- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Sweepstakes

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Controversial and Unethical Psychology Experiments

There have been a number of famous psychology experiments that are considered controversial, inhumane, unethical, and even downright cruel—here are five examples. Thanks to ethical codes and institutional review boards, most of these experiments could never be performed today.

At a Glance

Some of the most controversial and unethical experiments in psychology include Harlow's monkey experiments, Milgram's obedience experiments, Zimbardo's prison experiment, Watson's Little Albert experiment, and Seligman's learned helplessness experiment.

These and other controversial experiments led to the formation of rules and guidelines for performing ethical and humane research studies.

Harlow's Pit of Despair

Psychologist Harry Harlow performed a series of experiments in the 1960s designed to explore the powerful effects that love and attachment have on normal development. In these experiments, Harlow isolated young rhesus monkeys, depriving them of their mothers and keeping them from interacting with other monkeys.

The experiments were often shockingly cruel, and the results were just as devastating.

The Experiment

The infant monkeys in some experiments were separated from their real mothers and then raised by "wire" mothers. One of the surrogate mothers was made purely of wire.

While it provided food, it offered no softness or comfort. The other surrogate mother was made of wire and cloth, offering some degree of comfort to the infant monkeys.

Harlow found that while the monkeys would go to the wire mother for nourishment, they preferred the soft, cloth mother for comfort.

Some of Harlow's experiments involved isolating the young monkey in what he termed a "pit of despair." This was essentially an isolation chamber. Young monkeys were placed in the isolation chambers for as long as 10 weeks.

Other monkeys were isolated for as long as a year. Within just a few days, the infant monkeys would begin huddling in the corner of the chamber, remaining motionless.

The Results

Harlow's distressing research resulted in monkeys with severe emotional and social disturbances. They lacked social skills and were unable to play with other monkeys.

They were also incapable of normal sexual behavior, so Harlow devised yet another horrifying device, which he referred to as a "rape rack." The isolated monkeys were tied down in a mating position to be bred.

Not surprisingly, the isolated monkeys also ended up being incapable of taking care of their offspring, neglecting and abusing their young.

Harlow's experiments were finally halted in 1985 when the American Psychological Association passed rules regarding treating people and animals in research.

Milgram's Shocking Obedience Experiments

Isabelle Adam/Flickr/CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

If someone told you to deliver a painful, possibly fatal shock to another human being, would you do it? The vast majority of us would say that we absolutely would never do such a thing, but one controversial psychology experiment challenged this basic assumption.

Social psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted a series of experiments to explore the nature of obedience . Milgram's premise was that people would often go to great, sometimes dangerous, or even immoral, lengths to obey an authority figure.

The Experiments

In Milgram's experiment, subjects were ordered to deliver increasingly strong electrical shocks to another person. While the person in question was simply an actor who was pretending, the subjects themselves fully believed that the other person was actually being shocked.

The voltage levels started out at 30 volts and increased in 15-volt increments up to a maximum of 450 volts. The switches were also labeled with phrases including "slight shock," "medium shock," and "danger: severe shock." The maximum shock level was simply labeled with an ominous "XXX."

The results of the experiment were nothing short of astonishing. Many participants were willing to deliver the maximum level of shock, even when the person pretending to be shocked was begging to be released or complaining of a heart condition.

Milgram's experiment revealed stunning information about the lengths that people are willing to go in order to obey, but it also caused considerable distress for the participants involved.

Zimbardo's Simulated Prison Experiment

Darrin Klimek / Getty Images

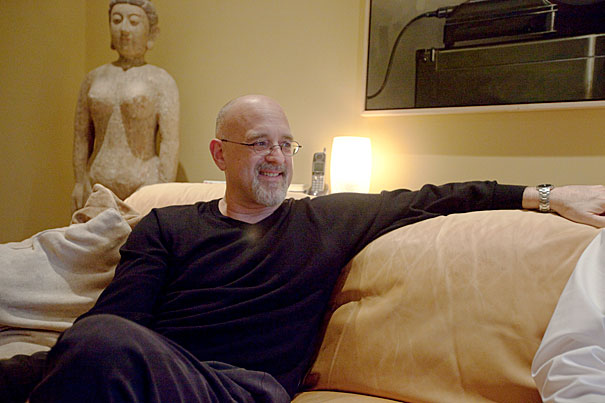

Psychologist Philip Zimbardo went to high school with Stanley Milgram and had an interest in how situational variables contribute to social behavior.

In his famous and controversial experiment, he set up a mock prison in the basement of the psychology department at Stanford University. Participants were then randomly assigned to be either prisoners or guards. Zimbardo himself served as the prison warden.

The researchers attempted to make a realistic situation, even "arresting" the prisoners and bringing them into the mock prison. Prisoners were placed in uniforms, while the guards were told that they needed to maintain control of the prison without resorting to force or violence.

When the prisoners began to ignore orders, the guards began to utilize tactics that included humiliation and solitary confinement to punish and control the prisoners.

While the experiment was originally scheduled to last two full weeks it had to be halted after just six days. Why? Because the prison guards had started abusing their authority and were treating the prisoners cruelly. The prisoners, on the other hand, started to display signs of anxiety and emotional distress.

It wasn't until a graduate student (and Zimbardo's future wife) Christina Maslach visited the mock prison that it became clear that the situation was out of control and had gone too far. Maslach was appalled at what was going on and voiced her distress. Zimbardo then decided to call off the experiment.

Zimbardo later suggested that "although we ended the study a week earlier than planned, we did not end it soon enough."

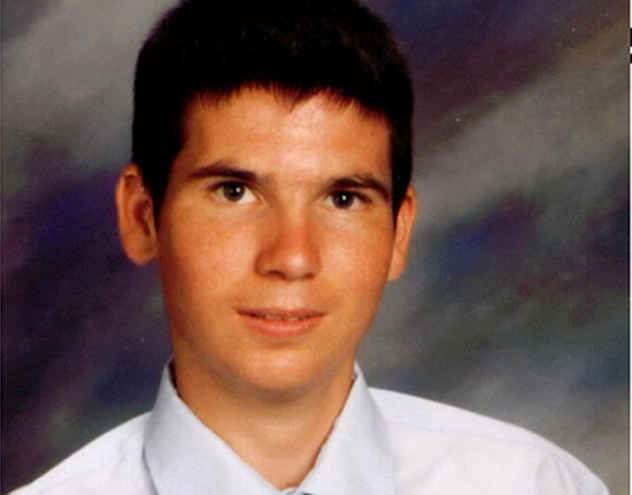

Watson and Rayner's Little Albert Experiment

If you have ever taken an Introduction to Psychology class, then you are probably at least a little familiar with Little Albert.

Behaviorist John Watson and his assistant Rosalie Rayner conditioned a boy to fear a white rat, and this fear even generalized to other white objects including stuffed toys and Watson's own beard.

Obviously, this type of experiment is considered very controversial today. Frightening an infant and purposely conditioning the child to be afraid is clearly unethical.

As the story goes, the boy and his mother moved away before Watson and Rayner could decondition the child, so many people have wondered if there might be a man out there with a mysterious phobia of furry white objects.

Controversy

Some researchers have suggested that the boy at the center of the study was actually a cognitively impaired boy who ended up dying of hydrocephalus when he was just six years old. If this is true, it makes Watson's study even more disturbing and controversial.

However, more recent evidence suggests that the real Little Albert was actually a boy named William Albert Barger.

Seligman's Look Into Learned Helplessness

During the late 1960s, psychologists Martin Seligman and Steven F. Maier conducted experiments that involved conditioning dogs to expect an electrical shock after hearing a tone. Seligman and Maier observed some unexpected results.

When initially placed in a shuttle box in which one side was electrified, the dogs would quickly jump over a low barrier to escape the shocks. Next, the dogs were strapped into a harness where the shocks were unavoidable.

After being conditioned to expect a shock that they could not escape, the dogs were once again placed in the shuttlebox. Instead of jumping over the low barrier to escape, the dogs made no efforts to escape the box.

Instead, they simply lay down, whined and whimpered. Since they had previously learned that no escape was possible, they made no effort to change their circumstances. The researchers called this behavior learned helplessness .

Seligman's work is considered controversial because of the mistreating the animals involved in the study.

Impact of Unethical Experiments in Psychology

Many of the psychology experiments performed in the past simply would not be possible today, thanks to ethical guidelines that direct how studies are performed and how participants are treated. While these controversial experiments are often disturbing, we can still learn some important things about human and animal behavior from their results.

Perhaps most importantly, some of these controversial experiments led directly to the formation of rules and guidelines for performing psychology studies.

Blum, Deborah. Love at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the science of affection . New York: Basic Books; 2011.

Sperry L. Mental Health and Mental Disorders: an Encyclopedia of Conditions, Treatments, and Well-Being . Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, an imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC; 2016.

Marcus S. Obedience to Authority An Experimental View. By Stanley Milgram. illustrated . New York: Harper &. The New York Times.

Le Texier T. Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment . Am Psychol . 2019;74(7):823‐839. doi:10.1037/amp0000401

Fridlund AJ, Beck HP, Goldie WD, Irons G. Little Albert: A neurologically impaired child . Hist Psychol. 2012;15(4):302-27. doi:10.1037/a0026720

Powell RA, Digdon N, Harris B, Smithson C. Correcting the record on Watson, Rayner, and Little Albert: Albert Barger as "psychology's lost boy" . Am Psychol . 2014;69(6):600‐611. doi:10.1037/a0036854

Seligman ME. Learned helplessness . Annu Rev Med . 1972;23:407‐412. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.23.020172.002203

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Search form

How to Live Better, Longer

Study Identifies A Factor That Affects Aging- But It's Out Of Your Control

Is Flexibility Key To Longevity? Study Links It To Survival In Middle-Aged Adults

Breakthrough Monthly Treatment May Boost Longevity, Vitality In Old Age: Mice Study Reveals

Can Folate Intake Affect Aging? Here's What Study Says

People Living With Brain Aneurysm At High Risk Of Anxiety, Depression: Study

Skipping Through Online Videos Can Boost Boredom, Try Watching Them Fully: Study

Friend's Genetic Traits Can Influence Your Mental Health Risk: Study

Watching Even 8 Minutes Of TikTok Glamorizing Disordered Eating Harms Body Image, Study Finds

Explore The Healing Power Of Expressive Arts With Wellness Coach Karen Corona

Dr. Jason Shumard Revolutionizes Holistic Healing And Transformative Wellness

Thermal Earring To Monitor Temperature: Experts Say It Could Also Track Ovulation And Stress

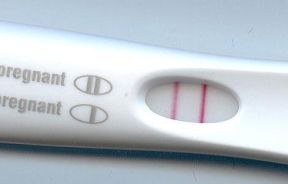

First Saliva-Based Pregnancy Tests: Everything To Know

Sleep Debt Raises Heart Disease Risk, Study Says Here's How To Mitigate It

Diabetes, Pre-Diabetes Linked To Brain Aging, Healthy Lifestyle Counteracts The Effect: Study

Study Finds Reduced Academic Achievements In Kids Exposed To Prenatal Smoking

Dengue Survivors Face Higher Long-Term Risks Than COVID-19 Recovery Patients: Study

Obesity Raises Risk Of COVID Infection By 34%: Study Says

Your Mindset Could Shape Vaccine Response, Side Effects After COVID-19 Vaccination: Study

Higher Incidence Of Mental Illness After Severe COVID In Unvaccinated Adults, Says Study

Kids Get Less Severe COVID-19 Compared To Adults; Here's Why

Mad scientists: 10 most unethical social experiments gone horribly wrong.

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Pocket

Curiosity is the fuel that drives social experiments performed in the world of science. Today, experiments must abide by the American Psychological Association’s (APA) Code of Conduct , which pertains to everything from confidentiality, to consent, to overall beneficence. However, the standards weren’t always so high. In their latest video , “10 Evil Social Experiments,” Alltime10s highlights the most famous and disturbing experiments that took place all around the world that could never happen today.

Adults, children, and even animals were a part of the inhumane practices of several mad scientists. In 1939, psychologist Wendell Johnson at the University of Iowa performed "The Monster Study," a stuttering experiment on 22 orphaned children. The children were divided into two groups. The first received positive speech therapy , in which the children's successes were praised. The other group had negative therapy and were told off for every mistake they made.

The effects on the children who had negative speech therapy were horrible. Their schoolwork suffered, their behavior became more timid, and they developed speech impediments. In 2007, six of the children were awarded $925,000 for life-long psychological damage.

In the 1970s to 1980s, during the Apartheid era, the South African army forced suspected gay and lesbian soldiers to undergo sex-change operations , chemical castrations, electrical shocks, and other forms of unethical medication, in an attempt to cure their illegal sexuality, which became known as “The Aversion Project.”

Inevitably, this became psychologically damaging to about 900 individuals who underwent reassignment operations carried out in military hospitals in South Africa throughout this period. The patients were abandoned, and often unable to pay for the hormones needed to maintain their new identity, leading some to commit suicide.

Animals could not escape the wrath of mad scientist Dr. Harry Harlow in his experiment “The Pit of Despair.” Harlow experimented on baby rhesus monkeys to study social interaction and isolation in the 1970s. He would select baby monkeys who had bonded with their mother and separate them, placing the infants in little steel chambers with no contact with anything else. He kept them in there for up to a year, causing irreparable psychosis in many of the monkeys.

The monkeys were later returned to a group, but were bullied; others starved themselves to death. When the test subjects later became mothers, they would chew off the fingers of their offspring or crush their heads. Not only were Harlow’s experiments extreme, they revealed nothing new about social interactions.

Luckily, the APA's Code of Conduct brought ethics in psychological experiments. Review boards enforce these ethics to prevent experiments like the ones listed above from occurring.

View the rest of Alltime10s video to see the most disturbing social experiment in the 20th century.

- Alzheimer's

- Amputation/Prosthetics

- Dengue Fever

- Dental Health

- Dermatological Disorders

- Developmental Disorders

- Digestive Disorders

- Down Syndrome

- Gastrointestinal Disorders

- Genetic Disorders

- Genital Warts

- Geriatric care

- Gerontology

- Gum Disease

- Gynecological Disorders

- Head And Neck Cancer

- Kidney Cancer

- Kidney Disease

- Knee Problems

- Lead Poisoning

- Liver Disease

- Low Testosterone

- Lung Cancer

- Macular Degeneration

- Men's Health

- Menstruation/Periods

- Mental Health

- Metabolic Disorders

- Pancreatic Cancer

- Parasitic Infections

- Parkinson's Disease

- Pediatric Diseases

- Schizophrenia

- Senior Health

- Sexual Health

- Sickle Cell Disease

- Skin Cancer

- Sleep Apnea

- Uterine Cancer

- Varicose Veins

- Viral Infection

- Women's Health

- Yeast Infection

Morning Rundown: Trump team downplays Arlington cemetery incident, NASA rover embarks on Mars road trip, and the YouTube star dominating ultimate frisbee

Ugly past of U.S. human experiments uncovered

Shocking as it may seem, U.S. government doctors once thought it was fine to experiment on disabled people and prison inmates. Such experiments included giving hepatitis to mental patients in Connecticut, squirting a pandemic flu virus up the noses of prisoners in Maryland, and injecting cancer cells into chronically ill people at a New York hospital.

Much of this horrific history is 40 to 80 years old, but it is the backdrop for a meeting in Washington this week by a presidential bioethics commission. The meeting was triggered by the government's apology last fall for federal doctors infecting prisoners and mental patients in Guatemala with syphilis 65 years ago.

U.S. officials also acknowledged there had been dozens of similar experiments in the United States — studies that often involved making healthy people sick.

An exhaustive review by The Associated Press of medical journal reports and decades-old press clippings found more than 40 such studies. At best, these were a search for lifesaving treatments; at worst, some amounted to curiosity-satisfying experiments that hurt people but provided no useful results.

Inevitably, they will be compared to the well-known Tuskegee syphilis study. In that episode, U.S. health officials tracked 600 black men in Alabama who already had syphilis but didn't give them adequate treatment even after penicillin became available.

These studies were worse in at least one respect — they violated the concept of "first do no harm," a fundamental medical principle that stretches back centuries.

"When you give somebody a disease — even by the standards of their time — you really cross the key ethical norm of the profession," said Arthur Caplan, director of the University of Pennsylvania's Center for Bioethics.

Attitude similar to Nazi experiments Some of these studies, mostly from the 1940s to the '60s, apparently were never covered by news media. Others were reported at the time, but the focus was on the promise of enduring new cures, while glossing over how test subjects were treated.

Attitudes about medical research were different then. Infectious diseases killed many more people years ago, and doctors worked urgently to invent and test cures. Many prominent researchers felt it was legitimate to experiment on people who did not have full rights in society — people like prisoners, mental patients, poor blacks. It was an attitude in some ways similar to that of Nazi doctors experimenting on Jews.

"There was definitely a sense — that we don't have today — that sacrifice for the nation was important," said Laura Stark, a Wesleyan University assistant professor of science in society, who is writing a book about past federal medical experiments.

The AP review of past research found:

- A federally funded study begun in 1942 injected experimental flu vaccine in male patients at a state insane asylum in Ypsilanti, Mich., then exposed them to flu several months later. It was co-authored by Dr. Jonas Salk, who a decade later would become famous as inventor of the polio vaccine.

Some of the men weren't able to describe their symptoms, raising serious questions about how well they understood what was being done to them. One newspaper account mentioned the test subjects were "senile and debilitated." Then it quickly moved on to the promising results.

- In federally funded studies in the 1940s, noted researcher Dr. W. Paul Havens Jr. exposed men to hepatitis in a series of experiments, including one using patients from mental institutions in Middletown and Norwich, Conn. Havens, a World Health Organization expert on viral diseases, was one of the first scientists to differentiate types of hepatitis and their causes.

A search of various news archives found no mention of the mental patients study, which made eight healthy men ill but broke no new ground in understanding the disease.

- Researchers in the mid-1940s studied the transmission of a deadly stomach bug by having young men swallow unfiltered stool suspension. The study was conducted at the New York State Vocational Institution, a reformatory prison in West Coxsackie. The point was to see how well the disease spread that way as compared to spraying the germs and having test subjects breathe it. Swallowing it was a more effective way to spread the disease, the researchers concluded. The study doesn't explain if the men were rewarded for this awful task.

- A University of Minnesota study in the late 1940s injected 11 public service employee volunteers with malaria, then starved them for five days. Some were also subjected to hard labor, and those men lost an average of 14 pounds. They were treated for malarial fevers with quinine sulfate. One of the authors was Ancel Keys, a noted dietary scientist who developed K-rations for the military and the Mediterranean diet for the public. But a search of various news archives found no mention of the study.

- For a study in 1957, when the Asian flu pandemic was spreading, federal researchers sprayed the virus in the noses of 23 inmates at Patuxent prison in Jessup, Md., to compare their reactions to those of 32 virus-exposed inmates who had been given a new vaccine.

- Government researchers in the 1950s tried to infect about two dozen volunteering prison inmates with gonorrhea using two different methods in an experiment at a federal penitentiary in Atlanta. The bacteria was pumped directly into the urinary tract through the penis, according to their paper.

The men quickly developed the disease, but the researchers noted this method wasn't comparable to how men normally got infected — by having sex with an infected partner. The men were later treated with antibiotics. The study was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, but there was no mention of it in various news archives.

Though people in the studies were usually described as volunteers, historians and ethicists have questioned how well these people understood what was to be done to them and why, or whether they were coerced.

Victims for science Prisoners have long been victimized for the sake of science. In 1915, the U.S. government's Dr. Joseph Goldberger — today remembered as a public health hero — recruited Mississippi inmates to go on special rations to prove his theory that the painful illness pellagra was caused by a dietary deficiency. (The men were offered pardons for their participation.)

But studies using prisoners were uncommon in the first few decades of the 20th century, and usually performed by researchers considered eccentric even by the standards of the day. One was Dr. L.L. Stanley, resident physician at San Quentin prison in California, who around 1920 attempted to treat older, "devitalized men" by implanting in them testicles from livestock and from recently executed convicts.

Newspapers wrote about Stanley's experiments, but the lack of outrage is striking.

"Enter San Quentin penitentiary in the role of the Fountain of Youth — an institution where the years are made to roll back for men of failing mentality and vitality and where the spring is restored to the step, wit to the brain, vigor to the muscles and ambition to the spirit. All this has been done, is being done ... by a surgeon with a scalpel," began one rosy report published in November 1919 in The Washington Post.

Around the time of World War II, prisoners were enlisted to help the war effort by taking part in studies that could help the troops. For example, a series of malaria studies at Stateville Penitentiary in Illinois and two other prisons was designed to test antimalarial drugs that could help soldiers fighting in the Pacific.

It was at about this time that prosecution of Nazi doctors in 1947 led to the "Nuremberg Code," a set of international rules to protect human test subjects. Many U.S. doctors essentially ignored them, arguing that they applied to Nazi atrocities — not to American medicine.

The late 1940s and 1950s saw huge growth in the U.S. pharmaceutical and health care industries, accompanied by a boom in prisoner experiments funded by both the government and corporations. By the 1960s, at least half the states allowed prisoners to be used as medical guinea pigs.

But two studies in the 1960s proved to be turning points in the public's attitude toward the way test subjects were treated.

The first came to light in 1963. Researchers injected cancer cells into 19 old and debilitated patients at a Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in the New York borough of Brooklyn to see if their bodies would reject them.

The hospital director said the patients were not told they were being injected with cancer cells because there was no need — the cells were deemed harmless. But the experiment upset a lawyer named William Hyman who sat on the hospital's board of directors. The state investigated, and the hospital ultimately said any such experiments would require the patient's written consent.

At nearby Staten Island, from 1963 to 1966, a controversial medical study was conducted at the Willowbrook State School for children with mental retardation. The children were intentionally given hepatitis orally and by injection to see if they could then be cured with gamma globulin.

Those two studies — along with the Tuskegee experiment revealed in 1972 — proved to be a "holy trinity" that sparked extensive and critical media coverage and public disgust, said Susan Reverby, the Wellesley College historian who first discovered records of the syphilis study in Guatemala.

'My back is on fire!' By the early 1970s, even experiments involving prisoners were considered scandalous. In widely covered congressional hearings in 1973, pharmaceutical industry officials acknowledged they were using prisoners for testing because they were cheaper than chimpanzees.

Holmesburg Prison in Philadelphia made extensive use of inmates for medical experiments. Some of the victims are still around to talk about it. Edward "Yusef" Anthony, featured in a book about the studies, says he agreed to have a layer of skin peeled off his back, which was coated with searing chemicals to test a drug. He did that for money to buy cigarettes in prison.

"I said 'Oh my God, my back is on fire! Take this ... off me!'" Anthony said in an interview with The Associated Press, as he recalled the beginning of weeks of intense itching and agonizing pain.

The government responded with reforms. Among them: The U.S. Bureau of Prisons in the mid-1970s effectively excluded all research by drug companies and other outside agencies within federal prisons.

As the supply of prisoners and mental patients dried up, researchers looked to other countries.

It made sense. Clinical trials could be done more cheaply and with fewer rules. And it was easy to find patients who were taking no medication, a factor that can complicate tests of other drugs.

Additional sets of ethical guidelines have been enacted, and few believe that another Guatemala study could happen today. "It's not that we're out infecting anybody with things," Caplan said.

Still, in the last 15 years, two international studies sparked outrage.

One was likened to Tuskegee. U.S.-funded doctors failed to give the AIDS drug AZT to all the HIV-infected pregnant women in a study in Uganda even though it would have protected their newborns. U.S. health officials argued the study would answer questions about AZT's use in the developing world.

The other study, by Pfizer Inc., gave an antibiotic named Trovan to children with meningitis in Nigeria, although there were doubts about its effectiveness for that disease. Critics blamed the experiment for the deaths of 11 children and the disabling of scores of others. Pfizer settled a lawsuit with Nigerian officials for $75 million but admitted no wrongdoing.

Last year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' inspector general reported that between 40 and 65 percent of clinical studies of federally regulated medical products were done in other countries in 2008, and that proportion probably has grown. The report also noted that U.S. regulators inspected fewer than 1 percent of foreign clinical trial sites.

Monitoring research is complicated, and rules that are too rigid could slow new drug development. But it's often hard to get information on international trials, sometimes because of missing records and a paucity of audits, said Dr. Kevin Schulman, a Duke University professor of medicine who has written on the ethics of international studies.

Syphilis study These issues were still being debated when, last October, the Guatemala study came to light.

In the 1946-48 study, American scientists infected prisoners and patients in a mental hospital in Guatemala with syphilis, apparently to test whether penicillin could prevent some sexually transmitted disease. The study came up with no useful information and was hidden for decades.

Story: U.S. apologizes for Guatemala syphilis experiments

The Guatemala study nauseated ethicists on multiple levels. Beyond infecting patients with a terrible illness, it was clear that people in the study did not understand what was being done to them or were not able to give their consent. Indeed, though it happened at a time when scientists were quick to publish research that showed frank disinterest in the rights of study participants, this study was buried in file drawers.

"It was unusually unethical, even at the time," said Stark, the Wesleyan researcher.

"When the president was briefed on the details of the Guatemalan episode, one of his first questions was whether this sort of thing could still happen today," said Rick Weiss, a spokesman for the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy.

That it occurred overseas was an opening for the Obama administration to have the bioethics panel seek a new evaluation of international medical studies. The president also asked the Institute of Medicine to further probe the Guatemala study, but the IOM relinquished the assignment in November, after reporting its own conflict of interest: In the 1940s, five members of one of the IOM's sister organizations played prominent roles in federal syphilis research and had links to the Guatemala study.

So the bioethics commission gets both tasks. To focus on federally funded international studies, the commission has formed an international panel of about a dozen experts in ethics, science and clinical research. Regarding the look at the Guatemala study, the commission has hired 15 staff investigators and is working with additional historians and other consulting experts.

The panel is to send a report to Obama by September. Any further steps would be up to the administration.

Some experts say that given such a tight deadline, it would be a surprise if the commission produced substantive new information about past studies. "They face a really tough challenge," Caplan said.

We need your support today

Independent journalism is more important than ever. Vox is here to explain this unprecedented election cycle and help you understand the larger stakes. We will break down where the candidates stand on major issues, from economic policy to immigration, foreign policy, criminal justice, and abortion. We’ll answer your biggest questions, and we’ll explain what matters — and why. This timely and essential task, however, is expensive to produce.

We rely on readers like you to fund our journalism. Will you support our work and become a Vox Member today?

The Stanford Prison Experiment was massively influential. We just learned it was a fraud.

The most famous psychological studies are often wrong, fraudulent, or outdated. Textbooks need to catch up.

by Brian Resnick

The Stanford Prison Experiment, one of the most famous and compelling psychological studies of all time, told us a tantalizingly simple story about human nature.

The study took paid participants and assigned them to be “inmates” or “guards” in a mock prison at Stanford University. Soon after the experiment began, the “guards” began mistreating the “prisoners,” implying evil is brought out by circumstance. The authors, in their conclusions, suggested innocent people, thrown into a situation where they have power over others, will begin to abuse that power. And people who are put into a situation where they are powerless will be driven to submission, even madness.

The Stanford Prison Experiment has been included in many, many introductory psychology textbooks and is often cited uncritically . It’s the subject of movies, documentaries, books, television shows, and congressional testimony .

But its findings were wrong. Very wrong. And not just due to its questionable ethics or lack of concrete data — but because of deceit.

- Philip Zimbardo defends the Stanford Prison Experiment, his most famous work

A new exposé published by Medium based on previously unpublished recordings of Philip Zimbardo, the Stanford psychologist who ran the study, and interviews with his participants, offers convincing evidence that the guards in the experiment were coached to be cruel. It also shows that the experiment’s most memorable moment — of a prisoner descending into a screaming fit, proclaiming, “I’m burning up inside!” — was the result of the prisoner acting. “I took it as a kind of an improv exercise,” one of the guards told reporter Ben Blum . “I believed that I was doing what the researchers wanted me to do.”

The findings have long been subject to scrutiny — many think of them as more of a dramatic demonstration , a sort-of academic reality show, than a serious bit of science. But these new revelations incited an immediate response. “We must stop celebrating this work,” personality psychologist Simine Vazire tweeted , in response to the article . “It’s anti-scientific. Get it out of textbooks.” Many other psychologists have expressed similar sentiments.

( Update : Since this article published, the journal American Psychologist has published a thorough debunking of the Stanford Prison Experiment that goes beyond what Blum found in his piece. There’s even more evidence that the “guards” knew the results that Zimbardo wanted to produce, and were trained to meet his goals. It also provides evidence that the conclusions of the experiment were predetermined.)

Many of the classic show-stopping experiments in psychology have lately turned out to be wrong, fraudulent, or outdated. And in recent years, social scientists have begun to reckon with the truth that their old work needs a redo, the “ replication crisis .” But there’s been a lag — in the popular consciousness and in how psychology is taught by teachers and textbooks. It’s time to catch up.

Many classic findings in psychology have been reevaluated recently

The Zimbardo prison experiment is not the only classic study that has been recently scrutinized, reevaluated, or outright exposed as a fraud. Recently, science journalist Gina Perry found that the infamous “Robbers Cave“ experiment in the 1950s — in which young boys at summer camp were essentially manipulated into joining warring factions — was a do-over from a failed previous version of an experiment, which the scientists never mentioned in an academic paper. That’s a glaring omission. It’s wrong to throw out data that refutes your hypothesis and only publicize data that supports it.

Perry has also revealed inconsistencies in another major early work in psychology: the Milgram electroshock test, in which participants were told by an authority figure to deliver seemingly lethal doses of electricity to an unseen hapless soul. Her investigations show some evidence of researchers going off the study script and possibly coercing participants to deliver the desired results. (Somewhat ironically, the new revelations about the prison experiment also show the power an authority figure — in this case Zimbardo himself and his “warden” — has in manipulating others to be cruel.)

- The Stanford Prison Experiment is based on lies. Hear them for yourself.

Other studies have been reevaluated for more honest, methodological snafus. Recently, I wrote about the “marshmallow test,” a series of studies from the early ’90s that suggested the ability to delay gratification at a young age is correlated with success later in life . New research finds that if the original marshmallow test authors had a larger sample size, and greater research controls, their results would not have been the showstoppers they were in the ’90s. I can list so many more textbook psychology findings that have either not replicated, or are currently in the midst of a serious reevaluation.

- Social priming: People who read “old”-sounding words (like “nursing home”) were more likely to walk slowly — showing how our brains can be subtly “primed” with thoughts and actions.

- The facial feedback hypothesis: Merely activating muscles around the mouth caused people to become happier — demonstrating how our bodies tell our brains what emotions to feel.

- Stereotype threat: Minorities and maligned social groups don’t perform as well on tests due to anxieties about becoming a stereotype themselves.

- Ego depletion: The idea that willpower is a finite mental resource.

Alas, the past few years have brought about a reckoning for these ideas and social psychology as a whole.

Many psychological theories have been debunked or diminished in rigorous replication attempts. Psychologists are now realizing it’s more likely that false positives will make it through to publication than inconclusive results. And they’ve realized that experimental methods commonly used just a few years ago aren’t rigorous enough. For instance, it used to be commonplace for scientists to publish experiments that sampled about 50 undergraduate students. Today, scientists realize this is a recipe for false positives , and strive for sample sizes in the hundreds and ideally from a more representative subject pool.

Nevertheless, in so many of these cases, scientists have moved on and corrected errors, and are still doing well-intentioned work to understand the heart of humanity. For instance, work on one of psychology’s oldest fixations — dehumanization, the ability to see another as less than human — continues with methodological rigor, helping us understand the modern-day maltreatment of Muslims and immigrants in America.

In some cases, time has shown that flawed original experiments offer worthwhile reexamination. The original Milgram experiment was flawed. But at least its study design — which brings in participants to administer shocks (not actually carried out) to punish others for failing at a memory test — is basically repeatable today with some ethical tweaks.

And it seems like Milgram’s conclusions may hold up: In a recent study, many people found demands from an authority figure to be a compelling reason to shock another. However, it’s possible, due to something known as the file-drawer effect, that failed replications of the Milgram experiment have not been published. Replication attempts at the Stanford prison study, on the other hand, have been a mess .

In science, too often, the first demonstration of an idea becomes the lasting one — in both pop culture and academia. But this isn’t how science is supposed to work at all!

Science is a frustrating, iterative process. When we communicate it, we need to get beyond the idea that a single, stunning study ought to last the test of time. Scientists know this as well, but their institutions have often discouraged them from replicating old work, instead of the pursuit of new and exciting, attention-grabbing studies. (Journalists are part of the problem too , imbuing small, insignificant studies with more importance and meaning than they’re due.)

Thankfully, there are researchers thinking very hard, and very earnestly, on trying to make psychology a more replicable, robust science. There’s even a whole Society for the Improvement of Psychological Science devoted to these issues.

Follow-up results tend to be less dramatic than original findings , but they are more useful in helping discover the truth. And it’s not that the Stanford Prison Experiment has no place in a classroom. It’s interesting as history. Psychologists like Zimbardo and Milgram were highly influenced by World War II. Their experiments were, in part, an attempt to figure out why ordinary people would fall for Nazism. That’s an important question, one that set the agenda for a huge amount of research in psychological science, and is still echoed in papers today.

Textbooks need to catch up

Psychology has changed tremendously over the past few years. Many studies used to teach the next generation of psychologists have been intensely scrutinized, and found to be in error. But troublingly, the textbooks have not been updated accordingly .

That’s the conclusion of a 2016 study in Current Psychology. “ By and large,” the study explains (emphasis mine):

introductory textbooks have difficulty accurately portraying controversial topics with care or, in some cases, simply avoid covering them at all. ... readers of introductory textbooks may be unintentionally misinformed on these topics.

The study authors — from Texas A&M and Stetson universities — gathered a stack of 24 popular introductory psych textbooks and began looking for coverage of 12 contested ideas or myths in psychology.

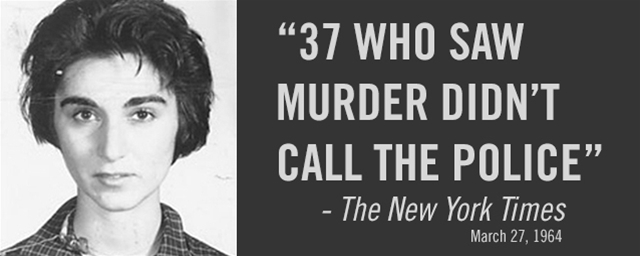

The ideas — like stereotype threat, the Mozart effect , and whether there’s a “narcissism epidemic” among millennials — have not necessarily been disproven. Nevertheless, there are credible and noteworthy studies that cast doubt on them. The list of ideas also included some urban legends — like the one about the brain only using 10 percent of its potential at any given time, and a debunked story about how bystanders refused to help a woman named Kitty Genovese while she was being murdered.

The researchers then rated the texts on how they handled these contested ideas. The results found a troubling amount of “biased” coverage on many of the topic areas.

But why wouldn’t these textbooks include more doubt? Replication, after all, is a cornerstone of any science.

One idea is that textbooks, in the pursuit of covering a wide range of topics, aren’t meant to be authoritative on these individual controversies. But something else might be going on. The study authors suggest these textbook authors are trying to “oversell” psychology as a discipline, to get more undergraduates to study it full time. (I have to admit that it might have worked on me back when I was an undeclared undergraduate.)

There are some caveats to mention with the study: One is that the 12 topics the authors chose to scrutinize are completely arbitrary. “And many other potential issues were left out of our analysis,” they note. Also, the textbooks included were printed in the spring of 2012; it’s possible they have been updated since then.

Recently, I asked on Twitter how intro psychology professors deal with inconsistencies in their textbooks. Their answers were simple. Some say they decided to get rid of textbooks (which save students money) and focus on teaching individual articles. Others have another solution that’s just as simple: “You point out the wrong, outdated, and less-than-replicable sections,” Daniël Lakens , a professor at Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands, said. He offered a useful example of one of the slides he uses in class.

Anecdotally, Illinois State University professor Joe Hilgard said he thinks his students appreciate “the ‘cutting-edge’ feeling from knowing something that the textbook didn’t.” (Also, who really, earnestly reads the textbook in an introductory college course?)

And it seems this type of teaching is catching on. A (not perfectly representative) recent survey of 262 psychology professors found more than half said replication issues impacted their teaching . On the other hand, 40 percent said they hadn’t. So whether students are exposed to the recent reckoning is all up to the teachers they have.

If it’s true that textbooks and teachers are still neglecting to cover replication issues, then I’d argue they are actually underselling the science. To teach the “replication crisis” is to teach students that science strives to be self-correcting. It would instill in them the value that science ought to be reproducible.

Understanding human behavior is a hard problem. Finding out the answers shouldn’t be easy. If anything, that should give students more motivation to become the generation of scientists who get it right.

“Textbooks may be missing an opportunity for myth busting,” the Current Psychology study’s authors write. That’s, ideally, what young scientist ought to learn: how to bust myths and find the truth.

Further reading: Psychology’s “replication crisis”

- The replication crisis, explained. Psychology is currently undergoing a painful period of introspection. It will emerge stronger than before.

- The “marshmallow test” said patience was a key to success. A new replication tells us s’more.

- The 7 biggest problems facing science, according to 270 scientists

- What a nerdy debate about p-values shows about science — and how to fix it

- Science is often flawed. It’s time we embraced that.

Most Popular

- Georgia’s MAGA elections board is laying the groundwork for an actual stolen election

- Zelenskyy’s new plan to end the war, explained

- Did Ukraine just call Putin’s nuclear bluff?

- Mark Zuckerberg’s letter about Facebook censorship is not what it seems

- How is Kamala Harris getting away with this?

Today, Explained

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

This is the title for the native ad

More in Science

The privately funded venture will test out new aerospace technology.

Scientific fraud kills people. Should it be illegal?

The case against Medicare drug price negotiations doesn’t add up.

But there might be global consequences.

Covid’s summer surge, explained

Japan’s early-warning system shows a few extra seconds can save scores of lives.

10 Psychological Experiments That Could Never Happen Today

Nowadays, the American Psychological Association has a Code of Conduct in place when it comes to ethics in psychological experiments. Experimenters must adhere to various rules pertaining to everything from confidentiality to consent to overall beneficence. Review boards are in place to enforce these ethics. But the standards were not always so strict, which is how some of the most famous studies in psychology came about.

1. The Little Albert Experiment

At Johns Hopkins University in 1920, John B. Watson conducted a study of classical conditioning, a phenomenon that pairs a conditioned stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus until they produce the same result. This type of conditioning can create a response in a person or animal towards an object or sound that was previously neutral. Classical conditioning is commonly associated with Ivan Pavlov, who rang a bell every time he fed his dog until the mere sound of the bell caused his dog to salivate.

Watson tested classical conditioning on a 9-month-old baby he called Albert B. The young boy started the experiment loving animals, particularly a white rat. Watson started pairing the presence of the rat with the loud sound of a hammer hitting metal. Albert began to develop a fear of the white rat as well as most animals and furry objects. The experiment is considered particularly unethical today because Albert was never desensitized to the phobias that Watson produced in him. (The child died of an unrelated illness at age 6, so doctors were unable to determine if his phobias would have lasted into adulthood.)

2. Asch Conformity Experiments

Solomon Asch tested conformity at Swarthmore College in 1951 by putting a participant in a group of people whose task was to match line lengths. Each individual was expected to announce which of three lines was the closest in length to a reference line. But the participant was placed in a group of actors, who were all told to give the correct answer twice then switch to each saying the same incorrect answer. Asch wanted to see whether the participant would conform and start to give the wrong answer as well, knowing that he would otherwise be a single outlier.

Thirty-seven of the 50 participants agreed with the incorrect group despite physical evidence to the contrary. Asch used deception in his experiment without getting informed consent from his participants, so his study could not be replicated today.

3. The Bystander Effect

Some psychological experiments that were designed to test the bystander effect are considered unethical by today’s standards. In 1968, John Darley and Bibb Latané developed an interest in crime witnesses who did not take action. They were particularly intrigued by the murder of Kitty Genovese , a young woman whose murder was witnessed by many, but still not prevented.

The pair conducted a study at Columbia University in which they would give a participant a survey and leave him alone in a room to fill out the paper. Harmless smoke would start to seep into the room after a short amount of time. The study showed that the solo participant was much faster to report the smoke than participants who had the exact same experience, but were in a group.

The studies became progressively unethical by putting participants at risk of psychological harm. Darley and Latané played a recording of an actor pretending to have a seizure in the headphones of a person, who believed he or she was listening to an actual medical emergency that was taking place down the hall. Again, participants were much quicker to react when they thought they were the sole person who could hear the seizure.

4. The Milgram Experiment

Yale psychologist Stanley Milgram hoped to further understand how so many people came to participate in the cruel acts of the Holocaust. He theorized that people are generally inclined to obey authority figures, posing the question , “Could it be that Eichmann and his million accomplices in the Holocaust were just following orders? Could we call them all accomplices?” In 1961, he began to conduct experiments of obedience.

Participants were under the impression that they were part of a study of memory . Each trial had a pair divided into “teacher” and “learner,” but one person was an actor, so only one was a true participant. The drawing was rigged so that the participant always took the role of “teacher.” The two were moved into separate rooms and the “teacher” was given instructions. He or she pressed a button to shock the “learner” each time an incorrect answer was provided. These shocks would increase in voltage each time. Eventually, the actor would start to complain followed by more and more desperate screaming. Milgram learned that the majority of participants followed orders to continue delivering shocks despite the clear discomfort of the “learner.”

Had the shocks existed and been at the voltage they were labeled, the majority would have actually killed the “learner” in the next room. Having this fact revealed to the participant after the study concluded would be a clear example of psychological harm.

5. Harlow’s Monkey Experiments

In the 1950s, Harry Harlow of the University of Wisconsin tested infant dependency using rhesus monkeys in his experiments rather than human babies. The monkey was removed from its actual mother which was replaced with two “mothers,” one made of cloth and one made of wire. The cloth “mother” served no purpose other than its comforting feel whereas the wire “mother” fed the monkey through a bottle. The monkey spent the majority of his day next to the cloth “mother” and only around one hour a day next to the wire “mother,” despite the association between the wire model and food.

Harlow also used intimidation to prove that the monkey found the cloth “mother” to be superior. He would scare the infants and watch as the monkey ran towards the cloth model. Harlow also conducted experiments which isolated monkeys from other monkeys in order to show that those who did not learn to be part of the group at a young age were unable to assimilate and mate when they got older. Harlow’s experiments ceased in 1985 due to APA rules against the mistreatment of animals as well as humans . However, Department of Psychiatry Chair Ned H. Kalin, M.D. of the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health has recently begun similar experiments that involve isolating infant monkeys and exposing them to frightening stimuli. He hopes to discover data on human anxiety, but is meeting with resistance from animal welfare organizations and the general public.

6. Learned Helplessness

The ethics of Martin Seligman’s experiments on learned helplessness would also be called into question today due to his mistreatment of animals. In 1965, Seligman and his team used dogs as subjects to test how one might perceive control. The group would place a dog on one side of a box that was divided in half by a low barrier. Then they would administer a shock, which was avoidable if the dog jumped over the barrier to the other half. Dogs quickly learned how to prevent themselves from being shocked.

Seligman’s group then harnessed a group of dogs and randomly administered shocks, which were completely unavoidable. The next day, these dogs were placed in the box with the barrier. Despite new circumstances that would have allowed them to escape the painful shocks, these dogs did not even try to jump over the barrier; they only cried and did not jump at all, demonstrating learned helplessness.

7. Robbers Cave Experiment

Muzafer Sherif conducted the Robbers Cave Experiment in the summer of 1954, testing group dynamics in the face of conflict. A group of preteen boys were brought to a summer camp, but they did not know that the counselors were actually psychological researchers. The boys were split into two groups, which were kept very separate. The groups only came into contact with each other when they were competing in sporting events or other activities.

The experimenters orchestrated increased tension between the two groups, particularly by keeping competitions close in points. Then, Sherif created problems, such as a water shortage, that would require both teams to unite and work together in order to achieve a goal. After a few of these, the groups became completely undivided and amicable.

Though the experiment seems simple and perhaps harmless, it would still be considered unethical today because Sherif used deception as the boys did not know they were participating in a psychological experiment. Sherif also did not have informed consent from participants.

8. The Monster Study

At the University of Iowa in 1939, Wendell Johnson and his team hoped to discover the cause of stuttering by attempting to turn orphans into stutterers. There were 22 young subjects, 12 of whom were non-stutterers. Half of the group experienced positive teaching whereas the other group dealt with negative reinforcement. The teachers continually told the latter group that they had stutters. No one in either group became stutterers at the end of the experiment, but those who received negative treatment did develop many of the self-esteem problems that stutterers often show. Perhaps Johnson’s interest in this phenomenon had to do with his own stutter as a child , but this study would never pass with a contemporary review board.

Johnson’s reputation as an unethical psychologist has not caused the University of Iowa to remove his name from its Speech and Hearing Clinic .

9. Blue Eyed versus Brown Eyed Students

Jane Elliott was not a psychologist, but she developed one of the most famously controversial exercises in 1968 by dividing students into a blue-eyed group and a brown-eyed group. Elliott was an elementary school teacher in Iowa, who was trying to give her students hands-on experience with discrimination the day after Martin Luther King Jr. was shot, but this exercise still has significance to psychology today. The famous exercise even transformed Elliott’s career into one centered around diversity training.

After dividing the class into groups, Elliott would cite phony scientific research claiming that one group was superior to the other. Throughout the day, the group would be treated as such. Elliott learned that it only took a day for the “superior” group to turn crueler and the “inferior” group to become more insecure. The blue eyed and brown eyed groups then switched so that all students endured the same prejudices.

Elliott’s exercise (which she repeated in 1969 and 1970) received plenty of public backlash, which is probably why it would not be replicated in a psychological experiment or classroom today. The main ethical concerns would be with deception and consent, though some of the original participants still regard the experiment as life-changing .

10. The Stanford Prison Experiment

In 1971, Philip Zimbardo of Stanford University conducted his famous prison experiment, which aimed to examine group behavior and the importance of roles. Zimbardo and his team picked a group of 24 male college students who were considered “healthy,” both physically and psychologically. The men had signed up to participate in a “ psychological study of prison life ,” which would pay them $15 per day. Half were randomly assigned to be prisoners and the other half were assigned to be prison guards. The experiment played out in the basement of the Stanford psychology department where Zimbardo’s team had created a makeshift prison. The experimenters went to great lengths to create a realistic experience for the prisoners, including fake arrests at the participants’ homes.

The prisoners were given a fairly standard introduction to prison life, which included being deloused and assigned an embarrassing uniform. The guards were given vague instructions that they should never be violent with the prisoners, but needed to stay in control. The first day passed without incident, but the prisoners rebelled on the second day by barricading themselves in their cells and ignoring the guards. This behavior shocked the guards and presumably led to the psychological abuse that followed. The guards started separating “good” and “bad” prisoners, and doled out punishments including push ups, solitary confinement, and public humiliation to rebellious prisoners.

Zimbardo explained , “In only a few days, our guards became sadistic and our prisoners became depressed and showed signs of extreme stress.” Two prisoners dropped out of the experiment; one eventually became a psychologist and a consultant for prisons . The experiment was originally supposed to last for two weeks, but it ended early when Zimbardo’s future wife, psychologist Christina Maslach, visited the experiment on the fifth day and told him , “I think it’s terrible what you’re doing to those boys.”

Despite the unethical experiment, Zimbardo is still a working psychologist today. He was even honored by the American Psychological Association with a Gold Medal Award for Life Achievement in the Science of Psychology in 2012 .

Another 14 Iconic Psychology Experiments Have Failed Replication Attempts

A lot of what we think we know about psychology might be wrong.

A major research initiative, the second of its kind , tried to reconstruct 28 famous classic psychology experiments.

But of those 28, only 14 of the experiments yielded the same results, according to research published Monday in the journal Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science.

For the past several years, world leaders in psychology research have been scrambling to investigate a looming scandal in their field: many key findings from landmark psychological experiments, in spite of many scientists' best efforts, have never been replicated.

In other words, the insights about the mind uncovered by those experimenters may be totally invalid — but it's difficult to tell who was wrong about what.

That's why many scientists are working to reproduce classic experiments — recreating their conditions and methodologies to see if they arrive at the same results — and reinvestigating the reasons why some studies led to new discoveries and others didn't .

The new paper lays out the 28 studies one after another, comparing and contrasting the original findings with what contemporary scientists discovered.

For example, a 2007 study on the trolley problem held up to scrutiny — just as before, most people found it impermissible to push one person onto the tracks in order to stop a trolley from running over five people.

A common critique of modern psychological research is that participants tend to be WEIRD — a term researchers use to describe subjects who are Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic nations ; many professors recruit undergraduates to participate in their studies.

But this new massive attempt to replicate existing scientific literature, which began back in 2014 and involved over 60 labs around the world, found little difference among different samples or groups of participants.

Failed Exam

When scientists found that they couldn't replicate a study — which, again, happened for half of the experiments they analyzed — they found that they couldn't do so regardless of where they were conducted or who made up the sample pool.

If replicability truly depended on the WEIRDness of the participants, then there would have been a random smattering of successes and failures among different labs.

But because every attempt to reach the same conclusions as those 14 studies failed, it may be that their findings, and things that scientists claimed to have discovered about the human mind, could be totally invalid.

This article was originally published by Futurism . Read the original article .

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

12 reasons research goes wrong.

FIXING THE NUMBERS Massaging data, small sample sizes and other issues can affect the statistical analyses of studies and distort the results, and that's not all that can go wrong.

Justine Hirshfeld/ Science News

Share this:

By Tina Hesman Saey

January 13, 2015 at 2:23 pm

For more on reproducibility in science, see SN’s feature “ Is redoing scientific research the best way to find truth? “

Barriers to research replication are based largely in a scientific culture that pits researchers against each other in competition for scarce resources. Any or all of the factors below, plus others, may combine to skew results.

Pressure to publish

Research funds are tighter than ever and good positions are hard to come by. To get grants and jobs, scientists need to publish, preferably in big-name journals. That pressure may lead researchers to publish many low-quality studies instead of aiming for a smaller number of well-done studies. To convince administrators and grant reviewers of the worthiness of their work, scientists have to be cheerleaders for their research; they may not be as critical of their results as they should be.

Impact factor mania

For scientists, publishing in a top journal — such as Nature , Science or Cell — with high citation rates or “impact factors” is like winning a medal. Universities and funding agencies award jobs and money disproportionately to researchers who publish in these journals. Many researchers say the science in those journals isn’t better than studies published elsewhere, it’s just splashier and tends not to reflect the messy reality of real-world data. Mania linked to publishing in high-impact journals may encourage researchers to do just about anything to publish there, sacrificing the quality of their science as a result.

Tainted cultures

Experiments can get contaminated and cells and animals may not be as advertised. In hundreds of instances since the 1960s, researchers misidentified cells they were working with. Contamination led to the erroneous report that the XMRV virus causes chronic fatigue syndrome, and a recent report suggests that bacterial DNA in lab reagents can interfere with microbiome studies.

Do the wrong kinds of statistical analyses and results may be skewed. Some researchers accuse colleagues of “p-hacking,” massaging data to achieve particular statistical criteria. Small sample sizes and improper randomization of subjects or “blinding” of the researchers can also lead to statistical errors. Data-heavy studies require multiple convoluted steps to analyze, with lots of opportunity for error. Researchers can often find patterns in their mounds of data that have no biological meaning.

Sins of omission

To thwart their competition, some scientists may leave out important details. One study found that 54 percent of research papers fail to properly identify resources, such as the strain of animals or types of reagents or antibodies used in the experiments. Intentional or not, the result is the same: Other researchers can’t replicate the results.

Biology is messy

Variability among and between people, animals and cells means that researchers never get exactly the same answer twice. Unknown variables abound and make replicating in the life and social sciences extremely difficult.

Peer review doesn’t work

Peer reviewers are experts in their field who evaluate research manuscripts and determine whether the science is strong enough to be published in a journal. A sting conducted by Science found some journals that don’t bother with peer review, or use a rubber stamp review process. Another study found that peer reviewers aren’t very good at spotting errors in papers. A high-profile case of misconduct concerning stem cells revealed that even when reviewers do spot fatal flaws, journals sometimes ignore the recommendations and publish anyway ( SN: 12/27/14, p. 25 ).

Some scientists don’t share

Collecting data is hard work and some scientists see a competitive advantage to not sharing their raw data. But selfishness also makes it impossible to replicate many analyses, especially those involving expensive clinical trials or massive amounts of data.

Research never reported

Journals want new findings, not repeats or second-place finishers. That gives researchers little incentive to check previously published work or to try to publish those findings if they do. False findings go unchallenged and negative results — ones that show no evidence to support the scientist’s hypothesis — are rarely published. Some people fear that scientists may leave out important, correct results that don’t fit a given hypothesis and publish only experiments that do.

Poor training produces sloppy scientists

Some researchers complain that young scientists aren’t getting proper training to conduct rigorous work and to critically evaluate their own and others’ studies.

Mistakes happen

Scientists are human, and therefore, fallible. Of 423 papers retracted due to honest error between 1979 and 2011, more than half were pulled because of mistakes, such as measuring a drug incorrectly.

Researchers who make up data or manipulate it produce results no one can replicate. However, fraud is responsible for only a tiny fraction of results that can’t be replicated.

More Stories from Science News on Science & Society

A fluffy, orange fungus could transform food waste into tasty dishes

‘Turning to Stone’ paints rocks as storytellers and mentors

Old books can have unsafe levels of chromium, but readers’ risk is low

Astronauts actually get stuck in space all the time

Scientists are getting serious about UFOs. Here’s why

‘Then I Am Myself the World’ ponders what it means to be conscious

Twisters asks if you can 'tame' a tornado. We have the answer

The world has water problems. This book has solutions

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

10 Bizarre Psychology Experiments That Completely Crossed the Line

- Published Apr 11, 2014

- Updated Nov 22, 2023

- In Psychology & Pop Culture

Experimental psychology and psychological experiments can be key to understanding what makes people tick. Cognitive dissonance, false consensus effect, and classical conditioning are important parts of psychological experiments. However, some individuals have gone about their research and famous psychology experiments in rather unusual, and sometimes morally dubious, ways. These researchers’ findings may increase the sum of knowledge on human behavior; however, the methods that a number of psychologists have used in order to test theories have at times overstepped ethical boundaries. Some might even appear somewhat sadistic. Those taking part in such studies have not always escaped unscathed. In fact, as a result some have suffered lasting emotional damage, or worse. Here are ten bizarre psychology experiments that totally crossed the line.

10. Milgram Experiment (1961)

The Milgram Experiment is one of the controversial experiments. Yale University social psychology professor Stanley Milgram embarked on his now infamous series of experiments in 1961. Prompted by the trial of high-ranking Nazi and Holocaust-coordinator Adolf Eichmann, Milgram wished to assess whether people really would carry out acts that clashed with their conscience if so directed by an authority figure. For each test, Milgram lined up three people, who were split into the roles of “experimenter” (or authority figure), “teacher” and “learner” (actually an actor). After that, the teacher was separated from the learner. They were then told to comply with the experimenter. The teacher would attempt to tutor the learner in sets of word pairs. The penalty for wrong answers by the learner was shocking in more ways than one. The learner pretended to receive painful and increasingly strong jolts of electricity that the teacher thought they were delivering. Even though no real shocks were inflicted, the ethics of the experiment came under close scrutiny owing to the severe psychological stress placed on its volunteer subjects.

9. Little Albert Experiment (1920)

The Little Albert Experiment is one of the psychological experiments gone wrong . Things were different in 1920. Back then, you could take a healthy baby and scare it silly in the name of science. That is exactly what American social psychologist John B. Watson did at Johns Hopkins University. Watson was interested to learn if he would be able to condition a child to fear something ordinary. He coupled it with something else that he supposed triggered inborn fear. Watson borrowed eight-month-old baby Albert for an unethical psychological experiment. First, Watson introduced the child to a white rat. Observing that it didn’t scare Albert, Watson then reintroduced the rat, only this time together with a sudden loud noise. Naturally, the noise frightened Albert. Watson then deliberately got Albert to associate the rat with the noise, until the baby couldn’t even see the rat without bursting into tears. Essentially, the psychologist gave Albert a pretty unpleasant phobia. Moreover, Watson went on to make the infant distressed when seeing a rabbit, a dog, and even the furry white beard of Santa Claus. By the end of the experiment, Albert might well have been traumatized for life!

8. Stanford Prison Experiment (1971)

In August 1971 Stanford University psychology professor Philip Zimbardo decided to test the theory that conflict and ill-treatment involving prisoners and prison guards is chiefly down to individuals’ personality traits. This experiment came to be known as the Stanford Prison Experiment. Zimbardo and his team set up a simulated prison in the Stanford psychology building and gave 24 volunteers the roles of either prisoner or guard. The participants were then dressed according to their assigned roles. Zimbardo gave himself the part of superintendent. While Zimbardo had steered the guards towards creating “a sense of powerlessness” among the mock prisoners, what happened was pretty disturbing. Around four of the dozen prison guards became actively sadistic. Prisoners were stripped and humiliated, left in unsanitary conditions and forced to sleep on concrete floors. One was shut in a cupboard. Zimbardo himself was so immersed in his role that he did not notice the severity of what was going on. After six days, his girlfriend’s protests persuaded him to halt the experiment; but, that was not before at least five of the prisoners had suffered emotional trauma.

7. Monkey Drug Trials (1969)

The Monkey Drug Trials is a psychology experiment gone wrong . While their findings may have shed light on the psychological aspect of drug addiction, three researchers at the University of Michigan Medical School arguably completely overstepped the mark in 1969 by getting macaque monkeys hooked on illegal substances. G.A. Deneau, T. Yanagita and M.H. Seevers injected the primates with drugs. These drugs included cocaine, amphetamines, morphine, LSD, and alcohol. Why? In order to see if the animals would then go on to freely administer doses of the psychoactive and, in some cases, potentially deadly substances themselves. Many of the monkeys did, which the researchers claimed established a link between drug abuse and psychological dependence. Still, given the fact that the conclusions cannot necessarily be applied to humans, the experiment may have had questionable scientific value. Moreover, even if a link was determined, the method was quite possibly unethical and undoubtedly cruel, especially since some of the monkeys became a danger to themselves and died.

6. Bobo Doll Experiment (1961, 1963)

In the early 1960s, Stanford University psychologist Albert Bandura attempted to demonstrate that human behavior can be learned through observation of reward and punishment. To do this, he acquired 72 nursery-age children together with a large, inflatable toy known as a Bobo doll. He then made a subset of the children watch an aggressive model of behavior. An adult violently beat and verbally abused the toy for around ten minutes. Alarmingly, Bandura found that out of the two-dozen children who witnessed this display, in many cases the behavior was imitated. Left alone in the room with the Bobo doll once the adult had gone, the children exposed to the violence became verbally and physically aggressive towards the doll, attacking it with an intensity arguably frightening to see in ones so young. In 1963 Bandura carried out another Bobo doll experiment that yielded similar results. Nevertheless, the psychology research has since come under fire on ethical grounds, seeing as its subjects were basically trained to act aggressively with possible longer-term consequences and not healthy childhood development.

5. Homosexual Aversion Therapy (1967)

Aversion therapy to “cure” homosexuality was once a prominent subject of research at various universities. A study detailing attempts at “treating” one group of 43 homosexual men was published in the British Medical Journal in 1967. The study recounted researchers M.J. MacCulloch and M.P. Feldman’s experiments in aversion therapy at Manchester, U.K.’s Crumpsall Hospital. The participants watched slides of men that they were told to keep looking at for as long as they considered it appealing. After eight seconds of such a slide being shown, however, the test subjects were given an electric shock. Slides showing women were also presented, and the volunteers were able to look at them without any punishment involved. Although the researchers suggested that the trials had some success in “curing” their participants, in 1994 the American Psychological Association deemed homosexual aversion therapy dangerous and ineffective.

4. The Third Wave (1967)

“How was the Holocaust allowed to happen?” It’s one of history’s burning questions. And when Ron Jones, a teacher at Palo Alto’s Cubberley High School, was struggling to answer it for his sophomore students in 1967, he resolved to show them instead. On the first day of his social experiment, Jones created an authoritarian atmosphere in his class, positioning himself as a sort of World War II-style supreme leader. But as the week progressed, Jones’ one-man brand of fascism turned into a school-wide club. Students came up with their own insignia and adopted a Nazi-like salute. They were taught to firmly obey Jones’ commands and become anti-democratic to the core, even “informing” on one another. Jones’ new ideology was dubbed “The Third Wave” and spread like wildfire. By the fourth day, the teacher was concerned that the movement he had unleashed was getting out of hand. He brought the experiment to a halt. On the fifth day, he told the students that they had invoked a similar feeling of supremacy to that of the German people under the Nazi regime. Thankfully, there were no repercussions.

3. UCLA Schizophrenia Medication Experiment (1983–1994)