- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

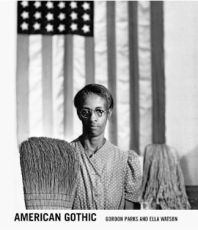

American Gothic

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- BBC - Culture - How American Gothic became an icon

- The Guardian - American Gothic: a state visit to Britain for the first couple

American Gothic , painting by Grant Wood completed in 1930.

Grant Wood, an artist from Iowa, was a member of the Regionalist movement in American art, which championed the solid rural values of central America against the complexities of European-influenced East Coast Modernism. Yet Wood’s most famous painting is artificially staged, complex, and ambivalent. Its most obvious inspiration is the work of Flemish artists such as Jan van Eyck that Wood had seen on visits to Europe, though it may also show an awareness of the contemporary German Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement.

“These are types of people I have known all my life. I tried to characterize them truthfully—to make them more like themselves than they were in actual life,” Grant Wood said about American Gothic .

Wood noticed the American Gothic–style white house, built in 1881 with its pinnacle and churchlike upper window, in the small town of Eldon, along the Des Moines River in southeastern Iowa. He used his sister Nan and his dentist, Dr. B.H. McKeeby, as models for the couple standing in front of it; each posed separately for Wood as he made his painting. The pitchfork—originally a rake in Wood’s sketches for the painting—suggests the man is a farmer, although whether this is a husband and wife or a father and daughter is unclear. They are a tight-lipped, buttoned-up couple. The farmer’s pose is defensive, the pitchfork planted as if to repel trespassers. The woman’s sideways glance is open to any reading. Both are posed to suggest the framing of a camera portrait for which neither subject is visibly enthusiastic. The posture of the couple also suggests the rigid countenances of Northern Renaissance portraiture. In any case, Wood intended them as archetypes , remarking, “These are types of people I have known all my life. I tried to characterize them truthfully—to make them more like themselves than they were in actual life.”

Superficially simple and naive, American Gothic is rich in visual puns and echoes—for example between the pitchfork and the bib of the farmer’s overalls, and the pinnacle on the house visually repeating the church spire in the far distance. Wood includes tiny details that draw interest: there are seven trees behind the balloon-frame house, suggestive of the seven trees of Isaiah 41:19; the woman wears a dress with a near-clerical collar; the unfaded calico drapes in the windows point to both orderliness, undone a touch by the loose strands of hair on the woman’s nape, and a certain degree of prosperity. Wood consistently rejected suggestions that the painting was a satire of the Midwest and its conservative values. Instead, with the three-tined pitchfork being read as meant to evoke the Christian trinity, the painting is perhaps better read as a paean to rural Protestant earnestness, humorless and hardworking, ever with an eye to salvation through one’s work and works.

An icon of American popular culture , the American Gothic trope lent itself to many parodies in popular culture. The painting is ambiguous and open to interpretation on many lines, and so is a favourite of curricula in art history and art appreciation. The painting is housed at the Art Institute of Chicago , where it is among the most visited works of art on exhibit.

Analisis of work “American Gothic” Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

“American Gothic” is a painting by Grant Wood in 1930. The image is iconic at this stage in American history, depicting the image of a stern-faced man holding a pitchfork and a younger woman both standing in front of a white farmhouse. According to reports, the artist was inspired to create the painting when he saw the farmhouse from the window of a car in his home state of Iowa. “He decided to paint the house – built in the ‘carpenter gothic’ style, which applied the lofty architecture of European cathedrals to flimsy American frame houses – along with ‘the kind of people I fancied should live in that house” (Fineman, 2005).

The image has made significant transitions in the way in which it has been interpreted over the years, largely due to the way in which people have approached it. Although the picture is widely considered to be the picture of the ultimate example of a Midwestern farmer and his wife, there are conflicting reports that Wood intended to represent a farmer and his wife. While Fineman suggests that this interpretation was offered by Wood’s sister Nan, who posed for the female character and was perhaps embarrassed by the prospect that she would be married to a man obviously so much older than she, the true nature of this relationship is actually not as important as the individual viewer’s interpretation.

Although we may be told what a particular painting is supposed to mean, ultimately, it is up to the individual to determine what the piece means to them in particular. As John Armstrong says, “however crowded the gallery, an encounter with a work of art is always something we pursue alone – no one else can make the work matter to us. When contemplating a work of art, one of the key questions ought to be ‘what is this to me?” (Armstrong, 2000: 4-5).

The reception of this piece of art illustrates the degree of difference in perspectives a different set of eyes can introduce to the work. According to Fineman (2005), Wood entered the painting in a competition at the Art Institute of Chicago where most of the judges considered it trivial and meaningless, but one patron of the museum saw something more important. It was thanks to this patron that the work received the bronze award along with a small cash prize and that the museum acquired the piece itself. When images of the painting finally reached Iowa, the response was largely negative as Wood’s fellow Iowans were dismayed at the way in which he portrayed them, as if they were always “grim-faced, puritanical Bible-thumpers” (Fineman, 2005).

More sophisticated assessments of the painting held that it was a brilliant satire of the “rigidity of American rural or small-town life” (Fineman, 2005). Wood himself carefully fostered new ways of thinking about the painting as it became more emblematic of “American virtue and the pioneer spirit” (Fineman, 2005). Looking at the painting, all of these various interpretations are certainly justifiable and, when one is looking at the painting with these ideas in mind, it is possible to trace their origins.

However, none of these interpretations convey any true meaning to the individual unless one considers what the painting means to them. For me, the painting is representative of the restrictive ways of life of the past as fathers stood jealous guard over their daughters, often to the daughter’s detriment. While attempting to view the image as one of a farmer and his wife, I noticed that the eyes of the younger woman are looking in the direction of the man but seem to see well beyond him, as if she longed to be able to explore what she might find beyond the trees, which are hinted at in the background.

Although she is dressed very conservatively, a wisp of hair falling from her bun and the sad, slightly cross look on her face indicates to me a sense of wishing she had more options in her attire and self-expression. They are obviously posing for a picture, as seen in the man’s direct gaze at the painter, but the woman stays distracted, a step behind the man and seeming as if she would run if she thought she had a chance.

This chance is removed from her by the barbed points of the man’s pitchfork which are repeated throughout the painting as if the girl is surrounded by pitchforks that threaten harm if she steps outside her bounds. At the same time, they ensure no one enters the space the man has defined as his territory, including the space of the woman’s social world. Whether she is daughter or wife, therefore, makes very little difference. Either way, she is trapped in a world not necessarily of her own choosing and obviously longs for something else.

While a number of interpretations have been offered on this image in a variety of ways and in numerous different social periods, these can only help to inform a personal opinion about the painting rather than take the place of this personal opinion. Painting means nothing if it does not mean something to the individual viewing the piece and this requires a close examination of the image in order to fully appreciate it.

While it has been argued that the woman is the daughter rather than the wife of the farmer, in my personal exploration of the piece, I have determined that her status really doesn’t matter to the meaning of the piece. Instead, to me, the image depicts the rigid social constraints women often found themselves in even in the early 1900s. Despite living in the free world, these women were not free, often living behind metaphorical pitchforks that governed their actions, their dress and their behavior, but could not control their inner desires or dreams.

Works Cited

Armstrong, John. Move Closer: An Intimate Philosophy of Art. New York: Farrar, Straus Girous, 2000.

Fineman, Mia. “The Most Famous Farm Couple in the World.” Slate. (2005). Web.

- "Water Strider" by Michael Heizer

- Image and Meaning, Symbolism, Myths, Ideology

- Review of "Christina's World" Paintings

- Investigation of One of the States of the United States. -Iowa

- Graphic Violence in Movies

- Chinese Culture: Chinese Calligraphy Art

- Ron Meuck's Postmodern Artworks

- Vincent van Gogh’s "Starry Night"

- The Language of Graphics and Visual Art

- "The Shadows of Katrina" by Machyar Gleunta

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, November 18). Analisis of work "American Gothic". https://ivypanda.com/essays/analisis-of-work-american-gothic/

"Analisis of work "American Gothic"." IvyPanda , 18 Nov. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/analisis-of-work-american-gothic/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Analisis of work "American Gothic"'. 18 November.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Analisis of work "American Gothic"." November 18, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/analisis-of-work-american-gothic/.

1. IvyPanda . "Analisis of work "American Gothic"." November 18, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/analisis-of-work-american-gothic/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Analisis of work "American Gothic"." November 18, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/analisis-of-work-american-gothic/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

The reality behind American Gothic

By Sarah Churchwell

Published on 16 February 2017

As ‘America after the Fall’ brings some of the country’s most iconic works to Europe for the first time, Sarah Churchwell considers the cultural and political backdrop to Depression Era art.

From the Spring 2017 issue of RA Magazine , issued quarterly to Friends of the RA .

A farmer stands ramrod straight, holding a three-pronged pitchfork and wearing bib overalls under a crumpled black jacket grown rusty with age. The pale blue Iowa sky is slightly less flinty than his expression. On his right stands a woman whom many take for his wife, but was intended by the artist to be his daughter. Her mouth seems similarly uncompromising, as is the blonde hair scraped back from her face. A straggling lock of hair, liberated by work, softens her expression; a closer look at her eyes reveals the worry.

Together, the couple below appear singularly grim. Behind them is a cream farmhouse with a window-blind on the upper floor flocked by the same pattern covering the woman’s simple brown dress. The window frame is Gothic, and many observers assume that it alone gives the painting its name. But the couple’s old-fashioned dress, demeanour and agrarian setting would also have been deemed figuratively "gothic" when the picture was painted, much as any old-fashioned style might be called "medieval". To be an American yeoman farmer while the rest of the nation extolled the modern was to belong to the dark ages.

American Gothic , painted in 1930 by Iowa native Grant Wood, is probably the most famous American painting in the world. If any artworks merit that overworked adjective "iconic", this is one of them. The contrast between modernity and archaism registers even in the picture’s Flemish style, which was also once called "Gothic". Wood employed the techniques of the so-called "primitives of Flanders" – whose 15th and early 16th-century works were later referred to as "Gothic painting" – to suggest his couple’s anachronistic qualities. Among other historical ironies that Wood’s juxtaposition creates, it captures the moment when Iowa, once a radical state dedicated to the fight against slavery (an all-but forgotten history that is the subject of Marilynne Robinson’s 2004 Pulitzer Prizewinning novel Gilead ), had become a byword for white rural conservatism.

The painting was immediately exhibited, and then purchased, by the Art Institute of Chicago , where it has hung ever since. Almost a century later, thanks to the exhibition America after the Fall it has made its first voyage to Europe, arriving in Paris at the Musée de l’Orangerie last autumn before making its way to the RA this spring. There is something ironically fitting about this, the rural Iowa couple clinging to outmoded values who finally leave the American heartland, at the age of nearly 90, to discover the world, rather as if American Gothic just got a passport.

For me, seeing this painting come to Europe for the first time is a decidedly uncanny experience, as it is one of the first famous pictures I remember seeing, and the one I most associate with home. I grew up in Chicago, and spent much of my adolescence wandering the grand corridors of the Art Institute, where I always took a swing by to look at American Gothic , enjoying the frisson of seeing in "real life" a picture so familiar from its endless reproductions and iterations. It’s such a stock image that I couldn’t possibly say when I first encountered it, but I vividly remember the excitement of seeing the original, when I was about ten. Many years later, I would read Walter Benjamin’s influential 1936 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction , which argues that reproducing art makes it democratically accessible, thus decreasing the mystical sense of "aura" surrounding an artwork. That said, it is also true that reproduction can increase the sense of aura around an original: the more an image is reproduced, the more exclusive its original seems. There is nothing so original as that which has been endlessly copied.

America after the Fall consists of 45 American artworks from between 1929, when Wall Street crashed, and 1941, when the United States entered the Second World War. This is the art of the Great Depression, and it is depressing indeed to note how relevant its themes have become. It was the most severe economic downturn of any Western country in modern history; in 1933, the worst year of the Depression, US unemployment hit 25 per cent and nearly half the nation’s banks had failed. International trade declined during the period by half, while farmers were especially hard hit, as crop prices in America fell by as much as 60 per cent. These economic conditions were exacerbated by a devastating drought and winds that hit the Great Plains in waves during the 1930s, creating the "Dust Bowl" that destroyed the livelihoods of millions of farmers. Meanwhile, as the show’s excellent exhibition catalogue notes, the US population doubled between 1890 and 1930, largely because of immigration: by the 1929 Crash, one in every ten Americans was an immigrant or born to immigrants. During a time of intense social anxiety and unrest, a sense emerged that art might be reparative, rather than consolatory, that it could take part in social protest, but also contribute to a democratic celebration of communities and bridge-building.

Some of the most familiar names, and pictures, of the period are represented in the exhibition: several major works by Grant Wood, Edward Hopper, Reginald Marsh and Thomas Hart Benton, as well as a very early Jackson Pollock and a Georgia O’Keeffe ( Cow’s Skull with Calico Roses , 1931).

Late in life, O’Keeffe wrote: "Where I was born and where and how I have lived is unimportant. It is what I have done with where I have been that should be of interest." This admonition is worth considering more closely. O’Keeffe does not insist only that what she has done should be of interest, but rather, what she has done with where she has been. Context and environment are part of interpretation – O’Keeffe didn’t want her work to be dislocated from its origins. "Where I have been" may mean the literal physical settings from which O’Keeffe and some of her contemporaries drew inspiration, in her case especially the majestic landscapes of the American southwest; but it may also figuratively denote the emotional, psychic or personal journeys that are also a matter of where artists, or their societies, have been. The question, as O’Keeffe notes, is what we have done with where we have been.

A widespread sense that the national iconography needed to be reclaimed and reimagined took hold of artists and thinkers across the country

Sarah Churchwell

Georgia O’Keeffe image

Cow’s skull with calico roses, 1931.

Alexandre Hogue image

Erosion no. 2 – mother earth laid bare, 1936.

Grant Wood image

Daughters of revolution, 1932.

This is an exhibition about what American artists did with where they had been: it is about context – historical, cultural, geographical, political – and it brings that context to life with great elegance and economy. It is an exhibition in active dialogue with modern American history.

In his 1918 essay On Creating a Usable Past , the American critic Van Wyck Brooks argued that America should view its past not from the perspective "of the successful fact but of the creative impulse". For Brooks and his colleagues in the Seven Arts movement, this was an American project, a nation’s encounter with its spiritual heritage. Lewis Mumford later wrote that artists and writers in the 1920s were the "scouts and prospectors in a new enterprise, the bringing to the surface of America’s buried cultural past."

By 1930, this influential lesson had been absorbed by painters like Grant Wood, whose Daughters of Revolution (1932, above) is a commentary on the historical irony of reactionary genealogical societies creating aristocracies out of revolution. Three prim, old, white women stand in old-fashioned dress, their expressions exuding self-satisfaction and superiority. They are positioned in front of a representation of Emanuel Leutze’s famous historical painting Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851); the revolutionaries’ radicalism and daring is counterpointed, pointedly, against the women’s conservative complacency, but Wood is also implicitly attacking the hypocrisies embedded in American mythologies. One of the women is holding an heirloom tea cup, drinking tea instead of dumping it in Boston Harbour, while all of the women would have despised the German-born immigrant Leutze, despite revering his painting. Wood slyly implies the Anglo-Saxon racial superiority being celebrated: "I don’t like to have anyone try to set up an aristocracy of birth in a Republic," he declared, calling the women three "tory gals". Similarly, American Gothic was an ironic commentary on the state of the Jeffersonian agrarian idyll during the onset of the Great Depression, a moment when many American artists and critics were declaring, flatly, that the American experiment had failed.

It was in 1931 that the phrase "American Dream" was first coined as a way to describe the American experiment, its hope that the nation might create a land of opportunity and promise for all, in a book called The Epic of America . Its author, James Truslow Adams, like so many Americans, was seeking to explain the failures of the nation, how it could have been brought so low. He argued that the country had lost sight of its values by merely chasing material prosperity, whereas the American Dream was properly a dream of a higher purpose, a spiritual vision of a nation in which humanity could better itself. The phrase instantly caught America’s imagination, appearing throughout the decade in debates and discussions about how the country could right its course. That sense of dreams and nightmares, of surrealism and the uncanny, of history recurring in a mythopoeic landscape, would recur throughout the art of the period as well. A widespread sense that the national iconography needed to be reclaimed and reimagined took hold of artists and thinkers across the country, as people began to question what the American Dream might mean in reality. They did not ask, as we have done during our own downturn, why the American Dream had failed; they thought they had failed, and wondered if the nation might be saved by an American Dream of a higher purpose than merely creating material prosperity.

Confronted with the stark failure of unregulated capitalism, America began in the 1930s seriously to consider socialism and communism for the only time in its history. American artists in particular were attracted to the promises of an entirely new social and political system, given the manifest failures of the old ones. The so-called Popular Front and the WPA – the Works Progress Administration – both sought to put artists to work creating explicitly political art, even propaganda. The government encouraged artists to discover, or create, an "American Scene" that addressed native arts and culture. They were seeking great statements of American public life, history and identity that would uplift the people and help revitalise and regenerate American society; the Public Works of Art Project particularly emphasised uplifting treatments of local places and the common people.

That sense of dreams and nightmares, of surrealism and the uncanny, of history recurring in a mythopoeic landscape, would recur.

The immense American murals of the 1930s, like those of Thomas Hart Benton, with their markedly Soviet-agitprop style, still grace some of America’s most important public buildings, including several state capitals and a great many post offices. Benton, one of the best-known public muralists, set the standard for WPA projects with America Today for New York’s New School for Social Research, which was commissioned in 1930 and is now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The scale of such art reflected a prevailing sense that monuments were required that might create a national, public or collective sense of identity.

An aesthetic debate developed between the advocates of realism as specifically and rootedly American, and abstraction as a universal language that might transcend nationalism: the mimetic social realism of the WPA murals turned toward an allegorical vision of history. Allegory was also put to the work of political and social protest by painters such as Alexandre Hogue. In Erosion No. 2 – Mother Earth Laid Bare (1936, above), Hogue painted an allegory of the terrible droughts of the mid-1930s in which farmland is depicted in the form of a nude woman’s body exposed by erosion.

In Aspiration (1936, below), Aaron Douglas encapsulates the progress of African Americans rising up from slavery by depicting dark figures in chains at the bottom of the image, with large silhouetted figures rising up from them holding symbols of knowledge and labour, bathed in violet light, pointing towards a futuristic city on a hill. Joe Jones likened his painting American Justice (1933) to a Renaissance crucifixion scene: a young black woman, her white dress torn from her bare breasts, lies in the foreground, a rope hanging ominously behind her, while white costumed members of the Ku Klux Klan burn a small house in the background.

The Harlem Renaissance, with its celebration of African American music, art, literature and history, was in full force, as paintings such as William H. Johnson’s vibrantly coloured Street Life, Harlem (1939) and Arthur Dove’s Swing Music (Louis Armstrong) (1938, below) suggest, while the latter also reflects the rising force of abstraction, its irregular shapes in varying reds and yellows against a deep black background evoking "red hot" jazz in a darkened space. Charles Green Shaw’s Wrigley’s (1937, below) prefigures Pop Art, fusing Abstract Expressionism and advertising iconography, as if a pack of gum had zoomed into an early Rothko.

Aaron Douglas image

Aspiration, 1936.

Charles Green Shaw image

Wrigley’s, 1937.

Arthur Dove image

Swing music (louis armstrong), 1938.

Less playfully and more mimetically, Edward Hopper was painting scenes of urban desolation, capturing the disappointment and deflated hopes of ordinary Americans during the Depression. Hopper’s vision of urban realism is not one of shiny new skyscrapers of geometric modernist abstraction, its dreams of Futurist utopias, but older, wearied, worn-out looking individuals and isolated buildings. His places are sparsely populated, full of voids and dark spaces, as if people are leaving a city about to be blighted. Hopper’s most famous painting, Nighthawks , which also hangs at the Art Institute of Chicago, was painted in 1942, just beyond the dates of this exhibition. But two of Hopper’s paintings are represented at the RA show, including Gas (1940), with its red fuel-pumps standing alone in the country landscape as if inspired by a line from The Great Gatsby : "Already it was deep summer on roadhouse roofs and in front of wayside garages, where new red gas-pumps sat out in pools of light." Hopper’s shiny streamlined gas-pumps stand in stark contrast to the dark, undulating trees and hills behind them, the isolated attendant alone in a vast landscape.

The second Hopper painting included in the show is the marvellous New York Movie (1939, below), which are placed in tacit discussion with two cityscapes by Reginald Marsh, whose highly populated canvases conjure the bustle and noise of urban existence. By no coincidence, both painters were interested in the movies as a symbol of modern life.

Hopper’s New York Movie emphasises the loneliness and longing of movie-goers. In a half-empty movie theatre a fraction of the silver screen can be glimpsed in the upper left corner, while off to the right, in the golden glow of lamplight, an usherette stands alone, lost in thought. As the catalogue notes, the screen shows "snowy mountain tops" perhaps intended to evoke the hit film Lost Horizon (1937), a story of paradise found and lost. In his scene outside a cinema, Twenty Cent Movie (1936), Marsh similarly suggests the role that movies played in shaping ordinary Americans’ aspirations and dreams, while ironically underscoring the contrast between their lives and the fairy-tale images of Hollywood. While the gaudy background colours of the advertisements and movie posters promise the "joys of the flesh", the movie-goers self-consciously pose, imitating their favourite stars, but do not interact.

Hollywood offered escapism into fantasies of all varieties, as the canvases of Hopper and Marsh suggest, including fantasies of history. The curators at L’Orangerie decided to close their version of the exhibition with a montage of Depression Era film, which worked strikingly well in dialogue with the show. Perhaps no more notoriously nostalgic movie has ever been made than that of Gone with the Wind in 1939, a few scenes from which were included in the Paris show. But the producers of Gone with the Wind were also creating a "usable past", one that spoke to audiences in 1939. As the iconic and climactic scene of Scarlett O’Hara vowing that she’ll never be hungry again suggests, the movie resonated with Depression Era audiences because of what it said about their experiences: it is about fighting for survival. The story certainly offered consoling lies about the antebellum South, but it also told current truths about hunger and endurance in the 1930s.

The cinema montage in the show also included the iconic Art Deco Emerald City in The Wizard of Oz (1939); Fred Astaire in discomfiting minstrelsy black-face, tap-dancing in Swing Time (1936); a homage to modernist technology as Carole Lombard excitedly takes her first plane trip in the earliest Technicolor movie, the hilariously cynical Nothing Sacred (1937) (also an edgy clip for the curators to choose, given that Lombard would tragically die in a plane crash while selling war bonds in 1942); and James Stewart demanding that the American government live up to its democratic values in Mr Smith Goes to Washington (1939), a scene clearly chosen for its tacit commentary on the state of American politics now. Hollywood was central to the story of American life the exhibition is telling, and visitors may well want to explore some of these films from the era as well.

In 1934, F. Scott Fitzgerald published Tender is the Night . The novel begins just before the Wall Street Crash, with a young movie star Rosemary Hoyt, symbolising American innocence, who still has her very American "bouncing, breathless and exigent idealism". By the end of the novel, she, like her country, has lost her idealism, but not her stardom. The allure of American dreams remains powerful, even when they become more mature, darker and more cynical. The uses of history, art, allegory and mythmaking in nation-building are clear, but they’re also useful when rebuilding a nation. When America hit rock bottom, its artists helped it reimagine itself. After the fall, there are lessons to be learned about how to get back up.

Sarah Churchwell is Professorial Fellow of American Literature at the University of London, and author of Careless People: Murder, Mayhem and the Invention of The Great Gatsby (Virago) .

America After the Fall: Painting in the 1930s , The Sackler Wing, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 25 February – 4 June 2017.

Events Grant Wood’s ‘American Gothic’, unvarnished with R. Tripp Evans, Friday 17 March, Royal Academy of Arts. The art of the American dream with Sarah Churchwell, Monday 27 March, Royal Academy of Arts.

Exhibition organised by the Art Institute of Chicago in collaboration with the Royal Academy of Arts, London and Établissement public du musée d'Orsay et du musée de l'Orangerie, Paris

Enjoyed this article?

As well as free entry to all of our exhibitions, Friends of the RA enjoy one of Britain’s most respected art magazines, delivered directly to your door. Why not join the club?

Related articles

Michael Craig-Martin: living colour

28 August 2024

Visions from Ukraine

19 June 2024

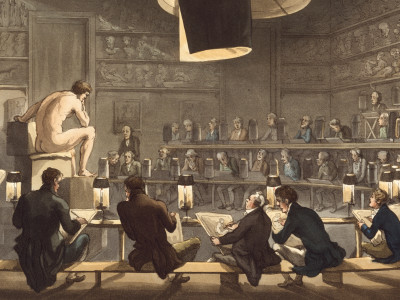

10 RA Schools stories through the centuries

16 May 2024

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction

- > The rise of American Gothic

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The genesis of “Gothic” fiction

- 3 The 1790s

- 4 French and German Gothic

- 5 Gothic fictions and Romantic writing in Britain

- 6 Scottish and Irish Gothic

- 7 English Gothic theatre

- 8 The Victorian Gothic in English novels and stories, 1830-1880

- 9 The rise of American Gothic

- 10 British Gothic fiction, 1885-1930

- 11 The Gothic on screen

- 12 Colonial and postcolonial Gothic

- 13 The contemporary Gothic

- 14 Aftergothic

- Guide to further reading

- Filmography

- Series list

9 - The rise of American Gothic

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 May 2006

From the turn of the eighteenth into the nineteenth century and the beginnings of a distinctive American literature, the Gothic has stubbornly flourished in the United States. Its cultural role, though, has been entirely paradoxical: an optimistic country founded upon the Enlightenment principles of liberty and “the pursuit of happiness,” a country that supposedly repudiated the burden of history and its irrational claims, has produced a strain of literature that is haunted by an insistent, undead past and fascinated by the strange beauty of sorrow. How can the strikingly ironic, even perverse, career of the Gothic in America be accounted for? Why has it been so at home on such inhospitable ground?

The most common responses to these questions have recourse to conventional metaphors: the Gothic, it is frequently reasoned, embodies and gives voice to the dark nightmare that is the underside of “the American dream.” This formulation is true up to a point, for it reveals the limitations of American faith in social and material progress. Yet a simple opposition between the convenient figures of dream and nightmare is overly reductive. These clichés, and the impulses in American life that they represent, are not in mere opposition; they actually interfuse and interact with each other. This realization will take us far in understanding the odd centrality of Gothic cultural production in the United States, where the past constantly inhabits the present, where progress generates an almost unbearable anxiety about its costs, and where an insatiable appetite for spectacles of grotesque violence is part of the texture of everyday reality.

Access options

Save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- The rise of American Gothic

- By Eric Savoy

- Edited by Jerrold E. Hogle , University of Arizona

- Book: The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction

- Online publication: 28 May 2006

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CCOL0521791243.009

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Formal Analysis on American Gothic, Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 1052

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Grant Wood’s American Gothic (1930)

This painting is probably America’s most recognizable one, known even to those who do not know its age, locale, title, or name of its painter. Its worldwide fame is on par with that of the Mona Lisa and The Scream. Like those latter two iconic works, American Gothic has been endlessly copied, parodied, and interpreted over the years. Grant himself was ambivalent on what it meant, if anything. Initially some Iowans (the painting’s locale) hated it and Wood both.

Being a portrait, it has an entirely different look from the hyper-rounded, almost cartoonish appearance of Wood’s landscapes, some of which look like they could almost have been done by Thomas Hart Benton in a mellow mood. There is nothing outwardly exaggerated about the farmer and his wife (or daughter — the relationship is unaddressed), nor the house behind them. (However, a photo of the pair in modern dress taken some time after the picture was taken shows that the woman’s face in the painting is much narrower than the actual model’s. The man’s face, by contrast, is virtually a photographic likeness.) The other elements — its composition, line, space, light, color, and overall impression are organized, tight, and terse — and almost entirely a depression-era plains derivative (called Carpenter Gothic) of the Northern Renaissance, particularly the Flemish school. Grant studied that branch extensively during his early trips to Europe, and basing American Gothic on that artistic template necessarily limited his options. But this was not a problem. The arched window at the center of the picture, above and behind the couple, is the inspiration for the entire painting. It provides its focal point and title, the latter because its design is clearly derived from classic European Gothic-era Church windows (Douglas, 2011). There is nothing else remarkable about the building. The window is everything.

Wood saw that window from his car one day, and was struck by it. He thought it somewhat pretentious, yet artistically affecting. Next he thought of who would likely inhabit the house. And these are the three fundamental elements the picture is built from. In other words, it’s a triptych, a Renaissance staple of European art, updated and transplanted with a wry but serious twist to the American Midwest. However, the window is not realistic in the sense of reporting exactly what the painter saw: it’s actually noticeably wider than its painted version. That artistic narrowness is also central to the picture. It is reinforced by the vertical slat-construction showing on both floors of the house and red barn, as well in the subtle but emphatic narrowness of the man and woman. She shows sloping shoulders, flat chest, a long neck, narrow face, and hair pulled back tightly around it. The man’s head is, if anything, even narrower, so much so that it counters the effect of his rectangular shoulders. The final emphasis on narrowness is the weird mirroring of the man’s pitchfork (which itself echoes the triptych) on his bib overall and shirt. All this is obvious, as what it all connotates: the couple were as narrow-minded as their faces.

Whatever more that narrowness was actually meant to convey (if anything), the colors used are another expression of that design and sentiment. The only pronounced ones are dark — either black or brown — and white. I think this harkens back to the Northern Renaissance effect as well, and in this particular painting he achieves a typical supporting effect by putting the darker colors well in front of the contrasting pale blue sky. Some commentators have also noted the corpse-like look of the man. Whether that was deliberate or not, the combined effect of the two dour faces in dark and old fashioned clothing (the woman’s rickrack was already old-fashioned) does lend a funeral sense to the picture; the man’s black coat indicates he is a minister of the local church; the woman looks turned away, as if in grief; and the shaded windows in day was a mourning tradition. But as for their faces, Grant may simply have been mimicking 19 th century photographs, where long exposure required people to stand perfectly still and maintain the same expression — that being the commonly given reason as to why few of the subjects ever smiled. (However, in Wood’s other portraits, almost none of the subjects smile.)

Once Wood saw the window, he had a difficult choice to make: how many people to put in the picture. It seems obvious now, but a look at Grant’s other portraits, both before and after this one, show that he preferred to paint a single person. Woman with Plants (1929) is a close precursor to American Gothic (the woman even wears a cameo), but it is unknown to the public. Having decided on a presumably married couple (and there is no reason to think of them as other than married), next came the choice of how to place the couple — which on the left and the right? If we assume the man to be right-handed, then had he been on the left (looking at the picture), he would have had to hold the pitchfork in his left hand to keep the pitchfork in the center of the picture, which is probably a design imperative. Interestingly, during traditional weddings, the groom is on right (looking at them from behind as they stand facing the minister) in order to keep his right “sword hand” free to fight off enemies (Stritof). In this picture, then, the pitchfork is in the man’s sword hand. Had Grant composed the picture with the man on the left side and holding the pitchfork in his left hand, we may be sure it would be resulted in a good deal of earnest interpretation and endless questions about it.

There has been a good deal of earnest interpretation and endless questions anyway. But that is probably the fate of all great art when it is seen by thousands, then (in modern times) millions. This increases with longevity of relevance. American Gothic has it. This is the central fact of a great work of art: it simply is. No one really knows why . It keeps its secrets from us.

Works Cited

Douglas, Chad. Connect Tristates. Trip to American Gothic House . 2011.Web.

Stritof, Sheri. About.com. Marriage: Groom on the Right, Bride on the Left . 2012. Web.

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Theism Versus Atheism, Essay Example

Abnormal Psychology: Schizophrenia, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

Join our Mailing List

The American Gothic

- June 4, 2018

- 18th Century , 19th Century , 20th Century , Collection Essays

Introduction

Ever read a strange book or watch a scary film, and feel the hairs on your arms stand on end? Ever get the “chills” encountering a creepy story, or have a hard-to-pin-down, icky feeling while standing in a cemetery or house that feels “haunted”? Have you ever had a funny feeling, but can’t quite put your finger on what it is that’s actually bothering you?

Those feelings are intrinsic to the experience of reading Gothic literature. Many authors of Gothic literature capitalized on those creepy feelings in order to usher in a new literary experience for readers. Broadly conceived, the Gothic is a sub-category of the Romantic genre including poetry, short stories, or novels designed to thrill readers by providing mystery and blood-curdling accounts of villainy, murder, and the supernatural. Common characteristics of classic Gothic literature include: wild and desolate landscapes; ancient buildings (ruined mansions, monasteries, etc.); castles and dungeons; secret doors and winding stairways; and apparitions and phantoms (“Literary Terms and Definitions”). J. A. Cuddon aptly describes one important quality of the Gothic: “an atmosphere of brooding gloom” ( Dictionary of Literary Terms , 381-82). While many Gothic texts include seemingly impossible scenarios and otherworldly events, the biggest, and most effective, thrill of the Gothic is how it taps into the essential terrors of human experience, hidden fears and desires, and the hauntings of the historical past. Narratives about crumbling castles and damsels in distress may not be in style anymore, but many characteristics of the Gothic prevail today in popular culture—ranging from the Harry Potter series, to noir films, to the Twilight franchise.

For the purposes of introducing and studying the Gothic in the classroom, however, one important characteristic is the particular role the genre plays in American literature, history, and culture. The American Gothic can be approached as a cultural lens, through which we can examine the social, political, and aesthetic investments of a particular historical period.

Gothic literature has a long, complex, and multi-layered history. In many ways, the Gothic genre invites many larger questions about the literary field, including—but not limited to—the ideas of how and when literary “canons” are formed, by whom, and under what conditions. As with any genre, the frameworks of the Gothic can be studied, as well as disrupted. For instance, how would our perspective on the American Gothic change in the context of transatlantic (Henry James), postcolonial (Jean Rhys), or North American (Angela Carter, Margaret Atwood) perspectives? While this essay focuses on writers often taught in American literature classrooms, it is necessary to recognize—and even challenge—the categories that have organized how we read and teach literature in the classroom.

Finally, this collection approaches the American Gothic literary text is a cultural and social object; in other words, not only does it convey important material in the writing itself, as it pertains to conventions related to the language (plot, underlying symbolism and messages, staging a critique, calling attention to a social problem, etc.). As a physical object, an American Gothic text also performs important cultural work. Through observing and analyzing its paratextual qualities (qualities of the text other than the written language, including its physical appearance, circumstances of publication, book sales, circulation, etc.), we can encounter, first-hand, the ways in which an American Gothic text functions as a historical and cultural artifact.

This Digital Collections in the Classroom essay gives a taste of the vast array of items found in The Newberry Library’s collection pertaining to the foundations of Gothic literature, as well as its particular flavor in American literary culture.

Essential Questions:

- What are some characteristics of the Gothic genre? The American Gothic genre?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of working within a literary genre?

- How does the American Gothic genre reflect historical, political, and cultural concerns of the time?

- Was there a time in your life when you felt that “creepy” feeling often associated with Gothic themes? Write a short story in response to that experience.

The Foundations of Gothic Literature

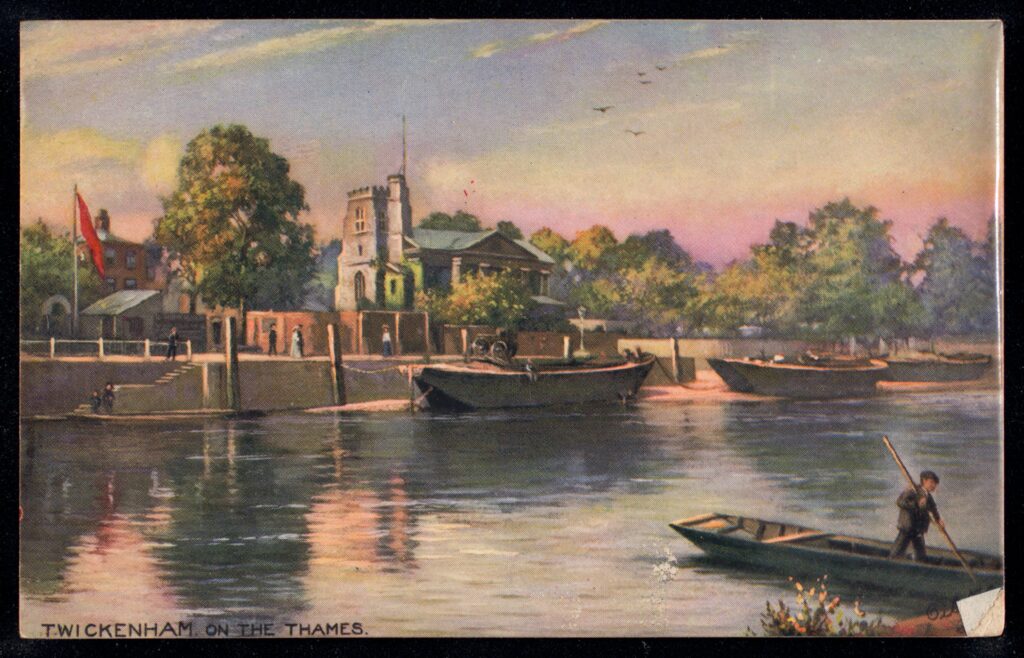

In order to study the American Gothic, it is important to understand its original foundations, found in the eighteenth century. While “spooky” things have certainly always existed, those who study the Gothic literary tradition identify its beginnings with Horace Walpole, a British art historian, writer, and politician. In 1749, motivated by his own fascination with medieval history and artifacts, Walpole built Strawberry Hill House, a Gothic villa in Twickenham, a neighborhood in southwest London. This series of turreted, castle-like buildings departed from the classical architecture popular in the 18th century, and helped bring Gothic revival architecture to public’s imagination. It also became closely connected to the Gothic literary movement.

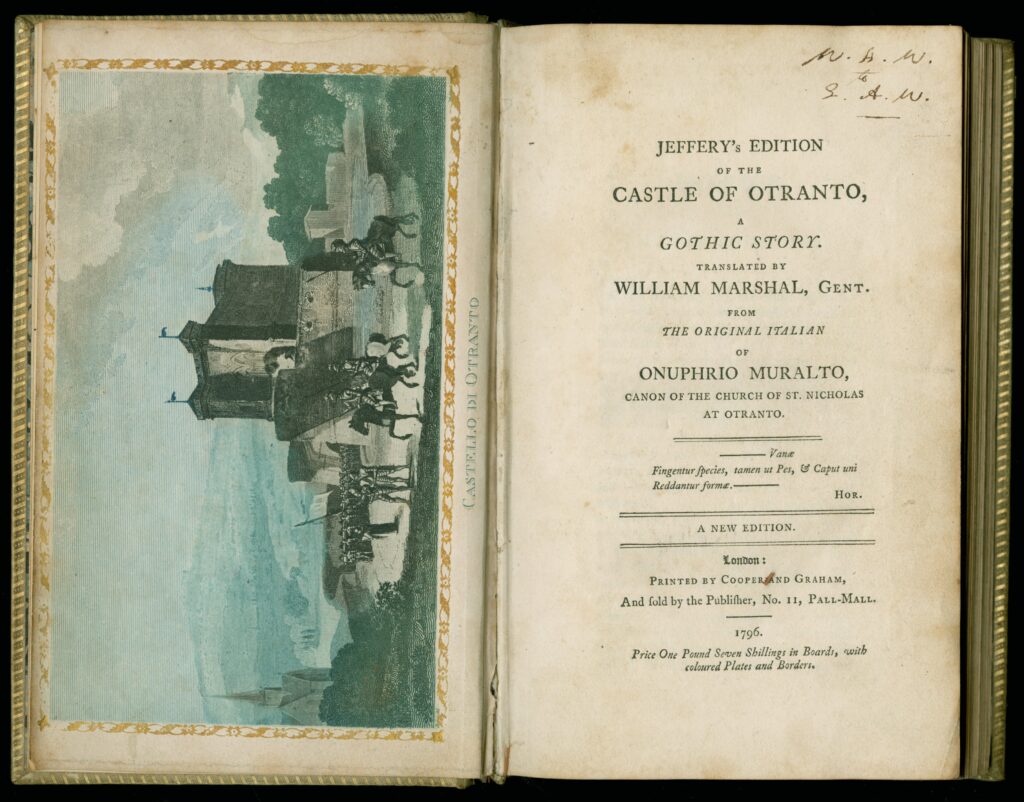

His aesthetic interest filtered into his life as an author, as well. Walpole wrote the book The Castle of Otranto (under the pseudonym “William Marshal”) while a member of British Parliament for the Whig Party in 1764. It is deemed among scholars to be the first supernatural novel, as well as a mixture of old and new themes—with “real people” in ordinary life experiencing otherworldly, extraordinary situations that are difficult to rationalize and explain.

In the first edition, Walpole claimed that the story was a translation of an original Italian manuscript from 1529 by “Onuphrio Muralto.” It was only until the publication of the second edition of the book that he admitted himself as the author. One possible reason for not admitting full authorship of the story would be to distance himself from sensational fiction, which was a controversial literary genre in the eighteenth century. The idea of discovering a manuscript would, therefore, makes the circumstances surrounding the story seem more historical than fantastical. (Undoubtedly, as an art historian, Walpole had the theme of history at the front of his mind.) However, another motivation for Walpole’s denial could relate to the idea of deflecting authorial responsibility for the story, as he claims himself a mere “translator” of another writer’s narrative. Additionally, the idea of a 16th-century manuscript heightens the exotic narrative of Otranto , staging it in an otherworldly place (Italy) as well as another time, “long ago.” These otherworldly characteristics contribute to the effect of the Gothic as displacing the reader from “normal life” into another setting, in which the supernatural reigns.

The story of The Castle of Otranto is a long and convoluted one. It focuses on a man named Manfred, whose son, Conrad, dies before his wedding to the princess Isabella. Anxious about continuing the family line, Manfred marries Isabella after divorcing his wife. As his plans become increasingly evil, the castle becomes haunted. Aside from centering on Manfred’s concern about continuing the family line, the story features many supernatural occurrences, portraits that come to life and walk around, trapdoors and secret passageways, and doors that open without warning.

Walpole’s novel was an immediate success, and inspired other authors to write their own Gothic stories, including Clara Reeve’s The Old English Baron (1778) and M.G. Lewis’s The Monk (1796).

Questions to Consider:

- What are some examples of the story line of The Castle of Otranto that combine the hard-to-explain with the real and explainable?

- What do you believe is the main reason Walpole credited his story to a fake manuscript writer from 1529? And why would he use a pseudonym instead of his real name? What may be some other underlying reasons for these decisions?

- Why is the emphasis on heritage, bloodlines, and ancestry such an important theme in the Gothic?

- Design your own Gothic estate, inspired by the castle in the frontispiece to The Castle of Otranto . What would you include, and why? Include a written “rationale” with your illustration.

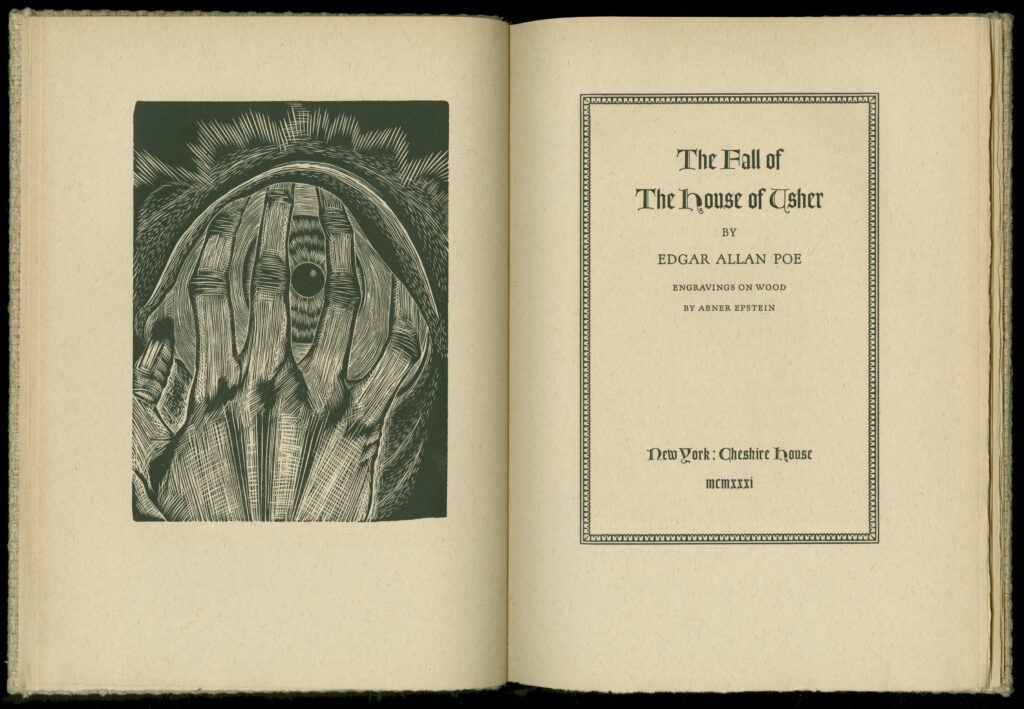

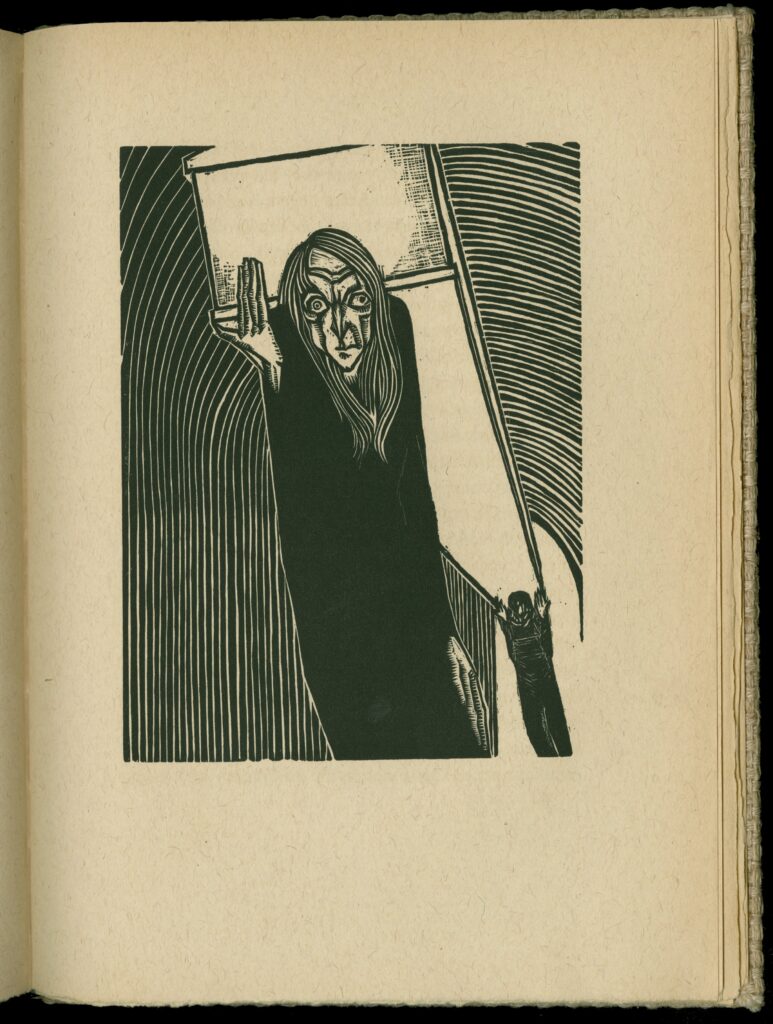

This section’s featured woodcut image depicts the famous scene in Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1839), during which Poe’s narrator and Roderick Usher carrys his sister, Madeline, into the family tomb. Abner Epstein’s woodcut, in a 20th-century edition of Poe’s story, depicts a stark aesthetic, with Roderick’s disheveled look—and maddening gaze—placed front and center. This pictorial representation of Poe’s story contrasts the flowery, fantastical illustration of Otranto in Horace’s frontispiece, pictured in the previous section. Instead of focusing on the romantic scenery and majestic buildings, this woodcut illustrates the downward spiral of one’s own psyche, symbolized further in the downward descent of the (we later learn, half-live) corpse into the tomb.

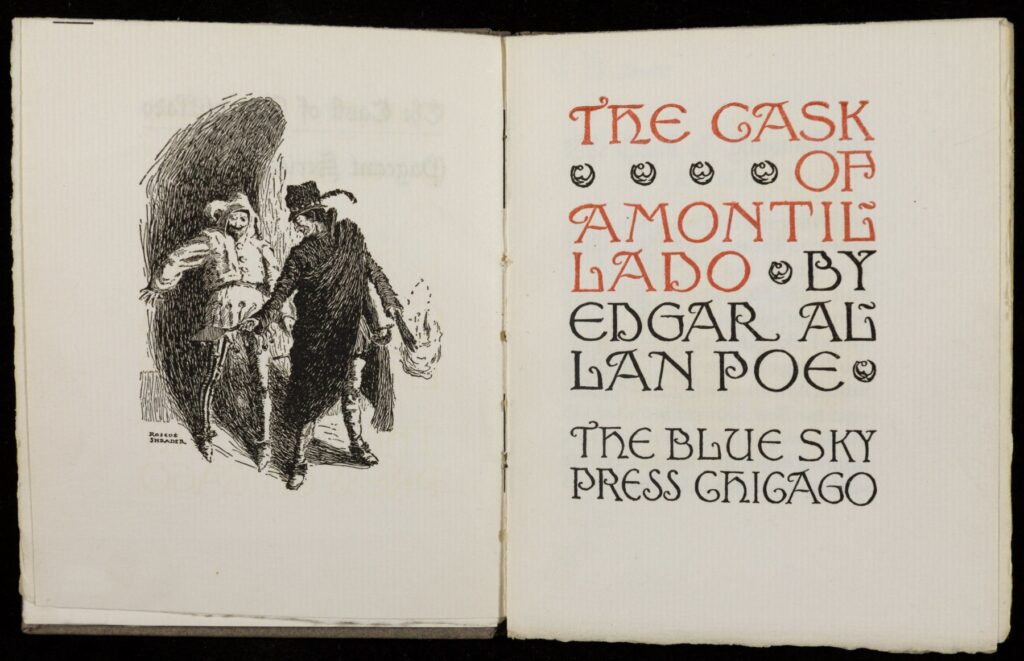

Because of their different time periods and artistic mediums, these two illustrations call attention to how the Gothic has evolved as a literary genre across the centuries. Certainly, we identify important influences of the eighteenth-century Gothic in American works; take, for instance, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado,” which takes place in an unknown Italian city, in the catacombs during a raucous Carnival festival.

The American Gothic as a genre generally shifts away from the outward appearances of haunted landscapes and buildings, as well as outward signs of the supernatural, to the inward terrors of one’s own mind. The image below of the title page and illustration for The Cask of Amontillado is an apt symbol of Poe’s preoccupations as a storyteller—as well as his important influence on the Gothic genre in America.

Many American writers have been categorized as “Gothic” writers, including (but not limited to): Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe, Emily Dickinson, Henry James, Ambrose Bierce, Stephen Crane, William Faulkner, Cormac McCarthy, Toni Morrison, Stephen King, and Joyce Carol Oates. These writers deploy elements of the Gothic to illustrate their social, political, and cultural concerns about what they observe around them.

The American Gothic genre is at once vast and diverse, and unified by shared thematic concerns. Whereas earlier centuries emphasized the Gothic genre as a form of escapist literature, with a “long ago and far away” atmosphere, the American Gothic focuses on important elements of daily life that, when framed in a Gothic nature, brings a new light to social issues that may be at first too “ordinary” to notice. In his book American Gothic (2009), Charles Crow claims that this genre enabled “the imaginative expression of the fears and forbidden desires of Americans” (1). In comparison to earlier versions of the Gothic, which focused on ancestral bloodlines and decaying, centuries-old castles, the American Gothic digs deeper into the darker, often psychological underbelly of everyday life. Even in outwardly “extra-ordinary” plot lines (a drunken party during carnival season, like in Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado,” for example), there lies an emphasis on one’s inner evils, drives, and secret desires. Poe, in particular, often utilizes a self-proclaimed “rational” narrator to illuminate his own inner demons and murderous drives (Crow).

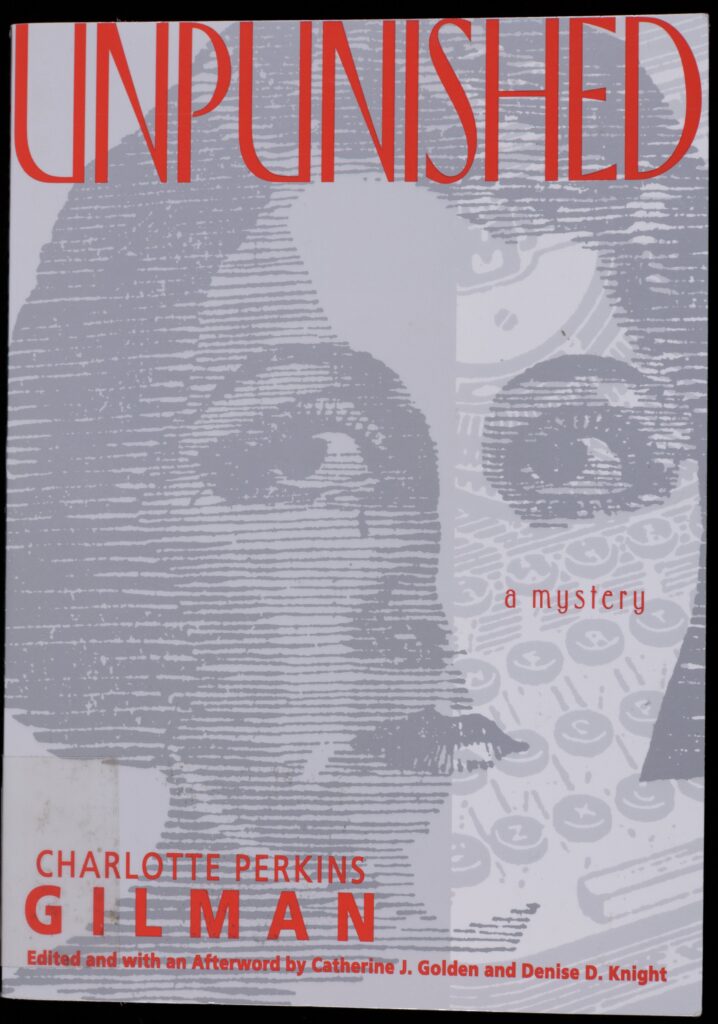

Examples of ordinary occurrences and events, framed with gothic qualities, include post-Reconstruction South and slavery (William Faulkner, “A Rose for Emily”), and women’s issues, including depression, childbirth, and the abuse by men in the medical profession (Charlotte Perkins Gilman, “The Yellow Wall-Paper”). The former, an example of the Southern Gothic sub-genre, rests on the tension between a dangerously false, nostalgic representation of American slavery with the economic, social, and physical realities of slavery and its aftermath in American history. The latter illustrates the feminist possibilities within what may originally seem a “damsel-in-distress” genre. Gilman’s loosely autobiographical story of a woman’s descent into madness while participating in the “rest cure” illuminates the conflict between one’s desires (especially to engage in creative expression, through writing) and the social constraints of marriage and motherhood. Additionally, “The Yellow Wall-Paper” has played a crucial role in scholarship that re-examines the American literary “canon” and makes conscious efforts to bring more women writers into the conversation. While less popular on class syllabi than “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” Gilman’s re-discovered manuscript, Unpunished: A Mystery (pictured here), engages with themes of the American Gothic discussed in this essay. This book was published in 1997 by The Feminist Press, a publisher that continues to play a crucial role in bringing many women writers back into academic studies.

Crow, responding to and building from Leslie Fiedler’s definition of the American Gothic in his seminal work Love and Death in the American Novel (1960), writes that “[the] American Gothic is no longer defined as a narrow tradition bound by certain props (ruined castles, usually in foreign lands, and imperiled maidens). It is now usually seen as a tradition of oppositional literature, presenting in disturbing, usually frightening ways, a skeptical, ambiguous view of human nature and of history. The Gothic exposes the repressed, what is hidden, unspoken, deliberately forgotten, in the lives of individuals and of cultures” (2).

Crow’s assessment of the American Gothic prioritizes how the way things appear on the surface can amplify the felt, unseen terrors that lie beneath an individual, community, or nation.

- Compare and contrast the images from The Castle of Otranto and “The Fall of the House of Usher”. Aside from the ways they are discussed above, what are some other differences you notice in the representation of the Gothic? Similarities?

- What are some creative opportunities for the Gothic genre to change and evolve, within this new historical and geographical context of “America”?

- How does the inward turn to the psyche affect one’s interpretation of Gothic texts?

The American Gothic Wilderness

It would be impossible to catalog all of the important themes found in the American Gothic genre. Yet, one important way to identify what makes the American Gothic so unique is by identifying the role landscape plays in these narratives.

As previously discussed, the American Gothic takes on a more interior and psychological dimension to the earlier definitions of the Gothic. The openness, mystery, and wildness associated with the colonized American landscape provide a backdrop for exploring issues of cultural and national identities. Whereas the plot of the traditional Gothic story hinges on the physical environment’s architecture and spooky outward characteristics, the American Gothic uses the landscape to symbolize the beliefs, priorities, and anxieties of its characters and communities.

Contemporary scholars, educators, and students are right to call out the idea of the American landscape—as untouched, unoccupied territory—as a white colonizer’s fantasy, which has persisted in the American literary imagination. This fantasy demonized further the original inhabitants of North America, the Native Americans, and provided means of justification for the colonial settlers’ violent behaviors. One way we can study how the Gothic shifts away from the Old World context (like Walpole’s) to that of the New World is how the American landscape becomes utilized to these ends. There are no dilapidated Italian castles in which the plots unfold. The ghosts of one’s ancestral past are now replaced by cultural “others,” especially Native Americans. This brings to mind the idea that American Gothic narratives negotiate the anxiety of one’s lineage differently than Gothic stories across the pond; one common thread connecting much of early American Gothic writing is a proclaimed anxiety about the mysterious nature of the new republic’s lands, and its peoples.

One of the earliest writers of the American Gothic, Charles Brockden Brown (1771-1810), articulated the need to adjust a Gothic tale to America’s particular setting. He wrote in his preface to Edgar Huntly (1799), “Puerile superstition and exploded manners; Gothic castles and chimeras, are the materials usually employed for [‘engaging the sympathies’ of readers]. The incidents of Indian hostility, and the perils of the western wilderness, are far more suitable…” (Krause, qtd. in Crow, 25). Here Brockden Brown suggests that storytelling needs to shift to account for the specific contents of America—away from the “castles and chimeras” and towards the “perils of the western wilderness.” His problematic mention of “incidents of Indian hostility” positions the white colonizer as a potential victim of Native American terrors, but nevertheless depicts the role of the American wilderness as a sort of character in itself, rife with tales that entertain and entice readers.

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s short story “Young Goodman Brown” (first published anonymously in 1835, and later under his name in 1846) also contains these undertones of colonial anxiety about Native American inhabitants, while taking a slightly more spiritual angle. The eponymous protagonist goes on a mysterious errand in the forest that leads to his loss of faith in his community, including his wife, also named “Faith.” Here, Hawthorne deploys the American “wilderness” as a site for looking inward to one’s spirituality and that even the most pure and faithful of people may have a dark side.

In the context of the Charles Brockden Brown, Fiedler wrote on the author’s contribution to the gothic genre; however, one can apply his words to the larger idea of the American Gothic as a whole. For instance, Fielder wrote that Brockden Brown created “a tradition of dealing with the exaggerated and the grotesque, which impose themselves on us, not as they are verifiable in any external landscape or sociological observation of manners and men, but as they correspond in quality to our deepest fears and guilt as projected in our dreams or lived through in extreme situations” (142).

Roughly one hundred years later, Edgar Allan Poe picks up the important role of the landscape in the Gothic tradition. The narrator in “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1839) provides an important combination of “Old World” and “New World” ideas that came to define the American Gothic. He describes his arrival to the Usher estate, where his childhood friend, Roderick Usher, resides:

“I know not how it was—but, with the first glimpse of the building, a sense of insufferable gloom pervaded my spirit…I looked upon the scene before me—upon the mere house, and the simple landscape features of the domain—upon the bleak walls—upon the vacant eye-like windows—upon a few rank sedges—and upon a few white decayed trees—with an utter depression of soul which I can compare to no earthly sensation more properly than to the after-dream of the reveler upon opium—the bitter lapse into everyday life—the hideous dropping off of the veil. There was an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart—an unredeemed dreariness of thought which no goading of the imagination could torture into aught of the sublime. What was it—I paused to think—what was it that so unnerved me in the contemplation of the House of Usher?”

As this passage demonstrates, Poe uses the physical characteristics of the Usher estate to illuminate the gloomy or “creepy” feelings experienced by the narrator. As the story progresses, the lush and exotic-looking estate grounds and the decaying Usher mansion serve to reflect the spiritual decay of the Usher family line. While not a traditional representation of the “wilderness” per se, Poe nevertheless shows the untamed—and often, terrifying—nature of the human soul.

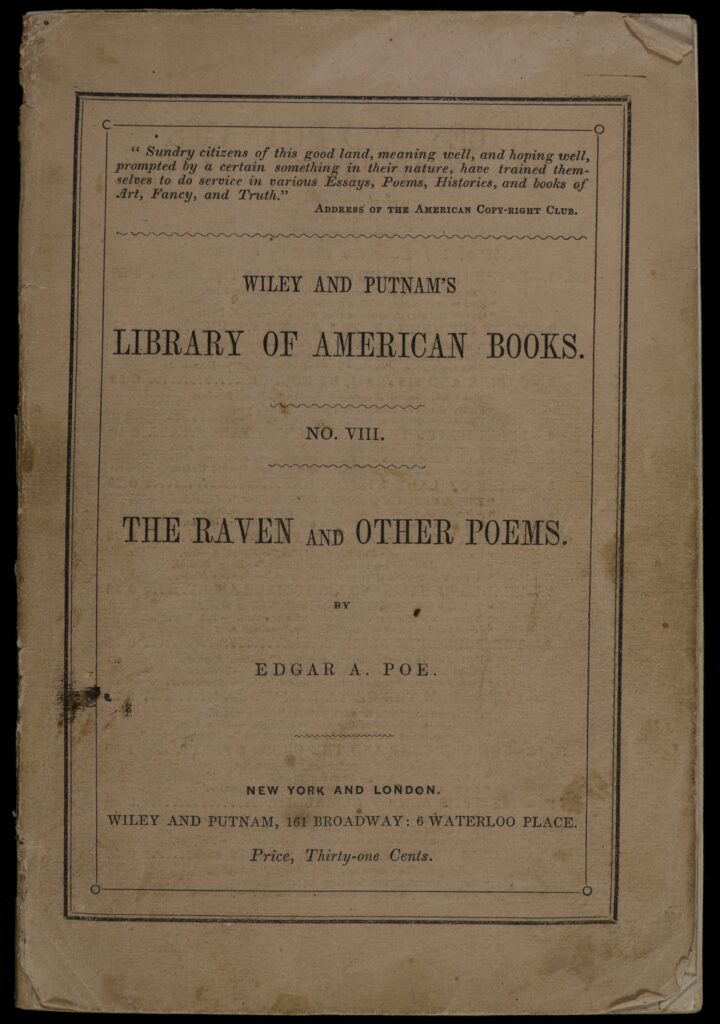

Selection: Edgar Allen Poe, The Raven and Other Poems (1845).

Other American texts, like Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel Beloved (1987), works with the theme of the American landscape and wilderness to illuminate other social and political issues intrinsic to the American historical experience. Morrison’s uses the southern slave plantation to reveal the dark and violent history of US enslavement. Morrison, and others, continue the tradition of the American Gothic and imbue it with themes that call attention to this nation’s fraught historical past.

- When placed alongside the earlier characteristics of the Gothic, which was associated with “Old World” traditions, how do the qualities of the American Gothic compare? Contrast?

- In the passage above from “The Fall of the House of Usher,” how does Poe stay loyal to earlier characteristics of the Gothic? How does he depart from them?

- Read Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” featured in this section. If one were to make a case for the American “wilderness” in this poem, what would it look like? How is it different than traditional approaches to Gothic landscapes? Further, how is it similar to–or different from–Poe’s description in “The Fall of the House of Usher”?

- What are some other narratives in American literature that you studied in which landscape plays an important role? In what ways do they engage with Gothic traditions?

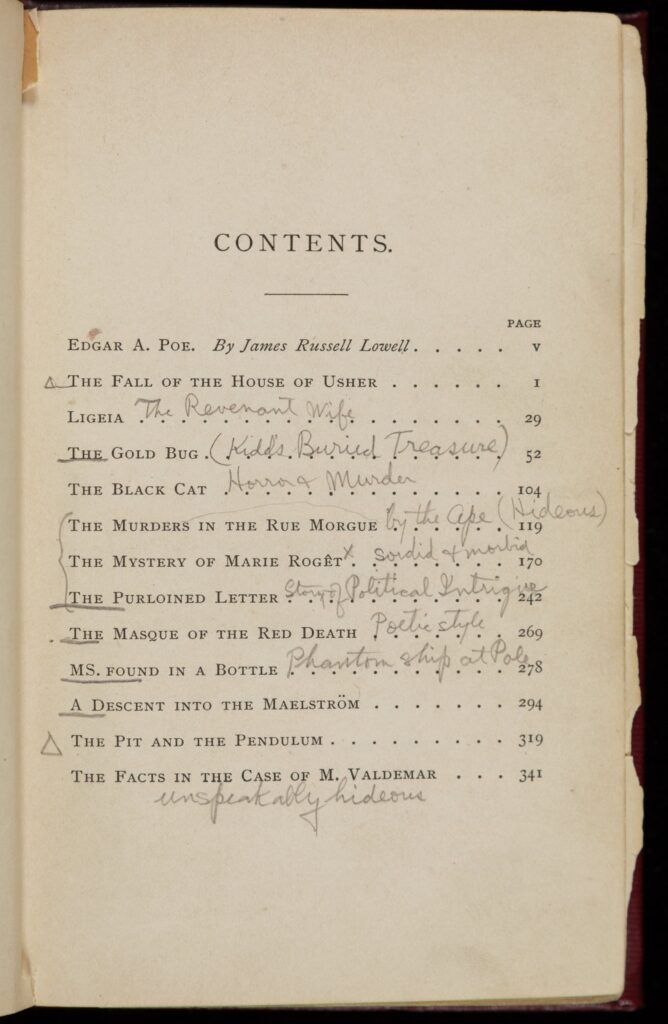

The Gothic Text in American Culture

The Table of Contents from Poe’s “Prose Tales” shows an unidentified reader engaging with the stories in Poe’s collected Prose Tales . The various reactions, indicated by the writing in the margins (also called “marginalia”), indicates how this reader connected with these stories so powerfully that he or she wanted to scribble commentary inside of the book itself. This is not an unusual thing to see in nineteenth-century books; however, in the context of the American Gothic, it is important to remember that these stories are meant to engage, titillate, and terrify their readers.

Aside from some important shared formal characteristics, Gothic American literature can allow us to witness important cultural moments and debates in American history. Various texts held at the Newberry Library show us the ways in which these stories circulated and—as in the case of the image of the table of contents from Poe’s Prose Tales —were received by audiences.

As this collection has shown, the Gothic genre is quite vast. It is partly such a large genre because people have used elements of the Gothic to communicate other ideas about society, politics, gender, health and medicine, and history. The Gothic genre has been utilized by writers to communicate messages about their contemporary lifetimes that they believe are problematic, controversial, or worthy of social change.

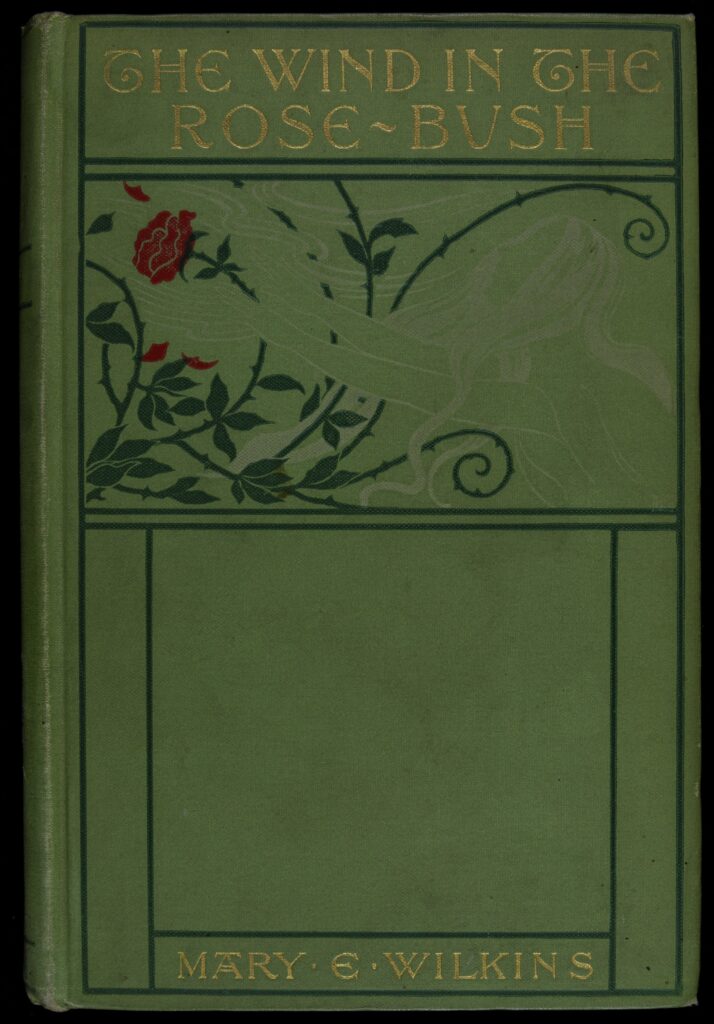

The paratextual qualities (characteristics of a text that do not relate to written content) of sentimental writer Mary E. Wilkins [Freeman’s] The Wind in the Rose-Bush (1903) contain several stylistic flourishes that suggest a targeted female readership. The book cover, including a red rose and a faintly-drawn woman spirit, ascribes to traditional conceptions of femininity as aesthetically beautiful and delicate. Even the gold type of Wilkins’s title adds a bit of glamour to this collection of ghost stories, and one can imagine the edition looking very elegant sitting in a bookshelf in a personal library. The illustrations, by Peter Newell, have a genteel, soft quality that humanizes the spiritual apparitions—almost as if to make the ghosts more personable and less threatening, despite their otherworldly state.

Selection: Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, The Wind in the Rose-Bush (1903).

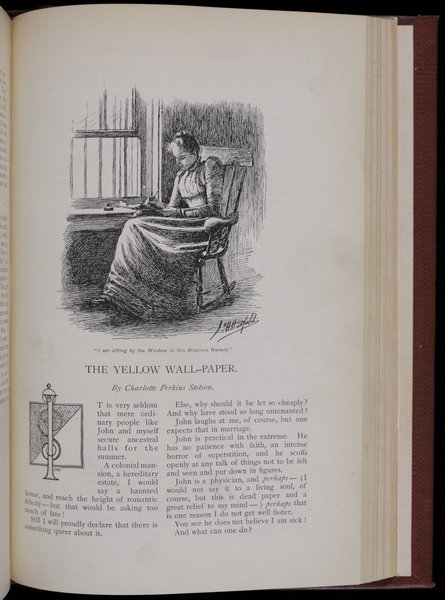

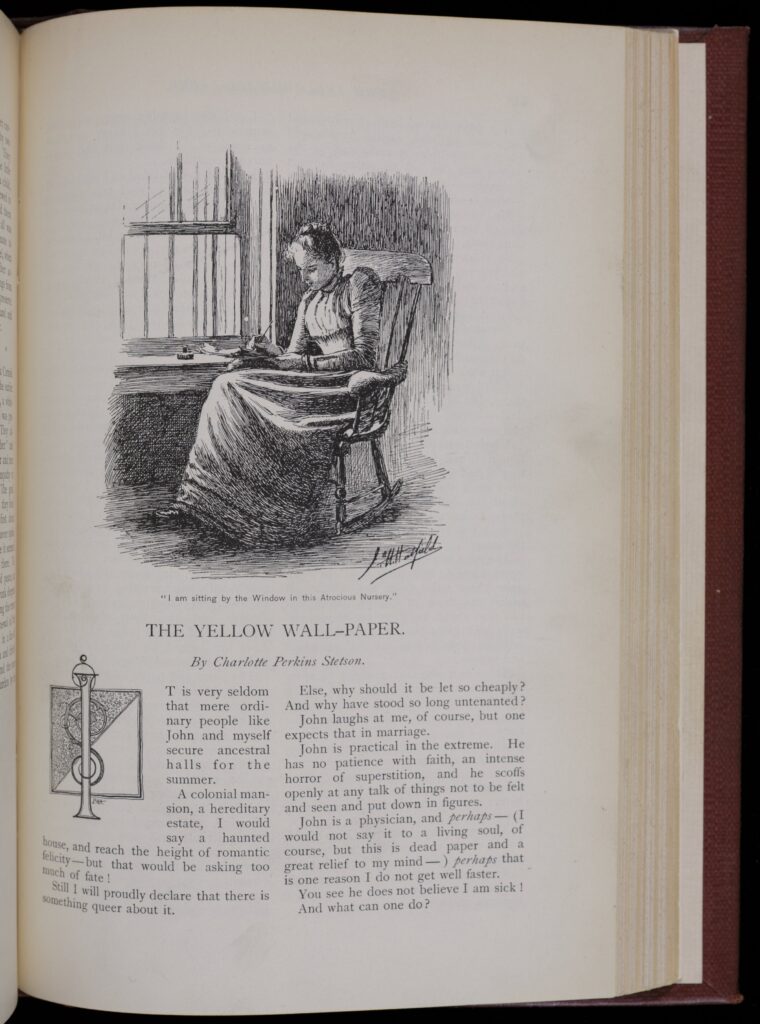

In addition to Wilkins’s book, many published short stories can reveal the way the Gothic genre can be used to advocate for social change. An important example in the women’s writing genre is Charlotte Perkins Stetson [Gilman’s] short story “The Yellow Wall-Paper” (1892), first published in New England Magazine .

This story, which is told in journal entries, is about a woman’s descent into mental illness or so-called “madness.” She becomes enthralled and, eventually, obsessed by the changing patterns in the wallpaper of her room (which used to be a nursery), and she eventually succumbs to them with erratic and obsessive behavior. Arguably exacerbated by the medical cure intended to treat her “nervous condition” in the first place, the narrator is a patient of the “rest cure”—a treatment that required complete abstention from physical and mental activity, including writing. For a creative and prolific writer, as well as feminist, such as Gilman, one can imagine that this issue was close to the author’s heart.

Selection: Charlotte Perkins Stetson Gilman, “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” in New England Magazine , volume 1 (1892).

“The Yellow Wall-Paper” contains many important themes found in the Gothic tradition, including the speaker’s powerlessness and expressions of inner turmoil and—possibly—madness. In one of her journal entries, she mentions the “queer” state of the old house in which she resides (647)—echoing Poe’s narrator’s feelings of uneasiness in the opening pages of “The Fall of the House of Usher.” She also describes feeling like a prisoner in her own home, and the lengths she would go to in order to be free: “I am getting angry enough to do something desperate. To jump out of the window would be admirable exercise, but the bars are too strong even to try” (655-656). By the end of the story, the narrator’s behavior upends the household, rendering her husband, a doctor named John, senseless on the floor after fainting.

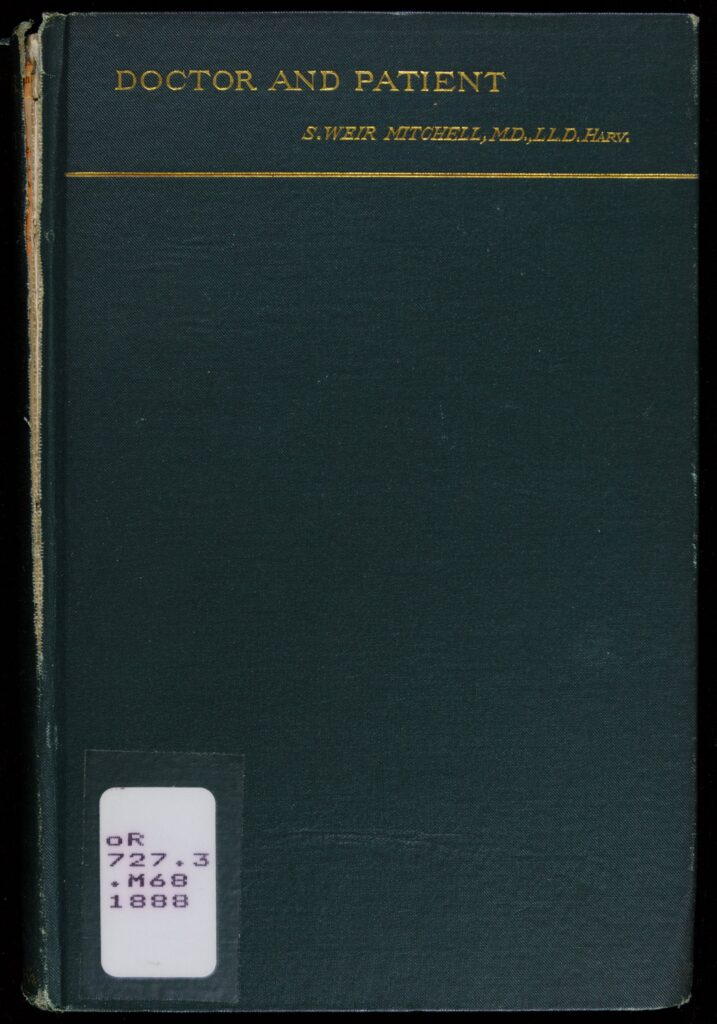

Many readers interpret “The Yellow Wall-Paper” as an autobiographical story inspired by Gilman’s own experiences under the rest cure, developed by the physician Silas Weir Mitchell. Gilman allegedly wrote the story to inspire Weir to consider the detrimental effects of the rest cure. The Newberry owns a copy of one of his publications, Doctor and Patient (1888).

For Gilman, the Gothic specter terrorizing her life is not an ancestral ghost, or a “haunted” mansion; it is the pressure of maternal and marital convention—the struggle between individual desires and social expectations for all women at the turn of the twentieth century. And while the story describes a house ridden by unusual events, ultimately “The Yellow Wall-Paper” cautions readers—women readers, in particular—of the terrifying and terrorizing presence of professional male doctors like Mitchell, with his abusive treatments and far-reaching power in the medical profession, domestic sphere, and the world of print. While Gilman wrote in a time before “mansplaining” was a mainstream term, she indeed criticized the all-powerful reach of Weir’s medical theories and treatments, and called attention to how his influence on the medical profession and women’s health exercises a traumatic influence over the body, as well as the mind. Alan Ryan sums up this idea of Gilman’s version of the Gothic the lines, “[Gilman’s story] is one of the finest, and strongest, tales of horror ever written. It may be a ghost story. Worse yet, it may not” (56).

Selection: Silas Weir Mitchell, Doctor and Patient (1888).

- What kinds of things can we learn from studying a text’s paratextual qualities? What do we learn about the anonymous reader of Prose Tales ? What are some assumptions we can make about how the reader is affected by the different stories?

- Given what we know already about the plot of “The Yellow Wall-Paper,” how does Gilman create terror out of everyday situations?

- If you were to create a book cover for “The Yellow Wall-Paper” to appeal to the stereotypical female readership from the nineteenth century, what would it look like and why? What aesthetic elements would you be sure to include? (Keep in mind the possible motivations for Gilman’s authorship of this text.)

- Examine the title page and opposite page from Mitchell’s Doctor and Patient . What kind of tone does it contain? Even if we weren’t to read the entire book, what kinds of evidence can we gather about Mitchell as a writer and physician? How is it different from the representation of medicine in “The Yellow-Wallpaper”?

Further Reading

Baker, Brian. “Gothic Masculinities.” The Routledge Companion to Gothic . Ed. Catherine Spooner and Emma McEvoy. New York: Routledge, 2007. 164-173.

Bondhus, Charlie. “Sublime Patriarchs and the Problems of the New Middle Class in Ann Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho and The Italian .” Gothic Studies 12.1 (2010): 13-32.

Brabon, Benjamin A., & Stéphanie Genz. Postfeminist Gothic: Critical Interventions in Contemporary Culture . New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

“The Castle of Otranto: The Creepy Tale that Launched Gothic Fiction.” BBC News Magazine . Accessed 8 Aug 2018.

Clery, E. J. Women’s Gothic: From Clara Reeve to Mary Shelley . Tavistock: Northcote House, 2000.

Crow, Charles L. American Gothic . Cardiff, Wales: University of Wales Press, 2009.

Cuddon, J. A. Dictionary of Literary Terms . London: Deutsch, 1977.

Edwards, Justin D. Gothic Passages: Racial Ambiguity and the American Gothic . Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2003.

Elbert, Monika & Bridget M. Marshall, eds. Transnational Gothic: Literary and Social Exchanges in the Long Nineteenth Century . Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2013.

Ellis, Kate Ferguson. The Contested Castle: Gothic Novels and the Subversion of Domestic Ideology . Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

Fiedler, Leslie. Love and Death in the American Novel . New York: Criterion Books, 1960.

Fleenor, Juliann E. “Introduction: The Female Gothic.” The Female Gothic . Ed. Juliann E. Fleenor. Montreal: Eden, 1983. 3-28.

Garrett, Peter. Gothic Reflections: Narrative Force in Nineteenth-Century Fiction . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003.

Gilbert, Sandra and Susan Gubar. The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979.

Goddu, Teresa A. Gothic America: Narrative, History, and Nation . New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.

Gross, Louis S. Redefining the American Gothic: from Wieland to Day of the Dead . Ann Arbor, MI: U of Michigan P, 1989.