United States Declaration of Independence Definition Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Declaration of Independence is a document that is most treasured in United State since it announced independence to American colonies which were at war with Great Britain. It was drafted by Thomas Jefferson back in July 1776 and contained formal explanation of the reason why the Congress had declared independence from Great Britain.

Therefore, the document marked the independence of the thirteen colonies of America, a condition which had caused revolutionary war. America celebrates its day of independence on 4 th July, the day when the congress approved the Declaration for Independence (Becker, 2008). With that background in mind, this essay shall give an analysis of the key issues closely linked to the United States Declaration of Independence.

As highlighted in the introductory part, there was the revolutionary war in the thirteen American colonies before the declaration for independence that had been going on for about a year. Immediately after the end of the Seven Years War, the relationship between American colonies and their mother country started to deteriorate. In addition, some acts which were established in order to increase tax revenue from the colonies ended up creating a tax dispute between the colonies and the Government (Fradin, 2006).

The main reason why the Declaration for Independence was written was to declare the convictions of Americans especially towards their rights. The main aim was to declare the necessity for independence especially to the colonist as well as to state their view and position on the purpose of the government. In addition, apart from making their grievances known to King George III, they also wanted to influence other foreigners like the France to support them in their struggle towards independence.

Most authors and historians believe that the main influence of Jefferson was the English Declaration of Rights that marked the end King James II Reign. As much as the influence of John Locke who was a political theorist from England is questioned, it is clear that he influenced the American Revolution a great deal. Although most historians criticize the Jefferson’s influence by some authors like Charles Hutcheson, it is clear that the philosophical content of the Declaration emanates from other philosophical writings.

The self evident truths in the Declaration for Independence is that all men are created equal and do also have some rights which ought not to be with held at all costs. In addition, the document also illustrated that government is formed for the sole purpose of protecting those rights as it is formed by the people who it governs. Finally, if the government losses the consent, it then qualifies to be either replaced or abolished. Such truths are not only mandatory but they do not require any further emphasis.

Therefore, being self evident means that each truth speaks on its own behalf and should not be denied at whichever circumstances (Zuckert, 1987). The main reason why they were named as self evident was to influence the colonists to see the reality in the whole issue. Jefferson based his argument from on the theory of natural rights as illustrated by John Locke who argued that people have got rights which are not influenced by laws in the society (Tuckness, 2010).

One of the truths in the Declaration for Independence is the inalienable rights which are either individual or collective. Such rights are inclusive of right to liberty, life and pursuit of happiness. Unalienable rights means rights which cannot be denied since they are given by God. In addition, such rights cannot even be sold or lost at whichever circumstance. Apart from individual rights, there are also collective rights like the right of people to chose the right government and also to abolish it incase it fails achieve its main goal.

The inalienable goals are based on the law of nature as well as on the nature’s God as illustrated in the John Locke’s philosophy. It is upon the government to recognize that individuals are entitled to unalienable rights which are bestowed by God. Although the rights are not established by the civil government, it has a great role to ensure that people are able to express such laws in the constitution (Morgan, 2010).

Explaining the purpose of the government was the major intent of the Declaration for Independent. The document explains explicitly that the main purpose is not only to secure but also to protect the rights of the people from individual and life events that threaten them. However, it is important to note that the government gets its power from the people it rules or governs.

The purpose of the government of protecting the God given rights of the people impacts the decision making process in several ways. To begin with, the government has to consider the views of the people before making major decisions failure to which it may be considered unworthy and be replaced. Therefore, the decision making process becomes quite complex as several positions must be taken in to consideration.

The declaration identifies clearly the conditions under which the government can be abolished or replaced. For example, studies of Revolutionary War and Beyond, states that “any form of government becomes destructive of these ends; it is the right of the people, to alter or abolish it and institute a new government” (par. 62010). Therefore, document illustrated that the colonists were justified to reject or abolish the British rule.

The declaration was very significant especially due to the fact that it illustrated explicitly the conditions which were present in America by the time it was being made. For example, one of the key grievances of the thirteen colonies was concerning the issue of slave trade. The issue of abolishing slavery was put in the first draft of the declaration for independent although it was scrapped off later since the southern states were against the abolishment of slave trade.

Another issue which was illustrated in the declaration was the fact that the king denied the colonists the power to elect their representatives in the legislatures. While the colonists believed that they had the right to choose the government to govern them, in the British government, it was the duty of the King to do so.

Attaining land and migrating to America was the right of colonists to liberty and since the King had made it extremely difficult for the colonists to do so; the Declaration was very significant in addressing such grievances. There are many more problems that were present that were addressed by the Declaration as it was its purpose to do so.

Becker, C. L. (2008). The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas. Illinois: BiblioBazaar, LLC .

Fradin, D. B. (2006). The Declaration of Independence. New York : Marshall Cavendish.

Morgan, K. L. (2010). The Declaration of Independence, Equality and Unalienable Rights . Web.

Revolutionary War and Beyond. (2010). The Purpose of the Declaration of Independence . Web.

Tuckness, A. (2010). Locke’s Political Philosophy . Web.

Zuckert, M. P. (1987). Self-Evident Truth and the Declaration of Independence. The Review of Politics , 49 (3), 319-339.

- How Did Religion Affect the Pattern of Colonization in America and Life in Those Colonies?

- The stock market crash of 1929

- The Declaration of Independence: The Three Copies and Drafts, and Their Relation to Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense”

- Thomas Jefferson’s Personal Life

- Thomas Jefferson’s Legacy in American Memory

- The Concept of Reconstruction

- U.S. Civil Rights Protests of the Middle 20th Century

- Battle of Blair Mountain

- History and Heritage in Determining Present and Future

- Jamestown Rediscovery Artifacts: What Archeology Can Tell Us

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, July 18). United States Declaration of Independence. https://ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence/

"United States Declaration of Independence." IvyPanda , 18 July 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'United States Declaration of Independence'. 18 July.

IvyPanda . 2018. "United States Declaration of Independence." July 18, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence/.

1. IvyPanda . "United States Declaration of Independence." July 18, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "United States Declaration of Independence." July 18, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/declaration-of-independence/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

- Utility Menu

Text of the Declaration of Independence

Note: The source for this transcription is the first printing of the Declaration of Independence, the broadside produced by John Dunlap on the night of July 4, 1776. Nearly every printed or manuscript edition of the Declaration of Independence has slight differences in punctuation, capitalization, and even wording. To find out more about the diverse textual tradition of the Declaration, check out our Which Version is This, and Why Does it Matter? resource.

WHEN in the Course of human Events, it becomes necessary for one People to dissolve the Political Bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the Powers of the Earth, the separate and equal Station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the Separation. We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness—-That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its Foundation on such Principles, and organizing its Powers in such Form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient Causes; and accordingly all Experience hath shewn, that Mankind are more disposed to suffer, while Evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the Forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a Design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future Security. Such has been the patient Sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the Necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The History of the present King of Great-Britain is a History of repeated Injuries and Usurpations, all having in direct Object the Establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid World. He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public Good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing Importance, unless suspended in their Operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. He has refused to pass other Laws for the Accommodation of large Districts of People, unless those People would relinquish the Right of Representation in the Legislature, a Right inestimable to them, and formidable to Tyrants only. He has called together Legislative Bodies at Places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the Depository of their public Records, for the sole Purpose of fatiguing them into Compliance with his Measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly Firmness his Invasions on the Rights of the People. He has refused for a long Time, after such Dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the Dangers of Invasion from without, and Convulsions within. He has endeavoured to prevent the Population of these States; for that Purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their Migrations hither, and raising the Conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the Tenure of their Offices, and the Amount and Payment of their Salaries. He has erected a Multitude of new Offices, and sent hither Swarms of Officers to harrass our People, and eat out their Substance. He has kept among us, in Times of Peace, Standing Armies, without the consent of our Legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a Jurisdiction foreign to our Constitution, and unacknowledged by our Laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large Bodies of Armed Troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from Punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all Parts of the World: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us, in many Cases, of the Benefits of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended Offences: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an arbitrary Government, and enlarging its Boundaries, so as to render it at once an Example and fit Instrument for introducing the same absolute Rule into these Colonies: For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with Power to legislate for us in all Cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our Seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our Towns, and destroyed the Lives of our People. He is, at this Time, transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the Works of Death, Desolation, and Tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty and Perfidy, scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous Ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized Nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the Executioners of their Friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic Insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the Inhabitants of our Frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known Rule of Warfare, is an undistinguished Destruction, of all Ages, Sexes and Conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions we have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble Terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated Injury. A Prince, whose Character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the Ruler of a free People. Nor have we been wanting in Attentions to our British Brethren. We have warned them from Time to Time of Attempts by their Legislature to extend an unwarrantable Jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the Circumstances of our Emigration and Settlement here. We have appealed to their native Justice and Magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the Ties of our common Kindred to disavow these Usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our Connections and Correspondence. They too have been deaf to the Voice of Justice and of Consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the Necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of Mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace, Friends. We, therefore, the Representatives of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the World for the Rectitude of our Intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly Publish and Declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be, Free and Independent States; that they are absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political Connection between them and the State of Great-Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm Reliance on the Protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

Signed by Order and in Behalf of the Congress, JOHN HANCOCK, President.

Attest. CHARLES THOMSON, Secretary.

Library of Congress

Exhibitions.

- Ask a Librarian

- Digital Collections

- Library Catalogs

Creating the United States Creating the Declaration of Independence

Index: all documents, rough draft of the declaration of independence.

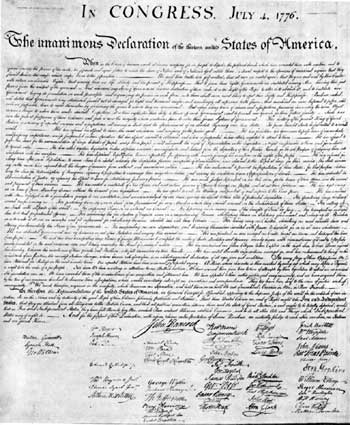

The Declaration of Independence, drafted by Thomas Jefferson and heavily amended by the Continental Congress, boldly asserted humanity's right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness as well as the American colonies' right to revolt against an oppressive British government. Jefferson's "original Rough draught" illustrates Jefferson's literary flair and records key changes made by Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and the Continental Congress before its July 4, 1776, adoption.

Author: Thomas Jefferson Title: Rough Draft of the Declaration of Independence Medium: Manuscript Date: June–July 1776 Collection: Thomas Jefferson Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Draft Virginia Constitution, 1776

In May 1776, Thomas Jefferson, a Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress, wrote at least three drafts of a Virginia constitution. Jefferson's litany of British governmental abuses in his drafts of the Virginia Constitution became his "train of abuses" in the Declaration of Independence.

Author: Thomas Jefferson Title: Draft Virginia Constitution Medium: Manuscript Date: May 1776 Collection: Thomas Jefferson Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Virginia Declaration of Rights, 1776

A call for American independence from Britain, the Virginia Declaration of Rights was drafted by George Mason in May 1776 and amended by Thomas Ludwell Lee (1730–1778) and the Virginia Convention. It was adopted by the Virginia Convention on June 12, 1776. Thomas Jefferson borrowed many ideas and phrases from the Virginia document when he drafted the Declaration of Independence a few weeks later. The Virginia Declaration of Rights has also been heralded as a model for the first ten amendments to the federal Constitution, the amendments known as the "Bill of Rights."

Author: George Mason with amendments by Thomas Ludwell Lee Title: Virginia Declaration of Rights Medium: Manuscript Date: May 1776 Collection: George Mason Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Common Sense, 1776

In January 1776, Thomas Paine (1737–1809) penned his famous pamphlet Common Sense , in which he urged the American Colonies to declare independence and immediately sever all ties with the British monarchy. With its strong arguments against monarchy, Common Sense paved the way for the Declaration of Independence more than any other single publication. Paine suggested a form of government to replace the British colonial system: a one-house legislature for each colony that would be subordinate to a one-house continental congress with no executive power at either level.

Author: Thomas Paine Title: Common Sense. . . . City: Philadelphia Publisher: R. Bell Date: 1776 Collection: Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms, 1775

The Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking up Arms puts forth the reasons for America's rebellion that were raised in the 1775 congressional declaration. Although the final manifesto stressed a hope for the restoration of peace, Thomas Jefferson's draft was a "Spirited Manifesto," according to John Adams (1735–1826). The spirited and creative qualities of Jefferson's writing helped secure his selection as chair of the committee to draft the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

Author: Thomas Jefferson Title: Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms Medium: Manuscript Date: 1775 Collection: Thomas Jefferson Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

A Summary View of the Rights of British America, 1774

Thomas Jefferson's A Summary View of the Rights of British America declared America's right to rebel against an oppressive and despotic government and heralded the arrival of an independent America. Jefferson's pamphlet was originally drafted as instruction for Virginia's delegates to the Continental Congress in 1774.

Author: Thomas Jefferson Title: A Summary View of the Rights of British America City: Williamsburg: Publisher: Clementina Rind Date: 1774 Collection: Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

Fairfax County Resolves, 1774

The Fairfax County Resolves, written by George Mason (1725–1792) and George Washington (1731/32–1799) and presented on July 17, 1774, was the first clear statement of fundamental constitutional rights of the British American colonies as subjects of the British Crown. Adopted the next day by the Fairfax County Convention, which met to protest British retaliations against Massachusetts after the Boston Tea Party, the resolves call for a "firm Union" of the colonies because an injury against one colony is "aimed at all."

Author: George Mason and George Washington Title: Fairfax County Resolves Medium: Manuscript Date: July 17, 1774 Collection: George Washington Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved, 1764

The incongruity of arguing for their own freedom and liberty while enslaving others was openly discussed by American revolutionaries during the period leading up to the writing of the Declaration of Independence and beyond. In his most famous pamphlet, The Rights of British Colonists Asserted and Proved , James Otis (1725–1783) asserted that the slave trade is "the most shocking violation of the law of nature." He also stated that "It is a clear truth, that those who every day barter away other men's liberty will soon care little for their own."

Author: James Otis Title: Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved City: Boston Publisher: Edes and Gill Date: 1764 Collection: Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

Essays on the Principles of Morality and Natural Religion, 1751

When Thomas Jefferson asserted the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness in the Declaration of Independence, he was influenced by the writings of Henry Home, Lord Kames (1696–1782). Kames was a Scottish moral philosopher who argued for the right to "the pursuit of happiness" in his acclaimed work Essays on the Principles of Morality and Natural Religion . Jefferson owned and annotated this copy.

Author: Henry Home, Lord Kames Title: Essays on the Principles of Morality and Natural Religion, in Two Parts City: Edinburgh Date: 1751 Collection: Thomas Jefferson Library, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

Two Treatises of Government, 1690

The works of John Locke (1632–1704), well-known English political philosopher, provided many Americans with the philosophical arguments for inalienable natural rights, principally those of property and of rebellion against abusive governments. In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson did not incorporate Locke's emphasis in his "Second Treatise of Government" on the right to property but gave the right to rebel a prominent place.

Author: John Locke Title: Two Treatises of Government City: London City: Awnsham Churchill Date: 1690 Collection: Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress

First Printed Version of the Declaration of Independence, 1776

Congress approved the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, and directed that it be printed by John Dunlap. This only surviving fragment of the Declaration broadside printed by Dunlap was sent on July 6, 1776, to George Washington by John Hancock, President of the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. General Washington had this Declaration read to his assembled troops on July 9 in New York, where they awaited the combined British fleet and army.

Author: Thomas Jefferson Title: Declaration of Independence City: Philadelphia Publisher: John Dunlap Date: July 4, 1776 Collection: George Washington Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress

Connect with the Library

All ways to connect

Subscribe & Comment

- RSS & E-Mail

Download & Play

- iTunesU (external link)

About | Press | Jobs | Donate Inspector General | Legal | Accessibility | External Link Disclaimer | USA.gov

Home — Essay Samples — History — Declaration of Independence — My Declaration of Independence

My Declaration of Independence

- Categories: Declaration of Independence

About this sample

Words: 720 |

Published: Jun 13, 2024

Words: 720 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, personal autonomy, intellectual freedom, emotional self-reliance.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: History

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 394 words

3 pages / 1356 words

1 pages / 570 words

2 pages / 1154 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence, a foundational document in American history, serves as a beacon of freedom and democracy. This essay delves into the historical context surrounding the Declaration and explores how it was [...]

The Declaration of Independence, adopted on July 4, 1776, is a cornerstone document in American history, symbolizing the colonies' struggle for freedom and justice. It eloquently articulates the principles of individual liberty [...]

The Declaration of Independence is one of the most important documents in American history. Drafted by Thomas Jefferson and adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, it formally announced the thirteen American [...]

"Declaration of Independence." History.com, A&E Television Networks, 2021, www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/declaration-of-independence. Accessed 28 July 2021. Paine, [...]

Introduction to the importance of literature materials in recording American history Mention of The Declaration of Independence as a historical document Overview of the historical context and reasons for its [...]

The Declaration of Independence is one of the most important documents in American history, embodying the ideals of freedom and self-governance that have shaped the nation. Written by Thomas Jefferson and adopted by the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Declaration of Independence — Summary, Facts, and Text

July 4, 1776

Drafted by Thomas Jefferson, and edited by luminaries such as Benjamin Franklin and John Adams, the Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776.

This painting by Howard Pyle depicts Thomas Jefferson working on the Declaration of Independence. Image Source: Google Arts & Culture .

Declaration of Independence Summary

Nearly 250 years since it was signed, the Declaration of Independence remains one of the most seminal political documents ever written. The Declaration consists of three major parts.

The preamble employs the enlightened reasoning of Locke, Rousseau, and Thomas Paine , to establish a philosophical justification for a split with Great Britain.

The main body lists numerous grievances and examples of crimes of the King against the people of the colonies, making him “unfit to be the ruler of a free people.” This section also challenges the legitimacy of legislation enacted by Parliament and chastises the people of England for remaining “deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity.” In the conclusion, the climax of the document, Congress announces to the world that “the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States.”

On the morning of July 5, Congress sent copies of the Declaration of Independence to various assemblies, conventions, and committees of safety, as well as to the commanders of Continental troops. The die had been cast. Ideas presented in the preamble remained to be earned on the battlefield, but the seeds of a new nation founded upon unalienable rights and the consent of the governed were sown in the Declaration of Independence.

Declaration of Independence Facts

On May 15, 1776, the Virginia Convention passed a resolution that “the delegates appointed to represent this colony in General Congress be instructed to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent states.”

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia presented to Congress a motion , “Resolved, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”

On June 11, 1776, Congress created a Committee of Five to draft a statement presenting to the world the colonies’ case for independence.

The members of the Committee of Five included Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, John Adams of Massachusetts, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and Roger Sherman of Connecticut.

The Committee of Five assigned the task of drafting the Declaration of Independence to Thomas Jefferson.

Thomas Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence between June 11 and June 28, 1776. The draft is most famous for Jefferson’s criticism of King George III for Great Britain’s involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade .

On Friday, June 28, 1776, the Committee of Five presented to Congress the document entitled “A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States Of America in General Congress assembled.”

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress approved Richard Henry Lee’s proposed resolution of June 7, thereby declaring independence from Great Britain.

On July 4, 1776, after two days of debate and editing, the Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence submitted by the Committee of Five.

The Declaration of Independence is made up of three major parts: the preamble; the body, and the conclusion.

The preamble of the Declaration of Independence establishes a philosophical justification for a split with Britain — all men have rights, the government is established to secure those rights, if and when such government becomes a hindrance to those rights, it should be abolished – or ties to it broken.

The main body of the Declaration lists numerous grievances and examples of crimes of the King against the people of the colonies, making him “; unfit to be the ruler of a free people.”

The main body also challenges the legitimacy of legislation enacted by Parliament and chastises the people of England for remaining “deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity.”

In the conclusion, the climax of the document, Congress announces to the world that “the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States.”

The first printed copies of the Declaration of Independence were turned out from the shop of John Dunlap, the official printer to the Congress.

The exact number of broadsides printed at John Dunlap’s shop on the evening of July 4 and the morning of July 5 is undetermined but estimated to be between one and two hundred copies.

On the morning of July 5, members of Congress sent copies to various assemblies, conventions, and committees of safety as well as to the commanders of Continental troops.

On July 5, a copy of the printed version of the approved Declaration was inserted into the “rough journal” of the Continental Congress for July 4.

The July 5 copies included the names of only John Hancock and Charles Thompson, Secretary of the Continental Congress.

There are 24 copies known to exist of what is commonly referred to as “ the Dunlap broadside,” 17 owned by American institutions, 2 by British institutions, and 5 by private owners.

On July 9, the Declaration was officially approved by the New York Convention, completing the approval of all 13 colonies.

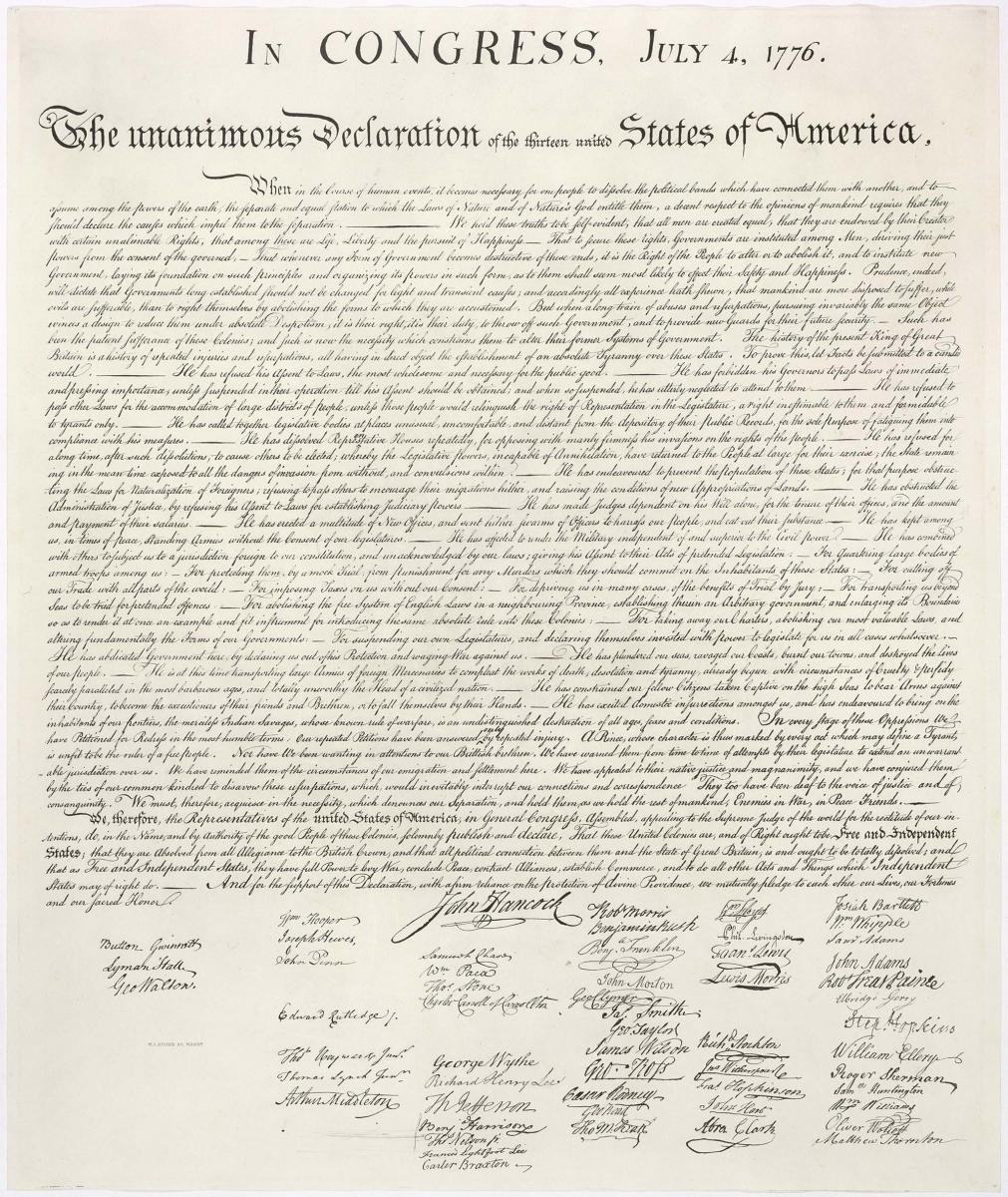

On July 19, Congress was able to order that the Declaration be “fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile [sic] of ‘The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America’ and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress.”

Timothy Matlack was probably the person who wrote — or engrossed — the text of the Declaration on the document that was signed. He is known as the “Scribe of the Declaration of Independence.”

Delegates began signing the Declaration of Independence on August 2, 1776, after it was engrossed on parchment.

John Hancock, the President of the Congress, was the first to sign the Declaration of Independence.

Other than John Hancock and Charles Thompson, whose names appeared on the original printed versions of the Declaration, the names of the other signers were kept secret until 1777 for fear of British reprisals.

On January 18, 1777, Congress ordered the second official printing of the document, including the names of all of the signers.

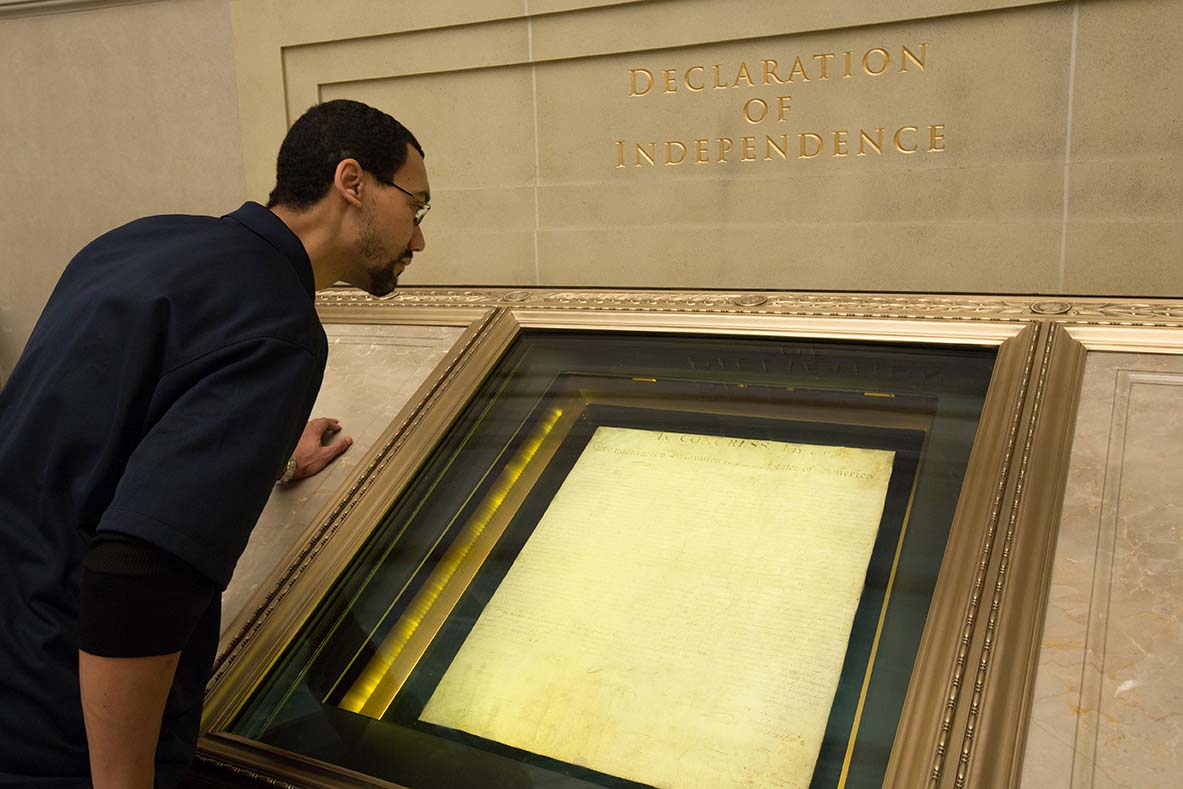

The original parchment version of the Declaration of Independence is held by the National Archives and Records Administration, in Washington, D.C.

Declaration of Independence Text

In Congress, July 4, 1776.

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, –That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.–Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world.

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.

He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harrass our people, and eat out their substance.

He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power.

He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies:

For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our Brittish brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred to disavow these usurpations, which, would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends.

We, therefore, the Representatives of the united States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States; that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace, contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor.

Signers of the Declaration of Independence

Connecticut

- Roger Sherman

- Samuel Huntington

- William Williams

- Oliver Wolcott

- Caesar Rodney

- George Read

- Thomas McKean

- Button Gwinnett

- George Walton

- Samuel Chase

- William Paca

- Thomas Stone

- Charles Carroll of Carrollton

Massachusetts

- John Hancock

- Samuel Adams

- Robert Treat Paine

- Elbridge Gerry

New Hampshire

- Josiah Bartlett

- Matthew Thornton

- William Whipple

- Richard Stockton

- John Witherspoon

- Francis Hopkinson

- Abraham Clark

- William Floyd

- Philip Livingston

- Francis Lewis

- Lewis Morris

North Carolina

- William Hooper

- Joseph Hewes

Pennsylvania

- Robert Morris

- Benjamin Rush

- Benjamin Franklin

- John Morton

- George Clymer

- James Smith

- George Taylor

- James Wilson

- George Ross

Rhode Island

- Stephen Hopkins

- William Ellery

South Carolina

- Edward Rutledge

- Thomas Heyward, Jr.

- Thomas Lynch, Jr.

- Arthur Middleton

- George Wythe

- Richard Henry Lee

- Thomas Jefferson

- Benjamin Harrison

- Thomas Nelson, Jr.

- Francis Lightfoot Lee

- Carter Braxton

Declaration of Independence for APUSH

Use the following links and videos to study the Declaration of Independence, the American Revolution, and the American Revolutionary War for the AP US History Exam. Also, be sure to look at our Guide to the AP US History Exam .

Declaration of Independence APUSH Definition and Significance

The definition of the Declaration of Independence for APUSH is a foundational document adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. Drafted primarily by Thomas Jefferson, it announced the independence of the 13 Original Colonies from British rule. The document laid out the principles of individual rights and self-government, arguing that all people are entitled to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

The significance of the Declaration of Independence for APUSH is that it justified the decision to separate from Great Britain, and established a set of ideals that eventually led to the creation of the United States Constitution. The Declaration of Independence is considered one of the four founding documents, along with the Articles of Association , the Articles of Confederation , and the Constitution .

Declaration of Independence Explained for APUSH

This video from Heimler’s History explains the Declaration of Independence.

- Content for this article has been compiled and edited by American History Central Staff .

Visit the new and improved Hamilton Education Program website

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

The Declaration of Independence

By tim bailey, view the declaration in the gilder lehrman collection by clicking here and here . for additional primary resources click here and here ., unit objective.

This unit is part of Gilder Lehrman’s series of Common Core State Standards–based teaching resources. These units were written to enable students to understand, summarize, and analyze original texts of historical significance. Students will demonstrate this knowledge by writing summaries of selections from the original document and, by the end of the unit, articulating their understanding of the complete document by answering questions in an argumentative writing style to fulfill the Common Core State Standards. Through this step-by-step process, students will acquire the skills to analyze any primary or secondary source material.

While the unit is intended to flow over a five-day period, it is possible to present and complete the material within a shorter time frame. For example, the first two days can be used to ensure an understanding of the process with all of the activity completed in class. The teacher can then assign lessons three and four as homework. The argumentative essay is then written in class on day three.

Students will be asked to "read like a detective" and gain a clear understanding of the Declaration of Independence. Through reading and analyzing the original text, the students will know what is explicitly stated, draw logical inferences, and demonstrate these skills by writing a succinct summary and then restating that summary in the student’s own words. In the first lesson this will be facilitated by the teacher and done as a whole-class lesson.

Introduction

Tell the students that they will be learning what Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1776 that served to announce the creation of a new nation by reading and understanding Jefferson’s own words. Resist the temptation to put the Declaration into too much context. Remember, we are trying to let the students discover what Jefferson and the Continental Congress had to say and then develop ideas based solely on the original text.

- The Declaration of Independence, abridged (PDF)

- Teacher Resource: Complete text of the Declaration of Independence (PDF). This transcript of the Declaration of Independence is from the National Archives online resource The Charters of Freedom .

- Summary Organizer #1 (PDF)

- All students are given an abridged copy of the Declaration of Independence and are asked to read it silently to themselves.

- The teacher then "share reads" the text with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a few sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the students will be analyzing the first part of the text today and that they will be learning how to do in-depth analysis for themselves. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #1. This contains the first selection from the Declaration of Independence.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #1 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today the whole class will be going through this process together.

- Explain that the objective is to select "Key Words" from the first section and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in the first paragraph.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: Key Words are very important contributors to understanding the text. Without them the selection would not make sense. These words are usually nouns or verbs. Don’t pick "connector" words (are, is, the, and, so, etc.). The number of Key Words depends on the length of the original selection. This selection is 181 words so we can pick ten Key Words. The other Key Words rule is that we cannot pick words if we don’t know what they mean.

- Students will now select ten words from the text that they believe are Key Words and write them in the box to the right of the text on their organizers.

- The teacher surveys the class to find out what the most popular choices were. The teacher can either tally this or just survey by a show of hands. Using this vote and some discussion the class should, with guidance from the teacher, decide on ten Key Words. For example, let’s say that the class decides on the following words: necessary, dissolve, political bonds (yes, technically these are two words, but you can allow such things if it makes sense to do so; just don’t let whole phrases get by), declare, separation, self-evident, created equal, liberty, abolish, and government. Now, no matter which words the students had previously selected, have them write the words agreed upon by the class or chosen by you into the Key Words box in their organizers.

- The teacher now explains that, using these Key Words, the class will write a sentence that restates or summarizes what was stated in the Declaration. This should be a whole-class discussion-and-negotiation process. For example, "It is necessary for us to dissolve our political bonds and declare a separation; it is self-evident that we are created equal and should have liberty, so we need to abolish our current government." You might find that the class decides they don’t need the some of the words to make it even more streamlined. This is part of the negotiation process. The final negotiated sentence is copied into the organizer in the third section under the original text and Key Words sections.

- The teacher explains that students will now be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. Again, this is a class discussion-and-negotiation process. For example, "We need to get rid of our old government so we can be free."

- Wrap up: Discuss vocabulary that the students found confusing or difficult. If you choose, you could have students use the back of their organizers to make a note of these words and their meanings.

Students will be asked to "read like a detective" and gain a clear understanding of what Thomas Jefferson was writing about in the Declaration of Independence. Through reading and analyzing the original text, the students will know what is explicitly stated, draw logical inferences, and demonstrate these skills by writing a succinct summary and then restating that summary in the student’s own words. In the second lesson the students will work with partners and in small groups.

Tell the students that they will be further exploring the meaning of the Declaration of Independence by reading and understanding Jefferson’s text and then being able to tell, in their own words, what he said. Today they will be working with partners and in small groups.

- Summary Organizer #2 (PDF)

- All students are given the abridged copy of the Declaration of Independence and are asked to read it silently to themselves.

- The students and teacher discuss what they did yesterday and what they decided was the meaning of the first selection.

- The teacher then "share reads" the second selection with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a couple of sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the class will be analyzing the second selection from the Declaration of Independence today. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #2. This contains the second selection from the Declaration.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #2 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today they will be going through the same process as yesterday but with partners and in small groups.

- Explain that the objective is still to select "Key Words" from the second selection and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in that selection.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: The guidelines for selecting Key Words are the same as they were yesterday. However, because this paragraph is shorter than the last one at 148 words, they can pick only seven or eight Key Words.

- Pair the students up and have them negotiate which Key Words to select. After they have decided on their words both students will write them in the Key Words box of their organizers.

- The teacher now puts two pairs together. These two pairs go through the same negotiation-and-discussion process to come up with their Key Words. Be strategic in how you make your groups to ensure the most participation by all group members.

- The teacher now explains that by using these Key Words the group will build a sentence that restates or summarizes what Thomas Jefferson was saying. This is done by the group negotiating with its members on how best to build that sentence. Try to make sure that everyone is contributing to the process. It is very easy for one student to take control of the entire process and for the other students to let them do so. All of the students should write their negotiated sentence into their organizers.

- The teacher asks for the groups to share out the summary sentences they have created. This should start a teacher-led discussion that points out the qualities of the various attempts. How successful were the groups at understanding the Declaration and were they careful to only use Jefferson’s Key Words in doing so?

- The teacher explains that the group will now be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. Again, this is a group discussion-and-negotiation process. After they have decided on a sentence it should be written into their organizers. Again, the teacher should have the groups share out and discuss the clarity and quality of the groups’ attempts.

Students will be asked to "read like a detective" and gain a clear understanding of the meaning of the Declaration of Indpendence. Through reading and analyzing the original text, the students will know what is explicitly stated, draw logical inferences, and demonstrate these skills by writing a succinct summary and then restating that summary in the student’s own words. In this lesson the students will be working individually.

Tell the students that they will be further exploring what Thomas Jefferson was saying in the third selection from the Declaration of Independence by reading and understanding Jefferson’s words and then being able to tell, in their own words, what he said. Today they will be working by themselves on their summaries.

- Summary Organizer #3 (PDF)

- The students and teacher discuss what they did yesterday and what they decided was the meaning of the first two selections.

- The teacher then "share reads" the third selection with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a couple of sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the class will be analyzing the third selection from the Declaration of Independence today. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #3. This contains the third selection from the Declaration.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #3 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today they will be going through the same process as yesterday, but they will be working by themselves.

- Explain that the objective is still to select "Key Words" from the third paragraph and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in that selection.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: The guidelines for selecting Key Words are the same as they were yesterday. However, because this paragraph is longer (208 words) they can pick ten Key Words.

- Have the students decide which Key Words to select. After they have chosen their words they will write them in the Key Words box of their organizers.

- The teacher explains that, using these Key Words, each student will build a sentence that restates or summarizes what Jefferson was saying. They should write their summary sentences into their organizers.

- The teacher explains that they will be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. This should be added to their organizers.

- The teacher asks for students to share out the summary sentences they have created. This should start a teacher-led discussion that points out the qualities of the various attempts. How successful were the students at understanding what Jefferson was writing about?

Tell the students that they will be further exploring what Thomas Jefferson was saying in the fourth selection from the Declaration of Independence by reading and understanding Jefferson’s words and then being able to tell, in their own words, what he said. Today they will be working by themselves on their summaries.

- Summary Organizer #4 (PDF)

- The students and teacher discuss what they did yesterday and what they decided was the meaning of the first three selections.

- The teacher then "share reads" the fourth selection with the students. This is done by having the students follow along silently while the teacher begins reading aloud. The teacher models prosody, inflection, and punctuation. The teacher then asks the class to join in with the reading after a couple of sentences while the teacher continues to read along with the students, still serving as the model for the class. This technique will support struggling readers as well as English Language Learners (ELL).

- The teacher explains that the class will be analyzing the fourth selection from the Declaration of Independence today. All students are given a copy of Summary Organizer #4. This contains the fourth selection from the Declaration.

- The teacher puts a copy of Summary Organizer #4 on display in a format large enough for all of the class to see (an overhead projector, Elmo projector, or similar device). Explain that today they will be going through the same process as yesterday, but they will be working by themselves.

- Explain that the objective is still to select "Key Words" from the fourth paragraph and then use those words to create a summary sentence that demonstrates an understanding of what Jefferson was saying in that selection.

- Guidelines for selecting the Key Words: The guidelines for selecting Key Words are the same as they were yesterday. Because this paragraph is the longest (more than 219 words) it will be challenging for them to select only ten Key Words. However, the purpose of this exercise is for the students to get at the most important content of the selection.

- The teacher explains that now they will be putting their summary sentence into their own words, not having to use Jefferson’s words. This should be added to their organizers.

This lesson has two objectives. First, the students will synthesize the work of the last four days and demonstrate that they understand what Jefferson was saying in the Declaration of Independence. Second, the teacher will ask questions of the students that require them to make inferences from the text and also require them to support their conclusions in a short essay with explicit information from the text.

Tell the students that they will be reviewing what Thomas Jefferson was saying in the Declaration of Independence. Second, you will be asking them to write a short argumentative essay about the Declaration; explain that their conclusions must be backed up by evidence taken directly from the text.

- All students are given the abridged copy of the Declaration of Independence and then are asked to read it silently to themselves.

- The teacher asks the students for their best personal summary of selection one. This is done as a negotiation or discussion. The teacher may write this short sentence on the overhead or similar device. The same procedure is used for selections two, three, and four. When they are finished the class should have a summary, either written or oral, of the Declaration in only a few sentences. This should give the students a way to state what the general purpose or purposes of the document were.

- The teacher can have the students write a short essay now addressing one of the following prompts or do a short lesson on constructing an argumentative essay. If the latter is the case, save the essay writing until the next class period or assign it for homework. Remind the students that any arguments they make must be backed up with words taken directly from the Declaration of Independence. The first prompt is designed to be the easiest.

- What are the key arguments that Thomas Jefferson makes for the colonies’ separation from Great Britain?

- Can the Declaration of Independence be considered a declaration of war? Using evidence from the text argue whether this is or is not true.

- Thomas Jefferson defines what the role of government should and should not be. How does he make these arguments?

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

- Research & Education

- For Scholars

- Jefferson Library

- Library Reference

- Monticello's Online Resources

- Enlighten the People Project

Enlighten the People: Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence

This guide is intended to direct to information on the Declaration of Independence, including Thomas Jefferson’s role as author, its commissioning by the Committee of Five, and its adoption by the thirteen British colonies.

1. Thomas Jefferson Portal

- When viewing an individual title, please click “View Description” to see more detail

- The Declaration of Independence and Thomas Jefferson

- The Declaration of Independence and the Second Continental Conference

- The Declaration of Independence and the Committee of Five

- The Declaration of Independence and ratification

2. Virginia Heritage

- Declaration of Independence and Thomas Jefferson

3. Thomas Jefferson Encyclopedia

- Declaration of Independence

- Declaration of Independence by Stone (Engraving)

4. Early American History Sites

- Use the custom search bar to search “declaration of independence” and add other terms such as “ratif*”, “writing,” “committee of five”

5. Founders Online

- Declaration of Independence and Thomas Jefferson in the Revolutionary Period

- Declaration of Independence and the Second Continental Congress

- Declaration of Independence and adoption

6. Jefferson Quotes & Family Letters

ADDRESS: 931 Thomas Jefferson Parkway Charlottesville, VA 22902 GENERAL INFORMATION: (434) 984-9800

Essay: The Declaration of Independence

While writing the Declaration of Independence, America’s Founders looked to the lessons of human nature and history to determine how best to structure a government that would promote liberty. They started with the principle of consent of the governed: the only legitimate government is one which the people themselves have authorized. But the Founders also guarded against the tendency of those in power to abuse their authority, and structured a government whose power is limited and divided in complex ways to prevent a concentration of power. They counted on citizens to live out virtues like justice, honesty, respect, humility, and responsibility.

This suggests how members of the Continental Congress such as Thomas Jefferson, who drafted the Declaration, viewed the relationship between a government and its citizens. They believed in a “social compact” among citizens, and between citizens and government. Simply by virtue of existing, they believed, every person has an equal right to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

In July of 1776, the thirteen American colonies had already been at war with England for more than a year. It might seem strange that Americans would feel a need to spend time writing a formal Declaration of Independence, but that is exactly what they did. They felt obligated, they wrote at the very beginning of the Declaration, “by a decent respect to the opinions of mankind” to explain why they no longer considered themselves subjects of the British kingdom.

John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Livingston, and Roger Sherman were members of the committee that drafted the Declaration of Independence. “Founding Fathers: The Declaration Committee,” painting by John Buxton

In order to make these rights secure, they wrote, “Governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

A government, in other words, is established by citizens. The only reason people agree to this is so that government will protect their fundamental rights. King George III, wrote the Founders, had been breaking that agreement for a long time. Instead of protecting the people, his government had engaged in a “long train of abuses” of their rights. They believed no government should be changed “for light and transient causes.” They asserted, however, that once the government becomes an enemy of rights, rather than their protector, citizens have a right to “alter or abolish” that government.

The Declaration of Independence includes a long list of King George’s violations of the colonists’ rights. He had found numerous ways to keep their representatives from having a say in how the colonies were governed, even as he levied new taxes on them. He sent numerous government officials to tell them what to do and kept large numbers of troops among them, even to the point of forcing colonists to give over parts of their homes to soldiers. He restricted their ability to sell their products overseas, locked up colonists without fair trials, and allowed his navy to force colonists into working as sailors against their will.

Meanwhile, wrote Jefferson, the people who had been their fellow British citizens ignored their cries for help. “They too,” according to the Declaration of Independence, “have been deaf to the voice of justice.”

Why did the Founders bother to write all this down? Plenty of people in history had gone to war in order to have power over territory, and none of them had bothered to explain why. Unlike most nations in history, however, America hadn’t gone to war because they were a tribe fighting other tribes, or because Americans wanted to kill people who practiced a different religion, or because they believed the only way to have wealth was to seize other people’s property and make it their own. For most of their lives, they had considered themselves British subjects, and they had been proud of that fact. In the Declaration itself, they call the British their “brethren.”

“Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams while preparing documents in Jefferson’s apartment in Philadelphia,” painting by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris

They wrote the Declaration of Independence precisely because being British subjects had meant something important to them. It was no small thing to break the social compact between citizens and government, and the Founders argued that George III had broken Britain’s compact with the American colonies. They believed so strongly in the rights of people that they could not continue to put up with the King’s tyranny. He had broken the contract a legitimate government has with its citizens.

The very justification for a government—protecting the rights of the people—was also the justification, in the absence of that protection, for abolishing that government.

And so we have, wrote the Founders, “Full Power to levy War.” This may seem trivial to put in the document, given that they had already shown that they knew how to wage war against England. Their point, however, was that this was a morally justified war, waged because people will always have the right to defend their freedom.

Reading the Declaration of Independence, we see that the United States is a nation founded not on conquest or tribal loyalty, but on the idea of a free and self-governing people. The Founders—all of them important and well-regarded men—believed so strongly in the right of self-governance and the protection of individual rights that they pledged “our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor” to the cause of independence. They knew the price, should they lose this battle with the most powerful country on the planet, would likely be the loss of all their wealth, as well as their lives.

Declaration of Independence

The members of the Continental Congress who signed Jefferson’s Declaration had more to lose from war with England than most colonists. To pursue their ideas took courage. It is easy to forget this, living as we do under the protection of the Constitution they established. Because there will always be people who want to rule over others, however, we should remember that every generation of citizens must muster the courage to resist those who would take their freedoms away, whether all at once, or bit by bit.

Prologue Magazine

The Declaration of Independence and the Hand of Time

Fall 2016, Vol. 48, No. 3

By Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler and Catherine Nicholson

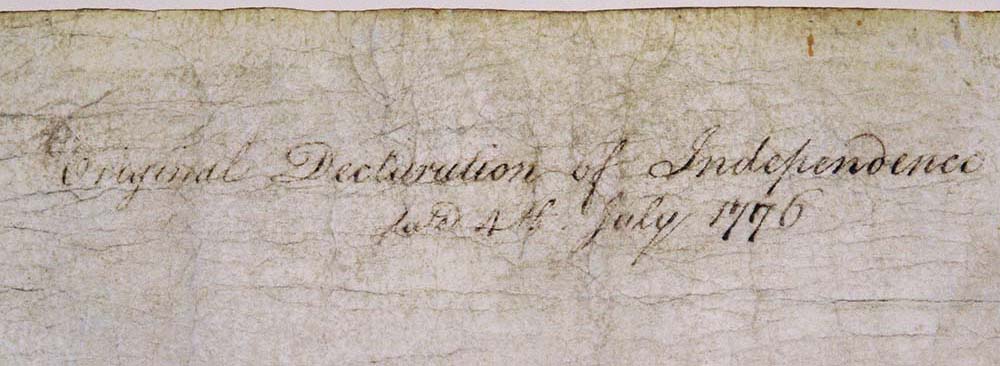

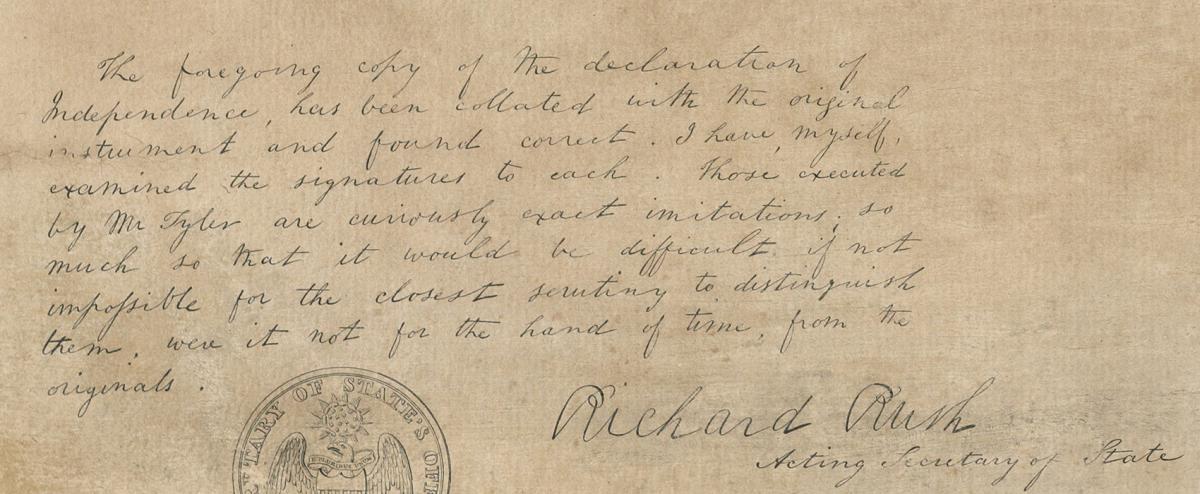

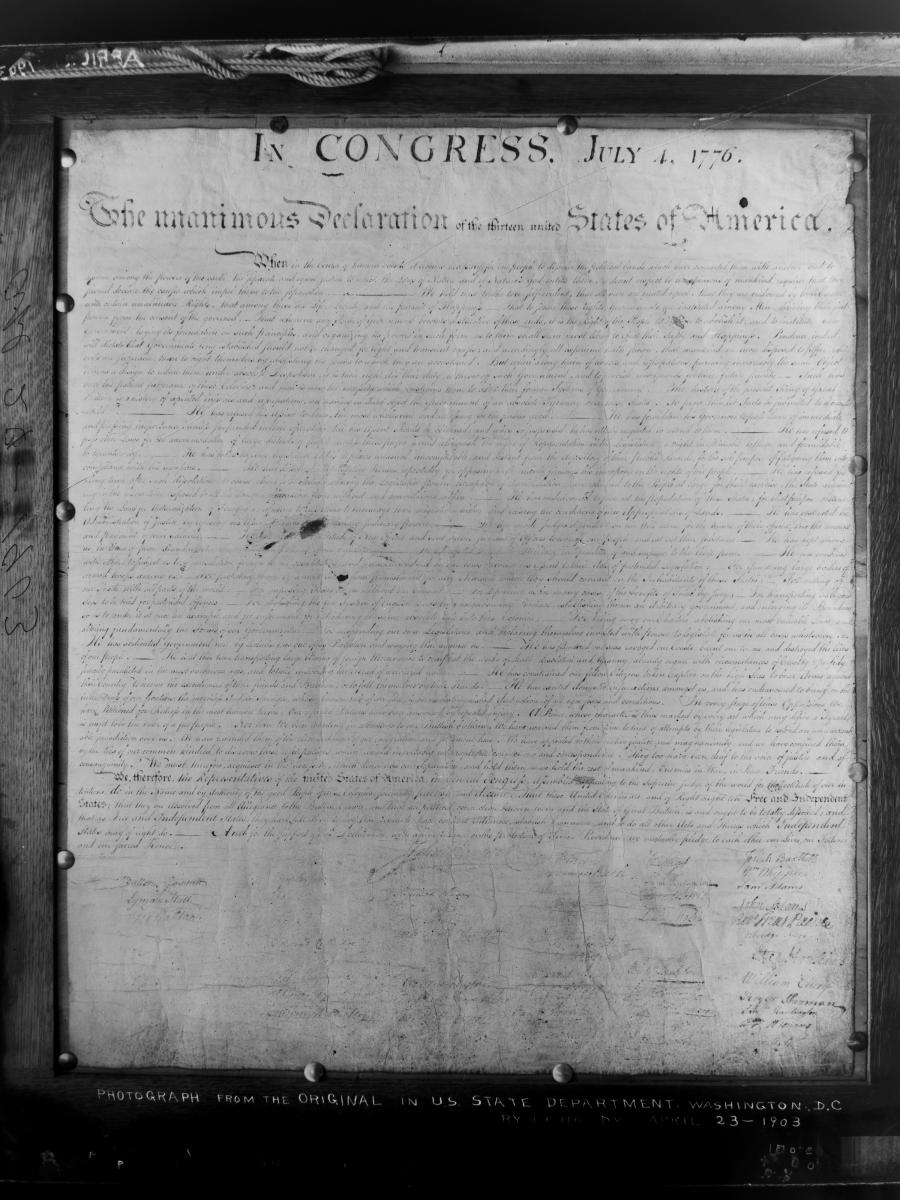

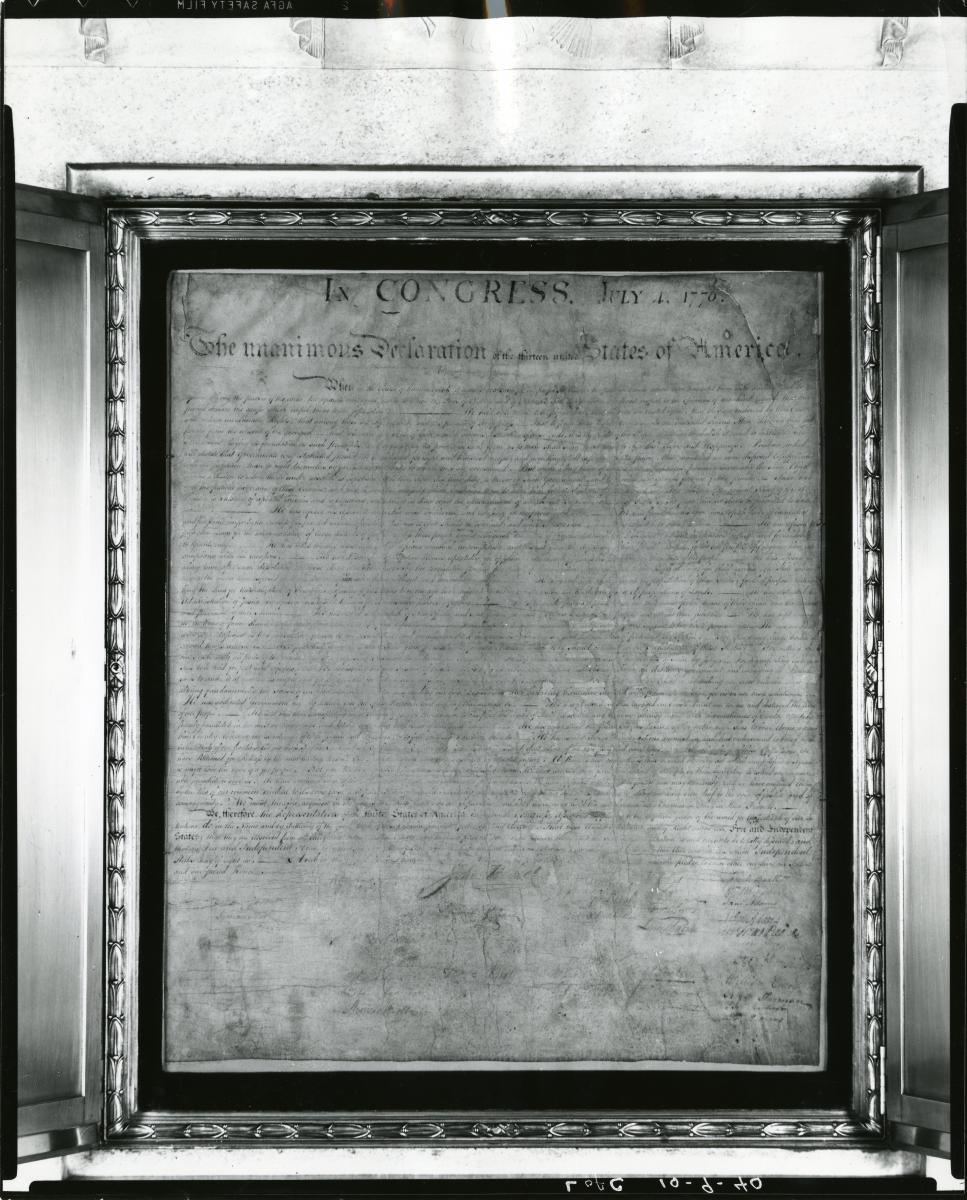

The Stone facsimile engraving of the text and signatures shows how the Declaration appeared in the early 1800s.

View in National Archives Catalog

Every year, more than a million visitors come to the National Archives Building in Washington, DC, to see the Declaration of Independence.

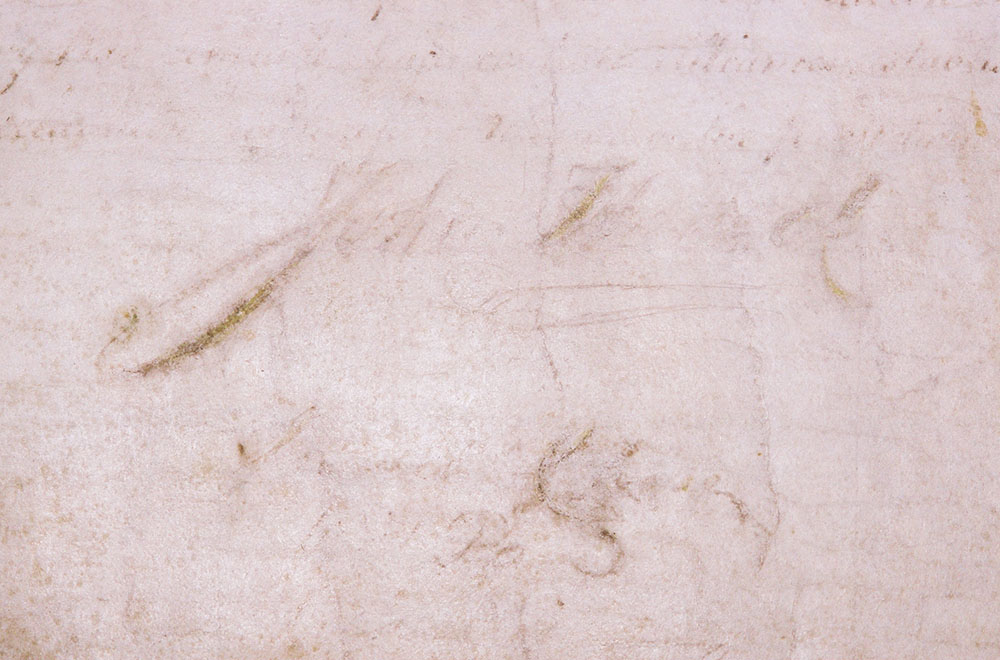

Sometimes you can see them in the Rotunda, patiently waiting for a good position in front of the encasement containing the Declaration. They bend low over the glass to try to make out the faint script and identify the names of the signers.