Nike and child labour – how it went from laggard to leader

29 February 2016

For well over a decade, Nike became defined by the term ‘sweatshop labour’. It was simply one of the principal things for which it became famous. Consequently, a good many people saw it as the epitome of uncaring capitalism. It was one of the demons of the anti-capitalist campaigners.

In reality, there was no truth to the idea that the company was wicked or uncaring. It was simply one of the first that had pioneered a new business model, and it was learning the hard way that it’s hugely successful formula had unintended consequences that would have to be dealt with.

Nike was originally founded in 1964 as Blue Ribbon Sports, changing to Nike in 1971. One of the two founders, Phil Knight, came up with the idea while he was at Stanford Business School. At the time, the vast majority of US footwear was manufactured in America. Nike was able to grow quickly using the model of outsourcing production to a network of suppliers in parts of the world where costs were lower.

Nike didn’t own the factories. In a very real sense, Nike has never manufactured a single shoe in its entire history. And because it didn’t own the factories, the assumption was that running them was business of the owners, not Nike. In its early decades of existence, there was apparently no evidence of any problem that challenged that assumption.

But by the 1990s, the world was changing. Economic deregulation was leading to a huge increase in the globalisation of the economy, and as the scale of global corporate activity was ramping up, the negative consequences were becoming highly visible. Consequently, the US and European home markets began to hear more about working conditions in foreign factories. Nike was neither better nor worse than any of its peers at this point. The whole outsourced industry was based on the premise of “ignorance is bliss”. But ignorance was proving more and more difficult to maintain.

The company began to make changes. It revised its factory code of conduct, and hired auditing firms to carry out safety checks. But by and large, it was still left to the factory owners to sort themselves out while Nike negotiated for the lowest possible prices.

Everything changed in 1996. Life magazine published a story that included a photograph of a child stitching footballs that carried the Nike logo. There is some evidence that the photo was staged, since it showed inflated footballs while in reality the balls were shipped uninflated. It didn’t matter. The picture was a powerful visual for a situation that was shown to genuinely exist. The company’s reputation suffered and the first of many protests began to take place.

By 1998, the company accepted it needed to take responsibility. Phil Knight admitted “the Nike product has become synonymous with slave wages, forced overtime and arbitrary abuse.” It was going to be a longer journey than they might have imagined. Nike and child labour had become indelibly linked in the public consciousness.

Nike began to take the first steps. It released the names and locations of its factories. It changed elements of its shoe manufacture to reduce hazards to the workers who make them. It began producing reports to talk about its progress. And it put more focus on audits of factories to identify problems.

Still, the popular view of the company as a villain refused to go away. In 2001, one particular incident summed up the problem. The company had offered customers the ability to have a word of their choice stitched onto their new Nike trainers. One enterprising critic requested that the word ‘sweatshop’ should be used for his shoes. The company’s refusal was one of the first examples of a viral internet phenomenon as the email exchange got shared widely across the world.

Organisations such as ‘NikeWatch’ and the Clean Clothes Campaign expressed skepticism about Nike’s efforts, taking a cynical view of its seriousness and sincerity.

But by 2005, the company’s steady progress began to gain grudging respect from some of the campaign groups, and it seemed like the mood music might begin to change. Then just at that point, there came a crisis that threatened to take it right back to the beginning.

In the run-up to the 2006 World Cup, photos were presented to the company of pictures of Pakistani children stitching Nike footballs – a direct repeat of what had happened ten years earlier. It turned out that the supplier, Saga Sports, having become overwhelmed with orders linked to the approaching World Cup, had gone against the rules by sending balls out to be made at local homes.

There was a significant cost to dealing with this problem. To recall the balls would cost $100m short term, and it would delay future production considerably. The company decided to pull the product anyway and to cancel its contract with Saga, moving instead to Silver Star where all work would be done on factory premises.

It was a short-term financial blow, but it sent a strong signal to the company’s suppliers and its customers at the same time, that it was serious about tackling the problem.

The impact on former supplier Saga was enormous, essentially driving it to bankruptcy. Other suppliers based in Sialkot, Pakistan took careful note.

Nike has shown itself to be willing to take other tough decisions, for instance pulling support from a major low cost supplier in Bangladesh because it was impossible to provide working conditions that met decent standards. This was a move that gave it a competitive disadvantage when others were exploiting Bangladesh as the lowest possible cost base. But it left the company less exposed when the Rana Plaza building disaster took place and hard questions began to be asked about who was doing what.

Now, Nike finds itself more often at the top of lists for sustainable companies, particularly within its sector. It appears in the top ten of the Fortune Most Admired Companies list. Its commitment to improving its environmental impact, providing transparency about its processes, and ensuring decent working conditions in its supply chain, have turned the tide of public perception.

Now the company is more often to be found on the front foot when it comes to matters of integrity. For instance, when boxer Manny Pacquiao recently made anti-gay comments during a media interview, Nike dissolved its partnership with him the very next day, labelling his comments “abhorrent.”

The company’s turnaround has become one of the success stories of corporate integrity in the last two decades.

Subscribe to the Mallen Baker podcast for change makers

Subscribe to Updates

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

We will never share your details with any third party

Clear reflection

Are bees going extinct, should we eat meat, climate change and collapse the paper scaring a generation.

- New Idea Food Newsletter

- Australian Celebrities

- King Charles

- Queen Camilla

- Prince William

- Kate Middleton

- Prince Harry

- Meghan Markle

- Tips & Advice

- Home & Tech

- Latest Shopping Guides

- Health & Wellbeing

- Homes To Love

- Home Beautiful

- Better Homes and Gardens

- Hard to Find

- Your Home and Garden

- Shop Your Home & Garden

- Now to Love

- Now to Love NZ

- That's Life

- Women's Weekly

- Women's Weekly Food

- NZ Woman's Weekly Food

- Gourmet Traveller

- Bounty Parents

- marie claire

- Beauty Heaven

- Beauty Crew

- ENTERTAINMENT

Nike sweatshops: inside the scandal

Their brand celebrates humanity and all its potential, but Nike has a history of treating its workers as if they were not human at all.

In 1991, American labour activist Jeffrey Ballinger published a report on Nike’s factory practices in Indonesia, exposing a scandal: below-minimum wages, child labour and appalling conditions likened to a sweatshop – a factory or workshop where employees work long hours for low money in conditions that are hazardous to health.

US College student Jim Keady also delved into Nike’s inhumane production practices in the 90s, and in his film Behind the Swoosh exposed how workers, who were paid $US1.25 per day, were forced to live in slums near open sewers, and shared toilets and bathwater with multiple families.

And in 1996, Life magazine ran a reportage on child labour that included a shocking photo of a 12-year-old Pakistani boy sewing a Nike soccer ball.

Native ad body.

A new Hells Angels documentary reveals the dark secrets of the notorious club

Terminal cancer at 35: “You’re never too young”

“Tash was more than the girl in the cupboard”: The woman at the centre of the famous case has died

The story of Dorothea Puente: The landlady serial killer’s house of horrors!

Aussie victim tells… “I was stalked like baby reindeer”

Shocking true story behind Boy Swallows Universe

The AFL umpires who got engaged on live TV have a baby on the way!

Addicted to takeout… So I lost 60kg!

The Most Haunted: 10 Real Ghost Videos

Sweatshops are common in developing countries, including in Indonesia, India, Thailand, Bangladesh and Cambodia, where labour laws are rarely enforced.

The factories, which are often housed in deteriorating buildings, are cramped with workers and pose fire dangers. Workers are also restricted access to the toilet and drinking water during the day.

Companies such as Nike and Adidas will spruik the line that their factories have strict codes of conduct, but it is difficult to know if those codes are enforced in developing countries. As the world fumed over Nike’s apparent lack of regard for its foreign workers in the 90s, the American company pledged to overhaul the appalling conditions.

But was it lip service, or did they actually do something?

In 2001, Leila Salazar, corporate accountability director for Global Exchange, told The Guardian : “During the last three years, Nike has continued to treat the sweatshop issue as a public relations inconvenience rather than as a serious human rights matter.”

The company disagreed. ”I think we’ve made significant strides, and I’m proud of what the company has done over the last three years,” said Nike’s chairman Phil Knight. “It may take a while longer, but I do think that it will be understood that Nike is a good citizen in all the countries that it operates in.”

In 2007, as the world began embracing “corporate responsibility,” Nike provided a list of its 700 factories around the world as a way of allowing others to check if it was adhering to its policies. Nike spokesman Lee Weinstein said he hoped the report will “move the industry forward in addressing some of these endemic issues.”

Many were skeptical of the move.

“It’s good information to have,” Ballinger told NBC News at the time. “But I’ve always viewed their corporate responsibility work as trying to put the best face on the situation and not necessarily dealing with the issues workers have raised.”

So where does Nike stand today?

According to the ethical clothing advocacy group Good On You, Nike is certified under the Fair Labor Association Workplace Code of Conduct. But a 2018 report by the Clean Clothes Campaign, found that Adidas and Nike still pay “poverty” wages to workers. The report called on both Nike and Adidas to commit to paying “living” wages (the amount of income needed to provide a decent standard of living) to its workers.

With an annual revenue of over $US30 billion it should be able to afford it.

Related stories

Want 15% off at the iconic.

Sign-up to the latest news from New Idea.

Disclaimer: By joining, you agree to our Privacy Policy & Terms of Use

Case 17A.2 Sweatshop wars: Nike and its opponents in the 1990s [i]

In the 1990s, US-based Nike Inc., the largest athletic shoe company in the world, was accused by labour and human rights activists of operating sweatshops in Indonesia, Vietnam and China. Nike initially viewed such accusations as public relations problems, but finally changed its defensive tactics to a more proactive approach after serious damage was inflicted to its reputation in the late 1990s.

In the new millennium, Nike has tried to distance itself from its tainted image associated with worker exploitation, by monitoring its contractors more closely, integrating its supply chain through lean manufacturing and pushing for consistent global standards in the apparel industry. Ultimately, Nike had to learn the lesson of corporate social responsibility in a very hard way.

History and Nike’s business model

Nike started as a venture in 1964 between Phil Knight, an undergraduate and athlete at the University of Oregon, and Bill Bowerman, his track coach at the same university. They identified a need for high-quality running shoes at a time when Adidas and Puma dominated the American market. Phil Knight went on to do his MBA at Stanford, where he realized that he could combine inexpensive Japanese labour and American distributors to sell cheap but high-quality track shoes in the US, thereby ending the European dominance of the market. In 1964, Knight and Bowerman founded the Blue Ribbon Sports Company, which was re-named Nike in 1971.

Nike’s business model had three major components. First, Nike would outsource all manufacturing to low-cost areas in the world. The money thus saved would be invested in the two other components of the business model: research and development of innovative new products on the upstream side, and marketing to promote these products on the downstream side. In its marketing, Nike went beyond conventional celebrity endorsements and actually named Nike shoes after famous athletes such as Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods. These celebrities further strengthened Nike’s image.

This business model worked very well. In the early 1980s, Nike became the leading athletic shoe company in the US. In 1991, Nike became the first sports company to surpass yearly sales of US $3 billion. During this time, Nike shifted its contract manufacturing locations, first from Japan to South Korea and Taiwan, and then later to Indonesia, Vietnam and China, always taking advantage of the cheapest labour in the new emerging economies.

Labour rights in Indonesia and Nike’s initial response to criticisms

By 1990, Indonesia had become a key location for Nike. Labour costs in Indonesia were only 4 per cent of those prevailing in the US. Moreover, Indonesia had a population of 180 million, with a high unemployment rate and weak employment legislation. To Nike, that meant millions of people willing to work for low wages. Six of Nike’s contract manufacturers were located in Indonesia, together employing around 24,000 workers and producing 8 per cent of Nike’s global output.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Indonesia started to experience labour unrest. The number of strikes reported by the Indonesian government rose from 19 in 1989 to 122 in 1991, and Indonesian newspapers also documented some labour abuses by Indonesian factories. An NGO called the Asian-American Free Labor Institute (AAFLI) produced a report on working conditions at Indonesian factories in 1991, based on research by Jeff Ballinger, a labour activist assigned to be the Indonesian branch leader of the AAFLI in 1988.

Ballinger found that his criticism of Indonesia in general did not draw worldwide attention to labour rights abuses in Indonesia. The criticism lacked focus, and it was unclear what sympathetic people in developed countries could do to help the situation. Then Nike emerged as the perfect target for Ballinger: Nike contractors paid their workers less than US $1 a day; Nike contractors hired children in Indonesia; and moral outrage could be capitalized upon to tarnish Nike’s brand names and image. Applying the more focused ‘one country-one company’ strategy, Ballinger started to publish reports and distribute newsletters specifically about labour issues at Nike’s contractors in Indonesia.

In January 1992, as a result of criticism from activists like Ballinger, the Indonesian government increased the minimum daily wage to 2500 rupiah (US $1.24). Nike was aware of the labour conditions at its Indonesian contractors, but it believed that such issues were its contractors’ responsibility, as Nike did not own any manufacturing facilities itself. Firm in its stance, Nike did draft a Code of Conduct in 1992, addressing issues of child labour, forced labour, compensation, benefits, hours of work/overtime, environment, safety and health.

Until that point, criticism of Nike’s Indonesian operations came almost exclusively from Indonesia itself.

Criticism spreads to the US: Nike’s hot seat

However, it didn’t take long before Nike was criticized in the US media too. In 1992, Harper’s Magazine published an article by Ballinger, famously demonstrating that it would take an Indonesian factory worker 44,492 years to earn Michael Jordan’s endorsement fee at Nike. [ii] In the same year, a prominent newspaper in Oregon (Nike’s home state) also published articles criticizing Nike’s Indonesian operations. In 1993, a CBS report revealed that Indonesian workers at a Nike contractor’s factory were paid only 19 cents an hour, and that women employees could only leave their on-site dormitory on Sundays and with written management permission.

Such criticism drew national attention, but Nike’s stance was still firm. Nike argued that it had provided job opportunities and contributed to local economic development. Phil Knight, Nike’s CEO, dismissed any criticism, stating “I’m proud of our activities.” [iii] He argued that, taken in context, Nike was benefiting Indonesia: “A country like Indonesia is converting from farm labour to semiskilled – an industrial transition that has occurred throughout history. There’s no question in my mind that we’re giving these people hope.” [iv]

Further, Nike responded to the above criticism by hiring Ernst & Young, the accounting and consulting firm, to audit Nike’s foreign factories, but the objectivity of the auditing was questioned by activists.

In the next several years, criticism directed towards Nike continued to rise. In April 1996, Kathie Lee Gifford, a popular daytime talk show host at CBS, had learnt from human rights activists that a line of Wal-Mart clothing endorsed by her had been manufactured by child labour in Honduras. She soon apologized on national television, spurring a wave of media coverage on labour issues in developing countries associated with other Western companies. In July 1996, Life magazine published an article about child labour at Nike’s contractors in Pakistan. Then, on 17 October 1996, CBS News ran a 48 Hours programme focusing on Nike’s shoe manufacturing plants in Vietnam, reporting low wages, physical violence inflicted on employees and sexual abuses of several women workers. The programme informed US viewers that temporary workers were paid only 20 cents an hour. On 14 March 1997, Reuters reported physical abuses of workers at Nike contractors’ factories in Vietnam. As a result of such widespread negative news coverage, Nike gradually emerged as a symbol of worker exploitation.

Such news coverage also drew the attention of political leaders to look for legislative solutions. In 1996, Robert Reich, the US labour secretary, launched a campaign to “eradicate sweatshops from the American garment industry and erase the word entirely from the American lexicon”. [v] Even President Clinton convened a presidential task force on sweatshops and called for industry leaders to develop acceptable labour standards in foreign factories. [vi]

To quell the above criticisms, Nike tried to build credibility in two main ways. First, Nike established a Labour Practices Department in October 1996 and a Corporate Responsibility Department in 1998, to deal formally with worker issues in its supply chain. Second, in 1997, Nike hired Andrew Young, a former UN ambassador and civil rights leader, to review Nike’s Far Eastern factories. However, Andrew Young’s conclusion from his 10-day visit to China, Vietnam and Indonesia that Nike was doing a good job was publicly challenged at the time and later shown to be flawed. [vii]

How Nike solved its sweatshop problem

- By GlobalPost Writer Max Nisen, Business Insider

The ‘Swoosh’ logo is seen on a Nike factory store on December 12, 2009 in Orlando, Florida.

It wasn't that long ago that Nike was being shamed in public for its labor practices to the point where it badly tarnished the company's image and hurt sales.

The recent factory collapse in Bangladesh was a reminder that even though Nike managed to turn around its image, large parts of the industry still haven't changed much at all.

Nike was an early target for the very reason it's been so successful. Its business model was based on outsourcing its manufacturing , using the money it saved on aggressive marketing campaigns.

Nike has managed to turn its image around. Nike hasn't been completely successful in bringing factories into line, but there's no denying that the company has executed one of the greatest image turnarounds in recent decades.

Here's the timeline of how Nike became a global symbol of abusive labor practices, then managed to turn things around:

- After prices rose and labor organized in Korea and Taiwan, Nike begins to urge contractors to move to Indonesia, China, and Vietnam.

- 1991 : Problems start in 1991 when activist Jeff Ballinger publishes a report documenting low wages and poor working conditions in Indonesia.

- Nike first formally responds to complaints with a factory code of conduct .

- 1992 : Ballinger publishes an exposé of Nike. His Harper's article highlights an Indonesian worker who worked for a Nike subcontractor for 14 cents an hour, less than Indonesia's minimum wage, and documented other abuses.

- 1992-1993 : Protests at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992, CBS ' 1993 interview of Nike factory workers, and Ballinger's NGO "Press For Change" provokes a wave of mainstream media attention.

- 1996 : Kathy Lee Gifford's clothing line is shown to be made by children in poor labor conditions . Her teary apology and activism makes it a national issue.

- 1996 : Nike establishes a department tasked with working to improve the lives of factory laborers.

- 1997 : Efforts at promotion become occasions for public outrage. The company expands its "Niketown" retail stores, only to see increasing protests. Sports media begin challenging spokespeople like Michael Jordan .

- Abuses continue to emerge, like a report that alleging that a Vietnamese sub-contractor ran women outside until they collapsed for failing to wear regulation shoes.

- Nike tasks diplomat and activist Andrew Young with examining its labor practices abroad. His report is criticized for being soft on Nike. Critics object to the fact that he didn't address low wages, used Nike interpreters to translate, and was accompanied by Nike officials on factory visits. Since Young's report was largely favorable, Nike is quick to publicize it, which increases backlash .

- 1997 : College students around the country began protesting the company.

- 1998 : Nike faces weak demand and unrelenting criticism. It has to lay off workers, and begins to realize it needs to change.

- The real shift begins with a May 1998 speech by then-CEO Phil Knight. “The Nike product has become synonymous with slave wages, forced overtime, and arbitrary abuse,” Knight said. “I truly believe the American consumer doesn’t want to buy products made under abusive conditions.”

- At that speech, he announces Nike will raise the minimum age of workers; significantly increase monitoring; and will adapt US OSHA clean air standards in all factories.

- 1999: Nike begins creating the Fair Labor Association , a non-profit group that combines companies, and human rights and labor representatives to establish independent monitoring and a code of conduct, including a minimum age and a 60-hour work week, and pushes other brands to join.

- 2002-2004 : The company performs some 600 factory audits between 2002 and 2004, including repeat visits to problematic factories.

- 2004: Human rights activists acknowledge that increased monitoring efforts at least deal with some of the worst problems, like locked factory doors and unsafe chemicals, but issues still remain.

- 2005 : Nike becomes the first in its industry to publish a complete list of the factories it contracts with.

- 2005: Nike publishes a detailed 108-page report revealing conditions and pay in its factories and acknowledging widespread issues, particularly in its south Asian factories.

- 2005-Present : The company continues to post its commitments, standards, and audit data as part of its corporate social responsibility reports .

Nike wasn't the only or worst company to use sweatshops. But it was the one everybody knew.

Transparency doesn't change ongoing reports of abuses , still-low wages, or tragedies like the one in Bangladesh.

But by becoming a leader instead of denying every allegation, Nike has mostly managed to put the most difficult chapter in its history behind it and other companies who outsource could stand to learn a few things from Nike's turnaround.

More from our partner, Business Insider :

Business Insider: This National Geographic documentary got an American sentenced to 15 years hard labor in North Korea

Business Insider: Here's a timeline of the US military's camouflage disaster

Business Insider: Deadly SARS-like virus spreads to France and Saudi Arabia

Business Insider: Facebook is about to launch a huge play in 'big data' analytics

Business Insider: Manchester United's new coach once sued Wayne Rooney for libel

Sign up for The Top of the World, delivered to your inbox every weekday morning.

SustainCase – Sustainability Magazine

- trending News

- Climate News

- Collections

- case studies

Case study: How Nike solved its sweatshop problem

With this article, we present actions Nike has taken through the years to solve its sweatshop problem, using information published in its GRI Standards-based CSR/ ESG/ Sustainability reports.

See what action Nike has taken through the years to solve its sweatshop problem

Subscribe for free and read the rest of this article

Please subscribe to the SustainCase Newsletter to keep up to date with the latest sustainability news and gain access to over 2000 case studies. These case studies demonstrate how companies are dealing responsibly with their most important impacts, building trust with their stakeholders (Identify > Measure > Manage > Change).

Already Subscribed? Type your email below and click submit

Nike is continuously tackling its most important environmental, economic and social impacts with the use of the GRI Standards for CSR/ ESG/ sustainability reporting: an all-round, complete, structured, and methodical approach used by 80% of the world’s 250 largest companies.

- Promoting worker-management dialogue: Nike took action to facilitate worker-management dialogue in contract factories through permanent ESH (Environment, Safety and Health ) committees, training both workers and management to engage in constructive dialogue.

- Directly intervening to protect workers’ rights: When workers’ rights are not adequately protected by others and Nike believes it can influence the outcome, it may directly intervene, often seeking advice from external stakeholders with expertise on a topic.

- Supporting transparency: Nike became the first company in its industry to publish online the names and addresses of all contract factories manufacturing Nike-brand products, constantly updating this list.

- Monitoring Nike and contract factories: In addition to regular management audits in factories, Nike carries out deeper studies called Management Audit Verifications (MAV), which are both an audit and verification in one tool. The MAV tool is focused on four core areas: hours of work, wages and benefits, labour relations and grievance systems.

- Compliance with legally-mandated work hours

- Use of overtime only when employees are fully compensated according to local law

- Informing employees at hiring if compulsory overtime is a condition of employment

- Regularly providing one full day off in every seven and requiring no more than 60 hours of work per week

- Setting industry-leading compliance standards: Contract factories in Nike’s supply chain are subject to strict compliance requirements, starting with risk analysis of the host country and Nike’s Code of Conduct. Additionally, Nike’s internal team of more than 150 trained experts monitors, amends and provides improvement tools to the factories. Nike regularly audits contract factories, with assessments taking the form of audit visits, both announced and unannounced, by internal and external parties, and works with accredited third parties, such as the Fair Labor Association (FLA), to carry out independent monitoring.

- Helping contract factories protect workers’ health and safety: Nike helps its contract factories put in place comprehensive HSE (Health, Safety and Environment) management systems which focus on the prevention, identification and elimination of hazards and risks to workers, expecting its contract factories to perform better than industry averages in injuries and lost-time accidents.

- Forbidding the use of child labour: Nike specifically and directly forbids the use of child labour in facilities contracted to manufacture its products. Nike’s Code of Conduct requires that workers must be at least 16 years old or past the national legal age of compulsory schooling and minimum working age, whichever is higher. In addition, Nike’s Code Leadership Standards include specific requirements on how suppliers should verify workers’ age prior to starting employment and actions a facility must take if a supplier violates Nike’s standards.

- Promoting workers’ freedom of association: Nike’s Code Leadership Standards contain detailed requirements on how suppliers must respect workers’ rights to freely associate, including prohibitions on interference with workers seeking to organise or carry out union activities.

How Nike conducts stakeholder engagement

Nike benefits from constructive guidance from a number of external stakeholders, including civil society organisations, industry, government, investors, consumers and others. To identify and better understand emerging sustainability issues Nike works with Ceres (a sustainability nonprofit organisation), convening an external stakeholder panel and carrying out multiple dialogues that guide the development of its approach to reporting and communication.

How Nike solved its sweatshop problem

It was only 20 years ago that Nike was facing child labour and sweatshop allegations, with consumers protesting outside Niketown stores. All this is hard to believe, given the steady stream of corporate social responsibility (CSR) accolades in the last 10 years.

In 1998, then-CEO Phil Knight promised change. The company struggled to put new policies in place and enforce them. In 2005, Nike published its first version of a CSR/ ESG/ Sustainability report – in which it detailed pay scales and working conditions in its factories and admitted continued problems – and took the dramatic step of publicly disclosing the names and addresses of contract factories producing Nike products – the first company in its industry to do so.

More recently, Nike made this information available on an Interactive Global Manufacturing Map ; there, you can click on a factory to see its name, number of workers, percentage of female and migrant workers and what’s made there. A major change from the days when Nike faced accusations of labour rights in its supply chain, it takes transparency to a whole new level.

Nike recognised its issues, demonstrated transparency and worked toward change – and, today, it is counted among CSR/ ESG/ Sustainability leaders.

Which Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been addressed?

The SDGs addressed in this case are:

- Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 : Ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all at all ages

- Business theme: Occupational health and safety

- Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 5 : Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls

- Business theme: Workplace violence and harassment

- Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 : Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all

- Business theme: Occupational health and safety, Freedom of association and collective bargaining, Abolition of child labor, Elimination of forced or compulsory labor, Labor practices in the supply chain

- Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16 : Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels

- Business theme: Abolition of child labor, Labor practices in the supply chain

78% of the world’s 250 largest companies report in accordance with the GRI Standards

SustainCase was primarily created to demonstrate, through case studies, the importance of dealing with a company’s most important impacts in a structured way, with use of the GRI Standards. To show how today’s best-run companies are achieving economic, social and environmental success – and how you can too.

Research by well-recognised institutions is clearly proving that responsible companies can look to the future with optimism .

7 GRI sustainability disclosures get you started

Any size business can start taking sustainability action

GRI, IEMA, CPD Certified Sustainability courses (2-5 days): Live Online or Classroom (venue: London School of Economics)

- Exclusive FBRH template to begin reporting from day one

- Identify your most important impacts on the Environment, Economy and People

- Formulate in group exercises your plan for action. Begin taking solid, focused, all-round sustainability action ASAP.

- Benchmarking methodology to set you on a path of continuous improvement

See upcoming training dates.

References:

This article was compiled using an article from the links below. For the sake of readability, we did not use brackets or ellipses but made sure that the extra or missing words did not change the article’s meaning. If you would like to quote these written sources from the original please revert to the links below:

http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/jan/02/billion-dollar-companies-sustainability-green-giants-tesla-chipotle-ikea-nike-toyota-whole-foods

http://www.businessinsider.com/how-nike-solved-its-sweatshop-problem-2013-5

http://www.triplepundit.com/special/roi-of-sustainability/how-nike-embraced-csr-and-went-from-villain-to-hero/

TED Case Study: NIKE: Nike Shoes and Child Labor in Pakistan

| dc.contributor.author | China Labor Watch | 2020-12-08T21:46:25Z | 2020-12-08T21:46:25Z | 2010-01-01 | This document is part of a digital collection provided by the Martin P. Catherwood Library, ILR School, Cornell University, pertaining to the effects of globalization on the workplace worldwide. Special emphasis is placed on labor rights, working conditions, labor market changes, and union organizing. | CLW_2010_Report_China_Ted_Nike.pdf: 4924 downloads, before Oct. 1, 2020. | 7922382 | https://hdl.handle.net/1813/101227 | en_US | conditions |

| dc.subject | global | |

| dc.subject | globalisation | |

| dc.subject | globalization | |

| dc.subject | human | |

| dc.subject | international | |

| dc.subject | labor | |

| dc.subject | labour | |

| dc.subject | rights | |

| dc.subject | standards | |

| dc.subject | trade | |

| dc.subject | work | |

| dc.subject | worker | |

| dc.subject | working | |

| dc.subject | workplace | |

| dc.subject | forced labor | |

| dc.subject | forced labour | TED Case Study: NIKE: Nike Shoes and Child Labor in Pakistan | article | China Labor Watch: True |

Original bundle

Collections

Make a deposit on ecommmons, please sign in with your cornell netid to continue..

- Resources +

- Daily Links

- Group Subscriptions

- Subscriptions

- Mission & Values

- Editor-in-Chief

Image: Nike

Sweatshops Almost Killed Nike in the 1990s, Now There are Modern Slavery Laws

One of the biggest threats to a retailer’s reputation is an allegation of involvement in slavery, human trafficking, or child labor. ask nike. in the 1990s, the portland-based sportswear giant was plagued with damning reports that its global supply chain was being ....

September 27, 2019 - By TFL

Case Documentation

One of the biggest threats to a retailer’s reputation is an allegation of involvement in slavery, human trafficking, or child labor. Ask Nike. In the 1990s, the Portland-based sportswear giant was plagued with damning reports that its global supply chain was being supported by child labor in places like Cambodia and Pakistan, with minors stitching soccer balls and other products as many as seven days a week for up to 16 hours a day. All the while, sweatshop conditions were running rampant in factories Nike maintained contracts with, and minimum wage and overtime laws were being flouted with regularity.

The backlash against Nike was so striking that it served to tarnish the then-30 year old company’s image and negatively affect its bottom line. “Sales were dropping and Nike was being portrayed in the media as a company that was willing to exploit workers and deprive them of the basic wage needed to sustain themselves in an effort to expand profits,” according to Stanford University research.

That was not the case according to Nike’s chairman and chief executive at the time Phil Knight, who told the New York Times in 1998 that he “truthfully [did not] think that there has been a material impact on Nike sales by the human rights attacks,” and pointed instead, to “the financial crisis in Asia, where the company had been expanding sales aggressively, and its failure to recognize a shifting consumer preference for hiking shoes.”

Yet, the company was, nonetheless, forced to spend the next decade cleaning up its act in order to hold on to – and in some cases, win back – consumers, from overhauling its supply chain oversight efforts to include independent monitoring and audits to releasing public-facing vows to “root out underage workers and require overseas manufacturers of its wares to meet strict United States health and safety standards.”

It is critical to note that Nike took hits for its nefarious labor practices long before consumers were readily learning about and connecting with brands on social media, and during a time when retailers’ supply chains were generally less expansive than they are today. Fast forward to 2019 and with the rise of digital media and social media, and the larger trend towards cause-oriented consumerism, paired with the increasingly complicated and multi-national nature of corporate entities’ supply chains, the stakes are significantly higher than they were in the 1990s.

The demands and the level of risk at play is exacerbated by the fact that shoppers, particularly of the millennial type, are actively calling on fashion brands and retailers to be transparent in terms of how and where their products are made. But even more than consumer-driven calls for clarity and principled activity, in many jurisdictions, the law requires it. For instance, in the United Kingdom, the Modern Slavery Act of 2015 requires commercial entities that have a global turnover above £36 million ($43.5 million) to publicly file an annual slavery and trafficking statement, highlighting what steps – if any – they are taking to combat trafficking and slavery in their operations and supply chains.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., California passed the Transparency in Supply Chains Act in January 2012, thereby requiring retailers and manufacturers with global revenues that exceed $100 million and which do business in California (a low bar given the sheer size of California’s economy and the sweeping business ties that come about as a result of e-commerce operations) to publicly disclose the degree to which they are addressing forced labor and human trafficking in their global manufacturing networks.

Two years later, the Federal Business Supply Chain Transparency on Trafficking and Slavery Bill was introduced to the House of Representatives. The bill proposed required all companies with worldwide annual sales exceeding $100 million, and which are currently required to file annual reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission, are to disclose what measures, if any, they have taken to identify and address conditions of forced labor, slavery, human trafficking and child labor within their supply chains, either in the U.S. or abroad.

Although not ultimately enacted, the bill “demonstrates the continued attention that the issues of forced labor, slavery, human trafficking, and child labor in manufacturers’ supply chains is receiving in the U.S. and around the world,” according to Pittsburg-headquartered law firm K&L Gates .

Still yet, since then, the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (“TVPA”) has come into effect. As the first comprehensive federal law to address modern slavery, the TVPA creates a private right of action for victims of forced labor against third parties, such as fashion brands and retailers, that benefit from participating in a venture if they knew or “should have known” that the venture engaged in modern slavery. In other words, the TVPA imposes civil liability for corporate negligence.

Looking beyond the fact that supply chain oversight and accountability is a legal issue in many jurisdictions, it is worth noting that avoiding supply chain scandals, and in fact, being able to point to efforts aimed at transparency, is just good business. Given consumers’ increasing interest in the supply chains of their favorite brands and with the potential damage that could come about – potentially, virally – as a result of ties to slavery, human trafficking, and/or child labor, companies are being advised to consistently assess and identify potential instances of slavery and trafficking risks in their operations and supply chains, and prioritize those risks for further investigation and/or action.

In furtherance of such efforts, retailers and fashion brands are encouraged to exercise due diligence before entering into a supply agreement or contract, including requiring the supplier to provide information necessary to establish whether or not it – or any of its sub-contractors and sub-suppliers – are involved in misconduct.

Contractually speaking, brands should establish and require that their the suppliers, in performing their obligations under the agreement, comply with an anti-slavery policy and with all applicable anti-slavery and human trafficking laws, statutes, regulations and codes in force, and also require the supplier to include similar provisions in its own contracts with its sub-contractors and sub-suppliers.

Ideally, a brand’s contract with a supplier should include terms to prevent the supplier from sub-contracting or sub-supplying without its written consent, thereby giving the retailer the opportunity to vet the third party and veto the engagement if necessary; and it should require the supplier to maintain documentary evidence of the age of each of its employees to ensure that minimum legal age requirements are being met.

However, in many cases, this has proven futile from a practical perspective even with dedicated oversight, as contracting and sub-contracting runs rampant in many manufacturing centers, such as Bangladesh, particularly when there are “tight deadlines to meet and/or unanticipated orders” at play, according to the not-for-profit Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations . In these instances, “manufacturers subcontract certain production processes to other factories and workplaces, without informing the buyer.

Because brands and retailers may inadvertently become involved if malpractice claims are risen in connection with their supply chains, turning a blind eye or failing to take active steps to prevent slavery will not be sufficient in the eyes of the law or consumers.

Nicola Conway is a Trainee Solicitor at Bryan Cave in London. Edits/additions courtesy of TFL.

related articles

How AI is Poised to Radically Disrupt the Fashion Industry

August 29, 2024 - By Luana Carcano

FTC v. Tapestry: A Case Over M&A in the “Accessible Luxury” Market

August 28, 2024 - By Julie Zerbo

How Should Companies Measure Carbon Risk Exposure?

August 28, 2024 - By Gianfranco Gianfrate

Ganni Beats Out Steve Madden in Case Over “Copycat” Shoe

August 27, 2024 - By TFL

Learning Materials

- Business Studies

- Combined Science

- Computer Science

- Engineering

- English Literature

- Environmental Science

- Human Geography

- Macroeconomics

- Microeconomics

- Nike Sweatshop Scandal

Nike is one of the largest athletic footwear and clothing companies in the world, but its labour practices have not always been ethical. Back in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the company was accused of using sweatshops to make activewear and shoes. Despite an initial slow response, the company eventually took measures to improve the working conditions of employees in its factories. This has allowed it to regain public trust and become a leading brand in the sportswear sector. Let's take a closer look at Nike's Sweatshop Scandal and how it has been resolved.

Create learning materials about Nike Sweatshop Scandal with our free learning app!

- Instand access to millions of learning materials

- Flashcards, notes, mock-exams and more

- Everything you need to ace your exams

Millions of flashcards designed to help you ace your studies

- Cell Biology

what year was Nike founded?

Life magazine in America did a report on child labour in 1996, which included a shocking photo of a 12-year-old boy sewing a Nike football. What country was he from?

What was the nike sweatshop scandal about?

Does nike sweatshop scandal involve human rights violations?

What is the main reason Nike is considered unethical?

Was Nike involved in child labour?

In what year did Nike created the Fair Labour Association, which was created to oversee the company's 600 factories?

In what year did the company started improving the conditions of its factories?

Where was the first Nike store to be open?

When was Nike first founded?

What is corporate social responsibility?

Review generated flashcards

to start learning or create your own AI flashcards

Start learning or create your own AI flashcards

- Business Case Studies

- Amazon Global Business Strategy

- Apple Change Management

- Apple Ethical Issues

- Apple Global Strategy

- Apple Marketing Strategy

- Ben and Jerrys CSR

- Bill And Melinda Gates Foundation

- Bill Gates Leadership Style

- Coca-Cola Business Strategy

- Disney Pixar Merger Case Study

- Enron Scandal

- Franchise Model McDonalds

- Google Organisational Culture

- Ikea Foundation

- Ikea Transnational Strategy

- Jeff Bezos Leadership Style

- Kraft Cadbury Takeover

- Mary Barra Leadership Style

- McDonalds Organisational Structure

- Netflix Innovation Strategy

- Nike Marketing Strategy

- Nivea Market Segmentation

- Nokia Change Management

- Organisation Design Case Study

- Oyo Franchise Model

- Porters Five Forces Apple

- Porters Five Forces Starbucks

- Porters Five Forces Walmart

- Pricing Strategy of Nestle Company

- Ryanair Strategic Position

- SWOT analysis of Cadbury

- Starbucks Ethical Issues

- Starbucks International Strategy

- Starbucks Marketing Strategy

- Susan Wojcicki Leadership Style

- Swot Analysis of Apple

- Tesco Organisational Structure

- Tesco SWOT Analysis

- Unilever Outsourcing

- Virgin Media O2 Merger

- Walt Disney CSR Programs

- Warren Buffett Leadership Style

- Zara Franchise Model

- Business Development

- Business Operations

- Change Management

- Corporate Finance

- Financial Performance

- Human Resources

- Influences On Business

- Intermediate Accounting

- Introduction to Business

- Managerial Economics

- Nature of Business

- Operational Management

- Organizational Behavior

- Organizational Communication

- Strategic Analysis

- Strategic Direction

Nike and sweatshop labour

Like other multinational companies, Nike outsources the production of sportswear and sneakers to developing economies to save costs, taking advantage of a cheap workforce. This has given birth to sweatshops - factories where workers are forced to work long hours at very low wages under abysmal working conditions.

Nike's sweatshops first appeared in Japan, then moved to cheaper labour countries such as South Korea, China, and Taiwan. As the economies of these countries developed, Nike switched to lower-cost suppliers in China, Indonesia, and Vietnam .

Nike's use of sweatshop dates back to the 1970s but wasn't brought to public attention until 1991 when Jeff Ballinger published a report detailing the appalling working conditions of garment workers at Nike's factories in Indonesia.

The report described the meagre wages that the factory workers received, only 14 cents per hour, barely enough to cover basic living costs. The disclosure aroused public anger, resulting in mass protests at the Barcelona Olympics in 1992. Despite this, Nike continued making its plans to expand Niketowns - fa cilities displaying a wide range of Nike-based services and experiences - which fuelled more resentment within consumers.

For more insight into how a company's external economic environment can impact its internal operations, take a look at our explanation on the Economic Environment .

Nike child labour

In addition to the sweatshop problem, Nike also got caught in the child labour scandal. In 1996, Life Magazine published an article featuring a photo of a young boy named Tariq from Pakistan, who was reportedly sewing Nike footballs for 60 cents a day .

From 2001 on, Nike started to audit its factories and prepared a report in which it concluded that it could not guarantee that its products would not be produced by children .

Nike's initial response

Nike initially denied its association with the practices, stating it had little control over the contracted factories and who they hired.

After the protests in 1992, the company took more concrete action by setting up a department to improve factory conditions. However, this didn't do much to resolve the problem. Disputes continued. Many Nike sweatshops still operated.

In 1997-1998, Nike faced more public backlash, causing the sportswear brand to lay off many workers.

How did Nike recover?

A major shift happened when CEO Phil Knight delivered a speech in May 1998. He admitted the existence of unfair labour practices in Nike's production facilities and promised to improve the situation by raising the minimum wage, and ensuring all factories had clean air.

In 1999, Nike's Fair Labor Association was established to protect workers' rights and monitor the Code of Conduct in Nike factories. Between 2002 and 2004, more than 600 factories were audited for occupational health and safety . In 2005, the company published a complete list of its factories along with a report detailing the working conditions and wages of workers at Nike's facilities. Ever since, Nike has been publishing annual reports about labour practices, showing transparency and sincere efforts to redeem past mistakes.

While the sweatshop issue is far from over, critics and activists have praised Nike. At least the company does not turn a blind eye to the problem anymore. Nike's efforts finally paid off as it slowly won back public trust and once again dominated the market.

It is important to note that these actions have had minimal effect on workers' conditions working for Nike. In the 2019 report by Tailored Wages, Nike cannot prove that minimum living wage is being paid to any workers. 6

Protection of workers' human rights

Nike's sweatshops undoubtedly violated human rights. Workers survive on a low minimum wage and are forced to work in an unsafe environment for long periods of time. However, since the Nike Sweatshop Scandal, many non-profit organisations have been set up to protect the rights of garment workers.

One example is Team Sweat, an organisation tracking and protesting Nike's illegal labour practices. It was founded in 2000 by Jim Keady with the goal of ending these injustices.

USAS is another US-based group formed by students to challenge oppressive practices. The organisation has started many projects to protect workers' rights, one of which is the Sweat-Free Campus Campaign . The campaign required all brands that make university names or logos. This was a major success, gathering enormous public support and causing Nike financial loss. To recover, the company had no choice but to improve the factory conditions and labour rights.

Nike's Corporate Social Responsibility

Since 2005, the company has been producing corporate social responsibility reports as part of its commitment to transparency.

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a set of practices a business undertakes in order to contribute to society in a positive way .

Nike's CSR reports revealed the brand's continuous efforts to improve labour working conditions.

For example, FY20 Nike Impact Report, Nike made crucial points on how it protects workers' human rights. The solutions include:

Forbid underage employment and forced labour

Allow freedom of association (Forming of workers' union)

Prevent discrimination of all kind

Provide workers with fair compensation

Eliminate excessive overtime

In addition to labour rights, Nike aims to make a positive difference in the world through a wide range of sustainable practices:

Source materials for apparel and footwear from sustainable sources

Reduce carbon footprint and reach 100% renewable energy

Increase recycling and cut down on overall waste

Adopt new technology to decrease water use in the supply chain

Slowly, the company is distancing itself from the 'labour abuse' image and making a positive impact on the world. It aims to become both a profitable and an ethical company.

Nike sweatshop scandal timeline

1991 - Activist Jeff Ballinger publishes a report exposing low wages and poor working conditions among Indonesian Nike factories. Nike responds by instating its first factory codes of conduct.

1992 - In his article, Jeff Ballinger details an Indonesian worker who was abused by a Nike subcontractor, who paid the worker 14 cents an hour. He also documented other forms of exploitation towards workers at the company.

1996 - In response to the controversy around the use of child labour in its products, Nike created a department that focussed on improving the lives of factory workers.

1997 - Media outlets challenge the company's spokespersons. Andrew Young, an activist and diplomat, gets hired by Nike to investigate its labour practices abroad. His critics say that his report was soft on the company, despite his favourable conclusions.

1998 - Nike faces unrelenting criticism and weak demand. It had to start shedding workers and developing a new strategy. In response to widespread protests, CEO Phil Knight said that the company's products became synonymous with slavery and abusive labour conditions. Knight said:

"I truly believe the American consumer doesn't want to buy products made under abusive conditions"

Nike raised the minimum age of its workers and increased monitoring of overseas factories.

1999 - Nike launches the Fair Labor Association, a not-for-profit group that combines company and human rights representatives to establish a code of conduct and monitor labour conditions.

2002 - Between 2002 and 2004, the company carried out around 600 factory audits. These were mainly focused on problematic factories.

2004 - Human rights groups acknowledge that efforts to improve the working conditions of workers have been made, but many of the issues remain . Watchdog groups also noted that some of the worst abuses still occur.

2005 - Nike becomes the first major brand to publish a list of the factories it contracts to manufacture shoes and clothes. Nike's annual report details the conditions. It also acknowledges widespread issues in its south Asian factories.

2006 - T he company continues to publish its social responsibility reports and its commitments to its customers.

For many years, Nike's brand image has been associated with sweatshops. However, since the sweatshop scandal of the 1990s, the company has made a concerted efforts to reverse this negative image. It does so by being more transparent about labour practices while making a positive change in the world through Corporate Social Responsibility strategies. Nike's CSR strategies not only focus on labour but also other social and environmental aspects.

Nike Sweatshop Scandal - Key takeaways

Nike has been criticised for using sweatshops in emerging economies as a source of labour .

The Nike Sweatshop Scandal began in 1991 when Jeff Ballinger published a report detailing the appalling working conditions of garment workers at Nike's factory in Indonesia.

- Nike's initial response was to deny its association with unethical practices. However, under the influence of public pressure, the company was forced to take action to resolve cases of its unethical working practices.

- From 1999 to 2005, Nike performed factory audits and took many measures to improve labour practices.

- Since 2005, the company also published annual reports to be transparent about its labour working conditions.

- Nike continues to reinforce its ethical image through Corporate Social Responsibility strategies.

- Simon Birch, Sweat and Tears, The Guardian, 2000.

- Lara Robertson, How Ethical Is Nike, Good On You, 2020.

- Ashley Lutz, How Nike shed its sweatshop image to dominate the shoe industry, Business insider, 2015.

- Jack Meyer, History of Nike: Timeline and Facts, The Street, 2019.

- A History of Nike’s Changing Attitude to Sweatshops, Glass Clothing, 2018.

- Tailored Wages Report 2019, https://archive.cleanclothes.org/livingwage/tailoredwages

Flashcards in Nike Sweatshop Scandal 30

Nike has been criticized for using sweatshops in Asia as a source of labour. The company was accused of engaging in abusive and verbal behaviour toward its workers.

Yes. A report by the Washington Post in 2020 stated that Nike doesn't have evidence of a living wage for its workers. The same year, it was revealed that the company uses forced labor in factories.

Nike has been criticized for using sweatshops in Asia as a source of labor. The company was accused of abusing its employees. In addition, some of the factories reportedly imposed conditions that severely affected their workers' restroom and water usage.

Learn with 30 Nike Sweatshop Scandal flashcards in the free StudySmarter app

We have 14,000 flashcards about Dynamic Landscapes.

Already have an account? Log in

Frequently Asked Questions about Nike Sweatshop Scandal

What was the Nike sweatshop scandal about?

Nike has been criticised for using sweatshops in emerging economies as a cheap source of labour that violated the human rights of the workers.

When was the Nike sweatshop scandal?

The Nike Sweatshop Scandal began in 1991 when Jeff Ballinger published a report detailing the appalling working conditions of garment workers at Nike's factory in Indonesia.

Does the Nike sweatshop scandal involve human rights violations?

Yes, the Nike sweatshop scandal involved human rights violations. Workers survive on a low minimum wage and are forced to work in an unsafe environment for long periods of time.

What is the main reason Nike is considered unethical?

The main reason Nike was considered unethical is Human rights violations of workers in its offshore factories.

Discover learning materials with the free StudySmarter app

About StudySmarter

StudySmarter is a globally recognized educational technology company, offering a holistic learning platform designed for students of all ages and educational levels. Our platform provides learning support for a wide range of subjects, including STEM, Social Sciences, and Languages and also helps students to successfully master various tests and exams worldwide, such as GCSE, A Level, SAT, ACT, Abitur, and more. We offer an extensive library of learning materials, including interactive flashcards, comprehensive textbook solutions, and detailed explanations. The cutting-edge technology and tools we provide help students create their own learning materials. StudySmarter’s content is not only expert-verified but also regularly updated to ensure accuracy and relevance.

StudySmarter Editorial Team

Team Business Studies Teachers

- 9 minutes reading time

- Checked by StudySmarter Editorial Team

Study anywhere. Anytime.Across all devices.

Create a free account to save this explanation..

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Join over 22 million students in learning with our StudySmarter App

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

- Flashcards & Quizzes

- AI Study Assistant

- Study Planner

- Smart Note-Taking

- Corpus ID: 155902750

TED Case Study: NIKE: Nike Shoes and Child Labor in Pakistan

- China Labor Watch

- Published 2010

- Law, Sociology

One Citation

El desarrollo de la empatía a través del teatro. un caso práctico: niño mundo de aurora mateos (2015), related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

Nike and child labour – path to sustainability

For well over a decade, Nike became defined by the term ‘sweatshop labour’. It was simply one of the principal things for which it became famous. Consequently, a good many people saw it as the epitome of uncaring capitalism. It was one of the demons of the anti-capitalist campaigners.

In reality, there was no truth to the idea that the company was wicked or uncaring. It was simply one of the first that had pioneered a new business model, and it was learning the hard way that it’s hugely successful formula had unintended consequences that would have to be dealt with.

Nike was originally founded in 1964 as Blue Ribbon Sports, changing to Nike in 1971. One of the two founders, Phil Knight, came up with the idea while he was at Stanford Business School. At the time, the vast majority of US footwear was manufactured in America. Nike was able to grow quickly using the model of outsourcing production to a network of suppliers in parts of the world where costs were lower.

By 2005, the company’s steady progress began to gain grudging respect from some of the campaign groups

Nike didn’t own the factories. In a very real sense, Nike has never manufactured a single shoe in its entire history. And because it didn’t own the factories, the assumption was that running them was business of the owners, not Nike. In its early decades of existence, there was apparently no evidence of any problem that challenged that assumption.

But by the 1990s, the world was changing. Economic deregulation was leading to a huge increase in the globalisation of the economy, and as the scale of global corporate activity was ramping up, the negative consequences were becoming highly visible. Consequently, the US and European home markets began to hear more about working conditions in foreign factories. Nike was neither better nor worse than any of its peers at this point. The whole outsourced industry was based on the premise of “ignorance is bliss”. But ignorance was proving more and more difficult to maintain.

The company began to make changes. It revised its factory code of conduct, and hired auditing firms to carry out safety checks. But by and large, it was still left to the factory owners to sort themselves out while Nike negotiated for the lowest possible prices.

Everything changed in 1996. Life magazine published a story that included a photograph of a child stitching footballs that carried the Nike logo. There is some evidence that the photo was staged, since it showed inflated footballs while in reality the balls were shipped uninflated. It didn’t matter. The picture was a powerful visual for a situation that was shown to genuinely exist. The company’s reputation suffered and the first of many protests began to take place.

By 1998, the company accepted it needed to take responsibility. Phil Knight admitted “the Nike product has become synonymous with slave wages, forced overtime and arbitrary abuse.” It was going to be a longer journey than they might have imagined. Nike and child labour had become indelibly linked in the public consciousness.

Nike began to take the first steps. It released the names and locations of its factories. It changed elements of its shoe manufacture to reduce hazards to the workers who make them. It began producing reports to talk about its progress. And it put more focus on audits of factories to identify problems.

Nike now has extensive and transparent reporting on its progress. Still, the popular view of the company as a villain refused to go away. In 2001, one particular incident summed up the problem. The company had offered customers the ability to have a word of their choice stitched onto their new Nike trainers. One enterprising critic requested that the word ‘sweatshop’ should be used for his shoes. The company’s refusal was one of the first examples of a viral internet phenomenon as the email exchange got shared widely across the world.

Organisations such as ‘NikeWatch’ and the Clean Clothes Campaign expressed skepticism about Nike’s efforts, taking a cynical view of its seriousness and sincerity.

But by 2005, the company’s steady progress began to gain grudging respect from some of the campaign groups, and it seemed like the mood music might begin to change. Then just at that point, there came a crisis that threatened to take it right back to the beginning.

In the run-up to the 2006 World Cup, photos were presented to the company of pictures of Pakistani children stitching Nike footballs – a direct repeat of what had happened ten years earlier. It turned out that the supplier, Saga Sports, having become overwhelmed with orders linked to the approaching World Cup, had gone against the rules by sending balls out to be made at local homes.

There was a significant cost to dealing with this problem. To recall the balls would cost $100m short term, and it would delay future production considerably. The company decided to pull the product anyway and to cancel its contract with Saga, moving instead to Silver Star where all work would be done on factory premises.

It was a short-term financial blow, but it sent a strong signal to the company’s suppliers and its customers at the same time, that it was serious about tackling the problem. The impact on former supplier Saga was enormous, essentially driving it to bankruptcy. Other suppliers based in Sialkot, Pakistan took careful note.

Hannah Jones, Nike’s VP of Sustainable Business, has been a key figure driving the company’s progress

Nike has shown itself to be willing to take other tough decisions, for instance pulling support from a major low cost supplier in Bangladesh because it was impossible to provide working conditions that met decent standards. This was a move that gave it a competitive disadvantage when others were exploiting Bangladesh as the lowest possible cost base. But it left the company less exposed when the Rana Plaza building disaster took place and hard questions began to be asked about who was doing what.

Now, Nike finds itself more often at the top of lists for sustainable companies, particularly within its sector. It appears in the top ten of the Fortune Most Admired Companies list. Its commitment to improving its environmental impact, providing transparency about its processes, and ensuring decent working conditions in its supply chain, have turned the tide of public perception.

Now the company is more often to be found on the front foot when it comes to matters of integrity. For instance, when boxer Manny Pacquiao recently made anti-gay comments during a media interview, Nike dissolved its partnership with him the very next day, labelling his comments “abhorrent.”

The company’s turnaround has become one of the success stories of corporate integrity in the last two decades.

- Harvard Business School →

- Faculty & Research →

- January 2000 (Revised September 2002)

- HBS Case Collection

Hitting the Wall: Nike and International Labor Practices

- Format: Print

- | Language: English

- | Pages: 23

About The Author

Debora L. Spar

Related work.

- Faculty Research

- Hitting the Wall: Nike and International Labor Practices By: Debora L. Spar and Jennifer Burns

- My Program Request

- +32(0)2.206.10.82

- [email protected]

Nike: From Child Labor To Social Responsible Lean Innovation

March 21, 2017

From poster child for lack of responsibility to catalyst of positive change

In the 1990s, Nike, one of the premiere shoe manufacturers in the world, worn by the greatest names in sports from Michael Jordan to Tiger Woods or Maria Sharapova, became a poster child for lack of corporate responsibility. The Nike product has become a synonym for slave wages, forced overtime, arbitrary abuse and was facing weak demand and unrelenting criticism. In the beginning, the brand denied responsibility for any malpractice that might have taken place in its contract factories. However, at the end of the 1990s, the global boycott campaign of Nike was so impactful that the “swoosh” brand didn’t have any other choice than to recognize doubtful child labour issues and offered to visit the contract factories in Southeast Asia.

To achieve this, it developed a partnership with the International Youth Foundation in order to conduct an anonymous survey among the 67,000 female workers in Nike contract factories. The relationship with the International Youth Foundation was very helpful. As a result, Nike benefited from a huge body of data and was able to identify a number of ways in which the working conditions at the factories could be improved. Amongst concerns, the pain points were delivery time, product quality, working conditions, and manager-worker relationships. Nike began to secure commitments from longstanding suppliers to implement a Lean innovation-based transformation .

At Nike, people are the ultimate value stream

The term “Lean” was first coined to describe The Toyota Way management system, which is built on two pillars: Respect for People and Continuous Improvement . Based on this, NIKE’s culture of empowerment model is three-pronged: attract, develop, and empower. Most importantly, the people of NIKE, Inc. are seen as its ultimate value stream. By implementing a culture of empowerment that employs continuous improvement (CI) to deliver high-quality products, on time, at a low cost, Nike could incentivize its contract factories to improve the working conditions, reduce waste and inefficiencies, and safeguard employee satisfaction.

Nike further developed a partnership with the Fair Labor Association to create performance indicators and launched the Sustainable Apparel Coalition with the US Environmental Protection Agency and other manufacturers. No other capacity-building program in the textile industry integrates as such HR and support of lean manufacturing, addressing both the needs of factories and workers, as well as the business. The transformation to Lean innovation and manufacturing was a huge commitment for the contract factories and resulted in a new standard of factory self-governance .

How to measure the environmental and social footprint of a complex supply chain?

From an environmental stance also, Nike determined that their finished goods manufacturing was where they had the largest impact on both people and the environment. Just consider these numbers:

- Nike has manufacturing contracts with over 785 factories, across India, Vietnam, Philippines, and South America

- NIKE, Inc. has more than 1 million workers around the world

- 500,000 different products

- More than 500,000 unique products

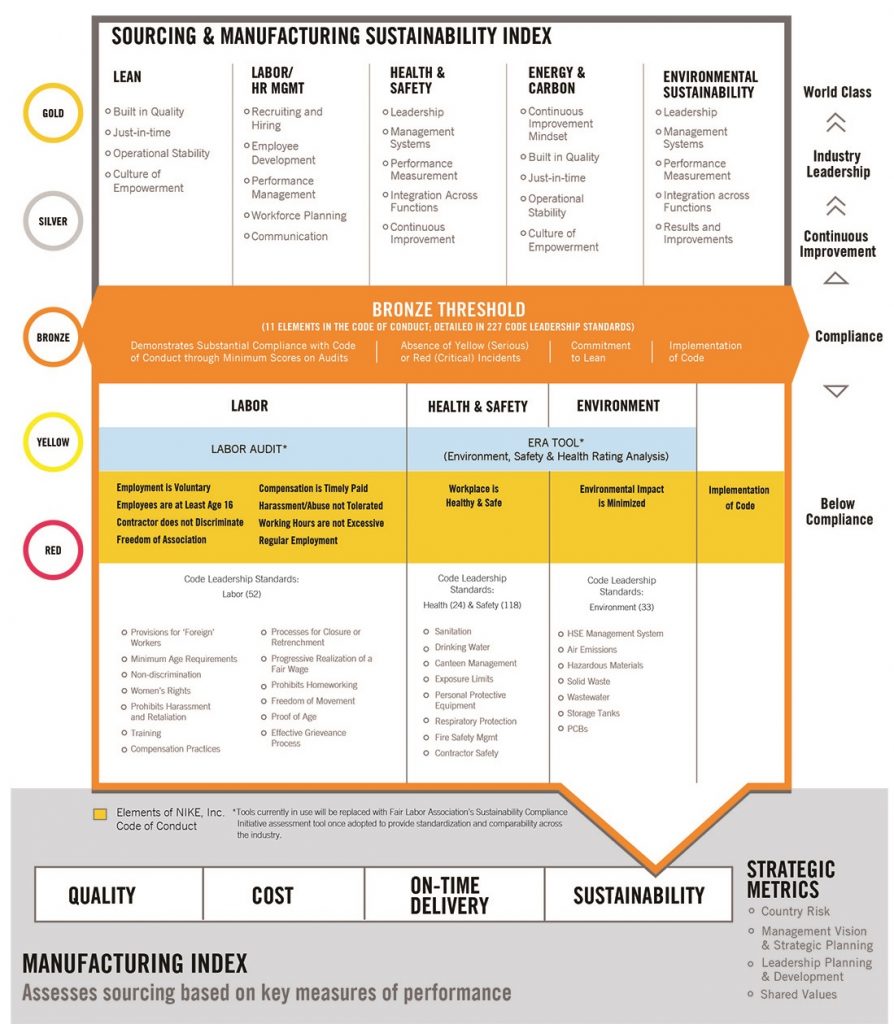

To ensure everyone is performing at NIKE ‘s standards, the company developed a scoring system for their contract factories ranking them from gold to silver, bronze, yellow or red levels . The Manufacturing Index (MI) in use assesses each factory in terms of lean, labour, health and safety, energy and carbon, and sustainability. This system gives environmental and human resource management performance equal weight alongside business metrics.

Nike’s goal is to bring all factories to a bronze rating – their lowest acceptable level – or above. A bronze rating reflects factory compliance with Nike’s Code of Conduct and Code Leadership Standards, which are designed to protect the rights of workers and create a safe working environment. Any factory that reaches silver or gold demonstrates an additional commitment to progressively embed Lean innovation and performance management systems.

[Source: shmula.com]

Nike : the new world leader in Lean innovation?

Nike aimed at creating an optimized production process that reduces impacts, eliminates waste, enables skilled and engaged workers to drive quality and productivity, and that is strategically led by managers who see value in an empowered workforce. In targeting these high requirements, Nike doesn’t leave the partner hanging dry. It actually spends time, energy and resources helping the contract manufacturing partner raise the bar in all areas of their manufacturing and reach new standards through various incentives. For example, the brand requires partners below the bronze level to pay for 3rd party audits, while partners above the bronze level are rewarded with audits paid by NIKE. So far, factories are making progress in meeting compliance with the new supplier standards and 86% of contract factories rated bronze or better at the end of 2015 :

- 0 manufacturer in Gold

- 1 manufacturer in Silver

- 535 in Bronze

- 156 in Yellow

On top of this, just two years after certifying their first Lean manufacturing line, the factories improved their score by more than a half grade on their audits compared to those who had yet to adopt a Lean line. This accounted for a 15% reduction in noncompliance with labour standards such as wages, benefits, and time off.

Circular economy according to Nike

As part of its efforts to promote Lean sustainability and disruptive innovation, Nike is fully behind the so-called “circular economy” concept, which focuses on re-use and sustainability management across the full product lifecycle . Nike envisions a transition from linear to circular business models and a world that demands closed-loop products, designed with better materials, made with fewer resources and assembled to allow easy reuse in new products.

This involves up-front product design, with materials reclaimed throughout the manufacturing process and at the end of a product’s life. Nike is re-imagining waste streams as value streams, and already its designers have access to a palette of more than 29 high-performance materials made from its manufacturing waste . Already, materials left over from producing Nike shoes are being reborn as tennis courts, athletic tracks and new shoes.

With its strategy based on 2 principles, “Make Today Better” and “Design the Future”, Nike sets the following goals for sustainability improvement by 2020:

- To source 100% of products from contract factories meeting the company’s definition of sustainable.

- To have zero waste from contracted footwear manufacturer sent to landfill or incineration without energy recovery.

- To create products that deliver maximum performance with minimum environmental impact, seeking a 10% reduction in the average environmental footprint and an increased use of more sustainable materials overall.

- To reach 100% renewable energy in owned or operated facilities by the end of 2025.

It is not enough to adapt to what the future may bring. We are creating the future we want to see through sustainable innovation. Mark Park, CEO of Nike CEO

Sustainability: the new Lean 2.0?

Through being creative and strategic in developing Lean innovation and transformation techniques, Nike pursued systemic change to improve corporate social responsibility and the results speak for themselves. In less than a decade, the brand went from being the primary target of an anti-sweatshop campaign to becoming an industry leader in sustainability and corporate social responsibility. Nike did not only make use of traditions, such as the culture of empowerment model, but also revolutionized how it interacts with their global partners to become today’s one of the most Lean manufacturers in the world. As for the previsions for 2017 and beyond, there is no doubt that sustainability will become the new Lean.

Get The Latest Update