How to write a Research Paper – Step by Step Guide

A Step-by-Step Guide to writing a research paper

Introduction:

Writing a research paper is a job that we all have to do in our academic life. A research paper represents the ideas of the person who writes it. In simple words, a research paper presents an original idea and substantiates it with logical arguments. Writing a research paper in the domain of English literature is very different compared to writing research articles in other domains. Literature inclines towards abstract thinking. In other subjects, one has to stick to the facts. Howsoever you try, disputing an idea of science becomes very difficult. On the other hand, to contradict an idea in the purview of literature, you just need a systematic flow of arguments (logical and valid) and it’s done! So, writing a research paper in the field of English literature becomes easy if arguments are strong, in a sequence and wisely crafted.

Step 1: Choose the topic of your research paper:

This is one of the most vital parts. Choosing a topic is a crucial choice to make and it has to be taken seriously. You have to choose the area of your interest in English literature and then narrow it down to the area of your expertise. You cannot write a paper on the topics which are wider than a Doctoral thesis! So, you have to be precise and wise while choosing your topic.

An example: Suppose a person has adequate knowledge about Matthew Arnold. Can he write a research article on Arnold alone? No! He will need to bring the topic to some specific idea related to Arnold. The possibilities may be in his prose or poetry writing. In certain states in India, students work on topics like “Matthew Arnold as a poet” and “Matthew Arnold as a great prose writer” which is invalid, injustice and academically a sin. It should not be encouraged! Someone being a poet cannot be a subject of a research article. Any special quality of someone’s poetry writing can certainly be an interesting topic of a research paper – now you must have the idea. ‘Hopelessness and Despair in the poetry of Matthew Arnold’ can be a topic for a brilliant research paper. The hint is very simple – narrow it down to the speciality and you will have your topic ready!

Read in detail – How to choose a research topic?

Step 2: Collect information – primary and secondary sources:

Now that you have selected a topic for your research paper, you should find ‘credible sources’ that substantiate your ‘paper’s purpose’. Sources are divided into two major categories – primary and secondary. Primary sources are the materials produced by the people who feature in your topic. In the case of our example above, poetry by Matthew Arnold and other writings by him will be primary sources. Secondary sources are the writings ‘about the topic and anything related to the topic’. Therefore, you have to browse the internet, visit a library, check your bookshelves and do anything that will bring you information about the topic and anything that relates to the topic.

Step 3: Plan your research article:

Before you begin writing the paper, it’s always wise to have a clear plan in your mind. Planning a research paper in the domain of English literature should always begin with a clear ‘purpose of research’ in your mind. Why are you writing this paper? What point do you want to make? How significant is that point? Do you have your arguments to support the point (or idea) that you want to establish? Do you have enough credible sources that support the arguments you want to make in the body of the paper? If all the answers are positive, move to the next step and begin writing the drafts for your paper.

Step 4: Writing the first draft of your research paper:

Now it comes to writing the paper’s first draft. Before you begin writing, have a clear picture of your paper in your mind. It will make the job easier. What does a research paper look like? Or, rather, what’s the ideal structure of a research paper?

Beginning – Introduce your idea that drives the research paper. How do you approach that idea? What is your paper – an analysis, review of a book or two ideas compared or something else. The introduction must tell the story of your research in brief – ideas, a highlight or arguments and the glimpse of conclusion. It is generally advised that the introduction part should be written in the end so that you have the final research paper clearly justified, introduced and highlighted at the beginning itself.

Middle – And here goes the meat of your paper. All that you have to emphasise, euphemise, compare, collaborate and break down will take place in the middle or the body of your research paper. Please be careful once you begin writing the body of your paper. This is what will impact your readers (or the examiners or the teachers) the most. You have to be disciplined, systematic, clever and also no-nonsense. Make your points and support them with your arguments. Arguments should be logical and based on textual proofs (if required). Analyse, compare or collaborate as required to make your arguments sharp and supportive to the proposition that you make. The example topic of a research paper that we chose somewhere above in this article – Hopelessness and Despair in the Poetry of Matthew Arnold will require the person writing this paper to convince the readers (and so on) that actually Arnold’s poetry gives a sign of the two negative attitudes picked as the topic. It would be wise to analyse the works (and instances from them, to be specific) The Scholar Gypsy, Empedocles on Etna, Dover Beach and others that support the proposition made in the topic for research. You can use primary and secondary sources and cite them wisely as required. You have to convince the readers of your paper that what you propose in the purpose of the research paper stands on the ground as a logical and valid proposition.

End – Or the conclusion of a research paper that should be written wisely and carefully. You can use a few of your strongest arguments here to strike the final balance and make your proposition justified. After a few of your strongest arguments are made, you can briefly summarise your research topic and exhibit your skills of writing to close the lid by justifying why you are proposing that you have concluded what you began. Make sure that you leave the least possible loopholes for conjecture after you conclude your paper.

Reference: You can use two of the most used styles (or rather only used) to give a list of references in your paper – APA or MLA. Whatever you choose needs to be constant throughout the paper.

To summarise, here is what a research paper should look like:

- Introduction

- A list of References

Step 5: Read & re-read your draft: It gives you the chance to judge your research paper and find the possible shortcomings so that you can make amends and finalise your paper before you print it out for your academic requirements. While you read your first draft, treat it with a purpose to find contradictions and conjecture points as much as possible. Wherever you find the chances of contradiction possible, you have to make those arguments forceful and more logical and substantiate them to bypass the fear of being contradicted (and defeated). Let us be clear – it is English literature we are dealing with and there will be contradictions. Don’t fear it. However, make sure your arguments are not defeated. The defeat means your paper will not hold up to the scrutiny of the experts. And this is why you need to read and re-read the first draft of your literature research paper.

Step 6: Finalise & print your research paper: After reading your paper 1 or 2 times, you should be sure what needs to be changed and otherwise. Finalise it so that it appears the best and sounds good to be the final version. Print your work in the best possible quality and you are done! If there is a verbal question-answer associated with the paper you prepare, make sure you understand it completely and are ready for the questions from any possible side of your topic.

This was our step-by-step guide to writing a research paper in the field of English literature. We hope you have found it useful. We will write more articles associated with the concept – such as choosing a research topic, building arguments, writing powerful introductions. Make sure you subscribe to our website so that you are notified whenever we post a new article on English Literature Education! All the best with your paper!

More guides on How to Subjects:

How to Study Poetry?

Read related articles from this category:

Bildungsroman – literary term definition, examples, notes & help you need

List of important literary terms associated with studying drama or play – Literature Guides

What is Drama? What is Drama in Literature? Features, Types & Details Students Must Know

Have something to say? Add your comments:

9 Comments . Leave new

Thank you so much, explanation about research work is a nice manner. (private information retracted)

Very well written article! Thanks for this. I was confused about my research paper. I am sure I can do it now.

Quite resourceful. thank you.

Very nice reseach paper

It was very nice reading, helpful for writing research paper.

Thanks for your kind sharing of the information

Normally, I don’t leave any replies after reading a blog, but I couldn’t help this time. I found this blog very useful. So, I’m writing my research paper and I’ve been racking my brain and the internet for a good topic, plus trying to learn how to write a research paper. Thank you so much for putting this up!

I want to work on The French Revolution and its impact on romantic poetry. Please help in this regard.

Thanks a lot for the information.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post Comment

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Journal › Top Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature

Top Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on June 15, 2020 • ( 0 )

1. English Historical Review -(OXFORD) (https://academic.oup.com/ehr/pages/About)

2. ASIATIC: IITUM Journal of English Language & Literature ( https://journals.iium.edu.my/asiatic/index.php/AJELL )

3. English for Specific Purposes ( https://www.journals.elsevier.com/english-for-specific-purposes )

4. The Australian Association for the Teaching of English (AATE) ( https://www.aate.org.au/journals/english-in-australia )

5. English in Education (Wiley) ( https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/17548845 )

6. English World-Wide | A Journal of Varieties of English ( https://benjamins.com/catalog/eww )

7. European Journal of English Studies– Taylor & Francis Online ( https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/neje20/current )

8. Journal of English for Academic Purposes – Elsevier B.V. ( https://www.journals.elsevier.com/journal-of-english-for-academic-purposes )

9. Journal of English Linguistics- SAGE Journals ( https://journals.sagepub.com/home/eng )

10. Research in the Teaching of English-NCTE ( https://www2.ncte.org/resources/journals/research-in-the-teaching-of-english/ /)

11. The English Classroom – Regional Institute of English ( http://www.riesielt.org/english-classroom-journal )

12. World Englishes (Wiley Blackwell) ( https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/1467971x )

13. English Language & Linguistics – Cambridge Core ( https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/english-language-and-linguistics )

14. English Today-The International Review of the English Language-Cambridge Core ( https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/english-today )

Share this:

Categories: Journal

Tags: Best Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature , Free Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature , Gnuine Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature , Journals in English Literature , Literary Theory , Scopus Indexed Journals , Top Scopus Indexed Journals in English , Top Scopus Indexed Journals in English Literature , UGC Approved Journals , UGC Approved Journals in English

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and...

Limitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Future Research – Thesis Guide

Data Verification – Process, Types and Examples

APA Table of Contents – Format and Example

APA Research Paper Format – Example, Sample and...

- Hirsh Health Sciences

- Webster Veterinary

English Literature: Resources for Graduate Research

- Articles on Your Topic

- Books on Literary History, Theory, Criticism & More

- Novels, Poems & Other Primary Texts

What is a literature review?

How to conduct a literature review, books at tufts & beyond.

- Historic Newspapers & More

- Reviews, Essays & More

- English & the Digital Humanities

- How to Find Cited Material

- Citing Your Sources This link opens in a new window

- Getting Items that Tufts Doesn't Own

- Copyright & Publication This link opens in a new window

"A literature review is a body of text that aims to review the critical points of current knowledge on and/or methodological approaches to a particular topic. They are secondary sources and discuss published information in a particular subject area, and sometimes information in a particular subject area within a certain time period. Its ultimate goal is to bring the reader up to date with current literature on a topic and forms the basis for another goal, such as future research that may be needed in the area.

A literature review usually precedes a research proposal and may be just a simple summary of sources. Usually, however, it has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis.

A summary is a recap of important information about the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information. It might give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations. Or it might trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates. Depending on the situation, the literature review may evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant of them.

Keep in mind that the main focus of an academic research paper is to develop a new argument, and a research paper will contain a literature review as one of its parts. In a research paper, you use the literature as a foundation and as support for a new insight that you contribute. The focus of a literature review, however, is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of others without adding new contributions."

The following resource include a number of interesting tips on conducting literature reviews:

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It Valuable guidelines from the University of Toronto.

- Literature Reviews From UNC Chapel Hill, this site explains what literature reviews are and offer insights into the form and construction of literature reviews in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences.

- How to Write a Literature Review A comprehensive guide from UC Santa Cruz Libraries.

- Software Tools for a Literature Review A tutorial that explains how mind maps, pdf readers, and citation managers can be used for a literature review (see first part of the tutorial).

- Review of Literature A useful overview of literature reviews from UW-Madison.

This is a sample of books at Tufts and beyond that include helpful tips for conducting literature reviews and writing dissertations and theses.

- << Previous: Novels, Poems & Other Primary Texts

- Next: Historic Newspapers & More >>

- Last Updated: Aug 15, 2024 2:46 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.library.tufts.edu/EnglishGraduateResources

Department of English

Recent PhD Dissertations

Terekhov, Jessica (September 2022) -- "On Wit in Relation to Self-Division"

Selinger, Liora (September 2022) -- "Romanticism, Childhood, and the Poetics of Explanation"

Lockhart, Isabel (September 2022) -- "Storytelling and the Subsurface: Indigenous Fiction, Extraction, and the Energetic Present"

Ashe, Nathan (April 2022) – "Narrative Energy: Physics and the Scientific Real in Victorian Literature”

Bartley, Scott H. (April 2022) – “Watch it closely: The Poetry and Poetics of Aesthetic Focus in The New Criticism and Middle Generation”

Mctar, Ali (November 2021) – “Fallen Father: John Milton, Antinomianism, and the Case Against Adam”

Chow, Janet (September 2021) – “Securing the Crisis: Race and the Poetics of Risk”

Thorpe, Katherine (September 2021) – “Protean Figures: Personified Abstractions from Milton’s Allegory to Wordsworth’s Psychology of the Poet”

Minnen, Jennifer (September 2021) – “The Second Science: Feminist Natural Inquiry in Nineteenth-Century British Literature”

Starkowski, Kristen (September 2021) – “Doorstep Moments: Close Encounters with Minor Characters in the Victorian Novel”

Rickard, Matthew (September 2021) – “Probability: A Literary History, 1479-1700”

Crandell, Catie (September 2021) – “Inkblot Mirrors: On the Metareferential Mode and 19th Century British Literature”

Clayton, J.Thomas (September 2021) – “The Reformation of Indifference: Adiaphora, Toleration, and English Literature in the Seventeenth Century”

Goldberg, Reuven L. (May 2021) – “I Changed My Sex! Pedagogy and the Trans Narrative”

Soong, Jennifer (May 2021) – “Poetic Forgetting”

Edmonds, Brittney M. (April 2021) – “Who’s Laughing Now? Black Affective Play and Formalist Innovation in Twenty-First Century black Literary Satire”

Azariah-Kribbs, Colin (April 2021) – “Mere Curiosity: Knowledge, Desire, and Peril in the British and Irish Gothic Novel, 1796-1820”

Pope, Stephanie (January 2021) – “Rethinking Renaissance Symbolism: Material Culture, Visual Signs, and Failure in Early Modern Literature, 1587-1644”

Kumar, Matthew (September 2020) – “The Poetics of Space and Sensation in Scotland and Kenya”

Bain, Kimberly (September 2020) – “On Black Breath”

Eisenberg, Mollie (September 2020) – “The Case of the Self-Conscious Detective Novel: Modernism, Metafiction, and the Terms of Literary Value”

Hori, Julia M. (September 2020) – “Restoring Empire: British Imperial Nostalgia, Colonial Space, and Violence since WWII”

Reade, Orlando (June 2020) – “Being a Lover of the World: Lyric Poetry and Political Disaffection after the English Civil War”

Mahoney, Cate (June 2020) – “Go on Your Nerve: Confidence in American Poetry, 1860-1960”

Ritger, Matthew (April 2020) – “Objects of Correction: Literature and the Birth of Modern Punishment”

VanSant, Cameron (April 2020) – “Novel Subjects: Nineteenth-Century Fiction and the Transformation of British Subjecthood”

Lennington, David (November 2019) – “Anglo-Saxon and Arabic Identity in the Early Middle Ages”

Marraccini, Miranda (September 2019) – “Feminist Types: Reading the Victoria Press”

Harlow, Lucy (June 2019) – “The Discomposed Mind”

Williamson, Andrew (June 2019) – “Nothing to Say: Silence in Modernist American Poetry”

Adair, Carl (April 2019) – “Faithful Readings: Religion, Hermeneutics, and the Habits of Criticism”

Rogers, Hope (April 2019) – “Good Girls: Female Agency and Convention in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel”

Green, Elspeth (January 2019) – “Popular Science and Modernist Poetry”

Braun, Daniel (January 2019) – Kinds of Wrong: The Liberalization of Modern Poetry 1910-1960”

Rosen, Rebecca (November 2018) – “Making the body Speak: Anatomy, Autopsy and Testimony in Early America, 1639-1790”

Blank, Daniel (November 2018) – Shakespeare and the Spectacle of University Drama”

Case, Sarah (September 2018) – Increase of Issue: Poetry and Succession in Elizabethan England”

Kucik, Emanuela (June 2018) – “Black Genocides and the Visibility Paradox in Post-Holocaust African American and African Literature”

Quinn, Megan (June 2018) – “The Sensation of Language: Jane Austen, William Wordsworth, Mary Shelley”

McCarthy, Jesse D. (June 2018) – “The Blue Period: Black Writing in the Early Cold War, 1945-1965

Johnson, Colette E. (June 2018) – “The Foibles of Play: Three Case Studies on Play in the Interwar Years”

Gingrich, Brian P. (June 2018) – “The Pace of Modern Fiction: A History of Narrative Movement in Modernity”

Marcus, Sara R. (June 2018) – “Political Disappointment: A Partial History of a Feeling”

Parry, Rosalind A. (April 2018) – “Remaking Nineteenth-Century Novels for the Twentieth Century”

Gibbons, Zoe (January 2018) – “From Time to Time: Narratives of Temporality in Early Modern England, 1610-1670”

Padilla, Javier (September 2017) – “Modernist Poetry and the Poetics of Temporality: Between Modernity and Coloniality”

Alvarado, Carolina (June 2017) – "Pouring Eastward: Editing American Regionalism, 1890-1940"

Gunaratne, Anjuli (May 2017) – "Tragic Resistance: Decolonization and Disappearance in Postcolonial Literature"

Glover, Eric (May 2017) – "By and About: An Antiracist History of the Musicals and the Antimusicals of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston"

Tuckman, Melissa (April 2017) – "Unnatural Feelings in Nineteenth-Century Poetry"

Eggan, Taylor (April 2017) – "The Ecological Uncanny: Estranging Literary Landscapes in Twentieth-Century Narrative Fiction"

Calver, Harriet (March 2017) – "Modern Fiction and Its Phantoms"

Gaubinger, Rachel (December 2016) – "Between Siblings: Form and Family in the Modern Novel"

Swartz, Kelly (December 2016) – "Maxims and the Mind: Sententiousness from Seventeenth-Century Science to the Eighteenth-Century Novel"

Robles, Francisco (June 2016) – “Migrant Modalities: Radical Democracy and Intersectional Praxis in American Literatures, 1923-1976”

Johnson, Daniel (June 2016) – “Visible Plots, Invisible Realms”

Bennett, Joshua (June 2016) – “Being Property Once Myself: In Pursuit of the Animal in 20th Century African American Literature”

Scranton, Roy (January 2016) – “The Trauma Hero and the Lost War: World War II, American Literature, and the Politics of Trauma, 1945-1975

Jacob, Priyanka (November 2015) – “Things That Linger: Secrets, Containers and Hoards in the Victorian Novel”

Evans, William (November 2015) – “The Fiction of Law in Shakespeare and Spenser”

Vasiliauskas, Emily (November 2015) – “Dead Letters: The Afterlife Before Religion”

Walker, Daniel (June 2015) – “Sociable Uncertainties: Literature and the Ethics of Indeterminacy in Eighteenth-Century Britain”

Reilly, Ariana (June 2015) – “Leave-Takings: Anti-Self-Consciousness and the Escapist Ends of the Victorian Marriage Plot”

Lerner, Ross (June 2015) – "Framing Fanaticism: Religion, Violence, and the Reformation Literature of Self-Annihilation”

Harrison, Matthew (June 2015) – "Tear Him for His Bad Verses: Poetic Value and Literary History in Early Modern England”

Krumholtz, Matthew (June 2015) – “Talking Points: American Dialogue in the Twentieth Century”

Dauber, Maayan (March 2015) – "The Pathos of Modernism: Henry James, Virginia Woolf, and Gertrude Stein (with a coda on J.M. Coetzee)”

Hostetter, Lyra (March 2015) – “Novel Errantry: An Annotated Edition of Horatio, of Holstein (1800)”

Sanford, Beatrice (January 2015) – “Love’s Perception: Nineteenth-Century Aesthetics of Attachment”

Chong, Kenneth (January 2015) – “Potential Theologies: Scholasticism and Middle English Literature”

Worsley, Amelia (September 2014) – “The Poetry of Loneliness from Romance to Romanticism”

Hurtado, Jules (June 2014) – “The Pornographer at the Crossroads: Sex, Realism and Experiment in the Contemporary English Novel”

Rutherford, James (June 2014) – "Irrational Actors: Literature and Logic in Early Modern England”

Wilde, Lisa (June 2014) – “English Numeracy and the Writing of New Worlds, 1543-1622”

Hyde, Emily (November 2013) – “A Way of Seeing: Modernism, Illustration, and Postcolonial Literature”

Ortiz, Ivan (September 2013) – “Romanticism and the Aesthetics of Modern Transport”

Aronowicz, Yaron (September 2013) – “Fascinated Moderns: The Attentions of Modern Fiction”

Wythoff, Grant (September 2013) – “Gadgetry: New Media and the Fictional Imagination”

Ramachandran, Anitha (September 2013) – "Recovering Global Women’s Travel Writings from the Modern Period: An Inquiry Into Genre and Narrative Agency”

Reuland, John (April 2013) – “The Self Unenclosed: A New Literary History of Pragmatism, 1890-1940”

Wasserman, Sarah (January 2013) – “Material Losses: Urban Ephemera in Contemporary American Literature and Culture”

Kastner, Tal (November 2012) – "The Boilerplate of Everything and the Ideal of Agreement in American Law and Literature"

Labella, John (October 2012) – "Lyric Hemisphere: Latin America in United States Poetry, 1927-1981"

Kindley, Evan (September 2012) – "Critics and Connoisseurs: Poet-Critics and the Administration of Modernism"

Smith, Ellen (September 2012) – "Writing Native: The Aboriginal in Australian Cultural Nationalism 1927-1945"

Werlin, Julianne (September 2012) – "The Impossible Probable: Modeling Utopia in Early Modern England"

Posmentier, Sonya (May 2012) – "Cultivation and Catastrophe: Forms of Nature in Twentieth-Century Poetry of the Black Diaspora"

Alfano, Veronica (September 2011) – “The Lyric in Victorian Memory”

Foltz, Jonathan (September 2011) – “Modernism and the Narrative Cultures of Film”

Coghlan, J. Michelle (September 2011) – “Revolution’s Afterlife; The Paris Commune in American Cultural Memory, 1871-1933”

Christoff, Alicia (September 2011) – “Novel Feeling”

Shin, Jacqueline (August 2011) – “Picturing Repose: Between the Acts of British Modernism”

Ebrahim, Parween (August 2011) – “Outcasts and Inheritors: The Ishmael Ethos in American Culture, 1776-1917”

Reckson, Lindsay (August 2011) – “Realist Ecstasy: Enthusiasm in American Literature 1886 - 1938"

Londe, Gregory (June 2011) – “Enduring Modernism: Forms of Surviving Location in the 20th Century Long Poem”

Brown, Adrienne (June 2011) – “Reading Between the Skylines: The Skyscraper in American Modernism”

Russell, David (June 2011) – “A Literary History of Tact: Sociability, Aesthetic Liberalism and the Essay Form in Nineteenth-Century Britain”

Hostetter, Aaron (December 2010) – "The Politics of Eating and Cooking in Medieval English Romance"

Moshenska, Joseph (November 2010) – " 'Feeling Pleasures': The Sense of Touch in Renaissance England"

Walker, Casey (September 2010) – "The City Inside: Intimacy and Urbanity in Henry James, Marcel Proust and Virginia Woolf"

Rackin, Ethel (August 2010) – "Ornamentation and Essence in Modernist Poetry"

Noble, Mary (August 2010) – "Primitive Marriage: Anthropology and Nineteenth-Century Fiction"

Fox, Renee (August 2010) – "Necromantic Victorians: Reanimation, History and the Politics of Literary Innovation, 1868-1903"

Hopper, Briallen (June 2010) – “Feeling Right in American Reform Culture”

Lee, Wendy (June 2010) -- "Failures of Feeling in the British Novel from Richardson to Eliot"

Moyer, James (March 2010) – "The Passion of Abolitionism: How Slave Martyrdom Obscures Slave Labor”

Forbes, Erin (September 2009) – “Genius of Deep Crime: Literature, Enslavement and the American Criminal”

Crawforth, Hannah (September 2009) – “The Politics and Poetics of Etymology in Early Modern Literature”

Elliott, Danielle (April 2009) – "Sea of Bones: The Middle Passage in Contemporary Poetry of the Black Atlantic”

Yu, Wesley (April 2009) – “Romance Logic: The Argument of Vernacular Verse in the Scholastic Middle Ages”

Cervantes, Gabriel (April 2009) – "Genres of Correction: Anglophone Literature and the Colonial Turn in Penal Law 1722-1804”

Rosinberg, Erwin (January 2009) – "A Further Conjunction: The Couple and Its Worlds in Modern British Fiction”

Walsh, Keri (January 2009) – "Antigone in Modernism: Classicism, Feminism, and Theatres of Protest”

Heald, Abigail (January 2009) – “Tears for Dido: A Renaissance Poetics of Feeling”

Bellin, Roger (January 2009) – "Argument: The American Transcendentalists and Disputatious Reason”

Ellis, Nadia (November 2008) – "Colonial Affections: Formulations of Intimacy Between England and the Caribbean, 1930-1963”

Baskin, Jason (November 2008) – “Embodying Experience: Romanticism and Social Life in the Twentieth Century”

Barrett, Jennifer-Kate (September 2008) – “ ‘So Written to Aftertimes’: Renaissance England’s Poetics of Futurity”

Moss, Daniel (September 2008) – “Renaissance Ovids: The Metamorphosis of Allusion in Late Elizabethan England”

Rainof, Rebecca (September 2008) – “Purgatory and Fictions of Maturity: From Newman to Woolf”

Darznik, Jasmin (November 2007) – “Writing Outside the Veil: Literature by Women of the Iranian Diaspora”

Bugg, John (September 2007) – “Gagging Acts: The Trials of British Romanticism”

Matson, John (September 2007) – “Marking Twain: Mechanized Composition and Medial Subjectivity in the Twain Era”

Neel, Alexandra (September 2007) – “The Writing of Ice: The Literature and Photography of Polar Regions”

Smith-Browne, Stephanie (September 2007) – “Gothic and the Pacific Voyage: Patriotism, Romance and Savagery in South Seas Travels and the Utopia of the Terra Australis”

Bystrom, Kerry (June 2007) – “Orphans and Origins: Family, Memory, and Nation in Argentina and South Africa”

Ards, Angela (June 2007) – “Affirmative Acts: Political Piety in African American Women’s Contemporary Autobiography”

Cragwall, Jasper (June 2007) – “Lake Methodism”

Ball, David (June 2007) – “False Starts: The Rhetoric of Failure and the Making of American Modernism, 1850-1950”

Ramdass, Harold (June 2007) – “Miswriting Tragedy: Genealogy, History and Orthography in the Canterbury Tales, Fragment I”

Lilley, James (June 2007) – “Common Things: Transatlantic Romance and the Aesthetics of Belonging, 1764-1840”

Noble, Mary (March 2007) – “Primitive Marriage: Anthropology and Nineteenth-Century Fiction”

Passannante, Gerard (January 2007) – “The Lucretian Renaissance: Ancient Poetry and Humanism in an Age of Science”

Tessone, Natasha (November 2006) – “The Fiction of Inheritance: Familial, Cultural, and National Legacies in the Irish and Scottish Novel”

Horrocks, Ingrid (September 2006) – “Reluctant Wanderers, Mobile Feelings: Moving Figures in Eighteenth-Century Literature”

Bender, Abby (June 2006) – “Out of Egypt and into bondage: Exodus in the Irish National Imagination”

Johnson, Hannah (June 2006) – “The Medieval Limit: Historiography, Ethics, Culture”

Horowitz, Evan (January 2006) – “The Writing of Modern Life”

White, Gillian (November 2005) – “ ‘We Do Not Say Ourselves Like That in Poems’: The Poetics of Contingency in Wallace Stevens and Elizabeth Bishop

Baudot, Laura (September 2005) – “Looking at Nothing: Literary Vacuity in the Long Eighteenth Century”

Hicks, Kevin (September 2005) – “Acts of Recovery: American Antebellum Fictions”

Stern, Kimberly (September 2005) – “The Victorian Sibyl: Women Reviewers and the Reinvention of Critical Tradition”

Nardi, Steven (May 2005) – “Automatic Aesthetics: Race, Technology, and Poetics in the Harlem Renaissance and American New Poetry”

Sayeau, Michael (May 2005) – “Everyday: Literature, Modernity, and Time”

Cooper, Lawrence (April 2005) – “Gothic Realities: The Emergence of Cultural Forms Through Representations of the Unreal”

Betjemann, Peter (November 2004) – “Talking Shop: Craft and Design in Hawthorne, James, and Wharton”

Forbes, Aileen (November 2004) – “Passion Play: Theaters of Romantic Emotion”

Keeley, Howard (November 2004) – “Beyond Big House and Cabin: Dwelling Politically in Modern Irish Literature”

Machlan, Elizabeth (November 2004) – “Panic Rooms: Architecture and Anxiety in New York Stories from 1900 to 9/11”

McDowell, Demetrius (November 2004) – “Hawthorne, James, and the Pressures of the Literary Marketplace”

Waldron, Jennifer (November 2004) – “Eloquence of the Body: Aesthetics, Theology, and English Renaissance Theater”

- Dalhousie University Libraries

English Literature

- Research step-by-step

- Dictionaries, encyclopedias, and more

- Find articles

- Primary sources

- Recommended websites

- Book reviews

- MLA citation

- Citation management

On this page...

Step 1: choose a topic, step 2: consult reference sources, step 3: grab some books, step 4: search for articles, step 5: collect, read, evaluate, and write what you have learned, step 6: cite your sources.

- Document delivery

- Exercises & training

- Arthurian Literature series

- ENGL 2232: Contemporary Science Fiction

- ENGL 3301: Graphic Novels This link opens in a new window

- CRWR 4010: Advanced Creative Writing - Poetry I

This page walks you through the basic steps of research. Keep in mind that the research process is actually quite messy, and you might find yourself jumping back and forth between the steps listed here. These steps are meant to orient you to the research process, but you do not necessarily have to follow this exact order:

- Choose a topic

- Consult reference sources

- Grab some books

- Search for articles

- Collect, read, evaluate, and write what you have learned

- Cite your sources

When choosing a topic, keep the following points in mind:

- Choose a topic that ACTUALLY interests you.

- Your topic is not set in stone. Once you start doing some initial research on your topic, you will probably decide to tweak it a bit.

- Pick a topic that is manageable. If your topic is too broad, it will be hard to condense it all into one university paper. But if your topic is too narrow, you may have a hard time finding enough scholarly research for your paper.

- Handout: Choosing a topic Check out this helpful handout on choosing a research topic!

Or, watch this incredibly useful video from North Carolina State University Library on choosing a topic:

When you first get started on a research project, you might not have very much prior knowledge of your topic. In that case, it's a great idea to start with some background information. The most heavily-used reference source in the world is Wikipedia, but as a student you also have access to many other excellent scholarly reference sources.

Jump to the "Dictionaries, encyclopedias, and more" page of this guide.

Time to get down to it! Books will help you get an even better handle on your topic. Books provide more in-depth information than reference sources, but are often much better for background information than journal articles. Keep the following in mind:

- Start by registering your Dal card as your library card. Fill out your registration form and bring it to the service desk at the Killam Library, or register online using our online form (this will take about 24 hours to process).

- Use the Novanet library catalogue to search for books on your topic.

- You can access ebooks immediately online; if you find a print book that interests you, write down the call number and visit the stacks!

- Check out this quick video: How to read a call number in 90 seconds

- Remember that in most cases you won't need to read the whole book!

- You may borrow print books for 3 weeks, and renew them twice. To renew books online, start here . Click "Guest," at the top right of the screen, and then "My library card." Log in with your barcode and password. You should see an overview of the books you have checked out, and an option to renew. You can also check out this quick video tutorial on renewing books .

Jump to the "Find books" page of this guide.

Scholarly journals are specialized journals that publish new research on specialized topics. They are written FOR academics, researchers, and students to keep them aware of new developments in the field. They are written, for the most part, BY academics and researchers who are actively involved with the field of study. You can find scholarly articles in databases that the library subscribes to. Make sure to search in subject-specific databases (such as a history database), as well as multidisciplinary databases that include a wider scope of material.

Jump to the "Find journal articles" page of this guide.

- Handout: Identifying and reading scholarly works New to reading scholarly articles? Check out this helpful handout.

Or, check out this great video from Western Libraries:

Take very careful notes as you read your sources! This will help you trace themes and develop an argument. Check out the following two videos on writing a research paper, and make an appointment at the Dalhousie Writing Centre if you would like assistance with your writing.

- Dalhousie Writing Centre: Make an appointment

- Video tutorial: Writing a research paper, Part 1

- Writing Research Papers Part 2 Draft -- Revise -- Proof read -- References

Very important! When you use somebody else's words or ideas in your academic papers, you must to give credit to the original source. This is one of the reasons why keeping good notes is so important to the research process.

Jump to the MLA Citation page of this guide.

- << Previous: Citation management

- Next: Document delivery >>

- Last Updated: Sep 18, 2024 11:55 AM

- URL: https://dal.ca.libguides.com/English

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Literature Topics and Research

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

What kinds of topics are good ones?

The best topics are ones that originate out of your own reading of a work of literature, but here are some common approaches to consider:

- A discussion of a work's characters: are they realistic, symbolic, historically-based?

- A comparison/contrast of the choices different authors or characters make in a work

- A reading of a work based on an outside philosophical perspective (Ex. how would a Freudian read Hamlet ?)

- A study of the sources or historical events that occasioned a particular work (Ex. comparing G.B. Shaw's Pygmalion with the original Greek myth of Pygmalion)

- An analysis of a specific image occurring in several works (Ex. the use of moon imagery in certain plays, poems, novels)

- A "deconstruction" of a particular work (Ex. unfolding an underlying racist worldview in Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness )

- A reading from a political perspective (Ex. how would a Marxist read William Blake's "London"?)

- A study of the social, political, or economic context in which a work was written — how does the context influence the work?

How do I start research?

Once you have decided on an interesting topic and work (or works), the best place to start is probably the Internet. Here you can usually find basic biographical data on authors, brief summaries of works, possibly some rudimentary analyses, and even bibliographies of sources related to your topic.

The Internet, however, rarely offers serious direct scholarship; you will have to use sources found in the library, sources like journal articles and scholarly books, to get information that you can use to build your own scholarship-your literary paper. Consult the library's on-line catalog and the MLA Periodical Index. Avoid citing dictionary or encyclopedic sources in your final paper.

How do I use the information I find?

The secondary sources you find are only to be used as an aid. Your thoughts should make up most of the essay. As you develop your thesis, you will bring in the ideas of the scholars to back up what you have already said.

For example, say you are arguing that Huck Finn is a Christ figure ; that's your basic thesis. You give evidence from the novel that allows this reading, and then, at the right place, you might say the following, a paraphrase:

According to Susan Thomas, Huck sacrifices himself because he wants to set Jim free (129).

If the scholar states an important idea in a memorable way, use a direct quote.

"Huck's altruism and feelings of compassion for Jim force him to surrender to the danger" (Thomas 129).

Either way, you will then link that idea to your thesis.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

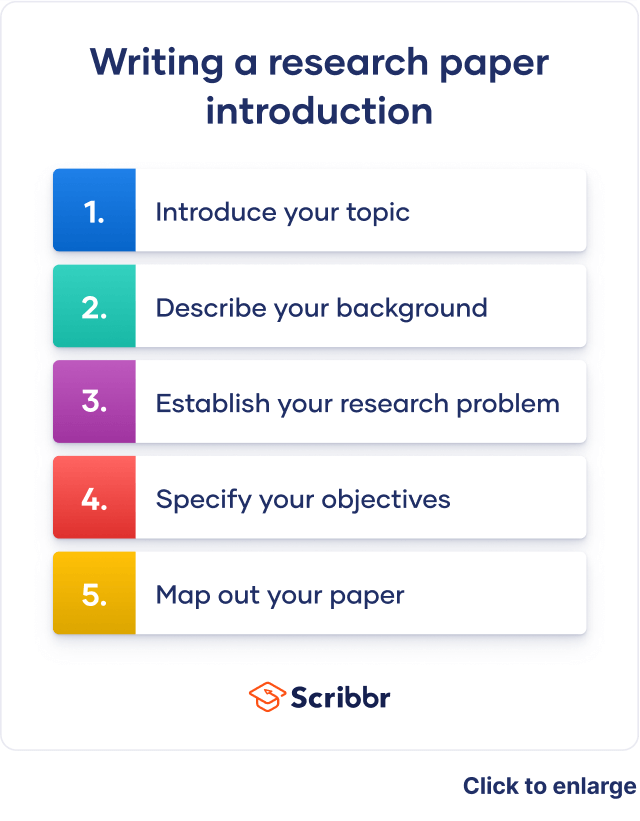

Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide

Published on September 24, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on September 5, 2024.

The introduction to a research paper is where you set up your topic and approach for the reader. It has several key goals:

- Present your topic and get the reader interested

- Provide background or summarize existing research

- Position your own approach

- Detail your specific research problem and problem statement

- Give an overview of the paper’s structure

The introduction looks slightly different depending on whether your paper presents the results of original empirical research or constructs an argument by engaging with a variety of sources.

The five steps in this article will help you put together an effective introduction for either type of research paper.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Step 1: introduce your topic, step 2: describe the background, step 3: establish your research problem, step 4: specify your objective(s), step 5: map out your paper, research paper introduction examples, frequently asked questions about the research paper introduction.

The first job of the introduction is to tell the reader what your topic is and why it’s interesting or important. This is generally accomplished with a strong opening hook.

The hook is a striking opening sentence that clearly conveys the relevance of your topic. Think of an interesting fact or statistic, a strong statement, a question, or a brief anecdote that will get the reader wondering about your topic.

For example, the following could be an effective hook for an argumentative paper about the environmental impact of cattle farming:

A more empirical paper investigating the relationship of Instagram use with body image issues in adolescent girls might use the following hook:

Don’t feel that your hook necessarily has to be deeply impressive or creative. Clarity and relevance are still more important than catchiness. The key thing is to guide the reader into your topic and situate your ideas.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

This part of the introduction differs depending on what approach your paper is taking.

In a more argumentative paper, you’ll explore some general background here. In a more empirical paper, this is the place to review previous research and establish how yours fits in.

Argumentative paper: Background information

After you’ve caught your reader’s attention, specify a bit more, providing context and narrowing down your topic.

Provide only the most relevant background information. The introduction isn’t the place to get too in-depth; if more background is essential to your paper, it can appear in the body .

Empirical paper: Describing previous research

For a paper describing original research, you’ll instead provide an overview of the most relevant research that has already been conducted. This is a sort of miniature literature review —a sketch of the current state of research into your topic, boiled down to a few sentences.

This should be informed by genuine engagement with the literature. Your search can be less extensive than in a full literature review, but a clear sense of the relevant research is crucial to inform your own work.

Begin by establishing the kinds of research that have been done, and end with limitations or gaps in the research that you intend to respond to.

The next step is to clarify how your own research fits in and what problem it addresses.

Argumentative paper: Emphasize importance

In an argumentative research paper, you can simply state the problem you intend to discuss, and what is original or important about your argument.

Empirical paper: Relate to the literature

In an empirical research paper, try to lead into the problem on the basis of your discussion of the literature. Think in terms of these questions:

- What research gap is your work intended to fill?

- What limitations in previous work does it address?

- What contribution to knowledge does it make?

You can make the connection between your problem and the existing research using phrases like the following.

| Although has been studied in detail, insufficient attention has been paid to . | You will address a previously overlooked aspect of your topic. |

| The implications of study deserve to be explored further. | You will build on something suggested by a previous study, exploring it in greater depth. |

| It is generally assumed that . However, this paper suggests that … | You will depart from the consensus on your topic, establishing a new position. |

Now you’ll get into the specifics of what you intend to find out or express in your research paper.

The way you frame your research objectives varies. An argumentative paper presents a thesis statement, while an empirical paper generally poses a research question (sometimes with a hypothesis as to the answer).

Argumentative paper: Thesis statement

The thesis statement expresses the position that the rest of the paper will present evidence and arguments for. It can be presented in one or two sentences, and should state your position clearly and directly, without providing specific arguments for it at this point.

Empirical paper: Research question and hypothesis

The research question is the question you want to answer in an empirical research paper.

Present your research question clearly and directly, with a minimum of discussion at this point. The rest of the paper will be taken up with discussing and investigating this question; here you just need to express it.

A research question can be framed either directly or indirectly.

- This study set out to answer the following question: What effects does daily use of Instagram have on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls?

- We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls.

If your research involved testing hypotheses , these should be stated along with your research question. They are usually presented in the past tense, since the hypothesis will already have been tested by the time you are writing up your paper.

For example, the following hypothesis might respond to the research question above:

The final part of the introduction is often dedicated to a brief overview of the rest of the paper.

In a paper structured using the standard scientific “introduction, methods, results, discussion” format, this isn’t always necessary. But if your paper is structured in a less predictable way, it’s important to describe the shape of it for the reader.

If included, the overview should be concise, direct, and written in the present tense.

- This paper will first discuss several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then will go on to …

- This paper first discusses several examples of survey-based research into adolescent social media use, then goes on to …

Scribbr’s paraphrasing tool can help you rephrase sentences to give a clear overview of your arguments.

Full examples of research paper introductions are shown in the tabs below: one for an argumentative paper, the other for an empirical paper.

- Argumentative paper

- Empirical paper

Are cows responsible for climate change? A recent study (RIVM, 2019) shows that cattle farmers account for two thirds of agricultural nitrogen emissions in the Netherlands. These emissions result from nitrogen in manure, which can degrade into ammonia and enter the atmosphere. The study’s calculations show that agriculture is the main source of nitrogen pollution, accounting for 46% of the country’s total emissions. By comparison, road traffic and households are responsible for 6.1% each, the industrial sector for 1%. While efforts are being made to mitigate these emissions, policymakers are reluctant to reckon with the scale of the problem. The approach presented here is a radical one, but commensurate with the issue. This paper argues that the Dutch government must stimulate and subsidize livestock farmers, especially cattle farmers, to transition to sustainable vegetable farming. It first establishes the inadequacy of current mitigation measures, then discusses the various advantages of the results proposed, and finally addresses potential objections to the plan on economic grounds.

The rise of social media has been accompanied by a sharp increase in the prevalence of body image issues among women and girls. This correlation has received significant academic attention: Various empirical studies have been conducted into Facebook usage among adolescent girls (Tiggermann & Slater, 2013; Meier & Gray, 2014). These studies have consistently found that the visual and interactive aspects of the platform have the greatest influence on body image issues. Despite this, highly visual social media (HVSM) such as Instagram have yet to be robustly researched. This paper sets out to address this research gap. We investigated the effects of daily Instagram use on the prevalence of body image issues among adolescent girls. It was hypothesized that daily Instagram use would be associated with an increase in body image concerns and a decrease in self-esteem ratings.

The introduction of a research paper includes several key elements:

- A hook to catch the reader’s interest

- Relevant background on the topic

- Details of your research problem

and your problem statement

- A thesis statement or research question

- Sometimes an overview of the paper

Don’t feel that you have to write the introduction first. The introduction is often one of the last parts of the research paper you’ll write, along with the conclusion.

This is because it can be easier to introduce your paper once you’ve already written the body ; you may not have the clearest idea of your arguments until you’ve written them, and things can change during the writing process .

The way you present your research problem in your introduction varies depending on the nature of your research paper . A research paper that presents a sustained argument will usually encapsulate this argument in a thesis statement .

A research paper designed to present the results of empirical research tends to present a research question that it seeks to answer. It may also include a hypothesis —a prediction that will be confirmed or disproved by your research.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2024, September 05). Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide. Scribbr. Retrieved September 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-paper/research-paper-introduction/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, writing a research paper conclusion | step-by-step guide, research paper format | apa, mla, & chicago templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Literature Research Paper Topics

This page provides a comprehensive guide to literature research paper topics , offering an extensive list divided into twenty categories, each with ten unique topics. Students can navigate the immense landscape of literature, including classical, contemporary, and multicultural dimensions, literary theory, specific authors’ studies, genre analyses, and historical contexts. From understanding how to choose the right topic to crafting an insightful literature research paper, this guide serves as a one-stop resource. Furthermore, iResearchNet’s writing services are presented, providing students with the opportunity to order a custom literature research paper with a range of impressive features, including expert writers, in-depth research, top-quality work, and guaranteed satisfaction. By exploring this page, students can find invaluable assistance and inspiration to embark on their literature research journey.

200 Literature Research Paper Topics

Literature is an expansive field that encompasses a multitude of subcategories. Below, we offer 200 literature research paper topics, neatly divided into twenty categories. Each of these themes presents a rich array of options to inspire your next research paper.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

- The representation of heroism in Homer’s “Iliad”

- The concept of fate in ancient Greek tragedies

- Female characters in Sophocles’ plays

- The importance of dialogue in Plato’s philosophical works

- The depiction of Gods in “The Odyssey”

- Tragic love in Virgil’s “Aeneid”

- Prophecy and divination in ancient Greek literature

- Wisdom in the works of Socrates

- The portrayal of Athens in Aristophanes’ comedies

- Stoicism in Seneca’s letters and essays

- Christian symbolism in Dante’s “Divine Comedy”

- The depiction of women in “The Canterbury Tales”

- Heroism in “Beowulf”

- The significance of dreams in medieval literature

- Religious conflict in “The Song of Roland”

- The concept of courtly love in “Tristan and Isolde”

- The role of magic in Arthurian literature

- The representation of chivalry in “Sir Gawain and the Green Knight”

- Life and death in “The Book of the Dead”

- The theme of rebellion in “The Decameron”

- The influence of humanism in Shakespeare’s plays

- Love and beauty in Petrarch’s sonnets

- The representation of monarchy in “The Faerie Queene”

- The depiction of the New World in “Utopia”

- The power of speech in “Othello”

- Metaphysical poetry and John Donne

- Tragedy and revenge in “Hamlet”

- Women in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

- The concept of the ideal ruler in Machiavelli’s “The Prince”

- Religion and superstition in “Macbeth”

- The use of satire in Jonathan Swift’s works

- Romantic love in “Pride and Prejudice”

- The depiction of the bourgeoisie in “Candide”

- The role of women in “Moll Flanders”

- The critique of society in “Gulliver’s Travels”

- The supernatural in “The Castle of Otranto”

- Enlightenment principles in “Persuasion”

- The concept of sensibility in “Sense and Sensibility”