- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Afghanistan War

By: History.com Editors

Published: August 20, 2021

The United States launched the war in Afghanistan following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. The conflict lasted two decades and spanned four U.S. presidencies, becoming the longest war in American history.

By August 2021, the war began to come to a close with the Taliban regaining power two weeks before the United States was set to withdraw all troops from the region. Overall, the conflict resulted in tens of thousands of deaths and a $2 trillion price tag . Here's a look at key events from the conflict.

War on Terror Begins

Investigators determined the 9/11 attacks—in which terrorists hijacked four commercial airplanes, crashing two into the World Trade Center towers in New York City , one at the Pentagon near Washington, D.C., and one in a Pennsylvania field —were orchestrated by terrorists working from Afghanistan, which was under the control of the Taliban, an extremist Islamic movement. Leading the plot that killed more than 2,700 people was Osama bin Laden , leader of the Islamic militant group al Qaeda . It was believed the Taliban, which seized power in the country in 1996 following an occupation by the Soviet Union , was harboring bin Laden, a Saudi, in Afghanistan.

In an address on September 20, 2001, President George W. Bush demanded the Taliban deliver bin Laden and other al Qaeda leaders to the United States, or "share in their fate." They refused.

On October 7, 2001, U.S. and British forces launched Operation Enduring Freedom , an airstrike campaign against al Qaeda and Taliban targets including Kandahar, Kabul and Jalalabad that lasted five days. Ground forces followed, and with the help of Northern Alliance forces, the United States quickly overtook Taliban strongholds, including the capital city of Kabul, by mid-November. On December 6, Kandahar fell, signaling the official end of Taliban rule in Afghanistan and causing al Qaeda, and bin Laden, to flee.

Shift to Reconstruction

During a speech on April 17, 2002, Bush called for a Marshall Plan to aid in Afghanistan’s reconstruction, with Congress appropriating more than $38 billion for humanitarian efforts and to train Afghan security forces. In June, Hamid Karzai, head of the Popalzai Durrani tribe, was chosen to lead the transitional government.

While approximately 8,000 American troops remained in Afghanistan as part of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) overseen by NATO, the U.S. military focus turned to Iraq in 2003, the same year U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld declared "major combat" operations had come to an end in Afghanistan.

A new constitution was soon enacted and Afghanistan held its first democratic elections since the onset of the war on October 9, 2004, with Karzai, who went on to serve two five-year terms, winning the vote for president. The ISAF’s focus shifted to peacekeeping and reconstruction, but with the United States fighting a war in Iraq, the Taliban regrouped and attacks escalated.

Troop Surge Under Obama

In a written statement released February 17, 2009, newly elected President Barack Obama pledged to send an extra 17,000 U.S. troops to Afghanistan by summer to join 36,000 American and 32,000 NATO forces already deployed there. "This increase is necessary to stabilize a deteriorating situation in Afghanistan, which has not received the strategic attention, direction and resources it urgently requires," he stated . American troops reached a peak of approximately 110,000 soldiers in Afghanistan in 2011.

In November 2010, NATO countries agreed to a transition of power to local Afghan security forces by the end of 2014, and, on May 2, 2011, following 10-year manhunt, U.S. Navy SEALs located and killed bin Laden in Pakistan.

Following bin Laden's death, a decade into the war and facing calls from both lawmakers and the public to end the war, Obama released a plan to withdraw 33,000 U.S. troops by summer 2012, and all troops by 2014. NATO transitioned control to Afghan forces in June 2013, and Obama announced a new timeline for troop withdrawal in 2014, which included 9,800 U.S. soldiers remaining in Afghanistan to continue training local forces.

Trump: 'We Will Fight to Win'

In 2015, the Taliban continued to increase its attacks, bombing the parliament building and airport in Kabul and carrying out multiple suicide bombings.

In his first few months of office, President Donald Trump authorized the Pentagon to make combat decisions in Afghanistan, and, on April 13, 2017, the United States dropped its most powerful non-nuclear bomb, called the " mother of all bombs ," on a remote ISIS cave complex.

In August 2017, Trump delivered a speech to American troops vowing " we will fight to win " in Afghanistan. "America's enemies must never know our plans, or believe they can wait us out," he said. "I will not say when we are going to attack, but attack we will."

The Taliban continued to escalate its terrorist attacks, and the United States entered peace talks with the group in February 2019. A deal was reached that included the U.S. and NATO allies pledging a total withdrawal within 14 months if the Taliban vowed to not harbor terrorist groups. But by September, Trump called off the talks after a Taliban attack that left a U.S. soldier and 11 others dead. “If they cannot agree to a ceasefire during these very important peace talks, and would even kill 12 innocent people, then they probably don’t have the power to negotiate a meaningful agreement anyway,” Trump tweeted .

Still, the United States and Taliban signed a peace agreement on February 29, 2020, although Taliban attacks against Afghan forces continued, as did American airstrikes. In September 2020, members of the Afghan government met with the Taliban to resume peace talks and in November Trump announced that he planned to reduce U.S. troops in Afghanistan to 2,500 by January 15, 2021.

Withdrawal of US Troops

The fourth president in power during the war, President Joe Biden , in April 2021, set the symbolic deadline of September 11, 2021, the 20th anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, as the date of full U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, with the final withdrawal effort beginning in May.

Facing little resistance, in just 10 days, from August 6-15, 2021, the Taliban swiftly overtook provincial capitals, Kandahar, Mazar-e-Sharif and, finally, Kabul. As the Afghan government collapsed, President Ashraf Ghani fled to the UAE , the U.S. embassy was evacuated and thousands of citizens rushed to the airport in Kabul to leave the country.

By August 14, Biden had temporarily deployed about 6,000 U.S. troops to assist in evacuation efforts. Facing scrutiny for the Taliban's swift return to power, Biden stated , “I was the fourth president to preside over an American troop presence in Afghanistan—two Republicans, two Democrats. I would not, and will not, pass this war on to a fifth.”

During the war in Afghanistan, more than 3,500 allied soldiers were killed, including 2,448 American service members, with 20,000-plus Americans injured. Brown University research shows approximately 69,000 Afghan security forces were killed, along with 51,000 civilians and 51,000 militants. According to the United Nations, some 5 million Afghanis have been displaced by the war since 2012, making Afghanistan the world's third-largest displaced population .

The U.S. War in Afghanistan , Council on Foreign Relations

Costs of the Afghanistan war, in lives and dollars , Associated Press

Who Are the Taliban, and What Do They Want? , The New York Times

Operation Enduring Freedom Fast Facts , CNN

Afghanistan: Why is there a war? , BBC News

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Afghanistan 20/20: The 20-Year War in 20 Documents

Primary sources contradict Pentagon optimism over decades

Pakistan sanctuaries, Afghan corruption enabled Taliban resurgence

Bush nation-building, Obama surge, Trump deal all failed

Washington, D.C., August 19, 2021 – The U.S. government under four presidents misled the American people for nearly two decades about progress in Afghanistan, while hiding the inconvenient facts about ongoing failures inside confidential channels, according to declassified documents published today by the National Security Archive. The documents include highest-level “snowflake” memos written by then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld during the George W. Bush administration, critical cables written by U.S. ambassadors back to Washington under both Bush and Barack Obama, the deeply flawed Pentagon strategy document behind Obama’s “surge” in 2009, and multiple “lessons learned” findings by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) – lessons that were never learned.

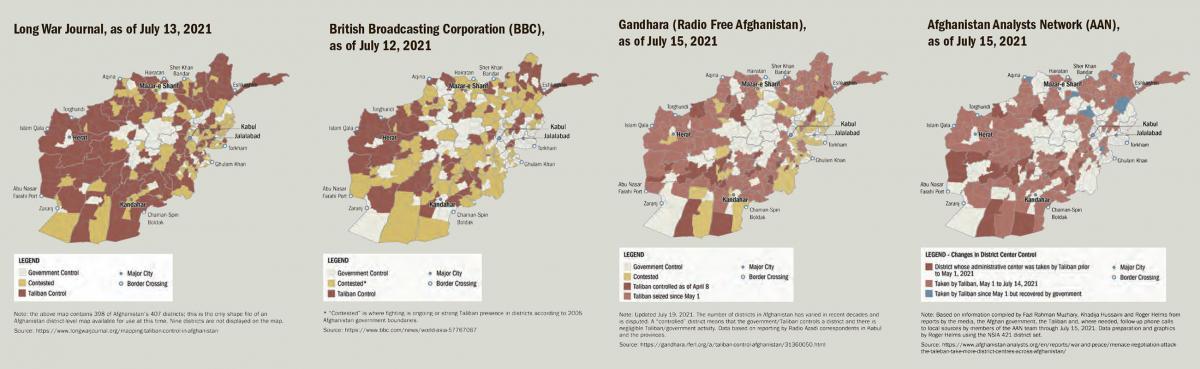

Estimates of Taliban controlled districts in Afghanistan as of mid-July 2021 ranged as high as more than half, according to the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, Quarterly Report, July 31, 2021, p. 55. The number had increased from 73 in April to 221 in July, a harbinger of the August takeover in Kabul.

The recent SIGAR report to Congress, from July 31, 2021, just as multiple provincial centers were falling to the Taliban, quotes repeated assurances from top U.S. generals (David Petraeus in 2011, John Campbell in 2015, John Nicholson in 2017, and Pentagon press secretary John Kirby in 2021) about the “increasingly capable” Afghan security forces. The SIGAR ends that section with the warning: “More than $88 billion has been appropriated to support Afghanistan’s security sector. The question of whether that money was well spent will ultimately be answered by the outcome of the fighting on the ground, perhaps the purest M&E [monitoring and evaluation] exercise.” Results are now in with the total collapse of the Afghan government and a looming humanitarian crisis. The documents detail ongoing problems that bedeviled the American war in Afghanistan from the beginning: lack of “visibility into who the bad guys are;” Pakistan’s double game of taking U.S. aid while providing a sanctuary to the Taliban; “mission creep” as a counterterror effort against al-Qaeda morphed into a nation-building war against the Taliban; Washington’s attention deficit disorder as the Bush administration pivoted to invading and occupying Iraq; endemic corruption driven in large part by American billions and secret intelligence payments to warlords; fake statistics and gassy metrics not only by the military but also the State Department, US AID, and their many contractors; the mismatch between Afghan realities and American designs for a new centralized government and modernized army; and more.

Read the Documents

Digital National Security Archive, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit

This is the foundational document for the first phase of U.S. strategy in Afghanistan, approved by the National Security Council on October 16, 2001 (just five weeks after the 9/11 attacks). This copy carries Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld’s personal handwritten edits, with an October 30 cover note to his top policy aide Douglas Feith about crafting a new updated version, emphasizing that "The U.S. should not commit to any post-Taliban military involvement since the U.S. will be heavily engaged in the anti-terrorism effort worldwide." The follow-on peacekeeping force in Afghanistan “could be UN-based or an ad hoc collection of volunteer states … but not the U.S.” Rumsfeld adds the word “military” as in “not the U.S. military.” The strategy emphasizes the destruction of al-Qaeda and the Taliban, and is careful not to commit the U.S. to extensive rebuilding activities in post-Taliban Afghanistan. "The USG [U.S. Government] should not agonize over post-Taliban arrangements to the point that it delays success over Al Qaida and the Taliban.” Operationally, the U.S. will "use any and all Afghan tribes and factions to eliminate Al-Qaida and Taliban personnel," while inserting "CIA teams and special forces in country operational detachments (A teams) by any means, both in the North and the South." Diplomacy is important "bilaterally, particularly with Pakistan, but also with Iran and Russia," however "engaging UN diplomacy… beyond intent and general outline could interfere with U.S. military operations and inhibit coalition freedom of action." U.S. bombing began in Afghanistan on October 7, 2001, the special forces teams arrived October 19, and in the second week of November, in a stunning cascade of Taliban surrenders, all major cities except Kandahar fell to the U.S.-backed Northern Alliance. Taliban leaders took refuge mostly in Pakistan but also around Kandahar, Taliban soldiers melted into the population, and the sequence provided almost a mirror image of the rapid August 2021 implosion of the Afghan government and security forces.

Exhilarated by swift victory over the Taliban in late 2001, the Bush administration quickly switched its attention to Iraq, but by March 2002 Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld was worried again about Afghanistan, writing a snowflake to top aides about setting up a weekly meeting because the situation was “drifting.” Later the same day, Rumsfeld would do a long interview with MSNBC, never mentioning his worries about drift, but rather arguing there was no point in negotiating with Taliban remnants – “the only thing you can do is to bomb them and try to kill them. And that’s what we did, and it worked. They’re gone. And the Afghan people are a lot better off.”

On April 17, 2002, President George W. Bush announced new objectives for Afghanistan in a speech at the Virginia Military Institute, including a stable government, a new army, and a new education system for boys and girls. In effect, Bush’s speech revoked the previous Rumsfeld insistence about not committing “to any post-Taliban military involvement.” That same day when the stated U.S. goals moved to nation building, Rumsfeld’s concerns about no clear exit strategy from Afghanistan crystallized in a short snowflake addressed to his top policy aide Douglas Feith and copied to his deputy Paul Wolfowitz and to the chair and vice-chair of the Joint Chiefs. “I know I’m a bit impatient,” he writes, but “We are never going to get the U.S. military out of Afghanistan unless we take care to see that there is something going on that will provide the stability that will be necessary for us to leave.” “Help!”

This Rumsfeld memo to his policy aide, Douglas Feith, on June 25, 2002 captures how naïve top American officials were about Pakistani motivations, and how throwing money at any problem came to be the core U.S. modus operandi around Afghanistan. Rumsfeld asks, “If we are going to get the Paks to really fight the war on terror where it is, which is in their country, don’t you think we ought to get a chunk of money, so that we can ease Musharraf’s transition from where he is to where we need him.” Rumsfeld does not see how Pakistan and its intelligence service were playing both sides in Afghanistan, and the net for Pakistani leader Musharraf was some $10 billion in U.S. aid over the following six years.

Obtained through FOIA by the National Security Archive

This 14-page email written between August 11 and August 15, 2002, by a Green Beret member of a commando team hunting “high-value” targets circulated at the highest levels of the Pentagon, not least because of its humor and its candor about actual conditions in Afghanistan, and the author’s previous position as a deputy assistant secretary of defense before his Reserve unit mobilized. Roger Pardo-Maurer opened with his “Greetings from scenic Kandahar” which he went on to describe as “Formerly known as ‘Home of the Taliban.’ Now known as ‘Miserable Rat-Fuck Shithole.” “Kandahar is like sitting in a sauna and having a bag of cement shaken over your head.” To those who call it dry heat, Pardo-Maurer, a member of Yale’s class of 1984, rejoins, “you don’t stay dry for long when you are the Lobster Thermidor inside a carapace of about 50 lbs. of Kevlar and ceramic plate armor, with a sweltering chamber pot on your head.” “If there is a landscape less welcoming to humans anywhere on earth, apart from the Sahara, the Poles, and the cauldrons of Kilauea [Hawaii], I cannot imagine it, and I certainly don’t intend to go there.”

Alluding to the continuing role of Pakistan as a Taliban sanctuary, Pardo-Maurer warned, “The shooting match is still very much on. Along the border provinces, you can’t kick a stone over without Bad Guys swarming out like ants and snakes and scorpions.” He recommends staying with a Special Forces strategy “fighting along the Afghans, rather than against them” – “the number one military mistake we could make here is to ‘go conventional’ in this war.” As for “the number one political mistake,” that would be “to actually believe that this place is a country, and that there is such a thing as an Afghan. It is not, and there is not.” “Afghanistan is the place where the world saw fit to stash all the tribes it could not handle elsewhere.” Rumsfeld specifically asked for a copy of the Pardo-Maurer document in a snowflake on September 13, 2002, included here as the cover memo.

In the ongoing debates inside the U.S. government about nation-building in Afghanistan, Rumsfeld insisted that more troops were not the answer, and blamed agencies like State and U.S. AID for the lack of progress. They in turn blamed Rumsfeld for not cooperating with their reconstruction plans and not providing security. He wrote President Bush on August 20, 2002, arguing, “the critical problem in Afghanistan is not really a security problem. Rather, the problem that needs to be addressed is the slow progress that is being made on the civil side.” More troops would backfire, “we could run the risk of ending up being as hated as the Soviets were,” and “without successful reconstruction, no amount of added security forces would be enough.” Yet, because of the “perception that does exist” about security problems, Rumsfeld has assigned a brigadier general (and future U.S. ambassador), Karl Eikenberry, to serve as security coordinator on the staff of the Embassy.

By the fall of 2002, the White House focus centered on the buildup to invading Iraq, to the point that President Bush didn’t even know who his latest commander was in Kabul. This Rumsfeld snowflake, likely to a secretary whose name is redacted on privacy grounds (b6), recounts seeing Bush in the Oval Office on October 21, 2002, asking if he wanted to meet with General Franks (head of Central Command) and General McNeill, and noticing that Bush was quite puzzled. “He said, ‘Who is General McNeill?’ I said he is the general in charge of Afghanistan. He said, ‘Well, I don’t need to meet with him.”

This September 2003 memo from the Secretary of Defense to his top intelligence aide, Steve Cambone, laments that nearly two years into the Afghan war, they still don’t know the enemy. “I have no visibility into who the bad guys are in Afghanistan or Iraq. I read all the intel from the community and it sounds as thought [sic] we know a great deal, but in fact, when you push at it, you find out we haven’t got anything that is actionable.”

Three years into the U.S. nation building project, the Combined Forces Command Afghanistan sent Washington one of its regular “Security Updates” with a two-page list of “ANP Horror Stories” on pages 41 and 42. Police training at that point was in the hands of the State Department (or more precisely, its contractors), which took over from an early failed attempt led by the Germans. So the Secretary of Defense makes sure to alert the Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, about this “serious problem,” claiming that the two pages “were written in as graceful and non-inflammatory a way as is humanly possible.” Illiterate, underequipped, and unprepared, the police force seemingly had gained little from years of training by State Department contractors, perhaps mainly because police pay was so low that they extorted the very people they were supposed to protect. Later in 2005, the U.S. military would take over police training, and still fail to produce a professional force, not least because the whole idea was foreign to rural Afghans, who settled disputes primarily through village elders.

Document 10

Freedom of Information Act request to the State Department

Ronald Neumann arrived in Kabul as the U.S. ambassador in July 2005, with a long history of connection there as the son of a former U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan. He quickly sized up corruption as “a major threat to the country’s future” describing it as a “long tradition [that] grows like Topsy.” Neumann’s cable ascribes the endemic corruption to multiple factors, “privation” in the form of low official salaries, “insecurity” in the form of 35 years of war, “more foreign ‘loot’” especially the billions coming in from the U.S., “exposure to the outside world” of people better off materially, and “universality” in the sense that everyone was doing it. Neumann also acknowledges the reality that the U.S. was working with “some unsavory political figures” out of necessity. Redacted when the cable was declassified in 2011 are the specific names Neumann reported, and the specific actions he was recommending, but the full version released in 2014 revealed that at the top of his list was an untouchable – Afghan President Hamid Karzai’s half-brother, whom the CIA had paid for years, along with a number of provincial governors, most on U.S. covert payrolls as well. The cable also flags the second front in the Bush Afghan war – narcotics – reporting “opium could strangle the legitimate Afghanistan state in its cradle;” yet, rural Afghans relied on poppy production as their only lucrative crop.

Document 11

In this cable framed as a personal letter to the Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, U.S. Ambassador Ronald Neumann leads off with an ominous quote from a Taliban leader: "You have all the clocks but we have all the time." Neumann’s plea is for more resources in order to achieve “victory.” He says the U.S. is failing to fund and support fully the activities needed to bolster the Afghan economy, infrastructure, and reconstruction, and that failure is harming the American mission. "We have dared so greatly, and spent so much in blood and money that to try to skimp on what is needed for victory seems to me too risky." The Ambassador notes, "the supplemental decision recommendation to minimize economic assistance and leave out infrastructure plays into the Taliban strategy, not to ours." He warns that Taliban leaders are issuing statements that the U.S. would grow increasingly weary, while they gained momentum.

Document 12

U.S. Ambassador Ronald Neumann writes Washington again in February 2006 with some prescient warnings. He reports that violence in Afghanistan is on the rise but claims “violence does not indicate a failing policy; on the contrary we need to persevere in what we are doing.” Large unit force-on-force engagements devastated the Taliban in previous years, but “the Taliban now seems to understand the propaganda value of the [suicide] bomb and will use it to maximum advantage.” Ambassador Neumann defends the importance of “our work with the GOA [Government of Afghanistan] to extend and deepen its reach nationwide.” “The Taliban need not be intellectual giants to understand that their long-term strategy depends on keeping the government weak in the provinces.” Neumann says the insurgency is getting stronger largely due to the “four years that the Taliban has had to reorganize and think about their approach in a sanctuary [tribal areas in Pakistan] beyond the reach of either [Kabul or Islamabad].” If this sanctuary is “left unaddressed, it will also lead to the re-emergence of the same strategic threat to the United States that prompted our OEF [Operation Enduring Freedom] intervention over 4 years ago.”

Document 13

During May 2006, U.S. Central Command asked the eminent retired four-star general, Barry McCaffrey, to visit Afghanistan and Pakistan and make an assessment of the war (as he had done several times in Iraq). Gen. McCaffrey had served as the drug czar under President Clinton, commanded the “left hook” in the first Gulf War that destroyed so much of the Iraqi army, and won multiple medals for valor and for wounds during the Vietnam war, so his views had significant credibility. Here Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld recommends McCaffrey to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs. The McCaffrey document is couched as a report to his department chairs at the U.S. Military Academy (West Point) where he was an adjunct professor. The cover “snowflake” from Rumsfeld catches only a couple of points from McCaffrey: the lack of small arms for Afghan forces, and the recommendation for almost doubling the size of the Afghan army.

The full document presents a fascinating on-the-one-hand and on-the-other-hand story, praising U.S. and allied troops as well as Hamid Karzai while acknowledging rising violence and Taliban regrouping to the level of battalion-size engagements. McCaffrey warns that the Afghan leadership are “collectively terrified that we will tip-toe out of Afghanistan in the coming few years” and do not believe the U.S. is committed “to stay with them for the fifteen years required to create an independent functional nation-state which can survive in this dangerous part of the world.” He recommends almost doubling the size of the Afghan army (whose “courageous” troops “operate like armed mountain goats in the severe terrain”), claiming “[a] well-equipped, multi-ethnic, literate, and trained Afghan National Army is our ticket to be fully out of country in the year 2020.” A different ticket would be punched in 2021, not least because the Army never achieved any of McCaffrey’s four objectives. McCaffrey saw the Afghan police as “disastrous” but could only think of more money plus adding “a thousand jails, a hundred courts, and a dozen prisons.”

McCaffrey provocatively leads his section on Pakistan with this query: “The central question seems to be – are the Pakistanis playing a giant double-cross in which they absorb one billion dollars a year from the U.S. while pretending to support U.S. objectives to create a stable Afghanistan – while in fact actively supporting cross-border operations of the Taliban (that they created) – in order to give themselves a weak rear area threat for their central struggle with the Indians?” He goes on to doubt that Pakistani leader Pervez Musharraf was playing a deliberate double game, yet even phrasing the question in this way was striking, compared to Rumsfeld’s repeated public praise for Musharraf. Only two months later, Rumsfeld’s own civilian adviser, Dr. Marin Strmecki, would give him an even more detailed report entitled “Afghanistan at a Crossroads,” in which Strmecki doesn’t even see it as a question: “Since 2002, the Taliban has enjoyed a sanctuary in Pakistan.”

Document 14

U.S. Ambassador Ronald Neumann warns Washington in this cable that "we are not winning in Afghanistan; although we are far from losing" (that would take another 14 years). Echoing Gen. McCaffrey’s conclusions (Document 13), Neumann says the primary problem is a lack of political will to provide additional resources to bolster current strategy and to match increasing Taliban offensives. "At the present level of resources we can make incremental progress in some parts of the country, cannot be certain of victory, and could face serious slippage if the desperate popular quest for security continues to generate Afghan support for the Taliban .... Our margin for victory in a complex environment is shrinking, and we need to act now." The Taliban believe they are winning. That perception "scares the hell out of Afghans." "We are too slow." Rapidly increasing certain strategic initiatives such as equipping Afghan forces, taking out the Taliban leadership in Pakistan, and investing heavily in infrastructure can help the Americans regain the upper hand, Neumann declares. "We can still win. We are pursuing the right general policies on governance, security and development. But because we have not adjusted resources to the pace of the increased Taliban offensive and loss of internal Afghan support we face escalating risks today."

Document 15

Declassified by Department of Defense, September 2009

This is the key document behind the Obama “surge” in Afghanistan that produced the highest U.S. troop levels in the whole 20-year war. President Obama’s holdover Secretary of Defense, Robert Gates, had abruptly fired the U.S. commander in Afghanistan, Gen. David McKiernan, after only 11 months, and replaced him with a Special Operations general named Stanley McChrystal, a favorite of Central Command head Gen. David Petraeus, and an acolyte of the Petraeus counterinsurgency approach that had apparently succeeded in Iraq (critics said top Iraqi clerics had simply ordered a truce, for their own reasons). This 66-page assessment had a convoluted public history: written in August 2009, it leaked to the Washington Post in September, likely as part of Pentagon pressure on Obama to approve more troops, and the Pentagon declassified it right away. The McChrystal strategy called for a “properly resourced” counterinsurgency campaign, with at least 40,000 and as many as 60,000 more U.S. troops and massive aid, especially to build up the Afghan army. He wrote, “I believe the short-term fight will be decisive. Failure to gain the initiative and reverse insurgent momentum in the near-term (next 12 months) – while Afghan security capacity matures – risks an outcome where defeating the insurgency is no longer possible.”

McChrystal asked for 60,000 troops, Obama gave him 30,000 but with an 18-month deadline before they would start coming home, and neither the surge nor the deadline ever produced any “maturity” in Afghan security capacity. Testifying to the Senate in December 2009, McChrystal flatly declared “the next eighteen months will likely be decisive and ultimately enable success. In fact, we are going to win.” His 66 pages remain a testament to American military hubris, full of questionable assumptions – that most Afghans saw the Taliban as oppressors and would side with a government installed by foreigners, that most Afghans shared a national identity, and that the Pakistan sanctuaries would not keep the Taliban going indefinitely.

Document 16

The New York Times, Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Envoy’s Cables Show Worries on Afghan Plans,” January 25, 2010

During the Obama debate over whether to surge or not in Afghanistan, some of the strongest criticism of the McChrystal and Pentagon proposals for expanding the military footprint came from inside the government in classified channels – specifically from the former general who had served multiple tours in Afghanistan (Rumsfeld’s first “security coordinator”) and now served as Obama’s ambassador, Karl Eikenberry. This highly classified November 6, 2009, cable, captioned NODIS ARIES, is couched as a personal letter from Eikenberry to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, opposing the proposed troop influx, the vastly increased costs, the concomitant need for yet more civilians, and the resulting increase in Afghan dependency. Eikenberry spells out his reasons: first that Hamid Karzai “is not an adequate strategic partner” – “[h]e and much of his circle are only too happy to see us invest further. They assume we covet their territory for a never-ending war on terror and for military bases to use against surrounding powers.” Second, “we overestimate the ability of Afghan security forces to take over.” Perhaps most important, “[m]ore troops won’t end the insurgency as long as Pakistan sanctuaries remain,” and “Pakistan will remain the single greatest source of Afghan instability.”

Document 17

This follow-up cable (see Document 16) by Ambassador Eikenberry to Secretary Clinton, for her “eyes only,” may have undercut his earlier strong argument against the proposed troop surge. It’s possible that Clinton may have pushed back, or Eikenberry got word his opposition was unwelcome – her side of the correspondence is still classified. Here, Eikenberry just asks for more time to deliberate, a more wide-ranging process, looking at more options other than military counterinsurgency, and convening a high-level expert panel. He admits that more troops “will yield more security wherever they deploy, for as long as they stay.” But he points to the previous troop increase in 2008-2009, amounting to 30,000 soldiers, and says “overall violence and instability in Afghanistan intensified.” Neither the Afghan army nor government “has demonstrated the will or ability to take over lead security responsibility,” he continues. There is “scant reason to expect that further increases will further advance our strategic purposes; instead, they will dig us in more deeply.” Eikenberry lost this debate, and the Obama-Gates-McChrystal troop surge produced all-time high levels of U.S. troops in Afghanistan.

Document 18

Washington Post, The Afghanistan Papers, Freedom of Information lawsuit against SIGAR

Among the hundreds of “lessons learned” interviews undertaken by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction and obtained by Craig Whitlock of the Washington Post through two Freedom of Information lawsuits, this one stands out for its long view, its self-critical perspective, and its high policy level. Richard Boucher was the longest-serving State Department spokesman in history, starting under Madeline Albright, continuing under Colin Powell and even Condoleezza Rice, before taking over the South Asia portfolio at State from 2006 through 2009. Boucher candidly told the SIGAR interviewers in October 2015, “Did we know what we were doing – I think the answer is no. First we went in to get al-Qaeda, and to get al-Qaeda out of Afghanistan, and even without killing Bin Laden we did that. The Taliban was shooting back at us so we started shooting at them and they became the enemy. Ultimately, we kept expanding the mission.” Boucher confessed, “If there was ever a notion of mission creep it is Afghanistan.” His 12 pages of interview transcript include multiple striking observations worth reading in full, about corruption, about local governance and the lack thereof, about the U.S. military’s can-do attitude and where it leads, about roads not taken. His judgment about Afghanistan comes down to a long view: “The only time this country has worked properly was when it was a floating pool of tribes and warlords presided over by someone who had a certain eminence who was able to centralize them to the extent that they didn’t fight each other too much. I think this idea that we went in with, that this was going to become a state government like a U.S. state or something like that, was just wrong and is what condemned us to fifteen years of war instead of two or three.”

Document 19

SIGAR https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/testimony/SIGAR-20-19-TY.pdf

Congress created the SIGAR office in 2008 to combat waste, fraud, and abuse in the U.S. reconstruction effort in Afghanistan, and this statement marked the 22nd time the incumbent, John Sopko, had testified before Congress. The proximate cause of this hearing was the Washington Post publication in December 2019 of “The Afghanistan Papers” series by Craig Whitlock, based in large part on the Post’ s successful lawsuit against SIGAR to obtain copies of the hundreds of “lessons learned” interviews Sopko’s office had done with former policy makers, contractors, and military veterans of Afghanistan. Whitlock also relied on documents the National Security Archive had won through FOIA, notably the Donald Rumsfeld “snowflakes,” and concluded that the U.S. government had systematically misled the public about ostensible progress over nearly two decades in Afghanistan.

Whitlock himself covered this hearing, and his story included even more colorful quotations, apparently from the Q&A period, than can be found in this prepared testimony. For example, “There’s an odor of mendacity throughout the Afghanistan issue … mendacity and hubris.” “The problem is there is a disincentive, really, to tell the truth. We have created an incentive to almost require people to lie.” “When we talk about mendacity, when we talk about lying, it’s not just lying about a particular program. It’s lying by omissions. It turns out that everything that is bad news has been classified for the last few years.” (See Craig Whitlock, “Afghan war plagued by ‘mendacity’ and lies, inspector general tells Congress,” Washington Post , January 15, 2020.)

But the prepared statement is almost as chilling. Sopko told Congress that the system of rotation of U.S. personnel after a year or less in Afghanistan amounted to an “annual lobotomy.” Sopko gave specific examples of fake data and faulty metrics permeating the reconstruction effort: “Unfortunately, many of the claims that State, USAID, and others have made over time simply do not stand up to scrutiny.” Not least, Sopko concluded that “Unchecked corruption in Afghanistan undermined U.S. strategic goals – and we helped to foster that corruption” through “alliances of convenience with warlords” and “flood[ing] a small, weak economy with too much money, too fast.”

Document 20

SIGAR https://www.sigar.mil/pdf/quarterlyreports/2021-07-30qr-section2-security.pdf

This most recent quarterly report from the Special Inspector General provides some noteworthy evidence explaining why Washington would be so surprised by the rapid collapse of Afghan government forces in the two weeks after this was published. The 34-page “security” section leads with the ongoing withdrawal of U.S. and international troops, and the Taliban offensive that “avoided attacking U.S. and Coalition forces.” Maps in the middle of this section (pp. 54-56) show various open-source estimates for Taliban control over Afghani districts, and the report notes that the U.S. military ceased providing any unclassified estimates in 2019. From April to July, apparently, the number of Taliban-controlled districts went from 73 to 221, or more than half the total. Perhaps the most interesting page is page 62, with the sidebar on “the core challenge of properly assessing reconstruction’s effectiveness.” “For years, U.S. taxpayers were told that, although circumstances were difficult, success was achievable.” The document quotes Gen. David Petraeus in 2011, Gen. John Campbell in 2015, Gen. John Nicholson in 2017, and the Pentagon press secretary in 2021 all endorsing the effectiveness of the Afghan security forces. The SIGAR report comments on the $88 billion invested in those forces: “The question of whether that money was well spent will ultimately be answered by the fighting on the ground.”

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

Insurgency against communist rule (1978–92)

Conflict after 1992, casualties and repercussions.

- What is Afghanistan?

- Should the United States continue its use of drone strikes abroad in countries such as Afghanistan?

- Who was Mikhail Gorbachev?

- How did Mikhail Gorbachev become president of the Soviet Union?

- What is Mikhail Gorbachev known for?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Humanities LibreTexts - Afghan-Soviet War- 1979-89

- Afghan Wars - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

Afghan War , in the history of Afghanistan , the internal conflict that began in 1978 between anticommunist Islamic guerrillas and the Afghan communist government (aided in 1979–89 by Soviet troops), leading to the overthrow of the government in 1992. More broadly, the term also encompasses military activity within Afghanistan after 1992—but apart from the Afghanistan War (2001–14), a U.S.-led invasion launched in response to the September 11 attacks on the United States in 2001. By this broader definition, many analysts consider the internal Afghan War as lasting well into the 21st century and overlapping with the U.S.-led Afghanistan War.

The roots of the war lay in the overthrow of the centrist government of President Mohammad Daud Khan in April 1978 by left-wing military officers led by Nur Mohammad Taraki . Power was thereafter shared by two Marxist-Leninist political groups, the People’s (Khalq) Party and the Banner (Parcham) Party , which had earlier emerged from a single organization, the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan, and had reunited in an uneasy coalition shortly before the coup. The new government, which had little popular support, forged close ties with the Soviet Union , launched ruthless purges of all domestic opposition, and began extensive land and social reforms that were bitterly resented by the devoutly Muslim and largely anticommunist population. Insurgencies arose against the government among both tribal and urban groups, and all of these—known collectively as the mujahideen (Arabic: mujāhidūn , “those who engage in jihad ”)—were Islamic in orientation. These uprisings, along with internal fighting and coups within the government between the People’s and Banner factions, prompted the Soviets to invade the country in December 1979, sending in some 30,000 troops and toppling the short-lived presidency of People’s leader Hafizullah Amin . The aim of the Soviet operation was to prop up their new but faltering client state, now headed by Banner leader Babrak Karmal , but the mujahideen rebellion grew in response, spreading to all parts of the country. The Soviets initially left the suppression of the rebellion to the Afghan army, but the latter was beset by mass desertions and remained largely ineffective throughout the war.

The Afghan War quickly settled down into a stalemate, with about 100,000 Soviet troops controlling the cities, larger towns, and major garrisons and the mujahideen moving with relative freedom throughout the countryside. Soviet troops tried to crush the insurgency by various tactics, but the guerrillas generally eluded their attacks. The Soviets then attempted to eliminate the mujahideen’s civilian support by bombing and depopulating the rural areas. These tactics sparked a massive flight from the countryside; by 1982 some 2.8 million Afghans had sought asylum in Pakistan , and another 1.5 million had fled to Iran . The mujahideen were eventually able to neutralize Soviet air power through the use of shoulder-fired antiaircraft missiles supplied by the Soviet Union’s Cold War adversary, the United States .

The mujahideen were fragmented politically into a handful of independent groups, and their military efforts remained uncoordinated throughout the war. The quality of their arms and combat organization gradually improved, however, owing to experience and to the large quantity of arms and other war matériel shipped to the rebels, via Pakistan, by the United States and other countries and by sympathetic Muslims from throughout the world. In addition, an indeterminate number of Muslim volunteers—popularly termed “Afghan-Arabs,” regardless of their ethnicity—traveled from all parts of the world to join the opposition.

The war in Afghanistan became a quagmire for what by the late 1980s was a disintegrating Soviet Union. (The Soviets suffered some 15,000 dead and many more injured.) In 1988 the United States, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and the Soviet Union signed an agreement by which the latter would withdraw its troops (completed in 1989), and Afghanistan returned to nonaligned status. In April 1992 various rebel groups, together with newly rebellious government troops, stormed the besieged capital of Kabul and overthrew the communist president, Najibullah , who had succeeded Karmal in 1986.

A transitional government, sponsored by various rebel factions, proclaimed an Islamic republic, but jubilation was short-lived. President Burhanuddin Rabbani, leader of the Islamic Society (Jamʿiyyat-e Eslāmī), a major mujahideen group, refused to leave office in accordance with the power-sharing arrangement reached by the new government. Other mujahideen groups, particularly the Islamic Party (Ḥezb-e Eslāmī), led by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, surrounded Kabul and began to barrage the city with artillery and rockets. These attacks continued intermittently over the next several years as the countryside outside Kabul slipped into chaos .

Partly as a response, the Taliban (Pashto: “Students”), a puritanical Islamic group led by a former mujahideen commander, Mohammad Omar , emerged in the fall of 1994 and systematically seized control of the country, occupying Kabul in 1996. The Taliban—augmented by volunteers from various Islamic extremist groups sheltering in Afghanistan, many of whom were Afghan-Arab holdovers from the earlier conflict—soon controlled all but a small portion of northern Afghanistan, which was held by a loose coalition of mujahideen forces known as the Northern Alliance . Fighting continued at a stalemate until 2001, when the Taliban refused demands by the U.S. government to extradite Saudi Arabian exile Osama bin Laden , the leader of an Islamic extremist group, al-Qaeda , which had close ties with the Taliban and was accused of having launched terrorist attacks against the United States, including the group of devastating strikes on September 11. Subsequently, U.S. special operations forces, allied with Northern Alliance fighters, launched a series of military operations in Afghanistan that drove the Taliban from power by early December. ( See Afghanistan War .) After a period of transitional interim government, a republic was established in 2004, but the new government struggled well into the 21st century to secure centralized authority over the country against a powerful Taliban insurgency.

Afghanistan has never conducted a full census, and it is thus difficult to gauge the number of casualties suffered in the country since the outbreak of fighting. The best estimates available indicate that some 1.5 million Afghanis were killed before 1992—although the number killed during combat and the number killed as an indirect result of the conflict remain unclear. The casualty rate after 1992 is even less precise. Many thousands were killed as a direct result of factional fighting; hundreds or thousands of prisoners and civilians were executed by tribal, ethnic, or religious rivals; and a large number of combatants—and some noncombatants—were killed during the U.S. offensive. Moreover, tens of thousands died of starvation or of a variety of diseases, many of which in less-troubled times could have been easily treated, and hundreds of thousands were killed or injured by the numerous land mines in the country. (Afghanistan was, by the end of the 20th century, one of the most heavily mined countries in the world, and vast quantities of unexploded ordnance littered the countryside.) The number of Afghan refugees living abroad fluctuated over the years with the fighting and reached a peak of some six million people in the late 1980s.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

The American War in Afghanistan: A History

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The American War in Afghanistan is a full history of the war in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2020. It covers political, cultural, strategic, and tactical aspects of the war and details the actions and decision-making of the United States, Afghan government, and Taliban. The work follows a narrative format to go through the 2001 US invasion, the state-building of 2002–2005, the Taliban offensive of 2006, the US surge of 2009–2011, the subsequent drawdown, and the peace talks of 2019–2020. The focus is on the overarching questions of the war: Why did the United States fail? What opportunities existed to reach a better outcome? Why did the United States not withdraw from the war?

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 29 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 25 |

| October 2022 | 36 |

| October 2022 | 7 |

| October 2022 | 31 |

| October 2022 | 12 |

| October 2022 | 9 |

| October 2022 | 17 |

| October 2022 | 15 |

| October 2022 | 9 |

| October 2022 | 8 |

| October 2022 | 23 |

| October 2022 | 6 |

| October 2022 | 15 |

| October 2022 | 3 |

| October 2022 | 3 |

| October 2022 | 4 |

| October 2022 | 10 |

| October 2022 | 4 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 31 |

| October 2022 | 53 |

| October 2022 | 12 |

| October 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 37 |

| October 2022 | 55 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| November 2022 | 31 |

| November 2022 | 22 |

| November 2022 | 6 |

| November 2022 | 7 |

| November 2022 | 8 |

| November 2022 | 15 |

| November 2022 | 24 |

| November 2022 | 30 |

| November 2022 | 26 |

| November 2022 | 18 |

| November 2022 | 15 |

| November 2022 | 19 |

| November 2022 | 87 |

| November 2022 | 2 |

| November 2022 | 71 |

| November 2022 | 86 |

| November 2022 | 18 |

| November 2022 | 3 |

| November 2022 | 23 |

| November 2022 | 6 |

| November 2022 | 21 |

| November 2022 | 88 |

| November 2022 | 28 |

| November 2022 | 31 |

| November 2022 | 40 |

| November 2022 | 51 |

| November 2022 | 36 |

| November 2022 | 40 |

| December 2022 | 67 |

| December 2022 | 30 |

| December 2022 | 14 |

| December 2022 | 16 |

| December 2022 | 3 |

| December 2022 | 6 |

| December 2022 | 29 |

| December 2022 | 2 |

| December 2022 | 8 |

| December 2022 | 15 |

| December 2022 | 22 |

| December 2022 | 26 |

| December 2022 | 14 |

| December 2022 | 41 |

| December 2022 | 31 |

| December 2022 | 13 |

| December 2022 | 11 |

| December 2022 | 28 |

| December 2022 | 22 |

| December 2022 | 15 |

| December 2022 | 47 |

| December 2022 | 72 |