Cultivating empathy

Psychologists’ research offers insight into why it’s so important to practice the “right” kind of empathy, and how to grow these skills

Vol. 52 No. 8 Print version: page 44

- Personality

In a society marked by increasing division, we could all be a bit more kind, cooperative, and tolerant toward others. Beneficial as those traits are, psychological research suggests empathy may be the umbrella trait required to develop all these virtues. As empathy researcher and Stanford University psychologist Jamil Zaki, PhD, describes it, empathy is the “psychological ‘superglue’ that connects people and undergirds co-operation and kindness” ( The Economist , June 7, 2019). And even if empathy doesn’t come naturally, research suggests people can cultivate it—and hopefully improve society as a result.

“In general, empathy is a powerful predictor of things we consider to be positive behaviors that benefit society, individuals, and relationships,” said Karina Schumann , PhD, a professor of social psychology at the University of Pittsburgh. “Scholars have shown across domains that empathy motivates many types of prosocial behaviors, such as forgiveness, volunteering, and helping, and that it’s negatively associated with things like aggression and bullying.”

For example, research by C. Daniel Batson , PhD, a professor emeritus of social psychology at the University of Kansas, suggests empathy can motivate people to help someone else in need ( Altruism in Humans , Oxford University Press, 2011), and a 2019 study suggests empathy levels predict charitable donation behavior (Smith, K. E., et al., The Journal of Positive Psychology , Vol. 15, No. 6, 2020).

Ann Rumble , PhD, a psychology lecturer at Northern Arizona University, found empathy can override noncooperation, causing people to be more generous and forgiving and less retaliative ( European Journal of Social Psychology , Vol. 40, No. 5, 2010). “Empathic people ask themselves, ‘Maybe I need to find out more before I jump to a harsh judgment,’” she said.

Empathy can also promote better relationships with strangers. For example, Batson’s past research highlights that empathy can help people adopt more positive attitudes and helping behavior toward stigmatized groups, particularly disabled and homeless individuals and those with AIDS ( Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , Vol. 72, No. 1, 1997).

Empathy may also be a crucial ingredient in mitigating bias and systemic racism. Jason Okonofua , PhD, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, has found that teachers are more likely to employ severe discipline with Black students—and that they’re more likely to label Black students as “troublemakers” ( Psychological Science , Vol. 26, No. 5, 2015).

These labels, Okonofua said, can shape how teachers interpret behavior, forging a path toward students’ school failure and incarceration. When Okonofua and his colleagues created an intervention to help teachers build positive relationships with students and value their perspectives, their increased empathy reduced punitive discipline ( PNAS , Vol. 113, No. 19, 2016).

Similarly, Okonofua and colleagues found empathy from parole officers can prevent adults on probation from reoffending ( PNAS , Vol. 118, No. 14, 2021).

In spite of its potential benefits, empathy itself isn’t an automatic path toward social good. To develop empathy that actually helps people requires strategy. “If you’re trying to develop empathy in yourself or in others, you have to make sure you’re developing the right kind,” said Sara Konrath , PhD, an associate professor of social psychology at Indiana University who studies empathy and altruism.

The right kind of empathy

Empathy is often crucial for psychologists working with patients in practice, especially when patients are seeking validation of their feelings. However, empathy can be a draining skill if not practiced correctly. Overidentifying with someone else’s emotions can be stressful, leading to a cardiovascular stress response similar to what you’d experience in the same painful or threatening situation, said Michael J. Poulin , PhD, an associate professor of psychology at the University at Buffalo who studies how people respond to others’ adversity.

Outside of clinical practice, some scholars argue empathy is unhelpful and even damaging. For example, Paul Bloom, PhD , a professor of psychology at Yale University, argues that because empathy directs helping behavior toward specific individuals—most often, those in one’s own group—it may prevent more beneficial help to others ( Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion , Ecco , 2016).

In some cases, empathy may also promote antagonism and aggression (Buffone, A. E. K., & Poulin, M. J., Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , Vol. 40, No. 11, 2014). For example, Daryl Cameron , PhD, an associate professor of psychology and senior research associate in the Rock Ethics Institute and director of the Empathy and Moral Psychology Lab at Penn State University, has found that apparent biases in empathy like parochialism and the numbness to mass suffering may sometimes be due to motivated choices. He also notes that empathy can still have risks in some cases. “There are times when what looks like empathy promotes favoritism at the expense of the outgroup,” said Cameron.

Many of these negative outcomes are associated with a type of empathy called self-oriented perspective taking—imagining yourself in someone else’s shoes. “How you take the perspective can make a difference,” said John Dovidio , PhD, the Carl I. Hovland Professor Emeritus of Psychology and a professor emeritus in the Institute for Social and Policy Studies and of Epidemiology at Yale University. “When you ask me to imagine myself in another person’s position,” Dovidio said, “I may experience a lot of personal distress, which can interfere with prosocial behaviors.” Taking on that emotional burden, Schumann added, could also increase your own risk for distressing emotions, such as anxiety.

According to Konrath, the form of empathy shown most beneficial for both the giver and the receiver is an other-oriented response. “It’s a cognitive style of perspective taking where someone imagines another person’s perspective, reads their emotions, and can understand them in general,” she said.

Other-oriented perspective taking may result in empathic concern, also known as compassion, which could be seen as an emotional response to a cognitive process. It’s that emotion that may trigger helping behavior. “If I simply understand you’re in trouble, I may not act, but emotion energizes me,” said Dovidio.

While many practitioners may find empathy to come naturally, psychologists’ research can help clinicians guide patients toward other-oriented empathy and can also help practitioners struggling with compassion fatigue to re-up their empathy. According to Poulin, people are more likely to opt out of empathy if it feels cognitively or emotionally taxing, which could impact psychologists’ ability to effectively support their patients.

To avoid compassion fatigue with patients—and maintain the empathy required for helping them—Poulin said it’s important to reflect on the patient’s feeling or experience without necessarily trying to feel it yourself. “It’s about putting yourself in the right role,” he said. “Your goal isn’t to be the sufferer, but to be the caregiver.”

Be willing to grow

Cameron’s research found that the cognitive costs of empathy could cause people to avoid it but that it may be possible to increase empathy by teaching people to do it effectively ( Journal of Experimental Psychology: General , Vol. 148, No. 6, 2019).

Further, research by Schumann and Zaki shows that the desire to grow in empathy can be a driver in cultivating it. They found people can extend empathic effort—asking questions and listening longer to responses—in situations where they feel different than someone, primarily if they believe empathy could be developed with effort ( Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , Vol. 107, No. 3, 2014).

Similarly, Erika Weisz , PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in psychology at Harvard University, said that the first step to increasing your empathy is to adopt a growth mindset—to believe you’re capable of growing in empathy.

“People who believe that empathy can grow try harder to empathize when it doesn’t come naturally to them, for instance, by empathizing with people who are unfamiliar to them or different than they are, compared to people who believe empathy is a stable trait,” she said.

For example, Weisz found addressing college students’ empathy mindsets increases the accuracy with which they perceive others’ emotions; it also tracks with the number of friends college freshmen make during their first year on campus ( Emotion , online first publication, 2020).

Expose yourself to differences

To imagine another’s perspective, the more context, the better. Shereen Naser , PhD, a professor of psychology at Cleveland State University, said consuming diverse media—for example, a White person reading books or watching movies with a non-White protagonist—and even directly participating in someone else’s culture can provide a backdrop against which to adopt someone else’s perspective.

When you’re in these situations, be fully present. “Paying attention to other people allows you to be moved by their experiences,” said Sara Hodges , PhD, a professor of psychology at the University of Oregon. “Whether you are actively perspective-taking or not, if you just pay more attention to other people, you’re likely to feel more concerned for them and become more involved in their experiences.”

For example, in a course focused on diversity, Naser encourages her graduate students to visit a community they’ve never spent time in. “One student came back saying they felt like an outsider when they attended a Hindu celebration and that they realized that’s what marginalized people feel like every day,” she said. Along with decreasing your bias, such realizations could also spark a deeper understanding of another’s culture—and why they might think or feel the way they do.

Read fiction

Raymond Mar , PhD, a professor of psychology at York University in Toronto, studies how reading fiction and other kinds of character-driven stories can help people better understand others and the world. “To understand stories, we have to understand characters, their motivations, interactions, reactions, and goals,” he said. “It’s possible that while understanding stories, we can improve our ability to understand real people in the real world at the same time.”

When you engage with a story, you’re also engaging the same cognitive abilities you’d use during social cognition ( Current Directions in Psychological Science , Vol. 27, No. 4, 2018). You can get the same effect with any medium—live theater, a show on Netflix, or a novel—as long as it has core elements of a narrative, story, and characters.

The more one practices empathy (e.g., by relating to fictional characters), the more perspectives one can absorb while not feeling that one’s own is threatened. “The foundation of empathy has to be a willingness to listen to other peoples’ experiences and to believe they’re valid,” Mar said. “You don’t have to deny your own experience to accept someone else’s.”

Harness the power of oxytocin

The social hormone oxytocin also plays a role in facilitating empathy. Bianca Jones Marlin , PhD, a neuroscientist and assistant professor of psychology at Columbia University, found that mice that had given birth are more likely to pick up crying pups than virgin animals and that the oxytocin released during the birth and parenting process actually changes the hearing centers of the brain to motivate prosocial and survival behaviors ( Nature , Vol. 520, No. 7548, 2015).

Oxytocin can also breed helping responses in those who don’t have a blood relationship; when Marlin added oxytocin to virgin mice’s hearing centers, they took care of pups that weren’t theirs. “It’s as if biology has prepared us to take care of those who can’t take care of themselves,” she said. “But that’s just a baseline; it’s up to us as a society to build this in our relationships.”

Through oxytocin-releasing behaviors like eye contact and soft physical touch, Marlin said humans can harness the power of oxytocin to promote empathy and helping behaviors in certain contexts. Oxytocin is also known to mediate ingroup and outgroup feelings.

The key, Marlin said, is for both parties to feel connected and unthreatened. To overcome that hurdle, she suggests a calm but direct approach: Try saying, “I don’t agree with your views, but I want to learn more about what led you to that perspective.”

Identify common ground

Feeling a sense of social connection is an important part of triggering prosocial behaviors. “You perceive the person as a member of your own group, or because the situation is so compelling that your common humanity is aroused,” Dovidio said. “When you experience this empathy, it motivates you to help the other person, even at a personal cost to you.”

One way to boost this motivation is to manipulate who you see as your ingroup. Jay Van Bavel , PhD, an associate professor of psychology and neural science at New York University, found that in the absence of an existing social connection, finding a shared identity can promote empathy ( Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , Vol. 55, 2014). “We find over and over again when people have a common identity, even if it’s created in the moment, they are more motivated to get inside the mind of another person,” Van Bavel said.

For example, Van Bavel has conducted fMRI research that suggests being placed on the same team for a work activity can increase cooperation and trigger positive feelings for individuals once perceived as outgroup, even among different races ( Psychological Science , Vol. 19, No. 11, 2008).

To motivate empathy in your own interactions, find similarities instead of focusing on differences. For instance, maybe you and a neighbor have polar opposite political ideologies, but your kids are the same age and go to the same school. Build on that similarity to create more empathy. “We contain multiple identities, and part of being socially intelligent is finding the identity you share,” Van Bavel said.

Ask questions

Existing research often measures a person’s empathy by accuracy—how well people can label someone’s face as angry, sad, or happy, for example. Alexandra Main , PhD, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of California, Merced, said curiosity and interest can also be an important component of empathy. “Mind reading isn’t always the way empathy works in everyday life. It’s more about actively trying to appreciate someone’s point of view,” she said. If you’re in a situation and struggling with empathy, it’s not necessarily that you don’t care—your difficulty may be because you don’t understand that person’s perspective. Asking questions and engaging in curiosity is one way to change that.

While Main’s research focuses on parent-child relationships, she says the approach also applies to other relationship dynamics; for example, curiosity about why your spouse doesn’t do the dishes might help you understand influencing factors and, as a result, prevent conflict and promote empathy.

Main suggests asking open-ended questions to the person you want to show empathy to, and providing nonverbal cues like nodding when someone’s talking can encourage that person to share more. Certain questions, like ones you should already know the answer to, can have the opposite effect, as can asking personal questions when your social partner doesn’t wish to share.

The important thing is to express interest. “These kinds of behaviors are really facilitative of disclosure and open discussion,” Main said. “And in the long term, expressing interest in another person can facilitate empathy in the relationship” ( Social Development , Vol. 28, No. 3, 2019).

Understand your blocks

Research suggests everyone has empathy blocks, or areas where it is difficult to exhibit empathy. To combat these barriers to prosocial behavior, Schumann suggests noticing your patterns and focusing on areas where you feel it’s hard to connect to people and relate to their experiences.

If you find it hard to be around negative people, for example, confront this difficulty and spend time with them. Try to reflect on a time when you had a negative outlook on something and observe how they relate. And as you listen, don’t interrupt or formulate rebuttals or responses.

“The person will feel so much more validated and heard when they’ve really had an opportunity to voice their opinion, and most of the time people will reciprocate,” Schumann said. “You might still disagree strongly, but you will have a stronger sense of why they have the perspective they do.”

Second-guess yourself

Much of empathy boils down to willingness to learn—and all learning involves questioning your assumptions and automatic reactions in both big-picture issues, such as racism, and everyday interactions. According to Rumble, it’s important to be mindful of “what-ifs” in frustrating situations before jumping to snap judgments. For example, if a patient is continually late to appointments, don’t assume they don’t take therapy seriously––something else, like stress or unreliable transportation, might be getting in the way of their timeliness.

And if you do find yourself making a negative assumption, slow down and admit you could be wrong. “As scientists, we second-guess our assumptions all the time, looking for alternative explanations,” said Hodges. “We need to do that as people, too.”

Further reading

What’s the matter with empathy? Konrath, S. H., Greater Good Magazine , Jan. 24, 2017

Addressing the empathy deficit: Beliefs about the malleability of empathy predict effortful responses when empathy is challenging Schumann, K., et al., Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 2014

It is hard to read minds without words: Cues to use to achieve empathic accuracy Hodges, S. D., & Kezer, M., Journal of Intelligence , 2021

Recommended Reading

Contact apa, you may also like.

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

Daring Leadership Institute: a groundbreaking partnership that amplifies Brené Brown's empirically based, courage-building curriculum with BetterUp’s human transformation platform.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Find your coach

-1.png)

Research, expert insights, and resources to develop courageous leaders within your organization.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

Empathic listening: what it is and how to use it

Jump to section

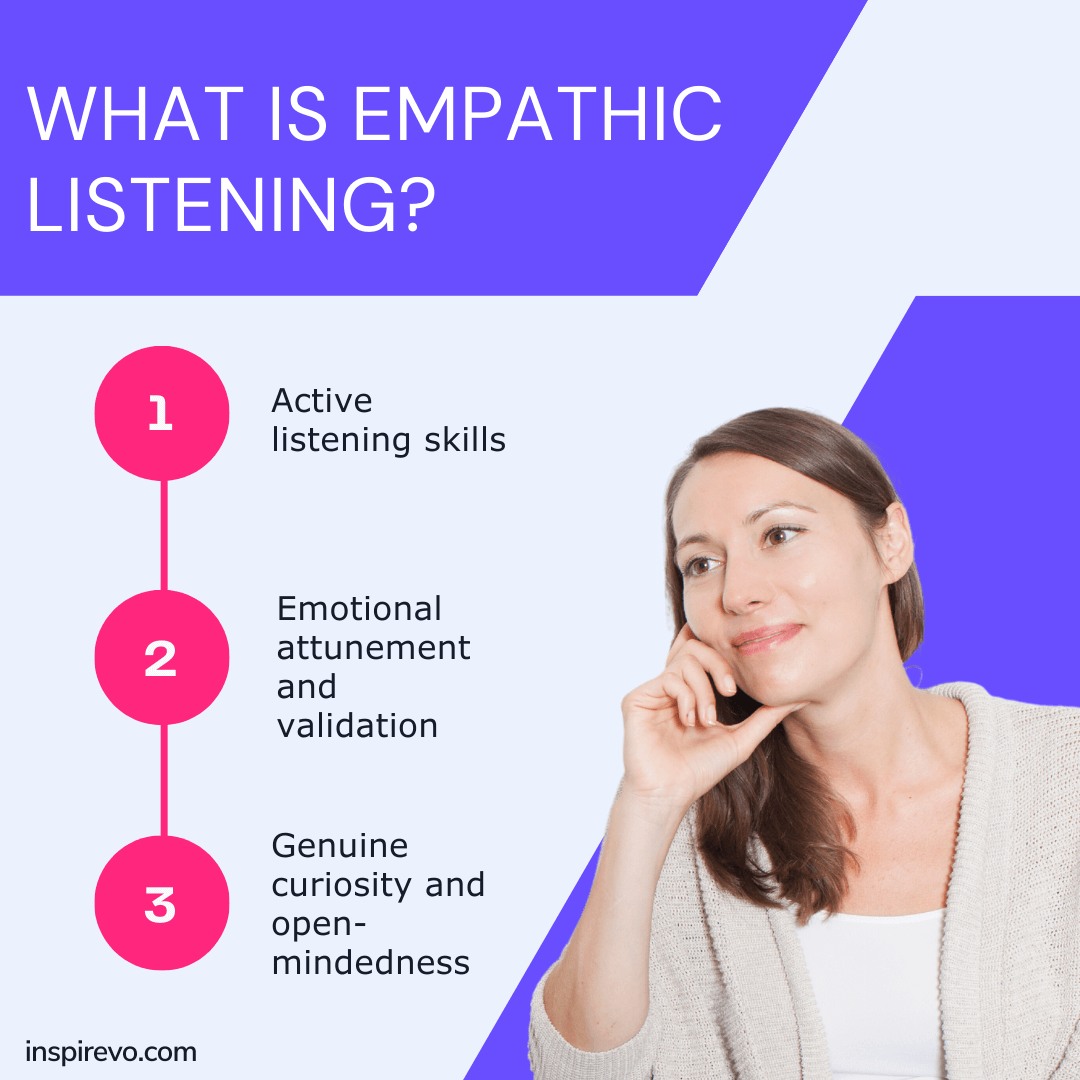

What is empathic listening?

Passive versus empathic listening, why empathic listening matters , 5 essential empathic listening skills, how to become a more empathic listener, use empathic listening to build better relationships.

Everyone wants to feel heard and understood. Because of this, listening is one of the best ways to connect with others and build healthy bonds. Offering someone your full attention and compassion can be life-changing for them and you.

If you want to build listening skills, you may wonder, "What makes a good listener?" Anyone can perk their ears up at a conversation. But deep, connected listening feels and works differently. It's called empathic listening, and it can change your perspective and relationships for the better.

Listening like an empath is a great skill, but what is an empath , exactly? They are people highly attuned to the feelings and emotions of others. You may be an empath by nature, but if not, you can build the skills.

Empathic listening means understanding a speaker’s message through the active process of listening and observation. Empathic listening is more than hearing. The practice lets you focus on the emotion behind the words.

Empathic listening relies on reading body language and understanding types of nonverbal communication . By using it, you consider the other person's perspective by focusing on their experience with intention. In this way, empathic listening requires you to be fully present and engaged.

Naturally, empathetic people are often good listeners and leaders. They connect deeply and often seek out those emotional ties through listening. Anyone can build skills to be more empathic.

You can show empathetic engagement in various ways:

- Making eye contact

- Nodding agreement and understanding

- Showing engagement and interest in your speaker

- Asking questions for clarity and context when appropriate (not interrupting)

Empathic listening fosters a sense of trust and validation, enabling more meaningful relationships and communication. It helps you form a deeper human connection with your conversational partner. By developing the skill of empathic listening, you can see where the other person is coming from and respond with compassion.

There are different types of listening : active and passive. Passive listening, despite its shortcomings, is the default for many.

Passive listening habits tune out the speaker's emotions and intentions. As a result, you might only get a superficial understanding of their message. You hear the words spoken but may not process or engage with the content.

Passive listeners may not make eye contact. They often interrupt or let their minds wander into how they'll respond when it's "their turn."

You can't foster genuine connection or understanding with passive methods. Passive listening can make conversations feel superficial and speakers feel undervalued. In truth, this type of listening is a missed opportunity for deeper connections.

It's often said that listening is a lost art. In reality, listening is a skill. You can build listening skills using the right intention and techniques. Doing so offers you and others benefits that serve you for a lifetime.

Listening can improve relationships in every facet of daily life. It can strengthen your friendships and working relationships. It helps you build trust and shift your thinking.

Here are the five top benefits you'll find when you practice empathic listening:

Build stronger personal and professional relationships

Most relationships can improve with connection and understanding. Empathic listening gives you useful information for building interpersonal bridges. It can also help you navigate family dynamics and understand the other person's perspective.

Empathic listening can also help you in being a leader . Three quarters of people with highly empathic senior leaders report being often or always engaged. Only 32% of people with less empathic senior leaders report the same . You can use empathy to understand your teammates’ motivations and be better equipped to anticipate their needs. Listening is especially important for leaders in the digital age since most communication occurs without seeing the nonverbal cues of your coworkers.

One study in the Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies supports the idea that empathetic leadership improves performance and innovation . By becoming a better listener, your team may feel more connected to you because you strive to hear and understand them.

Improve communication and collaboration

We often celebrate leaders and loved ones for their ability to exchange information. The key word is exchange.

Strong communicators are eloquent speakers who also excel at listening. Empathic listening requires a higher level of this skill. Where eloquence helps convey information, empathy helps you accept it.

Empathic listeners tune into what others say (and what they don't). With deep listening, you can more easily navigate conversations and glean perspectives. This can help you reach a consensus faster and with fewer misunderstandings and roadblocks.

Increase trust and understanding

Trust grows when you believe someone is invested in your emotions and needs . By using empathic listening to understand the other party, you foster trust.

This emotional approach also allows you to be more vulnerable in return. The two-way flow of understanding and openness can help forge more trusting connections, learn how to fix a relationship , and rebuild trust.

Enhance conflict resolution and problem-solving

Conflicts often arise out of misunderstanding. Superficial listening can muddy understanding, and poor listeners can struggle with effective conflict resolution skills .

When you use empathic listening techniques, you're more likely to hear what's really meant. You can use this information to solve problems and help both parties reach a compromise. Empathic listening centers on compassion for others, which also helps tempers stay cool.

Challenge your perspective and widen your mindset

Preconceptions are another challenge in communication. Passive listening partly relies on what you think you know. Passivity uses assumptions as shortcuts in conversation, but it doesn't always work well.

Empathic techniques invite you to talk less and listen more . Taking on new information might shift your stance or change your perspective . In this way, empathic listening skills help you stay flexible and open to possibilities without defensiveness.

Empathic listening relies on a few simple but effective techniques and skills. When used together, these methods convey the right message to your discussion partner. They also give you the information needed to respond with empathy and compassion .

When building empathic listening skills, use the following techniques as you listen and respond.

1. Active listening

Active listening is an engagement behavior. It offers your partner your full concentration, understanding, and acknowledgment. Active listening silently says, "I'm with you," whether mentally, emotionally, or physically.

It's important to note the difference between empathy versus sympathy . Empathy involves understanding another person's feelings. Sympathy is when you feel sadness, pity, or sorrow on someone's behalf. Active listening is empathic rather than sympathetic.

To practice active listening, give the speaker your undivided attention. Put your phone in your pocket, free yourself from distractions, and make eye contact. Let the person know that you're ready to listen and engage. This frees you up to listen carefully and receive their messages (verbal and nonverbal) while building trust between you.

If your attention wanders during the conversation, acknowledge it. Center yourself back in the conversation and ask the speaker to proceed. Resist the urge to interrupt, defend, or rationalize. Ask questions at the right time, but leave room for your speaking partner to share.

2. Nonverbal cues and body language

Nonverbal cues are all the things you say without realizing it. They may include facial expressions, posture, gestures with your arms or hands , eye contact, and movement. Nonverbal cues help you understand a speaker's true feelings and intentions. They often reveal more than mere words let on.

For instance, if your partner displays that they are uncomfortable with what they're sharing, their body language will tell you. Fidgeting, looking away, rubbing hands, or other subconscious gestures are good clues.

Use this information to increase your empathy toward the speaker. Consider asking if they're comfortable discussing the topic. Knowing when it’s time to move away from a certain topic might even improve your connection over the long run.

3. Reflection and summarization

Paraphrasing or summarizing is when you repeat key information back to your speaking partner. Doing this shows that you're listening and engaging with what they have to say. It also helps clarify points to be sure you understand the information.

Reflection helps you stay on the same page in the conversation and reduce misunderstandings. It's also a great sign of attentiveness and care for the speaker's perspective. Reflection and summary are organic ways to deepen the emotional connection. They encourage open, honest, and connected dialogue between you and your discussion partner.

4. Open-ended questions

Most people love sharing about themselves, and open-ended questions are a way to say, "Tell me more!" Unlike closed, "yes or no" questions, open-ended questions prompt the speaker to elaborate.

Using open-ended questions helps you gain perspective and context and conveys your interest. When you ask open-ended questions, your partner knows they can relax and speak freely. In doing so, they may offer up more of their thoughts and feelings rather than only sticking to the facts. When asking questions, the structure of questions matters . For instance, “what” and “how” questions produce the best results. Try to avoid “why” questions.

5. Emotional validation

Emotional validation is when you accept another's feelings without judgment or dismissal. It highlights your respect for your speaker's emotional experiences. This reinforces their value and affirms their reality.

When you validate the speaker's emotions, you communicate understanding and empathy. Emotional validation is another great trust-builder and conflict-resolution strategy . It can help diffuse tense discussions by ensuring the speaker feels heard.

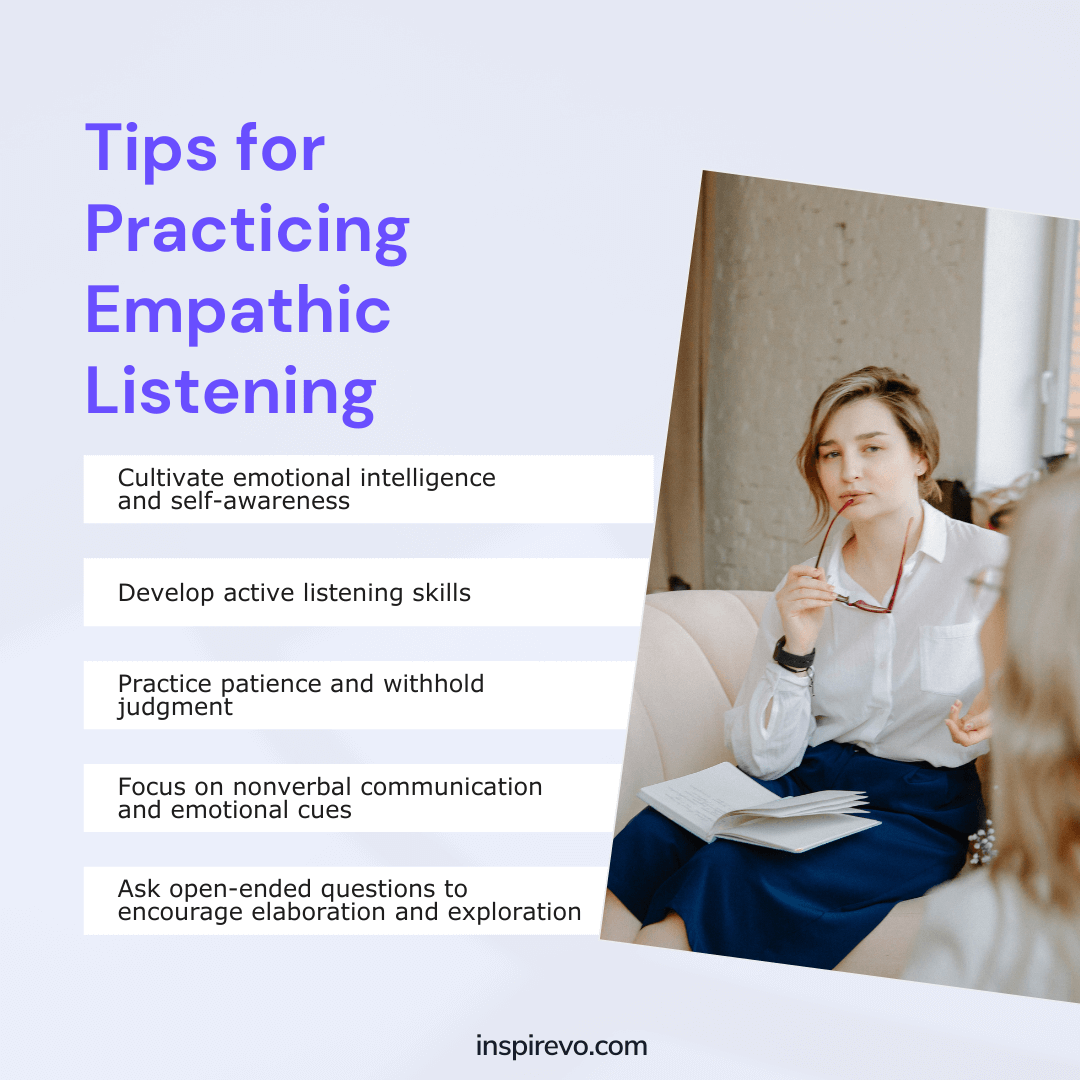

Like any skill, empathic listening improves with consistent practice. Once you know the techniques and methods of empathic listening, it's time to put them to use.

Here are three ways to flex your empathic listening skills in any setting:

Practice active self-awareness

Self-awareness isn't automatic. Tuning into your personal habits and behaviors takes time. When building empathic listening, take a step back and reflect.

Ask yourself some questions as a self-check, such as:

- Am I staying present , or is my mind wandering?

- Do I seem to be interrupting or rushing to add to the discussion?

- Am I making assumptions about what the other person is going to say before they finish speaking?

- Am I listening without judgment, or are my implicit biases creeping in?

- How can I show my discussion partner I’m interested in what they’re saying?

Recognizing the habits of empathic people is an important step toward change. Tuning into such aspects can help you break habits and recognize biases that color your interpretation. These biases are common, so don't feel bad when you spot them. They come from past experiences, stereotypes, or personal beliefs.

Becoming aware of your tendencies helps you set them aside. With a clear mind, you can approach each conversation with curiosity and compassion.

Explore your skills in various settings

To get better at empathic listening, it helps to practice your skills in many settings. Different areas of life call for different skills and boundaries, so variety makes for quicker improvement.

Remember that although you're opening yourself to communicate, it's OK to hold boundaries. Boundaries help you avoid burnout and negative feelings from toxic empathy and compassion fatigue .

Friends and family are a great audience for building better listening skills. Since you know these people best, your close bonds might create more preconceptions. By practicing active listening, you can check your preconceived notions and help your loved one feel truly heard.

Remember to ask open-ended questions to show genuine interest and care. As you listen with fresh ears, take time to reflect on the speaker's feelings. These techniques build a safe and supportive space to deepen connections and heal old conflicts.

At work

Practicing empathic listening with colleagues positively impacts the connection crisis at work . When you collaborate with empathy, you improve workplace communication skills and outcomes. If you’re a manager or boss, empathetic leadership can help move projects forward while letting everyone contribute their thoughts.

During conflict

Sometimes empathy is most difficult when it's most needed. If you're in a tense discussion or disagreement, you may slip into old patterns of defensive speech or judgmental listening. Take the time to acknowledge the other's feelings without bias.

Check in on your reactions and seek to understand their perspective. This means putting aside your own viewpoints to engage with their feelings. Empathic listening during conflict can feel difficult, vulnerable, or frustrating, but it's a valuable practice. It can de-escalate tension, foster respect, and bring about constructive resolutions. According to this study published by the Royal Society, empathy can make us more prosocial and make us more open to reconciliation when problems arise.

Seek feedback (ask trusted individuals for honest input)

If you want to improve your listening skills, ask for feedback . While this may feel scary or increase feelings of vulnerability , feedback is essential to progress.

Ask someone you trust, such as friends, family, or colleagues, to offer candid observations on how empathically you listen. Prepare your mindset to accept their views without reaction or rationalization. Their honest insights are a great source of guidance and opportunity.

Be sure to ask them to outline your strong points as well as your challenges. Thank them for their candor, reflect on what they've said, and consider whether you want to incorporate their feedback into your practice.

Empathic listening lets you hear others on a deep, emotional level. It’s a powerful way to grow together with them, whether at home or on the job. With practice, you can use empathic listening to excel at work, mend fences, and become a better friend, loved one, or partner.

If you're ready to improve your listening skills with the help of an expert, consider coaching. A certified coach can help you build communication skills and practice your technique. Find the right coach for you and get started today.

Understand Yourself Better:

Big 5 Personality Test

Belynda Cianci

Belynda is a freelance content writer with 15+ years of experience writing for the SaaS, technology, and finance industries. She loves helping scrappy startups and household names connect with the right audiences. Away from the office, Belynda enjoys reading and writing fiction, singing, and horseback riding. Her favorite activity is traveling with her husband and children. Belynda holds a B.A. in English from Northeastern University.

7 types of listening that can change your life and work

How to improve your listening skills for better communication, active listening: what is it & techniques to become an active listener, understanding the difference between sympathy and empathy, talk less, listen more: 6 reasons it pays to learn the art, the importance of listening as a leader in the digital era, the 12 best business podcasts and why to tune in, learn 6 habits of empathetic people to connect deeper, what are the emotional triggers for empaths to watch for, eye contact is important (crucial really) in communication, 7-38-55 rule of communication: how to use for negotiation, how to identify and overcome communication barriers at work, foster strong communication skills to enjoy professional success, what’s an empath the positives and pitfalls, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead™

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care®

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Personal Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

How to Improve Your Empathic Listening Skills: 7 Techniques

Social and personal complexities have amplified anxiety and depression, pushing people to their limits.

How can we help a hurting person? Beyond basic survival, people need a sense of belonging and to feel safe, valued, and respected.

There is good news. Each of us can offer relief to a hurting person.

Author Josephine Billings stated:

“To the world you may be one person, but to one person you may be the world.”

Leal, 2017, p. 32

Empathic listening allows us to step inside the speaker’s story to feel their emotions. It provides a safe place to work through complicated emotions.

What does the empathic listener get from their effort? Besides helping someone, you may be creating a legacy of compassion.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Communication Exercises (PDF) for free . These science-based tools will help you and those you work with build better social skills and better connect with others.

This Article Contains:

What is empathic listening 2 examples, the 4 stages of empathic listening, empathic listening vs active listening, carl rogers’s take on empathic listening, how to improve your empathic listening skills, 7 techniques and tips for counselors, 19 examples of questions to ask your clients, best exercises, activities, and games, most fascinating books on the topic, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

Stephen R. Covey (2020, p. 277), author of The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People , summarizes the heart of empathic listening: “Seek first to understand.” Covey calls this a deep paradigm shift, as most people force their own perspective before attempting to listen.

Covey believes empathic listening begins with the type of character trait that inspires the speaker to open up and trust the listener. Humility , for instance, is a character trait that instills trust. Covey talks about building an emotional bank account with the person before they’re willing to trust. The same concept in restorative justice is known as social capital .

Covey believes we typically listen at one of four levels:

- Ignoring the other person

- Pretending to listen

- Selective listening

- Attentive listening

Covey states there’s a fifth level of listening:

Empathic listening

Empathic listening seeks to get inside the other person’s perspective and see the world the way they do. This skill requires the listener to use their eyes, ears, and heart to listen.

Parenting as an example

Being a parent can be an optimal opportunity for empathic listening.

Child: “I don’t like soccer anymore. The coach confuses me and the team sucks.”

The parent might typically refute the child’s assertion. But a different response might be:

Parent: “Sounds like you’re frustrated with your soccer team.”

Coworkers as an example

The workplace is also filled with opportunities for empathic listening. Imagine your coworker comes into your office with a complaint.

Coworker: “Hal (supervisor) is an idiot. He doesn’t know what he’s doing, and he gives me horrible assignments.”

Listener: “Sounds like you’re irritated with Hal and work right now.”

In both instances, the listener doesn’t negate or judge the speaker. They let the speaker know they heard what was said and captured the emotions.

According to Covey (2020), there are four stages of empathic listening, outlined below:

Stage 1: Mimicking content

This is the least effective stage of listening taught in active or reflective listening courses.

Stage 2: Rephrasing the content

This is somewhat more effective but remains limited to the verbal portion of communication.

Stage 3: Reflecting feelings

This stage includes not only what was said, but how the speaker feels about it.

Stage 4: Rephrasing content and reflecting feelings

This stage incorporates both the second and third stages of the golden nugget of communication. Covey describes this stage as giving the speaker psychological air .

Rephrasing content and reflecting feelings draws the speaker closer to the listener, reassuring them they are in a safe space. The barrier between the parties is removed for what Covey describes as soul-to-soul flow , which includes trust and vulnerability.

Download 3 Communication Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to improve communication skills and enjoy more positive social interactions with others.

Download 3 Free Communication Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

In the field of communication, there are various types of listening. Some require more skill and patience than others.

Active listening

Active listening is identified as a way of listening instead of a type of listening. This listening method focuses entirely on what the other person is saying. The listener then confirms the content of what was heard and the feelings the speaker projects about the message (Hybels & Weaver, 2015).

Some characteristics of active listeners include good eye contact, undivided attention, and patience. The active listener’s demeanor helps the speaker feel respected (Hybels & Weaver, 2015).

This type of listening includes the mechanics of active listening and takes the listener a step further. The empathic listener begins with the intent to immerse themselves fully in the other person and what they are experiencing.

Applying empathic listening techniques includes emptying ourselves of the need to be right and our individual autobiography, as our personal narratives may interfere with the speaker’s story (Covey, 2020).

This video by Roma Sharma provides examples of autobiographical listening and empathic listening and how to prepare to be a deep listener.

Another way to think about empathic listening is to project yourself into the other person’s life, which includes suspending your own ego and judgment (Hybels & Weaver, 2015). I have found this to be one of the most challenging aspects of being a mediator. It requires centering myself with reminders that my job is to listen and to be fully present.

In addition to supporting the speaker, the empathic listener creates intimacy by listening, identifying feelings, and allowing the speaker to find solutions. Empathic listeners know how important it is for speakers to both own and solve their own issues (Hybels & Weaver, 2015).

It’s Not About the Nail is a comical video about a speaker who cannot see her own issue. Although the listener can clearly see the problem, he learns that the conversation is about listening and validating the speaker, not fixing the issue.

He is careful to make it clear from the outset that being empathetic is a “complex, demanding, and strong—yet also subtle and gentle—way of being” (Rogers, 1980, p. 143).

He describes it as a multi-faceted process rather than a state where the listener is “entering the private perceptual world of the other and becoming thoroughly at home in it” (Rogers, 1980, p. 142). It involves a moment-to-moment sensitivity of the speaker’s feelings and temporarily living within the life of the other without judgment.

Another aspect includes being aware of unconscious feelings the speaker may have but taking care not to divulge something that may be below the speaker’s conscious level, posing a threat to them.

In addition, the listener is sensing the person’s world through fresh eyes, particularly threatening aspects, and checking in with the person about what is being sensed.

The empathic listener becomes “a confident companion to the person in his or her inner world” (Rogers, 1980, p. 142). In order to do so, the listener has put aside subjective views and values to enter into their world without the prejudices that accompany them, in essence, laying yourself aside for the time being.

Rogers believed this way of being is not for everyone. The empathic person must know themselves well and be solidly grounded enough to avoid getting lost in the other person’s strange or bizarre world.

It can be complicated to cease embedded behaviors, such as judging and evaluating. One idea is to replace judgment with curiosity. Curiosity changes perspectives, allowing us to approach the situation from a different vantage point.

Becky Harling (2017) shares her listening recommendations, including remembering the story the speaker has told and demonstrating that you value what they’ve shared. She points out that people struggle with insecurities, and advice, as opposed to empathic listening, often adds to their insecurities. She goes on to suggest the listener might verbally acknowledge their courage for sharing their challenge.

According to Michael Sorensen, author of I Hear You: The Surprisingly Simple Skill Behind Extraordinary Relationships , “The truly good listeners of the world do more than just listen. They listen, seek to understand, and then validate. That third point is the secret sauce—the magic ingredient” (Sorensen, 2017, p. 18).

Validating the emotions of the speaker demands the listener’s full attention and observation. The listener must listen to the words and observe the body language.

Sorensen also suggests the listener mirror the speaker’s excitement when responding, offer micro-validations such as “really” and “that makes sense” to show they’re listening, and stop judging our own emotions.

This loss of control can be scary and unpredictable. Perhaps this is why it’s so difficult to prepare for empathic listening.

Bento Leal (2017), author of 4 Essential Keys to Effective Communication in Love, Life, Work – Anywhere! , provides the foundation and steps for empathic listening.

Included in his 12-day communication challenge to better communication are several steps that build upon one another for excellent communication skills. Each day ends with a reflection.

Leal’s approach to empathic listening is unique in that he meticulously outlines the internal perspective needed to prepare for the interaction.

Empathic awareness skills

- Recognize the inherent dignity and value in myself as well as the speaker.

- Instill a personal desire to want to listen to others.

- Think of positive qualities of the other person.

Empathic listening skills

- Transform my listening skills and quiet my mind.

- I will listen through the words, fully and openly.

- I vow not to interrupt people.

- Say back to the speaker what they said to me, capturing the emotion.

Leal also offers tips for empathic speaking, including organizing and clarifying thoughts prior to speaking, choosing words wisely, and expressing words with respect. Finally, he suggests speaking carefully and clearly.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Before asking your client or the speaker questions, it is wise to be sensitive to their disposition and have a deep awareness of the context. Not all questions are appropriate in every situation.

Questions can help the listener focus and convey their narrative. The following examples can help the listener open up.

- “You seem upset. Do you want to talk?”

- “Tell me what happened.”

The listener can clarify what they heard. Ideas include:

- “You sound frustrated.” (‘Frustrated’ can be replaced with any emotion, such as angry, sad, or fearful.)

- “How do you feel about this?”

- “How did you react?”

- “When did that happen?”

- “How did you feel when they said that?”

- “What do you think they meant by that?”

- “In what ways does this bother you the most?”

- “What do you do when that happens?”

- “Do you know why they did that?”

- “Have you experienced a similar situation in the past?”

- “How did you handle it?”

- “What was it that caused you to feel that way?”

- “Do you know what they want from you?”

Some ideas to let the listener know you are there for them, include:

- “What can I do for you?”

- “That sounds really hard.”

- “How can I best support you?”

- “What do you need right now?”

The steps begin with putting yourself in the other person’s shoes and fact checking past conversations.

Step three advises the listener to give their full attention and consider if clarification is needed. The last two steps include clarifying what they’ve said and possibly having the speaker clarify what they heard you say.

Creating an Empathy Picture can be used as an exercise or game and is appropriate for any age group. This activity incorporates imagination and creativity by having participants cut out pictures from magazines or other sources and paste them onto a large sheet of paper.

Once the poster boards are ready, group members are asked to imagine who the people are and what is going on in their life, using prompts such as:

- What decision does this person need to make today?

- What are others telling them to do?

The 500 Years Ago worksheet is a role-play exercise that encourages the speaker to speak on the listener’s level. The role of the listener is to imagine themselves as someone from 500 years in the past.

The speaker then describes to the listener a modern object such as a laptop or cell phone for which the listener from the Middle Ages would have no reference. This role-play uses imagination and empathy for the listener.

Improving your communication with empathic listening skills does not happen overnight. These books will guide you with practical applications.

1. I Hear You: The Surprisingly Simple Skill Behind Extraordinary Relationships – Michael S. Sorenson

His position on the success of empathic listening relies heavily on validating emotions. He posits a four-step process, which includes validating and re-validating the emotion.

Another component posited by Sorensen in I Hear You is for the listener to mirror the speaker’s energy when responding. This includes emotions such as excitement and melancholy.

Sorensen reiterates something commonly known but often forgotten about emotions , which is that they’re neither good nor bad; they’re information about a situation.

Sorensen offers the reader unique tips on learning to empathize with people, such as imagining them as a child and ceasing to judge our own emotions.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. 4 Essential Skills to Effective Communication in Love, Life, Work—Anywhere! – Bento C. Leal III

This book reads like a pocket guide for learning to communicate more effectively.

Leal begins by acknowledging the uniqueness of each human being and how we must first prepare ourselves for empathic listening through recognizing our own and others’ value.

Particularly useful is his realignment formula of Pause–Reflect–Adjust–Act for various situations, such as a wandering mind. Another great reminder is that intentions precede actions; preparation prior to the conversation sets the stage for success.

In addition to tips on preparing to listen, Leal also includes tips for empathic speaking, expressing yourself when you’re upset, and encouraging others in your life through Applaud, Admire, Appreciate .

17 Exercises To Develop Positive Communication

17 Positive Communication Exercises [PDFs] to help others develop communication skills for successful social interactions and positive, fulfilling relationships.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Mindful Listening is a listening exercise aimed at children to achieve a couple of objectives. It helps them slow down, pay attention and become more aware.

The Create a Care Package worksheet provides experiential insight into people’s lives by challenging them to consider which objects, possessions, and people are integral in the lives of others.

Partners are asked to imagine having to leave behind all but a few items from your current life. Partners then take turns identifying the items they would take to their new life and why.

The Trading Places worksheet invites clients to view things from a variety of perspectives. This worksheet can be particularly useful for clients struggling to see eye to eye with another person, keeping them stuck in conflict.

It includes ten steps to help develop empathy , beginning with grounding yourself in the present moment. Subsequently, clients are asked to walk through feelings involved in difficult interactions while alternating between past and present.

In addition, the worksheet encourages the client to consider and record feelings the other person might be experiencing through their interactions.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others communicate better, this collection contains 17 validated positive communication tools for practitioners. Use them to help others improve their communication skills and form deeper and more positive relationships.

Empathic listening is the embodiment of connection and a foundation for healing hurting people.

According to Elizabeth Segal, social empathy (insight into the plights and realities of others’ lives) is waning (Kilty, Hossfeld, Kelly, & Waity, 2018). If it continues to decrease, social bonds will be weakened, rendering compassion at risk.

Empathy gives compassion wings.

After my dad passed away in 2020, people told us what a great listener he was. He didn’t attempt to control the conversation. He didn’t judge or try to fix issues. He was a strong and steady presence for others.

Maya Angelou said:

“People will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel.”

Gallo, 2014

Such an indelible legacy.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Communication Exercises (PDF) for free .

- Covey, S. R. (2020). The 7 habits of highly effective people . Simon & Schuster.

- Cuddy, A. (2015). Presence: Bringing your boldest self to your biggest challenges . Little, Brown and Company.

- Gallo, C. (2014). The Maya Angelou quote that will radically improve your business . Forbes.com. Retrieved September 21, 2021, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/carminegallo/2014/05/31/the-maya-angelou-quote-that-will-radically-improve-your-business/?sh=61ea5945118b

- Harling, B. (2017). How to listen so people will talk . Bethany House.

- Kilty, K. M., Hossfeld, L., Kelly, E. B., & Waity, J. (2018). Poverty and class inequality. In A. J. Trevino (Ed.), Investigating social problems (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Hybels, S., & Weaver, R. L. (2015). Communicating effectively (11th ed.). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Leal, B. C., III (2017). 4 Essential keys to effective communication in love, life, work—anywhere! Author.

- Rogers, C. (1980). A way of being . Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Sorensen, M. S. (2017). I hear you: The surprisingly simple skill behind extraordinary relationships . Autumn Creek Press.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Excellent article and very complete. Thanks for sharing it. Wishing the best in your professional journey!!

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Analyzing & Interpreting Your Clients’ Body Language: 26 Tips

Darwin was one of the first individuals to explore the concept of body language in Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. He studied [...]

How to Say No & Master the Art of Personal Freedom

In a world that often values compliance over authenticity, the notion of personal freedom becomes not just a luxury but a necessity for our wellbeing [...]

Conflict Resolution Training: 18 Best Courses and Master’s Degrees

All humans have some things in common. We all need air to breathe and water to stay alive. We are all social beings, and if [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (52)

- Coaching & Application (39)

- Compassion (23)

- Counseling (40)

- Emotional Intelligence (21)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (18)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (16)

- Mindfulness (40)

- Motivation & Goals (41)

- Optimism & Mindset (29)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (23)

- Positive Education (36)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (16)

- Positive Parenting (14)

- Positive Psychology (21)

- Positive Workplace (35)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (20)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (29)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (33)

- Theory & Books (42)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (54)

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Personal Development Seminar

- Stress Management

- Self Development & Transformation

The Empathic Listener’s Guide: Elevating Relationships through Understanding

As an empathic listening expert, I have seen the transformative power of this communication technique firsthand. Empathic listening is a method of active listening that involves focusing on understanding another person’s perspective and emotions without judgment or interruption. It allows for deeper connections and more meaningful conversations.

Empathic listening goes beyond simply hearing someone speak; it requires a willingness to truly listen and understand their point of view. This type of listening can be used in personal relationships, professional settings, or even during difficult conversations such as conflicts or disagreements. In this detailed guide, we will explore what empathic listening is, how it works, and provide practical tips for implementing it into your daily communication practices.

Defining Empathy

Empathy is often confused with sympathy, but they are not the same thing. Sympathy is when we feel sorry for someone, while empathy is when we put ourselves in another person’s shoes and try to understand how they’re feeling.

Empathy plays a crucial role in relationships because it allows us to connect with others on a deeper level. When we listen empathically, we show that we care about what the other person is saying and that we value their feelings. This can help build trust and create stronger bonds between people.

It’s important to note that empathy isn’t just about understanding someone’s emotions – it also involves validating those emotions. When we validate someone’s feelings, we acknowledge that their experiences are real and meaningful to them. This can be incredibly powerful in building positive relationships as it creates a safe space for individuals to express themselves without fear of judgment or dismissal.

The Importance Of Active Listening

Active listening techniques are crucial for effective communication strategies. When we actively listen, we show the speaker that we care about their thoughts and feelings. This type of approach encourages them to share more with us in a safe space where they feel heard and valued.

One way to practice active listening is by using nonverbal cues such as nodding or making eye contact.

These actions demonstrate our attentiveness and genuine interest in what the speaker is saying. On top of this, repeating back certain phrases can also be helpful since it shows that you are truly understanding and processing their words.

Another useful technique when practicing active listening is asking open-ended questions. Instead of just responding with simple yes or no answers, these questions encourage dialogue which further deepens your relationship with the speaker. Ultimately, taking time to actively listen will not only improve your own communication skills but also foster healthier personal connections with those around you.

The Difference Between Empathy And Sympathy

As we discussed in the previous section, active listening is crucial for effective communication. However, empathic listening takes it a step further by not only hearing what someone is saying but also understanding their emotions and perspective. Empathy in relationships can lead to deeper connections and more meaningful conversations.

In healthcare settings, empathic listening is especially important as patients are often dealing with physical or emotional pain . A healthcare provider who practices empathic listening can create a safe space for their patient to open up about their concerns and fears. This can ultimately lead to better treatment outcomes as the patient feels heard and understood.

Empathic listening involves using reflective statements that show you understand how the other person is feeling. It’s important to remember that empathy does not mean agreeing with someone’s point of view but rather acknowledging it and validating their experience. When practicing empathic listening, try to put yourself in the other person’s shoes and listen with an open mind and heart. By doing so, you may find that your relationships become stronger and more fulfilling.

The Benefits Of Empathic Listening

Empathic listening is a powerful tool that can greatly enhance relationships and improve emotional intelligence. The benefits of empathic listening are numerous, as it enables individuals to connect with others on a deeper level. When we listen empathically, we not only hear what someone is saying, but we also strive to understand their feelings and perspective.

Improved relationships are one major benefit of empathic listening. By actively engaging in this type of listening, individuals demonstrate that they care about the other person’s thoughts and emotions. This creates an atmosphere of trust and mutual respect, which fosters strong bonds between people. Empathic listening helps us become better communicators by allowing us to effectively convey our own thoughts and feelings while simultaneously understanding those of others.

Another key benefit of empathic listening is heightened emotional intelligence.

As we learn to tune into the needs and emotions of others through active listening, we become more attuned to our own feelings as well. This self-awareness allows us to make conscious decisions about how we interact with others and respond appropriately in various situations. Ultimately, this leads to greater success both personally and professionally.

By taking the time to truly listen and understand others, we create opportunities for growth and connection that might otherwise be missed. Empathic listening has far-reaching benefits that extend beyond just improving individual relationships; it promotes a culture of empathy and compassion that can positively impact society as a whole.

The Role Of Nonverbal Communication

As we learned in the previous section, empathic listening has numerous benefits for both the listener and speaker. However, it’s important to understand that effective empathic listening involves more than just hearing someone out. Nonverbal cues play a crucial role in communication and active engagement is key.

Did you know that over 50% of communication actually comes from nonverbal cues? This means that as an empathic listener, paying attention to body language, facial expressions, and tone of voice is just as important as actively listening to what someone is saying. By doing so, you can gain a deeper understanding of their emotions and perspective.

To effectively use nonverbal cues during empathic listening, try these three techniques:

- Maintain eye contact without staring.

- Nod or make other appropriate gestures to show you are engaged.

- Pay attention to the speaker’s posture and movements.

By incorporating these techniques into your empathic listening skills, you will be better equipped to truly connect with others on a deeper level and build stronger relationships based on trust and understanding.

It cannot be stressed enough how vital it is to actively engage with those who are speaking by using both verbal and nonverbal cues. When done correctly, this type of communication can have profound effects on individuals’ mental health and overall well-being. So next time you find yourself in a conversation where someone needs support or simply wants to be heard, remember the importance of utilizing nonverbal cues while actively engaging with them through empathic listening techniques.

Cultivating A Safe And Supportive Environment

Creating a safe and supportive environment is crucial when practicing empathic listening. This means setting boundaries for yourself and the person you are communicating with. It’s important to establish what is acceptable behavior before engaging in any conversation, especially if it involves sensitive or emotional topics.

Navigating emotional responses can be challenging, but it’s necessary to create an environment where individuals feel comfortable expressing themselves without fear of judgment or retribution. As an empathic listener, it’s essential to remain calm and composed even when confronted with strong emotions. Acknowledge the other person’s feelings and validate them by paraphrasing what they have said.

A helpful tool to ensure a safe space is using nonverbal cues such as nodding your head, maintaining eye contact, and leaning forward slightly towards the speaker. These actions demonstrate that you are present and actively engaged in the conversation. Remember that creating a supportive environment requires ongoing effort from both parties involved in the dialogue. By establishing clear boundaries and navigating emotional responses effectively, we can foster an atmosphere where empathy thrives organically.

| Creating Boundaries | Navigating Emotional Responses | Active Listening |

|---|---|---|

| Establishing limits on subject matter | Acknowledging feelings without judgement | Demonstrating engagement through body language |

| Setting expectations for respectful communication | Validating concerns by repeating back key points | Providing feedback throughout |

| Encouraging open dialogue while ensuring safety | Remaining calm during difficult conversations | Asking clarifying questions |

Remember that everyone has different needs when it comes to feeling safe and supported during communication. Adapting our approach based on individual preferences will help us become better empathetic listeners overall. By consistently cultivating a welcoming space, we encourage others to speak their truth freely while promoting mutual understanding and connection between all parties involved.

Asking Open-Ended Questions

As the saying goes, “We have two ears and one mouth so that we can listen twice as much as we speak.” This is especially true in empathic listening. Asking open-ended questions is an essential part of this process because it allows us to deepen our understanding of the speaker’s emotions, thoughts, and experiences.

Examples of open-ended questions include: “ Can you tell me more about how that made you feel?” or “What was going through your mind when that happened?” These types of questions invite the speaker to share more information, which helps build trust and rapport between the listener and speaker.

To effectively use open-ended questions in empathic listening, it’s important to listen actively and attentively.

Pay attention not only to what the speaker is saying but also their facial expressions, tone of voice, and body language. U se these cues to guide your questioning and show empathy towards them . Avoid interrupting or giving advice unless explicitly asked for – instead focus on reflecting back what they’re saying with phrases like “It sounds like…” or “If I’m hearing you correctly…”

Remember, asking open-ended questions isn’t just a technique – it’s a mindset. By genuinely wanting to understand someone else’s perspective without judgment or interruption, we can create meaningful connections with those around us.

Reflecting Feelings And Emotions

Reflecting feelings and emotions is a crucial component of empathic listening. It involves actively listening to the speaker’s words, tone, body language, and emotional cues and then reflecting back what you hear in a way that shows understanding and empathy.

It’s important to note that there is a difference between reflecting and parroting. Parroting simply repeats the speaker’s words verbatim, whereas reflecting takes into account the underlying emotions and meaning behind those words. When we reflect someone’s feelings and emotions, we are showing them that we not only heard what they said but also understand how they feel.

In conflict resolution, reflecting feelings can be especially powerful. By acknowledging another person’s emotions, even if we don’t agree with their perspective or actions, we show respect for their experience and help de-escalate the situation. This technique can help both parties come to a mutual understanding and find common ground.

Tips for Reflecting Feelings:

- Pay attention to nonverbal cues like facial expressions and body language.

- Use phrases such as “I sense that you’re feeling…” or “It sounds like you’re experiencing…

Benefits of Reflecting Feelings:

- Builds trust between speakers

- Helps create an emotionally safe space where individuals can open up without fear of judgement

Overall, reflecting feelings during empathic listening requires active engagement with the other person by paying close attention to verbal and nonverbal communication. Through this reflective process, people will feel understood which leads towards positive outcomes in relationships or conflict resolutions.

Avoiding Judgment And Assumptions

Reflecting feelings and emotions is an essential aspect of empathic listening. By acknowledging the other person’s emotional state, we can create a safe space for them to share their thoughts and experiences. However, reflecting alone may not be enough to fully understand what someone is trying to convey. Active listening techniques such as avoiding assumptions are also crucial.

Assumptions can hinder our ability to truly listen and comprehend what someone else is saying.

It’s important to recognize that everyone has unique perspectives and experiences, so assuming we know what they’re thinking or feeling can lead to misunderstandings. Instead, we should focus on asking open-ended questions and clarifying statements to ensure we have a clear understanding of the speaker’s intended message.

To become better listeners, we must adopt active listening techniques that go beyond just reflection. One effective technique is paraphrasing- restating in your own words what you think the speaker said. This ensures both parties are on the same page and helps prevent misinterpretations. Another technique is summarizing- recapping key points made by the speaker at appropriate times. Finally, nonverbal cues like maintaining eye contact and nodding help show engagement in conversation.

| Active Listening Techniques | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Paraphrasing | Restating in your own words what you think the speaker said | “So it sounds like you’re saying…” |

| Summarizing | Recapping key points made by the speaker at appropriate times | “Let me see if I’ve got this right…” |

| Nonverbal Cues | Using body language (e.g., eye contact, nodding) to indicate engagement | Maintaining eye contact while leaning slightly forward during a talk |

Overall, empathic listening requires us to actively engage with others through reflective and active listening techniques while avoiding assumptions about their perspective or intentions. By doing so, we create an environment where people feel heard and understood, leading to more meaningful connections.

Practicing Mindfulness

When it comes to empathic listening, mindfulness is a crucial component. Practicing mindfulness means being fully present and engaged in the moment without judgment or distraction. This level of awareness allows us to tune into others on a deeper level, understanding not only their words but also their tone, body language, and emotions.

One way to cultivate mindfulness is through mindful breathing exercises. Mindful breathing involves focusing your attention on your breath as you inhale and exhale slowly and deeply. By doing this, you can reduce stress levels, increase emotional regulation, and improve overall well-being . Incorporating mindful breathing into your daily routine can help you become more attuned to yourself and those around you.

Another effective technique for practicing mindfulness is through regular meditation sessions.

Mindfulness meditation involves sitting quietly and paying attention to your thoughts and feelings as they arise without getting caught up in them or judging them. With practice, this technique helps you develop greater self-awareness, compassion for others, and an ability to remain calm even in challenging situations. Adopting these practices will allow you to hone your empathy skills while becoming more grounded in the present moment.

Dealing With Difficult Conversations

Did you know that 90% of people avoid having difficult conversations altogether? It’s a staggering statistic, but it’s understandable. Dealing with conflict and confrontation can be uncomfortable, especially when emotions are running high. However, avoiding these tough talks only leads to further problems down the line.

As an empathic listening expert, I’ve seen firsthand the benefits of using this skill during difficult conversations. Here are three strategies for navigating those challenging discussions :

- Practice active listening: When someone is upset or angry, they need to feel heard and understood. Take time to listen actively by summarizing what they’re saying and asking open-ended questions like “what else do you want me to understand?” This shows them that you care about their perspective and creates space for a productive conversation.

- Use “I” statements instead of “you” statements: Starting sentences with “you” can come across as accusatory or confrontational, putting the other person on the defensive. Instead, use phrases like “I feel” or “I think,” which express your own thoughts without attacking theirs.

- Be willing to compromise: In any disagreement, there will likely be some common ground where both parties can find agreement. Look for areas where you can give a little in order to move forward together.

By implementing these strategies for difficult conversations alongside empathic listening techniques, you’ll not only resolve conflicts more effectively but also build stronger relationships based on mutual respect and understanding.

Building Trust And Rapport