Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- 10 Research Question Examples to Guide Your Research Project

10 Research Question Examples to Guide your Research Project

Published on October 30, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on October 19, 2023.

The research question is one of the most important parts of your research paper , thesis or dissertation . It’s important to spend some time assessing and refining your question before you get started.

The exact form of your question will depend on a few things, such as the length of your project, the type of research you’re conducting, the topic , and the research problem . However, all research questions should be focused, specific, and relevant to a timely social or scholarly issue.

Once you’ve read our guide on how to write a research question , you can use these examples to craft your own.

| Research question | Explanation |

|---|---|

| The first question is not enough. The second question is more , using . | |

| Starting with “why” often means that your question is not enough: there are too many possible answers. By targeting just one aspect of the problem, the second question offers a clear path for research. | |

| The first question is too broad and subjective: there’s no clear criteria for what counts as “better.” The second question is much more . It uses clearly defined terms and narrows its focus to a specific population. | |

| It is generally not for academic research to answer broad normative questions. The second question is more specific, aiming to gain an understanding of possible solutions in order to make informed recommendations. | |

| The first question is too simple: it can be answered with a simple yes or no. The second question is , requiring in-depth investigation and the development of an original argument. | |

| The first question is too broad and not very . The second question identifies an underexplored aspect of the topic that requires investigation of various to answer. | |

| The first question is not enough: it tries to address two different (the quality of sexual health services and LGBT support services). Even though the two issues are related, it’s not clear how the research will bring them together. The second integrates the two problems into one focused, specific question. | |

| The first question is too simple, asking for a straightforward fact that can be easily found online. The second is a more question that requires and detailed discussion to answer. | |

| ? dealt with the theme of racism through casting, staging, and allusion to contemporary events? | The first question is not — it would be very difficult to contribute anything new. The second question takes a specific angle to make an original argument, and has more relevance to current social concerns and debates. |

| The first question asks for a ready-made solution, and is not . The second question is a clearer comparative question, but note that it may not be practically . For a smaller research project or thesis, it could be narrowed down further to focus on the effectiveness of drunk driving laws in just one or two countries. |

Note that the design of your research question can depend on what method you are pursuing. Here are a few options for qualitative, quantitative, and statistical research questions.

| Type of research | Example question |

|---|---|

| Qualitative research question | |

| Quantitative research question | |

| Statistical research question |

Other interesting articles

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

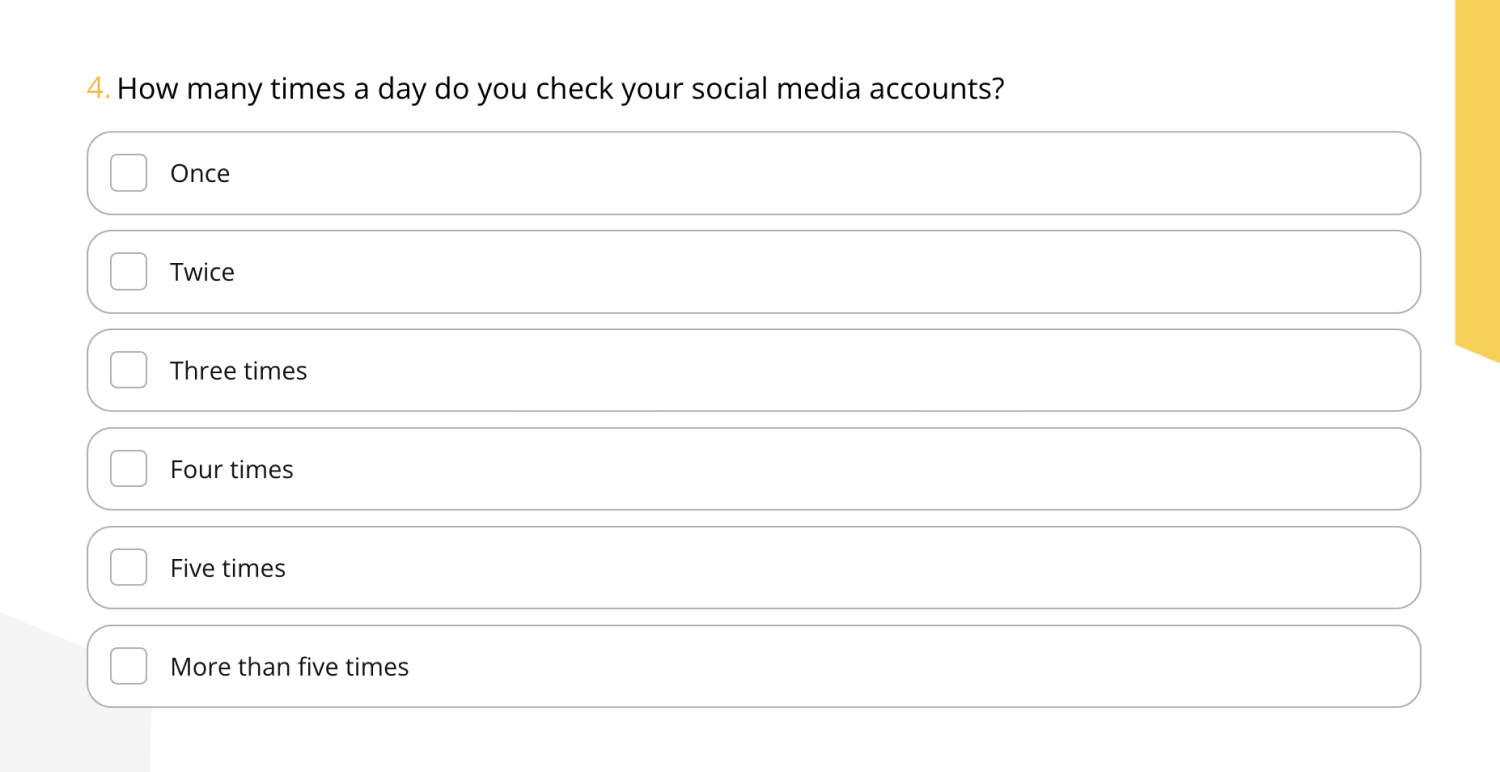

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, October 19). 10 Research Question Examples to Guide your Research Project. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-question-examples/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to choose a dissertation topic | 8 steps to follow, evaluating sources | methods & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write a Research Question

Academic writing and research require a distinct focus and direction. A well-designed research question gives purpose and clarity to your research. In addition, it helps your readers understand the issue you are trying to address and explore.

Every time you want to know more about a subject, you will pose a question. The same idea is used in research as well. You must pose a question in order to effectively address a research problem. That's why the research question is an integral part of the research process. Additionally, it offers the author writing and reading guidelines, be it qualitative research or quantitative research.

In your research paper , you must single out just one issue or problem. The specific issue or claim you wish to address should be included in your thesis statement in order to clarify your main argument.

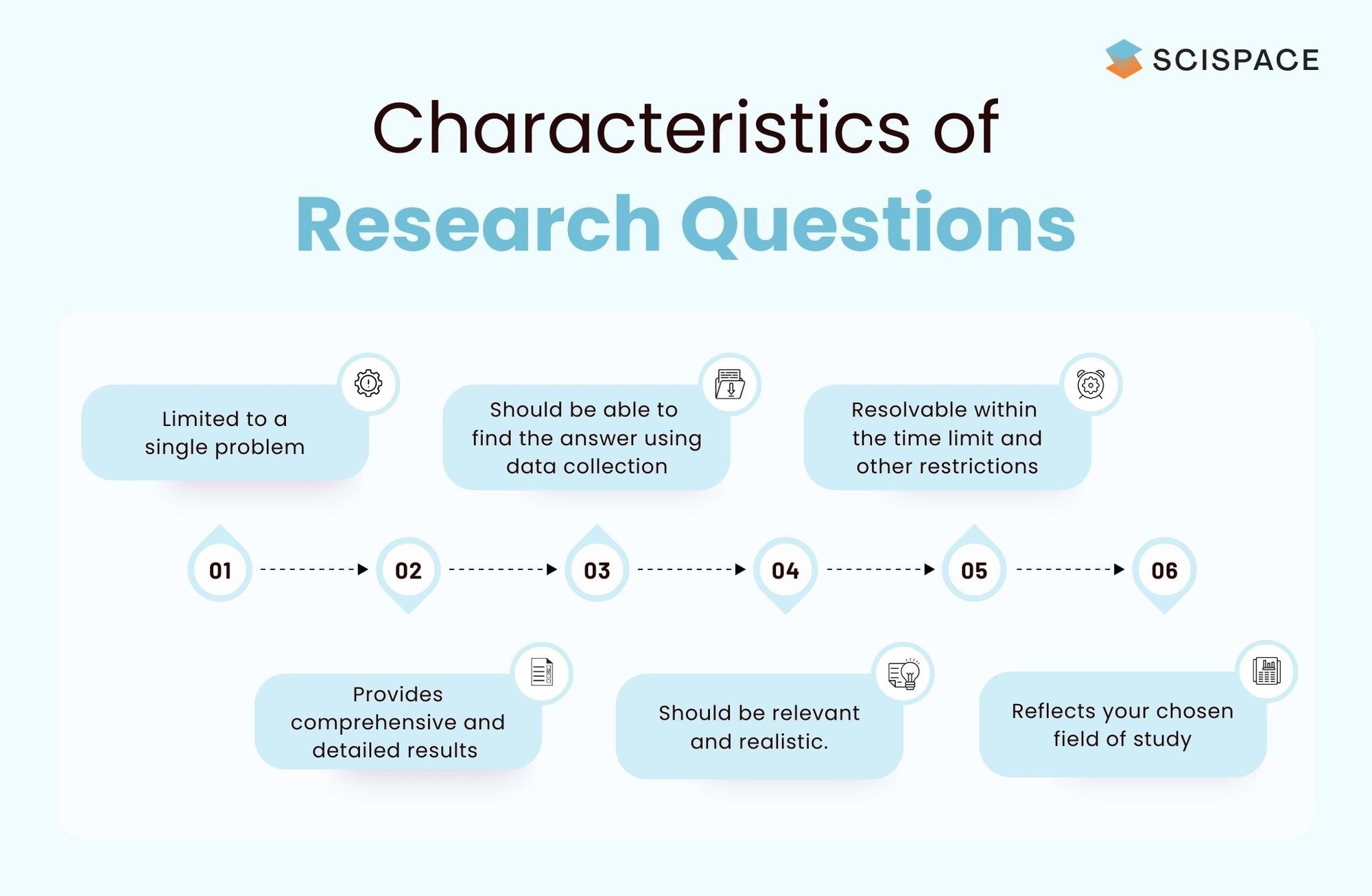

A good research question must have the following characteristics.

- Should include only one problem in the research question

- Should be able to find the answer using primary data and secondary data sources

- Should be possible to resolve within the given time and other constraints

- Detailed and in-depth results should be achievable

- Should be relevant and realistic.

- It should relate to your chosen area of research

While a larger project, like a thesis, might have several research questions to address, each one should be directed at your main area of study. Of course, you can use different research designs and research methods (qualitative research or quantitative research) to address various research questions. However, they must all be pertinent to the study's objectives.

What is a Research Question?

A research question is an inquiry that the research attempts to answer. It is the heart of the systematic investigation. Research questions are the most important step in any research project. In essence, it initiates the research project and establishes the pace for the specific research A research question is:

- Clear : It provides enough detail that the audience understands its purpose without any additional explanation.

- Focused : It is so specific that it can be addressed within the time constraints of the writing task.

- Succinct: It is written in the shortest possible words.

- Complex : It is not possible to answer it with a "yes" or "no", but requires analysis and synthesis of ideas before somebody can create a solution.

- Argumental : Its potential answers are open for debate rather than accepted facts.

A good research question usually focuses on the research and determines the research design, methodology, and hypothesis. It guides all phases of inquiry, data collection, analysis, and reporting. You should gather valuable information by asking the right questions.

Why are Research Questions so important?

Regardless of whether it is a qualitative research or quantitative research project, research questions provide writers and their audience with a way to navigate the writing and research process. Writers can avoid "all-about" papers by asking straightforward and specific research questions that help them focus on their research and support a specific thesis.

Types of Research Questions

There are two types of research: Qualitative research and Quantitative research . There must be research questions for every type of research. Your research question will be based on the type of research you want to conduct and the type of data collection.

The first step in designing research involves identifying a gap and creating a focused research question.

Below is a list of common research questions that can be used in a dissertation. Keep in mind that these are merely illustrations of typical research questions used in dissertation projects. The real research questions themselves might be more difficult.

Research Question Type | Question |

Descriptive | What are the properties of A? |

Comparative | What are the similarities and distinctions between A and B? |

Correlational | What can you do to correlate variables A and B? |

Exploratory | What factors affect the rate of C's growth? Are A and B also influencing C? |

Explanatory | What are the causes for C? What does A do to B? What's causing D? |

Evaluation | What is the impact of C? What role does B have? What are the benefits and drawbacks of A? |

Action-Based | What can you do to improve X? |

Example Research Questions

The following are a few examples of research questions and research problems to help you understand how research questions can be created for a particular research problem.

Problem | Question |

Due to poor revenue collection, a small-sized company ('A') in the UK cannot allocate a marketing budget next year. | What practical steps can the company take to increase its revenue? |

Many graduates are now working as freelancers even though they have degrees from well-respected academic institutions. But what's the reason these young people choose to work in this field? | Why do fresh graduates choose to work for themselves rather than full-time? What are the benefits and drawbacks of the gig economy? What do age, gender, and academic qualifications do with people's perceptions of freelancing? |

Steps to Write Research Questions

You can focus on the issue or research gaps you're attempting to solve by using the research questions as a direction.

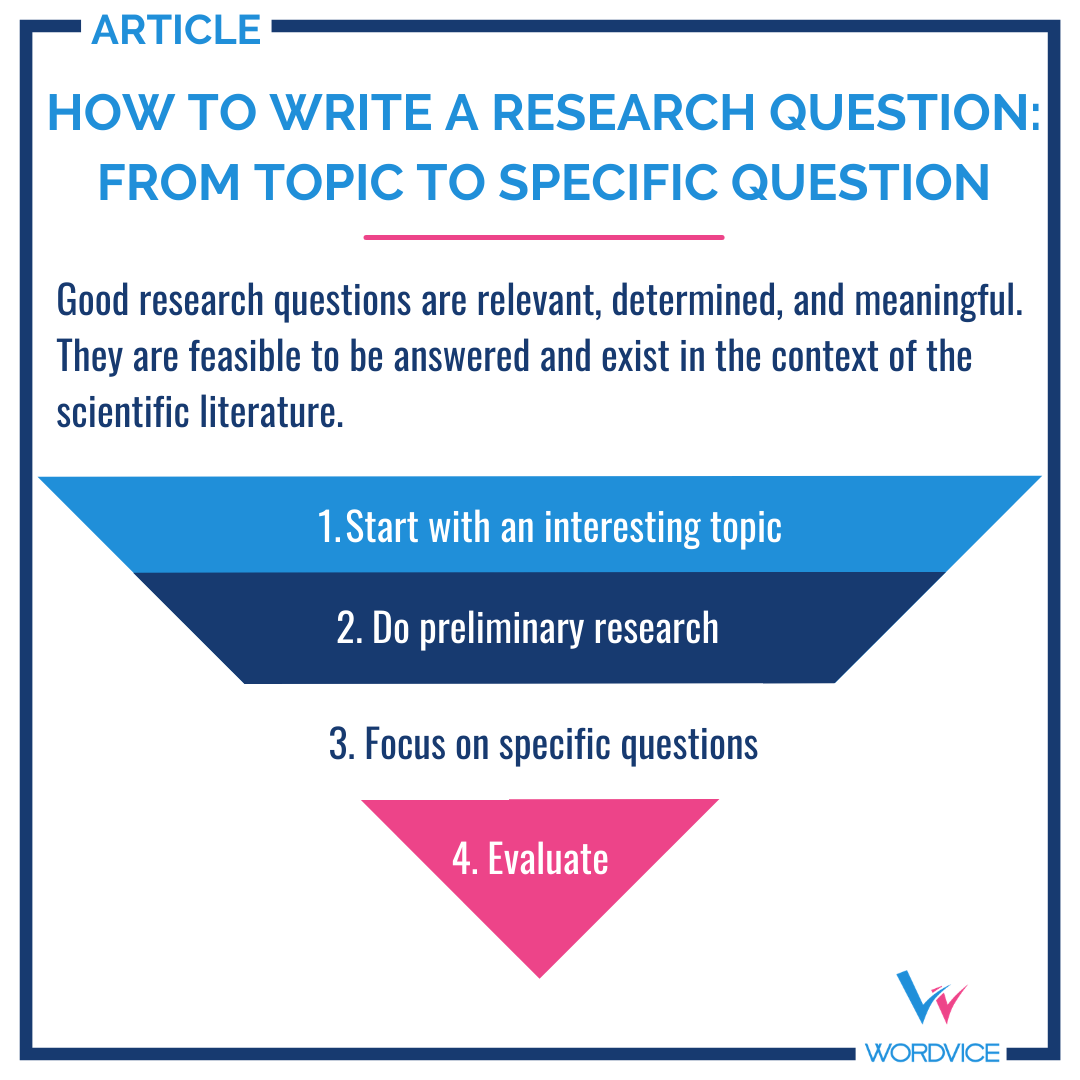

If you're unsure how to go about writing a good research question, these are the steps to follow in the process:

- Select an interesting topic Always choose a topic that interests you. Because if your curiosity isn’t aroused by a subject, you’ll have a hard time conducting research around it. Alos, it’s better that you pick something that’s neither too narrow or too broad.

- Do preliminary research on the topic Search for relevant literature to gauge what problems have already been tackled by scholars. You can do that conveniently through repositories like Scispace , where you’ll find millions of papers in one place. Once you do find the papers you’re looking for, try our reading assistant, SciSpace Copilot to get simple explanations for the paper . You’ll be able to quickly understand the abstract, find the key takeaways, and the main arguments presented in the paper. This will give you a more contextual understanding of your subject and you’ll have an easier time identifying knowledge gaps in your discipline.

Also: ChatPDF vs. SciSpace Copilot: Unveiling the best tool for your research

- Consider your audience It is essential to understand your audience to develop focused research questions for essays or dissertations. When narrowing down your topic, you can identify aspects that might interest your audience.

- Ask questions Asking questions will give you a deeper understanding of the topic. Evaluate your question through the What, Why, When, How, and other open-ended questions assessment.

- Assess your question Once you have created a research question, assess its effectiveness to determine if it is useful for the purpose. Refine and revise the dissertation research question multiple times.

Additionally, use this list of questions as a guide when formulating your research question.

Are you able to answer a specific research question? After identifying a gap in research, it would be helpful to formulate the research question. And this will allow the research to solve a part of the problem. Is your research question clear and centered on the main topic? It is important that your research question should be specific and related to your central goal. Are you tackling a difficult research question? It is not possible to answer the research question with a simple yes or no. The problem requires in-depth analysis. It is often started with "How" and "Why."

Start your research Once you have completed your dissertation research questions, it is time to review the literature on similar topics to discover different perspectives.

Strong Research Question Samples

Uncertain: How should social networking sites work on the hatred that flows through their platform?

Certain: What should social media sites like Twitter or Facebook do to address the harm they are causing?

This unclear question does not specify the social networking sites that are being used or what harm they might be causing. In addition, this question assumes that the "harm" has been proven and/or accepted. This version is more specific and identifies the sites (Twitter, Facebook), the type and extent of harm (privacy concerns), and who might be suffering from that harm (users). Effective research questions should not be ambiguous or interpreted.

Unfocused: What are the effects of global warming on the environment?

Focused: What are the most important effects of glacial melting in Antarctica on penguins' lives?

This broad research question cannot be addressed in a book, let alone a college-level paper. Focused research targets a specific effect of global heating (glacial melting), an area (Antarctica), or a specific animal (penguins). The writer must also decide which effect will have the greatest impact on the animals affected. If in doubt, narrow down your research question to the most specific possible.

Too Simple: What are the U.S. doctors doing to treat diabetes?

Appropriately complex: Which factors, if any, are most likely to predict a person's risk of developing diabetes?

This simple version can be found online. It is easy to answer with a few facts. The second, more complicated version of this question is divided into two parts. It is thought-provoking and requires extensive investigation as well as evaluation by the author. So, ensure that a quick Google search should not answer your research question.

How to write a strong Research Question?

The foundation of all research is the research question. You should therefore spend as much time as necessary to refine your research question based on various data.

You can conduct your research more efficiently and analyze your results better if you have great research questions for your dissertation, research paper , or essay .

The following criteria can help you evaluate the strength and importance of your research question and can be used to determine the strength of your research question:

- Researchable

- It should only cover one issue.

- A subjective judgment should not be included in the question.

- It can be answered with data analysis and research.

- Specific and Practical

- It should not contain a plan of action, policy, or solution.

- It should be clearly defined

- Within research limits

- Complex and Arguable

- It shouldn't be difficult to answer.

- To find the truth, you need in-depth knowledge

- Allows for discussion and deliberation

- Original and Relevant

- It should be in your area of study

- Its results should be measurable

- It should be original

Conclusion - How to write Research Questions?

Research questions provide a clear guideline for research. One research question may be part of a larger project, such as a dissertation. However, each question should only focus on one topic.

Research questions must be answerable, practical, specific, and applicable to your field. The research type that you use to base your research questions on will determine the research topic. You can start by selecting an interesting topic and doing preliminary research. Then, you can begin asking questions, evaluating your questions, and start your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace ResearchGPT . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, read, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

How to Write a Research Question: Types and Examples

The first step in any research project is framing the research question. It can be considered the core of any systematic investigation as the research outcomes are tied to asking the right questions. Thus, this primary interrogation point sets the pace for your research as it helps collect relevant and insightful information that ultimately influences your work.

Typically, the research question guides the stages of inquiry, analysis, and reporting. Depending on the use of quantifiable or quantitative data, research questions are broadly categorized into quantitative or qualitative research questions. Both types of research questions can be used independently or together, considering the overall focus and objectives of your research.

What is a research question?

A research question is a clear, focused, concise, and arguable question on which your research and writing are centered. 1 It states various aspects of the study, including the population and variables to be studied and the problem the study addresses. These questions also set the boundaries of the study, ensuring cohesion.

Designing the research question is a dynamic process where the researcher can change or refine the research question as they review related literature and develop a framework for the study. Depending on the scale of your research, the study can include single or multiple research questions.

A good research question has the following features:

- It is relevant to the chosen field of study.

- The question posed is arguable and open for debate, requiring synthesizing and analysis of ideas.

- It is focused and concisely framed.

- A feasible solution is possible within the given practical constraint and timeframe.

A poorly formulated research question poses several risks. 1

- Researchers can adopt an erroneous design.

- It can create confusion and hinder the thought process, including developing a clear protocol.

- It can jeopardize publication efforts.

- It causes difficulty in determining the relevance of the study findings.

- It causes difficulty in whether the study fulfils the inclusion criteria for systematic review and meta-analysis. This creates challenges in determining whether additional studies or data collection is needed to answer the question.

- Readers may fail to understand the objective of the study. This reduces the likelihood of the study being cited by others.

Now that you know “What is a research question?”, let’s look at the different types of research questions.

Types of research questions

Depending on the type of research to be done, research questions can be classified broadly into quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods studies. Knowing the type of research helps determine the best type of research question that reflects the direction and epistemological underpinnings of your research.

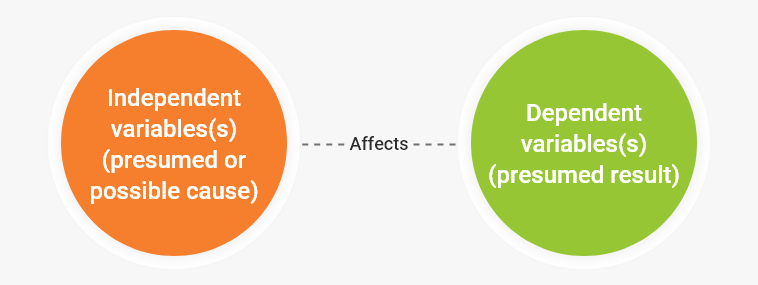

The structure and wording of quantitative 2 and qualitative research 3 questions differ significantly. The quantitative study looks at causal relationships, whereas the qualitative study aims at exploring a phenomenon.

- Quantitative research questions:

- Seeks to investigate social, familial, or educational experiences or processes in a particular context and/or location.

- Answers ‘how,’ ‘what,’ or ‘why’ questions.

- Investigates connections, relations, or comparisons between independent and dependent variables.

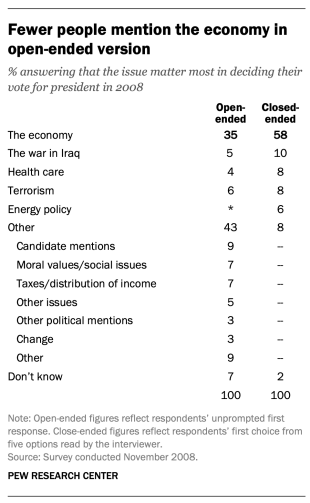

Quantitative research questions can be further categorized into descriptive, comparative, and relationship, as explained in the Table below.

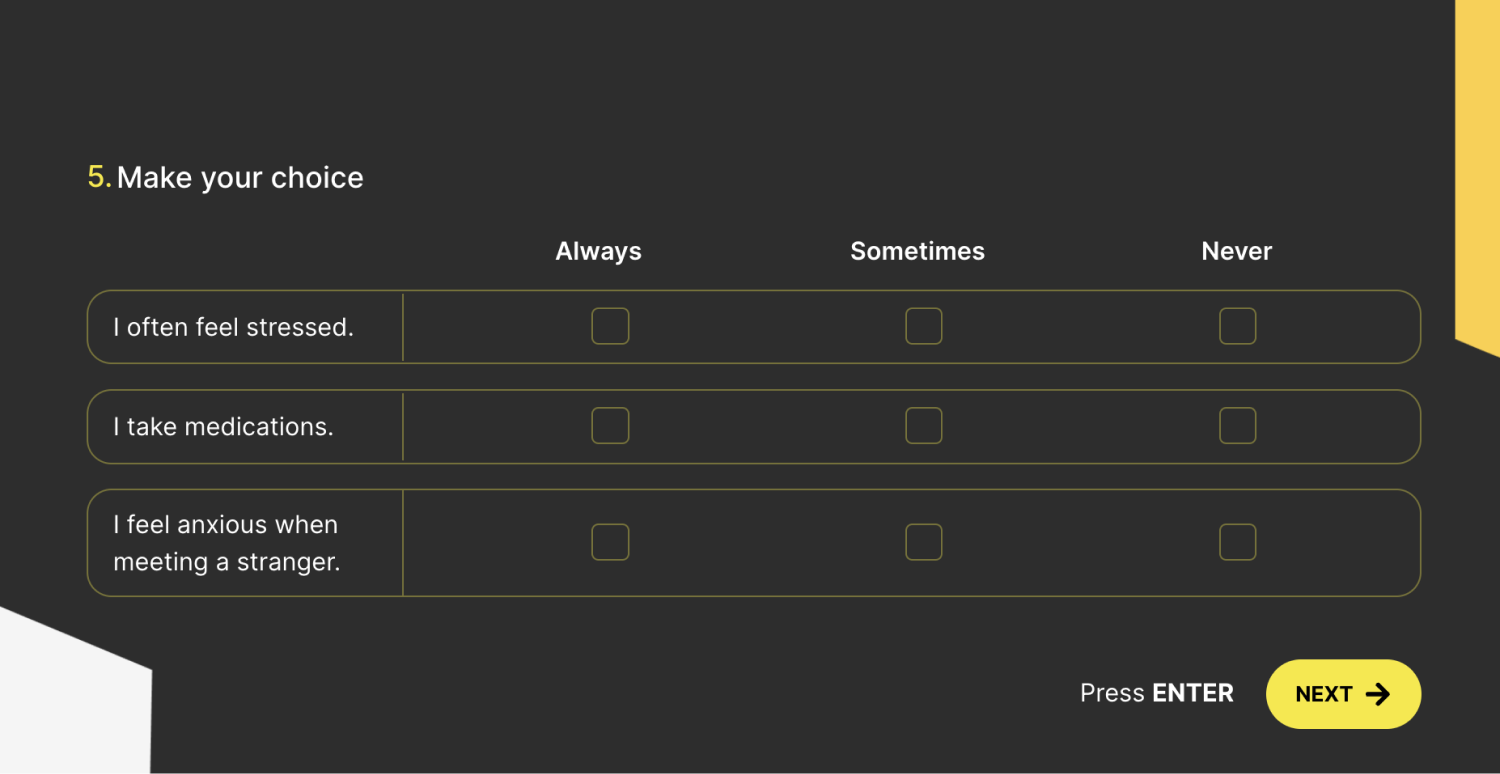

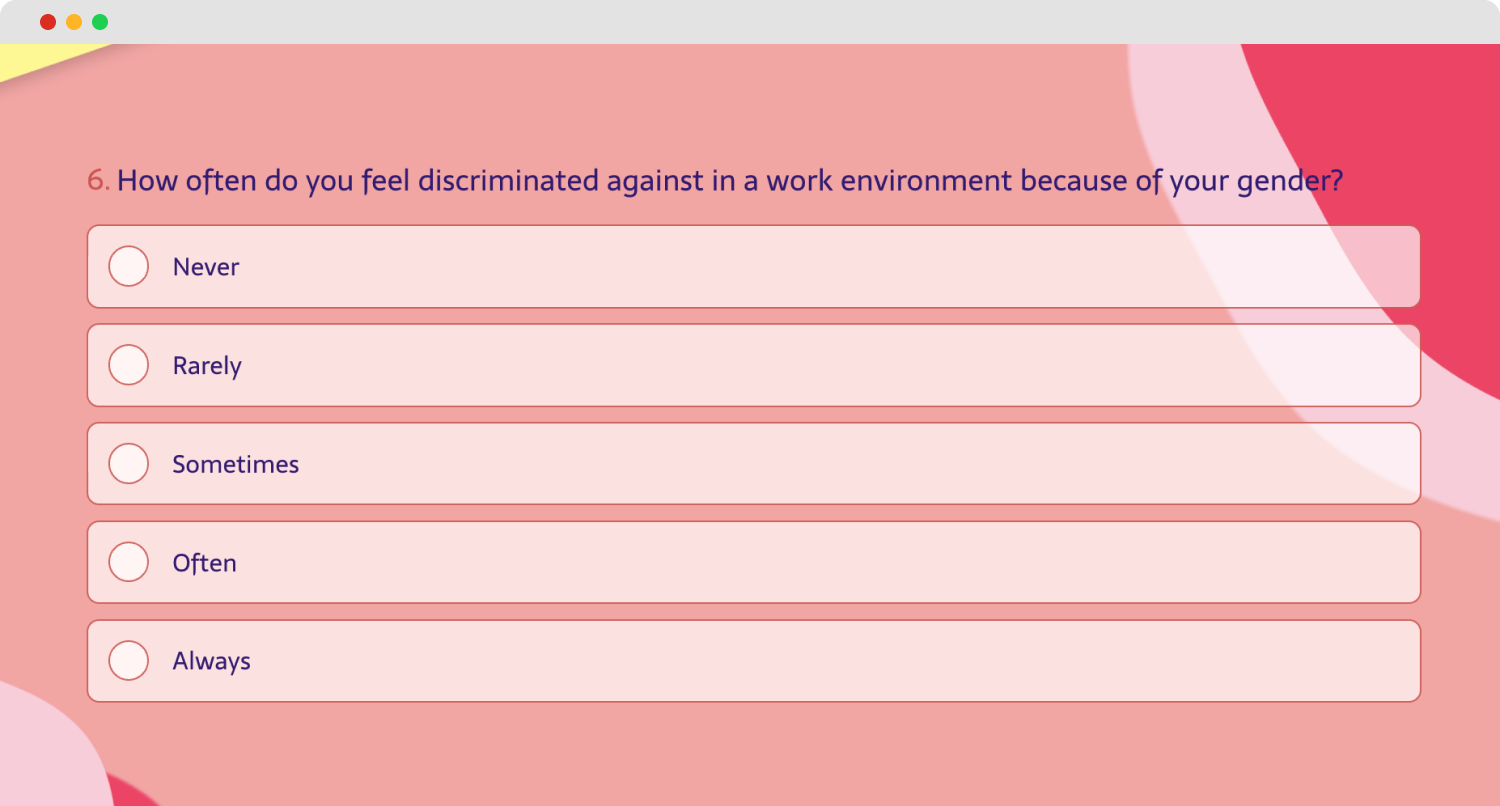

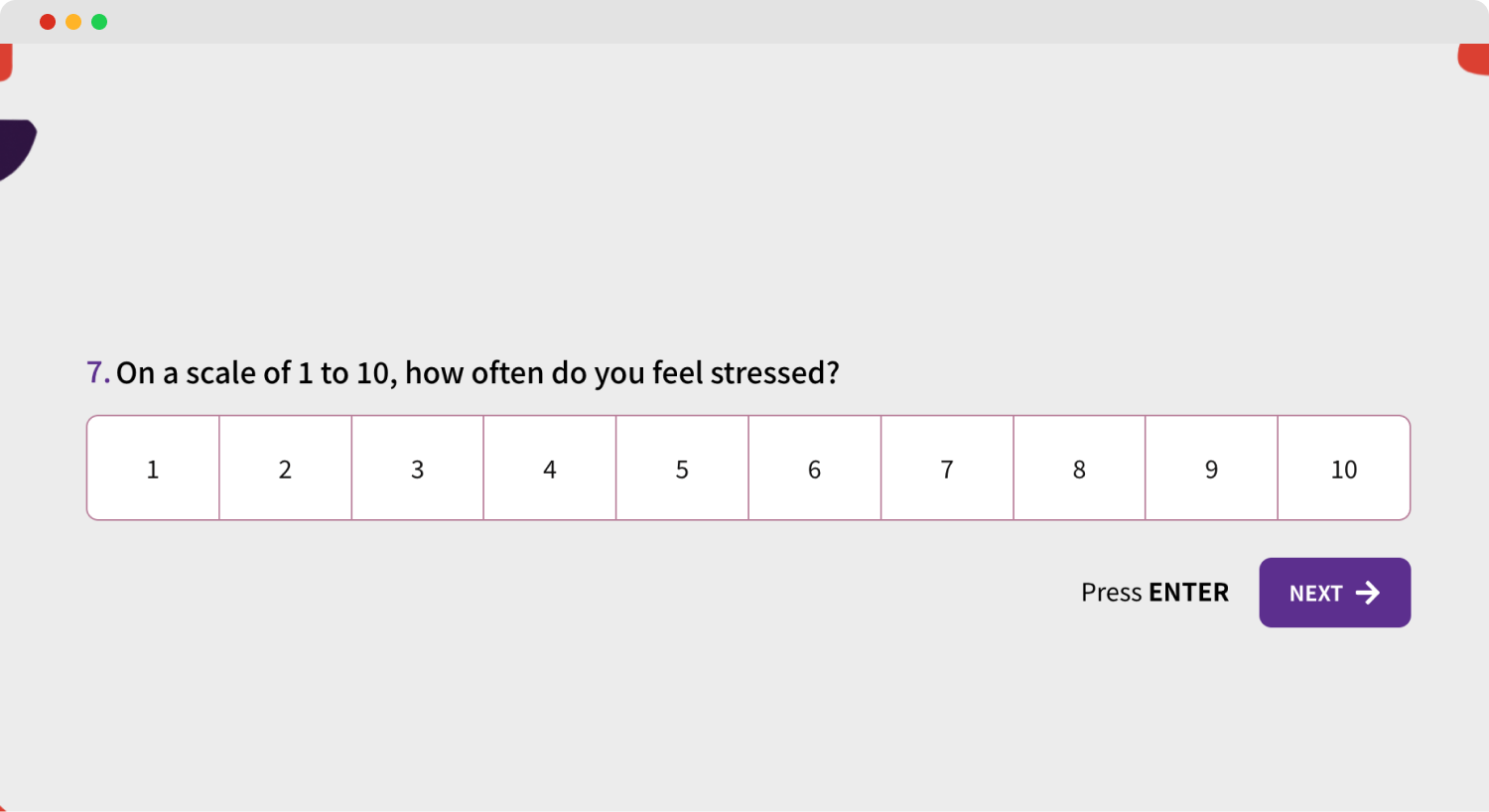

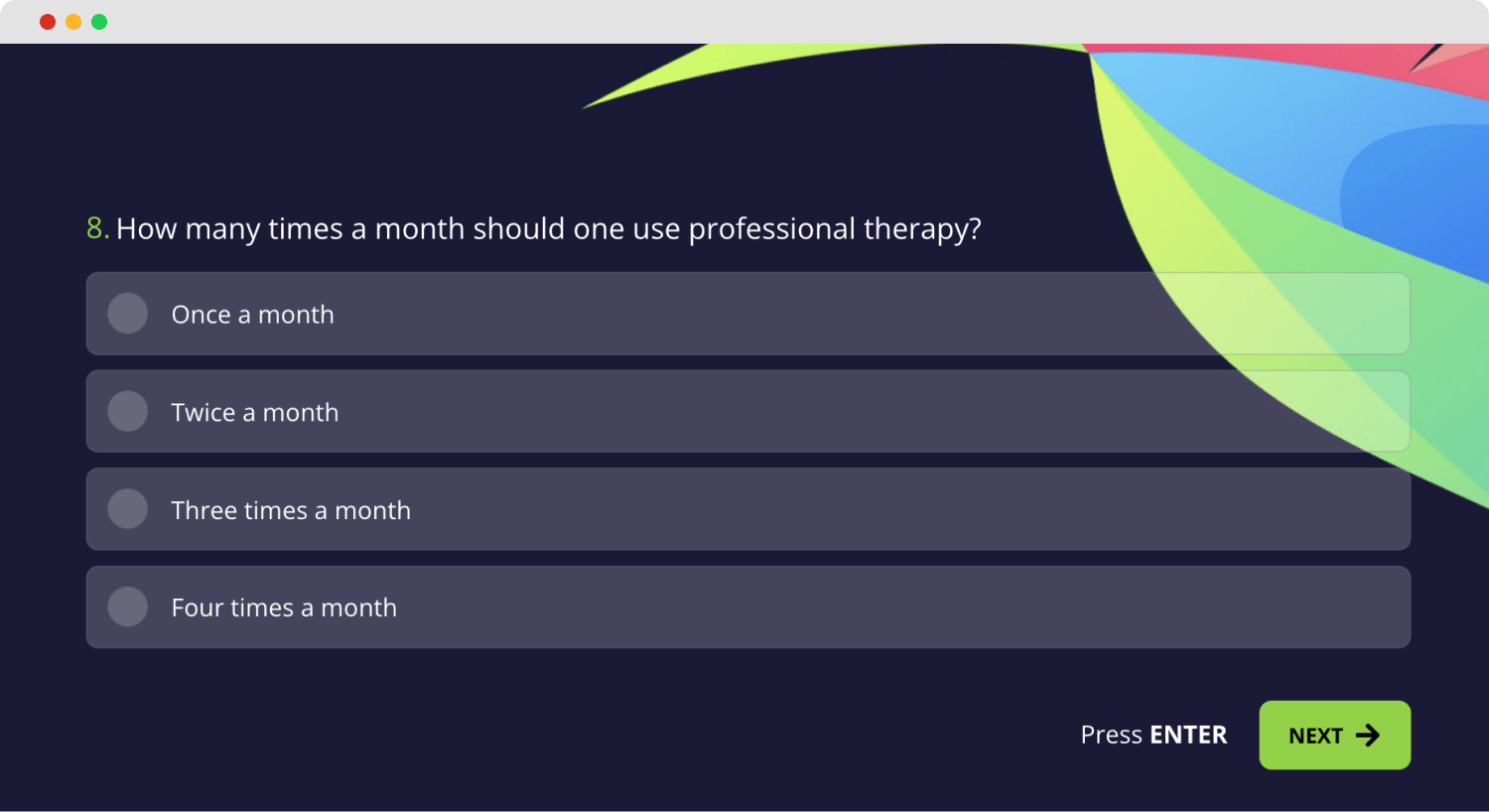

| Descriptive research questions | These measure the responses of a study’s population toward a particular question or variable. Common descriptive research questions will begin with “How much?”, “How regularly?”, “What percentage?”, “What time?”, “What is?” Research question example: How often do you buy mobile apps for learning purposes? |

| Comparative research questions | These investigate differences between two or more groups for an outcome variable. For instance, the researcher may compare groups with and without a certain variable. Research question example: What are the differences in attitudes towards online learning between visual and Kinaesthetic learners? |

| Relationship research questions | These explore and define trends and interactions between two or more variables. These investigate relationships between dependent and independent variables and use words such as “association” or “trends. Research question example: What is the relationship between disposable income and job satisfaction amongst US residents? |

- Qualitative research questions

Qualitative research questions are adaptable, non-directional, and more flexible. It concerns broad areas of research or more specific areas of study to discover, explain, or explore a phenomenon. These are further classified as follows:

| Exploratory Questions | These question looks to understand something without influencing the results. The aim is to learn more about a topic without attributing bias or preconceived notions. Research question example: What are people’s thoughts on the new government? |

| Experiential questions | These questions focus on understanding individuals’ experiences, perspectives, and subjective meanings related to a particular phenomenon. They aim to capture personal experiences and emotions. Research question example: What are the challenges students face during their transition from school to college? |

| Interpretive Questions | These questions investigate people in their natural settings to help understand how a group makes sense of shared experiences of a phenomenon. Research question example: How do you feel about ChatGPT assisting student learning? |

- Mixed-methods studies

Mixed-methods studies use both quantitative and qualitative research questions to answer your research question. Mixed methods provide a complete picture than standalone quantitative or qualitative research, as it integrates the benefits of both methods. Mixed methods research is often used in multidisciplinary settings and complex situational or societal research, especially in the behavioral, health, and social science fields.

What makes a good research question

A good research question should be clear and focused to guide your research. It should synthesize multiple sources to present your unique argument, and should ideally be something that you are interested in. But avoid questions that can be answered in a few factual statements. The following are the main attributes of a good research question.

- Specific: The research question should not be a fishing expedition performed in the hopes that some new information will be found that will benefit the researcher. The central research question should work with your research problem to keep your work focused. If using multiple questions, they should all tie back to the central aim.

- Measurable: The research question must be answerable using quantitative and/or qualitative data or from scholarly sources to develop your research question. If such data is impossible to access, it is better to rethink your question.

- Attainable: Ensure you have enough time and resources to do all research required to answer your question. If it seems you will not be able to gain access to the data you need, consider narrowing down your question to be more specific.

- You have the expertise

- You have the equipment and resources

- Realistic: Developing your research question should be based on initial reading about your topic. It should focus on addressing a problem or gap in the existing knowledge in your field or discipline.

- Based on some sort of rational physics

- Can be done in a reasonable time frame

- Timely: The research question should contribute to an existing and current debate in your field or in society at large. It should produce knowledge that future researchers or practitioners can later build on.

- Novel

- Based on current technologies.

- Important to answer current problems or concerns.

- Lead to new directions.

- Important: Your question should have some aspect of originality. Incremental research is as important as exploring disruptive technologies. For example, you can focus on a specific location or explore a new angle.

- Meaningful whether the answer is “Yes” or “No.” Closed-ended, yes/no questions are too simple to work as good research questions. Such questions do not provide enough scope for robust investigation and discussion. A good research question requires original data, synthesis of multiple sources, and original interpretation and argumentation before providing an answer.

Steps for developing a good research question

The importance of research questions cannot be understated. When drafting a research question, use the following frameworks to guide the components of your question to ease the process. 4

- Determine the requirements: Before constructing a good research question, set your research requirements. What is the purpose? Is it descriptive, comparative, or explorative research? Determining the research aim will help you choose the most appropriate topic and word your question appropriately.

- Select a broad research topic: Identify a broader subject area of interest that requires investigation. Techniques such as brainstorming or concept mapping can help identify relevant connections and themes within a broad research topic. For example, how to learn and help students learn.

- Perform preliminary investigation: Preliminary research is needed to obtain up-to-date and relevant knowledge on your topic. It also helps identify issues currently being discussed from which information gaps can be identified.

- Narrow your focus: Narrow the scope and focus of your research to a specific niche. This involves focusing on gaps in existing knowledge or recent literature or extending or complementing the findings of existing literature. Another approach involves constructing strong research questions that challenge your views or knowledge of the area of study (Example: Is learning consistent with the existing learning theory and research).

- Identify the research problem: Once the research question has been framed, one should evaluate it. This is to realize the importance of the research questions and if there is a need for more revising (Example: How do your beliefs on learning theory and research impact your instructional practices).

How to write a research question

Those struggling to understand how to write a research question, these simple steps can help you simplify the process of writing a research question.

| Topic selection | Choose a broad topic, such as “learner support” or “social media influence” for your study. Select topics of interest to make research more enjoyable and stay motivated. |

| Preliminary research | The goal is to refine and focus your research question. The following strategies can help: Skim various scholarly articles. List subtopics under the main topic. List possible research questions for each subtopic. Consider the scope of research for each of the research questions. Select research questions that are answerable within a specific time and with available resources. If the scope is too large, repeat looking for sub-subtopics. |

| Audience | When choosing what to base your research on, consider your readers. For college papers, the audience is academic. Ask yourself if your audience may be interested in the topic you are thinking about pursuing. Determining your audience can also help refine the importance of your research question and focus on items related to your defined group. |

| Generate potential questions | Ask open-ended “how?” and “why?” questions to find a more specific research question. Gap-spotting to identify research limitations, problematization to challenge assumptions made by others, or using personal experiences to draw on issues in your industry can be used to generate questions. |

| Review brainstormed questions | Evaluate each question to check their effectiveness. Use the FINER model to see if the question meets all the research question criteria. |

| Construct the research question | Multiple frameworks, such as PICOT and PEA, are available to help structure your research question. The frameworks listed below can help you with the necessary information for generating your research question. |

| Framework | Attributes of each framework |

| FINER | Feasible Interesting Novel Ethical Relevant |

| PICOT | Population or problem Intervention or indicator being studied Comparison group Outcome of interest Time frame of the study |

| PEO | Population being studied Exposure to preexisting conditions Outcome of interest |

Sample Research Questions

The following are some bad and good research question examples

- Example 1

| Unclear: How does social media affect student growth? |

| Clear: What effect does the daily use of Twitter and Facebook have on the career development goals of students? |

| Explanation: The first research question is unclear because of the vagueness of “social media” as a concept and the lack of specificity. The second question is specific and focused, and its answer can be discovered through data collection and analysis. |

- Example 2

| Simple: Has there been an increase in the number of gifted children identified? |

| Complex: What practical techniques can teachers use to identify and guide gifted children better? |

| Explanation: A simple “yes” or “no” statement easily answers the first research question. The second research question is more complicated and requires the researcher to collect data, perform in-depth data analysis, and form an argument that leads to further discussion. |

References:

- Thabane, L., Thomas, T., Ye, C., & Paul, J. (2009). Posing the research question: not so simple. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie , 56 (1), 71-79.

- Rutberg, S., & Bouikidis, C. D. (2018). Focusing on the fundamentals: A simplistic differentiation between qualitative and quantitative research. Nephrology Nursing Journal , 45 (2), 209-213.

- Kyngäs, H. (2020). Qualitative research and content analysis. The application of content analysis in nursing science research , 3-11.

- Mattick, K., Johnston, J., & de la Croix, A. (2018). How to… write a good research question. The clinical teacher , 15 (2), 104-108.

- Fandino, W. (2019). Formulating a good research question: Pearls and pitfalls. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia , 63 (8), 611.

- Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J., & Hayward, R. S. (1995). The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP journal club , 123 (3), A12-A13

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- Scientific Writing Style Guides Explained

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

- 8 Most Effective Ways to Increase Motivation for Thesis Writing

- 6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Transitive and Intransitive Verbs in the World of Research

Language and grammar rules for academic writing, you may also like, how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), research funding basics: what should a grant proposal..., how to write the first draft of a..., mla works cited page: format, template & examples, academic editing: how to self-edit academic text with..., measuring academic success: definition & strategies for excellence, phd qualifying exam: tips for success .

How to write a research question

Last updated

7 February 2023

Reviewed by

Miroslav Damyanov

In this article, we take an in-depth look at what a research question is, the different types of research questions, and how to write one (with examples). Read on to get started with your thesis, dissertation, or research paper .

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- What is a research question?

A research question articulates exactly what you want to learn from your research. It stems directly from your research objectives, and you will arrive at an answer through data analysis and interpretation.

However, it is not that simple to write a research question—even when you know the question you intend to answer with your study. The main characteristics of a good research question are:

Feasible. You need to have the resources and abilities to examine the question, collect the data, and give answers.

Interesting. Create research questions that offer fascinating insights into your industry.

Novel. Research questions have to offer something new within your field of study.

Ethical. The research question topic should be approved by the relevant authorities and review boards.

Relevant. Your research question should lead to visible changes in society or your industry.

Usually, you write one single research question to guide your entire research paper. The answer becomes the thesis statement—the central position of your argument. A dissertation or thesis, on the other hand, may require multiple problem statements and research questions. However, they should be connected and focused on a specific problem.

- Importance of the research question

A research question acts as a guide for your entire study. It serves two vital purposes:

to determine the specific issue your research paper addresses

to identify clear objectives

Therefore, it helps split your research into small steps that you need to complete to provide answers.

Your research question will also provide boundaries for your study, which help set limits and ensure cohesion.

Finally, it acts as a frame of reference for assessing your work. Bear in mind that research questions can evolve, shift, and change during the early stages of your study or project.

- Types of research questions

The type of research you are conducting will dictate the type of research question to use. Primarily, research questions are grouped into three distinct categories of study:

qualitative

quantitative

mixed-method

Let’s look at each of these in turn:

Quantitative research questions

The number-one rule of quantitative research questions is that they are precise. They mainly include:

independent and dependent variables

the exact population being studied

the research design to be used

Therefore, you must frame and finalize quantitative research questions before starting the study.

Equally, a quantitative research question creates a link between itself and the research design. These questions cannot be answered with simple 'yes' or' no' responses, so they begin with words like 'does', 'do', 'are', and 'is'.

Quantitative research questions can be divided into three categories:

Relationship research questions usually leverage words such as 'trends' and 'association' because they include independent and dependent variables. They seek to define or explore trends and interactions between multiple variables.

Comparative research questions tend to analyze the differences between different groups to find an outcome variable. For instance, you may decide to compare two distinct groups where a specific variable is present in one and absent in the other.

Descriptive research questions usually start with the word 'what' and aim to measure how a population will respond to one or more variables.

Qualitative research questions

Like quantitative research questions, these questions are linked to the research design. However, qualitative research questions may deal with a specific or broad study area. This makes them more flexible, very adaptable, and usually non-directional.

Use qualitative research questions when your primary aim is to explain, discover, or explore.

There are seven types of qualitative research questions:

Explanatory research questions investigate particular topic areas that aren't well known.

Contextual research questions describe the workings of what is already in existence.

Evaluative research questions examine the effectiveness of specific paradigms or methods.

Ideological research questions aim to advance existing ideologies.

Descriptive research questions describe an event.

Generative research questions help develop actions and theories by providing new ideas.

Emancipatory research questions increase social action engagement, usually to benefit disadvantaged people.

Mixed-methods studies

With mixed-methods studies, you combine qualitative and quantitative research elements to get answers to your research question. This approach is ideal when you need a more complete picture. through a blend of the two approaches.

Mixed-methods research is excellent in multidisciplinary settings, societal analysis, and complex situations. Consider the following research question examples, which would be ideal candidates for a mixed-methods approach

How can non-voter and voter beliefs about democracy (qualitative) help explain Town X election turnout patterns (quantitative)?

How does students’ perception of their study environment (quantitative) relate to their test score differences (qualitative)?

- Developing a strong research question—a step-by-step guide

Research questions help break up your study into simple steps so you can quickly achieve your objectives and find answers. However, how do you develop a good research question? Here is our step-by-step guide:

1. Choose a topic

The first step is to select a broad research topic for your study. Pick something within your expertise and field that interests you. After all, the research itself will stem from the initial research question.

2. Conduct preliminary research

Once you have a broad topic, dig deeper into the problem by researching past studies in the field and gathering requirements from stakeholders if you work in a business setting.

Through this process, you will discover articles that mention areas not explored in that field or products that didn’t resonate with people’s expectations in a particular industry. For instance, you could explore specific topics that earlier research failed to study or products that failed to meet user needs.

3. Keep your audience in mind

Is your audience interested in the particular field you want to study? Are the research questions in your mind appealing and interesting to the audience? Defining your audience will help you refine your research question and ensure you pick a question that is relatable to your audience.

4. Generate a list of potential questions

Ask yourself numerous open-ended questions on the topic to create a potential list of research questions. You could start with broader questions and narrow them down to more specific ones. Don’t forget that you can challenge existing assumptions or use personal experiences to redefine research issues.

5. Review the questions

Evaluate your list of potential questions to determine which seems most effective. Ensure you consider the finer details of every question and possible outcomes. Doing this helps you determine if the questions meet the requirements of a research question.

6. Construct and evaluate your research question

Consider these two frameworks when constructing a good research question: PICOT and PEO.

PICOT stands for:

P: Problem or population

I: Indicator or intervention to be studied

C: Comparison groups

O: Outcome of interest

T: Time frame

PEO stands for:

P: Population being studied

E: Exposure to any preexisting conditions

To evaluate your research question once you’ve constructed it, ask yourself the following questions:

Is it clear?

Your study should produce precise data and observations. For qualitative studies, the observations need to be delineable across categories. Quantitative studies must have measurable and empirical data.

Is it specific and focused?

An excellent research question must be specific enough to ensure your testing yields objective results. General or open-ended research questions are often ambiguous and subject to different kinds of interpretation.

Is it sufficiently complex?

Your research needs to yield substantial and consequential results to warrant the study. Merely supporting or reinforcing an existing paper is not good enough.

- Examples of good research questions

A robust research question actively contributes to a specific body of knowledge; it is a question that hasn’t been answered before within your research field.

Here are some examples of good and bad research questions :

Good: How effective are A and B policies at reducing the rates of Z?

Bad: Is A or B a better policy?

The first is more focused and researchable because it isn't based on value judgment. The second fails to give clear criteria for answering the question.

Good: What is the effect of daily Twitter use on the attention span of college students?

Bad: What is the effect of social media use on people's minds?

The first includes specific and well-defined concepts, which the second lacks.

Ensure all terms within your research question have precise meanings. Avoid vague or general language that makes the topic too broad.

- The bottom line

The success of any research starts with formulating the right questions that ensure you collect the most insightful data. A good research question will showcase the objectives of your systematic investigation and emphasize specific contexts.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

- Introduction

Why are research questions so important?

Research question examples, types of qualitative research questions, writing a good research question, guiding your research through research questions.

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

- Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

- Case studies

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Research questions

The research question plays a critical role in the research process, as it guides the study design, data collection , analysis , and interpretation of the findings.

A research paper relies on a research question to inform readers of the research topic and the research problem being addressed. Without such a question, your audience may have trouble understanding the rationale for your research project.

People can take for granted the research question as an essential part of a research project. However, explicitly detailing why researchers need a research question can help lend clarity to the research project. Here are some of the key roles that the research question plays in the research process:

Defines the scope and focus of the study

The research question helps to define the scope and focus of the study. It identifies the specific topic or issue that the researcher wants to investigate, and it sets the boundaries for the study. A research question can also help you determine if your study primarily contributes to theory or is more applied in nature. Clinical research and public health research, for example, may be more concerned with research questions that contribute to practice, while a research question focused on cognitive linguistics are aimed at developing theory.

Provides a rationale for the study

The research question provides a rationale for the study by identifying a gap or problem in existing literature or practice that the researcher wants to address. It articulates the purpose and significance of the study, and it explains why the study is important and worth conducting.

Guides the study design

The research question guides the study design by helping the researcher select appropriate research methods , sampling strategies, and data collection tools. It also helps to determine the types of data that need to be collected and the best ways to analyze and interpret the data because the principal aim of the study is to provide an answer to that research question.

Shapes the data analysis and interpretation

The research question shapes the data analysis and interpretation by guiding the selection of appropriate analytical methods and by focusing the interpretation of the findings. It helps to identify which patterns and themes in the data are more relevant and worth digging into, and it guides the development of conclusions and recommendations based on the findings.

Generates new knowledge

The research question is the starting point for generating new knowledge. By answering the research question, the researcher contributes to the body of knowledge in the field and helps to advance the understanding of the topic or issue under investigation.

Overall, the research question is a critical component of the research process, as it guides the study from start to finish and provides a foundation for generating new knowledge.

Supports the thesis statement

The thesis statement or main assertion in any research paper stems from the answers to the research question. As a result, you can think of a focused research question as a preview of what the study aims to present as a new contribution to existing knowledge.

Here area few examples of focused research questions that can help set the stage for explaining different types of research questions in qualitative research . These questions touch upon various fields and subjects, showcasing the versatility and depth of research.

- What factors contribute to the job satisfaction of remote workers in the technology industry?

- How do teachers perceive the implementation of technology in the classroom, and what challenges do they face?

- What coping strategies do refugees use to deal with the challenges of resettlement in a new country?

- How does gentrification impact the sense of community and identity among long-term residents in urban neighborhoods?

- In what ways do social media platforms influence body image and self-esteem among adolescents?

- How do family dynamics and communication patterns affect the management of type 2 diabetes in adult patients?

- What is the role of mentorship in the professional development and career success of early-career academics?

- How do patients with chronic illnesses experience and navigate the healthcare system, and what barriers do they encounter?

- What are the motivations and experiences of volunteers in disaster relief efforts, and how do these experiences impact their future involvement in humanitarian work?

- How do cultural beliefs and values shape the consumer preferences and purchasing behavior of young adults in a globalized market?

- How do individuals whose genetic factors predict a high risk for developing a specific medical condition perceive, cope with, and make lifestyle choices based on this information?

These example research questions highlight the different kinds of inquiries common to qualitative research. They also demonstrate how qualitative research can address a wide range of topics, from understanding the experiences of specific populations to examining the impact of broader social and cultural phenomena.

Also, notice that these types of research questions tend to be geared towards inductive analyses that describe a concept in depth or develop new theory. As such, qualitative research questions tend to ask "what," "why," or "how" types of questions. This contrasts with quantitative research questions that typically aim to verify an existing theory. and tend to ask "when," "how much," and "why" types of questions to nail down causal mechanisms and generalizable findings.

Whatever your research inquiry, turn to ATLAS.ti

Powerful tools to help turn your research question into meaningful analysis, starting with a free trial.

As you can see above, the research questions you ask play a critical role in shaping the direction and depth of your study. These questions are designed to explore, understand, and interpret social phenomena, rather than testing a hypothesis or quantifying data like in quantitative research. In this section, we will discuss the various types of research questions typically found in qualitative research, making it easier for you to craft appropriate questions for your study.

Descriptive questions

Descriptive research questions aim to provide a detailed account of the phenomenon being studied. These questions usually begin with "what" or "how" and seek to understand the nature, characteristics, or functions of a subject. For example, "What are the experiences of first-generation college students?" or "How do small business owners adapt to economic downturns?"

Comparative questions

Comparative questions seek to examine the similarities and differences between two or more groups, cases, or phenomena. These questions often include the words "compare," "contrast," or "differences." For example, "How do parenting practices differ between single-parent and two-parent families?" or "What are the similarities and differences in leadership styles among successful female entrepreneurs?"

Exploratory questions

Exploratory research questions are open-ended and intended to investigate new or understudied areas. These questions aim to identify patterns, relationships, or themes that may warrant further investigation. For example, "How do teenagers use social media to construct their identities?" or "What factors influence the adoption of renewable energy technologies in rural communities?"

Explanatory questions

Explanatory research questions delve deeper into the reasons or explanations behind a particular phenomenon or behavior. They often start with "why" or "how" and aim to uncover underlying motivations, beliefs, or processes. For example, "Why do some employees resist organizational change?" or "How do cultural factors influence decision-making in international business negotiations?"

Evaluative questions

Evaluative questions assess the effectiveness, impact, or outcomes of a particular intervention, program, or policy. They seek to understand the value or significance of an initiative by examining its successes, challenges, or unintended consequences. For example, "How effective is the school's anti-bullying program in reducing incidents of bullying?" or "What are the long-term impacts of a community-based health promotion campaign on residents' well-being?"

Interpretive questions

Interpretive questions focus on understanding how individuals or groups make sense of their experiences, actions, or social contexts. These questions often involve the analysis of language, symbols, or narratives to uncover the meanings and perspectives that shape human behavior. For example, "How do cancer survivors make sense of their illness journey?" or "What meanings do members of a religious community attach to their rituals and practices?"

There are mainly two overarching ways to think about how to devise a research question. Many studies are built on existing research, but others can be founded on personal experiences or pilot research.

Using the literature review

Within scholarly research, the research question is often built from your literature review . An analysis of the relevant literature reporting previous studies should allow you to identify contextual, theoretical, or methodological gaps that can be addressed in future research.

A compelling research question built on a robust literature review ultimately illustrates to your audience what is novel about your study's objectives.

Conducting pilot research

Researchers may conduct preliminary research or pilot research when they are interested in a particular topic but don't yet have a basis for forming a research question on that topic. A pilot study is a small-scale, preliminary study that is conducted in order to test the feasibility of a research design, methods, and procedures. It can help identify unresolved puzzles that merit further investigation, and pilot studies can draw attention to potential issues or problems that may arise in the full study.

One potential benefit of conducting a pilot study in qualitative research is that it can help the researcher to refine their research question. By collecting and analyzing a small amount of data, the researcher can get a better sense of the phenomenon under investigation and can develop a more focused and refined research question for the full study. The pilot study can also help the researcher to identify key themes, concepts, or variables that should be included in the research question.

In addition to helping to refine the research question, a pilot study can also help the researcher to develop a more effective data collection and analysis plan. The researcher can test different methods for collecting and analyzing data, and can make adjustments based on the results of the pilot study. This can help to ensure that the full study is conducted in the most effective and efficient manner possible.

Overall, conducting a pilot study in qualitative research can be a valuable tool for refining the research question and developing a more effective research design, methods, and procedures. It can help to ensure that the full study is conducted in a rigorous and effective manner, and can increase the likelihood of generating meaningful and useful findings.

When you write a research question for your qualitative study, consider which type of question best aligns with your research objectives and the nature of the phenomenon you are investigating. Remember, qualitative research questions should be open-ended, allowing for a range of perspectives and insights to emerge. As you progress in your research, these questions may evolve or be refined based on the data you collect, helping to guide your analysis and deepen your understanding of the topic.

Use ATLAS.ti for every step of your research project

From the research question to the key insights, ATLAS.ti is there for you. See how with a free trial.

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- Product Demos

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Qualitative Research Questions

Try Qualtrics for free

How to write qualitative research questions.

11 min read Here’s how to write effective qualitative research questions for your projects, and why getting it right matters so much.

What is qualitative research?

Qualitative research is a blanket term covering a wide range of research methods and theoretical framing approaches. The unifying factor in all these types of qualitative study is that they deal with data that cannot be counted. Typically this means things like people’s stories, feelings, opinions and emotions , and the meanings they ascribe to their experiences.

Qualitative study is one of two main categories of research, the other being quantitative research. Quantitative research deals with numerical data – that which can be counted and quantified, and which is mostly concerned with trends and patterns in large-scale datasets.

What are research questions?

Research questions are questions you are trying to answer with your research. To put it another way, your research question is the reason for your study, and the beginning point for your research design. There is normally only one research question per study, although if your project is very complex, you may have multiple research questions that are closely linked to one central question.

A good qualitative research question sums up your research objective. It’s a way of expressing the central question of your research, identifying your particular topic and the central issue you are examining.

Research questions are quite different from survey questions, questions used in focus groups or interview questions. A long list of questions is used in these types of study, as opposed to one central question. Additionally, interview or survey questions are asked of participants, whereas research questions are only for the researcher to maintain a clear understanding of the research design.

Research questions are used in both qualitative and quantitative research , although what makes a good research question might vary between the two.

In fact, the type of research questions you are asking can help you decide whether you need to take a quantitative or qualitative approach to your research project.

Discover the fundamentals of qualitative research

Quantitative vs. qualitative research questions

Writing research questions is very important in both qualitative and quantitative research, but the research questions that perform best in the two types of studies are quite different.

Quantitative research questions

Quantitative research questions usually relate to quantities, similarities and differences.

It might reflect the researchers’ interest in determining whether relationships between variables exist, and if so whether they are statistically significant. Or it may focus on establishing differences between things through comparison, and using statistical analysis to determine whether those differences are meaningful or due to chance.

- How much? This kind of research question is one of the simplest. It focuses on quantifying something. For example:

How many Yoruba speakers are there in the state of Maine?

- What is the connection?

This type of quantitative research question examines how one variable affects another.

For example:

How does a low level of sunlight affect the mood scores (1-10) of Antarctic explorers during winter?

- What is the difference? Quantitative research questions in this category identify two categories and measure the difference between them using numerical data.

Do white cats stay cooler than tabby cats in hot weather?

If your research question fits into one of the above categories, you’re probably going to be doing a quantitative study.

Qualitative research questions

Qualitative research questions focus on exploring phenomena, meanings and experiences.

Unlike quantitative research, qualitative research isn’t about finding causal relationships between variables. So although qualitative research questions might touch on topics that involve one variable influencing another, or looking at the difference between things, finding and quantifying those relationships isn’t the primary objective.

In fact, you as a qualitative researcher might end up studying a very similar topic to your colleague who is doing a quantitative study, but your areas of focus will be quite different. Your research methods will also be different – they might include focus groups, ethnography studies, and other kinds of qualitative study.

A few example qualitative research questions:

- What is it like being an Antarctic explorer during winter?

- What are the experiences of Yoruba speakers in the USA?

- How do white cat owners describe their pets?

Qualitative research question types

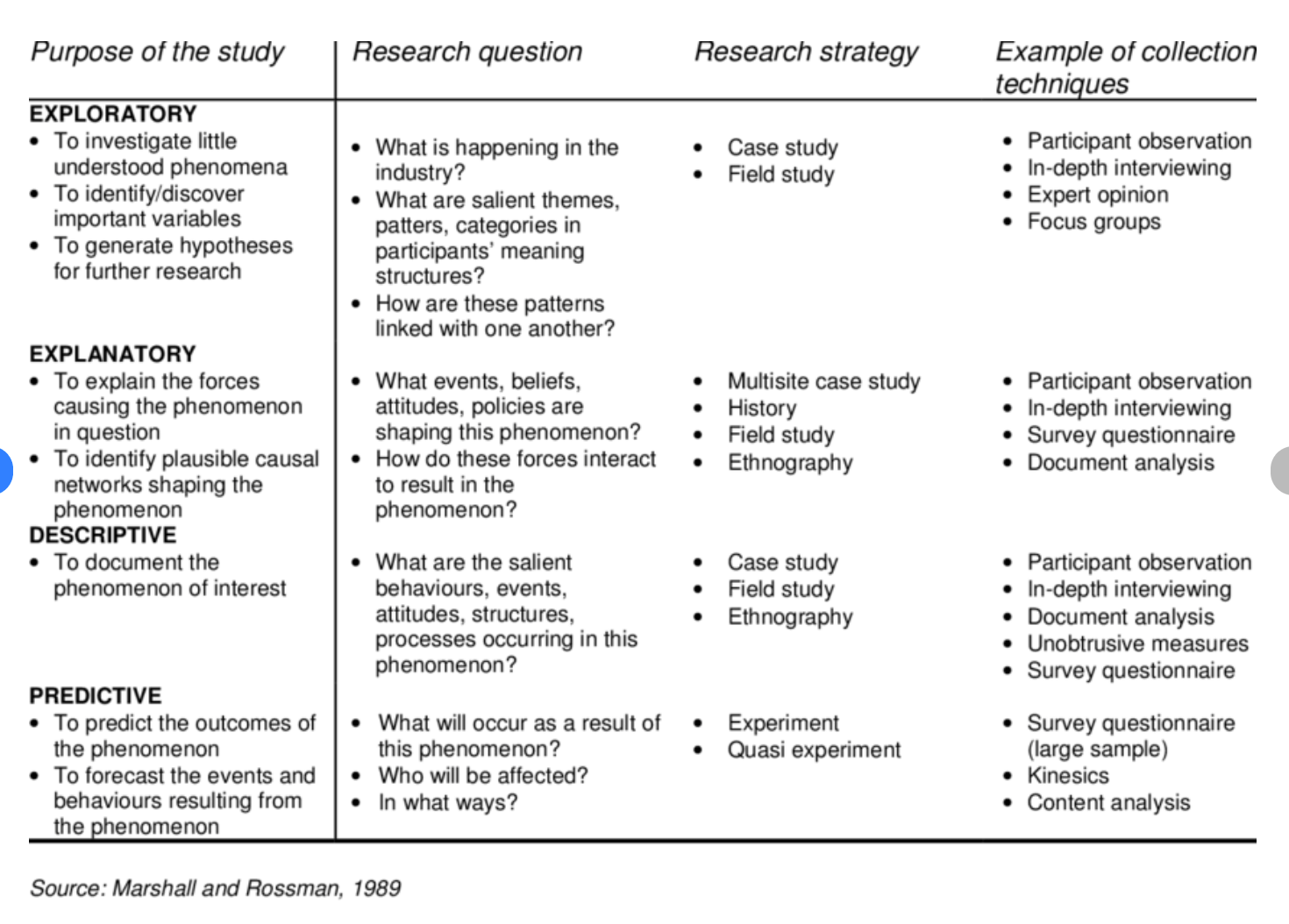

Marshall and Rossman (1989) identified 4 qualitative research question types, each with its own typical research strategy and methods.

- Exploratory questions

Exploratory questions are used when relatively little is known about the research topic. The process researchers follow when pursuing exploratory questions might involve interviewing participants, holding focus groups, or diving deep with a case study.

- Explanatory questions

With explanatory questions, the research topic is approached with a view to understanding the causes that lie behind phenomena. However, unlike a quantitative project, the focus of explanatory questions is on qualitative analysis of multiple interconnected factors that have influenced a particular group or area, rather than a provable causal link between dependent and independent variables.

- Descriptive questions

As the name suggests, descriptive questions aim to document and record what is happening. In answering descriptive questions , researchers might interact directly with participants with surveys or interviews, as well as using observational studies and ethnography studies that collect data on how participants interact with their wider environment.

- Predictive questions

Predictive questions start from the phenomena of interest and investigate what ramifications it might have in the future. Answering predictive questions may involve looking back as well as forward, with content analysis, questionnaires and studies of non-verbal communication (kinesics).

Why are good qualitative research questions important?

We know research questions are very important. But what makes them so essential? (And is that question a qualitative or quantitative one?)

Getting your qualitative research questions right has a number of benefits.

- It defines your qualitative research project Qualitative research questions definitively nail down the research population, the thing you’re examining, and what the nature of your answer will be.This means you can explain your research project to other people both inside and outside your business or organization. That could be critical when it comes to securing funding for your project, recruiting participants and members of your research team, and ultimately for publishing your results. It can also help you assess right the ethical considerations for your population of study.

- It maintains focus Good qualitative research questions help researchers to stick to the area of focus as they carry out their research. Keeping the research question in mind will help them steer away from tangents during their research or while they are carrying out qualitative research interviews. This holds true whatever the qualitative methods are, whether it’s a focus group, survey, thematic analysis or other type of inquiry.That doesn’t mean the research project can’t morph and change during its execution – sometimes this is acceptable and even welcome – but having a research question helps demarcate the starting point for the research. It can be referred back to if the scope and focus of the project does change.

- It helps make sure your outcomes are achievable

Because qualitative research questions help determine the kind of results you’re going to get, it helps make sure those results are achievable. By formulating good qualitative research questions in advance, you can make sure the things you want to know and the way you’re going to investigate them are grounded in practical reality. Otherwise, you may be at risk of taking on a research project that can’t be satisfactorily completed.

Developing good qualitative research questions

All researchers use research questions to define their parameters, keep their study on track and maintain focus on the research topic. This is especially important with qualitative questions, where there may be exploratory or inductive methods in use that introduce researchers to new and interesting areas of inquiry. Here are some tips for writing good qualitative research questions.

1. Keep it specific

Broader research questions are difficult to act on. They may also be open to interpretation, or leave some parameters undefined.

Strong example: How do Baby Boomers in the USA feel about their gender identity?

Weak example: Do people feel different about gender now?

2. Be original

Look for research questions that haven’t been widely addressed by others already.

Strong example: What are the effects of video calling on women’s experiences of work?

Weak example: Are women given less respect than men at work?

3. Make it research-worthy

Don’t ask a question that can be answered with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’, or with a quick Google search.

Strong example: What do people like and dislike about living in a highly multi-lingual country?

Weak example: What languages are spoken in India?

4. Focus your question

Don’t roll multiple topics or questions into one. Qualitative data may involve multiple topics, but your qualitative questions should be focused.

Strong example: What is the experience of disabled children and their families when using social services?

Weak example: How can we improve social services for children affected by poverty and disability?

4. Focus on your own discipline, not someone else’s

Avoid asking questions that are for the politicians, police or others to address.

Strong example: What does it feel like to be the victim of a hate crime?

Weak example: How can hate crimes be prevented?

5. Ask something researchable

Big questions, questions about hypothetical events or questions that would require vastly more resources than you have access to are not useful starting points for qualitative studies. Qualitative words or subjective ideas that lack definition are also not helpful.

Strong example: How do perceptions of physical beauty vary between today’s youth and their parents’ generation?

Weak example: Which country has the most beautiful people in it?

Related resources

Qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, business research methods 12 min read, qualitative research interviews 11 min read, market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Good Research Question (w/ Examples)

What is a Research Question?

A research question is the main question that your study sought or is seeking to answer. A clear research question guides your research paper or thesis and states exactly what you want to find out, giving your work a focus and objective. Learning how to write a hypothesis or research question is the start to composing any thesis, dissertation, or research paper. It is also one of the most important sections of a research proposal .

A good research question not only clarifies the writing in your study; it provides your readers with a clear focus and facilitates their understanding of your research topic, as well as outlining your study’s objectives. Before drafting the paper and receiving research paper editing (and usually before performing your study), you should write a concise statement of what this study intends to accomplish or reveal.

Research Question Writing Tips

Listed below are the important characteristics of a good research question:

A good research question should:

- Be clear and provide specific information so readers can easily understand the purpose.

- Be focused in its scope and narrow enough to be addressed in the space allowed by your paper

- Be relevant and concise and express your main ideas in as few words as possible, like a hypothesis.

- Be precise and complex enough that it does not simply answer a closed “yes or no” question, but requires an analysis of arguments and literature prior to its being considered acceptable.

- Be arguable or testable so that answers to the research question are open to scrutiny and specific questions and counterarguments.

Some of these characteristics might be difficult to understand in the form of a list. Let’s go into more detail about what a research question must do and look at some examples of research questions.

The research question should be specific and focused

Research questions that are too broad are not suitable to be addressed in a single study. One reason for this can be if there are many factors or variables to consider. In addition, a sample data set that is too large or an experimental timeline that is too long may suggest that the research question is not focused enough.

A specific research question means that the collective data and observations come together to either confirm or deny the chosen hypothesis in a clear manner. If a research question is too vague, then the data might end up creating an alternate research problem or hypothesis that you haven’t addressed in your Introduction section .

| What is the importance of genetic research in the medical field? | |

| How might the discovery of a genetic basis for alcoholism impact triage processes in medical facilities? |

The research question should be based on the literature

An effective research question should be answerable and verifiable based on prior research because an effective scientific study must be placed in the context of a wider academic consensus. This means that conspiracy or fringe theories are not good research paper topics.

Instead, a good research question must extend, examine, and verify the context of your research field. It should fit naturally within the literature and be searchable by other research authors.

References to the literature can be in different citation styles and must be properly formatted according to the guidelines set forth by the publishing journal, university, or academic institution. This includes in-text citations as well as the Reference section .

The research question should be realistic in time, scope, and budget

There are two main constraints to the research process: timeframe and budget.

A proper research question will include study or experimental procedures that can be executed within a feasible time frame, typically by a graduate doctoral or master’s student or lab technician. Research that requires future technology, expensive resources, or follow-up procedures is problematic.

A researcher’s budget is also a major constraint to performing timely research. Research at many large universities or institutions is publicly funded and is thus accountable to funding restrictions.

The research question should be in-depth

Research papers, dissertations and theses , and academic journal articles are usually dozens if not hundreds of pages in length.

A good research question or thesis statement must be sufficiently complex to warrant such a length, as it must stand up to the scrutiny of peer review and be reproducible by other scientists and researchers.

Research Question Types

Qualitative and quantitative research are the two major types of research, and it is essential to develop research questions for each type of study.

Quantitative Research Questions

Quantitative research questions are specific. A typical research question involves the population to be studied, dependent and independent variables, and the research design.