Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 11 February 2021

Age discrimination in the workplace hurts us all

- Joo Yeoun Suh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1692-5959 1

Nature Aging volume 1 , page 147 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

3 Citations

19 Altmetric

Metrics details

When older workers are discriminated against, everyone is affected. Age discrimination negatively impacts not only individual workers but also their families and the broader economy, argues Joo Yeoun Suh.

As COVID-19 spreads throughout the United States and the rest of the world, the resulting disruptions to the economy mean that it is highly likely the incidence of age discrimination will increase. This may include employers laying off older staff members or not considering older candidates when rehiring. This short-term thinking ignores long-term consequences that will affect people of all ages.

Age discrimination takes an enormous toll on individual workers and their families, but it also has a substantial impact on the economy. According to the AARP’s recent report ‘ The Economic Impact of Age Discrimination ’, bias against older workers cost the US economy an estimated US$850 billion in gross domestic product (GDP), 8.6 million jobs and US$545 billion in lost wages and salaries in 2018 alone.

Meanwhile, previous experience points to an impending surge in age discrimination issues stemming from the current economic downturn. During the 2007–2009 Great Recession, age discrimination complaints related to hiring and firing increased by 3.4% and 1.4% , respectively, in concert with each percentage point increase in monthly unemployment rates. Unfortunately, the contraction the economy is undergoing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic is even worse than that of the Great Recession.

Many older people believe that their age is a disadvantage when looking for a job. Evidence suggests that older job applicants get fewer callbacks than their younger counterparts with comparable resumes, contributing to extended periods of unemployment for many 50-plus jobseekers. This is especially true for women and minoritized racial groups, as incidents of age discrimination in the workplace often intersect with gender and racial discrimination. The reality is that those most likely to be affected by age discrimination are those least able to afford it. Lower-income workers may have fewer options to switch jobs, and historically disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups are more likely than others to feel trapped in their present role.

For months now, we have been seeing the impact of the pandemic on employment, with record-breaking numbers of unemployment claims filed in April and May of 2020 in the US. It is highly likely that age discrimination will persist after the pandemic if employers do not take steps to address it. To counteract these trends, federal and state anti-age discrimination laws must be vigorously enforced. Beyond that, we need to make changes in the way workplaces operate — changes that will help in the near term but will signal a permanent shift as well. Companies should implement robust practices that promote age-diverse work environments, and their workers of all ages should be provided the apprenticeship opportunities they need to thrive in the workplace as they age.

Access to job-protected paid sick leave or paid family leave will help older workers stay employed during the current health and economic crisis. Some states have temporarily broadened access to paid sick leave in response to the virus, and several major companies have taken action to provide their employees with paid sick leave to allow those who feel ill to stay home. Paid family leave is also important if a family member tests positive for COVID-19, potentially creating a need for quarantine and family caregiving.

Employers should consider how to make workplaces truly embrace age diversity and inclusion. They would be wise to do so, even from a business perspective. There are strong economic benefits for businesses to make such changes, including that an age-diverse workforce gives companies more insight into age-diverse marketplaces. AARP’s initiative, ‘ Living, Learning and Earning Longer ’, a collaboration with the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Economic Forum (WEF), advances the business case for age diversity and highlights promising practices from around the world. Efforts to cultivate multigenerational workforces, which span technology training and sharing career experiences and skills, have clear value for employers and employees alike.

If we are to benefit from the value that older workers bring to the workforce, businesses will need to make a serious commitment to concepts like the multigenerational workforce. Global executives are beginning to recognize that multigenerational workforces are key to business growth and success. However, more than half of global companies still do not include age in their company’s diversity and inclusion policy. Clearly more needs to be done to align systems to better respond to the demographics at large. Efforts to do so are necessary to create inclusive workplaces that take active steps to enable employees to realize their full and unique potential.

Company-sponsored programs that promote age diversity and inclusion in tangible ways would have encouraged 60% of those aged 50-plus who retired because of age discrimination to remain in the workforce longer . There is a compelling case for increasing age inclusion in the workforce beyond meeting legal mandates such as the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967. People are living longer and either want or need to continue working. Providing these people with access to incomes ultimately creates a population with the resources to continue consuming and generating impact on the economy. But perceptions that prevent the hiring and advancement of older workers need to shift in order for these benefits to be captured.

This is an astoundingly difficult time for employees and employers alike. As we fight against COVID-19, we must not lose sight of older workers. With the skills and knowledge they’ve acquired over a lifetime, they can make enormous contributions to the work of pushing national and global economies toward recovery.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Thought Leadership, Policy Research and International (PRI), AARP, Washington DC, USA

Joo Yeoun Suh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joo Yeoun Suh .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Suh, J.Y. Age discrimination in the workplace hurts us all. Nat Aging 1 , 147 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-020-00023-1

Download citation

Published : 11 February 2021

Issue Date : February 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-020-00023-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Achieving a three-dimensional longevity dividend.

- Andrew J. Scott

Nature Aging (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

The impact of age stereotypes and age norms on employees’ retirement choices: a neglected aspect of research on extended working lives.

- 1 School of Social Policy, Sociology and Social Research, University of Kent, Canterbury, United Kingdom

- 2 Department of Sociology, VU Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

This article examines how older workers employ internalized age norms and perceptions when thinking about extending their working lives or retirement timing. It draws on semi-structured interviews with employees ( n = 104) and line managers, human resource managers and occupational health specialists ( n = 52) from four organisations in the United Kingdom. Previous research has demonstrated discrimination against older workers but this is a limiting view of the impact that ageism may have in the work setting. Individuals are likely to internalize age norms as older people have lived in social contexts in which negative images of what it means to be “old” are prevalent. These age perceptions are frequently normalized (taken for granted) in organisations and condition how people are managed and crucially how they manage themselves . How older workers and managers think and talk about age is another dynamic feature of decision making about retirement with implications for extending working lives. Amongst our respondents it was widely assumed that older age would come with worse health—what is more generally called the decline narrative - which served both as a motivation for individuals to leave employment to maximize enjoyment of their remaining years in good health as well as a motivation for some other individuals to stay employed in order to prevent health problems that might occur from an inactive retirement. Age norms also told some employees they were now “too old” for their job, to change job, for training and/or promotion and that they should leave that “to the younger ones”—what we call a sense of intergenerational disentitlement. The implications of these processes for the extending working lives agenda are discussed.

Introduction

In this article we address how age relations in organisations impact on the willingness of older workers to extend their working lives. Internationally, an important policy phrase has been “live longer, work longer” ( OECD, 2006 ; Street and Ní Léime, 2020 ). Policymakers are trying to stimulate older people to extend their working lives, for example in the context of the United Kingdom (UK) by abolishing mandatory retirement ages, increasing the State Pension Age, and by introducing age discrimination legislation (see e.g., ILC-UK, 2017 , and Lain, 2016 , for an overview). These policies are introduced in response to predicted increased population aging and worries about increasing dependency ratios and the affordability of welfare states. There are various problems with this policy narrative as well as its proposed solutions, including that it appears to be a “one-size-fits-all” approach that ignores the different realities of various groups of older workers (for more detail see e.g., Street and Ní Léime, 2020 ). Another issue is that such policy changes occur in social contexts of considerable ageism.

Ageism is commonplace and embedded at all levels: in public policy narratives when talking about older workers, in popular narratives about baby boomers stealing prosperity from younger generations; in organisational regimes which favor the ideal fit and healthy worker (aka not “the old”) and in workplace banter about older workers being put out to pasture. Although there is a long history of research that shows that negative images of older workers are related to discrimination against these employees (see e.g., Chiu et al., 2001 ; Macnicol, 2006 ; Hurd Clarke and Korotchenko 2016 ; Earl et al., 2018 ), there is less attention to how older workers may themselves make labor market decisions based on internalization of these narratives. Recent reviews have asked for more qualitative research on ageism ( Harris et al., 2018 ) and we seek to begin to address this gap in the literature.

Theoretical Considerations

We are seeking to extend our understanding of various components that are part of ageism. Ageism involves active discrimination, but also stereotyping and age norms. The latter two may operate against people as well as being internalized by those subject to them. It is typical in organisational studies to research ageism as perpetrated by managers against employees (for example, Chui et al., 2001 ; Henkens, 2005 ; for an overview of the workplace literature see Naegele et al., 2018 ). Whilst there is evidence for discriminatory behavior by managers against older (and younger) employees this is a limiting view of the impact that ageism may have in the work setting.

Conceptually we see “age” “as a socially and culturally constructed category” ( Krekula et al., 2018 , p.37; see also Calasanti and Slevin, 2001 ; Calasanti, 2020 ). Regarding older workers, we need to understand how age is constructed and performed in the workplace. Age stereotypes identify what is routinely attributed to particular age groups. Prevalent stereotypes about older workers include that they are “(a) less motivated, (b) generally less willing to participate in training and career development, (c) more resistant and less willing to change, (d) less trusting, (e) less healthy, and (f) more vulnerable to work-family imbalance” ( Ng and Feldman, 2012 , p. 821; see also Posthuma and Campion, 2009 ). In their meta-analysis, Ng and Feldman (2012) only found some evidence for (b), though this does not say why they would be less willing to participate in training and career development. Hurd Clarke and Korotchenko (2016) summarize existing literature as follows: “the research suggests that ageism is often deeply internalized as individuals accept stereotypes that depict later life as a time of poor health, cognitive impairment, dependence, lack of productivity and social disengagement” (p. 1759). Part of this is an internalized health-decline-narrative, which has been referred to as “health pessimism” (see e.g., Brown and Vickerstaff, 2011 ). It has been claimed that because workers themselves believe the stereotypes, many cases of age discrimination go unnoticed ( Laczko and Phillipson, 1990 ). Recent research suggests that stereotypes about motivation, mental and physical health remain very persistent ( Kleissner and Jahn, 2020 ) and age and health perceptions might also have an impact on older workers’ motivations to continue or leave work ( Van der Horst, 2019 ).

Next to age stereotypes, age norms (at which age should you do what?) are also important to take into account. In an employment context, ageist ideas will play out in interpersonal interactions but also institutionally through policies and routine practices ( Martin et al., 2014 ; see also Krekula (2009) on age coding practices). Age norms are frequently normalized (taken for granted) in organisations and condition how people are managed and how they manage themselves. Age norms are related to how people manage themselves because they will inform people’s understanding of their own age and its implications in the work context. Ageism exists through social relations rather than primarily being a characteristic of individual behavior (cf. Van der Horst and Vickerstaff, 2021 :4), which is exemplified by the fact that: “older workers” are only “old” in relation to other presumably “younger workers” and vice versa. The rise of narratives about intergenerational fairness (see Willetts, 2010 ; Wildman et al., 2021 ) may feed into concerns about older workers job blocking younger generations. This may in turn have increased the impact of age norms on labor market considerations in recent years.

Few studies have specifically researched the impact of internalized ageism on older workers but some studies do refer to cases of self-exclusion or what Romaioli and Contarello (2019) in a different context have referred to as a self-sabotage narrative: being “too old for”. Minichiello et al. (2000) show with an Australian sample that “older people may adjust their lives so as to accommodate problems they encounter” and that “older people may simply “drop things out of their life” once access becomes difficult rather than lobby for improved resources” (p. 263), Gaillard and Desmette (2010) showed using a Belgian sample that positive stereotypes of older workers were related to lower early retirement intentions and a higher motivation to learn and develop, and in 2008 that identifying as an “older worker” was related to higher early retirement intentions ( Desmette and Gaillard, 2008 ). Brown and Vickerstaff (2011) suggested that health pessimism may be a factor in retirement planning.

The main aim of this article is a qualitative exploration of the role of internalized age stereotypes and norms in employment decisions of older employees in the United Kingdom. As much is already known about which stereotypes exist, we focus more on how older workers and their managers deploy these stereotypes and age norms when talking about their working lives; we are interested in the social relations of age; how ageism is performed and reproduced through interactions and how this affects thinking about retirement.

Data and Method

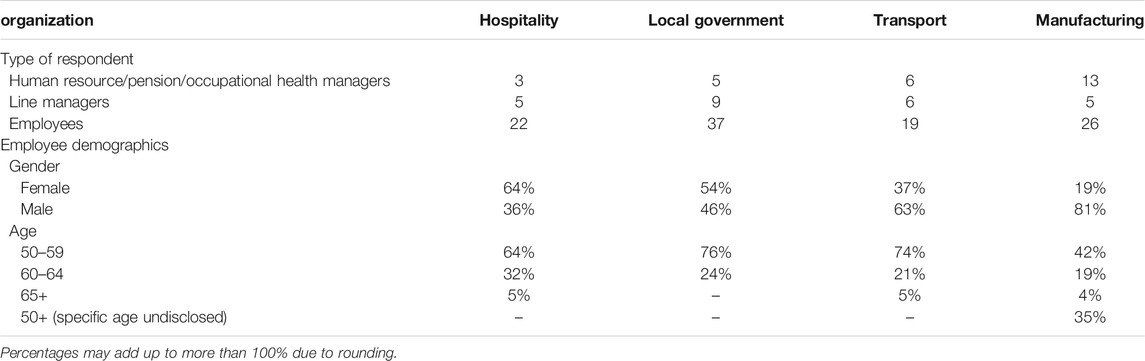

This article is based on individual semi-structured face-to-face employee interviews ( n = 104), as well as interviews with line managers, human resource and occupational health managers ( n = 52) divided over four organizations. The organizations were located in different sectors, with varying workforces, and in different regions in the United Kingdom (the South East, North West, West, Wales and the Home Counties; for further details see Table 1 ). Interviewees were selected out of employees aged 50 or over who volunteered to participate using a maximum variation sampling strategy ( Patton, 1990 ; Flyvbjerg, 2016 ). Managers were selected because they had responsibilities for workforces which included some older workers. In this article we concentrate primarily on the interviews with employees. The data were collected between 2014 and 2016 and interviews were held at the work location during working hours, but in a setting that ensured confidentiality. The average length of interview was between 45 and 50 min, they were digitally recorded, and transcribed verbatim.

TABLE 1 . Number of participants by case study organization and employee details.

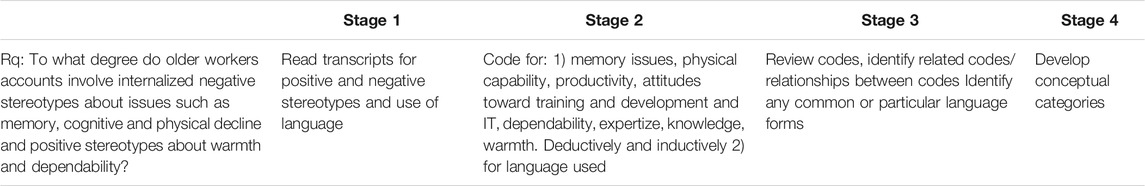

Employees were interviewed about their retirement plans, experiences of age discrimination at work and their views on policy changes around extending working lives. Questions were open ended encouraging respondents to articulate issues salient to them. Interviews with managers centered on how their organisations managed older workers. The focus in this paper is an analysis of how people talk, the language used, about age and ageing. Though the focus of the interviews was not on internalized age norms and how this affected work decisions, these topics emerged in many interviews when people gave their views on changes in policies, experiences at work, and/or their plans for the future. It may be that the data contains many examples of internalized age-stereotypes because it was not directly questioned. Spedale (2018) notes in her study how the identification as “an older worker was predominantly unconscious and informed by age-related hidden assumptions and taken-for-granted beliefs” (p. 41). By identifying age norms and stereotypes when talking about different topics, the data may contain a more “natural” discussion of age at work. The qualitative data were analyzed thematically. An initial deductive coding frame was developed based on the larger project’s research aims and empirical and theoretical interests. In addition, an inductive open coding approach was taken so that themes and issues could arise from the data. After identifying internalized ageism as an emerging theme, the interviews were thematically recoded in NVivo 12 using the framework for analysis in Table 2 and read and reread for comments on the relationship between ageism and employment decisions (on framework analysis see Ritchie et al., 2003 ).

TABLE 2 . Framework for qualitative analysis.

Our approach here is part of the discursive turn in gerontology ( Previtali et al., 2020 ). Through our focus on talk we hope to both expose the ageist narratives in society and in organizations but also to explore how people actively construct their own understandings of reality. Our purpose is not to attempt to replace other explanations of the dynamics of retirement decisions but rather to add another layer to our understanding. The direct quotations from interviews below are selected as indicative for the identified category. Employee interviewees are identified by gender and age; managerial employees by their role.

In all of the organizations the overwhelming majority of employees said there was little direct age discrimination for example in access to training. There were some individuals who felt they had been passed over for opportunities or targeted for redundancy because of their age, but in general employees agreed with managers that their organizations were not overtly ageist.

I’ve not come across any discrimination, other than the banter around your desk kind of thing, you know. (Male, 57).

I get as much abuse as I think we dish out, the old fart in the office, but no I don’t see any different treatment. (Male, age undisclosed).

As these two quotes demonstrate people think of ageism as about direct discrimination and do not see that age stereotypes and norms are embedded in everyday interactions. Both managers and employees regularly employed ageist stereotypes when talking about older workers or about themselves, what we might refer to as casual or normalized ageism. These reflected the standard negative stereotypes about memory issues, physical capability, productivity, attitudes toward training and development and IT:

I’m just cast as a scatty old lady, you know. (Female, 52).

Although people live longer they don’t necessarily—it’s hard to predict at what point they’re no longer going to be really capable of doing their job, to be blunt. (Male, 56).

I suppose might be that some of the older people might be more kind of dinosaurs in terms of technology and slower to pick up the latest, you know, electronic tools and things. (Male, age undisclosed).

There were also more positive stereotypes about dependability, expertise, knowledge, warmth:

I think as you get older you get more of a sense of responsibility. You don’t like letting people down. You tend to work your way round problems rather than think, oh no, I’m not doing this, I’ll go somewhere else. (Female, 61).

You know, when there’s a problem they come running to us first, we’ll get it sorted. Yeah, I suppose I think they do look at it like that, yeah. (Male, 54).

Managers made explicit comparisons between older and younger workers:

I think certain individuals, as they get older and more established in their role, choose not to pick up on every opportunity that’s put before them, but the excitement comes for us as managers for the younger guys who are, “Yeah, what can I do? Give us more, can I do that, can I do this?” and that keeps that process going. […] if the older guys don’t want to pick up on it, it’s not because it’s not available and we would hold it back for them, it’s definitely available but sometimes their attitude or their energy towards it is less so than the guys further down the chain. (Male, 50 interviewed as an employee but with line manager responsibilities)

The prevalence of age based stereotypes was recognized by some employees and to a degree resisted.

Now training, I think it was perceived, and I think it was a wrong perception, that these people had no experience of working on computers, which is completely wrong because those guys like everybody else were going down Tesco’s and Curry’s buying laptops and desktops and playing around on Facebook and YouTube just like everybody else. (Male, 51).

Sometimes it was not the stereotype itself that was resisted, but the degree to which it would apply to them. They considered themselves as not yet “old” as stereotypes about what it means to be “old” did not apply. Many of the employees interviewed said that they did not “feel” their chronological age and felt that they were valued but at the same time many expressed concern about how others might see them or overlook them:

you do become invisible … but it’s like you are cannon fodder in a way, you’re just there to keep the wheels turning. (Female, 57)

Categorizing Talk About Age

Two conceptual categories developed from the analysis of how managers and employees deployed ageist stereotypes and age norms when talking about work opportunities, retirement timing and extending working lives: 1) the prevalence of a decline narrative, namely the widely held assumption that ageing inevitably brings worsening physical and cognitive health, and 2) the prevalence of an intergenerational narrative. The latter had two dimensions: one about being “too old for” something and the second related to intergenerational disentitlement; the need to step away and privilege younger workers.

Both narratives involve a comparison. The decline narrative conditions how people view the implications of getting old and has a role in how they think about continuing or ending work; here people compare themselves with an imagined future self. The intergenerational narrative is how people place themselves in relation to other generations in the workforce, here people compare themselves (and are compared) to others.

Decline Narrative

In discussing future retirement, the health and mortality of colleagues, family, and friends were constant topics leading to something which may be referred to as the decline narrative ( Gullette, 2004 ) or “health pessimism” (cf. Brown and Vickerstaff, 2011 ). This was expressed repeatedly as not knowing when “one’s time is up” or being able to predict how long decent health would last. For many, this expected age related decline in health translated into a desire to retire in time to enjoy some leisure:

One lady, she retired, she was only retired two months and she passed away. And, you know, you think, I don’t want that to be me. And I know you can never say, but I don’t want to work my whole life just to retire and then die. I’d like to enjoy a bit of free time. (Female, 50).

There was a strong sense of not wanting “to run out of time” and instead wanting to “maximize enjoyment of their remaining years in good health” (cf. Pond et al., 2010 ). In relation to the raising of the state pension age in the United Kingdom some felt that policy might force people to work too long, prejudicing their ability to enjoy retirement, this was especially true for those in manual occupations.

I can understand that you shouldn’t have to retire at 65 or whatever age they want to choose, because there’s lots of people perfectly capable of working and they want to, but I do think we’re in danger of keeping people in work who are not fit, because your bodies do start to wear out a bit and the older you get the more susceptible you are to things going wrong and then what are we going to do with those people, what are they going to do? (Female, 58).

For some others the decline narrative worked the other way around and they saw work as a means for staving off the inevitable decline. Paid work was for them a way to stay active and this would be necessary to stay healthy (longer):

Inside I still feel 35 [laughs], shame that the mirror doesn’t agree with me, but [both laugh], yeah, I mean the job is very physical, so but I look on that as being like keep fit, I’m a great believer in use it or lose it, and I think if I’d have given up work at 60 I’d have been a little old lady by now, probably about three stone heavier and gray haired. (Female, 64).

Not all decisions to stop working or extend working life are related to age stereotypes; some look forward to a period in which they have time for hobbies as they are in a financial position to stop working. Others have more negative reasons to give up their job such as health problems and being unable to continue working. Again others are happy to continue working or are not financially able to retire even though they would prefer to. Next to these push and pull factors, which have been identified in previous research, our data does suggest that the decline narrative also plays a role in how people weigh up the factors encouraging or discouraging continued employment. Many employees talked about a fear of being viewed as old and used pejorative language such as “pottering about”, “being a dinosaur”, “doddery” in describing other older people or their future selves.

Intergenerational Narrative

A second narrative expressed by some of our interviewees is about comparisons between age-groups in the labor market. The interviewees are comparing themselves with younger workers and either consider themselves as now “too old” for certain opportunities, or younger workers more worthy for these opportunities. This comparison can be made implicitly or explicitly. The first dimension of this narrative is the “too old for” (TOF)-narrative, which is based on an implicit comparison, where the older worker now considers themselves “too old for” their job or development:

I’ve spoken to other people and they’ve said it’s a young person’s game. […] multitasking in your head and you’ve got three—, no, 20, 30, 40 tickets coming through and you’re trying to mentally keep hold of it all. […] I’m not a woman I can’t multitask (both laugh). So it would be very hard to keep on doing that. (Male, 52)

TOF was most clearly and commonly expressed in relation to training:

I just feel at 60 now, is that really too old for me to be able to, you know, go on all these courses? And there’s quite a few that they want me to do. (Female, 59).

In the TOF-narrative the younger “other” is implicit. But other times intergenerational comparisons are made more explicitly. Many believed that in straightforward competition organizations preferred younger over older workers and that once you are over 50 opportunities in the labor market diminish markedly:

I continually look online, in the papers, I look in places, but when you are 57 and there’s a 30 year old applying for the same job, they’re not going to take me, are they? They’re not. (Female, 57).

Whilst the lack of opportunities for older people was lamented there was a very strong feeling among many of the interviewees that rising state pension ages and the urge to extend working lives was bad for younger generations:

Give the young people who are out there a chance to get into work, because there’s a lot of people unemployed. And I think the longer we go on, the less chance there is for them to get into work, because there’s less people retiring. That’s how I look at it any road. That’s my point of view. (Male, 60).

I actually have a problem with people working longer cause—, guilt’s not the right word, but there are lots of young people who can’t get jobs, you know. (Male, 69).

A number of employees thought that it was right that opportunities should go to younger people. Age norms were internalized by older workers who expressed the view that they were now ”too old” for training and/or promotion and that they should leave that “to the younger ones”:

I’m not particularly after getting promoted, I’ll leave that for the younger ones. I’m just happy where I am and for me I would rather be in this kind of job. (Female, 56).

I don’t want to improve. I don’t mean I don’t want to improve. I will do what I’m doing. I want to give the chance to the young people. […] I’m very, very sorry, I am not interested. Give the chance to the young people. (Male, 54).

Older workers here are wrestling with it being unfair that older workers may be discriminated against whilst also feeling that they have less entitlement to work when younger groups are unemployed, are still building a career or have young families to support. Many people mentioned their children or grandchildren and how difficult the labor market and work was for them.

With an increasing call for employees to extend their working lives, it is important to explore all the factors that are likely to limit this policy goal. The research reported here focused on a hitherto neglected aspect that of the role of internalized age stereotypes and norms in inhibiting older workers. There is a rich literature on direct discrimination against older workers and to a large extent our managers and employees were thinking about this kind of prejudice in relation to ageism. Age discrimination legislation has been around long enough in the United Kingdom for managers and many employees to know that it is proscribed in law and hence when asked our respondents in the majority said that there was no different treatment based on age.

The language managers used to talk about older workers and the way those older workers framed their own thoughts about, work, extending working lives and retirement tells a rather different story. Age stereotypes were routinely employed with respect to older workers capabilities and potential. Age norms about what was appropriate for different age groups were used to talk about training and development or extending working lives. In this sense ageism was normalized in all of the organizations, taken for granted and to a large extent unexamined. Ageist language did not seem to have the power to shock in the way that overtly racist or sexist language nowadays might.

The decline narrative—that with age comes inevitable physical and cognitive deterioration—was prevalent in how employees talked about extending their working lives and/or retirement. It was a factor in their thinking about the desirability of employment as they aged. This was true for those identifying as in good health as well as those with current health issues. As in other studies many people were concerned to retire early enough to still enjoy some health in retirement ( Pond et al., 2010 ; Brown and Vickerstaff, 2011 ). However, for a minority this decline narrative functioned as an incentive to stay in work as a means of maintaining social and physical activity and staving off the onset of ill-health. This latter view chimed more with the increasingly dominant public narrative of active and healthy aging: that work is good for you and keeps you physically and mentally fit ( Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), 2017 : 9; Moulaert and Biggs, 2012 ; Laliberte Rudman, 2015 ). In doing so of course it still takes the eventual and inevitable decline as its point of departure. The decline narrative has been discussed in the existing literature and our study confirms its ubiquity but we noted that it can play either a positive or a negative role with regard to extending one’s working life.

More distinctive were our findings about the intergenerational narrative. If we conceptualize age as social construct then it focuses attention on the relational aspects of age and how age relations are played out in specific contexts. A rather obvious statement is that older workers are only old in relation to some other younger reference group. However, we could clearly see in the comments of both managers and employees that such comparisons were very much alive in people’s minds. They were employed when they were thinking about career opportunities, training and development or the desirability of extending working lives. This was manifested in the “too old for” narrative, expressing a sense that there is a specific chronology for when things are appropriate in the working life. This is perhaps all the more remarkable in our sample as the majority were in the age category 50–59 (see Table 1 ), with presumably many years still in employment. This self-sabotaging narrative, as Romaioli and Contarello (2019) have characterized it, does lead to older people self-limiting. This means older workers potentially opting out of opportunities that are actually available.

The other dimension of the intergenerational narrative we have dubbed “intergenerational disentitlement”, as there was a strong element in our respondents’ comments that as older workers they were less entitled to training and development and possibly even to a job when compared to younger (potential) colleagues. Here many of our respondents were expressing a tension between a commitment to the fact that age discrimination is unfair and should be resisted whilst nevertheless worrying that by taking a promotion or staying in work they might be denying, by implication a more deserving, younger person. This sense of disentitlement could potentially be an important factor in a situation of redundancies, where both managers and employees may feel that if anyone should go it should be the older workers.

This sense of age-based disqualification for job opportunities might undermine formally equitable processes in the workplace; everyone may be entitled to apply for a job, a redeployment or a promotion but some older workers may define themselves as “too old” or think it should “be left for the younger ones”. Age management policies tend to focus on direct discrimination and formal equality but may do little to tackle underlying and normalized ageism of the sort uncovered here.

Individual decisions about whether to carry on working or retire are as we know complex and constrained. The interaction of health, wealth, marital status, employer action and government policy combine to structure what is possible and what is desirable ( Vickerstaff, 2006 ; Loretto and Vickerstaff, 2012 ; Hasselhorn and Apt, 2015 ; Lain, 2016 ; Phillipson et al., 2019 ). The study reported here seeks to include in the list of dynamic variables in retirement decision making, a full and rounded sense of the impact of ageism. It has added another layer to our understanding. The power of ageism to influence end of working life actions is not limited to direct discrimination, although this still certainly plays a significant role, it also encompasses normalized and taken for granted assumptions about age norms, what is suitable for different age groups and why, as well as internalized stereotypes about older workers abilities and aptitudes.

Limitations of the Current Research and Suggestions for Future Research

We have to acknowledge a note of caution about the generalizability of our findings. By the standards of much qualitative work we had a quite large and diverse data set. Our employee respondents covered a good spread of occupational levels in diverse organizations and the gender balance of the sample reflected the gender composition of the different organizations, with a slight over-representation of female respondents. With the weight and depth of interview material we were able to triangulate responses and have concentrated on oft repeated themes and tropes. The sample was however ethnically homogeneous with the overwhelming majority of our respondents identifying as white British. A more diverse sample including a range of the black and minority ethnic populations in the United Kingdom might have confirmed our findings or uncovered different ways of talking about age and generations. In this article we have not examined the gender differences in ageist talk but rather concentrated on the expressions and themes common to both genders. Further research could usefully delve into the subtle differences in how women and men talk about and experience age.

Our respondents were also interviewed in a particular time and place. We do not seek to diminish the importance of public policy and organizational contexts in setting parameters for what is possible for older workers. It would be interesting to see similar narrative analyses undertaken in different national contexts to see whether internalized ageism is as strong and has the same dimensions as identified here. It is also the case that public narratives of what is right or expected of older populations are in some flux as we shift progressively from a societal view of retirement as an earned right for a long working life to the duty on older people to carry on contributing to economic life. Individuals, with their own dispositions, life experiences and family contexts are wrestling with these changing new messages as are we as researchers. It would be interesting in further research to try to link more clearly the impact of public narratives about greedy baby boomers, intergenerational inequity and healthy aging on narratives in the workplace.

The Main Contributions of This Research

We have addressed the spirit of this special issue by identifying a new pathway in retirement research methodologically and conceptually. In so doing we have added another layer to our understanding of the factors that are in play in disposing early retirement or later working. Although we cannot specify the weight or percentage contribution internalized ageism plays in decisions about paid work we have highlighted that it cannot be ignored as a factor. Methodologically we have demonstrated that in addition to quantitative analyses, case studies of organizational practice, and assessments of the impacts of public policy changes, we need to look at how people talk and think about age in the work setting. Embodied stereotypes and taken for granted age norms make a profound contribution to individual and organizational practices around extending working lives. Conceptually we have tried to deepen our understanding of ageism in the work place. We extended the narrow and limiting focus on discrimination against older workers to investigate other components of ageism, namely how older workers respond to age stereotypes and age norms in how they manage themselves.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analysed for this study can be found in the UK Data Archive, with reference SN852868. https://beta.ukdataservice.ac.uk/datacatalogue/studies/study?id=852868 .

Ethics Statement

The original data design and protocols received full ethical approval by the University of Kent. Further ethical review and approval was not required for the current study.

Author Contributions

These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

In this paper we use part of the qualitative data from a larger United Kingdom Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) funded project (Ref. MRC/ESRC ES/L002949/1). The original data design and protocols received full ethical approval. For more information on this larger project, please see ILC-UK (2017) , Phillipson et al. (2019) , and Wainwright et al. (2019) . The re-analysis of interviews which forms the basis of this paper was funded by the ESRC (Ref. ES/S00551X/1).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to members of the original research consortium who undertook the interviews: Joanne Crawford; David Lain; Wendy Loretto; Chris Phillipson, Mark Robinson; Sue Shepherd; David Wainwright and Andrew Weyman. We would like to express our gratitude to those who agreed to be interviewed as part of the study.

Brown, P., and Vickerstaff, S. (2011). Health Subjectivities and Labor Market Participation. Res. Aging 33 (5), 529–550. doi:10.1177/0164027511410249

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Calasanti, T. (2020). Brown Slime, the Silver Tsunami, and Apocalyptic Demography: The Importance of Ageism and Age Relations. Social Currents 7 (3), 195–211. doi:10.1177/2329496520912736

Calasanti, T., and Slevin, K. (2001). Gender, Social Inequalities and Aging . Walnut Greek, CA: AltaMira Press .

Chiu, W. C. K., Chan, A. W., Snape, E., and Redman, T. (2001). Age Stereotypes and Discriminatory Attitudes towards Older Workers: An East-West Comparison. Hum. Relations 54 (5), 629–661. doi:10.1177/0018726701545004

Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) (2017). Fuller Working Lives A Partnership Approach . London: DWP .

Desmette, D., and Gaillard, M. (2008). When a "worker" Becomes an "older Worker". Career Dev. Int. 13 (2), 168–185. doi:10.1108/13620430810860567

Earl, C., Taylor, P., and Cannizzo, F. (2018). "Regardless of Age": Australian University Managers' Attitudes and Practices towards Older Academics. Aging Retirement 4 (3), 300–313. doi:10.1093/workar/wax024

Flyvbjerg, B. (2016). Five Misunderstandings about Case-Study Research. Qual. Inq. 12 (2), 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363

Gaillard, M., and Desmette, D. (2010). (In)validating Stereotypes about Older Workers Influences Their Intentions to Retire Early and to Learn and Develop. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. , 32 (1), 86–98. doi:10.1080/01973530903435763

Gullette, M. M. (2004). Aged by Culture . London: University of Chicago Press .

Harris, K., Krygsman, S., Waschenko, J., and Laliberte Rudman, D. (2018). Ageism and the Older Worker: A Scoping Review. Geront 58 (2), gnw194–e14. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw194

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Hasselhorn, H. M., and Apt, W. (2015). Understanding Employment Participation of Older Workers: Creating a Knowledge Base for Future Labour Market Challenges . Berlin: Research ReportFederal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (BMAS) and Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (BAuA) .

Henkens, K. (2005). Stereotyping Older Workers and Retirement: The Managers' Point of View. Can. J. Aging 24 (4), 353–366. doi:10.1353/cja.2006.0011

Hurd Clarke, L., and Korotchenko, A. (2016). 'I Know it Exists … but I haven't Experienced it Personally': Older Canadian Men's Perceptions of Ageism as a Distant Social Problem. Ageing Soc. 36 (8). 1757–1773. doi:10.1017/S0144686X15000689

ILC-UK (2017). Exploring Retirement Transitions: A Research Report from ILC-UK and the Uncertain Futures Research Consortium . London: ILC-UK Available at https://ilcuk.org.uk/exploring-retirement-transitions/ (Accessed June 3, 2020).

Kleissner, V., and Jahn, G. (2020). Dimensions of Work-Related Age Stereotypes and In-Group Favoritism. Res. Aging 42 (3-4), 126–136. doi:10.1177/0164027519896189

Krekula, C. (2009). Age Coding: On Age-Based Practices of Distinction. Int. J. Ageing Later Life 4 (2), 7–31. doi:10.3384/ijal.1652-8670.09427

Krekula, C., Nikander, P., and Wilińska, M. (2018). “Multiple Marginalizations Based on Age: Gendered Ageism and beyond,” in Contemporary Perspectives On Ageism , International Perspectives on Aging 19 . Editors L. Ayalon, and C. Tesch-Römer (Berlin: Springer Open ), 33–50. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8_3

Laczko, F., and Phillipson, C. (1990). “Defending the Right to Work. Age Discrimination in Employment,” in Age: The Unrecognised Discrimination: Views to Provoke a Debate . Editor E. McEwen (London: Age Concern England ), 84–96.

Google Scholar

Lain, D. (2016). Reconstructing Retirement: Work and Welfare in the UK and USA . Bristol: Policy Press . doi:10.2307/j.ctt1t898mw

CrossRef Full Text

LaliberteRudman, D. (2015). Embodying Positive Aging and Neoliberal Rationality: Talking about the Aging Body within Narratives of Retirement. J. Aging Stud. 34, 10–20. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2015.03.005

Loretto, W., and Vickerstaff, S. (2013). The Domestic and Gendered Context for Retirement. Hum. Relations 66 (1), 65–86. doi:10.1177/0018726712455832

Macnicol, J. (2006). Age Discrimination: An Historical and Contemporary Analysis . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press . doi:10.1017/cbo9780511550560

Martin, G., Dymock, D., Billett, S., and Johnson, G. (2014). In the Name of Meritocracy: Managers' Perceptions of Policies and Practices for Training Older Workers. Ageing Soc. 34, 992–1018. doi:10.1017/S0144686X12001432

Minichiello, V., Browne, J., and Kendig, H. (2000). Perceptions and Consequences of Ageism: Views of Older people. Ageing Soc. 20 (3). 253–278. doi:10.1017/S0144686X99007710

Moulaert, T., and Biggs, S. (2012). International and European Policy on Work and Retirement: Reinventing Critical Perspectives on Active Ageing and Mature Subjectivity. Hum. Relations 66 (1), 23–43. doi:10.1177/0018726711435180

Naegele, L., De Tavernier, W., and Hess, M. (2018). “Work Environment and the Origin of Ageism,” in Contemporary Perspectives On Ageism, International Perspectives on Aging 19 . Editors L. Ayalon, and C. Tesch-Römer ( Springer Open ). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8_3

Ng, T. W. H., and Feldman, D. C. (2012). Evaluating Six Common Stereotypes about Older Workers with Meta-Analytical Data. Personnel Psychol. 65 (4), 821–858. doi:10.1111/peps.12003

OECD (2006). Ageing And Employment policies . Live Longer Work Longer . Paris: OECD Publications .

Patton, M. (1990). Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods . 2nd edition. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage .

Phillipson, C., Shepherd, S., Robinson, M., and Vickerstaff, S. (2019). Uncertain Futures: Organisational Influences on the Transition from Work to Retirement. Soc. Pol. Soc. 18 (3), 335–350. doi:10.1017/S1474746418000180

Pond, R., Stephens, C., and Alpass, F. (2010). How Health Affects Retirement Decisions: Three Pathways Taken by Middle-Older Aged New Zealanders. Ageing Soc. 30 (3). 527–545. doi:10.1017/S0144686X09990523

Posthuma, R. A., and Campion, M. A. (2009). Age Stereotypes in the Workplace: Common Stereotypes, Moderators, and Future Research Directions†. J. Manage. 35 (1), 158–188. doi:10.1177/0149206308318617

Previtali, F., Keskinen, K., Niska, M., and Nikander, P. (2020). Ageism in Working Life: A Scoping Review on Discursive Approaches. Gerontologis 23, 121. doi:10.1093/geront/gnaa119

Ritchie, J., Spencer, K., and O’Connor, L. (2003). “Carrying Out Qualitative Analysis,” in Qualitative Research Practice . Editors J. Richie, and J. Lewis (London: Sage Publications ), 219–262.

Romaioli, D., and Contarello, A. (2019). “I’m Too Old for …” Looking into a Self-Sabotage Rhetoric and its Counter-narratives in an Italian Setting. J. Aging Stud. 48, 25–32. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2018.12.001

Spedale, S. (2018). Deconstructing the 'older Worker': Exploring the Complexities of Subject Positioning at the Intersection of Multiple Discourses. Organization 26 (1), 38–54. doi:10.1177/1350508418768072

Street, D., and Ní Léime, Á. Á. (2020). “Problems and Prospects for Current Policies to Extend Working Lives,” in Extended Working Life Policies: International Gender and Health Perspectives . Editors J. Ogg, M. Rašticová, D. Street, C. Krekula, M. Bédiováet al. (Cham, Switzerland: Springer Open ), 85–113. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-40985-2_5

Van der Horst, M. (2019). Internalised Ageism and Self-Exclusion: Does Feeling Old and Health Pessimism Make Individuals Want to Retire Early?. Soc. Inclusion 7 (3), 27–43. doi:10.17645/si.v7i3.1865

Van der Horst, M., and Vickerstaff, S. (2021). Is Part of Ageism Actually Ableism? Ageing Soc. 12, 1–12. doi:10.1017/S0144686X20001890

Vickerstaff, S. (2006). 'I'd rather Keep Running to the End and Then Jump off the Cliff'. Retirement Decisions: Who Decides? J. Soc. Pol. 35 (3), 455–472. doi:10.1017/S0047279406009871

Wainwright, D., Crawford, J., Loretto, W., Phillipson, C., Robinson, M., Shepherd, S., et al. (2019). Extending Working Life and the Management of Change. Is the Workplace Ready for the Ageing Worker? Ageing Soc. 39 (11), 2397–2419. doi:10.1017/S0144686X18000569

Wildman, J. M., Goulding, A., Moffatt, S., Scharf, T., and Stenning, A. (2021). Intergenerational Equity, equality and Reciprocity in Economically and Politically Turbulent Times: Narratives from across Generations. Ageing Soc. 18, 1–20. doi:10.1017/S0144686X21000052

Willetts, D. (2010). The Pinch How the Baby Boomers Took Their Children’s Future- and Why They Should Give it Back . London: Atlantic Books . doi:10.4324/9780203834305

Keywords: ageism, age stereotypes, age norms, older workers, extending working lives, qualitative interviews

Citation: Vickerstaff S and Van der Horst M (2021) The Impact of Age Stereotypes and Age Norms on Employees’ Retirement Choices: A Neglected Aspect of Research on Extended Working Lives. Front. Sociol. 6:686645. doi: 10.3389/fsoc.2021.686645

Received: 27 March 2021; Accepted: 12 May 2021; Published: 01 June 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Vickerstaff and Van der Horst. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mariska van der Horst, [email protected]

† These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ageism and Age Discrimination at the Workplace—a Psychological Perspective

- First Online: 27 November 2019

Cite this chapter

- Maria Clara de Paula Couto 4 &

- Klaus Rothermund 4

10k Accesses

11 Citations

We all have heard that the world population in industrialized countries has been—and will be—going through a stark demographic change. Specifically, such a shift in the age structure encompasses a decrease in the proportion of younger people coupled with an increased number of older adults in the population. How this resultant “aging world” affects different spheres of social and economic life has been a topic of discussion for years. The workforce and the labor force participation is one of those spheres that have been marked by changes in the age structure [ 28 , 66 , 67 ]. For example, younger and older adults are now working together as never before, leading organizations to work on strategies to deal with intergenerational tensions and to foster good relations between old and young co-workers. In this regard, questions arise such as what are the consequences of the increasing number of older adults for the work domain. Is it the case that older adults face more challenges in the workplace and in the job market? In this chapter, we address these topics by discussing the impacts of the shift in the age structure in the work context and the associated difficulties faced by older adults in the workplace. The topic of ageism and age discrimination in the workplace, their determinants and consequences, is specially relevant for this chapter.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Older Workers, Stereotypes, and Discrimination in the Context of the Employment Relationship

Time for a Twenty-First Century Understanding of Older Workers, Aging, and Discrimination

Silenced Inequalities: Too Young or Too Old?

Abuladze, L., & Perek- Białas, J. (2018). Measures of ageism in the labour market in international social studies. In L. Ayalon & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism (pp. 461–492). Switzerland: Springer Open. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8 .

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice . Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Google Scholar

Avery, D. R., McKay, P. F., & Wilson, D. C. (2007). Engaging the aging workforce: The relationship between perceived age similarity, satisfaction with coworkers, and employee engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1542–1556. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1542 .

Article Google Scholar

Ayalon, L. (2014). Perceived age, gender, and racial/ethnic discrimination in Europe: Results from the European social survey. Educational Gerontology, 40, 499–517.

Ayalon, L., & Tesch-Römer, C. (2018). Introduction to the section: Ageism—Concept and origins. In L. Ayalon & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism (pp. 1–10). Switzerland: Springer Open. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8 .

Bal, A. C., Reiss, A. E. B., Rudolph, C. W., & Baltes, B. B. (2011). Examining positive and negative perceptions of older workers: A meta-analysis. The journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66, 687–698. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbr056 .

Baltes, M. M., Burgess, R. L., & Stewart, R. B. (1980). Independence and dependence in self-care behaviors in nursing home residents: An operant-observational study. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 3, 489–500.

Baltes, M. M., & Reisenzein, R. (1986). The social world in long-term care institutions: Psychosocial control toward dependency? In M. M. Baltes & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), The psychology of control and aging (pp. 315–343). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Berger, E. D. (2009). Managing age discrimination: An examination of the techniques used when seeking employment. The Gerontologist, 49, 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnp031 .

Brandtstädter, J., & Rothermund, K. (2002). The life-course dynamics of goal pursuit and goal adjustment: A two-process framework. Developmental Review, 22 (1), 117–150. https://doi.org/10.1006/drev.2001.0539 .

Brauer, M., Wasel, W., & Niedenthal, P. (2000). Implicit and explicit components of prejudice. Review of General Psychology, 4 (1), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1037//10S9-2680.4.1.79 .

Bugental, D. B., & Hehman, J. A. (2007). Ageism: A review of research and policy implications. Social Issues and Policy Review, 1, 173–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2007.00007.x .

Butler, R. (1969). Age-Ism: Another form of bigotry. The Gerontologist, 9, 243–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/9.4_Part_1.243 .

Bytheway, B. (1995). Ageism: Rethinking ageing series . Buckinghan: Open University Press.

Cameron, C. D., Brown-Iannuzzi, J. L., & Payne, B. K. (2012). Sequential priming measures of implicit social cognition: A meta-analysis of associations with behavior and explicit attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16, 330–350. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868312440047 .

Casper, C., Rothermund, K., & Wentura, D. (2011). The activation of specific facets of age stereotypes depends on individuating information. Social Cognition, 29, 393–414. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2011.29.4.393 .

Dasgupta, N., & Greenwald, A. G. (2001). On the malleability of automatic attitudes: Combating automatic prejudice with images of admired and disliked individuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 800–814. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.800 .

Davey, J. (2014). Age discrimination in the workplace. Policy Quarterly, 10 (3), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.26686/pq.v10i3.4502 .

de Paula Couto, M. C. P., & Wentura, D. (2012). Automatically activated facets of ageism: Masked evaluative priming allows for a differentiation of age-related prejudice. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42, 852–863. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.1912 .

de Paula Couto, M. C. P., & Wentura, D. (2017). Implicit ageism. In T. D. Nelson (Eds.), Ageism, stereotyping and prejudice against older persons (2nd ed., pp. 37–76). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Derous, E., & Decoster, J. (2017). Implicit age cues in resumes: Subtle effects on hiring discrimination. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1321. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01321 .

Diekman, A., & Hirnisey, L. (2007). The effect of context on the silver ceiling: A role congruity perspective on prejudiced responses. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 1353–1366.

Duncan, C., & Loretto, W. (2004). Never the right age? Gender and age-based discrimination in employment. Gender Work and Organization, 11, 95–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2004.00222.x .

Eagly, A. H., & Diekman, A. B. (2005). What is the problem? Prejudice as an attitude-in-context. In J. F. Dovidio, P. Glick, & L. Rudman (Eds.), On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport (pp. 19–35). Malden: Blackwell.

European Commission. (2011). Synthesis report I—2011. Older workers, discrimination, and employment. http://ec.europa.eu/justice/discrimination/files/sen_synthesisreport2011_en.pdf . Accessed 29 Sept. 2018.

Fazio, R. H., & Olson, M. A. (2003). Implicit measures in social cognition research: Their meaning and use. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 297–327. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145225 .

Fazio, R. H., Sanbonmatsu, D. M., Powell, M. C., & Kardes, F. R. (1986). On the automatic activation of attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 229–238.

Federal Statistical Office. (2016). Older people in Germany and the EU . Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt, Federal Statistical Office.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 878–902. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.82.6.878 .

Garstka, T. A., Schmitt, M. T., Branscombe, N. R., & Hummert, M. L. (2004). How young and older adults differ in their responses to perceived age discrimination. Psychology and Aging, 19, 326–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.326 .

Gioaba, I., & Krings, F. (2017). Impression management in the job interview: An effective way of mitigating discrimination against older applicants? Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 770. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00770 .

Gordon, R. A., & Arvey, R. (2004). Age bias in laboratory and field settings: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34, 468–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02557.x .

Gow, A. J., Corley, J., Starr, J. M., & Deary, I. J. (2013). Which social network or support factors are associated with cognitive abilities in old age? Gerontology, 59, 454–463. https://doi.org/10.1159/000351265 .

Greenberg, J., Schimel, J., & Martens, A. (2002). Ageism: Denying the face of the future. In T. D. Nelson (Eds.), Ageism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older persons (pp. 27–48). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102 (1), 4–27.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. K. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1464–1480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464 .

Greenwald, A. G., Poehlman, T. A., Uhlmann, E. L., & Banaji, M. R. (2009). Understanding and using implicit association test: III: Meta-analysis of predictive validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 17–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015575 .

Harris, K., Krygsman, S., Waschenko, J., & Rudman, D. B. (2018). Ageism and the older worker: A scoping review. The Gerontologist, 58, e1–e14. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw194 .

Hassell, B., & Perrewé, P. (1993). An examination of the relationship between older workers’ perceptions of age discrimination and employee psychological states. Journal of Managerial Issues, 5 (1), 109–120. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40604173 .

Hess, T. M., Auman, C., Colcombe, S. J., & Rahhal, T. A. (2003). The impact of stereotype threat on age differences in memory performance. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 58, P3–P11. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.1.P3 .

Hofmann, W., Gawronski, B., Gschwendner, T., Le, H., & Schmitt, M. (2005). A meta-analysis on the correlation between the implicit association test and explicit self- report measures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1369–1385.

Horton, S., Baker, J., Pearce, G. W., & Deakin, J. M. (2008). On the malleability of performance: Implications for seniors. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 27 (4), 446–65.

Hummert, M. L., Garstka, T. A., O’Brien, L. T., Greenwald, A. G., & Mellott, D. S. (2002). Using the implicit association test to measure age differences in implicit social cognitions. Psychology and Aging, 17, 482–495. https://doi.org/10.1037//0882-7974.17.3.482 .

James, J. B., McKechnie, S., Swanberg, J., & Besen, E. (2013). Exploring the workplace impact of intentional/unintentional age discrimination. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 28, 907–927. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-06-2013-0179 .

Kaufman, M. C., Krings, F., & Sczesny, S. (2016). Looking too old? How an older age appearance reduces chances of being hired. British Journal of Management, 27, 727–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12125 .

Kaufmann, M. C., Krings, F., Zebrowitz, L. A., & Sczesny, S. (2017). Age bias in selection decisions: The role of facial appearance and fitness impressions. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2065. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02065 .

Kite, M. E., & Johnson, B. T. (1988). Attitudes toward older and younger adults: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 3, 233–244.

Kite, M. E., Stockdale, G. D., Whitley, B. E., Jr., & Johnson, B. T. (2005). Attitudes toward younger and older adults: An updated meta-analytic review. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 241–266.

Kornadt, A. E., & Rothermund, K. (2012). Internalization of age stereotypes into the self-concept via future self-views: A general model and domain-specific differences. Psychology and Aging, 27, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025110 .

Kornadt, A. E., Meissner, F., & Rothermund, K. (2016). Implicit and explicit age stereotypes for specific life-domains across the life span: Distinct patterns and age group differences. Experimental Aging Research, 42, 195–211.

Kroon, A. C. (2015). Age for change: Tackling ageism in the workplace. The European Health Psychologist, 17 (4), 179–184.

Levy, B. (2009). Stereotype embodiment: A psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18 (6), 332–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x .

Lin, X., Bryant, C., & Boldero, J. (2010). Measures for assessing student attitudes toward older people. Educational Gerontology, 37, 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270903534796 .

Malinen, S., & Johnston, L. (2013). Workplace ageism: Discovering hidden bias. Experimental Aging Research, 39, 445–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361073X.2013.808111 .

McCann, R., & Giles, H. (2002). Ageism in the workplace: A communication perspective. In T. Nelson (Eds.), Ageism—Stereotyping and prejudice against older persons (pp. 163–199). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Meissner, F., & Rothermund, K. (2013). Estimating the contributions of associations and recoding in the Implicit Association Test and ReAL model for the IAT. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104 (1), 45–69.

Miller, C. T., & Kaiser, C. R. (2001). A theoretical perspective on coping stigma. Journal of Social Issues, 57 (1), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00202 .

Montepare, J. M., & Zebrowitz, L. A. (2002). A social-developmental view of ageism. In T. Nelson (Eds.), Ageism—Stereotyping and prejudice against older persons (pp. 77–125). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Moors, A., Spruyt, A., & De Houwer, J. (2010). In search of a measure that qualifies as implicit: Recommendations based on a decompositional view of automaticity. In B. Gawronski & K. B. Payne (Eds.), Handbook of implicit social cognition: Measurement, theory, and applications (pp. 19–37). New York: Guilford Press.

Nicholson, N. R. (2012). A review of social isolation: An important but underassessed condition in older adults. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 33, 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-012-0271-2 .

North, M. S., & Fiske, S. T. (2012). An inconvenienced youth? Ageism and its potential intergenerational roots. Psychological Bulletin, 138 (5), 982–997. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027843 .

North, M. S., & Fiske, S. T. (2013). A prescriptive intergenerational-tension ageism scale: Succession, identity, and consumption (SIC). Psychological Assessment, 25 (3), 706–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032367 .

Nosek, B. A., Banaji, M. R., & Greenwald, A. G. (2002). Harvesting implicit group attitudes and beliefs from a demonstration web site. Group Dynamics, 6, 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1037//1089-2699.6.1.101 .

Nosek, B. A., Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (2005). Understanding and using the implicit association test: II. Method variables and construct validity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2, 166–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271418 .

Nussbaum, J. F., Pitts, M. J., Huber, F. N., Krieger, J. R. L., & Ohs, J. E. (2005). Ageism and ageist language across the life span: Intimate relationships and non-intimate interactions. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 287–305.

OECD. (1998). Work force ageing: Consequences and policy responses . Ageing Working Paper, AWP4.1. Paris.

OECD. (2006). Live longer, work longer . Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264035881-en .

Book Google Scholar

Palmore, E. (1999). Ageism: Positive and negative (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Palmore, E. (2001). The ageism survey: First findings. The Gerontologist, 41, 572–575. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/41.5.572 .

Palmore, E. (2003). Ageism comes of age. The Gerontologist, 43, 418–420. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/43.3.418 .

Palmore, E. (2004). Research note: Ageism in Canada and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 19, 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JCCG.0000015098.62691.ab .

Pasupathi, M., & Löckenhoff, C. E. (2002). Ageist behavior. In T. D. Nelson (Eds.), Ageism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older persons (pp. 201–246). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Payne, B. K., Cheng, C. M., Govorun, O., & Stewart, B. D. (2005). An inkblot for attitudes: Affect misattribution as implicit measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.277 .

Posthuma, R. A., & Campion, M. A. (2009). Age stereotypes in the workplace: Common stereotypes, moderators, and future research directions. Journal of Management, 35, 158–188.

Posthuma, R. A., Wagstaff, M. F., & Campion, M. A. (2012). Age stereotypes and workplace age discrimination: A framework for future research. In W. C. Borman & J. W. Hedge (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Work and Aging (pp. 298–312). New York: Oxford University Press.

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J. R., & Snyder, S. S. (1982). Changing the world and changing the self: A two-process model of perceived control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 5–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.5 .

Rothermund, K., & Brandstädter, J. (2003). Age stereotypes and self-views in later life: Evaluating rival assumptions. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 549–554. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250344000208 .

Rothermund, K., Teige-Mocigemba, S., Gast, A., & Wentura, D. (2009). Eliminating the influence of recoding in the implicit association test: The recoding-free implicit association test (IAT-RF). Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 62 (1), 84–98.

Rothermund, K., & Wentura, D. (2007). Altersnormen und Altersstereotype. In J. Brandtstädter & U. Lindenberger (Eds.), Entwicklung über die Lebensspanne—Ein Lehrbuch (pp. 540–68). Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Rupp, D. E., Vodanovich, S. J., & Credé, M. (2006). Age bias in the workplace: The impact of ageism and causal attributions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 1337–1364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00062.x .

Schaie, K. W. (1993). Ageist language in psychological research. American Psychologist, 48, 49–51.

Schermuly, C. C., Deller, J., & Büsch, V. (2014). A research note on age discrimination and the desire to retire: The mediating effect of psychological empowerment. Research on Aging, 36, 382–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027513508288 .

Steele, C. M., Spencer, S. J., & Aronson, J. (2002). Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 34, pp. 379–440). San Diego: Academic. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(02)80009-0 .

Stypińska, J., & Nikander, P. (2018). Ageism and age discrimination in the labour market: A macrostructural perspective. In L. Ayalon & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism (pp. 91–108). Switzerland: Springer Open. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8 .

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Truxillo, D. M., Cadiz, D. M., & Hammer, L. B. (2015). Supporting the aging workforce: A review and recommendations for workplace intervention research. The Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2, 351–381. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111435 .

Vogt Yuan, A. S. (2007). Perceived age discrimination and mental health. Social Forces, 86 (1), 291–311. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2007.0113 .

Voss, P., Bodner, E., & Rothermund, K. (2018). Ageism: The relationship between age stereotypes and age discrimination. In L. Ayalon & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism (pp. 11–31). Berlin: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Voss, P., & Rothermund, K. (2018). Altersdiskriminierung in institutionellen Kontexten. In B. Kracke & P. Noack (Eds.), Handbuch Entwicklungs- und Erziehungspsychologie (pp. 509–538). Heidelberg: Springer.

Wentura, D., & Brandtstädter, J. (2003). Age stereotypes in younger and older women: Analyses of accommodative shifts with a sentence-priming task. Experimental Psychology, 50, 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1027//1618-3169.50.1.1 .

Wilkinson, J. A., & Ferraro, K. F. (2002). Thirty years of ageism research. In T. D. Nelson (Eds.), Ageism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older persons (pp. 339–358). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Wilson, T. D., Lindsey, S., & Schooler, T. Y. (2000). A model of dual attitudes. Psychological Review, 107 (1), 101–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.107.1.101 .

Zebrowitz, L. A., Franklin, R. G., Jr., Boshyan, J., Luevano, V., Agrigoroaei, S., Milosavljevic, B., & Lachman, M. E. (2014). Older and younger adults’ accuracy in discerning health and competence in older and younger faces. Psychology and Aging, 29, 454–468. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036255 .

Rothermund, K., & Mayer, A.-K. (2009). Altersdiskriminierung – Erscheinungsformen, Erklärungen und Interventionsansätze . Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

Bal, P. M., de Lange, A. H., Van der Heijden, B. I. J. M., Zacher, H., Oderkerk, F. A., & Otten, S. (2015). Young at heart, old at work? Relations between age, (meta-)stereotypes, self-categorization, and retirement attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.09.002 .

Cheung, C., Kam, P. K., & Man-hung Ngan, R. (2011). Age discrimination in the labour market from the perspectives of employers and older workers. International Social Work, 54, 118–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872810372368 .

Degner, J., & Wentura, D. (2011). Types of automatically activated prejudice: Assessing possessor- versus other-relevant valence in the evaluative priming task. Social Cognition, 29, 182–209. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2011.29.2.182 .

Gawronski, B., Cunningham, W. A., LeBel, E. P., & Deutsch, R. (2010). Attentional influences on affective priming: Does theory influence spontaneous evaluations of multiply categorisable objects? Cognition and Emotion, 24, 1008–1025. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930903112712-ks .

Golub, S. A., Filipowicz, A., & Langer, E. J. (2002). Acting your age. In T. D. Nelson (Eds.), Ageism: Stereotyping and prejudice against older persons (pp. 277–294). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kistler, E., & Mendius, H. G. (2002). Demographic change in the world of work—Opportunities for an innovative approach to work—A German point of view . Stuttgart: Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung.

Kluge, A., & Krings, F. (2008). Attitudes toward older workers and human resource practices. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 67, 61–64. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185.67.1.61 .

Maurer, T. J., Barbeite, F. G., Weiss, E. M., & Lippstreu, M. (2008). New measures of stereotypical beliefs about older workers’ ability and desire for development: Exploration among employees age 40 and over. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23, 395–418. https://doi.org/10.1108/026839408108069024 .

Naegele, L., De Tavernier, W., & Moritz, H. (2018). Work environment and the origin of ageism. In L. Ayalon & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism (pp. 73–90). Switzerland: Springer Open. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8 .

Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2012). Evaluating six common stereotypes about older workers with meta-analytical data. Personnel Psychology, 65, 821–858. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12003 .

Perdue, C. W., & Gurtman, M. B. (1990). Evidence for the automaticity of ageism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 26, 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(90)90035-K .

Rabl, T. (2010). Age, discrimination and achievement motives: A study of German employees. Personnel Review, 39, 448–467. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483481011045416 .