- Quick Solve

- Solution Wizard

- Clue Database

- Crossword Forum

- Anagram Solver

- Online Crosswords

Student's assignment - Crossword Clue

Below are possible answers for the crossword clue Student's assignment .

5 letter answer(s) to student's assignment

- a tentative attempt

- an analytic or interpretive literary composition

- make an effort or attempt; "He tried to shake off his fears"; "The infant had essayed a few wobbly steps"; "The police attempted to stop the thief"; "He sought to improve himself"; "She always seeks to do good in the world"

- prototype of a proposed postage stamp

- put to the test, as for its quality, or give experimental use to; "This approach has been tried with good results"; "Test this recipe"

Other crossword clues with similar answers to 'Student's assignment'

Still struggling to solve the crossword clue 'student's assignment'.

If you're still haven't solved the crossword clue Student's assignment then why not search our database by the letters you have already!

- Words By Letter:

- Clues By Letter:

- » Home

- » Quick Solve

- » Solution Wizard

- » Clue Database

- » Crossword Help Forum

- » Anagram Solver

- » Dictionary

- » Crossword Guides

- » Crossword Puzzles

- » Contact

© 2024 Crossword Clue Solver. All Rights Reserved. Crossword Clue Solver is operated and owned by Ash Young at Evoluted Web Design . Optimisation by SEO Sheffield .

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

STUDENT'S ASSIGNMENT Crossword clue

Crossword answers for student's assignment, top answers for: student's assignment.

| Clue | Answer | |

|---|---|---|

| Show 3 more hide | ||

STUDENT'S ASSIGNMENT Crossword puzzle solutions

3 Solutions - 0 Top suggestions & 3 further suggestions. We have 3 solutions for the frequently searched for crossword lexicon term STUDENT'S ASSIGNMENT. Furthermore and additionally we have 3 Further solutions for this paraphrase.

For the puzzel question STUDENT'S ASSIGNMENT we have solutions for the following word lenghts 5, 6 & 8.

Your user suggestion for STUDENT'S ASSIGNMENT

Find for us the 4nth solution for STUDENT'S ASSIGNMENT and send it to our e-mail (crossword-at-the-crossword-solver com) with the subject "New solution suggestion for STUDENT'S ASSIGNMENT". Do you have an improvement for our crossword puzzle solutions for STUDENT'S ASSIGNMENT, please send us an e-mail with the subject: "Suggestion for improvement on solution to STUDENT'S ASSIGNMENT".

Frequently asked questions for Student's assignment:

How many solutions do we have for the crossword puzzle student's assignment.

We have 3 solutions to the crossword puzzle STUDENT'S ASSIGNMENT. The longest solution is HOMEWORK with 8 letters and the shortest solution is ESSAY with 5 letters.

How can I find the solution for the term STUDENT'S ASSIGNMENT?

With help from our search you can look for words of a certain length. Our intelligent search sorts between the most frequent solutions and the most searched for questions. You can completely free of charge search through several million solutions to hundreds of thousands of crossword puzzle questions.

How many letters long are the solutions for STUDENT'S ASSIGNMENT?

The lenght of the solutions is between 5 and 8 letters. In total we have solutions for 3 word lengths.

More clues you might be interested in

- calm or tranquil

- give orders

- it might rock your world

- unattainable

- congratulatory cry

- south american capital

- latvian, e.g.

- latvian's capital

- appropriate

- Legal Notice

- Missing Link

- Made with love from Mark & Crosswordsolver.com

Crossword Solver

Wordle Solver

Scrabble Solver

Anagram Solver

Crossword Solver > Clues > Crossword-Clue: Ongoing

ONGOING Crossword Clue

| Answer | Letters | Options | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

- ingoing (85.71%)

- Locale of an ongoing thaw (72.88%)

- Longing (71.43%)

- for Longing (71.43%)

- ANGLING (71.43%)

- LONGING for (71.43%)

- LONGINGLY (71.43%)

- Former partners' ongoing fight? (64.17%)

- Angling area (60.22%)

- longing or yearning (60.22%)

- Ongoing saga

- ongoing time

- Ongoing drama

- Ongoing shows

- Ongoing Story

- Ongoing dispute

- Ongoing quarrel

- Ongoing stories

- Ongoing trouble

Know another solution for crossword clues containing Ongoing ? Add your answer to the crossword database now.

Filter Results

Popular Letters

- Ongoing with 7 Letters

additional Letters

Search Answers

Search crossword answers.

Select Length

For multiple-word answers, ignore spaces. E.g., YESNO (yes no), etc.

Student's writing assignment Crossword Clue

Here is the answer for the crossword clue Students writing assignment . We have found 40 possible answers for this clue in our database. Among them, one solution stands out with a 98% match which has a length of 5 letters. We think the likely answer to this clue is ESSAY .

Crossword Answer For Students writing assignment:

You can click on the tiles to reveal letter by letter before uncovering the full solution.

40 Potential Answers:

| Rank | Answer | Length | Source | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 98% | Students writing assignment | (5) | ||

| 7% | Some assignments for students (6) | (6) | ||

| 6% | Student | (5) | Eugene Sheffer | Sep 10, 2024 |

| 6% | Assign a nickname | (3) | ||

| 6% | Write | (3) | Universal | Aug 30, 2024 |

| 6% | Attorney's assignment | (9) | USA Today | Aug 30, 2024 |

| 6% | Assigned to a position | (9) | ||

| 6% | Assigned work to | (6) | USA Today | Aug 27, 2024 |

| 6% | Assigns to a role | (5) | ||

| 6% | Job assignment | (4) | Commuter | Aug 17, 2024 |

To get better results - specify the word length & known letters in the search.

Fresh Clues From Recent Puzzles

- Reptile which appeared on the New Zealand 5c coin (7) Crossword Clue

- Wind in the Willows character Crossword Clue Mirror Tea Time

- There may be a reef of gold in US state (5) Crossword Clue

- Weaver in A Midsummer Night's Dream (6) Crossword Clue

- Coconut curry noodle soup, popular in Malaysia and Singapore Crossword Clue

- A winner very often shows courage Crossword Clue

- Mafia boss Crossword Clue Eugene Sheffer

- "I agree with you one hundred percent!" Crossword Clue

- Doctrine Crossword Clue Thomas Joseph

- What a house cleaner does Crossword Clue

Your Crossword Clues FAQ Guide

What are the top solutions for students writing assignment .

We found 40 solutions for Students writing assignment. The top solutions are determined by popularity, ratings and frequency of searches. The most likely answer for the clue is ESSAY.

How many solutions does Students writing assignment have?

With crossword-solver.io you will find 40 solutions. We use historic puzzles to find the best matches for your question. We add many new clues on a daily basis.

How can I find a solution for Students writing assignment ?

With our crossword solver search engine you have access to over 7 million clues. You can narrow down the possible answers by specifying the number of letters it contains. We found more than 40 answers for Students writing assignment.

Crossword Answers

- Eugene Sheffer

- LA Times Daily

- New York Times

- The Telegraph Quick

- Thomas Joseph

- Wall Street Journal

- See All Crossword Puzzles

Crossword Finders

- Search by Clue

- Search by Puzzle

- Search by Answer

- Crowssword Hints

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply —use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

‘I No Longer Give Grades on Student Writing Assignments, and It’s the Best Thing Ever!’

- Share article

(This is the third post in a five-part series. You can see Part One here and Part Two here .)

The new question-of-the-week is:

How do you get students to want to revise their writing?

In Part One , Melissa Butler, Jeremy Hyler, Jenny D. Vo, and Mary Beth Nicklaus shared their recommendations. All four were guests on my 10-minute BAM! Radio Show . You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

In Part Two , Matthew Johnson, Emily Phillips Galloway, Robert Jiménez, Holland White, Joy Hamm, and Alexandra Frelinghuysen offered their commentaries.

Today, Alexis Wiggins, Keisha Rembert, Alicia Kempin, Sara Holbrook, and Michael Salinger contribute their ideas.

“Publishable” and “Not Yet Publishable”

Alexis Wiggins has worked as a high school English teacher, instructional coach, and consultant. Her book, The Best Class You Never Taught: How Spider Web Discussion Can Turn Students into Learning Leaders (ASCD), helps transform classrooms through collaborative inquiry. Alexis is currently the English Department chair at the John Cooper School in The Woodlands, Texas. You can contact her or sign up for her newsletter :

That is the $64,000 question. For much of my career, I’ve prided myself on assigning engaging writing assignments that students will want to write and revise with enthusiasm. At least that is what I’ve told myself. But is enthusiasm the same thing as making all the students revise? Most people would say it is not.

Years ago, I tried my hand at something very different, something that aimed for enthusiastic, student-driven revision. I was inspired by an idea I got from my father, education reformer Grant Wiggins, who referenced a university professor that never gave grades on his writing rubrics but instead assigned one of two categories: “Publishable” and “Not Yet Publishable.”

I knew for high school students, I would need more detail and scaffolding to help them make sense of a new kind of assessment and feedback, so I built a more comprehensive rubric and added a third column called “Revisable.” I told my students that “Publishable” was A work, “Revisable” was anywhere between a B+ and a D-, and “Redo” had just completely missed the mark because the assignment had not yet been fulfilled. I allowed my students to revise their papers as many times as they wanted to until they reached “Publishable” status and was fascinated with the results. My students largely worked their tails off to eventually move from the “Revisable” column to the “Publishable” column. The downside? It was killing me .

I couldn’t handle the volume of revisions I was confronted with and the amount of comments I had to write out on every single draft submitted to provide adequate feedback to help students revise and improve. As a result, I abandoned the practice after one year.

But a decade has passed since then, and I have spent much of those 10 years working on developing assessment criteria and rubrics at the schools. In recent years, I’ve suspected that with more targeted work on standards-based rubrics, this revision system could be more manageable and highly beneficial to students.

Instead of spending hours writing out comments or correcting student errors, the rubrics themselves are designed backwards from the end goal: persuasive, eloquent use of language and argument. With the specific criteria spelled out clearly on the rubrics, I only have to check the category it falls into under each standard (Publishable, Revisable, and Redo) and leave a quick note as to what the student can do to revise and strengthen that criterion if not yet Publishable.

I might add some additional marks on the paper itself, but these are now minimal thanks to the targeted rubrics. I experimented this past year with my senior Film and Composition class, a yearlong English course that I teach by myself and found my grading time was greatly reduced, even as the volume of submissions increased.

The rubric I designed is detailed and specific to my class—it may not be the right rubric or standards for you—but I believe the principles behind it can be applied successfully to other classes and age groups.

The key idea here in my “Wiggins Assessment Method” is that students never receive a grade on any assignments; they only ever get “Publishable,” “Revisable,” or “Redo” on their rubrics, and at the end of their semester, their grade is determined by a breakdown of how many assessments are in each of those categories (these details are spelled out on the back of the rubric linked above). They can revise as many times as they would like to before a clearly communicated due date near the end of each semester. For example, if they have three publishable and two revisable assignments by the end of the semester, their grade is an A-. If they want to do better, they keep revising up until the final deadline before the semester’s end.

The results with this standards-based rubric and more targeted feedback process? The best system I have ever experienced in my 20-year career, hands down.

I used to dread grading papers. Dread, loathe, and avoid. Now, with such a detailed, pared-down rubric, my grading time has been cut in half. The rubric does most of the work for me, and office hours take care of the rest.

The reason I most dreaded grading before wasn’t so much the time commitment as the fear of how a student would respond emotionally to the grade I gave them. With my new assessment method, there are no more fraught emotions because there are no grades on individual assignments. We just look at the work together and discuss what changes are necessary to get the work “Publishable.” Sometimes students are satisfied with their progress and decide to stop revising before the assessment is “Publishable,” allowing them to better own their process and choose the final semester grade they are comfortable with.

Students have reported nearly unanimously in surveys that they have improved, wanted to revise their work, and paid attention to teacher feedback more than ever with this new system. Nineteen out of 20 of my students said this was the best style of assessment they had ever experienced and that all teachers should use it. They note that it allows them to be in control of their grades, their revision process, and their learning overall. Repeatedly, students commented on how this system reduced their stress level while increasing their learning and growth.

I’m a convert; I’ll never go back to teaching Film any other way, and I hope to try this method with other age groups soon. I can honestly say that with this method, I actually look forward to grading my students’ papers, and they are motivated to keep improving their writing entirely on their own. Win-win.

My summary: “I no longer give grades on student writing assignments, and it’s the best thing ever!”

“We revise pieces of my work together”

Keisha Rembert is a passionate learner and fierce equity advocate. She was an award winning middle school ELA and United States History teacher who now instructs preservice teachers. She hopes to change our world one student at a time. Twitter ID: @klrembert:

Students often tell me that writing is overwhelming for them. When I dig a bit deeper to understand, they usually say, in not these exact words but close enough, writing and revision is less about expression and more about judgment: You did not include a comma here, check your word choice there. The complexities of writing are so vast (grammar, semantics, spelling, organization, etc.) for them that it is exhausting, and they just want the process to be done.

My retort is that I want to free them from their fears of judgment and have them experience the joys of revision. We revise pieces of my work together and talk about it. We acknowledge that mistakes are opportunities. I share that the reality is we rarely get things entirely right the first time. Revision is where we find the golden parts of our voice and the opportunity to clarify and expand on those golden pieces.

Revision is also a communal process. This, I think inspires students to want to make it better. After reading the work of a friend, they often discover new thoughts and ideas to make their piece better. Revision in my classes is about community. It is talking out ideas with others and sharing information which is the heart of good writing and the revision process. Getting students to see that writing is messy, and perfection is the enemy of progress especially when it comes to writing, helps them realize their messiness if appreciated and something to embrace. It relieves the pressure of having to do it right, always.

A growth mindset

Alicia Kempin is a fourth-grade teacher at The Windward School , a preeminent independent school in New York which provides a proven instructional program to children with language-based learning disabilities. She enjoys sharing her love of reading, writing, and math with her students:

As a teacher of students with language-based learning challenges, it’s often difficult to get children to write, let alone revise their writing! There are, however, several strategies I use to encourage the revising and editing process with my students.

I have found that one of the most effective ways to demonstrate the importance of revising and editing to my students is by completing unelaborated paragraphs together. This is an engaging writing activity in which I purposely prepare a terribly written paragraph on a topic with which the children are familiar. (Of course, I do not tell them that I intentionally wrote a bad paragraph; that’s part of the fun!) I display this awful paragraph on the white board, read it to the students, and ask them what they think. Inevitably, these honest children will tell me it’s horrible. So, I tell the children that the goal today is to improve my writing by revising and editing it. (They love that they get to improve MY writing!) We do several of these activities together as a class and use a revising and editing checklist that prompts them to use particular writing strategies. For example, I might say “Improve the topic sentence by adding an appositive” or “Answer the question words when and why to expand the sentence.”

After we complete all the revising suggestions, we read the original paragraph once more, followed by the revised paragraph—and what a difference! The children not only see the side by side comparison of the first paragraph compared to the revised paragraph, but they also hear the difference. I believe that hearing the original and revised paragraphs really helps the children to internalize how a paragraph can be improved. These unelaborated paragraphs can then be followed with children writing paragraphs of their own with some teacher directed revising goals which are more general such as “Improve topic sentence” or “Expand detail sentence two.” Ultimately, the hope would be to have the students eventually internalize these strategies and not even need revising goals.

Another strategy I use to encourage revising is to build enthusiasm for vocabulary. I do this throughout our reading and writing lessons by directly teaching vocabulary words and by modeling more advanced vocabulary in my oral language. For example, if we are discussing a book in which a character is sad, I might ask, “What is another adjective we can use to describe how that character is feeling?” I would try to elicit the words heartbroken, devastated, crushed, etc. That translates into our writing process when the children have completed their rough drafts, and I ask them to look for words that might have “juicier or more flavorful” synonyms. We work to elevate vocabulary throughout the year and challenge each other to use more interesting words. Fourth graders really seem to love words like flabbergasted and astonished! When the children know and use these words regularly, it’s easier for them to revise their writing and look for words they can “elevate.”

Perhaps the most meaningful strategy I use with my fourth graders is to model and encourage a growth mindset about writing and revising. I start by sharing some writing that I have completed and then show them the pages and pages of revisions that I made in order to get there. It is important for children to see that good writers look for ways to improve their writing. This is also when I tell the class a secret: that an eraser is an opportunity to improve—not just a tool to “fix mistakes.” Embracing a growth mindset in the classroom allows children to feel safe in taking chances, and it is a natural intrinsic motivator. I have found that what the children want more than anything is to take ownership of their own improvement. And let me tell you something—the children beam with pride when they see the results of their effort!

Encouraging a love of writing and revising takes an extraordinary amount of work and enthusiasm on the teacher’s part. By allowing children to view writing as a fun, engaging process, rather than as a laborious product, they become motivated to grow and improve as writers.

Instead of “drafts,” call them “versions”

Sara Holbrook is a novelist, poet, and educator with a multitude of books for both teachers and students under her belt, including The Enemy: Detroit, 1954, which won the 2018 Jane Addams Children’s Book Award.

Michael Salinger is a poet, performer, and advocate of poetry and performance in education.

Together, they co-founded and direct Outspoken Literacy Consulting, an organization that runs programs to help K–12 students in the United States and around the world develop writing, public speaking, and comprehension strategies:

Labels matter. The first thing we do is ask every writer to label every new piece of writing “Version 1.” This makes it clear from the beginning that this is an embryonic document. We use the word “draft” as a verb. There are no “first drafts” in our writing workshops because a first draft just sounds like a throw away. Instead, we take Version 1 and begin to tinker with it. Change a sentence? Add an adjective? Writers are on Version 2, and the process continues.

We begin very simply and then increase complexity with subsequent revisions. A writing lesson might go like this:

- Think of a simile comparison regarding XYZ. (This is Version 1.)

- Use that to develop a more complete description of your subject matter. (This is Version 2.)

- Can you add some sensory terms to bring the reader into the scene? (This is Version 3.)

- Bring a character into the situation. What would that character say? (This is Version 4.)

How did we come up with this approach? This is how we write. We are both trade book authors and writers of professional development books. Before that, we were both business writers—Michael was an engineer for 23 years and Sara was in public relations. We deconstructed our writing practice and realized a couple important things:

- We never start at the beginning of a long piece of writing, develop a story arc according to some predetermined pattern, and then use a rubric to make it right.

- All writing is creative. Any time we begin with a blank page and put words on it, it is a creative process.

When we visit schools, we show teachers how they can use simple frameworks to help students jump start their writing by starting with Version 1. We show them how we guide students through the next couple versions. Writers will discard the framework as the writing takes off on its own, kind of like taking off the jumper cables after the car is running.

Kids intuitively get it. We compare the writing process to playing a video game or learning a sport; people start with simple moves and level up. Students begin to internalize the reality that revision is incremental and writing is always an evolving process. We’ve found that the teachers we work with are excited by this writing process, and even relieved. Start simple and add complexity is a recipe for success as students adopt an “I can do that,” attitude.

We actually have kids bragging,

“I’m on Version 6!”

“Oh, yeah? I’m on Version 13!”

But one of our favorite lines to hear from kids is, “Oh, don’t worry, just put it down. It’s only Version 1.” We reinforce that no one expects the first version to be perfect, it’s just something to build on. And then we offer choices on how to take that next step.

We also invite students to share aloud throughout the writing process. By reading aloud, Version 1 and Version 2, partnering, or working with a mini writers’ group, students are able to see and hear their own progress as writers. We’ll ask, “Which version is working better for you?” Then we’ll let the writer explain what made the revised version better and where they want to take it next.

By building revision into the beginning of the writing process rather than leaving it until end, students are eager to add complexity and clarity to their writing.

Thanks to Alexis, Keisha, Alicia, Sara and Michael for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email (The RSS feed for this blog, and for all Ed Week articles, has been changed by the new redesign - new ones won’t be available until late January). And if you missed any of the highlights from the first nine years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below.

This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

Race & Racism in Schools

School Closures & the Coronavirus Crisis

Classroom-Management Advice

Best Ways to Begin the School Year

Best Ways to End the School Year

Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

Implementing the Common Core

Facing Gender Challenges in Education

Teaching Social Studies.

Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

Using Tech in the Classroom

Student Voices

Parent Engagment In Schools

Teaching English-Language Learners

Reading Instruction

Writing Instruction

Education Policy Issues

Differentiating Instruction

Math Instruction

Science Instruction

Advice for New Teachers

Author Interviews

Entering the Teaching Profession

The Inclusive Classroom

Learning & the Brain

Administrator Leadership

Teacher Leadership

Relationships in Schools

Professional Development

Instructional Strategies

Best of Classroom Q&A

Professional Collaboration

Classroom Organization

Mistakes in Education

Project-Based Learning

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Big Fresh Newsletter

- Leaders Lounge

- Live Events

- Book Guides

- Contributors

Literacy Letters: Helping New Students Understand Ongoing Assignments

Katie Doherty

How do teachers bring new students up to speed with ongoing assignments? In this video from Katie Doherty’s middle school classroom, Katie presents the latest “Literary Letters” assignment to her...

Membership Required

The rest of this content is restricted to Choice Literacy members.

Join us today for instant access and member-only features:

Get full access to all Choice Literacy article content

Get full access to all Choice Literacy video content

Product Discounts

Receive members-only product discounts for online courses, DVDs, books and more

Back to top

Katie Doherty is an avid reader and writer. And who better to read and write with than a gaggle of 6th graders in Portland, Oregon? Through reading and writing workshops in her 6th grade language arts classroom, Katie and her students work to build the essential community they need to thrive as readers, writers, learners, and thinkers. Together, they all learn to take risks.

Related Articles

Literacy Rights and Responsibilities

Something bad was happening in Katie Doherty’s middle school classroom—it was time to rebuild the class community with a reality check.

Clearing Up Confusion

Katie Doherty works closely with a student who has an unusual request – he wants to take home a basal anthology for "pleasure reading." She puts a different text in his hands, and uses what she learns from the experience to design a for lesson her 6th grade students.

The Triple Threat: Building a Community, Discussion Skills, and Writing Stamina

Katie Doherty knows how to pick the right text to move from whole-class conversations to writing.

Related Videos

6th Grade Classroom Room Tour

Katie Doherty shares how she has organized her 6th grade classroom to support students at her bustling middle school.

Quick Take: Katie Doherty on Middle School Reading Workshop Choices

In this two-minute Quick Take video, Katie Doherty explains the choices students have in her sixth-grade reading workshop.

“I Am the One Who . . .” Building Writing Skills and Community in Middle Schools

In this 12-minute video, Katie Doherty leads her sixth-grade students as they try the prompt “I am the one who . . .” during writing workshop. This is an excellent activity for building classroom community.

Choice Literacy is a community of passionate educators who lead. Come join us!

Get free articles and insights delivered to your inbox every week with the Choice Literacy "Big Fresh" Newsletter!

© 2024 The Lead Learners. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions

Website built by MemberDev

Lost your password?

Choose the area of the site you want to search:

5 effective constructive feedback examples: Unlocking student potential

This video provides an overview of the key features instructors need to know to make best use of Feedback Studio, accessed through the Turnitin website.

At Turnitin, we’re continuing to develop our solutions to ease the burden of assessment on instructors and empower students to meet their learning goals. Turnitin Feedback Studio and Gradescope provide best-in-class tools to support different assessment types and pedagogies, but when used in tandem can provide a comprehensive assessment solution flexible enough to be used across any institution.

By completing this form, you agree to Turnitin's Privacy Policy . Turnitin uses the information you provide to contact you with relevant information. You may unsubscribe from these communications at any time.

Providing constructive feedback examples to students is an important part of the learning journey and is crucial to student improvement. It can be used to feed a student’s love of learning and help build a strong student-teacher relationship. But it can be difficult to balance the “constructive” with the “feedback” in an effective way.

On one hand, we risk the student not absorbing the information, and therefore missing an opportunity for growth when we offer criticism, even when constructive. On the other hand, there is a risk of discouraging the student, dampening their desire to learn, or even harming their self-confidence. Further complicating the matter is the fact that every student learns differently, hears and absorbs feedback differently, and is at a different level of emotional and intellectual development than their peers.

We know that we can’t teach every student the exact same way and expect the same results for each of them; the same holds true for providing constructive feedback examples. For best results, it’s important to tailor how constructive feedback is provided based on content, student needs, and a variety of other factors.

In this blog, we’ll take a look at constructive feedback examples and the value of effective instructor feedback, centering on Dr. John Hattie’s research on “Where to next?” feedback. We’ll also offer key examples for students, so instructors at different grade levels can apply best practices right away.

In 1992 , Dr. John Hattie—in a meta-analysis of multiple scientific studies—found that “feedback has one of the positive influences on student achievement,” building on Sadler’s concept that good feedback can close the gap between where students are and where they aim to be (Sadler, 1989 ).

But before getting too far into specifics, it would be helpful to talk about what “constructive feedback” is. Not everyone will define it in quite the same way — indeed, there is no singular accepted definition of the phrase.

For example, a researcher in Buenos Aires, Argentina who studies medical school student and resident performance, defines it, rather dryly, as “the act of giving information to a student or resident through the description of their performance in an observed clinical situation.” In workplace scenarios , you’ll often hear it described as feedback that “reinforces desired behaviors” or, a definition that is closer to educators’ goals in the classroom, “a supportive way to improve areas of opportunity.”

Hattie and Clarke ( 2019 ) define feedback as the information about a learning task that helps students understand what is aimed to be understood versus what is being understood.

For the purposes of this discussion, a good definition of constructive feedback is any feedback that the giver provides with the intention of producing a positive result. This working definition includes important parts from other, varied definitions. In educational spaces, “positive result” usually means growth, improvement, or a lesson learned. This is typically accomplished by including clear learning goals and success criteria within the feedback, motivating students towards completing the task.

If you read this header and thought “well… always?” — yes. In an ideal world, all feedback would be constructive feedback.

Of course, the actual answer is: as soon, and as often, as possible.

Learners benefit most from reinforcement that's delivered regularly. This is true for learners of all ages but is particularly so for younger students. It's best for them to receive constructive feedback as regularly, and quickly, as possible. Study after study — such as this one by Indiana University researchers — shows that student information retention, understanding of tasks, and learning outcomes increase when they receive constructive feedback examples soon after the learning moment.

There is, of course, some debate as to precise timing, as to how soon is soon enough. Carnegie Mellon University has been using their proprietary math software, Cognitive Tutor , since the mid-90s. The program gives students immediate feedback on math problems — the university reports that students who use Cognitive Tutor perform better on a variety of assessments , including standardized exams, than their peers who haven’t.

By contrast, a study by Duke University and the University of Texas El Paso found that students who received feedback after a one-week delay retained new knowledge more effectively than students who received feedback immediately. Interestingly, despite better performance, students in the one-week delayed feedback group reported a preference for immediate feedback, revealing a metacognitive disconnect between actual and perceived effectiveness. Could the week delay have allowed for space between the emotionality of test-taking day and the calm, open-to-feedback mental state of post-assessment? Or perhaps the feedback one week later came in greater detail and with a more personalized approach than instant, general commentary? With that in mind, it's important to note that this study looked at one week following an assessment, not feedback that was given several weeks or months after the exam, which is to say: it may behoove instructors to consider a general window—from immediate to one/two weeks out—after one assessment and before the next assessment for the most effective constructive feedback.

The quality of feedback, as mentioned above, can also influence what is well absorbed and what is not. If an instructor can offer nuanced, actionable feedback tailored to specific students, then there is a likelihood that those students will receive and apply that constructive feedback more readily, no matter if that feedback is given minutes or days after an assessment.

Constructive feedback is effective because it positively influences actions students are able to take to improve their own work. And quick feedback works within student workflows because they have the information they need in time to prepare for the next assessment.

No teacher needs a study to tell them that motivated, positive, and supported students succeed, while those that are frustrated, discouraged, or defeated tend to struggle. That said, there are plenty of studies to point to as reference — this 2007 study review and this study from 2010 are good examples — that show exactly that.

How instructors provide feedback to students can have a big impact on whether they are positive and motivated or discouraged and frustrated. In short, constructive feedback sets the stage for effective learning by giving students the chance to take ownership of their own growth and progress.

It’s one thing to know what constructive feedback is and to understand its importance. Actually giving it to students, in a helpful and productive way, is entirely another. Let’s dive into a few elements of successful constructive feedback:

When it comes to providing constructive feedback that students can act on, instructors need to be specific.

Telling a student “good job!” can build them up, but it’s vague — a student may be left wondering which part of an assessment they did good on, or why “good” as opposed to “great” or “excellent” . There are a variety of ways to go beyond “Good job!” on feedback.

On the other side of the coin, a note such as “needs work” is equally as vague — which part needs work, and how much? And as a negative comment (the opposite of constructive feedback), we risk frustrating them or hurting their confidence.

Science backs up the idea that specificity is important . As much as possible, educators should be taking the time to provide student-specific feedback directly to them in a one-on-one way.

There is a substantial need to craft constructive feedback examples in a way that they actively address students’ individual learning goals. If a student understands how the feedback they are receiving will help them progress toward their goal, they’re more likely to absorb it.

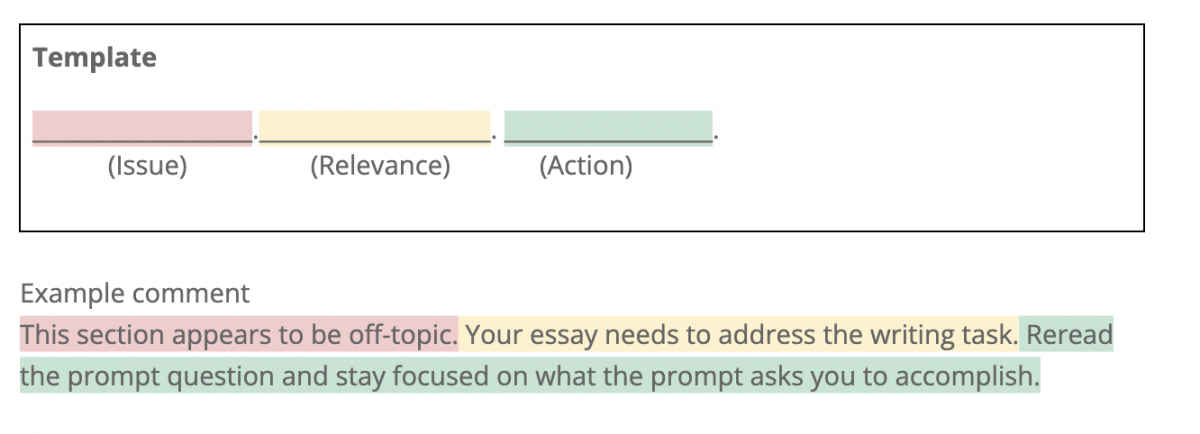

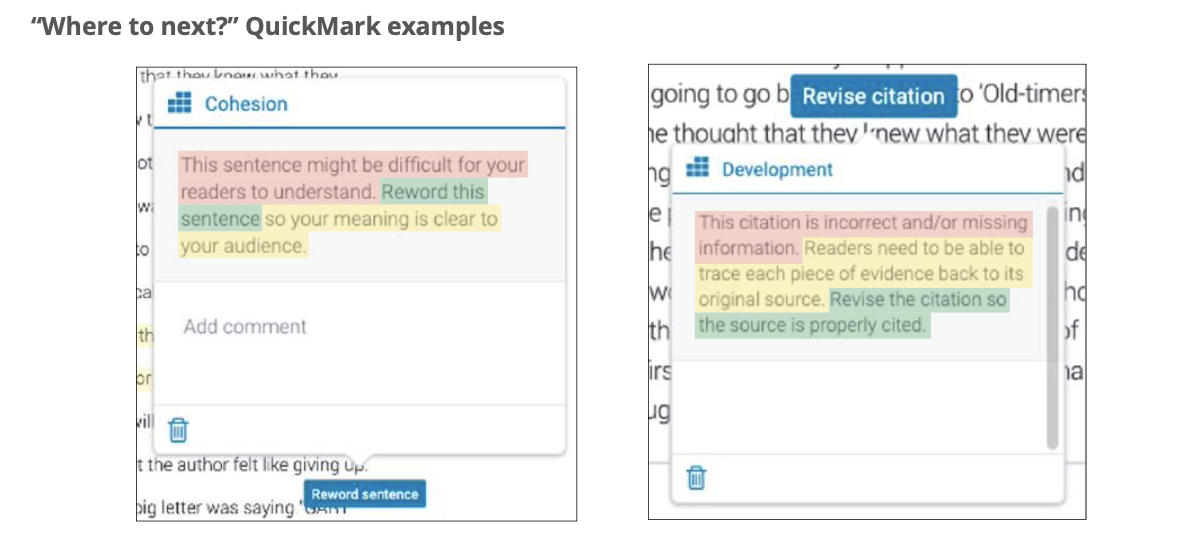

Our veteran Turnitin team of educators worked directly with Dr. John Hattie to research the impact of “Where to next?” feedback , a powerful equation for goal-oriented constructive feedback that—when applied formatively and thoughtfully—has been shown to dramatically improve learning outcomes. Students are more likely to revise their writing when instructors include the following three essential components in their feedback:

- Issue: Highlighting and clearly describing the specific issue related to the writing task.

- Relevance: Aligning feedback explicitly to the stated expectations of the assignment (i.e. rubric).

- Action: Providing the learner with their “next steps,” appropriately guiding the work, but not giving away the answer.

It’s also worth noting that quality feedback does not give the answer outright to the student; rather, it offers guidelines and boundaries so the students themselves can do their own thinking, reasoning, and application of their learning.

As mentioned earlier, it's hard to balance the “constructive” with the “feedback” in an effective way. It’s hard, but it’s important that instructors learn how to do it, because how feedback is presented to a student can have a major impact on how they receive it .

Does the student struggle with self confidence? It might be helpful to precede the corrective part of the feedback acknowledging something they did well. Does their performance suffer when they think they’re being watched? It might be important not to overwhelm them with a long list of ideas on what they could improve.

Constructive feedback examples, while cued into the learning goals and assignment criteria, also benefit from being tailored to both how students learn best and their emotional needs. And it goes without saying that feedback looks different at different stages in the journey, when considering the age of the students, the subject area, the point of time in the term or curriculum, etc.

In keeping everything mentioned above in mind, let’s dive into five different ways an instructor could give constructive feedback to a student. Below, we’ll look at varying scenarios in which the “Where to next?” feedback structure could be applied. Keep in mind that feedback is all the more powerful when directly applied to rubrics or assignment expectations to which students can directly refer.

Below is the template that can be used for feedback. Again, an instructor may also choose to couple the sentences below with an encouraging remark before or after, like: "It's clear you are working hard to add descriptive words to your body paragraphs" or "I can tell that you conducted in-depth research for this particular section."

For instructors with a pile of essays needing feedback and marks, it can feel overwhelming to offer meaningful comments on each one. One tip is to focus on one thing at a time (structure, grammar, punctuation), instead of trying to address each and every issue. This makes feedback not only more manageable from an instructor’s point of view, but also more digestible from a student’ s perspective.

Example: This sentence might be difficult for your readers to understand. Reword this sentence so your meaning is clear to your audience.

Rubrics are an integral piece of the learning journey because they communicate an assignment’s expectations to students. When rubrics are meaningfully tied to a project, it is clear to both instructors and students how an assignment can be completed at the highest level. Constructive feedback can then tie directly to the rubric , connecting what a student may be missing to the overarching goals of the assignment.

Example: The rubric requires at least three citations in this paper. Consider integrating additional citations in this section so that your audience understands how your perspective on the topic fits in with current research.

Within Turnitin Feedback Studio, instructors can add an existing rubric , modify an existing rubric in your account, or create a new rubric for each new assignment.

QuickMark comments are sets of comments for educators to easily leave feedback on student work within Turnitin Feedback Studio.

Educators may either use the numerous QuickMarks sets readily available in Turnitin Feedback Studio, or they may create sets of commonly used comments on their own. Regardless, as a method for leaving feedback, QuickMarks are ideal for leaving “Where to next?” feedback on student work.

Here is an example of “Where to next?” feedback in QuickMarks:

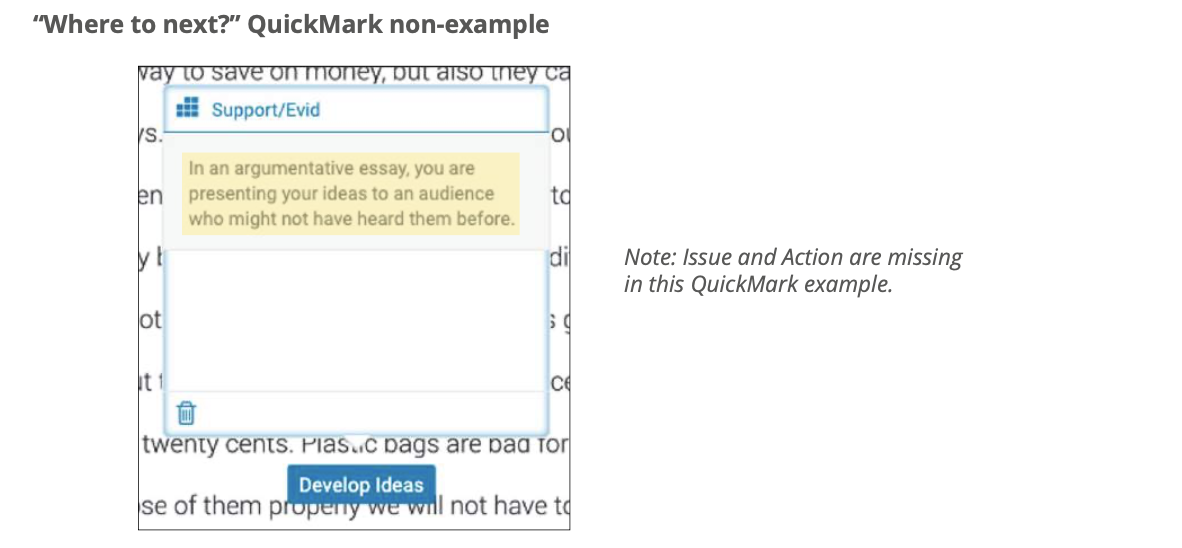

It can be just as helpful to see a non-example of “Where to next?” feedback. In the image below, a well-meaning instructor offers feedback to a student, reminding them of what type of evidence is required in an argumentative essay. However, Issue and Action are missing, which leaves the student wondering: “Where exactly do I need to improve my support? And what next steps ought to be taken?”

Here is a non-example of “Where to next?” feedback in QuickMarks:

As an instructor in a STEM class, one might be wondering, “How do I apply this structure to my feedback?” While “Where to next?” feedback is most readily applied to English Language Arts/writing course assignments, instructors across subject areas can and should try to implement this type of feedback on their assignments by following the structure: Issue + Relevance + Action. Below is an example of how you might apply this constructive feedback structure to a Computer Science project:

Example: The rubric asks you to avoid “hard coding” values, where possible. In this line, consider if you can find a way to reference the size of the array instead.

As educators, we have an incredible power: the power to help struggling students improve, and the power to help propel excelling students on to ever greater heights.

This power lies in how we provide feedback. If our feedback is negative, punitive, or vague, our students will suffer for it. But if it's clear, concise, and, most importantly, constructive feedback, it can help students to learn and succeed.

Study after study have highlighted the importance of giving students constructive feedback, and giving it to them relatively quickly. The sooner we can give them feedback, the fresher the information is in their minds. The more constructively that we package that feedback, the more likely they are to be open to receiving it. And the more regularly that we provide constructive feedback examples, the more likely they are to absorb those lessons and prepare for the next assessment.

The significance of providing effective constructive feedback to students cannot be overstated. By offering specific, actionable insights, educators foster a sense of self-improvement and can truly help to propel students toward their full potential.

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

fa51e2b1dc8cca8f7467da564e77b5ea

- Make a Gift

- Join Our Email List

- Beyond “the Grade”: Alternative Approaches to Assessment

While so-called "alternative" approaches to grading are not new, attention to them has increased in recent years. This has been especially true since 2020, when COVID's disruption of our conventional modes of in-person education forced many instructors to rethink their approaches to assessment. Hand in hand with this more pragmatic rethinking came ethical considerations, as living through a pandemic unfolded alongside ongoing protests throughout the US against systemic racism and police violence, further leading instructors to question the biases inherent in, and efficacy of, the models they had long been using.

Among the alternative grading approaches that have received the most attention are specifications grading , contract grading , mastery grading , and " ungrading ." Each of these approaches is "alternative" in so far as it diverges in some way from a so-called traditional model of grading, which in its simplest and oversimplified form generally includes many of the following features:

Grades are given by the instructor to each individual student

The grade is often, but not necessarily, accompanied by more substantive feedback

Graded assignments are "high stakes," often because they are few in number, come later in the term, and/or may not be revised or resubmitted

Students have little say in creating assignments or in which assignments they complete

Students have little say in setting their own learning goals and few opportunities to reflect on their work in a course.

In practice, these general features of so-called "traditional" grading show up in different combinations in any given course. Overall, courses employing "traditional" grading tend to be more oriented towards product over process, and instructors in these courses hold more power over the assessment process than students do. Nonetheless, courses that employ traditional grading are not uniform in the ways in which student learning is assessed and graded.

We encourage Harvard instructors to learn about and consider adopting some or all of the features of one or more of these alternative approaches to grading not because we consider traditional approaches to be inherently flawed, ineffective, or obsolete, but rather because we believe that contemplating alternative approaches in tandem with more conventional practices inevitably raises valuable questions not only about the particulars of how we are assessing our students' learning, but also about why we are asking students to perform in the ways that we are. To recognize that there are a wide array of plausible approaches to grading is to recognize that perhaps the single most important attribute of successful assessment schemes is their intentionality.

Why Consider Alternative Grading?

Criticisms of traditional grading systems include:

Grading systems exacerbate stress and mental health challenges among students (Horowitz and Graf, 2019; Jones, 1993).

Grades decrease students' intrinsic motivation (Pulfrey et al, 2011; Chamberlain et al, 2018).

Grading decreases students' ability to learn from feedback, as students tend to focus on a letter/numerical grade and not the accompanying feedback (Schinske & Tanner, 2017; Kuepper-Tetzel & Gardner, 2021).

Grading perpetuates inequities between students (Link & Guskey 2019; Malouff & Thorsteinsson, 2016; Feldman, 2018).

They may encourage students to be risk averse, nudging them towards courses and assignments in which they feel they can do well at the expense of new areas of potential interest and inquiry.

To combat these challenges, in recent years a significant number of individual faculty, educational researchers, and institutions from across higher education have invested in developing alternative approaches to grading—often referred to, broadly, as ungrading. While the exact details vary, these approaches typically:

Offer clear learning objectives that are aligned with how assignments are graded.

Provide transparent expectations for success.

Offer students regular and actionable feedback on their work.

Emphasize process over product, by providing students with multiple opportunities to meet expectations. If a student's first effort is not satisfactory, they may be able to revise and resubmit the work or complete another similar assignment.

Help students feel responsible for their learning and their grades by providing students with some agency over the breadth and depth of work that they undertake and giving students agency in defining their own goals and reflecting on their own growth as learner.

Offer a range of lower-stakes assignments, as opposed to a small number of higher-stakes assessments such as exams.

Overall, alternative grading aspires to recalibrate the way we evaluate and give feedback on students' work to incentivize learning and effort (rather than performance alone). These approaches provide clarity about expectations and provide students with the freedom to make mistakes as part of the natural process of learning.

A Brief Typology of Alternative Grading Approaches

Below we briefly describe four alternative grading strategies, which can be employed in a wide range of disciplines. We note that there is a lot of flexibility as to how instructors might implement any of these approaches, and that the approaches overlap with each other.

Specifications grading

In specifications grading, grades are based on the combination and number of assignments that students satisfactorily complete. The instructor designates bundles of assignments that map to different letter grades. Bundles that require more work and are more challenging correspond to higher grades. Students can choose which bundle(s) they would like to complete.

Similar to mastery grading, the instructor defines clear learning objectives for all aspects of the course. Grading is based on meeting these objectives (satisfactory/unsatisfactory). Students typically have a small number of opportunities to resubmit work that didn't meet the standards.

Contract grading

With contract grading, the criteria for grades are determined by an agreement between the instructor and students at the beginning of the term. Each student signs a contract indicating what grade they plan to work towards, and contracts can be revisited during the term. Grades may correspond to completion of a certain percentage of work or completion of designated bundles of assignments (similar to specifications grading). Contract grading often emphasizes the learning process over the product, and as such, grading schemes may reward completion of activities (such as completing drafts and meeting individually with the instructor) as well as behaviors (such as being thoughtful in peer reviews and participating in discussions). Student work is graded on a satisfactory/unsatisfactory basis.

Mastery grading

In mastery grading, grades are directly based on the degree to which students have met the course learning objectives. An instructor first develops an extensive list of learning objectives, and then creates assessments that are aligned with these objectives. Student work is assessed on the basis of whether or not it meets a specified subset of the course objectives; partial credit is not awarded. Students are allowed multiple attempts to show mastery; depending on the nature of the assignment, students might revise their original submission or submit new work in response to related questions. The final course grade is based on the total number of objectives that the students has mastered. An instructor might designate essential objectives that everyone must meet to receive a certain grade, as well as bonus objectives that students could meet for a higher grade.

In classes that utilize ungrading, students are responsible for reflecting on and assessing their own learning. Instructors provide regular feedback on student work, but feedback on individual assignments does not include a grade. Instructors provide extensive guidance to help students reflect on their progress towards meeting their own learning goals. At the end of the term (and often at the midterm), students assemble a portfolio of work and assign themselves an overall grade for their course work. Final grades are at the discretion of the instructor; many instructors report that it is more common that they decide to increase—rather than decrease—the grade that students assigned themselves.

Support for Alternative Grading

Harvard faculty members who employ alternative grading strategies see themselves as a mentor and coach; they note that providing extensive feedback and mentoring can be more time-intensive than traditional grading. Faculty also note that alternative grading requires a high degree of trust between students and instructors. Nonetheless, the benefits are great: faculty feel that they can focus on fostering students' growth and learning, without judging or ranking their students. Moreover, students develop a sense of agency about their learning.

The Bok Center would be happy to meet with faculty who are interested in modifying their approaches to grading. We encourage faculty to identify elements that resonate with your goals and to incorporate small changes into your teaching.

For more information ...

Blum, & Kohn, A. (2020). Ungrading (First edition). West Virginia University Press.

Chamberlin, K., Yasué, M., & Chiang, I.-C. A. (2018). The impact of grades on student motivation. Active Learning in Higher Education .

Feldman, J. (2018). Grading for equity: What it is, why it matters, and how it can transform schools and classrooms . Corwin Press.

Horowitz, J. M., & Graf, N. (2019). Most US teens see anxiety and depression as a major problem among their peers. Pew Research Center, 20.

Jones, R. W. (1993). Gender-specific differences in the perceived antecedents of academic stress. Psychological Reports, 72(3), 739-743.

Malouff, J. & Thorsteinsson, E. (2016). "Bias in grading: A meta-analysis of experimental research findings. Australian Journal of Education .

Pulfrey, C., Buchs, C., & Butera, F. (2011). "Why grades engender performance-avoidance goals: The mediating role of autonomous motivation." Journal of Educational Psychology , 103(3), 683.

Schinske, & Tanner, K. (2017). "Teaching more by grading less (or differently)." CBE Life Sciences Education , 13(2), 159–166.

Stanny, & Nilson, L. B. (2014). Specifications grading: Restoring rigor, motivating students, and saving faculty time . Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Streifer, & Palmer, M. (2020)."Alternative grading: Practices to support both equity and learning." University of Virginia: Center for Teaching Excellence.

Supiano, B. (2019). "Grades Can Hinder Learning: What Should Professors Use Instead?" Chronicle of Higher Education .

- Designing Your Course

- In the Classroom

- When/Why/How: Some General Principles of Responding to Student Work

- Consistency and Equity in Grading

- Assessing Class Participation

- Assessing Non-Traditional Assignments

- Decreasing Student Anxiety about Grades

- Getting Feedback

- Equitable & Inclusive Teaching

- Artificial Intelligence

- Advising and Mentoring

- Teaching and Your Career

- Teaching Remotely

- Tools and Platforms

- The Science of Learning

- Bok Publications

- Other Resources Around Campus

- U.S. Locations

- UMGC Europe

- Learn Online

- Find Answers

- 855-655-8682

- Current Students

Managing Assignments

Explore more of umgc.

- Writing Resources

Contact the Effective Writing Center

E-mail: writingcenter@umgc.edu

Learn how planning your assignments at the start ensures a smoother writing process.

Written assignments, whether short response essays or long research papers, often seem overwhelming at first, but carefully reading and evaluating assignment guidelines and requirements will help you understand your goals and plan your paper. This can result in a more confident, optimistic approach to the assignment, and a more relaxed writing experience.

Whenever you receive an assignment, it’s important to review the requirements several times. Reading them over as soon as you receive them will help you to plan how much time you’ll need, and get a sense of the scope, or focus, of the project. If you look over them again right before you start researching or writing, they will be fresh in your mind, and you’ll use your time more effectively, since you’ll have a better idea of what tasks you need to accomplish. Finally, always reread the assignment requirements after you’ve completed your rough draft but before you’ve started revising it. This will help you make sure that you’ve fulfilled all of the requirements before you hand the work in for a grade.

The first time you read the assignment guidelines, it’s helpful to keep these types of questions in mind: