Ask the publishers to restore access to 500,000+ books.

Internet Archive Audio

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 916 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Essays of E. B. White.

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

comment Reviews

1,215 Views

16 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by lotu.t on November 4, 2011

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

Death of a Pig

“I just wanted to keep on raising a pig, full meal after full meal, spring into summer into fall.”

I spent several days and nights in mid-September with an ailing pig and I feel driven to account for this stretch of time, more particularly since the pig died at last, and I lived, and things might easily have gone the other way round and none left to do the accounting. Even now, so close to the event, I cannot recall the hours sharply and am not ready to say whether death came on the third night or the fourth night. This uncertainty afflicts me with a sense of personal deterioration; if I were in decent health I would know how many nights I had sat up with a pig.

The scheme of buying a spring pig in blossom time, feeding it through summer and fall, and butchering it when the solid cold weather arrives, is a familiar scheme to me and follows an antique pattern. It is a tragedy enacted on most farms with perfect fidelity to the original script. The murder, being premeditated, is in the first degree but is quick and skillful, and the smoked bacon and ham provide a ceremonial ending whose fitness is seldom questioned.

Once in a while something slips — one of the actors goes up in his lines and the whole performance stumbles and halts. My pig simply failed to show up for a meal. The alarm spread rapidly. The classic outline of the tragedy was lost. I found myself cast suddenly in the role of pig’s friend and physician — a farcical character with an enema bag for a prop. I had a presentiment, the very first afternoon, that the play would never regain its balance and that my sympathies were now wholly with the pig. This was slapstick — the sort of dramatic treatment which instantly appealed to my old dachshund, Fred, who joined the vigil, held the bag, and, when all was over, presided at the interment. When we slid the body into the grave, we both were shaken to the core. The loss we felt was not the loss of ham but the loss of pig. He had evidently become precious to me, not that he represented a distant nourishment in a hungry time, but that he had suffered in a suffering world. But I’m running ahead of my story and shall have to go back. My pigpen is at the bottom of an old orchard below the house. The pigs I have raised have lived in a faded building which once was an icehouse. There is a pleasant yard to move about in, shaded by an apple tree which overhangs the low rail fence. A pig couldn’t ask for anything better — or none has, at any rate. The sawdust in the icehouse makes a comfortable bottom in which to root, and a warm bed. This sawdust, however, came under suspicion when the pig took sick. One of my neighbors said he thought the pig would have done better on new ground — the same principle that applies in planting potatoes. He said there might be something unhealthy about that sawdust, that he never thought well of sawdust. It was about four o’clock in the afternoon when I first noticed that there was something wrong with the pig. He failed to appear at the trough for his supper, and when a pig (or a child) refuses supper a chill wave of fear runs through any household, or icehousehold. After examining my pig, who was stretched out in the sawdust inside the building, I went to the phone and cranked it four times. Mr. Henderson answered. “What’s good for a sick pig?” I asked. (There is never any identification needed on a country phone; the person on the other end knows who is talking by the sound of the voice and by the character of the question.) “I don’t know, I never had a sick pig,” said Mr. Henderson, “but I can find out quick enough. You hang up and I’ll call Irving.” Mr. Henderson was back on the line again in five minutes. “Irving says roll him over on his back and give him two ounces of castor oil or sweet oil, and if that doesn’t do the trick give him an injection of soapy water. He says he’s almost sure the pig’s plugged up, and even if he’s wrong, it can’t do any harm.” I thanked Mr. Henderson. I didn’t go right down to the pig, though. I sank into a chair and sat still for a few minutes to think about my troubles, and then I got up and went to the barn, catching up on some odds and ends that needed tending to. Unconsciously I held off, for an hour, the deed by which I would officially recognize the collapse of the performance of raising a pig; I wanted no interruption in the regularity of feeding, the steadiness of growth, the even succession of days. I wanted no interruption, wanted no oil, no deviation. I just wanted to keep on raising a pig, full meal after full meal, spring into summer into fall. I didn’t even know whether there were two ounces of castor oil on the place.

Shortly after five o’clock I remembered that we had been invited out to dinner that night and realized that if I were to dose a pig there was no time to lose. The dinner date seemed a familiar conflict: I move in a desultory society and often a week or two will roll by without my going to anybody’s house to dinner or anyone’s coming to mine, but when an occasion does arise, and I am summoned, something usually turns up (an hour or two in advance) to make all human intercourse seem vastly inappropriate. I have come to believe that there is in hostesses a special power of divination, and that they deliberately arrange dinners to coincide with pig failure or some other sort of failure. At any rate, it was after five o’clock and I knew I could put off no longer the evil hour. When my son and I arrived at the pigyard, armed with a small bottle of castor oil and a length of clothesline, the pig had emerged from his house and was standing in the middle of his yard, listlessly. He gave us a slim greeting. I could see that he felt uncomfortable and uncertain. I had brought the clothesline thinking I’d have to tie him (the pig weighed more than a hundred pounds) but we never used it. My son reached down, grabbed both front legs, upset him quickly, and when he opened his mouth to scream I turned the oil into his throat — a pink, corrugated area I had never seen before. I had just time to read the label while the neck of the bottle was in his mouth. It said Puretest. The screams, slightly muffled by oil, were pitched in the hysterically high range of pigsound, as though torture were being carried out, but they didn’t last long: it was all over rather suddenly, and, his legs released, the pig righted himself. In the upset position the corners of his mouth had been turned down, giving him a frowning expression. Back on his feet again, he regained the set smile that a pig wears even in sickness. He stood his ground, sucking slightly at the residue of oil; a few drops leaked out of his lips while his wicked eyes, shaded by their coy little lashes, turned on me in disgust and hatred. I scratched him gently with oily fingers and he remained quiet, as though trying to recall the satisfaction of being scratched when in health, and seeming to rehearse in his mind the indignity to which he had just been subjected. I noticed, as I stood there, four or five small dark spots on his back near the tail end, reddish brown in color, each about the size of a housefly. I could not make out what they were. They did not look troublesome but at the same time they did not look like mere surface bruises or chafe marks. Rather they seemed blemishes of internal origin. His stiff white bristles almost completedly hid them and I had to part the bristles with my fingers to get a good look. Several hours later, a few minutes before midnight, having dined well and at someone else’s expense, I returned to the pighouse with a flashlight. The patient was asleep. Kneeling, I felt his ears (as you might put your hand on the forehead of a child) and they seemed cool, and then with the light made a careful examination of the yard and the house for sign that the oil had worked. I found none and went to bed. We had been having an unseasonable spell of weather — hot, close days, with the fog shutting in every night, scaling for a few hours in midday, then creeping back again at dark, drifting in first over the trees on the point, then suddenly blowing across the fields, blotting out the world and taking possession of houses, men, and animals. Everyone kept hoping for a break, but the break failed to come. Next day was another hot one. I visited the pig before breakfast and tried to tempt him with a little milk in his trough. He just stared at it, while I made a sucking sound through my teeth to remind him of past pleasures of the feast. With very small, timid pigs, weanlings, this ruse is often quite successful and will encourage them to eat; but with a large, sick pig the ruse is senseless and the sound I made must have made him feel, if anything, more miserable. He not only did not crave food, he felt a positive revulsion to it. I found a place under the apple tree where he had vomited in the night. At this point, although a depression had settled over me, I didn’t suppose that I was going to lose my pig. From the lustiness of a healthy pig a man derives a feeling of personal lustiness; the stuff that goes into the trough and is received with such enthusiasm is an earnest of some later feast of his own, and when this suddenly comes to an end and the food lies stale and untouched, souring in the sun, the pig’s imbalance becomes the man’s, vicariously, and life seems insecure, displaced, transitory.

As my own spirits declined, along with the pig’s, the spirits of my vile old dachshund rose. The frequency of our trips down the footpath through the orchard to the pigyard delighted him, although he suffers greatly from arthritis, moves with difficulty, and would be bedridden if he could find anyone willing to serve him meals on a tray. He never missed a chance to visit the pig with me, and he made many professional calls on his own. You could see him down there at all hours, his white face parting the grass along the fence as he wobbled and stumbled about, his stethoscope dangling — a happy quack, writing his villainous prescriptions and grinning his corrosive grin. When the enema bag appeared, and the bucket of warm suds, his happiness was complete, and he managed to squeeze his enormous body between the two lowest rails of the yard and then assumed full charge of the irrigation. Once, when I lowered the bag to check the flow, he reached in and hurriedly drank a few mouthfuls of the suds to test their potency. I have noticed that Fred will feverishly consume any substance that is associated with trouble — the bitter flavor is to his liking. When the bag was above reach, he concentrated on the pig and was everywhere at once, a tower of strength and inconvenience. The pig, curiously enough, stood rather quietly through this colonic carnival, and the enema, though ineffective, was not as difficult as I had anticipated. I discovered, though, that once having given a pig an enema there is no turning back, no chance of resuming one of life’s more stereotyped roles. The pig’s lot and mine were inextricably bound now, as though the rubber tube were the silver cord. From then until the time of his death I held the pig steadily in the bowl of my mind; the task of trying to deliver him from his misery became a strong obsession. His suffering soon became the embodiment of all earthly wretchedness. Along toward the end of the afternoon, defeated in physicking, I phoned the veterinary twenty miles away and placed the case formally in his hands. He was full of questions, and when I casually mentioned the dark spots on the pig’s back, his voice changed its tone. “I don’t want to scare you,” he said, “but when there are spots, erysipelas has to be considered.” Together we considered erysipelas, with frequent interruptions from the telephone operator, who wasn't sure the connection had been established. “If a pig has erysipelas can he give it to a person?” I asked. “Yes, he can,” replied the vet. “Have they answered?” asked the operator. “Yes, they have,” I said. Then I addressed the vet again. “You better come over here and examine this pig right away.” “I can’t come myself,” said the vet, “but McDonald can come this evening if that’s all right. Mac knows more about pigs than I do anyway. You needn't worry too much about the spots. To indicate erysipelas they would have to be deep hemorrhagic infarcts.” “Deep hemorrhagic what?” I asked. “Infarcts,” said the vet. “Have they answered?” asked the operator. “Well,” I said, “I don’t know what you’d call these spots, except they’re about the size of a housefly. If the pig has erysipelas I guess I have it, too, by this time, because we’ve been very close lately.” “McDonald will be over,” said the vet. I hung up. My throat felt dry and I went to the cupboard and got a bottle of whiskey. Deep hemorrhagic infarcts — the phrase began fastening its hooks in my head. I had assumed that there could be nothing much wrong with a pig during the months it was being groomed for murder; my confidence in the essential health and endurance of pigs had been strong and deep, particularly in the health of pigs that belonged to me and that were part of my proud scheme. The awakening had been violent and I minded it all the more because I knew that what could be true of my pig could be true also of the rest of my tidy world. I tried to put this distasteful idea from me, but it kept recurring. I took a short drink of the whiskey and then, although I wanted to go down to the yard and look for fresh signs, I was scared to. I was certain I had erysipelas. It was long after dark and the supper dishes had been put away when a car drove in and McDonald got out. He had a girl with him. I could just make her out in the darkness — she seemed young and pretty. “This is Miss Wyman,” he said. “We’ve been having a picnic supper on the shore, that’s why I’m late.” McDonald stood in the driveway and stripped off his jacket, then his shirt. His stocky arms and capable hands showed up in my flashlight’s gleam as I helped him find his coverall and get zipped up. The rear seat of his car contained an astonishing amount of paraphernalia, which he soon overhauled, selecting a chain, a syringe, a bottle of oil, a rubber tube, and some other things I couldn’t identify. Miss Wyman said she’d go along with us and see the pig. I led the way down the warm slope of the orchard, my light picking out the path for them, and we all three climbed the fence, entered the pighouse, and squatted by the pig while McDonald took a rectal reading. My flashlight picked up the glitter of an engagement ring on the girl’s hand. “No elevation,” said McDonald, twisting the thermometer in the light. “You needn’t worry about erysipelas.” He ran his hand slowly over the pig’s stomach and at one point the pig cried out in pain. “Poor piggledy-wiggledy!” said Miss Wyman. The treatment I had been giving the pig for two days was then repeated, somewhat more expertly, by the doctor, Miss Wyman and I handing him things as he needed them — holding the chain that he had looped around the pig’s upper jaw, holding the syringe, holding the bottle stopper, the end of the tube, all of us working in darkness and in comfort, working with the instinctive teamwork induced by emergency conditions, the pig unprotesting, the house shadowy, protecting, intimate. I went to bed tired but with a feeling of relief that I had turned over part of the responsibility of the case to a licensed doctor. I was beginning to think, though, that the pig was not going to live.

He died twenty-four hours later, or it might have been forty-eight — there is a blur in time here, and I may have lost or picked up a day in the telling and the pig one in the dying. At intervals during the last day I took cool fresh water down to him and at such times as he found the strength to get to his feet he would stand with head in the pail and snuffle his snout around. He drank a few sips but no more; yet it seemed to comfort him to dip his nose in water and bobble it about, sucking in and blowing out through his teeth. Much of the time, now, he lay indoors half buried in sawdust. Once, near the last, while I was attending him I saw him try to make a bed for himself but he lacked the strength, and when he set his snout into the dust he was unable to plow even the little furrow he needed to lie down in. He came out of the house to die. When I went down, before going to bed, he lay stretched in the yard a few feet from the door. I knelt, saw that he was dead, and left him there: his face had a mild look, expressive neither of deep peace nor of deep suffering, although I think he had suffered a good deal. I went back up to the house and to bed, and cried internally — deep hemorrhagic intears. I didn’t wake till nearly eight the next morning, and when I looked out the open window the grave was already being dug, down beyond the dump under a wild apple. I could hear the spade strike against the small rocks that blocked the way. Never send to know for whom the grave is dug, I said to myself, it’s dug for thee. Fred, I well knew, was supervising the work of digging, so I ate breakfast slowly. It was a Saturday morning. The thicket in which I found the gravediggers at work was dark and warm, the sky overcast. Here, among alders and young hackmatacks, at the foot of the apple tree, Howard had dug a beautiful hole, five feet long, three feet wide, three feet deep. He was standing in it, removing the last spadefuls of earth while Fred patrolled the brink in simple but impressive circles, disturbing the loose earth of the mound so that it trickled back in. There had been no rain in weeks and the soil, even three feet down, was dry and powdery. As I stood and stared, an enormous earthworm which had been partially exposed by the spade at the bottom dug itself deeper and made a slow withdrawal, seeking even remoter moistures at even lonelier depths. And just as Howard stepped out and rested his spade against the tree and lit a cigarette, a small green apple separated itself from a branch overhead and fell into the hole. Everything about this last scene seemed overwritten—the dismal sky, the shabby woods, the imminence of rain, the worm (legendary bedfellow of the dead), the apple (conventional garnish of a pig). But even so, there was a directness and dispatch about animal burial, I thought, that made it a more decent affair than human burial: there was no stopover in the undertaker’s foul parlor, no wreath nor spray; and when we hitched a line to the pig’s hind legs and dragged him swiftly from his yard, throwing our weight into the harness and leaving a wake of crushed grass and smoothed rubble over the dump, ours was a businesslike procession, with Fred, the dishonorable pallbearer, staggering along in the rear, his perverse bereavement showing in every seam in his face; and the post mortem performed handily and swiftly right at the edge of the grave, so that the inwards which had caused the pig’s death preceded him into the ground and he lay at last resting squarely on the cause of his own undoing. I threw in the first shovelful, and then we worked rapidly and without talk, until the job was complete. I picked up the rope, made it fast to Fred’s collar (he is a notorious ghoul), and we all three filed back up the path to the house, Fred bringing up the rear and holding back every inch of the way, feigning unusual stiffness. I noticed that although he weighed far less than the pig, he was harder to drag, being possessed of the vital spark. The news of the death of my pig traveled fast and far, and I received many expressions of sympathy from friends and neighbors, for no one took the event lightly and the premature expiration of a pig is, I soon discovered, a departure which the community marks solemnly on its calendar, a sorrow in which it feels fully involved. I have written this account in penitence and in grief, as a man who failed to raise his pig, and to explain my deviation from the classic course of so many raised pigs. The grave in the woods is unmarked, but Fred can direct the mourner to it unerringly and with immense good will, and I know he and I shall often revisit it, singly and together, in seasons of reflection and despair, on flagless memorial days of our own choosing.

About the Author

- Humanities ›

- English Grammar ›

What E.B. White Has to Say About Writing

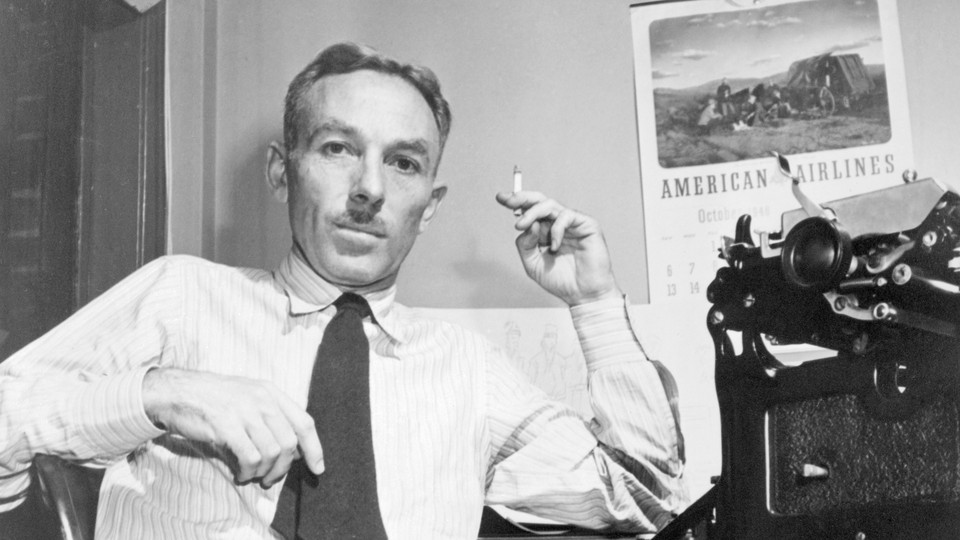

New York Times Co./Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Meet essayist E.B. White—and consider the advice he has to offer on writing and the writing process . Andy, as he was known to friends and family, spent the last 50 years of his life in an old white farmhouse overlooking the sea in North Brooklin, Maine. That's where he wrote most of his best-known essays, three children's books, and a best-selling style guide .

Introduction to E.B. White

A generation has grown up since E.B. White died in that farmhouse in 1985, and yet his sly, self-deprecating voice speaks more forcefully than ever. In recent years, Stuart Little has been turned into a franchise by Sony Pictures, and in 2006 a second film adaptation of Charlotte's Web was released. More significantly, White's novel about "some pig" and a spider who was "a true friend and a good writer" has sold more than 50 million copies over the past half-century.

Yet unlike the authors of most children's books, E.B. White is not a writer to be discarded once we slip out of childhood. The best of his casually eloquent essays—which first appeared in Harper's , The New Yorker , and The Atlantic in the 1930s, '40s, and '50s—have been reprinted in Essays of E.B. White (Harper Perennial, 1999). In "Death of a Pig," for instance, we can enjoy the adult version of the tale that was eventually shaped into Charlotte's Web . In "Once More to the Lake," White transformed the hoariest of essay topics—"How I Spent My Summer Vacation"—into a startling meditation on mortality.

For readers with ambitions to improve their own writing, White provided The Elements of Style (Penguin, 2005)—a lively revision of the modest guide first composed in 1918 by Cornell University professor William Strunk, Jr. It appears in our short list of essential Reference Works for Writers .

White was awarded the Gold Medal for Essays and Criticism of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award, the National Medal for Literature, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 1973 he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

E.B. White's Advice to a Young Writer

What do you do when you're 17 years old, baffled by life, and certain only of your dream to become a professional writer? If you had been "Miss R" 35 years ago, you would have composed a letter to your favorite author, seeking his advice. And 35 years ago, you would have received this reply from E. B. White:

Dear Miss R: At seventeen, the future is apt to seem formidable, even depressing. You should see the pages of my journal circa 1916. You asked me about writing—how I did it. There is no trick to it. If you like to write and want to write, you write, no matter where you are or what else you are doing or whether anyone pays any heed. I must have written half a million words (mostly in my journal) before I had anything published, save for a couple of short items in St. Nicholas. If you want to write about feelings, about the end of summer, about growing, write about it. A great deal of writing is not "plotted"—most of my essays have no plot structure, they are a ramble in the woods, or a ramble in the basement of my mind. You ask, "Who cares?" Everybody cares. You say, "It's been written before." Everything has been written before.

I went to college but not direct from high school; there was an interval of six or eight months. Sometimes it works out well to take a short vacation from the academic world—I have a grandson who took a year off and got a job in Aspen, Colorado. After a year of skiing and working, he is now settled into Colby College as a freshman. But I can't advise you, or won't advise you, on any such decision. If you have a counselor at school, I'd seek the counselor's advice. In college (Cornell), I got on the daily newspaper and ended up as editor of it. It enabled me to do a lot of writing and gave me a good journalistic experience. You are right that a person's real duty in life is to save his dream, but don't worry about it and don't let them scare you. Henry Thoreau, who wrote Walden, said, "I learned this at least by my experiment: that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours." The sentence, after more than a hundred years, is still alive. So, advance confidently. And when you write something, send it (neatly typed) to a magazine or a publishing house. Not all magazines read unsolicited contributions, but some do. The New Yorker is always looking for new talent. Write a short piece for them, send it to The Editor. That's what I did forty-some years ago. Good luck. Sincerely, E. B. White

Whether you're a young writer like "Miss R" or an older one, White's counsel still holds. Advance confidently, and good luck.

E.B. White on a Writer's Responsibility

In an interview for The Paris Review in 1969, White was asked to express his "views about the writer's commitment to politics, international affairs." His response:

A writer should concern himself with whatever absorbs his fancy, stirs his heart, and unlimbers his typewriter. I feel no obligation to deal with politics. I do feel a responsibility to society because of going into print: a writer has the duty to be good, not lousy; true, not false; lively, not dull; accurate, not full of error. He should tend to lift people up, not lower them down. Writers do not merely reflect and interpret life, they inform and shape life.

E.B. White on Writing for the Average Reader

In an essay titled "Calculating Machine," White wrote disparagingly about the "Reading-Ease Calculator," a device that presumed to measure the "readability" of an individual's writing style.

There is, of course, no such thing as reading ease of written matter. There is the ease with which matter can be read, but that is a condition of the reader, not of the matter.

There is no average reader, and to reach down toward this mythical character is to deny that each of us is on the way up, is ascending.

It is my belief that no writer can improve his work until he discards the dulcet notion that the reader is feebleminded, for writing is an act of faith, not of grammar. Ascent is at the heart of the matter. A country whose writers are following the calculating machine downstairs is not ascending—if you will pardon the expression—and a writer who questions the capacity of the person at the other end of the line is not a writer at all, merely a schemer. The movies long ago decided that a wider communication could be achieved by a deliberate descent to a lower level, and they walked proudly down until they reached the cellar. Now they are groping for the light switch, hoping to find the way out.

E.B. White on Writing With Style

In the final chapter of The Elements of Style (Allyn & Bacon, 1999), White presented 21 "suggestions and cautionary hints" to help writers develop an effective style. He prefaced those hints with this warning:

Young writers often suppose that style is a garnish for the meat of prose, a sauce by which a dull dish is made palatable. Style has no such separate entity; is nondetachable, unfilterable. The beginner should approach style warily, realizing that it is himself he is approaching, no other; and he should begin by turning resolutely away from all devices that are popularly believed to indicate style—all mannerisms, tricks, adornments. The approach to style is by way of plainness, simplicity, orderliness, sincerity.

Writing is, for most, laborious and slow. The mind travels faster than the pen; consequently, writing becomes a question of learning to make occasional wing shots, bringing down the bird of thought as it flashes by. A writer is a gunner, sometimes waiting in his blind for something to come in, sometimes roaming the countryside hoping to scare something up. Like other gunners, he must cultivate patience; he may have to work many covers to bring down one partridge.

You'll notice that while advocating a plain and simple style, White conveyed his thoughts through artful metaphors .

E.B. White on Grammar

Despite the prescriptive tone of The Elements of Style , White's own applications of grammar and syntax were primarily intuitive, as he once explained in The New Yorker :

Usage seems to us peculiarly a matter of ear. Everyone has his own prejudices, his own set of rules, his own list of horribles. The English language is always sticking a foot out to trip a man. Every week we get thrown, writing merrily along. English usage is sometimes more than mere taste, judgment, and education—sometimes it's sheer luck, like getting across a street.

Essays of E. B. White

By e. b. white.

- ★ ★ ★ ★ 4.0 (1 rating) ·

- 23 Want to read

- 1 Currently reading

- 1 Have read

Preview Book

My Reading Lists:

Use this Work

Create a new list

My book notes.

My private notes about this edition:

Check nearby libraries

- Library.link

Buy this book

Thirty-one of E.B. White's essays grouped under such headings as "The Farm," "The Planet," "Memories," and "Books, Men, and Writing."

Previews available in: English

Showing 10 featured editions. View all 10 editions?

Add another edition?

Book Details

Classifications, source records, work description.

When E.B. White received the Gold Medal for Essays and Criticism from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the following citation, here quoted in part, accompanied the award:

"If we are remembered as a civilized era, I think it will be partly because of E.B. White. The historians of the future will decide that a writer of such grace and control could not have been produced by a generation wholly lacking in such qualities, and we will shine by reflection in his gentle light.

"Of all the gifts he has given us in his apparently casual essays, the best gift is himself. He has permitted us to meet a man who is both cheerful and wises, the owner of an uncommon sense that is lit by laughter. When he writes of large subjects he does not make them larger and windier than they are, and when he writes of small things they are never insignificant. He is, in fact, a civilized human being - an order of man that has always been distinguished for its rarity."

The essays in this companion volume to the Letters to E.B. White have been selected by White himself, from a lifetime of writing. "I have chosen the ones that have amused me in the rereading." he writes in the Foreword, "along with a few that seemed to have the odor of durability clinging to them." The Essays of E.B. White are incomparable, like his Letters, this is a volume to treasure and savor at one's leisure.

Community Reviews (0)

- Created October 16, 2008

- 22 revisions

Wikipedia citation

Copy and paste this code into your Wikipedia page. Need help?

Recently Visited

Top Categories

Children's Books

Discover Diverse Voices

More Categories

All Categories

New & Trending

Deals & Rewards

Best Sellers

From Our Editors

Memberships

Communities

- Literature & Fiction

- History & Criticism

Amazon Prime Free Trial

FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button and confirm your Prime free trial.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited FREE Prime delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -45% $10.39 $ 10 . 39 FREE delivery December 9 - 12 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

We offer easy, convenient returns with at least one free return option: no shipping charges. All returns must comply with our returns policy.

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select your preferred free shipping option

- Drop off and leave!

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $8.12 $ 8 . 12 FREE delivery Friday, December 13 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: RNA TRADE LLC

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Essays of E. B. White (Perennial Classics) Paperback – December 12, 2006

Purchase options and add-ons.

"Some of the finest examples of contemporary, genuinely American prose. White's style incorporates eloquence without affection, profundity without pomposity, and wit without frivolity or hostility. Like his predecessors Thoreau and Twain, White's creative, humane, and graceful perceptions are an education for the sensibilities." — Washington Post

The classic collection by one of the greatest essayists of our time.

Selected by E.B. White himself, the essays in this volume span a lifetime of writing and a body of work without peer. "I have chosen the ones that have amused me in the rereading," he writes in the Foreword, "alone with a few that seemed to have the odor of durability clinging to them." These essays are incomparable; this is a volume to treasure and savor at one's leisure.

- Print length 384 pages

- Language English

- Publication date December 12, 2006

- Dimensions 5.31 x 0.86 x 8 inches

- ISBN-10 0060932236

- ISBN-13 978-0060932237

- Lexile measure 1200L

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

"His voice rumbles with authority through sentences of surpassing grace. In his more than fifty years at The New Yorker, White set a standard of writerly craft for that supremely well-wrought magazine. In genial, perfectly poised essay after essay, he has wielded the English language with as much clarity and control as any American of his time." — Raymond Sokolov, Newsweek

"Some of the finest examples of contemporary, genuinely American prose. White's style incorporates eloquence without affection, profundity without pomposity, and wit without frivolity or hostility. Like his predecessors Thoreau and Twain, White's creative, humane, and graceful perceptions are an education for the sensibilities." — Washington Post

"The abiding spirit of these essays is humane, compassionate, traditionalistic. No matter what his subject, White always keeps his eye on the long view and the larger perspective. There are times when I feel his work is as much a national resource as the Liberty Bell, a call to the best and noblest in us." — Jonathan Yardley, San Francisco Examiner

From the Back Cover

About the author.

E. B. White , the author of such beloved classics as Charlotte's Web , Stuart Little , and The Trumpet of the Swan , was born in Mount Vernon, New York. He graduated from Cornell University in 1921 and, five or six years later, joined the staff of the New Yorker magazine, then in its infancy. He died on October 1, 1985, and was survived by his son and three grandchildren.

Mr. White's essays have appeared in Harper's magazine, and some of his other books are: One Man's Meat , The Second Tree from the Corner , Letters of E. B. White , Essays of E. B. White , and Poems and Sketches of E. B. White . He won countless awards, including the 1971 National Medal for Literature and the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award, which commended him for making a "substantial and lasting contribution to literature for children."

During his lifetime, many young readers asked Mr. White if his stories were true. In a letter written to be sent to his fans, he answered, "No, they are imaginary tales . . . But real life is only one kind of life—there is also the life of the imagination."

From The Washington Post

"Some of the finest examples of contemporary, genuinely American prose. White's style incorporates eloquence without affection, profundity without pomposity, and wit without frivolity or hostility. Like his predecessors Thoreau and Twain, White's creative, humane, and graceful perceptions are an education for the sensibilities."

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Essays of e. b. white, good-bye to forty-eighth street, turtle bay, november 12, 1957.

For some weeks now I have been engaged in dispersing the contents of this apartment, trying to persuade hundreds of inanimate objects to scatter and leave me alone. It is not a simple matter. I am impressed by the reluctance of one's worldly goods to go out again into the world. During September I kept hoping that some morning, as by magic, all books, pictures, records, chairs, beds, curtains, lamps, china, glass, utensils, keepsakes would drain away from around my feet, like the outgoing tide, leaving me standing silent on a bare beach, But this did not happen. My wife and I diligently sorted and discarded things from day to day, and packed other objects for the movers, but a sixroom apartment holds as much paraphernalia as an aircraft carrier. You can whittle away at it, but to empty the place completely takes real ingenuity and great staying power. On one of the mornings of disposal, a man from a second-hand bookstore visited us, bought several hundred books, and told us of the death of his brother, the word "cancer" exploding in the living room like a time bomb detonated by his grief. Even after he had departed with his heavy load, there seemed to be almost as many books as before, and twice as much sorrow.

Every morning, when I left for work, I would take something in my hand and walk off with it, for deposit in the big municipal wire trash basket at the corner of Third, on the theory that the physical act of disposal was the real key to the problem. My wife, a strategist, knew better and began quietly mobilizing the forces that would eventually put our goods to rout. A man could walk away for a thousand mornings carrying something with him to the corner and there would still be a home full of stuff. It is not possible to keep abreast of the normal tides of acquisition. A home is like a reservoir equipped with a check valve: the valve permits influx but prevents outflow. Acquisition goes on night and day -- smoothly, subtly, imperceptibly. I have no sharp taste for acquiring things, but it is not necessary to desire things in order to acquire them. Goods and chattels seek a man out; they find him even though his guard is up. Books and oddities arrive in the mail. Gifts arrive on anniversaries and fete days. Veterans send ballpoint pens. Banks send memo books. If you happen to be a writer, readers send whatever may be cluttering up their own lives; I had a man once send me a chip of wood that showed the marks of a beaver's teeth. Someone dies, and a little trickle of indestructible keepsakes appears, to swell the flood. This steady influx is not counterbalanced by any comparable outgo. Under ordinary circumstances, the only stuff that leaves a home is paper trash and garbage; everything else stays on and digs in.

Lately we haven't spent our nights in the apartment; we are bivouacked in a hotel and just come here mornings to continue the work. Each of us has a costume. My wife steps into a cotton dress while I shift into midnight-blue tropical pants and bowling shoes. Then we buckle down again to the unending task.

All sorts of special problems arise during the days of disposal. Anyone who is willing to put his mind to it can get rid of a chair, say, but what about a trophy? Trophies are like leeches. The ones made of paper, such as a diploma from a school or a college, can be burned if you have the guts to light the match, but the ones made of bronze not only are indestructible but are almost impossible to throw away, because they usually carry your name, and a man doesn't like to throw away his good name, or even his bad one. Some busybody might find it. People differ in their approach to trophies, of course. In watching Edward R. Murrow's "Person to Person" program on television, I have seen several homes that contained a "trophy room," in which the celebrated pack rat of the house had assembled all his awards, so that they could give out the concentrated aroma of achievement whenever he wished to loiter in such an atmosphere. This is all very well if you enjoy the stale smell of success, but if a man doesn't care for that air he is in a real fix when disposal time comes up. One day a couple of weeks ago, I sat for a while staring moodily at a plaque that had entered my life largely as a result of some company's zest for promotion. It was bronze on walnut, heavy enough to make an anchor for a rowboat, but I didn't need a rowboat anchor, and this thing had my name on it. By deft work with a screwdriver, I finally succeeded in prying the nameplate off; I pocketed this, and carried the mutilated remains to the corner, where the wire basket waited. The work exhausted me more than did the labor for which the award was presented.

Another day, I found myself on a sofa between the chip of wood gnawed by the beaver and an honorary hood I had once worn in an academic procession. What I really needed at the moment was the beaver himself, to eat the hood. I shall never wear the hood again, but I have too weak a character to throw it away, and I do not doubt that it will tag along with me to the end of my days, not keeping me either warm or happy but occupying a bit of my attic space.

Right in the middle of the dispersal, while the mournful rooms were still loaded with loot, I had a wonderful idea: we would shut the apartment, leave everything to soak for a while, and go to the Fryeburg Fair, in Maine, where we could sit under a tent at a cattle auction and watch somebody else trying to dispose of something. A fair, of course, is a dangerous spot if a man is hoping to avoid acquisition, and the truth is I came close to acquiring a very pretty whiteface heifer, safe in calf-which would...

Product details

- Publisher : Harper Perennial Modern Classics; Reprint edition (December 12, 2006)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 384 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0060932236

- ISBN-13 : 978-0060932237

- Lexile measure : 1200L

- Item Weight : 2.31 pounds

- Dimensions : 5.31 x 0.86 x 8 inches

- #157 in Essays (Books)

- #183 in Author Biographies

- #1,741 in Memoirs (Books)

About the author

E. b. white.

E.B. White, the author of twenty books of prose and poetry, was awarded the 1970 Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal for his children's books, Stuart Little and Charlotte's Web. This award is now given every three years "to an author or illustrator whose books, published in the United States, have, over a period of years, make a substantial and lasting contribution to literature for children." The year 1970 also marked the publication of Mr. White's third book for children, The Trumpet of the Swan, honored by The International Board on Books for Young People as an outstanding example of literature with international importance. In 1973, it received the Sequoyah Award (Oklahoma) and the William Allen White Award (Kansas), voted by the school children of those states as their "favorite book" of the year.

Born in Mount Vernon, New York, Mr. White attended public schools there. He was graduated from Cornell University in 1921, worked in New York for a year, then traveled about. After five or six years of trying many sorts of jobs, he joined the staff of The New Yorker magazine, then in its infancy. The connection proved a happy one and resulted in a steady output of satirical sketches, poems, essays, and editorials. His essays have also appeared in Harper's Magazine, and his books include One Man's Meat, The Second Tree from the Corner, Letters of E.B. White, The Essays of E.B. White and Poems and Sketches of E.B. White. In 1938 Mr. White moved to the country. On his farm in Maine he kept animals, and some of these creatures got into his stories and books. Mr. White said he found writing difficult and bad for one's disposition, but he kept at it. He began Stuart Little in the hope of amusing a six-year-old niece of his, but before he finished it, she had grown up.

For his total contribution to American letters, Mr. White was awarded the 1971 National Medal for Literature. In 1963, President John F. Kennedy named Mr. White as one of thirty-one Americans to receive the Presidential Medal for Freedom. Mr. White also received the National Institute of Arts and Letters' Gold Medal for Essays and Criticism, and in 1973 the members of the Institute elected him to the American Academy of Arts and Letters, a society of fifty members. He also received honorary degrees from seven colleges and universities. Mr. White died on October 1, 1985.

Photo by White Literary LLC [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 80% 13% 5% 1% 1% 80%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 80% 13% 5% 1% 1% 13%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 80% 13% 5% 1% 1% 5%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 80% 13% 5% 1% 1% 1%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 80% 13% 5% 1% 1% 1%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Customers say

Customers find the essays wonderful, brilliant, and detailed. They describe the book as a delicious, enjoyable read with a good sense of humor. Readers also appreciate the simple, beautiful, and to-the-point English usage.

AI-generated from the text of customer reviews

Customers find the writing style wonderful, brilliant, and detail-oriented. They appreciate the finely crafted descriptions of northeast middle America from a keen observer. Readers also mention the book is a superb example of essays as stories. They say it gives an interesting perspective on his life through the decades.

"...Besides the fact that it contains some of the best essays of all time, the book's foreword provides insight into the authors' views on the genre and..." Read more

"...essays is that they can be counted on to be insightful, amusing and well-written . White approaches an essay like a pleasant conversation...." Read more

" Every essay is wonderful ." Read more

"He's one of the best humorist I have ever read. Fascinating observations on humanity .Highly recommend." Read more

Customers find the book delicious, enjoyable, and beautiful. They appreciate the author's ability to entertain and inform readers on wide-ranging subjects. Readers also say the essays on world affairs are lucid and uncompromising. Overall, they describe the book as an outstanding work and engaging.

"...White impresses me most with his ability to entertain and inform readers on wide-ranging subjects...." Read more

"...They are entertaining without being too demanding , and are a great way to set day-to-day concerns aside. Treat yourself to a good read." Read more

"...For the design of this Harper edition, I absolutely love the cover and the tactile quality of it. (It also draws attention to his dachshund, Fred)...." Read more

"... Reading the essays was a pleasure and I just enjoyed dipping back into the book, the topics didn't really matter: packing up an apartment for a move..." Read more

Customers find the humor in the book insightful, amusing, and hysterical. They also say it's wonderful nostalgia and classics.

"...about White's essays is that they can be counted on to be insightful, amusing and well-written...." Read more

"He's one of the best humorist I have ever read. Fascinating observations on humanity.Highly recommend." Read more

"...Enjoy his writing style-detail oriented & good sense of humor ." Read more

"...E B White makes a trip in his car an exciting adventure. His essays are full of humor . Life was more rustic...." Read more

Customers find the book simple, beautiful, and to the point. They say the essays are the perfect introduction to his work. Readers also appreciate the matter-of-fact approach.

"...It's just that his approach is so matter-of- fact, easy going and accessible that you feel you've been invited to tea or are taking a leisurely..." Read more

"...never pretentious, always clear, simple and beautiful." Read more

"...White is a fantastic, skillful writer and his essays are the perfect introduction to his work...." Read more

" Simple , beautiful, to the point English usage with a dash of healthy humor." Read more

Customers find the pacing of the book sympathetic, kind, and humane.

"...The pig story is classic EB White.... so humane , so clear his writing...a man who can make you grieve for a dying spider and a dying pig is a man who..." Read more

"Beautiful little book . E.B.White has such a kind calming presence in his writings .i generally don't read non fiction but picked this up because it..." Read more

"EB White's essays are thought-provoking, wide-ranging, sympathetic and gorgeously written...." Read more

- Sort by reviews type Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

White published his first article for The New Yorker in 1925, then joined the staff in 1927, and continued to write for the magazine for nearly six decades. Best recognized for his essays and unsigned "Notes and Comment" pieces, he gradually became the magazine's most important contributor.

Essays of E. B. White. by E. B. White. Publication date 1977 Publisher Harper & Row Collection internetarchivebooks; americana; printdisabled Contributor Internet Archive Language English Item Size 576.0M . Access-restricted-item true Addeddate 2011-11-04 17:26:53 Boxid ...

E. B. White (1898 - 1985) began his career as a professional writer with the newly founded New Yorker magazine in the 1920s. Over the years he produced nineteen books, including collections of essays, the famous children's books Stuart Little and Charlotte's Web, and the long popular writing textbook The Elements of Style.

Once in a while something slips — one of the actors goes up in his lines and the whole performance stumbles and halts. My pig simply failed to show up for a meal. The alarm spread rapidly. The...

Meet essayist E.B. White—and consider the advice he has to offer on writing and the writing process. Andy, as he was known to friends and family, spent the last 50 years of his life in an old white farmhouse overlooking the sea in North Brooklin, Maine.

Thirty-one of E.B. White's essays grouped under such headings as "The Farm," "The Planet," "Memories," and "Books, Men, and Writing."

Selected by E.B. White himself, the essays in this volume span a lifetime of writing and a body of work without peer. "I have chosen the ones that have amused me in the rereading," he writes in the Foreword, "alone with a few that seemed to have the odor of durability clinging to them."

Selected by E.B. White himself, the essays in this volume span a lifetime of writing and a body of work without peer. "I have chosen the ones that have amused me in the rereading," he writes...

E.B. White (born July 11, 1899, Mount Vernon, New York, U.S.—died October 1, 1985, North Brooklin, Maine) was an American essayist, author, and literary stylist, whose eloquent, unaffected prose appealed to readers of all ages.

The warm reception of Letters of E. B. White in 1976 has led to the most welcome publication of a collection of thirty-one of White’s essays, most of which appeared originally in The New...