- How to write a research paper

Last updated

11 January 2024

Reviewed by

With proper planning, knowledge, and framework, completing a research paper can be a fulfilling and exciting experience.

Though it might initially sound slightly intimidating, this guide will help you embrace the challenge.

By documenting your findings, you can inspire others and make a difference in your field. Here's how you can make your research paper unique and comprehensive.

- What is a research paper?

Research papers allow you to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of a particular topic. These papers are usually lengthier and more detailed than typical essays, requiring deeper insight into the chosen topic.

To write a research paper, you must first choose a topic that interests you and is relevant to the field of study. Once you’ve selected your topic, gathering as many relevant resources as possible, including books, scholarly articles, credible websites, and other academic materials, is essential. You must then read and analyze these sources, summarizing their key points and identifying gaps in the current research.

You can formulate your ideas and opinions once you thoroughly understand the existing research. To get there might involve conducting original research, gathering data, or analyzing existing data sets. It could also involve presenting an original argument or interpretation of the existing research.

Writing a successful research paper involves presenting your findings clearly and engagingly, which might involve using charts, graphs, or other visual aids to present your data and using concise language to explain your findings. You must also ensure your paper adheres to relevant academic formatting guidelines, including proper citations and references.

Overall, writing a research paper requires a significant amount of time, effort, and attention to detail. However, it is also an enriching experience that allows you to delve deeply into a subject that interests you and contribute to the existing body of knowledge in your chosen field.

- How long should a research paper be?

Research papers are deep dives into a topic. Therefore, they tend to be longer pieces of work than essays or opinion pieces.

However, a suitable length depends on the complexity of the topic and your level of expertise. For instance, are you a first-year college student or an experienced professional?

Also, remember that the best research papers provide valuable information for the benefit of others. Therefore, the quality of information matters most, not necessarily the length. Being concise is valuable.

Following these best practice steps will help keep your process simple and productive:

1. Gaining a deep understanding of any expectations

Before diving into your intended topic or beginning the research phase, take some time to orient yourself. Suppose there’s a specific topic assigned to you. In that case, it’s essential to deeply understand the question and organize your planning and approach in response. Pay attention to the key requirements and ensure you align your writing accordingly.

This preparation step entails

Deeply understanding the task or assignment

Being clear about the expected format and length

Familiarizing yourself with the citation and referencing requirements

Understanding any defined limits for your research contribution

Where applicable, speaking to your professor or research supervisor for further clarification

2. Choose your research topic

Select a research topic that aligns with both your interests and available resources. Ideally, focus on a field where you possess significant experience and analytical skills. In crafting your research paper, it's crucial to go beyond summarizing existing data and contribute fresh insights to the chosen area.

Consider narrowing your focus to a specific aspect of the topic. For example, if exploring the link between technology and mental health, delve into how social media use during the pandemic impacts the well-being of college students. Conducting interviews and surveys with students could provide firsthand data and unique perspectives, adding substantial value to the existing knowledge.

When finalizing your topic, adhere to legal and ethical norms in the relevant area (this ensures the integrity of your research, protects participants' rights, upholds intellectual property standards, and ensures transparency and accountability). Following these principles not only maintains the credibility of your work but also builds trust within your academic or professional community.

For instance, in writing about medical research, consider legal and ethical norms , including patient confidentiality laws and informed consent requirements. Similarly, if analyzing user data on social media platforms, be mindful of data privacy regulations, ensuring compliance with laws governing personal information collection and use. Aligning with legal and ethical standards not only avoids potential issues but also underscores the responsible conduct of your research.

3. Gather preliminary research

Once you’ve landed on your topic, it’s time to explore it further. You’ll want to discover more about available resources and existing research relevant to your assignment at this stage.

This exploratory phase is vital as you may discover issues with your original idea or realize you have insufficient resources to explore the topic effectively. This key bit of groundwork allows you to redirect your research topic in a different, more feasible, or more relevant direction if necessary.

Spending ample time at this stage ensures you gather everything you need, learn as much as you can about the topic, and discover gaps where the topic has yet to be sufficiently covered, offering an opportunity to research it further.

4. Define your research question

To produce a well-structured and focused paper, it is imperative to formulate a clear and precise research question that will guide your work. Your research question must be informed by the existing literature and tailored to the scope and objectives of your project. By refining your focus, you can produce a thoughtful and engaging paper that effectively communicates your ideas to your readers.

5. Write a thesis statement

A thesis statement is a one-to-two-sentence summary of your research paper's main argument or direction. It serves as an overall guide to summarize the overall intent of the research paper for you and anyone wanting to know more about the research.

A strong thesis statement is:

Concise and clear: Explain your case in simple sentences (avoid covering multiple ideas). It might help to think of this section as an elevator pitch.

Specific: Ensure that there is no ambiguity in your statement and that your summary covers the points argued in the paper.

Debatable: A thesis statement puts forward a specific argument––it is not merely a statement but a debatable point that can be analyzed and discussed.

Here are three thesis statement examples from different disciplines:

Psychology thesis example: "We're studying adults aged 25-40 to see if taking short breaks for mindfulness can help with stress. Our goal is to find practical ways to manage anxiety better."

Environmental science thesis example: "This research paper looks into how having more city parks might make the air cleaner and keep people healthier. I want to find out if more green spaces means breathing fewer carcinogens in big cities."

UX research thesis example: "This study focuses on improving mobile banking for older adults using ethnographic research, eye-tracking analysis, and interactive prototyping. We investigate the usefulness of eye-tracking analysis with older individuals, aiming to spark debate and offer fresh perspectives on UX design and digital inclusivity for the aging population."

6. Conduct in-depth research

A research paper doesn’t just include research that you’ve uncovered from other papers and studies but your fresh insights, too. You will seek to become an expert on your topic––understanding the nuances in the current leading theories. You will analyze existing research and add your thinking and discoveries. It's crucial to conduct well-designed research that is rigorous, robust, and based on reliable sources. Suppose a research paper lacks evidence or is biased. In that case, it won't benefit the academic community or the general public. Therefore, examining the topic thoroughly and furthering its understanding through high-quality research is essential. That usually means conducting new research. Depending on the area under investigation, you may conduct surveys, interviews, diary studies , or observational research to uncover new insights or bolster current claims.

7. Determine supporting evidence

Not every piece of research you’ve discovered will be relevant to your research paper. It’s important to categorize the most meaningful evidence to include alongside your discoveries. It's important to include evidence that doesn't support your claims to avoid exclusion bias and ensure a fair research paper.

8. Write a research paper outline

Before diving in and writing the whole paper, start with an outline. It will help you to see if more research is needed, and it will provide a framework by which to write a more compelling paper. Your supervisor may even request an outline to approve before beginning to write the first draft of the full paper. An outline will include your topic, thesis statement, key headings, short summaries of the research, and your arguments.

9. Write your first draft

Once you feel confident about your outline and sources, it’s time to write your first draft. While penning a long piece of content can be intimidating, if you’ve laid the groundwork, you will have a structure to help you move steadily through each section. To keep up motivation and inspiration, it’s often best to keep the pace quick. Stopping for long periods can interrupt your flow and make jumping back in harder than writing when things are fresh in your mind.

10. Cite your sources correctly

It's always a good practice to give credit where it's due, and the same goes for citing any works that have influenced your paper. Building your arguments on credible references adds value and authenticity to your research. In the formatting guidelines section, you’ll find an overview of different citation styles (MLA, CMOS, or APA), which will help you meet any publishing or academic requirements and strengthen your paper's credibility. It is essential to follow the guidelines provided by your school or the publication you are submitting to ensure the accuracy and relevance of your citations.

11. Ensure your work is original

It is crucial to ensure the originality of your paper, as plagiarism can lead to serious consequences. To avoid plagiarism, you should use proper paraphrasing and quoting techniques. Paraphrasing is rewriting a text in your own words while maintaining the original meaning. Quoting involves directly citing the source. Giving credit to the original author or source is essential whenever you borrow their ideas or words. You can also use plagiarism detection tools such as Scribbr or Grammarly to check the originality of your paper. These tools compare your draft writing to a vast database of online sources. If you find any accidental plagiarism, you should correct it immediately by rephrasing or citing the source.

12. Revise, edit, and proofread

One of the essential qualities of excellent writers is their ability to understand the importance of editing and proofreading. Even though it's tempting to call it a day once you've finished your writing, editing your work can significantly improve its quality. It's natural to overlook the weaker areas when you've just finished writing a paper. Therefore, it's best to take a break of a day or two, or even up to a week, to refresh your mind. This way, you can return to your work with a new perspective. After some breathing room, you can spot any inconsistencies, spelling and grammar errors, typos, or missing citations and correct them.

- The best research paper format

The format of your research paper should align with the requirements set forth by your college, school, or target publication.

There is no one “best” format, per se. Depending on the stated requirements, you may need to include the following elements:

Title page: The title page of a research paper typically includes the title, author's name, and institutional affiliation and may include additional information such as a course name or instructor's name.

Table of contents: Include a table of contents to make it easy for readers to find specific sections of your paper.

Abstract: The abstract is a summary of the purpose of the paper.

Methods : In this section, describe the research methods used. This may include collecting data , conducting interviews, or doing field research .

Results: Summarize the conclusions you drew from your research in this section.

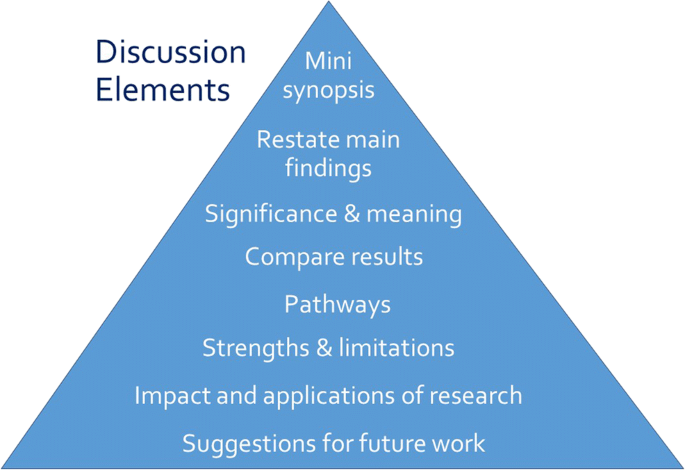

Discussion: In this section, discuss the implications of your research . Be sure to mention any significant limitations to your approach and suggest areas for further research.

Tables, charts, and illustrations: Use tables, charts, and illustrations to help convey your research findings and make them easier to understand.

Works cited or reference page: Include a works cited or reference page to give credit to the sources that you used to conduct your research.

Bibliography: Provide a list of all the sources you consulted while conducting your research.

Dedication and acknowledgments : Optionally, you may include a dedication and acknowledgments section to thank individuals who helped you with your research.

- General style and formatting guidelines

Formatting your research paper means you can submit it to your college, journal, or other publications in compliance with their criteria.

Research papers tend to follow the American Psychological Association (APA), Modern Language Association (MLA), or Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS) guidelines.

Here’s how each style guide is typically used:

Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS):

CMOS is a versatile style guide used for various types of writing. It's known for its flexibility and use in the humanities. CMOS provides guidelines for citations, formatting, and overall writing style. It allows for both footnotes and in-text citations, giving writers options based on their preferences or publication requirements.

American Psychological Association (APA):

APA is common in the social sciences. It’s hailed for its clarity and emphasis on precision. It has specific rules for citing sources, creating references, and formatting papers. APA style uses in-text citations with an accompanying reference list. It's designed to convey information efficiently and is widely used in academic and scientific writing.

Modern Language Association (MLA):

MLA is widely used in the humanities, especially literature and language studies. It emphasizes the author-page format for in-text citations and provides guidelines for creating a "Works Cited" page. MLA is known for its focus on the author's name and the literary works cited. It’s frequently used in disciplines that prioritize literary analysis and critical thinking.

To confirm you're using the latest style guide, check the official website or publisher's site for updates, consult academic resources, and verify the guide's publication date. Online platforms and educational resources may also provide summaries and alerts about any revisions or additions to the style guide.

Citing sources

When working on your research paper, it's important to cite the sources you used properly. Your citation style will guide you through this process. Generally, there are three parts to citing sources in your research paper:

First, provide a brief citation in the body of your essay. This is also known as a parenthetical or in-text citation.

Second, include a full citation in the Reference list at the end of your paper. Different types of citations include in-text citations, footnotes, and reference lists.

In-text citations include the author's surname and the date of the citation.

Footnotes appear at the bottom of each page of your research paper. They may also be summarized within a reference list at the end of the paper.

A reference list includes all of the research used within the paper at the end of the document. It should include the author, date, paper title, and publisher listed in the order that aligns with your citation style.

10 research paper writing tips:

Following some best practices is essential to writing a research paper that contributes to your field of study and creates a positive impact.

These tactics will help you structure your argument effectively and ensure your work benefits others:

Clear and precise language: Ensure your language is unambiguous. Use academic language appropriately, but keep it simple. Also, provide clear takeaways for your audience.

Effective idea separation: Organize the vast amount of information and sources in your paper with paragraphs and titles. Create easily digestible sections for your readers to navigate through.

Compelling intro: Craft an engaging introduction that captures your reader's interest. Hook your audience and motivate them to continue reading.

Thorough revision and editing: Take the time to review and edit your paper comprehensively. Use tools like Grammarly to detect and correct small, overlooked errors.

Thesis precision: Develop a clear and concise thesis statement that guides your paper. Ensure that your thesis aligns with your research's overall purpose and contribution.

Logical flow of ideas: Maintain a logical progression throughout the paper. Use transitions effectively to connect different sections and maintain coherence.

Critical evaluation of sources: Evaluate and critically assess the relevance and reliability of your sources. Ensure that your research is based on credible and up-to-date information.

Thematic consistency: Maintain a consistent theme throughout the paper. Ensure that all sections contribute cohesively to the overall argument.

Relevant supporting evidence: Provide concise and relevant evidence to support your arguments. Avoid unnecessary details that may distract from the main points.

Embrace counterarguments: Acknowledge and address opposing views to strengthen your position. Show that you have considered alternative arguments in your field.

7 research tips

If you want your paper to not only be well-written but also contribute to the progress of human knowledge, consider these tips to take your paper to the next level:

Selecting the appropriate topic: The topic you select should align with your area of expertise, comply with the requirements of your project, and have sufficient resources for a comprehensive investigation.

Use academic databases: Academic databases such as PubMed, Google Scholar, and JSTOR offer a wealth of research papers that can help you discover everything you need to know about your chosen topic.

Critically evaluate sources: It is important not to accept research findings at face value. Instead, it is crucial to critically analyze the information to avoid jumping to conclusions or overlooking important details. A well-written research paper requires a critical analysis with thorough reasoning to support claims.

Diversify your sources: Expand your research horizons by exploring a variety of sources beyond the standard databases. Utilize books, conference proceedings, and interviews to gather diverse perspectives and enrich your understanding of the topic.

Take detailed notes: Detailed note-taking is crucial during research and can help you form the outline and body of your paper.

Stay up on trends: Keep abreast of the latest developments in your field by regularly checking for recent publications. Subscribe to newsletters, follow relevant journals, and attend conferences to stay informed about emerging trends and advancements.

Engage in peer review: Seek feedback from peers or mentors to ensure the rigor and validity of your research . Peer review helps identify potential weaknesses in your methodology and strengthens the overall credibility of your findings.

- The real-world impact of research papers

Writing a research paper is more than an academic or business exercise. The experience provides an opportunity to explore a subject in-depth, broaden one's understanding, and arrive at meaningful conclusions. With careful planning, dedication, and hard work, writing a research paper can be a fulfilling and enriching experience contributing to advancing knowledge.

How do I publish my research paper?

Many academics wish to publish their research papers. While challenging, your paper might get traction if it covers new and well-written information. To publish your research paper, find a target publication, thoroughly read their guidelines, format your paper accordingly, and send it to them per their instructions. You may need to include a cover letter, too. After submission, your paper may be peer-reviewed by experts to assess its legitimacy, quality, originality, and methodology. Following review, you will be informed by the publication whether they have accepted or rejected your paper.

What is a good opening sentence for a research paper?

Beginning your research paper with a compelling introduction can ensure readers are interested in going further. A relevant quote, a compelling statistic, or a bold argument can start the paper and hook your reader. Remember, though, that the most important aspect of a research paper is the quality of the information––not necessarily your ability to storytell, so ensure anything you write aligns with your goals.

Research paper vs. a research proposal—what’s the difference?

While some may confuse research papers and proposals, they are different documents.

A research proposal comes before a research paper. It is a detailed document that outlines an intended area of exploration. It includes the research topic, methodology, timeline, sources, and potential conclusions. Research proposals are often required when seeking approval to conduct research.

A research paper is a summary of research findings. A research paper follows a structured format to present those findings and construct an argument or conclusion.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

- 10 research paper

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research paper

How to Write a Research Paper | A Beginner's Guide

A research paper is a piece of academic writing that provides analysis, interpretation, and argument based on in-depth independent research.

Research papers are similar to academic essays , but they are usually longer and more detailed assignments, designed to assess not only your writing skills but also your skills in scholarly research. Writing a research paper requires you to demonstrate a strong knowledge of your topic, engage with a variety of sources, and make an original contribution to the debate.

This step-by-step guide takes you through the entire writing process, from understanding your assignment to proofreading your final draft.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Understand the assignment, choose a research paper topic, conduct preliminary research, develop a thesis statement, create a research paper outline, write a first draft of the research paper, write the introduction, write a compelling body of text, write the conclusion, the second draft, the revision process, research paper checklist, free lecture slides.

Completing a research paper successfully means accomplishing the specific tasks set out for you. Before you start, make sure you thoroughly understanding the assignment task sheet:

- Read it carefully, looking for anything confusing you might need to clarify with your professor.

- Identify the assignment goal, deadline, length specifications, formatting, and submission method.

- Make a bulleted list of the key points, then go back and cross completed items off as you’re writing.

Carefully consider your timeframe and word limit: be realistic, and plan enough time to research, write, and edit.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

There are many ways to generate an idea for a research paper, from brainstorming with pen and paper to talking it through with a fellow student or professor.

You can try free writing, which involves taking a broad topic and writing continuously for two or three minutes to identify absolutely anything relevant that could be interesting.

You can also gain inspiration from other research. The discussion or recommendations sections of research papers often include ideas for other specific topics that require further examination.

Once you have a broad subject area, narrow it down to choose a topic that interests you, m eets the criteria of your assignment, and i s possible to research. Aim for ideas that are both original and specific:

- A paper following the chronology of World War II would not be original or specific enough.

- A paper on the experience of Danish citizens living close to the German border during World War II would be specific and could be original enough.

Note any discussions that seem important to the topic, and try to find an issue that you can focus your paper around. Use a variety of sources , including journals, books, and reliable websites, to ensure you do not miss anything glaring.

Do not only verify the ideas you have in mind, but look for sources that contradict your point of view.

- Is there anything people seem to overlook in the sources you research?

- Are there any heated debates you can address?

- Do you have a unique take on your topic?

- Have there been some recent developments that build on the extant research?

In this stage, you might find it helpful to formulate some research questions to help guide you. To write research questions, try to finish the following sentence: “I want to know how/what/why…”

A thesis statement is a statement of your central argument — it establishes the purpose and position of your paper. If you started with a research question, the thesis statement should answer it. It should also show what evidence and reasoning you’ll use to support that answer.

The thesis statement should be concise, contentious, and coherent. That means it should briefly summarize your argument in a sentence or two, make a claim that requires further evidence or analysis, and make a coherent point that relates to every part of the paper.

You will probably revise and refine the thesis statement as you do more research, but it can serve as a guide throughout the writing process. Every paragraph should aim to support and develop this central claim.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

A research paper outline is essentially a list of the key topics, arguments, and evidence you want to include, divided into sections with headings so that you know roughly what the paper will look like before you start writing.

A structure outline can help make the writing process much more efficient, so it’s worth dedicating some time to create one.

Your first draft won’t be perfect — you can polish later on. Your priorities at this stage are as follows:

- Maintaining forward momentum — write now, perfect later.

- Paying attention to clear organization and logical ordering of paragraphs and sentences, which will help when you come to the second draft.

- Expressing your ideas as clearly as possible, so you know what you were trying to say when you come back to the text.

You do not need to start by writing the introduction. Begin where it feels most natural for you — some prefer to finish the most difficult sections first, while others choose to start with the easiest part. If you created an outline, use it as a map while you work.

Do not delete large sections of text. If you begin to dislike something you have written or find it doesn’t quite fit, move it to a different document, but don’t lose it completely — you never know if it might come in useful later.

Paragraph structure

Paragraphs are the basic building blocks of research papers. Each one should focus on a single claim or idea that helps to establish the overall argument or purpose of the paper.

Example paragraph

George Orwell’s 1946 essay “Politics and the English Language” has had an enduring impact on thought about the relationship between politics and language. This impact is particularly obvious in light of the various critical review articles that have recently referenced the essay. For example, consider Mark Falcoff’s 2009 article in The National Review Online, “The Perversion of Language; or, Orwell Revisited,” in which he analyzes several common words (“activist,” “civil-rights leader,” “diversity,” and more). Falcoff’s close analysis of the ambiguity built into political language intentionally mirrors Orwell’s own point-by-point analysis of the political language of his day. Even 63 years after its publication, Orwell’s essay is emulated by contemporary thinkers.

Citing sources

It’s also important to keep track of citations at this stage to avoid accidental plagiarism . Each time you use a source, make sure to take note of where the information came from.

You can use our free citation generators to automatically create citations and save your reference list as you go.

APA Citation Generator MLA Citation Generator

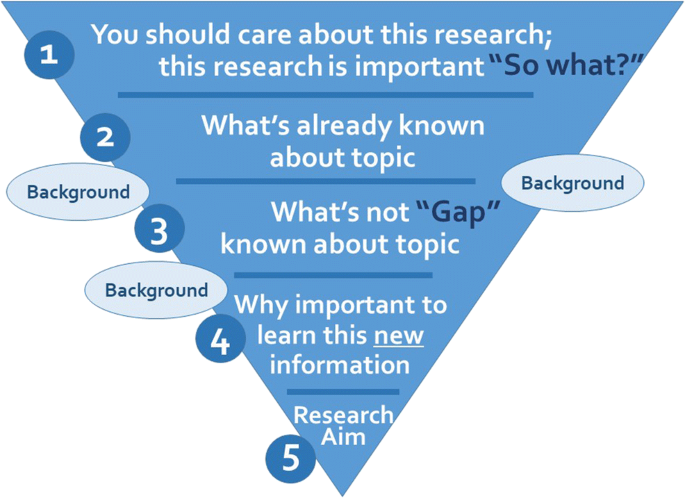

The research paper introduction should address three questions: What, why, and how? After finishing the introduction, the reader should know what the paper is about, why it is worth reading, and how you’ll build your arguments.

What? Be specific about the topic of the paper, introduce the background, and define key terms or concepts.

Why? This is the most important, but also the most difficult, part of the introduction. Try to provide brief answers to the following questions: What new material or insight are you offering? What important issues does your essay help define or answer?

How? To let the reader know what to expect from the rest of the paper, the introduction should include a “map” of what will be discussed, briefly presenting the key elements of the paper in chronological order.

The major struggle faced by most writers is how to organize the information presented in the paper, which is one reason an outline is so useful. However, remember that the outline is only a guide and, when writing, you can be flexible with the order in which the information and arguments are presented.

One way to stay on track is to use your thesis statement and topic sentences . Check:

- topic sentences against the thesis statement;

- topic sentences against each other, for similarities and logical ordering;

- and each sentence against the topic sentence of that paragraph.

Be aware of paragraphs that seem to cover the same things. If two paragraphs discuss something similar, they must approach that topic in different ways. Aim to create smooth transitions between sentences, paragraphs, and sections.

The research paper conclusion is designed to help your reader out of the paper’s argument, giving them a sense of finality.

Trace the course of the paper, emphasizing how it all comes together to prove your thesis statement. Give the paper a sense of finality by making sure the reader understands how you’ve settled the issues raised in the introduction.

You might also discuss the more general consequences of the argument, outline what the paper offers to future students of the topic, and suggest any questions the paper’s argument raises but cannot or does not try to answer.

You should not :

- Offer new arguments or essential information

- Take up any more space than necessary

- Begin with stock phrases that signal you are ending the paper (e.g. “In conclusion”)

There are four main considerations when it comes to the second draft.

- Check how your vision of the paper lines up with the first draft and, more importantly, that your paper still answers the assignment.

- Identify any assumptions that might require (more substantial) justification, keeping your reader’s perspective foremost in mind. Remove these points if you cannot substantiate them further.

- Be open to rearranging your ideas. Check whether any sections feel out of place and whether your ideas could be better organized.

- If you find that old ideas do not fit as well as you anticipated, you should cut them out or condense them. You might also find that new and well-suited ideas occurred to you during the writing of the first draft — now is the time to make them part of the paper.

The goal during the revision and proofreading process is to ensure you have completed all the necessary tasks and that the paper is as well-articulated as possible. You can speed up the proofreading process by using the AI proofreader .

Global concerns

- Confirm that your paper completes every task specified in your assignment sheet.

- Check for logical organization and flow of paragraphs.

- Check paragraphs against the introduction and thesis statement.

Fine-grained details

Check the content of each paragraph, making sure that:

- each sentence helps support the topic sentence.

- no unnecessary or irrelevant information is present.

- all technical terms your audience might not know are identified.

Next, think about sentence structure , grammatical errors, and formatting . Check that you have correctly used transition words and phrases to show the connections between your ideas. Look for typos, cut unnecessary words, and check for consistency in aspects such as heading formatting and spellings .

Finally, you need to make sure your paper is correctly formatted according to the rules of the citation style you are using. For example, you might need to include an MLA heading or create an APA title page .

Scribbr’s professional editors can help with the revision process with our award-winning proofreading services.

Discover our paper editing service

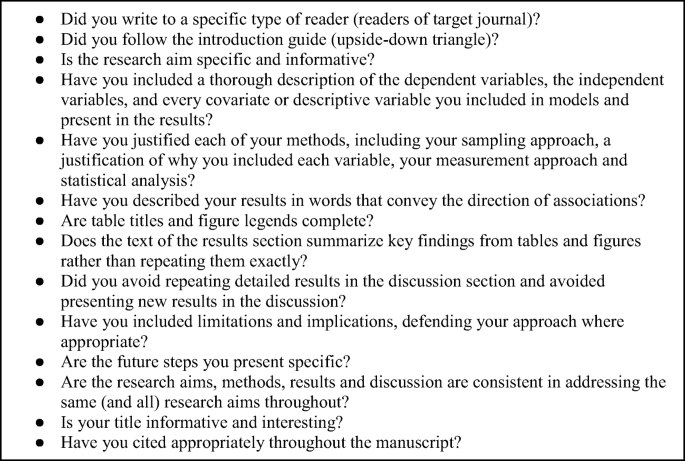

Checklist: Research paper

I have followed all instructions in the assignment sheet.

My introduction presents my topic in an engaging way and provides necessary background information.

My introduction presents a clear, focused research problem and/or thesis statement .

My paper is logically organized using paragraphs and (if relevant) section headings .

Each paragraph is clearly focused on one central idea, expressed in a clear topic sentence .

Each paragraph is relevant to my research problem or thesis statement.

I have used appropriate transitions to clarify the connections between sections, paragraphs, and sentences.

My conclusion provides a concise answer to the research question or emphasizes how the thesis has been supported.

My conclusion shows how my research has contributed to knowledge or understanding of my topic.

My conclusion does not present any new points or information essential to my argument.

I have provided an in-text citation every time I refer to ideas or information from a source.

I have included a reference list at the end of my paper, consistently formatted according to a specific citation style .

I have thoroughly revised my paper and addressed any feedback from my professor or supervisor.

I have followed all formatting guidelines (page numbers, headers, spacing, etc.).

You've written a great paper. Make sure it's perfect with the help of a Scribbr editor!

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- Writing a Research Paper Introduction | Step-by-Step Guide

- Writing a Research Paper Conclusion | Step-by-Step Guide

- Research Paper Format | APA, MLA, & Chicago Templates

More interesting articles

- Academic Paragraph Structure | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- Checklist: Writing a Great Research Paper

- How to Create a Structured Research Paper Outline | Example

- How to Write a Discussion Section | Tips & Examples

- How to Write Recommendations in Research | Examples & Tips

- How to Write Topic Sentences | 4 Steps, Examples & Purpose

- Research Paper Appendix | Example & Templates

- Research Paper Damage Control | Managing a Broken Argument

- What Is a Theoretical Framework? | Guide to Organizing

Get unlimited documents corrected

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications . If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

Can you help me with a full paper template for this Abstract:

Background: Energy and sports drinks have gained popularity among diverse demographic groups, including adolescents, athletes, workers, and college students. While often used interchangeably, these beverages serve distinct purposes, with energy drinks aiming to boost energy and cognitive performance, and sports drinks designed to prevent dehydration and replenish electrolytes and carbohydrates lost during physical exertion.

Objective: To assess the nutritional quality of energy and sports drinks in Egypt.

Material and Methods: A cross-sectional study assessed the nutrient contents, including energy, sugar, electrolytes, vitamins, and caffeine, of sports and energy drinks available in major supermarkets in Cairo, Alexandria, and Giza, Egypt. Data collection involved photographing all relevant product labels and recording nutritional information. Descriptive statistics and appropriate statistical tests were employed to analyze and compare the nutritional values of energy and sports drinks.

Results: The study analyzed 38 sports drinks and 42 energy drinks. Sports drinks were significantly more expensive than energy drinks, with higher net content and elevated magnesium, potassium, and vitamin C. Energy drinks contained higher concentrations of caffeine, sugars, and vitamins B2, B3, and B6.

Conclusion: Significant nutritional differences exist between sports and energy drinks, reflecting their intended uses. However, these beverages’ high sugar content and calorie loads raise health concerns. Proper labeling, public awareness, and responsible marketing are essential to guide safe consumption practices in Egypt.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

How to Write a Research Paper

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Research Paper Fundamentals

How to choose a topic or question, how to create a working hypothesis or thesis, common research paper methodologies, how to gather and organize evidence , how to write an outline for your research paper, how to write a rough draft, how to revise your draft, how to produce a final draft, resources for teachers .

It is not fair to say that no one writes anymore. Just about everyone writes text messages, brief emails, or social media posts every single day. Yet, most people don't have a lot of practice with the formal, organized writing required for a good academic research paper. This guide contains links to a variety of resources that can help demystify the process. Some of these resources are intended for teachers; they contain exercises, activities, and teaching strategies. Other resources are intended for direct use by students who are struggling to write papers, or are looking for tips to make the process go more smoothly.

The resources in this section are designed to help students understand the different types of research papers, the general research process, and how to manage their time. Below, you'll find links from university writing centers, the trusted Purdue Online Writing Lab, and more.

What is an Academic Research Paper?

"Genre and the Research Paper" (Purdue OWL)

There are different types of research papers. Different types of scholarly questions will lend themselves to one format or another. This is a brief introduction to the two main genres of research paper: analytic and argumentative.

"7 Most Popular Types of Research Papers" (Personal-writer.com)

This resource discusses formats that high school students commonly encounter, such as the compare and contrast essay and the definitional essay. Please note that the inclusion of this link is not an endorsement of this company's paid service.

How to Prepare and Plan Out Writing a Research Paper

Teachers can give their students a step-by-step guide like these to help them understand the different steps of the research paper process. These guides can be combined with the time management tools in the next subsection to help students come up with customized calendars for completing their papers.

"Ten Steps for Writing Research Papers" (American University)

This resource from American University is a comprehensive guide to the research paper writing process, and includes examples of proper research questions and thesis topics.

"Steps in Writing a Research Paper" (SUNY Empire State College)

This guide breaks the research paper process into 11 steps. Each "step" links to a separate page, which describes the work entailed in completing it.

How to Manage Time Effectively

The links below will help students determine how much time is necessary to complete a paper. If your sources are not available online or at your local library, you'll need to leave extra time for the Interlibrary Loan process. Remember that, even if you do not need to consult secondary sources, you'll still need to leave yourself ample time to organize your thoughts.

"Research Paper Planner: Timeline" (Baylor University)

This interactive resource from Baylor University creates a suggested writing schedule based on how much time a student has to work on the assignment.

"Research Paper Planner" (UCLA)

UCLA's library offers this step-by-step guide to the research paper writing process, which also includes a suggested planning calendar.

There's a reason teachers spend a long time talking about choosing a good topic. Without a good topic and a well-formulated research question, it is almost impossible to write a clear and organized paper. The resources below will help you generate ideas and formulate precise questions.

"How to Select a Research Topic" (Univ. of Michigan-Flint)

This resource is designed for college students who are struggling to come up with an appropriate topic. A student who uses this resource and still feels unsure about his or her topic should consult the course instructor for further personalized assistance.

"25 Interesting Research Paper Topics to Get You Started" (Kibin)

This resource, which is probably most appropriate for high school students, provides a list of specific topics to help get students started. It is broken into subsections, such as "paper topics on local issues."

"Writing a Good Research Question" (Grand Canyon University)

This introduction to research questions includes some embedded videos, as well as links to scholarly articles on research questions. This resource would be most appropriate for teachers who are planning lessons on research paper fundamentals.

"How to Write a Research Question the Right Way" (Kibin)

This student-focused resource provides more detail on writing research questions. The language is accessible, and there are embedded videos and examples of good and bad questions.

It is important to have a rough hypothesis or thesis in mind at the beginning of the research process. People who have a sense of what they want to say will have an easier time sorting through scholarly sources and other information. The key, of course, is not to become too wedded to the draft hypothesis or thesis. Just about every working thesis gets changed during the research process.

CrashCourse Video: "Sociology Research Methods" (YouTube)

Although this video is tailored to sociology students, it is applicable to students in a variety of social science disciplines. This video does a good job demonstrating the connection between the brainstorming that goes into selecting a research question and the formulation of a working hypothesis.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement for an Analytical Essay" (YouTube)

Students writing analytical essays will not develop the same type of working hypothesis as students who are writing research papers in other disciplines. For these students, developing the working thesis may happen as a part of the rough draft (see the relevant section below).

"Research Hypothesis" (Oakland Univ.)

This resource provides some examples of hypotheses in social science disciplines like Political Science and Criminal Justice. These sample hypotheses may also be useful for students in other soft social sciences and humanities disciplines like History.

When grading a research paper, instructors look for a consistent methodology. This section will help you understand different methodological approaches used in research papers. Students will get the most out of these resources if they use them to help prepare for conversations with teachers or discussions in class.

"Types of Research Designs" (USC)

A "research design," used for complex papers, is related to the paper's method. This resource contains introductions to a variety of popular research designs in the social sciences. Although it is not the most intuitive site to read, the information here is very valuable.

"Major Research Methods" (YouTube)

Although this video is a bit on the dry side, it provides a comprehensive overview of the major research methodologies in a format that might be more accessible to students who have struggled with textbooks or other written resources.

"Humanities Research Strategies" (USC)

This is a portal where students can learn about four methodological approaches for humanities papers: Historical Methodologies, Textual Criticism, Conceptual Analysis, and the Synoptic method.

"Selected Major Social Science Research Methods: Overview" (National Academies Press)

This appendix from the book Using Science as Evidence in Public Policy , printed by National Academies Press, introduces some methods used in social science papers.

"Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: 6. The Methodology" (USC)

This resource from the University of Southern California's library contains tips for writing a methodology section in a research paper.

How to Determine the Best Methodology for You

Anyone who is new to writing research papers should be sure to select a method in consultation with their instructor. These resources can be used to help prepare for that discussion. They may also be used on their own by more advanced students.

"Choosing Appropriate Research Methodologies" (Palgrave Study Skills)

This friendly and approachable resource from Palgrave Macmillan can be used by students who are just starting to think about appropriate methodologies.

"How to Choose Your Research Methods" (NFER (UK))

This is another approachable resource students can use to help narrow down the most appropriate methods for their research projects.

The resources in this section introduce the process of gathering scholarly sources and collecting evidence. You'll find a range of material here, from introductory guides to advanced explications best suited to college students. Please consult the LitCharts How to Do Academic Research guide for a more comprehensive list of resources devoted to finding scholarly literature.

Google Scholar

Students who have access to library websites with detailed research guides should start there, but people who do not have access to those resources can begin their search for secondary literature here.

"Gathering Appropriate Information" (Texas Gateway)

This resource from the Texas Gateway for online resources introduces students to the research process, and contains interactive exercises. The level of complexity is suitable for middle school, high school, and introductory college classrooms.

"An Overview of Quantitative and Qualitative Data Collection Methods" (NSF)

This PDF from the National Science Foundation goes into detail about best practices and pitfalls in data collection across multiple types of methodologies.

"Social Science Methods for Data Collection and Analysis" (Swiss FIT)

This resource is appropriate for advanced undergraduates or teachers looking to create lessons on research design and data collection. It covers techniques for gathering data via interviews, observations, and other methods.

"Collecting Data by In-depth Interviewing" (Leeds Univ.)

This resource contains enough information about conducting interviews to make it useful for teachers who want to create a lesson plan, but is also accessible enough for college juniors or seniors to make use of it on their own.

There is no "one size fits all" outlining technique. Some students might devote all their energy and attention to the outline in order to avoid the paper. Other students may benefit from being made to sit down and organize their thoughts into a lengthy sentence outline. The resources in this section include strategies and templates for multiple types of outlines.

"Topic vs. Sentence Outlines" (UC Berkeley)

This resource introduces two basic approaches to outlining: the shorter topic-based approach, and the longer, more detailed sentence-based approach. This resource also contains videos on how to develop paper paragraphs from the sentence-based outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL)

The Purdue Online Writing Lab's guide is a slightly less detailed discussion of different types of outlines. It contains several sample outlines.

"Writing An Outline" (Austin C.C.)

This resource from a community college contains sample outlines from an American history class that students can use as models.

"How to Structure an Outline for a College Paper" (YouTube)

This brief (sub-2 minute) video from the ExpertVillage YouTube channel provides a model of outline writing for students who are struggling with the idea.

"Outlining" (Harvard)

This is a good resource to consult after completing a draft outline. It offers suggestions for making sure your outline avoids things like unnecessary repetition.

As with outlines, rough drafts can take on many different forms. These resources introduce teachers and students to the various approaches to writing a rough draft. This section also includes resources that will help you cite your sources appropriately according to the MLA, Chicago, and APA style manuals.

"Creating a Rough Draft for a Research Paper" (Univ. of Minnesota)

This resource is useful for teachers in particular, as it provides some suggested exercises to help students with writing a basic rough draft.

Rough Draft Assignment (Duke of Definition)

This sample assignment, with a brief list of tips, was developed by a high school teacher who runs a very successful and well-reviewed page of educational resources.

"Creating the First Draft of Your Research Paper" (Concordia Univ.)

This resource will be helpful for perfectionists or procrastinators, as it opens by discussing the problem of avoiding writing. It also provides a short list of suggestions meant to get students writing.

Using Proper Citations

There is no such thing as a rough draft of a scholarly citation. These links to the three major citation guides will ensure that your citations follow the correct format. Please consult the LitCharts How to Cite Your Sources guide for more resources.

Chicago Manual of Style Citation Guide

Some call The Chicago Manual of Style , which was first published in 1906, "the editors' Bible." The manual is now in its 17th edition, and is popular in the social sciences, historical journals, and some other fields in the humanities.

APA Citation Guide

According to the American Psychological Association, this guide was developed to aid reading comprehension, clarity of communication, and to reduce bias in language in the social and behavioral sciences. Its first full edition was published in 1952, and it is now in its sixth edition.

MLA Citation Guide

The Modern Language Association style is used most commonly within the liberal arts and humanities. The MLA Style Manual and Guide to Scholarly Publishing was first published in 1985 and (as of 2008) is in its third edition.

Any professional scholar will tell you that the best research papers are made in the revision stage. No matter how strong your research question or working thesis, it is not possible to write a truly outstanding paper without devoting energy to revision. These resources provide examples of revision exercises for the classroom, as well as tips for students working independently.

"The Art of Revision" (Univ. of Arizona)

This resource provides a wealth of information and suggestions for both students and teachers. There is a list of suggested exercises that teachers might use in class, along with a revision checklist that is useful for teachers and students alike.

"Script for Workshop on Revision" (Vanderbilt University)

Vanderbilt's guide for leading a 50-minute revision workshop can serve as a model for teachers who wish to guide students through the revision process during classtime.

"Revising Your Paper" (Univ. of Washington)

This detailed handout was designed for students who are beginning the revision process. It discusses different approaches and methods for revision, and also includes a detailed list of things students should look for while they revise.

"Revising Drafts" (UNC Writing Center)

This resource is designed for students and suggests things to look for during the revision process. It provides steps for the process and has a FAQ for students who have questions about why it is important to revise.

Conferencing with Writing Tutors and Instructors

No writer is so good that he or she can't benefit from meeting with instructors or peer tutors. These resources from university writing, learning, and communication centers provide suggestions for how to get the most out of these one-on-one meetings.

"Getting Feedback" (UNC Writing Center)

This very helpful resource talks about how to ask for feedback during the entire writing process. It contains possible questions that students might ask when developing an outline, during the revision process, and after the final draft has been graded.

"Prepare for Your Tutoring Session" (Otis College of Art and Design)

This guide from a university's student learning center contains a lot of helpful tips for getting the most out of working with a writing tutor.

"The Importance of Asking Your Professor" (Univ. of Waterloo)

This article from the university's Writing and Communication Centre's blog contains some suggestions for how and when to get help from professors and Teaching Assistants.

Once you've revised your first draft, you're well on your way to handing in a polished paper. These resources—each of them produced by writing professionals at colleges and universities—outline the steps required in order to produce a final draft. You'll find proofreading tips and checklists in text and video form.

"Developing a Final Draft of a Research Paper" (Univ. of Minnesota)

While this resource contains suggestions for revision, it also features a couple of helpful checklists for the last stages of completing a final draft.

Basic Final Draft Tips and Checklist (Univ. of Maryland-University College)

This short and accessible resource, part of UMUC's very thorough online guide to writing and research, contains a very basic checklist for students who are getting ready to turn in their final drafts.

Final Draft Checklist (Everett C.C.)

This is another accessible final draft checklist, appropriate for both high school and college students. It suggests reading your essay aloud at least once.

"How to Proofread Your Final Draft" (YouTube)

This video (approximately 5 minutes), produced by Eastern Washington University, gives students tips on proofreading final drafts.

"Proofreading Tips" (Georgia Southern-Armstrong)

This guide will help students learn how to spot common errors in their papers. It suggests focusing on content and editing for grammar and mechanics.

This final set of resources is intended specifically for high school and college instructors. It provides links to unit plans and classroom exercises that can help improve students' research and writing skills. You'll find resources that give an overview of the process, along with activities that focus on how to begin and how to carry out research.

"Research Paper Complete Resources Pack" (Teachers Pay Teachers)

This packet of assignments, rubrics, and other resources is designed for high school students. The resources in this packet are aligned to Common Core standards.

"Research Paper—Complete Unit" (Teachers Pay Teachers)

This packet of assignments, notes, PowerPoints, and other resources has a 4/4 rating with over 700 ratings. It is designed for high school teachers, but might also be useful to college instructors who work with freshmen.

"Teaching Students to Write Good Papers" (Yale)

This resource from Yale's Center for Teaching and Learning is designed for college instructors, and it includes links to appropriate activities and exercises.

"Research Paper Writing: An Overview" (CUNY Brooklyn)

CUNY Brooklyn offers this complete lesson plan for introducing students to research papers. It includes an accompanying set of PowerPoint slides.

"Lesson Plan: How to Begin Writing a Research Paper" (San Jose State Univ.)

This lesson plan is designed for students in the health sciences, so teachers will have to modify it for their own needs. It includes a breakdown of the brainstorming, topic selection, and research question process.

"Quantitative Techniques for Social Science Research" (Univ. of Pittsburgh)

This is a set of PowerPoint slides that can be used to introduce students to a variety of quantitative methods used in the social sciences.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1978 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 41,744 quotes across 1978 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Writing your research paper

How to start your research paper [step-by-step guide]

All research papers have pretty much the same structure. If you can write one type of research paper, you can write another. Learn the steps to start and complete your research paper in our guide.

How to write a problem statement

What is a problem statement and how do you write one? This guide answers all your questions and includes an example of a problem statement.

How to write a research paper outline

Structuring the outline of your research paper early on is important. Read on to learn how to structure a research paper outline and to see examples, including an outline template.

How to write a research proposal

What is a research proposal and what should you use it for? This step-by-step guide teaches you how to structure and write a research proposal.

How to write an abstract

Not sure how to write an abstract for your paper? Clear your doubts with this guide, follow our tips, and start writing your abstract!

What are the different types of research papers?

Learn all you need to know about research papers, what differentiates a research paper from a thesis, and what types of research papers there are.

What is a research paper?

Are you confused about what a research paper actually is and what differentiates it from a thesis? Clarify it once and for all with our guide.

What is an appendix in a paper

Not sure what an appendix in a paper is? This guides defines what an appendix is and how to format one.

What is the abstract of a paper?

Not sure what the abstract of a paper is? Learn the definition of an abstract and how to format one in this guide with resources.

ENGL 101: Academic Writing: How to write a research paper

- Research Tools

- How to evaluate resources

- How to write a research paper

- Occupational Resources

How to write a research paer

Understand the topic, what is the instructor asking for, who is the intended audience, choosing a topic.

- General Research

Books on the subject

Journal articles, other sources, write the paper.

You've just been assigned by your instructor to write a paper on a topic. Relax, this isn't going to be as bad as it seems. You just need to get started. Here are some suggestions to make the process as painless as possible. Remember, if you have any questions ASK .

Is the assignment a formal research paper where you have to do research and cite other sources of information, or is the assignment asking you for your reaction to a particular topic where all you will need to do is collect your thoughts and organize them coherently. If you do need to research your topic, make sure you know what style manual your instructor prefers (MLA, APA, Chicago, etc).

Make sure you keep track of any restrictions that your instructor places on you. If your instructor wants a 4 page paper, they won't be happy with a 2 page paper, or a 10 page paper. Keep in mind that the instructor knows roughly how long it should take to cover the topic. If your paper is too short, you probably aren't looking at enough materials. If you paper is too long, you need to narrow your topic. Also, many times the instructor may restrict you to certain types of resources (books written after 1946, scholarly journals, no web sites). You don't want to automatically lessen your grade by not following the rules. Remember the key rule, if you have any questions ask your instructor!

You will also need to know which audience that you are writing for. Are you writing to an audience that knows nothing about your topic? If so you will need to write in such a way that you paper makes sense, and can be understood by these people. If your paper is geared to peers who have a similar background of information you won't need to include that type of information. If your paper is for experts in the field, you won't need to include background information.

If you're lucky, you were given a narrow topic by your instructor. You may not be interested in your topic, but you can be reasonably sure that the topic isn't too broad. Most of you aren't going to be that lucky. Your instructor gave you a broad topic, or no topic at all and you are going to have to choose the specific topic for your paper.