What Is Hedging in Academic Writing?

In academic writing, precision and clarity in language is important. Ensuring a nuanced balance between certainty and caution can only be achieved by the strategic use of language; also called as hedging.

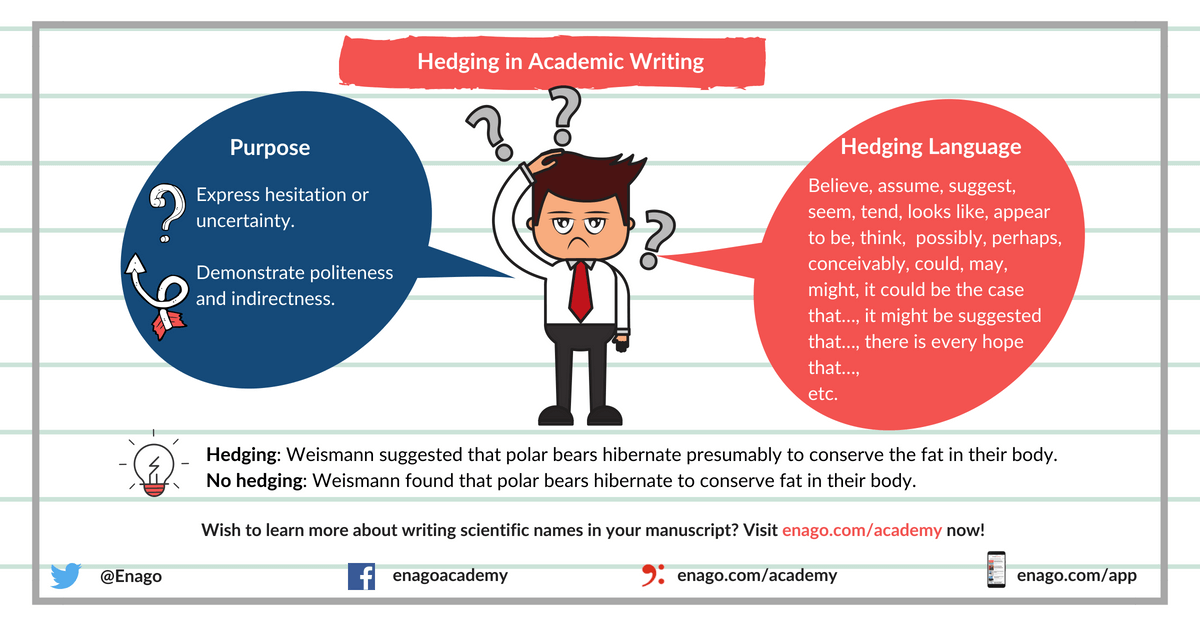

What is Hedging

Hedging is the use of linguistic devices to express hesitation or uncertainty as well as to demonstrate politeness and indirectness. It holds significance in academic writing because it is prudent to be cautious in one’s statements so as to distinguish between facts and claims.

What is the Use of Hedging

People use hedged language for several different purposes but perhaps the most fundamental are the following:

- To minimize the possibility of another academic opposing the claims that are being made

- To conform to the currently accepted style of academic writing

- To enable the author to devise a politeness strategy where they are able to acknowledge that there may be flaws in their claims

Types of Hedging

Following are a few hedging words and phrases that can be used to achieve this.

- Introductory verbs – seem, tend, look like, appear to be, think, believe, doubt, be sure, indicate, suggest

- Certain lexical verbs – believe, assume, suggest

- Modal Adverbs – possibly, perhaps, conceivably

- That clauses – It could be the case that…, it might be suggested that…, there is every hope that…

Here are some examples to understand the purpose of hedging.

Consider the following hedging language examples:

- It may be said that the commitment to some of the social and economic concepts was less strong than it is now.

- The lives they chose may seem overly ascetic and self-denying to most women today.

In the first statement, the commitment to some of the social and economic concepts was less strong than it is now while in the second one, the lives they chose seem overly ascetic and self-denying to most women today.

A crucial advantage in academia is that studies are often interpreted from multiple perspectives. This inherent openness leaves room for improvement and development in most fields of study.

Think you know what is hedging in academic writing and how to use it? Share your knowledge in the form of blog posts or opinion pieces at Enago Academy’s Open Platform .

thank you !

great and things are clear and direct no complications, plus very helpeful.

very informative

This appears to be insightful and educative.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Language & Grammar

- Reporting Research

How to Avoid Run-on Sentences in Academic Writing

When writing a paper, are you more focused on ideas or writing style? For most…

How to Improve Your Academic Writing Using Language Corpora

No matter how brilliant a researcher you are, you must be able to write about…

- Global Spanish Webinars

- Old Webinars

Cómo Dominar el Arte de Escribir Manuscritos en Inglés

Consejos de corrección Errores comunes de manuscritos Aplicación de la gramática inglesa Consejos sobre redacción…

- Global Japanese Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

英語での論文執筆をマスターする

英語でのライティングスキルの重要性 論文英語の組み立て 日本人によくある英語の間違い 論文執筆の基本

- Infographic

Top 10 Tips to Increase Academic Vocabulary for Researchers

Improving academic vocabulary is an important skill for all researchers. Academic vocabulary refers to the words…

Avoid These Common Grammatical Errors in Your Paper

How Coherence in Writing Facilitates Manuscript Acceptance

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- Industry News

- Publishing Research

- AI in Academia

- Promoting Research

- Career Corner

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Peer-Review Week 2023

- Open Access Week 2023

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

In your opinion, what is the most effective way to improve integrity in the peer review process?

- I nfographics

- Show AWL words

- Subscribe to newsletter

- What is academic writing?

- Academic Style

- What is the writing process?

- Understanding the title

- Brainstorming

- Researching

- First draft

- Proofreading

- Report writing

- Compare & contrast

- Cause & effect

- Problem-solution

- Classification

- Essay structure

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Book review

- Research proposal

- Thesis/dissertation

- What is cohesion?

- Cohesion vs coherence

- Transition signals

- What are references?

- In-text citations

- Reference sections

- Reporting verbs

- Band descriptors

Show AWL words on this page.

Levels 1-5: grey Levels 6-10: orange

Show sorted lists of these words.

| --> |

Any words you don't know? Look them up in the website's built-in dictionary .

|

|

Choose a dictionary . Wordnet OPTED both

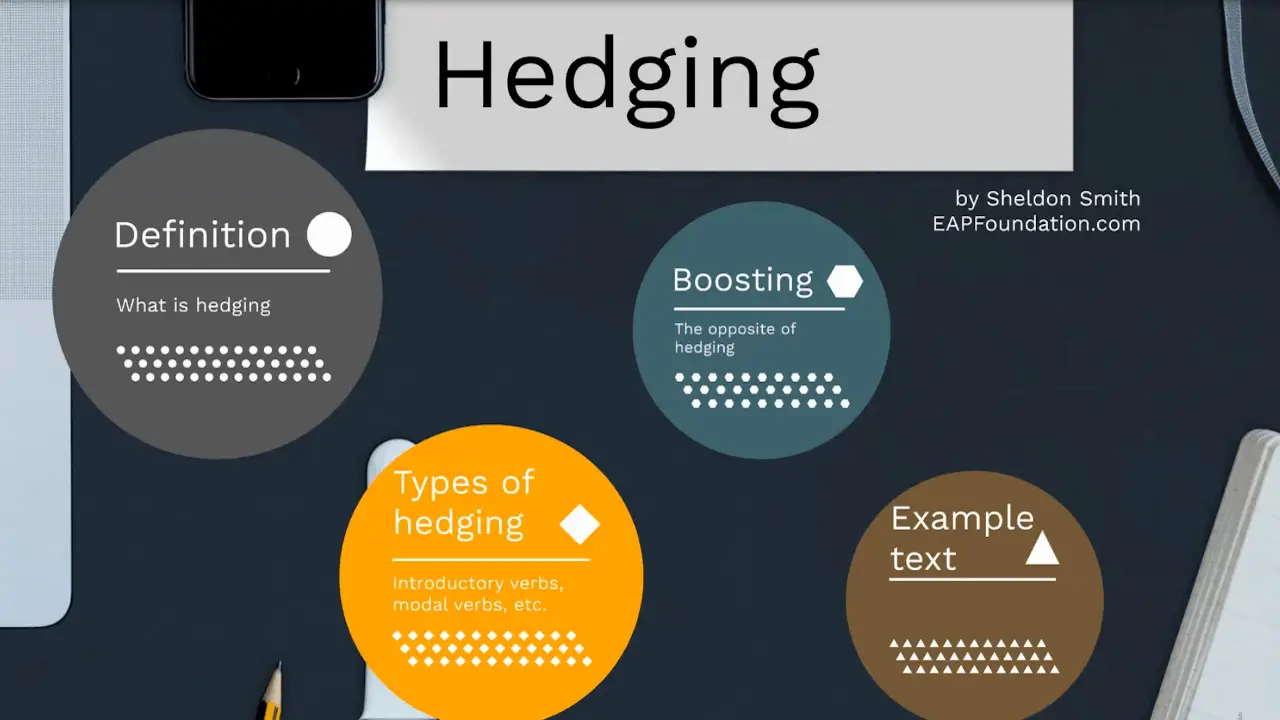

Hedging Using cautious language

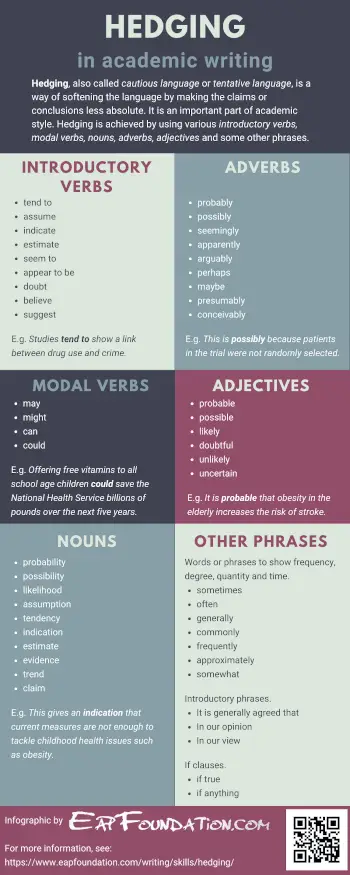

Hedging, or 'being cautious', is an important component of academic style . This section explains what hedging is , then looks at different ways to hedge, namely using introductory verbs , modal verbs , adverbs , adjectives , nouns , and some other ways such as adverbs of frequency and introductory phrases. There is as an example passage so you can see each type of hedging in an authentic text, and, at the end, a checklist so you can check your understanding.

What is hedging?

For another look at the same content, check out YouTube or Youku , or the infographic .

Hedging, also called caution or cautious language or tentative language or vague language , is a way of softening the language by making the claims or conclusions less absolute. It is especially common in the sciences, for example when giving a hypothesis or presenting results, though it is also used in other disciplines to avoid presenting conclusions or ideas as facts, and to distance the writer from the claims being made.

The following is a short extract from an authentic academic text, with the hedging in blue (the full article is available here: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5855 ).

Although duration of smoking is also important when considering risk, it is highly correlated with age, which itself is a risk factor, so separating their effects can be difficult; however, large studies tend to show a relation between duration and risk. Because light smoking seems to have dramatic effects on cardiovascular disease, shorter duration might also be associated with a higher than expected risk.

Hedges can be contrasted with boosters (such as 'will' or 'definitely' or 'always'), which allow writers to express their certainty. These are less commonly used in academic writing, though tend to be overused by learners of academic English in place of more cautious language.

Introductory verbs

Check out the hedging infographic »

There are various introductory verbs which allow the writer to express caution rather than certainty in their writing. The following is a list of some of the most common ones. Some of these are linked to cautious nouns , adverbs or adjectives , in which case these are also given.

- tend to ➞ tendency (n)

- assume ➞ assumption (n)

- indicate ➞ indication (n)

- estimate ➞ estimate (n)

- seem to ➞ seemingly (adv)

- appear to be ➞ apparently (adv)

- doubt ➞ doubtful (adj)

Modal verbs

Another way of being cautious is to use the modal verbs expressing uncertainty, in place of stronger, more certain modals such as will or would . The following are modals which express uncertainty.

There are many adverbs which can be used to express caution. Some of these are associated with cautious adjectives or nouns , in which case these are also given. The adverbs can be divided into two types: modal adverbs, which are related to the possibility of something happening, and adverbs of frequency, which give information on how often something happens.

- probably ➞ probable (adj), probability (n)

- possibly ➞ possible (adj), possibility (n)

- seemingly ➞ seem to (v)

- apparently ➞ appear to be (v)

- conceivably

The following adjectives can be used to express caution. Again, some of these are associated with other word forms, in which case these are also given.

- probable ➞ probably (adv), probability (n)

- possible ➞ possibly (adv), possibility (n)

- likely ➞ likelihood (n)

- doubtful ➞ doubt (v)

The following nouns can be used to express caution. Some of these are associated with other word forms, in which case these are also given.

- probability ➞ probably (adv), probable (adj)

- possibility ➞ possibly (adv), possible (adj)

- likelihood ➞ likely (adj)

- assumption ➞ assume (v)

- tendency ➞ tend to (v)

- indication ➞ indicate (v)

- estimate ➞ estimate (v)

Other phrases

There are three other ways to express caution. The first is to use words or phrases to show frequency, degree, quantity and time.

- occasionally

- approximately

The second way is to use introductory phrases, such as the following.

- It is generally agreed that

- In our opinion

- In our view

- It is our view that

- We feel that

- We believe that

- I believe that

- To our knowledge

- One would expect that

The final way is to use if clauses.

- if anything

Example passage

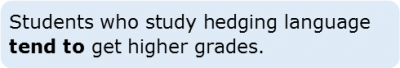

Below is an example passage. It is taken from the Limitations section of an article in the BMJ (formerly British Medical Journal). It is used to give examples of different types of hedging in an authentic academic text (use the buttons to highlight different types of hedging). The full article, published on 17 July 2019, is available here: https://www.bmj.com/content/366/bmj.l4786 .

This study has a few limitations. Firstly, we excluded 25% of the households from analysis because of missing information on either income or BMI. It is unlikely that such missing information is related to price elasticity or purchase behaviour [...] however, it may have resulted in some bias for the pooled values across groups. [...] Secondly, the baseline daily energy purchase estimates are sample average estimates that do not consider age or sex of the household members who could have different energy requirements. [...] Thirdly, we used a static model for weight loss based on changes in energy consumption, which might not fully reflect actual mechanisms of weight change. [...] Fourthly, the study does not reflect on the substitution of nutrients alongside changes in energy. For example, reduction in energy from high sugar snacks could lead to substitution of other foods that are lower in energy content but perhaps higher in other nutrients of concern, such as saturated fats or salt. The health impacts of such substitutes should be further analysed and considered in the decision making process around food price policies. Furthermore, the satiety index of sugary snacks can vary greatly: some high sugar snacks could reduce overeating at meals, hence the overall impact of reduced consumption of high sugar snacks would be partly cancelled out by consumption of larger portions during mealtimes. Studies of sugary drinks only would be prone to this phenomenon, as the satiety effect of sugar sweetened beverages is generally low. 50 Fifthly, we assumed that all food purchased was consumed, which is unlikely , and some food will inevitably be waste. However, although the link between purchasing and consumption is far from perfect, it is strong (eg, 51 ), and our estimates on the effect of price rises on change in energy purchased is likely to be similar to that on consumption even if absolute values differ.

Bailey, S. (2000). Academic Writing. Abingdon: RoutledgeFalmer

Hyland, K. (2006) English for Academic Purposes: An advanced resource book . Abingdon: Routledge.

Hyland, K. (2009) Academic Discourse: English in a Global Context . London: Continuum.

Jordan, R.R. (1997) English for Academic Purposes: A guide and resource book for teachers . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

GET FREE EBOOK

Like the website? Try the books. Enter your email to receive a free sample from Academic Writing Genres .

Below is a checklist. Use it to check your understanding.

| I know . | ||

| I know different which can be used for hedging (e.g. ). | ||

| I know how can be used for hedging. | ||

| I know some which can be used for hedging (e.g. ). | ||

| I know some which can be used for hedging (e.g. ). | ||

| I know some which can be used for hedging (e.g. ). | ||

| I am aware of , i.e. phrases to show frequency, degree, quantity and time (e.g. ), introductory phrases (e.g. ), and if clauses ( ). |

Next section

Read more about describing data in the next section.

Previous section

Go back to the previous section about transition signals .

- Transitions

Author: Sheldon Smith ‖ Last modified: 03 February 2022.

Sheldon Smith is the founder and editor of EAPFoundation.com. He has been teaching English for Academic Purposes since 2004. Find out more about him in the about section and connect with him on Twitter , Facebook and LinkedIn .

Compare & contrast essays examine the similarities of two or more objects, and the differences.

Cause & effect essays consider the reasons (or causes) for something, then discuss the results (or effects).

Discussion essays require you to examine both sides of a situation and to conclude by saying which side you favour.

Problem-solution essays are a sub-type of SPSE essays (Situation, Problem, Solution, Evaluation).

Transition signals are useful in achieving good cohesion and coherence in your writing.

Reporting verbs are used to link your in-text citations to the information cited.

What is hedging language and why is it important?

This is the first of three chapters about Hedging Language . To complete this reader, read each chapter carefully and then unlock and complete our materials to check your understanding.

– Introduce the overall concept of hedging language in academia

– Provide examples of hedging language to guide the learner

– Discuss the importance of including hedging language

Chapter 1: What is hedging language and why is it important?

Chapter 2: What are the different types of hedging language?

Chapter 3: Which academic hedging language is most useful?

Before you begin reading...

- video and audio texts

- knowledge checks and quizzes

- skills practices, tasks and assignments

During your time as an academic, you’re likely to encounter the concept of hedging language , as this type of language is very common in both academic writing and speech. Anyone that wishes to succeed in publishing or completing a bachelor’s or master’s degree will have to become quickly familiar with what this language is, what it looks like, and why it’s used. This chapter therefore covers those topics precisely, with Chapters 2 and 3 discussing the many different types of hedging language that can be used in academic assignments .

What is hedging language?

In an academic context, such as when writing an essay , participating in a group discussion , or conducting a presentation , the writer or speaker of those assignments will be required to provide ideas, opinions, facts, arguments and evidence to support their research – as would the author of an academic textbook or journal article. To do this, every writer or speaker should be able to inform the audience of the certainty of their claims. While facts may be said with confidence, claims (opinions or arguments) which may be proven wrong by others, should be delivered in a more cautious manner, such as in the examples below:

Do you notice the difference between the fact and the claim in the above? The fact ‘humans live on Earth’ cannot be proven wrong and so does not require hedging language , while the claim ‘humans will likely destroy the planet’ could (in the distant future) be disproven. It is the hedging adjective ‘likely’ in this claim that provides caution, protecting the speaker or writer from being wrong. Hedging language, therefore, offers a type of modality that allows the speaker or writer to indicate their degree of confidence or certainty when delivering an idea or claim.

However, although the previous claim that ‘humans will likely destroy the planet’ uses some hedging language , this claim still isn’t easy to disprove because there’s no time limitation to that statement. Because we don’t know when humans may or may not destroy the planet, the writer or speaker may sound fairly confident when claiming this (using ‘likely’) without fear of being easily disproven. But is this true for the following two claims?

Which claim do you think is more certain, and which claim could be more easily disproven? A or B? Clearly, in claim A, the hedging adverb ‘probably’ indicates some degree caution, but this is not as cautious as the hedging phrase ‘it is possible that’ in sentence B. And is this any surprise? While claim B could be disproven today, it would take 150 years to disprove the speaker in A (which is beyond anyone’s lifetime). Clearly then, different hedging words and phrases like ‘probably’ or ‘it is possible that’ may be used to demonstrate varying degrees of caution and certainty.

Why is hedging language important?

As well as allowing a speaker or writer to provide softer and more cautious statements and claims, hedging language allows for the delivery of politeness strategies and for that speaker or writer to be indirect about the information they provide. But why would it be necessary to do this in an academic context? There are four primary reasons that an academic would choose to use hedging language:

1. To conform to academic standards of speech and writing.

2. To reduce the possibility of being proven wrong by other researchers, peers, or academics (such as your tutor). Remember that one of the primary purposes of academic research is to prove or disprove previously existing research.

3. To demonstrate accuracy and critical thinking when reporting research, showing that a study’s methodology may not be 100% accurate or its results completely trustworthy.

4. To use politeness strategies to concede to the reader or listener that there may be flaws in the information being provided.

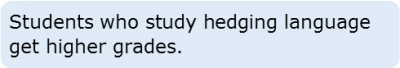

Before moving on to Chapter 2 in which the different types of hedging language are discussed, let’s look at one more example:

Does this sentence have any hedging language , and is its claim true? By adding hedging language, we can make this claim more accurate and cautious by highlighting to the reader that it isn’t always the case that students get higher grades. Instead, we can show that there’s merely a tendency for this to be true:

To reference this reader:

Academic Marker (2022) Hedging Language. Available at: https://academicmarker.com/academic-guidance/vocabulary/hedging-language/ (Accessed: Date Month Year).

- University of Bristol

- UCL Writing Centre

Downloadables

Once you’ve completed all three chapters about hedging language , you might also wish to download our beginner, intermediate and advanced worksheets to test your progress or print for your students. These professional PDF worksheets can be easily accessed for only a few Academic Marks .

Our hedging language academic reader (including all three chapters about this topic) can be accessed here at the click of a button.

Gain unlimited access to our hedging language beginner worksheet, with activities and answer keys designed to check a basic understanding of this reader’s chapters.

To check a confident understanding of this reader’s chapters , click on the button below to download our hedging language intermediate worksheet with activities and answer keys.

Our hedging language advanced worksheet with activities and answer keys has been created to check a sophisticated understanding of this reader’s chapters .

To save yourself 5 Marks , click on the button below to gain unlimited access to all of our hedging language chapters and worksheets. The All-in-1 Pack includes every chapter in this reader, as well as our beginner, intermediate and advanced worksheets in one handy PDF.

Click on the button below to gain unlimited access to our hedging language teacher’s PowerPoint, which should include everything you’d need to successfully introduce this topic.

Collect Academic Marks

- 100 Marks for joining

- 25 Marks for daily e-learning

- 100-200 for feedback/testimonials

- 100-500 for referring your colleages/friends

What is Hedging in Academic Writing?

In academic writing, researchers and scholars need to consider the tonality and sweep of their statements and claims. They need to ask themselves if they are being too aggressive in trying to prove a point or too weak. If you’ve ever struggled to ensure your academic writing sounds confident yet acknowledges the inherent complexities of research, Hedging is a technique that can help you achieve just that.

Hedging is a linguistic strategy that helps soften the claims and express the degree of uncertainty or certainty that an author wants to convey based on their research and available evidence. In this blog post, we’ll explore what hedging is and why it’s important in academic writing. We’ll also provide practical tips on how to use hedging effectively, including avoiding common mistakes and recognizing the role of context.

Table of Contents

- What is the importance of hedging in academic writing?

- How to use hedging in academic writing?

- Understand context and appropriate usage

- Use precise and accurate language

- Provide supporting evidence and justification

- Seek feedback and peer review

What is the importance of hedging in academic writing?

The element or degree of uncertainty in academic knowledge and science cannot be overlooked. Hence, making absolute claims in educational and research writing can run counter to the traditional understandings of science as tentative. By employing hedging, academic writers and researchers acknowledge the possibilities for alternative perspectives and interpretations. In doing so, researchers and scholars accept the fact that their statements are open to discussions and debates. Hedging also lends credibility to their claims.

Consider the following statements:

‘Eating more than four eggs a day causes heart disease’ or

‘People who rise early remain alert throughout the day.’

These statements sow seeds of doubt or lead to many questions among readers. However, they can be made more flexible and open to discussion by adding words like ‘probably’ and ‘could.’

Let’s review the modified sentences again:

‘Eating more than four eggs a day could cause heart disease’ or

‘People who rise early probably remain alert throughout the day.’ 1

How to use hedging in academic writing?

While hedging in academic writing is inevitable, it should not be overused. Researchers must know how to hedge and develop this skill to deliver credible research. The writer can utilize specific hedging devices to make a well-reasoned statement.

These include the use of grammatical tools like:

- Verbs such as suggest, tend to seem to indicate. For example, ‘Earlier studies indicate…’

- Modal auxiliaries such as may, might, can, and could. For example, ‘Industries can make use of …’

- Adjectives such as much, many, some, perhaps. For example, ‘within some micro-credit groups.’

- Adverbs such as probably, likely, often, seldom, sometimes.

- ‘That’ clauses: for example, ‘It is evident that…’

- Distance – it is helpful to distance oneself from the claims made. For example, you present it in the following ways: ‘Based on the preliminary study…’, ‘On the limited data available…’.

A combination of such devices may be used to balance the strength of your claims. For example, in double hedging, the statement can be: ‘It seems almost certain that…’.

However, overuse of hedging can dilute the impact of your arguments. Ideally, hedging should enhance clarity and foster a space for discussion, not create unnecessary ambiguity.

Edgar Allan Poe, the renowned American writer, encapsulated the essence of doubt with his insightful words: ‘The believer is happy, the doubter is wise.’ This sentiment aptly captures the advantages of employing hedging in academic writing. While robust evidence and data may be the basis of an argument, the practice of hedging ensures that ideas are presented not as overconfident assertions but as credible and considerate viewpoints. Through cautious language, academic writers create an atmosphere of respect and openness. This approach not only acknowledges varied perspectives but also signals to readers that the author is receptive to counterthoughts and alternative viewpoints. It promotes a more prosperous and more inclusive scholarly discourse. Here are some tips for the effective use of hedging in academic writing.

Tips to leverage hedging in academic writing

Hedging in academic writing isn’t just about softening claims; it’s about strategically conveying the strength of your evidence and fostering a nuanced discussion. Here are some key tips to help you leverage hedging effectively:

Understand context and appropriate usage

Employing hedging solely for the sake of it can disrupt the flow and result in counterproductive outcomes, potentially inviting unnecessary critique and doubts regarding the credibility of the work. 2 The very purpose of hedging is to balance the tone of your claims such that it does not appear overconfident or too weak, so you need to be conscious of the context and hedge appropriately. So, how do you use a cautious tone through hedging? To express a balanced tone in the claims, you need to use a mix of hedging devices to convey low to high certainty about your claims. For example, for low certainty, words used can be ‘may, could, might’; for medium certainty, words such as ‘likely, appears to, generally’; and high certainty words such as ‘must, should, undoubtedly.’ It all depends on the evidence you have at hand.

Use precise and accurate language

The use of precise and accurate language is critical, particularly the use of the right strength of the hedging device based on the evidence you have. Be careful that the claims are not presented as too weak such that they defeat your main argument and idea. It is important to remember that hedging requires refined linguistic skills. For instance, when employing hedging words such as ‘possibly’ and ‘probably,’ it is crucial to understand their subtle distinctions. ‘Possibly’ should be reserved for situations where an outcome is within the realm of feasibility – ‘The weather data shows that it will likely rain tomorrow.’ On the other hand, ‘probably’ indicates a higher likelihood, albeit without absolute certainty – ‘The latest weather data shows it will probably rain next week.’

Provide supporting evidence and justification

When you provide supporting evidence and justification, you will be able to express the degree of certainty more clearly and also recognize what is less specific. Be careful not to generalize or make categorical statements without any supporting evidence. Neglecting the responsibility to substantiate statements with information dilutes their impact. Embracing data not only imparts accuracy and precision to claims but also bolsters their credibility. Further, the use of hedging in academic writing helps communicate the claim clearly based on evidence at the time of doing research and writing. It acknowledges that situations can change, and discoveries may be made at a later date.

Seek feedback and peer review

It is always recommended to have your work read thoroughly by a third person or a colleague/faculty member. Outside feedback and a peer review process can highlight specific areas in your work that may require a certain degree of improvement or refinement. By actively seeking feedback, a distinct message is conveyed – the willingness to expose ideas to the crucible of critical assessment. This proactive approach not only signals a receptivity to constructive insights but also exemplifies scholarly integrity that places value on the collective pursuit of knowledge. In embracing this feedback loop, the practice of hedging not only upholds the ethos of academic rigour but also creates an ecosystem of continuous improvement and growth.

Hedging is a linguistic tool that reflects a willingness to embrace diverse perspectives in the pursuit of knowledge. As academicians navigate their respective fields, hedging emerges as an ally, facilitating a nuanced discourse that pushes the boundaries of scholarship forward.

References:

- IELTS Task 2 essays: formal writing (hedging) – https://ieltsetc.com/2020/12/hedging-in-academic-writing/

- Hedging in academic writing: Some theoretical problems, Peter Crompton (1997) – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S088949069700007

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- How to Paraphrase Research Papers Effectively

- How to Cite Social Media Sources in Academic Writing?

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- Do Plagiarism Checkers Detect AI Content?

How to Use AI to Enhance Your College Essays and Thesis

Paperpal’s new ai research finder empowers authors to research, write, cite, all in one place, you may also like, how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), maintaining academic integrity with paperpal’s generative ai writing..., research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write an abstract in research papers..., how to write dissertation acknowledgements, how to structure an essay.

Hedging language refers to how a writer expresses certainty or uncertainty. Often in academic writing, a writer may not be sure of the claims that are being made in their subject area, or perhaps the ideas are good but the evidence is not very strong. It is common, therefore, to use language of caution or uncertainty (known as hedging language).

Hedging verbs

The verbs appear and seem may be used to express uncertainty. Appear and seem can be used with existential clauses (the verb to be ) to indicate caution.

- There appears to be a correlation between social class and likelihood of getting to university,

- It seems to be the case that non-native speakers of English rely more on the mother tongue.

The verbs appear and seem may also be followed by the subordinating conjunction

- It appears as if/though they had been working together

- It seems as if/though expeditions to Mars will be possible in the future.

Appear and seem can also be used with that + clause

- It seems that the scope of the native speaker in Korea is narrow and limited in the sense that the Americans are believed to be an absolute image of a native speaker.

A writer may also use reporting verbs to express uncertainty about a claim:

- Other studies suggest that using L1 supports the development of language acquisition.

- Larsen-Freeman and Long (1991) argue that input alone is not enough for language acquisition.

- Liu et al. (2004) claim that around a number of students are expected to drop out of their course early.

Modal Verbs

A writer can also hedge their claims by using modals of uncertainty (may/might, could, can) :

- Advocacy groups may ask an institution such as judges, politicians or scientists, to take on, highlight or, in the best case, show support towards their particular stance.

- A policy image might be fit into one venue better than another.

- In the 1950s, the American Government put forward a positive image of nuclear power as a new source of cheap and endless energy that could help reduce the dependence on imported oils.

- Policy actors can make use of scientific evidence to increase the legitimacy for their stance.

That Clauses

Writers may also express uncertainty using a number of that clauses. For example:

- It is clear that ...

- It is apparent that ...

- It may be perceived that ...

- It has been suggested/argued/claimed that ...

- It seems evident that ...

Adverbs may be used to express uncertainty. Note that these adverbs often go just before the main verb in a sentence. For example:

- All teachers were fully aware of the class being recorded, so they probably spoke more English than they usually would.

- She argues that strategies of expansion do not necessarily have to involve authoritative institutions only.

- There are always a number of issues which could potentially get onto the agenda.

A writer may also use a combination of structures:

- Research on the experiences of university students appears to indicate that social class is a determiner of participation in student societies.

- Early reports seem to suggest that a deal between the US and Iran may be signed before midnight.

- It appears that it may not be possible for all participants to be interviewed.

Rewrite the sentence using the prompts.

1. Students benefit most from relationships outside the classroom (John and Edwards, 2007)

John and Edwards (2007) JXUwMDM5JXUwMDEzJXUwMDE1JXUwMDEyJXUwMDEw JXUwMDJjJXUwMDFjJXUwMDA5JXUwMDE1 students benefit most from relationships outside the classroom.

2. Students live in student accommodation.

Students JXUwMDJjJXUwMDExJXUwMDBiJXUwMDBh JXUwMDJjJXUwMDFi live in student accommodation.

3. Listening skills improve through classroom activities and interaction outside the classroom.

It JXUwMDM5JXUwMDExJXUwMDAwJXUwMDE1JXUwMDA0JXUwMDEzJXUwMDAx JXUwMDM5JXUwMDEy if listening skills improve through classroom activities and interaction outside the classroom.

4. A lot of international students mix well with domestic students.

It JXUwMDMxJXUwMDFh JXUwMDNkJXUwMDEzJXUwMDFmJXUwMDBkJXUwMDAxJXUwMDBiJXUwMDFh JXUwMDJjJXUwMDFjJXUwMDA5JXUwMDE1 many international students mix well with domestic students.

5. Students don't need to translate words from Chinese to English.

necessarily

Students JXUwMDNjJXUwMDBi JXUwMDM2JXUwMDAxJXUwMDFi JXUwMDM2JXUwMDBiJXUwMDA2JXUwMDA2JXUwMDE2JXUwMDAwJXUwMDEyJXUwMDEzJXUwMDFiJXUw MDA1JXUwMDE1 need to translate words from Chinese into English.#

6. Regular IELTS practice has a positive effect on listening skills.

It may JXUwMDNhJXUwMDA3 JXUwMDI4JXUwMDE1JXUwMDE3JXUwMDExJXUwMDBhJXUwMDBjJXUwMDEzJXUwMDEzJXUwMDAx JXUwMDJjJXUwMDFjJXUwMDA5JXUwMDE1 regular IELTS practice has a positive effect on listening skills.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

IELTS with Fiona

Your comprehensive guide to IELTS

Full Members Academy Log in

IELTS Task 2 essays: formal writing (hedging)

By ieltsetc on December 17, 2020

Hedging is a really important feature of academic writing.

But what is hedging and how can you use it in your Task 2 essays?

This lesson teaches you 10 ways to 'hedge' and includes an interactive practise exercise.

Thank you for your interest in my IELTS lessons and tips.

Come and join the Bronze Membership to access this fabulous lesson and lots more.

Get access to all 175+ IELTS lessons for a month (cancel any time).

Learn more Login

Reader Interactions

October 11, 2022 at 10:24 pm

Impressive ideas. Thanks for this exceptional article. I will practice this from now on. Stay Blessed and Keep it up. 😀

November 16, 2022 at 9:05 am

Thanks Umair – same to you. Best wishes Fiona

October 2, 2021 at 3:42 am

I mean definition of hedging in academic writing

October 7, 2021 at 6:11 pm

Hi Chibuzor. The definition is explained in the article above. Best wishes Fiona

August 22, 2022 at 12:21 pm

August 18, 2021 at 2:52 pm

I am confused that if the hedging words will make our article less persuasive and make my stance less steady?

August 28, 2021 at 11:00 pm

Hi Eitan and thanks for your message. I understand why you might think this, but I hope you can see from the examples in the article, that hedging simply allows you to be more cautious with making claims that may be opinion or may not have any evidence to support them. Best wishes Fiona

July 13, 2021 at 4:15 pm

I am confused about a sentence given in this website. It would be great if you could just help me out with it.

Video games make (makes)people violent Just wanted to confirm which one is the right.

July 13, 2021 at 5:46 pm

Hi Alphonsa! Thank you so much – it was a typo! Please don’t hesitate to let me know if you find any typos. Sometimes I just don’t see them. All the best with your studies! Best wishes and thanks again, Fiona

August 9, 2022 at 8:45 am

Hello Alphonso right sentence is video games make people violent(Because here you use plural form and with plural form( video games) so plural verb should be in sentence). If I am wrong then please clarify

August 22, 2022 at 12:18 pm

Hi Alphonsa Yes, ‘video games’ is plural so I use the plural form ‘video games make people violent’, Best wishes Fiona

August 22, 2022 at 12:20 pm

- Translation

Hedging: Making claims of appropriate strength in Academic Writing

By charlesworth author services.

- 19 October, 2022

In academic writing, when you talk about the findings of your research, you should be careful and make claims of ‘appropriate strength’ . This language, which softens claims, is called hedging.

Purpose of hedging in academic writing

Textbooks tend to deal with facts. However, in an academic paper, you need to explain your findings and interpret them in light of the literature. A claim too strong could make others doubt or attack it. Meanwhile, a claim that is too weak is meaningless. This is because the size of the data source available to you and the limitations inherent in the scope of your study naturally impose restrictions on the nature and ambit of the claims that you can make. In academic writing, hedging is important for expressing the credibility of claims made based on the evidence presented. This article discusses effective hedging through examples from different sections of the paper. But before we dive in, a note…

Note : Naturally, there are differences across disciplines , with some harder sciences being able to make stronger claims as a result of their experiments, and the social sciences often being less able to make claims with certainty. Therefore, to showcase hedging better, this article uses examples from a social science paper (available here ).

Hedging in the Introduction section

Hedging can be used when reporting previous work (in the literature review part of the Introduction). In an extract from the paper used for this article, notice the highlights to understand how hedging has been used:

The concept of perceived threat occupies a key role in the study of authoritarianism (Cohrs et al., 2005a, 2005b; Doty et al., 1991; Kossowska et al., 2011; Rickert, 1998; Roccato et al., 2014). One of the central issues in the literature concerns what kinds of threats are involved in authoritarianism (Duckitt, 2013, p. 2). While several studies contend that threats to normative social order activate authoritarian pre-dispositions (Doty et al., 1991; Feldman, 2003; Feldman & Stenner, 1997; Rickert, 1998; Roccato et al., 2014), others suggest that perceived threats to personal health or well-being are more consequential (Asbrock & Fritsche, 2013; Hartman et al., 2021; Hetherington & Suhay, 2011; …

Hedging in the Results section

Hedging can also be used when reporting results. In other extracts from the same article, note the highlights for examples of hedging:

…There was some support for the conditional effect…

… but the conditional effects of primes were generally stronger for Republicans than for Democrats...

Hedging in the Discussion / Conclusion section

Hedging is particularly important when asserting what the results signify. Thus, it can be used in the Discussion or Conclusion section (or both, where the two sections are separate) when drawing the broader implications of your results.

Notice the use of hedging in the Discussion section from the same article:

In addition, no moderating effect of threat primes on anti-immigration attitudes in the AZ-FL-TX sample was observed. There is some evidence from previous studies showing that public opinion on immigration or refugees remained unchanged in the aftermath of some terror attacks, suggesting that there may be limits to the influence of traumatic events, especially concerning attitudes that are already relatively stabilized (Silva, 2018; Van Asscheh & Dierck, 2019). In addition, high salience of threats observed among respondents in the sample may also be the reason for the lack of empirical support for the moderating effect of threat on anti-immigration attitudes (but also see Hartman et al., 2021).

Hedging in the Conclusion section can be seen below:

The results contribute to the literature that underlines the importance of the authoritarian dynamic and threat perceptions in predicting support for extraordinary policies during the COVID-19 pandemic. They also present empirical evidence that both high and low authoritarians may be likely to support tough law and order policies and to some extent harsh punishments toward noncompliers depending on what types of threat are most salient to them.

Words and phrases to help you use hedging

As you can see, hedging typically employs certain words and phrases. Here is a list, though not exhaustive.

|

|

|

|

| chance, likelihood, possibility, probability : Is also often used with ‘strong, good, some, slight...’ · Usage: (There is a good) chance... |

|

| appear, seem, tend |

|

| likely, unlikely, probable, possible… |

|

| very, quite, rather, highly |

|

| usually, generally, as a rule, in the majority of cases |

|

| could, may, might, must |

|

| based on the (limited) data available, according to the interviewees, within this period |

|

| It is a fact (that)…, It is certain (that)…, It is definite (that)… |

|

| except for, with the exception of, apart from |

Hedging may be employed in different sections of an article. The main issue is how certain one can be of the claim being made. Try to strike a balance without making the claim too bold (especially if not strongly substantiated) or too unconvincing!

Share with your colleagues

Scientific Editing Services

Sign up – stay updated.

We use cookies to offer you a personalized experience. By continuing to use this website, you consent to the use of cookies in accordance with our Cookie Policy.

Curriculum and Student Achievement

Select Language

Author/Creation: Amy Hatmaker, January 2010. Summary: Introduces readers to hedging as a mechanism in academic writing to manage tone and attitude. Provides two techniques for writers to employ hedging. Learning Objectives: To define hedging. To identify reasons that writers can employ hedging techniques. To identify when a writers’ own work might need to use hedging. To hedge statements using the two techniques described.

Hedging is one mechanism that you can use to manage the tone, attitude, and information within your document. In academic writing, hedging involves using language that is tentative or qualifying in nature to enable you to maintain an attitude of objectivity; academic readers often associate objectivity (among other things, like quality research) with the writer’s credibility. Hedging is truly an art: the art of hedging comes in discerning when to use hedging or when to avoid using it. Using hedging inappropriately or too much might make your paper sound nebulous or ambiguous.

Hint: The more you read in your field, the better sense you’ll get of how to employ hedging in your writing.

This handout will help you understand hedging and its uses in academic writing as well as help you discern when it is necessary to hedge.

What are the reasons for hedging?

Research is a process in which you, as a writer, review the works of experts regarding your topic and then formulate your own argument in relation to the work of others. This can be done in two ways. You can present the expert’s argument in a manner that demonstrates its corroboration of your view. Or, you can dispute the expert’s findings, showing how the work does not hold up when viewed in connection with other studies in the field or perhaps discussing a flaw in the study that undermines the outcomes or results of the study.

When presenting your argument, you can use hedging for a variety of reasons.

Reasons Related to the Source

All writers, including you, have a position within an academic field. At the moment, you’re most likely a graduate student, entering your field and learning its discourse (through reading professional and academic journals and perhaps attending conferences hosted by leading organizations in your field).

As you write your academic papers, eventually working toward publication in your field, it is important for you to remember your position in relation to others in your academic field. Most individuals who are publishing in the field will be those who have doctorates and/or other advanced degrees. Some of these individuals will have considerable power in the field, will be recognized as authorities on sub-topics within the field, and so on. Again, reading in your field is important: the more you read in your field, the more you’ll know about who has power in your field.

Keeping this in mind, there are a couple of reasons why hedging should sometimes be used.

- To show a recognition of the power relationship. In other words, hedging shows that you recognize the status of the researcher by presenting your argument respectfully, modestly, and with courtesy, even if the researcher’s work corroborates your own.

- To show a recognition of the author’s status in their particular field. In other words, those who produce seminal studies on a subject would have more authority than a recently graduated Ph.D. would. Further, the producer of a seminal work will have several other scholars who will have referenced that work. A slight to the higher authority could be seen as a slight to the others as well.

- To soften or qualify disagreements or disputes, again showing that you recognize the power relationship. The academic community is a rather small one. If you misrepresent an expert’s work or present yours as superior, you could alienate yourself from your chosen scholarly field.

Reasons Related to the Audience of the Document

All documents have an audience. Even if the paper is destined only to be read by the instructor, he or she is still an audience to consider. Further, for academic works at the graduate level, the instructor is a member of the field that you will be joining and, most likely, is a researcher in the field. And, if you’re working toward publication, members of your audience may include those individuals who you are citing.

The audience factors into hedging in the following ways.

- To protect yourself, as the researcher and writer, in presenting material that you are unsure how the audience will respond to. For example, hedging should be used if the information is potentially inflammatory or could offend the reader.

- To prevent misleading the audience when there is a lack of solid, consistent research on a topic, or there is disagreement in the field about that issue.

- To show you understand the expectations of courtesy in your field.

Reasons Related to the Writer

As the writer, you should be careful to hedge for the following reasons.

- To keep from appearing biased or opinionated. Prevents making absolute statements or overstatements that subject your work to criticism or make the research seem simplistic.

- To acknowledge the limitations of your work.

- To protect yourself if you are not sure that the information is correct.

- To divert opinion away from you, particularly if the information is troublesome or potentially inflammatory.

- To convey a level of modesty as well as to show courtesy to your readers and to other researchers. In other words, hedging reflects an awareness of your position within the field.

How do I know if my work needs hedging?

As you read academic articles in your field, you’ll pick up the many subtle ways that authors use hedging within their work. We’d like to mention four specific situations in which authors often employ hedging: to avoid absolute statements, to distance themselves when the subject is controversial, to distance themselves from the evidence if it doesn’t have consistent support in the field, and to distance themselves from the evidence if it (or its author) is well-respected in the field and they want to disagree with it. Let’s discuss each of these situations more fully.

Consider Using Hedging to Avoid Absolute Statements

Generally, the first things to look for in your academic paper to determine if you need to use hedging are absolute statements, overstatements, or broad sweeping generalizations.

An absolute statement makes a direct claim about an issue, idea, or event that may or may not be true, when an issue is a matter of opinion rather than a hard fact. Absolutes are words like all, none, everyone, no one, always, never , etc. They are absolute claims because they imply the statement must be true all of the time, no exceptions.

For example, “everyone should conserve water” is an absolute statement because it makes the absolute claim that everyone should do it. It is also something that the author believes, but that not everyone may agree with. However, the “chemical formula for water is H 2 O” is a hard fact which no one can dispute.

The reason that absolute statements and generalizations are a problem in writing is they open the door to challenges. Unless you have read every piece of research that has ever been done on a given subject, you probably cannot speak with the authority that using an absolute demands. Even respected authors in the field who make absolute claims should probably be treated with some degree of skepticism.

Further, statements of unqualified opinion could make your reader question the objectivity of your methods. In other words, they may question whether you researched the subject thoroughly and analytically or only looked at material that supported your ideas on the subject. Additionally, many absolutes have the potential to offend a reader because they seem to make the writing questionable by coming across as biased or they run counter to the beliefs or knowledge of the reader.

Let’s look at an example.

The current economic problems can be traced to the greed of corporate CEOs, who are more concerned about their own wealth than the wellbeing of others.

While there are many people who may agree with the above statement, the truth is that the issue is much more complicated than this statement would have the reader believe. The sentence seems to make the absolute claim that all CEOs are greedy which could easily offend the reader. Also, most individuals familiar with economic trends would know that the causes of economic issues are complex, so this statement is easily contested. Additionally, the lack of hedging creates a tone that is one of superiority, which only emphasizes the feeling that this statement may not be based on credible research but is an expression of the writer’s own resentment or bias. For a better way to present this information, see the next section.

Consider Using Hedging if the Subject is Controversial

A second thing to consider is whether or not the subject is particularly controversial. Some subject matter will be contested, sometimes hotly, in a given field, and writers often have to pick a side. You need to make sure that the fallacies or limitations of the side you are disputing are adequately presented in a way that focuses on their limitations. Your work should be presented in a manner that points out the logic of your argument rather than just the negatives of the other side. Again, this is as much a matter of knowing your place and your role in your field as a recognition of the power relationships inherent in academia, which gives rise to another reason for hedging in this situation: you may want to distance yourself from inflammatory arguments or opinions.

Consider Using Hedging if the Evidence doesn’t have Consistent Support

Another instance where hedging would be encouraged is when you lack solid, consistent evidence. While it is not uncommon to find dissenting voices in any field of scholarly work, unless the subject is one that has generated a major debate, most works will tend to have fairly consistent support. If for some reason you encounter a subject matter that does not have widespread, consistent support in the field, it is best to hedge. Generally, this would occur if there is a newer piece of scholarship on a subject or a revisiting of an older one.

Consider Using Hedging if You’re Contesting Evidence that is Well-Respected in the Field

Finally, if you are contesting a long-standing or well-respected piece of scholarship, it is best to hedge. This is an issue of modesty. There is nothing wrong with challenging certain pieces of work, but if you do it in a way that does not give credence to the authority of the work, you have the potential to alienate yourself from the field. This is important particularly when dealing with certain historical or theoretical frameworks. For example, almost all historical works dealing with the post-Civil War South will refer in some form to

C. Vann Woodward’s Origins of the New South. While they may not all backup or correspond to Woodward, they at least refer to or build on his thesis. If a writer would suddenly attack or dispute Woodward, the writer not only separates himself or herself from that author, but also all of those who have supported him.

What is hedging and how does it work?

To hedge in writing is to temper the statement. There are two ways you can do this.

One way is to use words that reduce the absolute value of the statement. The other option is to divert the opinion away from the writer.

Using the same example (“The current economic problems can be traced to the greed of corporate CEOs, who are more concerned about their own wealth than the wellbeing of others.”) as the one in the prior section, let’s consider these two methods. Look at this first revision.

CEOs, who seem to be more concerned about their own wealth than the wellbeing of others, may share some of the blame for the current economic problems.

This first sentence uses the tempering method. By using the words may and seem, it no longer places all the blame on corporate leaders.

Since there is a negative connotation to this sentence and since most readers of business research are business people, this may be one of the claims that is best diverted away from you as the writer. One way to do this is to cite a specific expert if available.

Jones (2007) implies that CEOs who appear to be more concerned about their own wealth than the wellbeing of others share some of the blame.

By using the name of an author who expresses this opinion, you move the claim away from yourself as the writer, limiting the potential to offend the audience. In other words, the reader will connect Jones with the negative remark rather than you directly.

Be careful not to change the meaning of your sentence when you use methods of diversion in particular. For example,

In these current economic times, it would be easy to assume that CEOs who appear to be more concerned about their own wealth than the wellbeing of others share some of the blame.

The error that occurs here is that while the claim is diverted from the author by stating “it would be easy to assume” the entire meaning has been changed because of the nuance of the phrase. Now instead of simply diverting the claim, a new one has been created that implies that the assumption is incorrect and that the rest of the paper will discuss the fallacies of this assumption.

How do you know which method to use?

Deciding which method to use depends on the intent of the statement and the audience for the paper. If the audience has a great deal of knowledge on the subject, it may be best to use the diversion method if the statement is not 100% supportable or if it has the potential to offend the audience. Consider this example.

The period of Republican Reconstruction was an absolute failure.

This period of history did have its problems, but a lot of good occurred as well, which most historians recognize. Therefore, it would be best to divert this opinion away from the writer and place the statement on the source that it came from.

In the past, many Southern writers, such as Ramsdell (1964) and Dunning (1907), saw the period of Republican Reconstruction as an absolute failure.

You will want to use tempering when you feel the statement should be made, but cannot make the claim under another’s authority.

Children who do not have parental support will always do poorly in school.

This statement could anger or offend some readers. A tempered version that does not make such a broad sweeping statement would show better audience awareness.

Children without parental support may not do as well in school as those whose parents are actively involved in their education.

You can also use tempering when there is a lack of solid, consistent support. When dealing with a new piece of scholarship, for example, you could use a method that implies that this is important, but that it is still new.

This method of managing culturally diverse teams, though not tested in a vast array of businesses, shows promise for future applications.

Here, the sentence acknowledges that the research is limited, but expresses the view that it seems to be a good method.

Practice Exercises

Each of the sentences below is an absolute statement. Rewrite the sentence using one of the methods of hedging.

- Female managers, due to their nurturing nature, avoid confrontation and delegation of duties.

- The standardized method of testing is ineffective for indicating student success.

- Corporations operating overseas do so to avoid environment regulations and other methods of corporate governance.

- Play therapy is the best option when working with children.

- Poststructuralist theory can only be seen as destructive since it questions other epistemological frameworks without providing alternatives.

- The use of cultural dialect in The Complete Tales of Uncle Remus is insulting and demeaning to African Americans.

- Sex education always leads to promiscuity in young people.

- Graduate schools consider GPA above all other elements when determining a student’s admission.

- The only way to help alleviate the pain from this disorder is through physical therapy.

- Managers will be unable to initiate changes within an organization if they do not have the support of their employees.

- Never use that font for this style of writing.

- That structure has a shoddy design and shows terrible workmanship.

- Only female nurses will be able to develop an empathetic relationship with the patient.

- Exercise between activities is the only way to keep children focused during the day.

- Graft and corruption are rampant in today’s workplace.

Note that the answers here are just one option. There may be other ways to rewrite these sentences. Try more than one strategy and consider the difference in meaning between them. Also, be aware that if you use diversion, you may need to provide names of researchers who say that (see questions 1, 5, 7, and 13).

- Some claim that female managers avoid confrontation and delegation of duties because women are more nurturing.

- The standardized method of testing may not be the most effective method of indicating student success.

- Some of the corporations operating overseas do so to avoid environmental regulations and other methods of corporate governance.

- Play therapy can be an effective option when working with children.

- Many philosophers claim that poststructuralist theory can only be seen as destructive since it questions other epistemological frameworks without providing alternatives.

- The use of cultural dialect in The Complete Tales of Uncle Remus is sometimes considered to be insulting and demeaning to African Americans.

- Critics maintain that sex education can lead to promiscuity in young people.

- Graduate schools consider several elements, including GPA, when determining a student’s admission.

- To date, physical therapy has been the most effective method of alleviating pain with this disorder.

- Managers who do not have the support of their employees will have a more difficult time initiating changes within their organization.

- Style guides discourage the use of a font other than one with a serif for this style of writing.

- That structure appears to have been poorly designed and the workmanship seems questionable.

- Studies suggest that patients see female nurses as more empathetic than their male counterparts.

- Children who have some movement between educational activities appear to be able to focus their attention better.

- Unethical behavior appears to be more common in today’s workplace.

Hedging in academic writing

If you read a lot of academic papers, you will have noticed lots of might , appear ( s ) to , and possibly ’s. perhaps you will have wondered why rigorous research sounds so tentative. but these and other similar terms, called hedging, have their use in academic writing..

What is hedging Hedging can be defined as the expression of the degree of certainty of a statement. Hedging language encompasses a broad range of terms and phrases; mainly verbs, but also adverbs, nouns and ‘that’ clauses. The following are very common.

-Hedging verbs: appear , seem -Modal verbs: may , might , could , can -'That' clauses: it is clear / apparent / likely / probable that …, it has been suggested that …

Combinations of the above are also frequent, e.g. It appears that a fast solution method may be needed .

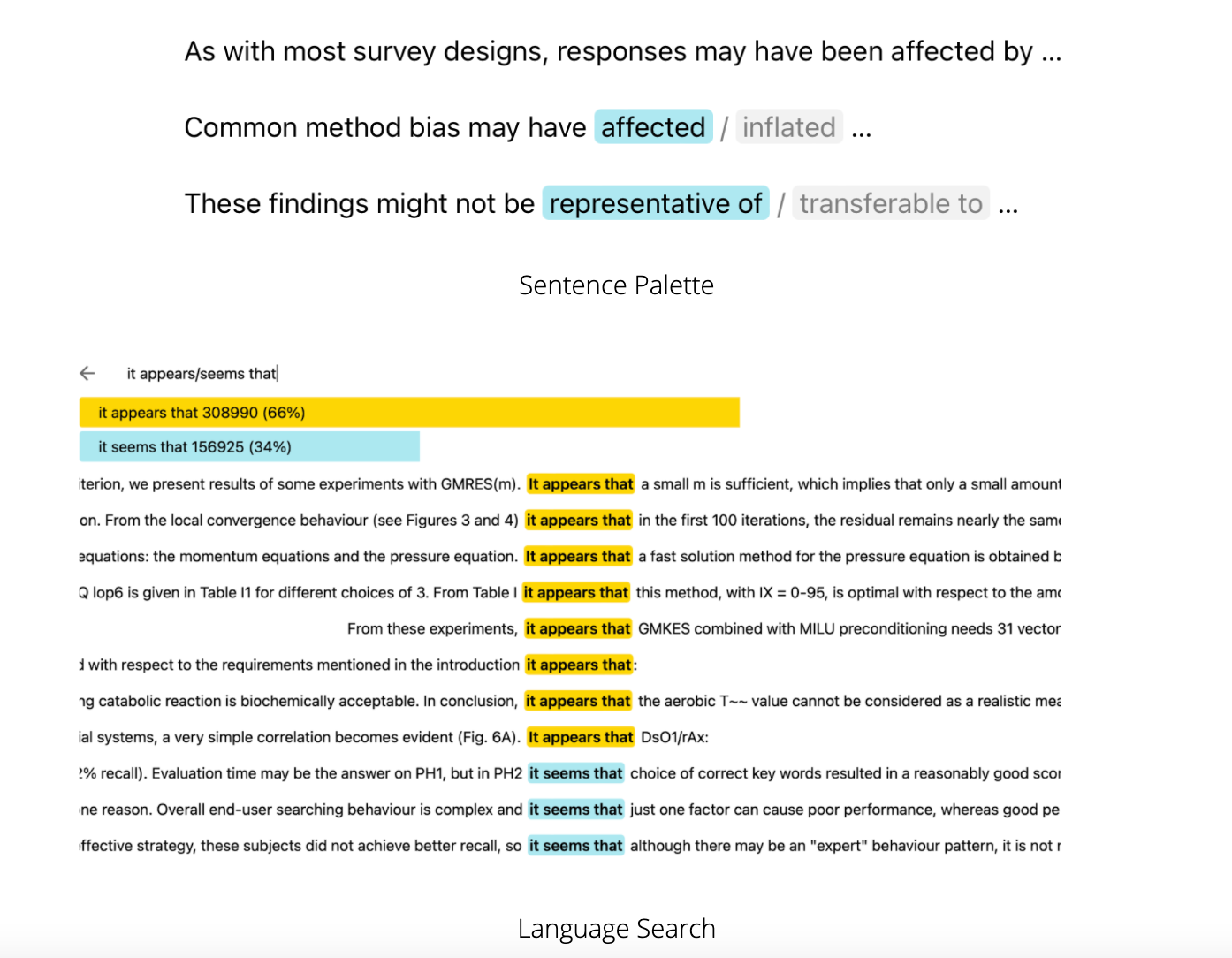

Why is hedging often used in papers The point of research is to provide answers to questions. But in most scientific fields, providing clear and definite answers is difficult. Findings can be said to be true under certain experimental conditions (method, sample or participants used) only. They cannot be generalized unless replicated by studies using different conditions, and may even be refuted in the future. So there is a need to express various degrees of certainty when reviewing literature or discussing findings.

How to use hedging in your paper The following tips will help you find the right words and phrases to express caution and uncertainty in your academic text.

- Understand nuances and gradations of meaning between different hedging terms. Some express more certainty than others (e.g. probably > possibly ; can > could ). Don’t be afraid to dig out old dictionaries and grammar textbooks to be sure.

- Assess the degree of certainty of claims and findings. Are you reporting preliminary results, or results from a replication study? How confident are you in the reliability of your method? Answers to such questions will inform your word choice.

- Notice hedging patterns in papers you read. What words or word combinations are commonly used in your field? In which section(s) does hedging feature most? Even better, check out Writefull’s Language Search for examples of use in context. Or browse the Sentence Palette for template sentences containing hedging.

- Variety is the spice of academic writing. Make use of hedging through different strategies, such as a mix of those listed above. But don’t overdo it! There’s no need to use hedging when reporting established facts or theorems.

Read more about heading here .

Writefull webinars

Looking for more academic writing tips? Join our free webinars hosted by Writefull's linguists!

On Hedging in Teaching Academic Writing

- Conference paper

- First Online: 07 May 2020

- Cite this conference paper

- Irina Avkhacheva ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6599-7783 10 ,

- Irina Barinova ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1852-4091 10 &

- Natalia Nesterova ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9064-6742 10

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems ((LNNS,volume 131))

Included in the following conference series:

- Proceedings of the Conference “Integrating Engineering Education and Humanities for Global Intercultural Perspectives”

952 Accesses

1 Citations

The article addresses the issues associated with teaching academic writing to Master students, post-graduate students as well as researchers and professionals with non-linguistic background. The problem is considered in the framework of the concept of Context and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) approach to foreign language acquisition. The distinctive feature of this approach is that the content of the subject is subordinate to the languages-related goals. To achieve these goals a language instructor has to accomplish a number of tasks to provide language and stylistic adequacy associated with the avoidance of categorical and straightforward judgements. The phenomenon known as hedging or understatement is recognized as an essential characteristic of scientific discourse. However, until recently, little attention was given to developing students’ skills to tone down when formulating hypotheses, sharing their ideas and standpoints, reporting results and commenting on other authors’ opinion. The present article focuses on the following aspects of teaching academic writing: the role of hedging in scientific discourse, the language resources used to express authors’ “confident uncertainty” and the typical contexts and situations where hedging is a must. It presents the information about the experimental study into students’ awareness of hedging and their ability to realize hedging techniques when producing research papers. Based on the research done, general approach to developing the required skills is suggested, along with the recommendations concerning some teaching techniques and forms of training.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Applying Language Learning Principles to Coursebooks

Empowering Hispanics in Higher Education Through the Operationalization of Academic English Strategies

Wierzbicka, A.: Cross-Cultural Pragmatics. The Semantics of Human Interaction. Mouton de Gruyter, N.Y (1991)

Book Google Scholar

Varttala, T.: Hedging in Scientifically Oriented Discourse: Exploring Variation According to Discipline and Intended Audience. University of Tampere, Tampere (2001)

Google Scholar

Hyland, K.: Hedging in academic writing and EAF textbooks. Engl. Specif. Purp. 13 (3), 239–256 (1994)

Article Google Scholar

Lakoff, G.: Hedges: a study in meaning criteria and the logic of fuzzy concepts. J. Philos. Logic 2 (4), 458–508 (1973)

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Hyland, K.: Hedging in Scientific Research Articles. John Benjamins, Amsterdam (1998)

Thao, Q.T., Duong, T.M.: Hedging: a comparative study of research article results and discussion section in applied linguistics and chemical engineering. Engl. Specif. Purp. World 41 (14) (2013). https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/HEDGING%3A-A-COMPARATIVE-STUDY-OF-RESEARCH-ARTICLE-IN-Tran-Duong/d35ecce5bfd4df9271ec9ffb5ac7d1486c0054b0 . Accessed 22 Mar 2020

Salager-Meyer, F.: Hedges and textual communicative function in medical English written discourse. Engl. Specif. Purp. 13 (2), 149–170 (1994)

Falahati, R.: A contrastive study of hedging in English and Farsi academic discourse. Engl. Specif. Purp. 5 , 49–67 (2008)

Crompton, P.: Hedging in academic writing: some theoretical problems (1997). Engl. Specif. Purp. 16 (4), 271–287 (1997)

Hubler, A.: Understatements and Hedges in English. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam/Philadelphia (1983)

Cryslal, D.: English as a Global Language. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1997)

Visson, L.: Where Russians Go Wrong in Spoken English: Words and Phrases in the Context of Two Cultures. R. Valent, Moscow (2013)

Dzhioeva, A.A., Ivanova, V.G.: Understatement kak otrazhenie anglo-saksonskogo mentaliteta [Understatement as reflection of Anglo-Saxon mentality]. Engl. Humanit. Theory Pract. 3 , 5–29 (2009). (in Russian)

Ivanova, V.G.: Lingvisticheskie aspekty izucheniya understatement v sovremennom anglijskom yazyke [Linguistic aspects of understatement in modern English]. MGIMO Bull. Phil. 5 (32), 253–260 (2013). (in Russian)

Shchukareva, N.S.: Sposoby vyrazheniya nekategorichnosti vyskazyvaniya v anglijskom yazyke [Ways of expressing non-categorical statements in English (on the material of scientific discussions)]. In: Functional Style of Scientific Prose. Issues of Linguistics and Methods of Teaching, Moscow, pp. 198–206 (1980). (in Russian)

Vetrova, O.: The culture of scientific communication: hedging in academic discourse. In: Pavlov, V. (ed.) The XXV International Scientific and Practical Conference and the II Stage of Research Analytics Championship in Pedagogical Sciences, Psychological Sciences and the I Stage of the Research Analytics Championship in the Philological Sciences 2012, London, pp. 120–121 (2012)

Wallwork, A.: English for Writing Research Papers. Springer, London (2011)

Garwood, C.: The teaching of English to the non-English-speaking technical students. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2 (24), 107–112 (1970)

Shcherba, L.V.: Yazykovaya sistema i rechevaya deyatel’nost’ [Language System and Speech Activity]. Nauka, Leningrad (1974). (in Russian)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Perm National Research Polytechnic University, Perm, 614000, Russia

Irina Avkhacheva, Irina Barinova & Natalia Nesterova

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Natalia Nesterova .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Research Centre Kairos, Tomsk, Russia

Zhanna Anikina

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Avkhacheva, I., Barinova, I., Nesterova, N. (2020). On Hedging in Teaching Academic Writing. In: Anikina, Z. (eds) Integrating Engineering Education and Humanities for Global Intercultural Perspectives. IEEHGIP 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 131. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47415-7_52

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47415-7_52

Published : 07 May 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-47414-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-47415-7

eBook Packages : Intelligent Technologies and Robotics Intelligent Technologies and Robotics (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- EW Liaison Portal

- Academic Essay

- Analytical Art Essay

- Analytical Book Review

- Analytical Film Review

- Argumentative Essay

- Literature Reviews

- Project Report

- Reflective Essay

- Disciplinary Genres

- Useful Links

You are here

| --> | |||||||

| |

- Writing body paragraphs

- Useful resources

- Assignment Guidelines

- Assignment Guideline

5. Hedging

While you want to convince the reader that your arguments are valid, be careful not to use overly strong language. Expressing opinions or making claims in overly strong language leaves you open to attack by critical readers. Such statements will often be doubted by readers thereby reducing your power and authority as a writer. To avoid such a situation, when stating ideas, you should use tentative rather than assertive language. This is known as hedging.

Below is a list of common hedging techniques.

1. Use hedging verbs

The following ‘hedging’ verbs are often used in academic writing :

suggest indicate estimate imply

E.g. The results indicate that social networking sites can enhance the cohesion of communities.

The verb appear is used to ‘distance’ the writer from the findings (and therefore avoid making a strong claim and be subject to criticism from readers).

E.g. On the evidence of the research findings, it would appear not all students can benefit equally from online learning.

Note that the writer also ‘protects’ himself or herself by using the phrase on the evidence of . The following expressions are used in a similar way: according to , on the basis of , based on .

2. Use modal verbs

Another way of appearing ‘confidently uncertain’ is to use modal verbs such as may , might and could .

E.g. In the case of students from low income families, they may feel disadvantaged by not having a stable Internet connection to follow online lessons.

3. Use adverbs

The following adverbs are often used when a writer wishes to express caution.

probably possibly perhaps arguably

apparently seemingly presumably conceivably

E.g. As well as being divisive, the existence of fraudulent information is arguably a threat to the very principles of an egalitarian society.

4. Use adjectives

Another technique is to use an adjective.

probable possible arguable unlikely likely

E.g. A possible solution to address students’ Internet addiction is that universities can extend their intervention programmes to the management of student stress levels.

E.g. With timely intervention, it is likely that students will be able to handle their stress more effectively.

5. Use nouns

The following nouns are often used to hedge:

probability possibility evidence likelihood indication

E.g. The evidence suggests that undergraduates could benefit from more face-to-face social interaction on campus.

E.g. There is some indication in the research literature that online gaming could lead to Internet addiction.

For Writing Teachers

- Learn@PolyU

- EWR Consultation Booking

- Information Package for NEW Writing Teachers (Restricted Access)

- Useful materials

For CAR Teachers

- Writing Requirement Information

- Reading Requirement Information

About this website

This website is an open access website to share our English Writing Requirement (General Education) writing support materials to support these courses

- to support PolyU students’ literacy development within and across the disciplines

- to support subject and language teachers to implement system-level measures for integrating literacy-sensitive pedagogies across the university