Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 12 August 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to write a literature review in 6 steps

What is a literature review?

How to write a literature review, 1. determine the purpose of your literature review, 2. do an extensive search, 3. evaluate and select literature, 4. analyze the literature, 5. plan the structure of your literature review, 6. write your literature review, other resources to help you write a successful literature review, frequently asked questions about writing a literature review, related articles.

A literature review is an assessment of the sources in a chosen topic of research.

A good literature review does not just summarize sources. It analyzes the state of the field on a given topic and creates a scholarly foundation for you to make your own intervention. It demonstrates to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.

In a thesis, a literature review is part of the introduction, but it can also be a separate section. In research papers, a literature review may have its own section or it may be integrated into the introduction, depending on the field.

➡️ Our guide on what is a literature review covers additional basics about literature reviews.

- Identify the main purpose of the literature review.

- Do extensive research.

- Evaluate and select relevant sources.

- Analyze the sources.

- Plan a structure.

- Write the review.

In this section, we review each step of the process of creating a literature review.

In the first step, make sure you know specifically what the assignment is and what form your literature review should take. Read your assignment carefully and seek clarification from your professor or instructor if needed. You should be able to answer the following questions:

- How many sources do I need to include?

- What types of sources should I review?

- Should I evaluate the sources?

- Should I summarize, synthesize or critique sources?

- Do I need to provide any definitions or background information?

In addition to that, be aware that the narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to get a good overview of the topic.

Now you need to find out what has been written on the topic and search for literature related to your research topic. Make sure to select appropriate source material, which means using academic or scholarly sources , including books, reports, journal articles , government documents and web resources.

➡️ If you’re unsure about how to tell if a source is scholarly, take a look at our guide on how to identify a scholarly source .

Come up with a list of relevant keywords and then start your search with your institution's library catalog, and extend it to other useful databases and academic search engines like:

- Google Scholar

- Science.gov

➡️ Our guide on how to collect data for your thesis might be helpful at this stage of your research as well as the top list of academic search engines .

Once you find a useful article, check out the reference list. It should provide you with even more relevant sources. Also, keep a note of the:

- authors' names

- page numbers

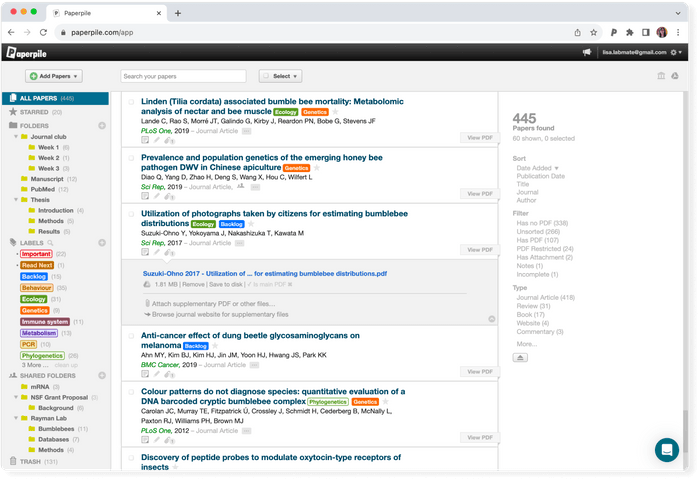

Keeping track of the bibliographic information for each source will save you time when you’re ready to create citations. You could also use a reference manager like Paperpile to automatically save, manage, and cite your references.

Read the literature. You will most likely not be able to read absolutely everything that is out there on the topic. Therefore, read the abstract first to determine whether the rest of the source is worth your time. If the source is relevant for your topic:

- Read it critically.

- Look for the main arguments.

- Take notes as you read.

- Organize your notes using a table, mind map, or other technique.

Now you are ready to analyze the literature you have gathered. While your are working on your analysis, you should ask the following questions:

- What are the key terms, concepts and problems addressed by the author?

- How is this source relevant for my specific topic?

- How is the article structured? What are the major trends and findings?

- What are the conclusions of the study?

- How are the results presented? Is the source credible?

- When comparing different sources, how do they relate to each other? What are the similarities, what are the differences?

- Does the study help me understand the topic better?

- Are there any gaps in the research that need to be filled? How can I further my research as a result of the review?

Tip: Decide on the structure of your literature review before you start writing.

There are various ways to organize your literature review:

- Chronological method : Writing in the chronological method means you are presenting the materials according to when they were published. Follow this approach only if a clear path of research can be identified.

- Thematic review : A thematic review of literature is organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time.

- Publication-based : You can order your sources by publication, if the way you present the order of your sources demonstrates a more important trend. This is the case when a progression revealed from study to study and the practices of researchers have changed and adapted due to the new revelations.

- Methodological approach : A methodological approach focuses on the methods used by the researcher. If you have used sources from different disciplines that use a variety of research methods, you might want to compare the results in light of the different methods and discuss how the topic has been approached from different sides.

Regardless of the structure you chose, a review should always include the following three sections:

- An introduction, which should give the reader an outline of why you are writing the review and explain the relevance of the topic.

- A body, which divides your literature review into different sections. Write in well-structured paragraphs, use transitions and topic sentences and critically analyze each source for how it contributes to the themes you are researching.

- A conclusion , which summarizes the key findings, the main agreements and disagreements in the literature, your overall perspective, and any gaps or areas for further research.

➡️ If your literature review is part of a longer paper, visit our guide on what is a research paper for additional tips.

➡️ UNC writing center: Literature reviews

➡️ How to write a literature review in 3 steps

➡️ How to write a literature review in 30 minutes or less

The goal of a literature review is to asses the state of the field on a given topic in preparation for making an intervention.

A literature review should have its own independent section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where it can be found, and address this section as “Literature Review.”

There is no set amount of words for a literature review; the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, then it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, then it will be short.

Most research papers include a literature review. By assessing the available sources in your field of research, you will be able to make a more confident argument about the topic.

Literature reviews are most commonly found in theses and dissertations. However, you find them in research papers as well.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

How to Conduct a Literature Review: A Guide for Graduate Students

- Let's Get Started!

- Traditional or Narrative Reviews

- Systematic Reviews

- Typology of Reviews

- Literature Review Resources

- Developing a Search Strategy

- What Literature to Search

- Where to Search: Indexes and Databases

- Finding articles: Libkey Nomad

- Finding Dissertations and Theses

- Extending Your Searching with Citation Chains

- Forward Citation Chains - Cited Reference Searching

- Keeping up with the Literature

- Managing Your References

- Need More Information?

Bookmark This Guide!

https://instr.iastate.libguides.com/gradlitrev

Where to Get Help

Librarians at ISU are subject experts who can help with your research and course needs. There are experts available for every discipline at ISU who are ready to assist you with your information needs!

What we do:

- Answer questions via phone, chat and in-person

- Consult with student and faculty researchers on request

- Purchase materials for the collection

- Teach instruction session for ISU courses

- Support faculty getting ready for promotion & tenure reviews

- Help with data management plans

Find Your Librarian

“Google can bring you back 100,000 answers. A librarian can bring you back the right one.” - Neil Gaiman

The literature review is an important part of your thesis or dissertation. It is a survey of existing literature that provides context for your research contribution, and demonstrates your subject knowledge. It is also the way to tell the story of how your research extends knowledge in your field.

The first step to writing a successful literature review is knowing how to find and evaluate literature in your field. This guide is designed to introduce you to tools and give you skills you can use to effectively find the resources needed for your literature review.

Before getting started, familiarize yourself with some essential resources provided by the Graduate College:

- Dissertation and Thesis Information

- Center for Communication Excellence

- Graduate College Handbook

Below are some questions that you can discuss with your advisor as you begin your research:

Questions to ask as you think about your literature review:

What is my research question.

Choosing a valid research question is something you will need to discuss with your academic advisor and/or POS committee. Ideas for your topic may come from your coursework, lab rotations, or work as a research assistant. Having a specific research topic allows you to focus your research on a project that is manageable. Beginning work on your literature review can help narrow your topic.

What kind of literature review is appropriate for my research question?

Depending on your area of research, the type of literature review you do for your thesis will vary. Consult with your advisor about the requirements for your discipline. You can view theses and dissertations from your field in the library's Digital Repository can give you ideas about how your literature review should be structured.

What kind of literature should I use?

The kind of literature you use for your thesis will depend on your discipline. The Library has developed a list of Guides by Subject with discipline-specific resources. For a given subject area, look for the guide titles "[Discipline] Research Guide." You may also consult our liaison librarians for information about the literature available your research area.

How will I make sure that I find all the appropriate information that informs my research?

Consulting multiple sources of information is the best way to insure that you have done a comprehensive search of the literature in your area. The What Literature to Search tab has information about the types of resources you may need to search. You may also consult our liaison librarians for assistance with identifying resources..

How will I evaluate the literature to include trustworthy information and eliminate unnecessary or untrustworthy information?

While you are searching for relevant information about your topic you will need to think about the accuracy of the information, whether the information is from a reputable source, whether it is objective and current. Our guides about Evaluating Scholarly Books and Articles and Evaluating Websites will give you criteria to use when evaluating resources.

How should I organize my literature? What citation management program is best for me?

Citation management software can help you organize your references in folders and/or with tags. You can also annotate and highlight the PDFs within the software and usually the notes are searchable. To choose a good citation management software, you need to consider which one can be streamlined with your literature search and writing process. Here is a guide page comparing EndNote, Mendeley & Zotero. The Library also has guides for three of the major citation management tools:

- EndNote & EndNote Web Guide

- Mendeley Guide

- Getting Started with Zotero

What steps should I take to ensure academic integrity?

The best way to ensure academic integrity is to familiarize yourself with different types of intentional and unintentional plagiarism and learn about the University's standards for academic integrity. Start with this guide . The Library also has a guide about your rights and responsibilities regarding copyrighted images and figures that you include in your thesis.

Where can I find writing and editing help?

Writing and editing help is available at the Graduate College's Center for Communication Excellence . The CCE offers individual consultations, peer writing groups, workshops and seminars to help you improve your writing.

Where can I find I find formatting standards? Technical support?

The Graduate College has a Dissertation/ Thesis website with extensive examples and videos about formatting theses and dissertations. The site also has templates and formatting instructions for Word and LaTex .

What citation style should I use?

The Graduate College thesis guidelines require that you "use a consistent, current academic style for your discipline." The Library has a Citation Style Guides resource you can use for guidance on specific citation styles. If you are not sure, please consult your advisor or liaison librarians for help.

Adapted from The Literature Review: For Dissertations, by the University of Michigan Library. Available: https://guides.lib.umich.edu/dissertationlitreview

Center for Communication Excellence/ Library Workshop Slides

Slides from the CCE/ Library Workshop "A Citation Here...A Citation There...Pretty Soon You'll Have a Lit Review" held on February 21, 2024 are below:

- CCE Workshop February 21, 2024

- Next: Types of Literature Reviews >>

The library's collections and services are available to all ISU students, faculty, and staff and Parks Library is open to the public .

- Last Updated: Aug 12, 2024 4:07 PM

- URL: https://instr.iastate.libguides.com/gradlitrev

The Literature Review: A Guide for Postgraduate Students

This guide provides postgraduate students with an overview of the literature review required for most research degrees. It will advise you on the common types of literature reviews across disciplines and will outline how the purpose and structure of each may differ slightly. Various approaches to effective content organisation and writing style are offered, along with some common strategies for effective writing and avoiding some common mistakes. This guide focuses mainly on the required elements of a standalone literature review, but the suggestions and advice apply to literature reviews incorporated into other chapters.

Please see the companion article ‘ The Literature Review: A Guide for Undergraduate Students ’ for an introduction to the basic elements of a literature review. This article focuses on aspects that are particular to postgraduate literature reviews, containing detailed advice and effective strategies for writing a successful literature review. It will address the following topics:

- The purpose of a literature review

- The structure of your literature review

- Strategies for writing an effective literature review

- Mistakes to avoid

The Purpose of a Literature Review

After developing your research proposal and writing a research statement, your literature review is one of the most important early tasks you will undertake for your postgraduate research degree. Many faculties and departments require postgraduate research students to write an initial literature review as part of their research proposal, which forms part of the candidature confirmation process that occurs six months into the research degree for full-time students (12 months for part-time students).

For example, a postgraduate student in history would normally write a 10,000-word research proposal—including a literature review—in the first six months of their PhD. This would be assessed in order to confirm the ongoing candidature of the student.

The literature review is your opportunity you show your supervisor (and ultimately, your examiners) that you understand the most important debates in your field, can identify the texts and authors most relevant to your particular topic, and can examine and evaluate these debates and texts both critically and in depth. You will be expected to provide a comprehensive, detailed and relevant range of scholarly works in your literature review.

In general, a literature review has a specific and directed purpose: to focus the reader’s attention on the significance and necessity of your research. By identifying a ‘gap’ in the current scholarship, you convince your readers that your own research is vital.

As the author, you will achieve these objectives by displaying your in-depth knowledge and understanding of the relevant scholarship in your field, situating your own research within this wider body of work , while critically analysing the scholarship and highlighting your own arguments in relation to that scholarship.

A well-focused, well-developed and well-researched literature review operates as a linchpin for your thesis, provides the background to your research and demonstrates your proficiency in some requisite academic skills.

The Structure of Your Literature Review

Postgraduate degrees can be made up of a long thesis (Master’s and PhD by research) or a shorter thesis and coursework (Master’s by coursework; although some Australian universities now require PhD students to undertake coursework in the first year of their degree). Some disciplines involve creative work (such as a novel or artwork) and an exegesis (such as a creative writing research or fine arts degree). Others can comprise a series of published works in the form of a ‘thesis by publication’ (most common in the science and medical fields).

The structure of a literature review will thus vary according to the discipline and the type of thesis. Some of the most common discipline-based variations are outlined in the following paragraphs.

Humanities and Social Science Degrees

Many humanities and social science theses will include a standalone literature review chapter after the introduction and before any methodology (or theoretical approaches) chapters. In these theses, the literature review might make up around 15 to 30 per cent of the total thesis length, reflecting its purpose as a supporting chapter.

Here, the literature review chapter will have an introduction, an appropriate number of discussion paragraphs and a conclusion. As with a research essay, the introduction operates as a ‘road map’ to the chapter. The introduction should outline and clarify the argument you are making in your thesis (Australian National University 2017), as readers will then have a context for the discussion and critical analysis paragraphs that follow.

The main discussion section can be divided further with subheadings, and the material organised in several possible ways: chronologically, thematically or from the better- to the lesser-known issues and arguments. The conclusion should provide a summary of the chapter overall, and should re-state your thesis statement, linking this to the gap you have identified in the literature that confirms the necessity of your research.

For some humanities’ disciplines, such as literature or history (Premaratne 2013, 236–54), where primary sources are central, the literature review may be conducted chapter-by-chapter, with each chapter focusing on one theme and set of scholarly secondary sources relevant to the primary source material.

Science and Mathematics Degrees

For some science or mathematics research degrees, the literature review may be part of the introduction. The relevant literature here may be limited in number and scope, and if the research project is experiment-based, rather than theoretically based, a lengthy critical analysis of past research may be unnecessary (beyond establishing its weaknesses or failings and thus the necessity for the current research). The literature review section will normally appear after the paragraphs that outline the study’s research question, main findings and theoretical framework. Other science-based degrees may follow the standalone literature review chapter more common in the social sciences.

Strategies for Writing an Effective Literature Review

A research thesis—whether for a Master’s degree or Doctor of Philosophy—is a long project, and the literature review, usually written early on, will most likely be reviewed and refined over the life of the thesis. This section will detail some useful strategies to ensure you write a successful literature review that meets the expectations of your supervisor and examiners.

Using a Mind Map

Before planning or writing, it can be beneficial to undertake a brainstorm exercise to initiate ideas, especially in relation to the organisation of your literature review. A mind map is a very effective technique that can get your ideas flowing prior to a more formal planning process.

A mind map is best created in landscape orientation. Begin by writing a very brief version of your research topic in the middle of the page and then expanding this with themes and sub-themes, identified by keywords or phrases and linked by associations or oppositions. The University of Adelaide provides an excellent introduction to mind mapping.

Planning is as essential at the chapter level as it is for your thesis overall. If you have begun work on your literature review with a mind map or similar process, you can use the themes or organisational categories that emerged to begin organising your content. Plan your literature review as if it were a research essay with an introduction, main body and conclusion.

Create a detailed outline for each main paragraph or section and list the works you will discuss and analyse, along with keywords to identify important themes, arguments and relevant data. By creating a ‘planning document’ in this way, you can keep track of your ideas and refine the plan as you go.

Maintaining a Current Reference List or Annotated Bibliography

It is vital that you maintain detailed and up-to-date records of all scholarly works that you read in relation to your thesis. You will need to ensure that you remain aware of current and developing research, theoretical debates and data as your degree progresses; and review and update the literature review as you work through your own research and writing.

To do this most effectively and efficiently, you will need to record precisely the bibliographic details of each source you use. Decide on the referencing style you will be using at an early stage (this is often dictated by your department or discipline, or suggested by your supervisor). If you begin to construct your reference list as you write your thesis, ensure that you follow any formatting and stylistic requirements for your chosen referencing style from the start (nothing is more onerous than undertaking this task as you are finishing your research degree).

Insert references (also known as ‘citations’) into the text or footnote section as you write your literature review, and be aware of all instances where you need to use a reference . The literature review chapter or section may appear to be overwhelmed with references, but this is just a reflection of the source-based content and purpose.

The Drawbacks of Referencing Software

We don’t recommend the use of referencing software to help you with your references because using this software almost always leads to errors and inconsistencies. They simply can’t be trusted to produce references that will be complete and accurate, properly following your particular referencing style to the letter.

Further, relying on software to create your references for you usually means that you won’t learn how to reference correctly yourself, which is an absolutely vital skill, especially if you are hoping to continue in academia.

Writing Style

Similar to structural matters, your writing style will depend to some extent on your discipline and the expectations and advice of your supervisors. Humanities- and creative arts–based disciplines may be more open to a wider variety of authorial voices. Even if this is so, it remains preferable to establish an academic voice that is credible, engaging and clear.

Simple stylistic strategies such as using the active—instead of the passive—voice, providing variety in sentence structure and length and preferring (where appropriate) simple language over convoluted or overly obscure words can help to ensure your academic writing is both formal and highly readable.

Reviewing, Rewriting and Editing

Although an initial draft is essential (and in some departments it is a formal requirement) to establish the ground for your own research and its place within the wider body of scholarship, the literature review will evolve, develop and be modified as you continue to research, write, review and rewrite your thesis. It is likely that your literature review will not be completed until you have almost finished the thesis itself, and a final assessment and edit of this section is essential to ensure you have included the most important scholarship that is relevant and necessary to your research.

It has happened to many students that a crucial piece of literature is published just as they are about to finalise their thesis, and they must revise their literature review in light of it. Unfortunately, this cannot be avoided, lest your examiners think that you are not aware of this key piece of scholarship. You need to ensure your final literature review reflects how your research now fits into the new landscape in your field after any recent developments.

Mistakes to Avoid

Some common mistakes can result in an ineffective literature review that could then flow on to the rest of your thesis. These mistakes include:

- Trying to read and include everything you find on your topic. The literature review should be selective as well as comprehensive, examining only those sources relevant to your research topic.

- Listing the scholarship as if you are writing an annotated bibliography or a series of summaries. Your discussion of the literature should be synthesised and holistic, and should have a logical progression that is appropriate to the organisation of your content.

- Failing to integrate your examination of the literature with your own thesis topic. You need to develop your discussion of each piece of scholarship in relation to other pieces of research, contextualising your analyses and conclusions in relation to your thesis statement or research topic and focusing on how your own research relates to, complements and extends the existing scholarship.

Writing the literature review is often the first task of your research degree. It is a focused reading and research activity that situates your own research in the wider scholarship, establishing yourself as an active member of the academic community through dialogue and debate. By reading, analysing and synthesising the existing scholarship on your topic, you gain a comprehensive and in-depth understanding, ensuring a solid basis for your own arguments and contributions. If you need advice on referencing , academic writing , time management or other aspects of your degree, you may find Capstone Editing’s other resources and blog articles useful.

Australian National University. 2017. ‘Literature Reviews’. Last accessed 28 March. http://www.anu.edu.au/students/learning-development/research-writing/literature-reviews.

Premaratne, Dhilara Darshana. 2013. ‘Discipline Based Variations in the Literature Review in the PhD Thesis: A Perspective from the Discipline of History’. Education and Research Perspectives 40: 236–54.

Other guides you may be interested in

Essay writing: everything you need to know and nothing you don’t—part 1: how to begin.

This guide will explain everything you need to know about how to organise, research and write an argumentative essay.

Essay Writing Part 2: How to Organise Your Research

Organising your research effectively is a crucial and often overlooked step to successful essay writing.

Located in northeastern New South Wales 200 kilometres south of Brisbane, Lismore offers students a good study–play balance, in a gorgeous sub-tropical climate.

Rockhampton

The administrative hub for Central Queensland, Rockhampton is a popular tourist attraction due to its many national parks and proximity to Great Keppel Island.

Press ESC to close

A roadmap for writing a literature review in a master’s thesis: Examples and guidelines

- backlinkworks

- Writing Articles & Reviews

- December 27, 2023

writing a literature review is an essential part of any master’s thesis. IT involves critically evaluating and synthesizing existing research to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-written literature review demonstrates your understanding of the scholarly conversation surrounding your research topic and helps to contextualize your own work within the broader academic landscape.

1. Understand the purpose of a literature review

Before you begin writing your literature review, IT ‘s important to understand its purpose. A literature review serves several key functions, including:

- Providing a comprehensive overview of existing research in your field.

- Critically evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of previous studies.

- Identifying gaps in the literature and highlighting areas for future research.

- Contextualizing your own research within the broader academic discourse.

By clearly understanding the purpose of your literature review, you can ensure that your writing is focused and relevant to your thesis.

2. Conduct a comprehensive literature search

Once you have a clear understanding of the purpose of your literature review, the next step is to conduct a comprehensive search for relevant academic sources. This involves searching for peer-reviewed journal articles, books, conference proceedings, and other scholarly publications related to your research topic.

IT ‘s important to use a variety of search strategies, including keyword searches, citation tracking, and database searches, to ensure that you are capturing all relevant literature. Additionally, consider using citation management software to organize and manage your references.

For example, if your master’s thesis is about the impact of social media on mental health, you would want to search for literature that examines the relationship between social media use and psychological well-being. This might include studies on social media usage patterns, the prevalence of mental health issues among social media users, and the potential benefits and drawbacks of social media use.

3. Analyze and synthesize the literature

Once you have gathered a comprehensive collection of literature related to your research topic, the next step is to analyze and synthesize the information. This involves critically evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of each study, identifying key themes and patterns across the literature, and synthesizing the findings into a coherent narrative.

When analyzing and synthesizing the literature, consider the following questions:

- What are the main findings and arguments of each source?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of each study?

- What key themes and patterns emerge across the literature?

Using the example of the impact of social media on mental health, you might identify several key themes that emerge across the literature, such as the relationship between social media use and depression, the role of cyberbullying in affecting mental well-being, and the potential benefits of online peer support networks.

4. Write the literature review

With a clear understanding of the purpose of your literature review, a comprehensive collection of relevant literature, and a synthesized analysis of the existing research, you are now ready to write your literature review. When writing your literature review, consider the following guidelines:

- Provide a clear and comprehensive overview of the existing literature in your field.

- Critically evaluate and synthesize the key findings and arguments of each source.

- Organize the literature thematically or chronologically to highlight key patterns and developments in the research.

- Keep the focus on how each source relates to your research topic and thesis.

Continuing with the example of the impact of social media on mental health, your literature review might be organized into sections that correspond to the key themes you identified during your analysis. Each section could summarize and evaluate the existing literature on a specific aspect of the relationship between social media use and mental well-being, providing a clear overview of the current state of knowledge in the field.

5. Conclusion

Overall, writing a literature review for your master’s thesis involves understanding the purpose of the literature review, conducting a comprehensive literature search, analyzing and synthesizing the literature, and writing a well-organized and critical review of the existing research. By following these guidelines and examples, you can ensure that your literature review effectively contextualizes your own research within the broader academic discourse.

Q: How long should a literature review be?

A: The length of a literature review can vary depending on the requirements of your master’s thesis and the depth and breadth of the existing literature. In general, a literature review for a master’s thesis is typically around 3000-5000 words, but this can vary based on the specific expectations of your program or advisor.

Q: How many sources should I include in my literature review?

A: The number of sources you include in your literature review will depend on the scope of your research topic and the expectations of your program or advisor. In general, a literature review for a master’s thesis should include a comprehensive collection of relevant sources, typically ranging from 20-50 academic articles, books, and other scholarly publications.

Top 10 Recording Software for Professional Sound Engineering

Designing a professional website with a web hosting wordpress theme.

Recent Posts

- Driving Organic Growth: How a Digital SEO Agency Can Drive Traffic to Your Website

- Mastering Local SEO for Web Agencies: Reaching Your Target Market

- The Ultimate Guide to Unlocking Powerful Backlinks for Your Website

- SEO vs. Paid Advertising: Finding the Right Balance for Your Web Marketing Strategy

- Discover the Secret Weapon for Local SEO Success: Local Link Building Services

Popular Posts

Unlocking the Secrets to Boosting Your Alexa Rank, Google Pagerank, and Domain Age – See How You Can Dominate the Web!

Shocking Secret Revealed: How Article PHP ID Can Transform Your Website!

Uncovering the Top Secret Tricks for Mastering SPIP PHP – You Won’t Believe What You’re Missing Out On!

The Ultimate Collection of Free Themes for Google Sites

10 Tips for Creating a Stunning WordPress Theme

Explore topics.

- Backlinks (2,425)

- Blog (2,744)

- Computers (5,318)

- Digital Marketing (7,741)

- Internet (6,340)

- Website (4,705)

- Wordpress (4,705)

- Writing Articles & Reviews (4,208)

How to write a literature review introduction (+ examples)

The introduction to a literature review serves as your reader’s guide through your academic work and thought process. Explore the significance of literature review introductions in review papers, academic papers, essays, theses, and dissertations. We delve into the purpose and necessity of these introductions, explore the essential components of literature review introductions, and provide step-by-step guidance on how to craft your own, along with examples.

Why you need an introduction for a literature review

In academic writing , the introduction for a literature review is an indispensable component. Effective academic writing requires proper paragraph structuring to guide your reader through your argumentation. This includes providing an introduction to your literature review.

It is imperative to remember that you should never start sharing your findings abruptly. Even if there isn’t a dedicated introduction section .

When you need an introduction for a literature review

There are three main scenarios in which you need an introduction for a literature review:

What to include in a literature review introduction

It is crucial to customize the content and depth of your literature review introduction according to the specific format of your academic work.

Academic literature review paper

The introduction of an academic literature review paper, which does not rely on empirical data, often necessitates a more extensive introduction than the brief literature review introductions typically found in empirical papers. It should encompass:

Regular literature review section in an academic article or essay

In a standard 8000-word journal article, the literature review section typically spans between 750 and 1250 words. The first few sentences or the first paragraph within this section often serve as an introduction. It should encompass:

Introduction to a literature review chapter in thesis or dissertation

Some students choose to incorporate a brief introductory section at the beginning of each chapter, including the literature review chapter. Alternatively, others opt to seamlessly integrate the introduction into the initial sentences of the literature review itself. Both approaches are acceptable, provided that you incorporate the following elements:

Examples of literature review introductions

Example 1: an effective introduction for an academic literature review paper.

To begin, let’s delve into the introduction of an academic literature review paper. We will examine the paper “How does culture influence innovation? A systematic literature review”, which was published in 2018 in the journal Management Decision.

Example 2: An effective introduction to a literature review section in an academic paper

The second example represents a typical academic paper, encompassing not only a literature review section but also empirical data, a case study, and other elements. We will closely examine the introduction to the literature review section in the paper “The environmentalism of the subalterns: a case study of environmental activism in Eastern Kurdistan/Rojhelat”, which was published in 2021 in the journal Local Environment.

Thus, the author successfully introduces the literature review, from which point onward it dives into the main concept (‘subalternity’) of the research, and reviews the literature on socio-economic justice and environmental degradation.