Empirical Research: Advantages, Drawbacks and Differences with Non-Empirical Research

Based on the purpose and available resources, researchers conduct empirical or non-empirical research. Researchers employ both of these methods in various fields using qualitative, quantitative, or secondary data. Let's look at the characteristics of empirical research and see how it is different from non-empirical research.

The empirical study is evidence-based research. That is to say, it uses evidence, experiment, or observation to test the hypotheses. It is a systematic collection and analysis of data. Empirical research allows researchers to find new and thorough insights into the issue. Mariam-Webster dictionary defines the word "empirical" as:

"originating in or based on observation or experience"

"relying on experience or observation alone often without due regard for system and theory"

"capable of being verified or disproved by observation or experiment"

Unlike non-empirical research, it does not just rely on theories but also tries to find the reasoning behind those theories in order to prove them. Non-empirical research is based on theories and logic, and researchers don't attempt to test them. Although empirical research mostly depends on primary data, secondary data can also be beneficial for the theory side of the research. The empirical research process includes the following:

- Defining the issue

- Theory generation and research questions

- If available, studying existing theories about the issue

- Choosing appropriate data collection methods such as experiment or observation

- Data gathering

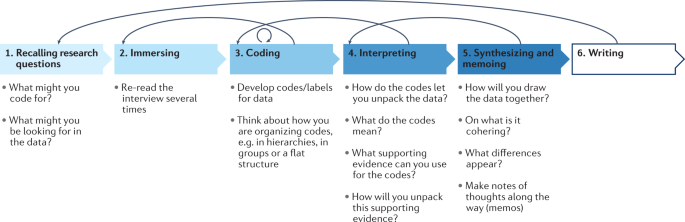

- Data coding , analysis, and evaluation

- Data Interpretation and result

- Reporting and publishing the findings

Benefits of empirical research

- Empirical research aims to find the meaning behind a particular phenomenon. In other words, it seeks answers to how and why something works the way it is.

- By identifying the reasons why something happens, it is possible to replicate or prevent similar events.

- The flexibility of the research allows the researchers to change certain aspects of the research and adjust them to new goals.

- It is more reliable because it represents a real-life experience and not just theories.

- Data collected through empirical research may be less biased because the researcher is there during the collection process. In contrast, it is sometimes impossible to verify the accuracy of data in non-empirical research.

Drawbacks of empirical research

- It can be time-consuming depending on the research subject.

- It is not a cost-effective way of data collection in most cases because of the possible expensive methods of data gathering. Moreover, it may require traveling between multiple locations.

- Lack of evidence and research subjects may not yield the desired result. A small sample size prevents generalization because it may not be enough to represent the target audience.

- It isn't easy to get information on sensitive topics, and also, researchers may need participants' consent to use the data.

In most scientific fields, acting based solely on theories (or logic) is not enough. Empirical research makes it possible to measure the reliability of the theory before applying it. Researchers sometimes alternate between the two forms of research, as non-empirical research provides them with important information about the phenomenon, while empirical research helps them use that information to test the theory.

- Earth Science

- Physical Science

- Social Science

- Medical Science

- Mathematics

- Paleontology

What are the Advantages and Disadvantages of Empiricism

Empiricism is the theory of knowledge that claims that most or all our knowledge is obtained through sensory experience, rather than through rational deduction or innateness. Empiricists such as John Locke and David Hume emphasize the role of evidence and experience as the main way of justifying our knowledge claims. Therefore knowledge gained a priori is considered by empiricists to be inferior to knowledge gained a posteriori. John Locke, along with many other empiricists, postulated the idea of Tabula Rasa, or the argument that we are a blank slate at birth and all the ideas and concepts that we have, build up as we experience more and more things.

The main strength of using empiricism as a way of finding truth is that rationalism doesn’t necessarily account for the way that the world really works, whereas empiricism does. Empiricism is widely used in science as a method of proving and disproving theories. This is backed up by Galileo who stated that beliefs must be tested empirically in order to check that they work within the laws of physics. An example of this is Aristotle’s theory of motion in which he used rational thought to explain the motion of objects. He argued that each of the four terrestrial (or worldly) elements move toward their natural place and that heavier things fell faster than lighter things. Galileo disputed this, arguing that it was air resistance that was responsible for how fast things fell. This was later tested empirically on the moon when an astronaut dropped a feather and a hammer and they hit the ground at the same time. This is a strong argument for empiricism because it shows that it is much easier to see if something is true if it is tested than if reason is used alone.

However, rationalists dispute the role of empirical evidence based on its claim that we can acquire knowledge through our senses. This is because sense data is indirect and there has to be mediation between sensation and perception. There is also no way of knowing if what we are seeing is reality. Many people have experienced hallucinations or lucid dreams in their lives, in which they have been convinced of the existence of things that don’t exist. If it feels like reality while you are in the dream, how do you know what you’re experiencing now isn’t also a dream? Descartes was a rationalist and argued that there is no way of knowing if the things we are seeing and experiencing are real. If this is the case, we cannot claim to have knowledge that when we saw the hammer and the feather fall at the same speed, that this was actually the case. The only thing, according to rationalists, that we can be sure of are things that logically cannot fail to be true and only our rational minds can provide us with this information. Empiricism cannot be proved to be accurate.

David Hume argues against the claim that sense data is not accurate. A strong argument supporting Hume’s empiricism is that rationalism can only link ideas, whereas empiricism can link facts and is therefore a more useful tool in justifying knowledge claims. Under normal circumstances our senses do not lie and the more we repeat something the better idea we have of it. Rationalism is not useful in proving things to be true because it relies on logic that may or may not be true in itself and cannot account for the real world. Empiricism claims that experience can show whether a phenomenon repeats itself and therefore it abides by certain laws or it happened randomly, which is why it can be considered such a good foundation as a way of uncovering and proving facts. Rationalism, on the other hand, can only give us ideas, that may appear to be correct at first but without experimentation there is no way of telling whether the claim is correct.

Although empiricism is strong in the subject of physics, it cannot be used for complicated mathematics and algebra. Some mathematical equations are impossible to prove using the empiricist method because there is no physical way of showing the complications of the equation in an observational experiment. Rationalism solves this problem by using logic to suggest that whilst some things cannot be tested in the real world, they cannot logically fail to be true. This is true in the case of not just mathematics, but a lot of science. There are some things that at this moment in time cannot be tested scientifically, but a working hypothesis has still been created and only rationalism could have produced this. For instance, if we use the example of Galileo who disproved Aristotle’s theory of motion without having the ability of physically going to the moon and testing it himself. He did this by using noticing the logical fallacy of Aristotle’s argument and correcting it so that it was more coherent. Empiricism is only useful if it is possible for one to actually experience something and as there is much we cannot experience ourselves, rationalism is an important source for a great deal of knowledge.

Overall, it is clear that empiricism has both strengths and weaknesses. It is vital in our understanding of the world and in proving or disproving beliefs, but it cannot be used for everything, especially for answering questions based on intangible things such as the mind or theoretical mathematics. For these kinds of things rationalism would be better used and the most justified knowledge claims are those that cohere to both rational thought and empirical evidence.

Related posts:

Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

Empirical research relies on gathering and studying real, observable data. The term ’empirical’ comes from the Greek word ’empeirikos,’ meaning ‘experienced’ or ‘based on experience.’ So, what is empirical research? Instead of using theories or opinions, empirical research depends on real data obtained through direct observation or experimentation.

Why Empirical Research?

Empirical research plays a key role in checking or improving current theories, providing a systematic way to grow knowledge across different areas. By focusing on objectivity, it makes research findings more trustworthy, which is critical in research fields like medicine, psychology, economics, and public policy. In the end, the strengths of empirical research lie in deepening our awareness of the world and improving our capacity to tackle problems wisely. 1,2

Qualitative and Quantitative Methods

There are two main types of empirical research methods – qualitative and quantitative. 3,4 Qualitative research delves into intricate phenomena using non-numerical data, such as interviews or observations, to offer in-depth insights into human experiences. In contrast, quantitative research analyzes numerical data to spot patterns and relationships, aiming for objectivity and the ability to apply findings to a wider context.

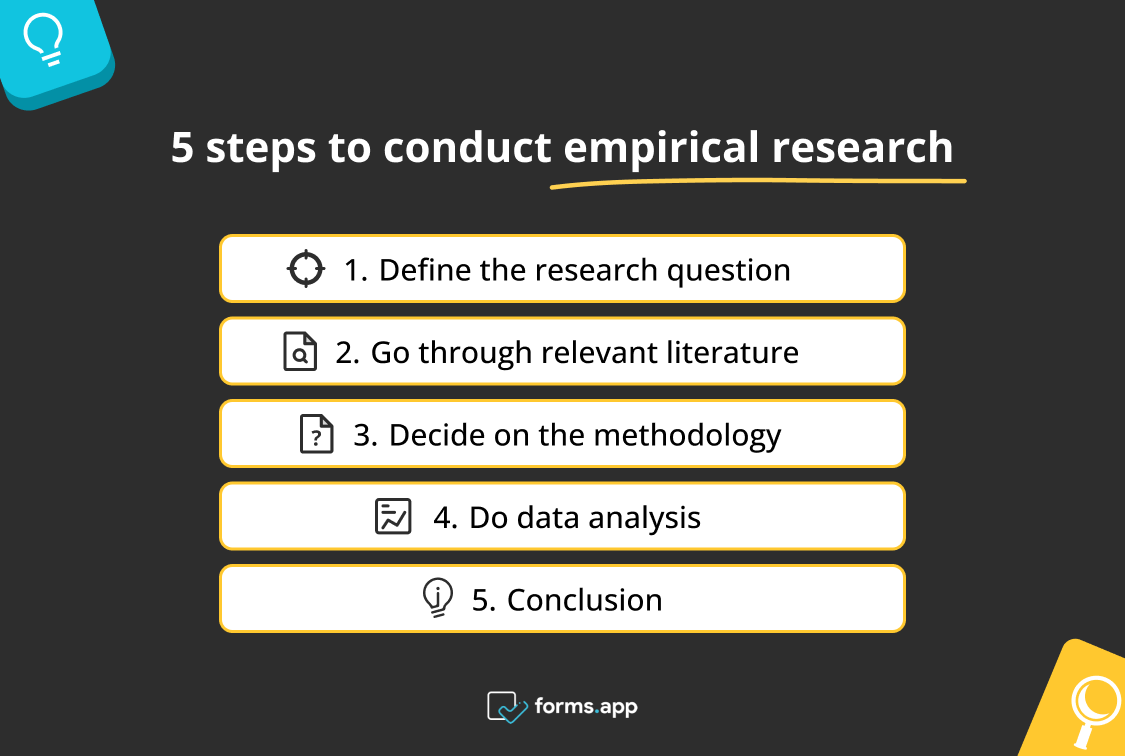

Steps for Conducting Empirical Research

When it comes to conducting research, there are some simple steps that researchers can follow. 5,6

- Create Research Hypothesis: Clearly state the specific question you want to answer or the hypothesis you want to explore in your study.

- Examine Existing Research: Read and study existing research on your topic. Understand what’s already known, identify existing gaps in knowledge, and create a framework for your own study based on what you learn.

- Plan Your Study: Decide how you’ll conduct your research—whether through qualitative methods, quantitative methods, or a mix of both. Choose suitable techniques like surveys, experiments, interviews, or observations based on your research question.

- Develop Research Instruments: Create reliable research collection tools, such as surveys or questionnaires, to help you collate data. Ensure these tools are well-designed and effective.

- Collect Data: Systematically gather the information you need for your research according to your study design and protocols using the chosen research methods.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the collected data using suitable statistical or qualitative methods that align with your research question and objectives.

- Interpret Results: Understand and explain the significance of your analysis results in the context of your research question or hypothesis.

- Draw Conclusions: Summarize your findings and draw conclusions based on the evidence. Acknowledge any study limitations and propose areas for future research.

Advantages of Empirical Research

Empirical research is valuable because it stays objective by relying on observable data, lessening the impact of personal biases. This objectivity boosts the trustworthiness of research findings. Also, using precise quantitative methods helps in accurate measurement and statistical analysis. This precision ensures researchers can draw reliable conclusions from numerical data, strengthening our understanding of the studied phenomena. 4

Disadvantages of Empirical Research

While empirical research has notable strengths, researchers must also be aware of its limitations when deciding on the right research method for their study.4 One significant drawback of empirical research is the risk of oversimplifying complex phenomena, especially when relying solely on quantitative methods. These methods may struggle to capture the richness and nuances present in certain social, cultural, or psychological contexts. Another challenge is the potential for confounding variables or biases during data collection, impacting result accuracy.

Tips for Empirical Writing

In empirical research, the writing is usually done in research papers, articles, or reports. The empirical writing follows a set structure, and each section has a specific role. Here are some tips for your empirical writing. 7

- Define Your Objectives: When you write about your research, start by making your goals clear. Explain what you want to find out or prove in a simple and direct way. This helps guide your research and lets others know what you have set out to achieve.

- Be Specific in Your Literature Review: In the part where you talk about what others have studied before you, focus on research that directly relates to your research question. Keep it short and pick studies that help explain why your research is important. This part sets the stage for your work.

- Explain Your Methods Clearly : When you talk about how you did your research (Methods), explain it in detail. Be clear about your research plan, who took part, and what you did; this helps others understand and trust your study. Also, be honest about any rules you follow to make sure your study is ethical and reproducible.

- Share Your Results Clearly : After doing your empirical research, share what you found in a simple way. Use tables or graphs to make it easier for your audience to understand your research. Also, talk about any numbers you found and clearly state if they are important or not. Ensure that others can see why your research findings matter.

- Talk About What Your Findings Mean: In the part where you discuss your research results, explain what they mean. Discuss why your findings are important and if they connect to what others have found before. Be honest about any problems with your study and suggest ideas for more research in the future.

- Wrap It Up Clearly: Finally, end your empirical research paper by summarizing what you found and why it’s important. Remind everyone why your study matters. Keep your writing clear and fix any mistakes before you share it. Ask someone you trust to read it and give you feedback before you finish.

References:

- Empirical Research in the Social Sciences and Education, Penn State University Libraries. Available online at https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/emp

- How to conduct empirical research, Emerald Publishing. Available online at https://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/how-to/research-methods/conduct-empirical-research

- Empirical Research: Quantitative & Qualitative, Arrendale Library, Piedmont University. Available online at https://library.piedmont.edu/empirical-research

- Bouchrika, I. What Is Empirical Research? Definition, Types & Samples in 2024. Research.com, January 2024. Available online at https://research.com/research/what-is-empirical-research

- Quantitative and Empirical Research vs. Other Types of Research. California State University, April 2023. Available online at https://libguides.csusb.edu/quantitative

- Empirical Research, Definitions, Methods, Types and Examples, Studocu.com website. Available online at https://www.studocu.com/row/document/uganda-christian-university/it-research-methods/emperical-research-definitions-methods-types-and-examples/55333816

- Writing an Empirical Paper in APA Style. Psychology Writing Center, University of Washington. Available online at https://psych.uw.edu/storage/writing_center/APApaper.pdf

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

- What is an Argumentative Essay? How to Write It (With Examples)

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

Ethics in Science: Importance, Principles & Guidelines

Presenting research data effectively through tables and figures, you may also like, academic integrity vs academic dishonesty: types & examples, dissertation printing and binding | types & comparison , what is a dissertation preface definition and examples , the ai revolution: authors’ role in upholding academic..., the future of academia: how ai tools are..., how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide).

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Empirical Research: Definition, Methods, Types and Examples

Content Index

Empirical research: Definition

Empirical research: origin, quantitative research methods, qualitative research methods, steps for conducting empirical research, empirical research methodology cycle, advantages of empirical research, disadvantages of empirical research, why is there a need for empirical research.

Empirical research is defined as any research where conclusions of the study is strictly drawn from concretely empirical evidence, and therefore “verifiable” evidence.

This empirical evidence can be gathered using quantitative market research and qualitative market research methods.

For example: A research is being conducted to find out if listening to happy music in the workplace while working may promote creativity? An experiment is conducted by using a music website survey on a set of audience who are exposed to happy music and another set who are not listening to music at all, and the subjects are then observed. The results derived from such a research will give empirical evidence if it does promote creativity or not.

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Research

You must have heard the quote” I will not believe it unless I see it”. This came from the ancient empiricists, a fundamental understanding that powered the emergence of medieval science during the renaissance period and laid the foundation of modern science, as we know it today. The word itself has its roots in greek. It is derived from the greek word empeirikos which means “experienced”.

In today’s world, the word empirical refers to collection of data using evidence that is collected through observation or experience or by using calibrated scientific instruments. All of the above origins have one thing in common which is dependence of observation and experiments to collect data and test them to come up with conclusions.

LEARN ABOUT: Causal Research

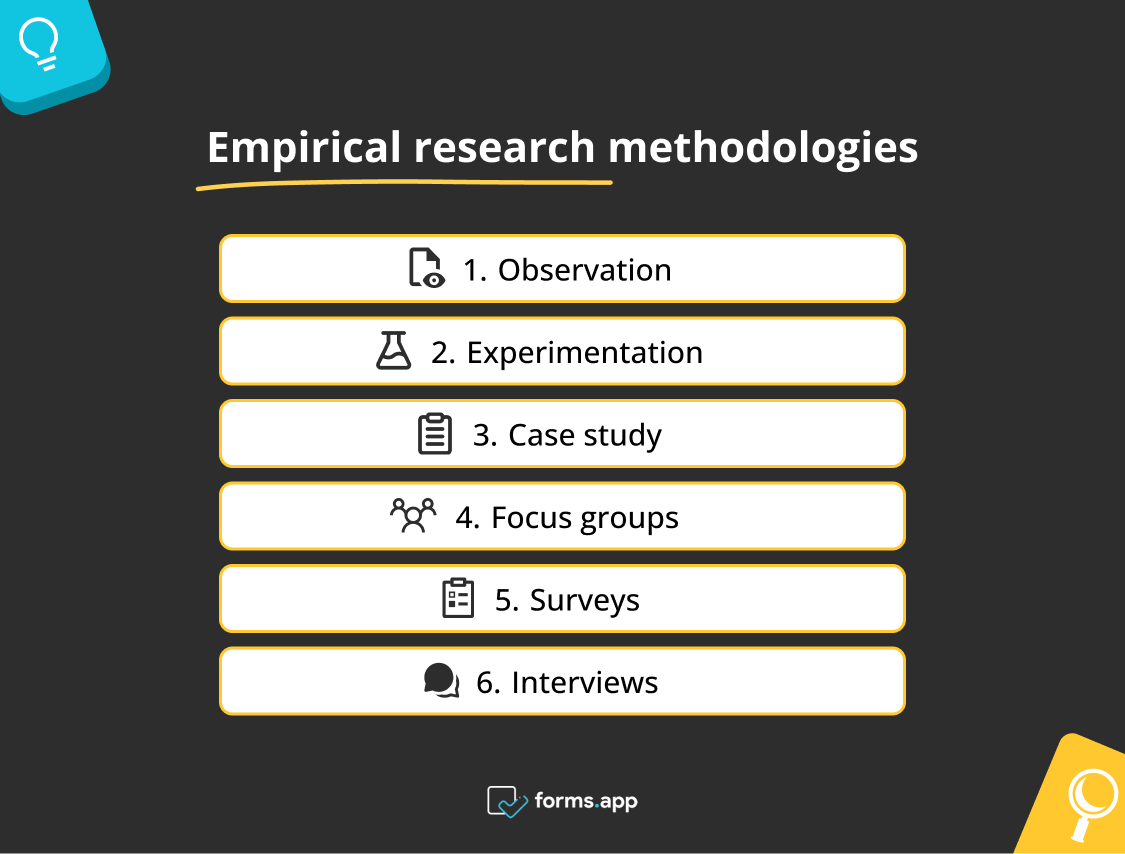

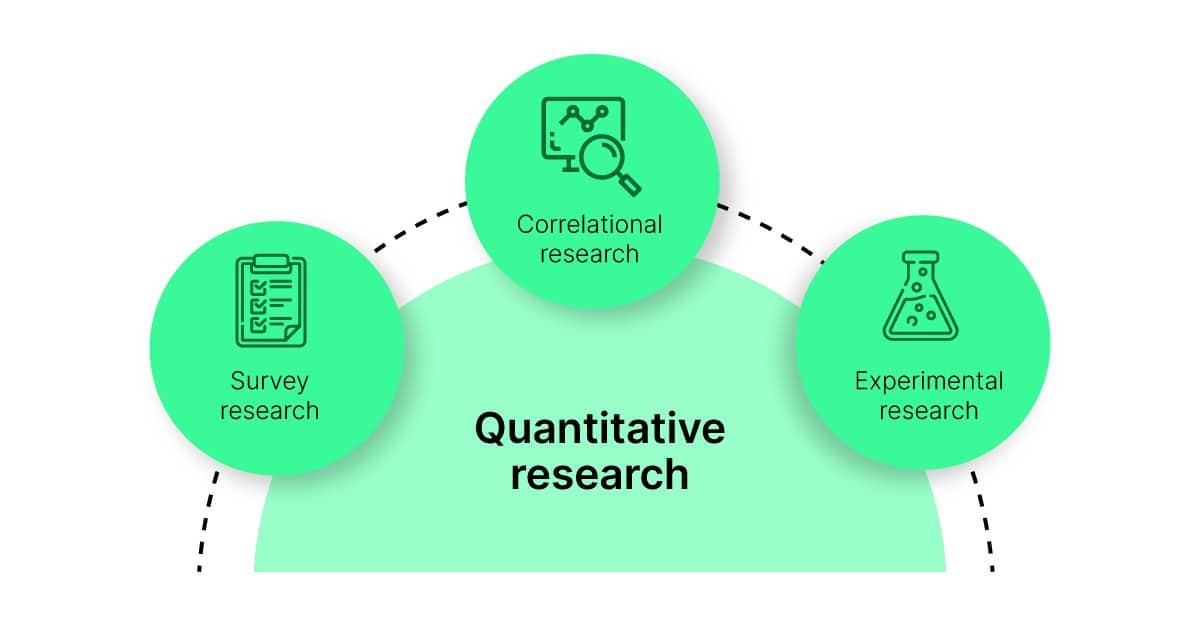

Types and methodologies of empirical research

Empirical research can be conducted and analysed using qualitative or quantitative methods.

- Quantitative research : Quantitative research methods are used to gather information through numerical data. It is used to quantify opinions, behaviors or other defined variables . These are predetermined and are in a more structured format. Some of the commonly used methods are survey, longitudinal studies, polls, etc

- Qualitative research: Qualitative research methods are used to gather non numerical data. It is used to find meanings, opinions, or the underlying reasons from its subjects. These methods are unstructured or semi structured. The sample size for such a research is usually small and it is a conversational type of method to provide more insight or in-depth information about the problem Some of the most popular forms of methods are focus groups, experiments, interviews, etc.

Data collected from these will need to be analysed. Empirical evidence can also be analysed either quantitatively and qualitatively. Using this, the researcher can answer empirical questions which have to be clearly defined and answerable with the findings he has got. The type of research design used will vary depending on the field in which it is going to be used. Many of them might choose to do a collective research involving quantitative and qualitative method to better answer questions which cannot be studied in a laboratory setting.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Research Questions and Questionnaires

Quantitative research methods aid in analyzing the empirical evidence gathered. By using these a researcher can find out if his hypothesis is supported or not.

- Survey research: Survey research generally involves a large audience to collect a large amount of data. This is a quantitative method having a predetermined set of closed questions which are pretty easy to answer. Because of the simplicity of such a method, high responses are achieved. It is one of the most commonly used methods for all kinds of research in today’s world.

Previously, surveys were taken face to face only with maybe a recorder. However, with advancement in technology and for ease, new mediums such as emails , or social media have emerged.

For example: Depletion of energy resources is a growing concern and hence there is a need for awareness about renewable energy. According to recent studies, fossil fuels still account for around 80% of energy consumption in the United States. Even though there is a rise in the use of green energy every year, there are certain parameters because of which the general population is still not opting for green energy. In order to understand why, a survey can be conducted to gather opinions of the general population about green energy and the factors that influence their choice of switching to renewable energy. Such a survey can help institutions or governing bodies to promote appropriate awareness and incentive schemes to push the use of greener energy.

Learn more: Renewable Energy Survey Template Descriptive Research vs Correlational Research

- Experimental research: In experimental research , an experiment is set up and a hypothesis is tested by creating a situation in which one of the variable is manipulated. This is also used to check cause and effect. It is tested to see what happens to the independent variable if the other one is removed or altered. The process for such a method is usually proposing a hypothesis, experimenting on it, analyzing the findings and reporting the findings to understand if it supports the theory or not.

For example: A particular product company is trying to find what is the reason for them to not be able to capture the market. So the organisation makes changes in each one of the processes like manufacturing, marketing, sales and operations. Through the experiment they understand that sales training directly impacts the market coverage for their product. If the person is trained well, then the product will have better coverage.

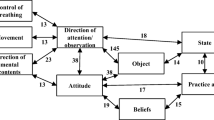

- Correlational research: Correlational research is used to find relation between two set of variables . Regression analysis is generally used to predict outcomes of such a method. It can be positive, negative or neutral correlation.

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

For example: Higher educated individuals will get higher paying jobs. This means higher education enables the individual to high paying job and less education will lead to lower paying jobs.

- Longitudinal study: Longitudinal study is used to understand the traits or behavior of a subject under observation after repeatedly testing the subject over a period of time. Data collected from such a method can be qualitative or quantitative in nature.

For example: A research to find out benefits of exercise. The target is asked to exercise everyday for a particular period of time and the results show higher endurance, stamina, and muscle growth. This supports the fact that exercise benefits an individual body.

- Cross sectional: Cross sectional study is an observational type of method, in which a set of audience is observed at a given point in time. In this type, the set of people are chosen in a fashion which depicts similarity in all the variables except the one which is being researched. This type does not enable the researcher to establish a cause and effect relationship as it is not observed for a continuous time period. It is majorly used by healthcare sector or the retail industry.

For example: A medical study to find the prevalence of under-nutrition disorders in kids of a given population. This will involve looking at a wide range of parameters like age, ethnicity, location, incomes and social backgrounds. If a significant number of kids coming from poor families show under-nutrition disorders, the researcher can further investigate into it. Usually a cross sectional study is followed by a longitudinal study to find out the exact reason.

- Causal-Comparative research : This method is based on comparison. It is mainly used to find out cause-effect relationship between two variables or even multiple variables.

For example: A researcher measured the productivity of employees in a company which gave breaks to the employees during work and compared that to the employees of the company which did not give breaks at all.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

Some research questions need to be analysed qualitatively, as quantitative methods are not applicable there. In many cases, in-depth information is needed or a researcher may need to observe a target audience behavior, hence the results needed are in a descriptive analysis form. Qualitative research results will be descriptive rather than predictive. It enables the researcher to build or support theories for future potential quantitative research. In such a situation qualitative research methods are used to derive a conclusion to support the theory or hypothesis being studied.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Interview

- Case study: Case study method is used to find more information through carefully analyzing existing cases. It is very often used for business research or to gather empirical evidence for investigation purpose. It is a method to investigate a problem within its real life context through existing cases. The researcher has to carefully analyse making sure the parameter and variables in the existing case are the same as to the case that is being investigated. Using the findings from the case study, conclusions can be drawn regarding the topic that is being studied.

For example: A report mentioning the solution provided by a company to its client. The challenges they faced during initiation and deployment, the findings of the case and solutions they offered for the problems. Such case studies are used by most companies as it forms an empirical evidence for the company to promote in order to get more business.

- Observational method: Observational method is a process to observe and gather data from its target. Since it is a qualitative method it is time consuming and very personal. It can be said that observational research method is a part of ethnographic research which is also used to gather empirical evidence. This is usually a qualitative form of research, however in some cases it can be quantitative as well depending on what is being studied.

For example: setting up a research to observe a particular animal in the rain-forests of amazon. Such a research usually take a lot of time as observation has to be done for a set amount of time to study patterns or behavior of the subject. Another example used widely nowadays is to observe people shopping in a mall to figure out buying behavior of consumers.

- One-on-one interview: Such a method is purely qualitative and one of the most widely used. The reason being it enables a researcher get precise meaningful data if the right questions are asked. It is a conversational method where in-depth data can be gathered depending on where the conversation leads.

For example: A one-on-one interview with the finance minister to gather data on financial policies of the country and its implications on the public.

- Focus groups: Focus groups are used when a researcher wants to find answers to why, what and how questions. A small group is generally chosen for such a method and it is not necessary to interact with the group in person. A moderator is generally needed in case the group is being addressed in person. This is widely used by product companies to collect data about their brands and the product.

For example: A mobile phone manufacturer wanting to have a feedback on the dimensions of one of their models which is yet to be launched. Such studies help the company meet the demand of the customer and position their model appropriately in the market.

- Text analysis: Text analysis method is a little new compared to the other types. Such a method is used to analyse social life by going through images or words used by the individual. In today’s world, with social media playing a major part of everyone’s life, such a method enables the research to follow the pattern that relates to his study.

For example: A lot of companies ask for feedback from the customer in detail mentioning how satisfied are they with their customer support team. Such data enables the researcher to take appropriate decisions to make their support team better.

Sometimes a combination of the methods is also needed for some questions that cannot be answered using only one type of method especially when a researcher needs to gain a complete understanding of complex subject matter.

We recently published a blog that talks about examples of qualitative data in education ; why don’t you check it out for more ideas?

Learn More: Data Collection Methods: Types & Examples

Since empirical research is based on observation and capturing experiences, it is important to plan the steps to conduct the experiment and how to analyse it. This will enable the researcher to resolve problems or obstacles which can occur during the experiment.

Step #1: Define the purpose of the research

This is the step where the researcher has to answer questions like what exactly do I want to find out? What is the problem statement? Are there any issues in terms of the availability of knowledge, data, time or resources. Will this research be more beneficial than what it will cost.

Before going ahead, a researcher has to clearly define his purpose for the research and set up a plan to carry out further tasks.

Step #2 : Supporting theories and relevant literature

The researcher needs to find out if there are theories which can be linked to his research problem . He has to figure out if any theory can help him support his findings. All kind of relevant literature will help the researcher to find if there are others who have researched this before, or what are the problems faced during this research. The researcher will also have to set up assumptions and also find out if there is any history regarding his research problem

Step #3: Creation of Hypothesis and measurement

Before beginning the actual research he needs to provide himself a working hypothesis or guess what will be the probable result. Researcher has to set up variables, decide the environment for the research and find out how can he relate between the variables.

Researcher will also need to define the units of measurements, tolerable degree for errors, and find out if the measurement chosen will be acceptable by others.

Step #4: Methodology, research design and data collection

In this step, the researcher has to define a strategy for conducting his research. He has to set up experiments to collect data which will enable him to propose the hypothesis. The researcher will decide whether he will need experimental or non experimental method for conducting the research. The type of research design will vary depending on the field in which the research is being conducted. Last but not the least, the researcher will have to find out parameters that will affect the validity of the research design. Data collection will need to be done by choosing appropriate samples depending on the research question. To carry out the research, he can use one of the many sampling techniques. Once data collection is complete, researcher will have empirical data which needs to be analysed.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

Step #5: Data Analysis and result

Data analysis can be done in two ways, qualitatively and quantitatively. Researcher will need to find out what qualitative method or quantitative method will be needed or will he need a combination of both. Depending on the unit of analysis of his data, he will know if his hypothesis is supported or rejected. Analyzing this data is the most important part to support his hypothesis.

Step #6: Conclusion

A report will need to be made with the findings of the research. The researcher can give the theories and literature that support his research. He can make suggestions or recommendations for further research on his topic.

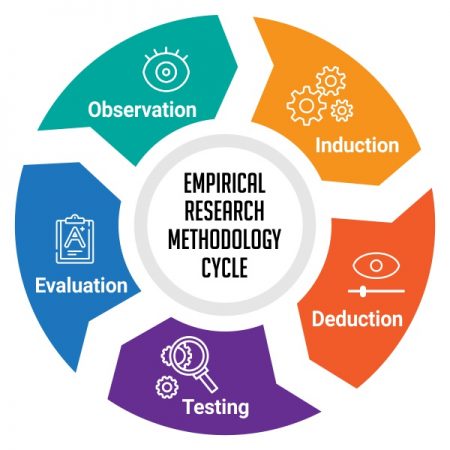

A.D. de Groot, a famous dutch psychologist and a chess expert conducted some of the most notable experiments using chess in the 1940’s. During his study, he came up with a cycle which is consistent and now widely used to conduct empirical research. It consists of 5 phases with each phase being as important as the next one. The empirical cycle captures the process of coming up with hypothesis about how certain subjects work or behave and then testing these hypothesis against empirical data in a systematic and rigorous approach. It can be said that it characterizes the deductive approach to science. Following is the empirical cycle.

- Observation: At this phase an idea is sparked for proposing a hypothesis. During this phase empirical data is gathered using observation. For example: a particular species of flower bloom in a different color only during a specific season.

- Induction: Inductive reasoning is then carried out to form a general conclusion from the data gathered through observation. For example: As stated above it is observed that the species of flower blooms in a different color during a specific season. A researcher may ask a question “does the temperature in the season cause the color change in the flower?” He can assume that is the case, however it is a mere conjecture and hence an experiment needs to be set up to support this hypothesis. So he tags a few set of flowers kept at a different temperature and observes if they still change the color?

- Deduction: This phase helps the researcher to deduce a conclusion out of his experiment. This has to be based on logic and rationality to come up with specific unbiased results.For example: In the experiment, if the tagged flowers in a different temperature environment do not change the color then it can be concluded that temperature plays a role in changing the color of the bloom.

- Testing: This phase involves the researcher to return to empirical methods to put his hypothesis to the test. The researcher now needs to make sense of his data and hence needs to use statistical analysis plans to determine the temperature and bloom color relationship. If the researcher finds out that most flowers bloom a different color when exposed to the certain temperature and the others do not when the temperature is different, he has found support to his hypothesis. Please note this not proof but just a support to his hypothesis.

- Evaluation: This phase is generally forgotten by most but is an important one to keep gaining knowledge. During this phase the researcher puts forth the data he has collected, the support argument and his conclusion. The researcher also states the limitations for the experiment and his hypothesis and suggests tips for others to pick it up and continue a more in-depth research for others in the future. LEARN MORE: Population vs Sample

LEARN MORE: Population vs Sample

There is a reason why empirical research is one of the most widely used method. There are a few advantages associated with it. Following are a few of them.

- It is used to authenticate traditional research through various experiments and observations.

- This research methodology makes the research being conducted more competent and authentic.

- It enables a researcher understand the dynamic changes that can happen and change his strategy accordingly.

- The level of control in such a research is high so the researcher can control multiple variables.

- It plays a vital role in increasing internal validity .

Even though empirical research makes the research more competent and authentic, it does have a few disadvantages. Following are a few of them.

- Such a research needs patience as it can be very time consuming. The researcher has to collect data from multiple sources and the parameters involved are quite a few, which will lead to a time consuming research.

- Most of the time, a researcher will need to conduct research at different locations or in different environments, this can lead to an expensive affair.

- There are a few rules in which experiments can be performed and hence permissions are needed. Many a times, it is very difficult to get certain permissions to carry out different methods of this research.

- Collection of data can be a problem sometimes, as it has to be collected from a variety of sources through different methods.

LEARN ABOUT: Social Communication Questionnaire

Empirical research is important in today’s world because most people believe in something only that they can see, hear or experience. It is used to validate multiple hypothesis and increase human knowledge and continue doing it to keep advancing in various fields.

For example: Pharmaceutical companies use empirical research to try out a specific drug on controlled groups or random groups to study the effect and cause. This way, they prove certain theories they had proposed for the specific drug. Such research is very important as sometimes it can lead to finding a cure for a disease that has existed for many years. It is useful in science and many other fields like history, social sciences, business, etc.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

With the advancement in today’s world, empirical research has become critical and a norm in many fields to support their hypothesis and gain more knowledge. The methods mentioned above are very useful for carrying out such research. However, a number of new methods will keep coming up as the nature of new investigative questions keeps getting unique or changing.

Create a single source of real data with a built-for-insights platform. Store past data, add nuggets of insights, and import research data from various sources into a CRM for insights. Build on ever-growing research with a real-time dashboard in a unified research management platform to turn insights into knowledge.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Participant Engagement: Strategies + Improving Interaction

Sep 12, 2024

Employee Recognition Programs: A Complete Guide

Sep 11, 2024

A guide to conducting agile qualitative research for rapid insights with Digsite

Cultural Insights: What it is, Importance + How to Collect?

Sep 10, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

What is Empirical Research? Definition, Types, and More

Navigate data's complexities with empirical research, distinguishing truth from speculation. Explore types, methods, and more.

Godi Yeshaswi

January 12, 2024

In this Article

Research is crucial in many fields, involving a systematic exploration to confirm facts or draw specific conclusions. Empirical research, widely applied in different areas, aims to validate new facts. Grasping the significance of empirical research and knowing how to carry it out can aid in making decisions backed by a thorough investigation.

What Do You Mean by Empirical Research?

The empirical research method is a study based on observation and direct experience to understand phenomena and draw conclusions based on real-world observations.

Empirical Research Examples

Consider a scenario where a study aims to determine if people add a product to their online cart due to product ratings. To investigate this, an experiment is carried out using an online shopping attitude survey . One group of participants is exposed to ratings, while another group is not exposed to any product ratings. The researchers then observe the behavior of these groups. The findings from this research will provide concrete evidence on whether product ratings impact the decision to purchase.

Types of Methodologies for Empirical Research

Quantitative research.

Quantitative research collects numerical data to analyze specific behaviors, opinions, or defined variables . Here are some methods used in quantitative empirical research:

This calls for collecting information from a group of people using a questionnaire. When conducting surveys, it's essential to pose straightforward, brief, and easy questions for participants to respond to. Survey participants can provide their answers through various channels, whether it be on paper, online through emails, or on social media. Administering surveys is generally a straightforward approach to obtaining information, whether from the general public or a specific audience.

Experimental Research

This process includes forming an idea and checking it through experimentation. Researchers can change one variable and see how it impacts other variables, helping them figure out if there's a clear connection. They can then examine the findings to confirm if their initial idea is correct.

Longitudinal Study

A longitudinal study involves observing a subject's characteristics or actions by testing them repeatedly over a period. The data collected from this method can be either qualitative or quantitative. For instance, marketers could track the buying patterns of a particular demographic, such as young adults, over several years. By repeatedly collecting data on their product design preferences, brand loyalty, and spending habits, researchers can gain insights into how these factors evolve over time.

Cross-Sectional Research

Cross-sectional research is a way of studying people by looking at them during a particular time. In this method, researchers pick a group of individuals with similar characteristics, excluding the ones they are studying. This helps ensure that any findings are likely caused by the variable under investigation. For instance, researchers assess consumer preferences for different packaging designs at a specific time. Participants from the target market evaluate various options, providing immediate feedback. This approach offers a quick snapshot of consumer opinions on packaging, helping companies make informed decisions based on current preferences.

Correlational Research

Correlational research is a method used to find connections and prevalence among different factors. It often uses regression as a statistical tool to predict outcomes, showing whether there's a negative, neutral, or positive correlation between variables. For example, researchers might explore the relationship between how much time individuals spend watching television and their overall well-being. By collecting data on both variables from a diverse group of participants, the researchers can analyze whether there is a correlation between the time spent watching TV and factors like happiness or stress levels.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is useful for collecting information that isn't in numbers or can't be measured easily. It usually involves semi-structured or unstructured approaches, letting researchers uncover personal meanings, reasons, and opinions from participants. Qualitative empirical research often involves a small group of people and conversational methods to get detailed information and deeper insights into a problem. Examples of methods used in qualitative research include:

Observational Method

It involves watching and collecting descriptive information about a subject. The observational method gives researchers personal insights, helping them form detailed opinions about their studies. It's commonly used in ethnographic research, which looks at the culture of different groups of people.

One-on-One Interview

This is an entirely qualitative method that includes directly talking to a subject. Researchers often use it to get accurate and meaningful information about a subject. It's a conversational approach where specific questions are asked to guide the discussion.

Focus Group

Focus groups are employed when researchers seek answers to questions of why, what, and how. A small group is typically chosen, and in-person interaction may not be necessary. If an in-person discussion is involved, a moderator is usually required. This method is commonly utilized by product companies to gather information about their brands and products.

For instance, in media/ad testing with focus groups, a company may evaluate a new soft drink advertisement. A small group views different ad versions and discusses their impressions, preferences, and memorable elements. This feedback helps the company refine its advertising strategy before a wider campaign launch.

Text Analysis

This qualitative empirical research method enables the analysis of an individual's social life . It's a contemporary approach leveraging the growing importance of social media and technology. Researchers can examine the specific words and images an individual uses to draw meaningful conclusions.

How to Conduct Empirical Research?

Empirical research relies on observation and experiences, so planning and analysis are crucial. Let’s take an example of media/ad/shopper testing as the research base to understand the steps to conduct empirical research -

Step 1: Define the Research Objective

Clearly outline the study's goal, such as evaluating the effectiveness of a new packaging design for a consumer product or an advertisement of a new series. Consider potential issues with the resources schedule and ensure the study's benefits justify the costs.

Step 2: Review Relevant Literature and Theories

Identify theories or previous studies on consumer responses to packaging changes or new series ad releases. Understand how these insights can inform the study's outcomes.

Step 3: Formulate Hypothesis and Measurements

Develop an initial hypothesis, considering variables like consumer perception, brand appeal, and market competitiveness. Define units of measurement, such as consumer preferences and purchasing behavior, ensuring they align with industry standards.

Step 4: Define Research Design, Methodology, and Data Collection Techniques

Choose an appropriate research approach, whether qualitative research or quantitative research , to assess consumer reactions to the new packaging. Consider using focus groups and one-on-one interviews for in-depth insights and gather data on consumer reactions.

Step #5: Conduct Data Analysis and Frame the Results

Analyze the collected data, considering both quantitative metrics and qualitative feedback from focus groups and interviews. Assess whether the new packaging positively influences consumer perceptions and purchasing decisions.

Evaluate consumer research tools powered by Insights AI that are powered by AI to give you unbiased feedback considering the emotions and behaviour of the respondent.

Step 6: Draw Conclusions

Prepare a comprehensive report presenting the findings, including the impact of the new packaging or advertisement on consumer behavior. If sharing the results widely, convert the report into an article for publication and recommend further research areas in the packaging and media testing domain. Use a plagiarism checker to ensure the originality and credibility of the research.

You can also utilize the Gen AI feature in Decode to draw conclusions from your studies by just asking the Decode co-pilot, a virtual assistant.

{{cta-button}}

Empirical Research Cycle

Observation

A media researcher observes audience reactions to a new television show by monitoring social media comments, ratings, and viewership numbers. This initial data collection serves as the basis for forming hypotheses about the show's popularity.

Based on the observations, the researcher may induce a hypothesis that suggests the show's popularity is linked to its engaging storyline and relatable characters. This assumption is then examined and tested against the collected data.

Using deductive reasoning, the researcher concludes that if the show's popularity is consistently associated with positive audience engagement and high ratings, it can be inferred that engaging content is a significant factor.

To test the hypothesis, the researcher designs a survey asking viewers about their reasons for liking the show and analyzes the responses. Statistical methods are employed to determine if there's a significant correlation between positive viewer feedback and the show's popularity.

In the final stage, the researcher evaluates the survey results, considering the empirical data, viewer comments, and any challenges encountered during the research. The findings are used to draw conclusions about the factors contributing to the show's success, and this information becomes the basis for further media testing or content development.

{{cta-case}}

Advantages and Disadvantages of Empirical Research

Advantages of empirical research.

Empirical research is widely used for several reasons, and here are some of its advantages:

- Authentication of Traditional Research: It validates traditional research through experiments and observations.

- Enhanced Competence and Authenticity: This methodology enhances the competency and authenticity of the conducted research.

- Adaptability to Dynamic Changes: Researchers can understand and adapt to dynamic changes by utilizing empirical research and adjusting their strategies accordingly.

- High Control Level: Empirical research offers a high level of control, allowing researchers to manage multiple variables.

- Increased Internal Validity: It plays a crucial role in boosting internal validity, ensuring the accuracy of the research outcomes.

Disadvantages of Empirical Research

While empirical research brings competency and authenticity, it also has some drawbacks:

- Time-Consuming Nature: Collecting data from various sources and dealing with numerous parameters can make this research time-consuming requiring patience.

- Costly Endeavor: Conducting research in different locations or environments may lead to increased expenses.

- Permission Challenges: Obtaining consent for certain experimental methods can be difficult, as there are strict rules governing their execution.

- Data Collection Challenges: Collecting data from various sources through different methods can be problematic at times.

Bottom Line

In a world full of data, empirical research is crucial for finding out what's true. It involves carefully observing and experiencing things to draw conclusions based on real-world evidence. This type of research uses both numbers (quantitative) and descriptions (qualitative) to understand various topics.

To conduct empirical research, you need a step-by-step plan. This includes setting clear goals, looking at existing research, making educated guesses (hypotheses), picking the right methods, analyzing data, and reaching sensible conclusions.

The research cycle involves watching, making guesses, drawing logical conclusions, testing those guesses, and finally evaluating everything.

While empirical research has benefits like proving traditional research, increasing competence, and adapting to changes, it also has challenges like being time-consuming, expensive, and dealing with permission and data collection issues.

In summary, understanding and using empirical research helps us make informed decisions in different fields by carefully studying and validating information through a systematic process.

Frequently Asked Questions

What do you mean by empirical research.

Empirical research is a type of study that relies on observing and measuring real-life phenomena as directly witnessed by the researcher. The collected data can be analyzed in relation to a theory or hypothesis, but the conclusions are grounded in actual experiences.

Theoretical vs Empirical Research

Empirical refers to information derived from observations or personal experiences, while theoretical is associated with ideas and hypotheses. In research contexts, these terms are commonly used to describe data, methods, or probabilities.

What are the benefits of Empirical Research?

Empirical research strives to understand the significance of a specific phenomenon. In simpler terms, it seeks to uncover how and why something operates the way it does. By pinpointing the reasons behind occurrences, it becomes feasible to reproduce or avoid similar events.

Is Empirical quantitative or qualitative?

Empirical research is often thought of as the same as quantitative research, but to be precise, it's any research that relies on direct observation.

Empirical Method Psychology Example

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Suspendisse varius enim in eros elementum tristique. Duis cursus, mi quis viverra ornare, eros dolor interdum nulla, ut commodo diam libero vitae erat. Aenean faucibus nibh et justo cursus id rutrum lorem imperdiet. Nunc ut sem vitae risus tristique posuere.

With lots of unique blocks, you can easily build a page without coding.

Click on Study templates

Start from scratch

Add blocks to the content

Saving the Template

Publish the Template

Suppose a researcher aims to investigate the impact of listening to happy music on promoting prosocial behavior. In this scenario, an empirical analysis could involve conducting an experiment where one group of participants is exposed to happy music while another group is not exposed to any music at all.

Yeshaswi is a dedicated and enthusiastic individual with a strong affinity for tech and all things content. When he's not at work, he channels his passion into his love for football, especially for F.C. Barcelona and the GOAT, Lionel Messi. Instead of hitting the town for parties, he prefers to spend quality time cuddling with his Golden Retriever, Oreo.

Product Marketing Specialist

Related Articles

Top AI Events You Do Not Want to Miss in 2024

Here are all the top AI events for 2024, curated in one convenient place just for you.

Top Insights Events You Do Not Want to Miss in 2024

Here are all the top Insights events for 2024, curated in one convenient place just for you.

Top CX Events You Do Not Want to Miss in 2024

Here are all the top CX events for 2024, curated in one convenient place just for you.

How to Build an Experience Map: A Complete Guide

An experience map is essential for businesses, as it highlights the customer journey, uncovering insights to improve user experiences and address pain points. Read to find more!

Everything You Need to Know about Intelligent Scoring

Are you curious about Intelligent Scoring and how it differs from regular scoring? Discover its applications and benefits. Read on to learn more!

Qualitative Research Methods and Its Advantages In Modern User Research

Discover how to leverage qualitative research methods, including moderated sessions, to gain deep user insights and enhance your product and UX decisions.

The 10 Best Customer Experience Platforms to Transform Your CX

Explore the top 10 CX platforms to revolutionize customer interactions, enhance satisfaction, and drive business growth.

TAM SAM SOM: What It Means and How to Calculate It?

Understanding TAM, SAM, SOM helps businesses gauge market potential. Learn their definitions and how to calculate them for better business decisions and strategy.

Understanding Likert Scales: Advantages, Limitations, and Questions

Using Likert scales can help you understand how your customers view and rate your product. Here's how you can use them to get the feedback you need.

Mastering the 80/20 Rule to Transform User Research

Find out how the Pareto Principle can optimize your user research processes and lead to more impactful results with the help of AI.

Understanding Consumer Psychology: The Science Behind What Makes Us Buy

Gain a comprehensive understanding of consumer psychology and learn how to apply these insights to inform your research and strategies.

A Guide to Website Footers: Best Design Practices & Examples

Explore the importance of website footers, design best practices, and how to optimize them using UX research for enhanced user engagement and navigation.

Customer Effort Score: Definition, Examples, Tips

A great customer score can lead to dedicated, engaged customers who can end up being loyal advocates of your brand. Here's what you need to know about it.

How to Detect and Address User Pain Points for Better Engagement

Understanding user pain points can help you provide a seamless user experiences that makes your users come back for more. Here's what you need to know about it.

What is Quota Sampling? Definition, Types, Examples, and How to Use It?

Discover Quota Sampling: Learn its process, types, and benefits for accurate consumer insights and informed marketing decisions. Perfect for researchers and brand marketers!

What Is Accessibility Testing? A Comprehensive Guide

Ensure inclusivity and compliance with accessibility standards through thorough testing. Improve user experience and mitigate legal risks. Learn more.

Maximizing Your Research Efficiency with AI Transcriptions

Explore how AI transcription can transform your market research by delivering precise and rapid insights from audio and video recordings.

Understanding the False Consensus Effect: How to Manage it

The false consensus effect can cause incorrect assumptions and ultimately, the wrong conclusions. Here's how you can overcome it.

5 Banking Customer Experience Trends to Watch Out for in 2024

Discover the top 5 banking customer experience trends to watch out for in 2024. Stay ahead in the evolving financial landscape.

The Ultimate Guide to Regression Analysis: Definition, Types, Usage & Advantages

Master Regression Analysis: Learn types, uses & benefits in consumer research for precise insights & strategic decisions.

EyeQuant Alternative

Meet Qatalyst, your best eyequant alternative to improve user experience and an AI-powered solution for all your user research needs.

EyeSee Alternative

Embrace the Insights AI revolution: Meet Decode, your innovative solution for consumer insights, offering a compelling alternative to EyeSee.

Skeuomorphism in UX Design: Is It Dead?

Skeuomorphism in UX design creates intuitive interfaces using familiar real-world visuals to help users easily understand digital products. Do you know how?

Top 6 Wireframe Tools and Ways to Test Your Designs

Wireframe tools assist designers in planning and visualizing the layout of their websites. Look through this list of wireframing tools to find the one that suits you best.

Revolutionizing Customer Interaction: The Power of Conversational AI

Conversational AI enhances customer service across various industries, offering intelligent, context-aware interactions that drive efficiency and satisfaction. Here's how.

User Story Mapping: A Powerful Tool for User-Centered Product Development

Learn about user story mapping and how it can be used for successful product development with this blog.

What is Research Hypothesis: Definition, Types, and How to Develop

Read the blog to learn how a research hypothesis provides a clear and focused direction for a study and helps formulate research questions.

Understanding Customer Retention: How to Keep Your Customers Coming Back

Understanding customer retention is key to building a successful brand that has repeat, loyal customers. Here's what you need to know about it.

Demographic Segmentation: How Brands Can Use it to Improve Marketing Strategies

Read this blog to learn what demographic segmentation means, its importance, and how it can be used by brands.

Mastering Product Positioning: A UX Researcher's Guide

Read this blog to understand why brands should have a well-defined product positioning and how it affects the overall business.

Discrete Vs. Continuous Data: Everything You Need To Know

Explore the differences between discrete and continuous data and their impact on business decisions and customer insights.

50+ Employee Engagement Survey Questions

Understand how an employee engagement survey provides insights into employee satisfaction and motivation, directly impacting productivity and retention.

What is Experimental Research: Definition, Types & Examples

Understand how experimental research enables researchers to confidently identify causal relationships between variables and validate findings, enhancing credibility.

A Guide to Interaction Design

Interaction design can help you create engaging and intuitive user experiences, improving usability and satisfaction through effective design principles. Here's how.

Exploring the Benefits of Stratified Sampling

Understanding stratified sampling can improve research accuracy by ensuring diverse representation across key subgroups. Here's how.

A Guide to Voice Recognition in Enhancing UX Research

Learn the importance of using voice recognition technology in user research for enhanced user feedback and insights.

The Ultimate Figma Design Handbook: Design Creation and Testing

The Ultimate Figma Design Handbook covers setting up Figma, creating designs, advanced features, prototyping, and testing designs with real users.

The Power of Organization: Mastering Information Architectures

Understanding the art of information architectures can enhance user experiences by organizing and structuring digital content effectively, making information easy to find and navigate. Here's how.

Convenience Sampling: Examples, Benefits, and When To Use It

Read the blog to understand how convenience sampling allows for quick and easy data collection with minimal cost and effort.

What is Critical Thinking, and How Can it be Used in Consumer Research?

Learn how critical thinking enhances consumer research and discover how Decode's AI-driven platform revolutionizes data analysis and insights.

How Business Intelligence Tools Transform User Research & Product Management

This blog explains how Business Intelligence (BI) tools can transform user research and product management by providing data-driven insights for better decision-making.

What is Face Validity? Definition, Guide and Examples

Read this blog to explore face validity, its importance, and the advantages of using it in market research.

What is Customer Lifetime Value, and How To Calculate It?

Read this blog to understand how Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) can help your business optimize marketing efforts, improve customer retention, and increase profitability.

Systematic Sampling: Definition, Examples, and Types

Explore how systematic sampling helps researchers by providing a structured method to select representative samples from larger populations, ensuring efficiency and reducing bias.

Understanding Selection Bias: A Guide

Selection bias can affect the type of respondents you choose for the study and ultimately the quality of responses you receive. Here’s all you need to know about it.

A Guide to Designing an Effective Product Strategy

Read this blog to explore why a well-defined product strategy is required for brands while developing or refining a product.

A Guide to Minimum Viable Product (MVP) in UX: Definition, Strategies, and Examples

Discover what an MVP is, why it's crucial in UX, strategies for creating one, and real-world examples from top companies like Dropbox and Airbnb.

Asking Close Ended Questions: A Guide

Asking the right close ended questions is they key to getting quantitiative data from your users. Her's how you should do it.

Creating Website Mockups: Your Ultimate Guide to Effective Design

Read this blog to learn website mockups- tools, examples and how to create an impactful website design.

Understanding Your Target Market And Its Importance In Consumer Research

Read this blog to learn about the importance of creating products and services to suit the needs of your target audience.

What Is a Go-To-Market Strategy And How to Create One?

Check out this blog to learn how a go-to-market strategy helps businesses enter markets smoothly, attract more customers, and stand out from competitors.

What is Confirmation Bias in Consumer Research?

Learn how confirmation bias affects consumer research, its types, impacts, and practical tips to avoid it for more accurate and reliable insights.

Market Penetration: The Key to Business Success

Understanding market penetration is key to cracking the code to sustained business growth and competitive advantage in any industry. Here's all you need to know about it.

How to Create an Effective User Interface

Having a simple, clear user interface helps your users find what they really want, improving the user experience. Here's how you can achieve it.

Product Differentiation and What It Means for Your Business

Discover how product differentiation helps businesses stand out with unique features, innovative designs, and exceptional customer experiences.

What is Ethnographic Research? Definition, Types & Examples

Read this blog to understand Ethnographic research, its relevance in today’s business landscape and how you can leverage it for your business.

Product Roadmap: The 2024 Guide [with Examples]

Read this blog to understand how a product roadmap can align stakeholders by providing a clear product development and delivery plan.

Product Market Fit: Making Your Products Stand Out in a Crowded Market

Delve into the concept of product-market fit, explore its significance, and equip yourself with practical insights to achieve it effectively.

Consumer Behavior in Online Shopping: A Comprehensive Guide

Ever wondered how online shopping behavior can influence successful business decisions? Read on to learn more.

How to Conduct a First Click Test?

Why are users leaving your site so fast? Learn how First Click Testing can help. Discover quick fixes for frustration and boost engagement.

What is Market Intelligence? Methods, Types, and Examples

Read the blog to understand how marketing intelligence helps you understand consumer behavior and market trends to inform strategic decision-making.

What is a Longitudinal Study? Definition, Types, and Examples

Is your long-term research strategy unclear? Learn how longitudinal studies decode complexity. Read on for insights.

What Is the Impact of Customer Churn on Your Business?

Understanding and reducing customer churn is the key to building a healthy business that keeps customers satisfied. Here's all you need to know about it.

The Ultimate Design Thinking Guide

Discover the power of design thinking in UX design for your business. Learn the process and key principles in our comprehensive guide.

100+ Yes Or No Survey Questions Examples

Yes or no survey questions simplify responses, aiding efficiency, clarity, standardization, quantifiability, and binary decision-making. Read some examples!

What is Customer Segmentation? The ULTIMATE Guide

Explore how customer segmentation targets diverse consumer groups by tailoring products, marketing, and experiences to their preferred needs.

Crafting User-Centric Websites Through Responsive Web Design

Find yourself reaching for your phone instead of a laptop for regular web browsing? Read on to find out what that means & how you can leverage it for business.

How Does Product Placement Work? Examples and Benefits

Read the blog to understand how product placement helps advertisers seek subtle and integrated ways to promote their products within entertainment content.

The Importance of Reputation Management, and How it Can Make or Break Your Brand

A good reputation management strategy is crucial for any brand that wants to keep its customers loyal. Here's how brands can focus on it.

A Comprehensive Guide to Human-Centered Design

Are you putting the human element at the center of your design process? Read this blog to understand why brands must do so.

How to Leverage Customer Insights to Grow Your Business

Genuine insights are becoming increasingly difficult to collect. Read on to understand the challenges and what the future holds for customer insights.

The Complete Guide to Behavioral Segmentation

Struggling to reach your target audience effectively? Discover how behavioral segmentation can transform your marketing approach. Read more in our blog!

Creating a Unique Brand Identity: How to Make Your Brand Stand Out

Creating a great brand identity goes beyond creating a memorable logo - it's all about creating a consistent and unique brand experience for your cosnumers. Here's everything you need to know about building one.

Understanding the Product Life Cycle: A Comprehensive Guide

Understanding the product life cycle, or the stages a product goes through from its launch to its sunset can help you understand how to market it at every stage to create the most optimal marketing strategies.

Empathy vs. Sympathy in UX Research

Are you conducting UX research and seeking guidance on conducting user interviews with empathy or sympathy? Keep reading to discover the best approach.

What is Exploratory Research, and How To Conduct It?

Read this blog to understand how exploratory research can help you uncover new insights, patterns, and hypotheses in a subject area.

First Impressions & Why They Matter in User Research

Ever wonder if first impressions matter in user research? The answer might surprise you. Read on to learn more!

Cluster Sampling: Definition, Types & Examples

Read this blog to understand how cluster sampling tackles the challenge of efficiently collecting data from large, spread-out populations.

Top Six Market Research Trends

Curious about where market research is headed? Read on to learn about the changes surrounding this field in 2024 and beyond.

Lyssna Alternative

Meet Qatalyst, your best lyssna alternative to usability testing, to create a solution for all your user research needs.

What is Feedback Loop? Definition, Importance, Types, and Best Practices

Struggling to connect with your customers? Read the blog to learn how feedback loops can solve your problem!

UI vs. UX Design: What’s The Difference?

Learn how UI solves the problem of creating an intuitive and visually appealing interface and how UX addresses broader issues related to user satisfaction and overall experience with the product or service.

The Impact of Conversion Rate Optimization on Your Business

Understanding conversion rate optimization can help you boost your online business. Read more to learn all about it.

Insurance Questionnaire: Tips, Questions and Significance

Leverage this pre-built customizable questionnaire template for insurance to get deep insights from your audience.

UX Research Plan Template

Read on to understand why you need a UX Research Plan and how you can use a fully customizable template to get deep insights from your users!

Brand Experience: What it Means & Why It Matters

Have you ever wondered how users navigate the travel industry for your research insights? Read on to understand user experience in the travel sector.

Validity in Research: Definitions, Types, Significance, and Its Relationship with Reliability

Is validity ensured in your research process? Read more to explore the importance and types of validity in research.

The Role of UI Designers in Creating Delightful User Interfaces

UI designers help to create aesthetic and functional experiences for users. Here's all you need to know about them.

Top Usability Testing Tools to Try

Using usability testing tools can help you understand user preferences and behaviors and ultimately, build a better digital product. Here are the top tools you should be aware of.

Understanding User Experience in Travel Market Research

Ever wondered how users navigate the travel industry for your research insights? Read on to understand user experience in the travel sector.

Top 10 Customer Feedback Tools You’d Want to Try

Explore the top 10 customer feedback tools for analyzing feedback, empowering businesses to enhance customer experience.

10 Best UX Communities on LinkedIn & Slack for Networking & Collaboration

Discover the significance of online communities in UX, the benefits of joining communities on LinkedIn and Slack, and insights into UX career advancement.

The Role of Customer Experience Manager in Consumer Research

This blog explores the role of Customer Experience Managers, their skills, their comparison with CRMs, their key metrics, and why they should use a consumer research platform.

Product Review Template

Learn how to conduct a product review and get insights with this template on the Qatalyst platform.

What Is the Role of a Product Designer in UX?

Product designers help to create user-centric digital experiences that cater to users' needs and preferences. Here's what you need to know about them.

Top 10 Customer Journey Mapping Tools For Market Research in 2024

Explore the top 10 tools in 2024 to understand customer journeys while conducting market research.

Generative AI and its Use in Consumer Research

Ever wondered how Generative AI fits in within the research space? Read on to find its potential in the consumer research industry.

All You Need to Know About Interval Data: Examples, Variables, & Analysis

Understand how interval data provides precise numerical measurements, enabling quantitative analysis and statistical comparison in research.

How to Use Narrative Analysis in Research

Find the advantages of using narrative analysis and how this method can help you enrich your research insights.

A Guide to Asking the Right Focus Group Questions

Moderated discussions with multiple participants to gather diverse opinions on a topic.

Maximize Your Research Potential

Experience why teams worldwide trust our Consumer & User Research solutions.

Book a Demo

- Form Builder

- Survey Maker

- AI Form Generator

- AI Survey Tool

- AI Quiz Maker

- Store Builder

- WordPress Plugin

HubSpot CRM

Google Sheets

Google Analytics

Microsoft Excel

- Popular Forms

- Job Application Form Template

- Rental Application Form Template

- Hotel Accommodation Form Template

- Online Registration Form Template

- Employment Application Form Template

- Application Forms

- Booking Forms

- Consent Forms

- Contact Forms

- Donation Forms

- Customer Satisfaction Surveys

- Employee Satisfaction Surveys

- Evaluation Surveys