50 Great Peer Review Examples: Sample Phrases + Scenarios

by Emre Ok March 16, 2024, 10:48 am updated August 8, 2024, 12:19 pm 1.8k Views

Peer review is a concept that has multiple different applications and definitions. Depending on your field, the definition of peer review can change greatly.

In the workplace, the meaning of peer review or peer feedback is that it is simply the input of a peer or colleague on another peer’s performance, attitude, output, or any other performance metric .

While in the academic world peer review’s definition is the examination of an academic paper by another fellow scholar in the field.

Even in the American legal system , people are judged in front of a jury made up of their peers.

It is clear as day that peer feedback carries a lot of weight and power. The input from someone who has the same experience with you day in and day out is on occasion, more meaningful than the feedback from direct reports or feedback from managers .

So here are 50 peer review examples and sample peer feedback phrases that can help you practice peer-to-peer feedback more effectively!

Table of Contents

Peer Feedback Examples: Offering Peers Constructive Criticism

One of the most difficult types of feedback to offer is constructive criticism. Whether you are a chief people officer or a junior employee, offering someone constructive criticism is a tight rope to walk.

When you are offering constructive criticism to a peer? That difficulty level is doubled. People can take constructive criticism from above or below.

One place where criticism can really sting is when it comes from someone at their level. That is why the peer feedback phrases below can certainly be of help.

Below you will find 10 peer review example phrases that offer constructive feedback to peers:

- “I really appreciate the effort you’ve put into this project, especially your attention to detail in the design phase. I wonder if considering alternative approaches to the user interface might enhance user engagement. Perhaps we could explore some user feedback or current trends in UI design to guide us.”

- “Your presentation had some compelling points, particularly the data analysis section. However, I noticed a few instances where the connection between your arguments wasn’t entirely clear. For example, when transitioning from the market analysis to consumer trends, a clearer linkage could help the audience follow your thought process more effectively.”

- “I see you’ve put a lot of work into developing this marketing strategy, and it shows promise. To address the issue with the target demographic, it might be beneficial to integrate more specific market research data. I can share a few resources on market analysis that could provide some valuable insights for this section.”

- “You’ve done an excellent job balancing different aspects of the project, but I think there’s an opportunity to enhance the overall impact by integrating some feedback we received in the last review. For instance, incorporating more user testimonials could strengthen our case study section.”

- “Your report is well-structured and informative. I would suggest revisiting the conclusions section to ensure that it aligns with the data presented earlier. Perhaps adding a summary of key findings before concluding would reinforce the report’s main takeaways.”

- “In reviewing your work, I’m impressed by your analytical skills. I believe using ‘I’ statements could make your argument even stronger, as it would provide a personal perspective that could resonate more with the audience. For example, saying ‘I observed a notable trend…’ instead of ‘There is a notable trend…’ can add a personal touch.”

- “Your project proposal is thought-provoking and innovative. To enhance it further, have you considered asking reflective questions at the end of each section? This could encourage the reader to engage more deeply with the material, fostering a more interactive and thought-provoking dialogue.”

- “I can see the potential in your approach to solving this issue, and I believe with a bit more refinement, it could be very effective. Maybe a bit more focus on the scalability of the solution could highlight its long-term viability, which would be impressive to stakeholders.”

- “I admire the dedication you’ve shown in tackling this challenging project. If you’re open to it, I would be happy to collaborate on some of the more complex aspects, especially the data analysis. Together, we might uncover some additional insights that could enhance our findings.”

- “Your timely submission of the project draft is commendable. To make your work even more impactful, I suggest incorporating recent feedback we received on related projects. This could provide a fresh perspective and potentially uncover aspects we might not have considered.”

Sample Peer Review Phrases: Positive Reinforcement

Offering positive feedback to peers as opposed to constructive criticism is on the easier side when it comes to the feedback spectrum.

There are still questions that linger however, such as: “ How to offer positive feedback professionally? “

To help answer that question and make your life easier when offering positive reinforcements to peers, here are 10 positive peer review examples! Feel free to take any of the peer feedback phrases below and use them in your workplace in the right context!

- “Your ability to distill complex information into easy-to-understand visuals is exceptional. It greatly enhances the clarity of our reports.”

- “Congratulations on surpassing this quarter’s sales targets. Your dedication and strategic approach are truly commendable.”

- “The innovative solution you proposed for our workflow issue was a game-changer. It’s impressive how you think outside the box.”

- “I really appreciate the effort and enthusiasm you bring to our team meetings. It sets a positive tone that encourages everyone.”

- “Your continuous improvement in client engagement has not gone unnoticed. Your approach to understanding and addressing their needs is exemplary.”

- “I’ve noticed significant growth in your project management skills over the past few months. Your ability to keep things on track and communicate effectively is making a big difference.”

- “Thank you for your proactive approach in the recent project. Your foresight in addressing potential issues was key to our success.”

- “Your positive attitude, even when faced with challenges, is inspiring. It helps the team maintain momentum and focus.”

- “Your detailed feedback in the peer review process was incredibly helpful. It’s clear you put a lot of thought into providing meaningful insights.”

- “The way you facilitated the last workshop was outstanding. Your ability to engage and inspire participants sparked some great ideas.”

Peer Review Examples: Feedback Phrases On Skill Development

Peer review examples on talent development are one of the most necessary forms of feedback in the workplace.

Feedback should always serve a purpose. Highlighting areas where a peer can improve their skills is a great use of peer review.

Peers have a unique perspective into each other’s daily life and aspirations and this can quite easily be used to guide each other to fresh avenues of skill development.

So here are 10 peer sample feedback phrases for peers about developing new skillsets at work:

- “Considering your interest in data analysis, I think you’d benefit greatly from the advanced Excel course we have access to. It could really enhance your data visualization skills.”

- “I’ve noticed your enthusiasm for graphic design. Setting a goal to master a new design tool each quarter could significantly expand your creative toolkit.”

- “Your potential in project management is evident. How about we pair you with a senior project manager for a mentorship? It could be a great way to refine your skills.”

- “I came across an online course on persuasive communication that seems like a perfect fit for you. It could really elevate your presentation skills.”

- “Your technical skills are a strong asset to the team. To take it to the next level, how about leading a workshop to share your knowledge? It could be a great way to develop your leadership skills.”

- “I think you have a knack for writing. Why not take on the challenge of contributing to our monthly newsletter? It would be a great way to hone your writing skills.”

- “Your progress in learning the new software has been impressive. Continuing to build on this momentum will make you a go-to expert in our team.”

- “Given your interest in market research, I’d recommend diving into analytics. Understanding data trends could provide valuable insights for our strategy discussions.”

- “You have a good eye for design. Participating in a collaborative project with our design team could offer a deeper understanding and hands-on experience.”

- “Your ability to resolve customer issues is commendable. Enhancing your conflict resolution skills could make you even more effective in these situations.”

Peer Review Phrase Examples: Goals And Achievements

Equally important as peer review and feedback is peer recognition . Being recognized and appreciated by one’s peers at work is one of the best sentiments someone can experience at work.

Peer feedback when it comes to one’s achievements often comes hand in hand with feedback about goals.

One of the best goal-setting techniques is to attach new goals to employee praise . That is why our next 10 peer review phrase examples are all about goals and achievements.

While these peer feedback examples may not directly align with your situation, customizing them according to context is simple enough!

- “Your goal to increase client engagement has been impactful. Reviewing and aligning these goals quarterly could further enhance our outreach efforts.”

- “Setting a goal to reduce project delivery times has been a great initiative. Breaking this down into smaller milestones could provide clearer pathways to success.”

- “Your aim to improve team collaboration is commendable. Identifying specific collaboration tools and practices could make this goal even more attainable.”

- “I’ve noticed your dedication to personal development. Establishing specific learning goals for each quarter could provide a structured path for your growth.”

- “Celebrating your achievement in enhancing our customer satisfaction ratings is important. Let’s set new targets to maintain this positive trajectory.”

- “Your goal to enhance our brand’s social media presence has yielded great results. Next, we could focus on increasing engagement rates to build deeper connections with our audience.”

- “While striving to increase sales is crucial, ensuring we have measurable and realistic targets will help maintain team morale and focus.”

- “Your efforts to improve internal communication are showing results. Setting specific objectives for team meetings and feedback sessions could further this progress.”

- “Achieving certification in your field was a significant milestone. Now, setting a goal to apply this new knowledge in our projects could maximize its impact.”

- “Your initiative to lead community engagement projects has been inspiring. Let’s set benchmarks to track the positive changes and plan our next steps in community involvement.”

Peer Evaluation Examples: Communication Skills

The last area of peer feedback we will be covering in this post today is peer review examples on communication skills.

Since the simple act of delivering peer review or peer feedback depends heavily on one’s communication skills, it goes without saying that this is a crucial area.

Below you will find 10 sample peer evaluation examples that you can apply to your workplace with ease.

Go over each peer review phrase and select the ones that best reflect the feedback you want to offer to your peers!

- “Your ability to articulate complex ideas in simple terms has been a great asset. Continuously refining this skill can enhance our team’s understanding and collaboration.”

- “The strategies you’ve implemented to improve team collaboration have been effective. Encouraging others to share their methods can foster a more collaborative environment.”

- “Navigating the recent conflict with diplomacy and tact was impressive. Your approach could serve as a model for effective conflict resolution within the team.”

- “Your active listening during meetings is commendable. It not only shows respect for colleagues but also ensures that all viewpoints are considered, enhancing our decision-making process.”

- “Your adaptability in adjusting communication styles to different team members is key to our project’s success. This skill is crucial for maintaining effective collaboration across diverse teams.”

- “The leadership you displayed in coordinating the team project was instrumental in its success. Your ability to align everyone’s efforts towards a common goal is a valuable skill.”

- “Your presentation skills have significantly improved, effectively engaging and informing the team. Continued focus on this area can make your communication even more impactful.”

- “Promoting inclusivity in your communication has positively influenced our team’s dynamics. This approach ensures that everyone feels valued and heard.”

- “Your negotiation skills during the last project were key to reaching a consensus. Developing these skills further can enhance your effectiveness in future discussions.”

- “The feedback culture you’re fostering is creating a more dynamic and responsive team environment. Encouraging continuous feedback can lead to ongoing improvements and innovation.”

Best Way To Offer Peer Feedback: Using Feedback Software!

If you are offering feedback to peers or conducting peer review, you need a performance management tool that lets you digitize, streamline, and structure those processes effectively.

To help you do just that let us show you just how you can use the best performance management software for Microsoft Teams , Teamflect, to deliver feedback to peers!

While this particular example approaches peer review in the form of direct feedback, Teamflect can also help implement peer reviews inside performance appraisals for a complete peer evaluation.

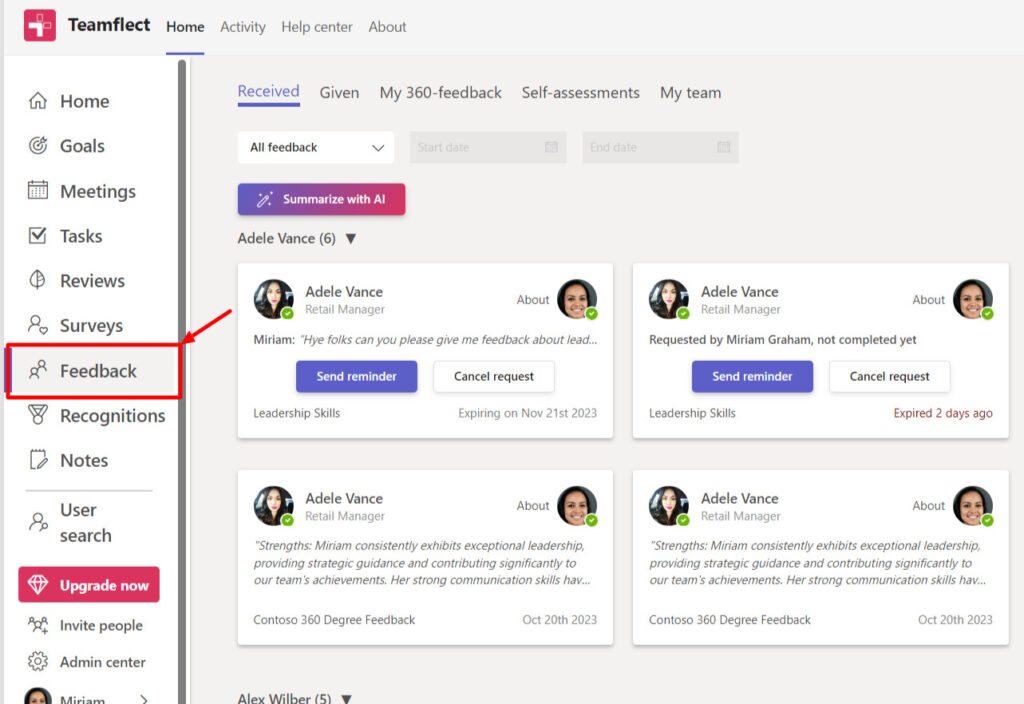

Step 1: Head over to Teamflect’s Feedback Module

While Teamflect users can exchange feedback without leaving Microsoft Teams chat with the help of customizable feedback templates, the feedback module itself serves as a hub for all the feedback given and received.

Once inside the feedback module, all you have to do is click the “New Feedback” button to start giving structured and effective feedback to your peers!

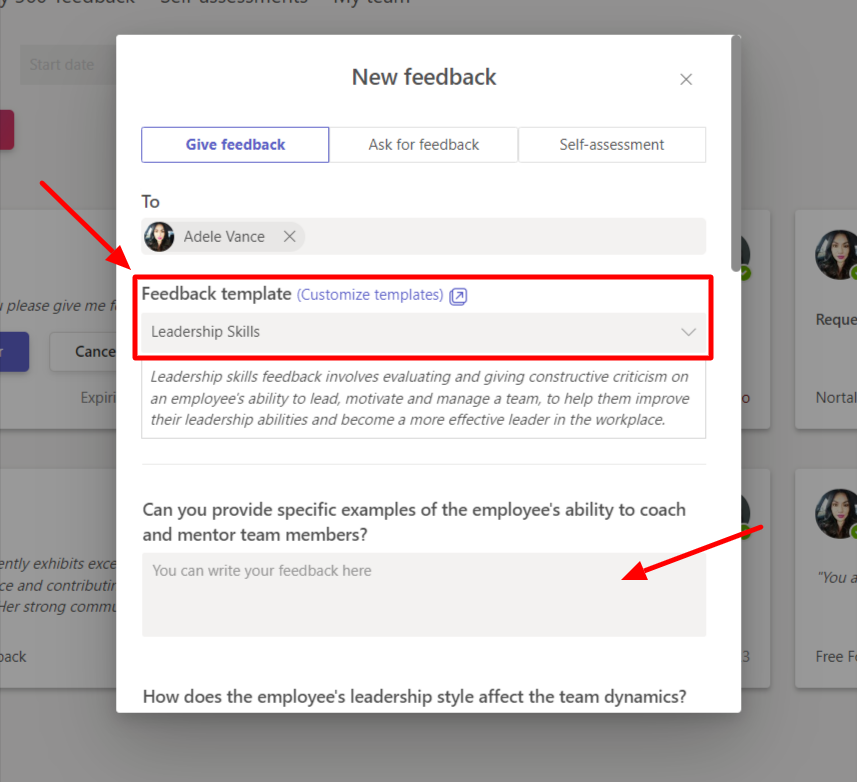

Step 2: Select a feedback template

Teamflect has an extensive library of customizable feedback templates. You can either directly pick a template that best fits the topic on which you would like to deliver feedback to your peer or create a custom feedback template specifically for peer evaluations.

Once you’ve chosen your template, you can start giving feedback right then and there!

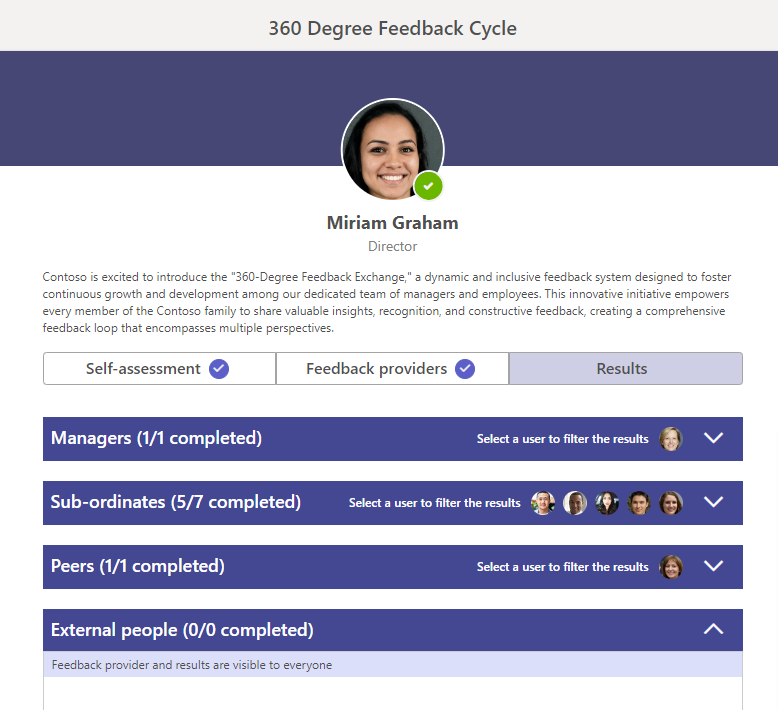

Optional: 360-Degree Feedback

Why stop with peer review? Include all stakeholders around the performance cycle into the feedback process with one of the most intuitive 360-degree feedback systems out there.

Request feedback about yourself or about someone else from everyone involved in their performance, including managers, direct reports, peers, and external parties.

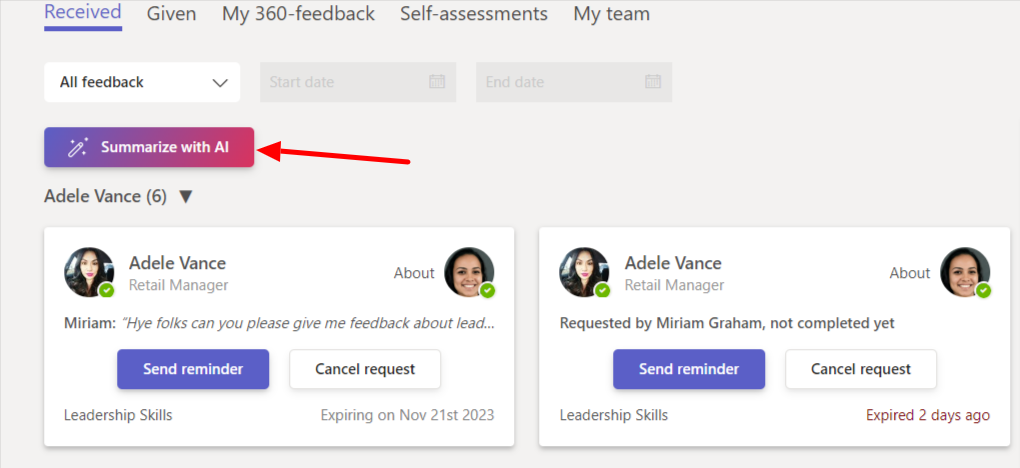

Optional: Summarize feedback with AI

If you have more feedback on your hands then you can go through, summarize that feedback with the help of Teamflect’s AI assistant!

What Are The Benefits of Implementing Peer Review Systems?

Peer reviews have plenty of benefits to the individuals delivering the peer review, the ones receiving the peer evaluation, as well as the organization itself. So here are the 5 benefits of implementing peer feedback programs organization-wide.

1. Enhanced Learning and Understanding Peer feedback promotes a deeper engagement with the material or project at hand. When individuals know they will be receiving and providing feedback, they have a brand new incentive to engage more thoroughly with the content.

2. Cultivation of Open Communication and Continuous Improvement Establishing a norm where feedback is regularly exchanged fosters an environment of open communication. People become more accustomed to giving and receiving constructive criticism, reducing defensiveness, and fostering a culture where continuous improvement is the norm.

3. Multiple Perspectives Enhance Quality Peer feedback introduces multiple viewpoints, which can significantly enhance the quality of work. Different perspectives can uncover blind spots, introduce new ideas, and challenge existing ones, leading to more refined and well-rounded outcomes.

4. Encouragement of Personal and Professional Development Feedback from peers can play a crucial role in personal and professional growth. It can highlight areas of strength and identify opportunities for development, guiding individuals toward their full potential.

Related Posts:

Written by emre ok.

Emre is a content writer at Teamflect who aims to share fun and unique insight into the world of performance management.

15 Performance Review Competencies to Track in 2024

10 Best Employee Promotion Interview Questions & Answers!

- Performance Management

70 Peer Review Examples: Powerful Phrases You Can Use

- October 30, 2023

The blog is tailored for HR professionals looking to set up and improve peer review feedback within their organization. Share the article with your employees as a guide to help them understand how to craft insightful peer review feedback.

Peer review is a critical part of personal development, allowing colleagues to learn from each other and excel at their job. Crafting meaningful and impactful feedback for peers is an art. It’s not just about highlighting strengths and weaknesses; it’s about doing so in a way that motivates others.

In this blog post, we will explore some of the most common phrases you can use to give peer feedback. Whether you’re looking for a comment on a job well done, offer constructive criticism , or provide balanced and fair feedback, these peer review examples will help you communicate your feedback with clarity and empathy.

Peer review feedback is the practice of colleagues and co-workers assessing and providing meaningful feedback on each other’s performance. It is a valuable instrument that helps organizations foster professional development, teamwork, and continuous improvement.

Peoplebox lets you conduct effective peer reviews within minutes. You can customize feedback, use tailored surveys, and seamlessly integrate it with your collaboration tools. It’s a game-changer for boosting development and collaboration in your team.

Why are Peer Reviews Important?

Here are some compelling reasons why peer review feedback is so vital:

Broader Perspective: Peer feedback offers a well-rounded view of an employee’s performance. Colleagues witness their day-to-day efforts and interactions, providing a more comprehensive evaluation compared to just a supervisor’s perspective.

Skill Enhancement: It serves as a catalyst for skill enhancement. Constructive feedback from peers highlights areas of improvement and offers opportunities for skill development.

Encourages Accountability: Peer review fosters a culture of accountability . Knowing that one’s work is subject to review by peers can motivate individuals to perform at their best consistently.

Team Cohesion: It strengthens team cohesion by promoting open communication. and constructive communication. Teams that actively engage in peer feedback often develop a stronger sense of unity and shared purpose.

Fair and Unbiased Assessment: By involving colleagues, peer review helps ensure a fair and unbiased assessment. It mitigates the potential for supervisor bias and personal favoritism in performance evaluations .

Identifying Blind Spots: Peers can identify blind spots that supervisors may overlook. This means addressing issues at an early stage, preventing them from escalating.

Motivation and Recognition: Positive peer feedback can motivate employees and offer well-deserved recognition for their efforts. Acknowledgment from colleagues can be equally, if not more, rewarding than praise from higher-ups.

Now, let us look at the best practices for giving peer feedback in order to leverage its benefits effectively.

30 Positive Peer Feedback Examples

Now that we’ve established the importance of peer review feedback, the next step is understanding how to use powerful phrases to make the most of this evaluation process. In this section, we’ll equip you with various examples of phrases to use during peer reviews, making the journey more confident and effective for you and your team .

Must Read: 60+ Self-Evaluation Examples That Can Make You Shine

Peer Review Example on Work Quality

When it comes to recognizing excellence, quality work is often the first on the list. Here are some peer review examples highlighting the work quality:

- “Kudos to Sarah for consistently delivering high-quality reports that never fail to impress both clients and colleagues. Her meticulous attention to detail and creative problem-solving truly set the bar high.”

- “John’s attention to detail and unwavering commitment to excellence make his work a gold standard for the entire team. His consistently high-quality contributions ensure our projects shine.”

- “Alexandra’s dedication to maintaining the project’s quality standards sets a commendable benchmark for the entire department. Her willingness to go the extra mile is a testament to her work ethic and quality focus.”

- “Patrick’s dedication to producing error-free code is a testament to his commitment to work quality. His precise coding and knack for bug spotting make his work truly outstanding.”

Peer Review Examples on Competency and Job-Related Skills

Competency and job-related skills set the stage for excellence. Here’s how you can write a peer review highlighting this particular skill set:

- “Michael’s extensive knowledge and problem-solving skills have been instrumental in overcoming some of our most challenging technical hurdles. His ability to analyze complex issues and find creative solutions is remarkable. Great job, Michael!”

- “Emily’s ability to quickly grasp complex concepts and apply them to her work is truly commendable. Her knack for simplifying the intricate is a gift that benefits our entire team.”

- “Daniel’s expertise in data analysis has significantly improved the efficiency of our decision-making processes. His ability to turn data into actionable insights is an invaluable asset to the team.”

- “Sophie’s proficiency in graphic design has consistently elevated the visual appeal of our projects. Her creative skills and artistic touch add a unique, compelling dimension to our work.”

Peer Review Sample on Leadership Skills

Leadership ability extends beyond a mere title; it’s a living embodiment of vision and guidance, as seen through these exceptional examples:

- “Under Lisa’s leadership, our team’s morale and productivity have soared, a testament to her exceptional leadership skills and hard work. Her ability to inspire, guide, and unite the team in the right direction is truly outstanding.”

- “James’s ability to inspire and lead by example makes him a role model for anyone aspiring to be a great leader. His approachability and strong sense of ethics create an ideal leadership model.”

- “Rebecca’s effective delegation and strategic vision have been the driving force behind our project’s success. Her ability to set clear objectives, give valuable feedback, and empower team members is truly commendable.”

- “Victoria’s leadership style fosters an environment of trust and innovation, enabling our team to flourish in a great way. Her encouragement of creativity and openness to diverse ideas is truly inspiring.”

Feedback on Teamwork and Collaboration Skills

Teamwork is where individual brilliance becomes collective success. Here are some peer review examples highlighting teamwork:

- “Mark’s ability to foster a collaborative environment is infectious; his team-building skills unite us all. His open-mindedness and willingness to listen to new ideas create a harmonious workspace.”

- “Charles’s commitment to teamwork has a ripple effect on the entire department, promoting cooperation and synergy. His ability to bring out the best in the rest of the team is truly remarkable.”

- “David’s talent for bringing diverse perspectives together enhances the creativity and effectiveness of our group projects. His ability to unite us under a common goal fosters a sense of belonging.”

Peer Review Examples on Professionalism and Work Ethics

Professionalism and ethical conduct define a thriving work culture. Here’s how you can write a peer review highlighting work ethics in performance reviews :

- “Rachel’s unwavering commitment to deadlines and ethical work practices is a model for us all. Her dedication to punctuality and ethics contributes to a culture of accountability.”

- “Timothy consistently exhibits the highest level of professionalism, ensuring our clients receive impeccable service. His courtesy and reliability set a standard of excellence.”

- “Daniel’s punctuality and commitment to deadlines set a standard of professionalism we should all aspire to. His sense of responsibility is an example to us all.”

- “Olivia’s unwavering dedication to ethical business practices makes her a trustworthy and reliable colleague. Her ethical principles create an atmosphere of trust and respect within our team, leading to a more positive work environment.”

Feedback on Mentoring and Support

Mentoring and support pave the way for future success. Check out these peer review examples focusing on mentoring:

- “Ben’s dedication to mentoring new team members is commendable; his guidance is invaluable to our junior colleagues. His approachability and patience create an environment where learning flourishes.”

- “David’s mentorship has been pivotal in nurturing the talents of several team members beyond his direct report, fostering a culture of continuous improvement. His ability to transfer knowledge is truly outstanding.”

- “Laura’s patient mentorship and continuous support for her colleagues have helped elevate our team’s performance. Her constructive feedback and guidance have made a remarkable difference.”

- “William’s dedication to knowledge sharing and mentoring is a driving force behind our team’s constant learning and growth. His commitment to others’ development is inspiring.”

Peer Review Examples on Communication Skills

Effective communication is the linchpin of harmonious collaboration. Here are some peer review examples to highlight your peer’s communication skills:

- “Grace’s exceptional communication skills ensure clarity and cohesion in our team’s objectives. Her ability to articulate complex ideas in a straightforward manner is invaluable.”

- “Oliver’s ability to convey complex ideas with simplicity greatly enhances our project’s success. His effective communication style fosters a productive exchange of ideas.”

- “Aiden’s proficiency in cross-team communication ensures that our projects move forward efficiently. His ability to bridge gaps in understanding is truly commendable.”

Peer Review Examples on Time Management and Productivity

Time management and productivity are the engines that drive accomplishments. Here are some peer review examples highlighting time management:

- “Ella’s time management is nothing short of exemplary; it sets a benchmark for us all. Her efficient task organization keeps our projects on track.”

- “Robert’s ability to meet deadlines and manage time efficiently significantly contributes to our team’s overall productivity. His time management skills are truly remarkable.”

- “Sophie’s time management skills are a cornerstone of her impressive productivity, inspiring us all to be more efficient. Her ability to juggle multiple tasks is impressive.”

- “Liam’s time management skills are key to his consistently high productivity levels. His ability to organize work efficiently is an example for all of us to follow.”

Though these positive feedback examples are valuable, it’s important to recognize that there will be instances when your team needs to convey constructive or negative feedback. In the upcoming section, we’ll present 40 examples of constructive peer review feedback. Keep reading!

40 Constructive Peer Review Feedback

Receiving peer review feedback, whether positive or negative, presents a valuable chance for personal and professional development. Let’s explore some examples your team can employ to provide constructive feedback , even in situations where criticism is necessary, with a focus on maintaining a supportive and growth-oriented atmosphere.

Constructive Peer Review Feedback on Work Quality

- “I appreciate John’s meticulous attention to detail, which enhances our projects. However, I noticed a few minor typos in his recent report. To maintain an impeccable standard, I’d suggest dedicating more effort to proofreading.”

- “Sarah’s research is comprehensive, and her insights are invaluable. Nevertheless, for the sake of clarity and brevity, I recommend distilling her conclusions to their most essential points.”

- “Michael’s coding skills are robust, but for the sake of team collaboration, I’d suggest that he provides more detailed comments within the code to enhance readability and consistency.”

- “Emma’s creative design concepts are inspiring, yet consistency in her chosen color schemes across projects could further bolster brand recognition.”

- “David’s analytical skills are thorough and robust, but it might be beneficial to present data in a more reader-friendly format to enhance overall comprehension.”

- “I’ve observed Megan’s solid technical skills, which are highly proficient. To further her growth, I recommend taking on more challenging projects to expand her expertise.”

- “Robert’s industry knowledge is extensive and impressive. To become a more well-rounded professional, I’d suggest he focuses on honing his client relationship and communication skills.”

- “Alice’s project management abilities are impressive, and she’s demonstrated an aptitude for handling complexity. I’d recommend she refines her risk assessment skills to excel further in mitigating potential issues.”

- “Daniel’s presentation skills are excellent, and his reports are consistently informative. Nevertheless, there is room for improvement in terms of interpreting data and distilling it into actionable insights.”

- “Laura’s sales techniques are effective, and she consistently meets her targets. I encourage her to invest time in honing her negotiation skills for even greater success in securing deals and partnerships.”

Peer Review Examples on Leadership Skills

- “I’ve noticed James’s commendable decision-making skills. However, to foster a more inclusive and collaborative environment, I’d suggest he be more open to input from team members during the decision-making process.”

- “Sophia’s delegation is efficient, and her team trusts her leadership. To further inspire the team, I’d suggest she share credit more generously and acknowledge the collective effort.”

- “Nathan’s vision and strategic thinking are clear and commendable. Enhancing his conflict resolution skills is suggested to promote a harmonious work environment and maintain team focus.”

- “Olivia’s accountability is much appreciated. I’d encourage her to strengthen her mentoring approach to develop the team’s potential even further and secure a strong professional legacy.”

- “Ethan’s adaptability is an asset that brings agility to the team. Cultivating a more motivational leadership style is recommended to uplift team morale and foster a dynamic work environment.”

Peer Review Examples on Teamwork and Collaboration

- “Ava’s collaboration is essential to the team’s success. She should consider engaging more actively in group discussions to contribute her valuable insights.”

- “Liam’s teamwork is exemplary, but he could motivate peers further by sharing credit more openly and recognizing their contributions.”

- “Chloe’s flexibility in teamwork is invaluable. To become an even more effective team player, she might invest in honing her active listening skills.”

- “William’s contributions to group projects are consistently valuable. To maximize his impact, I suggest participating in inter-departmental collaborations and fostering cross-functional teamwork.”

- “Zoe’s conflict resolution abilities create a harmonious work environment. Expanding her ability to mediate conflicts and find mutually beneficial solutions is advised to enhance team cohesion.”

- “Noah’s punctuality is an asset to the team. To maintain professionalism consistently, he should adhere to deadlines with unwavering dedication, setting a model example for peers.”

- “Grace’s integrity and ethical standards are admirable. To enhance professionalism further, I’d recommend that she maintain a higher level of discretion in discussing sensitive matters.”

- “Logan’s work ethics are strong, and his commitment is evident. Striving for better communication with colleagues regarding project updates is suggested, ensuring everyone remains well-informed.”

- “Sophie’s reliability is appreciated. Maintaining a high level of attention to confidentiality when handling sensitive information would enhance her professionalism.”

- “Jackson’s organizational skills are top-notch. Upholding professionalism by maintaining a tidy and organized workspace is recommended.”

Peer Review Feedback Examples on Mentoring and Support

- “Aiden provides invaluable mentoring to junior team members. He should consider investing even more time in offering guidance and support to help them navigate their professional journeys effectively.”

- “Harper’s commendable support to peers is noteworthy. She should develop coaching skills to maximize their growth, ensuring their development matches their potential.”

- “Samuel’s patience in teaching is a valuable asset. He should tailor support to individual learning styles to enhance their understanding and retention of key concepts.”

- “Ella’s mentorship plays a pivotal role in the growth of colleagues. She should expand her role in offering guidance for long-term career development, helping them set and achieve their professional goals.”

- “Benjamin’s exceptional helpfulness fosters a more supportive atmosphere where everyone can thrive. He should encourage team members to seek assistance when needed.”

- “Mia’s communication skills are clear and effective. To cater to different audience types, she should use more varied communication channels to convey her message more comprehensively.”

- “Lucas’s ability to articulate ideas is commendable, and his verbal communication is strong. He should polish non-verbal communication to ensure that his body language aligns with his spoken message.”

- “Evelyn’s appreciated active listening skills create strong relationships with colleagues. She should foster stronger negotiation skills for client interactions, ensuring both parties are satisfied with the outcomes.”

- “Jack’s presentation skills are excellent. He should elevate written communication to match the quality of verbal presentations, offering more comprehensive and well-structured documentation.”

- “Avery’s clarity in explaining complex concepts is valued by colleagues. She should develop persuasive communication skills to enhance her ability to secure project proposals and buy-in from stakeholders.”

Feedback on Time Management and Productivity

- “Isabella’s efficient time management skills contribute to the team’s success. She should explore time-tracking tools to further optimize her workflow and maximize her efficiency.”

- “Henry’s remarkable productivity sets a high standard. He should maintain a balanced approach to tasks to prevent burnout and ensure sustainable long-term performance.”

- “Luna’s impressive task prioritization and strategic time allocation should be fine-tuned with goal-setting techniques to ensure consistent productivity aligned with objectives.”

- “Leo’s great deadline adherence is commendable. He should incorporate short breaks into the schedule to enhance productivity and focus, allowing for the consistent meeting of high standards.”

- “Mila’s multitasking abilities are a valuable skill. She should strive to implement regular time-blocking sessions into the daily routine to further enhance time management capabilities.”

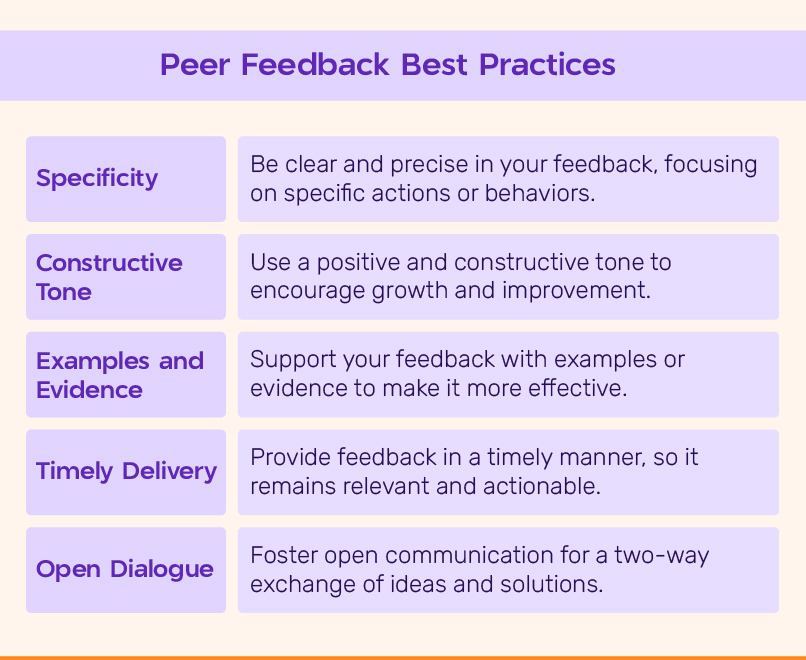

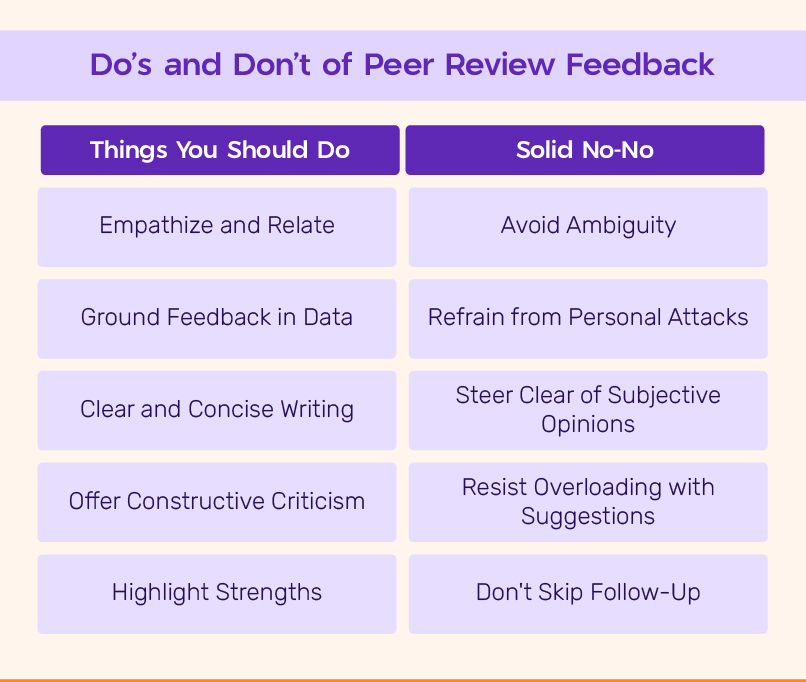

Do’s and Don’t of Peer Review Feedback

Peer review feedback can be extremely helpful for intellectual growth and professional development. Engaging in this process with thoughtfulness and precision can have a profound impact on both the reviewer and the individual seeking feedback.

However, there are certain do’s and don’ts that must be observed to ensure that the feedback is not only constructive but also conducive to a positive and productive learning environment.

The Do’s of Peer Review Feedback:

Empathize and Relate : Put yourself in the shoes of the person receiving the feedback. Recognize the effort and intention behind their work, and frame your comments with sensitivity.

Ground Feedback in Data : Base your feedback on concrete evidence and specific examples from the work being reviewed. This not only adds credibility to your comments but also helps the recipient understand precisely where improvements are needed.

Clear and Concise Writing : Express your thoughts in a clear and straightforward manner. Avoid jargon or ambiguous language that may lead to misinterpretation.

Offer Constructive Criticism : Focus on providing feedback that can guide improvement. Instead of simply pointing out flaws, suggest potential solutions or alternatives.

Highlight Strength s: Acknowledge and commend the strengths in the work. Recognizing what’s done well can motivate the individual to build on their existing skills.

The Don’ts of Peer Review Feedback:

Avoid Ambiguity : Vague or overly general comments such as “It’s not good” do not provide actionable guidance. Be specific in your observations.

Refrain from Personal Attacks : Avoid making the feedback personal or overly critical. Concentrate on the work and its improvement, not on the individual.

Steer Clear of Subjective Opinions : Base your feedback on objective criteria and avoid opinions that may not be universally applicable.

Resist Overloading with Suggestions : While offering suggestions for improvement is important, overwhelming the recipient with a laundry list of changes can be counterproductive.

Don’t Skip Follow-Up : Once you’ve provided feedback, don’t leave the process incomplete. Follow up and engage in a constructive dialogue to ensure that the feedback is understood and applied effectively.

Remember that the art of giving peer review feedback is a valuable skill, and when done right, it can foster professional growth, foster collaboration, and inspire continuous improvement. This is where performance management software like Peoplebox come into play.

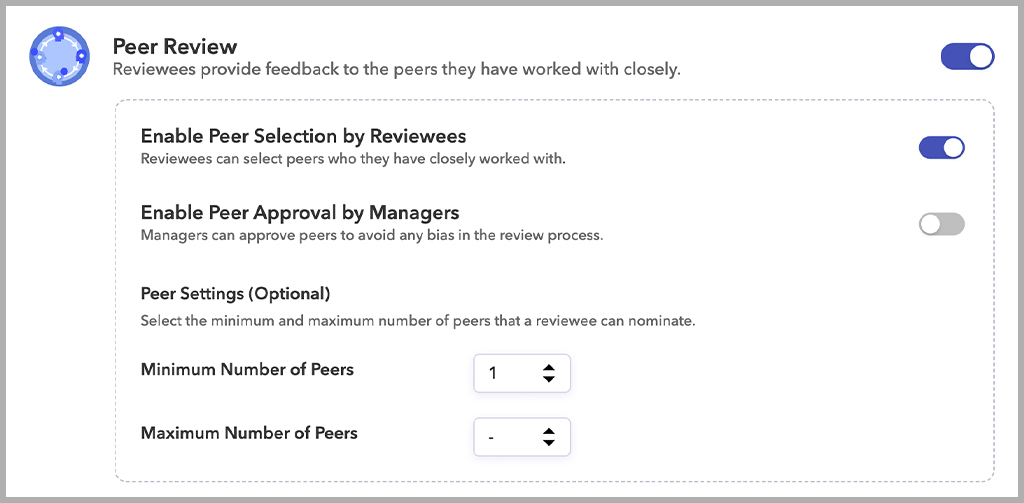

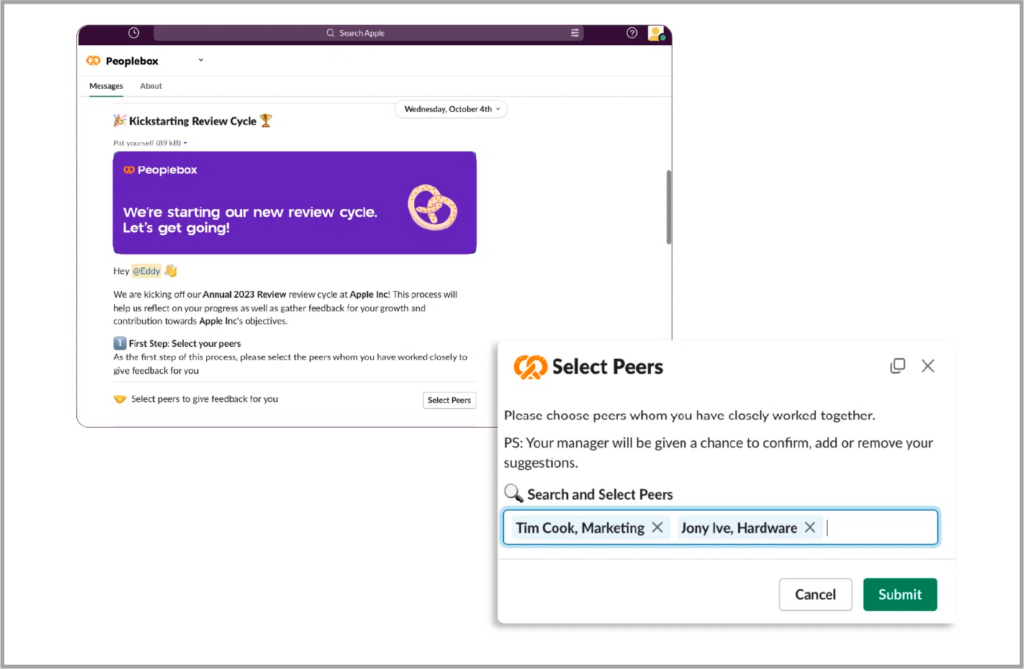

Start Collecting Peer Review Feedback On Peoplebox

In a world where the continuous improvement of your workforce is paramount, harnessing the potential of peer review feedback is a game-changer. Peoplebox offers a suite of powerful features that revolutionize performance management, simplifying the alignment of people with business goals and driving success. Want to experience it first hand? Take a quick tour of our product.

Through Peoplebox, you can effortlessly establish peer reviews, customizing key aspects such as:

- Allowing the reviewee to select their peers

- Seeking managerial approval for chosen peers to mitigate bias

- Determining the number of peers eligible for review, and more.

And the best part? Peoplebox lets you do all this from right within Slack.

Peer Review Feedback Template That You Can Use Right Away

Still on the fence about using software for performance reviews? Here’s a quick ready-to-use peer review template you can use to kickstart the peer review process.

Download the Free Peer Review Feedback Form here.

If you ever reconsider and are looking for a more streamlined approach to handle 360 feedback, give Peoplebox a shot!

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is peer review feedback important.

Peer review feedback provides a well-rounded view of employee performance, fosters skill enhancement, encourages accountability, strengthens team cohesion, ensures fair assessment, and identifies blind spots early on.

How does peer review feedback benefit employees?

Peer review feedback offers employees valuable insights for growth, helps them identify areas for improvement, provides recognition for their efforts, and fosters a culture of collaboration and continuous learning.

What are some best practices for giving constructive peer feedback?

Best practices include grounding feedback in specific examples, offering both praise and areas for improvement, focusing on actionable suggestions, maintaining professionalism, and ensuring feedback is clear and respectful.

What role does HR software like Peoplebox play in peer review feedback?

HR software like Peoplebox streamlines the peer review process by allowing customizable feedback, integration with collaboration tools like Slack, easy selection of reviewers, and providing templates and tools for effective feedback.

How can HR professionals promote a culture of feedback and openness in their organization?

HR professionals can promote a feedback culture by leading by example, providing training on giving and receiving feedback, recognizing and rewarding constructive feedback, creating safe spaces for communication, and fostering a culture of continuous improvement.

What is peer review?

A peer review is a collaborative evaluation process where colleagues assess each other’s work. It’s a cornerstone of professional development, enhancing accountability and shared learning. By providing constructive feedback , peers contribute to overall team improvement. Referencing peer review examples can guide effective implementation within your organization.

What should I write in a peer review?

In a peer review, you should focus on providing constructive, balanced feedback. Highlight strengths such as effective communication or leadership, and offer specific suggestions for improvement. The goal is to help peers grow professionally by addressing areas like skill development or performance gaps. Use clear and supportive language to ensure your feedback is actionable. By incorporating peer review examples, you can provide valuable insights to enhance performance.

What are some examples of peer review phrases?

Statements like ‘ Your ability to articulate complex ideas is impressive ‘ or ‘ I recommend focusing on time management to improve project delivery ‘ are examples of peer review phrases. These phrases help peers identify specific strengths and areas for growth. Customizing feedback to fit the context ensures it’s relevant and actionable. Exploring different peer review examples can inspire you to craft impactful feedback that drives growth.

Why is it called peer review?

It’s called peer review because the evaluation is conducted by colleagues or peers who share similar expertise or roles. This ensures that the feedback is relevant and credible, as it comes from individuals who understand the challenges and standards of the work being assessed. Analyzing peer review examples can reveal best practices for implementing this process effectively.

What are the types of peer reviews?

Peer reviews can be formal or informal. Formal reviews are typically structured, documented, and tied to performance evaluation. Informal reviews offer more frequent, real-time feedback. Both types are valuable for development. Exploring peer review examples can help you determine the best approach for your team or organization.

Table of Contents

What’s Next?

Get Peoplebox Demo

Get a 30-min. personalized demo of our OKR, Performance Management and People Analytics Platform Schedule Now

Take Product Tour

Watch a product tour to see how Peoplebox makes goals alignment, performance management and people analytics seamless. Take a product tour

Subscribe to our blog & newsletter

Popular Categories

- Employee Engagement

- One on Ones

- People Analytics

- Strategy Execution

- Remote Work

Recent Blogs

What are the Best Interview Questions to Ask Candidates?

100+ Best Exit Interview Questions You Should Ask (+ Exit Interview Tips)

15+ Types of Recruitment Methods to Hire the Top Talents

- Performance Reviews

- 360 Degree Reviews

- Performance Reviews in Slack

- 1:1 Meetings

- Business Reviews

- Engagement Survey

- Anonymous Messaging

- Engagement Insights

- Org Chart Tool

- Integrations

- Why Peoplebox

- Our Customers

- Customer Success Stories

- Product Tours

- Peoplebox Analytics Talk

- The Peoplebox Pulse Newsletter

- OKR Podcast

- OKR Examples

- One-on-one-meeting questions

- Performance Review Templates

- Request Demo

- Help Center

- Careers (🚀 We are hiring)

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- GDPR Compliance

- Data Processing Addendum

- Responsible Disclosure

- Cookies Policy

Share this blog

Peer Review Examples (300 Key Positive, Negative Phrases)

By Status.net Editorial Team on February 4, 2024 — 18 minutes to read

Peer review is a process that helps you evaluate your work and that of others. It can be a valuable tool in ensuring the quality and credibility of any project or piece of research. Engaging in peer review lets you take a fresh look at something you may have become familiar with. You’ll provide constructive criticism to your peers and receive the same in return, allowing everyone to learn and grow.

Finding the right words to provide meaningful feedback can be challenging. This article provides positive and negative phrases to help you conduct more effective peer reviews.

Crafting Positive Feedback

Praising professionalism.

- Your punctuality is exceptional.

- You always manage to stay focused under pressure.

- I appreciate your respect for deadlines.

- Your attention to detail is outstanding.

- You exhibit great organizational skills.

- Your dedication to the task at hand is commendable.

- I love your professionalism in handling all situations.

- Your ability to maintain a positive attitude is inspiring.

- Your commitment to the project shows in the results.

- I value your ability to think critically and come up with solutions.

Acknowledging Skills

- Your technical expertise has greatly contributed to our team’s success.

- Your creative problem-solving skills are impressive.

- You have an exceptional way of explaining complex ideas.

- I admire your ability to adapt to change quickly.

- Your presentation skills are top-notch.

- You have a unique flair for motivating others.

- Your negotiation skills have led to wonderful outcomes.

- Your skillful project management ensured smooth progress.

- Your research skills have produced invaluable findings.

- Your knack for diplomacy has fostered great relationships.

Encouraging Teamwork

- Your ability to collaborate effectively is evident.

- You consistently go above and beyond to help your teammates.

- I appreciate your eagerness to support others.

- You always bring out the best in your team members.

- You have a gift for uniting people in pursuit of a goal.

- Your clear communication makes collaboration a breeze.

- You excel in creating a nurturing atmosphere for the team.

- Your leadership qualities are incredibly valuable to our team.

- I admire your respectful attitude towards team members.

- You have a knack for creating a supportive and inclusive environment.

Highlighting Achievements

- Your sales performance this quarter has been phenomenal.

- Your cost-saving initiatives have positively impacted the budget.

- Your customer satisfaction ratings have reached new heights.

- Your successful marketing campaign has driven impressive results.

- You’ve shown a strong improvement in meeting your performance goals.

- Your efforts have led to a significant increase in our online presence.

- The success of the event can be traced back to your careful planning.

- Your project was executed with precision and efficiency.

- Your innovative product ideas have provided a competitive edge.

- You’ve made great strides in strengthening our company culture.

Formulating Constructive Criticism

Addressing areas for improvement.

When providing constructive criticism, try to be specific in your comments and avoid generalizing. Here are 30 example phrases:

- You might consider revising this sentence for clarity.

- This section could benefit from more detailed explanations.

- It appears there may be a discrepancy in your data.

- This paragraph might need more support from the literature.

- I suggest reorganizing this section to improve coherence.

- The introduction can be strengthened by adding context.

- There may be some inconsistencies that need to be resolved.

- This hypothesis needs clearer justification.

- The methodology could benefit from additional details.

- The conclusion may need a stronger synthesis of the findings.

- You might want to consider adding examples to illustrate your point.

- Some of the terminology used here could be clarified.

- It would be helpful to see more information on your sources.

- A summary might help tie this section together.

- You may want to consider rephrasing this question.

- An elaboration on your methods might help the reader understand your approach.

- This image could be clearer if it were larger or had labels.

- Try breaking down this complex idea into smaller parts.

- You may want to revisit your tone to ensure consistency.

- The transitions between topics could be smoother.

- Consider adding citations to support your argument.

- The tables and figures could benefit from clearer explanations.

- It might be helpful to revisit your formatting for better readability.

- This discussion would benefit from additional perspectives.

- You may want to address any logical gaps in your argument.

- The literature review might benefit from a more critical analysis.

- You might want to expand on this point to strengthen your case.

- The presentation of your results could be more organized.

- It would be helpful if you elaborated on this connection in your analysis.

- A more in-depth conclusion may better tie your ideas together.

Offering Specific Recommendations

- You could revise this sentence to say…

- To make this section more detailed, consider discussing…

- To address the data discrepancy, double-check the data at this point.

- You could add citations from these articles to strengthen your point.

- To improve coherence, you could move this paragraph to…

- To add context, consider mentioning…

- To resolve these inconsistencies, check…

- To justify your hypothesis, provide evidence from…

- To add detail to your methodology, describe…

- To synthesize your findings in the conclusion, mention…

- To illustrate your point, consider giving an example of…

- To clarify terminology, you could define…

- To provide more information on sources, list…

- To create a summary, touch upon these key points.

- To rephrase this question, try asking…

- To expand upon your methods, discuss…

- To make this image clearer, increase its size or add labels for…

- To break down this complex idea, consider explaining each part like…

- To maintain a consistent tone, avoid using…

- To smooth transitions between topics, use phrases such as…

- To support your argument, cite sources like…

- To explain tables and figures, add captions with…

- To improve readability, use formatting elements like headings, bullet points, etc.

- To include additional perspectives in your discussion, mention…

- To address logical gaps, provide reasoning for…

- To create a more critical analysis in your literature review, critique…

- To expand on this point, add details about…

- To present your results more organized, use subheadings, tables, or graphs.

- To elaborate on connections in your analysis, show how x relates to y by…

- To provide a more in-depth conclusion, tie together the major findings by…

Highlighting Positive Aspects

When offering constructive criticism, maintaining a friendly and positive tone is important. Encourage improvement by highlighting the positive aspects of the work. For example:

- Great job on this section!

- Your writing is clear and easy to follow.

- I appreciate your attention to detail.

- Your conclusions are well supported by your research.

- Your argument is compelling and engaging.

- I found your analysis to be insightful.

- The organization of your paper is well thought out.

- Your use of citations effectively strengthens your claims.

- Your methodology is well explained and thorough.

- I’m impressed with the depth of your literature review.

- Your examples are relevant and informative.

- You’ve made excellent connections throughout your analysis.

- Your grasp of the subject matter is impressive.

- The clarity of your images and figures is commendable.

- Your transitions between topics are smooth and well-executed.

- You’ve effectively communicated complex ideas.

- Your writing style is engaging and appropriate for your target audience.

- Your presentation of results is easy to understand.

- Your tone is consistent and professional.

- Your overall argument is persuasive.

- Your use of formatting helps guide the reader.

- Your tables, graphs, and illustrations enhance your argument.

- Your interpretation of the data is insightful and well-reasoned.

- Your discussion is balanced and well-rounded.

- The connections you make throughout your paper are thought-provoking.

- Your approach to the topic is fresh and innovative.

- You’ve done a fantastic job synthesizing information from various sources.

- Your attention to the needs of the reader is commendable.

- The care you’ve taken in addressing counterarguments is impressive.

- Your conclusions are well-drawn and thought-provoking.

Balancing Feedback

Combining positive and negative remarks.

When providing peer review feedback, it’s important to balance positive and negative comments: this approach allows the reviewer to maintain a friendly tone and helps the recipient feel reassured.

Examples of Positive Remarks:

- Well-organized

- Clear and concise

- Excellent use of examples

- Thorough research

- Articulate argument

- Engaging writing style

- Thoughtful analysis

- Strong grasp of the topic

- Relevant citations

- Logical structure

- Smooth transitions

- Compelling conclusion

- Original ideas

- Solid supporting evidence

- Succinct summary

Examples of Negative Remarks:

- Unclear thesis

- Lacks focus

- Insufficient evidence

- Overgeneralization

- Inconsistent argument

- Redundant phrasing

- Jargon-filled language

- Poor formatting

- Grammatical errors

- Unconvincing argument

- Confusing organization

- Needs more examples

- Weak citations

- Unsupported claims

- Ambiguous phrasing

Ensuring Objectivity

Avoid using emotionally charged language or personal opinions. Instead, base your feedback on facts and evidence.

For example, instead of saying, “I don’t like your choice of examples,” you could say, “Including more diverse examples would strengthen your argument.”

Personalizing Feedback

Tailor your feedback to the individual and their work, avoiding generic or blanket statements. Acknowledge the writer’s strengths and demonstrate an understanding of their perspective. Providing personalized, specific, and constructive comments will enable the recipient to grow and improve their work.

For instance, you might say, “Your writing style is engaging, but consider adding more examples to support your points,” or “I appreciate your thorough research, but be mindful of avoiding overgeneralizations.”

Phrases for Positive Feedback

- Great job on the presentation, your research was comprehensive.

- I appreciate your attention to detail in this project.

- You showed excellent teamwork and communication skills.

- Impressive progress on the task, keep it up!

- Your creativity really shined in this project.

- Thank you for your hard work and dedication.

- Your problem-solving skills were crucial to the success of this task.

- I am impressed by your ability to multitask.

- Your time management in finishing this project was stellar.

- Excellent initiative in solving the issue.

- Your work showcases your exceptional analytical skills.

- Your positive attitude is contagious!

- You were successful in making a complex subject easier to grasp.

- Your collaboration skills truly enhanced our team’s effectiveness.

- You handled the pressure and deadlines admirably.

- Your written communication is both thorough and concise.

- Your responsiveness to feedback is commendable.

- Your flexibility in adapting to new challenges is impressive.

- Thank you for your consistently accurate work.

- Your devotion to professional development is inspiring.

- You display strong leadership qualities.

- You demonstrate empathy and understanding in handling conflicts.

- Your active listening skills contribute greatly to our discussions.

- You consistently take ownership of your tasks.

- Your resourcefulness was key in overcoming obstacles.

- You consistently display a can-do attitude.

- Your presentation skills are top-notch!

- You are a valuable asset to our team.

- Your positive energy boosts team morale.

- Your work displays your tremendous growth in this area.

- Your ability to stay organized is commendable.

- You consistently meet or exceed expectations.

- Your commitment to self-improvement is truly inspiring.

- Your persistence in tackling challenges is admirable.

- Your ability to grasp new concepts quickly is impressive.

- Your critical thinking skills are a valuable contribution to our team.

- You demonstrate impressive technical expertise in your work.

- Your contributions make a noticeable difference.

- You effectively balance multiple priorities.

- You consistently take the initiative to improve our processes.

- Your ability to mentor and support others is commendable.

- You are perceptive and insightful in offering solutions to problems.

- You actively engage in discussions and share your opinions constructively.

- Your professionalism is a model for others.

- Your ability to quickly adapt to changes is commendable.

- Your work exemplifies your passion for excellence.

- Your desire to learn and grow is inspirational.

- Your excellent organizational skills are a valuable asset.

- You actively seek opportunities to contribute to the team’s success.

- Your willingness to help others is truly appreciated.

- Your presentation was both informative and engaging.

- You exhibit great patience and perseverance in your work.

- Your ability to navigate complex situations is impressive.

- Your strategic thinking has contributed to our success.

- Your accountability in your work is commendable.

- Your ability to motivate others is admirable.

- Your reliability has contributed significantly to the team’s success.

- Your enthusiasm for your work is contagious.

- Your diplomatic approach to resolving conflict is commendable.

- Your ability to persevere despite setbacks is truly inspiring.

- Your ability to build strong relationships with clients is impressive.

- Your ability to prioritize tasks is invaluable to our team.

- Your work consistently demonstrates your commitment to quality.

- Your ability to break down complex information is excellent.

- Your ability to think on your feet is greatly appreciated.

- You consistently go above and beyond your job responsibilities.

- Your attention to detail consistently ensures the accuracy of your work.

- Your commitment to our team’s success is truly inspiring.

- Your ability to maintain composure under stress is commendable.

- Your contributions have made our project a success.

- Your confidence and conviction in your work is motivating.

- Thank you for stepping up and taking the lead on this task.

- Your willingness to learn from mistakes is encouraging.

- Your decision-making skills contribute greatly to the success of our team.

- Your communication skills are essential for our team’s effectiveness.

- Your ability to juggle multiple tasks simultaneously is impressive.

- Your passion for your work is infectious.

- Your courage in addressing challenges head-on is remarkable.

- Your ability to prioritize tasks and manage your own workload is commendable.

- You consistently demonstrate strong problem-solving skills.

- Your work reflects your dedication to continuous improvement.

- Your sense of humor helps lighten the mood during stressful times.

- Your ability to take constructive feedback on board is impressive.

- You always find opportunities to learn and develop your skills.

- Your attention to safety protocols is much appreciated.

- Your respect for deadlines is commendable.

- Your focused approach to work is motivating to others.

- You always search for ways to optimize our processes.

- Your commitment to maintaining a high standard of work is inspirational.

- Your excellent customer service skills are a true asset.

- You demonstrate strong initiative in finding solutions to problems.

- Your adaptability to new situations is an inspiration.

- Your ability to manage change effectively is commendable.

- Your proactive communication is appreciated by the entire team.

- Your drive for continuous improvement is infectious.

- Your input consistently elevates the quality of our discussions.

- Your ability to handle both big picture and detailed tasks is impressive.

- Your integrity and honesty are commendable.

- Your ability to take on new responsibilities is truly inspiring.

- Your strong work ethic is setting a high standard for the entire team.

Phrases for Areas of Improvement

- You might consider revisiting the structure of your argument.

- You could work on clarifying your main point.

- Your presentation would benefit from additional examples.

- Perhaps try exploring alternative perspectives.

- It would be helpful to provide more context for your readers.

- You may want to focus on improving the flow of your writing.

- Consider incorporating additional evidence to support your claims.

- You could benefit from refining your writing style.

- It would be useful to address potential counterarguments.

- You might want to elaborate on your conclusion.

- Perhaps consider revisiting your methodology.

- Consider providing a more in-depth analysis.

- You may want to strengthen your introduction.

- Your paper could benefit from additional proofreading.

- You could work on making your topic more accessible to your readers.

- Consider tightening your focus on key points.

- It might be helpful to add more visual aids to your presentation.

- You could strive for more cohesion between your sections.

- Your abstract would benefit from a more concise summary.

- Perhaps try to engage your audience more actively.

- You may want to improve the organization of your thoughts.

- It would be useful to cite more reputable sources.

- Consider emphasizing the relevance of your topic.

- Your argument could benefit from stronger parallels.

- You may want to add transitional phrases for improved readability.

- It might be helpful to provide more concrete examples.

- You could work on maintaining a consistent tone throughout.

- Consider employing a more dynamic vocabulary.

- Your project would benefit from a clearer roadmap.

- Perhaps explore the limitations of your study.

- It would be helpful to demonstrate the impact of your research.

- You could work on the consistency of your formatting.

- Consider refining your choice of images.

- You may want to improve the pacing of your presentation.

- Make an effort to maintain eye contact with your audience.

- Perhaps adding humor or anecdotes would engage your listeners.

- You could work on modulating your voice for emphasis.

- It would be helpful to practice your timing.

- Consider incorporating more interactive elements.

- You might want to speak more slowly and clearly.

- Your project could benefit from additional feedback from experts.

- You might want to consider the practical implications of your findings.

- It would be useful to provide a more user-friendly interface.

- Consider incorporating a more diverse range of sources.

- You may want to hone your presentation to a specific audience.

- You could work on the visual design of your slides.

- Your writing might benefit from improved grammatical accuracy.

- It would be helpful to reduce jargon for clarity.

- You might consider refining your data visualization.

- Perhaps provide a summary of key points for easier comprehension.

- You may want to develop your skills in a particular area.

- Consider attending workshops or trainings for continued learning.

- Your project could benefit from stronger collaboration.

- It might be helpful to seek guidance from mentors or experts.

- You could work on managing your time more effectively.

- It would be useful to set goals and priorities for improvement.

- You might want to identify areas where you can grow professionally.

- Consider setting aside time for reflection and self-assessment.

- Perhaps develop strategies for overcoming challenges.

- You could work on increasing your confidence in public speaking.

- Consider collaborating with others for fresh insights.

- You may want to practice active listening during discussions.

- Be open to feedback and constructive criticism.

- It might be helpful to develop empathy for team members’ perspectives.

- You could work on being more adaptable to change.

- It would be useful to improve your problem-solving abilities.

- Perhaps explore opportunities for networking and engagement.

- You may want to set personal benchmarks for success.

- You might benefit from being more proactive in seeking opportunities.

- Consider refining your negotiation and persuasion skills.

- It would be helpful to enhance your interpersonal communication.

- You could work on being more organized and detail-oriented.

- You may want to focus on strengthening leadership qualities.

- Consider improving your ability to work effectively under pressure.

- Encourage open dialogue among colleagues to promote a positive work environment.

- It might be useful to develop a growth mindset.

- Be open to trying new approaches and techniques.

- Consider building stronger relationships with colleagues and peers.

- It would be helpful to manage expectations more effectively.

- You might want to delegate tasks more efficiently.

- You could work on your ability to prioritize workload effectively.

- It would be useful to review and update processes and procedures regularly.

- Consider creating a more inclusive working environment.

- You might want to seek opportunities to mentor and support others.

- Recognize and celebrate the accomplishments of your team members.

- Consider developing a more strategic approach to decision-making.

- You may want to establish clear goals and objectives for your team.

- It would be helpful to provide regular and timely feedback.

- Consider enhancing your delegation and time-management skills.

- Be open to learning from your team’s diverse skill sets.

- You could work on cultivating a collaborative culture.

- It would be useful to engage in continuous professional development.

- Consider seeking regular feedback from colleagues and peers.

- You may want to nurture your own personal resilience.

- Reflect on areas of improvement and develop an action plan.

- It might be helpful to share your progress with a mentor or accountability partner.

- Encourage your team to support one another’s growth and development.

- Consider celebrating and acknowledging small successes.

- You could work on cultivating effective communication habits.

- Be willing to take calculated risks and learn from any setbacks.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can i phrase constructive feedback in peer evaluations.

To give constructive feedback in peer evaluations, try focusing on specific actions or behaviors that can be improved. Use phrases like “I noticed that…” or “You might consider…” to gently introduce your observations. For example, “You might consider asking for help when handling multiple tasks to improve time management.”

What are some examples of positive comments in peer reviews?

- “Your presentation was engaging and well-organized, making it easy for the team to understand.”

- “You are a great team player, always willing to help others and contribute to the project’s success.”

- “Your attention to detail in documentation has made it easier for the whole team to access information quickly.”

Can you suggest ways to highlight strengths in peer appraisals?

Highlighting strengths in peer appraisals can be done by mentioning specific examples of how the individual excelled or went above and beyond expectations. You can also point out how their strengths positively impacted the team. For instance:

- “Your effective communication skills ensured that everyone was on the same page during the project.”

- “Your creativity in problem-solving helped resolve a complex issue that benefited the entire team.”

What are helpful phrases to use when noting areas for improvement in a peer review?

When noting areas for improvement in a peer review, try using phrases that encourage growth and development. Some examples include:

- “To enhance your time management skills, you might try prioritizing tasks or setting deadlines.”

- “By seeking feedback more often, you can continue to grow and improve in your role.”

- “Consider collaborating more with team members to benefit from their perspectives and expertise.”

How should I approach writing a peer review for a manager differently?

When writing a peer review for a manager, it’s important to focus on their leadership qualities and how they can better support their team. Some suggestions might include:

- “Encouraging more open communication can help create a more collaborative team environment.”

- “By providing clearer expectations or deadlines, you can help reduce confusion and promote productivity.”

- “Consider offering recognition to team members for their hard work, as this can boost motivation and morale.”

What is a diplomatic way to discuss negative aspects in a peer review?

Discussing negative aspects in a peer review requires tact and empathy. Try focusing on behaviors and actions rather than personal attributes, and use phrases that suggest areas for growth. For example:

- “While your dedication to the project is admirable, it might be beneficial to delegate some tasks to avoid burnout.”

- “Improving communication with colleagues can lead to better alignment within the team.”

- “By asking for feedback, you can identify potential blind spots and continue to grow professionally.”

- Flexibility: 25 Performance Review Phrases Examples

- Job Knowledge Performance Review Phrases (Examples)

- Integrity: 25 Performance Review Phrases Examples

- 60 Smart Examples: Positive Feedback for Manager in a Review

- 30 Employee Feedback Examples (Positive & Negative)

- Initiative: 25 Performance Review Phrases Examples

Practical Peer Review Feedback Examples

As part of a team or organization, giving feedback is an integral part of providing constructive criticism and fostering a culture of growth and development. However, giving and receiving feedback can be daunting, especially when it involves discussing areas of improvement with peers or colleagues. In this blog, we will provide practical tips on how to provide effective peer review feedback, as well as valuable insights into delivering meaningful and constructive conversations using real-life examples.

Advice on Peer Feedback

There are a few common areas people flub when giving feedback to a peer or colleague. Let's go over these first to set some basic, best-practice ground rules.

Be Specific

Being specific when giving feedback is essential because it provides clarity and enables the recipient to understand exactly what aspects of their performance or behavior need improvement or reinforcement. Try to leave little room for ambiguity. Specific feedback should allow the person to focus their effort.

Concise feedback is almost always better. Be clear and don't dilute the point with extraneous information or softening. Concentrate the feedback on the most critical aspects that need attention. Be respectful of their time by only delivering the most succinct and targeted info.

Timely feedback is based on recent events or observations. This keeps the details top of mind for both parties. Delivering constructive feedback promptly ensures that it is still relevant and applicable, gives ample time for course correction, and can prevent any necessary escalation. Delivering positive feedback promptly can create a powerful connection between those actions and the desired outcome. Remember, feedback ages like milk.

Acknowledge Strengths

Peer review feedback, in particular, should be delivered tastefully. Generally, you're not in a position to tell the other party what they must do or who they need to be as an employee; instead, you're in a position of suggesting change based on observation. Acknowledging someones key strengths whilst delivering feedback shows you have a balanced perspective on their work. It helps create a constructive atmosphere with trust and psychological safety, which generally makes individuals more receptive to feedback.

Practice Empathy

Use "I" statements to take ownership of your perspective and to avoid sounding accusatory. Be sure to engage in active listening regarding feedback. Above all, put yourself in their shoes. Consider their perspective and reflect on how the might feel receiving the feedback. This will help you approach the conversation with the proper mindset.

DON'T Make it Personal

It should go without saying, but do not make it personal by attacking the other person or their character. Instead, focus on the work that was done and give specific and concise examples. Events and emotions outside of the professional environment should not make their way into the conversation.

DON'T Make Assumptions

It is important not to make assumptions when giving feedback to your peers. Avoid any assumptions without direct observation. It is better to stick with what you have seen and heard directly in order to give helpful feedback.

DON'T Share with Others

It is important to keep peer feedback confidential. That means not discussing it with other people unless you've agreed with your peer to do so. Trust is a key fundamental precursor for delivering and receiving feedback. Don't lose trust by sharing feedback outside of the appropriate bounds.

Examples of Peer Feedback

Applicable examples are always a bit tough. Feedback is almost entirely dependent on the person and situation. Nevertheless, here are some examples of feedback that represent the above best practices:

- "Hey Taylor, thanks for all of the great insights in today's meeting. I always appreciate your subject matter expertise and passion... I feel like that excitement gets the best of you at times. Today, I noticed that you cut off Amber and Jess while they were still speaking. I'm worried it can hinder the free flow of collaboration within the team. In the spirit of constant improvement, I decided it was worth a mention."