a powerful opposing force on issues such as the Reproductive Health Bill and divorce. President Aquino signed the Reproductive Health Bill in December 2012, but it wasn’t until 2014 that the Supreme Court declared it constitutional. The Divorce Bill is still caught up in a contentious battle (the Philippines is the only country in the world, aside from Vatican City, that lacks divorce laws.)

Historically, organized churches have been involved in electoral politics in the Philippines, including in the selection of candidates and church members who have run in elections themselves. For instance, the Iglesia ni Cristo (Church of Christ), with a tradition of bloc voting required from its 1 million voting members, has allegedly supported presidential candidates throughout history: President Marcos in 1986, Eduardo Cojuangco in 1992, Joseph Estrada in 1998, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo in 2004, and Manny Villar in 2010. The Jesus is Lord movement ran campaigns themselves (Bro. Eddie Villanueva in the 2004 Presidential elections, where he won 3% of the votes), and most recently, the Pilipino Movement for Transformational Leadership (PMTL), a community composed of Catholics, Protestants, and Born Again groups, bonded together to elect “God-centered servants.” For the May 2016 elections, the PMTL claims it can muster up to 10 million voters out of the 54.6 million Filipinos registered to vote.

The Catholic Church, though not endorsing political candidates, exhorts the voters to vote “according to one’s conscience.” In the launch of the “One Good Vote” campaign against bribery and vote buying, Luis Antonio Cardinal Tagle recalled the casting of ballots during the papal conclave, and exhorted voters to pray and have a formulation based on one’s religion.

Just how potent are the political endorsements of religious groups? In the case of Iglesia ni Cristo, whose members are required to vote as a bloc, previous endorsements have failed: Eduardo Cojuangco came in 3rd, Estrada was ousted in 2001 because of corruption charges, Macapagal-Arroyo had graft charges and is under hospital arrest, and Manny Villar lost the elections. And yet, despite the failed endorsements, candidates still trooped to the INC compound to get the “blessing” (and votes) of its executive minister. A million votes can certainly swing the tide in a hotly-contested election.

Judging by the recent events that involved the INC, its endorsement of a presidential candidate might not auger well for either the church or for its endorsed candidate. The 101-year-old Church faces its worst crisis in years – former ministers are accusing top leaders of corruption and illegal detention of members who dare question the INC . In July, it expelled the sibling and mother of its executive minister, Eduardo Manalo, for “sowing disunity” in the Church. It also had a previous minister, Menorca, arrested for alleged illegal possession of a hand grenade. In August, it organized a protest rally against the Department of Justice’s supposed meddling into its internal affairs but drew flak instead from netizens and the general public who were stranded or suffered long commutes because protesters rendered EDSA impassable. Even statements from presidential candidates Grace Poe and Jejomar Binay that INC members were “just protecting their faith” were criticized for defending a church that is demanding special privileges and immunity from criminal charges.

Most recently, Senatorial candidate Manny Pacquiao lost the endorsement of Nike (and some voters as well) when he erred in making a slur against the LGBT community. Invoking Bible verses in his defense, he failed to realize that a prejudicial remark from any political candidate will not sit well with any group that still faces discrimination. But then again, his bigoted remark could work both ways: he will clearly lose the votes of the LGBT community and human rights advocates, but perhaps he will earn the votes of some ultra-conservatives.

So, 75 days to the May presidential and local elections, candidates will literally move heaven and earth to get the nod of voters. For some of them, the fastest route may be through organized churches.

Maribel Buenaobra is The Asia Foundation’s deputy country representative in the Philippines. She can be reached at [email protected] . The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author and not those of The Asia Foundation or its funders.

Media Contact

Our development experts and staff in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States are available for media briefings and speaking engagements.

For assistance, please contact Global Communications: Eelynn Sim, Director, Strategy and Programs [email protected]

Featured Announcement

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolo.

Related News & Insights

View All News & Insights

Transforming a Time-Honored Tradition of Community Mediation

Reducing the Price of Justice: Alternative Dispute Resolution in Bangladesh

Indonesia: The Road to Restorative Justice

Information

- Author Services

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

Filipino college students’ attitudes towards religion: an analysis of the underlying factors.

1. Introduction

2. the need for a new measure: peculiar traits, 3. present study, 4. participants and procedure, 5. measures, 6.1. test of hypothesized model, 6.2. scale construction, 6.3. age, sex, and academic program, 7. discussion, 8. conclusions, acknowledgments, author contributions, conflicts of interest.

- Abad, R. 2001. Religion in the Philippines. Philippine Studies 49: 337–67. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alexander, Hanan, and Terence McLaughlin. 2003. Education in religion and spirituality. In The Blackwell Guide to the Philosophy of Education . Edited by Nigel Blake, Paul Smeyers, Richard Smith and Paul Standish. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. [ Google Scholar ]

- Astley, Jeff, Leslie Francis, and Mandy Robbins. 2012. Assessing attitude towards religion: The Astley–Francis Scale of attitude towards theistic faith. British Journal of Religious Education 34: 183–93. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baring, Rito. 2011. Plurality in unity: Challenges towards religious education in the Philippines. Religious Education 106: 459–75. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baring, Rito. 2012. Children’s Image of God and their parents: explorations in children’s Spirituality. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 17: 277–89. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baring, Rito, and Rebecca Cacho. 2015. Contemporary engagements and challenges for Catholic religious education in Southeast Asia. In Global Perspectives on Catholic Religious Education in Schools . Edited by Michael Buchanan and Adrian Gellel. Basel: Springer Publishing, pp. 143–53. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baring, Rito, Romeo Lee, Madelene Sta. Maria, and Yan Liu. 2016a. Configurations of student spirituality/religiosity: Evidence from a Philippine university. International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 21: 163–76. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baring, Rito, Dennis Erasga, Elenita Garcia, Jeane Peracullo, and Lars Ubaldo. 2016b. The Young and the sacred: an analysis of empirical evidence from the Philippines. Young 25: 26–44. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Baring, Rito, Romeo Lee, Madelene Sta. Maria, and Yan Liu. 2017. Exploring the Characteristics of Filipino University Students as Concurrent Smokers and Drinkers. Asia Pacific Social Science Review 17: 80–87. [ Google Scholar ]

- Batara, Jame Bryan. 2015. Overlap of religiosity and spirituality among Filipinos and its implications towards religious prosociality. International Journal of Research Studies in Psychology 4: 3–21. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Brown, Laurence, and Joseph Forgas. 1980. The structure of religion: A multi-dimensional scaling of informal elements. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 19: 423–31. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Büssing, Arndt. 2017. Measures of Spirituality/Religiosity: Description of Concepts and Validation of Instruments. Religions 8: 11. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines-Episcopal Commission on Youth (CBCP-ECY) and Catholic Educational Association of the Philippines (CEAP). 2014. The National Filipino Catholic Youth Study 2014 . Manila: CBCP-ECY and CEAP. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davies, Douglas. 2011. Emotion, Identity, and Religion: Hope, Reciprocity, and Otherness . Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dy-Liacco, Gabriel, Ralph Piedmont, Nichole Murray-Swank, Thomas Rodgerson, and Martin Sherman. 2009. Spirituality and religiosity as cross-cultural aspects of human experience. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 1: 35–52. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- David Elkins, James Hedstrom, Lorie Hughes, Andrew Leaf, and Cheryl Saunders. 1988. Toward a humanistic-phenomenological spirituality: Definition, description, and measurement. Journal of Humanist Psychology 28: 5–18. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Francis, Leslie. 1993. Reliability and validity of a short scale of attitude towards Christianity among adults. Psychological Reports 72: 615–18. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Francis, Leslie, John Lewis, Ronald Philipchalk, Laurence Brown, and David Lester. 1995. The internal consistency reliability and construct validity of the Francis scale of attitude toward Christianity (adult) among undergraduate students in the U.K., U.S.A., Australia and Canada. Personality and Individual Differences 19: 949–53. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Giordan, Giuseppe, and William Swatos Jr., eds. 2012. Religion, Spirituality and Everyday Practice . New York: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Good, Marie, and Teena Willoughby. 2014. Institutional and Personal Spirituality/Religiosity and Psychosocial adjustment in adolescence: Concurrent and Longitudinal associations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 43: 757–74. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Hambleton, Ronald. 2005. Issues, Designs and technical guidelines for adapting tests into multiple languages and cultures. In Adapting Educational and Psychological Tests for Cross-Cultural Assessment . Edited by Ronald K. Hambleton, Peter Merenda and Charles Spielberger. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 3–18. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hernandez, Brittany. 2011. The Religiosity and Spirituality Scale for Youth: Development and Initial Validation. Doctoral dissertation, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA. Available online: http://etd.lsu.edu/docs/available/etd-10142011-115001/unrestricted/hernandez_diss.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2017).

- Hill, Peter, and Lauren Maltby. 2009. Measuring religiousness and spirituality: Issues, existing measures, and the implications for education and well-being. In International Handbook of Education for Spirituality, Care and Wellbeing . Edited by Marian de Souza, Leslie Francis, James O’Higgins-Norman and Daniel Scott. New York: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hill, Peter, Kenneth Pargament, Ralph Hood Jr., Michael McCullough, James Swyers, David Larson, and Brian Zinnbauer. 2000. Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of communality, points of departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior 30: 51–77. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- King, Pamela Ebstyne, and Chris Boyatzis. 2004. Exploring adolescent spiritual and religious development: Current and future theoretical and empirical perspectives. Applied Developmental Science 8: 2–6. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Koenig, Harold. 2009. Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: A review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 54: 283–92. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Koenig, Harold. 2010. Spirituality and mental health. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies 7: 116–22. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lee, Romeo, Rito Baring, Madelene Sta. Maria, and Stephen Reysen. 2016. Attitude towards technology, social media usage and grade point average as predictors of global citizenship identification in Filipino university students. International Journal of Psychology 52: 213–19. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Lynch, Gordon. 2007. The New Spirituality: An Introduction to Progressive Belief in the Twenty-First Century . London: I.B. Taurus. [ Google Scholar ]

- MacDonald, Douglas, Friedman Harris, Brewczynski Jacek, Holland Daniel, Salagame Kiran Kumar, Mohan Krishna, Gubrij Zuzana Ondriasova, and Cheong Hye Wook. 2015. Spirituality as a Scientific Construct: Testing Its Universality across Cultures and Languages. PLoS ONE 10: e0117701. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Mangahas, Mahar, and Linda Guerrero. 1992. Religion in the Philippines: The 1991 ISSP Survey . Manila: SWS Occasional Paper, May. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mansukhani, Roseann, and Ron Resurreccion. 2009. Spirituality and the development of positive character among Filipino adolescents. Philippine Journal of Psychology 42: 271–90. [ Google Scholar ]

- McQuillan, P. 2006. Youth spirituality: A reality in search of expression. Australian eJournal of Theology 6: 1–13. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ocampo, Anna Carmella, Roseann Mansukhani, Bernadette Mangrobang, and Alexandra Mae Juan. 2013. Influences and perceived impact of spirituality on Filipino adolescents. Philippine Journal of Psychology 46: 89–113. [ Google Scholar ]

- Parboteeah, Praveen, Martin Hoegl, and John Cullen. 2008. Ethics and religion: An empirical test of a multidimensional model. Journal of Business Ethics 80: 387–98. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Prasad, Hari Mohan, and Rajnish Mohan. 2009. Group Discussion and Interview , 2nd ed. Victoria: Abe Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tan, Charlene. 2009. Reflection for spiritual development in Adolescents. In International Handbook of Education for Spirituality, Care and Wellbeing . Edited by Marian de Souza, Leslie Francis, James O’Higgins-Norman and Daniel Scott. Dordrecht: Springer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tsang, Jo-Ann, and Michael McCullough. 2003. Measuring religious constructs: A hierarchical approach to construct organization and scale selection. In Handbook of Positive Psychological Assessment . Edited by Shane Lopez and Charles Snyder. Washington: American Psychological Association. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Someren, David. 2000. The Relationship between Religiousness and Moral Development: A Critique and Refinement of the Sociomoral Reflection Measure Short-Form of Gibbs, Basinger, and Fuller (John C. Gibbs, Karen S. Basinger, Dick Fuller). Ed.D. thesis, Clark University, Worcester, MA, USA. Available online: http://youthandreligion.nd.edu/related-resources/bibliography-on-youth-and-religion/faith-and-moral-development/ (accessed on 5 February 2017).

- Voas, David. 2007. Does Religion Belong in Population Studies? Environment and Planning 39: 1166–80. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Zwingmann, Christian, Klein Constantin, and Büssing Arndt. 2011. Measuring Religiosity/Spirituality: Theoretical Differentiations and Categorization of Instruments. Religions 2: 345–57. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

| RELIGIOSITY | SPIRITUALITY |

|---|---|

| RELIGIOUS Dimension | RELIGIOUS Dimension |

| 1. A religious person follows his/her religion. 2. I believe in the doctrines of the Church. 3. I love God but hate religion. 4. The religious people are easily persuaded to believe in something. 5. I think religion keeps us blinded from the truths. (* eliminated items) I am presently affiliated to a religion. (1) Religious people are intolerant of those who hold different opinions (2) I honor Church doctrine through my speech and actions. (2) I know who to follow without religion. (3) I always depend on my faith. (1) My religion makes me religious. (1) | 1. Spirituality is about believing in God. 2. For me spirituality is concerned with religious matters. 3. Spirituality is beyond any religion. 4. The spiritual person is one who loves religion. 5. Spirituality indicates how one’s beliefs are practiced in daily life. 6. I leave everything to God. 7. I am happy to see different religions in my midst. 8. The religious person knows many things about Scriptures. (* eliminated items) Spirituality is about religion. (1, 3) It is about accepting Gods word. (8) About worship and glorifying God. (4) An aspect of a firm believer. (1, 4) One who surrenders everything to God. (6) One who believes in God. (1) Being spiritual is being faithful to God. (1) Someone who reads the Bible. (8) Being able to practice Christ’s teachings. (5) |

| 1. Religious persons are those who go to Church. 2. A religious person is a person of prayer. 3. I observe religious traditions (e.g., devotions) in the Church. 4. Religiosity is measured in personal spiritual habits that I do. 5. It is about religious acts and devotions. 6. Passing by the church I do the sign of the cross. 7. I am active in church activities. (* eliminated items) I think I am not religious because I don’t have time for the church. (1) I have stopped visiting the church now. (1) I take active part in Church assemblies. (1) I think religious persons perform religious rituals in church everyday. (1, 3, 5) Being religious is about showing one’s beliefs in one’s daily life. (3, 4) | 1. I respect those who perform clerical (priestly) function in Church. 2. I don’t go to Church but only during Simbang Gabi Masses. 3. I put into action the Lord’s teachings. 4. I can still pray even without going to Church. 5. It is important that I dedicate a time for God. 6. I remember the souls or spirits of people who have died. (* eliminated items) Its about living out one’s devotion to God. (2, 3) Spirituality is about being religious. (1, 2, 3) Following God’s laws. (1, 2, 3) It reminds me of the Church. (1) It is an aspect of being religious. (1) One who believes without belonging to a church. (2) |

| 1. I believe a religious person is God-centered. 2. For me, religiosity promotes blind faith. 3. I feel that I need to have a relationship with God. 4. Religiosity means having a blessed life with God. (* eliminated items) The life I live reflects Jesus’ teachings. (3, 4) I practice Christ’s teachings in my life. (3) Being religious involves a personal acceptance of Jesus. (3, 4) A religious person is someone faithful to God. (3) A religious person is someone who lives his/her life for God. (3) I show utmost respect for God. (3, 4) One who is religious is God-fearing. (1) I love God above all. (3) | 1. In my life, I try to do God’s will. 2. In every decision I make, I put God first. 3. I feel that spiritual persons are enlightened by God. 4. Salvation for me is essential for religion. 5. I believe that God is merciful. (* eliminated items) None |

| HUMAN Dimension | HUMAN Dimension |

| 1. A religious person is someone who realizes their faults. 2. A religious person is someone who is well disciplined. 3. Religious persons are concerned about doing good deeds. 4. I think those who are religious have strong values and morals. 5. A religious person lives a stress-free life. 6. Religious persons are quite conservative. 7. Religiosity is associated with being hypocritical. | 1. Those who are religious are compassionate. 2. He/she is a loving and trusting person. 3. Religious people have a sincere heart. 4. I feel that a religious person is very reflective. 5. I feel the love of God in my life. 6. I feel that God is beside me when I’m down. 7. I’m always happy because God is in me. 8. I’m willing to do everything to please God. 9. I feel safe because of God. 10. Spirituality and religious values go together. 11. Loving someone intimately is a spiritual experience. 12. Serving God wholeheartedly is demanded by spirituality. 13. When I attend Church worship I feel free. 14. When I worship in church I feel holy. 15. A religious individual does not commit mistakes. 16. Religion generates a lifestyle that is founded on God. 17. Religious people possess positive attitudes towards others. 18. I cry with joy as I worship God. 19. My faith makes me feel like a newborn baby. 20. I only pray when I have a problem. |

| (* eliminated upon merging with the social commitment component items under “spirituality”) It means being open to the world. (1) Someone who serves his neighbor without condition. (4) It is when Christians help their fellow human beings. (4) | 1. Spirituality involves concern for the environment. 2. Spirituality demands that I follow my own conscience. 3. Those who reject an immoral social order are religious. 4. Religious persons have the responsibility to improve society. 5. Being religious invites us to help the poor. 6. Lifting our spirit and others is the mark of religion. 7. A religious person is someone who serves neighbour without condition. (* eliminated items) Lifting one’s spirit and that of others is the mark of spirituality. (5) |

| (* eliminated upon merging with the spirituality items due to similarities) It involves getting connected to our emotions and appearance. (2) They possess positive attitudes towards others (2) Someone who is afraid of offending others. (4) One who is reflective about life. (2) It reflects the person’s spirit, strength, freedom and faith. (3) A mark of complete dedication. (6) Has self-respect and respect for others. (7) It is shown in acts arising from one’s pure intentions. (1, 5) | 1. Spirituality involves looking at our lives with purpose. 2. Those that I know to be religious are in touch with themselves. 3. Faith essentially completes me as a person. 4. Spirituality involves inner peace of mind. 5. Religious persons possess a clean heart and mind. 6. Spirituality is a reflection of my beliefs and decisions. 7. Holy persons are those who value life. 8. Religion taught me to face life’s problems without questioning God. 9. Religion reminds me that God created me. 10. A religious person is a role model. 11. Religiosity involves getting connected to our emotions and appearance. (* eliminated items) The spiritual life show our inner self. (1) A spiritual person is a model. (10) |

| RELIGIOUS DIMENSION | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. A religious person follows his/her religion. | * | |

| 7. I love God but I hate religion | * | |

| 26. I remember God when passing by the church | * | |

| 30. My spirituality is a reflection of my beliefs and decisions | * | |

| 34. Religiosity is associated with being hypocritical | * | |

| 37. I respect those who work as priest/pastor/imam. | * | |

| 40. A spiritual person is one who loves religion. | ||

| 43. Religion reminds me that God created me | ||

| 52. I am happy to see different religions in my midst | * | |

| 68. I believe in the doctrines of the Church | * | |

| 78. Salvation for me is essential for religion | ||

| 2. A religious person is one who goes to Church. | * | |

| 5. For me, religiosity promotes blind faith | * | |

| 8. I observe religious traditions (e.g., devotions) in the Church | * | |

| 14. Religiosity is measured in personal spiritual habits that I do | * | |

| 20. It is about religious acts and devotions | * | |

| 28. A religious person is quite conservative | * | |

| 31. For me spirituality is concerned with religious matters | * | |

| 32. I am active in church activities | * | |

| 38. A religious person is one who is compassionate | * | |

| 55. A religious person knows many things about the Scripture | * | |

| 56. I remember the souls or spirits of people who have died | * | |

| 59. I only go to Church on occasion (ex: Simbang Gabi, fellowship, etc.). | * | |

| 67. When I attend Church worship I feel free | * | |

| 69. When I worship in church I feel holy | * | |

| 9. I feel that I need to have a relationship with God | * | |

| 15. Religiosity means having a blessed life with God | * | |

| 21. In my life, I try to do God’s will | * | |

| 25. Spirituality is about believing in God | * | |

| 27. In every decision I make, I put God first | * | |

| 33. I feel that a spiritual person is enlightened by God | * | |

| 41. I believe that God is merciful | * | |

| 45. I put into action the Lord’s teachings. | * | |

| 48. I leave everything to God | * | |

| 49. I can still pray even without going to Church | * | |

| 53. It is important that I dedicate a time for God | ||

| 54. I feel the love of God in my life | ||

| 57. I feel that God is beside me when I’m down | ||

| 58. I’m always happy because God is in me | ||

| 60. I’m willing to do everything to please God | ||

| 61. I feel safe because of God | ||

| 66. Serving God wholeheartedly is demanded by faith | * | |

| 73. Religion generates a lifestyle that is founded on God. | ||

| 74. I believe a religious person is God-centered | ||

| 77. I cry with joy as I worship God. | * | |

| 3. A religious person is someone who realizes his/her faults. | ||

| 6. A religious person is someone who is well-disciplined | ||

| 13. A religious person is easily persuaded to believe in something | * | |

| 16. I think a religious person is one who has strong values and morals | * | |

| 18. My faith provides me inner peace of mind | * | |

| 22. A religious person lives a stress-free life. | * | |

| 50. I think that a religious person is very reflective. | * | |

| 62. Spirituality and religious values go together | * | |

| 65. A religious person is a person of prayer | * | |

| 72. My faith demands that I follow my own conscience. | * | |

| 75. A religious person possesses positive attitudes towards others | ||

| 80. I only pray when I have a problem. | * | |

| 10. A religious person is concerned about doing good deeds | ||

| 11. A religious person is one who rejects an immoral social order | ||

| 17. A religious person has the responsibility to improve the society | * | |

| 23. Being religious invites us to help the poor. | * | |

| 35. A religious person is someone who serves neighbor without condition | * | |

| 76. Religion involves concern for the environment | ||

| 4. Believing in faith involves looking at our lives with purpose. | ||

| 12. Faith essentially completes me as a person | * | |

| 19. I think religion keeps us blinded from the truths. | * | |

| 24. A religious person possesses a clean heart and mind | * | |

| 29. Lifting our spirit and others is the mark of religion. | * | |

| 36. Spirituality is beyond any religion. | * | |

| 39. Religion taught me to face life’s problems without questioning God | ||

| 42. A person of faith is one who is loving and trusting. | * | |

| 44. Spirituality indicates how one’s beliefs are practiced in daily life | * | |

| 46. A religious person has a sincere heart | * | |

| 47. A religious person is a role model | * | |

| 51. Religiosity involves getting connected to our emotions and physical appearance | * | |

| 63. A holy person is one who values life | * | |

| 64. Loving someone intimately is a spiritual experience. | * | |

| 70. Those that I know to be religious are in touch with themselves | * | |

| 71. A religious individual does not commit mistakes | * | |

| 79. My faith makes me feel like a newborn baby | * | |

| Model Fit Statistics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ (δφ) | CFI | NFI | RMSEA {90% CI} | AIC | ECVI {90% CI} | |

| Model 1 | 30,425.43 (3065) | 0.698 | 0.676 | 0.057 {0.057, 0.058} | 30,775.43 | 11.27 {11.06, 11.47} |

| Model 2 | 30,656.50 (3073) | 0.696 | 0.673 | 0.057 {0.057, 0.058} | 30,990.5 | 11.34 {11.14, 11.55} |

| Model 3 | 856.80 (149) | 0.93 | 0.916 | 0.059 {0.055, 0.063} | 938.8 | 0.688 {0.623, 0.758) |

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | F1 | F2 | F3 | F1 | F2 | F3 |

| 1. Religion generates a lifestyle that is founded on God. | 0.015 | 0.025 | −0.07 | 0.007 | ||

| 2. A spiritual person is one who loves religion. | 0.08 | −0.096 | 0.123 | −0.041 | ||

| 3. A religious person possesses positive attitudes towards others. | 0.064 | 0.149 | −0.056 | 0.155 | ||

| 4. I believe a religious person is God-centered. | −0.011 | 0.116 | −0.111 | −0.001 | ||

| 5. Religion involves concern for the environment. | −0.069 | 0.017 | −0.009 | 0.176 | ||

| 6. Religion reminds me that God created me. | −0.125 | −0.015 | −0.103 | 0.021 | ||

| 7. Salvation for me is essential for religion. | −0.198 | −0.04 | −0.117 | 0.048 | ||