Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 09 May 2024

Detecting causal relationships between work motivation and job performance: a meta-analytic review of cross-lagged studies

- Nan Wang 1 na1 ,

- Yuxiang Luan 2 na1 &

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 595 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

852 Accesses

Metrics details

Given that competing hypotheses about the causal relationship between work motivation and job performance exist, the current research utilized meta-analytic structural equation modeling (MASEM) methodology to detect the causal relationships between work motivation and job performance. In particular, completing hypotheses were checked by applying longitudinal data that include 84 correlations ( n = 4389) from 11 independent studies measuring both work motivation and job performance over two waves. We find that the effect of motivation (T1) on performance (T2), with performance (T1) controlled, was positive and significant ( β = 0.143). However, the effect of performance (T1) on motivation (T2), with motivation (T1) controlled, was not significant. These findings remain stable and robust across different measures of job performance (task performance versus organizational citizenship behavior), different measures of work motivation (engagement versus other motivations), and different time lags (1–6 months versus 7–12 months), suggesting that work motivation is more likely to cause job performance than vice versa. Practical and theoretical contributions are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Psychosocial work environment as a dynamic network: a multi-wave cohort study

Predicting organizational performance from motivation in Oromia Seed Enterprise Bale branch

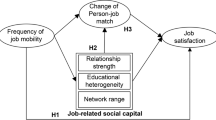

Role of job mobility frequency in job satisfaction changes: the mediation mechanism of job-related social capital and person‒job match

Introduction.

Job performance is defined as “scalable actions, behavior, and outcomes that employees engage in or bring about that are linked with and contribute to organizational goals” (Viswesvaran and Ones, 2000 , p. 216), is a core concept in the applied psychological field (Campbell and Wiernik, 2015 ; Choi et al., 2022 ; Giancaspro et al., 2022 ; Hermanto and Srimulyani, 2022 ; Motowidlo, 2003 ). Employees’ job performance is important for both organization and the employee. For an organization, job performance is the vital antecedent of organizational performance (Almatrooshi et al., 2016 ); for an employee, job performance is a predictor of turnover (Bycio et al., 1990 ; Martin et al., 1981 ), and wellbeing (Bakker and Oerlemans, 2011 ; Ford et al., 2011 ). Considering the importance of job performance in the applied psychological field, it is not surprising that researchers have devoted significant effort to researching job performance, especially its antecedents.

Prior meta-analyses identified a series of antecedents of job performance, such as job satisfaction (Iaffaldano and Muchinsky, 1985 ; Judge et al., 2001 ; LePine et al., 2002 ), organizational commitment (Jaramillo et al., 2005 ; Mathieu and Zajac, 1990 ), and work motivation (Cerasoli et al., 2014 ; Van den Broeck et al., 2021 ; Van Iddekinge et al., 2018 ). Among these factors, motivation, which refers to the force that drives the direction, intensity, and persistence of employee behavior (Pinder, 2014 ), is a medium to strong predictor of performance (Cerasoli et al. 2014 ). Although the early meta-analyses (e.g., Cerasoli et al., 2014 ; Van Iddekinge et al., 2018 ) confirmed the significant correlations between work motivation and job performance, the accurate causal relationship between work motivation and job performance remains unclear. Does work motivation cause job performance? Does reverse causality exist? Or there is a reciprocal relationship between them? Unfortunately, previous meta-analyses (e.g., Cerasoli et al., 2014 ; Van Iddekinge et al., 2018 ), which are based on cross-temporal data rather than longitudinal cross-lagged panel data, could not address this research gap.

We propose four competing hypotheses to explain the causal relationship between them. First, work motivation causes job performance. Second, job performance causes work motivation. Third, work motivation causes job performance and vice versa (reciprocal model). Finally, work motivation and job performance are causally unrelated. In the Theory and Hypotheses part, we will describe these hypotheses in detail.

By checking all four hypotheses, the current study aims to reveal the causal relationship between work motivation and job performance. A single primary study could not accomplish our research goal due to the distorting of statistical artifacts (e.g., sampling error and measurement error; Hunter and Schmidt, 2004 ). For instance, the relationships of interest may vary when sampling from different organizations because of sampling error, which would harm the accuracy of the results. Fortunately, the meta-analysis methodology could help us to correct the statistical artifacts and thereby provide solid and reliable empirical evidence for the theory. As such, we utilize a meta-analysis methodology that allows us to aggregate cross-lagged panel data to test the four hypotheses.

This article provides the first meta-analysis that estimates the longitudinal effects between work motivation and job performance, contributing to both theory and practice. In terms of theory, this study will provide solid evidence for the causal relationship between work motivation and job performance, contributing to motivation and performance literature. In relation to practice, the results of our study will provide guidance for human resource management. For instance, if we find that motivation causes performance, using human resource practice (e.g., performance appraisal and training) that will influence motivation to improve performance will be reasonable; whereas if other results were found, perhaps we will reconsider the effectiveness of the current human resource practices.

Theory and hypotheses

In this part, we will review work motivation and job performance and their measurements. Then, we will develop the hypotheses between them. Finally, as a meta-analysis, we will propose a research question about the moderators that might influence the relationships between motivation and performance.

Before the 1970s, organizational psychologists primarily directed their attention toward job satisfaction, often sidelining the exploration of work performance (Organ, 2018 ). However, the tide turned in the 1980s, when scholars began conceptualizing individual job performance as a distinct construct (Campbell and Wiernik, 2015 ). Job performance is commonly characterized by two key forms: task performance and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), providing a structured framework for evaluating employee contributions (Hoffman et al., 2007 ; Sidorenkov and Borokhovski, 2021 ; Young et al., 2021 ). Notably, performance should not be conflated with efficiency and productivity. While performance encompasses a broader term, often associated with achieving various levels or outcomes potentially under myriad conditions, both efficiency and productivity are intricately tied to the concept of optimizing resource utilization and maximizing output production (Campbell and Wiernik, 2015 ).

Task performance refers to the effectiveness with which job incumbents perform activities that contribute to the organization’s technical core (Borman and Motowidlo, 1997 , p. 99). Notably, this concept is also identified as “in-role performance/behavior” in the literature (Koopmans et al., 2011 ; Raja and Johns, 2010 ). In-role performance essentially encapsulates behaviors aimed at fulfilling formal tasks, duties, and responsibilities, often detailed in job descriptions (Becker and Kernan, 2003 ; Williams and Anderson, 1991 ). Contrarily, early meta-analyses have amalgamated related concepts, acknowledging their overlapping domains (Riketta, 2008 ; Young et al., 2021 ). OCB is delineated as “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization” (Organ, 1988 , p. 4). Contextual performance, reflecting actions extending beyond formal job descriptions and enhancing organizational effectiveness (MacKenzie et al., 1991 ), is frequently paralleled with OCB in meta-analytic practices (Riketta, 2008 ; Young et al., 2021 ). A noteworthy correlation between task performance and OCB (ρ = 0.74) is illuminated through a meta-analysis by Hoffman et al. ( 2007 ). While some scholars propose that performance can exhibit counterproductive facets (Campbell and Wiernik, 2015 ), meta-analysis unveils only a moderate relationship between OCB and counterproductive work behavior and reveals somewhat disparate relationship patterns with their antecedents (Dalal, 2005 ). Therefore, in this study, we study two fundamental dimensions of job performance: task performance and OCB.

Motivation reflects why people do something. It is widely researched in the work and educational psychological field (Anesukanjanakul et al., 2019 ; Christenson et al., 2012 ; Fishbach and Woolley, 2022 ; Hartinah et al., 2020 ; Muawanah et al., 2020 ). Work motivation stands distinct amidst a spectrum of related concepts. Firstly, it is imperative to differentiate motivation from personality. Personality, defined as a construct embodying a set of “traits and styles displayed by an individual, represents (a) dispositions, that is, natural tendencies or personal inclinations of the person, and (b) aspects wherein the individual deviates from the ‘standard normal person’ in their society” (Bergner, 2020 , p.4). Personality acts as a distal antecedent to performance, influencing it indirectly through the medium of motivation (Judge and Ilies, 2002 ; Kanfer et al., 2017 ). Secondly, while interrelated, goal pursuit and motivation are distinctive concepts. For example, if employees aim to earn money, their motivations are characterized as external. Conversely, intrinsically motivated employees engage in work for the enjoyment derived from the process itself, potentially without being driven by explicit work goals (Deci et al., 2017 ). Thirdly, motivation is different from attitude. Job attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction) reflect the evaluations of one’s job (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012 ). Motivation may not necessarily include the evaluation of the job. For instance, engaged people, who usually put a great deal of effort into their work (Bakker et al., 2014 ), may not include the evaluation of the job. Actually, attitudes may likely be influenced by motivations, indicating they are different concepts (Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller, 2012 ).

As work motivation is a very grand concept, many psychological and organizational theories try to measure motivation by using different scales. For instance, in the perspective of the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) Theory (Bakker, 2011 ; Bakker and Demerouti, 2017 ), work engagement is regarded as the motivation factor that links job resources and job performance; in the perspective of the Self-determination Theory (SDT), motivation (e.g., intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation) is the antecedent of job performance (Deci et al., 2017 ; Deci and Ryan, 2000 ). In the review process, we notice that work engagement is one of the most widely-used measurements of motivation when researching the work motivation-job performance linkage.

Hypotheses between motivation and performance

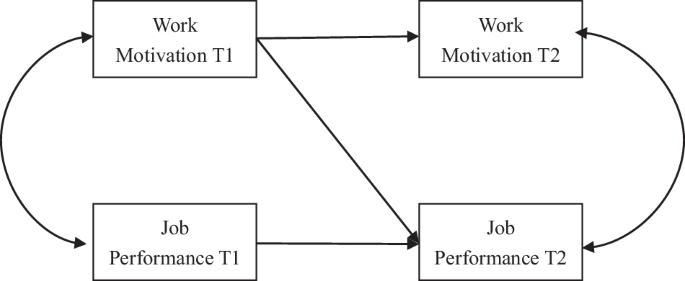

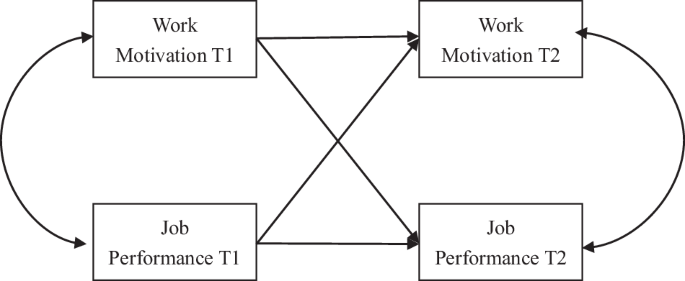

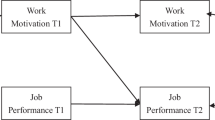

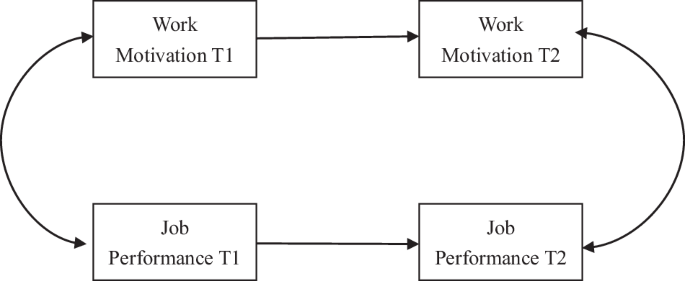

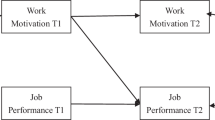

The first potential causal relationship is that work motivation causes job performance. This argument is shown in Fig. 1 . This Argument is supported by many well-established theories and empirical evidence. To start, in the JD-R theory (Bakker, 2011 ; Bakker and Demerouti, 2007 ; Bakker and Demerouti, 2017 ), engaged (well-motivated) people will accomplish job performance because they will experience more positive emotions which may increase the creation of new ideas and resources and they will be healthy and be energetic at work. The correlational relationship was confirmed by a prior meta-analysis as it found a medium correlation ( ρ = 0.48) between engagement and job performance (Neuber et al., 2021 ). Then, from the perspective of SDT (Deci et al., 2017 ; Deci and Ryan, 2000 ; Gagné and Deci, 2005 ), motivation also influences performance. In particular, intrinsically motivated employees will be creative and productive, increasing their job performance. An early meta-analysis finds a moderate correlation between intrinsic motivation and performance ( ρ = 0.28) (Cerasoli et al., 2014 ). Finally, motivation may influence performance directly by determining the level of effort and persistence an individual will exert in the face of obstacles (Kanfer, 1990 ). Motivation may also influence performance indirectly, as motivated individuals are more likely to set challenging goals and commit to achieving them, leading to higher performance (Locke and Latham, 2006 ). Together, it seems obvious that work motivation will cause subsequent job performance. When using the cross-lagged panel research design to test this hypothesis, the subsequent performance will be predicted by the previous motivation after controlling the auto-correlation effect. As such, the following hypothesis is proposed:

An illustration of arguments for a “motivation-causing-performance” process. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Hypothesis 1 : Work motivation causes job performance. In particular, work motivation (T1) is the significant predictor of job performance (T2) after controlling the auto-correlation effect of job performance (T1).

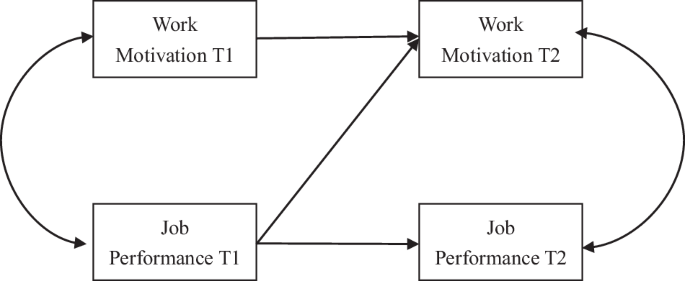

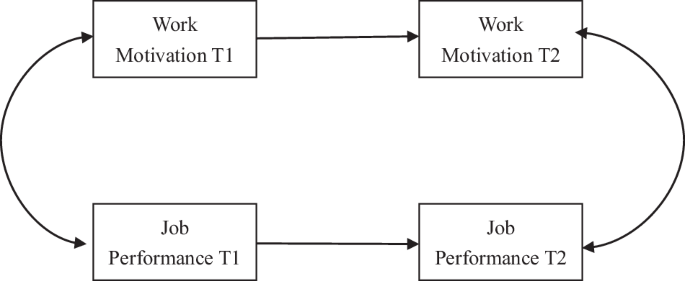

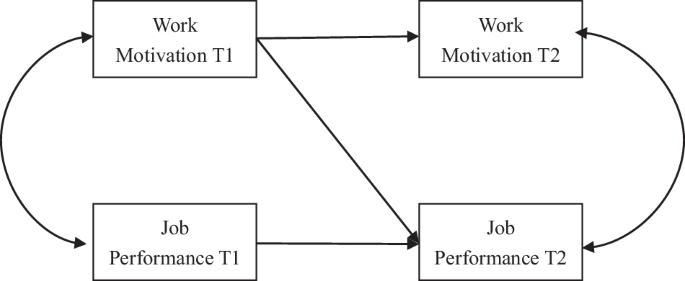

As illustrated in Fig. 2 , the second potential causal relationship is that performance causes motivation. As SDT suggested, feedback will influence motivation (Deci et al., 1999 ). Employees who achieve job performance may receive positive feedback (e.g., pay and recognition) from their organizations and leaders (Riketta, 2008 ), increasing their work motivation. Applying longitudinal data, Presbitero ( 2017 ) provided indirect evidence that improvements in reward management yielded a positive change in the level of motivation (measured by engagement). Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

An illustration of arguments for a “performance-causing-motivation” process. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Hypothesis 2 : Job performance causes work motivation. In particular, job performance (T1) is the significant predictor of work motivation (T2) after controlling the auto-correlation effect of work motivation (T1).

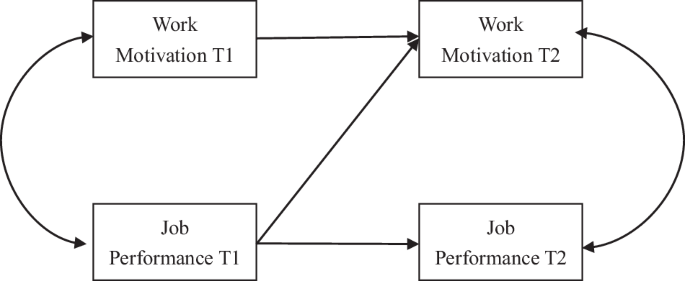

According to Fig. 3 , the third hypothesis is that motivation causes performance and performance causes motivation simultaneously. Combining Hypotheses 1 and 2, we could conclude this reciprocal hypothesis. Utilizing cross-lagged panel data, early studies found reciprocal relationships between (a) self-efficacy and academic performance (Talsma et al., 2018 ) and (b) job characteristics and emotional exhaustion (Konze et al., 2017 ). That is to say, there might be a reciprocal relationship between variables. Thus, we derive the following hypotheses:

An illustration of arguments for a simultaneous reciprocity between work motivation and job performance. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Hypothesis 3 : There is a reciprocal causal relationship between work motivation and job performance. In particular, work motivation (T1) is the significant predictor of job performance (T2) after controlling the auto-correlation effect of job performance (T1) and vice versa.

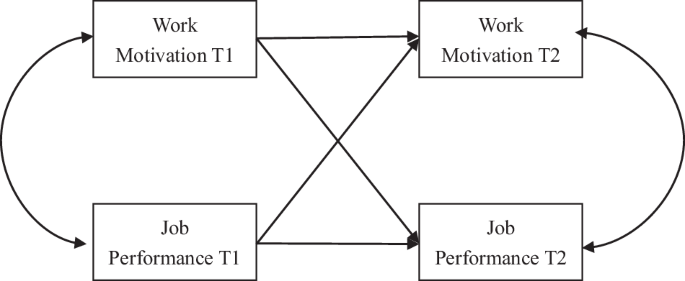

As presented in Fig. 4 , the final potential causal relationship is that performance and motivation are causally unrelated. Performance and motivation may be causally unrelated due to cross-temporal research design and common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003 ). For instance, when work motivation and job performance are measured at the same time point and rated by one person, their correlation may inflate due to common method bias and thereby draw inaccurate causality. Therefore, we put the following hypothesis:

An illustration of arguments for a causally unrelated relationship between work motivation and job performance. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Hypothesis 4 : Work motivation and job performance are causally unrelated. In particular, work motivation (T1) is not a significant predictor of job performance (T2) after controlling the auto-correlation effect of job performance (T1), whereas job performance (T1) is also not the significant predictor of work motivation (T2) after controlling the auto-correlation effect of work motivation (T1).

We also propose a research question about the potential moderators that may influence the relationship of interest. Following early longitudinal meta-analyses (Riketta, 2008 ; Talsma et al., 2018 ), three moderators are considered, namely, performance measurements, motivation measurements, and length of time lag (shorter vs. longer time lags between two waves).

Firstly, as we illustrated in the Introduction part, there are two measurements of work performance, namely, task performance and OCB. We would like to explore the potential moderating role of job performance measurements (task performance versus OCB). This exploration is pivotal. Theoretically, performance should envelop two dimensions: task performance and OCB (Koopmans et al., 2011 ). However, a disparity exists in organizational recognition and reward systems, wherein task performance is formally acknowledged, while OCB is not (Organ, 2018 ). The impact of such discrepancies on their respective relationships with performance remains nebulous. Undertaking a meta-analysis to probe into these moderating variables will not only deepen our understanding of the nexus between motivation and performance but also furnish supplementary evidence to buttress their interconnection.

Secondly, the motivation measurement is taken into consideration. In particular, many longitudinal studies (e.g., Shimazu et al., 2018 ; Nawrocka et al., 2021 ) use work engagement to measure motivation. Although theoretical frameworks suggest that these measures might reflect motivation, various measures of motivation may exhibit distinct relationships with performance. Despite the absence of cross-lagged meta-analyses, insights can potentially be derived from cross-temporal meta-analyses. For example, Cerasoli et al. ( 2014 ) identified a correlation of 0.26 between intrinsic motivation and performance, while Corbeanu and Iliescu ( 2023 ) observed a correlation of 0.37 between work engagement and performance. Consequently, we question whether the measurement of motivation exerts a significant moderating effect. Given that work engagement is the most prevalently utilized measure, we draw comparisons between the results pertaining to work engagement and those associated with other forms of motivation.

Finally, it is unclear how long the time lag process (i.e., the length of time between two measurement waves) will influence the relationship of interest. In the present study, time lags varied from 1 to 12 months (refer to the coding information for details). On the one hand, the relationship between motivation and performance may depend on time. For instance, even with strong motivation, employees may require time to learn and adapt to new tasks, affecting performance enhancement. Furthermore, the delay in receiving feedback or recognition, especially in long-term projects, may decelerate the positive influence of performance on motivation.

On the other hand, there may exist an optimal time lag interval in cross-lagged analysis, as suggested by Dormann and Griffin ( 2015 ). When the time lag falls short of this optimal point, the cross-lagged effect size diminishes sharply; inversely, if the time lag exceeds it, the effect size likewise declines. Aligning with prior meta-analysis efforts (Riketta, 2008 ), we categorize the time lag into two groups, namely, 1–6 months and 7–12 months, to explore the possible moderating influence of the time lag. The efficacy of a 6-month time lag design remains uncertain. Nevertheless, a design that maintains a 6-month interval at each end—presenting a symmetrical six-month span—prompts a subgroup analysis within the meta-analysis, increasing the likelihood of discerning potential moderating impacts. To sum up, we seek to answer the following research question:

Research Question 1 : Do the causal relationship between work motivation and job performance vary due to (a) job performance measurement (task performance versus OCB), (b) work motivation measurement (work commitment versus other motivations), and (c) time lag (1–6 months versus 7–12 months)?

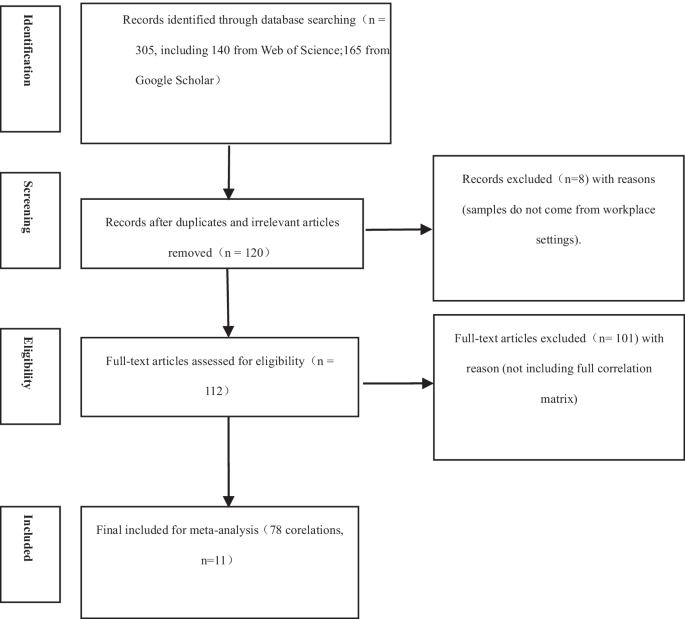

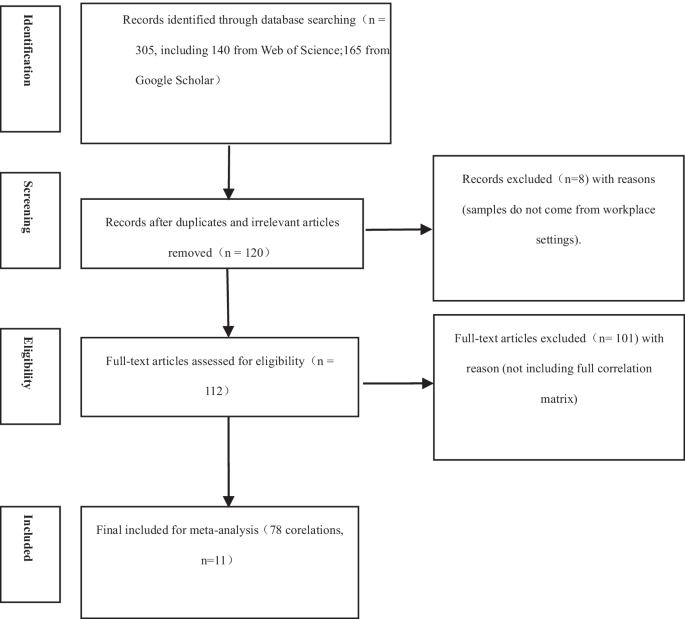

Literature search

To locate the studies that might include the cross-lagged data about work motivation and job performance, following early meta-analyses (Neuber et al., 2021 ; Riketta, 2008 ; Van Iddekinge et al., 2018 ), the authors searched the following keywords: (a) motivation ( motivation or engagement ), (b) performance ( performance , job performance , task performance , or organization citizenship behavior ), and (c) cross-lagged ( longitudinal or cross-lagged) utilizing Web of Science and Google Scholar databases. The authors (W and L) seek to include studies published from 2000 to 2022. The search was conducted in January 2023 and encompassed English-language research materials. We did not restrict the types of research sources, including journal articles, book chapters, and dissertations. Authors W and L performed the search using the Title, Abstract, and Keywords. After removing duplicates, the authors initially obtained 120 potential articles that used longitudinal data.

Inclusion criteria and coding

After reviewing some early published longitudinal meta-analyses (Maricuțoiu et al., 2017 ; Riketta, 2008 ; Talsma et al., 2018 ), the authors made the following inclusion criteria. First, samples should come from organizations because the current study focuses on work motivation and job performance. As such, students’ or athletes’ samples were removed.

Second, studies should provide a full correlation matrix that includes six correlations and measure motivation and performance at two (or more) measurement waves. Six correlations are two synchronous correlations, the two cross-lagged correlations, and the two stabilities correlations (Kenny, 1975 ). In particular, two synchronous correlations are correlations (a) between motivation (T1) and performance (T1) and (b) between motivation (T2) and performance (T2). Two cross-lagged correlations are correlations (a) between motivation (T1) and performance (T2) and (b) between performance (T1) and motivation (T2). Two stabilities correlations are correlations (a) between motivation (T1) and motivation (T2) and (b) between performance (T1) and performance (T2).

After reading all potential studies ( k = 120) and excluding studies that were not able to meet the inclusion criteria, the final database contained 11 studies that included 84 correlations ( n = 4389). Considering the challenges in obtaining samples and findings from early meta-analyses (Riketta, 2008 , with 16 studies; Talsma et al., 2018 , with 11 studies), a sample of 11 studies is likely sufficient for conducting a cross-lagged meta-analysis. Two authors coded the following information: bibliographic references (authors and publication year), sample description (sample size and country), research design (interval between two measurement waves), effect sizes, and the reliabilities (i.e., Cronbach’s α) of all scales. The authors discussed the differences in the coding information until the intercoder agreement was researched 100%. Among the examined studies, 8 utilized a self-reported method for measuring performance, 2 adopted a leader-reported method, and 1 study employed an objective indicator, specifically the results of performance appraisals. The majority of these studies ( k = 10) originated from companies, with only one emanating from an educational organization. The samples in the 11 studies encompass a wide range of industries, including banking, auditing, and social services. The diversity in this study stems from the primary authors’ intentional strategy to collect data from a variety of industries. This approach enables a comprehensive insight into the nature of professional settings and employee motivation across different sectors. Geographically, most samples were drawn from Europe (k = 9), while the remaining were from East Asia (k = 2). A PRISMA flowchart (see Fig. 5 ) presents the process of literature search.

An illustrative demonstration of literature search procedures and inclusion criteria. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

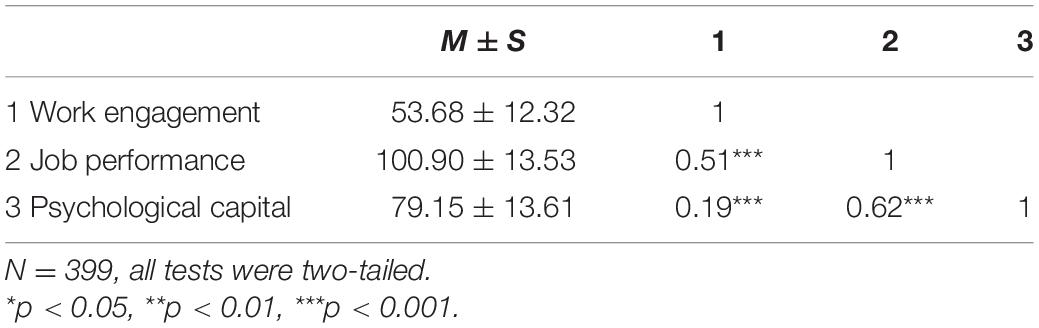

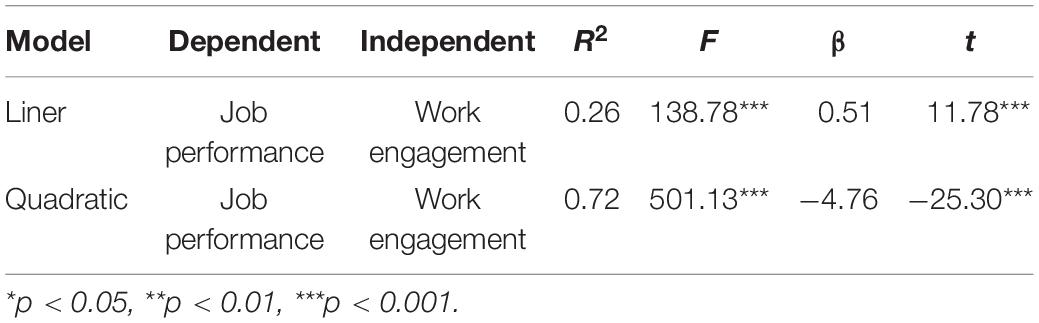

Before analyzing, publication bias is taken into consideration. We used the Trim-and-Fill method and Eggs’ Regression method to detect potential publication bias. This analysis was conducted utilizing metafor package (Viechtbauer, 2010 ) in R. The results were shown in Table 1 .

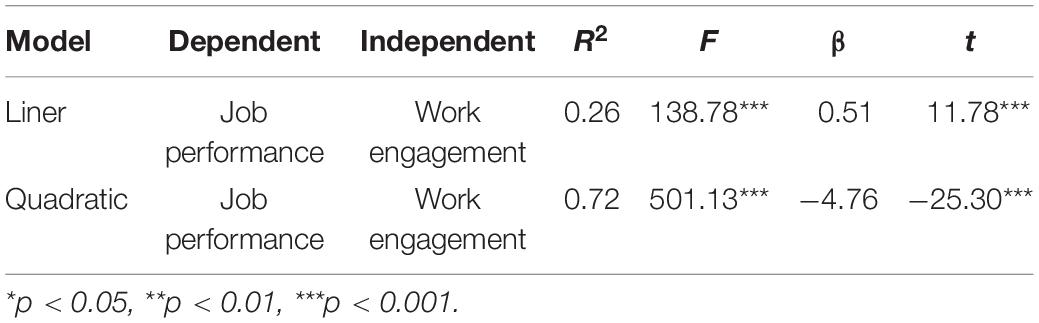

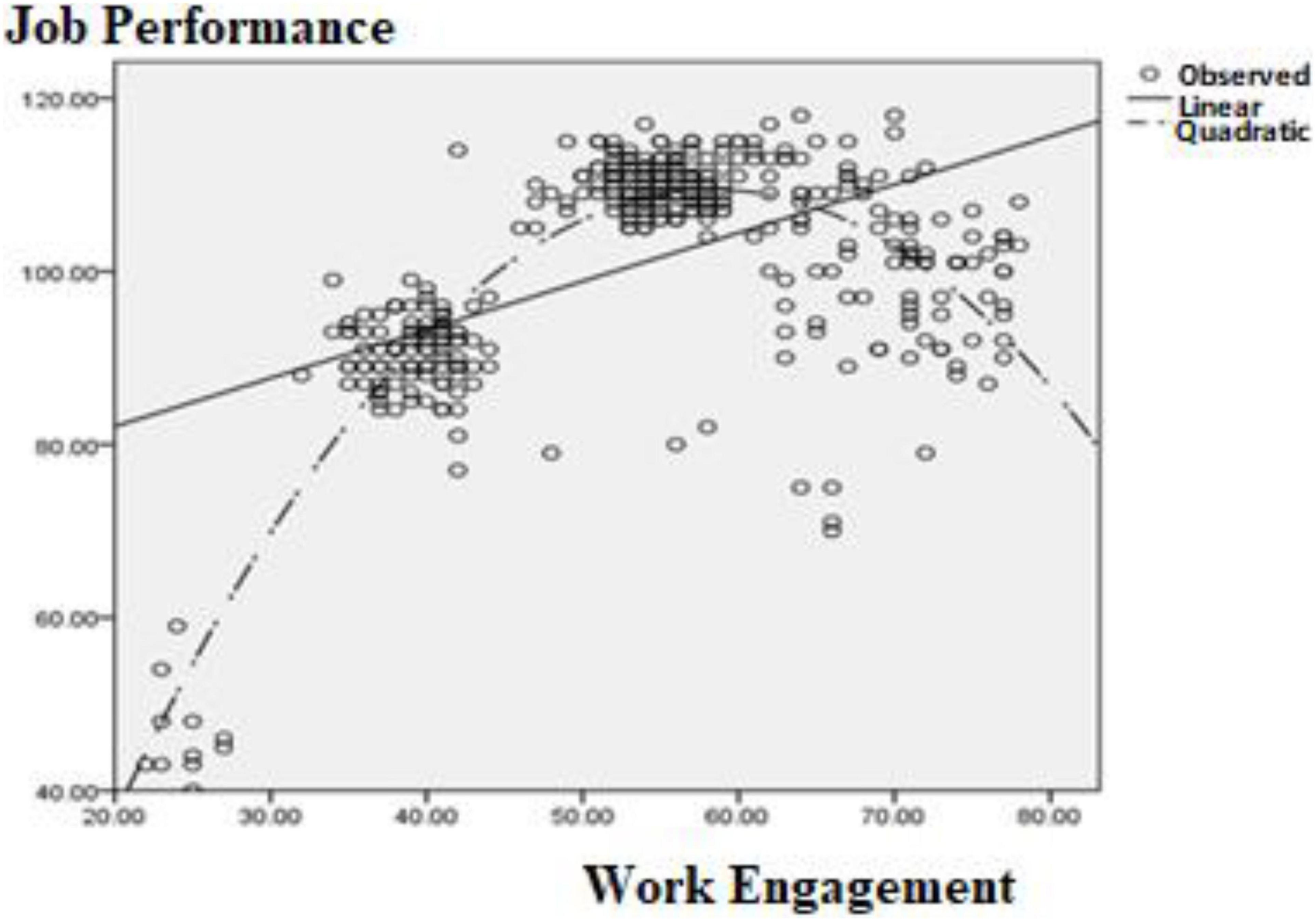

Generally speaking, there are two steps in a meta-analytic structural equation modeling analysis (Bergh et al., 2016 ; Viswesvaran and Ones, 1995 ). The first one is to build a meta-analytic correlation matrix. The second one is to use this matrix to conduct path analysis. In the current study, to build a meta-analytic correlation matrix, we employed the Hunter-Schmidt methods’ meta-analysis technology to aggregate effect sizes (Hunter and Schmidt, 2004 ). In particular, reliabilities (i.e., Cronbach’s α) were used to correct measurement errors. The random effect meta-analysis method was utilized to correct sampling errors. This analysis was accomplished using the psychmeta package (Dahlke and Wiernik, 2019 ) in R. The results of the meta-analytic correlation matrix for path analysis were shown in Table 2 . To answer research question 1, Table 2 also includes correlations that are grouped by performance measurements, motivation measurements, and time lags.

Then, this meta-analytic correlation matrix was used to conduct path analysis, the results were shown in Table 3 . This analysis was accomplished using MPLUS software (Muthén and Muthén, 2017 ). Specifically, to conduct path analysis, the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) was used. Besides, the sum of the sample sizes was employed as the inputted sample size (Riketta, 2008 ).

As Table 1 shows, the results suggest there is not a significant publication bias. First, using the Trim-and-Fill method, only one asymmetric effect size was located (i.e., the correlation between performance T1 and performance T2). After inputting this “missed” correlation, the averaged correlation only decreased by 0.02, suggesting the publication bias is not serious. Second, utilizing the Eggs’ Regression method, all the p-values are bigger than 0.05, confirming the publication bias is not significant. Together, the overall publication bias is not serious.

Table 2 depicts the averaged correlation (r) and true score correlation (ρ) of interest. For instance, the ρ between motivation (T1) and motivation (T2) is 0.80, whereas the ρ between performance (T1) and performance (T2) is 0.54.

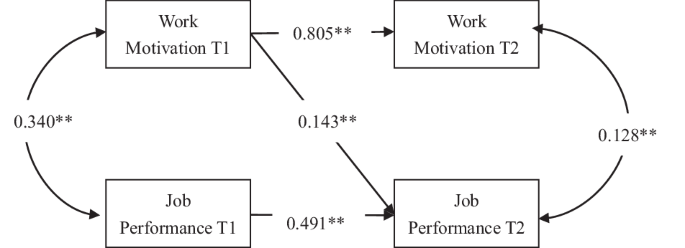

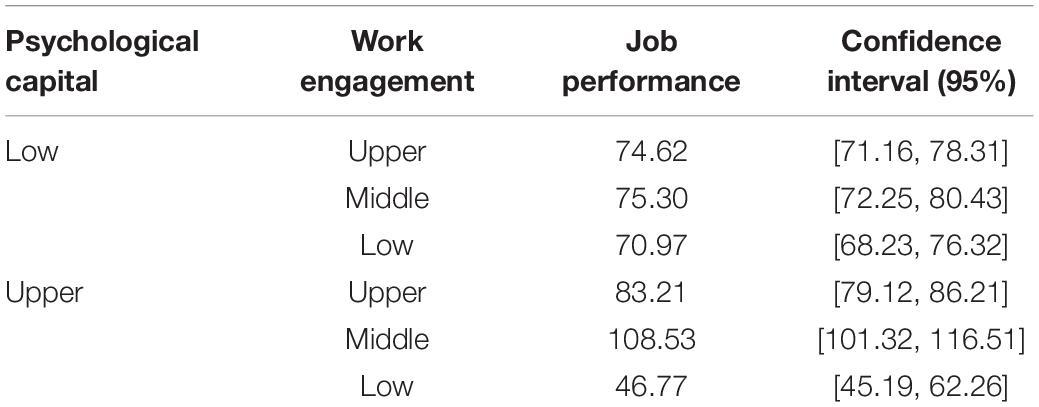

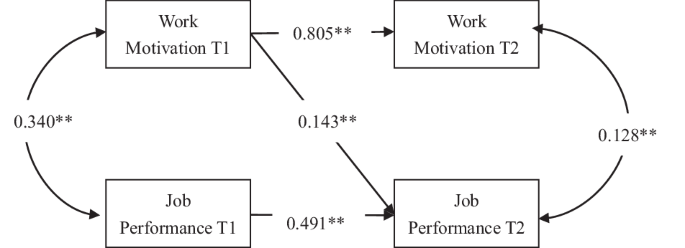

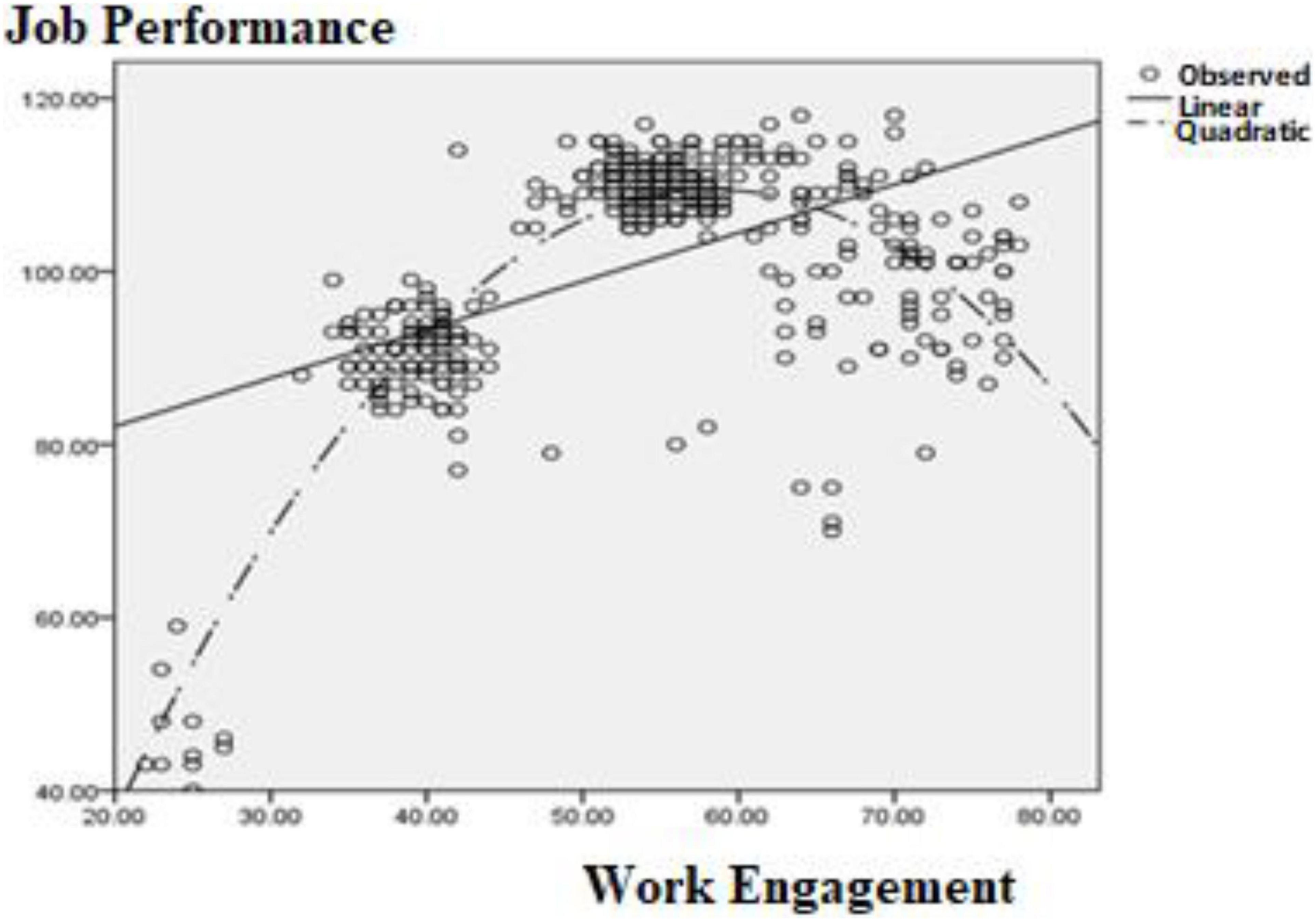

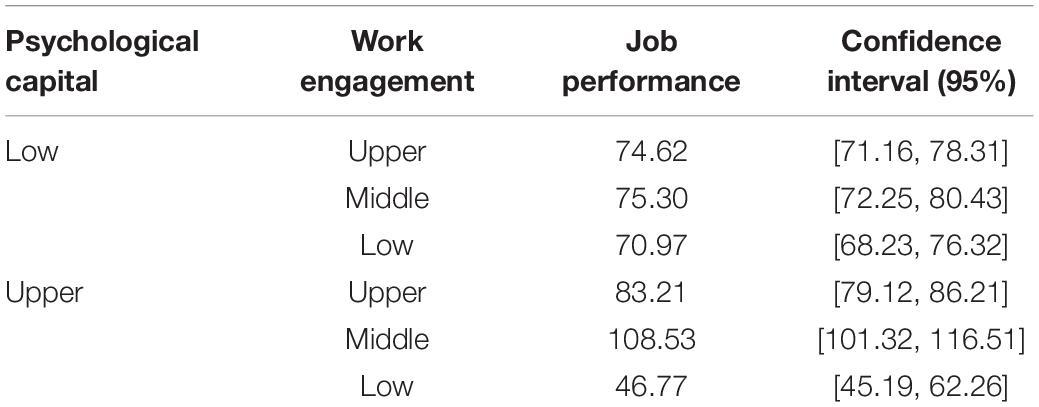

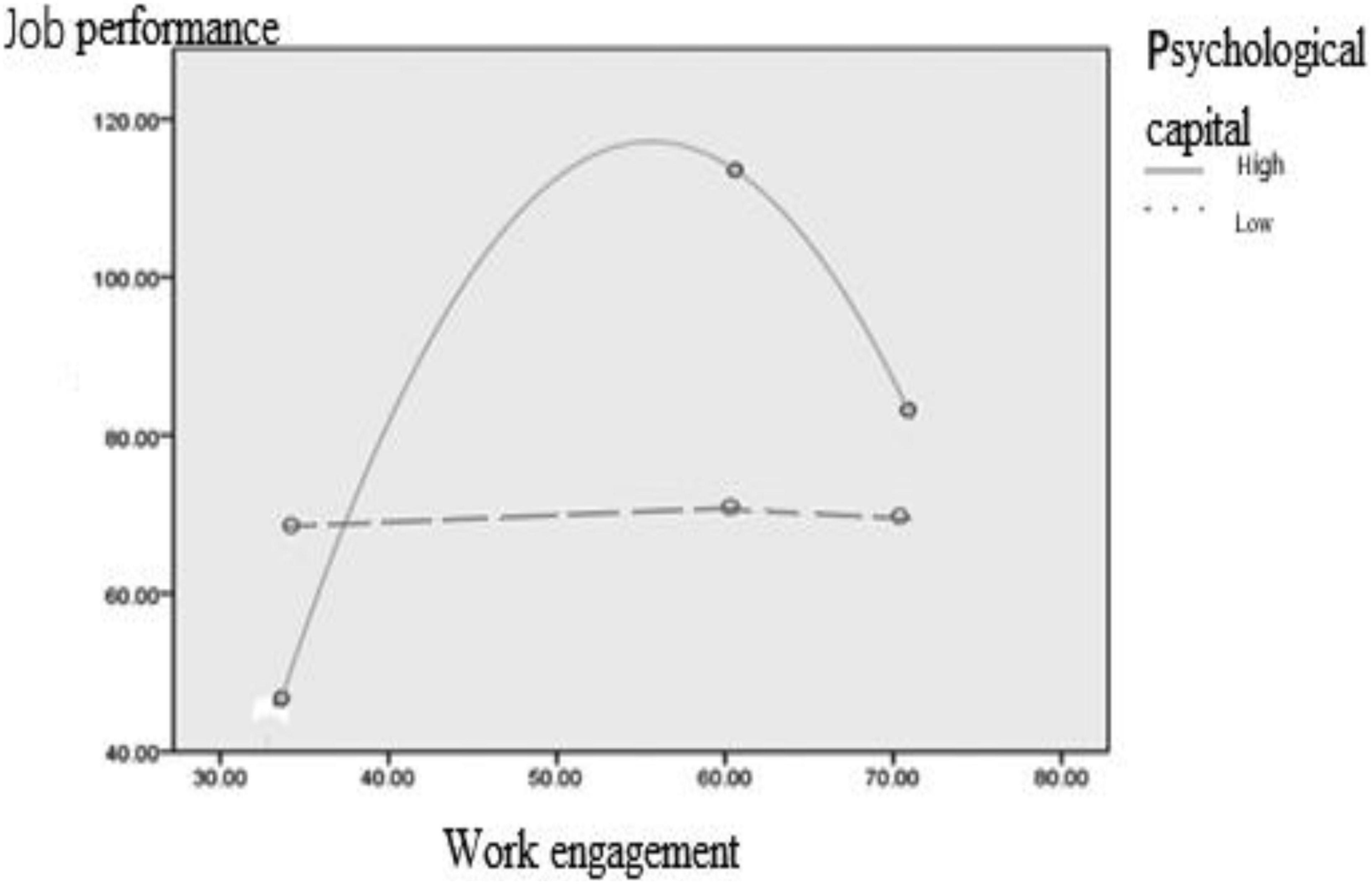

As Table 3 presents, overall, work motivation appears to be a predictor of job performance, whereas job performance appears to be a predictor of work motivation. In particular, the path coefficient (i.e., M1 → P2) from motivation (T1) to performance (P2) is positive and significant ( β = 0.143, p < 0.001). However, the path coefficient (i.e., P1 → M2) from performance (T1) to motivation (P2) is not significant ( β = −0.014, p > 0.050). As such, H1 was supported, whereas H2, H3, and H4 were rejected. We draw Fig. 6 to explain the causal relationship between work motivation and job performance.

An illustration of estimated causal relationship between work motivation and job performance following MASEM analysis. This figure is covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

To answer research question 1, as Table 3 shows, neither the performance measure, motivation measure, nor time lag influence the causal relationship between motivation and performance. In particular, all the path coefficients (i.e., M1 → P2) from motivation (T1) to performance (P2) are positive and significant. However, the path coefficients (i.e., P1 → M2) from performance (T1) to motivation (P2) are negative or insignificant, supporting H1. The moderating effect was determined using z-tests to compare the two effect sizes. For example, when examining the moderating role of the performance measure, there was no significant difference in path coefficients for M1 → P2 (β1 = 0.129, β2 = 0.085; z = 1.4, p = 0.08). Similarly, for path coefficients P1 → M2, no significant difference was observed (β1 = −0.016, β2 = −0.052; z = 1.14, p = 0.13). Additionally, we did not observe any significant moderating effect for either motivation measures or time lag. Together, the causal relationship is motivation causes subsequent performance rather than vice versa. Besides, this relationship is not influenced by the three potential moderators.

In this part, we will first discuss our findings. Then, we will discuss the theoretical and practical implications. Finally, the limitations and future directions will be discussed.

To start, we will discuss the magnitude of correlations. Cohen ( 2013 ) suggested that a correlation at 0.1 is small, at 0.3 is medium, whereas at 0.5 is large. Applying this standard, we find that the magnitudes of correlations of interest are from medium to large. For instance, the ρ between motivation (T1) and motivation (T2) is 0.80 which is large, whereas the ρ between performance (T1) and performance (T2) is 0.54 which is medium. Besides, the correlation ( ρ = 0.34) between motivation (T1) and performance (T1) is bigger than the correlation ( ρ = 0.31) between motivation (T1) and performance (T2). One plausible explanation is that the former is measured at the same time point whereas the latter is measured at different time points. Two constructs measuring at the same time point may suffer from common method bias and their correlation may inflate (Podsakoff et al., 2003 ). Besides, early meta-analyses also found the correlations between motivation and performance are medium. For instance, Cerasoli et al. ( 2014 ) found a correlation between intrinsic motivation and performance is 0.26. Similarly, Borst et al. ( 2019 ) found medium correlations between engagement and in-role performance and ex-role performance (range from 0.31 to 0.46). To sum up, the overall correlations between motivation and performance are medium.

Then, we found that work motivation causes job performance rather than vice versa. This finding rejects the reciprocal and causally unrelated model. This finding is in line with many experiment studies (e.g., Amabile, 1985 ; Hendijani et al., 2016 ; Kovjanic et al., 2013 ) which found that motivation influenced performance. Combining the findings of both longitudinal and experimental studies, evidence suggests that work motivation appears to be a predictor of job performance.

However, what makes us surprised is that job performance cannot predict work motivation based on cross-lagged data. One possible explanation is there might be mediators that fully mediate the relationship between job performance and subsequent work motivation. For instance, in the perspective of SDT (Deci et al., 2017 ; Deci and Ryan, 2000 ), basic psychological needs (i.e., competence, autonomy, and relatedness) are the antecedents of motivation. Employees who accomplished their job performance are likely to fulfill the need for competence and thereby influence motivation. Thus, job performance (T1) may not directly influence work motivation (T2) but through the mediating role of basic psychological needs. In the JD-R theory (Bakker, 2011 ; Bakker and Demerouti, 2017 ), there could also have mediators between performance and motivation. These mediators are job resources (e.g., leader support). Employees who achieve performance may influence job resources (e.g., leader support) and thereby influence their motivation. In the current cross-lagged panel meta-analysis, these potential mediators (e.g., basic psychological needs and leader support) could not be tested. Therefore, we do not find job performance (T1) causes work motivation (T2).

Finally, three moderators (i.e., performance measure, motivation measure, and time lag) do not influence the causal relationship between motivation and performance. First, for performance measures, one explanation is that both task performance and OCB captured the nature of job performance. Second, for motivation measures, one explanation is that different measures of motivation both reflect the definition of motivation (Pinder, 2014 ). For instance, employees could work hard by being driven by both work engagement (Bakker, 2011 ) and intrinsic motivation (Deci et al., 2017 ). In other words, despite different measures of motivation being used, these concepts all capture the characteristics of motivation, indicating a consensus conclusion.

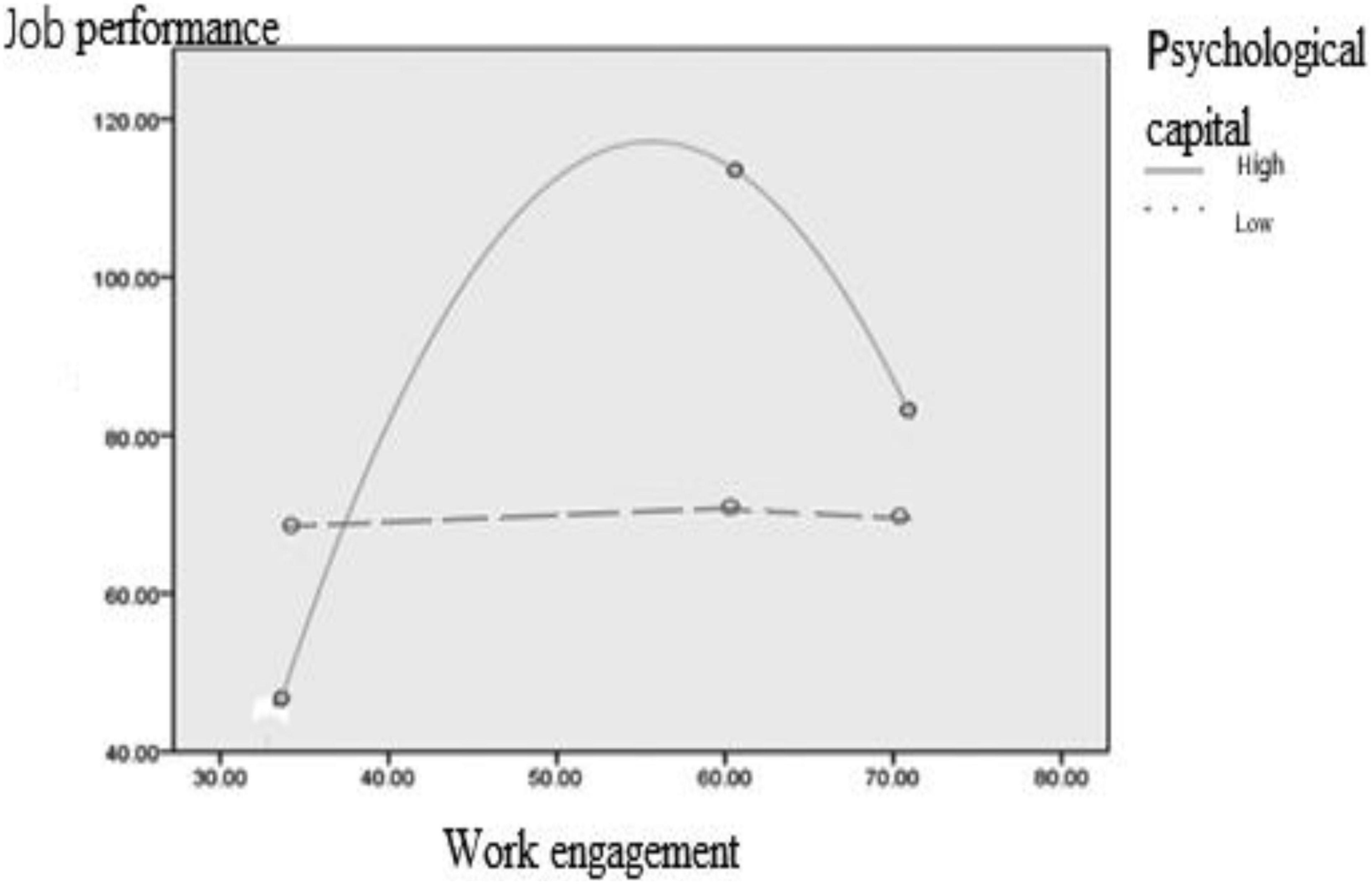

It’s important to acknowledge that various studies have employed distinct measures to gauge motivation, including psychological capital and self-efficacy, among others. Psychological capital can indeed serve as a reflection of motivation. Comprising four subdimensions—self-efficacy, hope, resilience, and optimism—psychological capital embodies the internal forces (motivation) that drive individuals to confront challenges (Newman et al., 2014 ). These components collectively capture the essence of motivation by epitomizing the underlying reasons that initiate and direct behavior. Therefore, they are integral in understanding the multifaceted nature of motivation. Additionally, our moderation analysis contributes further insights, suggesting that despite the nuanced complexities of motivation measures, they didn’t exhibit a substantial moderating impact on the outcomes. This finding underscores the importance of considering these motivational aspects not just as isolated factors but as integral components that interact with other elements in human behavior and response mechanisms.

For time lag, an early meta-analysis study finds a significant moderating role in the length of time lag (Riketta, 2008 ) which is different from the current study. In the current study, we noticed that the length of time lag is between 1 month and 12 months. However, we still lack the knowledge of whether this causal relationship will change over a longer period of time (e.g., more than 12 months). Together, three moderators do not influence the causal relationship between work motivation and job performance, strengthening the confidence in our findings.

Theoretical and practical implications

The current study is the first meta-analysis that uses longitudinal data to test the causal relationship between work motivation and job performance, making some theoretical implications. First, utilizing meta-analysis methodology, we reconciled four competing hypotheses about the causal relationship between work motivation and job performance, contributing to work motivation and job performance literature. Second, the current study contributes to SDT literature. SDT suggests that work motivation will influence human behavior and job performance (Deci et al., 2017 ). The current study provides solid evidence for the argument of SDT by using longitudinal data. Besides, the current study collected data from multiple organizations, making the findings have high external validity. Finally, the current study provided evidence for the JD-R theory, as we found engagement causes job performance rather than vice versa using a cross-lagged research design. Drawing on this finding, some results (e.g., Yu et al., 2020 ; Almawali et al., 2021 ), in JD-R literature using a cross-temporal research design, should be explained with caution.

The current study is also essential to practice. First, as the current study provides solid causal evidence for the motivation-performance linkage, it provides knowledge for human performance management. That is, human performance practices (e.g., compensation management and performance management) that influence employee motivation, will influence employee performance. Second, our knowledge suggests that some motivation-based leadership (e.g., empowering leadership) is useful as motivation predicts job performance in the long run. Finally, since we do not find job performance could predict subsequent work performance, practitioners should try to find some try practices to strengthen feedback mechanisms between them, making employees increase their performance continuously.

Limitations and future directions

There are some limitations in the current study. First, in the current study, both motivation and performance are measured by self-reported scales, which may trigger common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003 ). This effect is stronger when two constructs are measured at the same time point. For instance, the ρ between job performance (T1) and work motivation (T1) may inflate due to common method bias. Future studies could try to measure performance utilizing more objective indicators. Second, due to the cross-lagged research design, it allows for only tentative causal conclusions and cannot rule out some alternative causal explanations (Riketta, 2008 ). Future studies could try to use instrumental variables to rule out alternative causal explanations (Saridakis et al., 2020 ). Third, the present study employed the MASEM method to carry out path analyses. However, the generalizability of this method to other populations may be limited when dealing with heterogeneous correlation matrices (Cheung, 2018 ). Upon the accumulation of more homogeneous evidence, future research could replicate this study. Fourth, during our search process, we did not impose geographical constraints on the origin of primary studies. However, we observed that the majority of the samples predominantly come from Europe ( k = 9). This brings to light the potential influence of culture on the relationship between motivation and performance. In countries characterized by high individualism, values such as personal achievement and autonomy are emphasized (Hofstede et al. 2010 ). In such cultures, motivation is frequently linked to personal goals and achievements, which may intensify the association between personal-focused motivation and performance. Nonetheless, our current dataset limits our ability to definitively assess these cultural effects. Future research should aim to explore the impact of cultural factors on the motivation-performance dynamics. Finally, our study faced certain constraints regarding data availability, particularly concerning specific motivation metrics such as extrinsic motivation, which were not obtainable from the primary studies. Future research could enhance and validate the findings of this study by employing a broader range of motivation measures. This expanded approach will not only reinforce the comprehensiveness and reliability of the results but also provide a more nuanced understanding of motivational dynamics.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis is the first one to detect the accurate causal relationship between work motivation and job performance using longitudinal data. The evidence supports the effects of work motivation on job performance and does not support the reverse effects. The reciprocal model and causally unrelated model are also not supported. The results appear reasonably robust, as the finding that work motivation predicts job performance was consistent across the examined moderators of job performance measure, motivation measure, and time lag length. This study contributes to motivation and performance literature. Besides, our findings are important for human resource management and leadership. Future studies could try to use instrumental variables to get a more accurate causal relationship.

Data availability

All data used to conduct the meta-analytic review are included in the supplemental file.

Almatrooshi B, Singh S.K, Farouk S (2016) Determinants of organizational performance: a proposed framework. Int J Product Perform Manag 65(6):844–859. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-02-2016-0038

Article Google Scholar

Almawali H, Hafit NIA, Hassan N (2021) Motivational factors and job performance: the mediating roles of employee engagement. Int J. Hum. Resour. Stud. 11(3):6782–6782

Amabile TM (1985) Motivation and creativity: effects of motivational orientation on creative writers. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 48(2):393–399

Anesukanjanakul J, Banpot K, Jermsittiparsert K (2019) Factors that influence job performance of agricultural workers. Int J. Innov. Creativ Change 7(2):71–86

Google Scholar

Bakker AB (2011) An evidence-based model of work engagement. Curr. Directions Psychol. Sci. 20(4):265–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411414534

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2007) The job demands‐resources model: state of the art. J. Manag Psychol. 22(3):309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Bakker AB, Oerlemans W (2011) Subjective well-being in organizations. Oxf. Handb. Posit. Organ Scholarsh. 49:178–189

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2017) Job demands-resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 22(3):273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Sanz-Vergel AI (2014) Burnout and work engagement: the JD–R approach. Annu Rev. Organ Psychol. Organ Behav. 1(1):389–411. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235

Becker TE, Kernan MC (2003) Matching commitment to supervisors and organizations to in-role and extra-role performance. Hum. Perform. 16(4):327–348

Bergh DD, Aguinis H, Heavey C, Ketchen DJ, Boyd BK, Su P, Lau CL, Joo H (2016) Using meta‐analytic structural equation modeling to advance strategic management research: guidelines and an empirical illustration via the strategic leadership‐performance relationship. Strategic Manag J. 37(3):477–497

Bergner, RM (2020) What is personality? Two myths and a definition. New Ideas Psychol 57 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2019.100759

Borman WC, Motowidlo SJ (1997) Task performance and contextual performance: The meaning for personnel selection research. Hum. Perform. 10(2):99–109

Borst RT, Kruyen PM, Lako CJ, de Vries MS (2019) The attitudinal, behavioral, and performance outcomes of work engagement: a comparative meta-analysis across the public, semipublic, and private sector. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 40(4):613–640. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371x19840399

Bycio P, Hackett RD, Alvares KM (1990) Job performance and turnover: a review and meta‐analysis. Appl Psychol. 39(1):47–76

Campbell JP, Wiernik BM (2015) The modeling and assessment of work performance. Annu Rev. Organ Psychol. Organ Behav. 2(1):47–74

Cerasoli CP, Nicklin JM, Ford MT (2014) Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives jointly predict performance: a 40-year meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 140(4):980–1008. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035661

Cheung MW-L (2018) Computing multivariate effect sizes and their sampling covariance matrices with structural equation modeling: theory, examples, and computer simulations. Fron Psychol 9:1387. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01387

Choi Y, Ha S-B, Choi D (2022) Leader Humor and followers’ change-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: the role of leader machiavellianism. Behav Sci 12(2):22 https://www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/12/2/22

Christenson, SL, Reschly, AL, Wylie, C (eds) (2012) Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. Boston, MA: Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7

Cohen J (2013) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Corbeanu A, Iliescu D (2023) The link between work engagement and job performance. J Personnel Psychol 22(3). https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000316

Dahlke JA, Wiernik BM (2019) psychmeta: an R package for psychometric meta-analysis. Appl Psychol. Meas. 43(5):415–416

Dalal RS (2005) A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. J. Appl Psychol. 90(6):1241–1255. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1241

Deci EL, Ryan RM (2000) The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11(4):227–268

Deci EL, Koestner R, Ryan RM (1999) A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychol. Bull. 125(6):627–668

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Deci EL, Olafsen AH, Ryan RM (2017) Self-determination theory in work organizations: the state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ Psychol. Organ Behav. 4(1):19–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032516-113108

Dormann C, Griffin MA (2015) Optimal time lags in panel studies. Psychol. Methods 20(4):489–505. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000041

Fishbach A, Woolley K (2022) The structure of intrinsic motivation. Annu Rev. Organ Psychol. Organ Behav. 9:339–363

Ford MT, Cerasoli CP, Higgins JA, Decesare AL (2011) Relationships between psychological, physical, and behavioural health and work performance: a review and meta-analysis. Work Stress 25(3):185–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2011.609035

Gagné M, Deci EL (2005) Self‐determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ Behav. 26(4):331–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322

Giancaspro ML, De Simone S, Manuti A (2022) Employees’ perception of HRM practices and organizational citizenship behaviour: the mediating role of the Work–Family Interface. Behav. Sci. 12(9):301

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Hartinah S, Suharso P, Umam R, Syazali M, Lestari B, Roslina R, Jermsittiparsert K (2020) Retracted: Teacher’s performance management: the role of principal’s leadership, work environment and motivation in Tegal City, Indonesia. Manag Sci. Lett. 10(1):235–246

Hendijani R, Bischak DP, Arvai J, Dugar S (2016) Intrinsic motivation, external reward, and their effect on overall motivation and performance. Hum. Perform. 29(4):251–274

Hermanto YB, Srimulyani VA (2022) The effects of organizational justice on employee performance using dimension of organizational citizenship behavior as mediation. Sustainability 14(20):13322

Hoffman BJ, Blair CA, Meriac JP, Woehr DJ (2007) Expanding the criterion domain? A quantitative review of the OCB literature. J. Appl Psychol. 92(2):555–566. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.555

Hofstede G, Garibaldi De Hilal AV, Malvezzi S, Tanure B, Vinken H (2010) Comparing Regional Cultures Within a Country: Lessons From Brazil. J Cross-Cult Psychol 41(3):336–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022109359696

Hunter, JE, Schmidt, FL (2004) Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483398105

Iaffaldano MT, Muchinsky PM (1985) Job satisfaction and job performance: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 97(2):251–273

Jaramillo F, Mulki JP, Marshall GW (2005) A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational commitment and salesperson job performance: 25 years of research. J. Bus. Res 58(6):705–714

Judge TA, Ilies R (2002) Relationship of personality to performance motivation: a meta-analytic review. J. Appl Psychol. 87(4):797–807. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.797

Judge TA, Kammeyer-Mueller JD (2012) Job attitudes. Annu Rev. Psychol. 63:341–367. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100511

Judge TA, Thoresen CJ, Bono JE, Patton GK (2001) The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: a qualitative and quantitative review. Psycho Bull. 127(3):376–407

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kanfer R (1990) Motivation theory and industrial and organizational psychology. Handb. Ind. Organ Psychol. 1(2):75–130

Kanfer R, Frese M, Johnson RE (2017) Motivation related to work: a century of progress. J. Appl Psychol. 102(3):338–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000133

Kenny DA (1975) Cross-lagged panel correlation: a test for spuriousness. Psychol. Bull. 82(6):887–903

Konze A-K, Rivkin W, Schmidt K-H (2017) Is Job Control a Double-Edged Sword? A cross-lagged panel study on the interplay of quantitative workload, emotional dissonance, and job control on emotional exhaustion. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121608

Koopmans L, Bernaards CM, Hildebrandt VH, Schaufeli WB, de Vet Henrica CW, van der Beek AJ (2011) Conceptual frameworks of individual work performance: a systematic review. J. Occup. Environ. Med 53(8):856–866. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e318226a763

Kovjanic S, Schuh SC, Jonas K (2013) Transformational leadership and performance: an experimental investigation of the mediating effects of basic needs satisfaction and work engagement. J. Occup. Organ Psychol. 86(4):543–555

LePine JA, Erez A, Johnson DE (2002) The nature and dimensionality of organizational citizenship behavior: a critical review and meta-analysis. J. Appl Psychol. 87(1):52–65. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.87.1.52

Locke EA, Latham GP (2006) New directions in goal-setting theory. Curr. Directions Psychol. Sci. 15(5):265–268

MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff PM, Fetter R (1991) Organizational citizenship behavior and objective productivity as determinants of managerial evaluations of salespersons' performance. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50(1):123–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90037-T

Maricuțoiu LP, Sulea C, Iancu A (2017) Work engagement or burnout: which comes first? A meta-analysis of longitudinal evidence. Burnout Res 5:35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2017.05.001

Martin TN, Price J, Mueller CW (1981) Job performance and turnover. J. Appl Psychol. 66(1):116–119

Mathieu JE, Zajac DM (1990) A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychol. Bull. 108(2):171–194

Motowidlo SJ (2003) Job performance. Handb. Psychol. Ind. Organ Psychol. 12(4):39–53

Muawanah M, Muhamad Y, Syamsul H, Iskandar T, Muhamad S, Rofiqul U, Kittisak J (2020) Career management policy, career development, and career information as antecedents of employee satisfaction and job performance. Int J. Innov. Creativity Change 11(6):458–482

Muthén B, Muthén L (2017) Mplus. In Handbook of item response theory, Chapman and Hall/CRC, (pp. 507-518)

Nawrocka S, De Witte H, Brondino M, Pasini M (2021) On the reciprocal relationship between quantitative and qualitative job insecurity and outcomes. testing a cross-lagged longitudinal mediation model. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126392

Neuber L, Englitz C, Schulte N, Forthmann B, Holling H (2021) How work engagement relates to performance and absenteeism: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Work Organ Psychol. 31(2):292–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2021.1953989

Newman A, Ucbasaran D, Zhu F, Hirst G (2014) Psychological capital: a review and synthesis. J. Organ Behav. 35(S1):S120–S138. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1916

Organ DW (2018) Organizational citizenship behavior: recent trends and developments. Annu Rev. Organ Psychol. Organ Behav. 80:295–306

Organ, DW (1988) Organizational citizenship behaviour: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington, MA: Lexington

Pinder CC (2014) Work motivation in organizational behavior. New York: Psychology Press

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl Psychol. 88(5):879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Presbitero A (2017) How do changes in human resource management practices influence employee engagement? A longitudinal study in a hotel chain in the Philippines. J. Hum. Resour. Hospitality Tour. 16(1):56–70

Raja U, Johns G (2010) The joint effects of personality and job scope on in-role performance, citizenship behaviors, and creativity. Hum. Relat. 63(7):981–1005

Riketta M (2008) The causal relation between job attitudes and performance: a meta-analysis of panel studies. J. Appl Psychol. 93(2):472–481. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.2.472

Saridakis G, Lai Y, Muñoz Torres RI, Gourlay S (2020) Exploring the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment: an instrumental variable approach. Int J. Hum. Resour. Manag 31(13):1739–1769

Shimazu A, Schaufeli WB, Kubota K, Watanabe K, Kawakami N (2018) Is too much work engagement detrimental? Linear or curvilinear effects on mental health and job performance. PLoS One 13(12):e0208684. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208684

Article CAS PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Sidorenkov AV, Borokhovski EF (2021) Relationships between Employees’ identifications and citizenship behavior in work groups: the role of the regularity and intensity of interactions. Behav. Sci. 11(7):92. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-328X/11/7/92

Talsma K, Schüz B, Schwarzer R, Norris K (2018) I believe, therefore I achieve (and vice versa): a meta-analytic cross-lagged panel analysis of self-efficacy and academic performance. Learn Individ Differ. 61:136–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2017.11.015

Van den Broeck A, Howard JL, Van Vaerenbergh Y, Leroy H, Gagné M (2021) Beyond intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: a meta-analysis on self-determination theory’s multidimensional conceptualization of work motivation. Organ Psychol. Rev. 11(3):240–273

Van Iddekinge CH, Aguinis H, Mackey JD, DeOrtentiis PS (2018) A meta-analysis of the interactive, additive, and relative effects of cognitive ability and motivation on performance. J. Manag 44(1):249–279

Viechtbauer W (2010) Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36(3):1–48

Viswesvaran C, Ones DS (1995) Theory testing: combining psychometric meta‐analysis and structural equations modeling. Pers. Psychol. 48(4):865–885

Viswesvaran C, Ones DS (2000) Perspectives on models of job performance. Int J. Sel. Assess. 8(4):216–226

Williams LJ, Anderson SE (1991) Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. J. Manag 17(3):601–617

Young HR, Glerum DR, Joseph DL, McCord MA (2021) A meta-analysis of transactional leadership and follower performance: double-edged effects of LMX and empowerment. J. Manag 47(5):1255–1280

Yu J, Ariza-Montes A, Giorgi G, Lee A, Han H (2020) Sustainable relationship development between hotel company and its employees: linking job embeddedness, job satisfaction, self-efficacy, job performance, work engagement, and turnover. Sustainability 12(17). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12177168

Download references

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Nan Wang, Yuxiang Luan.

Authors and Affiliations

School of Business, North Minzu University, Yinchuan, Ningxia, China

School of Labor and Human Resources, Renmin University of China, Beijing, China

Yuxiang Luan

School of Management, North Minzu University, Yinchuan, Ningxia, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

NW and YL: idea and design; NW and YL: introduction, hypotheses, and coding; YL and RM: method and results; NW, YL and RM: discussion and conclusion. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yuxiang Luan .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study does not contain any interaction with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

No human subjects are involved in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Raw data and analysis codes, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wang, N., Luan, Y. & Ma, R. Detecting causal relationships between work motivation and job performance: a meta-analytic review of cross-lagged studies. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11 , 595 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03038-w

Download citation

Received : 19 May 2023

Accepted : 16 April 2024

Published : 09 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03038-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Information

Initiatives

You are accessing a machine-readable page. In order to be human-readable, please install an RSS reader.

All articles published by MDPI are made immediately available worldwide under an open access license. No special permission is required to reuse all or part of the article published by MDPI, including figures and tables. For articles published under an open access Creative Common CC BY license, any part of the article may be reused without permission provided that the original article is clearly cited. For more information, please refer to https://www.mdpi.com/openaccess .

Feature papers represent the most advanced research with significant potential for high impact in the field. A Feature Paper should be a substantial original Article that involves several techniques or approaches, provides an outlook for future research directions and describes possible research applications.

Feature papers are submitted upon individual invitation or recommendation by the scientific editors and must receive positive feedback from the reviewers.

Editor’s Choice articles are based on recommendations by the scientific editors of MDPI journals from around the world. Editors select a small number of articles recently published in the journal that they believe will be particularly interesting to readers, or important in the respective research area. The aim is to provide a snapshot of some of the most exciting work published in the various research areas of the journal.

Original Submission Date Received: .

- Active Journals

- Find a Journal

- Proceedings Series

- For Authors

- For Reviewers

- For Editors

- For Librarians

- For Publishers

- For Societies

- For Conference Organizers

- Open Access Policy

- Institutional Open Access Program

- Special Issues Guidelines

- Editorial Process

- Research and Publication Ethics

- Article Processing Charges

- Testimonials

- Preprints.org

- SciProfiles

- Encyclopedia

Article Menu

- Subscribe SciFeed

- Recommended Articles

- Google Scholar

- on Google Scholar

- Table of Contents

Find support for a specific problem in the support section of our website.

Please let us know what you think of our products and services.

Visit our dedicated information section to learn more about MDPI.

JSmol Viewer

The relationships between job performance, job burnout, and psychological counselling: a perspective on sustainable development goals (sdgs).

1. Introduction

1.1. sdgs and job burnout in higher education, 1.2. job performance and job burnout in higher education, 1.3. research aim, questions, and hypothesis development, 2. materials and methods, 2.1. research design and participants, 2.2. population and sampling techniques, 2.3. measures, 2.3.1. control variables, 2.3.2. job performance (kpi), 2.3.3. burnout level, 2.3.4. psychological counselling, 2.4. ethical considerations, 2.5. data analysis, 3.1. job performance predicts job burnout in higher education, 3.2. job burnout: the moderating role of psychological counselling, 4. discussion, 4.1. job-performance vs. job burnout, 4.2. psychological counselling to alleviate treating burnout: post-cautionary measurement vs. pre-cautionary measurement, 4.3. reducing job burnout for sdgs in higher education, 5. limitations and future studies, 6. conclusions and implications, author contributions, institutional review board statement, informed consent statement, data availability statement, acknowledgments, conflicts of interest.

- Alam, G.M. Has Secondary Science Education Become an Elite Product in Emerging Nations?—A Perspective of Sustainable Education in the Era of MDGs and SDGs. Sustainability 2023 , 15 , 1596. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. Initial progress in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A review of evidence from countries. Sustain. Sci. 2018 , 13 , 1453–1467. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development ; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Leal Filho, W.; Wu, Y.C.J.; Brandli, L.L.; Avila, L.V.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Caeiro, S.; Madruga, L.R.D.R.G. Identifying and overcoming obstacles to the implementation of sustainable development at universities. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2017 , 14 , 93–108. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Blasco, N.; Brusca, I.; Labrador, M. Drivers for Universities’ Contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals: An Analysis of Spanish Public Universities. Sustainability 2021 , 13 , 89. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Boni, A.; Lopez-Fogues, A.; Walker, M. Higher Education and The Post-2015 Agenda: A Contribution from the Human Development Approach. J. Glob. Ethics 2016 , 12 , 17–28. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Sonetti, G.; Sarrica, M.; Norton, L.S. Conceptualization of Sustainability among Students, Administrative and Teaching Staff of A University Community: An Exploratory Study in Italy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021 , 316 , 128292. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mohiuddin, M.; Hosseini, E.; Faradonbeh, S.B.; Sabokro, M. Achieving Human Resource Management Sustainability in Universities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022 , 19 , 928. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lei, M.; Alam, G.M.; Hassan, A.B. Job Burnout amongst University Administrative Staff Members in China—A Perspective on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2023 , 15 , 8873. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lizano, E.L. Examining the Impact of Job Burnout on the Health and Well-Being of Human Service Workers: A Systematic Review and Synthesis. Human Service Organizations: Management. Leadersh. Gov. 2015 , 39 , 167–181. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hirsig, N.; Rogovsky, N.; Elkin, M. Enterprise Sustainability and HRM in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. In Sustainability and Human Resource Management. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance ; Ehnert, I., Harry, W., Zink, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lambert, E.G.; Hogan, N.L.; Altheimer, I. An Exploratory Examination of the Consequences of Burnout in Terms of Life Satisfaction, Turnover Intent, and Absenteeism Among Private Correctional Staff. Prison. J. 2010 , 90 , 94–114. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Tomislav, K. The Concept of Sustainable Development: From its Beginning to the Contemporary Issues. Zagreb Int. Rev. Econ. Bus. 2018 , 21 , 67–94. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job Demands, Job Resources, and Their Relationship with Burnout and Engagement: A Multi-Sample Study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004 , 25 , 293–315. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Castaño, G. The Impact of Teaching-Research Conflict on Job Burnout among University Teachers: An Integrated Model. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2020 , 31 , 76–90. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Greere, A. Training for Quality Assurance in Higher Education: Practical Insights for Effective Design and Successful Delivery. Qual. High. Educ. 2023 , 29 , 165–191. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Govindaras, B.; Wern, T.S.; Kaur, S.; Haslin, I.A.; Ramasamy, R.K. Sustainable Environment to Prevent Burnout and Attrition in Project Management. Sustainability 2023 , 15 , 2364. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Usán Supervía, P.; Salavera Bordás, C. Burnout Syndrome, Engagement and Goal Orientation in Teachers from Different Educational Stages. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 6882. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Mijakoski, D.; Cheptea, D.; Marca, S.C.; Shoman, Y.; Caglayan, C.; Bugge, M.D.; Gnesi, M.; Godderis, L.; Kiran, S.; McElvenny, D.M.; et al. Determinants of Burnout among Teachers: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022 , 19 , 5776. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Boamah, S.A.; Hamadi, H.Y.; Havaei, F.; Smith, H.; Webb, F. Striking a Balance between Work and Play: The Effects of Work–Life Interference and Burnout on Faculty Turnover Intentions and Career Satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022 , 19 , 809. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Meng, H.; Luo, Y.; Huang, L.; Wen, J.; Ma, J.; Xi, J. On the Relationships of Resilience with Organizational Commitment and Burnout: A Social Exchange Perspective. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017 , 30 , 2231–2250. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- López-Núñez, M.I.; Rubio-Valdehita, S.; Diaz-Ramiro, E.M.; Aparicio-García, M.E. Psychological Capital, Workload, and Burnout: What’s New? The Impact of Personal Accomplishment to Promote Sustainable Working Conditions. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 8124. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Leiter, M.P.; Maslach, C. Motivation, Competence, and Job Burnout. In Handbook of Competence and Motivation: Theory and Application , 2nd ed.; Elliot, A.J., Dweck, C.S., Yeager, D.S., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York City, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 370–384. [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, C.; Zhou, Y.; Li, T.; Ge, W.; An, N. Burnout and Its Association with Competence among Dental Interns in China. Front. Psychol. 2022 , 13 , 832606. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Fazey, D.M.A.; Fazey, J.A. The Potential for Autonomy in Learning: Perceptions of Competence, Motivation and Locus of Control in First-Year Undergraduate Students. Stud. High. Educ. 2001 , 26 , 345–361. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Blaskova, M.; Blasko, R.; Figurska, I.; Sokol, A. Motivation and Development of The University Teachers’ Motivational Competence. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015 , 182 , 116–126. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- UNESCO. Teachers in Tertiary Education Programmes, Both Sexes (Number) in World ; UNESCO: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [ Google Scholar ]

- Watts, J.; Robertson, N. Burnout in University Teaching Staff: A Systematic Literature Review. Educ. Res. 2011 , 53 , 33–50. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. 2022. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2022/indexch.htm (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- Alam, G.M.; Giacosa, E.; Mazzoleni, A. Does MBA’s Paradigm Transformation Follow Business Education’s Philosophy—A Comparison of Academic and Job-Performance and SES among Five Types of MBAian. J. Bus. Res. 2022 , 139 , 881–892. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Paudel, K.P. Level of Academic Performance Among Faculty Members in the Context of Nepali Higher Educational Institution. J. Comp. Int. High. Educ. 2021 , 13 , 98–111. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Davidescu, A.A.; Apostu, S.A.; Paul, A.; Casuneanu, I. Work Flexibility, Job Satisfaction, and Job Performance among Romanian Employees—Implications for Sustainable Human Resource Management. Sustainability 2020 , 12 , 6086. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Musah, M.B.; Tahir, L.M.; Ali, H.M.; Al-Hudawi, S.V.H.; Issah, M.; Farah, A.M.; Abdallah, A.K.; Kamil, N.M. Testing the Validity of Academic Staff Performance Predictors and Their Effects on Workforce Performance. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. (IJERE) 2023 , 12 , 941–955. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Purohit, B.; Martineau, T. Is the Annual Confidential Report System Effective? A Study of the Government Appraisal System in Gujarat, India. Hum. Resour. Health 2016 , 14 , 33–44. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Koopmans, L.; Bernaards, C.M.; Hildebrandt, V.H.; de Vet, H.C.W.; van der Beek, A.J. Construct Validity of the Individual Work Performance Questionnaire. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2014 , 56 , 331–337. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Jahangirian, M.; Taylor, S.J.E.; Young, T.; Robinson, S. Key Performance Indicators for Successful Simulation Projects. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2017 , 68 , 747–765. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Karkoulian, S.; Assaker, G.; Hallak, R. An Empirical Study of 360-Degree Feedback, Organizational Justice, and Firm Sustainability. J. Bus. Res. 2016 , 69 , 1862–1867. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job Burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001 , 52 , 397–422. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Teymoori, E.; Zareiyan, A.; Babajani-Vafsi, S.; Laripour, R. Viewpoint of Operating Room Nurses about Factors Associated with the Occupational Burnout: A Qualitative Study. Front. Psychol. 2022 , 1 , 947189. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Martínez-López, J.Á.; Lázaro-Pérez, C.; Gómez-Galán, J. Burnout among Direct-Care Workers in Nursing Homes during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain: A Preventive and Educational Focus for Sustainable Workplaces. Sustainability 2021 , 13 , 2782. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Oosterholt, B.G.; Maes, J.H.R.; Van der Linden, D.; Verbraak, M.J.P.M.; Kompier, M.A.J. Cognitive Performance in Both Clinical and Non-Clinical Burnout. Stress 2014 , 17 , 400–409. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Lei, M.; Alam, G.M.; Bashir, K.; Pingping, G. Whether Academics’ Job Performance Makes A Difference to Burnout and The Effect of Psychological Counselling—Comparison of Four Types of Performers. PLoS ONE 2024 , 19 , e0305493. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Taris, T.W. Is There A Relationship between Burnout and Objective Performance? A Critical Review of 16 Studies. Work. Stress 2006 , 20 , 316–334. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Luceño-Moreno, L.; Talavera-Velasco, B.; García-Albuerne, Y.; Martín-García, J. Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Levels of Resilience and Burnout in Spanish Health Personnel during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 , 17 , 5514. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- WHO. Mental Health at Work. 28 September 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work (accessed on 1 January 2023).

- National Institutes of Health. Theory at A Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice ; Bethesda: Rockville, MD, USA, 2005. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lei, M.; Alam, G.M.; Bashir, K.; Pingping, G. Does the Job Performance of Academics’ Influence Burnout and Psychological Counselling? A Comparative Analysis amongst High-, Average-, Low-, and Non-performers. BMC Public Health 2024 , 24 , 1708. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Allison, P.D. Fixed Effects Regression Models ; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hsiao, C. Analysis of Panel Data ; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design in Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches , 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. The Method of Dividing the Eastern, Central, Western, and Northeastern Regions ; National Bureau of Statistics of China: Beijing, China, 2011.

- Ministry of Education of China. Several Opinions on Deepening the Promotion of the Construction of World-Class Universities and First-Class Disciplines ; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Cochran, W.G. Sampling Techniques , 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang, L.; Chen, Y. Success or Growth? Distinctive Roles of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Career Goals in High-Performance Work Systems, Job Crafting, and Job Performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2022 , 135 , 103714. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ministry of Education of China. The Guiding Opinions on Deepening the Reform of the Assessment and Evaluation System for Universities Teachers ; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Organization Department of the CPC Central Committee. Regulations on the Assessment of Staff in Public Institutions ; Organization Department of the CPC Central Committee: Beijing, China, 2023. [ Google Scholar ]

- National Health Commission. The Guiding Opinions on Strengthening Psychological Health Services ; National Health Commission: Beijing, China, 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nizami, N.; Prasad, N. Decent Work ; Springer: Singapore, 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pijpker, R.; Vaandrager, L.; Veen, E.J.; Koelen, M.A. Combined Interventions to Reduce Burnout Complaints and Promote Return to Work: A Systematic Review of Effectiveness and Mediators of Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020 , 17 , 55. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ] [ PubMed ]

- Kennedy, F. Beyond “Prevention is Better than Cure”: Understanding Prevention and Early Intervention as An Approach to Public Policy. Policy Des. Pract. 2020 , 3 , 351–369. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Anwar, N.; Nik Mahmood, N.H.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Ramayah, T.; Noor Faezah, J.; Khalid, W. Green Human Resource Management for Organisational Citizenship Behaviour Towards the Environment and Environmental Performance on A University Campus. J. Clean. Prod. 2020 , 256 , 120401. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Žydžiūnaitė, V.; Arce, A. Being An Innovative and Creative Teacher: Passion-Driven Professional Duty. Creat. Stud. 2021 , 14 , 125–144. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Ferraro, T.; dos Santos, N.R.; Moreira, J.M. Decent work, Work Motivation, Work Engagement and Burnout in Physicians. Int. J. Appl. Posit. Psychol. 2020 , 5 , 13–35. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

- Barthauer, L.; Kaucher, P.; Spurk, D.; Kauffeld, S. Burnout and Career (un) Sustainability: Looking into the Blackbox of Burnout Triggered Career Turnover Intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020 , 117 , 103334. [ Google Scholar ] [ CrossRef ]

Click here to enlarge figure

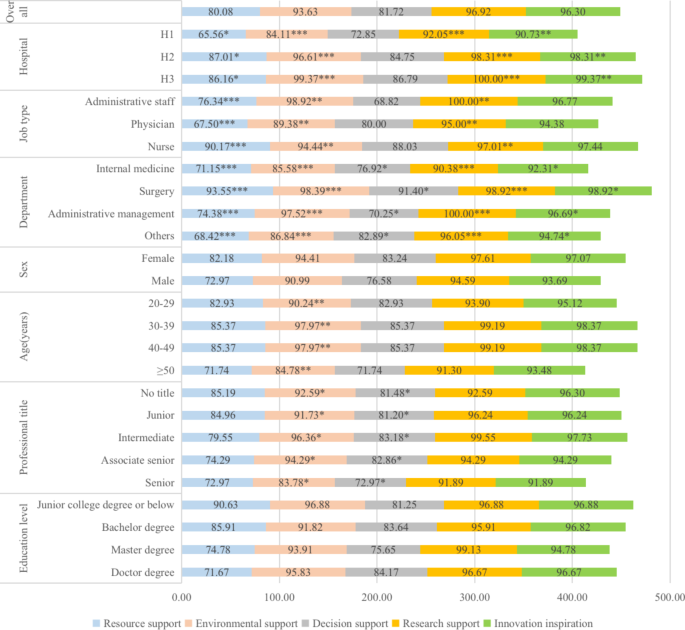

| District | University

Type | Total

A. | Sample

A. | High

P.O. | Average

P.O. | Low

P.O. | Non-P.O. | Sample A.O. |

|---|

| Eastern | Double World-Class university | 2156 | 164 | 83 | 171 | 81 | 157 | 492 |

| Regular university | 1849 | 141 | 70 | 146 | 72 | 135 | 423 |

| Vocational college | 643 | 49 | 27 | 45 | 32 | 43 | 147 |

| Central | Double World-Class university | 3512 | 215 | 101 | 198 | 105 | 241 | 645 |

| Regular university | 1712 | 105 | 66 | 102 | 48 | 99 | 315 |

| Vocational college | 658 | 40 | 19 | 47 | 21 | 33 | 120 |

| Western | Double World-Class university | 2683 | 198 | 91 | 201 | 97 | 205 | 594 |

| Regular university | 1599 | 118 | 49 | 110 | 50 | 145 | 354 |

| Vocational college | 521 | 39 | 21 | 39 | 20 | 37 | 117 |

| Northeastern | Double World-Class university | 2068 | 177 | 82 | 200 | 83 | 166 | 531 |

| Regular university | 1532 | 131 | 57 | 144 | 69 | 123 | 393 |

| Vocational college | 501 | 43 | 18 | 37 | 29 | 45 | 129 |

| Total | | 19,434 | 1420 | 684 | 1440 | 707 | 1429 | 4260 |

| Control Variables | Number | Percentage % |

|---|

| Gender | | |

| Male | 706 | 49.72 |

| Female | 714 | 50.28 |

| Marital status | | |

| Married | 878 | 61.83 |

| Unmarried | 542 | 38.17 |

| Age | | |

| 35 or below | 312 | 21.97 |

| 36–45 | 373 | 26.27 |

| 46–55 | 360 | 25.35 |

| 56 or above | 375 | 26.41 |

| Majors | | |

| Social science | 757 | 53.31 |

| Natural science | 663 | 46.69 |

| Professional titles | | |

| Teaching assistant | 305 | 21.48 |

| Lecturer | 399 | 28.1 |

| Associate Professor | 436 | 30.7 |

| Professor | 280 | 19.72 |

| Years in service | | |

| 10 or less | 448 | 31.55 |

| 11–20 | 400 | 28.17 |

| 21–30 | 387 | 27.25 |

| 31 or above | 185 | 13.03 |

| Research Questions | Methodology | Hypotheses |

|---|

Does job performance influence job burnout among academic staff? How can a mechanism be developed to address job burnout crises among academics?

Does reducing job burnout play an important role in supporting the achievement of SDGs? | Quantitative

Linear regression, frequency trends

Results from RQ1 and RQ2 | Ha1: Academics’ “job performance” has a substantially detrimental impact on “job burnout” when all predictor variables are considered.