Peer Recognized

Make a name in academia

Research Proposal Examples for Every Science Field

Looking for research funding can be a daunting task, especially when you are starting out. A great way to improve grant-writing skills is to get inspired by winning research proposal examples.

To assist you in writing a competitive proposal, I have curated a collection of real-life research proposal examples from various scientific disciplines. These examples will allow you to gain inspiration about the way research proposals are structured and written.

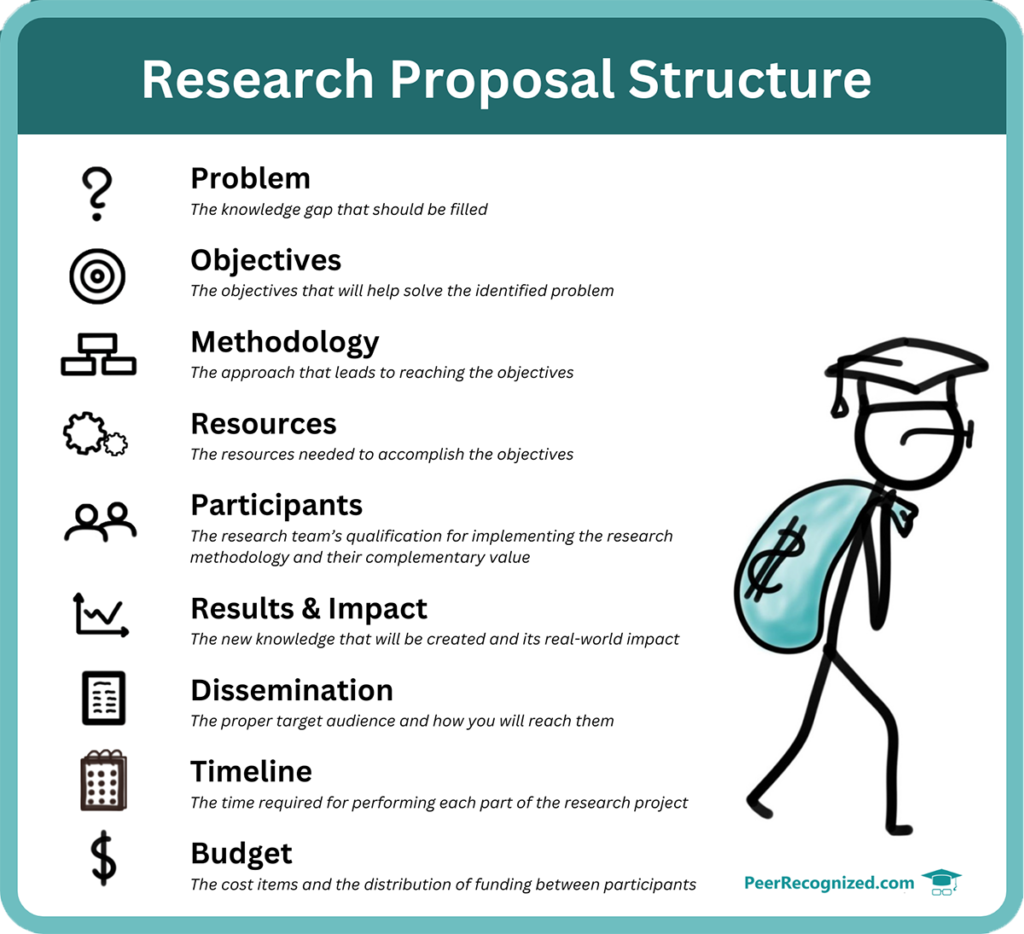

Structure of a Research Proposal

A research proposal serves as a road-map for a project, outlining the objectives, methodology, resources, and expected outcomes. The main goal of writing a research proposal is to convince funding agency of the value and feasibility of a research project. But a proposal also helps scientists themselves to clarify their planned approach.

While the exact structure may vary depending on the science field and institutional guidelines, a research proposal typically includes the following sections: Problem, Objectives, Methodology, Resources, Participants, Results&Impact, Dissemination, Timeline, and Budget. I will use this structure for the example research proposals in this article.

Here is a brief description of what each of the nine proposal sections should hold.

A concise and informative title that captures the essence of the research proposal. Sometimes an abstract is required that briefly summarizes the proposed project.

Clearly define the research problem or gap in knowledge that the study aims to address. Present relevant background information and cite existing literature to support the need for further investigation.

State the specific objectives and research questions that the study seeks to answer. These objectives should be clear, measurable, and aligned with the problem statement.

Methodology

Describe the research design, methodology, and techniques that will be employed to collect and analyze data. Justify your chosen approach and discuss its strengths and limitations.

Outline the resources required for the successful execution of the research project, such as equipment, facilities, software, and access to specific datasets or archives.

Participants

Describe the research team’s qualification for implementing the research methodology and their complementary value

Results and Impact

Describe the expected results, outcomes, and potential impact of the research. Discuss how the findings will contribute to the field and address the research gap identified earlier.

Dissemination

Explain how the research results will be disseminated to the academic community and wider audiences. This may include publications, conference presentations, workshops, data sharing or collaborations with industry partners.

Develop a realistic timeline that outlines the major milestones and activities of the research project. Consider potential challenges or delays and incorporate contingency plans.

Provide a detailed budget estimate, including anticipated expenses for research materials, equipment, participant compensation, travel, and other relevant costs. Justify the budget based on the project’s scope and requirements.

Consider that the above-mentioned proposal headings can be called differently depending on the funder’s requirements. However, you can be sure in one proposal’s section or another each of the mentioned sections will be included. Whenever provided, always use the proposal structure as required by the funding agency.

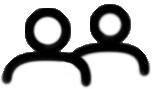

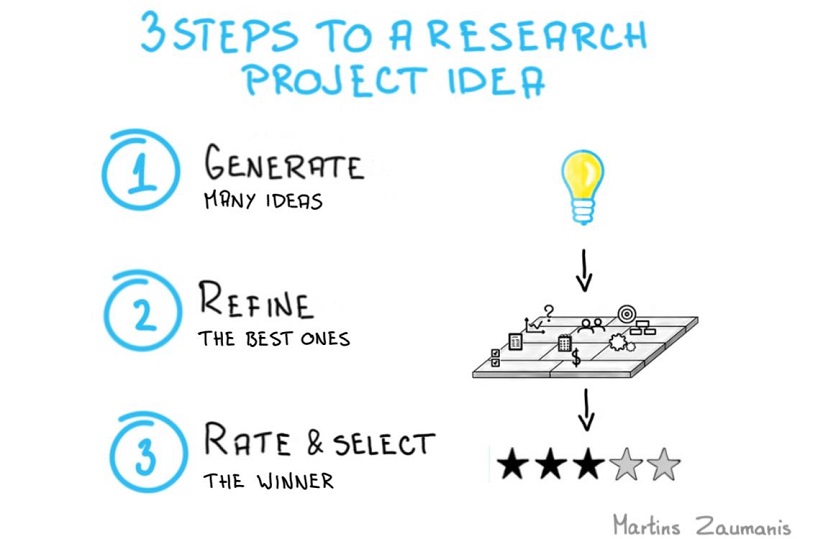

Research Proposal template download

This research proposal template includes the nine headings that we just discussed. For each heading, a key sentence skeleton is provided to help you to kick-start the proposal writing process.

Real-Life Research Proposal Examples

Proposals can vary from field to field so I will provide you with research proposal examples proposals in four main branches of science: social sciences, life sciences, physical sciences, and engineering and technology. For each science field, you will be able to download real-life winning research proposal examples.

To illustrate the principle of writing a scientific proposal while adhering to the nine sections I outlined earlier, for each discipline I will also provide you with a sample hypothetical research proposal. These examples are formulated using the key sentence structure that is included in the download template .

In case the research proposal examples I provide do not hold exactly what you are looking for, use the Open Grants database. It holds approved research proposals from various funding agencies in many countries. When looking for research proposals examples in the database, use the filer to search for specific keywords and organize the results to view proposals that have been funded.

Research Proposals Examples in Social Sciences

Here are real-life research proposal examples of funded projects in social sciences.

| (Cultural Anthropology) | |

Here is an outline of a hypothetical Social Sciences research proposal that is structured using the nine proposal sections we discussed earlier. This proposal example is produced using the key sentence skeleton that you will access in the proposal template .

The Influence of Social Media on Political Participation among Young Adults

Social media platforms have become prominent spaces for political discussions and information sharing. However, the impact of social media on political participation among young adults remains a topic of debate.

With the project, we aim to establish the relationship between social media usage and political engagement among young adults. To achieve this aim, we have three specific objectives:

- Examine the association between social media usage patterns and various forms of political participation, such as voting, attending political rallies, and engaging in political discussions.

- Investigate the role of social media in shaping political attitudes, opinions, and behaviors among young adults.

- Provide evidence-based recommendations for utilizing social media platforms to enhance youth political participation.

During the project, a mixed methods approach, combining quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews will be used to determine the impact of social media use on youth political engagement. In particular, surveys will collect data on social media usage, political participation, and attitudes. Interviews will provide in-depth insights into participants’ experiences and perceptions.

The project will use survey software, transcription tools, and statistical analysis software to statistically evaluate the gathered results. The project will also use project funding for participant compensation.

Principal investigator, Jane Goodrich will lead a multidisciplinary research team comprising social scientists, political scientists, and communication experts with expertise in political science and social media research.

The project will contribute to a better understanding of the influence of social media on political participation among young adults, including:

- inform about the association between social media usage and political participation among youth.

- determine the relationship between social media content and political preferences among youth.

- provide guidelines for enhancing youth engagement in democratic processes through social media use.

We will disseminate the research results within policymakers and NGOs through academic publications in peer-reviewed journals, presentations at relevant conferences, and policy briefs.

The project will start will be completed within two years and for the first two objectives a periodic report will be submitted in months 12 and 18.

The total eligible project costs are 58,800 USD, where 15% covers participant recruitment and compensation, 5% covers survey software licenses, 55% are dedicated for salaries, and 25% are intended for dissemination activities.

Research Proposal Examples in Life Sciences

Here are real-life research project examples in life sciences.

| | |

| | |

| (postdoctoral fellowship) | |

| (National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences) |

Here is a hypothetical research proposal example in Life Sciences. Just like the previous example, it consists of the nine discussed proposal sections and it is structured using the key sentence skeleton that you will access in the proposal template .

Investigating the Role of Gut Microbiota in Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome (GUT-MET)

Obesity and metabolic syndrome pose significant health challenges worldwide, leading to numerous chronic diseases and increasing healthcare costs. Despite extensive research, the precise mechanisms underlying these conditions remain incompletely understood. A critical knowledge gap exists regarding the role of gut microbiota in the development and progression of obesity and metabolic syndrome.

With the GUT-MET project, we aim to unravel the complex interactions between gut microbiota and obesity/metabolic syndrome. To achieve this aim, we have the following specific objectives:

- Investigate the composition and diversity of gut microbiota in individuals with obesity and metabolic syndrome.

- Determine the functional role of specific gut microbial species and their metabolites in the pathogenesis of obesity and metabolic syndrome.

During the project, we will employ the following key methodologies:

- Perform comprehensive metagenomic and metabolomic analyses to characterize the gut microbiota and associated metabolic pathways.

- Conduct animal studies to investigate the causal relationship between gut microbiota alterations and the development of obesity and metabolic syndrome.

The project will benefit from state-of-the-art laboratory facilities, including advanced sequencing and analytical equipment, as well as access to a well-established cohort of participants with obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Dr. Emma Johnson, a renowned expert in gut microbiota research and Professor of Molecular Biology at the University of PeerRecognized, will lead the project. Dr. Johnson has published extensively in high-impact journals and has received multiple research grants focused on the gut microbiota and metabolic health.

The project will deliver crucial insights into the role of gut microbiota in obesity and metabolic syndrome. Specifically, it will:

- Identify microbial signatures associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome for potential diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

- Uncover key microbial metabolites and pathways implicated in disease development, enabling the development of targeted interventions.

We will actively disseminate the project results within the scientific community, healthcare professionals, and relevant stakeholders through publications in peer-reviewed journals, presentations at international conferences, and engagement with patient advocacy groups.

The project will be executed over a period of 36 months. Key milestones include data collection and analysis, animal studies, manuscript preparation, and knowledge transfer activities.

The total eligible project costs are $1,500,000, with the budget allocated for 55% personnel, 25% laboratory supplies, 5% data analysis, and 15% knowledge dissemination activities as specified in the research call guidelines.

Research Proposals Examples in Natural Sciences

Here are real-life research proposal examples of funded projects in natural sciences.

| (FNU) | |

| (USGS) (Mendenhall Research Fellowship Program) | |

| (Earth Venture Mission – 3 NNH21ZDA002O) |

Here is a Natural Sciences research proposal example that is structured using the same nine sections. I created this proposal example using the key sentence skeleton that you will access in the proposal template .

Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Biodiversity Dynamics in Fragile Ecosystems (CLIM-BIODIV)

Climate change poses a significant threat to global biodiversity, particularly in fragile ecosystems such as tropical rainforests and coral reefs. Understanding the specific impacts of climate change on biodiversity dynamics within these ecosystems is crucial for effective conservation and management strategies. However, there is a knowledge gap regarding the precise mechanisms through which climate change influences species composition, population dynamics, and ecosystem functioning in these vulnerable habitats.

With the CLIM-BIODIV project, we aim to assess the impact of climate change on biodiversity dynamics in fragile ecosystems. To achieve this aim, we have the following specific objectives:

- Investigate how changes in temperature and precipitation patterns influence species distributions and community composition in tropical rainforests.

- Assess the effects of ocean warming and acidification on coral reef ecosystems, including changes in coral bleaching events, species diversity, and ecosystem resilience.

- Conduct field surveys and employ remote sensing techniques to assess changes in species distributions and community composition in tropical rainforests.

- Utilize experimental approaches and long-term monitoring data to evaluate the response of coral reefs to varying temperature and pH conditions.

The project will benefit from access to field sites in ecologically sensitive regions, advanced remote sensing technology, and collaboration with local conservation organizations to facilitate data collection and knowledge sharing.

Dr. Alexander Chen, an established researcher in climate change and biodiversity conservation, will lead the project. Dr. Chen is a Professor of Ecology at the University of Peer Recognized, with a track record of three Nature publications and successful grant applications exceeding 25 million dollars.

The project will provide valuable insights into the impacts of climate change on biodiversity dynamics in fragile ecosystems. It will:

- Enhance our understanding of how tropical rainforest communities respond to climate change, informing targeted conservation strategies.

- Contribute to the identification of vulnerable coral reef ecosystems and guide management practices for their protection and resilience.

We will disseminate the project results to the scientific community, conservation practitioners, and policymakers through publications in reputable journals, participation in international conferences, and engagement with local communities and relevant stakeholders.

The project will commence on March 1, 2024, and will be implemented over a period of 48 months. Key milestones include data collection and analysis, modeling exercises, stakeholder engagement, and knowledge transfer activities. These are summarized in the Gantt chart.

The total eligible project costs are $2,000,000, with budget allocation for research personnel, fieldwork expenses, laboratory analyses, modeling software, data management, and dissemination activities.

Research Proposal Examples in Engineering and Technology

Here are real-life research proposal examples of funded research projects in the field of science and technology.

| (USGS) (Mendenhall Postdoctoral Research Fellowship) | |

| (ROSES E.7 (Support for Open Source Tools, Frameworks, and Libraries)) |

Here is a hypothetical Engineering and Technology research proposal example that is structured using the same nine proposal sections we discussed earlier. I used the key sentence skeleton available in the proposal template to produce this example.

Developing Sustainable Materials for Energy-Efficient Buildings (SUST-BUILD)

The construction industry is a major contributor to global energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Addressing this issue requires the development of sustainable materials that promote energy efficiency in buildings. However, there is a need for innovative engineering solutions to overcome existing challenges related to the performance, cost-effectiveness, and scalability of such materials.

With the SUST-BUILD project, we aim to develop sustainable materials for energy-efficient buildings. Our specific objectives are as follows:

- Design and optimize novel insulating materials with enhanced thermal properties and reduced environmental impact.

- Develop advanced coatings and surface treatments to improve the energy efficiency and durability of building envelopes.

- Conduct extensive material characterization and simulation studies to guide the design and optimization of insulating materials.

- Utilize advanced coating techniques and perform full-scale testing to evaluate the performance and durability of building envelope treatments.

The project will benefit from access to state-of-the-art laboratory facilities, including material testing equipment, thermal analysis tools, and coating application setups. Collaboration with industry partners will facilitate the translation of research findings into practical applications.

Dr. Maria Rodriguez, an experienced researcher in sustainable materials and building technologies, will lead the project. Dr. Rodriguez holds a position as Associate Professor in the Department of Engineering at Peer Recognized University and has a strong publication record and expertise in the field.

The project will deliver tangible outcomes for energy-efficient buildings. It will:

- Develop sustainable insulating materials with superior thermal performance, contributing to reduced energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions in buildings.

- Introduce advanced coatings and surface treatments developed from sustainable materials that enhance the durability and energy efficiency of building envelopes, thereby improving long-term building performance.

We will disseminate project results to relevant stakeholders, including industry professionals, architects, and policymakers. This will be accomplished through publications in scientific journals, presentations at conferences and seminars, and engagement with industry associations.

The project will commence on September 1, 2024, and will be implemented over a period of 36 months. Key milestones include material development and optimization, performance testing, prototype fabrication, and knowledge transfer activities. The milestones are summarized in the Gantt chart.

The total eligible project costs are $1,800,000. The budget will cover personnel salaries (60%), materials and equipment (10%), laboratory testing (5%), prototyping (15%), data analysis (5%), and dissemination activities (5%) as specified in the research call guidelines.

Final Tips for Writing an Winning Research Proposal

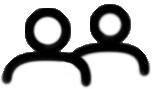

Come up with a good research idea.

Ideas are the currency of research world. I have prepared a 3 step approach that will help you to come up with a research idea that is worth turning into a proposal. You can download the Research Idea Generation Toolkit in this article.

Start with a strong research outline

Before even writing one sentence of the research proposal, I suggest you use the Research Project Canvas . It will help you to first come up with different research ideas and then choose the best one for writing a full research proposal.

Tailor to the requirements of the project funder

Treat the submission guide like a Monk treats the Bible and follow its strict requirements to the last detail. The funder might set requirements for the topic, your experience, employment conditions, host institution, the research team, funding amount, and so forth.

What you would like to do in the research is irrelevant unless it falls within the boundaries defined by the funder.

Make the reviewer’s job of finding flaws in your proposal difficult by ensuring that you have addressed each requirement clearly. If applicable, you can even use a table with requirements versus your approach. This will make your proposed approach absolutely evident for the reviewers.

Before submitting, assess your proposal using the criteria reviewers have to follow.

Conduct thorough background research

Before writing your research proposal, conduct comprehensive background research to familiarize yourself with existing literature, theories, and methodologies related to your topic. This will help you identify research gaps and formulate research questions that address these gaps. You will also establish competence in the eyes of reviewers by citing relevant literature.

Be concise and clear

Define research questions that are specific, measurable, and aligned with the problem statement.

If you think the reviewers might be from a field outside your own, avoid unnecessary jargon or complex language to help them to understand the proposal better.

Be specific in describing the research methodology. For example, include a brief description of the experimental methods you will rely upon, add a summary of the materials that you are going to use, attach samples of questionnaires that you will use, and include any other proof that demonstrates the thoroughness you have put into developing the research plan. Adding a flowchart is a great way to present the methodology.

Create a realistic timeline and budget

Develop a realistic project timeline that includes key milestones and activities, allowing for potential challenges or delays. Similarly, create a detailed budget estimate that covers all anticipated expenses, ensuring that it aligns with the scope and requirements of your research project. Be transparent and justify your budget allocations.

Demonstrate the significance and potential impact of the research

Clearly articulate the significance of your research and its potential impact on the field. Discuss how your findings can contribute to theory development, practical applications, policy-making, or other relevant areas.

Pay attention to formatting and style guidelines

Follow the formatting and style guidelines provided by your institution or funding agency. Pay attention to details such as font size, margins, referencing style, and section headings. Adhering to these guidelines demonstrates professionalism and attention to detail.

Take a break before editing

After preparing the first draft, set it aside for at least a week. Then thoroughly check it for logic and revise, revise, revise. Use the proposal submission guide to review your proposal against the requirements. Remember to use grammar checking tools to check for errors.

Finally, read the proposal out loud. This will help to ensure good readability.

Seek feedback

Share your proposal with mentors, colleagues, or members of your research community to receive constructive feedback and suggestions for improvement. Take these seriously since they provide a third party view of what is written (instead of what you think you have written).

Reviewing good examples is one of the best ways to learn a new skill. I hope that the research proposal examples in this article will be useful for you to get going with writing your own research proposal.

Have fun with the writing process and I hope your project gets approved!

Learning from research proposal examples alone is not enough

The research proposal examples I provided will help you to improve your grant writing skills. But learning from example proposals alone will take you a rather long time to master writing winning proposals.

To write a winning research proposal, you have to know how to add that elusive X-Factor that convinces the reviewers to move your proposal from the category “good” to the category “support”. This includes creating self-explanatory figures, creating a budget, collaborating with co-authors, and presenting a convincing story.

To write a research proposal that maximizes your chances of receiving research funding, read my book “ Write a Winning Research Proposal “.

This isn’t just a book. It’s a complete research proposal writing toolkit that includes a project ideation canvas, budget spreadsheet, project rating scorecard, virtual collaboration whiteboard, proposal pitch formula, graphics creation cheat sheet, review checklist and other valuable resources that will help you succeed.

Hey! My name is Martins Zaumanis and I am a materials scientist in Switzerland ( Google Scholar ). As the first person in my family with a PhD, I have first-hand experience of the challenges starting scientists face in academia. With this blog, I want to help young researchers succeed in academia. I call the blog “Peer Recognized”, because peer recognition is what lifts academic careers and pushes science forward.

Besides this blog, I have written the Peer Recognized book series and created the Peer Recognized Academy offering interactive online courses.

Related articles:

One comment

Hi Martins, I’ve recently discovered your content and it is great. I will be implementing much of it into my workflow, as well as using it to teach some graduate courses! I noticed that a materials science-focused proposal could be a very helpful addition.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

I want to join the Peer Recognized newsletter!

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Copyright © 2024 Martins Zaumanis

Contacts: [email protected]

Privacy Policy

- Research Process

- Manuscript Preparation

- Manuscript Review

- Publication Process

- Publication Recognition

Language Editing Services

- Translation Services

Writing a Scientific Research Project Proposal

- 5 minute read

- 114.4K views

Table of Contents

The importance of a well-written research proposal cannot be underestimated. Your research really is only as good as your proposal. A poorly written, or poorly conceived research proposal will doom even an otherwise worthy project. On the other hand, a well-written, high-quality proposal will increase your chances for success.

In this article, we’ll outline the basics of writing an effective scientific research proposal, including the differences between research proposals, grants and cover letters. We’ll also touch on common mistakes made when submitting research proposals, as well as a simple example or template that you can follow.

What is a scientific research proposal?

The main purpose of a scientific research proposal is to convince your audience that your project is worthwhile, and that you have the expertise and wherewithal to complete it. The elements of an effective research proposal mirror those of the research process itself, which we’ll outline below. Essentially, the research proposal should include enough information for the reader to determine if your proposed study is worth pursuing.

It is not an uncommon misunderstanding to think that a research proposal and a cover letter are the same things. However, they are different. The main difference between a research proposal vs cover letter content is distinct. Whereas the research proposal summarizes the proposal for future research, the cover letter connects you to the research, and how you are the right person to complete the proposed research.

There is also sometimes confusion around a research proposal vs grant application. Whereas a research proposal is a statement of intent, related to answering a research question, a grant application is a specific request for funding to complete the research proposed. Of course, there are elements of overlap between the two documents; it’s the purpose of the document that defines one or the other.

Scientific Research Proposal Format

Although there is no one way to write a scientific research proposal, there are specific guidelines. A lot depends on which journal you’re submitting your research proposal to, so you may need to follow their scientific research proposal template.

In general, however, there are fairly universal sections to every scientific research proposal. These include:

- Title: Make sure the title of your proposal is descriptive and concise. Make it catch and informative at the same time, avoiding dry phrases like, “An investigation…” Your title should pique the interest of the reader.

- Abstract: This is a brief (300-500 words) summary that includes the research question, your rationale for the study, and any applicable hypothesis. You should also include a brief description of your methodology, including procedures, samples, instruments, etc.

- Introduction: The opening paragraph of your research proposal is, perhaps, the most important. Here you want to introduce the research problem in a creative way, and demonstrate your understanding of the need for the research. You want the reader to think that your proposed research is current, important and relevant.

- Background: Include a brief history of the topic and link it to a contemporary context to show its relevance for today. Identify key researchers and institutions also looking at the problem

- Literature Review: This is the section that may take the longest amount of time to assemble. Here you want to synthesize prior research, and place your proposed research into the larger picture of what’s been studied in the past. You want to show your reader that your work is original, and adds to the current knowledge.

- Research Design and Methodology: This section should be very clearly and logically written and organized. You are letting your reader know that you know what you are going to do, and how. The reader should feel confident that you have the skills and knowledge needed to get the project done.

- Preliminary Implications: Here you’ll be outlining how you anticipate your research will extend current knowledge in your field. You might also want to discuss how your findings will impact future research needs.

- Conclusion: This section reinforces the significance and importance of your proposed research, and summarizes the entire proposal.

- References/Citations: Of course, you need to include a full and accurate list of any and all sources you used to write your research proposal.

Common Mistakes in Writing a Scientific Research Project Proposal

Remember, the best research proposal can be rejected if it’s not well written or is ill-conceived. The most common mistakes made include:

- Not providing the proper context for your research question or the problem

- Failing to reference landmark/key studies

- Losing focus of the research question or problem

- Not accurately presenting contributions by other researchers and institutions

- Incompletely developing a persuasive argument for the research that is being proposed

- Misplaced attention on minor points and/or not enough detail on major issues

- Sloppy, low-quality writing without effective logic and flow

- Incorrect or lapses in references and citations, and/or references not in proper format

- The proposal is too long – or too short

Scientific Research Proposal Example

There are countless examples that you can find for successful research proposals. In addition, you can also find examples of unsuccessful research proposals. Search for successful research proposals in your field, and even for your target journal, to get a good idea on what specifically your audience may be looking for.

While there’s no one example that will show you everything you need to know, looking at a few will give you a good idea of what you need to include in your own research proposal. Talk, also, to colleagues in your field, especially if you are a student or a new researcher. We can often learn from the mistakes of others. The more prepared and knowledgeable you are prior to writing your research proposal, the more likely you are to succeed.

One of the top reasons scientific research proposals are rejected is due to poor logic and flow. Check out our Language Editing Services to ensure a great proposal , that’s clear and concise, and properly referenced. Check our video for more information, and get started today.

Research Fraud: Falsification and Fabrication in Research Data

Research Team Structure

You may also like.

Descriptive Research Design and Its Myriad Uses

Five Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Biomedical Research Paper

Making Technical Writing in Environmental Engineering Accessible

To Err is Not Human: The Dangers of AI-assisted Academic Writing

When Data Speak, Listen: Importance of Data Collection and Analysis Methods

Choosing the Right Research Methodology: A Guide for Researchers

Why is data validation important in research?

Writing a good review article

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Postgraduate

Research degrees

- Examples of Research proposals

- Find a course

- Accessibility

Examples of research proposals

How to write your research proposal, with examples of good proposals.

Research proposals

Your research proposal is a key part of your application. It tells us about the question you want to answer through your research. It is a chance for you to show your knowledge of the subject area and tell us about the methods you want to use.

We use your research proposal to match you with a supervisor or team of supervisors.

In your proposal, please tell us if you have an interest in the work of a specific academic at York St John. You can get in touch with this academic to discuss your proposal. You can also speak to one of our Research Leads. There is a list of our Research Leads on the Apply page.

When you write your proposal you need to:

- Highlight how it is original or significant

- Explain how it will develop or challenge current knowledge of your subject

- Identify the importance of your research

- Show why you are the right person to do this research

- Research Proposal Example 1 (DOC, 49kB)

- Research Proposal Example 2 (DOC, 0.9MB)

- Research Proposal Example 3 (DOC, 55.5kB)

- Research Proposal Example 4 (DOC, 49.5kB)

Subject specific guidance

- Writing a Humanities PhD Proposal (PDF, 0.1MB)

- Writing a Creative Writing PhD Proposal (PDF, 0.1MB)

- About the University

- Our culture and values

- Academic schools

- Academic dates

- Press office

Our wider work

- Business support

- Work in the community

- Donate or support

Connect with us

York St John University

Lord Mayor’s Walk

01904 624 624

York St John London Campus

6th Floor Export Building

1 Clove Crescent

01904 876 944

- Policies and documents

- Module documents

- Programme specifications

- Quality gateway

- Admissions documents

- Access and Participation Plan

- Freedom of information

- Accessibility statement

- Modern slavery and human trafficking statement

© York St John University 2024

Colour Picker

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Dui id ornare arcu odio.

Felis bibendum ut tristique et egestas quis ipsum. Et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas. Faucibus pulvinar elementum integer enim neque volutpat ac. Hac habitasse platea dictumst vestibulum rhoncus.

Nec ullamcorper sit amet risus nullam eget felis eget. Eget felis eget nunc lobortis mattis aliquam faucibus purus.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Research Proposal SAMPLE: Assessing Food Insecurity (Food-Access Inequality) In Southeast San Diego Households

Although an estimated 85.5% of American households were considered food secure in 2010, about 48.8 million people weren’t (Andrews et al.). These households struggled with being able to access proper and enough food for the members of their home to have healthy growth and development. In the proposed study, I seek to assess the degree to which households in Southeast San Diego are food secure by measuring their level of access to healthy foods. Results will place households on a continuum developed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to have high, marginal, low, or very low food security compiled by the USDA Economic Research Service and listed in Appendix A. The access to food I will be focusing on is the proximity to sufficient grocery stores. I will be assessing the sufficiency of grocery stores in providing healthy food options, the availability of supermarkets, and geographical limitations to accessing these goods (such as transportation). By using research tools of surveys, interviews, online databases, and mapping, I will be able to assess a household’s access to healthy foods and determine the number of households and members in these households who have low access to healthy foods. The household interview in Appendix B will be analyzed to find trends of needs and suggestions for ways to improve the community. The survey of grocery stores in Appendix C will be analyzed independently to find possible trends of the availability and unavailability of certain food products. By also assessing the general racial/ethnic demographics of Southeast San Diego, I will be able to study how the degree of food access may disproportionately affect people of color. A second part to this research must be conducted to study the affordability of the healthy foods that these communities can access, with respect to race/ethnicity. A third part to the research must study the health consequences of the disparity of food access and affordability, with respect to race/ethnicity. The fourth part to this research project must be conducted to cater solutions to the problems of food access, affordability, and health disparities discovered in Southeast San Diego communities, with respect to race/ethnicity.

Related Papers

Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition

Kimberly Greder

University of Vermont

Hannah Stokes-Ramos

Food security research with resettled refugees in the United States and other Global North countries has found alarmingly high rates of food insecurity, up to 85% of surveyed households. This is well above the current US average of 12.7%. However, the most common survey tool used to measure food security status in the US, the US Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM), has not been sufficiently validated for resettled refugee populations, leading to the risk that the HFSSM may actually be underestimating the prevalence of food insecurity among resettled refugees in the US. Though research has attempted to establish validity of the HFSSM for resettled refugees through statistical associations with other risk factors for food insecurity, no efforts have been made to first explore and establish the content validity of the HFSSM for measuring food security among resettled refugees. Content validity is an essential component of construct validity. It first requires a qualitative theoretical foundation for demonstrating the relationships of the test contents to the underlying construct (ie food security) that the test intends to measure. Our research explores these theoretical relationships through a qualitative grounded study of food insecurity and food management experiences described by resettled refugees living in Vermont. We conducted 5 semi-structured focus groups in the summer and fall of 2015 with Bhutanese (2 groups), Somali Bantu (1 group), and Iraqi (2 groups) resettled refugees. During the focus groups, we inquired about food management practices under typical circumstances and under circumstances of limited household resources, as well as difficulties participants have faced in these processes. Additionally, I conducted 18 semi-structured interviews and 1 focus group in the same time frame with service providers who have worked with resettled refugees in capacities primarily related to food, health, and household resources. These interviews provided additional data about context, household food management practices among clients, and triangulating data for the focus groups. A Grounded Theory analysis of the focus group data yielded 5 major emergent themes: 1) Past food insecurity experiences of resettled refugee participants exerted significant influence on the subjective perception of current food insecurity. 2) Barriers other than just financial resources restricted participants’ food security, especially for recently resettled refugees. 3) Preferred foods differed significantly between generations within households. 4) Common elements of quality and quantity included in the definition and measurement of food security did not translate into the languages or experiences of food insecurity among participants. 5) Strategic and adaptive food management practices prevailed among participants, highlighting the temporality and ambiguity of food security concepts. These themes present potential problems of content validity for every HFSSM question. They also reveal the importance of food security concepts that are not covered by the HFSSM, including elements of nutritional adequacy of food, food safety, social acceptability of food and of means of acquiring food, short and long term certainty of food access, and food utilization. I conclude by discussing implications of our findings for service providers and local governments in Vermont who seek to better serve resettled refugee and other New American populations.

America Chavez

Christine A. Bevc

California Institute for Rural Studies

Gail Wadsworth , Sarah Cain

California Institute for Rural Studies assessed the food assistance resources in Yolo County and the level of food insecurity among selected Yolo County farm workers living in a rural food desert. The project was designed to address the USDA Community Food Projects Competitive Grant Program priorities by determining the level of farm worker food security and planning long-term solutions utilizing the existing network of food assistance resources in Yolo County. In 2000, the county estimated a population of 6,900 farm workers with 26,236 farm worker related persons. For this project, we focused our efforts on farm worker families living in rural communities in Yolo County and, using survey methodology, assessed their level of food security. We also identified the current extent of farm worker participation in food assistance programs. We created three food inventories: types of foods farm workers prefer, actual fruit and vegetable consumption, and types of food offered by the Yolo Food Bank. In this way we were able to determine where the gaps exist, and how to address them to better serve farm worker communities. Based on our results, we offer guidance for food programs in Yolo County regarding both optimal geographic locations for food distribution to reach farm workers and the types of foods that are appropriate for this population. This report outlines the level of food insecurity among rural farm workers in Yolo County and includes a directory of food resources for the county, map of distribution locations and suggestions for improving services specifically for farm workers.

Public Health Nutrition

Megan Carter , Lise Dubois

Journal of Urban Health

Darcy Freedman

Health Education & Behavior

Mark Dignan

Recently there has been an increase in the different types of strategies used in health education interventions, including an emphasis on broadening programs focused on individual behavior change to include larger units of practice. There has also been an increasing critique of the traditional physical science paradigm for evaluating the multiple dimensions inherent in many interventions. Additionally, there is a

BMC Public Health

Trias Mahmudiono , Dini Andrias

Background: Nutrition transition in developing countries were induced by rapid changes in food patterns and nutrient intake when populations adopt modern lifestyles during economic and social development, urbanization and acculturation. Consequently, these countries suffer from the double burden of malnutrition, consisting of unresolved undernutrition and the rise of overweight/obesity. The prevalence of the double burden of malnutrition tends to be highest for moderate levels (third quintile) of socioeconomic status. Evidence suggests that modifiable factors such as intra-household food distribution and dietary diversity are associated with the double burden of malnutrition, given household food security. This article describes the study protocol of a behaviorally based nutrition education intervention for overweight/obese mothers with stunted children (NEO-MOM) in reducing the double burden of malnutrition.

Scott McDoniel

The sociology of food theory details how access to food may influence social skills and behaviors. As an increasing number of juveniles are incarcerated in public and private detaining centers, the question arises of whether the problem may stem from food insecure homes. Determining whether a food insecure household is a factor in juvenile delinquency may aid in the rehabilitation process for this population. In this study, a quantitative analysis was conducted to determine if a difference existed between food insecurity and the number of felony crimes (N = 290) committed versus the number of misdemeanor crimes (N = 294) committed by juvenile delinquents (N = 584) in 7 U.S. States. A comparison was made between the juveniles' food security and the crime they committed. Food security was determined using the juveniles' height and weight to calculate their body mass index (kg/m 2 ). Statistical analysis included a z score to compare the crime types, and a 2-tailed t test to de...

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Carmen María Pérez

Michele Companion

Ron Strochlic , Christy Getz

Mister Soft

Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal

William A Mcintosh

Nutrition journal

Sonali Suratkar , Sangita Sharma , He-jung Song

Maria V Wathen

J. Gittelsohn

Shaheen Akter

Ellen Desjardins

Andrew A Zekeri

Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health

Jerusha Nelson-Peterman

Psychological Reports

Natale (Nat) Zappia

Elizabeth Baylor

Alejandro Espinoza

Carlijn Kamphuis

Public Philosophy Journal

Zachary Piso

International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity

Barbara Lohse

Emmanuel Montero

Annals of Epidemiology

Daniel Santisteban

Lisanne du M Plessis

British Journal of Nutrition

Michelle Grocke

Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research

Naomi Dachner

Guénola Capron , Jesús Carlos Morales Guzmán , Jill Wigle , Salomon Gonzalez Arellano

Editorial Department , Sindy De

Kristine Vigilla-Montecillo , Wilma Hurtada

Carlo Cafiero , Terri Ballard , Anne Kepple , Meghan Miller

Health promotion journal of Australia: official journal of Australian Association of Health Promotion Professionals

Orielle Solar

Journal of Extension

Rommel Tabula

Family Economics and Nutrition Review

W. Hillabrant , Nancy Pindus , Kenneth Finegold

International Journal for Equity in Health

Julie St John

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates

Published on October 12, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on November 21, 2023.

A research proposal describes what you will investigate, why it’s important, and how you will conduct your research.

The format of a research proposal varies between fields, but most proposals will contain at least these elements:

Introduction

Literature review.

- Research design

Reference list

While the sections may vary, the overall objective is always the same. A research proposal serves as a blueprint and guide for your research plan, helping you get organized and feel confident in the path forward you choose to take.

Table of contents

Research proposal purpose, research proposal examples, research design and methods, contribution to knowledge, research schedule, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research proposals.

Academics often have to write research proposals to get funding for their projects. As a student, you might have to write a research proposal as part of a grad school application , or prior to starting your thesis or dissertation .

In addition to helping you figure out what your research can look like, a proposal can also serve to demonstrate why your project is worth pursuing to a funder, educational institution, or supervisor.

| Show your reader why your project is interesting, original, and important. | |

| Demonstrate your comfort and familiarity with your field. Show that you understand the current state of research on your topic. | |

| Make a case for your . Demonstrate that you have carefully thought about the data, tools, and procedures necessary to conduct your research. | |

| Confirm that your project is feasible within the timeline of your program or funding deadline. |

Research proposal length

The length of a research proposal can vary quite a bit. A bachelor’s or master’s thesis proposal can be just a few pages, while proposals for PhD dissertations or research funding are usually much longer and more detailed. Your supervisor can help you determine the best length for your work.

One trick to get started is to think of your proposal’s structure as a shorter version of your thesis or dissertation , only without the results , conclusion and discussion sections.

Download our research proposal template

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing a research proposal can be quite challenging, but a good starting point could be to look at some examples. We’ve included a few for you below.

- Example research proposal #1: “A Conceptual Framework for Scheduling Constraint Management”

- Example research proposal #2: “Medical Students as Mediators of Change in Tobacco Use”

Like your dissertation or thesis, the proposal will usually have a title page that includes:

- The proposed title of your project

- Your supervisor’s name

- Your institution and department

The first part of your proposal is the initial pitch for your project. Make sure it succinctly explains what you want to do and why.

Your introduction should:

- Introduce your topic

- Give necessary background and context

- Outline your problem statement and research questions

To guide your introduction , include information about:

- Who could have an interest in the topic (e.g., scientists, policymakers)

- How much is already known about the topic

- What is missing from this current knowledge

- What new insights your research will contribute

- Why you believe this research is worth doing

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As you get started, it’s important to demonstrate that you’re familiar with the most important research on your topic. A strong literature review shows your reader that your project has a solid foundation in existing knowledge or theory. It also shows that you’re not simply repeating what other people have already done or said, but rather using existing research as a jumping-off point for your own.

In this section, share exactly how your project will contribute to ongoing conversations in the field by:

- Comparing and contrasting the main theories, methods, and debates

- Examining the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches

- Explaining how will you build on, challenge, or synthesize prior scholarship

Following the literature review, restate your main objectives . This brings the focus back to your own project. Next, your research design or methodology section will describe your overall approach, and the practical steps you will take to answer your research questions.

| ? or ? , , or research design? | |

| , )? ? | |

| , , , )? | |

| ? |

To finish your proposal on a strong note, explore the potential implications of your research for your field. Emphasize again what you aim to contribute and why it matters.

For example, your results might have implications for:

- Improving best practices

- Informing policymaking decisions

- Strengthening a theory or model

- Challenging popular or scientific beliefs

- Creating a basis for future research

Last but not least, your research proposal must include correct citations for every source you have used, compiled in a reference list . To create citations quickly and easily, you can use our free APA citation generator .

Some institutions or funders require a detailed timeline of the project, asking you to forecast what you will do at each stage and how long it may take. While not always required, be sure to check the requirements of your project.

Here’s an example schedule to help you get started. You can also download a template at the button below.

Download our research schedule template

| Research phase | Objectives | Deadline |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Background research and literature review | 20th January | |

| 2. Research design planning | and data analysis methods | 13th February |

| 3. Data collection and preparation | with selected participants and code interviews | 24th March |

| 4. Data analysis | of interview transcripts | 22nd April |

| 5. Writing | 17th June | |

| 6. Revision | final work | 28th July |

If you are applying for research funding, chances are you will have to include a detailed budget. This shows your estimates of how much each part of your project will cost.

Make sure to check what type of costs the funding body will agree to cover. For each item, include:

- Cost : exactly how much money do you need?

- Justification : why is this cost necessary to complete the research?

- Source : how did you calculate the amount?

To determine your budget, think about:

- Travel costs : do you need to go somewhere to collect your data? How will you get there, and how much time will you need? What will you do there (e.g., interviews, archival research)?

- Materials : do you need access to any tools or technologies?

- Help : do you need to hire any research assistants for the project? What will they do, and how much will you pay them?

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Once you’ve decided on your research objectives , you need to explain them in your paper, at the end of your problem statement .

Keep your research objectives clear and concise, and use appropriate verbs to accurately convey the work that you will carry out for each one.

I will compare …

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

A PhD, which is short for philosophiae doctor (doctor of philosophy in Latin), is the highest university degree that can be obtained. In a PhD, students spend 3–5 years writing a dissertation , which aims to make a significant, original contribution to current knowledge.

A PhD is intended to prepare students for a career as a researcher, whether that be in academia, the public sector, or the private sector.

A master’s is a 1- or 2-year graduate degree that can prepare you for a variety of careers.

All master’s involve graduate-level coursework. Some are research-intensive and intend to prepare students for further study in a PhD; these usually require their students to write a master’s thesis . Others focus on professional training for a specific career.

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

The best way to remember the difference between a research plan and a research proposal is that they have fundamentally different audiences. A research plan helps you, the researcher, organize your thoughts. On the other hand, a dissertation proposal or research proposal aims to convince others (e.g., a supervisor, a funding body, or a dissertation committee) that your research topic is relevant and worthy of being conducted.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, November 21). How to Write a Research Proposal | Examples & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-proposal/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is your plagiarism score.

Food Science and Technology Final Year Project Topics and Research Areas

View Project Topics

Food Science and Technology Final Year Project Topics and Research Areas encompass a wide range of subjects that examine various aspects of food production, processing, preservation, and safety. These projects examine the scientific understanding of food composition, structure, and properties, as well as the application of technology to enhance food quality, safety, and sustainability.

Introduction

In the final year of a Food Science and Technology program, students undertake projects that demonstrate their mastery of the discipline and their ability to apply theoretical knowledge to real-world challenges. These projects provide opportunities for students to conduct independent research, collaborate with industry partners, and contribute to advancements in the field of food science and technology.

Table of Content

- Novel Food Product Development

- Food Safety and Quality Assurance

- Food Packaging Technology

- Nutritional Analysis and Food Labeling

- Food Processing Optimization

- Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals

- Sustainable Food Production

1. Novel Food Product Development

This research area focuses on the creation of innovative food products that meet consumer demands for convenience, health, and sustainability. Projects may involve the formulation of new recipes, the inclusion of novel ingredients, or the development of alternative processing methods to enhance the nutritional profile, flavor, and texture of food products.

2. Food Safety and Quality Assurance

Ensuring the safety and quality of food products is paramount in the food industry. Research in this area may include the development of rapid detection methods for foodborne pathogens, the evaluation of food preservation techniques to prevent spoilage, and the implementation of quality management systems to comply with regulatory standards.

3. Food Packaging Technology

Packaging performs an important role in preserving the freshness and extending the shelf life of food products. Projects in this area may investigate the use of sustainable packaging materials, the development of active and intelligent packaging systems to monitor product integrity, and the optimization of packaging design for improved functionality and consumer convenience.

4. Nutritional Analysis and Food Labeling

Consumers are increasingly interested in the nutritional content of food products and rely on accurate labeling information to make informed choices. Research in this area may involve the analysis of macronutrients, micronutrients, and bioactive compounds in food samples, as well as the development of labeling strategies to communicate nutritional information effectively.

5. Food Processing Optimization

Efficient and sustainable food processing techniques are essential for maximizing yield, reducing waste, and minimizing energy consumption. Projects in this area may focus on process optimization using techniques such as thermal processing, high-pressure processing, and novel food drying methods to improve product quality and safety while maintaining cost-effectiveness.

6. Functional Foods and Nutraceuticals

Functional foods are those that provide health benefits beyond basic nutrition, often due to the presence of bioactive compounds with physiological effects. Research in this area may involve the identification of bioactive compounds in food sources, the evaluation of their health-promoting properties, and the development of functional food formulations targeting specific health conditions.

7. Sustainable Food Production

With growing concerns about the environmental impact of food production, research in this area aims to develop sustainable practices that minimize resource consumption, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and promote biodiversity. Projects may include the assessment of sustainable agricultural practices, the optimization of food processing methods to reduce waste, and the development of alternative protein sources to mitigate the environmental footprint of animal agriculture.

Food Science and Technology Final Year Project Topics and Research Areas encompass a different range of subjects that reflect the interdisciplinary nature of the field. By exploring these research areas, students can contribute to advancements in food science and technology while addressing current challenges facing the food industry, from ensuring food safety and quality to promoting sustainability and innovation

Sorry, there were no items that matched your criteria.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Sample Academic Proposals

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Select the Sample Academic Proposals PDF in the Media box above to download this file and read examples of proposals for conferences, journals, and book chapters.

DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln

Home > Food Science and Technology > Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research

Food Science and Technology Department

Department of food science and technology: dissertations, theses, and student research.

Utilization of Probiotics to Compete with Clostridioides difficile for Nutrient-Niches in a Variety of in vitro Contexts , April Elizabeth Johnson

The Effect of Fat Content on the Inactivation and Recovery of Listeria spp. in Ready-To-Eat Foods After High Pressure Processing , Yhuliana Kattalina Niño Fuerte

Microbial Transfer and Cross-Contamination in Milling Facilities and Pathogen Survival In Milled Products and Baking Mixes , Aryany Leticia Peña-Gomez

Development and Validation of Aronia melanocarpa Berry Recipes for Home Canning: Integrating Thermal Lethality Studies, Microbiological Safety, and Antioxidant Analysis , Juan Diego Villegas Posada

Cellulosome-forming Modules in Gut Microbiome and Virome , Jerry Akresi

Influence of Overcooking on Food Digestibility and in vitro Fermentation , Wensheng Ding

Development of an Intact Mass Spectrometry Method for the Detection and Differentiation of Major Bovine Milk Proteins , Emily F. Harley-Dowell

Optimizing Soil Nutrient Management to Improve Dry Edible Bean Yield and Protein Quality , Emily Jundt

Fusarium Species Structure in Nebraska Corn , Yuchu Ma

Evaluating Salmonella Cross Contamination In Raw Chicken Thighs In Simulated Post-Chill Tanks , Raziya Sadat

Evaluation of Human Microbiota-Associated (HMA) Porcine Models to Study the Human Gastrointestinal Microbiome , Nirosh D. Aluthge

Differential Effects of Protein Isolates on the Gut Microbiome under High and Low Fiber Conditions , Marissa Behounek

Evaluating the Microbial Quality and Use of Antimicrobials in Raw Pet Foods , Leslie Pearl Cancio

High Pressure Processing of Cashew Milk , Rachel Coggins

Occurrence of Hydroxyproline in Proteomes of Higher Plants , Olivia Huffman

Evaluation of Wheat-Specific Peptide Targets for Use in the Development of ELISA and Mass Spectrometry-Based Detection Methods , Jessica Humphrey

Safety Assessment of Novel Foods and Food Proteins , Niloofar Moghadam Maragheh

Identification of Gut Microbiome Composition Responsible for Gas Production , Erasme Mutuyemungu

Antimicrobial Efficacy of a Citric Acid/Hydrochloric Acid Blend, Peroxyacetic Acid, and Sulfuric Acid Against Salmonella on Inoculated Non-Conventional Raw Chicken Products , Emma Nakimera

Evaluating the Efficacy of Germination and Fermentation in Producing Biologically Active Peptides from Pulses , Ashley Newton

Development of a Targeted Mass Spectrometry Method for the Detection and Quantification of Peanut Protein in Incurred Food Matrices , Sara Schlange

Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Mucosal Attachment and Colonization by Clostridioides difficile , Ben Sidner

Comparative Assessment of Human Exposure to Antibiotic-Resistant Salmonella due to the Consumption of Various Food Products in the United States , Yifan Wu

Risk-based Evaluation of Treatments for Water Used at a Pre-harvest Stage to Mitigate Microbial Contamination of Fresh Raspberry in Chile , Constanza Avello Lefno

INVESTIGATING THE PREVALENCE AND CONTROL OF LISTERIA MONOCYTOGENES IN FOOD FACILITIES , Cyril Nsom Ayuk Etaka

Food Sensitivity in Individuals with Altered and Unaltered Digestive Tracts , Walker Carson

Risk Based Simulations of Sporeformers Population Throughout the Dairy Production and Processing Chain: Evaluating On-Farm Interventions in Nebraska Dairy Farms , Rhaisa A. Crespo Ramírez

Dietary Fiber Utilization in the Gut: The Role of Human Gut Microbes in the Degradation and Consumption of Xylose-Based Carbohydrates , Elizabeth Drey

Understanding the Roles of Nutrient-Niche Dynamics In Clostridioides difficile Colonization in Human Microbiome Colonized Minibioreactors , Xiaoyun Huang

Effect of Radiofrequency Assisted Thermal Processing on the Structural, Functional and Biological Properties of Egg White Powder , Alisha Kar

Synthesizing Inactivation Efficacy of Treatments against Bacillus cereus through Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis and Evaluating Inactivation Efficacy of Commercial Cleaning Products against B. cereus Biofilms and Spores Using Standardized Methods , Minho Kim

Gut Community Response to Wheat Bran and Pinto Bean , ShuEn Leow

The Differences of Prokaryotic Pan-genome Analysis on Complete Genomes and Simulated Metagenome-Assembled Genomes , Tang Li

Studies on milling and baking quality and in-vitro protein digestibility of historical and modern wheats , Sujun Liu

The Application of Mathematical Optimization and Flavor-Detection Technologies for Modeling Aroma of Hops , Yutong Liu

Pre-Milling Interventions for Improving the Microbiological Quality of Wheat , Shpresa Musa

NOVEL SOURCES OF FOOD ALLERGENS , Lee Palmer

Process Interventions for Improving the Microbiological Safety of Low Moisture Food Ingredients , Tushar Verma

Microbial Challenge Studies of Radio Frequency Heating for Dairy Powders and Gaseous Technologies for Spices , Xinyao Wei

The Molecular Basis for Natural Competence in Acinetobacter , Yafan Yu

Using Bioinformatics Tools to Evaluate Potential Risks of Food Allergy and to Predict Microbiome Functionality , Mohamed Abdelmoteleb

CONSUMER ATTITUDES, KNOWLEDGE, AND BEHAVIOR: UNDERSTANDING GLUTEN AVOIDANCE AND POINT-OF-DECISION PROMPTS TO INCREASE FIBER CONSUMPTION , Kristina Arslain

EVALUATING THE EFFECT OF NON-THERMAL PROCESSING AND ENZYMATIC HYDROLYSIS IN MODULATING THE ANTIOXIDANT ACTIVITY OF NEBRASKAN GREAT NORTHERN BEANS , Madhurima Bandyopadhyay

DETECTION OF FOOD PROTEINS IN HUMAN SERUM USING MASS SPECTROMETRY METHODS , Abigail S. Burrows

ASSESSING THE QUANTIFICATION OF SOY PROTEIN IN INCURRED MATRICES USING TARGETED LC-MS/MS , Jenna Krager

RESEARCH TOOLS AND THEIR USES FOR DETERMINING THE THERMAL INACTIVATION KINETICS OF SALMONELLA IN LOW-MOISTURE FOODS , Soon Kiat Lau

Investigating Microbial and Host Factors that Modulate Severity of Clostridioides difficile Associated Disease , Armando Lerma

Assessment of Grain Safety in Developing Nations , Jose R. Mendoza

EVALUATION OF LISTERIA INNOCUA TRANSFER FROM PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT (PPE) TO THE PLANT ENVIRONMENT AND EFFECTIVE SANITATION PROCEDURES TO CONTROL IT IN DAIRY PROCESSING FACILITIES , Karen Nieto

Development of a Sandwich ELISA Targeting Cashew Ana o 2 and Ana o 3 , Morganne Schmidt

Identification, aggressiveness and mycotoxin production of Fusarium graminearum and F. boothii isolates causing Fusarium head blight of wheat in Nebraska , Esteban Valverde-Bogantes

HIGH PRESSURE THAWING OF RAW POULTRY MEATS , Ali Alqaraghuli

Characterization and Evaluation of the Probiotic Properties of the Sporeforming Bacteria, Bacillus coagulans Unique IS-2 , Amy Garrison

Formation of Low Density and Free-Flowing Hollow Microparticles from Non-Hydrogenated Oils and Preparation of Pastries with Shortening Fat Composed of the Microparticles , Joshua Gudeman

Evaluating the Efficacy of Whole Cooked Enriched Egg in Modulating Health-Beneficial Biological Activities , Emerson Nolasco

Effect of Processing on Microbiota Accessible Carbohydrates in Whole Grains , Caroline Smith

ENCAPSULATION OF ASTAXANTHIN-ENRICHED CAMELINA SEED OIL OBTAINED BY ETHANOL-MODIFIED SUPERCRITICAL CARBON DIOXIDE EXTRACTION , Liyang Xie

Energy and Water Assessment and Plausibility of Reuse of Spent Caustic Solution in a Midwest Fluid Milk Processing Plant , Carly Rain Adams

Effect of Gallic and Ferulic Acids on Oxidative Phosphorylation on Candida albicans (A72 and SC5314) During the Yeast-to-Hyphae Transition , REHAB ALDAHASH

ABILITY OF PHENOLICS IN ISOLATION, COMPONENTS PRESENT IN SUPINA TURF GRASS TO REMEDIATE CANDIDA ALBICANS (A72 and SC5314) ADHESION AND BIOFILM FORMATION , Fatima Alessa

EFFECT OF PROCESSING ON IN-VITRO PROTEIN DIGESTIBILITY AND OTHER NUTRITIONAL ASPECTS OF NEBRASKA CROPS , Paridhi Gulati

Studies On The Physicochemical Characterization Of Flours And Protein Hydrolysates From Common Beans , Hollman Andres Motta Romero

Implementation of ISO/IEC Practices in Small and Academic Laboratories , Eric Layne Oliver

Enzymatic Activities and Compostional Properties of Whole Wheat Flour , Rachana Poudel

A Risk-Based Approach to Evaluate the Impact of Interventions at Reducing the Risk of Foodborne Illness Associated with Wheat-Based Products , Luis Sabillon

Thermal Inactivation Kinetics of Salmonella enterica and Enterococcus faecium in Ground Black Pepper , Sabrina Vasquez

Energy-Water Reduction and Wastewater Reclamation in a Fluid Milk Processing Facility , CarlyRain Adams, Yulie E. Meneses, Bing Wang, and Curtis Weller

Modeling the Survival of Salmonella in Soy Sauce-Based Products Stored at Two Different Temperatures , Ana Cristina Arciniega Castillo

WHOLE GRAIN PROCESSING AND EFFECTS ON CARBOHYDRATE DIGESTION AND FERMENTATION , Sandrayee Brahma

Promoting Gastrointestinal Health and Decreasing Inflammation with Whole Grains in Comparison to Fruit and Vegetables through Clinical Interventions and in vitro Tests , Julianne Kopf

Development of a Rapid Detection and Quantification Method for Yeasts and Molds in Dairy Products , Brandon Nguyen

Increasing Cis-lycopene Content of the Oleoresin from Tomato Processing Byproducts Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide and Assessment of Its Bioaccessibility , Lisbeth Vallecilla Yepez

Species and Trichothecene Genotypes of Fusarium Head Blight Pathogens in Nebraska, USA in 2015-2016 , Esteban Valverde-Bogantes

Validation of Extrusion Processing for the Safety of Low-Moisture Foods , Tushar Verma

Radiofrequency processing for inactivation of Salmonella spp. and Enterococcus faecium NRRL B-2354 in whole black peppercorn and ground black pepper , Xinyao Wei

CHARACTERIZATION OF EXTRACTION METHODS TO RECOVER PHENOLIC-RICH EXTRACTS FROM PINTO BEANS (BAJA) THAT INHIBIT ALPHA-AMYLASE AND ALPHA-GLUCOSIDASE USING RESPONSE SURFACE APPROACHES , Mohammed Alrugaibah

Matrix Effects on the Detection of Milk and Peanut Residues by Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA) , Abigail S. Burrows

Evaluation of Qualitative Food Allergen Detection Methods and Cleaning Validation Approaches , Rachel C. Courtney

Studies of Debaryomyces hansenii killer toxin and its effect on pathogenic bloodstream Candida isolates , Rhaisa A. Crespo Ramírez

Development of a Sandwich Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) for Detection of Macadamia Nut Residues in Processed Food Products , Charlene Gan

FROM MILPAS TO THE MARKET: A STUDY ON THE USE OF METAL SILOS FOR SAFER AND BETTER STORAGE OF GUATEMALAN MAIZE , José Rodrigo Mendoza

Feasibility, safety, economic and environmental implications of whey-recovered water for cleaning-in place systems: A case study on water conservation for the dairy industry , Yulie E. Meneses-González

Studies on asparagine in Nebraska wheat and other grains , Sviatoslav Navrotskyi

Risk Assessment and Research Synthesis methodologies in food safety: two effective tools to provide scientific evidence into the Decision Making Process. , Juan E. Ortuzar

Edible Insects as a Source of Food Allergens , Lee Palmer

IMPROVING THE UTILIZATION OF DRY EDIBLE BEANS IN A READY-TO-EAT SNACK PRODUCT BY EXTRUSION COOKING , Franklin Sumargo

Formation of Bioactive-Carrier Hollow Solid Lipid Micro- and Nanoparticles , Junsi Yang

The Influence of the Bovine Fecal Microbiota on the Shedding of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli (STEC) by Beef Cattle , Nirosh D. Aluthge

Preference Mapping of Whole Grain and High Fiber Products: Whole Wheat Bread and Extruded Rice and Bean Snack , Ashley J. Bernstein

Comparative Study Of The D-values of Salmonella spp. and Enterococcus faecium in Wheat Flour , Didier Dodier

Simulation and Validation of Radio Frequency Heating of Shell Eggs , Soon Kiat Lau

Viability of Lactobacillus acidophilus DDS 1-10 Encapsulated with an Alginate-Starch Matrix , Liya Mo

Inactivation of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Shiga Toxin Producing E. coli (STEC) Throughout Beef Summer Sausage Production and the use of High Pressure Processing as an Alternative Intervention to Thermal Processing , Eric L. Oliver

A Finite Element Method Based Microwave Heat Transfer Modeling of Frozen Multi-Component Foods , Krishnamoorthy Pitchai