What to Include in Your Business Plan Appendix

Candice Landau

4 min. read

Updated July 11, 2024

While not required, a well-structured business plan appendix goes a long way toward convincing lenders and investors that you have a great business idea and a viable business.

This article will cover what should be part of the appendix in your business plan and best practices for making it a useful part of your business plan .

- What is a business plan appendix?

A business plan appendix provides supporting documentation for the other sections of your business plan .

The appendix for business plans typically comes last and includes any additional documents, spreadsheets, tables, or charts that don’t fit within the main sections of your plan.

What goes in the appendix of a business plan?

In general, here is some of the information you might include in your business plan appendix:

- Charts, graphs, or tables that support sections of your business plan

- Financial statements and projections

- Sales and marketing materials

- Executive team resumes

- Credit history

- Business and/or personal tax returns

- Agreements or contracts with clients or vendors

- Licenses, permits , patents, and trademark documentation

- Product illustrations or product packaging samples

- Building permit and equipment lease documentation

- Contact information for attorneys , accountants, and advisors

You may include some, all, or none of these documents in your business plan appendix. It depends on your business needs and who you share your business plan with.

Tip: Like your executive summary , adjusting what’s in your business plan appendix may be helpful based on the intended audience. For example, if you’re applying for a loan, you may add financial statements from the past 2-5 years to show how your business has performed.

Brought to you by

Create a professional business plan

Using ai and step-by-step instructions.

Secure funding

Validate ideas

Build a strategy

Business plan appendix best practices

Here are a few tips to help you create an appendix for your business plan.

Make it easy to navigate

If your business plan appendix is more than a few pages long or contains a variety of documents, you may want to consider adding a separate table of contents.

Don’t forget security

If you share confidential information within the business plan appendix, you will also want to keep track of who has access to it.

A confidentiality statement is a good way to remind people that the content you share should not be distributed or discussed beyond the agreed parties. You can include it as a separate page or as part of your business plan cover page .

Make the appendix in your business plan work as a separate document

Given that the appendix is the last part of the business plan, it’s quite likely your readers will skip it.

For this reason, it’s important to ensure your business plan can stand on its own. All information within the appendix should be supplementary.

Ask yourself: if the reader skipped this part of my plan, would they still understand my idea or business model ? If the answer is no, you may need to rethink some things.

Connect the appendix to sections of your business plan

Make sure that anything you include in the business plan appendix is relevant to the rest of your business plan. It should not be unrelated to the materials you’ve already covered.

It can be useful to reference which section of your plan the information in your appendix supports. Use footnotes, or if it’s digital, provide links to other areas of your business plan.

Keep it simple

This is good general advice for your entire business plan.

Keep it short.

You don’t need to include everything. Focus on the relevant information that will give your reader greater insight into your business or more detailed financial information that will supplement your financial plan.

Free business plan template with appendix example

Remember, your appendix is an optional supporting section of your business plan. Don’t get too hung up on what to include. You can flag documents and information you believe are worth including in your appendix as you write your plan .

Need help creating your business plan?

Download our free fill-in-the-blank business plan template with a pre-structured format for your appendix.

And to understand what you should include based on your industry—check out our library of over 550 business plan examples .

Business plan appendix FAQ

How do you write an appendix for a business plan?

Gather relevant documents like financial statements, team resumes, and legal permits. Organize them logically, possibly mirroring your business plan’s structure. If long, include a table of contents, ensure each item is relevant, and focus on keeping it simple. If you’re sharing sensitive information, add a confidentiality statement.

Why is a business plan appendix important?

An appendix in your business plan provides supporting evidence for your business plan. It keeps your main plan more concise, enhances credibility with additional data, and can house all-important business documents associated with your business.

What additional information would appear in the appendix of the business plan?

The following can appear in your business plan appendix:

- Financial projections

- Marketing materials

- Team resumes

- Legal documents (like permits and patents)

- Product details (like prototypes and packaging)

- Operational documents (like building permits)

- Professional contact information.

Candice Landau is a marketing consultant with a background in web design and copywriting. She specializes in content strategy, copywriting, website design, and digital marketing for a wide-range of clients including digital marketing agencies and nonprofits.

Table of Contents

- What goes in the appendix?

- Best practices

- Free template

Related Articles

6 Min. Read

How to Write Your Business Plan Cover Page + Template

10 Min. Read

How to Write a Competitive Analysis for Your Business Plan

How to Write the Company Overview for a Business Plan

24 Min. Read

The 10 AI Prompts You Need to Write a Business Plan

The LivePlan Newsletter

Become a smarter, more strategic entrepreneur.

Your first monthly newsetter will be delivered soon..

Unsubscribe anytime. Privacy policy .

The quickest way to turn a business idea into a business plan

Fill-in-the-blanks and automatic financials make it easy.

No thanks, I prefer writing 40-page documents.

Discover the world’s #1 plan building software

What is an Appendix in a Business Plan?

Appendix is an optional section placed at the end of a document, such as a business plan, which contains additional evidence to support any projections, claims, analysis, decisions, assumptions, trends and other statements made in that document, to avoid clutter in the main body of text.

What is Included in an Appendix of a Business Plan?

Appendix commonly includes charts, photos, resumes, licenses, patents, legal documents and other additional materials that support analysis and claims made in the main body of a business plan document around market, sales, products, operations, team, financials and other key business aspects.

The appendix is the perfect place to showcase a wide range of information, including:

- Supporting documentation: References and supporting evidence to substantiate any major projections, claims, statements, decisions, assumptions, analysis, trends and comparisons mentioned throughout the main body of a business plan.

- Requested documentation: Information, documents or other materials that were specially requested by the business plan readers (e.g., lenders or investors) but are too large to place in the main body of text.

- Additional information: Any other materials or exhibits that will give readers a more complete picture of the business.

- Visual aids: Photos, images, illustrations, graphs, charts, flow-charts, organizational charts, resumes.

After reviewing the appendices, the reader should feel satisfied that the statements made throughout the main body of a business plan are backed up by sufficient evidence and that they got even fuller picture of the business.

How Should You Write a Business Plan Appendix? (Insider Tip)

The fastest way to pull the Appendix chapter together is to keep a list of any supporting documents that come to mind while you are in the process of writing the business plan text.

For example, while writing about the location of your business, you may realize the need for a location map of the premises and the closest competitors, demographic analysis, as well as lease agreement documentation.

Recording these items as you think of them will enable you to compile a comprehensive list of appendix materials by the time you finish writing.

Remember to keep copies of the original documents.

Template: 55 Business Plan Appendix Content Samples

For your inspiration, below is a pretty exhaustive list of supporting documentation that typically gets included in the business plan appendix. But please do not feel like you have to include everything from the list. In fact, you definitely shouldn’t!

The purpose of the appendix is to paint a fuller picture of your business by providing helpful supporting information, not to inundate yourself or the readers of your business plan. So, take care to only include what is relevant and necessary .

Company Description

1. Business formation legal documents (e.g., business licenses, articles of incorporation, formation documents, partnership agreements, shareholder agreements)

2. Contracts and legal agreements (e.g., service contracts and maintenance agreements, franchise agreement)

3. Intellectual property (e.g., copyrights, trademark registrations, licenses, patent filings)

4. Other key legal documents pertaining to your business (e.g. permits, NDAs, property and vehicle titles)

5. Proof of commitment from strategic partners (e.g., letters of agreement or support)

6. Dates of key developments in your company’s history

7. Description of insurance coverage (e.g. insurance policies or bids)

Target Market

8. Highlights of relevant industry and market research data, statistics, information, studies and reports collected

9. Results of customer surveys, focus groups and other customer research conducted

10. Customer testimonials

11. Names of any key material customers (if applicable)

Competition

12. List of major competitors

13. Research information collected on your competitors

14. Competitive analysis

Marketing and Sales

15. Branding collateral (e.g., brand identity kit designs, signage, packaging designs)

16. Marketing collateral (e.g., brochures, flyers, advertisements, press releases, other promotional materials)

17. Social media follower numbers

18. Statistics on positive reviews collected on review sites

19. Public relations (e.g., media coverage, publicity initiatives)

20. Promotional plan (e.g., overview, list and calendar of activities)

21. List of locations and facilities (e.g., offices, sales branches, factories)

22. Visual representation of locations and facilities (e.g., photos, blueprints, layout diagrams, floor plans)

23. Location plan and documentation related to selecting your location (e.g., traffic counts, population radius, demographic information)

24. Maps of target market, highlighting competitors in the area

25. Zoning approvals and certificates

26. Detailed sales forecasts

27. Proof of commitment from strategically significant customers (e.g., purchase orders, sales agreements and contracts, letters of intent)

28. Any additional information about the sales team, strategic plan or process

Products and Services

29. Product or service supporting documentation – descriptions, brochures, data sheets, technical specifications, photos, illustrations, sketches or drawings

30. Third-party evaluations, analyses or certifications of the product or service

31. Flow charts and diagrams showing the production process or operational procedures from start to finish

32. Key policies and procedures

33. Technical information (e.g., production equipment details)

34. Dependency on third-party entities (e.g., materials, manufacturing, distribution) – list, description, statistics, contractual terms, rate sheets (e.g., sub-contractors, shippers)

35. Risk analysis for all major parts of the business plan

Management and Team

36. Organizational chart

37. Job descriptions and specifications

38. Resumes of owners, key managers or principals

39. Letters of reference and commendations for key personnel

40. Details regarding human resources procedures and practices (e.g., recruitment, compensation, incentives, training)

41. Staffing plans

42. Key external consultants and advisors (e.g., lawyer, accountant, marketing expert; Board of Advisors)

43. Board of Directors members

44. Plans for business development and expansion

45. Plan for future product releases

46. Plan for research and development (R&D) activities

47. Strategic milestones

48. Prior period financial statements and auditor’s report

49. Financial statements for any associated companies

50. Personal and business income tax returns filed in previous years

51. Financial services institutions’ details (name, location, type of accounts)

52. Supporting information for the financial model projections, for example:

- Financial model assumptions

- Current and past budget (e.g., sales, marketing, staff, professional services)

- Price list and pricing model (e.g., profit margins)

- Staff and payroll details

- Inventory (e.g., type, age, volume, value)

- Owned fixed assets and projected capital expenditure (e.g., land, buildings, equipment, leasehold improvements)

- Lease agreements (e.g., leases for business premises, equipment, vehicles)

- Recent asset valuations and appraisals

- Aged debtor receivable account and creditor payable account summary

- Global financial considerations (exchange rates, interest rates, taxes, tariffs, terms, charges, hedging)

53. Debt financing – documentation regarding any loans, mortgages, or other debt related financial obligations

54. Equity financing – capital structure documentation (e.g., capitalization table, 409A, investor term sheets, stock and capital related contracts and agreements)

55. Personal finance – information regarding owners’ capital and collateral (e.g., Personal Worth Statement or Personal Financial Statement, loan guarantees, proof of ownership)

Related Questions

How do you finish a business plan.

Business plan is finished by summarizing the highlights of the plan in an Executive Summary section located at the beginning of the document. The business plan document itself is finished by an Appendix section that contains supporting documentation and references for the main body of the document.

What is bibliography?

A bibliography is a list of external sources used in the process of researching a document, such as a business plan, included at the end of that document, before or after an Appendix. For each source, reference the name of the author, publication and title, the publishing date and a hyperlink.

What are supporting documents included in a business plan appendix?

Supporting documents in a business plan appendix include graphs, charts, images, photos, resumes, analyses, legal documents and other materials that substantiate statements made in a business plan, provide fuller picture of the business, or were specifically requested by the intended reader.

Sign up for our Newsletter

Get more articles just like this straight into your mailbox.

Related Posts

Recent posts.

AI ASSISTANTS

Upmetrics AI Your go-to AI-powered business assistant

AI Writing Assist Write, translate, and refine your text with AI

AI Financial Assist Automated forecasts and AI recommendations

TOP FEATURES

AI Business Plan Generator Create business plans faster with AI

Financial Forecasting Make accurate financial forecasts faster

INTEGRATIONS

QuickBooks Sync and compare with your QuickBooks data

Strategic Planning Develop actionable strategic plans on-the-go

AI Pitch Deck Generator Use AI to generate your investor deck

Xero Sync and compare with your Xero data

See how easy it is to plan your business with Upmetrics: Take a Tour →

AI-powered business planning software

Very useful business plan software connected to AI. Saved a lot of time, money and energy. Their team is highly skilled and always here to help.

- Julien López

BY USE CASE

Secure Funding, Loans, Grants Create plans that get you funded

Starting & Launching a Business Plan your business for launch and success

Validate Your Business Idea Discover the potential of your business idea

E2 Visa Business Plan Create a business plan to support your E2 - Visa

Business Consultant & Advisors Plan with your team members and clients

Incubators & Accelerators Empowering startups for growth

Business Schools & Educators Simplify business plan education for students

Students & Learners Your e-tutor for business planning

- Sample Plans

WHY UPMETRICS?

Reviews See why customers love Upmetrics

Customer Success Stories Read our customer success stories

Blogs Latest business planning tips and strategies

Strategic Planning Templates Ready-to-use strategic plan templates

Business Plan Course A step-by-step business planning course

Help Center Help & guides to plan your business

Ebooks & Guides A free resource hub on business planning

Business Tools Free business tools to help you grow

What to include in a Business Plan Appendix?

Business Plan Template

- May 2, 2024

A business plan appendix is a great way to add depth to your business plan without making it unbearably long and boring.

However, not everyone needs it. And even when you do, it’s important to understand what this section entails and how you can make it useful.

Well, we will figure that out in this blog post.

But before that, what exactly is an appendix in a business plan?

What is a business plan appendix?

A business plan appendix is the last section of your business plan that contains supplementary information and documents to support the claims your plan makes.

This may include a couple of technical documents, detailed financial statements, charts, spreadsheets, and other additional documents that were too detailed or extensive to include within the main sections.

It’s like a reference point for readers who want to gather detailed insights about the information you presented in your business plan.

Let’s understand what the business plan appendix includes in brief detail:

What to include in the appendix of a business plan?

Depending on your business needs and the intended audience for your business plan, the appendix section may include some of these documents.

- Supplementary information

- Legal documents

- Organizational and personnel details

- Additional financial documents

- Achievements and testimonials

Let’s understand what the appendix business plan includes in brief detail:

1. Supplementary information

Here, you can include documents to support and elaborate on some information mentioned in other sections of your business plan.

Some examples of supplementary information include,

- Charts, graphs, and tables used in the analysis

- Sales and marketing material

- Website and social media documentation

- Raw data, research methods, and research protocols

- Questionnaires and survey instruments

- Product blueprints and images

- Technical and user documentation

- Detailed competitor analysis

- Property designs

2. Legal documents

Adding legal and compliance documents to your appendix will demonstrate your adherence to regulations and legal standards. Such transparency will help win the trust of your stakeholders and potential investors.

Here are a few examples of the kinds of legal documents you can add.

- Incorporation papers

- Licenses and Permits

- Intellectual properties, i.e. trademarks, copyright, patents.

- Building permits and rental agreements

- Supplier and vendor contracts

- Equipment documentation

- Stock certificates

3. Organizational and personnel details

In this section, you will offer information that will let readers have a peek into the workings of your company and the people behind it. Some of these documents include

- Organizational chart

- Job descriptions and hiring procedures

- Resumes for executive positions

- Certifications and degrees

- Affiliates such as attorneys or accountants

4. Additional financial documents

The main body of your financial plan already includes adequate financial information. However, depending on your audience, they might need access to certain additional information such as:

- List of assets within the business

- Credit history

- Business and personal tax returns

- Spreadsheets of financial projections

- Historical and current financial statements

- Equity structure and debt repayment plan

- SBA (Small Business Administration) loan agreements and business loans.

5. Achievements and testimonials

Lastly, you can include proof of achievements that can help establish your brand’s credibility and performance. This is a great place to highlight:

- Media and press clippings

- Testimonials and success stories

- Expert endorsements

- Awards and achievements

And those are pretty much all the things you will include in your plan. Let’s now create an appendix suited for your business plan.

Tips and best practices for business plan appendix

Before you kickstart writing your appendix, we have a few tips to help you make this section more enriching.

1. Make it scannable

Keep the contents of your appendix simple and easy to navigate. If you are planning to add a variety of documents, consider adding a table of contents to help readers find what they need easily.

2. Relate to the business plan

Everything you include in your appendix should be relevant to the contents and elements of your business plan .

You can add footnotes or a link by referencing the supplementary documents to the business plan information it supports.

3. Include the confidentiality statement

If you are adding financial statements or any legally classified information, add a confidentiality statement. This is an effective way of ensuring that the parties with access to confidential information don’t share it with anyone else.

4. Keep the appendix supplementary

When you write a business plan ensure that the document stands on its own without relying on the appendix. Your readers are likely to skip this section, so you don’t want to risk having inadequate information in the main body.

Your appendix should only cover supplementary and supporting information, not any core detail that the reader must quintessentially know.

Start preparing your business plan with the appendix

Now, don’t get caught up trying to figure out what to include in your appendix. Focus on writing your business plan, and you will eventually get a gist of supporting documents essential for your plan.

However, what if you need help writing your business plan in the first place? In that case, a business planning app or sample business plans would help.

For instance, Upmetrics’ AI business plan generator can help create compelling business plans from scratch in less than 10 minutes.

All you have to do is answer some tailored business questions, and an AI assistant will do everything else for you.

Build your Business Plan Faster

with step-by-step Guidance & AI Assistance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is the appendix important in a business plan.

Yes, the appendix is an important section of your business plan. Although it’s not compulsory, adding an appendix will help your investors and other audiences gather the required information in in-depth detail. An appendix helps you prove the viability of claims made in different sections of your plan.

How do you write an appendix for a business plan?

Follow these steps to write your appendix section:

- Gather all the supplementary documents you want to include in this section.

- Organize them logically based on the structure of your plan or their content nature, i.e. financial documents, legal documents, marketing materials, etc.

- Label the documents and present them neatly in a professional stack without creating clutter.

- Add footnotes and links to the relevant business plan sections and create a table of contents to make the information easily scannable.

Do I need a table of contents for the appendix?

It’s recommended to have a table of contents especially if you are adding multiple long documents supporting different sections of your business plan information.

Are there any online resources for creating a business plan appendix?

Business plan templates are the best resources for creating a clear and impactful appendix section. Most business plan templates online have a section for appendix which can be easily edited to suit your needs.

About the Author

Upmetrics Team

Upmetrics is the #1 business planning software that helps entrepreneurs and business owners create investment-ready business plans using AI. We regularly share business planning insights on our blog. Check out the Upmetrics blog for such interesting reads. Read more

Reach Your Goals with Accurate Planning

What Is an Appendix in a Business Plan?

- Small Business

- Business Planning & Strategy

- Business Plans

- ')" data-event="social share" data-info="Pinterest" aria-label="Share on Pinterest">

- ')" data-event="social share" data-info="Reddit" aria-label="Share on Reddit">

- ')" data-event="social share" data-info="Flipboard" aria-label="Share on Flipboard">

Steps to Writing a Business Proposal

What are the components of a good business plan, how to simply write a business plan for a loan.

- 3 Types of Business Documents

- How to Format a Business Plan in Writing

It's doubtful that Violet Fane was referring to an appendix in a business plan when she wrote that “all things come to those who wait.” After all, Lady Mary Montgomerie Currie – as she was formally known – was an English poet who made her mark in the late 1800s. Then again, small-business owners wrote business plans during her lifetime, and her oft-repeated phrase captures almost perfectly the bounty of information that can be found at the very end of what is usually a lengthy document.

">For the Body, Stick to Your Business Plan

While you're not obligated to include an appendix in your business plan, it's difficult to imagine a plan without one. This is the section that includes all the supporting documents that will substantiate, clarify and help your readers visualize points that you make in your business plan.

These documents are crucial, but they make up the very last section of a business plan for good reason: Tucking them into the actual business plan could distract your readers from the primary points you're trying to make in the body of your report. As ancillary information, they would interrupt the natural flow of the narrative.

An Appendix in a Business Plan Affords Choices

Emphasize the best accomplishments and most notable achievements of your management team in this section of your business plan. Then, at some point early in this section, you can place a parenthetical reference to the inclusion of their resumes. For example: “See Appendix, page XX, for management team resumes.”

This way, your business plan will stand on its own merits. The reader can decide for himself whether to:

- Keep reading the business plan, uninterrupted. Stop reading the plan temporarily so he can jump to the pertinent page in the appendix. Read the entire appendix, or parts of it, when he is done reading the business plan.* Skip the appendix altogether.

Skipping Should Be an Option

As difficult as this last scenario may be to contemplate, the possibility definitely exists. As the business plan creator – The most important thing to remember – is that you fulfill your role to the best of your ability: You must present a thoughtful, comprehensive business plan that anticipates and addresses the reader's questions.

The reader should be able to skip the appendix without encountering any gaps in understanding. The information he will find there is intended to be supplementary – not perfunctory.

The reader may also be guided by his interests or motivations – and will make his decision accordingly. For example, an attorney may actively read the appendix to scour patent and trademark information. A lender may not find this information as compelling as a business' credit history. In this instance, the appendix could end up being the very first thing he reads.

Consider Business Appendix Examples

When an appendix is thoughtfully and creatively presented, it can be the most entertaining part of a business plan, exactly as Lady Mary had suggested.

Content should always be your guide, just as surely as you should include copies rather than original documents in the appendix. Consider your options, which depend on the content in your business plan:

- Building permits.

- Charts and graphs.

- Competitor information.

- Credit reports.

- Equipment documentation.

- Incorporation papers.

- Leases or rental agreements.

- Legal documents.

- Letters of recommendation.

- Licenses, permits, trademarks and patents.

- List of business affiliates, such as your accountant and attorney.

- Marketing reports and studies.

- Pending contracts.

- Pictures or illustrations of your product line.

- Press clippings, feature articles and other media coverage.

- Spreadsheets.

- Tax returns.

- Vendor agreements.

Streamline the Appendix in Your Business Plan

If your appendix becomes robust – say, more than 10 pages long – it might be helpful to create a table of contents on a preceding page to guide your readers through it. And if you're worried about confidentiality, it might be wise to include a privacy statement that reminds readers that they are not authorized to distribute copies of your business plan to third parties.

All good things may indeed come to those who wait – or at least those who ask for permission first.

- The Phrase Finder

- U.S. Small Business Administration: Write your business plan

- Bplans: What to Include in Your Business Plan Appendix

Mary Wroblewski earned a master's degree with high honors in communications and has worked as a reporter and editor in two Chicago newsrooms. Then she launched her own small business, which specialized in assisting small business owners with “all things marketing” – from drafting a marketing plan and writing website copy to crafting media plans and developing email campaigns. Mary writes extensively about small business issues and especially “all things marketing.”

Related Articles

How to write the management team section of a business plan, why is an effective business plan introduction important, what does "abridged" mean on a business plan, what is an executive summary business plan, what are the major parts of a business letter, how to write an executive summary on a marketing plan, final summary for a marketing plan, how to write a preface for a business plan, what is the importance & purpose of a business plan, most popular.

- 1 How to Write the Management Team Section of a Business Plan

- 2 Why Is an Effective Business Plan Introduction Important?

- 3 What Does "Abridged" Mean on a Business Plan?

- 4 What Is an Executive Summary Business Plan?

Everything You Need to Know about the Business Plan Appendix

After taking time in writing a business plan , you want it to be read. That means the body should be no more than 15 pages in length. That’s where the business plan appendix comes in!

The appendix in a business plan is a supplementary section that contains additional information and supporting documents, such as charts, graphs, financial statements, market research, and legal papers, which complement the main body of the plan.

Although the final section of a comprehensive business plan, the appendix is an integral part of your plan. For example, suppose you are using your business plan to attract investors. In that case, the additional documents in the appendix will provide greater insight and can help convince your potential investors that you’ve got a solid business concept. You’ve done the research necessary to support the claims and forecasts included in the other sections of your plan.

In this blog post, we’ll discuss everything you need to know about the business plan appendix so that you can start developing a great appendix for your business plan.

Download our Ultimate Business Plan Template here

What is a Business Plan Appendix?

The appendix is used to provide supporting documentation for key components in your business plan, such as financial statements or market research.

The appendix is also a great place to put any other tables or charts you didn’t want to put in the main body of the business plan. Depending on the intended audience of your business plan, you may also want to include additional information such as intellectual property documentation, credit history, resumes, etc.

What is the Purpose of the Business Plan Appendix?

The purpose of the appendix is to provide supporting documentation or evidence for key components in your business plan. While you may include charts in graphs in the body of your plan, these should be summary projections, while the fully detailed charts and tables would be found in the appendix.

How to Write the Business Plan Appendix for Your Company

Several supporting documents should be included in the appendix:

Full Financial Projections

Business plans used to raise capital or loan applications will typically need more detailed projections, including monthly, quarterly and/or annual cash flow statements, balance sheets, and income statements.

Customer Lists

This can be helpful for companies looking to expand their market presence and reach new customers or clients, as well as those who are considering investing capital into your business.

Customer Testimonials

Testimonials from your current customers are a great way to help other investors and lenders feel more confident in investing or loaning money to your business. You can include online reviews, letters, personal email communications, etc.

Intellectual Property Documentation

This should be included if you have any patents or trademarks registered and might also be helpful if you are using any technologies that other businesses have patented.

Management Team

This can include organizational structure, job descriptions, resumes, certifications, advanced degrees (i.e., Master’s degree in a specialized area), etc., that will help establish the expertise and experience that supports your business’s success.

Leases & Customer Contracts

Businesses need to comply with all leases and customer contracts before seeking investors. You may include rental agreements, copies of key agreements, sample customer contracts, etc.

Building & Architectural Designs

Businesses looking to build or expand their operations will need access to building plans, architectural drawings, permits, etc.

Finish Your Business Plan Today!

Quickly & easily complete your business plan: Download Growthink’s Ultimate Business Plan Template and finish your business plan & financial model in hours.

Some small business owners may also include the following documents in the appendix:

Company History and Background

Businesses with a lot of competition in their industry will need to include more detail. Business plans for major businesses should have the company history section last so that you can provide additional information about your competitors or other companies that are relevant to your business plan. Businesses planning on using their business plan as an internal document can use less detail here.

Market Analysis

Your market analysis should include relevant information about how you defined your industry, potential customers and competitors, etc. Include any identifiable risks and assumptions based on your market research.

Individual & Business Credit History

If you don’t have much experience with business credit or borrowing, it might be worth adding a short explanation of your current and past financing use, including your tax returns and incorporation papers. This is especially helpful if you plan to apply for a loan through the Small Business Administration (SBA).

Marketing Materials & Plan

For some entrepreneurs, the marketing section of the business plan only provides a brief overview of their marketing strategy. Attaching the complete Marketing Plan in the appendix section of a business plan helps your reader understand if you’ve thought through your target audience, where you should target your marketing efforts, and how you will advertise to them to expand awareness of your brand and sales of your products and/or services.

Best Practices for Your Business Plan Appendix

- Table of Contents : If you are including several documents in the business plan appendix, include a table of contents for your reader’s easy reference.

- Confidentiality Statement : If you include credit history documents, intellectual property diagrams or applications, or any other legal documents with confidential information, have a Confidentiality Statement within the appendix to remind your readers that they are not to share or discuss the information within your plan without your written consent.

- Short & Simple : This business plan section is likely to be skipped unless your reader is looking for specific information to support a claim in your business plan. Think about your intended reader and only include what is necessary to help make your request (e.g., business partner proposal, raise funding, etc.) and support your business plan.

As a business owner, you want to keep your business plan short so that it gets read. The Business Plan Appendix is a great way to include additional information about the preceding sections without adding to the length of your document.

At Growthink, we have 20+ years of experience in developing business plans for a variety of industries. We have 100+ business plan examples for you to use as a guide to help you write your business plan. You can also get our easy-to-use business plan template to help you finish your plan in less than one day.

How to Finish Your Business Plan in 1 Day!

Don’t you wish there was a faster, easier way to finish your business plan?

With Growthink’s Ultimate Business Plan Template you can finish your plan in just 8 hours or less!

Other Resources for Writing Your Business Plan

- How to Write an Executive Summary

- How to Expertly Write the Company Description in Your Business Plan

- How to Write the Market Analysis Section of a Business Plan

- The Customer Analysis Section of Your Business Plan

- Completing the Competitive Analysis Section of Your Business Plan

- How to Write the Management Team Section of a Business Plan + Examples

- Financial Assumptions and Your Business Plan

- How to Create Financial Projections for Your Business Plan

- Business Plan Conclusion: Summary & Recap

Other Helpful Business Plan Articles & Templates

Financial modeling spreadsheets and templates in Excel & Google Sheets

- Your cart is empty.

The Ultimate Guide: What Is Appendix In Business Plan

The Role of the Appendix in a Business Plan: Essential Components and Purpose

When it comes to crafting a business plan, one section often overlooked is the appendix. The appendix serves as a crucial support tool, offering additional insights and details that enhance the main body of the plan. It’s not just filler; it’s a vital part of the document that can make a significant impact on investors and stakeholders. Understanding the role of the appendix and its essential components is key for anyone looking to develop a comprehensive business plan.

The appendix typically appears at the end of the business plan and can include a variety of content, such as:

- Charts and graphs

- Detailed financial projections

- Resumes of key team members

- Market research data

- Legal documents

- Any additional reference materials

This additional information helps to substantiate the claims made in the business plan, providing the necessary evidence that supports your vision, goals, and methods for achieving them. Without it, the main content may appear superficial or incomplete.

One of the primary purposes of including an appendix is to declutter the main sections of your plan. By placing extensive details in the appendix, you maintain a clean, focused narrative that allows readers to grasp your business model and strategy without being bogged down by excessive information. It’s all about enhancing clarity while ensuring that interested parties have access to in-depth data.

Let’s explore some essential components that should typically find their way into the appendix:

Detailed Financial Information

Investors are keenly interested in numbers. Including worksheets that outline your financial projections—like income statements, cash flow forecasts, and balance sheets—can give investors confidence in your business acumen. Make sure to represent this information clearly; consider using tables for better visualization.

| Financial Metric | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | $100,000 | $150,000 | $200,000 |

| Net Profit | $20,000 | $35,000 | $50,000 |

| Operating Expenses | $80,000 | $100,000 | $120,000 |

Market Research Data

Your market research provides context for your business strategy. Including surveys, focus group findings, or statistics that confirm your target audience can enhance your credibility. Make sure to reference where these data points came from, so readers can verify the information independently.

Team Resumes

The experience and background of your team can greatly influence potential investors’ decisions. Including detailed resumes or profiles of key team members showcases their qualifications and reinforces the proficiency behind your business strategy. Highlight strengths that align with the goals of your business.

Legal Documents

Any legal documentation—like patents, trademarks, or leases—should also go in the appendix. This information is pertinent as it protects your intellectual property and establishes credibility. When investors see this documentation, they feel more secure about the investment opportunity.

While it’s essential to include a wealth of information, it’s equally important to keep the appendix organized. A well-structured appendix allows for easy navigation. Use clear headings, bullet points where appropriate, and a table of contents if your appendix is particularly lengthy. The goal is to make it straightforward for readers to locate the information they need.

In essence, the appendix is more than an afterthought; it is an integral component of a robust business plan. By effectively using the appendix to provide relevant and detailed supplementary information, you not only strengthen your business case but also demonstrate a level of professionalism and thoroughness that can resonate strongly with potential investors and partners. The role of the appendix cannot be undervalued—it’s your opportunity to shine a light on the strengths and viability of your business.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Creating a Business Plan Appendix

Creating a business plan is a critical step for any entrepreneur looking to secure funding or articulate their business strategy. One key component of this plan is the appendix. However, many people stumble on this important part. By identifying common mistakes, you can craft an appendix that enhances your business plan rather than detracts from it.

Not Understanding Its Purpose

One of the most frequent errors is misunderstanding the purpose of the appendix. It serves as a supplemental section that provides additional information, supporting documents, charts, and data that are too lengthy for the main body of the business plan. If you treat it like a minor afterthought, you risk losing a vital opportunity to bolster your main arguments.

Overloading with Extraneous Information

While it’s essential to include supportive content, overloading your appendix with irrelevant information can backfire. Including too much data or documents that don’t directly support your business plan can overwhelm the reader. Instead, focus on adding only necessary details. For instance, you might include:

- Resumes of key personnel

- Financial statements

Remember, quality over quantity is the key here.

Failing to Label Documents Clearly

Another common pitfall is failing to label documents clearly. If your appendix contains various forms, charts, or graphs, make sure each one is appropriately labeled and referenced within the main body of the business plan. Use straightforward titles such as “Market Research Data” or “Financial Statements” to ensure clarity. A well-organized appendix helps guide the reader through the additional information without creating confusion.

Ignoring Formatting Consistency

Consistency in formatting is crucial for professionalism. If your main business plan is written in a particular font, size, and style, maintaining that same formatting in the appendix is vital. Discrepancies can distract the reader and detract from the coherence of your entire document. Use bullet points, tables, and headers to structure your appendix for better readability.

Formatting Tips

- Fonts : Use the same typeface throughout (e.g., Arial, Times New Roman).

- Size : Keep font size consistent, preferably between 10-12pt.

- Margins : Maintain uniform margins (1 inch is standard).

- Indentations : Use similar indentations for bullet points and paragraphs.

Not Referencing the Appendix in the Main Plan

Another error is not referencing the appendix throughout the main business plan. When you mention specific data or findings within your plan, direct readers to the relevant part of the appendix for more elaboration. For instance, you could say, “As illustrated in Appendix A, our market research indicates a growing trend in eco-friendly products.”

Assuming Everyone Knows the Content

It’s easy to assume that reviewers are familiar with the details of your industry or market. However, this is rarely the case. Avoid using jargon or industry-specific terms without explanation. Define any acronyms or methodologies you use in the appendix. Clarity is key, so think about your audience’s perspective.

Forgetting to Proofread

Typos and grammatical errors can damage the credibility of your business plan. If you overlook proofreading the appendix, it may give the impression that you lack attention to detail. Always take the time to review your appendix thoroughly or have a second set of eyes go through it to catch any mistakes.

Neglecting to Provide Context for Data

Including data without context is a critical mistake. Numbers can be misleading without proper explanation. For each chart or statistic you present, offer a brief summary or analysis that helps the reader understand its relevance. For instance, if you present financial projections, accompany them with notes on the assumptions made and the methodology used to arrive at those figures.

Quick Reference Checklist for Your Appendix

| Mistake | Tips to Avoid |

|---|---|

| Misunderstanding the Purpose | Clarify its supplemental nature. |

| Overloading Information | Include only relevant, necessary details. |

| Failing to Label Clearly | Use clear, descriptive titles for documents. |

| Ignoring Consistency | Match formatting with the main business plan. |

| No References | Direct readers to the appendix throughout the document. |

| Assuming Knowledge | Define jargon and provide context. |

| Forgetting Proofreading | Review thoroughly to catch errors. |

By carefully considering these common mistakes and their remedies, you can create an effective appendix that adds significant value to your business plan. A well-structured appendix not only enhances the clarity of your document but also helps you make a stronger case to potential investors or stakeholders.

How to Effectively Organize Your Business Plan’s Appendix

Creating a well-organized appendix is crucial for any business plan. It not only provides vital information but also enhances the overall professionalism and credibility of your document. The appendix serves as a place to include supporting documents that are too lengthy, detailed, or specific to fit within the main body of the business plan. Here’s how to effectively organize it.

Understand the Purpose of the Appendix

Your appendix shouldn’t just be a dumping ground for all your documents. Each item should serve a specific purpose. The main objective is to support the content of your business plan, giving readers easy access to supplementary information that reinforces your arguments or proves your claims. By clearly understanding this, you can filter out unnecessary documents and focus on what’s most important.

Identify the Key Documents

Start by jotting down a list of potential items you might include in your appendix. Consider these common categories:

- Financial Statements: Profit and loss statements, cash flow forecasts, and balance sheets.

- Market Research: Charts, surveys, and data analytics that substantiate your market analysis.

- Resumes: Backgrounds of key team members that outline their expertise and contributions.

- Legal Documents: Licenses, permits, or contracts that verify your operational capacity.

- Marketing Material: Samples of ads, brochures, or promotional strategies that illustrate your marketing approach.

Make sure each document is relevant and adds value to the reader’s understanding of your business.

Organizing the Documents

Once you’ve identified the documents you want to include, the next step is to organize them logically. A recommended approach is to categorize similar documents together. Here’s a structured layout you might consider:

- Financial Documents

- Market Analysis

- Company Information

- Legal Documentation

- Resumes of Key Personnel

- Additional Supporting Documents

By categorizing your appendix in this manner, you help guide your readers to find the information they need swiftly, improving their overall experience.

Numbering and Referencing

When you reference documents in the main body of your business plan, ensure that you follow a systematic numbering style. For instance, you could refer to “Appendix A: Financial Statements” or “Appendix B: Market Research.” This simple method allows readers to easily cross-reference what they are reading with the appendix.

Formatting Guidelines

Always maintain consistency in formatting. Use the same font and size as the rest of your business plan, and make sure every section of the appendix is clearly labeled. You might consider using bullet points or tables for easy readability. Here’s a small example of how you could structure financial data:

| Year | Revenue | Expenses | Profit |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | $100,000 | $70,000 | $30,000 |

| 2024 | $150,000 | $90,000 | $60,000 |

This visual representation can often convey important information faster than pages of text.

Review and Edit

Once you have completed your first draft of the appendix, take time to review and edit. Check for clarity, coherence, and relevance of each document. Ask yourself whether each item strengthens your business plan or detracts from it. Be thorough; typos and inconsistencies can undermine your credibility.

Updating Regularly

Keep your appendix updated as your business evolves. Financial projections and market conditions can change, and your appendix should reflect the most current information. Regular updates not only keep your plan relevant but also show stakeholders and potential investors that your business is dynamic and responsive.

This meticulous approach to organizing your business plan’s appendix can set your document apart and serve as a valuable resource for anyone reviewing your business strategy. By following these best practices, you can ensure that your appendix complements your business plan effectively, ultimately fostering greater confidence in your enterprise.

Integrating Financial Statements and Documents in Your Business Plan Appendix

Financial statements and supporting documents into your business plan appendix is crucial for presenting a well-rounded view of your business’s financial health. This part of your plan serves as a detailed reference point that can significantly influence potential investors, lenders, and partners. Here’s how you can effectively integrate these financial components into your appendix.

Understanding Financial Statements

Financial statements offer a snapshot of your business’s performance and condition. Generally, there are three primary types you should include:

- Income Statement: Also known as the profit and loss statement, it summarizes revenues, costs, and expenses to highlight profitability over a specific period. An effective income statement allows stakeholders to gauge your business’s operational efficiency.

- Balance Sheet: This document reflects your business’s assets, liabilities, and equity at a given date. It provides insights into what your business owns and owes, which is essential in assessing financial stability.

- Cash Flow Statement : This statement tracks cash inflows and outflows, showing how well you manage your cash resources. It’s particularly important for understanding how operations affect your cash position over time.

Additional Essential Documents

Beyond the primary financial statements, the following documents can enhance your appendix and provide a more comprehensive view:

- Projected Financial Statements: These forecasts can help demonstrate your business plans and expected financial trajectory, providing potential investors with insight into future profitability.

- Break-even Analysis: This analysis helps investors understand when your business will become profitable. It effectively shows the relationship between costs, production volume, and profit margins.

- Funding Requirements: Outline how much funding you need and the intended use of these funds. Clearly defined funding purposes bolster your credibility and reassure potential investors.

Organizing Financial Information

A clear and logical structure is key when organizing these documents. Here’s a recommended layout for your appendix:

- Start with your Income Statement , followed by the Balance Sheet and Cash Flow Statement .

- Follow these with your Projected Financial Statements and Break-even Analysis .

- Conclude the financial section with detailed Funding Requirements and supporting documents like tax returns, company valuations, and any current debts.

Formatting for Clarity

Using tables can significantly increase clarity and readability. For instance, here’s an example of how you might present an income statement in a table format:

| Revenue | Amount |

|---|---|

| Total Revenue | $500,000 |

| Cost of Goods Sold | ($200,000) |

| Operating Expenses | ($100,000) |

Maintaining Consistency

Ensure consistency in formatting throughout your financial documents. Use similar fonts, sizes, and styles to provide a professional appearance that reflects your attention to detail. This consistency not only enhances readability but also reinforces trust in your business practices.

Final Thoughts

Integrating financial statements and documents into your business plan appendix can set you apart in important discussions with potential stakeholders. This section serves as a vital resource for providing insights into your financial health and future plans. By presenting clear, concise, and well-organized financial documents, you enhance your credibility and give decision-makers the information they need to support your business’s growth.

Case Studies: Successful Business Plans with Strong Appendices

When examining successful business plans, the significance of the appendix emerges as a crucial component that can often tip the balance between a standard plan and an exceptional one. The appendix serves not just as a catch-all for supplementary materials, but as a strategic tool that adds depth and credibility to a business plan. Various case studies highlight how strong appendices have contributed to business success, providing valuable insights for aspiring entrepreneurs.

One standout example is the business plan of a tech startup aiming to develop a new software application. This startup recognized that the viability of their business relied heavily on demonstrating technical feasibility and market potential. The appendix included robust market research data, competitor analysis, and detailed projections that underlined their growth strategy. For instance, they provided demographic statistics along with potential customer personas, making it crystal clear who their target audience was.

Furthermore, it contained screenshots of the working prototype, demonstrating not only their technical capabilities but also their commitment to innovation. Such inclusion not only amplified their story but also gave potential investors confidence in their approach. By providing well-organized and easily digestible information in the appendix, they engaged their audience effectively and turned interest into investment.

Another case involves a restaurant looking to attract investors through a carefully crafted business plan. The appendix, in this case, included critical components like sample menus, detailed sourcing information for local suppliers, and photographs of the intended aesthetic for the dining space. This illustrated their vision thoroughly, beyond just the numbers. Investors could visualize the experience they would be providing, which significantly enhanced the restaurant’s appeal.

The appendix also presented market trends specific to the region, showcasing a growing consumer interest in local, sustainable dining options. By connecting these dots, they painted a compelling picture that combined passion with a solid business rationale.

A retail company seeking expansion also leveraged its appendix effectively. In this case, the appendix was packed with data supporting its claim for additional funding. It included:

- Sales projections based on historical data

- Detailed accounts of demographic trends in their primary market

- Customer testimonials and case studies from loyal shoppers

Each element contributed to a narrative that positioned the business as an industry leader ready for growth. By illustrating past successes and aligning them with market trends, they could persuade investors that their expansion was not just possible but inevitable.

Equally important was a consulting firm’s business plan, which showcased the extensive credentials of their team through a meticulously crafted appendix. This included:

| Team Member | Experience | Specialization |

|---|---|---|

| Jane Doe | 10 Years in Finance | Financial Modeling |

| John Smith | 5 Years in Marketing | Brand Strategy |

| Susan Lee | 12 Years in HR | Talent Management |

This type of information not only highlighted the firm’s human capital but also displayed their collective expertise, fostering trust among potential clients and investors. It drove home the idea that the firm was well-equipped to handle projects of varying complexity.

In all cases, the appendices served as a means of fortifying the primary narratives presented in the business plans. When planning your own business, consider how you can utilize the appendix to support your claims, provide evidence, and offer a complete picture of your venture. Key elements such as market analysis, financial projections, team qualifications, and visual aids can be integral in persuading stakeholders and securing necessary funding .

The reality is that in today’s competitive landscape, detailed appendices can no longer be an afterthought. They must be strategically integrated to substantiate your business case. Whether it’s photos, charts, market research, or personnel bios, strong appendices enhance engagement and expand understanding, effectively transforming your business plan into a powerful tool for communication. Ultimately, well-prepared appendices contribute not just to securing investments but also to laying the groundwork for sustainable business growth.

Key Takeaway: When crafting a business plan, one aspect that often gets overlooked is the appendix. The appendix serves as a supplementary section that can greatly enhance the overall effectiveness of your business plan. Understanding its role is vital, as it houses essential components like charts, graphs, contracts, and detailed explanations that support the main narrative of the business plan. Not only does the appendix provide depth, but it also serves a strategic purpose—it can clarify your business’s operations and reinforce your financial projections. However, creating an effective appendix comes with its own set of challenges. Common mistakes include overloading it with irrelevant material or failing to label documents properly. It’s crucial to focus on quality over quantity; including only what strengthens your business case while maintaining a clear organization will improve readability. A well-structured appendix not only impresses potential investors but also allows them to find pertinent information quickly, which could make or break their decision. To maximize the impact of your appendix, effectively integrating financial statements and necessary documents is essential. Clear and concise financial reports can provide a compelling argument for your business’s viability. A successful appendix would include projections, cash flows, and balance sheets that are well-explained and contextualized within your plan. This level of detail ensures transparency and helps potential stakeholders understand the financial health of your venture. Additionally, looking at case studies of successful business plans with strong appendices can offer valuable insights. By examining what worked for others, you can glean effective strategies and avoid pitfalls, thus reinforcing the importance of a robust appendix. The appendix in a business plan is far from a mere afterthought; it is a critical component that enhances understanding, builds credibility, and provides essential support for your business narrative. A well-organized and thoughtfully curated appendix can significantly improve the chances of your business plan capturing the attention and interest of potential investors, stakeholders, or partners.

Crafting a comprehensive business plan is a vital step in ensuring the success of your business endeavors. Among its many components, the appendix plays a crucial role that shouldn’t be overlooked. As we’ve explored, the appendix not only supplements your business plan with essential information but also serves to clarify your vision for potential investors and stakeholders. It’s the section that provides deeper insights into the data and documentation that support your business strategies. Therefore, understanding the role of the appendix and its essential components is paramount in your planning process.

When creating your business plan appendix, awareness of common pitfalls can save you from detracting from the professionalism of your plan. Avoiding excessive jargon and irrelevant information is critical. Remember that the appendix should serve to enhance the main text of your business plan, not burden it with unnecessary details. By focusing on key documentation such as resumes, charts, and other supporting materials, you ensure that your appendix is effective and engaging.

Effective organization within your appendix is equally important. A well-structured appendix assists in providing clarity and makes navigation easier for readers. Consider categorizing documents logically based on their relevance – for instance, grouping financial statements together or separating research data from promotional materials. Adopting clear headings and page numbers can significantly improve the usability of your appendix, allowing readers to quickly locate the information they need. Structuring your appendix well not only presents information in a digestible manner but also reflects your attention to detail and professionalism.

Integrating financial statements and documents into your business plan appendix is another vital consideration. Your financial data serves as the backbone of your business narrative; people want to see that your projections are not just hopeful dreams but grounded in reality. Including detailed financial statements such as income statements, balance sheets, and cash flow projections provides a clear and comprehensive financial picture. Make sure your financial documents are up-to-date and consistent with the figures presented in the main business plan. Transparency in your financial reporting adds credibility to your entire business proposal and reassures potential investors of your fiscal responsibility.

Examining case studies of successful business plans that feature strong appendices reveals valuable insights. These examples demonstrate how well-crafted appendices complement a solid business model and contribute to an overall cohesive plan. By analyzing how others structured their appendices, you can uncover strategies and elements that resonate with your vision and adapt them to your own plan. This not only nurtures your creativity but also instills confidence that you’re on the right track.

All in all, the appendix of your business plan is much more than just an add-on; it’s an essential weapon in your business strategy arsenal. It houses the evidence that supports your business rationale, making it a powerful tool to persuade stakeholders of your vision and potential for success. By taking careful steps to avoid common mistakes, organizing your appendix effectively, integrating critical financial data, and learning from successful case studies, you build a robust appendix that enhances your overall business plan.

The journey of drafting a business plan can be overwhelming, but focusing on the appendix can facilitate a smoother process. When you give the appendix the attention it deserves, you create a clearer connection between your business goals and the strategic planning needed to achieve them. Remember, every successful business starts with a solid foundation, and a well-structured appendix solidifies that foundation.

Consider your audience while developing your appendix; think about what they are looking for and the questions they may have. This perspective can help tailor your content and improve its relevance. In the end, an effective appendix not only addresses potential concerns but also highlights the strengths of your business model.

As you embark on your business journey, prioritize the appendix. Use it as a tool for storytelling and clarity, a showcase of your diligence and expertise, and a means to instill confidence in your stakeholders. With a strong appendix, you set the stage for a successful business plan that resonates with readers, inviting them to invest in your vision. Take the time to hone this critical aspect, and it will undoubtedly lead to a more compelling and effective business plan overall.

Beverage Manufacturing Start-up Financial Model

The beverage manufacturing industry is a dynamic and rapidly growing sector that caters to a diverse market ranging from soft drinks and juices to alc... read more

- Excel Model – $199.95 Version 5.2

- PDF Demo – $0.00 Version 5.2

Liquor Distillery Financial Plan Template

Distilleries, with their rich history of crafting spirits, have experienced a resurgence in popularity, driven by consumer interest in artisanal and l... read more

- Excel Version – $199.95 Version 5.5

- PDF Demo Version – $0.00 Version 5.5

Corporate Finance Toolkit – 25 Financial Models Excel Templates

The toolkit is an essential resource for any organization, providing a comprehensive collection of tools and templates designed to streamline financia... read more

- All Excel Model Templates – $249.00 Version 1

- PDF Demo & Excel Free Download – $0.00 Version 1

Taxi Company Business Financial Model

Embark on the road to success by starting your own Taxi Company Business. This comprehensive 10-year monthly Excel financial model template offers an ... read more

- Excel Version – $129.95 Version 1.5

- PDF Demo Version – $0.00 Version 1.5

Trucking Company Financial Model

Embrace the road ahead, where every mile traveled isn’t just a journey—it’s a commitment to keeping the gears of the global economy turning. Sta... read more

- Excel Version – $129.95 Version 1.2

- PDF Version – $0.00 Version 1.2

Crypto Trading Platform – 5 Year Financial Model

Financial Model presenting an advanced 5-year financial plan of a Crypto Trading Platform allowing customers to trade cryptocurrencies or digital curr... read more

- Excel Financial Model – $139.00 Version 1

- PDF Free Demo – $0.00 Version 1

Truck Rental Company Financial Model

This detailed 10-year monthly Excel template is specifically designed to formulate a business plan for a Truck Rental Business. It employs a thorough ... read more

- Excel Version – $129.95 Version 2.3

- PDF Version – $0.00 Version 2.3

Kayak Boat Rental Business Model

Dive into the future of your kayak boat rental business with our cutting-edge 10-year monthly financial model, tailored to empower entrepreneurs and b... read more

- PDF Demo Version – $0.00 Version .5

Event Organizer Business Model Template

Elevate your event planning business to new heights with our state-of-the-art Event Organizer Business Financial Model Template in Excel. The Excel sp... read more

- Event Organizer Template - Full Excel – $129.95 Version 1.4

- Event Organizer Template PDF Demo – $0.00 Version 1.4

Gas / EV Charging Station 10-year Financial Forecasting Model

This model is adaptable and useful for a Gas Station, an EV Charging Station, or a combination of both types of Stations. The model is coherent, easy ... read more

- Full Open Excel – $50.00 Version 7

- PDF Preview – $0.00 Version 7

Gantt Chart Template: Intuitive and Innovative Planning Tool

Very simple to use, intuitive and innovative planning tool/Gantt Chart

- Gantt Chart Tool – $20.00 Version 1

Student Accommodation / Village Development Model – 20 years

This Student Accommodation 20-year Development Model (hold and lease) will produce 20 years of Three Statement Analysis, Re-valuations and the consequ... read more

- Excel Full Open – $50.00 Version 7

- PDF Explainer – $0.00 Version 7

Motorboat Rental Business Financial Model

Dive into the heart of financial planning with our Motorboat Rental Business Financial Model, designed to propel your venture into uncharted waters wi... read more

Webinar Organizer Business Plan Template

Discover the key to financial success in your webinar ventures with our Webinar Organizer Business Plan Template. This webinar business template is an... read more

- Excel Version – $129.95 Version 1.4

- PDF Version – $0.00 Version 1.4

Paddle Boat Rental Business Model

The Paddle Boat Rental Business Financial Model is a pivotal tool for entrepreneurs venturing into the leisure and tourism industry. Crafted with prec... read more

Party Planning Business Financial Model

Introducing the Party Planning Business Financial Model – Your Ultimate Tool for Flawless Financial Management in Event Planning! In a highly person... read more

- PDF Demo Version – $0.00 Version 1.4

Tennis Court and Club Development – 10-year Financial Forecasting Model

Introducing our Tennis Courts and Club Financial Forecasting Model – your winning strategy for tennis court and club development. With unmatched coh... read more

- Full Open Excel – $49.00 Version 8

- PDF Preview – $0.00 Version 8

Business Plan on Two Pages

Simple but effective business plan template - on two pages.

- Business Plan Template – $32.00 Version 1

Gym and Fitness Club 10 year Financial Forecasting Model

Introducing our indispensable 10-Year Excel Financial Forecasting Model, a vital asset for gym and fitness club owners navigating the complexities of ... read more

- Full Open Excel – $40.00 Version 8

- PDF Explainer – $0.00 Version 8

Squash Court and Club Dynamic Financial Model 10 years

Introducing our Squash Courts and Club Financial Forecasting Model – a game-changer for aspiring squash enthusiasts and club developers. With unpara... read more

- Free PDF Preview – $0.00 Version 8

Self-Storage Park Development Model

This Self-Storage Park development model will produce 20 years of three-statement analysis and valuations. There is a sheet focused on the Investor An... read more

- Free PDF Explainer – $0.00 Version 7

Three Statement Financial Model Template

The three statement financial model template offers a fundamental Excel template designed to project the three key financial statements over the next ... read more

- Free Excel Version – $0.00 Version 1.1

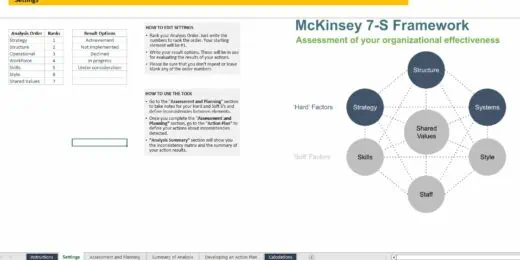

McKinsey 7S Model Excel Template

Originating in the late 1970s by consultants at McKinsey & Company, the McKinsey 7S framework is a strategic management tool designed to align sev... read more

- Excel Template – $39.00 Version 1

Surfboard Rental Business Financial Model

Surfing is not just a sport—it's a lifestyle booming globally. With eco-tourism on the rise and outdoor adventures in high demand, now's the time to... read more

- Excel Version – $129.95 Version 1.1

- PDF Version – $0.00 Version 1.1

Manpower Planning and Analysis Model

The Manpower Analysis Model was designed to equip HR managers and analysts with a tool to control the transition of a workforce from one year to anoth... read more

- Excel Model – $50.00 Version 7

- Model Manual – $0.00 Version 7

Brandy Distillery Business Financial Model

Discover the ultimate Brandy Distillery Business Financial Model, meticulously designed to provide 10-year comprehensive insights and strategies for y... read more

3-Statement Financial Model

3-year financial model that is specially designed for early-stage companies.

- 3-Statement-Excel-Model-with-5-year-Forecast.xlsx – $39.00 Version 1

E-Commerce Startup Company (5-year) Financial Forecast Model

By developing a detailed 5-year dynamic financial forecast model for a e-commerce startup, founders, investors, and stakeholders can gain insights int... read more

- Excel Model – $70.00 Version 1

- PDF Model – $0.00 Version 1

Cider Distillery Financial Model

With its longstanding tradition and swiftly growing global demand, the cider industry offers a lucrative opportunity for investors looking to tap into... read more

- PDF Version – $0.00 Version 5.5

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Investor Business Plan

- SBA Business Plan

- L1 Visa Business Plan

- E2 Visa Business Plan

- EB-5 Visa Business Plan

- Strategic Business Plan

- Franchise Business Plan

- Call our business plan experts:

- Schedule Free Consultation

What Are Appendices in a Business Plan? A Complete Guide

A comprehensive business plan is significant for all investors or business dreamers in the competitive business world. It serves as a roadmap to business success and gives entrepreneurs the right direction to follow at every critical stage of their venture. Similarly, one of the sections in a business plan has its place due to adding an essence to your plan. It is called “Appendices”. Do stick around to learn what are appendices in a business plan.

What are appendices in a business plan?