- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Additional menu

Using concept maps to solve problems, design processes, and codify organizational knowledge

November 7, 2019 by MindManager Blog

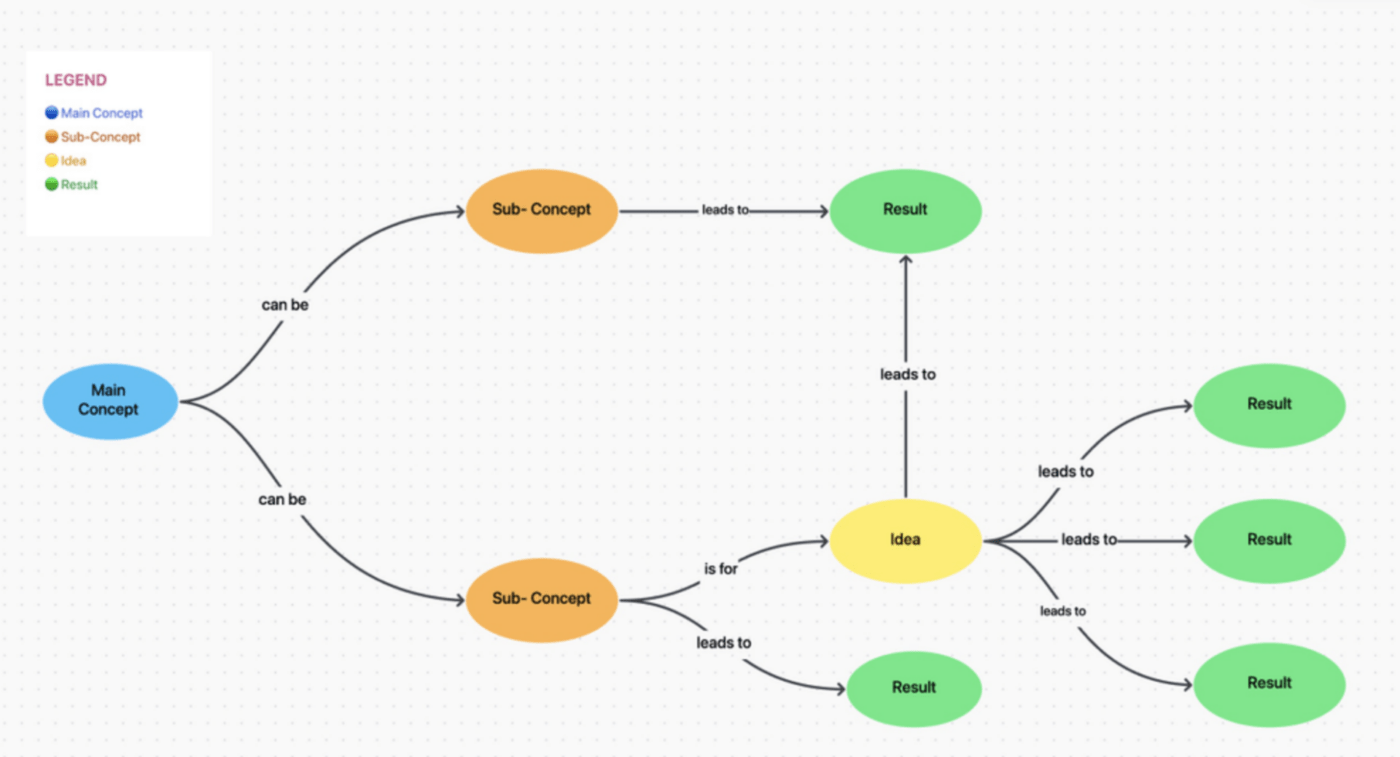

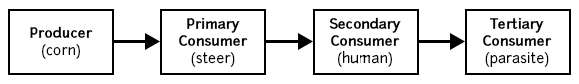

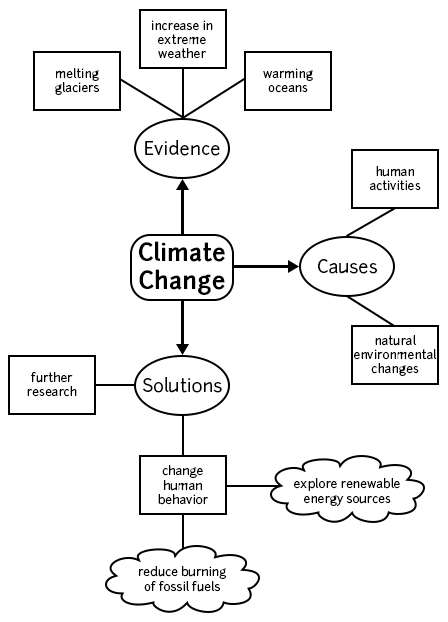

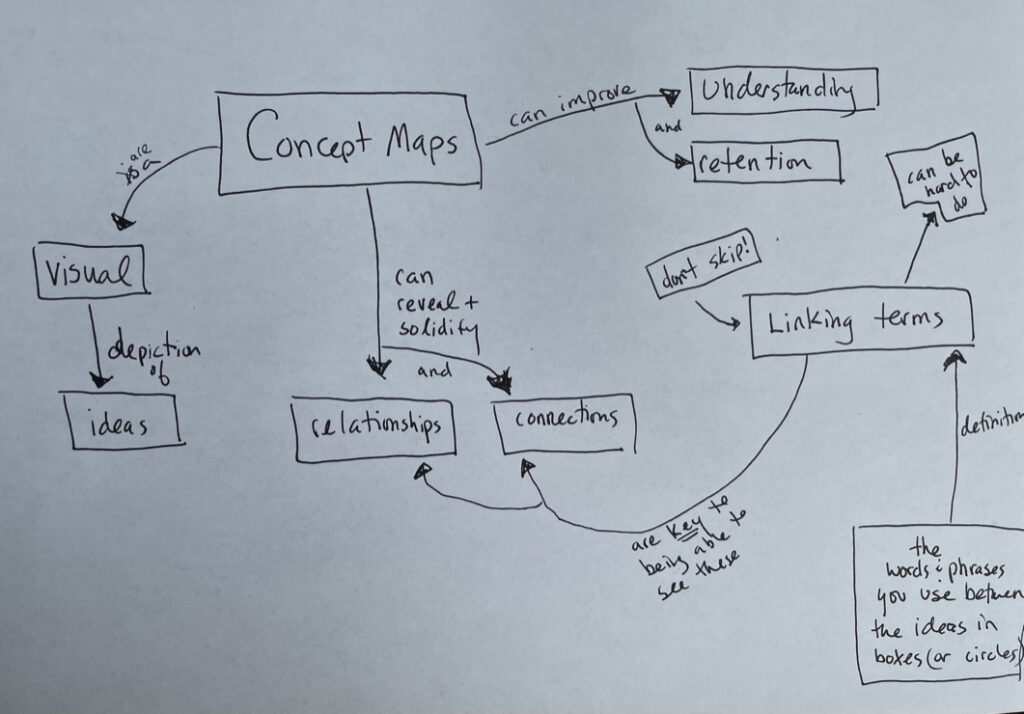

Concept maps are diagrams that illustrate relationships between different concepts and ideas. It is often used by designers, engineers, technical writers, and others to organize and structure knowledge.

Most types of concept maps use boxes to represent ideas and concepts. These are interconnected with lines and/or arrows and labeled with key phrases or words that explain the connections between related concepts. For instance, a ‘home’ might be related to a ‘bedroom’ with the phrase ‘contains a’ or ‘includes a’. So a viewer can understand that, in this example, a home contains bedrooms. Other example phrases include ‘contains’, ‘requires’, ‘owns’, ‘reports to’, etc.

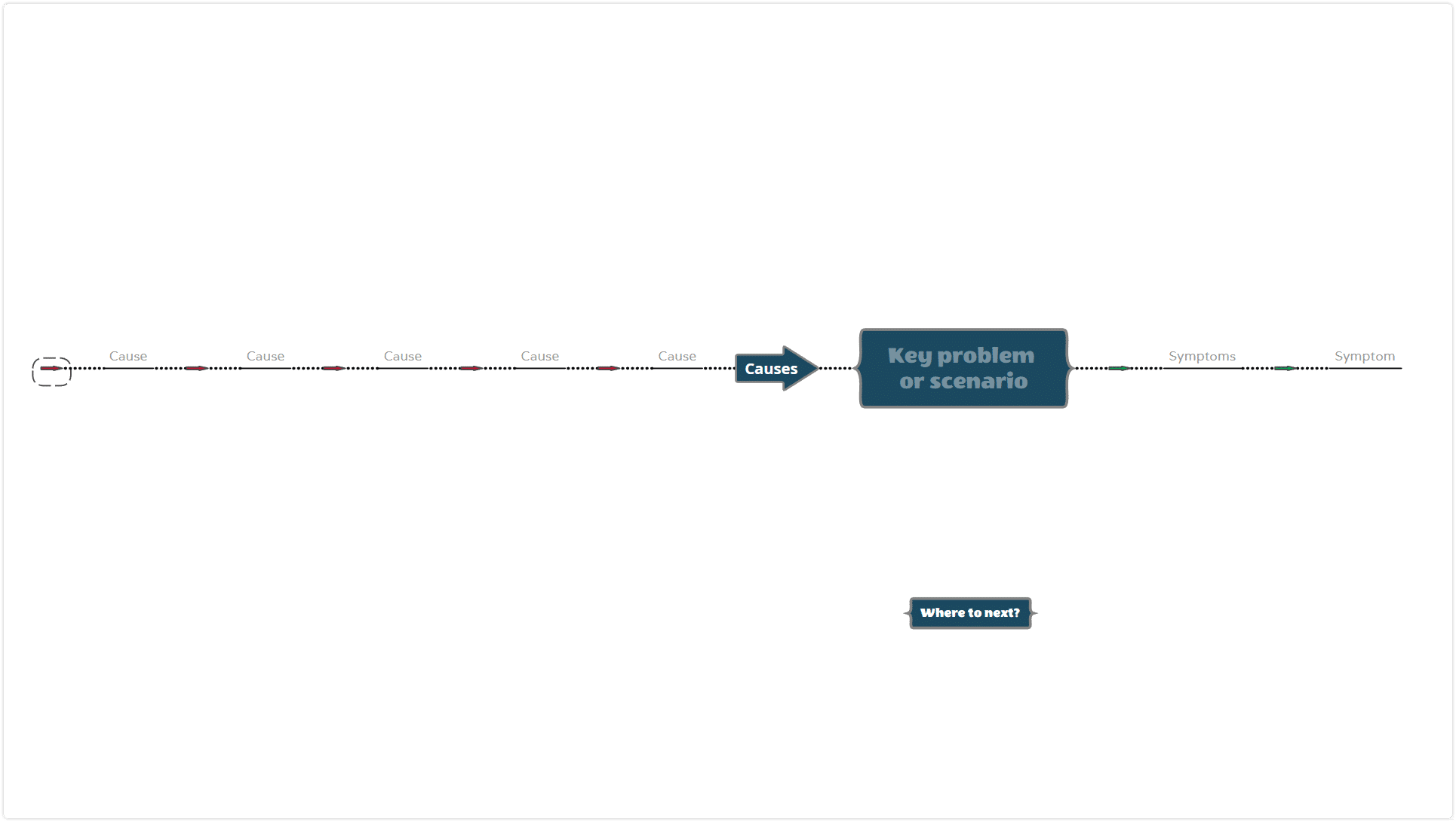

One type of concept mapping focuses on solving an issue or a problem. The better you understand the problem or key question you are trying to answer, the easier it becomes to guide the development and focus of the concept map.

When to use Concept Maps?

Concept maps are widely used in education to codify and document knowledge. They have also been adopted in the business world as well. While you can create a concept map alone, it’s a powerful tool to work with a team to develop a shared understanding, solve problems with a variety of perspectives included in the process, and design products or processes. These diagrams can illustrate our worlds as we know it today as well as how we envision it in the future.

Here are common applications of concept maps in business:

- Aligning teams and individuals with a common framework and understanding of business requirements

- Identifying gaps or contradictions

- Illustrating complex relationships among ideas or within a process

- Building out an ontology

- Documenting (internal or external) current or proposed processes

- Highlighting dependencies within requirements

- Analyzing a market or process

- Making important decisions (and visualizing consequences or impacted concepts when changes are made)

- Mapping organizational or team knowledge

- Training employees and new team members

- Designing software (or other products)

How to create a Concept Map in MindManager?

Here is a quick guide on how to create a concept map within MindManager.

- There is a blank concept map template within MindManager which can serve as your starting point.

- Identify the key focus of your diagram. This can be answering a question or describing a specific concept, topic or process. This should be the originating topic within the diagram and connect to many of the underlying

- Identify and enter all the key concepts that relate to the main idea you identified.

- Select the lines linking concepts together and add keywords or phrases that clarify how the concepts are related.

- Repeat the steps above and revise the concept map as needed.

Key MindManager features to use with your Concept Maps

Concept maps will vary based on the problem you’re trying to solve or information and knowledge you are mapping. While they may look different and illustrate different concepts, here’s a list of key MindManager’s features that you can leverage to add even more context within the diagram, and capabilities to help you focus attention to identify remaining issues or discern potential solutions.

- Use color (fonts, topic fill color) to categorize different ideas.

- Adjust font characteristics to emphasize concepts (e.g. bold, larger fonts, different font types, etc.).

- Change topic shapes to highlight key or related concepts.

- Use topic images to add greater context and enhance the visualization.

- Add topic notes for more in-depth details related to a concept.

- Apply icons and tags to categorize concepts.

- Hyperlink or add attachments to link to more information related to a concept.

- Assign resources to any concepts to denote ‘ownership’ or ‘accountability’ for the part of a process that is being documented.

- View the diagram through multiple lenses. For instance, you are not confined to the layout of the spider diagram. Switch views to see the diagram as a Schedule or see all the concepts as they are categorized by icons or tags in the Icon and Tag views.

- Filter content to either show or hide topics that you have annotated with tags or icon markers. For instance, filter on all the concepts marked as Priority 1 or hide all priorities marked greater than 3.

- Finally, share your diagram by either publishing it to the web (and sharing a link) where anyone can open and view the spider diagram interactively in their browser or export the diagram into a variety of different formats (e.g.

- Microsoft Word, HTML5, Microsoft Project, etc.).

Start Concept Mapping with MindManager Today!

Want to try your hand at Concept Mapping with MindManager? Download a FREE, 30-day trial of MindManager today, and download the Concept Map template to get started.

About the Author:

Michael Deutch is a brand ambassador for MindManager software. After 12 years of working on the MindManager portfolio as VP of Product and, previously, Director of Product and Marketing Solutions, Michael’s extensive product experience makes him an ideal ambassador.

Ready to take the next step?

MindManager helps boost collaboration and productivity among remote and hybrid teams to achieve better results, faster.

Why choose MindManager?

MindManager® helps individuals, teams, and enterprises bring greater clarity and structure to plans, projects, and processes. It provides visual productivity tools and mind mapping software to help take you and your organization to where you want to be.

Explore MindManager

How to Make a Concept Map

- Post author By Jessica Wu

- Post date July 3, 2024

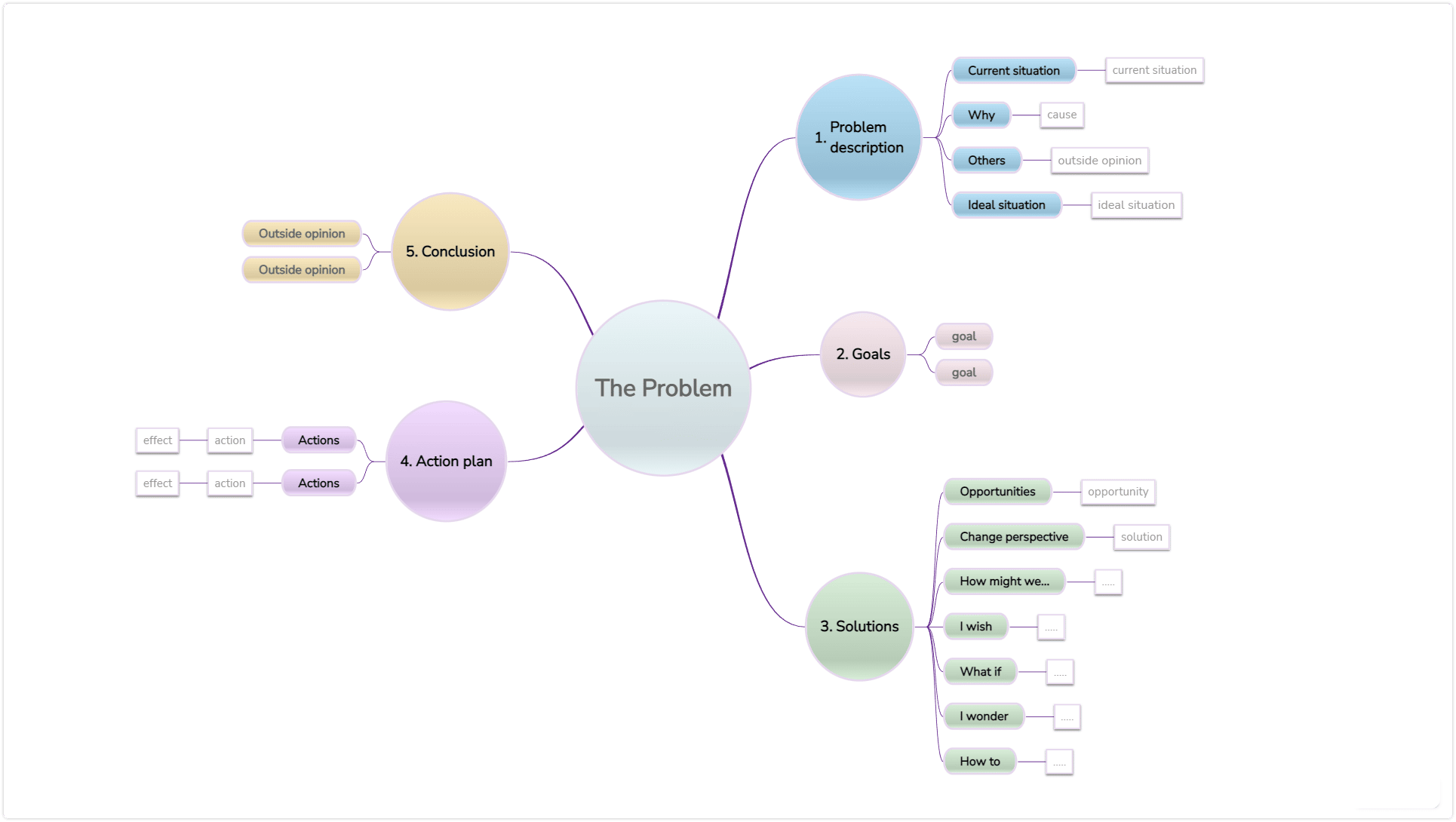

Concept mapping is an invaluable tool for structured thinking and visual organization. Whether you’re a student, educator, business professional, or anyone in between, understanding how to make a concept map can significantly enhance your problem-solving skills [Link to pillar post] and strategies. Here we’ll dive into the intricacies of creating a concept map, with a particular focus on utilizing Frameable Whiteboard, an online whiteboard tool offering a variety of professionally designed templates to make the process seamless and efficient.

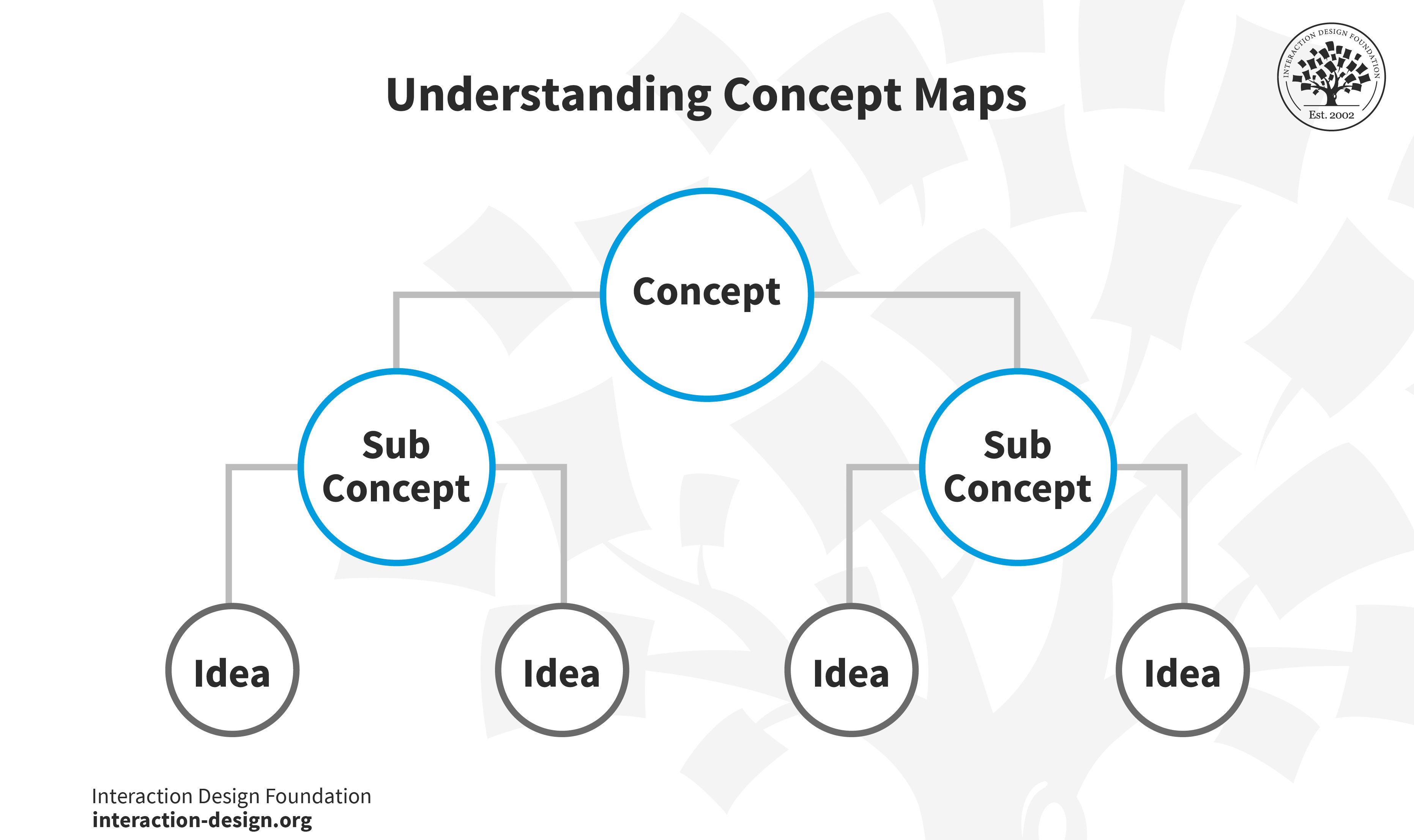

Understanding Concept Maps

Before diving into the creation process, let’s define a concept map . A concept map is a graphical tool for organizing and representing knowledge. It includes concepts, usually enclosed in circles or boxes, and relationships between these concepts are indicated by a connecting line linking two concepts. Words on the line, referred to as linking words or phrases, specify the relationship between the two concepts.

Concept maps are rooted in the theory of meaningful learning developed by David Ausubel, which emphasizes the importance of prior knowledge in learning new information. By visually organizing and structuring this knowledge, concept maps facilitate deeper understanding and knowledge retention.

Benefits of Using Concept Maps

Enhanced problem-solving .

Concept maps are powerful tools for problem-solving. They allow you to break down complex problems into smaller, manageable parts, visually outline the relationships between different components, and identify potential solutions. This structured visual thinking aids in a systematic approach to problem-solving.

Effective problem-solving strategies

By visually organizing information, concept maps help in developing effective problem-solving strategies. You can clearly see the connections and relationships between different elements, which can lead to innovative solutions and strategies that might not be immediately apparent through linear thinking.

Improved structured thinking

Concept maps promote structured thinking by forcing you to organize your thoughts logically and hierarchically. This structured approach is beneficial in various scenarios, from academic research to business planning, as it helps in creating a clear and concise representation of complex information.

Steps to Create a Concept Map

1. identify the main idea.

The first step in creating a concept map is to identify the main idea. This is the central question or problem you want to address with your concept map. The focus question helps to maintain the scope and relevance of your concept map.

2. List relevant concepts

Once you have your focus question, list all relevant concepts (related categories) that relate to this question. These concepts will form the nodes of your concept map. Think broadly and inclusively at this stage to ensure you capture all pertinent information.

3. Organize concepts hierarchically

Organize the listed concepts hierarchically, starting with the most general and inclusive concepts at the top and moving to more specific and detailed concepts at the bottom. This hierarchical structure helps in understanding the relative importance and relationships between concepts.

4. Connect concepts with supporting ideas and factors

Connect the concepts using lines and supporting ideas and factors. Supporting ideas and factors describe the relationship between the connected concepts. This step is crucial as it transforms a simple list of concepts into a meaningful and structured representation of knowledge.

5. Review and refine

Review and refine your concept map. Check for clarity, coherence, and completeness. Make sure that all important relationships are represented and that the linking words accurately describe these relationships.

How to Make a Concept Map Online

Creating a concept map online can be significantly easier and more efficient than doing it on paper. Online tools offer various features that facilitate the creation, sharing, and editing of concept maps, no matter your location. One of the top online whiteboards is Frameable Whiteboard.

What is an Online Whiteboard?

An online whiteboard is a digital platform that allows users to create, share, and collaborate on visual content in real-time. It offers a flexible and interactive space for brainstorming, planning, and organizing ideas visually. Online whiteboards are particularly useful for distributed teams and individuals who need to collaborate without physically being together.

Tools to Make Concept Maps

Several online tools like Miro and Mural can help you create concept maps, but Frameable Whiteboard stands out due to its user-friendly interface, nested cards for structured thinking, affordable price, and real-time collaboration features.

Creating a Concept Map with Frameable Whiteboard

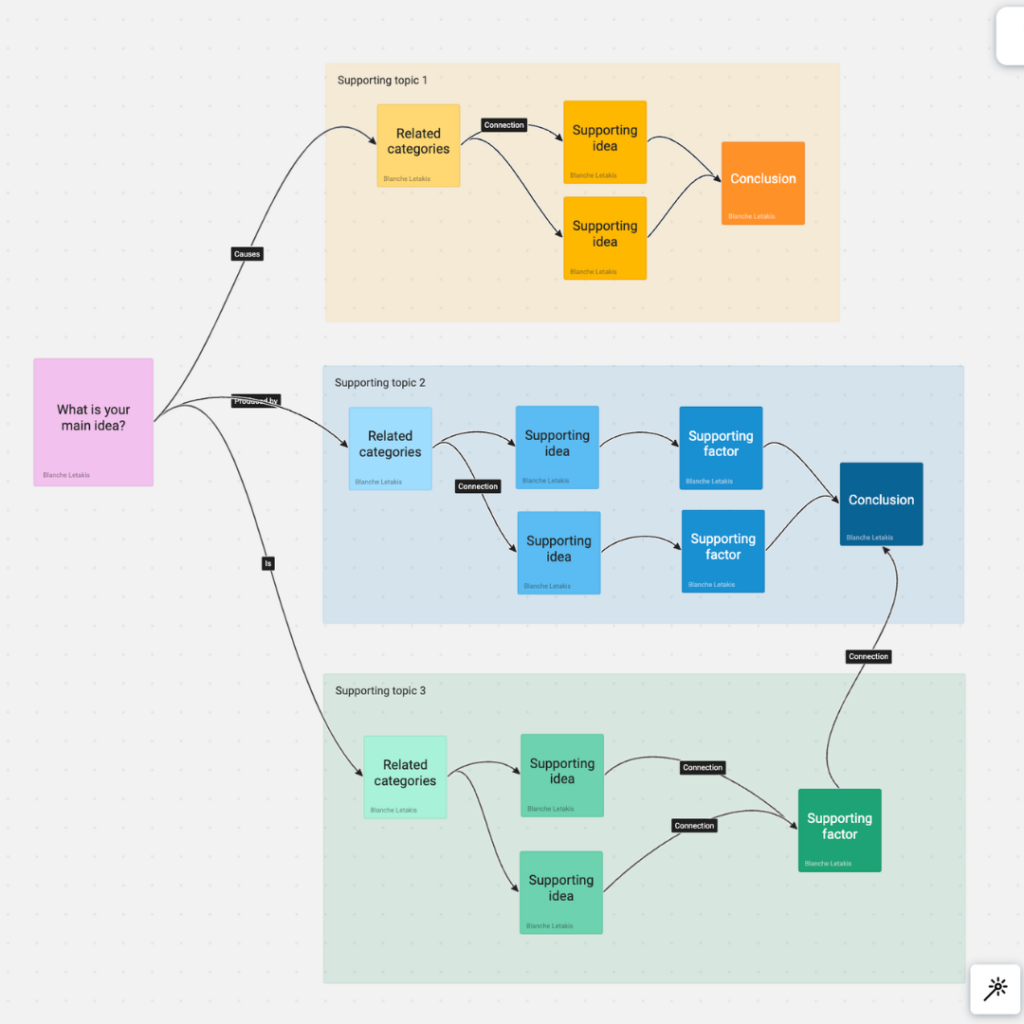

Frameable Whiteboard offers a variety of professionally designed templates, including concept map templates , making it easy to get started. Here’s a step-by-step guide to creating a concept map using Frameable Whiteboard:

1. Sign up and log in

First, sign up for a free account on Frameable Whiteboard. Once you’ve logged in, you can access the wide range of templates and tools available on the platform.

2. Choose the concept map template

Navigate to the recommended templates section at the top of the page and select Show All. A pop-up will show all the templates available for you to scroll and find the concept map template. Once you click the use template button, a new whiteboard with the concept map will open. You’ll find instructions on how to use the concept map template so that you can get started immediately.

3. Customize your concept map

Start customizing the template by adding your main idea, concepts, or related categories, and supporting ideas. Frameable Whiteboard’s intuitive drag-and-drop interface makes it easy to add, move, and connect elements on your concept map.

4. Collaborate in real-time

One of the standout features of Frameable Whiteboard is its real-time collaboration capability. Invite team members to join your whiteboard, where they can contribute ideas, make edits, and provide feedback instantly. This feature is particularly beneficial for collaborative problem-solving, brainstorming sessions, and even task management.

5. Review and finalize

Once you’ve completed your concept map, review it for clarity and completeness. Frameable Whiteboard allows you to easily make adjustments and refinements, ensuring your final concept map is comprehensive and well-organized.

6. Share and export

After finalizing your concept map, you can share it with others by providing a link or exporting it in various formats (PDF, PNG, etc.). This flexibility makes it easy to incorporate your concept map into presentations, reports, or other documents.

Practical Applications of Concept Maps

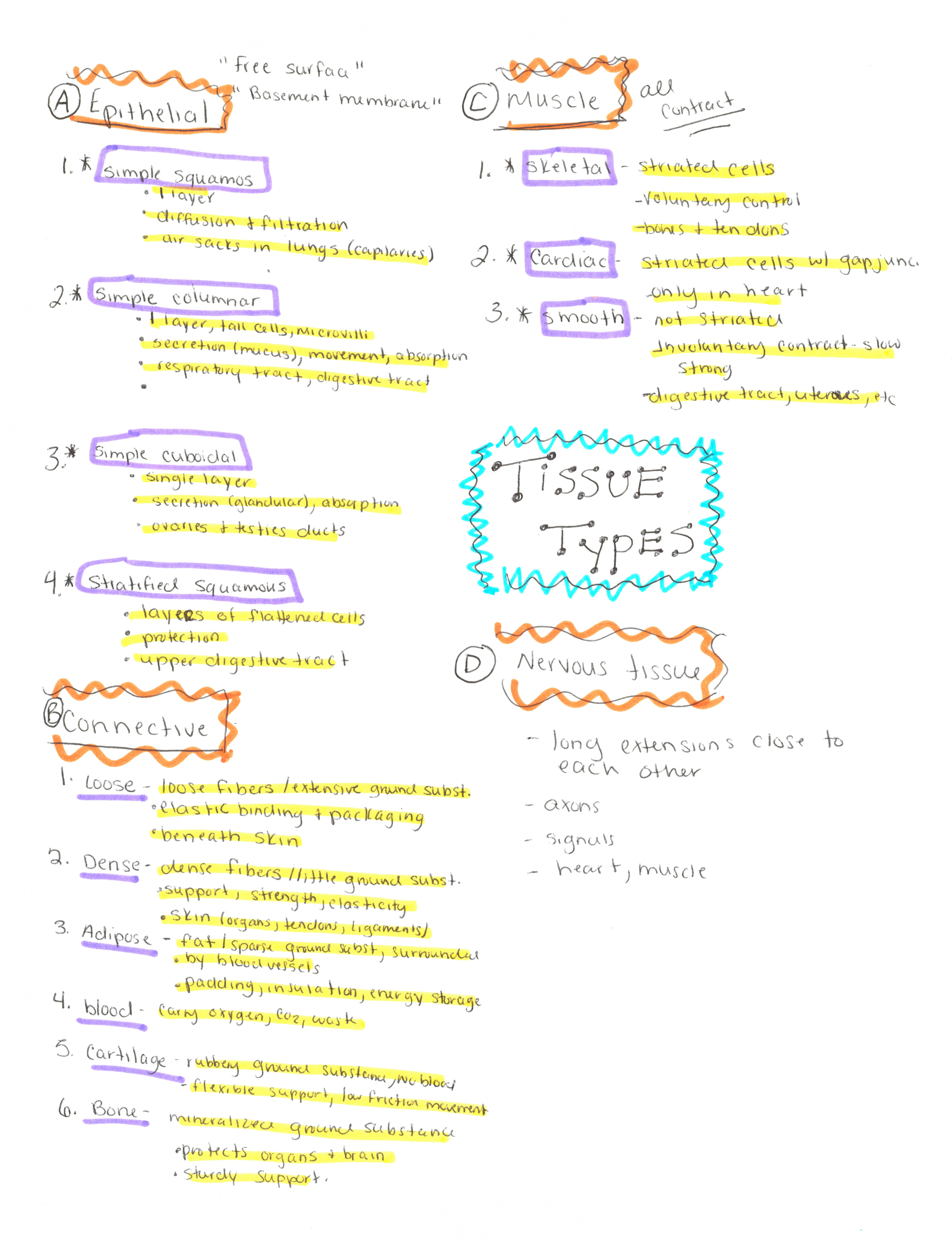

Concept maps are widely used in education to help students understand complex subjects and organize information logically. They can be used for note-taking, studying, and project planning, making learning more interactive and engaging.

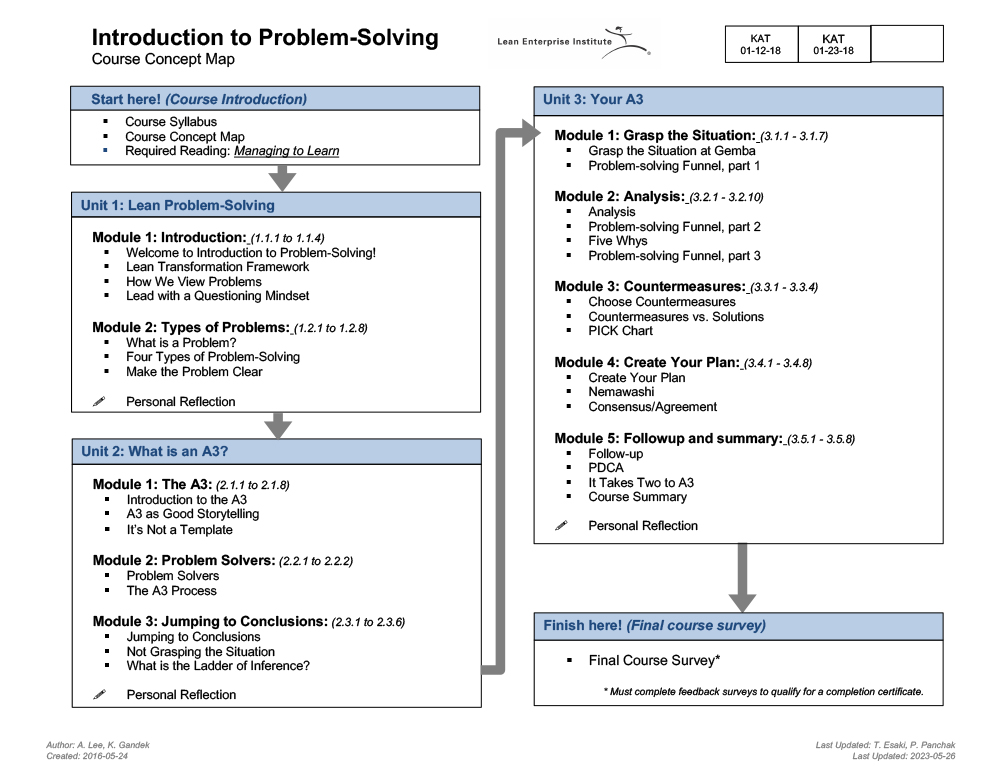

Strategic Planning

In the business, concept maps are invaluable for strategic planning . They allow teams to visualize goals, strategies, and tasks, ensuring that everyone is aligned and working towards common objectives. By mapping out the relationships between different strategic initiatives, concept maps help identify synergies, potential conflicts, and gaps in the overall strategy. This structured visual thinking approach ensures a more coherent and integrated strategic plan.

Project management

Concept maps can significantly enhance project management by providing a clear visual representation of the project’s scope, tasks, and timelines. They help project managers and teams break down the project into smaller, manageable parts, identify dependencies, and ensure all aspects are covered. Using a concept map template from Frameable Whiteboard, project teams can collaboratively plan, monitor, and adjust their projects in real-time, leading to more efficient and successful project execution.

Researchers use concept maps to organize literature reviews, design experiments, and present findings. The visual representation of information helps in identifying gaps, connections, and new research directions.

Unlock the power of concept maps

Concept maps are powerful tools for enhancing problem-solving skills, developing effective problem-solving strategies, and promoting structured thinking. By visually organizing information, they help in understanding complex subjects and identifying relationships between different elements.

Creating a concept map online with tools like Frameable Whiteboard makes the process even more efficient and collaborative. With its user-friendly interface built for structured thinking and real-time collaboration features, Frameable Whiteboard is an excellent choice for anyone looking to improve their structured visual thinking [Link to pillar page] and problem-solving capabilities.

Start exploring the world of concept maps today and unlock your full potential. Sign up for Frameable Whiteboard for free and experience the ease and efficiency of creating concept maps online with its ready-to-use template.

By leveraging the power of concept maps and the capabilities of Frameable Whiteboard, you can enhance your problem-solving skills, develop effective strategies, and achieve your goals with greater ease and efficiency.

Level-up your structured thinking with Frameable Whiteboard

- Tags collaboration , productivity , whiteboard

Transform teamwork with Confluence. See why Confluence is the content collaboration hub for all teams. Get it free

- The Workstream

- Project management

- Concept mapping

What is a concept map and how do you make one

Browse topics.

Concept maps are visual tools for organizing and representing knowledge and ideas in a graphical format. They consist of concepts (or nodes) with connected lines to illustrate their relationships and hierarchy. Concept maps are useful for organizing information, solving problems, and making decisions. They also help with information sharing and collaboration by allowing contributors to convey ideas in an easily understandable format. This format provides a deeper understanding of complex topics. This guide will discuss concept maps, their key features, and how to use one to benefit your team's decision-making process .

What is a concept map?

A concept map is a visual representation that illustrates the relationships between different concepts, ideas, or information. Concept maps typically portray ideas as boxes or circles, known as nodes, and organize them hierarchically with interconnected lines or arrows, known as arcs. These lines have annotated words and phrases that describe the relationships to help understand how concepts connect.

Concept map key features

While concept maps share similarities with other visual tools, they possess distinct features that set them apart. These characteristics contribute to their effectiveness in organizing information and visually representing relationships within a particular knowledge domain. Below are the essential components of a concept map and how they work together.

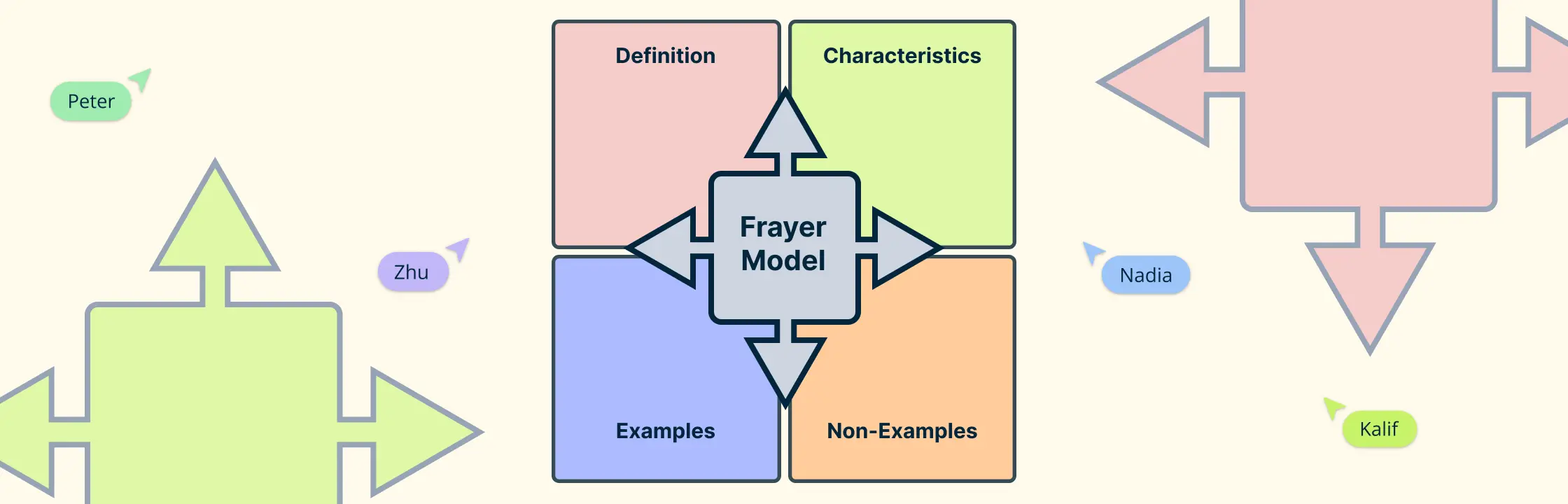

Concepts are the fundamental thoughts, ideas, or topics within the concept map. They serve as the building blocks for organizing information. For example, if a concept map represents a business plan, it could include concepts such as marketing strategies, financial planning, supply chain management, and other key components of the business strategy.

Linking words or phrases

Linking words or phrases describe the relationship between connected concepts. They allow the viewer to understand the flow of information and how the nodes interconnect. Examples of linking words or phrases are “is a part of,” “leads to,” “requires,” “is dependent on,” etc.

Propositional structure

Propositions are statements that combine two or more concepts using linking words. Also known as semantic units or units of meaning, they form the basis for generating new knowledge within a specific domain. Visually depicting interconnected propositions contributes to a greater understanding of the subject matter. In a business plan example, a propositional structure to connect two concepts could look like “marketing strategies increase brand awareness.”

Hierarchical structure

The hierarchical structure positions the most general and inclusive concepts at the top and arranges more specific concepts underneath.

Reading the concept map from top to bottom provides an understanding of concepts from broader categories to more detailed and specific ones.

In a business plan example, the overall business strategy would be at the top level, followed by sub-levels such as marketing strategy, finance, and human resources.

Parking lot

The parking lot is an area for unrelated ideas. It’s a ranked list, starting with the most general concepts and moving to the most specific. It serves as a holding space for ideas until you can determine their appropriate places in the concept map.

Cross-links

Cross-links represent connections between concepts in distinct areas of the map. They enable the visualization of relationships between ideas from diverse domains.

For example, in a concept map for a business plan, you may cross-link market research (part of marketing strategy) and financial forecasting (under financial planning), as insights gained from market research can inform your forecasting and budgeting decisions.

Types of concept maps

The implementation and arrangement of concept maps can vary. Here are four primary types of concept maps:

- Spider maps : Also known as spider diagrams, these concept maps resemble a spider web. The central concept is in the center, and the related topics branch out. This type is most effective when delving into different aspects of a central concept.

- Flowcharts : A flowchart is a visual depiction of a process or workflow. Its linear structure guides readers through the information step-by-step. (See also: how to make a flowchart ).

- System maps : Rather than connecting all ideas to a central concept, a system map concentrates on the relationships between ideas without a clearly defined hierarchical structure.

- Hierarchy maps : Hierarchy maps illustrate rank or position. The primary idea or the concept with the highest rank sits at the top while lower-ranking ideas flow underneath in a structured manner.

How to make a concept map

To create a concept map, follow these steps:

- Identify your primary topic. Ensure that your topic is broad enough to allow for subtopics. You should position this central concept at the top or center of your map, forming the basis of the hierarchical structure.

- Identify the essential concepts relating to the central topic. Place these concepts in the parking lot—a temporary space to store ideas—and arrange them from most broad to most specific.

- Move the key concepts from the parking lot to the concept map, prioritizing the broadest ideas that directly relate to the main topic. Establish the connections between concepts with linking words.

- Double-check the map for accuracy, ensuring the relationships are clear and linking words are coherent. Use cross-links to connect concepts across different sections of the map.

- Expand and revise the map as you generate more ideas.

How to use a concept map

Concept maps have practical applications and offer various benefits in different industries. They help visualize the relationships between various concepts, providing a deeper understanding of complex subjects. Concept maps help individuals retain and understand concepts and their relationships by organizing and illustrating connections between ideas. While concept maps are popular in academia, their adaptability makes them a valuable tool in many fields. Using a concept map:

- Enhances understanding of complex topics

- Organizes information

- Facilitates critical thinking

- Improves team collaboration and communication

- Provides flexibility for generating new ideas and evolving existing ones

Content map examples

Businesses can use concept maps in various ways to enhance communication, decision-making , and knowledge sharing . Here are some ways businesses can apply concept maps:

- Product development : Teams can use concept maps to organize and visualize ideas, features, and requirements in a brainstorming session .

- Project management : By organizing tasks, mapping dependencies, and displaying the project timeline , teams can better visualize the project life cycle .

- Sales funnel : Sales teams can use a concept map to visualize and optimize the sales funnel, mapping the customer journey from lead generation to conversion.

Use Confluence whiteboards for concept mapping

Concept maps are versatile and valuable tools that contribute to enhanced understanding, effective communication, and collaborative problem-solving.

For collaborative concept mapping, use Confluence whiteboards . Confluence whiteboards are an essential tool for any collaborative culture , enabling teams to create and work together freely on an infinite canvas. They bring flexibility to projects, supporting teams as they move from idea to execution.

Confluence whiteboards bridge the gap between where teams think and where teams do. Brainstorming with Confluence whiteboards helps teams organize their work visually and turn ideas into reality, all within a single source of truth.

Try Confluence whiteboards

Content mapping: Frequently asked questions

What is the difference between mind mapping and concept mapping.

While mind mapping and concept mapping are visual techniques for organizing and representing information, they have a few key differences. Mind maps organize thoughts for brainstorming and problem-solving, while concept maps organize thoughts to emphasize the connections between ideas. A mind map tends to be more free-flowing and lacks a hierarchy, while a concept map has a structured layout that represents relationships and hierarchy.

What is the best tool for concept mapping?

The best concept mapping tool depends on your collaboration requirements and ease of use. To bring your work together in a single source of truth, easily provide access to all contributors, and turn your ideas into reality, try Confluence whiteboards.

Can I collaborate on a concept map?

Yes, collaboration is possible on a concept map. A concept map is a productive tool for gathering insights from multiple contributors, especially when using a dedicated platform that supports collaborative editing such as Confluence whiteboards.

You may also like

Project poster template.

A collaborative one-pager that keeps your project team and stakeholders aligned.

Project Plan Template

Define, scope, and plan milestones for your next project.

Enable faster content collaboration for every team with Confluence

Copyright © 2024 Atlassian

Filter by Keywords

How to Make a Concept Map Diagram (With Examples)

Praburam Srinivasan

Growth Marketing Manager

May 30, 2024

Start using ClickUp today

- Manage all your work in one place

- Collaborate with your team

- Use ClickUp for FREE—forever

Managing all the scattered details to keep your projects on track and organized can be a hassle.

Whether juggling tasks, scope, or dependencies, you need a solution to bring some order to the chaos and keep your projects moving smoothly.

That’s where a concept map diagram comes in. 🙂

Think of concept mapping as a visual tool for illustrating the link between complex ideas and their relationship to your key concept.

Whether you’re an educator, student, or business professional, concept maps can help you visualize ideas and organize them to improve your understanding of a particular topic and how to connect ideas for meaningful learning.

Keep reading to learn how to create concept maps to represent ideas. We’ll also share some concept map templates that project managers can use in their daily workflows.

What is a Concept Map Diagram?

Understand the basics of concept maps, 1. spider mapping, 2. hierarchy mapping, 3. flowcharting, 4. system mapping, creativity , design thinking , 1. identify your main concept, 2. group connected concepts, 3. define relationships between concepts and use linking words , 4. add visual elements such as colors and icons, 5. connect them to your workflows , concept map diagrams and learning styles , concept map diagrams in different fields.

A concept map is a visual tool that illustrates the connections between related ideas and concepts. It uses linking lines or arrows to show how these ideas are interconnected.

A visual representation of higher-level concepts on a concept map makes highlighting how the pieces work together easier. Teams working on creative ideas use it as a graphical tool to show meaningful connections between various ideas.

The best part is that use cases for most concept maps for problem-solving and idea generation extend to education, healthcare, knowledge management, and project planning.

Concept Maps vs. Mind Maps

Both mind maps and concept maps are visual tools to organize information and help you with ideation. So, it’s common to get confused between a mind map and a concept map.

However, they differ in structure, purpose, and approach. Here’s a quick overview of how a concept map differs from a mind map . To know more about mind maps, try reading an overview of ClickUp Mind Maps .

| Centered around a single main idea or problem | Shows interconnections within a subject |

| Lines connect sub-topics and related concepts | Arrows represent relationships between concepts |

| Free-form and encourages capturing different ideas and abstract concepts | Hierarchical structure that captures the most relevant and important information |

| Ideal for rapid ideation and brainstorming | Ideal for deep analysis and connecting multiple interconnected ideas |

Read more: 25 mind map examples to structure information ✏️

Now that you understand concept maps vs. mind maps, it’s time to dig deeper into concept maps.

Let’s take a look at all the benefits of concept mapping.

Benefits of concept mapping

- Get a detailed overview: When you build concept maps, you dive into the details of a subject to map out all the sub-topics and ideas related to the main concept. This ideation technique is akin to getting an overview along with connected details

- Organize big ideas : It lets you take scattered ideas and visually organize them in a neat, easy-to-understand diagram

- Understand relationships between ideas: Concept maps show how different ideas and pieces are related. Mapping the conceptual diagram lets you visualize relationships and connections you may totally miss otherwise

- Get innovative insights: When you start linking different areas of the map together through cross-links, it often leads to creative new ideas you hadn’t thought of before

- Retain more information: Concept maps, with their visual elements like shapes and connecting lines, enhance memory retention and improve recall in the learning process compared to verbal communication

A concept map diagram can make grasping complex information, understanding interlinking ideas, and gaining creative insights easy.

Core elements of a concept map

Concepts are the building blocks of a concept map. They’re the shapes you see in the diagram, representing patterns or ideas.

Hierarchical structure

Concept maps follow a hierarchical structure, leading you from general concepts to specific ones.

At the top, you’ve got the big-picture concepts. As you move down, things get more specific and detailed.

Propositional structure

Propositions connect concepts. They comprise two or more concepts connected by handy linking words. This structure forms the basis for building new knowledge.

Cross-links

Cross-links connect concepts in different parts of the map. They show how ideas from different domains connect, sparking creativity.

Linking words/phrases

These connectors are the glue that holds everything together. They sit on the lines between concepts and tell you how they’re related. Short and to the point, they often contain a verb, like ‘causes’ or ‘requires.’

Focus question

Every concept map diagram needs a guiding question that sets the stage for what you’re trying to figure out. Placed right at the top, it keeps you on track as you navigate the map.

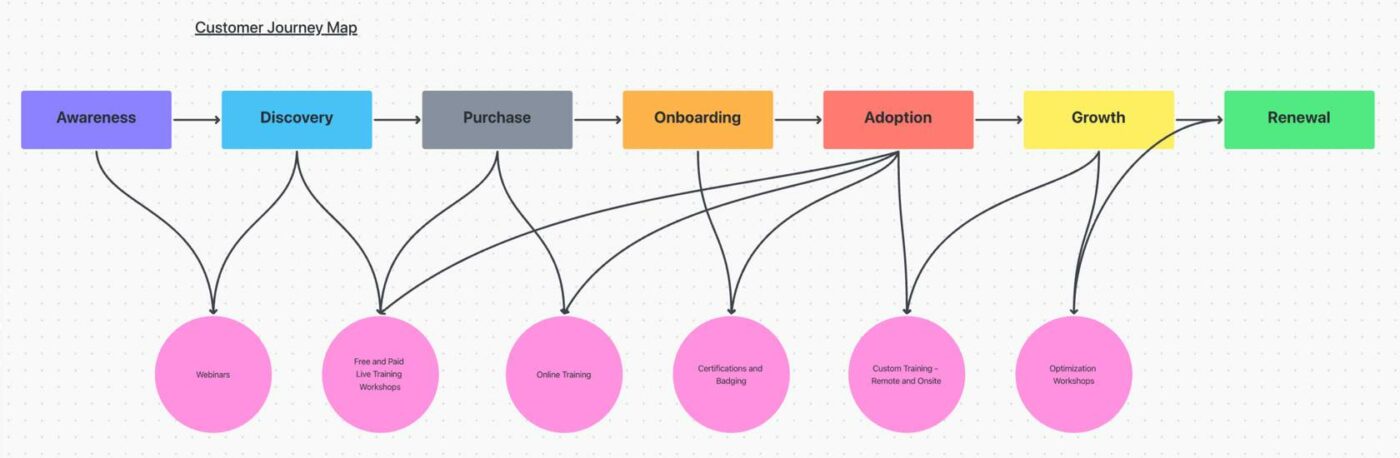

As an example, let’s see how this Customer Journey Concept Map structure was created.

Concept mapping helps you identify the customer’s experience across various touchpoints and gives a view of what happens at each journey stage. Your team can use this as a starting point to make decisions and plan actions.

Types of Concept Maps

While the core elements of all concept map diagrams are simple—concepts and connections—these maps can take various forms to suit different purposes.

Let’s explore the four main types of concept map diagrams and the situations where each is most useful.

This creative concept map resembles a spider web—there is a central idea that branches out to related concepts in a radial pattern .

In this variant of concept mapping, subtopics can further branch into smaller ones, creating a hierarchical structure.

When to use it: Spider mapping is useful for expanding on a single idea or theme.

- Education: Teachers can use spider maps to break down complex subjects for students

- Business: Professionals can brainstorm ideas for products

- Healthcare: Healthcare professionals can organize patient symptoms and medical history

This concept map depicts the order or structure of elements, similar to an organizational chart in a company. It showcases the levels of authority and roles within a system.

When to use it: You can use hierarchy mapping to understand system elements and their hierarchical positions.

- Education: Educators can illustrate academic department structures

- Business: HR managers can visualize reporting relationships and team structures

- Healthcare: Administrators can depict healthcare professional roles within a facility

Commonly recognized as a sequence of steps, flowcharting illustrates the progression of a process. Here, arrows indicate different choices or actions, akin to a situation where you control the results.

When to use it: You can use flowcharting to understand a process or make a decision.

- Education: Students and professors can outline experiments or historical events with flowcharts

- Business: Managers can map workflow processes to streamline operations in the business world

- Healthcare: Nurses can document patient care procedures with flowcharts

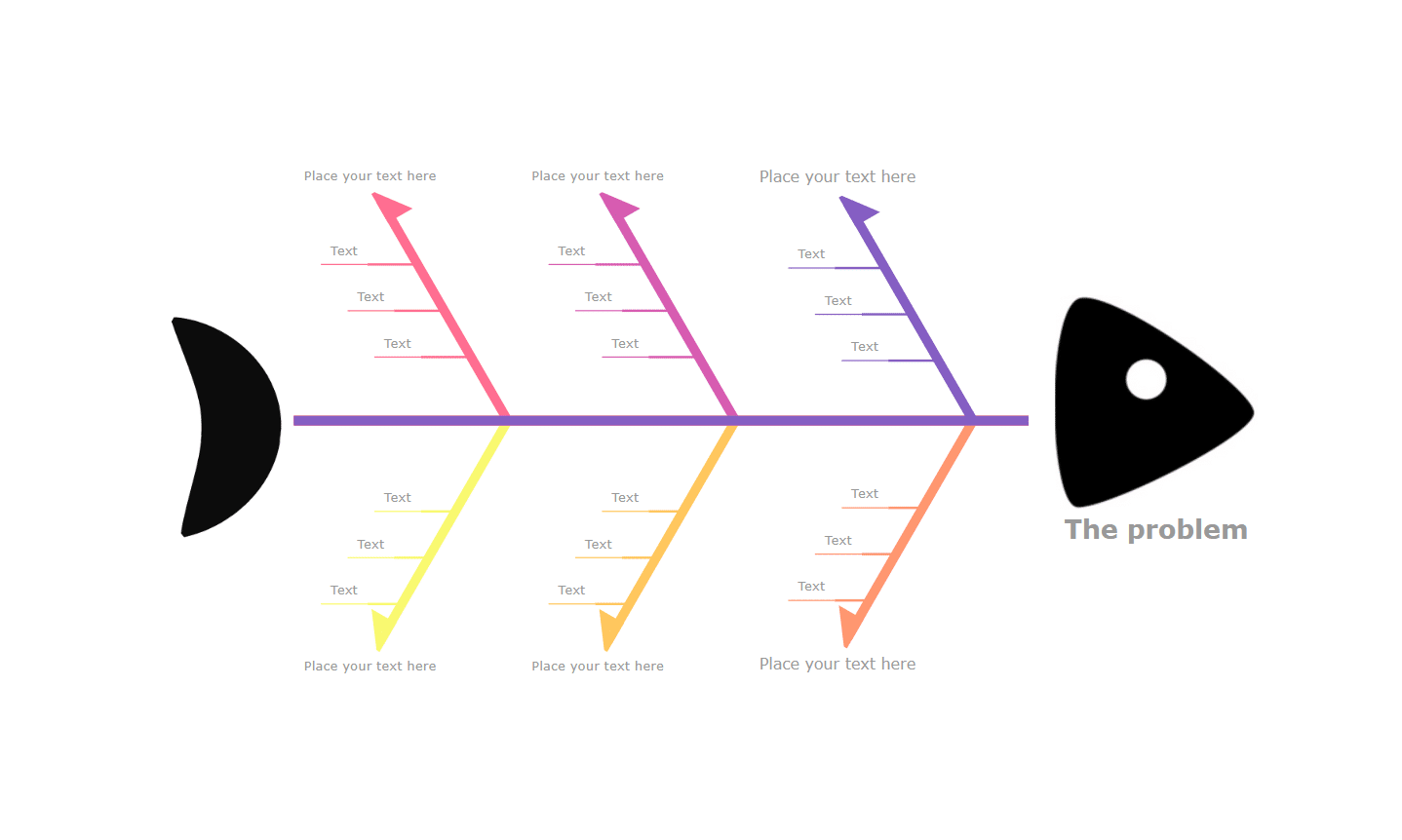

A system map displays the interconnections among various parts of a concept. You may find symbols like ‘+’ or ‘- that denote positive or negative correlations . This concept map diagram can look like a complex web of related examples.

When to use it: When you want to understand the dynamics of a system or a team.

- Education: Students analyze cause-and-effect relationships

- Business: Marketing analysts can explore factors influencing consumer behavior

- Healthcare: Researchers can investigate factors contributing to disease outbreaks and develop intervention strategies

How to Create a Concept Map Diagram

Creativity and design thinking are two prerequisites you must have before you build concept maps.

Creativity helps you find unique connections between ideas and see things differently. It lets you explore the topic thoroughly and captures all the nuances and complexities.

When you design a concept map step, consider how it looks—use colors, shapes, and layout to make it easy to understand. By applying design thinking principles, you can create a concept map that effectively communicates information and engages viewers.

You’re ready to move ahead if you’re set with these requirements.

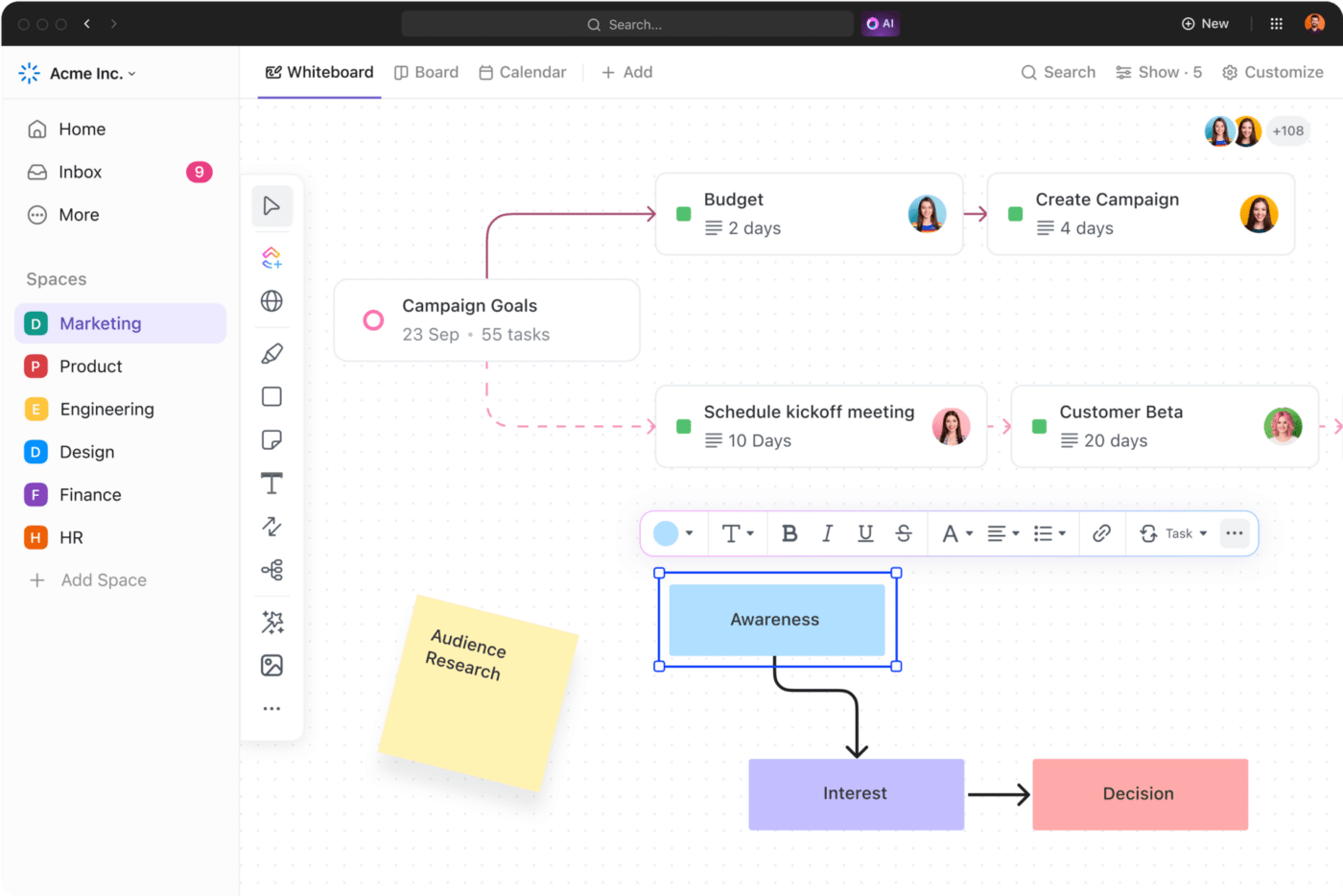

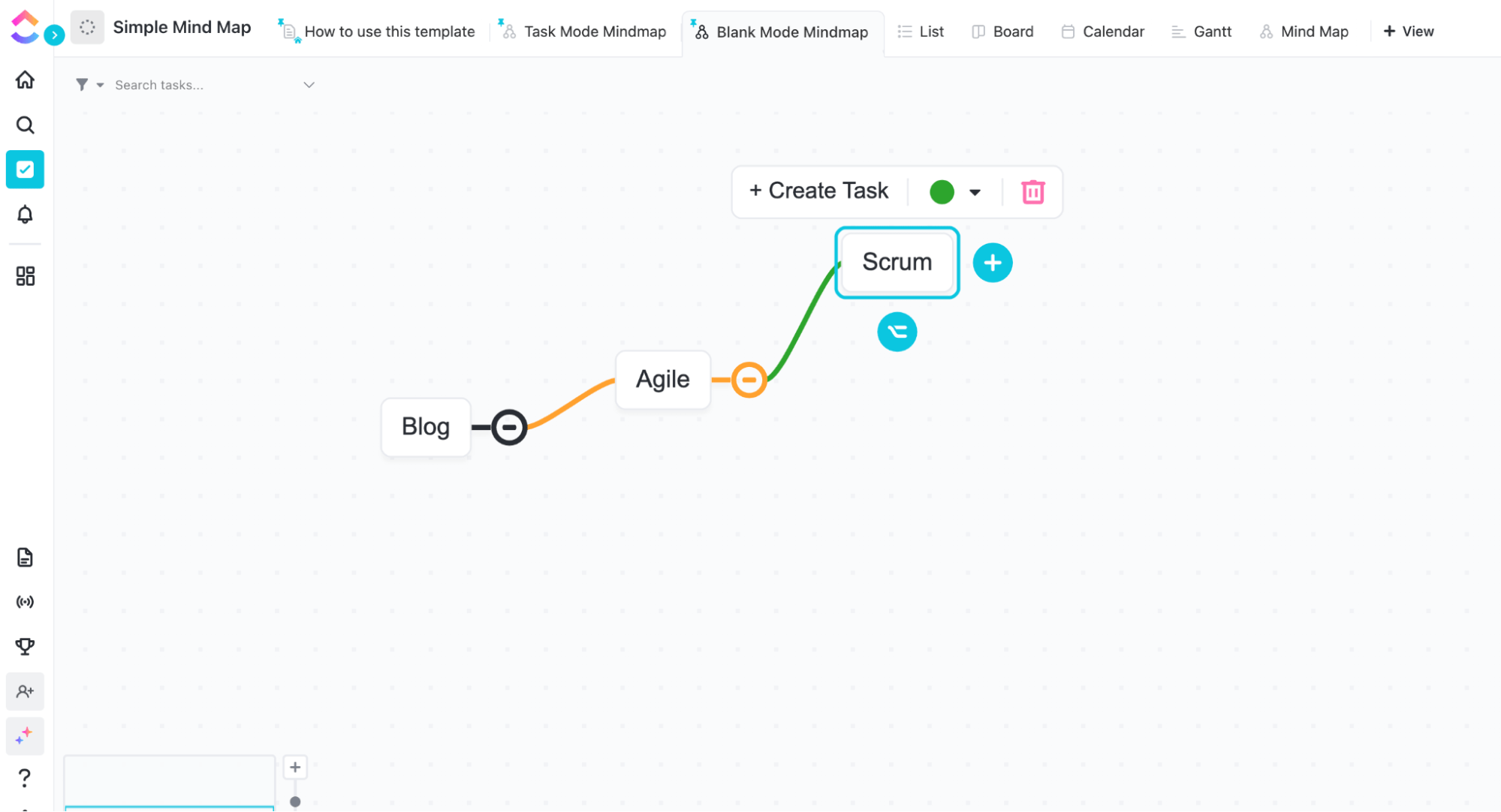

Pro tip💡: You can use the virtual ClickUp Whiteboards to brainstorm and build concept maps with your team. Teamwork FTW!

Step-by-Step Guide to Building a Concept Map

The first task in concept mapping is to figure out the central idea or topic you want to explore extensively.

This core concept will form the foundation for your map and help you identify and organize all the related concepts that branch out from it.

For example, if you aim to understand effective time management strategies as a project manager, start your concept map with the main phrase “time management.”

You can also ask a guiding focus question like ‘How can I manage my time more efficiently?’.

Conversely, multiple concepts will lead to a messy conceptual diagram that your team or audience will find difficult to understand.

Consider using virtual whiteboard software to ideate and structure knowledge and for collaborative concept mapping. The software can handle diagrams, flowcharts, and frameworks your team uses.

For example, ClickUp’s Whiteboards enable your team to create and work freely over a creative canvas. They support your teams from ideation to execution. Build concept maps, color code each idea or task, and convert them into actionable tasks within ClickUp.

Now, it’s time to engage in some freethinking and brainstorming to jot down as many ideas and sub-concepts as possible related to your core theme.

Don’t restrict your thinking. Consider your main concept from multiple angles and explore tangential connections.

As you map out these related ideas, you may discover creative new avenues you hadn’t initially considered.

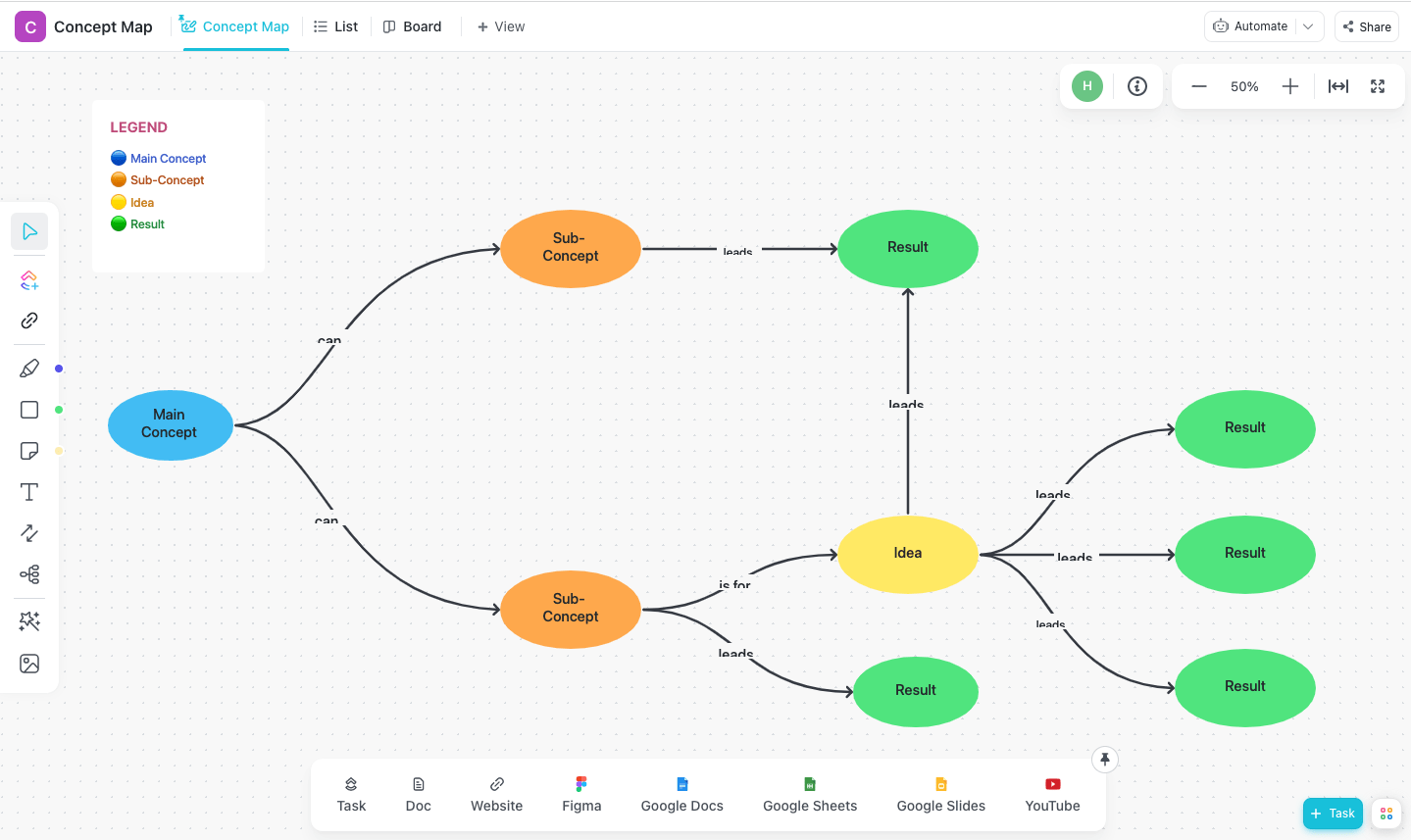

Let your creative juices flow with ClickUp’s Concept Map Template , a customizable and beginner-friendly template for connecting your ideas with related concepts, visualizing how all elements are connected to one another, and organizing and summarizing your ideas.

The benefits of using this template to organize ideas, create relationships between two concepts, and track progress are that it:

- Provides a structured framework to visualize complex information

- Identifies relationships between ideas, processes, and concepts

- Analyzes data to draw meaningful conclusions

- Lets you collaborate with stakeholders on a creative concept

Considering there may be a web of sub-ideas and related concepts surrounding your core ideas, define relationships between them.

For added context, use linking words/phrases to add more content for each relationship.

Once you create the map in a concept map maker , ask yourself:

- Does this concept map design and layout make sense?

- Can I rearrange elements for better clarity?

- Does every element fit in its respective place?

- Can I add a linking phrase to represent this relationship?

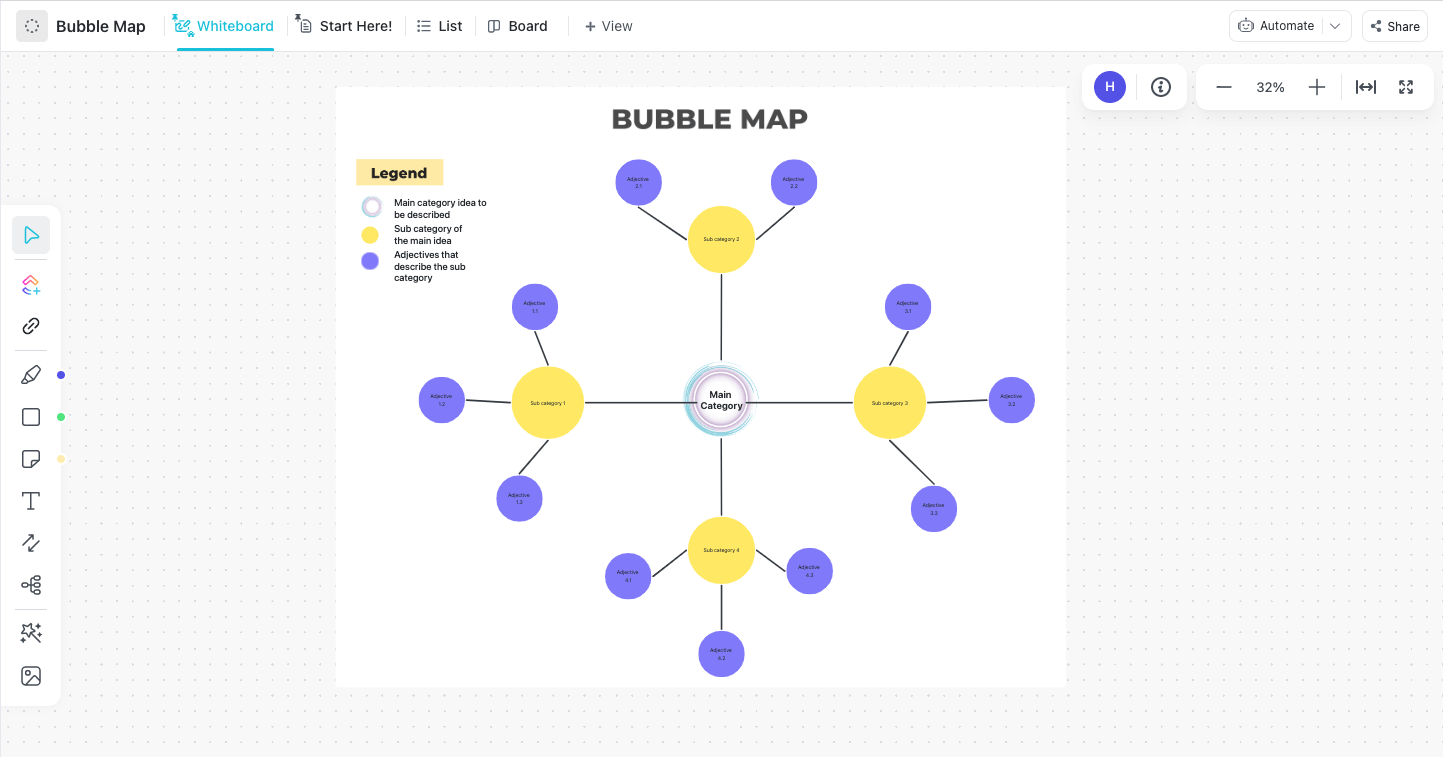

Break down the monotony by adding colors and icons to differentiate between domains in your concept map.

A trick here is to use specific colors for a specific domain , especially for complex concepts.

For example, as seen in this ClickUp Bubble Map Template , a subcategory of the main idea can be marked in yellow, an adjective to describe the subcategory in purple, and the result in green.

Pro tip💡: When you have a large amount of complex data, ClickUp’s Bubble Map Template helps you identify patterns that may go unnoticed.

You now know how to draw concept maps using ClickUp Whiteboards and pre-built templates.

Going a step further, once you create a concept map, connect it to your workflows in ClickUp’s Project Management Software .

Now, create logical pathways between tasks, which can be edited, deleted, or rearranged with a few clicks.

Pro tip💡: Consider using ClickUp’s Proofing feature to collaborate on mind maps and concept maps for your software development projects.

We recommend using ClickUp’s mind map templates to make brainstorming sessions easier. As these are customizable, they can easily be modified to create concept maps too.

The simplest one is ClickUp’s Simple Mind Map Template —as a thought-mapping tool to visualize your ideas and tasks. Drag and drop the elements, move them around, and double-click to edit the text. This template has expanding and collapsible layers for adding notes, ideas, and real-time collaboration with your team.

Read more: How to make a mind map in Word?

Visual learners: Visual learners thrive on graphical representations. Concept maps visually connect information, aiding in organization and processing.

For example, a history student visually maps key events and figures.

Kinesthetic learners: Kinesthetic learners learn by doing things. Learners can deepen their understanding by physically arranging concepts and making connections using concept mapping.

For instance, they might move labeled cards representing body systems when studying anatomy.

Auditory learners: Auditory learners soak up info through listening. Even though maps are visual, auditory learners can use them by talking through their thoughts.

For example, a literature student can use concept maps to discuss themes and motifs

Reading/Writing learners: These learners excel at processing written text. Concept maps can organize big concepts into easily readable formats and make it easy to summarize content.

For example, a psychology student might create a map summarizing key theories and proponents.

For teachers

- Promote collaboration: During a group project, teachers can ask students to collaborate on a concept map to organize their thoughts and contributions effectively

- Promote critical thinking: Students can use a concept map to illustrate the relationships between historical events or biological functions, promoting a deeper understanding of cause and effect

For students

- Ideation: Students can use a concept map template to organize their thoughts and spark creativity. For instance, when brainstorming for a renewable energy project, they can map different sources and technologies to generate new ideas

- Quick revision: Concept maps make it easy to review study material quickly. For example, if there is a history test, the concept map of important events can help refresh the key points quickly

- Strategic planning: Mapping goals and objectives helps business leaders create thorough plans. Stakeholders can use a concept map to outline long-term goals and strategies

- Project management: Concept maps clarify project details for better planning and execution. Project managers can explain the project scope, tasks, and dependencies using a concept map

- Knowledge creation and transfer: Organizations can create company policies and procedures using a concept map maker

- Patient education: Visual representations through concept maps enhance patient understanding of medical conditions, treatments, and care instructions

- Treatment analysis: Mapping symptoms, diagnoses, and treatment options to analyze and evaluate complex medical cases effectively

Create Concept Maps with ClickUp

Now that you have seen concept map examples and understand how to use them, it’s time to create your own. Even if you are a beginner, you can quickly get started with ClickUp’s pre-built customizable concept map templates .

Whether you want to adjust the layout, add or remove elements, or tweak the design to match your personal style, ClickUp provides flexibility while bringing your key concepts to life.

Maps are created in ClickUp Whiteboards that are customizable, shareable, and great for remote collaboration.

Start your concept map journey by signing up on ClickUp for free .

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. what are the four types of concept maps.

The four types of concept maps include:

- Spider maps: Where the central idea branches out to related concepts in a radial pattern

- Hierarchy maps: Showcasing the levels of authority and roles within a system

- Flowcharting: Shows a sequence of steps to show how a process progresses

- System maps: Visualizing the interconnections among various parts of a concept

2. How do you structure a concept map?

To structure a concept map effectively, start with the main concept or topic in the center. Then, you can branch out with related sub-topics or ideas and link them with lines or arrows.

3. What are the 3 components of a concept map?

The three main components of a concept map are:

- Concepts: The ideas, topics, or terms represented in circles or boxes

- Linking lines/arrows: These connect the concepts and show their relationships

- Linking phrases/words: Written on the linking lines, these phrases clarify the specific relationship between the connected concepts

Questions? Comments? Visit our Help Center for support.

Receive the latest WriteClick Newsletter updates.

Thanks for subscribing to our blog!

Please enter a valid email

- Free training & 24-hour support

- Serious about security & privacy

- 99.99% uptime the last 12 months

Advisory boards aren’t only for executives. Join the LogRocket Content Advisory Board today →

- Product Management

- Solve User-Reported Issues

- Find Issues Faster

- Optimize Conversion and Adoption

Organizing thoughts and ideas with a concept map

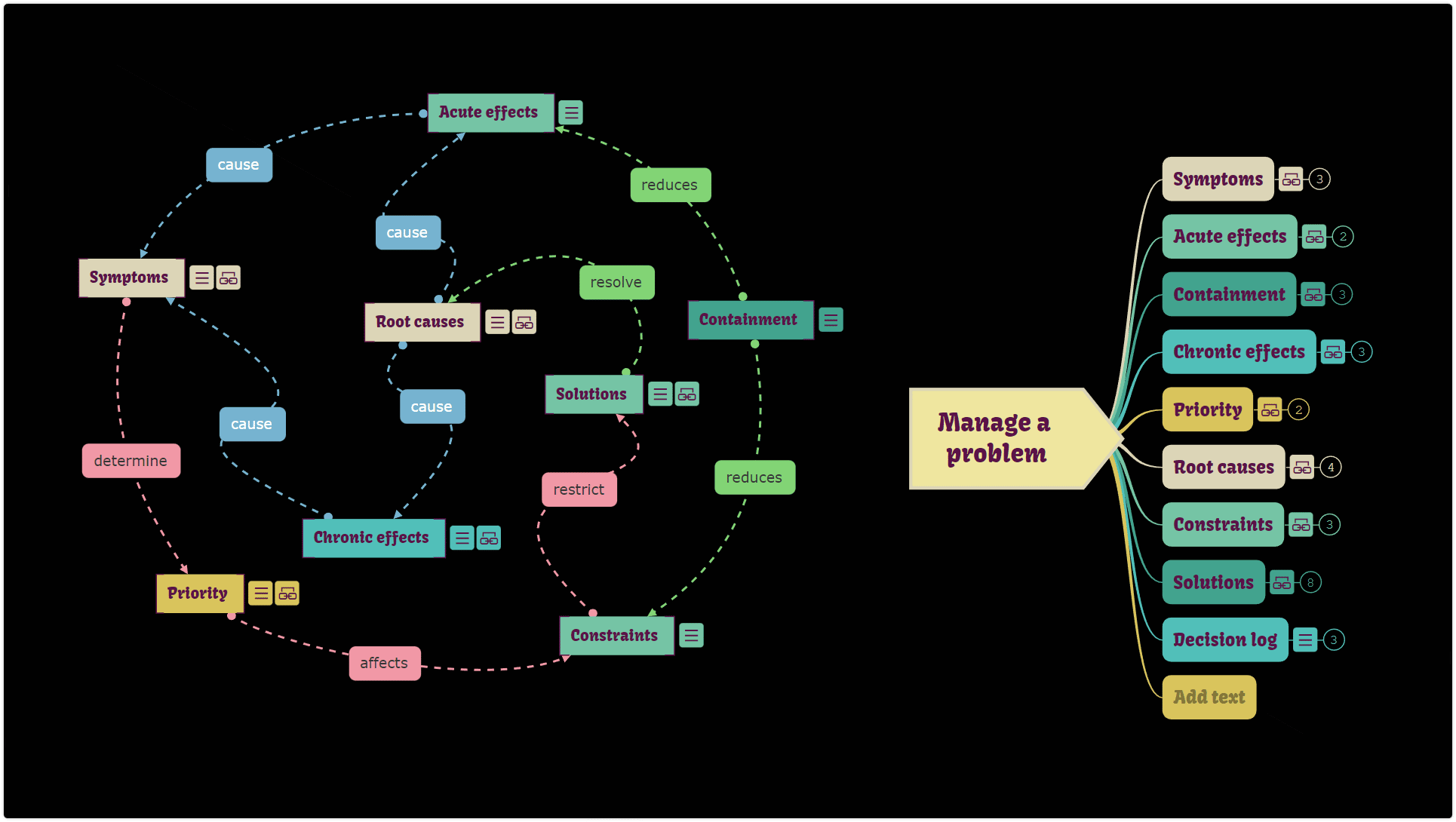

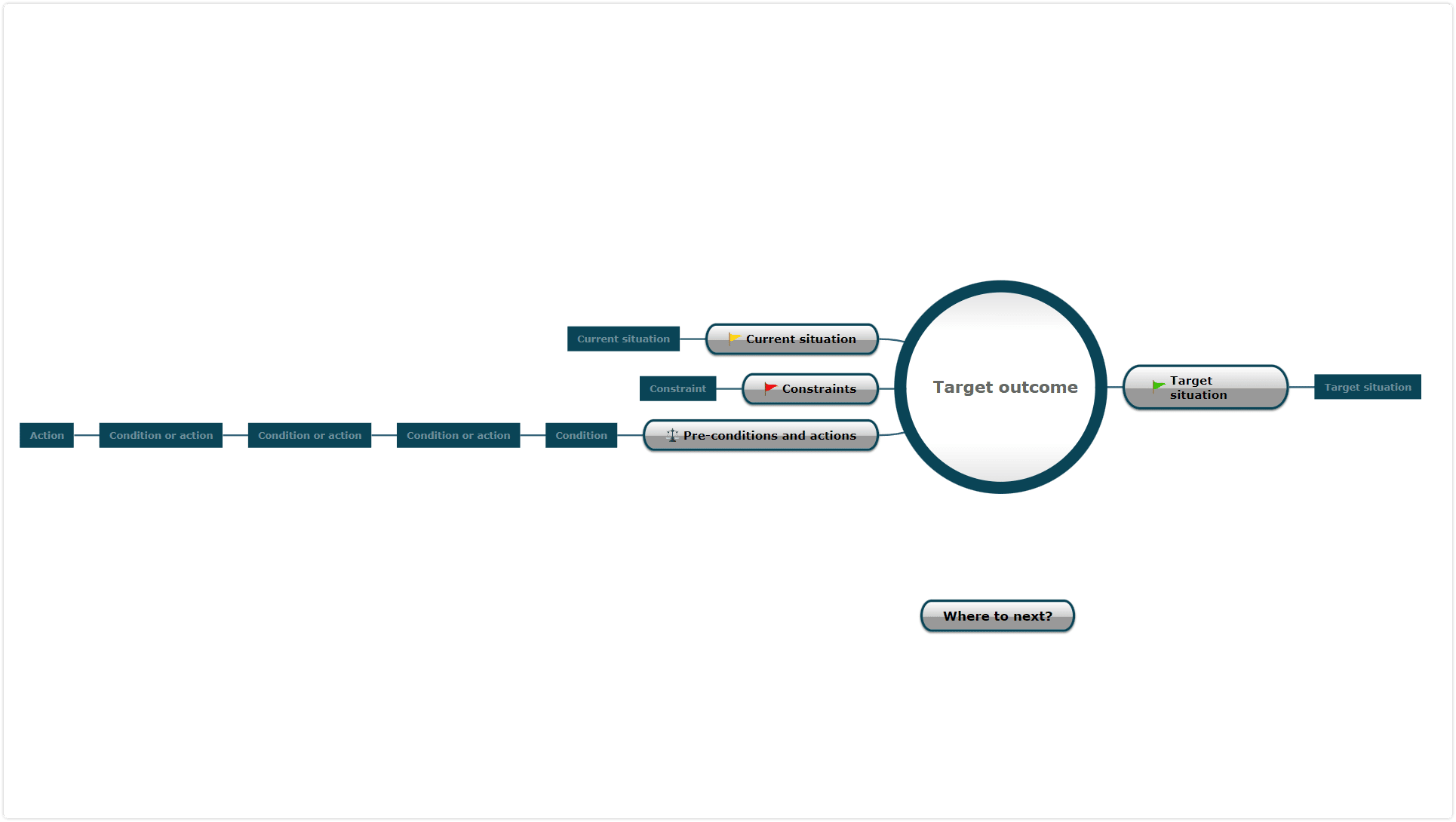

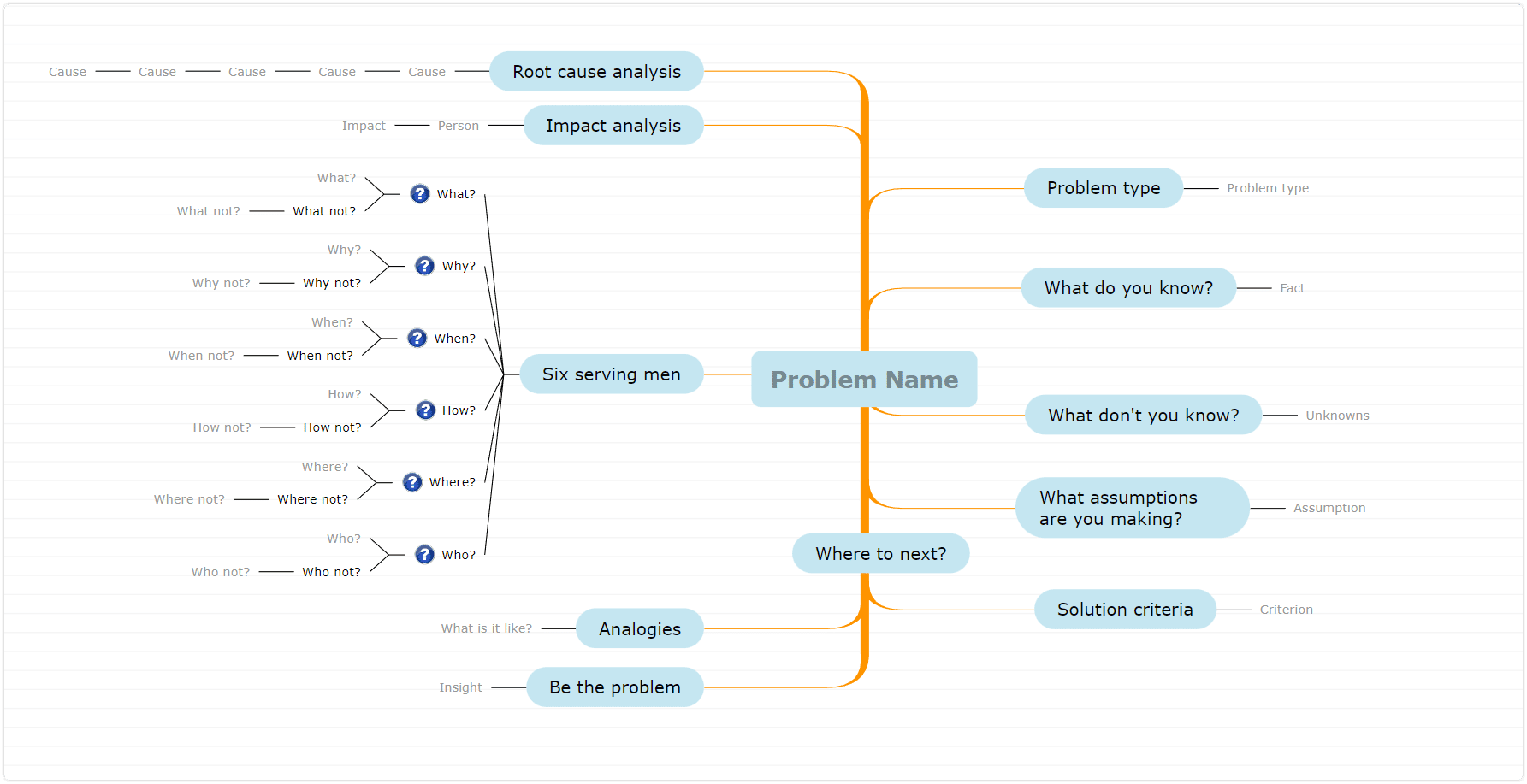

Concept mapping is a terrific way of organizing your thoughts and ideas and then crafting them into a concept. Concept maps are made up of summaries, storyboards, inspiration, requirements, notes, and tasks to represent the early stages of strategic plans that can be synthesized into to-do lists, kanban boards, project timelines, prototypes and so on (as opposed to jumping right into them, which can be more overwhelming and less effective).

In this article, I’ll explain what concept maps are, the benefits of using them in product development, how to create them and which tools to use to do so, and I’ll also share some concept map templates that you can use.

What is a concept map?

Concept mapping is the process of organizing thoughts and ideas related to a problem to be solved. A concept map is a diagram of interconnected summaries, storyboards, inspiration, requirements, notes, and tasks somewhat depicting a strategic plan (or several strategic plans) for solving said problem.

The benefits of using concept maps in product development

Concept maps help people in product teams (regardless of their role or responsibilities) make sense of their own thoughts and ideas before crafting them into some kind of concept. They’re also useful for documenting thoughts and ideas before you forget about them, as well as for exploring multiple ideas quickly, leaving no stone unturned. Because concept mapping is collaborative, they make it easy to brainstorm, discuss, and vote on next steps.

Step-by-step guide to concept mapping

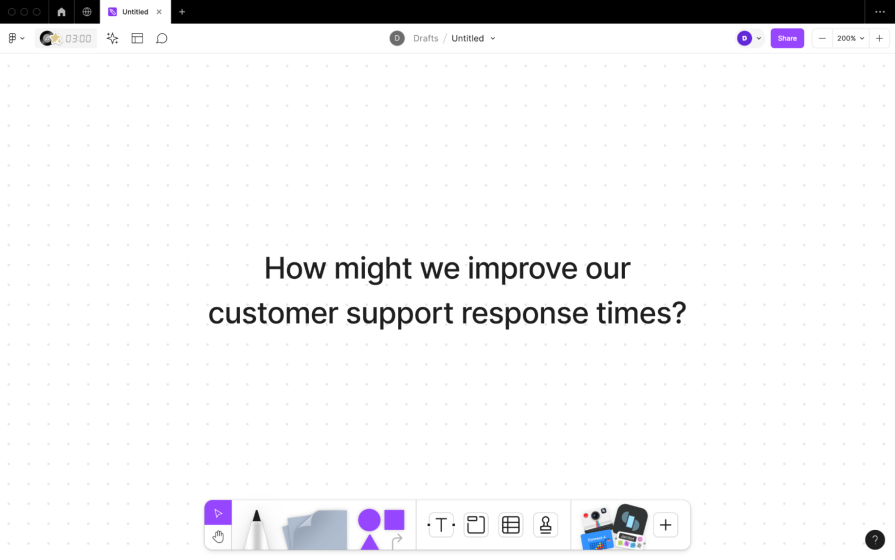

To help you get started with concept mapping, you can follow these three steps with your product team.

1. State your objective

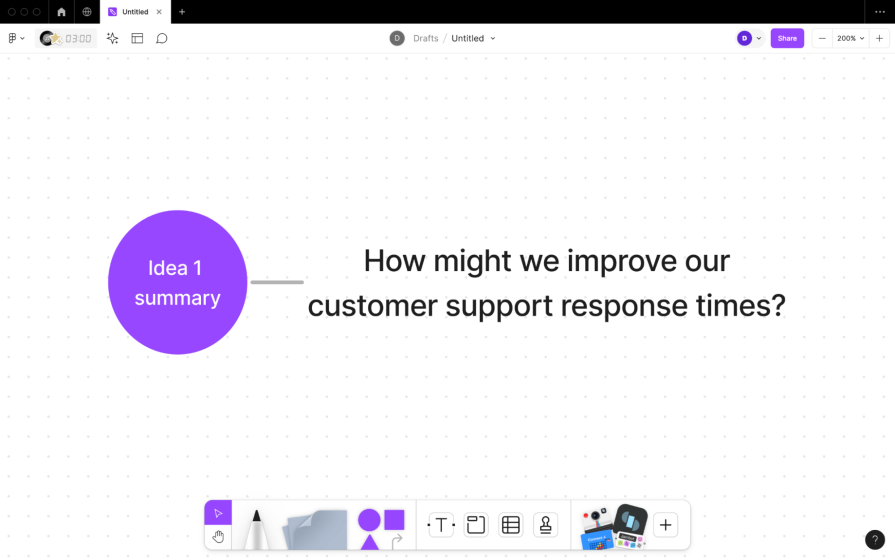

Concept maps should be purposeful and focused, so start off by stating your objective in the middle of your canvas.

If your brain goes off-topic, simply note down those thoughts and ideas elsewhere and then try to get back on track by returning to your objective..

Tip: It’s often helpful to state the objective as a question; for example, “How might we improve our customer support response times?” or “How might we make our DesignOps workflows more efficient?”

2. Run wild

This next step is a bit chaotic because it’s very likely that you’ll have a lot of thoughts and you’ll want to note them all down before you forget them, which requires not worrying so much about tidiness and organization (yet).

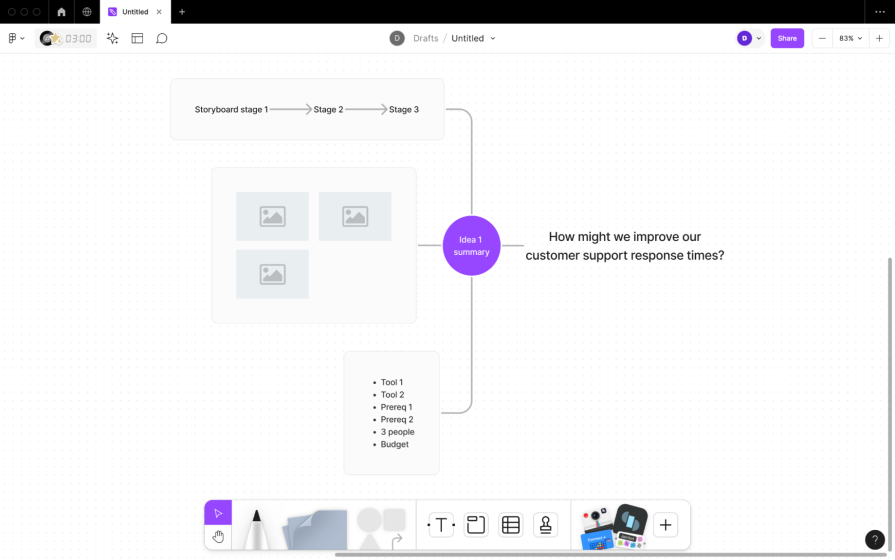

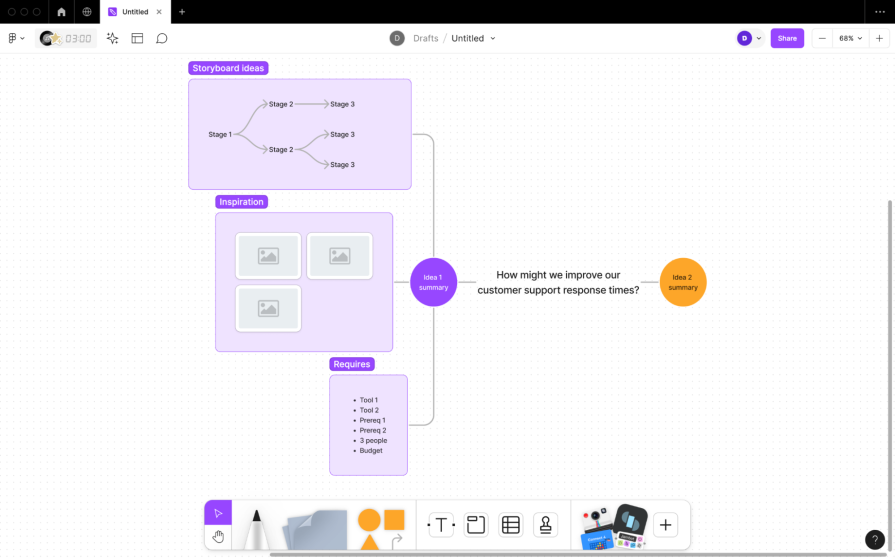

So to begin, start by summarizing one idea and linking it to your question with some sort of connector (these are sometimes called “arcs” and are shown in gray in the image below). The thoughts/ideas are sometimes called “nodes” (shown in purple):

Next, you can either summarize more ideas or develop upon the one that you just summarized using “subnodes” and arcs. Subnodes are thoughts/ideas that are related to a parent node, which you can format in any way that you see fit. For example, if a parent node summarizes a solution then its subnodes might include a storyboard of how users might use it (with its own subnodes and arrow arcs), design inspiration, and/or a list of requirements needed to build it:

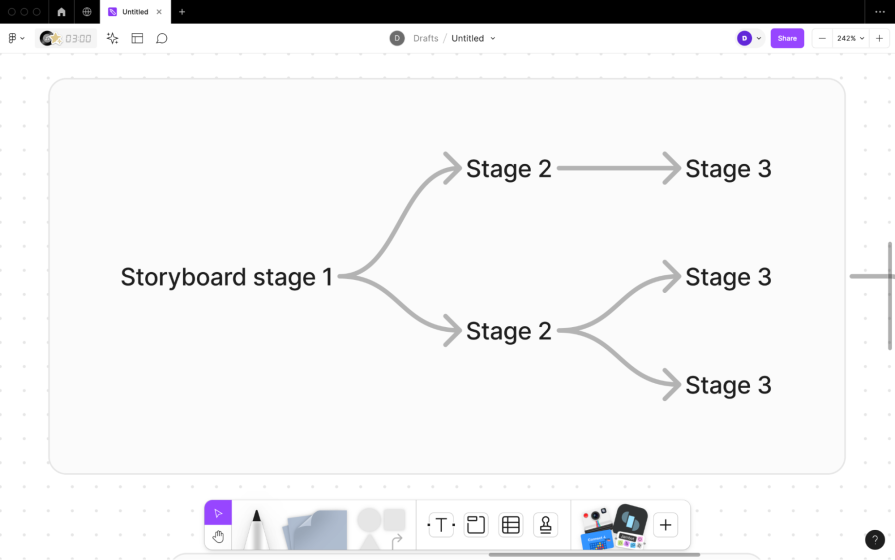

Wherever possible, single idea chains can share nodes. This is useful whenever you have multiple storyboards that share certain sequences. Simply arrow-in and/or arrow-out of the shared sequences/nodes, as shown in the image below:

3. Clarify and organize

Once you’ve exhausted your thoughts and ideas (at least for the moment), it’s time to clarify and organize. This includes moving and removing anything that wasn’t relevant after all, organizing and consolidating nodes, and making everything clearer. Doing so is especially important when collaborating in real time as your collaborators might’ve documented the same thoughts and ideas as you did.

After that, you could make your concept map even clearer and even more organized with some visual adjustments. As an added benefit, doing this will also make it more visually appealing.

Over 200k developers and product managers use LogRocket to create better digital experiences

Firstly, you could color-code your nodes. You can do this in any way that improves the clarity of your concept map, but the most common way is to color-code each idea chain on crowded concept maps:

You could use differently shaped or sized nodes, however, I find that this often makes concept maps unnecessarily more complex. At most, I tend to circle top-level nodes (if they’re small/brief) and box subnodes (with rounded corners for aesthetics of course).

Finally, I recommend labeling your nodes. As an example, a list of requirements could be labeled as “requirements.” If you’re using FigJam to make concept maps, I recommend using sections to create nodes (since they can have labels) and then creating the content inside of them:

Concept mapping tools (with templates)

I wouldn’t bother with specialized concept mapping tools because there are many tools that your product team probably already has that can facilitate concept mapping.

The most used tool for digital whiteboarding is FigJam (by Figma) and it has an official concept map template that you can use as a jumping off point. It’s worth noting that FigJam is the only digital whiteboarding tool on this list where collaborators can talk to each other with real audio in real time, which puts FigJam light years above other tools.

The second most used digital whiteboarding tool is Miro (who recently acquired InVision Freehand by the way), which is a bit more mature than FigJam, but otherwise not much different. Miro also has an official concept map template .

In third place (oddly) is Figma itself, probably because FigJam is a separate subscription from Figma. That being said, Figma is a UI design tool, so usage is heavily skewed towards designers. If you’re not a designer, then using Figma for concept mapping will be significantly more complicated. It’ll be a manual process of creating and styling the concept map, unless you use some kind of diagramming plugin or widget.

Surprisingly, Canva is also a popular choice having steered a little more towards professionals in recent years. If your team already has a subscription (probably to create graphics), it’s definitely not a bad option. You can find its concept map template here.

Final thoughts

Concept mapping can be incredibly useful to all members of a product team, regardless of their role or responsibilities. When collaborating in real time, concept mapping can even bring all styles together harmoniously. This makes ideation/collaboration more accessible, democratic, thorough, iterative, clearer, strategic, and productive.

If you’d like to tell us about your approach to brainstorming and ideation, you can do so in the comment section below. Thanks for reading!

Featured image source: IconScout

LogRocket generates product insights that lead to meaningful action

Get your teams on the same page — try LogRocket today.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- #project management

- #tools and resources

Stop guessing about your digital experience with LogRocket

Recent posts:.

Leader Spotlight: Driving demand with the digital shelf, with Marianna Zidaric

Marianna Zidaric, Senior Director of Ecommerce at Spin Master, talks about how digital might have changed the way we can reach the shopper.

How PMs can best work with UX designers

With a well-built collaborative working environment you can successfully deliver customer centric products.

Leader Spotlight: Evaluating data in aggregate, with Christina Trampota

Christina Trampota shares how looking at data in aggregate can help you understand if you are building the right product for your audience.

What is marketing myopia? Definition, causes, and solutions

Combat marketing myopia by observing market trends and by allocating sufficient resources to research, development, and marketing.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

Concept Maps

What are concept maps.

Concept maps are visual representations of information that show the relationship between ideas or concepts. They are suitable for organizing and representing knowledge in an easy-to-understand manner using shapes and lines to represent relationships visually.

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

Benefits of Concept Maps

A concept map helps you see how different ideas fit together, making complex information easier to understand. It's like laying concepts before you to see how they connect.

Enhanced understanding: Concept maps make abstract ideas concrete for quick and enhanced comprehension.

Efficient learning and recall: Concept maps help you memorize information better and make recall during exams or meetings easier.

Creativity boost: The visual layout reveals the gaps and links between concepts to foster creative thinking.

Improved problem-solving: Identifying connections between elements helps you tackle issues in a structured way.

Effective communication: Sharing concept maps makes complex topics easy for a team or audience to discuss and understand.

Key Components of Concept Maps

A concept map has three main components: nodes, links, and hierarchies.

Nodes : These are the fundamental building blocks of concept maps, represented as boxes or circles containing a concept or idea. Every node represents a distinct part of the knowledge domain under consideration.

Links : These lines connect the nodes, representing the relationships between different concepts. Each link is usually labeled with a verb or phrase describing the nature of the connection between the nodes it connects.

Hierarchies : Most concept maps have a top-down approach. They start with the most general concepts at the top of the map and branch out to more specific concepts as you move downward. This hierarchical arrangement allows for an overview at a glance and helps organize complex information effectively

Role of Concept Maps in Knowledge Representation and Cognitive Mapping

Knowledge representation converts complex concepts, facts, and information into a structured, easily understandable format. Concept maps visually represent knowledge in an organized way to help with comprehension and knowledge retention.

Cognitive mapping is the mental process that helps us acquire, code, store, recall, and decode information about our environment's relative attributes. It's how we form and recall mental "maps" of our world.

Concept maps bring knowledge representation and the cognitive mapping process together. They visually structure knowledge and thereby mirror how our brains naturally work. Our minds tend to create "maps" or networks of related information; concept maps essentially externalize this process. In doing so, they help us understand and absorb complex information more effectively.

Benefits and Applications of Concept Maps

Concept maps are remarkably versatile tools with applications in various domains, including design , education, business, and research. Let's explore some of the key benefits and applications of concept maps.

Benefits of Concept Maps Across Different Domains

Education : Concept maps are instrumental in fostering deep learning among students. They encourage learners to connect new information with existing knowledge, promoting better comprehension and retention. Teachers can also use concept maps to assess students' understanding of a topic and identify gaps in knowledge.

Business : In the corporate world, concept maps are frequently used for strategic planning, project management, and knowledge management. They facilitate communication of complex ideas, promote collaboration, and help identify potential risks or opportunities.

Research : Concept maps are invaluable in organizing and visualizing the complexities of research. Researchers can use them to map out theories, hypotheses, and experimental designs to see connections or gaps in their work.

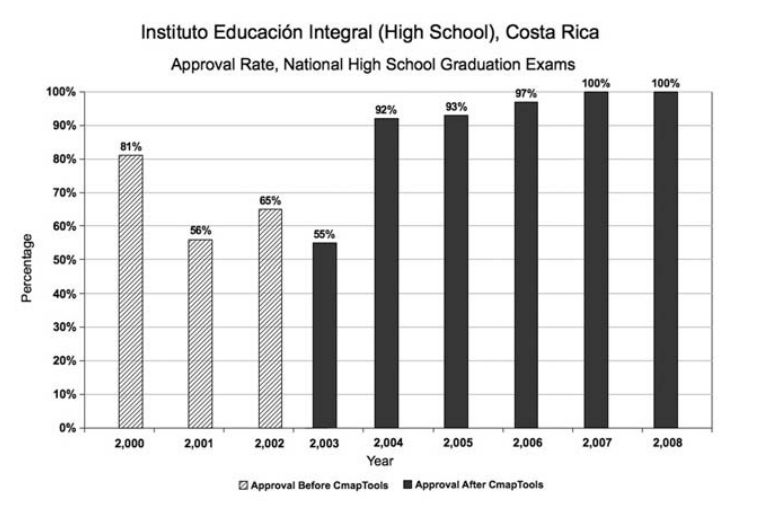

Real-World Example of Concept Maps

Concept maps have been effectively used in diverse contexts. Here’s an example:

In his book, “ Learning, Creating, and Using Knowledge ,” Joseph D. Novak shares how a high school in Costa Rica started using concept maps in all classes to teach and test students. Because of this, in just four years, the percentage of students passing the national high school graduation exam went up from 65% to a perfect 100%.

© Learning, Creating, and Using Knowledge, Fair Use

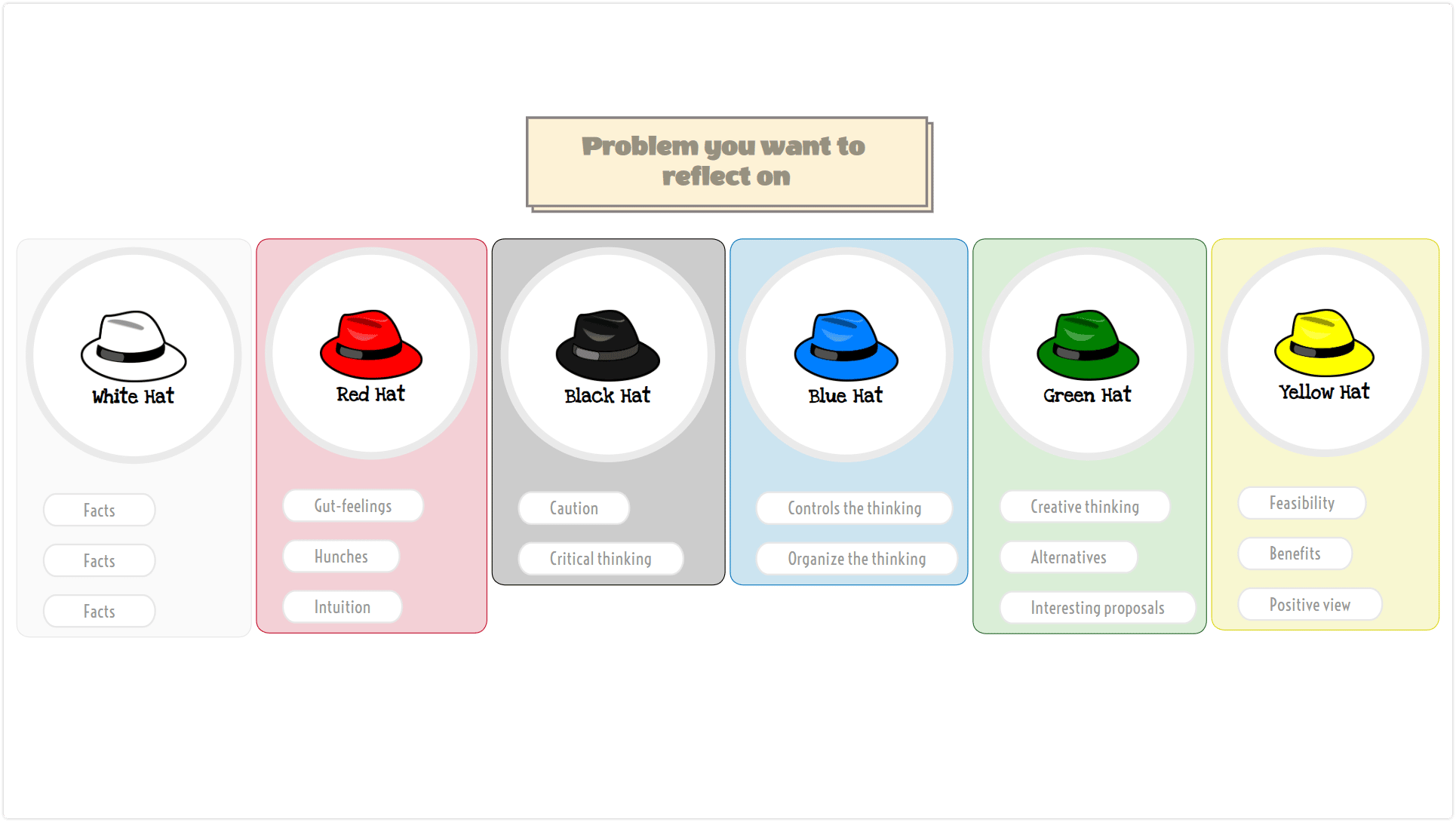

Applications of Concept Maps in Problem-Solving, Decision-Making, and Creativity Enhancement

Concept maps offer an effective way to understand and navigate the processes of problem-solving, decision-making, and creativity enhancement. This is thanks to their inherent flexibility and visual appeal.

Potential applications of concept maps in problem-solving:

Visualize the problem : Concept maps can help break down complex problems into smaller, manageable parts. They allow a clear understanding of the issue at hand.

Identify relationships : They enable users to identify relationships and connections between different aspects of the problem that they may have overlooked otherwise.

Highlight knowledge gaps : Concept maps can expose areas that need more information or exploration to guide the design thinking process in the right direction.

Watch this video to learn more about design thinking and its five phases.

- Transcript loading…

Hasso-Platner Institute Panorama

Ludwig Wilhelm Wall, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Potential applications of concept maps in decision-making:

Compare options : Concept maps enable visual comparison and contrast of different options. They make the decision-making process more transparent and logical.

Analyze risks and benefits : Concept maps can highlight each option's potential risks and benefits.

Understand consequences : Concept maps can help visualize each decision's potential outcomes, promoting forward-thinking and strategic decision-making.

Potential applications of concept maps in creativity enhancement:

Promote divergent thinking : Concept maps encourage visual thinking and stimulate creativity.

Act as a brainstorming tool : You can use concept maps to be the focus of brainstorming sessions.

Nurture innovation : They can serve as a platform for integrating existing knowledge with innovative solutions and ideas.

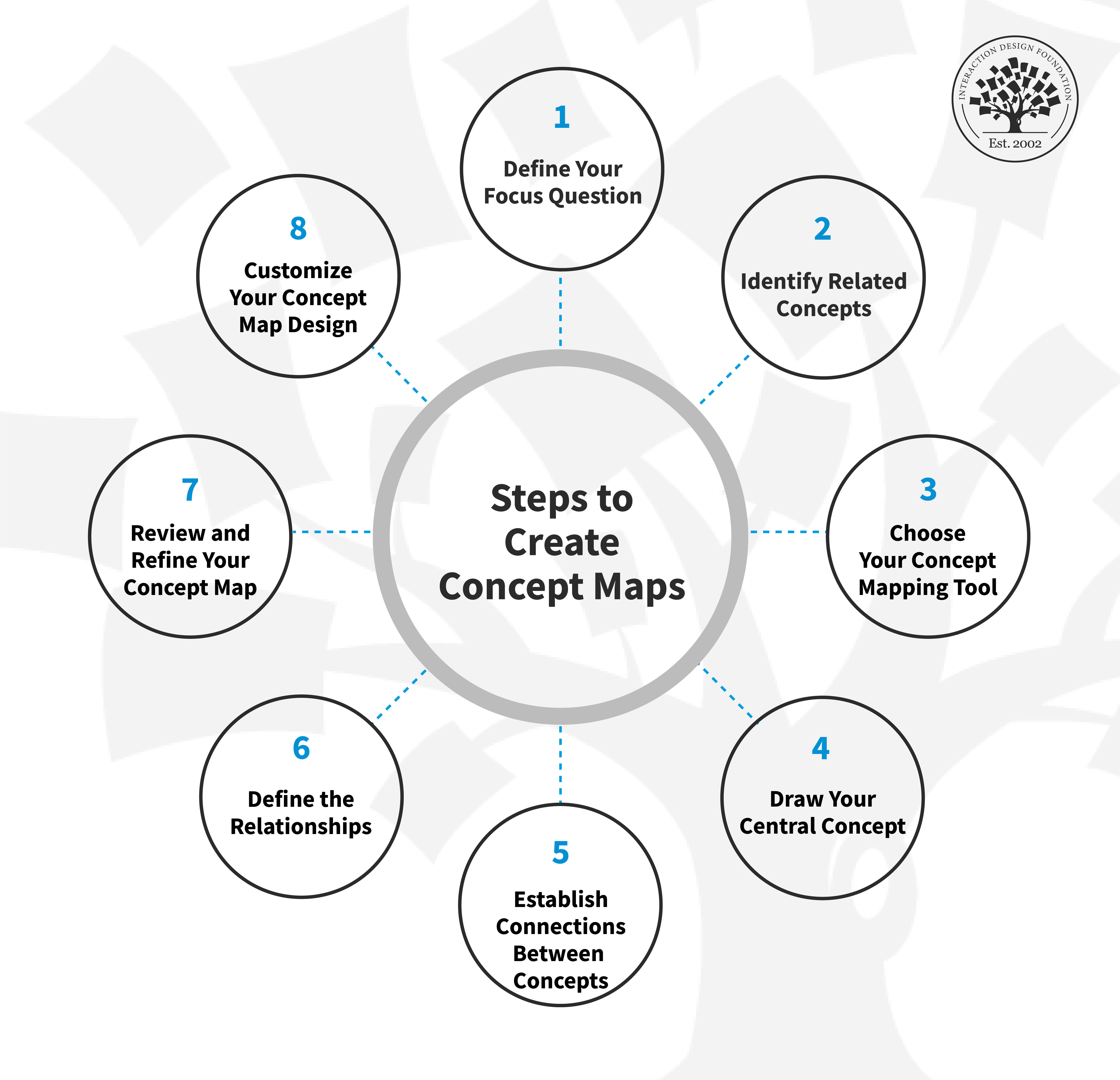

How to Create Effective Concept Maps

Creating an effective concept map isn't difficult, but it does require some strategic thinking and a touch of creativity.

Here's how they work:

You start with a central concept. This could be anything you're thinking about. It may be a topic you're studying, a project you're planning, or even a big question you're trying to answer.

You then identify the major related ideas or subtopics that connect to this main concept. You draw lines from the central idea to these related ideas.

You might have more specific ideas or details for each subtopic. You draw more lines to show these connections.

You can write words or phrases on each line explaining how the ideas connect.

Here's a step-by-step guide to creating well-structured and visually appealing concept maps to give you a better idea.

Steps to Create Concept Maps

Step 1: Define Your Focus Question

Start by defining your focus question, whether it's a business problem, a research question, or a social issue. It's important to narrow it down to a core concept. This ensures that your map remains organized and easy to understand.

Step 2: Identify Related Concepts

Brainstorm and list all the concepts or ideas related to your focus questions. Having this 'parking lot' of ideas ready before you begin designing your map is beneficial. It saves you time and potential restructuring later on.

Step 3: Choose Your Concept Mapping Tool

You have two main options when it comes to creating your concept map: traditional tools (pen and paper cards, sticky notes, whiteboard) or a digital concept mapping application. Digital diagramming tools like Visme , LucidChart , Miro , and Mural offer advantages like easy collaboration, limitless space for complex maps, and the ability to customize templates and animations.

Step 4: Draw Your Central Concept

Whether you're drawing your concept map by hand or using a digital tool, always begin with your key concept at the top or center of your map. This allows for a clear hierarchical structure.

Step 5: Establish Connections Between Concepts

Now, it's time to connect your ideas. Begin with broader concepts, gradually moving to more specific ones. You can use arrows to indicate the direction of relationships between concepts to make it easier for viewers to understand the map's propositions.

Step 6: Define the Relationships

This step involves adding text to your lines or arrows to define the concepts' relationships clearly. Keep this text brief and straightforward to maintain a clean and clutter-free visualization.

Step 7: Review and Refine Your Concept Map

Now that your concept map has taken shape, review it carefully. Look for potential improvements, redundancies, or missed ideas. Feel free to rearrange nodes or add more cross-links if needed.

Step 8: Customize Your Concept Map Design

All that’s left is to save your work in a form that’s easily accessible for future reference. Take pictures if you’re working offline, and name and organize your files properly. Remember to add the date and any context that someone outside your group might need to understand the map fully.

If you plan to share or present your concept map to business stakeholders, you must polish it up. This can be as simple as adding a bold header or tweaking the colors and fonts to match your brand's visual identity. Businesses can consider adding their company logo to increase brand awareness. This can be particularly helpful if they want to share the concept map on social media or embed it on their website.

Step 9: Iterate

Concept maps are a valuable tool for organizing thoughts and explaining complex ideas. However, things may change depending on the subject of your concept map. Creating a concept map is an iterative process of understanding. It may require adjustments and revisions based on new research and insights.

Best Practices for Concept Mapping

Following the step-by-step guide above will enable you to construct a competent concept map for almost any situation. However, if you want to make your concept map truly exceptional, consider these tips and best practices:

1. Focus on One Idea

While having multiple key concepts in your concept map is possible, it's advisable not to use them. Your key concept originates from your focal question. It is the starting point from which all other ideas branch out in your hierarchical concept map.

Incorporating more than one key concept could lead to an overly complex and confusing diagram for your audience. Stick to one key concept and create separate concept maps for each if you have multiple key concepts.

2. Cluster Similar Concepts

If your general concepts branch out into too many specific ones, consider grouping related ideas under a sub-concept.

For instance, you can construct a concept map about "healthy living." You could have two main groups: "physical health" and "mental health." Within these, you could further categorize.

For physical health, you might have sub-groups like "exercise" and "diet."

For mental health, "stress management" and "emotional well-being" could be sub-groups.

Grouping similar ideas will make your concept map neater, less cluttered, and more digestible for readers.

3. Use Color-Coding

Colors can help differentiate the different domains in your concept map. This not only enhances readability but also aids in retaining information for longer periods by associating each domain with a distinct color. Be sure to use colors in a meaningful way rather than using them just for their sake.

For example, you can color-code renewable energy sources in various green shades while using red for non-renewable sources. Use these colors consistently to prevent confusion. But be sure to provide ways of identifying key components since color alone can cause accessibility and display problems. (Red on one screen could be magenta on another, plus red-green color blindness is fairly common.)

4. Incorporate Images and Icons

Consider enhancing the text with images or icons to make your concept map more engaging.

For instance, you can use outline icons to represent the concepts of "coffee beans" and "hot water." This method promotes faster learning and better recall, as the brain can form stronger associations with icons and words than with plain text.

5. Use Linking Words

We find linking words on the lines that connect different objects in a concept map. When you add linking words or phrases to clarify the relationships between different concepts, make sure they are logical. This will allow readers to form meaningful sentences from the linking words and the two concepts.

In some cases, you may not need to use any words. You can use symbols like + or - to indicate the addition or subtraction of ideas.

6. Make It Interactive

If you plan to share your concept map online, consider making it interactive to engage readers.

For instance, you can allow users to collapse and expand notes. You might also include links to your concept maps, leading readers to external web pages for detailed information.

Additionally, consider inserting additional resources and further reading at the bottom of your concept map or linking to various online sources used to gather information for your diagram.

5 Tips For Enhancing Readability And Clarity In Concept Maps

Creating a concept map is only the first step; ensuring it is easy to understand and digest is another crucial step to pay attention to. Clear concept maps with high readability will ensure effective communication. Here are some key points to consider:

1. Clear hierarchy

Organize your ideas in a clear and logical visual hierarchy. Your key concept should be the primary focus, with other ideas branching out according to their importance and relevance.

Here’s an example of how you can implement hierarchy in UX design that you can apply to your concept maps to make them easier to use.

2. Appropriate spacing

Ensure adequate space between your ideas to avoid overcrowding. This will help readers distinguish between concepts and avoid confusion.

3. Consistent layout

Consistency in your layout, such as using shapes, colors, and fonts, will enhance readability. Make sure that similar concepts are visually unified.

4. Use of colors

Use different colors to distinguish between various levels or types of concepts. Striking a balance will bring about improved clarity.

5. Legible fonts

Ensure your fonts are easy to read. Avoid overly stylized fonts or small text sizes, which can detract from the readability of your concept map.

Integrating into Workflows and Learning Environments

1. daily planning.

Use concept maps as a planning tool. Start with your main goal for the day in the center and branch out with tasks and subtasks.

2. Meeting summaries

After a meeting, create a concept map to summarize key points discussed, decisions made, and action items.

3. Learning and study

For students, concept maps can be invaluable in summarizing chapters, understanding complex topics, or revising for exams. They can turn dense textual information into a visual snapshot, making it easier to recall.

4. Project management

Concept maps can provide a visual overview of a project, showcasing the different phases, tasks, responsibilities, and timelines.

5. Collaborative brainstorming

In team environments, digital concept mapping tools allow real-time collaboration. This way, team members can contribute simultaneously, creating a comprehensive map with diverse perspectives.

6. Integration with digital tools

Ensure that your concept mapping tool integrates with other platforms you use, be it task management systems, cloud storage, or note-taking apps. This seamless integration ensures you can easily share and make the maps accessible.

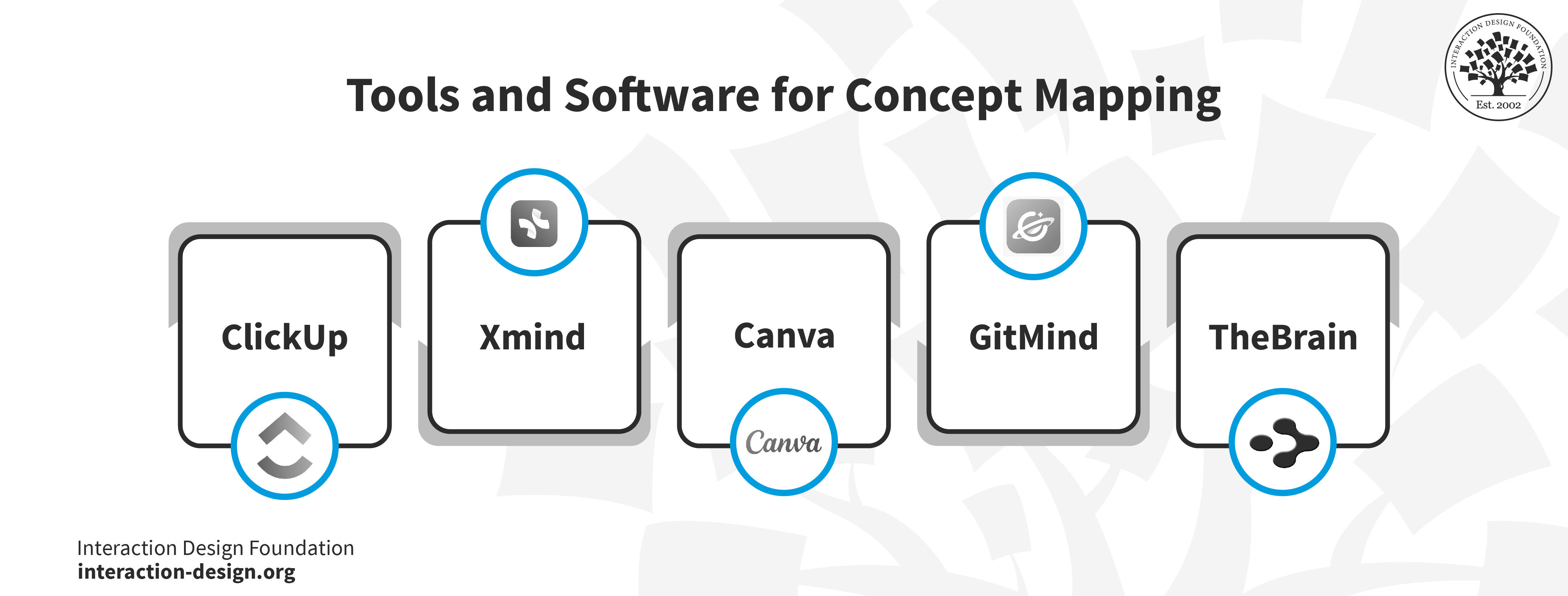

Tools and Software for Concept Mapping

When it comes to translating your ideas, plans, or projects into a visual format, concept mapping tools and software offer a range of solutions. With the surge in remote work and online collaboration, these tools have become essential for organizations and individuals. Let's take a closer look at some of the top contenders in this space, including factors like key features, presentation mode, and collaboration features.

© Clickup, Fair Use

ClickUp is an all-in-one productivity platform with several views to visualize ideas and tasks. It offers some powerful collaboration tools, such as mind maps and whiteboards, to help keep cross-functional teams updated, whether they are working in real-time or asynchronously.

Features and functionalities of ClickUp include:

Over 1,000 integrations with other work tools

Detailed online help center, webinars, and support

A template library that expedites the creation process

Reporting and dashboards for an instant overview of your work

Multiple views for various project styles

50+ task automation to streamline workflows

Unique features of ClickUp:

Real-time collaboration with Docs

Customizable task statuses for project needs

Multiple assignees for tasks for transparency

Limitations:

The sheer number of features can make it challenging for new users

Not all views are available in the mobile app

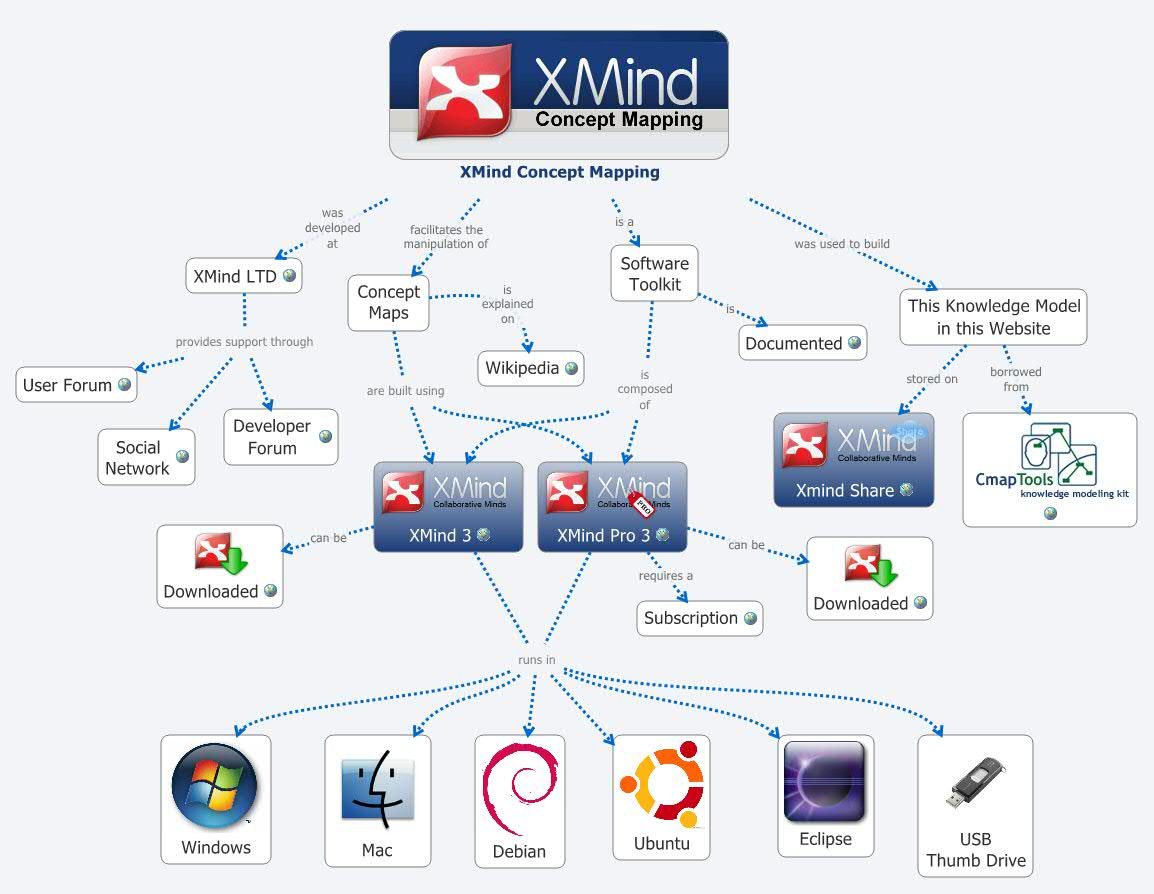

© Xmind, Fair Use

XMind is a concept mapping software that offers various map types and is compatible with Windows and Mac OS.

Features and functionalities of Xmind include:

Support for various formats, including PNG, PDF, SVG, and more

Map Shot to adjust the format for displaying and viewing

Tree Table for presenting topics with nested rectangles

Unique feature of Xmind:

Smart Color Theme for a consistent look and feel

It lacks project or task management features

© GitMind, Fair Use

GitMind is an easy-to-use concept map maker software that offers advanced features like outlining, shape customization, shared editing, and exporting.

Features and functionalities of GitMind include:

Format painter to copy all formats of a first node to the second node

A global search to find concept maps or mind maps by keywords

Relationships to connect two nodes on a concept map

Unique feature of GitMind:

Concept map generator with an outline mode

Not equipped with project management tools

Limited scalability for larger teams

© Canva, Fair Use

Canva is an online graphic design software that allows anyone to create stunning visuals and designs, including concept maps.

Features and functionalities of Canva include:

Image enhancer to correct photos

Online video recorder to help explain complex concepts

Grid designs for photos and other design elements

Unique feature of Canva:

Dynamic messaging through text animations

Multiple file downloads are automatically compressed into a zip file

5. TheBrain

© TheBrain, Fair Use

TheBrain is a concept map maker package that helps users organize their thoughts and ideas in an interactive mind map format.

Features and functionalities of TheBrain include:

Desktop, mobile, and browser platform support

Connected topics to find related information

Document tags with priority indicators

Unique feature of TheBrain:

Events and reminder attachments

Not scalable to build powerful concept map templates

Lacks collaboration tools for teams

Consider your specific needs and each software program's unique features when choosing a concept mapping tool. Whether you have a small team or one with hundreds, there's a tool that can help you visualize information and connect ideas effectively.

Collaborative Concept Mapping

Collaborative concept mapping harnesses the collective intellect of a group, enabling participants to construct a shared understanding of a topic. Let's explore its benefits:

Benefits of collaborative concept mapping

1. fostering teamwork.

Working together on a concept map requires mutual respect, understanding, and communication among team members. This process helps build trust and reinforces the spirit of collaboration.

2. Sharing Knowledge

Each participant brings a unique perspective and information. Integrating these diverse viewpoints into one map generates a richer, more comprehensive understanding of the topic.

3. Combating Cognitive Biases

When multiple individuals collaborate, it's easier to challenge and rectify individual cognitive biases , which leads to a more objective and balanced representation of information.

4. Enhancing Retention

The act of discussing, debating, and then representing ideas in a visual format can significantly improve memory retention.

Techniques and Tools for Collaborative Concept Mapping

You can employ certain tools and techniques to enhance collaboration in concept mapping:

1. Brainstorming Sessions

Before beginning the mapping process, have a brainstorming session. This allows all team members to voice their perspectives, ensuring inclusivity.

2. Real-time editing

Tools like Google Docs , ClickUp , and GitMind allow multiple users to edit concept maps in real time, ensuring that changes are immediately visible to all participants.

3. Feedback loops

Encourage team members to critique and review the map at various stages. Iterative feedback ensures the final product is well-rounded and comprehensive.

4. Use templates

Starting with a template can expedite the mapping process. Many digital tools offer customizable templates tailored for different purposes.

5. Integration with other tools

Some advanced mapping tools integrate with task management and communication platforms. This facilitates seamless sharing and discussion of the map content.

Example of Successful Collaborative Concept Mapping Project

Below, you will have the chance to take a peek into a fascinating study involving the real-life application and benefits of Concept Mapping. We’ve summarized it below in easy-to-grasp terms, just for you.

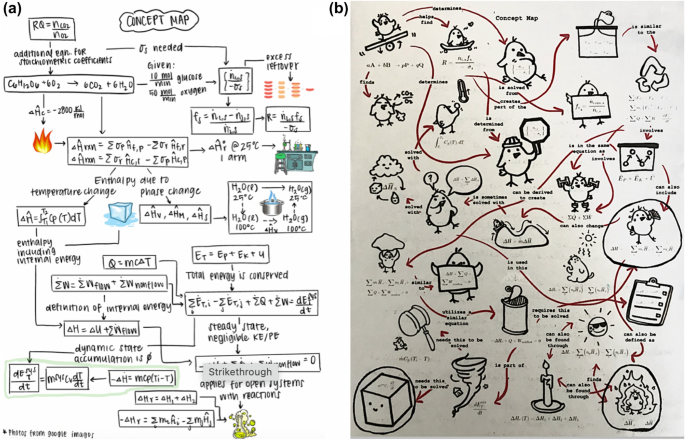

Study : Improving Medical Student Learning with Concept Maps

Background and purpose.

This study aimed to see if concept maps could help medical students in India learn better.

The study involved two groups of third-year medical students. The team conducted the study in two parts. In the first part, students took a test to see how much they knew about a topic. Then, they were taught about tuberculosis using a concept map. After this, another test took place. In the second part of the study, the students were asked how they felt about using the concept map. The team compared the scores from the two tests using a statistical method called the Wilcoxon test.

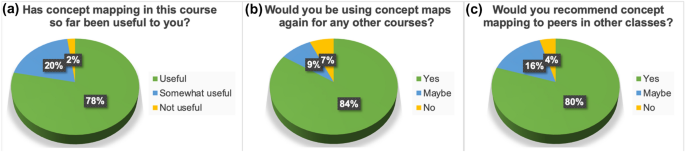

The scores on the test after using the concept map were higher than before (an average score of 10 compared to 4, which is statistically significant at P < .0001). More than half of the students got a perfect score on the test after using the concept map, while none of them did on the first test. When asked about using the concept map, 82.09% of students liked it.

The study found that concept maps are a helpful tool for teaching and learning for medical students. They can be used to help students understand complex topics more easily. More use of concept maps could help improve student learning.

© National Center for Biotechnology Information, Fair Use

Advanced Concepts in Concept Mapping

Concept mapping has evolved considerably since its inception. Academic research, technological advancements, and the increasing complexity of subjects are at the forefront of this evolution.

As we look deeper into the emerging sophisticated techniques, we find innovations such as concept linking, concept evolution, and the development of ontologies. Additionally, the future of concept mapping holds exciting prospects as emerging trends reshape the process of creating concept maps.

Advanced Techniques and Concepts

1. concept linking.

Concept linking is a way to connect related pieces of information by finding shared ideas within them. It's like seeing which things often appear together in a document. A concept is the main idea or thing that's important in that situation.

2. Concept Evolution

Advanced mapping tools now offer the capability to track the evolution of a concept over time. This dynamic visualization can show how an idea has changed, grown, or diminished. It is useful for projects spanning long durations or evolving subjects, like technology trends or scientific theories.

3. Ontologies

An ontology captures knowledge about entities and their relationships in a specific domain, while concept maps are visual tools. Both help in understanding complex topics. Ontology sets the groundwork, and concept maps visualize it.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

1. Integration with Artificial Intelligence

As AI continues to progress, there's potential for it to analyze large volumes of data and automatically generate concept maps, uncovering relationships that the human eye might miss. Additionally, AI can offer real-time suggestions to enhance the quality and comprehensiveness of concept maps.

2. Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR) in Concept Mapping

Imagine wearing VR glasses and walking through a 3D concept map, exploring ideas like physical objects in a room. AR and VR offer opportunities to make concept mapping a more immersive experience, thereby enhancing comprehension and retention.

3. Collaborative Real-time Mapping